ABSTRACT

Over the past two decades, variable interest entity (VIE) structures have been used widely for foreign investors to access Chinese industries that are closed or restricted to foreign investment. However, the legality of the VIE structure has been neither recognized nor denied by Chinese authorities in the general sense and has thus been a focus of legal scholarship. Nevertheless, existing literature has rarely covered China’s regulation on VIE usage from 2015 onwards. This article endeavours to narrow the research gap. It argues that the ambiguous legality of the VIE structure is a Chinese regulatory policy for economic development but with legal risks to foreign investors. China’s recent regulation has reflected a policy continuation and not clarified the legal uncertainties of the VIE structure, notwithstanding the occurrence of some positive changes, such as the achievement of the first domestic VIE listing. Instead, against Didi’s US VIE flotation as a trigger, China has been tightening the national control over domestic companies’ overseas listings, which may change the landscape of future VIE listings and help Chinese capital markets become a beneficiary.

I. Introduction

China has achieved striking economic success since the implementation of the national economic reform and opening-up policy in 1978. During this process, foreign investment has played a significant role in terms of a huge volume of actually-utilized foreign capital (over USD two trillion) through the nearly one million foreign-invested enterprises.Footnote1 Part of the foreign capital could not have been raised without a special corporate device named the variable interest entity (VIE) structure which has been conceived for Chinese companies to raise overseas capital on the one hand while complying with China’s regulation on foreign investment in prohibited/restricted industries on the other.Footnote2

Despite the broad usage for two decades, the VIE structure has not gotten its legality confirmed by Chinese authorities. Over the years, disputes have been brought before Chinese administrative and judicial organs to challenge the legality of the VIE structure but have repeatedly reached an ambiguous conclusion. In 2020, the Foreign Investment Law of China (FIL) came into force to encourage inward investment, and the Shanghai Stock Exchange Sci-tech Innovation Board (SSE STAR Board) accommodated the long-awaited first domestic VIE listing. These positive changes have brought back the spotlight on the VIE legality issue. Most recently, Didi’s US VIE flotation triggered Chinese authorities to strengthen the national control over Chinese companies’ future overseas listings, further igniting the VIE debate.

This article examines the ambiguous legality of the VIE structure as a Chinese strategic policy and associated legal risks to foreign investors. The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: Section II broaches the background of creating the VIE structure and its rationale. Section III discusses the blurred legality of the VIE structure in China as a policy choice and the reasons underlying the strategic ambiguity. Section IV probes the legal risks of the VIE structure to foreign investors. Global capital markets’ regulatory reaction to the VIE risks is the theme of Section V. Section VI discusses China’s tightened control over domestic companies’ overseas flotation and looks into potential impacts on the landscape of future VIE listings. Section VII concludes.

II. Why and how are variable interest entity structures used in China?

A. The background of creating the VIE structure

Since 1995, China has employed the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries (Catalogue) to control domestic market access. Initially, the Catalogue stipulated three categories of industries that were binding to foreign investment, i.e. encouraged industries, prohibited industries and restricted industries.Footnote3 Encouraged industries were open to foreign investment, and there was often favourable tax treatment, e.g. exemption or subsidy, to attract overseas capital and technology. In parallel, prohibited industries were closed to foreign investment, and restricted industries often set a ceiling of foreign shareholding in involved Chinese operating companies on an industry-by-industry basis. In this regard, the Catalogue used the ownership structure of involved Chinese operating companies as an important benchmark for deciding market entry into prohibited/restricted industries.Footnote4 Since 2018, a Negative List mechanismFootnote5 has been adopted in China to replace the Catalogue’s stipulation regarding prohibited/restricted industries, which has nevertheless not changed the content of the stipulation (except for annual updates) and the ownership structure benchmark.

Broadly speaking, China has shown an increasingly open attitude towards domestic market openness to foreign investment (see ), which has largely promoted the development of numerous Chinese companies onto a fast track by satisfying their offshore fundraising needs and facilitating their overseas listings. However, problems remain for companies involving prohibited/restricted industries. In light of the ownership structure benchmark, Chinese companies engaging in prohibited industries are not only banned from raising overseas fundsFootnote6 but also theoretically isolated from going public abroad in order to avoid foreign ownership. Likewise, restricted industries limit the potential of raising overseas capital due to the legal cap of foreign shareholding. Thus, it seems that involved Chinese companies encounter a dilemma that comprises two conflicting goals of raising overseas capital while complying with China’s regulation on foreign investment.Footnote7 Facing the two ‘seemingly irreconcilable’ goals, however, sophisticated market players have conceived the VIE structure to solve the inconsistency.Footnote8

Table 1. Restrictions and prohibitions on foreign investment in Chinese industries*.

B. The functioning of the VIE structure

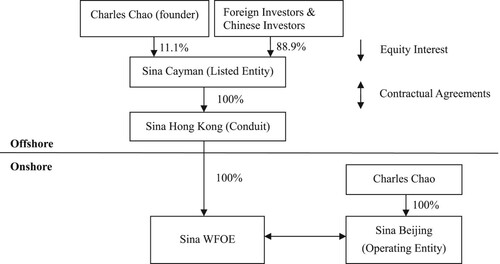

A typical Chinese style VIE structure contains four tiers, including a Cayman-incorporated company that serves as the listed shell upon flotation, a conduit company domiciled in Hong Kong, a wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) based in China, and a Chinese operating entity. Within a VIE structure, the Chinese corporate founder holds shares in the Cayman-based company and usually serves as the sole shareholder of the Chinese operating entity concurrently, as shown in the organizational chart of SINA (the initiator of the VIE structure) below ().Footnote9

Under a VIE structure, two contradictory functions are integrated into a mutual framework with the Cayman-based company responsible for capital-raising while the Chinese operating entity is in charge of business operation.Footnote10 In order to convince foreign investors that they have effective control over the Chinese operating entity, two aspects are necessary to imitate the functions of equity ownership. First, a VIE structure needs to give foreign investors enough confidence that the framework can work as effectively as direct shareholding in the sense of managerial power.Footnote11 Secondly, it must be possible for the economic benefits generated from the operating entity to be consolidated into the financial statements of the Cayman-based company in which foreign investors own shares, thereby enhancing their perception of economic interests in the operating entity.Footnote12 Such objectives are achieved through a package of contractual agreements between the WFOE and the operating entity with the capital injection from the former to the latter in exchange for the managerial power and economic benefits.Footnote13 In practice, arrangements typically used for this purpose are:Footnote14

Interest-free Loan Agreement is signed to provide loans from the WFOE to the operating entity on an interest-free basis for business operation in China. This agreement usually sets a term of the loan (e.g. in the SINA case, it is ten years) in the first instance, and the WFOE could either extend or shorten the term unilaterally.

Loan Repayment Agreement and Share Transfer Agreement are concluded to guarantee that the interest-free loan could be repaid only in the form of debt-equity conversion at a pre-set ratio, which would not be triggered unless China removes the restriction on foreign ownership in the industry that the operating entity involves.

Voting Rights Authorization Agreement is signed to ensure that managerial power inclusive of the total voting power and the right to nominate all the directors of the operating entity is authorized to the WFOE on an irrevocable basis.

Exclusive Technical Service Agreement enables the WFOE to provide technical service to the operating entity in exchange for its total economic benefits.Footnote15

Since the cross-border transfer of economic benefits may result in taxation, tax considerations contribute to the structural complexity of a VIE framework. According to Chinese laws, an overseas-incorporated company that has either an office/establishment or income generated in China is regarded as a non-resident enterprise to pay Enterprise Income Tax at the rate of ten per cent.Footnote16 However, a Hong Kong-incorporated non-resident enterprise as a beneficial owner is entitled to a preferential tax rate of five per cent under the China–Hong Kong special taxation arrangement.Footnote17 As such, for the purpose of tax avoidance, a conduit company at the Hong Kong tier is crucial to a VIE structure. Nevertheless, the preferential tax rate is conditional on two prerequisites, ie the Hong Kong-based beneficial owner holds no less than 25 per cent of the equity in the involved Chinese operating company, and the benefits are transferred in terms of dividends.Footnote18 Since the Chinese operating company needs to stay clear from foreign shareholding including Hong Kong ownership, it is necessary for a VIE structure to insert a WFOE to receive economic benefits from the operating entity in the form of technical service fee, and afterwards, to shift the benefits to the Hong Kong company as dividends.

