ABSTRACT

Following the Chibok abductions of April 2014, the involvement of women and girls in the Boko Haram insurgency has increased, as has the subsequent analysis of them in both the academic and the grey literature. Contributions have mainly focused on how women and girls have been incorporated into – or used by – Boko Haram. In contrast, this article focuses on the response of the Nigerian government to the plight of women and girls that have become associated with Boko Haram. A qualitative analysis consisting of desktop research, consultation of policy documents and first hand interviews informed the research. The article finds that while the Nigerian government has taken note of the plight of these women and girls, it appears mostly an afterthought. Additionally, policy responses have not taken the full cycle of female participation in terrorist activity with Boko Haram into account. Recommendations to address this gap are offered.

Introduction

Before the Chibok abductions of April 2014, the terrorist group known as Boko Haram struggled to retain the attention of the global community. This mass scale abduction of over 200 defenceless young women from a school in Chibok, north eastern Nigeria, sparked much outrage across the globe, putting both Nigeria and Boko Haram under the spotlight. This spotlight has resulted in a growing body of literature on the group, some of which seeks to understand the plight of women and girlsFootnote1 associated with the Boko Haram insurgency. Prominent contributions to that literature include studies on abduction and gender-based violence as logical choices for Boko Haram, for strategic reasons;Footnote2 on the symbolism of women and girls in terrorist groups;Footnote3 on the factionalism engendered by the treatment and deployment of women and girls within the group;Footnote4 and on the varied ways in which women and girls take on the role of the victim,Footnote5 enabler and resilient survivor.Footnote6

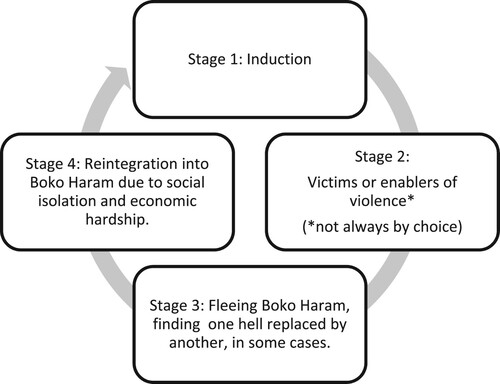

This article argues that following a decade of Boko Haram terrorism, however, there is an imbalance in the literature. While attempts have been made to analyse the response of the Nigerian government to Boko Haram on a broad scale, little of this literature has sought to understand the government’s response to the plight of women and girls who find themselves – whether voluntarily or involuntarily – associated with Boko Haram. This article seeks to fill this gap by means of a policy review, justified on two grounds. First, the female gender has taken on a strategic significance within terrorist operations which shows no sign of ceasing. Second, the multi-stage experience of many women and girls within Boko Haram – what this article terms the participatory cycle of violence – needs to be understood. This cycle goes beyond the period of time in which a woman or girl is directly associated with Boko Haram, with important implications for their reintegration into society. A comprehensive understanding of this participatory cycle is critical to well-informed policy responses within a broad definition of counter-terrorism.Footnote7

This article’s investigation unfolds with a brief history of Boko Haram before moving on to a discussion of women and girls associated with the group, followed by a conceptualisation of the participatory cycle of violence. Thereafter, the policy analysis will commence. The outcomes of the policy analysis will then be interrogated within the Nigerian context, allowing for recommendations on how to advance the Nigerian government’s responses to the plight of women and girls associated with Boko Haram. Finally, the conclusion summarises the main findings and highlights areas for further research.

Boko Haram: A bird’s eye view

Jamā’a Ahl al-sunnah li-da’wa wa al-jihād (referred to by the acronym JAS) emerged in Nigeria as a Muslim advocacy group opposed to a style of governance it saw as increasingly Westernised, to the detriment of the Muslim faith. The date of this emergence is placed at 2001, however that date and the impetus behind the group, are heavily disputed.Footnote8 Mohammed Yusuf, an Islamic cleric in Maiduguri, a city in the north eastern region of the country, is often credited with bringing JAS (often referred to as Boko Haram but in fact a faction) to prominence. Following the departure of several religious scholars from Maiduguri to further their Islamic education in Saudi Arabia,Footnote9 Yusuf filled the leadership vacuum left behind. He consolidated his influence by reinforcing his words with action, calling upon his followers to adopt Islamic principles in everyday life and establishing a community that was self-reliant and governed by Islamic principles. Yusuf enabled that self-reliance by offering loans for the establishment of small businesses, or for the purchase of motorbikes.Footnote10 This philanthropic approach earned him much respect, which soon came to the attention of northern Nigeria’s political elite. One such politician who took particular note of Yusuf’s popularity was Ali Modue Sheriff, who sought Yusuf’s help in delegitimising a rival, Mala Kachalla, for the governorship of Borno State. In an attempt to achieve his political objective Sheriff stuck a deal, offering a post in his cabinet to Boko Haram in return for ardent public support for himself. Sheriff also offered to advance, with haste, the implementation of the strict Islamic legal code, sharia, in northern Nigeria.Footnote11 In the wake of his electoral victory, Sheriff appointed Buji Fori to his cabinet, but failed to follow through on the second half of this agreement regarding sharia. As a result, Yusuf used his wider influence to portray the Nigerian government as illegitimate due to this failure to keep promises.

Between 2003 and 2009, Boko Haram carried a number of small-scale attacks against institutions of the state (such as police stations) and individuals who opposed the group publicly.Footnote12 Tensions between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram members continued to escalate, with many of Yusuf’s students and followers being arrested. It remains unclear if Yusuf ever endorsed violence as a means to an end.Footnote13 However, an interview he had with the BBC in 2008 suggests that Yusuf began to see physical confrontation as a means to achieving his goals; in response to the BBC’s question on how he intended to secure the release of his arrested followers, he stated: ‘I will follow the due process and legitimate means prescribed by Allah to secure their release because we [Boko Haram] do not take illegal steps unless it becomes necessary.’Footnote14 The confrontation continued until Yusuf’s death in 2009.Footnote15

Boko Haram went underground following Yusuf’s death, emerging a year later to declare a formal jihad against the Nigerian governmentFootnote16 and was in turn officially declared a terrorist group in November 2013.Footnote17 Over the next decade, the group’s tactics would evolve so as to yield strategic advantage for Boko Haram. Under the direction of Yusuf’s successor, Abubakar Shekau, the group expanded its campaign of terror, conquering towns such as Maiduguri, Mubi and Gwoza. And while certain traditional local practices were maintained under Shekau – such as ensuring that one’s wife is cared for adequately, both before and in marriageFootnote18 – he took a hardened stance towards ‘outsiders’ (those opposed to Boko Haram) regardless of whether they were civilian or military. The former constituted 49% of all Boko Haram’s targets, and the latter 44%,Footnote19 while other armed non-state actors accounted for 2% of Boko Haram’s targets.Footnote20 Under the expanding terrorist role of Boko Haram, however, internal dissent grew, resulting in the split of Boko Haram into three factions. The first splinter group, known as Ansaru arose under a rival of Shekau’s, Mamman Nur, who is credited with the bombing of the UN headquarters in August 2011.Footnote21 The precipitating event for Ansaru’s rise was the armed assault on Kano city under Shekau’s command on 20 January 2012, during which 186 Muslims were killed.Footnote22 This outraged Shekau’s opponents who saw this as indiscriminate targeting. By 2015, Shekau declared bay’ah Footnote23 to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). While ISIS lauded the Chibok abduction of a year earlier (and used that to justify the abduction of 7 000 Yazidi women also in 2014),Footnote24 ISIS at the same time expressed disapproval of the ill-treatment of women (including limited access to food)Footnote25 as well as the deployment of female suicide bombers on a mass scale.Footnote26 As such, Boko Haram factions perceived to be behind such abuses of women fell out of favour. Thus, despite Shekau’s declaration of bay’ah, ISIS declared in August 2016 that Abu Musab al-Barnawi would be officially recognised as the official leader of its affiliate in the region, the Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP), thereby resulting in the emergence of the third faction. At present Boko Haram still consists of three factions – that referred to as JAS under Shekau, Ansaru which is currently leaderless, and ISWAP under al-Barnawi.Footnote27 Armed conflict continues between Boko Haram's factions and some governments of the Lake Chad Basin (ie, Algeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Libya, Niger and Nigeria).

