ABSTRACT

The crowdsourced OpenStreetMap mapping platform is utilized by countless stakeholders worldwide for various purposes and applications. Individuals, researchers, governments, commercial, and humanitarian organizations, in addition to the engineers, professionals, and technical developers, use OpenStreetMap both as data contributors and consumers. The storage, usage, and integration of volunteered geographical data in software applications often create complex ethical dilemmas and values regarding the relationships between different categories of stakeholders. It is therefore common for moral preferences of stakeholders to be neglected. This paper investigates the integration of ethical values in OpenStreetMap using the value sensitive design methodology that examines technical, empirical, and conceptual aspects at each design stage. We use the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team, an existing volunteered geographic information initiative, as a case study. Our investigation shows that although OpenStreetMap does integrate ethical values in its organizational structure, a deeper understanding of its direct and indirect stakeholders’ perspectives is still required. This study is expected to assist organizations that contribute to or use OpenStreetMap in recognizing and preserving existing and important ethical values. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to evaluate ethical values methodically and comprehensively in the design process of the OpenStreetMap platform.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, mapping processes were performed by experienced professionals using standard land surveying and mapping methods, while national mapping agencies played a pivotal in providing authoritative mapping infrastructures. In most cases, achieving even moderately accurate measurements required the use of expensive professional equipment (Haklay, and Weber Citation2008). Nowadays, however, due to budget and time constraints, and lack of manpower, the authorities are not always able to provide adequate data to produce comprehensive and timely mapping infrastructures (Olteanu‐raimond et al. Citation2017).

Around the year 2000, the Geographic World Wide Web (GeoWeb) for mapping applications matured, enabling the sharing of geospatial information over the Internet between data contributors and consumers. As a result, innovative location-based applications were significantly enhanced (Haklay, Singleton, and Parker Citation2008), as were mapping infrastructures that were based on data contributed by volunteers. The renowned OpenStreetMap (OSM) is probably the most prominent example that promotes Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) campaigns, having today more than five million active registered contributors.

Despite the many merits of OSM, the storage, usage, and integration of this data in software applications often create a complex ethical dilemma regarding the relationship between the contributors and the consumers, from both legal and ethical point-of-view. As the number and scope of OSM projects and participants continue to rise, examining these issues becomes imperative. Ethical values may be negatively impacted by innovative technological developments, such as OSM-based technological work paradigms, due to a conflict of interest between the ethical values of the various stakeholders involved. One type of conflict exists between the value of the security of contributor’s personal information and privacy of the individual and the value of the usability and availability of the data provided by that person. Nowadays, it is possible to identify and expose private information about the volunteers based on the spatial data and information they provide, e.g. a person’s financial status, lifestyle, and health (Doytsher, Galon, and Kanza Citation2012). In Ahmouda, Hochmair and Cvetojevic (Citation2018), patterns of OSM contributors and Twitter users were used to explore whether a contributor is local or non-local. The authors state that such information might not be available in the future resulting from new data protection regulations, like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which affects OSM user policies. Another example (Ajayakumar and Ghazinour Citation2017) reverse geocoding of tweets was performed using OSM web services and other software applications, resulting in spatial privacy vulnerabilities that enabled revealing the location address of the individuals who tweeted. These are ethical dilemma examples reflecting a conflict between protecting contributors’ personal data and their wellbeing, and it also illustrates the importance of methodologically investigating ethical conflicts in OSM platforms and balancing the moral principles of different stakeholders.

Another dilemma is if national mapping agencies can exclusively extract contributed data from platforms, such as OSM, for use in authoritative mapping infrastructures and services. According to Fogliaroni, D’Antonio and Clementini (Citation2018), the challenge now is to enable validating VGI quality by comparing it with authoritative data in response to the increasing interest of national organizations to use VGI. The fact that this data was originally contributed to serving the public for free, and is now being used by national agencies that rely on government funding promotes ethical issues.

Another dilemma, or possible conflict, can be prompted by data quality expectations between the contributors and the users who expect a certain service level. For example, since OSM is based on the premise of data contribution from non-cartographers, Borkowska and Pokonieczny (Citation2022) stated that it is basically impossible to apply the principles of geographic data evaluation as defined in ISO 19157:2013 (Geographic information – data quality), which establishes the principles for describing the quality of geographic data. Further ethical concerns within OSM were raised in Schröder-Bergen et al. (Citation2021), mentioning the reproduction of “patterns of exclusion” and “colonizing processes” in the Global South, as well as neglecting local knowledge, local representatives, and ground truth. The said dilemmas and concerns, together with other challenges, make it necessary to evaluate how ethical values are incorporated in the design of VGI platforms, while suggesting methods to solve existing and potential conflicts.

This article focuses on the ethical dilemmas related to the use of OSM data in various technological and social innovations by using the Humanitarian OSM Team (HOT) as a case study. In some segments, this work presents the framework for integrating ethical values in similar projects. HOT is a “US-based NGO and global community of thousands of volunteers working together to use maps and open data for humanitarian response and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)” (Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team https://www.hotosm.org/jobs/data-lead/), such as disaster risk reduction, poverty elimination, and sanitation access. HOT performs its work through OSM, reinforces the global use of OSM, and supports creating local OSM communities (https://www.hotosm.org/what-we-do). To carry out the investigation, the Value Sensitive Design (VSD) methodology is introduced – a technique for integrating ethical issues and values into the design process that examines technical, empirical, and conceptual aspects at each design stage. This framework was first applied in the fields of information systems (Friedman et al. Citation2013) and human-computer interaction (Borning and Muller Citation2012). Integrating VSD for ethical purposes offers several significant contributions, including the integration of privacy by design, for example, as suggested by Cavoukian (Citation2010). This study discusses the importance of identifying all relevant direct and indirect stakeholders, as a basis to analyze their ethical principles and possible conflicts of interest between their values, potential benefits, and possible harms they might incur – as a result of engaging in a specific OSM-based project or technology. By doing so as early as the planning stage, full integration of ethical values can be ensured, or at least enhanced, enabling compliance with these important values and principles rather than having to make compromises. This study is expected to assist organizations that contribute to or use OSM, such as national mapping agencies that consider promoting the use of contributed geographic information, in recognizing and preserving existing and important ethical values.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. OpenStreetmap

OSM is considered as an exemplary and proxy of a VGI project (Antoniou and Skopeliti Citation2017), collaboratively created and supported by mappers who volunteer and maintain mapping data. OSM contribution patterns vary by time, country, and type of contributor. For example, Ahmouda, Hochmair, and Cvetojevic (Citation2018) showed that higher proportion of volunteers signed up for OSM during the earthquakes that took place in central Italy in 2015 and Nepal in 2016. The authors also concluded that contributors in Italy were more experienced than contributors in Nepal. Differences in these areas have ethical implications. Despite the popularity of OSM, its reliability and accuracy are still questioned and widely studied (Basiri et al. Citation2016; Hashemi et al. Citation2015; Salk et al. Citation2016), which led to the emergence of various methodologies and software for assessing data quality of OSM (Amirian et al. Citation2015; Arsanjani et al. Citation2015; Fan et al. Citation2014) and assessing the correlation of the above by characterizing participants’ behaviors (Bégin and Roche Citation2017). Still, some aspects of OSM are often less discussed in current research. As the popularity of OSM increases, studies are still missing on the integration of ethical values of the various stakeholder groups involved in OSM.

