ABSTRACT

Gelugpa is the most influential extant religious sect of Tibetan Buddhism, which is the spiritual prop for Tibetans, with thousands of monasteries and followers in Tibetan areas of China. Studies on the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa can not only reveal its historical geographical development but also lay the foundation for anticipating its future development trend. However, existing studies on Gelugpa lack geographical perspective, making it difficult to explore the spatial characteristics. Furthermore, the prevailing macro-perspective overlooks spatiotemporal heterogeneity in diffusion processes. Therefore, taking monastery as the carrier, this study establishes a multi-level diffusion model to reconstruct the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries, as well as a framework to explore the detailed features in the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa in Tibetan areas of China based on a geodatabase of Gelugpa monastery. The results show that the multi-level diffusion model has a considerable applicability in the reconstruction of the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries. Gelugpa monasteries in the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas present disparate spatial diffusion processes with diverse diffusion bases, speeds, stages, as well as diffusion regions and centers. A powerful single-center diffusion-centered Gandan Monastery was rapidly formed in U-Tsang. Kham experienced a slower and more varied spatial diffusion process with multiple diffusion systems far apart from each other. The spatial diffusion process of Amdo was the most complex, with the highest diffusion intensity. Amdo possessed the most influential diffusion centers, with different diffusion shapes and diffusion ranges crossing and overlapping with each other. Multiple natural and human factors may contribute to the formation of Gelugpa monasteries. This study contributes to the understanding of the geography of Gelugpa and provides reference to studies on religion diffusion.

1. Introduction

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Mahayana Buddhism stemming from the latest stages of Indian Buddhism and is practiced in Tibetan areas of China with local Bon Religion. It is the product of the unique geographical and cultural environment of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China (Wang Citation2009). For thousands of years, Tibetan Buddhism has been acting as the spiritual prop for Tibetans since its formal formation in Tubo in the 8th century (Huang Citation2010). Along with the transformation of Tibetan society’s socioeconomic and political environment, Tibetan Buddhism has evolved into five major religious sects, including Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, Kadam, and Gelugpa. Gelugpa was founded by Tsongkhapa in 1409, which was marked by the establishment of Gandan Monastery. Although being the youngest, Gelugpa has been widely believed in and become the most influential existing religious sect, with thousands of monasteries and Buddhist followers spreading all over the Tibet (Li Citation2013). Research on the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa from geographical perspective can not only reveal the historical geographical development of Gelugpa through its spatial and temporal heterogeneity but also imply its future development trend. Some scientific evidences may be provided for the protection of Gelugpa culture and religious policy-making. As the main place for monks and believers worshiping, meditating, and studying Tibetan Buddhist doctrine and culture, Gelugpa monastery can serve as the study carrier of spatial diffusion, owing to its georeferencing and attributes indicating when it was built and where it came from.

Historically, the expansion of Gelugpa was tightly connected with the political pattern of Tibetan society. Some studies have been made to disclose the development process of Gelugpa and related historical juncture of Tibetan society based on a series of important Gelugpa monasteries (Wang Citation2010; Dai and Du Citation2012; Norpu Citation2012; Niu Citation2016). Currently, the studies related to Gelugpa monasteries spread are often conducted in the different parts of Tibet in a historical perspective, partly with the incorporation of statistical methods (Zhu Citation2006; Wang Citation2011; Xia-wu-li-jia Citation2014; Yang Citation2015). Up till now, the lack of geographical view and geo-referenced monastery data makes it difficult to detect diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries in space.

Geographers have long been interested in the diffusion of innovations, and this is an area of geography and religion where principles and concepts can be borrowed from other areas of geographical inquiry. The seminal theory of spatial diffusion was set forth by Torsten Hagerstrand in 1953 (Hagerstrand Citation1953; Morrill, Gaile, and Thrall Citation1988). Hagerstrand discovered that the contact network of most people to be quite localized; thus, the diffusion of innovation should likewise be local, spreading from person to person in a contagious manner. Moreover, he formalized diffusion as a temporal process that can be divided into different phases: an early period of pioneering, a middle period of diffusion and fastest change and a later period of “condensing” and saturation (Morrill, Gaile, and Thrall Citation1988). Following the hierarchical phenomenon discovered by Hagerstrand, hierarchical diffusion is proposed by scholars in which innovations are adopted from the top of the hierarchy down, as they found some phenomena involved a higher threshold cost for acceptance (Morrill, Gaile, and Thrall Citation1988). Park gave an overview that a standard typology of diffusion processes recognized two main types, such as relocation diffusion and expansion diffusion, which can be further subdivided into contagious diffusion and hierarchical diffusion. When it comes to the principles of religious diffusion, Park holds that the most common type of diffusion process for religion is contagious diffusion, which takes place by contact conversion as a product of everyday contact between believers and nonbelievers. Hierarchical diffusion of religion occurred when missionaries deliberately sought to convert as tribal leaders, in the hope that their people would follow. Missionaries introducing religion in new areas fall into the category of relocation diffusion (Park Citation1994).

Among the several models to operationalize the theory of spatial diffusion, the “mean information field” (MIF), proposed by Hagerstrand is considered to be the most notable early quantitative model of spatial diffusion processes (Hagerstrand Citation1966). Variants of the Hagerstrand model were classified as stochastic and deterministic, with stochastic models allowing randomness within the spatial diffusion process, while geographic phenomenon diffuses according to fixed forms in deterministic models (Morrill, Gaile, and Thrall Citation1988). In addition, the early progresses in mathematical approaches to diffusion modeling is discussed, including general interaction diffusion models (Beckmann Citation1970; Haynes and Fotheringham Citation1984), epidemiology models (Kendall Citation1965) and spatial-temporal models (Cliff and Ord Citation1975; Haining Citation1983). Multiple quantitative methods and models have been widely used in the detection of spatial diffusion processes for the past several years in many fields (Tita and Cohen Citation2004; Coldefy and Curtis Citation2010; Lee et al. Citation2014; Yang et al. Citation2019; Griffith and Li Citation2021).

Inherited in the theory and research methods of spatial diffusion, religion diffusion processes can be better understood through space and time. Park (Citation1994) made the first attempt to explore the relationships between geography and religion. Through comprehensive historical and archeological study, he proposed principles of religious diffusion and painted thumbnail sketches of how the main religions arose and spread. In recent years, the diffusion studies on different religions all over the world have vigorously expanded. Otterstrom (Citation2012) developed a model of Mormon spatial diffusion, based on which the international diffusion and growth of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were studied. Based on a core-periphery GIS model, Ryavec and Henderson (Citation2015) presented the historical growth and spread of Islam in China based on a dataset of 1,774 mosques. Zhao et al. (Citation2017) examines the diffusion process of the religious institutions of Buddhism, Daoism, and Christianity in coastal China, utilizing the nearest neighbor analysis and regression curve estimation to statistically detect the type of spatial diffusion process and the SatScan software to establish the significance of clusters of each religious establishment across space and time. However, most of the studies on religion diffusion confused spatial diffusion processes with spatiotemporal distributions, neglecting the important elements in diffusion such as origin, destination, and flow.

So far, nearly all research on the spread and development of Tibetan Buddhism have been carried out from a historical perspective. The diffusion of Tibetan Buddhism monasteries is usually studied based on statistical methods. The lack of geographical view and geo-referenced monastery data makes it difficult to detect diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries in space. Chao, Zhao, and Liu (Citation2021) quantitatively analyzed spatial patterns of Gelugpa monasteries at three scales of Tibetan Inhabited Regions. However, because of lack of monastery source data at the time, the spatial diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries remained unknown. Moreover, most of the existing studies on spatial diffusion processes of religion are conducted by observing spatial pattern at each temporal stage, and then linking up the spatial patterns temporally from a macro-perspective. However, due to the diversity and complexity of Gelugpa’s surroundings, the spatial diffusion processes of the Gelugpa monasteries present spatial and temporal heterogeneity in Tibetan Inhabited Areas, which cannot be entirely understood in a macroscopic scale. In order to figure out the detailed spatial diffusion characteristics of Gelugpa monasteries, rather than only the general diffusion law, detailed diffusion networks need to be reconstructed, conveying the information about the origin, the multi-level agents through which further spread occur, and the possible geographical flow for the spread.

