abstract

This article explores the intersecting vulnerabilities of non-national migrant mothers who sell sex in Johannesburg, South Africa – one of the most unequal cities in the world. Migrants who struggle to access the benefits of the city live and work in precarious peripheral spaces where they experience intersecting vulnerabilities associated with gender norms, race, and nationality. These vulnerabilities manifest as abuse, discrimination, criminalisation, and multiple levels of structural and direct violence. Migrant women who sell sex also face stigma and moralising associated with the illegal sale of sex, being foreign, and being a single parent. Drawing on ethnographic work with non-national migrant mothers who sell sex in Johannesburg, and from ongoing work exploring research, policy and programmatic responses to migration, sex work and health, we use an analytical lens of intersectionality to explore the daily challenges associated with encountering and negotiating intersecting vulnerabilities. We consider how these vulnerabilities form entanglements (drawing on Munoz, 2016) and are (re)produced and embodied in everyday practice in the city. We explore how they shift in significance and impact depending on context and social location, and argue for a nuanced approach to understanding migration and the sale of sex that recognises these intersecting vulnerabilities – and entanglements.

Background

“You know it is more difficult for us because we are not South African – the others they know the language and they can say ‘our brothers’ but we are not from here … one time the police came to me and a friend and they took us. They told us we must have sex with them then they let us go. I was scared as my child was small … I didn’t know what would happen.” (Heather, December 2013)

The sisters travelled to South Africa (SA) via Zambia as children, after fleeing the conflict in the DRC, and had been granted asylum on arrival. As children they were cared for as ‘unaccompanied minors’ by an international organisation in Johannesburg, and provided with accommodation and basic education. Once they turned 18 years of age, however, they were left to fend for themselves and, with a lack of legal support, became ‘undocumented’ (meaning they do not have the required documents to be in SA legally). In the excerpt above Heather describes her experiences in Johannesburg, focusing on the multiple, intersecting layers of stigma, violence and vulnerabilities that she faces as an undocumented black migrant woman, a single mother, and someone who sells sex.

In a country historically shaped by oppression, violence and racism, the intersections of race, class and gender as categories of identity are entrenched in SA (Groenmeyer, Citation2011). Despite over 20 years of formal democracy and policy change intended to support affirmative action approaches towards improving employment equity, the substantive rights of the majority of black women, including non-nationals, have not significantly improved; inequalities – and associated inequities – continue to grow in SA, and Johannesburg is now considered one of the most unequal cities in the world (Vearey, Citation2013). However, as Southern Africa’s economic hub, Johannesburg continues to attract migrants from both within and outside of SA’s borders in search of improved livelihood opportunities and better lives. While many move for economic reasons, a number (like Heather and her sister) are forced to flee their homes and thus arrive in SA as asylum seekers. Despite the many economic disparities, xenophobic violence and everyday struggles that cross-border migrants face in SA, the country continues to be seen as a place of safety and of hope.

Many non-national migrants, especially those who are undocumented, enter the informal and often unregulated sector and work as domestic workers, street vendors, and sex workers (Oliveira and Vearey, Citation2015; Vearey et al, Citation2011). Such migrants, including women like Heather and Christine, are part of an increasing population of ‘urban poor’: individuals who travel to cities like Johannesburg but struggle to access the benefits of the city and, as a result, find themselves living and working on the periphery – socially, economically and physically (for example, see Vearey et al, Citation2010; Vearey, Citation2013).

Although sex workFootnote1 is an important livelihood strategy (UNAIDS, Citation2012), it is currently criminalised in SA (Scheibe et al, Citation2016). This means that sex workers and those who sell sex – but do not identify as sex workers – face many forms of vulnerability, including gender-based, interpersonal, and behavioural violence: attacks by clients, abuse by the police or members of the public, etc. They also face structural violence in the form of police and client harassment and brutality, barriers to healthcare (including HIV testing and treatment) and problematic access to documentation and socio-legal services (Gould, Citation2011; Gould and Fick, Citation2008; Richter et al, Citation2014; Richter and Vearey, Citation2016; Scheibe et al, Citation2016; Vearey et al, Citation2011; Walker, Citation2016; Walker and Oliveira, Citation2015).

A clear relationship between migration trajectories and trajectories into sex work has been identified in the South African context (Richter and Vearey, Citation2016). The majority of migrant sex workers have been found to move in search of improved livelihood opportunities, and after migrating chose to sell sex as it is the most financially viable option available to them (Richter et al, Citation2014). While non-national migrant sex workers have been shown to experience some advantages compared to their non-migrant counterparts – including higher education levels and earning more money per client – they also report facing high levels of risk and violence, in particular abuse and brutality from the police, challenges in accessing healthcare, and less frequent condom use (Richter et al, Citation2014). Thus the criminalisation of sex work intersects with the stigmatisation of and discrimination against those who are seen to ‘not belong’ (Oliveira, Citation2016; Oliveira and Vearey, Citation2015; Walker, Citation2016).

