Abstract

Background: Hemophilia A (HA) and B (HB) are common bleeding disorders, Iran having the ninth largest such population in the world. A considerable number of studies have been performed on different aspects of their disorder.

Objective: The aim of the study was to gather all obtainable data about Iranian patients with HA and HB, including molecular studies, clinical presentations and treatment, and development and management of patients with inhibitor, to help better understand the disease and its management in other parts of the world.

Methods: For this review study, we searched MEDLINE and Scientific Information Database for English and Persian sources until 2015.

Results and discussion: There are 5369 patients with HA and HB in Iran among which 4438 patients have HA. About one-fifth of HA patients' genes were analyzed and their underlying defects detected. Hemarthrosis, epistaxis, ecchymosis, and post-dental extraction bleeding are the most common clinical presentations. Bleeding was mainly managed by on-demand replacement therapy with factor VIII/factor IX (FVIII/FIX) concentrates or cryoprecipitate in HA, and fresh frozen plasma in HB in the absence of factor concentrate. Mean per capita for FVIII in HA patients is 1.56 IU, which is higher than the global per capita mean. However, mean per capita for FIX (0.24 IU) is lower than the global mean but highest among eastern Mediterranean countries. Replacement with plasma-derived components has led to infection in a large number of patients as well as inhibitor development against exogenous infusion of coagulation factors. According to a World Federation of Hemophilia survey, 223 HA and 6 HB patients in Iran have developed inhibitor and have been mainly managed by recombinant FVII (rFVIIa) and activated prothrombin-complex concentrate.

Conclusion: Although this study was performed in Iranian patients, the large number thereof gives confidence that the results can be used more widely for other countries, especially in the developing world.

Introduction

Hemophilia A (HA) and B (HB) are X-linked recessive hemorrhagic disorders resulting from mutations in factor VIII (FVIII) and IX (FIX) genes, respectively. FVIII and FIX participate in the intrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade. Different types of mutations, including point mutation, large and small deletion and inversion, can inactivate or reduce the activity of the affected factor.Citation1–Citation3 Eighty percent of cases are classical hemophilia (HA). HA is the most common inherited hemorrhagic disorder, with an incidence of 1 per 5000 males in the general population; HB has a prevalence of 1 per 30 000 males.Citation3–Citation5 Based on factor activity, hemophilia is divided into three groups, severe (<1%), moderate (1–5%), and mild (>5–30%).Citation5 The intensity of bleeding is dependent upon severity of the disease such that, in severe hemophilia, spontaneous bleeding occurs predominantly in soft tissues, joints, and muscles, while patients with mild or moderate hemophilia show post-trauma or post-surgery bleeding. Replacement therapy with factor concentrate is used for controlling the bleeding episodes.Citation3–Citation6 The immune response against therapeutic concentrate can lead to antibody (inhibitor) development. About 30% of patients with severe HA develop FVIII inhibitors due to replacement therapy.Citation7 Inhibitor development is the most important complication of treatment.Citation7 The incidence of inhibitors depends on several factors such as ethnicity, family history, HLA complex genotype, gene mutations, age at first treatment, intensity of treatment, and continuous infusions.Citation8,Citation9

Iran has a great number of patients with hemophilia; based on population, it has one of the highest global incidences. A considerable number of studies, performed on different aspects of Iranian patients with hemophilia from 2001 to 2015, have been published in English and Persian languages. In this study, we aimed to gather all data thereof, to make accessibility of these data easier, and extract valuable clinical and laboratory data from a large cohort that can help better the understanding and management of the disease elsewhere.

Prevalence of hemophilia in Iran

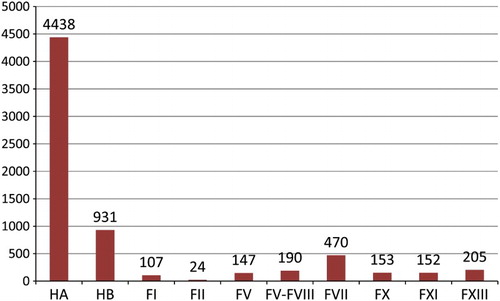

A survey by World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) in 2014, in 107 countries, identified 176 211 people with hemophilia (A and B), 140 313 of whom had HA. Based on this survey, Iran, with 5369 patients, has the ninth largest hemophilia population, in 2014, 4438 had HA and 931 had HBCitation10 (Fig. ).