Therefore, this study aims to quantitatively explore the detailed spatial diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries in geographical perspective through the following three steps: (1) build a multi-level diffusion model to reconstruct the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries; (2) reveal the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries quantitatively based on the diffusion networks, through diffusion bases, speeds, stages, as well as regions and centers; (3) illustrate the diffusion mechanizations of Gelugpa monasteries. This study can contribute to a deeper understanding of the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries and provide a reference for the diffusion studies of other religion or cultural phenomenon.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

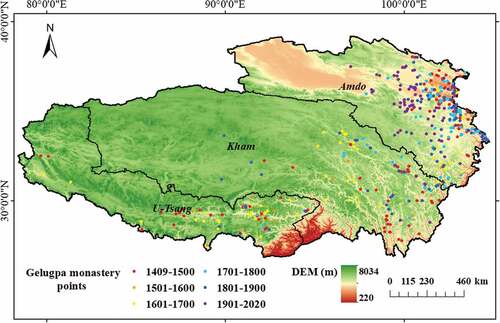

The Tibetan areas in China are the major activity region of Gelugpa, the accurate boundaries of which have changed throughout time. Traditional Tibetan spatial concepts treat the geography of Tibet as consisting of a western “upper” region of Ngari, a central “middle” region of U-Tsang, and eastern “lower” regions of Kham and Amdo (Ryavec Citation2015). Ngari, at its greatest extent, stretching from the Gungtang and Saga areas as far west as Ladakh, came to be considered the western part of the Tibetan Plateau proper over time. U-Tsang is centered on Tibet’s main city of Lhasa and mostly lies in the watershed of the great Yarlung Tsangpo, with the western districts surrounding and extending past Mount Kailash, and much of the vast high altitude Changtang plateau to the north. Kham has rugged terrain characterized by mountain ranges and gorges, through which numerous rivers, including the Mekong, Yangtse, Salween, and Yalong Jiang flowing. Amdo encompasses a large area from the Yellow River to the Yangtze River and is the birthplace of Tsongkhapa (the founder of Gelugpa). Based on the dialects, Tibet has been divided into three specific regions, as U-Tsang (Ngari is considered as a part of U-Tsang), Kham, and Amdo since the Yuan Dynasty. The three Tibetan regions currently cover parts of five provinces (Tibet Autonomous Region, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan) of China. shows the geographical location and extent of the study area.

2.2. Data and preprocessing

The historical Gelugpa monastery information is mainly acquired from the Series of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in China (Pu Citation2013), with the “basic information system of religious activity places” (http://www.sara.gov.cn/zjhdcsjbxx/index.jhtml) of National Religious Affairs Administration and field investigation as the supplement. The Series of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in China is a six-volume set that contains a detailed overview of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, describe in detail the name, location, history, religious sect, builder, the architecture of every monastery, and so on. The dataset of Gelugpa monastery is generated by obtaining historical geographic information about Gelugpa monastery from the sources, which includes three main kinds of information as geographical locations, years of monastery construction, and sources of monastery.

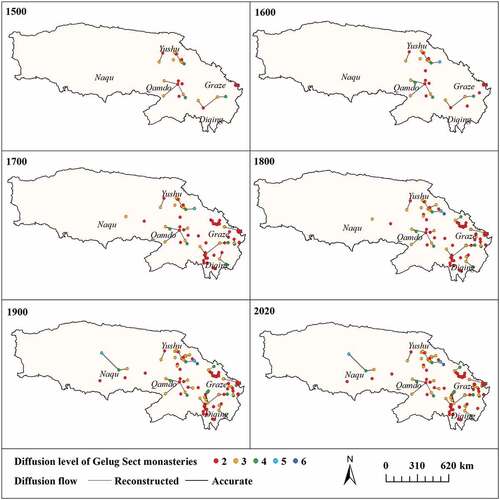

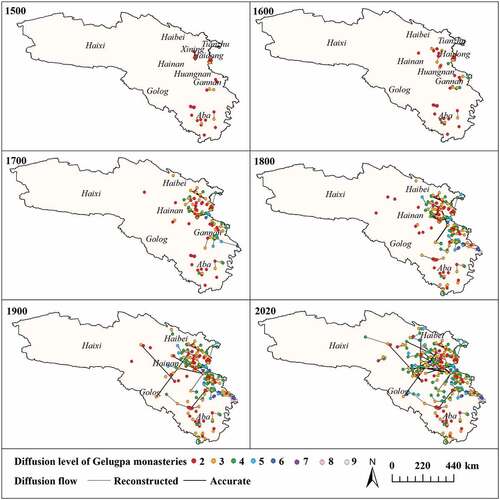

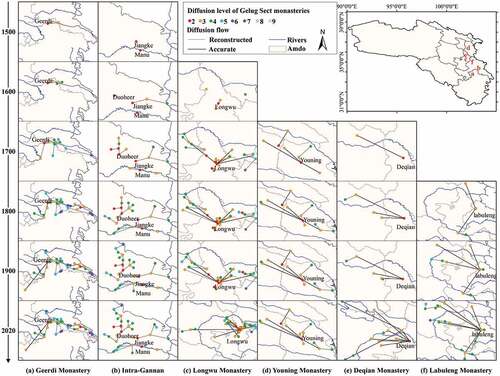

In the data processing, the geographical coordinate of each Gelugpa monastery is validated in absolute longitude and latitude coordinates through the software BIGEMAP, according to the description of where the monastery is located. The locations of monasteries are usually described in the form of relative position between monasteries and natural landscapes (mountains and rivers) or human landscapes (settlements). There are differences in positioning accuracy among monasteries with multiple levels of detail in geographical descriptions. The median value of the ambiguous construction period is chosen as the built year of the monastery (e.g., 1450 is picked as the exact value of mid-15th century). According to previous literature, Gelugpa monasteries are either directly constructed by disseminators or converted from other religious sect monasteries by subtle influence of Gelugpa culture. The older monastery where the builder of a certain monastery came from or used to study can be deemed as the origin of place. The “monastery to monastery” spreads by monks constitute the spatial diffusion processes of the Gelugpa monasteries under micro perspective. The geographical coordinates of the origins of monasteries are also recorded. After processing, a dataset of Gelugpa monasteries is completed which records the coordinates of each monastery and its origin as well as the construction year. Through geocoding the dataset of Gelugpa monastery with ArcGIS, the geodatabase of Gelugpa monastery is established, where georeferenced Gelugpa monastery point data are stored. Monastery points are rearranged into six groups, with about a century being a research period. All grouped monastery points are shown in .

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Framework of the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries

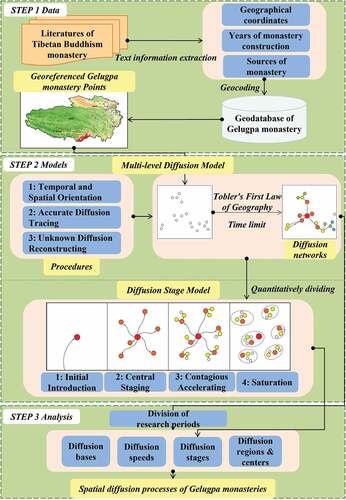

The main processes of the framework include three steps: data, models, and analysis of spatial diffusion processes (). The collection and preprocessing of Gelugpa monastery data, as the basic work, have been described in Section 2.2.

The key to performing the analysis is the construction of a multi-level diffusion model. In the multi-level diffusion model module, after procedures: spatiotemporal point positioning, accurate diffusion tracing, and unknown diffusion reconstructing, the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries across the whole Tibetan areas in China were obtained from monastery points (Section 2.3.2).