Heather and Christine together with eight other non-national migrant women participated in a collaborative research project in Johannesburg led by the authors. Heather was 24 at the time of the interview quoted from earlier, and was staying with her young son in a friend’s rented flat in central Johannesburg. Heather had started selling sex at 18 after being introduced by family to working in a club where sex workers operated. She now sells sex on a regular basis, but does not identify as a sex worker. Her sister Christine started selling sex at the age of 20. Like Heather she does not identify as a sex worker. In fact, all of the participants in our research project were non-national, undocumented migrant women who sold sex but did not use or identify with the term ‘sex worker’. Instead they referred to the selling of sex as a temporary strategy – even when they had been selling sex for many years – to make ends meet and provide for their children. For many/all, the sale of sex was a supplementary livelihood strategy to other informal work, including selling clothes, washing dishes in restaurants and domestic work.

Doubly vulnerable?

Our research project aimed to explore the ‘double vulnerabilities’ – of being a non-national, and of working in a criminalised industry – faced by migrant sex workers and migrant women who sell sex in Johannesburg. In this article we draw from our findings to describe the multiple realities of living and selling sex in the complex urban context of Johannesburg, and the ways in which migrant mothers who sell sex interact with social, economic and physical peripheries. To do this we begin by describing our research project and the methodologies used.

Drawing on the experiences of two participants, sisters Heather and Christine, we highlight the multiple, intersecting vulnerabilities (of which being a non-national and working in a criminalised industry are only two), and the ways in which these vulnerabilities are entangled (Munoz, Citation2016), (re)produced, (re)made, and (re)signified in urban spaces of the city. The notion of entanglements (see: Nuttall, Citation2009; Munoz, Citation2016; Kerfoot and Hyltenstam, Citation2017), we argue, allows for a description of how the axes of difference in identity and experience cut across and shape one another, are subjectively lived out in peripheral everyday lives and (re)produced through the convergence of different identities and experiences (Yuval-Davis, Citation2006:198). We draw on Munoz’s (Citation2016:304) definition of entanglements as:

… the temporal attachments that bring nonhuman, material, and nonmaterial together as part of each other’s worlds, while meshing, combining, changing, and often uncovering other ways of knowing and being.

Methodology

The research that we highlight in this article is drawn from a larger project that aimed to explore the ‘double vulnerability’ of women as (1) non-nationals, and (2) women who sell sex through a discourse analysis of multi-level policies surrounding migration, sex work, public health, and trafficking, and semi-structured interviews to explore the lived experiences of migrant women who sell sex. Here we focus on the fieldwork undertaken in Johannesburg by the first author, and reflect on the findings from the wider study, which provide a picture of the entangled vulnerabilities faced by migrant women who sell sex in the city.

As part of this research we engaged with women in the inner city who sold sex but who had not been part of any other sex work-related research in Johannesburg, and/or were not connected to the local sex worker movement. This also meant that they had not been exposed to the politicisation of sex work – which includes advocacy work and a focus on law reform. Through focusing on women who were unconnected in this way we sought better to understand the less visible and less documented experiences of women who sell sex in the city but do not self-identify as sex workers, and in particular to understand why some cross-border migrant women do not identify with the term ‘sex worker’.

A snowballing method was used. As the lead author (RW) had met Heather through previous voluntary work in Johannesburg and Heather had disclosed to her that she sold sex, Heather became the primary contact. She then connected the lead author with her sister and her friend, who then suggested further possible participants to contact. In this way a group of 8 women, all non-national migrants who had arrived in Johannesburg between 2000 and 2013, and all mothers who sold sex, was established.

Initially participants were fearful of talking and sharing personal information, and the building of trust was a slow and difficult process. That said, the advantage of working with a relatively small group through an ethnographic approach that allowed for long-term engagement meant that relationships could be developed and, crucially, over time trust could be gained. Moreover, a small sample meant that sensitive and often difficult issues could be explored in depth with the participants and ethical issues could be carefully considered and negotiated.