Figure 1 Prevalence comparison of hemophilia with rare bleeding disorders in Iran (WFH 2013 survey).Citation10 FI, factor I; FII, factor II; FV, factor V; FV-FVII, combined factor V and factor VIII; FVII, factor VII; FX, factor X; FXI, factor XI; FXIII, factor XIII.

A wide spectrum of studies have been conducted on Iranian hemophilia patients, as summarized in Table (below). While the number has been determined, the precise distribution across the provinces has not. Tehran Province had 1288 identified hemophilia patients, of whom 1077 had HA. As patients were from various areas of Iran there may be some overlap among the studies. After exclusion of patients with incomplete medical files, 1047 remained for further analysis. There were 885 (84.5%) HA patients and 162 (15.5%) HB patients, among whom 27 (3.1%) HA and 6 (3.7%) HB patients were female. The majority of patients showed the severe form (<1%) of disease.Citation11 Approximately 20% of Iran's population lives in Tehran Province, a melting pot of ethnicities. Therefore, data of hemophilia patients in this province provide us with a valuable estimate for the whole country. Prevalence in this province is 14 per 100 000 and 2.5 per 100 000 males, of HA and HB, respectively.Citation11

Table 1 Number of patients with hemophilia in different parts of IranCitation11–Citation17

In northwestern Iran, a total of 138 patients were identified: 120 (87%) HA and 18 (13%) HB.Citation12 A study on Khorasan Razavi Province, which has a large number of bleeding disorders, revealed 287 HA and 92 HB patients, a prevalence of 10.29 per 100 000 and 3.30 per 100 000 males, results roughly similar to Tehran Province.Citation11,Citation13 Most HA and HB patients had the severe form of disease, including 143 (49.8%) for HA and 43 (46.7%) for HB.Citation13 Until 2007, the number of patients with HA and HB in southern Iran was 326 and 46, respectively.Citation14 In Sanandaj city, of Kurdistan Province, a total of 104 HA patients were reported.Citation15 A study on a large number of patients (1280) with HA echoed other results: almost half of Iranian hemophilia patients had the severe form of the disease.Citation16

Diagnosis of hemophilia in Iran

In Iran, diagnosis is based on data collection and laboratory assessment. Since bleeding diathesis is similar among several coagulopathies, a full family history is useful for differential diagnosis. After examination of symptoms, clinical presentation, and a detailed family history, an appropriate laboratory approach is used. Initially, Iranian patients suspected of hemophilia are assessed by routine coagulation tests, notably activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), prothrombin time (PT), bleeding time (BT), and thrombin time.Citation17,Citation18 Although measurement of vWF:Ag is worthwhile for differential diagnosis in patients with HA and von Willebrand disease (VWD), this test is not routinely performed on all Iranian patients. The pattern of bleeding in hemophilia is mostly in deep tissue, joints, and muscles; mucosal and gastrointestinal bleeding is more common in VWD. However, clinical presentation is not sufficient for differential diagnosis as type III VWD with a very low level of FVIII activity and absent VWF multimers may present with severe bleeding such as hemarthrosis. Therefore a vWF:Ag assay is fundamental for differential diagnosis and should be considered in all cases.

Moreover, patients with isolated decrease in FVIII activity should be assessed precisely to exclude type 2N VWD, because such cases can easily be misdiagnosed as mild HA.Citation17,Citation18

Prolonged APTT with normal PT and BT is a valuable finding in HA and HB. This is especially valuable when our patient is male with bleeding. In Iranian patients, measurement of factor activity is the final step for confirmation of disease and classification of disorder, based on residual factor activity in plasma. According to international standards, patients with HA and HB are classified into mild (>5–30%), moderate (1–5%), and severe (<1%).Citation14 A mixing test is carried out to rule out patients having inhibitor. In this test, patient's plasma is mixed with normal pooled plasma and APTT is repeated. A prolonged APTT (mixing test) is followed by a quantitative assay in order to determine the inhibitor titer. Although Nijmegen assay is the recommended method for inhibitor assay by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, most Iranian coagulation laboratories use the Bethesda assay.Citation15,Citation19 Owing to the large size of FVIII, and to some extent FIX, genes, and genetic diversity in these genes, molecular diagnosis is not routinely performed for diagnosis or carrier detection in Iran. Genetic analysis imposes high costs on patients and the healthcare system. Clinicians get a relatively reliable diagnosis based on factor activity, clinical presentation, and family history; they feel less of a need to conduct genetic assessment. However, a number of genetic studies have been performed as part of research into carrier detection.Citation13,Citation18