A diffusion stage model was built to quantitatively divide the diffusion phases of Gelugpa monasteries in the three Tibetan Inhabited Areas. According to the proportion of Gelugpa monasteries of diverse diffusion levels in the diffusion networks, the diffusion of Gelugpa monasteries can be divided into four phases: initial introduction, central staging, contagious accelerating, and saturation (Section 2.3.3).

During the analysis of the results module, based on the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries, the spatial diffusion processes inside the three Tibetan Inhabited Areas were analyzed from four aspects: diffusion bases, diffusion speeds, diffusion stages, as well as diffusion regions and centers.

2.3.2. Multi-Level diffusion model

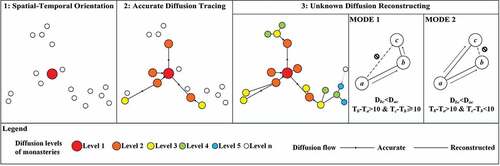

In order to study the microscopic characteristics of spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries, diffusion networks with origin, multi-level agents, and diffusion flows need to be clarified. According to the investigation, there is a total of 549 Gelugpa monasteries containing location and construction year information, while 224 of them have recorded origin, which means 40.8% of the diffusions can be acquired accurately. The rest 59.2% of the diffusions remain to be reconstructed. Thus, a multi-level diffusion model for Gelugpa monasteries is designed in a three-step process: spatiotemporal point positioning, accurate diffusion tracing, and unknown diffusion reconstructing ().

The investigation has found that most of the traceable diffusions of Gelugpa monasteries are triggered by the three categories of disseminators: the eminent monks from the hinterland of Tibet (e.g. the disciples of Tsongkhapa), local monks who used to be trained in Lhasa, and monks from other monasteries. The specific origins of the other diffusions are untraceable. For example, local monks built monasteries due to the gradual influence of Gelugpa. Conversion happened when they were infiltrated by cultural or political factors. The investigation shows that, apart from the long-distance relocation diffusion involving famous monasteries, most of the unknown Gelugpa monasteries follow short-distance contagious diffusion. Therefore, considering the diffusion pattern of the majority of the unknown monasteries, the unknown diffusions are designed to be reconstructed based on the principles of contagious diffusion.

Contagious diffusion in religion can be defined as the distance-controlled spreading of beliefs through people who are in contact with belief systems, characterized by its spread distance from near to far. Consistent with the many-to-one relationships in contagious diffusion model, the establishment of a certain Gelugpa monastery was inevitably affected by religious culture from more than one surrounding Gelugpa monastery. In this paper, according to Tobler’s First Law of Geography (everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things) (Tobler Citation1970), the nearest earlier monastery a is chosen as the origin of monastery b, to reconstruct the one-to-one relationship of monastery diffusion. In the circumstances of the distance between monasteries Dbc<Dac, if the construction time Tb-Tc ≥10, then monastery b can be considered to be the direct origin of monastery c, as shown in mode 1 of . In another case, if Tb-Tc <10, then it can be considered that monastery b and monastery c were built around the same period and shared the same direct origin, monastery a, as shown in mode 2 of .

2.3.3. Diffusion stage model

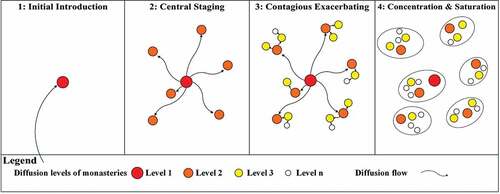

In this paper, the diffusion-stage model is designed to divide different diffusion stages of Gelugpa monasteries. This model follows Hagerstrand (Citation1952) who placed the three regularities of diffusion into an interrelated framework (the S-shape curve for diffusion through time, the hierarchy effect, and the neighborhood effect) (Brown Citation1981) and Otterstrom (Citation2012) who revised Hagerstrand’s diffusion framework with four Mormon specific diffusion phases, rather than the three stages of Hagerstrand. Both of Hagerstrand and Otterstrom’s models guide the development of the diffusion-stage model and parallel the main hypothesis of this study: historical Gelugpa diffusion within various regions of Tibetan Inhabited Areas involves a common pattern of initial introduction of monastery in local religious center first, then followed by the successive establishment of monasteries which are centered on it. The diffusion of monasteries is divided into four stages in the diffusion-stage model, as shown in .

Stage one is the “Initial Introduction” period. Taking the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas as study units, the Gelugpa monasteries, which are directly introduced into the locality from the outside, are identified as the initial-introduced monasteries. The judgment of initial-introduced monastery is immune from introduction time. When initial-introduced monasteries account for hold a clear majority, the period is judged to be the initial introduction, which usually happens in the initial stage of diffusion.

Stage two is the “Central Staging” period. This period presents obvious characteristics of hierarchical diffusion and initially introduced monasteries act as central points of diffusion in the region. The Gelugpa monasteries directly stemming from initially introduced monasteries are deemed as secondary ones. When the number of secondary monasteries exceeds initial-introduced monasteries, it means Gelugpa culture is being extensively sent to other “virgin land”, which are often the large order areas in this region. The “Central Staging” period marks the full start of local diffusion.

Stage three entitled “Contagious Exacerbating” is marked by the domination of the creation of level 3 and below monasteries, emanating from the secondary monasteries. Apart from the manifestation of a hierarchical pattern, the diffusion appears as a multi-level short-distance contagious pattern near the central monasteries. The additional monasteries act as new dispersion sources for the diffusion of the Gelugpa. More people in lower-order areas will be exposed to the religion by the Gelugpa monasteries because of the more accessible proximity to the religious innovation. This occurrence brings a region to the last phase of the diffusion model.

The final stage is termed “Concentration and Saturation”. As the monasteries spread out across a country, monastery activities become more localized. Small towns and rural areas can be more easily reached by monasteries, and new monastery units are organized in these places. As a result of all those in the population who would adopt Gelugpa, nearly all diffusions have ceased. Finally, the number of monasteries tends to be saturated in the region.

Each region of Tibetan Inhabited Areas is unique in population size, area, and shape, religious component, and rural/urban makeup, so the spatial manifestation of the diffusion stages will vary among regions. Consequently, some regions may not follow a complete outlined pattern.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Results

3.1.1. Diffusion bases of Gelugpa monasteries

It did not take long for Gelugpa to spread influence outward from its origin, Lhasa, since 1409. Unexpectedly, Gelugpa did not spread to Shigatse first, which was close to Lhasa. Instead, Yushu in Kham was the first stop to accept Tsongkhapa’s doctrine. Yushu region and Hehuang basin were two of the first areas of Qinghai where Gelugpa monasteries were located (Pu Citation2001, 170). Due to Tsongkhapa’s travel experience in Yushu since 1372, Gelugpa spread directly to Yushu soon after its founding. Ga-er-la-de-qin-lin Monastery was the first Gelugpa monastery in Yushu after its conversion from Drikung Kagyu School (Xia-wu-li-jia Citation2014).

The initial diffusion of Gelugpa relied on the mentorship. Disciples of Tsongkhapa brought his thoughts and doctrines throughout the whole Tibet, especially in the early stage of development. Before 1419, Ka-ling-pa-ngag-dbang-grags-pa returned hometown, Ngari, got support from the royal family of Guge Kingdom and seized the supreme power of religious affairs. Dui-xi-rao-sang-bu established Damo Monastery in Mangyu (today’s Jilong county), Ngari, after studying in Lhasa. Since then, almost all of the original monasteries in Ngari converted to Gelugpa (Huang Citation2016). Despite proximity to the origin, Lower Tsang (today’s Shigatse) was the last to be introduced in U-Tsang. shes-rab-seng-ge and dge-dun-grub propagated Esoteric Buddhism in Lower Tsang since receiving Tsongkhapa’s order in 1419. Dge-dun-grub built Bkra-shis-lhun-po Monastery, one of the four big Gelugpa monasteries, in 1447. However, Saijuba Monastery was built earlier than Bkra-shis-lhun-po Monastery in 1440, which deemed to be the beginning of Gelugpa’s diffusion in Lower Tsang (Wang Citation2010).