With the three factions arising from Boko Haram now clearly defined, it is important to mention that the phrase ‘Boko Haram’ is used to refer to the movement in its entirety while the acronyms of specific factions (or the names of their leaders) will be used to assign specific activities to specific factions.

The Chibok abductions: A brief overview

As this article views the Chibok abductions of April 2014 as a watershed moment for both terrorism and counter-terrorism in Nigeria, a brief overview of that event is called for. On the night of 14 April 2014, men masquerading as soldiers raided the dormitory of the Chibok Secondary School, informing the schoolgirls that they were there to protect them.Footnote28 A grand total of 276 schoolgirls were escorted out of their dormitory through the school’s gates to waiting motor vehicles and trucks, which transported the girls on a journey into forested areas, concealing the militants and school girls from all attempts to track them.Footnote29 On 14 May 2014, Shekau released a video announcing that the Chibok girls would be sold as slaves. He further noted that Boko Haram had abducted the girls as a means of retaliation for the capture of Boko Haram fighters.Footnote30 On 1 November 2014 Shekau released another video in which he asserted that more than 200 of the 219 remaining Chibok girls had converted to Islam and had been married off.Footnote31 By 2018, it was estimated that 162 of the Chibok girls had managed to regain their freedom, either by escaping or by release following intensive negotiations between the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Swiss government and barrister Mustapha Zanne.Footnote32 Some of these later negotiations involved the swapping of Boko Haram fighters imprisoned by the Nigerian government for the Chibok hostages. Towards the end of January 2021, it was reported that an unknown number of Chibok hostages managed to escape, but this event was never confirmed by the Nigerian government.Footnote33 In the run up to the 7-year anniversary of this unfortunate event, the Nigerian government released a statement reaffirming its commitment to securing the release of the 112 remaining Chibok hostages.Footnote34

The association of women and girls with Boko Haram

Much of the dialogue on the association of women and girls with Boko Haram is linked to the Chibok abductions.Footnote35 However, it is notable that there were female participants in Boko Haram before the Chibok abductions.

During Yusuf’s time as Boko Haram leader, women and girls took on a reserved role in the organisation by means of the purdah. which involves the seclusion of women in public by means of covering themselves. Yusuf managed to attract and retain a female following since he encouraged women and girls to study the Quran as well as arranged marriage within Boko Haram, which was portrayed as a way to alleviate many of the social and financial pressures experienced by women.Footnote36 Fieldwork by Hilary Matfess also suggests that Yusuf delivered gender-focused sermons and stipulated that the needs of wives were to be well tended to, both before and during marriage.Footnote37

Women and girls in Boko Haram post-Yusuf: Pathways and participation

While the roles of women and girls in Yusuf’s Boko Haram were more ‘backstage’ in nature, their roles have become much clearer following his death. In order to understand these roles and how women and girls come to occupy them, it is crucial to understand the pathways that lead women and girls to Boko Haram. There are social, economic and political avenues to consider.

Social pathways to Boko Haram

Northern Nigeria is a patriarchal society in which women have little autonomy; decisions are made for them by a male guardian outside the confines of their domestic space. In studies of former female members of Boko Haram, many respondents reported joining Boko Haram as they felt that the group helped to elevate their societal status.Footnote38 Women and girls may also be pressured to join Boko Haram for the benefit of male family members, who are drawn to the prospect of being afforded social and political power in the form of emirships.Footnote39 In addition, there is also the problem of misrepresentation. Given that the official counter-narrative against Boko Haram is weak, many women accept what they hear about the group offering them better social and economic livelihoods, without formulating a proper understanding that these advancements are subject to their compliance with group rules and ranking.Footnote40 It is also worth mentioning that literacy rates among males in northern Nigeria are far higher than those of their female counterparts.Footnote41 Given the low literacy rate among female inhabitants of northern Nigeria, it can be argued that women and girls are inadequately equipped to assess the narratives perpetuated by Boko Haram. Finally, there is the influence of ideology. But this may be overstated: while 82% of those fighting to end Nigeria’s ‘war on terror’ believe that people join Boko Haram for religious reasons, while in fact only 9% of former Boko Haram members indicated that they joined for ideological reasons.Footnote42

Economic pathways to Boko Haram

Nigeria’s overall unemployment rate, as of January 2021, was 33%, and its youth unemployment rate was reported to be 53%.Footnote43 Thus, prospects for financial security are weak. The stipend offered to wives of Boko Haram fighters is thus very attractive; the funds are often used to support family members, even those outside of the group. An additional lure for women is the payment of the ‘bride price’, in exchange for agreement to marry, which can sometimes reach $13 (5, 000 Naira).Footnote44 This payment, made directly to the woman in some cases, offers newfound financial independence.Footnote45

Political pathways to Boko Haram

The political lure of Boko Haram is threefold. Firstly, there are extensive governance gaps in northern Nigeria, leaving locals open to cooperating with those offering the required services. ISWAP, for instance, has decided to take advantage of one gap; this faction of Boko Haram provides farmers with essentials such as seeds and fertiliser to help them to establish sustainable agricultural production. In return, ISWAP collects tax from the populations they assist. Secondly, women and girls are often made to feel insecure at the hands of Nigerian security forces who have often been accused of exercising unnecessary force against civilians in their efforts to stamp out Boko Haram. This has resulted in women and girls aligning themselves with Boko Haram for security reasons.Footnote46 Lastly and perhaps most importantly, one needs to address the issue of coercion. Many experts and observers agree that the initial induction into Boko Haram for many women and girls is by means of force.Footnote47 Henshaw notes six likely characteristics of people who are coerced into joining terrorist groups:Footnote48

They are likely to be younger than 15 years of age;

They have likely been threatened with assault;

It is likely that their family members have been threatened to ensure the target’s cooperation;

They have likely been forced to take drugs;

They are not likely to be able to opt-out of the group;

It is likely that their livelihoods, or those of their family, have been destroyed, thereby complicating and possibly permanently impeding a return to normal life.

While the experience of every woman or girl who has been coerced into joining Boko Haram differs slightly, the above-listed characteristics are evident in both eye-witness accounts and in the literature. For instance, 16-year-old Hajja was abducted from her village, together with six other girls, by Boko Haram in 2014. The girls were given the choice of enslavement or marriage. Hajja chose marriage while her counterparts chose slavery, which included rape, limited access to food, and labour.Footnote49 Hajja became the fourth wife to a Boko Haram commander. When he was killed in battle sometime later, Boko Haram placed pressure on Hajja to marry again. Any displays of reluctance resulted in threats of whippings. Desperate to find a way out, Hajja asked to become a suicide bomber.Footnote50 Research suggests that the Boko Haram administer pain killers to their suicide bombers,Footnote51 with the youngest suicide bomber reportedly seven years of age.Footnote52

The role of the female in Boko Haram

Women and girls have long played critical roles in terrorist groups.Footnote53 Given that Boko Haram is an Islamist organisation, most would expect that women and girls occupy supporting and administrative roles. And while there is some merit to this argument, a look beyond the expected illustrates that there is more to female participation than meets the eye. AgbajeFootnote54 advances this argument well by positing that the ‘objectified female body’ is used as a multi-purpose instrument of war. Unfortunately, this classification views the female body solely as a physical tool, negating the intangible functions that women and girls have taken on within society. In response, this article employs an eight-part typology to formulate a better understanding of the role of the female within Boko Haram.

