ABSTRACT

Following the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the focus of many industrialised states has shifted regarding where they secure raw materials; a revised geopolitical perspective has impelled states to reduce strong dependencies on certain countries. For the European Union, its proposed Critical Raw Materials Act could have a crucial impact on the economic relationship of EU countries with China, currently the most important source of processed minerals to the EU, causing them to set ambitious diversification targets. How will this rise of a ‘new geopolitics’ of mineral supply chains shape the relationship between the EU and other trading partners, such as mineral-rich countries on the African continent? And how might African economies work to maximise their own benefit from this refocus? The article explores current geopolitical dynamics as they relate to the restructuring of supply chains, as well as opportunities for African economies.

Introduction

The demand for minerals and metals is likely to increase significantly, as the transition to renewable energy sources alone will require vast amounts of various raw materials.Footnote1 The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects the demand for minerals for green energy technologies to quadruple by 2040 in order to meet the targets of the UNFCCC’s 2015 Paris Climate Agreement; an even faster transition to achieve global climate neutrality by 2050 ‘would require as much as six times more minerals in 2040 than today’.Footnote2 The transitions in global mobility, digitalisation and other sectors may require different minerals as future technologies develop, but in any case it is clear that demand is rising.Footnote3 Even though recycling technologies are improving and intensive research is being carried out to find renewable substitutes for raw materials that are considered critical, these interventions are unlikely to meet global demand in the short to mid-term. Therefore, the mining sector will continue to play an important role.

For some time now, a shift away from the production of fossil fuels toward the extraction of several ‘green’ minerals has been observable. A significant part of these mineral deposits are on the African continent. In this context, a number of empirical studies have already investigated the potential of African economies to provide minerals for the energy transition.Footnote4

Since the beginning of the pandemic and with increasing intensity following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a politicisation of transnational supply chains that potentially will affect global trade relations can be observed. Following the end of the Cold War, the world saw a rapid increase of global trade, cross-border movement and trade integration that has been referred to as ‘hyper-globalisation’. This period was characterised by ‘the premise that cross-border trade and capital movements should be free from regulatory constraints and national industrial policies’.Footnote5 Among other effects, the global economic and financial crisis in 2008/2009 highlighted the massive scope of global interdependencies that had accrued by that time – and their risks. In response to the apparent challenges of a highly globalised, fragmented supply chain system, Gary Gereffi noted a trend towards ‘shifting end markets and the regionalization of value chains’,Footnote6 which had slowed down but not reversed globalisation.Footnote7

But the geopolitical developments between 2020 and 2023 – most notably the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine – could accelerate these changes. Each of these can be defined as an historical event: eg, ‘(1) a ramified sequence of occurrences that (2) is recognised as notable by contemporaries, and that (3) results in a durable transformation of structures’.Footnote8 At this time, it is still too early to assess what the long-term impact of current developments will be and whether two such pivotal historical events in succession might lead to fundamental changes in supply chains – or even to deglobalisation, defined as ‘a movement towards a less connected world’.Footnote9 While the literature does include articles that investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global value chains (GVC),Footnote10 so far only a few academic articles have investigated the potential long-term impacts of the Russian war on Ukraine on GVCs.Footnote11 However, a number of authors point to a clear shift towards industrial policies and more protectionist approaches in major economies, especially the US.Footnote12 The aim of this article is to investigate current dynamics in the field of mineral supply chains. Based on a substantive policy analysis of the frameworks in the field of mineral supply chains of different global actors, observations arising from key conferences in which the author was a participant, as well as from events and additional interviews with experts in the mining sector between 2021 and 2023,Footnote13 the article draws conclusions on the changing dynamics in these supply chains.

The policy analysis indicates that political decision-makers in the EU and in the US are changing their perspectives on GVCs and there is emerging a ‘new geopolitics’ of supply chains.Footnote14 Especially in the minerals sector, a shift away from a narrow focus on securing raw materials to a broader geopolitical perspective on supply chains is already apparent, with the aim of reducing dependencies on potentially risky partners. As a result, dependencies on China are under greater scrutiny because Beijing is a particularly dominant player in mineral supply chains. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has become the world’s most central manufacturing hub, connecting minerals exporters with countries that are highly dependent on mineral imports. Many industrialised countries in the EU, as well as the US, are aiming to reduce their dependence on China and have formulated political programmes aimed at establishing new supply relationships in the raw materials sector. The US, for its part, is taking a more assertive approach that aims at decoupling from China and rebuilding its own industrial policy.Footnote15 The EU approach can so far be characterised as ‘de-risking’ but going in a similar direction. While both the US and the EU intend to strengthen local extraction and processing, they also aim at building stronger trade relations in the mineral sector with countries in other world regions.

Due to its wealth of raw materials – especially those such as platinum or cobalt that are yet to be found in abundance in other world regions – the African continent is now in the spotlight. This is perceived critically by some actors, out of concern that a global ‘race for raw materials’Footnote16 might perpetuate existing global inequalities and dependencies as well as power imbalances.Footnote17 This article follows a second and more optimistic view. It argues that current geopolitical changes open a window of opportunity for African states to overcome existing export dependencies in the raw materials sector and to foster local value creation. African countries may use this rise of a new geopolitics of mineral supply chains and the competition between major economies to transform their extractive sectors in a direction that unlocks economic potential, creates local content in the mining sector and contributes to sustainable development. This transformation would also be in the interests of industrialised economies, because it has the potential to create both resilient and stable supply chains and is therefore an important element of security of supply, understood as the secure supply of those items that are in demand. The article aims to explore ways in which this can be achieved and to work out what course countries in the two regions can set in order to achieve a structural transformation that benefits both regions.

The article is structured as follows: The first section examines the changing geopolitical landscape and explores the new political context in the field of global supply chains. It looks at the emergence of a new geopolitics of mineral supply chains. The second section offers an empirical analysis of new raw materials policies in the US and Europe and investigates changing global dynamics. While the US has been in competition with China for some time now, the European perspective has changed since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It shows that a process of ‘policy diffusion’ – the ‘process by which policymaking in one government affects policymaking in another government’Footnote18 – can be observed in Europe with the aim of reducing major dependencies with potentially risky partners (‘de-risking’). In the context of mineral supply chains this means reducing dependencies on China. The third section explores the potential opportunities of these changing perspectives for African countries. It argues that resource-rich African economies should use this as a window of opportunity to move away from their role as mere suppliers of minerals, and explore opportunities in order to strengthen local value creation in and through the minerals sector. African states can create the conditions for this move not only through the development of industrialisation strategies at the national level, but also through increased integration within the regional economic communities (RECs) on the continent and at the African Union (AU) level. The article argues that such increased integration of African states in mineral supply chains must be accompanied by a push for sustainability and good governance in transnational supply chains. It shows that states can play a far greater role in shaping the mining sector than has been the case to date. The article concludes with an outlook on the future of mineral supply chains.

Geopolitical context: The emergence of a new geopolitics of mineral supply chains

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacies and the risks of economic and political dependencies in a globalised world, while also highlighting the unequal distribution of power in international relations. Shortages in the supply of non-essential goods during the pandemic have initiated a debate on production lines, supply routes and stockpiling of critical goods all over the world, not only in the health sector but also in other sectors.Footnote19 As a consequence, this has led to strategic discussions on the role of specific regions in global supply chains, their dependencies on other regions and the associated risks of each, as well as on the necessity to reshape global supply chains.