In light of the ownership structure benchmark, foreign shareholding in a Chinese operating entity involving a prohibited industry definitely contravenes China’s regulation on foreign investment, so does foreign shareholding in an operating entity involving a restricted industry if it exceeds the legal cap. Compared to that, a VIE structure enables foreign investors to obtain a Chinese operating entity’s economic benefits and managerial rights without changing its ownership structure. Since the operating entity is under the 100 per cent of Chinese shareholding in the post-fundraising stage, it is expected that the operating entity could still be recognized by Chinese regulators to permit market entry in prohibited/restricted industries, thereby achieving ‘creative compliance’.Footnote19

Due to the structural complexity of the VIE framework, its legality issue is multifaceted. First, since the VIE structure uses contractual control to circumvent the ownership structure benchmark, the nature of contractual control is central to the VIE legality issue. Is contractual control a form of foreign investment that should be bound to the Catalogue and then the Negative List? Moreover, as foreign investors achieve contractual control through a package of agreements, what is the legitimacy of the contractual agreements per se? Besides, a more fundamental question is whether involved investors in the VIE structure are foreign investors or not? The following section examines the VIE legality issue from a Chinese perspective.

III. The ambiguous legality of variable interest entity structures in China

The broad adoption of the VIE structure may appear to suggest that it is legally recognized in China, especially given that VIE usage in capital markets is clearly known to Chinese authorities.Footnote20 However, the legality of the VIE structure has not been explicitly confirmed. Nevertheless, the VIE legal status has not been denied in the general sense either.Footnote21 This section first broaches the blurred legality of VIE structures in the regulatory practice and dispute settlement in China and then explores the recent Chinese policy direction before looking into the reasons behind the strategic ambiguity.

A. The ambiguous legality of VIE structures in the regulatory practice and dispute settlement in China

Over the years, Chinese regulators have examined VIE structures on a case-by-case basis without formulating a generally applicable criterion. Besides, Chinese arbitration awards have denied the legitimacy of certain VIE structures under very limited and special circumstances, whereas Chinese courts have avoided testing this issue in judicial proceedings. Before embarking on a detailed discussion of the VIE legality issue in the regulatory practice and dispute settlement in China, some cases with similarities will be analysed first to help reveal the Chinese authorities’ standpoint.

1. Cases with similarities to the VIE legality issue

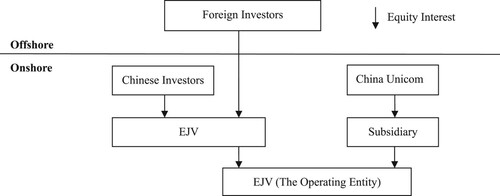

In 1995, a state-owned enterprise named China Unicom tried to bypass China’s regulation on the telecommunication industry – which was closed to foreign investment – by using a so-called Chinese-Chinese-Foreign structure to solve the problem of lacking sufficient capital.Footnote22 Under the Chinese-Chinese-Foreign structure, foreign investors and Chinese investors established a Chinese equity joint venture (EJV) which, jointly with a subsidiary of China Unicom, formed an operating entity to do telecommunication businesses in China (see ).Footnote23 Since the operating entity’s two shareholders, ie the EJV and China Unicom’s subsidiary, were both incorporated in China and thus defined as Chinese companies,Footnote24 it was expected that in light of the ownership structure benchmark, the operating entity’s 100 per cent of ownership under the two Chinese parent companies would legalize its business operation in the telecommunication industry. However, from the standpoint of Chinese authorities, the Chinese-Chinese-Foreign structure helped foreign investors obtain equity in the operating entity to enter the Chinese telecommunication industry and thus constituted a breach of national regulation. As such, after China Unicom raised sufficient capital to expand its business scale, the competent Chinese central regulator invalidated the Chinese-Chinese-Foreign structure in 1998 to strike a balance between economic development and regulatory integrity. The invalidation indicated that the Chinese central regulator focused on the substance rather than the form to decide compliance matters.

Such a ‘substance rather than form’ approach was confirmed in the Chinachem lawsuit in 2013.Footnote25 In this case, a Hong Kong company named Chinachem signed a series of contracts with a Chinese company, entrusting the latter to subscribe to the capital of a Chinese bank and hold shares on its behalf. The Supreme People’s Court of China (SPC) overruled the validity of the contracts by using the Contract Law of China (CL) as the reference point,Footnote26 concluding that the contracts were null due to the illegal effect of helping foreign investors enter the Chinese banking industry.Footnote27

Even though these cases did not involve the VIE legality issue directly and the Chinese-Chinese-Foreign framework was structurally different from the VIE framework, there was barely a functional difference in the evasion of China’s national regulation on foreign investment.Footnote28 As discussed above, under a VIE structure, foreign investors use a package of contractual agreements to obtain the managerial rights and economic benefits of a Chinese operating entity, an effect not essentially different from equity ownership.Footnote29 As such, in light of the ‘substance rather than form’ approach, expectations would be that contractual control over a Chinese operating entity would be treated as a form of foreign investment, and thus the VIE structure would not survive. Yet, reality has shown a different picture.

2. The CIETAC arbitration

In 2010, a dispute was brought before the Shanghai Sub-commission of the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (Shanghai CIETAC) to test the validity of involved VIE contractual agreements.Footnote30 In this case, a foreign investor concluded a series of VIE contractual agreements with a Chinese company engaging in the Chinese online game industry. Against the breakdown of the cooperation, the founder of the Chinese company launched the arbitration, claiming that the contractual agreements enabled the foreign investor to enter a prohibited industry in China. This argument was supported by the Shanghai CIETAC, which outlawed the involved contractual agreements by referring to the CL as the SPC did in the Chinachem case. However, the special circumstance of this case is that Chinese regulators had already enacted a specific ministerial regulation before the arbitration, clearly denying the legality of foreign investment in the Chinese online game industry via contractual control.Footnote31 Therefore, the involved contractual agreements were deemed invalid and unenforceable. As such, the influence of this individual arbitration has not extended beyond the specific industry in which the VIE structure is disallowed.

3. The Buddha steel case

Unlike the CIETAC arbitration, there is no special ban in the Chinese steel industry. The denial of the VIE usage in the Buddha Steel dispute,Footnote32 however, was explained in another way, ie local protectionism. In this case, Buddha Steel was a Delaware-incorporated company that planned to acquire a Hong Kong company, of which a valuable asset was its VIE control over a China Hebei Province-based company involving the Chinese steel industry. According to Buddha Steel’s filings on the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), it withdrew the submitted IPO application because the Hebei local authority had informed the Hong Kong company that the VIE structure in question ‘contravene[d] current Chinese [regulatory] policies related to foreign-invested enterprises’.Footnote33 However, legal practitioners interpret the denial of VIE usage in this case as a ‘one-off’ event due to local protectionism rather than a regulatory signal of invalidating the VIE structure in the general sense, considering the Chinese custom that a major policy shift is usually steered by the Chinese central authority rather than a local government.Footnote34

4. The Walmart acquisition

The Walmart acquisition of a Chinese e-commerce company was brought before a Chinese central regulator, ie the MOFCOM, for review in 2012.Footnote35 The acquired company operated e-commerce businesses and held a business licence of the Chinese value-added telecommunication service which did not allow over 50 per cent of foreign shareholding. Given that the acquisition would enable Walmart to obtain 51.3 per cent of the equity stake in the acquired company and thus violate the foreign shareholding cap in the value-added telecommunication industry, the MOFCOM approved the acquisition conditional on a restriction, ie the acquisition transaction applied only to the e-commerce business while Walmart was not allowed to use a VIE structure to operate the acquired company’s value-added telecommunication service in China. However, to justify the conditional approval, the MOFCOM did not deny the VIE legality but resorted to the Anti-trust Law of China, addressing that Walmart’s entry into the Chinese value-added telecommunication industry would result in a potential monopoly to distort the market.Footnote36

5. The Yaxing v Ambow Beijing litigation

For a long time, Chinese courts have tried to avoid testing the legality of the VIE structure. Recently, in the lawsuit Yaxing v Ambow BeijingFootnote37 which directly challenged the legitimacy of certain VIE usage, the SPC adopted a seemingly peculiar standpoint.

