abstract

The interdependent, collective agency shown by women of African descent reveals the possibility of making Black lives matter, even in the death-worlding structures of carceralism and coloniality. This article emancipates penal abolitionist theorising from whiteness by centring Black political womanhood. I argue that the legacy of anti-imperial and anti-capitalist struggle contributes to an archival haunting of the colonial carceral diaspora.

Methodologically, this article cross-reads three narratives of borderless resistance, considering Claudia Jones, La Mulâtresse Solitude, and Stella Nyanzi as figures who fight and collectivise before, during and after incarceration. To counter the coloniality of time, this article unmoors itself from period-based or ‘tensed’ language. As coloniality remains present for the three, I endeavour to connect their struggles in and for the present and frame their resistance using Black, African, and anticarceral feminist literature. Ultimately, by centring these stories, the article positions today’s abolition as emergent from an African praxis of direct action, anti-capitalist critique and rehumanisation in prisons and colonies.

Perhaps when La Mulâtresse Solitude decides to fight, she holds her ballooning belly and hums a song of liberty to her unborn child. Guadeloupe has known freedom from enslavement for eight years due to the Law of 4 February 1794, and yet Napolean has decided to reinstate African enslavement to the benefit of French planters. Solitude, however, is known to be a Maroon – while she was born into slavery, she lives her teens and adult years as a fugitive in a settlement away from the island’s sugar and coffee plantations. But Napolean’s nearing navy carries the promise of chattel slavery for those racialised as Black, threatening all but the planters on the island. Solitude’s refusal of the return to slavery manifests in a steadfast determination to raise arms. Pregnant, she fights alongside Louis Delgrès, her revolutionary rage sparking legends.

Before the insurgency ends, Solitude and the Black rebels blast gunpowder stores, desperate for a lasting freedom in life or death. Unlike most others she survives, is captured and imprisoned. Solitude becomes immortal at the age of 30, giving birth in prison a day before execution. While the French colonisers imagine Black value only in relation to the imperial economy – saving her son for his extractive value as an enslaved commodity – Maroon knowledge leads us to imagine Black lives matter for the very fact of being. It is this epistemology – this fugitive knowledge – that brings us to the time-defying, context-expanding abolitionist imagination.

Like the call for abolition, La Mulâtresse has only multiplied. She stands as statues in Guadeloupe and more recently in Paris. The Parisian monument to Solitude was birthed in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter rallies throughout Europe and the United States of America (USA), to rid itself of colonial nostalgia erected as statues of enslavers, imperialists, and brutalisers (Abraham Citation2021). The toppling of public commemorative displays follows movements such as Rhodes Must Fall in South Africa (Marschall Citation2017) and globally witnessed events such the 2018 toppling of a Mahatma Gandhi monument in Accra, Ghana, by university students critical of his historical anti-Black racism. In strong contrast to the public recognition or celebration of European colonial heritage, Solitude’s defiant posture offers young abolitionists the possibility of imagining a lasting resistance to racial capitalism. The international Black Lives Matter movement impacted the rebirth of Solitude’s story in Paris in 2022, after years of struggle as a movement that began in 2013, yet relies on the lifeworlds created by centuries of struggle for African sovereignty, life, and joy.

I believe much can be told through Solitude’s haunting half-life. The abolitionist spirit revives through movement organisations such as Black Lives Matter, which dedicates its website to “Imagining Abolition” (see https://blacklivesmatter.com/imagining-abolition/), understood as the project of organising an alternative social infrastructure capable of ending systems of racialised deprivation and violence. It endeavours to raise consciousness of the possibility of sustaining life amid death worlds, but also to ending the death world rendered by carcerality. By death worlds, I refer to Achille Mbembe’s (Citation2019, p. 40) concept that describes the “new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead”. They are physical, political, and social formations that subject African people to perpetual loss, injury, and early death. I use it to advance a speculative geography, a way to remap our connections away from the merely physical realities of land masses and oceans. The current penal abolitionist movement is one such struggle against the death world, focusing primarily on prisons, policing, medicalised and psychiatric incarceration, border patrol and encampment. Many within the movement situate these deadly spaces and practices in a time continuum of enslavement and coloniality (Alexander Citation2010; Davis Citation2003; Nagel Citation2008; Pfingst & Kimari Citation2021; Saleh-Hanna Citation2008).

