abstract

Building on the work of Mbembe (2019) and Silva (2007), we theorise how the obstetric institution can still be considered fundamentally modern, that is, entangled with colonialism, slavery, bio- and necropolitics and patriarchal subjectivity. We argue that the modern obstetric subject (doctor or midwife) representing the obstetric institution engulfs the (m)other in a typically modern way as othered, racialised, affectable and outer-determined, in order to constitute itself in terms of self-determination and universal reason.

While Davis-Floyd (1987) described obstetric training as a rite of passage into a technocratic model of childbirth, we argue that students’ rite of passage is not merely an initiation into a technological model of childbirth. The many instances of obstetric violence and racism in their training make a more fundamental problem visible, namely that students come of age within obstetrics through the violent appropriation of the (m)other.

We amplify students’ curricular encounters in two colonially related geopolitical spaces, South Africa and the Netherlands, and in two professions, obstetric medicine and midwifery, to highlight global systemic tendencies that push students to cross ethical, social and political boundaries towards the (m)other they are trained to care for. The embedment of obstetric violence in their rite of passage ensures the reproduction of the modern obstetric subject, the racialised (m)other, and institutionalised violence worldwide.

“Women who perceived that they had experienced traumatic births viewed the site of their labour and delivery as a battlefield. While engaged in battle, their protective layers were stripped away, leaving them exposed to the onslaught of birth trauma. Stripped from these women were their individuality, dignity, control, communication, caring, trust, and support and reassurance” – Beck (Citation2004, p. 34)Footnote1

Introduction

In 1987 Robbie Davis-Floyd described obstetric training as a “rite of passage”, an initiatory process of transition into a technological model of childbirth (Davis-Floyd Citation1987). Doctors, on their way to become professionals who ought to provide support in the challenging process of giving birth, attain an alienated objectified distance to the labouring human, fragmenting her body into different parts and mechanisms, failing to conceive of the emotional, spiritual and psychological dimension of giving birth. As a result, they become professionals in the medicalisation of childbirth, instead of in caring for people in childbirth physically and emotionally. Davis-Floyd conceptualised obstetric training as a forceful rite of passage consisting of a disciplinary integration into the common values and beliefs of the obstetric institution through techniques that resemble the military. She opened her article with the following citation of Stephen Saunders, MD:

Why is medical school the way it is? I think it’s part of the idiocy that goes on with the good ol’ boy approach – “we did this back in my day, by God, and you’ve got to do the same thing” – it’s like the Marine Corps and that sort of thing. It’s a crazy thing that’s gotten in the habit of perpetuating itself (Davis-Floyd Citation1987, p. 288).

“As students you don’t necessarily see it at this stage, but you go on and you keep seeing these things, and at some stage you’re going to pick it up and you’re going to internalise it. I think that’s the biggest danger in that they’re actually breeding students who end up being just like the doctors that we don’t want to be.” (SA, 2015)Footnote2

“ … students among each other are acting cool, like they do not care, they’re just acting tough, and the competition is unbearable. […] [T]he problem is this whole macho culture that is there from the start.” (NL, NO, 2020)

“ … a vicious circle: you can’t draw your own boundaries, because they [the midwives] have transgressed their boundaries long ago and continue to do so.” (NL, MV, 2020)

One thing has changed, though. There is increasing public awareness, also among students, about topics such as obstetric violence and obstetric racism, and acknowledgement of the influence of colonialism on the institutions that were founded in modernity. The students’ conscious feminist and anti-racist assessment of their training tells us that they feel forced to collude in obstetric violence and racism in order to become a doctor or midwife. This makes transparent that obstetric training should not merely be understood as a rite of passage into a technological model of childbirth as Davis-Floyd (Citation1987) has argued, but as an initiation into a misogynistic, heteronormative, colonial, and racialised institution, and thus as an initiation into practices of reproductive injustice through obstetric violence. Why is obstetric violence a necessary part of the initiation into the obstetric institution? Why does the obstetric subject need obstetric violence to constitute and affirm itself? And why does it seem so impossible to treat mothers with respect, something that is so obviously necessary in childbirth? (Kingma Citation2021).

Obstetric violence is a term originating from the early 2000s, introduced by South American activists to raise awareness about mistreatment of people during childbirth as violence (Sadler et al. Citation2016; Williams Citation2018; Villarmea Citation2015). It consists of, but is not limited to, unconsented procedures, neglect, gaslighting, shaming, racism, and discrimination (Bohren Citation2015; Chadwick Citation2018; Cohen-Shabot Citation2020; Cohen-Shabot & Korem Citation2018; Davis 2019; Villarmea & Guillén Citation2011). Subsequently, obstetric violence has been recognised and acknowledged in almost every country globally, leading to more and more international recognition of this form of gender-based violence, culminating in a 2019 United Nations’ report (Šimonović Citation2019). Although it is widely accepted among scholars and activists that obstetric violence is gender-based violence, it is less recognised that it is race-based violence as well, as Dána-Ain Davis has argued, coining the term “obstetric racism” (Davis 2019). Not only are maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality rates globally worse for people of colour, obstetric violence is also reported to be more prevalent among people of colour globally, especially in postcolonial countries (Davis Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Bohren Citation2019, Citation2015; Sen, Reddy & Iyer Citation2018; Betron Citation2018; Miltenburg Citation2018).

Although we live in a postmodern, postcolonial society, the obstetric institution can still be regarded as fundamentally modern and as a locus of coloniality, due to its refined biopolitics concerning racialised reproduction and its strong roots in modern rationality (Weinbaum Citation2004, Citation2019; Bridges Citation2011, Owens Citation2018). Denise Ferreira da Silva (Citation2007) critiques the modern, post-Enlightenment European subject as the transcendental master of universal reason, and shows how postmodern scholarship in anthropology and sociology tries to critique the white male modern subject but typically ends up defending its position. The problem is, Silva points out, that we are tempted to think that we should solve the logic of exclusion of the subaltern subject through emancipatory inclusion. We are then blind to the fact that it is not possible to simply include those who are excluded, since their exclusion has a vital function in the constitution of the dominant subject. The ‘subaltern subject’, Silva explains, cannot be included into modern subjectivity, because it is itself as much a product of modernity as the modern subject, and was thus never ‘forgotten’ or ‘excluded’ in the first place. Rather it was engulfed in the foundation of modern subjectivity as its necessary other. In this paper we follow Silva’s argument by showing that the (m)other cannot merely be included as an equal subject in obstetrics, since she is the necessary (m)other of modern obstetric subjectivity.

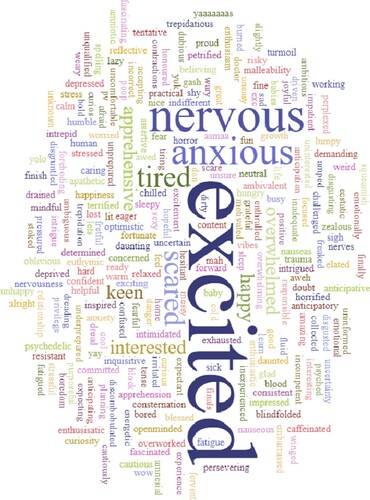

Figure 1: Collage of drawings created by medical students reflecting on their obstetrics experiences (SA, 2015).