Agents of communication

Following the Chibok abductions, Boko Haram deployed its first female suicide bomber, in June 2014, and has subsequently deployed women extensively in this role.Footnote55 Research by Vesna Markovic showed that between 2011 and 2018, 53% of all Boko Haram suicide bombers operating in West Africa were female.Footnote56 This mass deployment of female suicide bombers is strategic on Boko Haram’s part as it helps to ensure that the group retains the gaze of the international community, both on a regional and trans-regional level, while simultaneously helping to facilitate branding between the three factions. The group under Shekau, often referred to by the original name or JAS, has a preference for deploying suicide squads consisting of at least three suicide bombers, despite the fact that analysis indicates that suicide squads are less effective than individual suicide bombers.Footnote57 This may indicate that JAS is more interested in exploiting Western sensitivities through playing on stereotypes, as opposed to accumulating a rising death toll. As such, it can be argued, Boko Haram is using female suicide bombers for both internal and external communication purposes. Internally, female suicide bombers (or an avoidance thereof) are used to communicate the differing moral thresholds between factions, mostly to potential recruits and parent organisations. Externally, female suicide bombers are useful to attract attention to Boko Haram for their extraordinary nature – gender stereotypes do not generally associate such violent acts with the female gender.

Symbols of revenge

During Boko Haram’s formative years, the Nigerian military would arrest the wives and daughters of the group’s leaders with the intention of encouraging a laying down of arms.Footnote58 Shekau was personally affected by this tactic in September 2012 when the military ambushed a naming ceremony just outside Maiduguri; the ambush resulted in the arrest of Shekau’s wife and three children.Footnote59 As a result, it is arguable that Shekau used the Chibok abductions as a means of settling an outstanding score.

Recruitment agents

Boko Haram acknowledges the importance of encompassing various actors in its operations. This is evident given the all-female committee, founded by Shekau, tasked with the recruitment of women and youths into the group.Footnote60 In 2014 three women were arrested by the Nigerian military for luring women to join Boko Haram. One of the women, Hafast Boko, claimed to be part of a ‘female wing’ within Boko Haram responsible for the recruitment of women.Footnote61 Women have also been instrumental in recruiting young men and women by means of hosting and facilitating gatherings where Boko Haram is ‘marketed’ to attendees.Footnote62 It is also worth noting that while JAS established this committee, it is likely to have been copied by ISWAP.Footnote63 ISWAP, like ISIS, seeks to establish a physical territory which can only be sustained by means of ensuring a steady flow of recruits into the organisation. Furthermore, given that ISWAP is even more concerned with winning hearts and minds, such an all-female committee would serve its purposes well for recruiting from among women.

Intelligence officers

Women and girls also serve in gathering intelligence from different factions. For, while it has been speculated at times that Boko Haram’s three factions might cooperate on mass-scale operations such as the Chibok abductions,Footnote64 more recent evidence suggests that each faction prefers to vie for dominance, and will spy on one another to gain advantage. Women and girls are ideal for this task as they are unsuspected – as is the case with suicide bombings. In 2014 three women were arrested who were later found to be spies for JAS deployed with the aim of gathering information on upcoming military operations and to gauge public opinion.Footnote65 The provision of intelligence on planned attacks by one faction against another factions has also become commonplace.Footnote66

Managers

Boko Haram deploys women as managers in Boko Haram camps, albeit within socially acceptable levels, to supervise the work done by other women tasked with cleaning, cooking and other domestic tasks.Footnote67 This role allows women to elevate their status within the group, which allows them to advance their chances of survival.

Reproductive agents

The long-term ambitions of Boko Haram, particularly among the JAS and ISWAP factions, is to establish a state or caliphate, populated by a nation of adherents. This has driven Boko Haram to ensure a means of producing the next generation of jihadists to help sustain the group – militants are reported to pray for pregnancy to occur before engaging in sex.Footnote68 A report from 2015 found that, of a group of 234 women and girls rescued from Boko Haram by the military, 91% of them were found to be pregnant.Footnote69

Labourers and sex slaves

Women and girls abducted by Boko Haram have been made to cook, clean and collect water and firewood.Footnote70 They are also raped arbitrarily by men who are allowed to engage in sexual relations as a means of reward for good performance on the battlefield.Footnote71

Wives

The rank of ‘wife’ is one of the highest ranks a woman or a young girl can obtain within Boko Haram. While gender-based violence does occur among women and girls married to male Boko Haram members,Footnote72 it is important to remember that wives receive better treatment than other females within Boko Haram. This is most clearly reflected in grassroots research conducted by Matfess, in which former Boko Haram wives reflected on their time with the terrorist group. According to one of these women: ‘[There] was 100% better treatment as a wife under Boko Haram. There were gifts, better food and lots of sex that I always enjoyed.’Footnote73

Life after Boko Haram: From Boko Haram to ‘hell and back again’

Some women and girls are fortunate to escape from Boko Haram, either by fleeing or by means of rescue by the military. Beginning in 2015, women and girls fled Boko Haram in large numbers, most likely due to the fact that the Nigerian military began retaking control of territory claimed by Boko Haram.Footnote74 Unfortunately, with authorities being poorly prepared, many returnees were taken to the Giwa Barracks (a military-run prison in Maiduguri), where they suffered inhumane conditions and further abuse at the hands of the Nigerian military, according to reports by international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.Footnote75 Under this international pressure to address the growing number of female returnees, the Borno State government established the Safe House Programme (SHP). The SHP, which hosted 36 women for 16 months, was one of the earliest female-centric responses to Boko Haram.Footnote76 While the main object of the programme was to deradicalise women, returnees were retaught Islam, given skills training and psychosocial support and were taken through therapeutic activities designed to help the participant reject violence and intolerance. The SHP has come under fire, however, for several reasons. Some blame the SHP for shifting attention and time away from addressing the needs of internally displaced persons (IDPs).Footnote77 The success of the SHP has also been questioned as 75% of participants had returned to Boko Haram by 2018.Footnote78 In the face of this minuscule success, the Borno State government closed the SHP sending remaining participants to their families or to IDP camps.Footnote79

The Borno State government rekindled its efforts in 2016 with the establishment of the Bulumkutu Transit Centre (the Centre). The Centre has a capacity of 300 and aims to assist women for a period of three months, during which time they undergo group theory and are given spiritual guidance and skills training, with the aim of family integration.Footnote80 Despite being a female-centric response to Boko Haram, the Centre has also become a place of sanctuary for men, the elderly and the disabled, placing strain on the Centre’s already limited resources. As a result, many key programmes are shortened in duration, and some women are turned away.Footnote81 Upon leaving the Centre, women are given some money by the state and are reconnected with relatives, some of whom live in IDP camps.Footnote82