How we can recentre the transnational legacy of African women’s resistance to carceralism to better understand their contribution to today’s abolitionist imagination? Alongside Pfingst and Kimari (Citation2021, p. 697), I consider carceralism the social mechanism “defining and determining criminality and authorising spatial, temporal, and material modes of punishment,” which reanimates coloniality through “inordinate surveillance, arbitrary detention [and] zones of separation”. The stories cited here serve as sites of resistance to colonial punishments such as involuntary servitude, imprisonment, immigrant detention, displacement, and their political economic underpinnings. In turn, the sites of resistance, I argue, speak to penal abolition, defined not as the movement against oppressive institutions, but that which seeks to end the ideologies that uphold and reanimate them. The emphasis of penal abolitionist movements depends on regional politics, economies, and histories. Throughout Africa and its diaspora, historically this may mean the abolition of European governments, political remnants, and capital extraction, and recently, “can be viewed as an extension of the movement to abolish colonization: in fighting to remove colonial institutions of control one continues to fight colonialism in Africa” (Saleh-Hanna Citation2008, p. 429).

The entangled logics of gender and prisons

The history of the prison itself is deeply intertwined with colonial administration and systems of control. The invention of prisons in Africa was “part of the machinery of the brutal slave economy … not as an agency of the criminal justice system but as a tool for organized crimes against humanity” (Agozino Citation2008, p. 250). Prisons are crucial to maintaining the imperial and neoimperial economy as the forced labour within sustains war (Bruce-Lockhart Citation2014; Gilmore Citation2007; Oparah Citation2004) and reinforces the coloniality of race and gender (Davis Citation2003). The mushrooming of the total institution works to regularly employ “banishment from the community” or a social execution, which during precolonial times would have been a last resort rather than a default response to social offences (Saleh-Hanna Citation2008, p. 60; Nagel Citation2015). Incarceration rates for African women around the world have risen sharply, and often rely on allegation and indigence rather than any infraction of the law (Agozino Citation2008). Therefore, we must be deeply critical of the function of prisons in society and the global commitment to social control through carcerality.

Abolitionist feminist Angela Davis argues that gender structures the prison. The very design, function, and logic of prisons are set upon gendered ideologies that emphasise a natural binary, imbue privileged assumptions and form differentiated punishment for people coded men, women, or otherwise gender deviant. One such assumption embedded within the prison structure is that normal, ‘natural’ women are less inclined to engage in criminalised behaviour (Davis Citation2003). This assumption leads to the pathologisation of the ‘few’ who end up incarcerated, particularly the poor, the queer, the sexual, and the racialised (Ben-Moshe Citation2020; James Citation1996; Mogul, Ritchie & Whitlock Citation2011; Thuma Citation2019). It also encourages different, ‘reformational’ actions as corrective control (Ben-Moshe Citation2020; Nyanzi Citation2020). These reformatory practices include homesteading: cooking and cleaning, tending to animals, and laundry and textile services (Davis Citation2003; Nyanzi Citation2020; Saleh-Hanna Citation2008). Therefore, women’s prisons are often mistakenly dismissed as inherently ‘nicer’ places than men’s and criminology often (problematically) reports the reformatory orientation of rehabilitation as one that is better than the environment of men’s prisons.

Indiana Women’s Prison, 1873. This was the first prison specifically for adult women. The image shows a room of women of African descent tending to clothing, and was sourced from the University of Warwick Modern Records Centre.