The women who participated in this study were over the age of 18 years and all cared for their children alone in Johannesburg. At the time of the study all of the women were undocumented; most had obtained asylum seeker permits soon after their arrival in SA, but these had since expired. With many it was unclear why they had been unable to extend their permits – but it appeared that lack of information, not knowing who to talk to, and fears of approaching Home Affairs meant that they had allowed their permits to lapse. This meant that all of the women had learnt to navigate, on a daily basis, the “hidden spaces” (Vearey, Citation2010) of the city – spaces that highlight the complexities and often marginalisation of the urban environment, where we find migrant populations who are “physically, socially, politically and in some ways economically, hidden from the functioning of the (formal) city” (Vearey, Citation2010:40). These are spaces that pose both opportunity and risk – and, significantly, offer insight into how the (lack of) documentation and thus residing in SA illegally can compound the risks that non-nationals face, particularly if they also sell sex for a living (Oliveira and Vearey, Citation2015; Vearey, Citation2013).

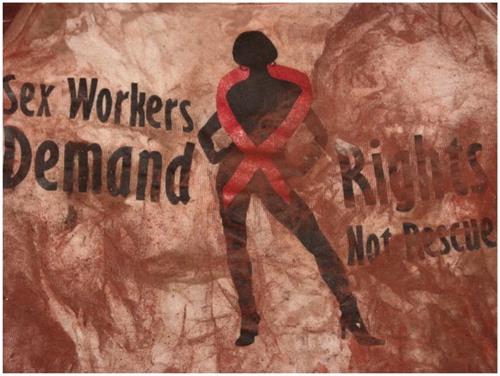

Photograph by Confidence.Footnote5 © 2010 MoVE Collective

Such risks are in turn shaped and heightened by the responsibilities and challenges of caring for young children as single parents, especially in a context where mothers who sell sex face particular kinds of stigma and moralising which labels them as “bad mothers” (Dodsworth, Citation2014:100). However, as reflected in studies with sex workers and women who sell sex globally, many women sell sex in order to support their families (Basu and Dutta, Citation2011; Dodsworth, Citation2014; Nencel, Citation2001). Research from SA also indicates that migrant sex workers are responsible for more dependants, with internal migrants supporting three dependants, and cross-border migrants supporting four dependants – compared to non-migrants, who had a median of two dependants (Richter et al, Citation2014).

Given the criminalisation of sex work and the importance of anonymity, the women were given the option to use pseudonyms and to opt out of the research at any time. Interviews were conducted in a neutral space away from the participant’s home and work areas. Each participant was compensated for their time and any potential loss of earnings with a food voucher or airtime. Since all of the women were proficient in English, and due to the sensitivity of our conversations, translators were not used. The interviews were also not recorded; it was clear from the first few interviews that the women felt uncomfortable speaking with a recorder on, and therefore notes were taken. Interviews were loosely structured, with basic questions directed at exploring how the women came to be living in Johannesburg, what forms of work (including selling sex) they had been/were involved in, and the kinds of challenges that they faced, for example with regard to accessing healthcare and supporting their children. Interviews were then transcribed and the transcripts were read a number of times to identify prominent themes and categories using thematic analysis. This enabled us to explore the complexities of the intersectional issues discussed, specifically experiences of motherhood, of being a migrant and of selling sex.

Ethical clearance for this research was provided by the University of the Witwatersrand (certificate no. H140212), and guidance on ethical issues drawn from a body of research carried out with sex workers and migrants in Johannesburg at the African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS), where the first two authors are based.

The nature of this kind of research, with women living in marginal and precarious contexts, often with immediate material needs and sometimes in times of crisis (facing eviction, arrests, urgent healthcare needs including antiretroviral medication (ARVs) and termination of pregnancy) meant that many complex and context-specific ethical issues were encountered. These brought to the fore notions of positions of privilege, race, class, and power. Thus the research process itself was shaped by intersecting issues which reflected both the specific context of life in Johannesburg, where there is little structural support available to women in extremely marginal situations (Kihato, Citation2013; Walker and Clacherty, Citation2015), and where research is produced by researcher and participant in relative and shifting positions of power and powerlessness.

Findings and discussion

While the framework of ‘double vulnerabilities’ set the focus of our research and directed our exploration in terms of understanding the intersection of migration and selling sex, what clearly emerged during the research process was that the vulnerabilities faced were multiple, and could change, heighten, and intensify, depending on each individual and each situation.

While some of these experiences could be captured through exploring migration and the sale of sex, it was evident that many of the more nuanced and implicit experiences of everyday life in the city were not always visible or narrated by participants in obvious ways. Moreover, the boundaries of what was deemed as risky and precarious could shift and change shape regularly – and in a way that could not always be captured and understood through the research lens of ‘double vulnerabilities’. Yuval-Davis (2006:199) frames this as the need to recognise the “different kinds of difference” that fragment and complicate the ‘additive’ process of intersectionality. This ensures that an intersectional analysis moves beyond the experiential level in which positions, identities and values are conflated (Yuval-Davis, Citation2006).