Due to the support from the Ming government, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Gansu-Qinghai region (part of Amdo) appeared to be explosive in growth. As the earliest Gelugpa monasteries of Gansu-Qinghai region, Honghua Monastery, Lingzang Monastery, and Jingning Monastery were founded in today’s Minhe. However, the Gelugpa monasteries had limited influence and did not show an intense increase, until the Mongolian Tribe migrated to Qinghai in mid and late stage of the Ming dynasty. In 1577, the Dalai Lama III, Bsod-nams-rgya-mtsho departed from Drepung Monastery to meet the leader of the Tumet tribe, Altan-Khan, in Yanghua Monastery. This journey was not only the second far-reaching missionary activity of Gelugpa in Gansu-Qinghai region but also the beginning of Mongolians’ conversion to Gelugpa. Since then, continuous monks preach there, expanding Gelugpa’s influence in Gansu-Qinghai region. In 1630s, the Khoshut tribe of Western Mongolia migrated southward to Qinghai and dominated the area in the name of religion protection, the leader of which supported Gelugpa vigorously (Dai and Du Citation2012). As a result, the late Ming and early Qing dynasty witnessed the establishment of a group of influential monasteries with numerous ancillary monasteries in Gansu-Qinghai region, including Youning Monastery, Guanghui Monastery, Deqian Monastery, Quezang Monastery, etc.

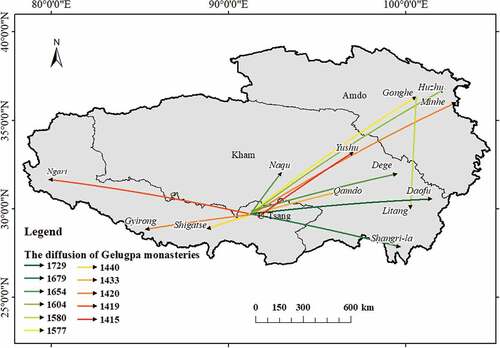

It was not until 1430s that the first locally established Gelugpa monastery appeared in Yushu. Jian-zan-seng-ge and mai-xi-rao-sang-bu returned to Kham from Lhasa and established Naitang Monastery and Galden Jampaling Monastery in Qamdo, respectively. However, the influence of Gelugpa did not cross the Jinsha River in a long time after Galden Jampaling Monastery’s establishment, which was not changed until the Dalai Lama III’s arrival. After the meeting with Altan-Khan in Qinghai, Bsod-nams-rgya-mtsho was invited by the Chieftains Mu of Lijiang to Litang and Batang, the center of South Kham. In 1580, he converted Banggen Monastery (a Bon monastery), named Litang Monastery in Litang, which was the first Gelugpa monastery on the east side of the Jinsha River in Kham. Qu-ji-ang-wen-peng-cuo, the disciple of the Dalai Lama V, was sent to Kham to preach and built the first Gelugpa monastery in North Kham (Gengsa Monastery in Dege) with the help of Chieftains Dege in 1655. With Gengsa Monastery being the main monastery, the Thirteen Hor Monasteries were successively established, greatly influencing the religious structure of South and East Kham. Huiyuan Monastery was an important East Kham Gelugpa monastery established by the order of Emperor Yongzheng in 1729. The first Gelugpa monastery in the southernmost of Kham, Shangri-la, was Ganden Sumtseling Monastery initiated by war in 1679, while Zandan Monastery was the first one in North Tibet (Wang Citation2010). The early diffusion of Gelugpa monastery are shown in .

3.1.2. Diffusion speeds of Gelugpa monasteries

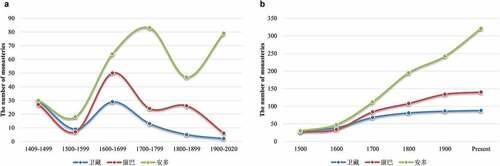

The diffusion speeds of Gelugpa monasteries are composed of growth rate and cumulative level, both of which directly depend on the number of monasteries in different periods. As shown in , there are large differences in diffusion speeds of Gelugpa monasteries among the three Tibetan Inhabited Areas. As early as the mid-15th century, Gelugpa had diffused throughout the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas. In the first 100 years, the Gelugpa monastery group had formed with wide coverage area, solid economic and political strength, which was stronger than other religious sects. According to the statistics of the number of monasteries, Gelugpa initiated with similar diffusion speed in the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas during 1409–1500. Gelugpa suffered enormous obstacles during 1500–1600, while the diffusion speed of monasteries in all the three areas decreased significantly. Along with the rapid development of Gelugpa, the contradictions between Gelugpa and other sects were becoming increasingly acute in this period. Since the end of 15th century, supported by the Pagmodru regime, Tumet tribe and Khoshut tribe, Gelugpa had struggled with Karma Kagyu and the Rinpungpa regime, the Tsangpa regime and Choghtu Khong Tayiji from Northern Khalkha behind it for over a hundred years (Norpu Citation2012). Gelugpa was severely buffeted in the complex social environment with religious and political struggles intertwined. The third hundred years witnessed the take-off of the growth rate of Gelugpa monasteries. Both U-Tsang and Kham reached the peak of the diffusion of Gelugpa monasteries. Although the contradictions among political and religious powers had not cooled in the early 17th century, with the establishment of the Ganden Phodrang by the 5th Dalai Lama and Tibet’s patron Güshi Khan of the Khoshut in 1642, Gelugpa overcame this difficult situation and faced a completely new situation. The rapid expansion also coincided with the reign of the 5th Dalai Lama, who was widely regarded as the most influential Tibetan living Buddha. Due to his effort, Gelugpa reached its peak, spreading all over the Tibetan Inhabited Areas and becoming the strongest religious sect. As the 17th century began, the diffusion speed of U-Tsang and Kham slowed down, while Amdo continued to accelerate. The difference may result from continuing war, such as the Dzungars’ and the Gurkhas’ invasions in Tibet (Chen and Gao Citation2003). Amdo, which was far from the politico-religious center, had a more peaceful environment for Gelugpa monasteries’ diffusion. During 1800–1900, despite the diffusion speed of Amdo slowed down, it remained about twice as fast as Kham, while the diffusion speed of U-Tsang decreased further. The last hundred years was a mixture of first-half turbulent social background and a second-half stable development stage. The diffusions of U-Tsang and Kham were at a near-standstill, which is obvious in the nearly horizontal cumulative-level curve segments ()). In contrast, the re-rising curve of Amdo indicates that the diffusion reaccelerates to another peak.

The horizontal comparison of diffusion speeds shows that despite there are common rules in the diffusion processes of the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas, some significant differences exist. The growth rate curves decline at first and then rise, finally decline overall. The curves of all cumulative levels approximate nonstandard S-shape, which is in accord with the classic diffusion regularity. Although with roughly equal start, the diffusion in Amdo was stronger and more lasting than U-Tsang and Kham. The Gelugpa monasteries of Amdo diffused much faster, especially since 18th century. Meanwhile, since 17th century, the Gelugpa monasteries of Amdo have maintained a rapid growth rate with its peak in 1700–1800, while the diffusions in U-Tsang and Kham declined to stagnation. On the contrary, it seems that the diffusions in U-Tsang and Kham experienced a synchronous and complete “life cycle”. However, the diffusion speed of Kham was almost twice as fast as U-Tsang in the late stage.

3.1.3. Diffusion stages of Gelugpa monasteries

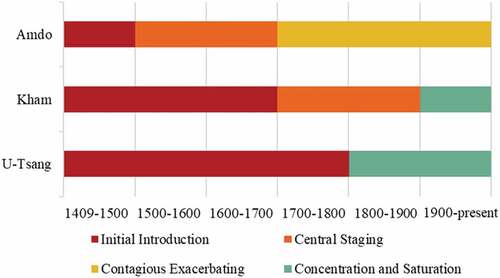

Based on multi-level agents in the diffusion networks, the diffusion stages of the three Tibetan Inhabited Areas are obtained from diffusion-stage model. It seems that all of U-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo experienced diverse but incomplete diffusion processes ().