However, we must ground ‘rehabilitation’ in its necessary precursor of pathologisation and understand that punishment and incapacitation continue to coexist with if not supersede the reformatory logic. Detained women have been referred to as “crazy,” “unstable,” “hysterical” or even “witches” by colonial administration in Kenya (Bruce-Lockhart Citation2014). As such, rehabilitation often looks like forced psychiatrisation and medicalising women’s reform; these medicines may create embodied prisons within the imprisoned body (Pfingst & Rosengarten Citation2012; Thuma Citation2019). To rehabilitate is to identify a fundamental unwellness – a wrongness – in someone and restore them to the (ableist, racist, sexist, ageist) imagined ideal version of themselves. It not only ignores structural conditions that lead to many criminalised acts, but it also displaces blame on survivors of violence for their trauma (Oparah Citation2010; Richie Citation2012, Citation2018). ‘Doing time’ is imagined to correct behaviours, but not the societal cultures that reproduce harm (such as domestic abuse, rape culture, poverty, etc.). Notably, in some African indigenous sensibilities ‘doing time’ means suffering awayness – an irreparable severing from the sense of the collective self (Nagel Citation2015).

Furthermore, women’s imprisonment is incapacitative on various levels: first, removing purportedly deviant women from society preserves the idea and image of the pure woman (Davis Citation2003) and isolates surplus women from greater society during their potentially reproductive years (Appleman Citation2018; Gilmore Citation2007). The extralegal punishments received while incarcerated are well documented, especially the rates of rape and sexual assault which traumatise those incarcerated (Stohr Citation2015). This carceral trauma is disabling, thereby structurally, physically, and psychologically altering the public participation of people of all genders who are considered surplus (Ben-Moshe Citation2020; Nagel Citation2015; Nelson Citation2010).

As such, anticarceral feminists argue that societal disablement is a cyclical project. Structural neglect and carcerality exist outside of the prison and then funnel women into the further disabling environment of the prison (Nelson Citation2010; Richie Citation2012). They are then ejected, traumatised, back into society, less able to live fulfilling and dignified lives (Nelson Citation2010). Therefore, many argue that women’s imprisonment supports the aims of eugenics: removing the racialised, poor, queer and disabled from the public in the short term and in a progressive, eugenicist sense (Appleman Citation2018; Ben-Moshe, Chapman & Carey Citation2014; Roberts Citation1997). This argument is only supported by the critical scholarship into the practices of abortion, sterilisation and antenatal neglect in carceral facilities (Stern Citation2005; Roberts Citation1997).

However, in a more general sense, we must understand that women’s imprisonment serves to stop the ‘unruly African’ from challenging the social order of white supremacy. This social death – or “expulsion from humanity” is a facet of necropolitics (Mbembe Citation2019, p. 21) that we need to recentre to understand the strategic silencing of women of African descent. While this argument is well worn in literature about men as political prisoners, women are often excluded from this perspective and study. Recentring African political womanhood brings us to a different analysis of carceral repression and gender. As Amadiume (Citation1987) informs, Igbo womanhood was initially curious to the colonial eye due to their steadfast political participation and revolt. African womanhood does not and has never meant docility; African women have historically played very crucial political roles in defying imperialism, creating public knowledge, and resisting nationalist repression (Bruce-Lockhart Citation2014). Reconciling this truth with the facts of women’s imprisonment as a reflection of the political project of enforcing a sexed binary brings us to question imprisonment as always political, and always about maintaining a social order that favours coloniality. Eslanda Goode Robeson (1954) writes:

When I was a little girl I used to think that only criminals, bad, wicked evil people, dangerous to the community, were put in jail. Now I am a woman grown, living in a rapidly changing world, I know that very often, very good, very wonderful people are put in jail because they are dangerous – not to the community – but to the few, sometimes very wicked and corrupt people who are in power.Footnote1

Narratives that travel and resistance literature as methodology

Methodologically, I consider three women whose narratives have travelled over time and oceans. La Mulâtresse Solitude, Claudia Jones, and Stella Nyanzi have crafted or inspired resistance literature that reveals women’s unique contribution to rebellion against foreign domination and nations’ “internal struggles against patriarchal domination and class oppression” (Boyce Davies Citation2007, p. 101). Resistance literature provides a generative primary source through which I can analyse the diversity of experiences of solidarity within prisons as well as the sense of urgency to end conditions of confinement arising from those imprisoned. Simultaneously, the narratives that travel about imprisoned women hold revelatory insights into the staying power of stories: reality is crafted from narrativised activism and political fighters. This discursive reality forms a collective memory – a haunting – that I argue contains a power to sustain movements.