2.2. Privacy and interests of geographic information volunteers

The literature on ethical issues within the VGI context is limited. Mooney et al. (Citation2017) explain how issues regarding the involvement of stakeholders in VGI-related projects can be categorized into three main groups: privacy, ethical, and legal aspects. For example, researchers wishing to employ VGI data should consider the ethical aspects by ensuring that the volunteers are aware of relevant risks and benefits following their participation in the data collection. Cho (Citation2014) also addresses concerns following the employment of user-generated geospatial data, including the issue of: “ownership: intellectual property and moral rights” (4). The author suggests ways to remove any data that may infringe on copyrights, by statements such as: “to prevent further infringement” and to use “disclaimers to alert users to the limitations of the data … and prevent litigation”.

Privacy in general, and information privacy in particular, should be addressed in VGI-based systems. Smith et al. (Citation2011) review several books and articles on information privacy and conclude that while information privacy has been widely studied, the findings and theories are not comprehensive to make a significant contribution to the field. Moreover, with regard to values, the authors differentiate between privacy as an economic commodity and privacy as a right, and add that despite their similarities, privacy and ethics are not the same.

To ensure the security of the contributors, their private and personal information must be protected from attacks, hackers, wireless threats, or unauthorized access. However, once volunteers provide geospatial and other types of information via their mobile phones, all other data stored on their phones may be at risk of exposure (Elwood, and Leszczynski Citation2011). The literature suggests several approaches to preserving the volunteers’ personal information security. Miles (Citation2017), for example, suggests establishing a private blockchain for keeping transaction data secure and recommends integrating encryption technologies (i.e. converting information into a code) within a security infrastructure. Since 25th May 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been enforced in the European Union for protecting data subject rights (i.e. protecting the people who collected and contributed the data that is being used by an organization), based on the following European Commission right: “Everyone has the right to the protection of his personal data” (Regulation, 2016/679 Citation2016). In line with these acts and regulations, the security of the volunteers’ personal information must be regulated and guaranteed in VGI projects.

Location privacy (or geoprivacy) in applications and User Interfaces (UI) are discussed in literature. In an experiment conducted by Ataei, Degbelo, and Kray (Citation2018), a UI was created to enable users to control their location privacy preferences, to be able to decide when, where, and with whom to share their location. Their experiment was based on principles that stemmed from a range of models: privacy of individual users (Westin Citation2003), privacy by design (Cavoukian Citation2010), and principles of interactive technology (Shneiderman and Plaisant Citation2010). The results of the experiment, in which twenty-three educated participants took part through online channels, showed that the specific UI for managing location privacy provided users with an increased sense of control. Intending to check the degree of user engagement in an application as a function of information transparency and personalization, Chen and Sundar (Citation2018) conducted a pilot study with more than 300 participants using the GreenByMe eco-friendly mobile application. Their findings showed that overt personalization, enabling users to control their location privacy settings and increased transparency, increases users’ confidence, decreases users’ privacy concerns, and increases their engagement and acceptance of the technology.

2.3. Ethics, ethical codes and practices

Schmidt (Citation2013) presents challenges in four categories of crowdsourcing and states that a code of ethics must be developed for protecting the rights of stakeholders belonging to each category. In his criticism of the lack of enforcing important ethical values, Schmidt writes in p.4: “ … all is not well in the world of crowdsourcing at the moment, especially concerning fairness, respect and economical sustainability for the contributors”. The author concludes by stating that while crowdsourcing will always entail some degree of exploitation, all stakeholders combined must develop criteria that define what is considered fair implementation of crowd work that ensures standardized fair labor. These statements are in line with the VSD concept (Zhang and Galletta Citation2006) that addresses the importance of identifying all direct and indirect stakeholders involved, as well as the potential benefits and harm that may be incurred by each one of them.

Zhang and Galletta (Citation2006) provide practical guidelines for enabling researchers and designers to incorporate ethical and moral values while taking into consideration the complexity and delicacy of social relations. To create this framework, the researchers conducted three case studies: “information and control of web browser cookies, … high-definition plasma displays in an office environment to provide a window to the outside world, … integrated land use, transportation, and environmental simulation system to support public” (p.2). According to the results, the authors set practical implications for integrating VSD, which are outlined in the next chapter.

Bynum (Citation2017) presents a more philosophical approach to the topic, claiming that ethics of information will necessarily have to continue to change and evolve, because of the continuous technological developments that lead to numerous new policy vacuums (which also include ethical challenges). This supports the statement by Friedman and Kahn: “ … how such values play out in a particular culture at a particular point in time can vary, sometimes considerably”. (Friedman and Kahn Citation2007).

An additional ethical challenge relates to the reliability of the data. Incorrect or biased information can be difficult to identify and could cause serious harm and it is hard to relay these risks to stakeholders. This ethical issue could lead to real danger, in the case of a large-scale disaster, for example, if rescue teams are only able to reach a small number of people – because of incorrect mapping data. The consequences of providing incorrect data according to Mooney et al. (Citation2017) include: misleading citizens and authorities and delaying VGI-based projects, harming the lives of others, and lack of trust in the quality and usability of VGI systems.

Since VGI is often associated with geographic-oriented crowdsourcing and wisdom-of-the-crowd initiatives, Dror, Dalyot, and Doytsher (Citation2015) discuss and characterize the differences between the two. The authors classify several acknowledged and socially-driven mapping and location-based services according to eight indices, which are closely linked to ethics, namely: diversity, decentralization, independence, aggregation, knowledge, activity, privacy, and exploitation. The authors conclude that the privacy of volunteers must be guaranteed; data should be contributed willingly and independently without being influenced by other people’s opinions; and, contributed data must be in a field with which the contributor is familiar and knowledgeable.