In this case, the plaintiff Yaxing, a company incorporated under Chinese laws, entered an agreement with Ambow Beijing in 2009 regarding the assignment of one kindergarten and one middle school in China. Ambow Beijing was an operating entity of Ambow Cayman which went public in the US about one year after the assignment agreement was signed. Those Ambow companies employed a VIE structure similar to SINA’s practice. The payment was conducted in terms of cash and Ambow Cayman’s shares. However, Ambow’s share price underwent a sharp decline during the 180 days’ lock-up period, so Yaxing aimed to abolish the assignment agreement to regain control over the assigned educational institutes. Yaxing initiated the litigation, claiming that the Yaxing-Ambow Beijing agreement should be invalidated because the involved educational institutes fell eventually into Ambow Cayman’s control via Ambow’s VIE structure, which constituted ‘illegal goals under the disguise of legitimate forms’.Footnote38 Ambow Beijing defended that the dispute subject was the validity of its assignment agreement with Yaxing rather than the legality of the VIE contractual agreements between the Ambow companies.

The first instance decision supported Ambow’s arguments, and Yaxing appealed to the SPC. Yaxing’s claims put the legality of the VIE structure into the spotlight of judicial review. The SPC upheld the first instance decision but sidestepped to test the legality of the VIE structure. Nevertheless, several significant issues were clarified:

First, the SPC confirmed the legitimacy of the Yaxing-Ambow Beijing Agreement by referring to the CL and the Civil Law of China without taking the Catalogue into account. The SPC explained that the governing laws used therein should be issued by either the National People’s Congress (including its Standing Committee) or the State Council. Since the Catalogue was promulgated at the ministerial level, it was not a legal basis for determining the validity of the Yaxing-Ambow assignment agreement;

Secondly, would the involved VIE usage be legally invalid if it helped foreign capital enter the Chinese educational industry? The SPC referred this issue to the Ministry of Education of China (MOE) and made a ruling according to the MOE’s conclusion. In this case, the VIE structure was not considered illegitimate;

Thirdly, the SPC held that it was not obliged to conclude the legality of the Ambow VIE contractual agreements because it was not the dispute subject of this lawsuit.

As a VIE structure relies heavily on the package of contractual agreements that glue the WFOE with the Chinese operating entity to achieve capital injection in exchange for managerial power and economic benefits, the invalidation of the contractual agreements would lead to the denial of the VIE structure and vice versa. In its ruling, the SPC confined its decision to the specific facts but sidestepped to test the validity of the contractual agreements. As such, the judicial scale tilted neither towards nor away from the recognition of the VIE legality. Moreover, the referral to the MOE released a signal that the legality of certain VIE usage shall be determined by a competent regulator. On these grounds, the SPC pulled itself out of the marsh of testing the VIE legality issue. Although China does not employ a case law legal system, the SPC’s judgments have significant guiding influences on lower courts’ decisions in judicial practice.Footnote39 Therefore, it is highly likely that Chinese courts will adopt a similar measure to settle like disputes thereafter.

From the discussion above, it could be seen that Chinese regulators have put aside the ‘substance rather than form’ principle in handling VIE disputes, and the SPC has dodged to judge the validity of VIE contractual agreements. This standpoint of strategic ambiguity has also been adopted by Chinese authorities in deciding other facets of the VIE legality issue such as the nature of contractual control, as reflected in the law-making process of the FIL.

B. The ambiguous legality of the VIE structure in the Foreign Investment Law of China

In March 2019, the National People’s Congress passed the FIL for enactment in 2020. Having created a general framework for foreign investment in China,Footnote40 the FIL may bring about some positive changes to the Chinese doing-business environment, such as by the formal introduction of pre-entry national treatment (with the Negative List serving as the only exception).Footnote41 Meanwhile, national security review as a regulatory principle is established, reflecting tighter national control.Footnote42 However, the most remarkable changes for the purpose of this article may not lie in the new law itself but rather the differences between the enacted version and a more detailed 2015 draft version (2015 Draft) regarding the VIE legality issue, which may reflect China’s strategic policy.

First of all, the 2015 Draft defined foreign investors. According to the 2015 Draft, foreign investors comprised ‘(i) natural persons without Chinese nationality; (ii) companies incorporated under the laws of countries or regions other than China; (iii) the governments of countries or regions other than China and the departments or agencies thereunder; (iv) international organizations’.Footnote43 Correspondingly, ‘(i) persons with Chinese nationality; (ii) Chinese governments and subordinate departments or institutes; (iii) Chinese companies under the control of either (i) or (ii)’ were defined as Chinese investors.Footnote44 Besides the nationality requirement for individuals and the incorporation criterion for legal persons, the 2015 Draft also employed an actual control test, stating ‘Chinese companies under the control of foreign investors are regarded as foreign investors’.Footnote45 Moreover, control was interpreted broadly, covering not only over 50 per cent of shareholding, equity stake, voting power and like rights and interests but also other forms of decisive controlling power, including contractual control.Footnote46 Thus, according to the 2015 Draft, the Cayman-based listed company, the Hong Kong conduit company, and the WFOE within a VIE structure would be treated as foreign investors.Footnote47

More importantly, the 2015 Draft clearly defined contractual control as a form of foreign investment.Footnote48 Besides, it stipulated that ‘if a company incorporated according to the laws of a foreign country or region is under the actual control of Chinese investors, upon application and approval, this company’s investment in a restricted industry in China could be regarded as investment conducted by Chinese investors.’Footnote49 Combined with the definition of foreign investors, these stipulations could essentially have cleared the vagueness surrounding the VIE legality issue. As the Cayman-based company within a VIE structure is under both Chinese and foreign ownership, the VIE usage to achieve contractual control over the Chinese operating entity in a prohibited industry would be a form of foreign investment, which would be illegal. Whereas in restricted industries, the legality of involved VIE structures would depend on whether the Cayman-based company was under the actual control of Chinese investors or not. If the Cayman-based company was controlled actually in Chinese hands, involved VIE usage to achieve contractual control could be treated as investment conducted by Chinese investors and thus would be legitimate.

However, the stipulations regarding foreign investors, actual control and the nature of contractual control proposed in the 2015 Draft were removed thoroughly in the FIL. Instead, the FIL defines foreign investment as ‘the investment activities conducted by foreign investors either directly or indirectly in China, including ‘ … (ii) acquiring shares, equity, property interests and other similar interests in Chinese companies; … (iv) other forms of investment prescribed by Chinese laws, administrative regulations or the State Council’.Footnote50 Yet, the key items ‘indirect investment activities’, ‘similar interests’ and ‘other forms of investment’ are not further defined in either the FIL or its ancillary rules. Thus, the core legal issue of the VIE structure, ie whether contractual control is a form of foreign investment or not, remains unclear.

From the law-making process of the FIL, it could be seen that Chinese authorities are still reluctant to clarify the VIE legality issue. Against this backdrop, the achievement of the first domestic VIE listing on the SSE STAR Board has become more spotlight-catching, which is the subject matter that the following subsection examines.

C. The achievement of the first VIE listing on the SSE STAR Board

Although China’s investment regulation on VIE usage in offshore fundraising has employed an ambiguous standpoint, Chinese capital markets have banned VIE companies from going public domestically. The prohibition has, on the one hand, revealed that Chinese authorities do not recognize the legality of the VIE structure. On the other hand, it has pushed hundreds of Chinese VIE issuers including many business giants to float overseas, predominantly in the US (e.g. Alibaba) and Hong Kong (e.g. Tencent), which has largely undermined the competitiveness of domestic capital markets. Against the increasingly intensified Sino-US market competition, Chinese capital markets may have been keen to accommodate the listing needs of Chinese VIE companies. This is the background against which moves by Chinese authorities to establish the SSE STAR Board in mid-2019 with a permissive policy of VIE listings are to be considered.

The STAR Board listing rules do not admit VIE listings directly but employ another notion, namely, red-chip companies. Red-chip companies are officially defined as companies incorporated overseas but with their main business operation in China.Footnote51 Subsequent rules interpret ‘business operation’ to include that through contractual control.Footnote52 As such, the Cayman-incorporated company within a VIE structure is a subset of red-chip companies. That is to say, the establishment of the STAR Board has provided a landing zone that can accommodate the listing needs of Chinese VIE issuers. However, these rules do not endorse the legality of the VIE structure in the general sense. For VIE issuers that are not involved in prohibited/restricted industries, the establishment of the STAR Board no doubt set a red-letter day because they are provided with a new listing venue other than the Hong Kong and US stock exchanges. For VIE usage in prohibited/restricted industries, however, whether there would be a blanket denial, a blanket approval, or a selective approval on VIE listing remains uncertain. Nevertheless, the STAR Board accommodated the first VIE issuer in October 2020, thus providing some policy hints.