When women and girls leave the Centre, however, they are often ostracised by their families and local communities as a whole. While the experience among former female Boko Haram associates differs, some field work undertaken by the International Crisis Group (ICG) has helped to shed some light on the ostracisation phenomenon. In their research, the ICG reported that one father of a former female Boko Haram associate noted, ‘I will never trust her again.’ He further noted ‘They have been taught bad attitudes that I will never understand … What they learn with Boko Haram, I swear, they will never abandon it.’Footnote83

Ostracised female returnees are taken to IDP camps as a means of survival. Unfortunately, many do not manage to escape the ostracisation; many of the camps are village-based, meaning that the returnees are still surrounded by family, former friends and neighbours who regard them as annova or ‘bad blood.’Footnote84

Conditions in the IDP camps are rundown, with many residents reporting a lack of sufficient food or much-needed medical attention.Footnote85 The lack of socio-economic opportunities available to women and girls forces many of them into prostitution outside the camp, where they can exchange sexual favours with various partiesFootnote86 for more or better food, or to return to Boko Haram, where women of sufficient rank were given a stipend by the group.Footnote87

The exact rate of recidivism among former female associates of Boko Haram is hard to determine, but this occurrence cannot be ignored. One former female associate of Boko Haram noted, in the ICG study, that both she and her husband had joined the group shortly after getting married.Footnote88 She was eventually pulled out of Boko Haram by the Nigerian military, to which her response was ‘The soldiers brought us back forcibly from Boko Haram, we would not have come back on our own … I want to go back [to Boko Haram] because by husband is there.’Footnote89

In addition to some choosing to return to be with a partner or husband,Footnote90 or seeking economic upliftment, some former female associates believe that it is a shame and dishonour for their communities to have to rely on humanitarian aid from organisations such as the United Nations Children’s Fund.Footnote91

Taken together, these factors can result in feelings of isolation emerging which can make some former female associates long for the interest Boko Haram had shown in them. Fatima Imam (a civil society leader from northern Nigeria) notes that the lack of communal sense in this regard (in lieu of that offered by Boko Haram) could perhaps explain by women and girls elect to engage recidivist tendencies.Footnote92

It is thus clear that the association of a woman or a girl with Boko Haram, whether voluntarily or through coercion, does not end after she flees or is rescued by the military; often her tumultuous cycle of violence continues (see ).

The response of the Nigerian government

The menace that is Boko Haram has been present for just over a decade. As a result, the Nigerian government has enacted several initiatives to address this menace, including laws, frameworks and other mechanisms. Keeping in mind the foregoing discussion of the various pathways presented to women and girls which induce participation of different forms within Boko Haram, analysis turns to the government’s response to the problem, taking on a particularly gendered lens. It should be noted that not all the documents discussed in this section are in the public domain; as such, the article relies on interviews and independent analysis to fill gaps.

While Nigeria has had to deal with jihadists in the past,Footnote93 these were dealt with via military means,Footnote94 thus giving Nigeria little experience with ‘softer’ counter-terrorism measures. Despite its past experience with insurgents, Nigeria did not pass official anti-terrorism legislation until June 2011, when it enacted the Terrorism Prevention Act. There is some conjecture that Nigeria chose to enter the counter-terrorism fray relatively late, to avoid becoming a Western pawn in the ‘Global War on Terror’ following the events in the US on 11 September 2001.Footnote95 In any case, Nigeria’s stance changed following two key events. These were, namely, the suicide attempt by Nigerian Abdul Farouk Muttallab while on board US Northwest Airline Flight 253 to Detroit on 25 December 2009, and Boko Haram’s armed assault on UN headquarters in Abuja on 26 August 2011. Both these events prompted the US to impose a travel ban on Nigeria as well as economic sanctions. In return, Nigeria acted. Legislation was passed, and Abuja was prompted to finally diversify its all-military approach to counter-terrorism.

Concerning the Terrorism Prevention Act of 2011, it is worth noting that this act does not mention the terms ‘gender’ or ‘women.’ These terms would only be mentioned in the Terrorism Prevention (Amendment) Act of 2013 amending Article 25, Section Three, which reads ‘notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (1) of this section, a woman shall only be searched by women.’Footnote96 While this is an encouraging development as it makes prevision for women to be accommodated within the security architecture, it is far from adequate in terms of addressing the full scope of the challenges arising from women and girls associating – whether voluntarily or involuntarily – with Boko Haram.

In 2014, Nigeria’s former President Goodluck Jonathan signed and presented Nigeria’s National Security Strategy (NSS), which took a state-centric view of security and acknowledged that terrorism was a major security concern – though again there was no acknowledgement of gender in the document. Nigeria’s countert-errorism response was more fully outlined by President Goodluck Jonathan in a separate document, touted as a ‘soft’ approach to counter-terrorism and referred to as the National Counter-terrorism Strategy (NACTEST). NACTEST initially consisted of four streams,Footnote97 namely:

deradicalisation of convicted terrorists, supporters of a terrorist group as well as those awaiting trial on charges of terrorism;

a departure from the government-centric approach to a ‘society approach to counter-terrorism thinking’;

building the capacity of the military and law enforcement agencies involved in counter-terrorism practices utilising strategic communication; and

formulating a comprehensive understanding of the economic root causes of terrorism and formulating a response with governors from northern Nigeria based on global best practices.

Under President Muhammadu Buhari, in office since 2015, the Nigerian government sought to revise the NACTEST replacing the four streams with five pillars designed to:

Forestall: Aims to stop Nigerians from becoming terrorists;

Secure: Aims to bolster the capacity of security actors;

Identify: Aims to design and implement early-warning systems that aim to pre-empt radicalisation and terrorist activity;

Prepare: Aims to mitigate the impact of terrorist attacks; and

Implement: Aims to provide a blueprint for cross-governmental implementation

Again, there is little to no indication that specific steps are taken to address the plight of women and girls in this formulation. It should also be noted that the importance of civil society actors is not specifically acknowledged.

Finally, in 2017 when the Nigerian government introduced its National Framework and National Action Plan for Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (the P/CVE Action Plan), there was an acknowledgement of the role that women have come to play – as suicide bombers as well as agents of recruitment. The P/CVE Action Plan goes on to outline how women could be used to counter Boko Haram:Footnote98

As wives, sisters and mothers, policymakers or law enforcement officers, women have a strategic role to play in the treatment, rehabilitation and reintegration of violent extremist offenders. We know that mothers can play an emotive role in reaching out to extremist offenders to change their violent behaviour. Women’s roles in homes and communities can pick up early signs of radicalisation in young persons. This insight is also relevant for counter-messaging to break up the cycle of radicalisation. We will tap into this insight in designing effective prevention programmes. To achieve safety and livelihood for women and girls, [women’s] organisations have a critical role to play through advocacy and programming.

The above is extremely encouraging, but it is imperative to note that not all non-governmental organisations involved in counter-terrorism and counter-violent extremism efforts enjoy the same support. For example, the Youth Coalition Against Terrorism (YCAT) – which, granted, operates on a much smaller scale and also began its operations without reference to the issue of gender in terrorism – is not given the same level of support as the aforementioned organisations. Another effort, the Partnership Against Violent Extremism (PAVE) Network, was established under former President Goodluck Jonathan to bring the state and civil society actors involved in the fight against Boko Haram together to aid in the facilitation of cross-sector collaborationFootnote103 – although it remains unclear whether PAVE explicitly notes the role of gender in their efforts, and the current state of the PAVE Network is unclear.