Meng (Citation2020) provides an analytical review of the mutually changing roles and responsibilities of humans and technologies according to four main aspects: informing, enabling, engaging, and empowering. The review prompts several challenges when human-technology collaboration is at hand, stating that, among others, the ethical concerns for the handling of large geographic data volumes, some of which are contributed, cover not only the sensitive issues related to, e.g. privacy violation, but also to questions of keeping the technological character within its constructive sphere of societal influence.

Standing and Standing (Citation2018) propose specific guidelines for incorporating important ethical values in crowdsourcing projects – ensuring that the volunteers are not being exploited – based on case studies and the existing literature, and in terms of relational, economic, and knowledge-related outcomes. For example, while companies may choose to implement crowdsourcing as a means of decreasing expenses, they should pay the volunteers a certain fee, or at least inform them of their Intellectual Property (IP) rights.

It is important to understand what the term value refers to. The Business Dictionary (Citation2019) defines values as “important and lasting beliefs or ideals shared by the members of a culture about what is good or bad and desirable or undesirable. Values have a major influence on a person’s behavior and attitude and serve as broad guidelines in all situations. Some common business values are fairness, innovation and community involvement”. As values vary between different individuals, corporations, and cultures, we suggest classifying them into two groups: personal values and corporate values. Moreover, it is important to emphasize key values that must not be compromised, such as security, health, quality, and company principles that reflect the organization’s philosophy. Such values differ among various stakeholders. The advantage of the VSD methodology is that it takes into account these key values and the various stakeholders.

While the literature does offer several guidelines for introducing ethical values into the design stage, these are missing for VGI-related projects. Accordingly, our research focuses on the renowned OSM, which although maintained by the public, serves numerous technologies and services.

3. Methodology

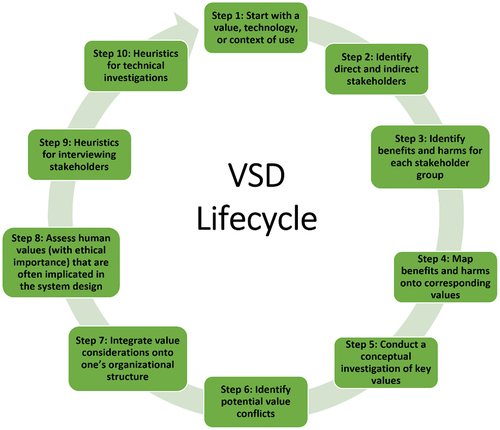

In most cases, ethical values are analyzed in a conceptual and theoretical manner, rather than being translated and modeled into an unambiguous process that can ensure their actual implementation. VSD methodology bridges existing modeling gaps as it analyzes conceptual, empirical, and technological aspects of design, investigate stakeholders’ values methodically and identifies value tensions. Our study utilizes the VSD methodology to enable the integration of ethical aspects during the planning stages of a VGI-project. Zhang and Galletta (Citation2006) present ten practical steps (stages) of the VSD methodology () adopted in this study. The conceptual analysis of VSD focuses on determining and investigating values based on literature and stakeholders’ preferences. The empirical analysis turns the evaluated values at the conceptual stage into design requirements. Technical investigations evaluate whether the development restrictions maintain or neglect the values and the design requirements. We investigate projects that rely on OSM (data) according to the OSM codes of conduct while mapping conflicts between the values of different stakeholders.

3.1. Stage 1: defining the investigated technologies

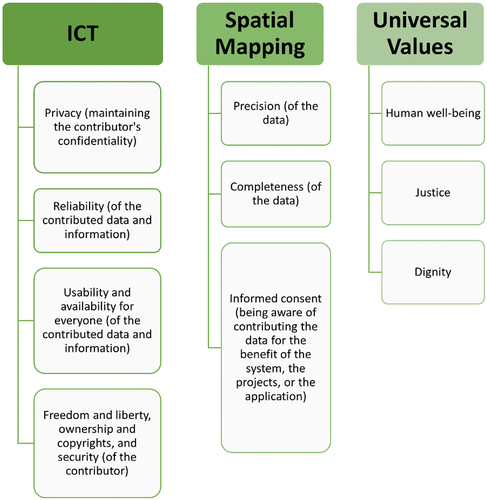

The conceptual investigation of VSD defines the relevant values based on both literature and stakeholders’ preferences. To identify the most important ethical values for OSM-based systems, we examined the values presented in Huldtgren (Citation2015) in the field of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), since both ICT and OSM allow people to update digital data and become involved through the Internet and mobile devices. Moreover, both ICT and OSM enable the storage, access, and transmission of data, and involve personal, organizational, and socio-ethical aspects, risks, and benefits. Based on this, we chose to include, among others, the values depicted on the left of . With regards to spatial mapping, especially through OSM, it is also important to add the ethical values depicted in the middle of . In response to the criticism of VSD, Friedman and Hendry (Citation2019) state that VSD has to be constrained to at least the three universal values, depicted on the right of . A list that includes all the ethical values of OSM and justifications for pointing them out is missing. In this regard, OSM’s main values were inferred from OSM’s moral clauses and were compared to the values we chose in Stages 3 + 4. The technical investigation was made in Stages 7 + 8, where the effect and the limitations on the identified values were examined using the case study. Empirical investigation (at Stages 9 and 10) assesses stakeholders’ values and turns them into practical requirements through designing a technology.

3.2. Stage 2: identifying the direct and indirect stakeholders

A stakeholder is any party with an interest, in this case VGI. Numerous stakeholders are involved in OSM-based projects, which are complicated and lengthy processes that entail collecting, evaluating, and processing the data, achieving relevant information, creating user interfaces, providing users with the information, maintaining and updating the system, and more. A list of OSM-based services is published on the OSM wiki website (see Appendix B for relevant OSM links). This list presents applications that rely on OSM data and information, describes their functionalities, and categorizes them according to different fields like history, archeology, indoor navigation and mapping, routing, accessibility for persons with disabilities, public transport, and many others.

Building on the definitions of Mooney and Minghini et al. (Citation2017), we mapped the various stakeholders and divided them into three groups, presented in , together with their affinity to the different relevant values. “V” depicts where a stakeholder expects to receive a value, while ‘X’ indicates that a stakeholder is required to comply with a value. A blank cell indicates that there exists no affinity. The three stakeholder groups are:

Contributors of data and information: this group is directly involved and shows interest in VGI, and is composed of citizens, commercial mapping companies, regional mapping authorities, and competitors.

Users/customers: citizens, commercial mapping companies, regional mapping authorities, and competitors.