Molecular studies in patients with hemophilia in Iran

In spite of the large number of patients, only a few studies were performed to determine the underlying gene defects. The most important molecular study on Iranian patients was performed on 588 unrelated HA patients in the Iranian Comprehensive Haemophilia Care Centre (ICHCC). This is a referral unit for all Iranian hemophiliacs. This study identified 580 mutations, demonstrating inversion of intron 22 and intron 1 in 201 (42.6%) and 5 (1.2%) severely affected individuals, respectively (Table ). Another valuable study, also performed at ICHCC, determined the prevalence of common gene defects, including inversion of intron 22 and intron 1 in 146 patients with HA (124 with the severe form). Inversion of intron 22 and intron 1 were not observed in any of 22 patients with mild and moderate forms of HA, while these two common gene defects were observed among 49 (39.5%) and 2 (1.5%) severely affected patients, respectively. This study also indicated that a large number of Iranian patients with severe HA (58%) had sporadic HA.Citation23

Table 2 Spectrum of FVIII gene defects among Iranian patients with HACitation20–Citation22

A multi-country study, with Iran's participation, molecularly analyzing 199 Iranian patients with mild, moderate, and severe HA, showed similar results. As expected, these defects were not observed in patients with mild and moderate HA. All 18 patients with mild HA had missense mutations, 26 moderately affected patients had missense mutation, and 2 had small deletion/insertion.Citation21 The common approach in ICHCC, as the only comprehensive unit for mutation detection in hemophilia patients, is assessment of intron 22 and intron 1 inversion as well as pre-screening conformation-sensitive gel electrophoresis (CSGE) followed by direct sequencing of defective exons detected via this procedure.Citation24 All exons of the FVIII gene were sequenced in cases in which defective exons were not detected. In a study on 11 unrelated families, in which 10 families failed to give one or more exons after PCR amplification, as well as in another family, not only was heteroduplex not observed by CSGE but direct sequencing of all exons failed to determine the underlying gene defect. The first ten families were suspected of having a large deletion and the remaining family was suspected of having exon duplication; the study confirmed this.Citation24

Molecular analysis of 56 HA patients from southern Iran led to identification of underlying gene defects in 41. As in previous studies, inversion of intron 22 was the most common gene defect (21 severe HA patients). Unlike in previous studies, inversion of intron 22 was observed in two patients with moderate HA. Inversion of intron 1 was not detected in any of these patients.Citation22 Other studies have been distributed in different parts of the country; a number of them were performed for carrier detection with simple and less expensive methods.Citation25–Citation29

As with HA, molecular studies on HB patients have been rarely performed. Only a small number of Iranian patients were analyzed for underlying gene defects.Citation30–Citation33 A number of these studies are summarized in Table .

Table 3 Spectrum of FIX gene defects among Iranian patients with HBCitation30–Citation33

Missense mutation is the most common finding in Iranian HB. In the majority of studies, this type of mutation comprises more than half of the observed genetic defects. Nonsense mutation is another common mutation, observed in a considerable number of patients.Citation30,Citation31 No recurrent mutation useful for carrier detection in different ethnicities was observed, although prenatal diagnosis was performed for a few families. In fact, molecular analysis of HB revealed a high degree of heterogeneity in HB genetic defects.Citation30

Clinical presentation of patients with hemophilia in Iran

Iranian patients with hemophilia show a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Most common are hemarthrosis, ecchymosis, epistaxis, and post-dental extraction. Central nervous system (CNS) and umbilical cord bleeding are rare in these patients (Table ). CNSB is less common in patients with hemophilia and its associated morbidity and mortality are infrequent in hemophilia patients.Citation13,Citation34 In a study on 214 patients with mild (No: 25), moderate (No: 32), and severe (No: 157) forms of the disease, nine patients with the severe form (4.2%) experienced intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). Among these, six (67%) had head trauma while three (33%) experienced spontaneous ICH. Entrapment neuropathy was observed in ten patients.Citation35,Citation36