The first Chinese VIE issuer is Ninebot (stock code: 689009) that employs a Sina-style VIE structure with its listed entity established in Cayman and operating entity incorporated in China. Despite its main business of producing and selling electronic scooters and robotics, Ninebot’s operating entity also holds a Chinese value-added telecommunication business licence which does not allow Ninebot to exceed 50 per cent of foreign shareholding. In the post-IPO stage, Ninebot’s two Chinese co-founders hold only 25.79 per cent of the equity stake, who nevertheless have 63.47 per cent of the total voting power with actual control over Ninebot, thanks to the use of a dual-class share structure (DCSS).Footnote53

In this case, Chinese regulators were cautious about granting the first VIE listing clearance. According to the SSE rules, the maximum time cost of going public on the STAR Board is six months in principle.Footnote54 However, Ninebot’s listing application was submitted on 17 April 2019, suspended on 12 May 2019, resumed on 13 August 2019, and reviewed by the SSE Listing Committee on 12 June 2020. Eventually, the long-awaited first VIE listing was achieved on 29 October 2020, 18 months after the submission of its listing application. Despite twists and turns, Ninebot’s VIE listing has set a milestone, which has revealed that Chinese regulators have not conducted a blanket denial on the legality of VIE usage in restricted industries.

However, whether the first VIE listing implies a blanket acceptance or selective approval of VIE usage in restricted industries is yet to be seen. If it is the latter – which means that Chinese authorities maintain regulatory flexibility to cherry-pick VIE issuers –, the conjecture may prompt another concern, ie what is the benchmark used in reality for deciding the eligibility or suitableness of VIE listings?

As discussed above, the 2015 Draft proposed an actual control test, treating an overseas company’s investment in a restricted industry as investment conducted by Chinese investors, provided the overseas company was under the actual control of Chinese investors. Despite being removed in the FIL, the actual control test seems to have survived in reality, considering that in the Ninebot case, the Chinese co-founders’ de facto control over the Cayman-based company may have made the involved VIE structure recognized by Chinese regulators to grant the listing admission. If so, a further implication would be that corporate founders who hold shares in the Cayman-based company within a VIE structure would need to maintain their Chinese citizenship to ensure actual control in Chinese hands. Moreover, as equity financing can lead to shareholding dilution, control-enhancing instruments, typically the DCSS, would be more attractive to corporate founders who would otherwise not be able to maintain control post listing. The fact that the DCSS has been introduced hand in hand with VIE listing on the STAR Board may serve as a clue of the above surmises. Yet, without an official say, regulatory uncertainties remain.

From the discussion above, it could be seen that Chinese authorities have maintained the vagueness of the VIE legality on various occasions, and the recent regulatory practice has continued to keep the strategic ambiguity. The following subsection turns to discuss the ambiguous legality of the VIE structure behind the scenes.

D. The ambiguous legality of the VIE structure behind the scenes

In the early days before the promulgation of the Catalogue, China conducted case-by-case scrutiny on foreign investment, which gave Chinese regulators considerable flexibility to either permit or deny certain inward investment projects. The implementation of the Catalogue has fixed and visualized the eligibility of foreign investment, which meant that Chinese authorities have been more constrained. On the one hand, due to the accession to the WTO with the membership obligation of domestic market openness, China had to remove many barriers to market entry, thereby making some industries accessible to foreign investors regardless of its own taste. On the other hand, the updates of the Catalogue may not always keep pace with economic needs. Therefore, the weakened flexibility may result in a dilemma that where a favourite investment project involving a prohibited industry applies for market clearance, it leaves little legal space for Chinese authorities to open a side door.

However, it seems that the legal ambiguity of the VIE structure can mitigate the problems mentioned above. The VIE structure was initially designed in 2000 by a Chinese securities lawyer, a former government official with a deep understanding of Chinese policies besides his legal expertise.Footnote55 Given that China joined the WTO in 2001, a time point close to the creation of the VIE structure, it is hard to say the VIE structure did not reflect the Chinese central authority’s concern about the negative impact of joining the WTO on investment regulation. In fact, SINA obtained sufficient ‘unofficial comfort’ from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China (MIIT) prior to its US VIE listing.Footnote56 The MIIT was the central regulator of the industry that SINA’s main business engaged in. The endorsement granted by the MIIT seemed to open Pandora’s box. Since then, many Chinese enterprises involving foreign investment-prohibited/restricted industries have begun to conduct offshore fundraising via VIE usage.

To date, Chinese regulators have not outlawed the VIE structure in the general sense. However, the official silence does not mean an implied recognition. Instead, in light of the CL, Chinese authorities can nullify the package of contractual agreements to invalidate a certain VIE structure at any time. It appears that Chinese authorities have blurred the legal status of the VIE structure purposefully.Footnote57 On the one hand, the official silence can induce a broad use of VIE structures to funnel foreign investment into prohibited/restricted industries, which can largely offset the negative impact of the weakened regulatory flexibility so as not to miss favourite investment projects. On the other hand, once unfavourite access is identified, Chinese authorities preserve the force to dissolve certain VIE usage at will.Footnote58 On these grounds, opening the door to foreign investment as broadly as possible while holding the power to close it discretionarily seems to be a pragmatic approach to reap the economic benefits of foreign investment without bearing the downsides of sacrificing sovereignty in return.Footnote59 Thus, China’s regulation on the VIE structure evolves in line with the constant national policy regarding foreign investment that is based on a ‘target, “interests” approach’ to promote economic development while limiting the influence of foreign investors.Footnote60

Some scholars analyse the Chinese standpoint by using a sheep-shearing explanation.Footnote61 Their empirical analysis discovers that compared to non-VIE counterparts, Chinese VIE companies have created a higher level of excess employment for social stability and made larger donations in natural disasters.Footnote62 In their opinion, Chinese authorities have blurred the legality of the VIE structure intentionally to use it as the Sword of Damocles hanging over Chinese VIE companies so that the economic risks of the invalidation of the VIE structure can drive involved companies to follow Chinese authorities’ instructions meekly.

In addition to the reasons given above, were the legality of the VIE structure to be denied in the general sense, how to handle existing VIE users in prohibited/restricted industries, in particular those business giants listed in the US or Hong Kong, would become a tough problem with potential negative influence on economic development. Therefore, from the standpoint of Chinese authorities, the blanket denial of the VIE structure would not be an economically wise decision.

However, it would be even worse if Chinese authorities were to recognize the legality of the VIE structure in the general sense. If so, the Chinese pre-entry sovereign regulation on foreign investment would be legally bypassed with the Catalogue and then the Negative List becoming guidance to inform foreign investors in which industries shall the VIE structure be employed.

Thus, although the VIE structure was created by market players, its survival and expansion for two decades should be attributed to the Chinese regulatory policy. Through the strategic ambiguity of the VIE legality, Chinese companies have raised desired foreign capital to expand their businesses while Chinese authorities have retained regulatory flexibility to leverage economic development. Nevertheless, the legal uncertainties of the VIE structure may cause huge risks to foreign investors.

IV. The legal risks of Chinese variable interest entity structures to foreign investors

A. Regulatory risks: no effective legal remedy against invalidation

As discussed above, Chinese authorities can outlaw the involved contractual agreements in light of the CL to invalidate a VIE structure. The invalidation is likely to cause a mandatory reorganization to expel foreign control and/or a withdrawal of the business licence granted to the Chinese operating entity, which may constitute indirect expropriation. Yet, there is little likelihood that Chinese authorities would grant reasonable compensation. Against the legal ambiguity of the VIE structure, where an invalidation takes place, affected foreign investors could hardly receive effective recourses at both national and international levels.

A Chinese authority’s decision to negate a certain VIE structure would not be expected to lead to either a local administrative or judicial remedy in favour of foreign investors against the invalidation. On exhaustion of local remedies, it is unlikely that foreign investors could secure effective international recourse due largely to potential jurisdictional hurdles.

In the post-colonial era, international arbitral tribunals obtain jurisdiction regarding investment disputes mainly from international investment agreements (IIAs)Footnote63 subject to a precondition, ie it is an investment dispute between a foreign investor and the host state.Footnote64 The question that follows, therefore, is how to determine the foreignness of the involved investor as an essential standing of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).Footnote65 An investor recognized in an ISDS means either a natural person or a legal person foreign to the host state.Footnote66 China’s national law does not recognize dual nationality for Chinese nationals.Footnote67 This nationality criterion for individuals is also employed in Sino-foreign IIAs.Footnote68 Thus, as the Chinese operating entity within a VIE structure is wholly owned by shareholders with Chinese nationality for acquiring market clearance, those shareholders are not eligible to launch an investor-state arbitration (ISA).