In 2019, Buhari relaunched the NSS, which in its revised form departed from the state-centric approach to human security. As President Buhari indicated in his speech launching this initiative:Footnote104

These priorities reflect our commitment to enhancing the social security of Nigerians as a means of improving their physical security. I’m happy to observe that the National Security Strategy reflects this thinking with an emphasis on overall human security …

The reality … is that women are largely excluded from many formal peace processes. In the terrorism affected states, women and children constitute the largest [group of] internally displaced persons and refugees across the border. Women are not just victims of war; they are also agents of peace. Appropriate legislation will be adopted to enhance gender security with a view to promoting inclusiveness across various sectors of the economy.

This statement from Buhari provides insight into the progress, and continued challenges, in addressing the plight of women and girls affected by Boko Haram. On the one hand, it signals a clear acknowledgement that women have been adversely affected by Boko Haram’s activities and ought to be included in any peace processes that may assist in the cessation of the insurgency. However, on the other hand, there are some areas of concern. Firstly, a recognition of the impact on girl children, as well as women, would be important in view of the fact that young girls have much less agency than women in their involvement with Boko Haram – they are either forced into membership, or may be born into the group. Additionally, the above quote implies that women should be included only during the peace process whereas the set of roles noted within Boko Haram would indicate that women and girls have key roles to play in stimulating change at various stages of the process to end extremism and insurgency in Nigeria. Finally, the Nigerian approach appears to deem it necessary to facilitate legislative redress only from an economic perspective. While such legislation is encouraging, as it lays the groundwork to begin the closure of the socio-economic gaps exploited by Boko Haram, it does not address other social ills, such as the schisms between northerners and southerners,Footnote106 nor the role religious leaders can play in countering terrorism – a role that has been dampened by politicians under Buhari. At the time of this writing, the Terrorism Prevention Act is currently under review for a second amendment; the content for review was as yet unclear.Footnote107

Moving from referenced aspirations to a changed reality

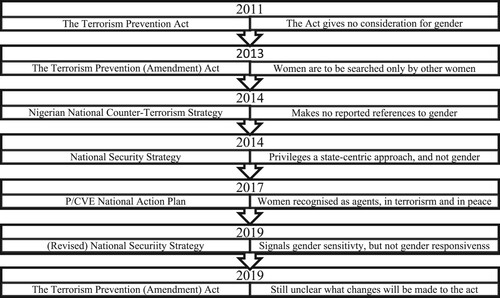

The previous section sought to unpack Nigeria’s counter-terrorism response from a gendered angle, with a particular focus on women and girls. Several observations have come to the fore, as depicted in .

Figure 2. Chronology of Nigeria’s response to the effect of terrorism on women and girls.

Source: Author’s analysis of Nigerian government documentation.

First, from this chronology it becomes clear that counter-terrorism legislation came into effect only in 2014, which is three years after Boko Haram transformed from a Muslim advocacy group to a terrorist group. In this first iteration of the Terrorism Prevention Act, gender was not referenced.

Second, the issue of women and girls vis-á-vis terrorism appears to have remained an afterthought for Nigerian policymakers, despite the continued exploitation of those women and girls by – or their participation in – Boko Haram, heightened by the Chibok abductions of 2014. Only in 2017 did the plight of women and girls make a first prominent appearance in the Nigerian policy discourse on terrorism, four years after Chibok.

This ‘afterthought’ was not only evident in the state sector, it should be noted, as non-state actors such as YCAT have subsequently acknowledged that they too had overlooked the importance of a gendered response in designing programmes to counter terrorism.Footnote108

A third observation, based on the research finding that the Terrorism Prevention Act of 2011 and the National Counter-terrorism Strategy of 2014 are seen as complementary documentsFootnote109 is that it remains unclear how the P/CVE Action Plan, under which the plight and agency of women are acknowledged, interacts with those policy documents. This uncertainty adds to the well-established criticism that the Nigerian government’s strategy lacks coherence.Footnote110

Fourth, Nigeria’s national security advisor is legally tasked with the coordination of counter-terrorism activities in the federal republic, It is argued here that this arrangement may be a key impediment to Nigeria’s response to terrorism. The national security advisor, by definition, has only advisory powers in the presidency. As that cabinet member lacks the decision-making powers that would be legally binding, this makes it difficult to ensure that any recommendations made are enforced.Footnote111 Furthermore, the office of the national security advisor is usually staffed with military and intelligence personnel, bringing a military perspective that is not renowned for gendered responses.Footnote112 Fatima Akilu, a former official in the office of the national security advisor responsible for counter-violent extremism programmes between 2012 and 2015, noted in an interview with the author that: ‘It wasn’t just that I was a woman, I was coming [into the office of the national security advisor] with a very different skill set, a different orientation, a different way of thinking.’ This observation was made regarding her professional background as an academic and a psychologist. Akilu further observed: ‘ … I think in the beginning, I wasn’t taken very seriously probably because I was a woman.’

Fifth, it would appear that, at least in the current period, civil society actors may be better equipped than national government to address the plight of women and girls, as evidenced by the work of the Neem and Allamin Foundations. On the other hand, the PAVE Network no longer appears to have the same level of access to its network in the national security sector that it enjoyed prior to Buhari, which has left civil society actors to mostly ‘network’ and cooperate among themselves.Footnote113

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the responses of the Nigerian state to the plight of women and girls associated with Boko Haram have not adequately addressed Boko Haram’s deployment of women and girls outlined in the eight-part typology above.

With these observations in mind, recommendations for the way forward are offered.

Charting the way forward

As has been clearly illustrated, the plight of women and girls has not been adequately addressed within the context of the Nigerian government’s response to Boko Haram. This section will briefly outline how the Nigerian government could better align its counter-terrorism efforts with the challenges outlined above.

Ensure better cooperation between policy documents: The forthcoming amendment to the Terrorism Prevention Act should ensure that legal consideration and provision be made for the inclusion of gender considerations, and how the act can be better integrated not only with the National Counter-terrorism Strategy but also the P/CVE Action Plan. This will give clearer guidance on how to accommodate women and girls in the government’s response to terrorism.

Showcase the skills of women to the establishment: Women are often seen as unsuitable candidates for policy-making in the areas of counter-terrorism and countering violent terrorism, due to the masculine bias surrounding terrorism.Footnote114 In the (West) African context, women are appointed without any regard for their skill set, which has helped men to justify why women should be excluded from policy-making discourses.Footnote115 In response, the Nigerian government should take a grassroots approach to counter violent extremism. For instance, in group discussions of experiences of terrorism, participants might be given the opportunity to stand in a line with a facilitator asking a series of questions relating to both their experiences of Boko Haram and any skill sets they may have, allowing them to respond – without value judgement attached to those responses – by stepping forwards or backwards. This visual display of shared experiences would assure women that they are not alone as victims – or as agents – of Boko Haram and, more importantly, would highlight the skills and strength of character gained that could be put to use in community-based efforts to counter violent extremism. This practice has been tried and tested in other conflict zones in Africa.Footnote116

Acknowledge both female and male perspectives in discussions on gendered responses to terrorism: Men and women experience Boko Haram differently, and the pathways they take to terrorist violence are likely to differ. As such, greater efforts at data collection should be made to ensure that these different pathways are understood. A greater understanding in this regard, based on evidence, would strengthen the gendered response to counter Boko Haram. This may also help improve the development of female agency, as their paths to Boko Haram are often influenced by male relatives.Footnote117 In terms of the participatory cycle of violence, it is expected male influence would be greatest in stages one and four.