By merely recognising the obstetric rite of passage as ‘technological’ then, we understand Davis-Floyd’s call for change as a revaluing of the mother over technology, aimed to win back the autonomy or self-determination taken from her by the machine. However, this critique fails to challenge that, in fact, the dominant subject position of the obstetrician or midwife is dependent on the existence of the mother as a suppressed subject. The mother cannot simply be included as a subject within the obstetric institution through a devaluation of technology, since her suppression is not tied to technology, but to the obstetric subject itself. To address this, we focus on a more fundamental transition that becomes manifest in the many instances of obstetric violence in students’ rite of passage. As such, we lay bare a movement of violent engulfment of the (m)other that constitutes the obstetric self, consisting of the appropriation of the mother as other, subaltern and affectable, “stripped from … individuality, dignity, control, communication, … [and] trust” (Beck Citation2004, p. 34). Therefore, the rite of passage should be understood not merely as a transition into a technological model of birth, but as an initiation into an active, assertive, and responsible subject-position that is founded on (m)others’ oppression. Following the critique of modern biopolitical institutions of Achille Mbembe (Citation2019, Citation2001) we furthermore argue that the rite of passage of students is one into a modern necropolitical institution that engulfs the mother of colour through a negation, instead of affirmation, of life.

In order to make visible that obstetric violence and obstetric rationality characterise the obstetric rite of passage globally, we locate our study in two different colonially related geopolitical spaces, namely South Africa and the Netherlands. These countries share a colonial past and as such represent a linkage, that can be deemed exemplary for the global distribution of wealth, subjectivity, bio- and necropolitics, and, our focus, obstetric violence. We present this linkage as exemplary to make manifest a modern and colonial continuance in obstetrics between contexts that are usually perceived as radically different, one being African and one European. As such, we are able to locate a more fundamental level of the rite of passage that is exposed by obstetric violence and obstetric racism. Hypothetically, this rite of passage can thus be found in obstetric institutions worldwide, since becoming an obstetric subject requires an engagement with the modernity and coloniality of the institution, which are present globally.Footnote3

The modern obstetric subject and its affectable (m)other

Modernity is foundational for contemporary science and impossible to disentangle from the coloniality of power, the conceptualisation of gender, and the history of slavery (Mignolo Citation2018; Quijano Citation2007; Lugones Citation2007; Federici Citation2004). It gave rise to a specifically modern onto-epistemological configuration, that is, the simultaneous constitution of subjects and knowledge of man, establishing who counts as human, differentiating people through racialising and gendering science. Regarding obstetric practice and science specifically, the onto-epistemological configuration of subjectivity became mutually exclusive with having a uterus and/or being of colour (Villarmea Citation2020; Owens Citation2018).

Modernity is furthermore characterised by a switch in power from sovereign to biopower (Foucault Citation2003; Quijano Citation2007). Biopower rules through disciplinary medical, criminal, military, educational and policing institutions (Foucault Citation2003). Heavily critiqued for its purely European focus, it is argued that the concept cannot grasp another related power responsible for the construction of racially differentiated people. Mbembe understands this as ‘necropower’, mitigated not through the disciplinary production of life, but through a negation of life (Mbembe Citation2019). Obstetrics can be regarded as a bio-necro collaboration, as it relies on the knowledge gained over the female body during colonial rule and slavery and applies both bio- and necropower to onto-epistemologically produced differentiated, racialised subjects of unequal standing and vulnerabilities (Mbembe Citation2019; Puar Citation2007; Gilmore Citation2007; van der Waal Citation2021).

In her seminal work Towards a Global Idea of Race, Denise Ferreira da Silva (Citation2007) traces the history of European self-consciousness. She determines the constitutive moment of modern reason to be the self-identification of the European subject with universal reason, constituting, in other words, itself as universal reason. Thereby, the modern subject was established as transcendental (above the ‘matter’ or the laws of nature), interior (undetermined by external laws), and transparent (without a body) (Silva Citation2007, p. 255). However, this position of the transcendental “I” of universal reason could not be attained solely by the subject itself. It is built on a constitutive movement of othering. Its relation to the outside world is captured by what Silva calls ‘the scene of engulfment’ of modern science, which is characterised by the colonisation and appropriation of ‘everything else’. In Hegel or Darwin, for instance, everything exterior to the transcendental subject is taken up in a universal movement of progress of the evolution of the Spirit or the natural laws. The transcendental subject is located at the end of progress, as the final outcome of evolution, being the only one with insight into the evolvement of natural laws, while remaining undetermined by them. As such, he engulfs everything else that is part of the movement that led evolution to himself, leaving everyone else, in so-called different stages of development, behind.

Since universal reason was ‘located’ in Europe, ‘Europe’s others’ were engulfed into the European self in an unbridgeable difference, established by modernity, as its subaltern other. In contradiction to the modern subject, the subaltern subject is affectable and fully outer-determined (instead of self-determined), without self-consciousness (thus only knowable by the white man instead of by itself), exterior (with primarily a body), and in particular, constituted by being somewhere outside of Europe (instead of universal) (Silva Citation2007, pp. 117, 255, 257–259). Being ‘written’ in ‘affectability’ posits the subaltern subject between subject and object, not completely objectified, but influenceable, educatable – but too influenceable, un-self-determined and passive to really count or be understood as a modern subject (Silva Citation2007, p. 199).

Through the construction of the post-Enlightenment European male subject as the only one endowed with universal reason, the scene of engulfment was able to contain all land and people outside of Europe as part of the same (universal reason, evolution theory, progress, emancipation, etc.), while grounding them in irreducible difference – an onto-epistemological configuration of globality and subjectivity still responsible for the continuous reproduction of racialised subjects (Silva Citation2007). Whiteness became a marker of universal reason, as the representation of European roots that keeps on writing people into an “analytics of raciality” (Silva Citation2007, p. 3).

In the case of obstetrics, this expressed itself in scientific discussions in Europe that revolved around whether having a uterus meant a causal exclusion from reason (Villarmea Citation2020) and life-threatening and non-anaesthetised experimentation on Black enslaved women which gave doctors unlimited access to the female body, that they never had before (Owens Citation2018). These practices began after the closing of the transatlantic slave trade, when slave owners and doctors focused on practices of ‘slave-breeding’ as an alternative (Weinbaum Citation2019; Owens Citation2018), marking the birth of modern obstetrics. It comes to the fore that the existence of modern obstetric subjectivity was fully dependent on the engulfment of Black enslaved women and European women in universal reason, while they were being written in affectability and exteriority.Footnote4 As white women were engulfed through a biopolitical confinement focused on the enhancement of safe reproduction, Black women were engulfed as a “public (non-European or non-white) place produced by scientific strategies where their bodies were immediately made available to a transparent male desire” (Silva Citation2007, p. 266).