The aforesaid nationality requirement may prompt a concern, ie would the shareholders of the operating entity be qualified to initiate an ISA if they were to change their Chinese nationality to a foreign country? In fact, the 2015 Draft touched on this issue by stipulating that ‘where a Chinese national acquires foreign nationality, his investment in China would be regarded as foreign investment regardless of whether the nationality change takes place before or after the entry into force of the law.Footnote69 Thus, in light of the 2015 Draft, nationality change would likely entitle involved shareholders of the operating entity within a VIE structure to launch an ISA against the invalidation. However, the stipulation above was removed in the FIL, thus leaving the issue unclear.

Nevertheless, Chinese IIAs widely adopt an admission clause,Footnote70 which states that China only admits investment of the other contracting party in conformity with Chinese laws.Footnote71 In the event of a breach of the admission clause, a tribunal is likely to declare the lack of jurisdiction.Footnote72 Even if a dispute is accepted for resolution, in light of the well-established principle that treaty-based recourses are not available to market access through the circumvention of local statutes, the arbitration would be unlikely to support the involved investor’s claim.Footnote73

The eligibility of the WFOE and its overseas parent company to initiate an ISA against the invalidation is more complicated because they are corporate entities. Worldwide, there is no uniform baseline for defining corporate nationality even though the incorporation theoryFootnote74 and the real seat doctrineFootnote75 enjoy the greatest popularity. However, both principles may restrict the protection of foreign investors, given that investment projects are widely required to use locally-incorporated vehicles such as WFOEs or EJVs, which are classified as companies of the host state. Therefore, in the international investment regime, the definition of foreign investors does not always overlap with corporate nationality but may extend to comprise actual control and substantial interests, treating the foreign shareholders of a locally-incorporated company as foreign investors, like stated in the ICSID Convention that ‘[n]ational of another Contracting State means … because of foreign control, the parties have agreed should be treated as a national of another Contracting State … ’.Footnote76 Moreover, control can be interpreted broadly to comprise not only equity interests but also the ability to exercise substantial influence over the management and operation of the investment.Footnote77

As stated above, China adopts the incorporation theory in the Company Law to decide corporate nationality, whereas the 2015 Draft proposed to introduce an actual control test, under which the WFOE and its overseas parent companies within a VIE structure would be regarded as foreign investors. However, the actual control test was not adopted in the FIL. At the international level, China adopts different criteria, including incorporation,Footnote78 real seat,Footnote79 incorporation plus actual control,Footnote80 real seat plus actual controlFootnote81 in the over 100 BITs it has concluded. Due to the diversity of the BITs, it is fairly difficult to analyse the foreignness of either a WFOE or its overseas parent company to China as a necessary standing of ISDS on a state-by-state basis. However, to say the least, the afore-discussed ‘admission clause’ in China-signed IIAs may serve as a solid jurisdictional barrier that prevents the involved companies under a VIE structure from getting their claims supported in an ISDS.

Even more complex disputes could arise. For instance, where a guarantee scheme exists between an investment project and its home state, whether the home state could get relevant subrogation to initiate an arbitration against the invalidation is unclear.Footnote82 On these grounds, VIE usage may lead to regulatory risks with considerable uncertainties that are overall detrimental to foreign investors.

B. Agency problems: digression of the Chinese operating entity

Apart from regulatory risks, there may also be agency problems. Within a VIE structure, once capital is injected into the operating entity, the value of the Cayman-incorporated company and associated conduit companies would diminish hugely. As such, the effective operation of the VIE structure relies heavily on the integrity of the shareholder of the operating entity as a key person.Footnote83 However, the shareholder may pursue his private agenda at the cost of the operating entity’s best interests, generating agency risks to foreign investors. To make matters worse, the ambiguous legality of the VIE structure makes the enforceability of involved contractual agreements unclear in China, which may render the potential risks even more severe than the traditional manager-shareholder agency conflicts.Footnote84 In practice, such agency problems have already taken place in capital markets.

1. The Alipay event

The 2011 Alipay Event may be the most notable instance of the VIE digression problem.Footnote85 Alibaba employed a typical VIE structure with Alipay served as a subsidiary of the Alibaba operating entity in China. Out of the concern that Alibaba’s foreign shareholding might impede Alipay to obtain a third-party online payment business licence from a competent Chinese regulator, Jack Ma (the founder of Alibaba) separated Alipay from Alibaba to be an independent company under his name even without informing the largest two shareholders of Alibaba, ie Softbank and Yahoo which collectively held over 70 per cent of Alibaba’s shares at that time. When Yahoo discovered the fact and conducted disclosure on the SEC, its stock price dropped 9.8 per cent sharply.Footnote86

2. The new oriental education reorganization

Since the Alipay Event, capital markets have become vigilant to VIE rearrangement.Footnote87 In the New Oriental Education (EDU) reorganization event,Footnote88 EDU was a US-listed Chinese company with its operating entity initially held by 11 employees, including the founding shareholder Michael Yu. In December 2011, Yu began to restructure the operating entity and expelled nine shareholders to concentrate all the voting power in his hands. Even though Yu did not take any further action, the VIE rearrangement attracted significant attention from the SEC which conducted a series of follow-on investigations.Footnote89

Within a VIE structure, companies at the four tiers are all incorporated under the name of the corporate founder in most cases. Occasionally, the China-based operating entity may be incorporated under the name of a person trusted by the founder, such as where the founder does not hold Chinese nationality. Under the latter circumstance, there may be an extra risk that the shareholder of the operating entity may unilaterally abrogate the VIE agreements to pursue private interests,Footnote90 causing serious troubles to corporate performance to damage the economic interests of foreign investors.

3. The ChinaCast dispute

ChinaCast (CAST) was a US-listed VIE company engaging in the Chinese educational industry. After losing positions, the shareholders of the operating entity took away the financial chops, withdrew most of the cash of CAST, and transferred the interests of the operating entity to an unrelated third party. Finally, CAST was delisted to the Over the Counter Bulletin Board (OTCBB) after a huge decline in market capitalization.

As the enforceability of the package of VIE contractual agreements is uncertain in light of Chinese laws, the digression risk may arise an assumption, i.e. the feasibility of installing arbitration clauses in the contractual agreements to confer jurisdiction on either a Chinese or international arbitral institution with foreign governing laws for legal recourse. To date, no such scenario has occurred in practice to test the hypothesis. However, the 2015 Draft proposed a provision, stating that ‘[i]nvestment agreements signed by foreign investors for implementation in China should be governed by Chinese laws.’Footnote91 This stipulation would make the hypothesis above come to a dead end, which was nevertheless not adopted in the FIL. However, the STAR Board rules provide a negative answer to the hypothesis by requiring VIE issuers to sign a declaration to be bound to the jurisdiction of Chinese courts and use Chinese laws as governing laws for dispute settlement.Footnote92 Even for private VIE companies, success of the hypothesis seems elusive. As the objects of the VIE contractual agreements are based in China, judicial recognition by Chinese courts is crucial to the enforcement of a foreign arbitral decision.Footnote93 Since Chinese authorities have blurred the legality of the VIE structure as a strategic policy, it is not convincing that an arbitration award with foreign governing laws to clarify the validity of certain VIE contractual agreements would be recognized by Chinese courts.