This was reflected, for example, through rejection of the term ‘sex worker’ by the participants in our research. The decision not to identify with the label revealed the complex realities of those involved in the sale of sex, that could not be fixed or flattened to a homogenous term or label. Similarly, the emphasis placed by participants on the challenges of being single, mostly never-married, migrant mothers who sold sex, revealed a perspective that has not been accessed through work with migrant/transnational families and especially through the burgeoning focus on ‘migrant mothers’ and experiences of mothering/care-giving from a distance. These significant issues in our research reflected the lens of ‘double vulnerabilities’ yet also challenged it to expand and fragment, to consider other, intersecting and entangled (Munoz, Citation2016) forms of identity – such as motherhood – which are not always accessible or obvious.

Photograph by Modise.Footnote6 © 2010 MoVE Collective

Through the experiences of Heather and Christine that are shared below, we focus on the intersections of being a migrant, a mother and selling sex, and show how each of these shifting categories or identities shapes everyday experiences, and can come into focus or fade out depending on the particular context. Moreover, the vulnerabilities encountered are produced not only by the intersection of identities but also the entanglement of laws, policies and practices by the State, which maintains and heightens them.

Heather and Christine both started to sell sex after failing to secure other forms of employment and/or being exploited in the workplace. For example, Christine had found a job as a waitress, which refused to pay her at the end of the month because she was undocumented. Heather also highlighted this as a pattern: of finding employment, being exploited or arrested, and then losing her position. She noted that for a number of months she had worked in a bar and also at another time had looked after a friend’s child for a small wage. However, during both periods of employment she had encountered abuse by the police for not having the correct documents, had not been paid or had been arrested. In the end she and her sister were introduced by a family member to work in a club, from where she started to find clients and selling sex became a viable option for her. As Heather recounts:

“I had the job to clean the house, then I got arrested as I didn’t have papers … I couldn’t go back to Congo as no family there, so I said I was Zambian. I just wanted to die. My parents died, I had no job – they kept arresting me … I didn’t care for myself … [T]hen my auntie told me to stop asking for money and to earn my own. She showed us [her and Christine] the club and I picked up a man and it started from there. Sister did the same thing – but she got HIV. I got pregnant.” (Heather, April 2014)

Health in the city

The quote above, where Heather notes that her sister became infected with HIV through the selling of sex, while she became pregnant, reflects the everyday realities of risk that women who sell sex face.Footnote3 Such realities become more precarious in a context of criminalisation, as in SA and elsewhere, where people who sell sex face abuse and unethical treatment in the healthcare system and/or are fearful of accessing healthcare due to previous negative experiences (Pauw and Brener, Citation2003; Richter et al, Citation2014; Stadler and Delany, Citation2006).

In bringing together the experiences of migrants and women who sell sex, forms of abuse and maltreatment are heightened (Richter and Vearey, Citation2016). Research has also shown that non-nationals are overwhelmingly the recipients of maltreatment and struggle with access, over-charging and abuse when seeking treatment in the South African healthcare system (Vearey, Citation2014). Thus for non-national women who sell sex many difficulties can be faced when attempting to access treatment. For example, Heather went on to describe that when she found out she was pregnant she was unable to get a termination through the public healthcare system, as she was informed that in the long line of those waiting, “foreigners come last” (Heather, April 2014). In being asked whether she was aware that Johannesburg had a clinic specifically for sex workers,Footnote4 Heather had responded that she was not a sex worker, and said that she would never reveal that in a clinic she sold sex.

This point highlights the need for sex worker interventions to consider the nuances within the industry, including the fact that not all of those who sell sex identify as sex workers and thus do not access the programmes designed to support them. Subsequently Heather had to find money to seek an abortion through one of the many illegal abortion clinics that operate in Johannesburg: “[A]t six months I had an abortion. I had to give R400 and a phone. The baby was big when it came out” (Heather, April 2014).

Christine’s experience of acquiring HIV and trying to access treatment is also significant here, and again highlights the layers of vulnerabilities faced as an undocumented migrant, a mother (her daughter is also HIV positive) and an individual who sells sex. Christine had previously been on treatment but then had gone back to Zambia for a period of time and been unable to continue with her medication. She reported being denied access to ARVs for both herself and her daughter at three different clinics, despite the fact that according to law ARV treatment is free to all who reside in SA, regardless of documentation (Vearey, Citation2012). When she was eventually able to get tested, receive counselling and be put on treatment, Christine reported facing negative attitudes from doctors and nurses, which she felt reflected their perception of non-nationals as well as what they saw as her own negligence in her and her daughter not being on treatment.