‘Reshoring’ and ‘nearshoring’ as a response to the pandemic

After the first shock of the pandemic and related lockdowns, which entailed responses on a national level,Footnote20 a more regionalised response to the pandemic can be observed. During this time, the strategic concepts of ‘reshoring’ and ‘nearshoring’ were gaining importance for actors in the EU or in the US. While ‘offshoring’ is the process of ‘outsourcing operations overseas, usually by companies from industrialised countries to less-developed countries, with the intention of reducing the cost of doing business’,Footnote21 reshoring is movement of operations in the opposite direction. Reshoring means to ‘bring production back into the country – or at least in its proximity – or at least some slices of the value chain’.Footnote22 ‘Nearshoring’ is often used to refer to the relocation of production to a more proximate region, for example when US companies are relocating their operations from China to Mexico.Footnote23 While offshoring, nearshoring and reshoring are strategies that are directly pursued at a company level – at least in liberal economies – states can set incentives to encourage companies to pursue a certain strategy.

Discussions about more state-led approaches to incentivise companies to reshore or nearshore had already emerged when the housing market crisis in the US led to the global financial crisis in 2008/2009 and exposed the vulnerabilities of interconnected markets.Footnote24 This represented a possible departure from the multilateral and globalised economic model and was therefore investigated critically, especially by economists because of the potential negative impacts on emerging markets and developing countries and their integration in global supply chains.Footnote25 Neither concept was put in practice. At the same time, Gabriel Felbermayr and Holger Görg observe a ‘Slowbalisation’Footnote26 – a term that was created by The Economist in 2019 in order to describe the slowdown of globalisation.Footnote27 Up to a certain extent, the US presidential administrations of Barack Obama (2008–2016) and Donald Trump (2016–2020) were pursuing nearshoring and reshoring strategies as a reaction to the increasing role of China in global supply chains. The aim was to help companies relocate their production back to the US in order to strengthen the industrial weight of the US economy and to contribute to job creation in the US.Footnote28 These efforts, and the deterioration of relations between the US and China, have intensified from 2019 onwards, leading to a de-integration of trade relations between the two countries.Footnote29

For the EU the goal of ‘strategic autonomy’ – ‘the capacity of the EU to act autonomously’ – in strategic sectors of the economy had gained momentum over this period, especially in light of the increasing US-Sino ‘trade war’ during the Trump presidency; this goal was eventually put on the political agenda with the start of the pandemic in 2020.Footnote30 This led to the formulation of various political proposals within the EU in order to strengthen European autonomy in the field of critical resources.Footnote31 The pandemic was seen to have not only revealed ‘the materiality of human activity and complex geographies of inequity’, it had also ‘highlighted how inequalities embedded in relations of production, reproduction of global finance continue to perpetuate the divide between the Global North and the Global South’.Footnote32

The strong orientation towards regional economic security had a negative impact on global cooperation. The European export ban on personal protective equipment (PPE),Footnote33 the hoarding of vaccines in the ‘Global North’, and the refusal of many countries to support the proposal by India and South Africa to support a temporary waiver for vaccines further revealed the unequal distribution of power and resources.Footnote34 At the same time, it also highlighted the limits of the multilateral order to deal with geopolitical challenges.

While at the time of writing there is no strong evidence of deglobalisation as a response to the pandemic, this may be because it might be too early to evaluate these impacts empirically. Florian Butollo and Cornelia Staritz argue that the pandemic has the potential to reinforce the formation of ‘multipolar production and consumption structures’. In this context, increased regionalisation is one possibility – among many – that has not yet been empirically proven. At the same time, global supply structures are complex. While greater regionalisation is conceivable in some areas, it may not play a role in others. Butollo and Staritz therefore rightly oppose a simple dichotomy between globalisation and deglobalisation. But changing political programmes could lead to the formation of ‘regional blocs’.Footnote35 Cooperation at the European level is a good example: ‘despite Brexit, European integration proved to be resilient during the health crisis’.Footnote36

On the African continent, the debate on regional development within the AU has made considerable progress. While the launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) was postponed due to the pandemic and then scheduled for the beginning of 2021, the discussion on the implementation of the AfCFTA has progressed significantly by 2023. With the development of the AfCFTA, member states of the AU intend to ‘create a single market’, and ‘to enable the free flow of goods and services across the continent and boost the trading position of Africa in the global market’.Footnote37 The hope is that regional cooperation could make African states strategically independent.Footnote38 Since 2021, the institutional structure of the AfCFTA has been further developed. Questions concerning the concrete technical design of regional integration and the search for common visions and policies are at the centre of discussions on the African continent.

‘Friendshoring’ as a reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

Following soon after the worst of the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is the second ‘historical event’ to have a massive influence on international relations and geopolitical developments in the current period. In the meantime, an increasing politicisation of supply chains can be observed as well as a shift away from understanding ‘security of supply’ as a purely economic challenge to an understanding that focuses on strategic partnerships.

In this context, and in response to broader economic developments globally, geopolitical competition between the US and the EU and China and Russia has intensified. This competition is reflected in the emergence of the new paradigm of ‘friendshoring’, which was introduced by the US in 2022 as a concept in the context of the debate on the future of supply chains. ‘Friendshoring’ refers to the development of economic relationships with ‘a network of trusted suppliers from friendly countries that offer multiple independent supply paths’. In this sense, the concept combines the development of economic cooperation with the expansion of political relations with countries that share similar norms and values.Footnote39 Günther Maihold in 2022 described this as the ‘new geopolitics of supply chains’; in this context, companies must not only respond to economic calculations, but must also pay greater attention to political or geopolitical objectives.Footnote40

Some economists have criticised this concept of ‘friendshoring’, arguing that it is hardly feasible because a number of products are not available in all countries of the world, and certain supply chains have already been established.Footnote41 Others note that it would cause massive economic losses worldwide,Footnote42 while still others question the concept because it ‘generates risks of political blackmail and economic coercion’.Footnote43 From the perspective of political science, one can add to the list of criticisms that the concept is very vague and is not backed up with clear criteria, eg, democratic orientation or regime stability. The question of who is a friend or ally thus remains a very vague one, as these might be defined differently by the US or the EU – and even between member states of the EU.

Nevertheless, European states are increasingly embracing friendshoring as a political concept.Footnote44 The serious economic consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on European states have changed the political calculations in these countries. Germany has been especially hard hit economically by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent EU sanctions on the importation of Russian goods, since it had been relying heavily on imports of Russian gas.Footnote45 This has brought a new focus of political attention on the risks of a one-sided economic dependence on certain countries that are perceived as risky or unreliable partners. While this has not resulted in a radical upheaval in supply chains (yet), a tendency toward reducing strong dependencies on these countries by diversifying supply chains through new partnerships can be observed.Footnote46

In the minerals sector this has been backed up with concrete policy programmes. In March 2023, the EU presented the proposed Critical Raw Materials Acts (CRMA). The draft proposal sets ambitious targets for the increase of domestic capacities and diversification of its supply chains. Apart from the increase of domestic capacities for extraction, recycling and processing, it sets ambitious targets for 2030 with regard to its imports: not more than 65% of the EU’s annual consumption of each strategic raw material at any relevant stage of processing should come from a single third country.Footnote47 These programmes aim to reduce dependencies on China, which as noted above is a particularly important player in mineral supply chains. While this offers opportunities across many regions, the focus of this article is on the two neighbouring continents of Africa and Europe.

The geopolitical structure of mineral supply chains and the role of China

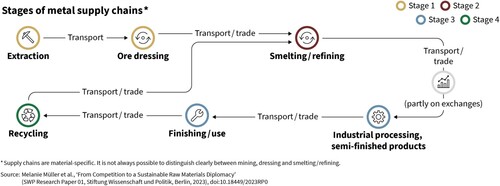

Mineral supply chains can be divided broadly into four stages (see ). The first stage concerns the extraction, ie, the mining of ore which is either conducted in underground or open-pit mines, but can also be carried out through less formalised methods of artisanal mining. The second stage is the refining process, ie, where ores are further processed to industrially usable minerals. In the third stage, these industrially usable products are then further processed and built into products. A fourth and final step would be that of recycling, whereby minerals are retrieved through new processes, with the purpose of reusing them.Footnote48

Figure 1. Stages of metal supply chains*.