Table 4 Clinical presentations of a number of Iranian patients with HA and HBCitation11,Citation13

Treatment of patients with hemophilia in Iran

The high number of patients with hemophilia imposes enormous costs on the Iranian healthcare system. All Iranian hemophilia patients are covered by national insurance and replacement therapy is provided free of charge.Citation37 The Iranian government annually pays about sixty million dollars for hemophilia drugs.Citation38 Based on a WFH survey in 2010, HCCC is a comprehensive center, presenting a wide spectrum of facilities for diagnosis and management of patients with inherited bleeding disorders. Until 2010, Iran had 29 Hemophilia Treatment Centres providing basic facilities for diagnosis and management,Citation39 whereas there was no such laboratory in Iran in the mid-1960s.Citation40 For replacement therapy in Iran, a variety of high and intermediate purity concentrates are available.Citation37 FVIII/FIX concentrates are the mainstay of treatment but in the absence of FVIII concentrate, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), or cryoprecipitate, and in absence of FIX concentrate, FFP were used as alternative therapeutic choices.Citation13,Citation37

In 2010, mean per capita use of FVIII in Iran was 1.56 IU, which was higher than the mean global per capita use of FVIII (1.42 IU). This was the highest rate among Eastern Mediterranean countries and, except for Iran and Saudi Arabia, all other countries of this region have lower than 1 IU per capita use of FVIII.Citation39 The rate of FVIII use in Iranian patients with hemophilia was 1.4 IU per capita in 2005, according to the WFH survey, but in 2010 average per capita factor rose above 2 IU.Citation41,Citation42 Per capita use of FIX in Iran was 0.19 IU in 2010. Although this is lower than the global mean (0.24 IU), it is the highest rate among Eastern Mediterranean countries.Citation39

Prophylaxis versus on-demand treatment in Iran

Management of hemophilia can be achieved by two main therapeutic strategies, prophylaxis and/or on-demand therapy, with prophylaxis the treatment of choice, particularly in children. However, in Iran, as in other developing countries, the main therapeutic approach is on-demand replacement.Citation37 Primary prophylaxis is less common in Iranian patients. A number of studies demonstrate that this therapeutic strategy improves the quality of life for hemophiliacs by reducing bleeding episodes and hospitalization while placing a high cost on the healthcare system.Citation37,Citation43 However, secondary prophylaxis is available for those with involvement of joints and CNSB.

The administered dose in on-demand treatment depends on the situation. Patients with musculoskeletal bleeding receive 15–25 U/kg every 12–24 hours, until the resolution of symptoms. For major and minor surgeries, the factor level is kept between 60 and 100%. The factor level is maintained between 50 and 80% for 5–7 days and 10–14 days for minor and major surgeries.Citation37 A small number of hemophilia patients receive home therapy.Citation37 A study on 287 patients with HA and 92 patients with HB showed that 52.4 and 47.8% of patients with HA and HB do not require medical services for the injection of coagulation factor as on-demand therapy, respectively.Citation13

Inhibitors in Iranian patients with hemophilia

Inhibitor development is a major complication of replacement therapy in hemophilia patients. The rate of inhibitor formation is higher in patients with HA than HB. It is also much higher in severely deficient patients (<1%) than mild (>5–30%) and moderate (1–5%) ones.Citation44 According to the 2010 WHF survey, there are 223 patients (5%) with inhibitor among 4178 patients affected with HA and six patients (1%) with HB.Citation39 Unpublished data of the ICHCC and Iranian Ministry of Health show 323 such patients.Citation45

A few studies to reveal the rate of inhibitor development in hemophiliacs yielded valuable results. These studies are less common among HB patients than HA. The largest such study was conducted on 1280 Iranian HA patients, resulting in the diagnosis of 184 patients (14.4%), the majority of whom had severe form of diseaseCitation16 (Table ). Again, their precise location is not mentioned and overlap is possible.

Table 5 Prevalence of inhibitor among Iranian patients with HA and HB with inhibitor features

A considerable number of studies were performed in different parts of Iran to determine the rate of inhibitor development among hemophilia patients, especially among patients with HA, but the population covered by these studies was nearly one-third of total HA patients and a much smaller number of patients with HB.