While risks taken during the sale of sex had probably led to Christine’s acquisition of HIV, in seeking treatment it was her identity as a non-national and possibly as a mother that caused further vulnerabilities. Thus an intersectional lens here reveals both the multiple identities which expose different forms of discrimination, and the policies and practices that maintained and further entrenched these vulnerabilities. As Crenshaw (Citation1993:3) notes in relation to the experiences of battered women of colour, interventionist strategies cannot be successful unless they are responsive to the intersections of vulnerability that exist. It can similarly be argued that interventions that focus solely on sex workers’ risk overlook the marginalised experiences of individuals who sell sex but do not identify as sex workers, or of undocumented migrants who sell sex, or of mothers who sell sex – all of whom at any one time can experience shifting and entangled identities which construct their social worlds. As such “these interventions are likely to reproduce rather than effectively challenge their [the women’s] domination” (Crenshaw, Citation1993:4).

Photograph by PinkyFootnote7. © 2010 MoVE Collective

Policing the city

Heather and Christine also described many encounters with the police where they would be arrested for selling sex and/or for being undocumented. Christine described one such experience where she was waiting outside a club looking for clients, having left her baby at home with a friend. She noted that she had previously been identified by the police for selling sex, and so was taking a risk waiting outside the club:

“They took my picture before so then they come [the police] and arrest me and they take me to Sun Hill [police station]. I was crying and pleading with them to let me go. I told them I have a small baby at home and the babysitter cannot stay. So they say ‘You must not do this when you have a child’. They asked me ‘What kind of mother are you? This is not what good mothers do’. Then they let me go.” (Christine, April 2014)

Where police harassment and the threat of arrest are ever-present realities in the lives of individuals who sell sex in SA (Scorgie et al, Citation2012:1), this experience highlights the intersections of vulnerability. For example, Christine was arrested for looking for clients and possibly as being a non-national, but then the questioning by the police refers to her identity as a mother and passes judgement about being a mother who sells sex. The question ‘What kind of mother are you?’ and the comment ‘[T]his is not what good mothers do’ reflects common perceptions that women who sell sex, and particularly migrant women, are violating normative ideas of women’s role in the home and their so-called ‘purity’ by destroying family structures and sexual norms (Basu and Dutta, Citation2011; Duff et al, Citation2015; Palmary, Citation2010:51). Moreover it relates directly to beliefs that women who sell sex cannot be ‘good mothers’ and instead are labelled as ‘bad mothers’ (Dodsworth, Citation2014:100).

Mothering in the city

This labelling of ‘bad mothers’ came up frequently in the interviews with participants. Heather in particular noted how she was stigmatised by her own family not only because she sold sex but because she was unmarried:

“For me, being a mother should be about marriage. Without that, people say bad things. But then you see, my sister she has the sickness. She also does this [sell sex], but because she is married she is OK”. (Heather, October 2015)

While Heather recognises her own reasons for selling sex and explains the need to make her specific situation work for her, she is clearly affected by the stigma and moralising from her own family. In particular, she places her status and identity as an unmarried woman at the centre of this, suggesting that her family perceive this as worse than selling sex, or than living with HIV like her sister. It also shows how Heather grapples with her own identity as she works through the reasoning and rationale for why she sells sex. This is shown quite clearly where Heather points out her family’s use of the term “prostitute” – a term that she doesn’t reject and even uses herself – but equally it is clear that for her this label is shaped by her awareness of why she sells sex. In noting “I am bad”, Heather reveals internalisation of the moralisation and stigma directed at women who sell sex, and that despite the fact that she recognises the need to earn money and that selling sex works for her, she still judges herself according to others, and particularly her family.

What was revealing was that in discussing further the issue of marriage, Heather noted “I wouldn’t want more kids unless I was married – I feel like in marriage we are two – not that alone feeling … the heaviness” (October 2015). This suggests that beyond the stigmatisation of single mothers, Heather also wants support and someone to share the responsibilities and challenges of parenting with. This sense of being alone and without support – when combined with the entangled vulnerabilities faced in being an undocumented migrant and selling sex – powerfully builds a picture of the entangled social realities that frame everyday life for Heather and women like her.

Conclusion

“It’s not what I enjoy. I just want the money. Survival. You just want to do it and for it to be over. Sometimes they ask, put your mouth here and you want to vomit but you keep going because it’s money. You need to pay crèche … you need to buy food … The clients – I like the white ones – they say they like the other girls … not South African. They like the slim body. So then I can get the money, but if I get some other job I can stop.” (Heather, November 2016)

Despite a growing body of research that explores the experiences of migrants engaged in the sex industry, much has been (and remains) framed through a public health lens that often – even if unintentionally – frames sex workers and individuals who sell sex as a ‘key population’ requiring special consideration in HIV and health programming (for example, see Richter and Vearey, Citation2016; Scheibe et al, Citation2016). Moreover, where an interest in the experiences of migrant sex workers does exist, much work has focused on their position within the (informal) economy, thus emphasising their role as labour migrants rather than, for example, looking at what it means to be a migrant ‘other’ and the risks that this engenders (Agustín, Citation2007; Walker and Hüncke, Citation2017; Walker and Oliveira, Citation2015).