Simultaneously, the stories of these women elucidate the connections of the colonial carceral diaspora. As a project of Black alternative mapping, I imagine the colonial carceral diaspora as a product of the dispersal of technologies of punishment and surveillance applied to African people and the dispersal of African people through such penality, particularly forced migration. I consider this diaspora in relationship to the work of Mecke Nagel (Citation2008, p. 5), who argued that the USA has created a “new Diaspora of prison cages” by trafficking African descendants from prison to prison, already historically displaced by slavery. However, this analysis extends beyond the USA and includes African continental participation in imprisonment, which has physical and motivational roots in colonialism. For critical criminologist and African Feminist Viviane Saleh-Hanna (Citation2015, p. 18), “what involuntarily binds us together are the institutionalized, thus wide-reaching and repetitive praxis of colonial violence”. As such, I consider connection or what binds us in the senses of both violence and creation; this is the nature of diaspora.

Because I am interested in the overlap of experience and expression despite time, I write these struggles in the present tense. For me, this is both an Afrofuturist and Black Feminist Hauntological endeavour (Saleh-Hanna Citation2015). Jah Elyse Sayers (Citation2021, p. 61) points to Afrofuturism as an imaginative project that creates a less constrained future for African people, while reorienting “Black Atlantic temporality toward both the production of futures and development of countermemory”. In considering the productive power of countermemory, I acknowledge cumulative time, rather than passing time. Viviane Saleh-Hanna (Citation2015, p. 20) charts out Black Feminist Hauntology, a methodology describing the

anti-colonial analysis of time that captures the expanding and repetitive nature of structural violence, a process whereby we begin to locate a language to speak about the actual, not just symbolic or theorized violence that is racial colonialism.

The hauntological quality of my analysis rests in the destabilisation of time and lifespan, especially the lifespan of philosophical and spiritual presence. The narrative connects the lasting structures of penal harm while simultaneously uplifting the immortal shapeshifting of resistance. The afterlives of these women and their work timelessly display the power to affect and unsettle the colonial carceral diaspora. Lastly, despite the global impact of prisons, I make the methodological decision to focus on African political womanhood (Were Citation2020). This conceptual frame points to the development of the categories of both Africa and woman as “contingent invention(s) of Western, patriarchal epistemes” that we should analyse, problematise and expand, rather than essentialise or assume (Were Citation2020, p. 561). The social construction of Africa, its borders and characteristics often contracts in response to political aims. The same holds for the concept of womanhood. By choosing cases of women of African descent, I demonstrate the differential conceptualisation and treatment of womanhood when arbitrated by racialisation as Black. I also write of African women because they are often unmentioned when referencing political imprisonment. These revolutionaries call for radical collectivity against the co-constitutive, white supremacist forces of imperialism: (cishetero)sexism, racism, and capitalism. Their stories interweave the complex harms – physical, spiritual, material, and sexual – that shape racialised and sexed subjection. More grippingly, the perseverance of their messages – which defy temporal bounds and spatial borders – inspires the future of abolitionist movements globally.

Border-resistant politics, art, and social movements

In Notting Hill, London, steel pans are beaten by African migrants from the Caribbean islands. The joyous music moves through and rises above a crowd of over a million celebratory carnival-goers. Its rhythm migrates from West and Central Africa to Trinidad and the Southern Caribbean, to England, surviving generations of force, desperation, and deportation. So too does Claudia Jones. In founding the event, she writes, “a people’s art is the genesis of their freedom.” Much as today’s penal abolitionist philosophy arises from a “general critique of capitalist social structures that rely heavily on the existence of a surplus labour population” (Saleh-Hanna Citation2008, p.426), she imagines that England’s police brutality, white supremacy, and brutal capitalism can be brought down by united African peoples.