Apart from regulatory risks and agency problems, the VIE structure also contains economic risks to foreign investors. As discussed above, the VIE structure relies considerably on the transferability of economic benefits – which is the source of dividends to foreign investors – from the operating entity to the Cayman-based listed entity via the Hong Kong conduit company and the WFOE. In practice, however, material transfer of economic benefits is rarely conducted, resulting in one-way capital flow. According to Chinese laws and regulations, if economic benefits generated in China are used as reinvestment rather than repatriation, foreign investors can enjoy favourable treatment in taxation, finance and land use,Footnote94 which provides an excuse for no dividends.Footnote95 Moreover, cross-border transfer of economic benefits involves China’s control over capital outflow,Footnote96 which also defends the fact that foreign capital is injected into the operating entity, but the reverse capital flow is rarely conducted,Footnote97 as stated by JD.Com (the third-largest Chinese e-commerce company) that ‘we do not have any present plan to pay any cash dividends on our ordinary shares in the foreseeable future’.Footnote98

It is not convincing to say that sophisticated pre-IPO foreign investors, typically venture capital funds, overlook the VIE risks, in particular, given that Chinese VIE structures have existed for two decades. However, since Chinese authorities have seldom overridden VIE structures, pre-IPO foreign investors seem to consider the palpable VIE risks are ‘worth bearing’ for potential returns.Footnote99 For instance, in 2005, Yahoo invested USD one billion in Alibaba in exchange for 40 per cent of the equity ownership.Footnote100 During Alibaba’s IPO in 2014, Yahoo sold 4.9 per cent of the shares and received approximately USD eight billion, besides its then rest shareholding with a market valuation of over USD 27 billion.Footnote101 Therefore, from the standpoint of pre-IPO foreign investors, potential economic returns may far outweigh the legal risks of the VIE structure. However, post-IPO foreign investors buying into VIE listed issuers can only rely on share price rise to get investment returns and post-event remedies, e.g. a securities class action, to claim compensation against market misbehaviours.

In recognition of the legal risks, capital market participants try to mitigate potential VIE troubles by diversifying the shareholding of the operating entity to ease the single-handed control risk.Footnote102 Moreover, a stock incentive scheme is often employed to grant some shares of the Cayman-based listed entity to the shareholders of the operating entity, thereby partly bundling their interests with the success of the listed entity to counteract the digression risk.Footnote103 Also, the watchdogs of global capital markets react to the VIE risks, which is the theme of the following section.

V. The regulatory reaction of global capital markets to Chinese variable interest entity structures

Given that the US and Hong Kong stock exchanges are the main listing venues of Chinese VIE companies, the US and Hong Kong practices will be examined in this section to roughly represent the whole picture.

A. The regulatory reaction of the US capital markets

Investor protection stays central to securities regulation in the US. In recognition of the legal risks of Chinese VIE structures, the SEC has reacted to enhance investor protection.Footnote104 After the Shanghai CIETAC arbitration, the SEC required Baidu, a NASDAQ-listed Chinese VIE company, to demonstrate the actual owner of its operating entity and disclose its formal and informal dialogues with Chinese regulators regarding the legality of its VIE structure.Footnote105 After the EDU reorganization, the SEC initiated a series of investigations to examine whether the financial results of EDU’s Chinese operating entity were consolidated appropriately or not.Footnote106 In reaction to the battle for control of CAST, the SEC, coupled with the NASDAQ, suspended the trading of CAST’s stocks and then delisted CAST to the OTCBB plus an extra investigation into the control dispute.Footnote107

As Didi’s US VIE flotation has triggered Chinese authorities to tighten the control over Chinese companies’ future US listings, most recently, the SEC reacted by enhancing disclosure obligation to ensure that investors can make informed decisions, which required prospective Chinese VIE issuers to (i) remind investors that they would buy into a Cayman-based shell company rather than a China-based operating entity, and distinguish the description of the shell company’s management services from that of the Chinese operating entity; (ii) bring the VIE risks to investors’ attention that Chinese authorities’ future actions may impinge significantly on the China-based operating entities’ financial performance and the enforceability of involved contractual arrangements; (iii) disclose detailed financial information to help investors understand the financial relationship between the operating entity and the issuer.Footnote108

B. The regulatory reaction of the Hong Kong capital markets

Likewise, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) monitors the VIE risks closely and makes timely regulatory responses. Since 2005, the HKEX has employed a disclosure-based approach to review VIE IPO applications, requiring due disclosure of VIE risks and the compliance status of relevant contractual agreements.Footnote109 After the Alipay VIE event, the HKEX revised its rules in 2011 to grant listing approval conditional on the necessity of VIE usage on the basis of a case-by-case review.Footnote110 In detail, the HKEX mandated VIE IPO applicants to provide reasons for VIE usage, insert arbitration clauses with corresponding judicial support, and provide a Power of Attorney whereby the shareholder of the involved operating entity grants all the voting and managerial rights to the listed entity.Footnote111 Subsequent amendments in 2012 further required the disclosure of conflict of interests, economic risks, tax and regulatory risks of the listed entity, the preparation for key-person accidents like death or divorce, and the legal bases of the effectiveness of contractual control.Footnote112 In response to the Shanghai CIETAC arbitration, the HKEX revised its rules in 2013 to require the shareholder of the VIE operating entity to provide a confirmation letter – which should be issued by the company’s legal counsel – regarding the legitimacy of the involved VIE structure. Moreover, the shareholder of the VIE operating entity must disclose any consideration he/she receives if the listing applicants aim to terminate the contractual agreements.Footnote113 Also, the profits of the VIE operating entity should be disclosed separately where possible.Footnote114 After the issuance of the 2015 Draft, the HKEX added more disclosure requirements in 2018, asking VIE IPO applicants to disclose potential risks related to the Chinese legal reform.Footnote115

Nevertheless, no matter how elaborate the disclosure obligation is, the VIE structure is legally problematic because it functions by facilitating foreign investors to access prohibited/restricted industries, which may contravene China’s regulation on foreign investment and thus be invalidated as ‘illegal goals under the disguise of legitimate forms’ according to the CL. The final say, however, remains in Chinese authorities. As long as Chinese authorities maintain the strategic ambiguity of the VIE legality, uncertainties and risks remain for foreign investors.

VI. The future of Chinese variable interest entity structures

The VIE legality issue involves not only Chinese companies’ VIE usage in offshore financing but also overseas listing. The latter is the subject matter of this section. Over recent years, Chinese authorities have tightened the national control over domestic companies’ overseas listings, exemplified typically by the regulatory response to Didi’s US flotation in mid-2021.

As China’s equivalent to Uber, Didi is a VIE user with its Cayman-incorporated company serving as the listed shell and China-based operating entity engaging in the Chinese ride-hailing industry. After Didi’s US IPO, the founders hold only 9.9 per cent of the equity ownership, but they have 57.3 per cent of the total voting power through holding superior voting shares with ten votes per share under the DCSS in use.Footnote116 As such, in light of Ninebot’s domestic VIE listing, Didi may have been an eligible issuer on the SSE STAR Board. However, Didi chose the US as its listing destination without informing Chinese regulators beforehand. Out of the concern that Didi’s US flotation under the SEC’s information disclosure requirements may have caused harm to China’s national data security, Chinese authorities launched a cyber-security investigation immediately after Didi’s IPO.Footnote117 As a result, Didi’s share price plummeted, and affected US investors initiated a securities class action for compensation.Footnote118

The Didi event has shaped the market regulation both in China and the US. The Cyberspace Administration of China has revised the Measure for Cyber-security Review to mandate any Chinese issuer seeking to go public overseas to pre-pass China’s national cyber-security review, as long as the issuer has the personal information of over one million Chinese users.Footnote119 Given the sizeable Chinese population, the criterion of one million users is not a high threshold to target many Chinese VIE companies’ potential overseas listings as the subjects of national cyber-security review. On the other side, in response to China’s intensified regulation on Chinese companies’ future overseas listings, the SEC has decided not to allow any China-based operating company to float in the US unless it conducts due disclosure regarding whether the proposed US listing has received pre-consent or denial from competent Chinese authorities.Footnote120

Thus, against Didi’s US flotation as a trigger, Chinese authorities’ regulatory response in terms of the ex-post investigation and legal revision effort has undoubtedly released a strong policy signal towards tighter control over Chinese issuers’ future overseas listings. As a result, for prospective Chinese VIE issuers aiming to avoid regulatory uncertainties and associated risks, their enthusiasm for overseas listings is likely to fade. Instead, against the establishment of the SSE STAR Board as a new landing zone, China’s tightened control may serve as a powerful driving force to retain some Chinese VIE issuers in domestic capital markets, a regulatory outcome perhaps Chinese authorities would like to see.

VII. Conclusion

The VIE structure has been used widely by Chinese companies to raise foreign capital in prohibited/restricted industries, which is nevertheless legally problematic and may be invalidated. Over the years, however, cases such as Yaxing v Ambow Beijing have repeatedly revealed that Chinese authorities are reluctant to either confirm or outlaw the VIE legality in the general sense.