All others, including indirect stakeholders: people who neither contribute nor use the information, such as employer/owners’ management, employees, development colleagues and partners, the media, scientists, and researchers.

Table 1. The three stakeholder groups and their affinity to the different relevant values.

While all parties involved in OSM-based projects must act ethically, we focused here on seven main stakeholders: contributors; customers/users; the public; local mapping agencies and land surveyors; academic researchers (who use the contributed information for research purposes and for improving geographical information systems); engineers and other professionals (who establish and maintain OSM-based systems); and businesses (that provide OSM services). Although some stakeholder groups’ interests could potentially conflict with those of other stakeholders, e.g. contributors and users, this categorization of stakeholders provided by OSM facilitates evaluating the integrated ethical aspects using the VSD framework. OSM allocates different codes of conduct to different groups of stakeholders, which align with VSD.

Outline: analyzing Stage 2, we did not find indications that OSM stakeholders were involved in formulating ethical guidelines. We therefore recommend that stakeholders’ perspectives should be revealed and considered before updating ethical guidance or creating new ones. Representatives of different stakeholder groups should participate in establishing the various codes of ethics related to OSM either by answering questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, sketching activities, election methods, or other methods suggested in Friedman, Hendry, and Borning (Citation2017).

3.3. Stages 3 + 4: identifying the benefits and potential harm to stakeholders and values

These two stages are explained by presenting ethical issues that are specific to integrating OSM into software programs, applications, or organizations, such as HOT. Since OSM has several codes of conduct, including drafts and suggested codes that underline various aspects, we highlight only relevant OSM clauses that relate to the investigated values (see ). For detailed analysis see , where the clauses are examined against the interests and expectations of the three groups of stakeholders.

3.3.1. Mutual relationships between contributors

Community Code of Conduct (Draft) contains the code of conduct for OSM Mailing lists and Code of conduct/State of the Map (short) focus on the expected behavior between data contributors and members of OSM, such as mutual respect, collaboration, transparency, sharing knowledge, dealing with disagreements, avoiding violation and harassment, etc. (see clauses (1), (2) and (3) in ).

3.3.2. Data integrity

“Good Practice” (https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Good_practice) guidelines focus on data quality but it is not obligatory: “Nobody is forced to obey them. There might be cases where these guidelines don’t apply or even contradict each other”. “Good Practice” asks the contributors to avoid mapping unverifiable features, such as historic events, historic features without ruins, temporary events, and temporary features. “Good Practice” relates also to data precision and reliability. Clauses (4), (5), and (6) in are relevant examples. In the wiki page of data OSM contributors, global and national publishers who give consent to including their data in OSM are listed. However, they explicitly do not provide guarantees regarding the provided data. For illustration, see clause (7) in .

3.3.3. Stakeholders’ interest, involvement, and consciousness

The reviewed codes of ethics cover a range of stakeholders; however, questions should be asked regarding the involvement of stakeholders in the process of writing this ethical guidance, whether their interests were sufficiently emphasized and whether they were inquired for determining their preferable values. Still, OSM informs contributors on the importance of their role and the interests society achieves as a result of their contribution (see clauses (8) and (9) in ). As stated in OSM FAQ, for example, data bought from commercial maps may not be up-to-date, while OSM is believed to be continuously updated by volunteers (see clause (10) in ).

Outline: analyzing Stages 3 + 4, we conclude that OSM clauses relate to a wide variety of stakeholders’ values, interests, and responsibilities. However, there is no indication that stakeholders took part in setting these clauses. As depicted in , the values that we highlighted in the previous stages partially comply with the existing literature and OSM clauses, and conflicts between these clauses and the assessed values of stakeholders were identified in .

3.4. Stage 5: conceptual examination of key values in line with stage 1

3.4.1. Defining who can contribute data

It is important to look after the common good, i.e. members of the public who use the OSM-based service. As data is contributed by different people and from different communities, one must ensure that those contributing data are indeed knowledgeable enough to make this contribution. Otherwise, the contributed data could harm the public and the data consumers. If OSM projects lack mechanisms for ensuring the reliability of the data contributed, the public’s right to correct and proper data will likely be denied. In this aspect, OSM emphasizes the importance of data quality, verifiability, and error correction through its code of conduct “Good Practice”, which also specifies editing standards. However, “Good Practice” guidelines are not obligatory, as mentioned earlier in the analysis of Stages 3 + 4.

3.4.2. Professionalism and impartial for the benefit of the common good

Organizations that deal in VGI must be skilled and impartial toward any sources of funding. There could exist a conflict between a person’s well-being and trust, the availability and the usability of the data. Otherwise, contributors could provide, e.g. partial information about all gas stations in the area by mentioning a specific chain of gas stations for personal financial benefit rather than for the benefit of the public. In this aspect, HOT guidelines require HOT members to “not accept or seek financial or other gains beyond the representative value resulting from affiliation with HOT, except in compliance with HOT guiding and policy documents”. Besides, it requires members to “not use the name, trademarks, products developed and/or services provided by HOT for personal individual benefit”.

3.4.3. Informed consent, passiveness, preserving the privacy and information security of others

Informed consent of data volunteers is the foundation of ethical research, ensuring that volunteers are aware and informed about the risks relating to their contributed information. This prohibits the use of other people’s temporal or spatial information without receiving their consent. In this context, OSM prevents its users from using copyrighted data or “any other proprietary data” (https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Copyright). In the OpenStreetMap Contributor Terms 1.2.4, (https://wiki.osmfoundation.org/wiki/Licence/Contributor_Terms) contributors agree on respecting “the intellectual property rights of others”. Being aware of providing information and preserving a person’s privacy and information security is not always guaranteed in location-based applications, which usually require users to sign an agreement for providing location data, yet most users are not aware of just how much information can be achieved based solely on a person’s location.

OSM explains the reasons why it stores and processes personal data in its Privacy Policy. On one hand, OSM stores different sorts of data, such as editing sessions meta-data, user ID, e-mail address, and IP address, which are mostly accessible only to operational personnel of OSM. Besides, OSM automatically collects information about the visitors of “OSMFoundation” (www.osmfoundation.org) website based on their APIs, including: (a) IP address, (b) browser and device type, (c) operating system, (d) referring web page, (e) the date and time of page visits, and (f) the pages accessed on our websites. On the other hand, in its privacy policy (https://wiki.osmfoundation.org/wiki/Privacy_Policy), OSM offers a “not required by law” mechanism for restraining privacy-related issues, and it also provides its users the “right to object against the processing based on legitimate interests of the data controller”. Besides, there exists optional information that users may decide not to provide, such as home address.