Make provision for gender responsiveness: At present, the P/CVE Action Plan and the revised NSS are gender-sensitive, but do not lay the foundations to enact the sensitivity as outlined in the policy documents. These could be achieved by means of surveying best practises from other government initiatives on gender, consulting further with women and girls who have experience of Boko Haram, and formulating action plans that specify guidelines and enable measurement at the implementation phase.

Rekindle PAVE: This initiative, while still possibly active, has an uncertain future. For one, it has lost its connection to the national security sector, as noted earlier, with changes in administrations. Officials responsible for coordinating policy on counter-terrorism and countering violent extremism should reintegrate PAVE back into the network of groups active on this front, so as to strengthen the relationship between state and non-state actors involved in the fight against Boko Haram. This relationship is imperative given the private sector’s advanced capacity both in terms of resources and community trust.

Strengthen the place of gender-sensitive religious leaders and scholars: It is widely known that women and girls associated with Boko Haram have been ostracised by their communities upon their return. The easiest way to dampen this unfortunate occurrence is for religious leaders to sanction the return of returnees,Footnote118 once reintegrated through well-designed deradicalisation programmes, to minimise ostracisation. PAVE may have a role to play in this regard.

Conclusion

This article has attempted to provide a policy review of the Nigerian government’s response to the plight of women and girls associated with the terrorist organisation Boko Haram, by means of desktop research, policy document analysis and interviews. In doing so, this article considered various pathways – economic, political and social – that lead women and girls into Boko Haram, as well as the roles that females take on within Boko Haram. The article also introduced the concept of the participatory cycle of violence, which sought to highlight the fact that the period of time a woman or girl spends affected by Boko Haram does not end when she successfully flees the group or is rescued by the military. This article has shown that women and girls are drawn back to Boko Haram for social and economic reasons, and this draw presents one of the greatest challenges in countering the impact of the group in Nigeria. Additionally, the research found that the Nigerian government has been slow to integrate gender into their responses to Boko Haram. The reasons for this include differing leadership styles between presidents, with President Jonathan taking a more inclusive approach to counter-terrorism and efforts to counter violent extremism while President Buhari has demonstrated that he prefers an elitist approach which focuses on a display of force, as well as the structure of the national security advisor’s office which oversees P/CVE efforts. It is clear that, while legislation is enacted and encouraging signs of greater gender sensitivity exist, women have been largely excluded from counter-terrorism P/CVE policy development and implementation.

Future research on gendered responses to the menace of Boko Haram might look more carefully at policy responses to IDPs and IPD camps,Footnote119 where women and girls are also vulnerable to both exploitation and radicalisation, and ways to more effectively reduce the rate of recidivism among female Boko Haram participants.

Acknowledgement

This article is partly based on research pertaining to a Master of Arts degree in Politics under the supervision of Suzanne E. Graham and Rebecca Emerson-Keeler at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. The author is grateful for ongoing support, from both supervisors, for this and other projects related to this research. The author further wishes to extend his gratitude to all colleagues who have supported his research on Boko Haram over the last 3 years.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sven Botha

Sven Botha is, at the time of this writing, the Head Tutor and a MA candidate in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Johannesburg. His MA research focuses on the evaluation of counter-terrorism programmes in the African context via a gendered lens. He is a member of the South African Association of Political Studies (SAAPS) and is also a former member of SAAPS’ executive council (2019–2021). Sven’s research interests include terrorism, counter-terrorism, preventing/countering violent extremism, gender, diplomacy, foreign policy and early-career development in the Social Sciences.

Notes

1 In the context of this paper, a distinction is drawn between women and girls with the aim of highlighting that some female suicide bombers are under the age of 18. To date, the youngest female suicide bomber has been 7 years of age.

2 Jacob Zenn and Elisabeth Pearson, ‘Women, Gender and the Evolving Tactics of Boko Haram,’ Journal of Terrorism Research 5, no. 1 (2014): 46–57.

3 Mia Bloom and Hilary Matfess, ‘Women as Symbols and Swords in Boko Haram’s Terror,’ Prism 6, no. 1 (2016): 105–21; Hilary Matfess, Women and the War om Boko Haram: Wives, Weapons, Witnesses (London: Zed Books, 2017).

4 Jacob Zenn and Zacharias Pieri, ‘How Much Takfir is too much Takfir? The Evolution of Boko Haram’s Fictionalisation,’ Journal for Deradicalization 11 (2017): 281–308; Elizabeth Pearson, ‘Wilayat Shahidat: Boko Haram, the Islamic State, and the Question of the Female Suicide Bomber,’ in Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency, ed. Jacob Zenn (New York: Independently published by the Countering Terrorism Centre at West Point, 2018), 33–52.

5 Patience Ibrahim and Andrea C. Hoffman, A Gift From Darkness: How I Escaped With my Daughter From Boko Haram (London and Müchen: Little Brown, 2017); Wolfgang Bauer, Stolen Girls: Survivors of Boko Haram Tell Their Story (New York: The New Press, 2016); Helon Habila, The Chibok Girls (London: Penguin Books, 2016); Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, Buried Beneath the Baoada Tree (Katherine Tegen Books an imprint of Harper Collins, 2018); Edna O’ Brien, Girl (London: Faber and Faber, 2020); Christina Lamb, Our Bodies Their Battlefield: What War Does to Women (London: William Collins, 2020).

6 Dionne Searcey, In Pursuit of Disobedient Women: a Memoir of Love, Rebellion and Family, Far Away (New York: Ballantine Books, 2020).

7 In the context of this article, counter-terrorism is an action that encompasses both military and non-military responses.

8 It is not within the scope of this article to entertain the arguments of Boko Haram’s origins. For more see: Jacob Zenn, Unmasking Boko Haram: Exploring Global Jihad in Nigeria (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2020); Ona Ekhomu, Boko Haram: Security Consideration and the Rise of an Insurgency (CRC Press an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, 2020).

9 Alexander Thurston, Boko Haram: The History of an African Jihadist Movement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

10 Thurston, Boko Haram.

11 Thurston, Boko Haram.

12 Gbemisola Abdul-Jelil Animasawun, ‘Portents of a Fractured Boko Haram for Nigeria’s Counterterrorism Strategy and Tactics,’ chap. 9 in Understanding Boko Haram: Terrorism and Insurgency in Africa (London: Routledge, 2018),

13 Abdulabasit Kassim and Michael Nw Ankpa, eds., The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 71–5.

14 Kassim and Ankpa, The Boko Haram Reader, 75.

15 Yusuf died in July 2009. The exact circumstances pertaining to his death remain contested.

16 The author wishes to acknowledge that there are additional factors and narratives which have been used to explain the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria. It is not within the scope of this article to discuss all of the additional narratives. For an understanding of the additional narratives, see: Ojochenemi J. David, Lucky E. Asuelime and Hakeen Onapajo, Boko Haram: The Socio-Economic Drivers (New York: Springer, 2015); Olabanji Akinola, ‘Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria: Between Fundamentalism, Politics and Poverty,’ African Security, Online publication only (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2015.998539.

17 US Department of State, Buraru of Counterterrorism, ‘Forign Terrorist Originations,’ https://www.state.gov/foreign-terrorist-organizations/

18 Matfess, Women and the War on Boko Haram, 60.

19 J. Tochukwu Omenma, Ike E. Onyishi and Alyious-Michael Okolie, ‘A Decade of Boko Haram Activities: The Attacks, Response and Challenges Ahead,’ Security Journal 33 no. 2 (2020): 1–20.

20 Omenma, Onyishi and Okolie, ‘A Decade of Boko Haram Activities: the Attacks, Response and Challenges Ahead.’

21 Jacob Zenn, ‘Leadership Analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in Nigeria,’ CTC Sentinel 7, no. 2 (2014): 24.