Considerable studies to determine the rate of inhibitor development were performed in various parts of the country. The majority found that approximately 20% of HA patients had inhibitor and most had severe HA. It was reported that nearly 3–4% of patients had high-titer antibodies but the majority had low-titer antibodies except for a study in northern Iran, which reported that most HA patients with inhibitor in this area have a high titer.Citation16,Citation46

Since inhibitor development is a multifactorial phenomenon, influenced by genetic defects as well as type and duration of replacement therapy, a number of studies were performed to determine the role of underlying genetic defects and replacement therapy on inhibitor development.Citation3,Citation47,Citation48 A study on 48 Iranian patients with HB showed no correlation between type of replacement therapy and inhibitor formation, although the number of patients with inhibitor was low (statistically insignificant).Citation48 A similar study on HA patients showed that out of 20 patients with inhibitor, 14 had used FVIII concentrate.Citation47 In a multi-country study on 1104 patients with HA, the correlation between FVIII genotype and inhibitor development was assessed. It showed that patients with splice defects are more prone to inhibitor formation (mean 44%; 95% CI 23–65%) followed by inversion of intron 1 (mean 25%; 95% CI 1–49%), nonsense mutations (mean 24%; 95% CI 15–33%), inversion of intron 22 (mean 23%; 95% CI 18–29%), and large deletions (mean 22%; 95% CI 4–40%). Among the countries studied, Iran had the lowest rate of inhibitor development among severe HA patients. The cause was presumed to be lower rate of exposure to exogenous FVIII, since Iranian patients received on-demand replacement therapy.Citation21 In a similar study performed on hemophilia patients of southern Iran, out of eight HA patients with inhibitor, seven had intron 22 inversion and one had a nonsense mutation. Finally, it was concluded that severe molecular defects are responsible for the more severe form of disease and inhibitor formation.Citation22

Management of hemophilia patients with inhibitor

The main challenge in replacement therapy in patients with hemophilia is inhibitor development, which is much higher in patients with HA than HB. Inhibitor development causes reduced therapeutic response and increased rate of bleeding.Citation3,Citation44 Inhibitor development increases the rate of bleeding as well as costs of care.Citation47 The Iranian healthcare system spends 31% of total subsidized funds on hemophilia patients; a high share of this subsidy is allocated to a small number of patients with inhibitor:Citation42,Citation49 over 24 million Euros annually is spent on 124 hemophiliacs with inhibitor.Citation49

Several approaches are used for the management of these patients. Therapeutic choices include recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa), activated prothrombin-complex concentrate (APCC), and immune tolerance induction (ITI) therapy. Use of these bypassing agents increases the treatment costs by up to 12-fold.Citation42,Citation49 APCC and rFVIIa are common therapeutic choices in Iran. In hemophiliacs with inhibitor who experience bleeding, APCC is administered in a dose of 50–100 U/kg every 12 hours until bleeding has ceased. In case of rFVIIa, the administered dose is 70–90 mcg/kg every 2–4 hours. rFVIIa is the most commonly used bypassing agent in the management of these patients.Citation37 ITI is only occasionally used in Iran. For this therapy, 50–100 U/kg of factor concentrate is administrated three times per week.Citation37 Cost effectiveness of the different protocols, ITI versus on-demand therapy with rFVIIa, was assessed in Iran, and it was concluded that low-dose ITI might be less expensive and more effective than rFVIIa in hemophilia patients with high-responding inhibitor.Citation37 Another study was performed to determine cost effectiveness of ITI implantation for management of patients with high responding and high-titer inhibitors against rFVIIa. This study demonstrated the cost effectiveness of ITI implantation and concluded that the optimized breakeven point of ITI and rFVIIa treatment was 17-month post-treatment. The study noted that, although ITI is cost-effective, it imposes higher costs in the first and second years post-treatment but is a cost saving method afterwards.Citation49