3.4.4. Intimacy

The term intimacy refers to the closeness between individuals or groups of people and enables volunteers to work with one another in an easy-going, trustful, and close environment. Intimacy also allows contributors to detect the level of information required based on the different audiences that may wish to access this information. However, intimacy could be threatened by OSM-based applications, if contributed data is used by undesirable users. OSM manages the interaction and etiquette between its users through its “Community Code of Conduct (Draft)”, its wiki page “Etiquette” and its “Suggested code of conduct for OpenStreetMap Mailing lists”.

3.4.5. Anonymity

Contributors’ anonymity is key to OSM-based projects, especially once a contributor’s identification is revealed, while this cannot be reversed and undone (Sula Citation2016). Therefore, anonymization is required to restrict the mining of the contributed data – a process that is essential for building comprehensive information systems and other needs. To solve this gap, Li, Palanisamy, and Krishnamurthy (Citation2018) suggest a range of techniques for multi-level privacy-preserving that only enables access to data that is specifically needed, while simultaneously preventing the use of that data for additional purposes. OSM does not allow anonymous edits and contributions, but it does allow contributors to log in with non-identifying names and to change them whenever they want. OSM anonymizes survey data before making it public and enables third parties to utilize this data for specific reasons, such as research. However, these anonymized data “may be useful to the Foundation in the future for comparison purposes, may be retained indefinitely under applicable data privacy laws”.

Outline: analyzing Stage 5, we conclude that OSM handles the analyzed values; however, gaps related to, e.g. anonymity and intimacy, still exist, hence practical solutions for bridging these should be handled by OSM (some solutions are suggested in the literature review).

3.5. Stage 6: identifying potential conflicts among the values

Conflicts are identified in considering the analysis in the previous stages, such as in . Conflicts can also be related to the technology and digital divide of the world. For example, collecting data from users creates a technological gap between different places in the world. People in developed regions have greater access to technology and can continually contribute data, thereby improving related services, while people in developing regions have less access to technology, rendering them less able to contribute data and improve the technological systems from which they benefit. Although the developed regions are at an advantage, the contributed data could have a negative environmental impact, as natural resources become visible and exploited, thus making the developing regions at an advantage in this context. Another conflict is reflected by national mapping agencies contributing to OSM: for one, their contributions boost human well-being, however, they are interested in maintaining government funds for their work. A few other conflicts among privacy and the values of anonymity and responsibility are extended and explained.

3.5.1. Privacy

Preserving privacy is a key value for ensuring a continuous flow of volunteer contributors over time. If people worry that their privacy is in jeopardy, they will avoid contributing data. Yet, if people have a strong feeling of privacy, they will probably also develop a feeling of trust in the system and cooperate more willingly and efficiently. However, at certain stages, privacy concerns might be in conflict with other values, such as informed consent when providing geo-spatial data. Moreover, even if privacy and anonymity are ensured at present, they could be integrated into other databases in the future, leading to certain personal details being revealed (e.g. Shen et al. Citation2016). As with other VGI-based systems, OSM stores and processes personal data, while edits made by a specific user are visible to all, including user ID, editing timestamps, links for cross-reference, etc. Editing programs, such as JOSM, make additional data available, like the user’s language settings. Therefore, creative approaches must be designed and developed to ensure contributors’ privacy, without harming the rights of the interested parties, and to prevent clever manipulations and deceptions that may convey a false feeling of privacy.

3.5.2. Anonymity

Anonymity provides a feeling of security and confidence of not being traced. Although OSM enables contributors to choose non-identifying login names, it does not accept anonymous contributors. OSM holds non-geographic information about volunteers, for the reasons of improving its service, contacting them for further questions, banning violations, enabling collaboration between contributors, and evaluating the integrity of data. Although to some extent anonymity is disrupted, evidence shows that the trust in OSM increases as is evident by the growing number of contributors and users.

3.5.3. Responsibility

Individual data volunteers or NMA contributors usually do not grant warranties on data completeness, accuracy, and timeliness, and they are not responsible for decisions that users make based on the contributed data (see ). This is important for the sustainability of contributors, since if they hold such accountability, they may hesitate to contribute data. All the same, this fact results in a less trustworthy feeling upon users who expect to receive reliable data. The OSM codes of conduct balance this issue by emphasizing the importance of reliability and data correctness.

Outline: analyzing Stage 6, we conclude that conflicts exist between moral values and principles in OSM. Therefore, we suggest that, as proposed in VSD, OSM iteratively map and identifies them during its continuous development in an attempt to minimize them.

3.6. Stages 7 + 8: integrating and assessing moral considerations into the company’s organizational structure

The moral considerations of organizations that use OSM data are reviewed about HOT. The HOT’s Membership Code of Conduct requires “HOT Associates”, including “members, volunteers, contractors, and other contributors”, to oblige (1) HOT, (2) colleagues, partners, donors, and beneficiaries, and (3) Society. We review the HOT membership code of conduct to identify the values it considers and lacks. in appendix A shows the values that HOT members should commit to; these values are derived from the clauses in the HOT code of conducts, which mainly focuses on “openness, collaboration and participation” (https://www.hotosm.org/code-of-conduct). In , clause numbers are given, where each number is accompanied by the values derived from the specific clause.

Besides, HOT published its privacy policy, which considers users’ preferences and rights. In addition, in “Community Types and Roles”, HOT lists the different community roles it has and the ways they are expected to contribute. For example, the connectors’/teachers’ tasks focus on sharing their knowledge with less experienced contributors, outreaching, and training them. The mappers’ role centers on detecting required mapping activities, recruiting, and connecting potential contributors. Mission supporters are responsible for developing policy membership and codes of conduct, i.e. sustaining ethics. These, and other roles, enrich OSM and expand its outreach, which contributes to humanity and people’s well-being. This shows that the HOT organization integrates moral consideration into its structure. OSM also integrates such considerations through its various codes of conduct and guidelines.

Outline: analyzing Stages 7 + 8, in general, HOT’s policies correspond with OSM policies, as they both have the common purpose of enabling free mapping for human wellbeing, each of them defines the relationship between its members and considers privacy aspects. However, after reviewing HOT’s official webpage, we miss published guides on data completeness, accuracy, timeliness, etc. HOT service may conflict with commercial mapping agencies, whose primary principle is income. We suggest official organizations, which are involved with OSM and directly affect its work, adopt OSM ethical considerations in their organizational structure.