As the birth land of Gelugpa, U-Tsang has a significant number of monasteries, most of which were directly diffused from Gandan Monastery. According to the statistics of the multi-level agents, the initially introduced monasteries in U-Tsang always accounted for over half of the total number. During 1409–1500 and 1700–1800, the proportion was as high as 76%. U-Tsang maintained the “Initial Introduction” stage in the first 400 years until the 19th century when the diffusion of U-Tsang appeared to be stalling. As shown in ), the cumulative level of U-Tsang tended to be horizontal gradually since 1800, which indicates the end of the diffusion phenomenon. Since then, U-Tsang entered the “Concentration and Saturation” stage. The missing of “Central Staging” and “Contagious Exacerbating” means that there was only one power diffusion center in the history of U-Tsang.

Kham’s first diffusion stage, “Initial Introduction”, lasting for three centuries, was slightly shorter than U-Tsang. The proportion of initially introduced monasteries of Kham was over 70% during 1500–1700, which was higher than the corresponding U-Tsang. As the initially introduced monasteries substantially declined in the 18th century, the secondary monasteries centered on the initial ones dominated the diffusions. However, the “diffusion chain” of Kham was not long due to lack of contagious diffusion. Even though the proportion of the lower-level Gelugpa monasteries in the “diffusion chain” was up to 31% during 1800–1900, it remained lower than that of the secondary monasteries. Subsequently, despite the proportion of the lower-level monasteries increased, Kham entered the “Concentration and Saturation” stage due to the cease of the diffusion ( (b)).

In Amdo, there was only the first hundred years that fell into the stage of “Initial Introduction”, in which the initially introduced monasteries accounted for 80%. The diffusion stage of Amdo switched to “Central Staging” soon during 1500–1700. However, it appeared that the “Central Staging” was not a typical one for the approximate proportion of multi-level monasteries in the “diffusion chain”. It means that a considerable number of external introductions and multi-level local contagions happened simultaneously. Since the 17th century, the contagious diffusion of Amdo exacerbated with the increased proportion of level 3 and below monasteries from 48% to 60%. As the contagious diffusion deepened in Amdo, the external input decreased and the localized diffusion of Gelugpa monasteries accelerated. Meanwhile, “Contagious Exacerbating” stage also suggests that the “diffusion chain” in Amdo lengthened increasingly. For Tibetan Buddhism, the long “diffusion chain” usually implies that there are more complex multi-level relationships of administrative subordination. Up till now, the curve of growth rate still rises with a 45° slope, which means that the quantity of Gelugpa monasteries in Amdo has not reached saturation and there is still space for further diffusion of Gelugpa monasteries ()).

It can be found that the “life cycle” of Gelugpa monastery diffusions decreased as the regions got closer to the origin, Lhasa. Moreover, the closer the distance, the shorter the “diffusion chain” was. Before the end of the diffusions, U-Tsang only experienced the first stage “Initial Introduction”, while Kham experienced the second stage “Central Staging”. Amdo experienced the most complete diffusion process and remained of great potential for further monastery diffusion. It appears that the diffusion center has shifted from U-Tsang, the religious center to Amdo, the marginal zone of central Tibetan areas in China.

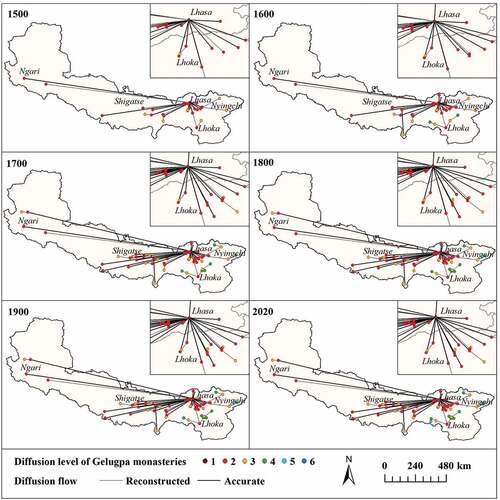

3.1.4. Diffusion regions and centers of Gelugpa monasteries

The diffusion networks of Gelugpa with origin, multi-level agents, and diffusion flows are clarified based on the multi-level diffusion model, through which the location-related diffusion regions and centers can be obtained. The spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries in U-Tsang are shown in . The research shows that the general diffusion pattern of Gelugpa monasteries in U-Tsang formed as early as the first 100 years, while the next 500 years kept the original features of the diffusion pattern. Gelugpa monasteries had already been established in nearly all main areas of U-Tsang during 1409–1500, originating from Lhasa to eastern Nyingchi on the East, central Lhoka on the South and western Ngari on the West.

Gandan Monastery, being the birthplace of Gelugpa, is the initiation point for Gelugpa’s diffusion networks not only in U-Tsang but across Tibet. According to the diffusion networks of Gelugpa, the monasteries which were built by the direct influence of Gandan Monastery account for approximately 67% of all monasteries in U-Tsang. Throughout the whole period, except the super diffusion center, Gandan Monastery, there were no other obvious diffusion center in U-Tsang, even Tashilhunpo Monastery, which were located and had huge influence in Shigatse (Lower Tsang).

The research also indicates that three monastery clusters gradually formed in Chengguan District of Lhasa, the north of Lhoka, and the east and middle of Shigatse. Among the three agglomeration regions, the density of the clusters on the west of Gandan Monastery in Chengguan was the largest. All these monasteries were the secondary monasteries which stemmed from Gandan Monastery. It is noteworthy that nearly all the monasteries in Chengguan were historically significant, among them some were pre-Gelugpa period monasteries. Under the influence of Gelugpa, many monasteries of other schools converted to Gelugpa, such as Jokhang Monastery and Ramoche Monastery in Chengguan. Most of the monasteries which were located at the border regions of Lhasa and Lhoka were also diffused directly from Gandan Monastery. However, their distribution density and influence were far smaller than that in Chengguan. The spread range of Gelugpa monasteries in Shigatse was much wider. A diffusion tendency from east to west emerged gradually. The diffusion in Shigatse was more than a single diffusion type. Instead, it is a mixed dual diffusion with relocation diffusion from Lhasa and contagious diffusion in the locality. The diffusions in Lhoka and Nyingchi can be considered as a similar one, contagious diffusion based on the introduction of a single point, while Ngari presented a long-distance relocation diffusion.

Compared with U-Tsang’s rapid formation of diffusion pattern, Kham experienced a slower and more variable spatial diffusion process (). The earliest diffusions of Gelugpa monasteries in Kham were mainly located in Qamdo, Yushu, and Graze, the distribution of which were relatively dispersed. Along with the introduction of Gelugpa outside from U-Tsang, the local diffusions were also developing. There were few diffusions in Kham during 1500–1600, most of which were in Graze and Yushu. This period was a turning point in Gelugpa’s diffusion in Kham. The diffusion center was moving from Qamdo to Graze. During 1600–1700, an outbreak of diffusion happened in the northeastern, central, and southwestern Graze, and the northern Diqing. Since then, Gelugpa monasteries spread all over Graze with its influence surpassing Qamdo and Yushu. During 1700–1800, it was more obvious that the diffusion of Gelugpa monasteries was concentrated in the eastern Kham, running north to south through Graze. In 1800–1900, the diffusions were still centered in Graze and the coverage was larger. Except for Graze, the diffusion phenomenon of Gelugpa monasteries in Kham ceased since 1900.

Kham showed a distinct pattern of diffusion centers compared to U-Tsang (). There were multiple diffusion centers of different scales in Kham, instead of U-Tsang’s single center. However, the diffusion distances outward from the centers in Kham were usually shorter than that of U-Tsang. The diffusions which were centered as Naitang Monastery and Galden Jampaling Monastery were the earliest in Qamdo. However, the diffusions were confined to Qamdo. The two diffusion centers (Labu Monastery and Saihang Monastery) in Yushu were also formed in the first hundred years. The Saihang Monastery-centered diffusion was the earliest identified in Kham. Nevertheless, it had limited influence for its small diffusion range. The Labu Monastery-centered diffusion continued in 500 years after its initial formation, with an obvious eastward directivity, showing a U-shaped curve. Graze possessed numerous Gelugpa monasteries, most of which were directly propagated from U-Tsang. Therefore, despite there were monastery clusters in Graze, the obvious diffusion center of monasteries was missing, such as the clusters in the north-east of Graze and the junction with Diqing during 1600–1700.