*Supply chains are material specific. It is not always possible to distinguish clearly between mining, dressing and smelting/refining.

Source: Melanie Müller et al., ‘From Competition to a Sustainable Raw Material diplomacy’ (SWP Research Paper 01, Stifung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2023), doi:10.18449/2023RPO.

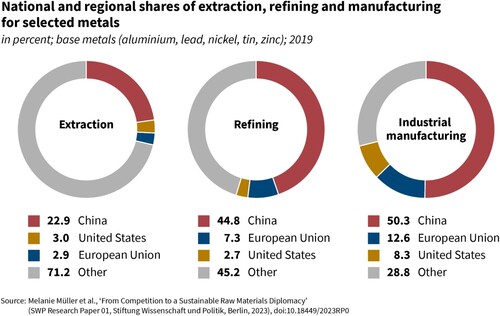

In addition to this technical structure, mineral supply chains are characterised by a certain geopolitical structure which has continued to solidify in the past two decades. Africa and Europe are currently only distantly connected in these supply chains: African actors are located at the stage of extraction, while European companies are largely located at the third stage of the supply chain – and are therefore highly dependent on imports of minerals and metals. The US, in contrast, is more integrated into commodity supply chains, especially since some American companies are also active in mining whereas according to the EU Commission ‘only a few countries in Europe have active mines’,Footnote49 and European mining hasn’t contributed much to the global production of metals and industrial minerals.Footnote50 Hence, the most important actor in the supply chains of minerals is China, because it has become the global centre of smelting and refining.Footnote51 (See ).

Figure 2. National and Regional shares of extraction, refining and manufacturing for selected metals in percent; base metals (aluminium, lead, nickel, tin, zinc); 2019.

Source: Melanie Müller et al., `From Competition to a Sustainable Raw Material diplomacy’ (SWP Research Paper 01, Stifung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2023), doi: 10.18449/2023RPO.

shows the share of extraction, refining and manufacturing of four selected base metals (aluminium, lead, nickel, tin and zinc) by China, the EU, the US, and other states. For other minerals, these shares might differ. But fundamentally, the selection reflects the geopolitics of mineral supply chains.

Since the 1990s, the Chinese government has expanded the influence of Chinese companies in various mineral supply chains and built up its capacities in the midstream as well as in the downstream process of minerals. This was a strategic decision by China, clearly aiming at becoming more integrated into global supply chains.Footnote52 China’s ‘going-out’ strategy allowed Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to make investments in strategically important sectors. Prioritised access to finance and the reduction of bureaucratic barriers have helped Chinese SOEs and private companies penetrate new markets outside China ever since.Footnote53 Another important element is China’s ‘Grand Diplomacy’ approach that aims to build soft power globally, and with partner countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).Footnote54

While mining does not play a significant role in China itself, Chinese companies are involved in all stages of mineral supply chains; Chinese investments flow directly into the extraction of minerals and metals in various countries.Footnote55 Chinese companies have built up strategic networks in the mining sector in targeted states, in order to ‘develop organizational capacity through joint ventures and acquiring human resources from the international market’.Footnote56

In this context, the approach of ‘infrastructure-for-minerals’ between China and resource-rich countries was developed. Chinese state-owned banks or other commercial actors provide resource-rich countries with favourable loans for infrastructure development. These are often designed as resource-backed-loans, in which repayment takes place in the form of commodity deliveries or resource-related income streams. Sometimes, there are legal claims on mining licences, or resources serving as collateral.Footnote57 Frequently, the contracts also foresee Chinese companies as contractors for infrastructure projects. This was a crucial step in order to increase investments by Chinese companies in key resource-rich countries in Africa and Latin America.Footnote58

As part of this strategy, China has expanded its cooperation with African countries. According to the CLA (Chinese Loans to Africa) Database, Chinese state-owned banks, private financial institutions and Chinese companies have provided at least $18 billion worth of loans to African countries for mining projects between 2000 and 2017, among them $17.6 billion to Angola.Footnote59 On top of that, China also has made strategic infrastructure investments with its Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI was launched in 2013 with the goal to expand infrastructure connectivity for free trade and to improve political communication. The project also aims at establishing and expanding economic cooperation in various sectors. By March 2022, 148 countries worldwide had joined the BRI as partners.Footnote60 Hereby, the expansion of mining infrastructure plays a central role. One important aspect of this cooperation is the enlargement of (African) transport infrastructure: the development of streets, ports and railway networks in order to transport minerals from different regions to China. Especially in the minerals sector, where large quantities of ores often need to be transported by land or sea, this physical connectivity is a central element of security of supply.Footnote61

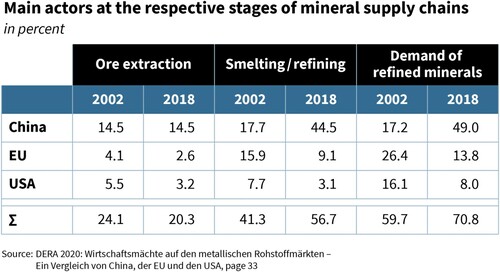

These developments explain why China has managed to further expand its role as the most important country for smelting and refining over the past 20 years. China’s key strategic advantage in international markets is that it has located global smelting and refining production of key critical metals on its own ground. As a result, the supply chains of many minerals and metals pass through China.Footnote62 In 2021, China was the world’s largest producer of refined products with high sourcing risk, accounting for a 93% market share.Footnote63 This makes the country a central trading partner both for countries where extraction takes place as well as for countries needing processed minerals for their industrial production. , from the German Mineral Resources Agency (DERA), illustrates China’s impressive increase in global refining production between 2002 and 2018.

Figure 3. Main actors at the respective stages of mineral supply chains, in percent.

Source: DERA 202: Wirtschaftsmächte auf den metallischen Rohstoffmärkten – Ein vergleich von China, der EU und den USA, page 33.

Challenging China: The risk of ‘West-Shoring’

Whereas the US still hosts some of the biggest global mining companies and has started to invest again in domestic mining (see below), the EU has significantly cut down domestic mining production over the past 20 years. European countries thus play only a marginal role in the first two stages of mineral supply chains. They are greatly dependent on Chinese imports of refined minerals and metals – for certain metals the important dependency is 75%, or even as high as 100%.Footnote64

Until the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the US and the EU pursued different political priorities with regard to securing supply of minerals and metals, which Jane Nakano summed up in 2021 as follows:Footnote65

The United States appears most concerned about import dependence that can be exploited geopolitically, while the European Union and Japan appear primarily concerned with the effects of supply chain disruptions on their industrial competitiveness.

Since 2022, the risk of excessive dependence on China in the minerals sector is apparently being perceived more clearly in European countries, as well.Footnote68 This has led to policy diffusion between European countries, as well as to a more regionalised response on the challenges in mineral supply chains, the EU CRMA being the latest and most rigorous policy proposal – and an approach driven by both the French and the German governments. These two major European economies have already formulated national responses. At the beginning of 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron nominated a national commission chaired by Philippe Varin, a French businessman who – together with some of the biggest French companies – identified the mineral demands of these industries.Footnote69 Germany went through a similar process. In January 2023, the German Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action presented strategic pillarsFootnote70 to complement the previous raw materials strategy, formulated in 2010 and updated in 2020.Footnote71 With the introduction of the CMRA, the EU demonstrates its intent to connect the German and French strategy with other European countries, thereby increasing coordination between European member states.