3.7. Stage 9: interviewing stakeholders

In line with the stages of VSD (Friedman, Hendry, and Borning Citation2017), when interviewing stakeholders, the interviewer should prepare basic questions in advance. During the interview, more in-depth questions of why can be asked to provide additional data and information. Why questions require the interviewees to keep talking, revealing further input about their beliefs and attitudes regarding the ethical value in question. The researchers also recommend asking indirect questions, about their lifestyles or behavior in specific situations, for example, to reveal additional attitudes and rights. Interviewees can also be asked to solve a certain task with the same purpose.

In this context, we disseminated a questionnaire to reveal the value preferences of contributors and customers of volunteered data. The focus group included 25 land surveyors and land surveying students. They were asked several questions on various aspects related to their role as data contributors and consumers (in line with the category they belong to in in the Appendix). We explicitly asked them to rank their preferred values when dealing with a system that relies on volunteered data and asked indirect questions that aim to expose their values by determining their behavior in dilemmas related to these systems. Responses to the closed questions reflected their appreciation of public good value, data quality, reliability, and trustworthiness. However, their trust in volunteered data for statutory use decreases, and their doubts about using the system both as data contributors and consumers if their privacy is not guaranteed. The questionnaire also included an open question related to their willingness to contribute, which in most cases the answer contradicted their approach as stated in the previous closed questions. This implies that their answers might not reflect their real intentions.

Outline: analyzing Stage 9, the values that land surveyors emphasized are compatible with several suggested values in stage 1, such as privacy, reliability, and people’s wellbeing. We recommend that OSM conducts semi-structured interviews and questionnaires for a deeper understanding of its direct and indirect stakeholders’ perspectives to update its ethical guidelines accordingly.

3.8. Stage 10: discussion and heuristics for technical investigations

In line with the previous stages, it is obvious that the frequent technological developments must be specifically addressed from an ethical point of view during the project’s lifecycle, to incorporate the continuation of the technological development and the social contribution. All stakeholders must behave ethically, from the initial stages of setting up the system and throughout the entire process. Integrating ethics in the design is among the primary purposes of VSD. highlights the current state of ethical aspects in the different stages of the lifecycle of OSM projects along with our recommendations for each stage.

Table 2. Ethical aspects in the context of OSM: current state and recommendations.

4. Discussion and conclusion

We investigated and analyzed the implementation of VSD in the design of OSM-based projects. We mainly focused on the stakeholders involved in the process of creating and using OSM data and their rights, where future research will apply additional iterations of VSD methodology in OSM projects. We conclude that ethical aspects of OSM partially comply with VSD; the values highlighted in OSM’s codes-of-ethics meet some of the requirements that appear in literature, while some were suggested by us in stage 1. Other gaps between the existing OSM’s ethical aspects and the VSD investigation were identified. Actions should be taken to bridge these gaps, such as the need to reveal the stakeholders’ value preferences and integrate them into the different codes of ethics. Conflicts between moral values and principles exist in OSM; iterative mapping and identifying of the values may be pursued to overcome existing conflicts. Some solutions for ensuring specific values, revealing the stakeholders’ perspectives, and involving them in creating ethical guidance are suggested. Finally, we recommend that official organizations engaged with OSM adopt OSM ethical considerations in their organizational structure to overcome existing gaps in ethical values.

Investigation of key values in the fifth stage of VSD is focused on the importance of privacy and its priority among other values that it may conflict with. Hence, it is necessary to conduct future research for proposing and implementing new methodologies for guaranteeing rigorous privacy, especially because previous studies proved the possibility of circumventing existing privacy preservation practices. Reliability of OSM data could be improved and assured by various methods, where OSM projects have the potential to compete with authoritative geospatial data infrastructures or with commercial ones, such that it may enter other scientific fields, further enabling data distribution and diversity. Despite the many merits and significant contributions related to OSM, we conclude that properly handling ethical values should be integrated into the lifecycle of OSM, where we suggested key guidelines to achieve this.

VSD in OSM demonstrates considerable value since it can deal with the diversity of resources and stakeholders involved, which allows understanding of the different attitudes, needs, and expectations. We expect that customary sessions with stakeholders’ representatives, where they can express their positions and share their standpoints, could effectively enhance the outcome of integrating VSD. VSD is beyond theory and concepts. It has applicable aspects, such as integrating values in organizations; however, we believe that VSD cannot deeply analyze technological developments. Besides, VSD does not cover all the relevant issues relevant to OSM, and additional aspects need to be analyzed. For example, country disparities and the aim of a specific project may change the priorities of rights and ethical principles. Evaluating interviewers (data contributors, project coordinates, and interested parties) needs to be embedded in VSD; before identifying them, it is essential to verify whether they are expected to make it difficult to protect the ethical values and rights of different participants, or not.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to methodically integrate VSD in OSM-based projects. The VSD methodology could be later applied by other developers who work in the VGI field for future design and development, where the stakeholders should be interviewed before the final stages of planned updates for fitting the upcoming progress to their needs and values. The VSD perspective is defined to be iterative, meaning that modifications in OSM-based technology design are expected after applying the stages of VSD and after identifying the conflicting values, while the VSD process should be implemented again to assuring that fewer conflicts after the modifications were implemented. The contribution of this research is in proving the indispensability of integrating ethical values in OSM, where we believe it will further contribute to the many qualities of OSM and its global social footprint.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data was created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ruba Jaljolie

Ruba Jaljolie is a PhD candidate at the Department of Mapping and Geoinformation Engineering, The Technion. Her research is on multi-dimensional land management systems (MLMS), where she develops algorithms, models, and processes for expanding existing 2D land management systems into MLMS. She also focuses on the perspective of diverse stakeholders and experts who use MLMS, investigating the ethical dilemmas related to data collection and the integration of volunteered geographic information in MLMS.

Talia Dror

Talia Dror is a PhD candidate at the Department of Mapping and Geoinformation Engineering, The Technion. Her research is on social location-based services, where she investigates the use of historical data for augmenting user-generated maps. She develops algorithms and spatial models for improving the accuracy of OpenStreetMap data.

David N. Siriba

David N. Siriba is a Full Member of the Institution of Surveyors of Kenya and is a licensed Land Surveyor. Currently, he is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Geospatial and Space Technology at the University of Nairobi responsible for coordinating the Master of GIS degree programme. He is involved in research on the following themes among others: various aspects of volunteered geographic information systems; use of social media for traffic incident reporting; geodetic infrastructure modernization; spatial data infrastructures, land administration domain modeling; use of satellite imagery for various applications, including air quality, agriculture, and climate change modeling.