Among the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas, the spatial diffusion process of Amdo was the most complex, with the highest diffusion intensity (). In the first hundred years, a large number of Gelugpa monasteries were first introduced into Amdo from U-Tsang, mainly distributed near the eastern and southern Sino-Tibetan border. The Gelugpa monastery cluster in Ngawa is the largest during this period. Despite being the low period of Gelugpa, the second hundred years still witnessed Gelugpa monasteries’ gradual expansion from east to west. The secondary diffusions mainly happened in Hainan, Huangnan, and Gannan. During 1600–1700, Gelugpa monasteries further spread northwards to Haixi of Qinghai province, Haibei of Qinghai province, and Tianzhu of Gansu province, while the monasteries diffused at a low rate in the southern Ngawa. During 1700–1800, the diffusion was mainly in the juncture of three regions (Haidong, Hainan, and Huangnan), Gannan, and the southern part of Ngawa. During 1800–1900, the monasteries’ influence expanded in Haixi, Haibei, and Golog where Gelugpa used to be weak, while there was no diffusion in Huangnan where Gelugpa was historically prosperous. Additionally, most of the eastern diffusions were short-distance contagious, while the western part appeared mainly long-distance relocation diffusion. Since the 20th century, the Gelugpa monasteries have diffused westwards in general, mainly in Haibei, Hainan, and Huangnan, among which Hainan was the hottest zone.

Contrary to the relative independence of polycentric diffusion in Kham, Amdo possessed more influential diffusion centers, with different diffusion shapes and diffusion ranges crossing and overlapping each other (). Although Gelugpa spread into Amdo soon after its birth, the obvious diffusion centers were not formed until the 17th century. Amdo’s first diffusion tendency was Geerdi Monastery-centered diffusion system during 1500–1600. Geerdi Monastery was built near the frontier of Gannan and Ngawa in 1413 and was considered to be the largest and most influential Gelugpa monastery in Ngawa. Up to 1700, there were four diffusion centers of Gelugpa monasteries formally formed in Amdo. Taking Geerdi Monastery as the origin, the monastery diffusion system extended eastwards along the Bailong River. Based on the secondary diffusion node, Karong Monastery, the monastery diffusion system was broadened on both sides of the river. Over the same period, a mature Longwu Monastery-centered diffusion was formed rapidly in Huangnan, transmitting its influence all around, as far as Haidong and Hainan. Additionally, Youning Monastery-centered diffusion in Haidong and the diffusion system in Gannan were tending to form. However, the diffusion degree of them were still far smaller than Geerdi Monastery and Longwu Monastery. In 1700–1800, several Gelugpa monastery diffusions were further strengthened. Geerdi Monastery system continued its previous diffusion pattern, branching monasteries eastwards along the river, as far as the extreme south of Gannan. Besides, Longwu Monastery system and Youning Monastery system spread out further in contagious manner. In Gannan, while three diffusion centers started to emerge, Duoheer Monastery-centered diffusion was the strongest. As one of the six big Gelugpa monasteries, Labuleng Monastery was built in this period in Gannan, but its propagation was still limited at that time. In the following stage, centered on the several previous diffusion centers, the monastery diffusion systems were developed to different extents, especially the diffusion of Geerdi Monastery which had the widest scope and most obvious direction. Surprisingly, Youning Monastery-centered diffusion got stagnate. The diffusion systems of Labuleng Monastery and Taer Monastery reached a certain scale in the 19th century. Labuleng and Taer Monastery had distinct diffusion system, featured by much wider range and long-distance relocation diffusion. It appeared that Labuleng Monastery moved westwards on the expansion trend, while Taer Monastery had a tendency to move toward the south. Although Deqian Monastery was built as early as 17th century, it did not become a diffusion center until 1900, which may be limited by another neighboring famous monastery, Longwu Monastery, in Huangnan. When it came to the 20th century, as the diffusion speed of the Longwu Monastery system slowed down, there was an explosive increase in the northern Deqian Monastery system, which made Deqian Monastery another important diffusion center of Gelugpa in the whole Amdo. Meanwhile, almost all large diffusion system expanded westwards.

3.2. Discussions

3.2.1. Validation of multi-level diffusion model

To explore how effective the multi-level diffusion model may be for reconstructing the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries in Tibetan Inhabited Areas, an accuracy verification was conducted using traceable contagious diffusions. The accuracy of the multi-level diffusion model depends on step 3, unknown diffusion reconstructing, which is based on the principles of contagious diffusion. So, the short-distance diffusions were extracted as contagious ones from all accurately traceable diffusions and their consistencies with the simulation results were verified. The biggest feature of contagious diffusion is short-distance, which is difficult to define. In this study, an assumption is made that the diffusions which do not cross Tibetan Buddhist cultural areas are deemed to be the contagious diffusions of Gelugpa (the Three Tibetan Inhabited Regions can be further divided into 14 Tibetan Buddhist cultural areas). shows the number and ratio of diffusions with varying degrees of consistency in unknown diffusion reconstruction.

Table 1. The accuracy verification on unknown diffusion reconstruction.

The results of the validation suggest that among the 152 traceable contagious diffusions, 61 monastery diffusions are totally consistent with the model, which account for approximately 40.1% of all and 35.6% of the whole diffusions are homologous. Homologous diffusion means that there are discrepancies between the positions of validation data and simulated ones in the diffusion networks, but they have the same origin when tracing along the diffusion flows. Thus, homologous diffusions will be conducive to the clarification of the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries too, especially the exploration of diffusion centers. Inconsistent diffusions only occupy 24.3% of the total diffusions. Therefore, the relative accuracy of unknown diffusion reconstructing obtained by our method is about 75.7%. In this study, after taking the accurate diffusions with recorded origin into consideration (40.8% of all diffusions), the accuracy of multi-level diffusion model reaches up to 85.6%.

Despite the fact that the model appears to be highly effective in the study, there are some shortcomings. According to multi-level diffusion model’s performance in the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas, it can be found that the model is more adaptable in simple diffusion circumstances. As the diffusion centers and multi-level agents increase, the accuracies decrease. The validation results show that the model accuracy in single-center U-Tsang is much higher than that in multiple-centers Kham and Amdo. Furthermore, the model may be idealized to some extent. The diffusion mechanism of Gelugpa monasteries is much more complex far from location and time. The improvements on multi-level diffusion model require a deeper understanding on the diffusion mechanism of Gelugpa.

3.2.2. Diffusion mechanizations of Gelugpa monasteries

The diffusion mechanizations of Gelugpa monasteries in Tibetan areas of China can be deemed as a combination of natural and human driving factors. Natural factors dominate the basic diffusion patterns of Gelugpa monasteries. Topography determines that there are massive regional differences in the development of Gelugpa and the diffusion intensity of its monasteries. The harsh natural environment and living conditions of the northern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau lead to the shortage of Tibetans, the main believers of Gelugpa. As a result, the diffusion activities are distinctly rare in Qiangtang Plateau, Qinghai Plateau, and Qaidam Basin. Contrarily, the South-Tibet River Basin, Hehuang Valley, and Sichuan-Tibet Alpine Gorges in the southern and eastern part of Tibetan areas of China are more suitable for the spread of Gelugpa.