While we would not dispute the need for targeted interventions to address the health and labour rights of migrants who sell sex, there is an urgent need to develop a more nuanced understanding of their lived experiences within complex urban spaces such as Johannesburg (Oliveira, Citation2016; Oliveira and Vearey, Citation2015; Walker, Citation2016). Such an approach should recognise not only the ways in which urban space shapes everyday experiences and vulnerabilities, but also that these spaces are shaped by those living, working and moving through them (Oliveira and Vearey, Citation2015; Shah, Citation2014). Thus the drawing together of intersectional analysis with the idea of entanglements enables a deeper recognition of the many complex layers of identities, categories and experiences which form a part of everyday life in the city.

Heather and Christine’s experiences highlight the ways in which the intersections of being a non-national migrant, a woman who sells sex, a mother, and a single parent lead to complex lived experiences in which the various vulnerabilities encountered can play into and heighten one another. The final quote by Heather illustrates the entangled threads of choice and lack of choice, of survival and agency, and of how race, gender, desire, disgust, ambition and despair can simultaneously shape everyday experiences. Where negotiation and opportunity can be located in these threads, it is struggle for survival and needing to make ends meet that dominate such lived experiences.

In recognising the historical, social and political contexts which weave through and shape every experience and encounter in SA, we have drawn on the more specific nuanced experiences of undocumented migrant mothers who sell sex in Johannesburg to consider how the combination and often fragmentation of identities leads to heightened forms of intersecting and entangled vulnerabilities described throughout this article. The experiences of Heather and Christine outline the struggles they face due to working in a criminalised context, being without legal documents, and experiencing police and client abuse; challenges in accessing healthcare, including treatment for HIV and safe termination of pregnancy; and the underlying social pressure to be a ‘good mother’ and a married woman with an involved husband and father. These struggles, as McCann and Seung-Kyung (Citation2003) note, underscore the conflicting and complex aspects of identity in women’s lives, which shift with different experiences, creating an opportunity for negotiation between each of the categories of identity.

However, as we have illustrated through the stories of Heather and Christine, these negotiations often take place in peripheral and extremely marginalised social contexts where few options exist and where vulnerabilities are heightened through the entanglement of identities and experience. Even so, migrant mothers like Heather and Christine who sell sex find ways of how to work through and around these vulnerabilities, drawing on their entangled identities and negotiating experiences to ensure that they can provide for themselves and their children.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their invaluable contribution to the research, especially Heather and Christine for being willing to share their stories with us. The research was funded by the NWO-WOTRO Science for Global Development Migration, Development and Conflict programme, grant number W.07.04.102, and the project included fieldwork in SA and The Netherlands. JV and RW are also currently supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rebecca Walker

REBECCA (BECKY) WALKER is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand, where she is involved in a number of research projects based around migration, sex work and health, and also the teaching and supervision of graduate students. As a social anthropologist her interests lie in ethnographic work and visual methods to explore the everyday experiences of migrant mothers who sell sex in Johannesburg. More broadly she has looked at the impact of structural and everyday violence on the lives of women, and in turn how women negotiate and challenge vulnerabilities encountered, including access to healthcare and education. Becky has published widely, including articles and chapters on everyday violence, sex work, trafficking and the intersections of migration, sex work and motherhood. Email: [email protected]

Jo Vearey

JO VEAREY is an Associate Professor at the African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand, where she is involved in designing and coordinating research programmes, teaching, and supervising graduate students. Jo is a South African National Research Foundation-rated researcher and has established the Migration and Health Project Southern Africa (maHp) through a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award. With a commitment to social justice, Jo’s research explores ways to generate and communicate knowledge to improve responses to migration, health and wellbeing in the southern African region. Email: [email protected]