The EU approach thus far, as articulated in the draft of the CMRA, is based on several pillars. The clear objective is to achieve greater diversification of minerals material supply chains, reducing dependence on China while at the same time avoiding a decoupling from China, which is perceived as neither politically desirable nor realistic. Rather, the EU – in contrast to the US – is pursuing a moderate strategy in dealing with China, which the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, described as ‘de-risking’.Footnote72 Thereby, the focus is increasingly on those minerals where dependence on China is particularly high. One pillar of the EU diversification strategy is increased European inter-regional cooperation. This means, on the one hand, potential relocation of mining and refining operations to European countries. On the other hand, the EU aims at increasing cooperation between EU member states to use synergies and financial resources to invest in the re-localisation of supply chains in third countries, outside China. It also intends to set up an EU export credit facility to back up investments abroad.Footnote73

The EU is in the process of either establishing or negotiating ‘raw materials partnerships’ with countries worldwide. The EU Commission also announced plans to use financial instruments such as the ‘Global Gateway’ initiative more intensively to secure minerals projects.Footnote74 The Global Gateway initiative is the ‘EUs new connectivity strategy that aims to create smart, sustainable and secure links with countries around the world in thematic areas of digital, energy and transport’.Footnote75 It can be regarded as a tool to compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

It also becomes clear that in addition to policy diffusion at the European level, a policy diffusion from other industrialised ‘Western’ states – from the US but also Japan – can also be observed. Even if the motives of the EU and the US differ and they are each underpinned differently, their diversification strategies in the field of mineral supply chains are very similar. These strategies are both based on an approach that the Japanese government has now been following for almost 20 years. Japan established the Japan Oil, Gas, and Metals National Cooperation (JOGMEC) in 2004. JOGMEC is a state-owned company aimed at supporting Japanese companies that are dependent on minerals and metals. It provides loans and credits for these companies in order to secure access to minerals and metals, eg, by concluding offtake agreements.Footnote76 In the field of mineral supply chains, members of the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, the US and the EU) have intensified cooperation. At the preparatory meeting of the G7 in Sapporo in April 2023, the countries presented a ‘Five Point Plan for Critical Mineral Security’.Footnote77

In addition, most of these states in June 2022 joined together in the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), an initiative aiming to ensure security of supply in mineral supply chains and to ‘help catalyze investment from governments and the private sector for strategic opportunities – across the full value chain – that adhere to the highest environmental, social and governance standards’.Footnote78 Resource-rich Scandinavian states as well as Australia and the Republic of Korea are partner countries to the MSP. This already shows a strong coordination of states in the West that also have an interest in increasing mining and processing in their regions.

There is a risk that these efforts of different countries are being reduced to a strong focus on Western cooperation – a process that the article will term ‘West-Shoring’ – which may exclude states in Africa. During the 2023 Mining Indaba in South Africa, African states were invited to cooperate within the MSP framework,Footnote79 but they must take initiative to ensure a take-up of these and other emerging opportunities. It is to Africa’s role that discussion now turns.

Emerging opportunities for African countries

In the context of these initiatives in the minerals sector, the African continent has come under greater political scrutiny. At the global level, geopolitical competition over the access to minerals is increasing.Footnote80 Even though Western states are currently coordinating very strongly, the respective actors are also looking for concrete bilateral partnerships. Here in particular, stronger coordination between the two neighbouring continents of Europe and Africa offers an opportunity. European countries have become increasingly aware that they must create incentives for African countries if they want to seriously challenge China’s strategic role in mineral supply chains.Footnote81 Since the start of the Russian war on Ukraine, this pressure has increased. The need for resilient supply of minerals is key to the energy transition towards renewables as well as for the production of green hydrogen, which has become a priority of the EU to address the energy crises and create an alternative to Russian gas.

Increasing bargaining power for the African Union

One way of looking at this increased geopolitical competition is to frame it as a ‘new scramble for Africa’, with a particular focus on the potential risks.Footnote82 From a historical perspective, such a view is plausible: price fluctuations have had a negative impact on countries that are highly dependent on minerals exports; the unequal distribution of profits leads to conflicts in mining regions; mechanisation of extraction has a negative impact on job creation; and further processing of minerals – with a few exceptions – still takes place in other world regions.Footnote83 At the same time, the geopolitical competition can be regarded as a window of opportunity for African states to promote the integration of the continent into mineral supply chains and improve their governance performance in the mineral sector. Because global supply chains are not subject to market logic only, but are shaped by political actors and their decisions, a stronger coordination of African states at the level of the AU could improve their bargaining positionFootnote84 and create the necessary conditions to capitalise on opportunities that might otherwise prove evasive.

While some studies have advocated for a stronger focus on the role of institutions in global value chains,Footnote85 some recent analysis also investigates the role of the AfCFTA.Footnote86 While these focus on different policy areas, most studies conclude that greater regional coordination among African states could further strengthen their bargaining power in the current geopolitical situation. The Economist in 2019 summed it up as follows: ‘The scramble for Africa. This time, the winners could be African themselves’.Footnote87 In the minerals sector, the current geopolitical competition offers a chance to overcome the role of resource-rich countries in the region as mere suppliers of minerals. As the Policy Centre for the New South puts it:Footnote88

One main challenge to the mining sector in Africa is that the clear majority of resource exports leave the continent unrefined. However, some countries are ratcheting up efforts to build linkages between mining and manufacturing, such as by the construction of cement factories. Roughly 12% of the new investments in South Africa are targeted towards processed minerals.

So far, however, many academic studies on the implementation of the AMV remain rather critical, even from authors who support the objectives of the AMV.Footnote91 In particular, these have focused on the need for development and expansion of downstream processing in the mining sector.Footnote92 The mining sector in Africa in particular is often criticised as an ‘enclave economy’ because there are few economic linkages to other sectors and, even within mining, there are only a few players to benefit from economic development. Some countries, eg, Ghana, Liberia, Mozambique or South Africa, have implemented local content policies that aim at unlocking further economic potential and at building their downstream industries.Footnote93 Studies dealing with the implementation of these promising policies find, however, that international power relations in the extractive sector, which have developed over a long period of time, as well as competition between some African states in the minerals sector and the dominance of a few large companies, have so far made it difficult to resolve the challenges these policies identify.Footnote94

It is suggested that the national efforts noted above may hinder more coordinated action at the AU level. The implementation of the AfCFTA offers on opportunity to explore potential intra-African cooperation within the framework of regionalisation strategies.Footnote95 The mining sector is particularly suitable for this type of regional cooperation, characterised by the fact that there are many related sectors in which jobs may be created and value added. African policies would ideally be designed to take advantage of these different opportunities to link resource extraction with other economically productive areas, through a regionally-cooperative approach.

Firstly, ‘backward’ or ‘upstream’ linkages include research and development activities as well as the production of equipment and technology and the expansion of infrastructure essential for extraction activities. This area creates opportunities for local suppliers to enter the value chain, as their existing contextual knowledge enables them to develop solutions adapted to local and regional conditions. Secondly, value can be increased through downsteam’ linkages. This is largely achieved through processing and refining of minerals (beneficiation) in smelters and refineries, but also through recycling processes. Because these activities are highly energy-intensive, a larger share of profits can be achieved at the next stage of the value chain, in product manufacturing, ie, through the production of batteries or battery components. Thirdly, value can be added by coupling the minerals sector with other sectors. Synergies between the mining and agricultural sectors can be created for instance, through the development of (sustainable) energy sources that can provide energy for both sectors. To avoid redundancies in infrastructure provision, the two industries could cooperate in motivating for the improvement of roads that can be used by both sectors to improve delivery of their products.Footnote96