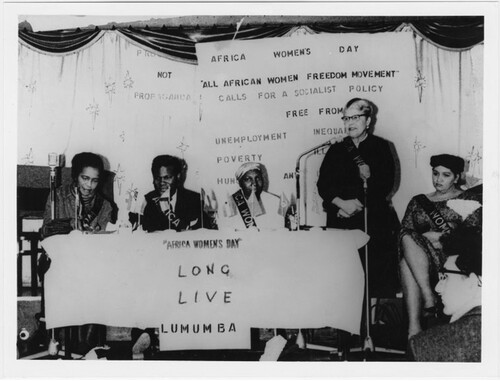

All African Women’s Day, 1961. Claudia is seated at the far left, while Eslanda Goode Robeson speaks. Image sourced from the New York Public Library, shelfmark b16060681.

Claudia, born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, begins the West Indian Gazette in London after she is deported from New York City. As many freedom fighters of African descent in the 19th and 20th centuries, she is a communist. Her indefatigable organising power and political presence in the USA leads her to serve time for the Alien Registration Act, a law in place to criminalise “advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government” (Smith Act, 1940). Between the carcerality of poverty, gender, and disability, and her actual incarceration, she lives in an archipelago of carceral cells. She is ordered to be deported under the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950. In her words, she owes her deportation to the “McCarthyite hysteria against independent political ideas in the USA – a hysteria which penalizes anyone who holds ideas contrary to the official pro-war, pro-reactionary, pro-fascist line of the white ruling class” (Jones & Boyce Davies Citation2011, p. 16). The hearings occur as she is twice held between 1948 and 1950 at Ellis Island, a federally owned immigrant detention island overlooked by the Statue of Liberty. Between the hearings and her deportation, she enters a seven-year cycle of arrest – hospitalisation – commutation or bail-based release. Her heart begins to fail before she reaches 40 years old.

Beyond the bars and the bail and her breaking heart, her spirit triumphs, indomitable. She writes poetry while incarcerated (Boyce Davies 2007, p. 121):

Like fellow imprisoned poet Assata, Jones spends her life writing for personal and collective survival, and the future survival of the movement indeed hinges upon her contribution to the archive. The West Indian Gazette becomes known as the first major Black magazine in England, publishing ‘Afro-Asian-Caribbean news’, especially about racial violence in Britain and global decolonial politics. Claudia and her team of editors maintain the monthly publication for six years between its founding and Claudia’s earthly departure.

Claudia reading the West Indian Gazette. Image sourced from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library: ‘Claudia Jones reading the West Indian Gazette, London, 1960s’, New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8e0c7013-086c-11df-e040-e00a18064afe

However, Claudia’s presence remains through the sound systems staged in Notting Hill on the first day of Carnival after the global pandemic of COVID-19. Like Claudia, who passed early at the juncture of structural neglect and disability, the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted people of African descent in England. When August comes and it is time for the parade, festivalgoers crowd together, mixing the spirit of Claudia’s message: when slow death is most apparent, so too must be our resilience and joy. Beyond the foreground of the many smiling faces of dancing children playing mas, many points of Westbourne Park Road display spray-painted messages of ‘Justice’ in the background: ‘Justice for Grenfell’Footnote2, ‘Justice for George Floyd’.