Lorraine Nencel

LORRAINE NENCEL is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She has specialised in qualitative methodology and her research focuses primarily on gender and sexuality. She is currently a co-investigator on a project concerning the sexual and reproductive health of young female migrants (sex workers, readymade garment workers, and beauty parlour workers) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Lorraine also writes on epistemological issues and researchers’ engagement in relation to feminist and critical research. She has undertaken research on sex work in Peru, South Africa, The Netherlands, Ethiopia and Kenya. The projects in Bangladesh, Kenya and Ethiopia are collaborative projects working directly with sex worker organisations and other local stakeholders. Lorraine is a member of the Dutch activist-sex worker-research network SexWork Expertise, and a member of the EU COST ACTION: ProsPol, a European network of researchers working on issues regarding sex work and prostitution policy. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 We use ‘sex work’ or ‘selling sex’ to refer to the “exchange of sexual services, performances, or products for material compensation” (Weitzer, Citation2010:1). We do not include individuals under the age of 18 years within this definition, nor do we refer to victims of trafficking. In acknowledging that the label of ‘sex worker’ carries with it a specific political, global currency that does not necessarily reflect the experiences of all who are involved in the selling of sex, throughout this article we refer to ‘women who sell sex’ (see Walker and Oliveira, Citation2015:143–147).

2 An exploration of the broad context of debate and critique that surround the historical and contemporary understandings of intersectionality as a theory, methodology and platform for social justice is beyond the scope of this article. However, we do not underestimate the significance of engaging with the shifts and contentions embodied within the use of this theory and form of analysis – especially given its centrality to understanding the specific, and intersecting experiences of particular groups of women in their complexities and at the point at which various and multiple vulnerabilities converge (Yuval-Davis, Citation2006). It is from this position that we take our understanding of intersectionality (cf. Groenmeyer, Citation2011; Yuval-Davis, Citation2006; McCann and Kim, Citation2003).

3 Where a range of social determinants influence the health and wellbeing of individuals who sell sex, many health inequities are experienced, including reproductive health and rights, mental health, chronic illness, and a disproportionate risk of HIV infection and other sexually transmitted infections (Scheibe et al, Citation2016).

4 Wits Reproductive Health Institute runs a clinic in Hillbrow, Johannesburg that is specifically for sex workers.

5 The name ‘Confidence’ is a pseudonym given to one of the research participants of Working The City, a visual methods project with sex workers that was run at ACMS under the MoVE Collective.

6 The name ‘Modise’ is a pseudonym given to one of the research participants of Working The City, a visual methods project with sex workers that was run at ACMS under the MoVE Collective.

7 The name ‘Pinky’ is a pseudonym given to one of the research participants of Working The City, a visual methods project with sex workers that was run at ACMS under the MoVE Collective.

References

- Agustín LM (2007) Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry, London: Zed Books.

- Basu A and Dutta MJ (2011) ‘”We are mothers first”: Localocentric articulation of sex worker identity as a key in HIV/AIDS communication’, in Women Health, 51, 106–123. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2010.550992

- Crenshaw K (1993) ‘Beyond racism and misogyny’, in M Matsuda, C Lawrence and K Crenshaw (eds) Words That Wound, Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

- Dodsworth J (2014) ‘Sex worker and mother: Managing dual and threatened identities’, in Child and Family Social Work, 19, 99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00889.x

- Duff P, Shoveller J, Chettiar J, Feng C, Nicoletti R and Shannon K (2015) ‘Sex Work and motherhood: social and structural barriers to health and social services for pregnant and parenting street and off-street sex workers’, in Health Care Women International, 36, 1039–1055. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.989437

- Gould C (2011) ‘Trafficking? Exploring the relevance of the notion of human trafficking to describe the lived experience of sex workers in Cape Town, South Africa’, in Crime Law and Social Change, 56, 529–546. doi: 10.1007/s10611-011-9332-3

- Gould C and Fick N (2008) Selling sex in Cape Town: Sex work and human trafficking in a South African city, Cape Town: Institute for Security Studies.

- Groenmeyer S (2011) ‘Intersectionality in Apartheid and Post Apartheid South Africa. Unpacking the narratives of two working women’, in Gender, Technology and Development, 15, 249–274. doi: 10.1177/097185241101500204

- Hulko W (2009) ‘The time- and context-contingent nature of intersectionality and interlocking oppressions’, in Affilia – Journal of Women and Social Work, 24, 44–55. doi: 10.1177/0886109908326814

- Kerfoot C and K Hyltenstam (eds) (2017) Entangled discourses: South-North Orders of Visibility. Routledge Critical Studies in Multilingualism, New York: Routledge.

- Kihato C (2013) Migrant Women of Johannesburg: Life in an in-between city, Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- McCann C and Seung-Kyung K (eds) (2003) Theorizing intersecting identities: Feminist local and global theory perspectives reader, New York: Routledge.

- Munoz L (2016) ‘Entangled sidewalks: Queer street vendors in Los Angeles’, Professional Geographer, 68, 302–308. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2015.1069126

- Nencel L (2001) Ethnography and Prostitution in Peru, London: Pluto Press.