European women, with some exceptions such as the Irish, were biopolitically engulfed and racialised as white, while non-European women were racialised as non-white, leaving them more “vulnerable to premature death” within the practice of obstetrics (Gilmore Citation2007, p. 28). The engulfment of women of colour can therefore be understood as necropolitical, leading to death through experimentation and exploitation, contributing towards medical progress that would primarily serve white women. These practices racialised, gendered, and engulfed pregnant people in universal reason as objects of knowledge, while at the same time excluding them from being subjects of universal reason themselves. They became affectable, outer-determined subjects, bodies that could be studied and delivered, while constituting the obstetrician in the same movement as the one endowed with universal reason and self-determination, that is, the one who delivers her. This self-understanding as active on the part of the obstetrician instead of the mother is still commonly used in obstetric training, counting how many deliveries one should do in order to graduate.

In postcolonial, post-slavery societies, the onto-epistemological dependency on the analytics of raciality resulted in the racialised nation state through a double logic of exclusion and obliteration. Exclusion is most visible in forms of apartheid, recognisable in obstetrics in the medical apartheid of accessibility, as well as the division of public and private healthcare. Obliteration is the “emancipatory” engulfment, the “inclusion” of the other, that actually effaces the other and becomes apparent in the denial of obstetric racism – despite vast differences in mortality and morbidity outcomes. It is also apparent in the (re)production of group-differentiated vulnerabilities, as well as the continuation of obstetric violence, unconsented eugenic practices, and reproductive injustice against mothers of colour (Ross & Sollinger Citation2017; Gilmore Citation2007).

By practising within the logics of obliteration and apartheid, the obstetric subject still constitutes itself through the violent engulfment of the maternal body, as the autonomous, self-determining agent of birth that delivers the racialised (m)other of her child. Hence, obstetrics is still onto-epistemologically reproducing the violence that is the groundwork of its rationality and institution, accounting for the epistemic and reproductive injustice equated with obstetric practice (Villarmea & Kelly Citation2020; Chadwick Citation2020).

Two geopolitical locations: Data collection and analysis

Our research in two colonially related geopolitical spaces, South Africa and the Netherlands, highlights a congruence with the obstetric institution globally. Since obstetric violence is a global phenomenon, we aim to substantiate our argument that obstetric training produces the modern obstetric subject through the engulfment of its affectable (m)other, racialised in logics of apartheid and obliteration, and bio- and necropolitics, by investigating differently located obstetric traineeships.

South African context

Reproductive health in South Africa is haunted by the legacy of a double logic of exclusion and obliteration during the apartheid regime. For instance, Depo-Provera injections became a tool of power for the apartheid government to control Black population growth (Scully Citation2015). Black women of child-bearing age, many of whom worked at white-owned farms and factories, were subjected to these three-monthly contraceptive injections. This follows the logic of obliteration, as they are prevented from reproducing. Also, they were written in complete outer-determination as consent was not even in question.

The logic of apartheid expresses itself in terms of institutional arrangements: separate facilities were built for the white, European population and the so-called non-Europeans that included racialised groups categorised as Black, Coloured, Indian and Asian. Post-apartheid, the logic of exclusion and white supremacy largely remain, albeit more invisible. The economic wealth of the white minority provides access to private healthcare, supported by corporate medical aid structures. Chadwick points to the “bifurcations and binaries” reflected in birth narratives from “privileged (often white) South African mothers birthing in high-tech settings” (2018, p. 7) in the private sector as opposed to marginalised Black mothers birthing in under-resourced public health settings. It remains a problem for the poor Black majority to even access public healthcare (Mbembe Citation2015; Mhlange & Garidzira Citation2020).

For undergraduate medical students in South Africa, clinical internships take place in the public health facilities. Medical training is mostly six years in duration. Midwives learn their skills amidst a four-year general nursing education. After training in public hospitals, many graduates then move across to the private sector, capitalising on the necropolitical engulfment of Black (m)others while building their own professional subjectivity. From within the public sector, obstetric violence is relatively well documented as a human rights violation, with increasing visibility revealing numerous forms of mistreatment (Šimonović Citation2019; Rucell et al. Citation2019; Pickles Citation2015). In the private health setting, obstetric violence is less well documented, but presents as more ‘gentle’, normalised violence (Chadwick Citation2018).

Veronica Mitchell’s doctoral research project related to the learning experience of medical students, who differed in ethnicity, age, social class and religion, at the University of Cape Town. She drew on data collected from three focus groups with medical students, and semi-structured interviews with 3 medical students, 13 midwives, 12 clinician educators and 3 departmental administrators, all of whom were also asked to complement the discussions with drawings (Mitchell 2019).Footnote5 Moments that “glowed” (MacLure Citation2013) were brought to the fore and studied through relational ontology, rather than through coding with themes in a conventional structured analysis.

The Netherlands context

As postcolonial theorist Gloria Wekker argues, the Netherlands is an exemplary country for the pervasiveness of the European myth of ‘white innocence’ where racism continues to be denied in terms of ‘colour-blindness’ and the self-image of a nation characterised by tolerance (Wekker Citation2016). Contrary to countries like South Africa, race and racism remain topics that are rarely openly discussed, thereby establishing the idea of an innocent self that cannot be responsible for things their forefathers did so far away. This contributes to the idea that race is not a problem in Europe as it is in countries like South Africa or the United States (Wekker Citation2016).

In such a context, racism in obstetric care remains unacknowledged. Also, the influence of the colonial past on obstetric care stays unaddressed, while the plantations of Suriname were infamous for being particularly brutal for women who had to submit to reproductive duties (de Kom Citation2020 [Citation1934]). These possibly included practices of ‘breeding’ (similar to those in the US) after the closing of the transatlantic slave trade in 1814 (Brana-Shute Citation1985, p. 233). There were also attempts to implement colonial obstetric medicine in Indonesia and traditional Indonesian midwives’ knowledge was appropriated and ridiculed in the context of obstetric science (Marland Citation2003; Hesselink Citation2009). Students hence train in the unacknowledged afterlife of a colonial past that characterises its obstetric institution through adverse outcomes for marginalised communities, something we can understand as the logic of obliteration following Silva (Silva Citation2007; Schutte et al. Citation2010; Gieles Citation2019; de Graaf Citation2013; Gilmore Citation2007).

Although obstetric violence in the Netherlands is not extensively documented, the existence of the activist movement Geboortebeweging (Birth movement), the action #genoeggezwegen (enough silence), and research linking traumatic experiences to the behaviour of healthcare workers, show the widespread practice of mistreatment in both midwifery and obstetric care (van der Pijl Citation2020; Hollander Citation2017). The Netherlands is one of the last countries in Europe to have a strong, independent primary care midwifery system, although it is continuously under pressure. While independent midwifery care has its own philosophy with its own values and practices (woman-centred relational care focused on the physiology of childbirth), and while some midwives are highly critical and resistant, independent midwifery overall can be regarded as part of the modern obstetric institution. Because of the discrepancy between the ideals of midwifery and the reality of the internships, and because students are not taught to critically understand this discrepancy as the curriculum lacks education in feminist and critical race theory, students often feel that the midwifery philosophy is a ‘myth’ (NL, MV, 2020). The existence of this myth, as something that one keeps hoping for but never encounters, is exhausting, frustrating, and confusing: “In the academy they stimulate you to develop your own vision on midwifery, but in practice it is almost impossible to have the freedom to practice how you want to practice” (NL, MV, 2020).