In the Black feminist mind, these messages are intimately connected. As Audre Lorde (Citation2012, p. 74) writes to white women on the social importance of recognising difference:

Raising Black children … in the mouth of a racist, sexist, suicidal dragon is perilous and chancy. If they cannot love and resist at the same time, they will probably not survive

Combatting capitalism, disablement, and criminalisation

Stella is particularly outspoken about the shortcomings of the Ugandan government, especially in relationship to feminised and queer people. For this, she has faced considerable violence, including being arrested for her written, enacted, and embodied protests. Her direct action, spoken addresses and protest poetry are described as fitting ‘radical rudeness’, an “anti-colonial resistance tactic where rebels were deliberately rude, disorderly, intemperate, and obnoxious, as a way of disrupting existing social rituals and systems to mobilise for change” (Kiunguyu Citation2022). Stella’s critiques of the Ugandan President and his wife are criminalised as ‘offensive communication’ and she – like many imprisoned – is punished by the collateral consequences of criminal labelling. Beyond imprisonment, she is ostracised, subjected to material penalties, and forced to suffer incalculable loss.

She names the role of criminalisation in warehousing the poor and the political woman in her book of poetry, No Roses from My Mouth: Poems from Prison (2020). In her unabashed takedowns of Uganda’s prison system, she echoes that which La Mulâtresse and Claudia both sing: colonial carcerality exists to disable the body that it cannot force into its desired shape of productivity. In her case, this disablement occurs through 22 detentions, two longer stints in prison, and then exile (Nyanzi Citation2022). The colonial carceral diaspora interlocks a system that displaces the surplus through various forms of forced migration, whether into the imagined productive location or into the prison. The harms experienced while incarcerated only exacerbate this underlying logic of displacement and deculturation (Nako Citation2018). As she writes, the violence that harms within the prison disables and disconnects minds, bodies, and spirits.

Outside of the text of her writing, it is the solidarity of the Ubuntu Reading Group that ensures that her story survives and breaks through imprisonment as they smuggle her text out of prison. Stella writes (2020):

African feminism for abolitionist futures

We must destroy in order to rebuild

The African diaspora begins as a story of force, migration, labour, and racial identification – but lives as a story of resistance and connection. While the markers of force have shifted rather than died, the resistance and connection have only amplified. What Solitude, Claudia and Stella offer us is a look at how resistance moves across borders and then inspires new generations of movements. Even when meant to be defeated or deported, the revolutionary spirit lives on; it mushrooms in exile. To return to Viviane Saleh-Hanna’s words, African women’s political struggle does not experience death, but rather, it “haunts white supremacy”.

What this haunting gifts us is the vision, truth, and possibility of abolition. According to Dylan Rodriguez (Citation2019, p. 1575):

… abolition is a dream toward futurity vested in insurgent, counter-Civilizational histories – genealogies of collective genius that perform liberation under conditions of duress

The women discussed here demonstrate an abolitionist praxis and thought without necessarily uttering the words. Solitude fights the imperialist prospect of racialised forced labour while Stella critiques the prison’s role in upward redistribution of capital. Claudia fuses communist and racial justice organising at the grassroots and within political structures of the State, while retaining a borderless analysis (Sherwood Citation1999). The three demand that we critically interrogate structural inequities; they position strategy and consideration alongside urgent action, they demonstrate uncompromising will. All insist upon fighting for collective liberation before the future outcome is settled or even imagined. “Live free or die” are the last words Solitude is believed to have uttered: a dictum we can believe guided Stella and Claudia’s unending rebellions.

By connecting histories of criminalised women of African descent, we begin to see how the carceral project is a marker of coloniality (and therefore modernity). The surveillance, punishment, and segregation of women of African descent form an undrawn geography and unknowable temporality that connect the African diaspora in a death world and in cumulative time. With an anticarceral feminist analysis we can identify coloniality as not merely a moment of Western colonialism – the time in which La Mulâtresse Solitude and Claudia Jones fought – but also our current material and political reality. The prison built to encage Stella’s political power, the criminal law meant to protect Western-backed presidents from ‘offensive communication’ and ‘cyber harassment’, the pathologies invented to suppress women’s political participation – all exist as markers of the colonial carceral.