22 Omar S. Mahmood and Ndubuisi Christian Ani, Factional Dynamics Within Boko Haram, ISS Research Report (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2018).

23 Bay’ah is an Islamic term meaning pledge of allegiance from a local or regional terrorist group to an international one. The terrorist group which receives the pledge becomes the parent organisation of the pledgee.

24 Virginia Comolli, ‘Boko Haram and Islamic State,’ in Jihadism Transformed: al-Qaeda and Islamic State’s Global Battle of Ideas, eds. Simon Staffell and Akil N. Awan (Hurst: London, 2016), 129–40.

25 David Otto (Director of the Anti-Terrorism Unit, Global Risk International), interview by Sven Botha, August 2020.

26 Pearson, ‘Wilayat Shahidat.’

27 It is not within the scope of this article to discuss the current state of ISWAP's leadership battles. For a full discussion see: Jacob Zenn, ‘Islamic State in West Africa Province's Factional Disputes and the Battle with Boko Haram,’ Terrorism Monitor 18, no. 6, https://jamestown.org/program/islamic-state-in-west-africa-provinces-factional-disputes-and-the-battle-with-boko-haram/

28 Helon Habila, The Chibok Girls (London: Penguin, 2016).

29 Helon Habila, The Chibok Girls.

30 Kassim and Nw Ankpa, The Boko Haram Reader.

31 Kassim and Nw Ankpa, The Boko Haram Reader.

32 Kassim and Nw Ankpa, The Boko Haram Reader.

33 Morgan Winsor and James Bwala, ‘More Chibok Girls Escape from Boko Haram Almost 7 Years Later, Parents Say,’ ABC News, January 29, 2021, https://abcnews.go.com/International/chibok-girls-escaped-boko-haram-years-parents/story?id=75560018

34 Timothy Obiezu, ‘More Than 100 Chibok Girls Still Missing Seven Years Later,’ Voice of America, April 15, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/africa/more-100-chibok-girls-still-missing-seven-years-later

35 International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram,’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4y0t1dyRwLo

36 International Crisis Group, Nigeria: Women and the Boko Haram Insurgency, Africa Report No 242 (Brussels: ICG, 2016).

https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-women-and-boko-haram-insurgency

37 Matfess, Women and the War on Boko Haram, 58.

38 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad: The Fate of Women Associated with Boko Haram, Africa Report No 275 (Brussels: ICG, 2019).

39 Emmanuel Bosah (Programme Manager of the Social Cohesion, Stabilisation and Reintegration Component, Neem Foundation), interview by Sven Botha, May 2019.

40 Jasmine Opperman (Director of Africa Operations, Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium), interview by Sven Botha, June 2019. At present, the only counter-narratives present at the time of this writing was provided by the Allamin Foundation for Peace and Development through radio programmes, but as the name of the provider suggests, the programme is organised by a civil society organisation.

41 Statista, ‘Literacy Rate in Nigeria in 2018, by Zone and Gender,’ https://www.statista.com/statistics/1124745/literacy-rate-in-nigeria-by-zone-and-gender/

42 Anneli Botha and Mahdi Abdile, Radicalisation and Boko Haram-Perception Versus Reality: Revenge as a Driver, the Role of the Female Soldiers, and the Impact of the Social Circle in Recruitment (Finland: The Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers, 2017).

43 Trading Economics, ‘Nigeria Unemployment Rate,’ https://tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/unemployment-rate

44 This currency conversion was done close to the relase of the final publication. As such, it may not be completly accurate when read after publication.

45 Valerie M. Hudson and Hilary Matfess, ‘In Plain Sight: The Neglected Linkage Between Brideprcie and Violent Conflict,’ International Security 42, no. 1 (2017): 7–40.

46 Jessica M. Davis, (Principle consultant, Insight Threat Intelligence), interviewed by Sven Botha, June 2019.

47 Opperman, interview; Akinola Olojo (Senior researcher, Transitional Threats and International Crime Programme, Institute for Security Studies), interviewed by Sven Botha, June 2019; Vesna Markovic (Associate professor of Justice, Law and Public Affairs, Lewis University), interviewed by Sven Botha, July 2019.

48 Alexis Leanna Henshaw, Why Women Rebel: Understanding Women’s Participation in Armed Rebel Groups (London, Routledge, 2017), 26.

49 ‘Marriage or Slavery? For Girls Abducted by Boko Haram, Suicide Bombing an Escape,’ The Mainichi, 4 April, 2018, https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20180404/p2a/00m/0na/006000c

50 ‘Marriage or Slavery?,’ 2018.

51 Rita Santacroce et al., ‘The New Drugs and the Sea: the Phenomenon of Narco-Terrorism,’ Journal of Drug Policy no. 51 (2018): 67–68.

52 Jason Warner and Hilary Matfess, Exploding Stereotypes: the Unexpected Operational and Demographic Characteristics of Boko Haram’s Suicide Bombers (New York: Independently published by the Countering Terrorism Centre at West Point, 2018), 35.

53 For a full discussion, please refer to: Mia Bloom, Bombshell: Women and Terrorism (Philadelphia: Philadelphia University Press, 2011).

54 Funmilayo Idowu Agbaje, ‘The Objectified Female Body and the Boko Haram Insurgency in Northeast Nigeria: Insights from IDP Camps in Abuja,’ African Security Review 29, no. 1 (2020): 3–19.

55 Bloom and Matfess, ‘Woman as Symbols and Swards.’

56 Vensa Markovic, ‘Suicide Squads: Boko Harm’s Use of the Female Suicide Bomber,’ Women and Criminal Justice 29, no. 4-5, A Special Issue on Gender and Terrorism (2019): 294.

57 Jason Warner, Ellen Chapin and Hilary Matfess, ‘Suicide Squads: the Logic of Linked Suicide Bombings,’ Security Studies 28, no. 1 (2019): 25–57.

58 Benjamin Maiangwa and Daniel Agbiboa, ‘Why Boko Haram Kidnaps Women and Young Girls in North-East Nigeria,’ Conflict Trends 3 (2014): 51–56.

59 Ibrahim and Hoffmann, A Gift From Darkness, 99.

60 Opperman, interview.

61 Zoë Friedland and Nicolle Richards, Countering Violent Extremism by Countering Stereotypes, A Report to the Under Secretariat for Civilian Security, Democracy and Human Rights, US Department of State (Stanford: Stanford Law School: Law and Policy Lab, 2015).

62 Bosah, interview.

63 Hamoon Khelghat-Doost, ‘The Strategic Logic of Women in Jihadi Originations,’ Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 42, no. 10.

64 Jacob Zenn, ‘Boko Haram and the Kidnapping of the Chibok Schoolgirls,’ Counter Terrorism Centre Sentential 7, no. 5 (2014): 1–7.

65 Olarewaju Kola, ‘Boko Haram Recruits Women to Spy, Attack,’ Anadolu Agency, July 17, 2014, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/boko-haram-recruits-women-to-spy-attack/140701

66 Paul Carsten and Ahmed Kingimi, ‘Islamic State Alley Stakes Out Territory Around Lake Chad,’ Reuters, April 29, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-security/islamic-state-ally-stakes-out-territory-around-lake-chad-idUSKBN1I0063

67 Matfess, Women and the War on Boko Haram, 80 and 81.

68 John-Mark Iyi, ‘The Weaponusation of Women by Boko Haram and the prospects of Accountability,’ in Boko Haram and International Law, eds. John-Mark Iyi and Hennie Strydom (Erfurt: Springer, 2018), 259–91.