There are three midwifery academies. Unlike in South Africa, midwifery is an independent bachelor programme of four years, with no link to nursing. Rodante van der Waal conducted interviews and one focus group in 2020 with the same five midwifery students, who were enrolled in Amsterdam and Rotterdam: 1) NO, a white middle-class mother of a young daughter and an artist who is in the final year of her midwifery training; 2) MV, a Black middle-class woman who is in the final year of her midwifery training; 3) AM, a woman of colour and mother who is in the third year of her midwifery training; 4) EH, a white higher middle-class woman who is in the third year of her midwifery training; and 5) MB, a white heterosexual middle-class woman in the final year of her midwifery training.Footnote6

The semi-structured individual interviews lasted approximately two hours each. They were analysed thematically using grounded theory, after which the established themes provided the basis for further elaboration in a focus group of three hours, which was again thematically analysed. The participants were given the chance to read and give feedback on the final research analysis and their quotations used in the paper.Footnote7

How the contexts talk to each other

South Africa and the Netherlands are deeply connected through their colonial past. The convenient positioning of South Africa on the shipping route between the East and West enabled the establishment of the Dutch East India Company’s power base in the 17th century at the Cape of Storms, being the first colonisers of South Africa. After Britain took over imperial rule, the Dutch established themselves as the ‘Afrikaner’ community, a powerful white actor in the development of the ideology of white supremacy, to which the Dutch word apartheid bears testimony.

Our linkage between South Africa and the Netherlands indicates that the affectability of (m)others, and especially (m)others of colour, is not only written in the global South but is still fundamentally linked to as well as produced within Europe. The continuance of a similar kind of obstetric violence as part of the obstetric training shows that there is a global colonial continuity within the obstetric system regarding obstetric violence and obstetric training. We have identified the rite of passage (see below), in the Netherlands in midwifery training and in South Africa in obstetric training, but our hypothesis would be that a similar rite of passage might be identified in obstetric institutions elsewhere, both within and outside of Europe. This linkage of South Africa and the Netherlands is hence meant to show the continuance of the universality of the obstetric institution as carried by the modern obstetric subject in two traditionally juxtaposed continents whose relation is constituted by colonialism.

The rite of passage

Drawing further on the above established theory of the obstetric bio- and necropolitical engulfment of (m)others, based on Silva and Mbembe, we elaborate on the obstetric rite of passage which reproduces obstetric subjectivity through this continuous engulfment, by having to collude in obstetric violence.

Davis-Floyd understands a rite of passage as: a) “a patterned, repetitive, and symbolic enactment of a cultural belief or value” (Davis-Floyd Citation1987, p. 288); that is b) “transitional” in nature, always involving “liminality” (p. 289); and c) as demanding a “retrogression of participants to a lower level of cognitive functioning […] and extreme redundancy combined with heightened affectivity” to ensure and facilitate “unquestioning acceptance” of the institutional norms and values (p. 289), having as its goal to d) “mould the belief system of the individual into coherence and symmetry with that of the larger group or society” (p. 91).

Three stages can be distinguished in the rite of passage. Firstly, there is a separation of the participants from their preceding social surroundings; secondly, there is a period of transition in which they have neither one status nor the other; and thirdly, there is an integration phase in which they are absorbed into their new social state (Davis-Floyd Citation1987, p. 288). Drawing on Davis-Floyd’s definition of the rite of passage, we will use the same characterisation of the three stages of separation, transition and integration. With the help of our theorisation of the obstetric institution and obstetric subjectivity following the work of Mbembe and Silva, we have identified seven instances of obstetric violence that indicate the engulfment of the (m)other, within the three stages of the rite of passage. All these instances consist of implicit or explicit obstetric violence that points towards a more fundamental level of the rite of passage, namely the constitution of obstetric subjectivity through engulfment of the racialised (m)other.

We identify the following violent instances. In the stage of separation: 1) emotional isolation; and 2) having to adapt the goals, norms and values of the obstetric institution that instrumentalise the (m)other. Then, in the stage of transition: 3) establishing subjectivity through assertiveness, competition and learning at the cost of (m)others; 4) colluding in explicit obstetric violence, obstetric racism and sexual violence; and 5) traumatic experiences. Conclusively, in the stage of integration: 6) complicity: balancing guilt with numbness; and 7) responsibility at the cost of (m)others.

Despite the differences between South Africa and the Netherlands, as well as between an obstetric and midwifery education, we identify a similar trajectory in both contexts. Below, we elaborate on these instances of necessary violence and show how much obstetric violence is ingrained in their training.

Separation

Obstetric and midwifery training in both South Africa and the Netherlands consists of extremely intense internships within the obstetric institution. As Davis-Floyd points out, “one result of such overload is the increasing isolation it creates” (Citation1987, p. 299). Social isolation makes students less capable of reflexivity and more distanced from the ideals that motivate their education choice and their emotional engagement (Davis-Floyd, Citation1987, p. 299): “To be able to do this training, you have to distance yourself, block your empathy and not feel what somebody else feels, only then you can do what you have to do” (NL, MV, 2020). According to Davis-Floyd, isolation is “a prerequisite to the achievement of the necessary cognitive retrogression”, necessary to ensure the internalisation of the institutional routine (Citation1987, pp. 299, 300).

Resilience has become a key objective in medical training (Dyrbye & Shanafelt Citation2012). When students address problems of workload, stress, burn-outs, or worries related to obstetric violence or guilt to teachers, it is not the system that is questioned, but the students themselves: “When I addressed my concerns to the teachers, I was told that I was probably too sensitive for the job” (NL, NO, 2020). Or: “they told me that I also have to be able to do it in the normal [i.e. violent] way” (NL, MV, 2020). The fact that they are not taken seriously can be seen as an effective way to cut ties to exteriority, laying the groundwork for a highly individualised and interior modern subjectivity that is rational instead of emotional, and is tough instead of vulnerable, unaffected by what is ‘outside’. Hence, students emotionally isolate themselves from their peers, their teachers, and, most importantly, the mothers they serve.

A technique reflective of the separation from one’s former self and previously held norms, is the necessity to adopt the goals of the obstetric institution that tend to instrumentalise mothers: “[The violence is] just repeated and repeated and repeated to the point where it becomes the norm” (SA, 2015). Mandatory numbers of medical practices contribute to the instrumentalisation of mothers and obstetric violence: “The logbook forces a student to focus on numbers rather than people […], students are held at ransom for the signatures” (SA, 2015). Such pressures to reach curricular goals force students to be strategic, finding shortcuts to acquire the logbook sign-offs that represent achieving the required numbers of curricular tasks such as deliveries and episiotomies. For instance, clinicians in South Africa notice students going off to do something else, then arriving back just in time to perform the delivery because it is the logbook tick that counts rather than their relationship with the birthing mother.