It seems that the diffusion regions of Gelugpa monasteries have a high degree of correlation with rivers. As the cradle of human culture, river valleys of high mountainous areas are warmer and humid, attracting humans to settle along the river banks. Rivers are the source of water for irrigation and promote the local economy through agricultural activities in valley zones. Developed agriculture provides the material basis for the local believers, who make offerings to the monasteries. In addition, rivers molded the diffusion shapes of Gelugpa monasteries in coverage and direction to some degree. Multiple parallel, independent, and small diffusion system of Gelugpa monasteries emerged in Kham due to the obstruction of Three Parallel Rivers Area. The diffusion coverage of Longwu Monastery and Youning Monastery were highly restricted by surrounding rivers. It was probably the relatively flat and simple rivers, the lack of natural obstruction that had deepened the complexity and crisscross of multi-centers Amdo’s diffusion system. Gelugpa monasteries also tended to be linear in spatial diffusion, coinciding with the directions of rivers in contagious manner. The representative example of that was the eastward Geerdi Monastery diffusion system along the Bailong River.

The diffusion intensity of Gelugpa monasteries is directly related to the local Tibetan population, the main believers of Gelugpa. Amdo had larger livable areas than U-Tsang and Kham. As a result, more Tibetans settled in Amdo, especially in the Hehuang Valley, building more towns and villages. Following the principles of hierarchical diffusion, after big cities’ acceptance in priority, Gelugpa monasteries were introduced to rural areas. In Tibetan areas of China, nearly every village needed its own monastery for local villagers to worship. Thus, Gelugpa monasteries were spread in more depth in Amdo. This explains why Amdo’s “diffusion chains” are much longer than that of U-Tsang and Kham. Also, this may be partly responsible for the lack of “Contagious Exacerbating” stage in U-Tsang and Kham.

The political forces and local authorities are the important influential factors in the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries. The Three Predicaments and breakthroughs of Gelugpa in its history were highly relevant to the struggles and cooperation of Tibetan local authorities and Mongolian forces. The struggles not only brought challenges but also opportunities to Gelugpa. The failure may hinder the influence expansion of Gelugpa through the establishment of monasteries, such as the obvious low ebb of diffusion speeds in 1500–1600. Besides, as the base area of Bka’-brgyud-pa and the supporting Pazhu regime, Lower Tsang was short of local diffusions historically, which may be caused by Bka’-brgyud-pa’s long resistance to Gelugpa. Conversely, victory in struggle may create a new pattern for the development of Gelugpa. For example, with the help of Mongolian forces, Gelugpa and the power behind it defended many local states in Tibet and forced the monasteries of other sects to convert to Gelugpa monasteries. Gelugpa overcame the limitations of other sects, not only extensively cooperating with local feudal lords in various regions but also winning the support of the feudal rulers of Mongolian, Han, and Manchu. Support from feudal rulers created an appropriate development environment for Gelugpa, while lords help clear away the local obstacles, such as other sects of Tibetan Buddhism.

The initial disseminations of Gelugpa monasteries had certain relations with the local Buddhism foundation. Whether the monasteries could develop into diffusion centers were not only determined by monastery strengths and demands but also depended on the comparative connections with surrounding monasteries. One of the most typical examples is Tashilhunpo Monastery in Lower Tsang. As the biggest Gelugpa monastery in Lower Tsang, Tashilhunpo Monastery did not show due diffusion ability worth its status, which may be restricted by the strong influence of monastery group in upper Tsang. Similarly, the two most famous Gelugpa monasteries in Amdo, Labuleng Monastery and Taer Monastery, did not develop the most outstanding diffusion systems, which might be attributed to the strong attraction of earlier nearby monasteries. Moreover, there existed an inverse relationship between Youning Monastery and Longwu Monastery in Huangnan, “as one fell, another rose”.

There is a key doctrine in Buddhism shared by all schools of Buddhism as “Yuanqi”, which is commonly translated as dependent origination. It states that all things (dharmas, phenomena, and principles) arise in dependence upon other things (Boisvert Citation1995). The spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries may be guided invisibly by the doctrine. The diffusion of Gelugpa monasteries relied highly on monks’ personal experience. A monastery can be built just because of their connections with a certain place or observed visions. Gelugpa site selection seemingly by chance, in fact, has its inevitability. It looks unreasonable to build a monastery in the cliffs or on a kilometer hilltop; however, the site choice may be needed for the purposes of escaping the fighting or practicing Buddhism. More hidden diffusion mechanizations of Gelugpa monasteries remain to be discovered through scientific quantitative methods.

3.2.3. Advantages and new thoughts

Unlike previous studies on the development of Gelugpa, which are mostly based on historical view and statistical methods, this paper not only aims to explore the diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries in geographical perspective but also conducts a quantitative research based on a geodatabase of geo-referenced Gelugpa monasteries and spatiotemporal analysis methods. The geo-referenced monastery data ensure scientific conclusions rather than the subjective ones, while spatiotemporal analysis methods can find potentially undiscovered knowledge of Gelugpa diffusions.

This paper also tries to make a thorough inquiry into detailed diffusion characteristics of Gelugpa monasteries, rather than only the general diffusion law. Superior to previous studies, which often treat spatiotemporal patterns as the equivalent of spatial diffusion, the study is carried out in four aspects of spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries, as diffusion bases, diffusion speeds, diffusion stages, and diffusion regions and centers. A multi-level diffusion model is established for the first time to reconstruct the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries with origin, multi-level agents, and diffusion flows. The validation shows that the model has a considerable applicability in the reconstruction of the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries. Furthermore, this paper initiates a diffusion stage model. The combination of diffusion stage model and multi-level diffusion model can realize the division of the diffusion stages in a quantitative manner.

The deficiency of source information is the biggest challenge in studying religion diffusion, which will greatly hinder the in-depth study on spatial diffusion processes. The reconstruction of diffusion networks is the key to this research. Despite there are some discrepancies inevitably among the agents and diffusion flows in simulated diffusion networks, as the diffusion mechanisms are clear and more influential factors are taken into consideration, the studies on the diffusion processes will eventually approach to the real history.

This paper hopes to contribute to the understanding of the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries through brand-new research ideas and models and provide reference to other researches on cultural diffusion, especially religion diffusion.

4. Conclusions

This study established a multi-level diffusion model to reconstruct the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries in the whole Tibetan areas. A diffusion stage model was designed to divide different diffusion stages of Gelugpa monasteries. Additionally, a novel research idea was proposed for exploring the detailed diffusion characteristics of Gelugpa monasteries throughout its processes. Finally, the diffusion mechanizations of Gelugpa monasteries were discussed. The study illustrated the following conclusions.

First, the multi-level diffusion model turns out to have a considerable applicability in the reconstruction of the diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries. The validation shows that the relative accuracy of unknown diffusion reconstructing part is about 75.7% and the accuracy of the whole model reaches up to 85.6%.

Second, the modified diffusion-stage model coincides with phased features of the expansion of Gelugpa monasteries. The diffusion stage model based on the simulated diffusion networks of Gelugpa monasteries can quantitatively differentiate multiple diffusion stages.

Third, the Gelugpa monasteries in the Three Tibetan Inhabited Areas present disparate spatial diffusion processes. As the birth land of Gelugpa, U-Tsang possesses the simplest diffusion pattern among the three, which has taken shape at its first 100 years. A superdiffusion center is formed in U-Tsang throughout the whole period. After 400-year ‘Initial Introduction stage, the diffusion of U-Tsang appears to be stalling. Kham experiences a slower and more varied spatial diffusion process, resulting in the formation of multiple relatively independent diffusion systems. Although the “diffusion chain” of Kham is slightly longer than U-Tsang, it also tends to be saturated. Amdo has the fastest diffusion speed and the most complex diffusion process, and it has maintained its vigor up till now. Amdo possesses more influential diffusion centers, with different shapes and ranges crossing and overlapping each other.

Finally, this study proposes that besides natural factors (topography and rivers), human factors, such as Tibetan population, Buddhism foundation, political forces and local authorities, may be responsible for the formation of the spatial diffusion processes.

Through the construction of a multi-level diffusion model and diffusion-stage model, this paper fills the blanks in the quantitative study on the detailed spatial diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries. Although there is still some room for improvements in the models, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of the spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries and provides reference to studies on religion diffusion. Future research should seek modified reconstruction means of monastery diffusion networks after fully considering the diffusion mechanizations of Gelugpa monasteries.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are involved in religious issues and are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zihao Chao

Zihao Chao is a PhD candidate in the School of Geography, South China Normal University. His research interests include spatial statistics, spatial-temporal analysis, and GIS, with a special interest in spatialized Tibetology.