- Nuttal S (2009) Entaglement: Literary and Cultural Reflections on Post Apartheid, Johannesburg: Wits University Press

- Oliveira E (2016) ‘“I am more than just a sex worker but you have to also know that I sell sex and its okay": Lived experiences of migrant sex workers in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa’, in Urban Forum, 28, 1–15.

- Oliveira E and Vearey J (2015) ‘Images of place: Visuals from migrant women sex workers in South Africa’, in Medical Anthropology, volume 34, 305–318. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2015.1036263

- Palmary I (2010) ‘Sex, choice and exploitation: reflections on anti-trafficking discourse' in E Burman, K Chantle, P Kiguwa and I Palmary (eds) Gender and Migration: Feminist Interventions, London: Zed Books.

- Pauw I and Brener L (2003) ‘“You are just whores - you can't be raped": Barriers to safer sex practices among women street sex workers in Cape Town’, in Culture, Health and Sex, 5, 465–481. doi: 10.1080/136910501185198

- Richter M, Chersich MF, Vearey J, Sartorius B, Temmerman M and Luchters S (2014) ‘Migration status, work conditions and health utilization of female sex workers in three South African cities’, in Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 16, 7–17. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9758-4

- Richter M and Vearey J (2016) ‘Migration and sex work in South Africa: Key concerns for gender and health’, in J Gideon (ed) Gender and Health Handbook, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Scheibe A, Richter M and Vearey J (2016) ‘Sex work and South Africa’s health system: Addressing the needs of the underserved’, in South African Health Review, 165–178.

- Scorgie F, Chersich MF, Ntaganira I, Gerbase A, Lule F and Lo Y-R (2012) ‘Socio-demographic characteristics and behavioral risk factors of female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review’, in AIDS and Behaviour, 16, 920–933. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9985-z

- Shah S (2014) Street Corner Secrets: Sex, Work, and Migration in the City of Mumbai, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stadler J and Delany S (2006) ‘The “healthy brothel”: The context of clinical services for sex workers in Hillbrow, South Africa’, in Culture, Health and Sex, 8, 451–464. doi: 10.1080/13691050600872107

- UNAIDS (2012) UNAIDS guidance note on HIV and sex work, Geneva: UNAIDS.

- Vearey J (2010) ‘Hidden spaces and urban health: Exploring the tactics of rural migrants navigating the City of Gold’, in Urban Forum, 21, 37–53. doi: 10.1007/s12132-010-9079-4

- Vearey J (2012) ‘Learning from HIV: Exploring migration and health in South Africa’, in Global Public Health, 7, 58–70. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.549494

- Vearey J (2013) ‘Migration, urban health and inequality in Johannesburg’, in Migration and Inequality, London: Routledge.

- Vearey J (2014) ‘Healthy migration: A public health and development imperative for south(ern) Africa’, in South African Medical Journal, 104, 663. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.8569

- Vearey J, Palmary I, Nunez L and Drime S (2010) ‘Urban health in Johannesburg: the importance of place in understanding intra-urban inequalities in a context of migration and HIV’, in Health Place, 16, 694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.02.007

- Vearey J, Richter M, Núñez L and Moyo K (2011) ‘South African HIV/AIDS programming overlooks migration, urban livelihoods, and informal workplaces’, in African Journal of AIDS Research, 10, 381–391. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2011.637741

- Walker R (2016) ‘Selling Sex, mothering and “keeping well” in the city: reflecting on the everyday experiences of cross-border migrant women who sell sex in Johannesburg’, Urban Forum, 28, 1, 1–15.

- Walker R and Clacherty G (2015) ‘Shaping new spaces: An alternative approach to healing in current shelter interventions for vulnerable women in Johannesburg’, in I Palmary, B Hamber and L Núñez (eds), Healing and Change in the City of Gold, Peace Psychology Book Series, New York: Springer International Publishing, 31–58.

- Walker R and Huncke A (2017) ‘Sex work, human trafficking and complex realities in South Africa’ in Trafficking, Smuggling and Human Labour in Southern Africa (Special Issue) Edited by Walker, R, Camden, B and T Galvin. Vol. 2 (2): 127–140.

- Walker R and Oliveira E (2015) ‘Contested spaces: Exploring the intersections of migration, sex work and trafficking in South Africa’, in Graduate Journal of Social Science, 11, 129–153.

- Weitzer R (2010) ‘The movement to criminalize sex work in the United States’, in Journal of the Law Society, 37, 61–84. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6478.2010.00495.x

- Yuval-Davis N (2006) ‘Intersectionality and feminist politics’, in European Journal of Womens Studies, 13, 193–209. doi: 10.1177/1350506806065752