In the Netherlands it is, for instance, difficult for midwifery students to attain the necessary number of episiotomies (a cut in the perineum, vagina and pelvic floor to quicken delivery) because midwives typically avoid this controversial intervention that has a wide range of variability in usage within the country (Seijmonsbergen-Schermers Citation2020). Consequently, students sometimes have to do an additional two-week internship before they are able to graduate. This is commonly referred to as a ‘cut-internship’ (‘knip-stage’). The inherent violence embedded in the goals and values of the training is revealed in referring to an internship wherein one supposedly cares for people, as ‘cutting’ into the most intimate body part. This not only objectifies people’s bodies, but also appropriates vaginas as something that should be cut as this is so clearly stated as the goal and essence of the internship. Such processes force students to repeat the scene of engulfment, wherein (m)others are being taken up as part of the development of their obstetric subjectivity:

“We should learn to never see someone as a means to reach your goals. But we’re taught exactly the opposite, namely, to be happy when we can cut, because we need those episiotomies to graduate.” (NL, NO, 2020)

“If I didn’t want to be an accomplice, I should’ve walked out of so many rooms […] I mean, those five cuts that you have to make, I think that's one of the worst forms of obstetric violence. And that is literally legally expected of you. Legally.” (NL, MV, 2020)

Transition

Through either competition, being assertive or being pro-active regardless of the mother, professional subjectivity is developed. A midwife in South Africa shared how one student assaulted another because the other one “stole her delivery” (SA, Midwife Sibela, 2016). Learning based on these values can be understood as effectively establishing a subject position at the expense of mothers. When students object in defence of the mother, they often get scolded:

“The midwife scolded me for not using my opportunities to learn, telling me I will never be a midwife … I don’t agree. My learning-process is not more important than her birth-experience.” (NL, AF, 2020)

“I can now confess that it makes me feel deeply guilty and ashamed that I let myself be pressured into those things – I was trying to be assertive and to learn.” (NL, EH, 2020)

“It’s like it’s just a part of it, if I’m being very honest … to just continue to press deeper with one’s fingers into the woman’s vagina when she screams stop. You are taught to say ‘No, I really have to feel further! You have to be strong now!’ and then you continue. It seems like becoming a midwife means learning how to cross somebody else’s border, to learn how to just push a bit further to get what you want.” (NL, AF, 2020)

In both countries, students practise their clinical skills more on people of colour. This is a classic characteristic of both obstetric racism and medical apartheid, as it has always engulfed people of colour to practise and experiment on (Owens Citation2018; Washington Citation2006). In the Netherlands, the majority of the population is white, and everybody is enrolled in public healthcare. The students state, however, that supervisors let them practise more on mothers of colour:

“Those women do not know that it is not normal to always have two vaginal examinations after each other, and they do not know that they can refuse, while Dutch women would probably know that, so with them they do not dare to try.” (NL, EH, 2020)

Students also report prevalent prejudices regarding the loudness and level of pain of Asian, Black, and Arabic mothers. In both our studies, we heard about the joking and gossip in team rooms among midwives regarding marginalised mothers, as something through which students get conditioned to take their pain and personhood less seriously.

Additionally, students claim that marginalised mothers are less informed and are treated with more normalised violence, effectively continuing to write them in affectability:

“Even if people thank you a lot, I feel like, hmmm, we have actually kept everything a secret from them, like we purposefully kept them stupid, leaving them with the feeling that it’s probably normal how we’ve treated them.” (NL, EH, 2020)

“They [mothers in public health facilities] don’t know anything … and it’s not fair because why should they get less of a respectful and accommodating health system just because they can’t afford private care?” (SA, Student 2, FG 2015)

“I will treat a Black person like that, but if you put me with say another race on that bed, my attitude will change and my behaviour will change.” (SA, 2016)

The students also make a connection between obstetric violence and sexual violence, a well-known association (van der Pijl et al. Citation2020; Cohen-Shabot Citation2016; Richland Citation2008):

“Sometimes I think, when a supervisor asks me something, what you’re asking of me is if I can rape that woman. To me, that is traumatic. Once, I refused, I said I’m not going to do it. If you want it to be done, then you do it yourself. And then she became extremely angry with me in the hallway.” (NL, MV, 2020)

“It was so recognisable that it kept me awake at night. … to witness that they just come in, don’t say their name, and put their fingers in. For me that’s horrible to see, because I’ve experienced how that is, and it’s horrible. And if you see that with others, I feel it again myself.” (NL, EH, 2020)

For some students, both in South Africa and the Netherlands, witnessing and colluding in obstetric violence is hence a traumatic experience:

“I think the one thing that people don’t realise is that what you encounter there as a student … can be traumatic, it doesn’t sit well with you, and it can be something that eats you up.” (SA, 2015)

“You ask me, what precisely is traumatic? Well, all the things that you see, that fact that you have to contribute to this system, that you are literally complicit in somebody else’s trauma.” (NL, MV, 2020)

Integration

Students learn that accompanying childbirth responsibly and being respectful cannot be practised at the same time:

“Their [the teachers] response to my questions always has to do with responsibility. That I do not fully understand it right now because I do not have the responsibility yet. This indicates that if you have principles, you are naïve, like I only now have the luxury to have ideals because I do not have responsibility yet. Like responsibility makes all those other things [like empathy, relationality] impossible.” (NL, NO, 2020)

In South Africa medical students take up their professional responsibility in clinical settings earlier than the midwives in the Netherlands. Anxiety, apprehension and fear are felt by many, as well as a high level of excitement ():

“I don’t think that’s really appropriate for someone of that age, of that experience level, to be dealing with those situations alone. You’re calling for help and no one’s coming” (SA, 2015).

“When a fellow midwife in training asked the mother for consent during an emergency training, they made it super difficult for her to pass the training: The actress [playing the mother] said no to the intervention in an extremely exaggerated way, and almost died. The student failed. So, I thought, okay, I should not ask for consent if I want to pass this test.” (NL, MV, 2020)

Conclusion

Students’ obstetric and midwifery training can be theorised as a rite of passage wherein obstetric subjectivity is constituted. In this process the identity of the student is moulded so that the student becomes part of the institution. Robbie Davis-Floyd (Citation1987) has criticised the obstetric rite of passage to be too ‘technological’ in nature, which is the reason, according to her, that obstetrics lost sight of the mother as a subject. In this article we have argued that the problem with obstetric training is more fundamental than that. We have determined instances of violence as part of the rite of passage, indicating that it is not merely an initiation into a technological model of childbirth, but one into obstetric subjectivity that occurs through the engulfment of the (m)other through obstetric violence, racism and trauma. The obstetric rite of passage thereby constitutes obstetric subjectivity not through technology, but through the appropriation of the pregnant body as a (less worthy) part of the obstetric self, thereby engulfing the maternal as othered: as an affectable, outer-determined subject excluded from autonomy, rationality and self-determination.