The African Development Bank (AfDB), in cooperation with the African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC), is already in the process of formulating a green minerals strategy for the African continent, based on the investigation of these potential synergies.Footnote97 The aim is to identify different linkages in the various regions in order to help African countries add value to their extractive sector.Footnote98 A very important task is to create the necessary technical conditions. In this context, exploration is the key to being able to estimate the mineral reserves on the continent. The deposits of certain minerals differ considerably between countries and regions, which also has an impact on economic competitiveness. This requires large-scale geological surveys but also the development of digitalised minerals cadastre systems that are handled transparently and provide regional role-players, including companies, with a quick overview of geological capacities of the respective states. The Mining Association of Southern Africa (MIASA), during a conversation at the German-Africa Business Summit in Johannesburg in December 2022, highlighted the improvement of cadastre systems as one of the most important priorities for countries in the Southern African Development Community, in order increase competitiveness.Footnote99

A joint African position could also increase the bargaining position in negotiations on trade agreements, so that the AU could push for a reduction in tariffs on processed minerals.Footnote100 Yao Graham summed this up in a recent discussion on minerals and Africa’s development:Footnote101

Whether it is in the WTO, or negotiations with the EU on the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), BITs and even the Africa Continental Free Trade Area, there is a disconnect between the aspirations expressed in the AMV agenda by African governments and the international trade and investment policies they persist with and the international relations they enter into. It is true that the international climate has not been supportive but there does not seem to be much learning from the lessons of trade and investment policies offered by the experiences of the other countries especially the newly industrialized countries of the global South.

Regional approaches instead of national competition

In recent years, the regional economic communities (RECs) have also investigated the potential effects of greater collaboration on regional economic development through the mining sector. In the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region, the SADC Regional Mining Vision, as well as the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan and the Industrialisation Strategy and Roadmap (2015–2063) are examples of strategies and plans aimed at expanding local value creation in the mining sector. However, a comprehensive analysis of the objectives of the SADC member states makes it clear that harmonisation of local content requirements (LRC) has not yet been achieved, and thus potentials in the minerals sector remain untapped.Footnote103 With the new geopolitics, new opportunities are emerging here, particularly in the area of the energy transition and the mobility transition.

Analyses by the AfDB as well as other research show that the production of components of batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) offers great potential for Southern Africa, as it requires minerals that are located in the region, eg, lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel and graphite.Footnote104 The EU lists these minerals as ‘critical minerals’ – minerals that are strategically important for European companies, but have high supply chains risks. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has increased pressure on car makers in Europe and in the US, since some of the minerals were sourced and some components were produced in the Ukraine. This has led to shortages in the production of batteries for electric vehicles.Footnote105

Various countries in the region have already reacted to these changing dynamics. In April 2022, the governments of Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) announced that they intend to develop the production of lithium-ion batteries in a bilateral cooperation project.Footnote106 The so-called Copper Belt, one of the largest copper deposits in the world, runs through both countries; cobalt, which is a critical component for the production of batteries, is obtained as a by-product of copper production.Footnote107 With the bilateral agreement both countries intend to scale-up production and locate the processing of minerals closer to the sites of extraction. The Zambia-DRC Battery Council has plans for the production of battery precursors, batteries and electric vehicles. Both countries intend to establish a special economic zone and are in the process of exploring the economic potential. The project is supported by the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), but also by the US government.Footnote108

The Zimbabwean government made headlines in December 2022, when it announced that it would ban the export of raw lithium and only export material that had been processed locally. It is estimated that Zimbabwe has one of the biggest lithium reserves in Africa. According to estimates, Zimbabwe could cover 20% of the global lithium demand. Currently, the Zimbabwean government is exploring which locations are suitable for on-site lithium production.Footnote109 The ‘Mines to Energy Industrial Park’, currently under construction, is part of this strategy and is supposed to start energy production in 2023. The project is part of an agreement between the Zimbabwean government and Chinese investors (Eagle Canyon International Group Holding Limited and Pacific Goal Investments) that aims at increasing energy production for the Zimbabwean economy by making use of its raw materials.Footnote110

Also in late 2022, South Africa presented its investment plan for the ‘Just Energy Transition Partnership’ (JETP). JETPs can be described as ‘country platforms for the support of energy transitions in developing countries’. In the South African case, a consortium of donors – Germany, France, the UK, the US and the EU – have mobilised about $8.5 billion in order to support South Africa’s energy transition.Footnote111 One of the key elements of the South African JETP is the planned production of electric vehicles. Production is initially intended for export markets, as the demand for EVs within South Africa is latent. In parallel, South Africa wants to expand local infrastructure for EVs so that vehicles can also be produced for the local market in the future.Footnote112

Through increased cross-country coordination, there is potential to use these synergies between SADC countries. In a comprehensive study from 2020, Deon Cloete outlined the potential for stronger cooperation in the SADC region to increase large-scale EV production.Footnote113 Even though this is a rather medium- to long-term perspective, the course for it should be set now, especially since industrial actors have also expressed their support for the development of a regional beneficiation strategy for the SADC region.Footnote114

More opportunities to increase local content should be identified for areas of production and for the coupling of the mineral sectors with other sectors. There is no one-size-fits-all solution for countries facing opportunities; linkages must be explored specifically for different sectors, since they are also linked to economic and political factors, to infrastructure, and to skills and capacities. Plans to develop the required infrastructure, and to provide education and training, must be incorporated early into these discussions.Footnote115

Sustainable governance of minerals

For this to succeed, the implementation of good and sustainable governance in the minerals sector is key. The ‘new geopolitics of mineral supply chains’ is accompanied by rising expectations regarding the sustainable transformations of supply chains. Increasingly, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria play a significant role in European and international initiatives in the minerals sector. This goes hand in hand with the emergence among EU member states of legal instruments with an extraterritorial impact on supply chains across the globe. While voluntary commitments in supply chains tended to dominate in the period from 2010 until around 2017, a trend towards stronger regulation by European actors can be observed. Several European countries – among them major economies such as France and Germany – have adopted supply chain legislation which will oblige companies of a certain size and based in these countries to identify human rights risks in their own supply chains, for instance. This has an impact not only on these companies directly, but also affects their immediate suppliers.Footnote116 The EU Commission is currently working on a directive that in its scope is very likely to go even further than national supply chains laws.Footnote117

This has increased the pressure on multinational companies from the demand side. Gwamaka Kifukwe describes the potential of an EU supply chain law as follows:Footnote118

For the EU’s partners, this would be a powerful mechanism to enhance the positive effects of multinationals’ business practices and curb the negative ones. It would help ensure that corporate activities align with the EU’s development goals in good governance and anticorruption.

In addition, mineral governance in African states needs to focus on improving mining conditions at the stage of extraction, where human rights and sustainability risks are high, in order to identify potential risks at this early stage and thus avoid violations of ESG criteria in the first place. Many African countries have already set high standards in the mining sector. However, there are major problems with the implementation and enforcement of these standards.Footnote121 Risks include environmental risks – such as water and air pollution – but also the violation of the rights of local communities, for example when conflicts arise over the use of land in the vicinity of mines. This creates risks for the right to health or may affect the right to a clean environment and access to clean water.Footnote122 Many conflicts between mining companies and communities have been documented in recent years, including in African countries.Footnote123

The international pressure on multinational mining companies to implement ESG criteria has significantly increased in the past decade The ‘Marikana massacre’ in South Africa in 2012Footnote124 led to an intense transnational debate about the co-responsibility of companies in Europe such as BASF in Germany, which imported platinum from the company owning the Marikana mines, Lonmin.Footnote125 In this context, attention for the responsibilities of large and transnationally active mining companies with a central position of power in supply chains has increased. More and more of the bigger mining companies have formulated and implemented ESG criteria in recent years. At the three last Mining Indabas in Cape Town, ESG in the mining sector was one of the top priorities.Footnote126

At the same time, critical assessments of the mining sector in recent years show that voluntary ESG governance arrangements are in many cases insufficient to improve conditions on the ground, even though more and more companies – and governments – in the extractive sector are trying to change operations in line with the calls for a ‘social license to operate’ (SLO).Footnote127 A study by the Responsible Mining Foundation (RMF) looking at ESG performance of the most important mining companies globally also reveals that they are failing to engage with stakeholders at the local level to get a better understanding of the risks that these actors perceive:Footnote128

The vast majority of the 250 assessed mine sites across 53 countries cannot demonstrate that they are informing and engaging with host communities and workers on basic risk factors such as environmental impacts, safety issues or grievances. Some 94% of the mine sites score an average of less than 20% on the fifteen basic ESG issues assessed.