In presenting the three, this analysis destabilises time in service of exploring the living, the undead, and the yet-born. Their survival stories ask us to reckon with what lives and what travels in a broader sense than the physical body; they are transnationally marked in poetry and in sculpture, collectivising strength for generations. Therefore, while the death worlds of segregation, forced labour, and imprisonment operate to silence African women through pathologisation and criminalisation, the methods of revolutionary organising birth lifeworlds. The three connect an archipelago of cells with unified resolve because, as Claudia says: “What is an ocean between us? We know how to build bridges.”

Additional information

Notes on contributors

S.M. Rodriguez

S.M. RODRIGUEZ is Assistant Professor of Gender, Rights and Human Rights at the London School of Economies and Political Science. They are a scholar-activist committed to anti-violence in their community and research. Their work spans the concerns of the criminalised, queer, and/or disabled people of African descent and relies on engaged, qualitative methodologies to answer questions of transformative change. They are the author of The Economies of Queer Inclusion: Transnational Organizing for LGBTI Rights in Uganda (2019). Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Claudia Jones’s essay Ben Davis: Fighter for Freedom was published in 1954 with an introduction by Eslanda Goode Robeson. This can be found in Jones & Boyce Davies (Citation2011) Claudia Jones: Beyond Containment.

2 Grenfell refers to a London housing block called Grenfell Towers, which in 2017 suffered a tremendous fire due structural neglect, and 72 people died, while 70 were injured; 85% of the deaths were people of colour (Townsend Citation2020). It was the worst residential fire in the United Kingdom since World War II.

3 Nwando Achebe offered this during her address to Hofstra University in 2020, in which she discussed human rights from an African perspective. Address attended by author.

References

- Abraham, C 2021, ‘Toppled Monuments and Black Lives Matter: Race, gender, and decolonization in the public space. An interview with Charmaine A. Nelson’, Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice/Atlantis: études critiques sur le genre, la culture, et la justice, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 1-17.

- Agozino, B 2008, ‘Nigerian Women in Prison: Hostages in Law’, in V Saleh-Hanna (ed.), Colonial Systems of Control Criminal Justice in Nigeria, University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa.

- Alexander, M 2010, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, The New Press, New York.

- Amadiume, I 1987, Male daughters, female husbands: Gender and sex in an African society, Zed Books, London.

- Appleman, LI 2018, ‘Deviancy, dependency, and disability: The forgotten history of eugenics and mass incarceration’, Duke Law Journal, vol. 68, p. 417.

- Ben-Moshe, L, Chapman, C & Carey, AC 2014, Disability incarcerated: Imprisonment and disability in the United States and Canada, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- Ben-Moshe, L 2020, Decarcerating disability: Deinstitutionalization and prison abolition, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Boyce Davies, C 2007, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones, Duke University Press, Durham.

- Bruce-Lockhart, K 2014, ‘“Unsound” minds and broken bodies: the detention of “hardcore” Mau Mau women at Kamiti and Gitamayu Detention Camps in Kenya, 1954–1960’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 590-608.

- Davis, A 2003, Are Prisons Obsolete?, Seven Stories Press, New York.

- Gilmore, RW 2007, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Hartman, S 2019, Wayward lives, beautiful experiments: Intimate histories of riotous Black girls, troublesome women, and queer radicals, WW Norton & Company, New York.

- James, J 1996, Resisting state violence: Radicalicism, gender, and race in US culture, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- James, J 2004, Imprisoned intellectuals: America's political prisoners write on life, liberation, and rebellion, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD.

- Jones, C & Boyce Davies, C 2011, Claudia Jones: Beyond Containment: Autobiographical Reflections, Essays, and Poems, Ayebia Clarke, Oxford.

- Kiunguyu, K 2022, ‘Uganda: “Don't Come in My Mouth”, Stella Nyanzi's Second Book of Poems That Rattled Uganda’, All Africa, accessed 10 June 2022, https://allafrica.com/stories/202203080362.html

- Lorde, A 2012, Sister outsider: Essays and speeches, Crossing Press, Feasterville Trevose.