This becomes manifest in that students are from early on conditioned into a position wherein they are endowed with responsibility over the mothers’ and babies’ bodies, pressured to decide what should happen with the mother’s body even if this includes violating her, and pushed to fight for their own interests over the backs of mothers. This is (re)productive of both the modern obstetric subject and, necessarily in the same movement, its affectable (m)other, rendering the labouring body always in passivity, writing her in affectability through obstetric violence, thereby preventing relational connection and care.Footnote8 By merely understanding the problem of the rite of passage as technological, this subjectification of students through the appropriation of the maternal body remains unchallenged. Therefore, in order to arrive at the more fundamental problem of the obstetric rite of passage, we have focused on the question why obstetric violence and obstetric racism are an essential part of obstetric and midwifery training, thereby revealing the structural appropriation of the maternal body on which obstetric subjectivity is constituted.

Answering this question, we have shown that the reproduction of obstetric subjectivity follows the logic of the reproduction of the modern, post-Enlightenment European subject, the subject of coloniality and globality (Silva Citation2007). We have developed this argument through showing how obstetrics should be understood as a global modern institution through the linkage of two colonially related geopolitical places, namely South Africa and the Netherlands. In both places, the obstetric subject can only constitute itself through engulfing the maternal body as its other, thereby reproducing her racialisation and suppression. The birthplace of the obstetric institution can be understood as having its fundament in the necropolitical engulfment of Black women and marginalised people, thereupon further developing through a biopolitical engulfment of white women in the Global North. All remain, in different ways, excluded from the position of power and subjectivity within the obstetric institution, as all are appropriated into the obstetric subject that constitutes itself through othering the mother.

The exclusion of the (m)other within the obstetric institution, then, rests upon her inclusion as othered, engulfed, and appropriated. As such, she is excluded through her inclusion, and obstetric subjectivity and the position of the mother as other are thus fundamentally tied together. Her suppression, therefore, can only be truly challenged by dismantling obstetric subjectivity. For it is not the case that the pregnant subject is not included in the institution already, she is in fact a fundamental part of it, but in an affectable, outer-determined way through which she is excluded from autonomy, rationality, and self-determination by merit of existing within the obstetric configuration. Attempts at emancipating the pregnant subject, trying to endow her with more modern subjectivity without dismantling obstetric subjectivity and its rite of passage, are therefore doomed to fail as obstetric subjectivity is made up of her inclusion as a lesser part of itself, again and again established by the obstetric rite of passage.

As Silva (Citation2007) argues, because of the scene of engulfment, we cannot solve the logic of exclusion through which the modern subject is forced to constitute itself through programmes aimed at inclusion. In obstetrics these would, for instance, be striving for informed consent and shared decision making. However important, without undoing obstetric subjectivity and its rite of passage, the obstetric subject will remain resting upon the included exclusion of (m)others from modern subjectivity. Informed consent will then become another box to check and shared decision making an illusion masking unequal power relations, and thus her exclusion. Consequently, the goal should not be to attain modern subjectivity for the pregnant subject since this is also an emancipatory project of inclusion.

In addition, and as importantly, we must not forget that universal modern subjectivity always already rests upon differentiation between groups of people and their included exclusion. The emancipatory conquering of modern subjectivity for one group often means the stricter exclusion of another group. Regarding obstetric violence, we see that the fight of white cis-gender women in the Global North for autonomy in the labour room does not at all mean that the Global subaltern subject profits from this fight. Quite the opposite: problems that white cis-gender women in the Global North strive to counter are not the same problems Black people, people of colour, trans and non-binary people have with reproductive care, constituting their liberation again on leaving others behind. Continuing this way, we would only attempt to solve the biopolitical engulfment of white women, leaving the necropolitical engulfment of the reproduction of the subaltern subject to exist in the trenches of racial capitalism.

As a direct descendent of the founding fathers of obstetrics at the height of modernity, the obstetric subject will persist globally as long as its institution will refuse to be anything else but modern, continuously dismissing intersectional feminist and post- and decolonial critique. Instead of striving for the emancipation of the biopolitically engulfed pregnant subject, we must therefore work on the dismantling of obstetric subjectivity and its rite of passage. A first step would be to resist the obstetric rite of passage by providing education for future midwives and obstetricians that affirms and enhances their critical thought, by using a Reproductive Justice framework throughout their education (Ross & Sollinger Citation2017). Furthermore, echoing the philosophy of Sylvia Wynter (Citation2015), we must undo the obstetric rite of passage of which obstetric violence and racism are constitutive parts, by writing a new narrative of fertility, birth, and care, that can generate new rites of passage that can unearth the relational and plural potential of pregnancy, birth, and midwifery care to figure out, in praxis, how to disrupt modern subjectivity and be human together otherwise. Only new rites of passage aimed at this disruption will make it possible for us to be, once again, in safe relation with each other. Instead of turning to pleas of inclusivity and emancipatory subjectivity, we should work towards dismantling obstetric subjectivity and trying to figure out, through the potency of the transgressive event of childbirth, how we can give birth through caring for birth – intimately and safely – in equal relation with one another.

Acknowledgement

This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant number 120845) and by ZonMW (project number 854011008).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rodante van der Waal

RODANTE VAN DER WAAL (1992) is an independent midwife in Amsterdam and a PhD candidate at the University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Her PhD study investigates obstetric violence from feminist, postcolonial and care-ethical theory. She has a BA and MA in Philosophy (cum laude) and wrote her MA thesis on the ontology of pregnancy and Pregnant Posthuman subjectivity (see the lemma in: Posthuman Glossary (2018), eds Braidotti and Hlavajova). She is the editor of Contractions, a political podcast on midwifery. For more information see: www.rodantevanderwaal.nl. Email: [email protected]

Veronica Mitchell

VERONICA MITCHELL is a Research Associate in the Women’s and Gender Studies Department at the University of the Western Cape. She also facilitates student workshops in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. She holds a PhD from the University of the Western Cape. Her physiotherapy background and her experiences in human rights education led to her interest in exploring the medical curriculum and the force it has on students’ becoming. She promotes the production of Open Educational Resources as a sharing of knowledge for the public good. Her publications include a research blog, authored websites, and journal papers. Email: [email protected]

Inge van Nistelrooij

INGE VAN NISTELROOIJ is associate professor Care Ethics and Maternity (Care) researcher at the University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht, the Netherlands. She holds a PhD from the University for Humanistic Studies. She is coordinator of the Care Ethics Research Consortium (care-ethics.org) and co-founder and chair of the research network ‘Concerning Maternity’. Her research and education focus upon care ethics, maternity, maternity care and midwifery, relational and embodied identity, affectivity, ethical deliberation in institutional/professional care, French phenomenology, and self-sacrifice (Van Nistelrooij 2015, Leuven: Peeters). For complete information see https://www.ingevannistelrooij.com. Email: [email protected]