Sagi Dalyot

Sagi Dalyot is an Assist. Prof. at the Department of Mapping and Geoinformation Engineering, The Technion. He is a geodata scientist developing methods of interpretation, mining, and integration of crowdsourced user-generated content to augment and develop location-based services and smart mapping infrastructures, focusing on routing and navigation solutions for people with mobility disabilities. He is the chair elect of the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) Commission III on Spatial Information Management, and he serves as secretary of ISPRS WG IV/5 on Indoor/Outdoor Seamless Modelling, LBS, and Mobility.

References

- Ahmouda, A., H. H. Hochmair, and S. Cvetojevic. 2018. “Analyzing the Effect of Earthquakes on OpenStreetMap Contribution Patterns and Tweeting Activities.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 21 (3): 195–212. doi:10.1080/10095020.2018.1498666.

- Ajayakumar, J., and K. Ghazinour. 2017. “I Am at Home: Spatial Privacy Concerns with Social Media Check-Ins.” Procedia Computer Science 113: 551–558. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.08.278.

- Amirian, P., A. Basiri, G. Gales, A. Winstanley, and J. McDonald. 2015. “The Next Generation of Navigational Services Using OpenStreetMap Data: The Integration of Augmented Reality and Graph Databases.” In OpenStreetMap in GIScience, edited by J. J. Arsanjani, A. Zipf, P. Mooney, and M. Helbich, 211–228. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-14280-7

- Antoniou, V., and A. Skopeliti. 2017. “The Impact of the Contribution Microenvironment on Data Quality: The Case of OSM.” Mapping and the Citizen Sensor 165–196. https://www.ubiquitypress.com/site/books/10.5334/bbf/download/1638/#page=174

- Arsanjani, J. J., P. Mooney, A. Zipf, and A. Schauss. 2015. “Quality Assessment of the Contributed Land Use Information from OpenStreetmap versus Authoritative Datasets.” In OpenStreetmap in GIScience, edited by J. J. Arsanjani, A. Zipf, P. Mooney, and M. Helbich, 37–58. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-14280-7

- Ataei, M., A. Degbelo, and C. Kray. 2018. “Privacy Theory in Practice: Designing a User Interface for Managing Location Privacy on Mobile Devices.” Journal of Location Based Services 12 (3–4): 141–178. doi:10.1080/17489725.2018.1511839.

- Basiri, A., M. Jackson, P. Amirian, A. Pourabdollah, M. Sester, and A. Winstanley, et al. 2016. “Quality Assessment of OpenStreetMap Data Using Trajectory Mining.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 19 (1): 56–68. doi:10.1080/10095020.2016.1151213.

- Bégin, D. R. D., and S. Roche. 2017. “Contributors’ Enrollment in Collaborative Online Communities: The Case of OpenStreetmap.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 20 (3): 282–295. doi:10.1080/10095020.2017.1370177.

- Borkowska, S., and K. Pokonieczny. 2022. “Analysis of OpenStreetmap Data Quality for Selected Counties in Poland in Terms of Sustainable Development.” Sustainability 14 (7): 3728. doi:10.3390/su14073728.

- Borning, A., and M. Muller. 2012. “Next Steps for Value Sensitive Design.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1125–1134. Austin, TX: ACM.

- Brinkman, B., C. Flick, D. Gotterbarn, K. Miller, K. Vazansky, and M. J. Wolf. 2017. “Listening to Professional Voices: Draft 2 of the ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct.” Communications of the ACM 60 (5): 105–111. doi:10.1145/3072528.

- Business Dictionary. 2019. “Values Definition.” Accessed 27 April 2021. http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/values.html

- Bynum, T. W. 2017. “Ethics, Information, and Our ‘It-From-Bit’.” Universe. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.02029.

- Cavoukian, A. 2010. “Privacy by Design: The Definitive Workshop. A Foreword by Ann Cavoukian.” Ph D Identity in the Information Society 3 (2): 247–251. doi:10.1007/s12394-010-0062-y.

- Chen, T. W., and S. S. Sundar. 2018. “This App Would Like to Use Your Current Location to Better Serve You: Importance of User Assent and System Transparency in Personalized Mobile Services.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 21–26. Montreal, QC: ACM.

- Cho, G. 2014. “Some Legal Concerns with the Use of Crowd-Sourced Geospatial Information.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 20 (1): 012040. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/20/1/012040.

- D’-Antonio, F., P. Fogliaroni, and T. Kauppinen. 2014. “VGI Edit History Reveals Data Trustworthiness and User Reputation.” In Proceedings of the 17thAGILE international conference on geographic information science, 4–8. Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- Doytsher, Y., B. Galon, and Y. Kanza. 2012. “Querying Socio-Spatial Networks on the World-Wide Web.” In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web, 329–332. Lyon, France.

- Dror, T., S. Dalyot, and Y. Doytsher. 2015. “Quantitative Evaluation of Volunteered Geographic Information Paradigms: Social Location-Based Services Case Study.” Survey Review 47 (344): 349–362. doi:10.1179/1752270615Y.0000000013.

- Elwood, S., and A. Leszczynski. 2011. “Privacy, Reconsidered: New Representations, Data Practices, and the Geoweb.” Geoforum 42 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.08.003.

- Fan, H., A. Zipf, Q. Fu, and P. Neis. 2014. “Quality Assessment for Building Footprints Data on OpenStreetmap.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 28 (4): 700–719. doi:10.1080/13658816.2013.867495.

- Fogliaroni, P., F. D’-Antonio, and E. Clementini. 2018. “Data Trustworthiness and User Reputation as Indicators of VGI Quality.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 21 (3): 213–233. doi:10.1080/10095020.2018.1496556.

- Friedman, B., and D. G. Hendry. 2019. “Value Sensitive Design: Shaping Technology with Moral Imagination.” Design and Culture 12 (1): 109–111.

- Friedman, B., D. G. Hendry, and A. Borning. 2017. “A Survey of Value Sensitive Design Methods.” Foundations and Trends in Human-Computer Interaction 11 (2): 63–125. doi:10.1561/1100000015.

- Friedman, B., and P. H. Kahn Jr. 2007. “Human Values, Ethics, and Design.” In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook, edited by J. Jacko, and A. Sears, 1267–1292. Dordrecht: CRC Press.

- Friedman, B., P. H. Kahn, A. Borning, and A. Huldtgren. 2013. “Value Sensitive Design and Information Systems.” In Early Engagement and New Technologies: Opening Up the Laboratory, 55–95. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000015

- Haklay, M., A. Singleton, and C. Parker. 2008. “Web Mapping 2.0: The Neogeography of the GeoWeb.” Geography Compass 2 (6): 2011–2039. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00167.x.