69 Sola Ogundipe, Chioma Obinna & Gabriel Olawale, 4 May 2015, 'Boko Haram: 214 rescued girls pregnant – UNFPA', Vanguard, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2015/05/boko-haram214-rescued-girls-pregnant-unfpa/

70 Temitope B. Oriola, ‘“Unwilling Cocoons”: Boko Haram’s War Against Women,’ Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 40, no. 2 (2017): 99–121.

71 Iyi, Boko Haram and International Law, 2018.

72 Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Conflict Related Sexual Violence, Report of the United Nations Secretary-General, S\2019\280 (29 March 2019), https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf

73 Matfess, Women and the War on Boko Haram, 80 and 81.

74 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad.

75 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad, 6.

76 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad.

77 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad.

78 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad.

79 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad, 7.

80 Vanda Felbaba-Brown, The Limits of Punishment: Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism-Nigeria Case Study (Tokyo: United Nations University, 2018).

81 Felbaba-Brown, The Limits of Punishment, 2018.

82 International Crisis Group, Returning from the Land of Jihad.

83 International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram.’

84 Lamb, Our Bodies Their Battlefield, 2020.

85 The issue of insufficient access to healthcare is particularly prevalent among those returnees who were readily raped whilst with Boko Haram. In some cases, rape was so prominent that returnees suffered from fistula, a tear occurring between the vagina and the bladder or the rectum which meant that the sufferer would pass urine or faeces uncontrollably.

86 Sexual abuse within some IPD camps is rife. Members of the Nigerian military and the Joint Task Force have been accused of committing or aiding sexual abuse. See; Lamb, Our Bodies Their Battlefield, 2020; Amnesty International, ‘They Betrayed Us’: Women Who Survived Boko Haram Raped, Starved and Detained in Nigeria, https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/THEY-BETRAYED-US-WOMEN-WHO-SURVIVED-IN-NIGERIA.pdf

87 Opperman, interview.

88 International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram.’

89 International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram.’

90 One former female associate of Boko Haram noted that both her and her husband joined the group shortly after getting married ; she was eventually rescued by the Nigerian military to which her response was ‘The soldiers brought us back forcibly from Boko Haram, we would not have come back on our own.’ She further explains ‘I want to go back [to Boko Haram] because by husband is there.’ See International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram’.

91 International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram.’

92 International Crisis Group, ‘The Fate of Women Who Lived with Boko Haram.’

93 Stephen Buchanan-Clark and Peter Knoope, ‘The Boko Haram Insurgency: Form Short Term Gains to Long Term Solutions’ (Occasional Paper 23, Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, Cape Town, 2017), https://www.ijr.org.za/portfolio-items/the-boko-haram-insurgency-from-short-term-gains-to-long-term-solutions/; Igo Aghedo, ‘Old Wine in a New Bottle: Ideological and Operational Linkages Between Maitatsine and Boko Haram Revolts in Nigeria,’ in Understanding Boko Haram: Terrorism and Insurgency in Africa, eds. James J. Hentz and Hussein Solomon (London: Routledge, 2017), 65–84.

94 Popoola Michael and Omosebi Fredrick Adeola, ‘Dissecting the Nexus Between Sustainable Counter Insurgency and Sustainable Development Goals: Putting Nigeria in the Context,’ International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences 3, no. 5 (2018): 873–81.

95 Emeka Thaddues Njoku, ‘Politics of Conviviality? State-Civil Society Relations Within the Context of CounterterrorismCounterterrorism in Nigeria’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Originations (2017), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9910-9

96 Government of Nigeria, Terrorism Prevention (Amendment) Act of 2013, 29.

97 ‘Boko Haram: Nigeria Rolls-Out Soft Approach to CounterterrorismCounterterrorism,’ Premium Times, March 20, 2014, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/157111-boko-haram-nigeria-rolls-soft-approach-counterterrorismcounterterrorism.html

98 Government of Nigeria, Counter Terrorism in the Office of the National Security Advisor (Abuja: Office of the National Security Advisor, 2017).

99 United Nations Development Programme and International Civil Society, Invisible Women: Gendered Dimensions of Return, Rehabilitation and Reintegration From Violent Extremism, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ICAN_UNDP_Invisible_Women_Report.pdf

100 Invisible Women, 2019.

101 Invisible Women, 2019.

102 Bosah, interview.

103 Dr Fatima Akilu (Former Director of Behavioral Analysis and Strategic Communication and current Executive Director of the Neem Foundation), interviewed by Sven Botha, June 2020.

104 Aisha John Mark, ‘Nigeria Launches 2019 National Security Strategy Document,’ VON, December 4, 2019, https://www.von.gov.ng/nigeria-launches-2019-national-security-strategy-document/

105 the government of Nigeria, CounterterrorismCounterterrorism Centre, Office of the National Security Advisor, National Security Strategy (Abuja: Office of the National Security Advisor, 2019), https://ctc.gov.ng/national-security-strategy-2019/

106 There exists tension between northern and southern Nigeria whereby the former is envious of the latter’s developmental advances. In relation to the Boko Haram insurgency, this tension has resulted in southerners arguing that Boko Haram is the work of northern political elites to discredit the integrity of southern leaders. See: Daniel E. Agbiboa and Benjamin Maiangwa, ‘Nigeria United in Grief; Divided in Response: Religious Terrorism, Boko Haram and the Dynamics of State Response,’ African Journal of African Conflict Resolution 14, no. 1 (2014): 63–97.

107 Government of Nigeria, National Assembly of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Bill Tracker, Terrorism (Prohibition and Prevention) Bill (Abuja: National Assembly of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2019), https://www.nassnig.org/documents/bill/10412#

108 Buba, Interview.

109 Olumuyiwa Temitope Faluyi, Sultan Khan and Adeoye O. Akinola, Boko Haram’s Terrorism and the Nigerian State: Federalism, Politics and Policies (Cham: Springer, 2019).

110 Eugene Eji, ‘Rethinking Nigeria’s CounterterrorismCounterterrorism Strategy,’ The International Journal of Intelligence, Security and Public Affairs 18, no. 3 (2016): 198–220.

111 Eji, ‘Rethinking Nigeria’s CounterterrorismCounterterrorism Strategy.’

112 Amina Mama, ‘Khaki in the Family: Gender Discourses and Militarism in Nigeria,’ African Studies Review 41, no. 2 (Sep., 1998): 1–17; Sefina DogoSefina Dogo, ‘Understanding the Evolving Changes in the Nigerian Military from a Feminist Sociological Institutional Perspective,’ International Journal of Arts & Sciences 9, no. 2 (December 2016): 509–18.

113 Akilu, interview.

114 Candice D. Ortbals and Lori M. Poloni-Staudinger, Gender and Political Violence: Women Changing Politics and Terrorism (Cham: Springer, 2019).

115 Otto, Interview.

116 Fal-Dutra Santos, Interview.

117 Kemi Okenyodo, ‘The Role of Women in Preventing, Mitigating and Responding to Violence and Violent Extremism in Nigeria,’ in A Man’s Word? Exploring the Roles of Women in Countering Terrorism and Violent Extremism, eds. Naureen Chowdhury Fink, Sara Zeiger and Rafia Bhulai (Abu Dhabi: Hedayah and The Centre on Cooperative Security, 2016), 100–14.

118 Akilu, Interview.

119 The article by Emeka Njoku and Joshua Akintayo in this special issue is a good start to filling this gap in the literature.