Vivienne Bozalek

VIVIENNE BOZALEK is an Emerita Professor in Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of the Western Cape, and Honorary Professor in the Centre for Higher Education Research, Teaching and Learning at Rhodes University. She holds a combined PhD from Utrecht University in the Netherlands and the University of the Western Cape. Her research interests and publications include the political ethics of care and social justice, posthumanism and feminist new materialisms, innovative pedagogical practices in higher education, and post-qualitative and participatory methodologies. She is the editor-in-chief of the open source online journal Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Contrary to Beck (Citation2004), we use the term ‘mothers’, not women, unless it is specifically about women as a class, to identify a social economical gendered subject category, not a biological sex determination. We choose to use this gendered term because we consider obstetric violence to be a form of gender-based violence and reproductive violence specifically directed against the maternal (Van der Waal forthcoming). To support the use of the word mother as a social, economic, gendered subject category, we follow Silvia Federici (Citation2004, p. 14): “ … if ‘femininity’ has been constituted in capitalist society as a work-function masking the production of the workforce under the cover of a biological destiny, then ‘women’s history’ is ‘class history,’ and the question that has to be asked is whether the sexual division of labor that has produced that particular concept has been transcended. If the answer is a negative one (as it must be when we consider the present organization of reproductive labor), then ‘women’ is a legitimate category of analysis, and the activities associated with ‘reproduction’ remain a crucial ground of struggle for women”. We group ‘mothering’ under gendered reproductive labour, but at the same time regard it, as it refers to the practice of mothering, as a more open and less biologically determined category than ‘women’: anybody can do the reproductive labour of mothering that is traditionally gendered as women’s work, including giving birth.

Furthermore, in this paper we understand the (m)other as a subject position that is reproduced during childbirth in the obstetric institution. Here, we want to follow Johanna Hedva’s usage of the term woman as a subject-position in her Sick Woman Theory: “To take the term ‘woman’ as the subject-position of this work is a strategic, all-encompassing embrace and dedication to the particular, rather than the universal. … I choose to use it because it still represents the un-cared for, the secondary, the oppressed, the non-, the un-, the less-than. … The Sick Woman is anyone who does not have this guarantee of care” (Hedva Citation2016). We believe that the same counts for the subject position of the (m)other, who is uncaringly constituted and reproduced during childbirth in the obstetric institution, as we will elaborate upon in this paper. This does not mean that people with a uterus who do not identify as ‘mothers’ are not victims of obstetric violence; on the contrary, their refusal of this gendered subjectivity typically leads to more, not less, violence.

2 We first refer to the country, SA for South Africa and NL for the Netherlands, then we refer to the students (either anonymous or with their initials), then we refer to the year the quote from the student is from. The students participating in this research in South Africa are all medical students and in the Netherlands they are all midwives.

3 We wish to thank our first reviewer for this specific phrasing.

4 This is what Deirdre Cooper Owens (Citation2018) argues throughout her book Medical Bondage, in which she makes a case for the acknowledgement of the Black enslaved woman as the mother of modern obstetrics, next to its infamous fathers.

5 For this paper, we refer mostly to the transcribed texts from engagement with the undergraduate medical students.

6 Rodante’s participants were asked how they identified and how they wanted to be referred to.

7 Veronica’s research findings were anonymised and with time and curricular pressures there was no opportunity to return to the research participants.

8 As suggested by one reviewer, it would have been interesting to juxtapose what students say about obstetric violence with what mothers themselves say about their experiences. We will consider this idea for further research, as multiple voices and perspectives would come into dialogue to paint a more complete and complex picture.

References

- Beck, CT 2004, ‘Birth trauma, in the eye of the beholder’, Nursing Research, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 28–35.

- Betron, ML, McClair, TL, Currie, S & Banerjee, J 2018, ‘Expanding the agenda for addressing mistreatment in maternity care: A mapping review and gender analysis’, Reproductive Health, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 143. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0584-6.

- Bohren MA, Mehrtash H, Fawole B, Maung TM, Balde MD et al., 2019, ‘How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: A cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys’, Lancet, vol. 394, no. 10210, pp. 1750–1763. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0

- Bohren, MA, Vogel, JP, Hunter, EC, Lutsiv, O, Makh, SK, Souza, JP & Gülmezoglu, EM 2015, ‘The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review’, PLOS Medicine, vol. 12, no. 6.

- Brana-Shute, R, 1985, The Manumission of Slaves in Suriname, 1750–1828, PhD dissertation, University of Florida.

- Brison, S 2003, Aftermath. Violence and the Remaking of the Self, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Bridges, KM 2011, Reproducing Race. An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of Racialization, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Cohen-Shabot, S 2016, ‘Making loud bodies “feminine”: A feminist-phenomenological analysis of obstetric violence’, Human Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 231–247.

- Cohen-Shabot, S & Keshet K 2018, ‘Domesticating bodies through shame: understanding the role of shame in obstetric violence’, Hypatia vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 384–401.

- Cohen-Shabot, S 2019, ‘Amiga’s, Sisters, we’re being gaslighted’, in C Pickles & J Herring (eds), Childbirth, Vulnerability and the Law, Routledge, New York. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429443718)

- Cohen-Shabot, S 2020, ‘Why “normal” feels so bad: violence and vaginal examinations during labour – a (feminist) phenomenology’, Feminist Theory, pp. 1–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700120920764

- Chadwick, R 2020, ‘Practices of silencing Birth, marginality and epistemic violence’, in C Pickles & J Herring, Childbirth, Vulnerability and the Law, Routledge, New York. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429443718)

- Chadwick, R 2018, Bodies that birth. Vitalizing Birth Politics, Routledge, New York.

- Davis-Floyd, R,1987, ‘The technological model of birth’, The Journal of American Folklore, vol.100, no. 398, pp. 479–495.

- Davis, D 2019a, ‘Obstetric racism: The racial politics of pregnancy, labor, and birthing’, Medical Anthropology, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 560–573. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2018.1549389.

- Davis, D 2019b, Reproductive Injustice. Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth, New York University Press, New York.

- Dyrbye, L & Shanafelt, T, 2012, ‘Nurturing resiliency in medical trainees’, Medical Education, vol. 46, no. 4, p. 343.

- Federici, S 2004 The Caliban and the Witch. Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation, Autonomedia, New York.

- Foucault, M2003, Society Must Be Defended. Lectures at the Collège de France 1975–1976, D Macey (trans.), Picador, New York.

- Gieles, NC, Tankink, JB, Van Midde, M, Düker, J, Van der Lans, P, Wessels, C et al. 2019, ‘Maternal and perinatal outcomes of asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Europe: a systematic review’, The European Journal of Public Health, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 714–723.

- Gilmore, RW 2007, Golden Gulag. Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Graaf, J de, Ravelli, ACJ, De Haan, MAM, Steegers, EAP, & Bonsel, GJ 2013, ‘Living in deprived urban districts increases perinatal health inequalities’ The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 473–481.