- Haklay, M., and P. Weber. 2008. “Openstreetmap: User-Generated Street Maps.” IEEE Pervasive Computing 7 (4): 12–18. doi:10.1109/MPRV.2008.80.

- Hashemi, P., and R. A. Abbaspour. 2015. “Assessment of Logical Consistency in OpenStreetmap Based on the Spatial Similarity Concept.” In Openstreetmap in Giscience, edited by J. J. Arsanjani, A. Zipf, P. Mooney, and M. Helbich, 19–36. Cham: Springer.

- Huldtgren, A. 2015. “Design for Values in ICT Information and Communication Technologies.” In Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design. edited by J. van den Hoven, P. E. Vermaas, and I. van de Poel, 739–767. Berlin: Springer Netherlands.

- Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). 2011. “IT Ethical Code in India.” Accessed 27 April 2021. http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3115.

- Li, C., B. Palanisamy, and P. Krishnamurthy. 2018, June. “Reversible Data Perturbation Techniques for Multi-Level Privacy-Preserving Data Publication.” In International Conference on Big Data, Seattle, WA, USA, 26–42. Cham: Springer.

- Meng, L. 2020. “An IEEE Value Loop of Human-Technology Collaboration in Geospatial Information Science.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 23 (1): 61–67. doi:10.1080/10095020.2020.1718004.

- Miles, C. 2017. “Blockchain Security: What Keeps Your Transaction Data Safe?” published on IBM. Accessed 27 April 2021. https://www.ibm.com/blogs/blockchain/2017/12/blockchain-security-what-keeps-yourtransaction-data-safe/

- Mooney, P., and M. Minghini. 2017. “A Review of OpenStreetmap Data.” In Mapping and the Citizen Sensor, edited by G. Foody, L. See, S. Fritz, et al., 37–59. London, UK: Ubiquity Press.

- Mooney, P., A.M. Olteanu-Raimond, G. Touya, N. Juul, S. Alvanides, and N. Kerle. 2017. “Considerations of Privacy, Ethics and Legal Issues in Volunteered Geographic Information.” In Mapping and the Citizen Sensor, edited by G. Foody, L. See, S. Fritz, P. Mooney, A.-M. Olteanu-Raimond, C. C. Fonte, V. Antoniou, 119–135. London, England: Ubiquity Press Ltd.

- Olteanu‐raimond, A. M., G. Hart, G. M. Foody, G. Touya, T. Kellenberger, and D. Demetriou. 2017. “The Scale of VGI in Map Production: A Perspective on European National Mapping Agencies.” Transactions in GIS 21 (1): 74–90. doi:10.1111/tgis.12189.

- Regulation, 2016/679. 2016 “General Data Protection Regulation: Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/ec.” Official Journal of the European Union 119:1–88.

- Salk, C. F., T. Sturn, L. See, S. Fritz, and C. Perger. 2016. “Assessing Quality of Volunteer Crowdsourcing Contributions: Lessons from the Cropland Capture Game.” International Journal of Digital Earth 9 (4): 410–426. doi:10.1080/17538947.2015.1039609.

- Schmidt, F. A. 2013, September. “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Why Crowdsourcing Needs Ethics.” In 2013 International Conference on Cloud and Green Computing, 531–535. Karlsruhe, Germany: IEEE.

- Schröder-Bergen, S., G. Glasze, B. Michel, and F. Dammann. 2021. “De/colonizing OpenStreetmap? Local Mappers, Humanitarian and Commercial Actors and the Changing Modes of Collaborative Mapping.” GeoJournal. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10708-021-10547-7.

- Shen, N., J. Yang, K. Yuan, C. Fu, and C. Jia. 2016. “An Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Location Sharing Mechanism.” Computer Standards and Interfaces 44: 102–109. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2015.06.001.

- Shneiderman, B., and C. Plaisant. 2010. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction. India: Pearson Education.

- Smith, H. J., T. Dinev, and H. Xu.2011. Information Privacy Research: An Interdisciplinary Review. MIS Quarterly 989–1015.

- Standing, S., and C. Standing. 2018. “The Ethical Use of Crowdsourcing.” Business Ethics: A European Review 27 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1111/beer.12173.

- Sula, C. A. 2016. “Research Ethics in an Age of Big Data.” Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology 42 (2): 17–21. doi:10.1002/bul2.2016.1720420207.

- Westin, A. F. 2003. “Social and Political Dimensions of Privacy.” The Journal of Social Issues 59 (2): 431–453. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00072.

- Zhang, P., and D. F. Galletta. 2006. Human-Computer Interaction and Management Information Systems: Foundations. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

- Zook, M., M. Graham, T. Shelton, and S. Gorman. 2010. “Volunteered Geographic Information and Crowdsourcing Disaster Relief: A Case Study of the Haitian Earthquake.” World Medical and Health Policy 2 (2): 7–33. doi:10.2202/1948-4682.1069.

Appendix A

Table A1. Ethical value clauses cited from OSM’s codes of conduct, drafts, and suggested codes, categorized according to their topic.

empirically compares the clauses cited in within the stakeholders’ potential expectations and requirements in literature. Next to the mapped expectation/requirements, reference numbers of those clauses appear. “n” indicates that the value does not comply with the existing literature and presents an identified conflict between these clauses and the assessed values of stakeholders, while “y” indicates the opposite.

Table A2. Ethical values, expectations, and interests of the seven main groups of stakeholders.

Table A3. Commitments of HOT members.

Appendix B

List of OSM links

1. OpenStreetMap Wiki

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Main_Page

2. List of OSM-based services – OpenStreetMap Wiki

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/List_of_OSM-based_services#Export

3. Good practice – OpenStreetMap Wiki

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Good_practice

4. Copyright – OpenStreetMap Wiki

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Copyright

5. Licence/Contributor Terms – OpenStreetMap Foundation (osmfoundation.org)

https://wiki.osmfoundation.org/wiki/Licence/Contributor_Terms

6. OpenStreetMap Foundation (osmfoundation.org)

https://wiki.osmfoundation.org/wiki/Main_Page

7. Privacy Policy – OpenStreetMap Foundation (osmfoundation.org)

https://wiki.osmfoundation.org/wiki/Privacy_Policy

8. Etiquette – OpenStreetMap Wiki

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Etiquette

9. codes-of-conduct/code_of_conduct.md at master · osmlab/codes-of-conduct · GitHub

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Etiquette

10. Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team | Data Lead (hotosm.org)

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Etiquette

11. Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team | What We Do (hotosm.org)

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Etiquette

12. Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team | HOT Code of Conduct (hotosm.org)