- Marschall, S 2017, ‘Targeting statues: monument “vandalism” as an expression of sociopolitical protest in South Africa’, African Studies Review, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 203-219.

- Mbembe, A 2019, Necropolitics, Duke University Press, Durham.

- McKittrick, K 2011, ‘On plantations, prisons, and a black sense of place’, Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 12 no. 8, pp. 947-963.

- Mogul, JL, Ritchie, AJ & Whitlock, K 2011, Queer (in) justice: The criminalization of LGBT people in the United States, vol. 5, Beacon Press, Boston.

- Nagel, M 2008, ‘Prisons as diasporic sites: Liberatory voices from the diaspora of Confinement’, Journal of Social Advocacy and Systems Change.

- Nagel, M 2015, The Case for Penal Abolition and Ludic Ubuntu in Arrow of God. Working Paper. https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_2231510/component/file2231508/content

- Nako, N 2018, ‘Decolonising the South African prison’, SA Crime Quarterly, vol. 66, pp. 3-6.

- Nelson, CA 2010, ‘Racializing disability, disabling race: Policing race and mental Status’, Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law, vol. 15, p. 1.

- Nyanzi, S 2020, No Roses from My Mouth: Poems from Prison, Ubuntu Reading Group, Kampala.

- Nyanzi, S 2022, The colonialities of incarceration in the Global South [virtual panel presentation], School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London.

- Oparah, J 2004, ‘A world without prisons: Resisting militarism, globalized punishment, and Empire’, Social Justice, vol. 31, no. 1-2, pp. 9-30.

- Oparah, J 2010, ‘Feminism and the (trans) gender entrapment of gender nonconforming Prisoners’, UCLA Women's Law Journal, vol. 18, p. 239.

- Pfingst, A & Kimari, W 2021, ‘Carcerality and the legacies of settler colonial punishment in Nairobi’, Punishment & Society, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 697-722.

- Pfingst, A & Rosengarten, M 2012, ‘Medicine as a tactic of war: Palestinian Precarity’ in M Michael & M Rosengarten (eds.), Body & Society, vol. 18, no. 3&4, pp. 99-125

- Richie, BE 2012, ‘Arrested justice’, in Arrested Justice, University Press, New York.

- Richie, BE 2018, Compelled to crime: The gender entrapment of battered black women, Routledge, New York.

- Roberts, D 1997, Killing the black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty, Pantheon Books, New York.

- Rodriguez, D 2019, ‘Abolition as praxis of human being: foreword’, Harvard Law Review, vol. 132, no. 6, pp. 1575-1612.

- Saleh-Hanna, V 2008, Colonial systems of control: Criminal justice in Nigeria, University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa.

- Saleh-Hanna, V 2015, Black Feminist Hauntology. Rememory the Ghosts of Abolition? Champ pénal/Penal field, vol. 12.

- Sayers, JE 2021, ‘Black queer times at Riis: Making place in a queer Afrofuturist tense’, Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, vol. 22.

- Shakur, A 1987, Assata: An Autobiography, Zed Books, London.

- Sherwood, M, 1999, Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile, Lawrence & Wishart, London.

- Stern, AM 2005, ‘Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California’, American Journal of Public Health, vol. 95, no. 7, pp. 1128-1138.

- Stohr, MK 2015, ‘The hundred years’ war: The etiology and status of assaults on transgender women in men's prisons’, Women & Criminal Justice, vol. 25, no. 1-2, pp. 120-129.

- Thuma, EL 2019, All our trials: Prisons, policing, and the feminist fight to end violence, University of Illinois Press, Champaign.

- Townsend, M 2020, ‘Grenfell families want inquiry to look at role of “race and class” in tragedy’, The Guardian, accessed 20 September 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jul/26/grenfell-families-want-inquiry-to-look-at-role-of-race-and-class-in-tragedy

- Were, MN 2020, ‘African political womanhood in autobiography: Possible interpretive Paradigms’, Auto/Biography Studies, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 557-577.