Greater state action to enforce ESG within mining presupposes, of course, that governments are willing to improve their governance in the minerals sector. Gavin Hilson rightly criticises the discussion around AMV for being rather blind to the challenges:Footnote130

No one seemed to question the logic behind asking heads of state, many of whom have deliberately kept sections of mineral-rich Africa poor by marginalizing their citizenries, to design and oversee the implementation of a mining-led development manifesto with ‘good governance’ at its core.

Without a social contract and a social license to operate, it has become increasingly difficult for governments and companies to continue mining operations.Footnote132 Increasing international regulation via due diligence laws with extraterritorial obligations will most likely continue to grow in the coming years. In the past, this has often been accompanied by negative economic consequences for the mining sector.Footnote133 At the same time, recent studies on the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation, which has been in force since 2020, show that policymakers have also learned from these experiences. They are supporting legal approaches to regulating supply chains, including flanking measures and holistic governance approaches that aim at supporting companies as well as governments that are affected by supply chain laws.Footnote134 In this regard, there is leeway for African countries to become more active by setting and implementing their own standards and by exerting greater influence on the design of ESG.

Conclusion

The analysis shows that the geopolitical upheavals of recent years have the potential to affect the structure of mineral supply chains in the medium- to long-term. Even though supply chains have always been subject to change due to the vagaries of international markets, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have potential for a much more profound impact; they have affected the way political and economic actors in major economies look at the structure of global supply chains, especially with regard to the need to diversify supply.

The current uncertainties on a geopolitical level should be regarded as a window of opportunity for African actors because they are shaking up structures in mineral supply chains. This offers a chance to advance the integration of resource-rich African economies into mineral supply chains. African states should use this chance to position themselves more actively than before as central actors in mineral supply chains. They can proactively counteract the risk of a ‘West-Shoring’ by increasing African coordination and bringing forward their own proposals.

One prerequisite to increasing local value creation is the formulation of ambitious and at the same time realistic industrial policies – these seem to be seeing a resurgence in certain countries since the pandemic and the Russian war on Ukraine.Footnote135 In a number of African states, a critical debate about the pathway to industrialisation and the role of natural resources already exists, and more coordination between African institutions is already visible. A number of states have already formulated national local content policies, and the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC) are taking up a more proactive role. However, various studies show that the situation will require serious efforts by African states to challenge established transnational structures in the raw materials sector and to compete with well-established companies. For this to succeed, intra-African cooperation needs to be explored to a greater extent within the framework of regionalisation strategies, especially in the framework of the AfCFTA. In addition, there are also more opportunities to better leverage synergies within RECs to better advance AMV goals on a sub-regional level. This will require the willingness of individual states and, at the same time, a commitment to good governance in the mining sector, which is key to unlocking Africa’s potential. Increased cooperation of African states within the AU can increase bargaining power in international negotiations and thus also help to unsettle the balance of power in the raw materials sector. The development and expansion of downstream processing in the mining sector and sectoral linkages could not only help to increase value added, but ultimately also to reduce African economies' heavy dependence on other regions.

A more strategic approach does not require taking sides in a geopolitical competition. On the contrary, and particularly to unlock investment for industrial strategies and to expand the transport and the energy infrastructure, there is an opportunity to work with different partners and to better explore offers for cooperation. But it remains important for African actors to introduce African proposals and thus increase agency at an international level. Ultimately, the current juncture in geopolitics and in mining is an opportunity to establish regional standards and to shape sustainability in supply chains.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Melanie Müller

Melanie Müller is a Senior Associate with a focus on Southern Africa at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP) in Berlin and head of two research projects with a focus on mineral supply chains. She has been working on political and social developments in South Africa since 2011. Melanie Müller has also conducted research in other countries of the SADC region and in Niger and Ghana and has published extensively on the political and socioeconomic developments in Southern Africa, on resource governance and migration, as well as on European-African relations.

Notes

1 Daniele La Porta Arrobas et al., ‘The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future (English)’ (working paper 117581, World Bank, Washington DC, 2017), https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/207371500386458722/the-growing-role-of-minerals-and-metals-for-a-low-carbon-future.

2 International Energy Agency, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, flagship report (Paris: IEA, 2021), https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions.

3 Frank Marscheider-Weideman et al., ‘Rohstoffe für Zukunftstechnologien 2021’ (Commissioned Study, Deutsche Rohstoffagentur, Berlin, 2021).

4 Antonio Andreoni and Simon Roberts, Geopolitics of Critical Minerals in Reneweable Energy Supply Chains (Briefing, African Climate Foundation, Cape Town, 2022), https://africanclimatefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/800644-ACF-03_Geopolitics-of-critical-minerals-R_WEB.pdf; Caitlin McKennie, Al Hassan Hassan and Mama Nissi Abanga Abugnaba, ‘Africa’s Energy Transition & Critical Minerals’ (Commentary, Payne Institute for Public Policy, Illinois, 2022).

5 Robert Kuttner, ‘After Hyper-Globalization,’ The American Prospect. Ideas, Politics, Power, May 2022, https://prospect.org/economy/after-hyper-globalization/.

6 Gary Gereffi and Joonkoo Lee, ‘Why the World Suddenly Cares About Global Supply Chains,’ Journal of Supply Chain Management 48, no. 3 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2012.03271.x

7 Olivier Cattaneo, Gary Gereffi and Cornelia Staritz, ‘Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World: Resilience, Consolidation and Shifting End Markets,’ in Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World: A Development Perspective, ed. Olivier Cattaneo, Gary Gereffi and Cornelia Staritz (Washington DC: World Bank, 2010), 18.

8 William H. Sewell, ‘Historical Events as Transformations of Structures: Inventing Revolution at the Bastille,’ Theory and Society 25, no. 6 (1996): 844.

9 Markus Kornprobst and John Wallace, ‘What is Deglobalization?’ Chatham House, October 2021, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/10/what-deglobalization.

10 Sébastien Miroudot, ‘Reshaping the Policy Debate on the Implications of Covid-19 for Global Supply Chains,’ Journal of International Business Policy 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00074-6

11 Henry S. Gao, ‘China and Global Trade Order Post Ukraine War: From Value Chains to Values Chains’ (May 7, 2022), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4117763; Tobias Korn and Henry Stemmler, ‘Russia’s War on Ukraine Might Persistently Shift Global Supply Chains,’ in Global Economic Consequences of the War in Ukraine, ed. Luis Garicano, Dominic Rohner and Beatrice Weder di Mauro (London: Center for Economic Policy Research, 2022); Ebru Orhan, ‘The Effects of the Russia – Ukraine War on Global Trade,’ Journal of International Trade, Logistics and Law 8, no. 1 (2022); Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Hendrik Mahlkow, and Alexander-Nikolai Sandkamp, ‘Cutting Through the Value Chain: The Long-Run Effects of Decoupling the East from the West’ (working paper 9721, CESifo, 2022), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4097847; Zaheer Allam, Simon Elias Bibri, and Samantha A. Sharpe, ‘The Rising Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine War: Energy Transition, Climate Justice, Global Inequality, and Supply Chain Disruption,’ Resources 11, no. 11 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11110099

12 Pinelopi Goldberg and Tristan Reed, ‘Is the Global Economy Deglobalizing? And if So, Why?’ Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, March 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/BPEA_Spring2023_Goldberg-Reed_unembargoed.pdf.