- Hedva, J 2016, ‘Sick women theory’, http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory. accessed 22 February 2021.

- Hollander, MH, van Hastenberg, E, van Dillen, J, van Pampus, MG, de Miranda, E, & Stramrood, CAI 2017, ‘Preventing traumatic childbirth experiences: 2192 women’s perceptions and views’, Archives of Women’s Mental Health, vol. 20, pp. 515–523. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0729-6.

- Hesselink, L 2009, Inheemse dokters en vroedvrouwen in Nederlands Oost-Indië 1850–1915, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

- Kingma, E 2021 ‘Harming one to benefit another: The paradox of autonomy and consent in maternity care’, Bioethics, forthcoming.

- Kom, A de 2020 1934, Wij slaven van Suriname, Atlas Contact, Amsterdam.

- Lugones, M 2007, ‘Heterosexualism and the colonial/modern gender system’, Hypatia, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 186–209.

- MacLure, M 2013, ‘Researching without representation? Language and materiality in post-qualitative methodology’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 658–667.

- Marland, H 2003, ‘Midwives, missions, and reform: colonizing Dutch childbirth services at home and abroad ca. 1900’ in M Sutphen & B Andrews, Medicine and Colonial Identity, Routledge, London.

- Mbembe, A 2015, Apartheid futures and the limits of racial reconciliation, Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, Johannesburg.

- Mbembe, A 2019, Necropolitics, S Corcoran (trans.), Duke University Press, London.

- Mbembe, A 2001, On the Postcolony, University of Wits Press, Johannesburg.

- Mhlange, D & Garidzirai, R 2020, ‘The influence of racial differences in the demand for healthcare in South Africa: A case of public healthcare’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 14, p. 5043. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145043

- Mignolo, W & Welsh, C 2018, On Decoloniality, Duke University Press, London.

- Miltenburg, AS, van Pelt, S, Meguid, T, & Sundby, J 2018, ‘Disrespect and abuse in maternity care: individual consequences of structural violence’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 53, pp. 88–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1502023.

- Owens, DC 2018, Medical Bondage. Race, Gender and the Origins of American Gynecology, Georgia University Press, Athens.

- Pickles, C 2015, ‘Eliminating abusive “care”: A criminal law response to obstetric violence in South Africa’, South African Crime Quarterly, vol. 54. doi: https://doi.org/10.4314/sacq.v54i1.1.

- Pickles, C & Herring, J 2020, Women’s Birthing Bodies and the Law. Unauthorised Intimate Examinations, Power and Vulnerability, Hart, London.

- Puar, J 2007, Terrorist Assemblages, Duke University Press, London.

- Quijano, A 2007, ‘Coloniality and modernity/rationality’, Cultural Studies, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 168–178.

- Ross, LJ & Solinger, R 2017, Reproductive Justice. An Introduction, University of California Press, Oakland.

- Rucell, J, Chadwick, R, Mohlakoana-Motopi, L & Odada, KE 2019, ‘Submission on: Obstetric Violence in South Africa. Violence against women in reproductive health & childbirth’, in D Šimonović (ed.), A human rights-based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence, UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

- Sadler, M, Santos, MJ, Ruiz-Berdún, D, Leiva Rojas, G, Skoko, E, Gillen, P & Clausen, JA 2016, ‘Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: Addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 24, no. 47, pp. 47–55.

- Scully, JAM 2015, ‘Black Women and International Law’, in JI Levitt (ed.) Deliberate Interactions, Movements and Actions, pp. 225–249, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139108751.013.

- Schutte, JM, Steegers, EAP, Schuitemaker, NWE, Santema, JG, De Boer, K & Pel, M 2010, ‘Rise in maternal mortality in the Netherlands’, BJOG, vol. 117, pp. 399–406.

- Sen, G, Reddy, B & Iyer, A 2018, ‘Beyond measurement: the drivers of disrespect and abuse in obstetric care’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 53, pp. 6–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1508173.

- Šimonović, D 2019, A human rights-based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence, Vote by the Secretary-General, United Nations Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

- Silva, DF de 2007, Toward a Global Idea of Race, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Richland, S, 2008, ‘Birth rape: Another midwife’s story’, Midwifery Today, vol. 85, Spring, pp. 42–43.

- Ross, LJ & Sollinger, R 2017, Reproductive Justice. An Introduction, University of California Press, Oakland.

- Seijmonsbergen-Schermers, A 2020, Intervene or Interfere? Variations in Childbirth Interventions and Episiotomy in Particular, PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

- Van der Pijl, MSG, Hollander, MH, Van der Linden, T, Verweij, R, Holten, L, Kingma, E, et al. 2020, ‘Left powerless: a qualitative social media content analysis of the Dutch #breakthesilence campaign on negative and traumatic experiences of labour and birth’, PLOS One, vol. 15, no. 5, e0233114.

- Van der Waal, R, 2021, Understanding obstetric violence as necropolitics. Playing the “dead baby card”, maternal subjectivity, and the matricidal logic of separation. Forthcoming.

- Villarmea, S & Guillén, 2011, ‘Fully entitled subjects: Birth as a philosophical topic’, in Ontology Studies, vol. 11.

- Villarmea, S, 2015, ‘On obstetrical controversies: Refocalization as conceptual innovation’, in A Perona (ed.), Normativity and Praxis. Remarks on Controversies – Philosophy 13, Mimesis International.

- Villarmea, S, 2021, ‘Reasoning from the uterus: Casanova, women's agency, and philosophy of birth’, Hypatia, vol. 36, p. 1.

- Villarmea, S, 2020, ‘When a uterus enters the room, reason goes out the window’, in C Pickles & J Herring (eds.), Women’s Birthing Bodies and the Law: Unauthorised Medical Examinations, Power and Vulnerability, Hart Publishing, Oxford, pp. 63–78.

- Villarmea, S & Kelly, B 2020, ‘Barriers to establishing shared decision-making in childbirth: Unveiling epistemic stereotypes about women in labour’, Journal of Evaluation of Clinical Practice, vol. 26, pp. 515–519. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13375.

- Washington, HA, 2006, Medical Apartheid. The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, Harlem Moon, New York.

- Wekker, G, 2016, White Innocence. Paradoxes on Colonialism and Race, Duke University Press, London.

- Williams, CR, Jerez, C, Klein, K, Correa, M, Belizán, JM & Cormick, G 2018, ‘Obstetric Violence: A Latin American legal response to mistreatment during childbirth’, BJOG: Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 125, no. 10, pp. 1208–1211.

- Weinbaum, AE, 2004, Wayward Reproductions. Genealogies of Race and Nation in Transatlantic Modern Thought, Duke University Press, London.

- Weinbaum, AE 2019, The Afterlife of Reproductive Slavery. Biocapitalism and Black Feminism’s Philosophy of History, Duke University Press, London.

- Wynter, S 2015, ‘Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations’, in K McKrittick (ed) Sylvia Wynter, on Being Human as Praxis, Duke University Press, London.