Most recently, the 2015 Draft proposed some remarkable stipulations that could clarify the VIE legality issue. However, those stipulations were removed in the 2020 enacted version of the FIL, thus further aggravating regulatory uncertainties. Afterwards, the SSE STAR Board accommodated the long-awaited first domestic VIE listing in October 2020, but this did not endorse the VIE legality in the general sense. As such, China’s recent regulatory practice has continued to keep the VIE legality ambiguous.

The strategic ambiguity of the VIE legality can help Chinese authorities maintain regulatory flexibility to leverage economic development but with legal risks to foreign investors. In the event of invalidation, foreign investors would face a dilemma of lacking effective remedies at both local and international levels. Besides, agency problems have occurred a couple of times in capital markets. Although the US and Hong Kong regulators have placed higher reliance on ex-post investigation and ex-ante disclosure to reinforce investor protection, risks remain to foreign investors as long as Chinese authorities keep the VIE legality ambiguous.

Notwithstanding China’s investment regulation on VIE usage in offshore fundraising has witnessed limited changes, against Didi’s recent US flotation as a trigger, China’s national control over domestic companies’ overseas listings has been tightening, which may help retain Chinese VIE issuers in domestic capital markets in the future.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully appreciates the insightful comments from the three anonymous referees and owes thanks also to Eilís Ferran, Markus Gehring and Elizabeth Howell for their comments on an early version of this article. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China, Explanatory Note on the Foreign Investment Law of China (Draft) (全国人大常委会, 关于《中华人民共和国外商投资法 ( 草案 ) 》的说明).

2 In practice, the VIE structure has also been used in encouraged industries by Chinese entrepreneurs who have considered that the expansion of their business territory may later touch on prohibited/restricted industries. Unless otherwise stated, the research scope of this article is the use of the VIE structure in prohibited/restricted industries.

3 See, e.g. the 2004 Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries, <https://english.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/policyrelease/gazette/200505/20050500093692.html>. Unless otherwise stated, all URLs were last accessed on 5 September 2021.

4 E.g. there were 35 restricted industies in the 2017 Catalogue, of these, 26 industries set a cap of foreign shareholding.

5 In the Chinese legal parlance, the Negative List is also referred as ‘Special Administrative Measure for the Access of Foreign Investment’.

6 Paul Gillis and Michelle René Lowry, ‘Son of Enron: Investors Weigh the Risks of Chinese Variable Interest Entities’ (2014) 26 Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 61, 61.

7 Yu-Hsin Lin and Thomsa Mehaffy, ‘Open Sesame: The Myth of Alibaba’s Extreme Corporate Governance and Control’ (2016) 10 Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law 437, 438.

8 Thomas Y Man, ‘Policy Above Law: VIE and Foreign Investment Regulation in China’ (2015) 3 Peking University Transnational Law Review 215, 216.

9 Information is drawn from SINA’s 2019 Annual Report filed on the SEC on 29 April 2020, <https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/0001094005/000110465920052758/sina-20191231x20f.htm>.

10 Justin Hopkins, Mark Lang and Donny Zhao, ‘The Rise of US-Listed VIEs from China: Balancing State Control and Access to Foreign Capital’ (2018) Darden Business School Working Paper No 3119912, 9–10 <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3119912>.

11 Ibid, 1.

12 Gillis and Lowry (n 6) 62.

13 Lin and Mehaffy (n 7) 445.

14 This article uses SINA’s VIE structure to demonstrate the rationale of contractual agreements.

15 In practice, the WFOE usually holds a business consultancy licence with the operating entity serving as its only customer, see Li Guo, ‘Chinese Style VIEs: Continuing to Sneak under Smog?’ (2014) 47 Cornell International Law Journal 569, 577.

16 Enterprise Income Tax Law of China (中华人民共和国企业所得税法), Arts 2(1)(3), 3(2)(3), 4(2) and 27(5); Regulation for the Implementation of the Enterprise Income Tax Law of China (中华人民共和国企业所得税法实施条例), Art 91.

17 Arrangement between China and Hong Kong on the Avoidance of Double Taxation and Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income (China-Hong Kong Taxation Arrangement) (内地和香港特别行政区关于对所得避免双重征税和防止偷漏税的安排), Art 10(2). In practice, the applicable tax rate of cross-border transfer of economic benefits is disputable. The Chinese taxation regulator issued a ministerial regulation in 2009, denying the role of a conduit company as the beneficial owner to enjoy the preferential tax rate, see State Administration of Taxation of China, Notice of the State Administration of Taxation on Interpretation and Recognition of ‘Beneficial Owners’ under Tax Agreements [2009] No 601 (国家税务总局, 关于如何理解和认定税收协定中“受益所有人”的通知, [2019] 第601号), Art 1. However, a VIE user could claim its Hong Kong tier as the principal executive office rather than a conduit company to argue for the preferential tax rate, see, e.g. Alibaba claimed that its Hong Kong company served as the principal executive office and thus applied for the 5% tax rate in its cross-border transfer of economic benefits, see Alibaba’s 2020 Annual Report filed on the SEC on 27 July 2021, <https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/1577552/000110465921096092/baba-20210331x20f.htm>.

18 China-Hong Kong Taxation Arrangement, Art 10(2).

19 Creative compliance means compiance in letter rather than spirit, in form rather than substance, thereby being technically complied with the law compared to an outright breach. See Shen Wei, ‘Will the Door Open Wider in the Aftermath of Alibaba? – Placing (or Misplacing) Foreign Investment in A Chinese Public Law Frame’ (2012) 42 Hong Kong Law Journal 561, 565.

20 Gillis and Lowry (n 6) 63.

21 Hopkins, Lang and Zhao (n 10) 1.

22 When the China-China-Foreign structure was created, the Chinese telecommunication industry was closed to foreign investment. Due to China accession to the WTO, the Chinese telecommunication industry has been opened up to foreign investment nevertheless with a cap of foreign shareholding. According to the 2020 Negative List, companies engaging in value-added telecommunication businesses in China should not exceed 50% of foreign shareholding, and companies provided basic telecommunication services must be controlled by Chinese investors.

23 The Chinese-Chinese-Foreign structure is summarized from Scott Yunxiang Guan, ‘China’s Telecommunications Reforms: From Monopoly Towards Competition’, in Frank Columbus (ed), Asian Economic and Political Issues (Nova Science Publishers 2004) 11.

24 China’s national law employs the incorporation theory to decide corporate nationality, under which, Chinese companies are defined as those incorporated in China according to the Company Law of China, see Company Law of China (中华人民共和国公司法), Art 2.

25 See Neil Gough, ‘In China, Concern about a Chill on Foreign Investments’ New York Times (2 June 2013) <https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/06/02/in-china-concern-of-a-chill-on-foreign-investments/?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=5D433987A6C914CC9A3DEC3F3F637928&gwt=pay>.

26 Contract Law of China (中华人民共和国合同法), Art 52(3) (‘A contract is invalid under any of the following circumstances: … there is an attempt to conceal illegal goals under the disguise of legitimate forms’). Although the Contract Law of China has expired due to the enactment of the Civil Code of China, for the purpose of this article, the author uses the stipulation of the Contract Law of China to support the arguments.

27 Chinachem v China SME, Supreme People’s Court of China [2002] Civil Final Judgment No 30 (最高人民法院民事判决书 [2002]民四终字第30号).

28 Lin and Mehaffy (n 7) 469.

29 The core entitlement of equity ownership is twofold, ie economic interests and voting power, see Steven R Cox and Dianne M Roden, ‘The Source of Value of Voting Rights and Related Dividend Promises’ (2002) 8 Journal of Corporate Finance 337, 337.

30 See Kenneth Kong and Shelly Sui, ‘Shanghai CIETAC’s Finding on VIE Case Raises Plenty of Questions’ (21 December 2012) <https://www.vantageasia.com/shanghai-cietacs-finding-on-vie-case-raises-plenty-of-questions/>.

31 General Administration of Press and Publication of China et al, Notice for Public Sector Reform and Further Strengthening the Administration of the Pre-approval of Online Games and Examination and Approval of Imported Online Games (新闻出版总署, 国家版权局, 全国“扫黄打非”工作小组办公室关于贯彻落实国务院《“三定”规定》和中央编办有关解释, 进一步加强网络游戏前置审批和进口网络游戏审批管理的通知), Art 4.

32 For an introduction of the Buddha Steel case, see Dan Harris, ‘Variable Interest Entities (VIE) In China. What would the Buddha (Steel) Say?’ (7 April 2011) <https://www.chinalawblog.com/2011/04/variable_interest_entities_vie_in_china_what_would_the_buddha_steel_say.html>.