Yaolong Zhao

Yaolong Zhao is a professor in the School of Geography, South China Normal University. His research interests include geographic information science and technology, spatially integrated humanities and social sciences.

Subin Fang

Subin Fang is a master’s student in the School of Geography, South China Normal University. Her research interest is spatial-temporal analysis.

Danying Chen

Danying Chen is a master’s student in the School of Geography, South China Normal University. Her research interest is spatial-temporal analysis.

References

- Beckmann, M. 1970. “Analysis of Spatial Diffusion Processes.” Papers, Regional Science Association 25: 109–117. doi:10.1111/j.1435-5597.1970.tb01480.x.

- Boisvert, M. 1995. The Five Aggregates: Understanding Theravada Psychology and Soteriology. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Brown, L.A. 1981. Innovation Diffusion: A New Perspective. New York, USA: Methuen & Co.

- Chao, Z., Y. Zhao, and G. Liu. 2021. “Multi-Scale Spatial Patterns of Gelugpa Monasteries of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibetan Inhabited Regions, China.” GeoJournal. doi:10.1007/s10708-021-10501-7.

- Chen, Q.Y., and S.F. Gao. 2003. A Complete History of Tibet. Zhengzhou: Zhengzhou Ancient Books Publishing House.

- Cliff, A.D., and J.K. Ord. 1975. “Space Time Modelling with an Application to Regional Forecasting.” Transaction of the Institute of British Geographers 64: 119–128. doi:10.2307/621469.

- Coldefy, M., and S.E. Curtis. 2010. “The Geography of Institutional Psychiatric Care in France 1800-2000: Historical Analysis of the Spatial Diffusion of Specialized Facilities for Institutional Care of Mental Illness.” Social Science & Medicine 71: 2117–2129. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.028.

- Dai, Y., and C. Du. 2012. “Khoshut Mongolian Troop and the Expansion of Gulu Monastery in Gansu and Qinghai in the Late Ming and Early Qing Dynasties.” Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Science) 49 (5): 58–64.

- Griffith, D., and B. Li. 2021. “Spatial-Temporal Modeling of Initial COVID-19 Diffusion: The Cases of the Chinese Mainland and Conterminous United States.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 24 (3): 340–362. doi:10.1080/10095020.2021.1937338.

- Hagerstrand, T. 1952. The Propagation of Innovation Waves. Lund: Royal University of Lund, Dept. of Geography.

- Hagerstrand, T. 1953. “Innovationsförlopp ur korologisk synpunkt”. PhD-Thesis. Lund University. Translated into English by Allan Pred in 1957: Innovation diffusion as a spatial process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hagerstrand, T. 1966. “Aspects of the Spatial Structure of Social, Communication and the Diffusion of Information.” Papers in Regional Science 16 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1007/BF01888934.

- Haining, R. 1983. “Spatial and Spatial-Temporal Interaction Models, and the Analysis of Patterns of Diffusion.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 8: 158–169. doi:10.2307/622109.

- Haynes, K.E., and A.S. Fotheringham. 1984. Gravity and Spatial Interaction Models. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Huang, M. 2010. Tubo Buddhism. Beijing: China Tibetology Publishing House.

- Huang, B. 2016. “Converting to Gelugpa Sect: The Evolution of the Politics-Religion Relationship of the Guge Kingdom in Ancient Tibet During the Yuan and Ming Dynasty.” Journal of Fujian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 196 (1): 104–113.

- Kendall, D.G. 1965. “Mathematical Models of the Spread of Infection”. In Mathematics and Computer Sciences in Biology and Medicine, edited by Medical Research Council, 213–225. London: Oldbourne Press.

- Lee, J., J. Lay, W.B. Chin, Y. Chi, and Y. Hsueh. 2014. “An Experiment to Model Spatial Diffusion Process with Nearest Neighbor Analysis and Regression Estimation.” International Journal of Applied Geospatial Research 5 (1): 1–15. doi:10.4018/ijagr.2014010101.

- Li, S. 2013. “Time and Space Distribution of Gelug Sect of Tibetan Buddhism Temples in Northern Tibetan-Yi Corridor and Its Features in the Qing Dynasty.” Journal of Northwest University (Social Sciences) 50 (4): 79–83. doi:CNKI:SUN:XBSD.0.2013-04-012.

- Morrill, R., G.L. Gaile, and G.I. Thrall. 1988. Spatial Diffusion. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Niu, T. 2016. “A Brief Analysis on the Distribution of the Gelug Sect Temples of Tibetan Buddhism.” Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture & Technology (Social Science Edition) 35 (6): 62–86. doi:10.15986/j.1008-7192.2016.06.012.

- Norpu. 2012. “On the Three Predicaments of the Gelugpa Sect in Its History.” Journal of Tibet University (Social Science Edition) 27 (1): 70–78. doi:10.16249/j.cnki.1005-5738.2012.01.015.

- Otterstrom, S.M. 2012. “International Spatial Diffusion of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.” Territory in Movement Journal of Geography and Planning 13: 102–130. doi:10.4000/tem.1630.

- Park, C.C. 1994. Sacred Worlds: An Introduction to Geography and Religion. London: Routledge.

- Pu, W. 2001. Buddhism History in Qinghai. Xining: Qinghai People’s Publishing House.

- Pu, W. 2013. The Series of Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries in China. Lanzhou: Gansu Ethnic Publishing House.

- Ryavec, K.E. 2015. A Historical Atlas of Tibet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ryavec, K.E., and M. Henderson. 2015. “Core-Periphery GIS Model of the Historical Growth and Spread of Islam in China.” Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 48 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1080/01615440.2014.996273.

- Tita, G., and J. Cohen. 2004. “Measuring Spatial Diffusion of Shots Fired Activity Across City Neighborhoods.” In Spatially Integrated Social Science, edited by M.F. Goodchild, D.G. Janelle, 171–204. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tobler, W.R. 1970. “A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region.” Economic Geography 46 (Supplement): 234–240. doi:10.2307/143141.

- Wang, K. 2009. “Study on the historical geography of Tibetan Buddhism in Kham Tibetan Area (8th century AD-1949).” Ph.D. diss., Jinan University.

- Wang, K. 2010. “Study on the Expansion of Gelug Sect’s Influence in Kham Tibetan Area in the 15th-18th Century: Take Monasteries as the Carrier.” China Tibetology 4: 38–45. doi:CNKI:SUN:CTRC.0.2010-04-008.

- Wang, S. 2010. A Brief History of Tibetan Buddhism. Beijing: Tibetology Publishing House.

- Wang, K. 2011. “Research on the Expansion of the Gelug Sect of Tibetan Buddhism in Kham and the Spatial Distribution of Its Temples in the Historical Period.” Historical Geography 1: 221–237.

- Xia-wu-li-jia. 2014. “Dissemination and Distribution Characteristics of Tsongkhapa’s Theory in Yushu.” Tibetan Plateau Forum 2 (2): 60–65.

- Yang, H. 2015. “The Spreading Activities of Gelug Sect in Ganzi in the Late Ming and Early Qing Dynasties.” Chinese Culture Forum 9: 110–113.

- Yang, J., M. Tsou, K. Janowicz, K.C. Clarke, and P. Jankowski. 2019. “Reshaping the Urban Hierarchy: Patterns of Information Diffusion on Social Media.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 22 (3): 149–165. doi:10.1080/10095020.2019.1641970.

- Zhao, H., J. Lee, X. Ye, and J. Tyner. 2017. “Spatiotemporal Analyses of Religious Establishments in Coastal China.” GeoJournal 82: 971–986. doi:10.1007/s10708-016-9726-y.

- Zhu, P. 2006. “The research of the historical-cultural geography of the Tibetan Buddhism in Qinghai.” Ph.D. diss., Shaanxi Normal University.