13 The article was developed within the framework of the research project ‘Transnational Approaches for Sustainable Commodity Supply Chains’ at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP). The project is funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) in Germany. For the project, 130 interviews were conducted with experts, political decision-makers, business actors and civil society in the mining sector. Participatory observation took place within the framework of different events.

14 Günther Maihold, ‘A New Geopolitics of Supply Chains: The Rise of Friend-Shoring’ (Comment 45, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2022), https://doi.org/10.18449/2022C45

15 Michael A. Witt et al., ‘Decoupling in International Business: Evidence, Drivers, Impact, and Implications for IB Research,’ Journal of World Business 58, no. 1 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101399; Ren Yuxiang and Wang Weimin, ‘US. Decoupling from China: Strategic Logic, Trend and Measures,’ The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology 4, no. 12 (2022).

16 Viktoria Reisch, ‘The Race for Raw Materials’ (Journal Review 1, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2022), https://doi.org/10.18449/2022JR01

17 Jason Hickel et al. ‘Imperialist Appropriation in the World Economy: Drain from the Global South through Unequal Exchange, 1990–2015,’ Global Environmental Change 73 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102467; Hannes Warnecke-Berger, Hans-Jürgen Burchardt and Rachid Ouaissa, ‘Natural Resources, Raw Materials, and Extractivism: The Dark Side of Sustainability’ (Policy Briefing 1, Extractivism, 2022); Sulaimon Muse and Abedeen Babatunde Suluka, Globalization and Inequality in Africa: The Way out of the Current Challenges (SSRN, 2022), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4104853; Hanri Mostert et al., A Win-Win for Europe & Africa: Extractive Justice and Resource Interdependency, research report (South African Institute of International Affairs, 2019).

18 Fabrizio Gilardi, Charles R. Shipan and Bruno Wüest, ‘Policy Diffusion: The Issue-Definition Stage,’ American Journal of Political Science 65, no. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12521

19 Günther Maihold, ‘A New Geopolitics of Supply Chains.’

20 Steven M. Radil, Jaume Castan Pinos and Thomas Ptak, ‘Borders Resurgent: Towards a Post-Covid-19 Global Border Regime?’ Space and Polity 25, no. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2020.1773254

21 Christopher O’Leary, Offshoring, Encyclopedia Britannica Money, https://www.britannica.com/money/offshoring.

22 Carlo Pietrobelli and Cecilia Seri, ‘Reshoring, Nearshoring and Developing Countries: Readiness and Implications for Latin America,’ UNU-MERIT (working papers no. 003, UNU-MERIT), https://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/wppdf/2023/wp2023-003.pdf, p. 2.

23 Pietrobelli and Seri, Reshoring, Nearshoring and Developing Countries.

24 Olivier Cattaneo, Gary Gereffi and Cornelia Staritz, ‘Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World: Resilience, Consolidation and Shifting End Markets,’ in Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World: A Development Perspective, ed. Olivier Cattaneo, Gary Gereffi and Cornelia Staritz (Washington DC: World Bank, 2010), 18.

25 Gabriel Felbermayr and Holger Görg, ‘Die Folgen von Covid-19 für die Globalisierung,’ Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik 21, no. 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1515/pwp-2020-0025

26 Felbermayr and Görg, ‘Folgen von Covid-19.’

27 Weekly Edition, ‘Slowbalisation: The Future of Global Commerce,’ Economist, January 24, 2022, https://www.economist.com/weeklyedition/2019-01-26

28 James McBride, Andrew Chatzky and Anshu Sirirapu, ‘What’s Next for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)? Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-trans-pacific-partnership-tpp.

29 Eddy Bekers and Sofia Schroeter, ‘An Economic Analysis of the US-China Conflict,’ World Trade Organization Economic Research and Statistics Division, March 2020, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd202004_e.pdf.

30 Xosé Somoza Medina, ‘From Deindustrialization to a Reinforced Process of Reshoring in Europe. Another Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic?’ Land 11 (2022): 4, https://doi.org/10.3390/land11122109

31 Mario Damen, ‘EU Strategic Autonomy 2013–2023. From Concept to Capacity’ (EU Strategic Autonomy Monitor, European Parliament, Brussels, July 2022).

32 Sara Stevano et al., ‘Covid-19 and Crisis of Capitalism: Intensifying Inequalities and Global Responses,’ Canadian Journal of Development Studies 42 (2021): 1, https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2021.1892606

33 Mark P Dallas, Rory Horner and Lantian Li, ‘The Mutual Constraints of States and Global Value Chains during COVID-19: The Case of Personal Protective Equipment,’ World Development 139 (2021): 7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105324

34 Bawa Singh et al., ‘COVID-19 and Global Distributive Justice: “Health Diplomacy” of India and South Africa for the TRIPS Waiver,’ Journal of Asian and African Studies (2022), https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211069652

35 Florian Butollo and Cornelia Staritz, ‘Deglobalisierung, Rekonfiguration oder Business as Usual? Covid-19 und die Grenzen der Rückverlagerung globalisierter Produktion,’ Berliner Journal für Soziologie 32 (2022): 396, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-022-00479-5

36 Federico Fabbrini, ‘Brexit and the Future of European Integration,’ EU3D Research Paper No. 17, August 2021, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3909924.

37 African Continental Free Trade Area, ‘Purpose of the AfCFTA,’ https://au-afcfta.org/purpose-the-afcfta/.

38 Vera Songwe, Jamie MacLeod and Stephen N Karingi, ‘The African Continental Free Trade Area: A Historical Moment for Development in Africa,’ Journal of African Trade 8, no. 2 (2021): 13, https://doi.org/10.2991/jat.k.211208.001

39 William D. Eggers, Beth McGrath and Mike Canning, Government Trends 2022. Building Resilient, Connected, and Equitable Government of the Future (Deloitte Insights, 2022), 20.

40 Günther Maihold, ‘Geopolitics of Supply Chains.’

41 Rahul Guhathakurta, ‘Friendshoring: Logic, Focused Sectors and Skepticism’ (December 12, 2022), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4281545.

42 Beata S. Javorcik et al., ‘Economic Costs of Friend-Shoring’ (working paper 274, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, December 2022), https://www.ebrd.com/documents/oce/economic-costs-of-friendshoring.pdf.

43 Rahul Guhathakurta, ‘Friendshoring.’

44 For example: EU Commission, ‘Strategic Foresight Report 2022’ (Brussels: European Union, 2022), 23, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/strategic-planning/strategic-foresight_en

45 Rüdiger Bachman et al, ‘What if Germany is Cut Off from Russian Energy?’ Centre for Economic Policy Research 2022, 94–101, https://cepr.org/system/files/2022-09/172987-global_economic_consequences_of_the_war_in_ukraine_sanctions_supply_chains_and_sustainability.pdf#page=104.

46 EU Commission, Strategic Foresight Report 2022 (Brussels: European Union, 2022), 23, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/strategic-planning/strategic-foresight_en.

47 EU Commission, ‘Critical Raw Materials: Ensuring Secure and Sustainable Supply Chains for EU’s Green and Digital Future,’ March 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1661.

48 Melanie Müller et al., ‘From Competition to a Sustainable Raw Materials Diplomacy’ (SWP Research Paper 01, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2023), doi:10.18449/2023RP0.

49 European Commission, Metallic Minerals, 2023, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/related-industries/minerals-and-non-energy-extractive-industries/metallic-minerals_en.

50 Magnus Ericsson, ‘Changing Locus of Mining,’ Mineral Economics 35 (2022): 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00303-9.