33 See Buddha Steel’s 8-K Form filed on the SEC on 28 March 2011, <https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1367777/000114420411017680/v216334_8k.htm>.

34 Thomas M Shoesmith, ‘PRC Challenge to Variable Interest Entity Structures?’ Pillsbury (31 March 2021), 2 <https://www.pillsburylaw.com/images/content/3/5/v2/3571/ChinaAlertPRCChallengetoVIEStructures-03-31-11pdf.pdf>.

35 See Reuters, ‘Wal-Mart Gets Restricted Approval to Raise Stake in China E-commerce Firm’ (14 August 2012) <https://in.reuters.com/article/walmart-china-idINL4E8JE2VK20120814>.

36 Ministry of Commerce of China, Announcement of conditional approval of Walmart’s anti-monopoly review decision on the acquisition of 33.6% of equity stake in Niuhai Holdings [2012] No 49 (中华人民共和国商务部, 公布附加限制性条件批准沃尔玛公司收购纽海控股 33.6% 股权经营者集中反垄断审查决定, [2012] 第 49 号).

37 Yaxing v Ambow Bejing, Supreme People’s Court of China [2015] Civil Final Judgment No 117 (最高人民法院民事判决书 [2015]民二终字第117号).

38 Contract Law of China, Art 52(3).

39 Nanping Liu, ‘An Ignored Source of Chinese Law: The Gazette of the Supreme People’s Court’ (1989) 5 Connecticut Journal of International Law 271, 294.

40 Yun Zheng, ‘China’s New Foreign Investment Law: Deeper Reform and More Trust are Needed’ (2019) Columbia FDI Perspectives, Perspectives on topical foreign direct investment issues No 264 <https://ccsi.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/docs/publications/No-264-Zheng-FINAL.pdf>.

41 Foreign Investment Law of China (中华人民共和国外商投资法), Art 4.

42 Ibid, Art 35.

43 Foreign Investment Law of China (2015 Draft) (中华人民共和国外国投资法(草案征求意见稿)), Art 11(1–4).

44 Ibid, Art 12(1)(2).

45 Ibid, Art 11.

46 Ibid, Art 18.

47 The investor nationality issue will be further discussed in Section IV, Part A.

48 Foreign Investment Law of China (2015 Draft), Art 15(6).

49 Ibid, Art 45.

50 Foreign Investment Law of China, Art 2.

51 General Office of the State Council of China, Notice on Forwarding the Several Opinions of the China Securities Regulatory Commission on Launching the Pilot Programme of the Issuance of Stocks or Depository Receipts Onshore by Innovative Enterprises [2018] No 21 (国务院办公厅转发证监会《关于开展创新企业境内发行股票或存托凭证试点若干意见》的通知, 国办发 [2018] 21号), Art 3.

52 SSE, STAR Board Listing Rules (上海证券交易所, 科创板股票上市规则), r 15.1(4)(5).

53 Ninebot employs a DCSS, issuing inferior voting shares with one vote per share to public shareholders while superior voting shares with five votes per share exclusively to the two Chinese co-founders, see Ninebot’s 2020 Annual Report filed on the SSE on 16 April 2021, <https://star.sse.com.cn/disclosure/listedinfo/announcement/c/new/2021-04-16/689009_20210416_10.pdf>.

54 SSE, Review Rules of Stock Offering and Listing on the Shanghai Stock Exchange Sci-tech Innovation Board [2020] No 89 (上海证券交易所, 科创板股票发行上市审核规则, 上证发 [2020] 89号), Art 48.

55 See Kent Lin, ‘Why Do Chinese Internet Companies Go IPO with the VIE Equity Structure?’ (6 July 2018) <https://medium.com/@tours4tech/why-do-chinese-internet-companies-go-ipo-with-the-vie-equity-structure-b44e271d87b0>.

56 Man (n 8) 217.

57 Robin Hui Huang, Securities and Capital Markets Law in China (Oxford University Press 2014) 335.

58 Hopkins, Lang and Zhao (n 10) 7.

59 John Osburg, ‘Global Capitalisms in Asia: Beyond State and Market in China’ (2013) 72 The Journal of Asian Studies 813, 822; Micheal J Enright, ‘China’s Inward Investment: Approach and Impact’, in Julien Chaisse (ed), China’s International Investment Strategy: Bilateral, Regional, and Global Law and Policy (Oxford University Press 2019) 28.

60 Micheal J Enright, ‘To Succeed in China, Focus on Interests Rather than Rules’ (2018) Columbia FDI Perspectives, Perspectives on topical foreign direct investment issues No 225, <https://ccsi.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/docs/publications/No-225-Enright-FINAL.pdf>.

61 See, e.g. Hopkins, Lang and Zhao (n 10) 7.

62 Ibid.

63 Rudolf Dolzer and Christoph Schreuer, Principles of International Investment Law (2nd edn, Oxford University Press 2012) 51.

64 See, e.g. ICSID Convention, Art 25(1) stipulates that ‘[t]he jurisdiction of the Centre shall extend to any legal dispute arising directly out of an investment, between a Contracting State … and a national of another Contracting State … ’. However, under rare circumstances, a state-state arbitration related to investment disputes could be carried out at an international tribunal, see ibid, 13.

65 Robert Wisner and Nick Gallus, ‘Nationality Requirements in Investor-State Arbitration’ (2004) 5 Journal of World Investment & Trade 927, 927; Chin Leng Lim, Jean Ho and Martins Paparinskis, International Investment Law and Arbitration: Commentary, Awards and Other Materials (Cambridge University Press 2018) 234.

66 Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah, The International Law on Foreign Investment (4th edn, Cambridge University Press 2017) 380.

67 Nationality Law of China (中华人民共和国国籍法), Art 3.

68 Julien Chaisse and Kehinde Folake Olaoye, ‘The Tired Dragon: Casting Doubts on China’s Investment Treaty Practice’ (2020) 17 Berkeley Business Law Journal 134, 159.

69 Foreign Investment Law of China (2015 Draft), Art 159.

70 Chaisse and Olaoye (n 68) 163.

71 See, e.g. the China-Australia BIT 1988, Art 1(1)(b) stipulates that ‘[i]nvestment means … admitted by the other contracting party subject to its law and investment policies applicable from time to time … ’.

72 Jeswald W Salacuse, The Three Laws of International Investment: National, Contractual, and International Framework for Foreign Investment (Oxford University Press 2013) 381; David Collins, An Introduction to International Investment Law (Cambridge University Press 2016) 69.

73 See, e.g. Fraport AG Frankfurt Airport Services Worldwide v Republic of the Philippines, ICSID Award, Case: ARB/03/25, the tribunal demonstrated that the circumvention of the local statute via a devised structure would move the investment outside treaty protection; In Shott v Iran, the tribunal held a similar viewpoint by denying the validity of the circumvention of the cap on foreign shareholding, see (1990) 24 Iran-US Claims Tribunal Reports 203.

74 See, e.g. the UK-Poland BIT 1988, Art 1(e).

75 See, e.g. the Germany-Thailand BIT 2004, Art 3(b).

76 ICSID Convention, Art 25(2)(b).

77 See, e.g. Vacuum Salt Product Ltd v Ghana, ICSID Award, Case: ARB/92/1, para 44 states ‘a tribunal … may regard any criterion based on management, voting rights, shareholding or any other reasonable theory as being reasonable for the purpose’.

78 See, e.g. the China-UK BIT 1986 and the China-Algeria BIT 2003.

79 See, e.g. the China-Bulgaria BIT 1994 and the China-Cyprus BIT 2002.

80 See, e.g. the China-Australia BIT 1988 and the China-Cuba BIT 2008.

81 See, e.g. the China-Austria BIT 1986 and the China-BLEU BIT 2009.

82 A subrogation clause is comprised in most BITs that China has concluded. An exception, see the China-Belarus BIT 1995.

83 Brandon Whitehill, ‘Buyer Beware: Chinese Companies and the VIE Structure’, 3 <https://www.cii.org/files/publications/misc/12_07_17%20Chinese%20Companies%20and%20the%20VIE%20Structure.pdf>.

84 Gillis and Lowry (n 6) 64.

85 See Charles Clover, ‘Alibaba IPO Shows Foreign Investors Able to Skirt Restrictions’ Financial Times (7 May 2014) <https://www.ft.com/content/7a8c4816-d5df-11e3-a017-00144feabdc0>.