51 Adnan Mazarei and Luc Leruth, ‘Green Energy Depends on Critical Minerals. Who Controls the Supply Chains?’ Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, October 11, 2022, https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/10/11/green-energy-depends-on-critical-minerals-who-controls-the-supply-chains/.

52 Gao, ‘Value Chains to Values Chains.’

53 Ligang Song, ‘State-Owned Enterprise Reform in China: Past, Present and Prospects,’ in China’s 40 Years of Reform and Development: 1978–2018, ed. Ligang Song, Ross Garnaut, and Cai Fang (ANU Press, 2018), 345–74; Randall W. Stone, Yu Wang, and Shu Yu, ‘Chinese Power and the State-Owned Enterprise,’ International Organization 76, no. 1 (2022): 229–50, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000308; Denghua Zhang and Jianwen Yin, ‘China’s Belt and Road Initiative, from the Inside Looking Out,’ The Interpreter, July 2, 2019, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-s-belt-road-initiative-inside-looking-out

54 Zheng Yognian and Zhang Chi, ‘The Belt and Road Initiative and China’s Grand Diplomacy,’ China and the World 01, no. 03 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1142/S2591729318500153.

55 Jane Nakano, The Geopolitics of Critical Minerals Supply Chains (Washington DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2021).

56 Fang Lee Cooke et al., ‘Mining with a High-End Strategy: A Study of Chinese Mining Firms in Africa and Human Resources Implications,’ International Journal of Human Resource Management 26, no. 21 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1071863.

57 David Mihalyi, Aisha Adam and Jyhjong Hwang, ‘Resource-Backed Loans: Pitfalls and Potential,’ Natural Resource Governance Institute, 2020, https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/resource-backed-loans-pitfalls-and-potential.pdf.

58 Deborah Bräutigam and Kevin P. Gallagher, ‘Bartering Globalization: China’s Commodity-Backed Finance in Africa and Latin America,’ Global Policy 5, no. 3 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12138; Hongsong Liu, Yue Xu and Xinzu Fan, ‘Development Finance with Chinese Characteristics: Financing the Belt and Road Initiative,’ Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 63 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329202000208.

59 Global Development Policy Center (Chinese Loans to Africa Database), database, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/chinese-loans-to-africa-database/.

60 Zia Ur Rahman, ‘A Comprehensive Overview of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Implications for the Region and Beyond,’ Journal of Public Affairs 22, no. 1 (2022): 3, https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2298; Christoph Nedopil, ‘Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative’, Shanghai, Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University, 2023, https://greenfdc.org/countries-of-the-belt-and-road-initiative-bri/

61 Michael Mitchell Omoruyi Ehizuelen, ‘More African Countries on the Route: The Positive and Negative Impacts of the Belt and Road Initiative,’ Transnational Corporations Review 9, no. 4 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2017.1401260; Nancy Muthoni Githaiga et al., ‘The Belt and Road Initiative: Opportunities and Risks for Africa’s Connectivity,’ China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 5, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740019500064.

62 Yun Schüler-Zhou, Bernhard Felizeter and Ann Katrin Ottsen, Einblicke in die Chinesische Rohstoffwirtschaft. DERA Rohstoffinformationen (Berlin: Deutsche Rohstoffagentur, 2019).

63 Siyamend Al Barazi et al., DERA-Rohstoffliste 2021. Angebotskonzentration bei Mineralischen Rohstoffen und Zwischenprodukten – Potenzielle Preis- und Lieferrisiken (Berlin: Deutsche Rohstoffagentur, 2021), 5.

64 European Commission Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, 3rd Raw Materials Scoreboard: European Innovation Partnership on Raw Materials (Publications Office, 2021).

65 Jane Nakano, Critical Minerals Supply Chains.

66 White House, Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force to Address Short-Term Supply Chain Discontinuities (Washington DC: The White House, June 8, 2021).

67 Jenna Trost and Jennifer B. Dunn, ‘Assessing the Feasibility of the Inflation Reduction Act’s EV Critical Mineral Targets,’ Nature Sustainability, March 2023, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-023-01079-8.

68 European Commission, ‘Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on the preparation of the European Council meeting of 23–24 March 2023,’ speech, March 15, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_1672; European Commission, ‘Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on the conclusions of the European Council meeting of 23–24 March 2023,’ speech, March 29, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_1949

69 Philippe Varin, ‘Nous Devons Développer une Véritable Diplomatie des Métaux,’ Service Géologique National, https://www.brgm.fr/fr/actualite/interview/philippe-varin-devons-developper-veritable-diplomatie-metaux.

70 Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, Eckpunktepapier: Wege zu einer Nachhaltigen und Resilienten Rohstoffversorgung (Berlin: BMWK, 2023).

71 Bundesregierung, Rohstoffstrategie der Bundesregierung. Sicherung einer Nachhaltigen Rohstoffversorgung Deutschlands mit Nichtenergetischen Mineralischen Rohstoffen (Berlin: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2019).

72 Speech by President von der Leyen on EU-China relations to the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the European Policy Centre on March 30, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_2063.

73 European Commission: Critical Raw Materials Act, 2023, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials/critical-raw-materials-act_en.

74 ‘Rohstoffpartnerschaften: EU setzt auf Global Gateway,’ TableEurope, December 7, 2022, https://table.media/europe/news/rohstoffpartnerschaften-eu-setzt-auf-global-gateway/.

75 Chloe Teevan et al., ‘The Global Gateway: A Recipe for EU Geopolitical Relevance?’ (discussion paper 33, Center for Africa-Europe Relations, June 13, 2022), https://ecdpm.org/work/global-gateway-recipe-eu-geopolitical-relevance.

76 Hanns Günther Hilpert, ‘Japan,’ in Fragmentation or Cooperation in Global Resource Governance? A Comparative Analysis of the Raw Materials Strategies of the G20, ed. Hanns Günther Hilpert and Stormy-Annika Mildner (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2013), 100.

77 G7 Minister’s Meeting on Climate, Energy and Environment: Five-Point Plan for Critical Minerals, April 2023, https://www.env.go.jp/content/000127541.pdf.

78 US Department of State, ‘Minerals Security Partnership,’ Juni 2022, https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership/.

79 US Department of State, ‘Media Note,’ February 2023, https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership-governments-engage-with-african-countries-and-issue-a-statement-on-principles-for-environmental-social-and-governance-standards/.

80 Andreoni and Roberts, ‘Geopolitics of Critical Minerals.’

81 Interviews with German and EU political decision-makers, as well as with researchers in France.

82 Jobson Ewalefoh, ‘The New Scramble for Africa,’ in The Palgrave Handbook of Africa and the Changing Global Order, ed. Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba and Toyin Falola (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77481-3_15.

83 See for example Tony Addison and Alan Roe, Extractive Industries: The Management of Resources as a Driver of Sustainable Development, 1st ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198817369.001.0001.

84 Evelyn Shumba, ‘What the AfCFTA Means for the Mining Sector,’ The Exchange Africa’s Investment Gateway, March 31, 2021, https://theexchange.africa/tech-business/what-the-afcfta-means-for-the-mining-sector/.

85 ‘Special Issue: New Perspectives on Global Value Chains: Bringing Institutions Back in’ Global Policy 9, no. 2 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12627.

86 Ilaria Fusacchia, Jean Balié and Luca Salvatici, ‘The AfCFTA Impact on Agricultural and Food Trade: A Value Added Perspective,’ European Review of Agricultural Economics 49, no. 1 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbab046; Andrew Mold, Kasim Ggombe Munyegera and Rodgers Mukwaya, ‘What Trade-in-Value Added Databases Tell us about Continental Integration – And what it Means for the AfCFTA’ (paper, 25th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis, Virtual Conference, 2022); K Banga et al., ‘Africa Trade and Covid-19: The Supply Chain Dimension’ (working paper 586, Organização Mundial da Saúde, 2020).