Blood-borne diseases among Iranian patients with hemophilia

Multi-transfused patients receiving human blood products, including hemophiliacs, are a high-risk population for the acquisition of blood-borne diseases. In Iran, hemophiliacs are treated with factor concentrate or non-virally inactivated plasma products such as FFP and cryoprecipitate.Citation37 Owing to concerns about infection with blood-borne pathogens and their life-threatening consequences, a wide spectrum of studies were performed to determine the rate of viral infections among these patients.Citation50–Citation58 Prevalence of HIV, HCV, and HBV infection among patients with hemophilia was assessed in a large number of studies.Citation52,Citation53 HCV is the most common blood-borne disease affecting Iranian hemophiliacs; the rate of infection with HCV among them was reported as low as 15.6% in Fars Province in southern Iran to 83.3% in Tehran (Table ).Several studies set out to determine the rate of HIV and HBV infection in addition to HCV infection (Table ). In most of these studies, about one-third of patients with hemophilia were affected with blood-borne diseases and the rate of HBV infection was much lower than HCV, although a higher rate of infection with HBV was observed in some parts of Iran. The HIV infection rate is much lower than HBV and HCV: nobody with HIV infection was detected in some regions.Citation62–Citation65

Table 6 Prevalence of HCV infection among Iranian patients with hemophiliaCitation50–Citation61

Table 7 Prevalence of HBV, HIV, and HCV infections among Iranian patients with hemophiliaCitation12,Citation62–Citation65

Acquired HA

Acquired HA due to anti-FVIII autoantibodies is a rare hemorrhagic condition that can spontaneously occur in non-hemophilic patients or due to underlying conditions such as autoimmune disorders and pregnancy, as well as myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders.Citation66–Citation68 Acquired HA has been rarely assessed in Iran. In a valuable study on 34 Iranian patients with acquired HA, the main causes of this disorder were normal vaginal delivery and rheumatoid arthritis. In a considerable number of patients, the underlying cause of acquired HA was not determined. Most had a high-titer inhibitor against FVIII (>10 BU). Two therapeutic regimes are used for management of their bleeding episodes. rFVIIaa and APCC are used in cases with life-threatening and minor bleeding, respectively, but, in international studies, these two bypassing agents have shown substantial equivalence in controlling bleeding in this setting.Citation67 Moreover, an elimination therapy with prednisolone alone (1–2 mg/kg daily), intravenous immunoglobulin alone, or in combination with prednisolone and cyclophosphamide is used for the elimination of inhibitor. Most patients with these regimes (25 cases) experienced complete remission and five had partial remission.Citation67 In another case report, a woman with low-titer inhibitor against FVIII was described. This inhibitor was developed after delivery. She was managed by FVIII concentrate, rFVIIa as well as immunoglobulin and steroids.Citation68

Conclusion

Iranian experiences on hemophilia show that primary prophylaxis is a suitable therapeutic choice that significantly reduces the rate of bleeding and subsequently increases the quality of life for hemophiliacs. Owing to the potential risk of infections in using plasma-derived components, rFVIII is a suitable alternative treatment. Patients with inhibitor, mostly with severe gene defects, can be managed by APCC, rFVII, or ITI; among them ITI is cost-effective and can decrease the cost of treatment in the long run. These management strategies of Iranian hemophiliacs can be used elsewhere, especially in the developing world.69

Disclaimer statements

Contributors Authors own works.

Funding None.

Conflict of interest No conflict-of-interest.

Ethics approval None.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Daisy Morant for his work to improve English language of this manuscript.

References

- Kulkarni R, Soucie JM, editors. Pediatric hemophilia: a review. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011; 37(7):737–44.

- Carcao MD, editor. The diagnosis and management of congenital hemophilia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012; 38(7):727–34.

- Wight J, Paisley S. The epidemiology of inhibitors in haemophilia A: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2003; 9(4):418–35.

- Yacoub A. Diagnosis, successful hemostasis and peri-operative management of an elderly man with undiagnosed hemophilia B undergoing a complex neurosurgery. Blood. 2013;122(21):4789–90.

- Valleix S, Vinciguerra C, Lavergne J-M, Leuer M, Delpech M, Negrier C. Skewed X-chromosome inactivation in monochorionicdiamniotic twin sisters results in severe and mild hemophilia A. Blood. 2002;100(8):3034–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0277

- Forsyth A, Witkop M, Guelcher C, Lambing A, Cooper DL. Is bleeding in hemophilia really spontaneous or activity related: analysis of US patient/caregiver data from the Hemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO) study. Blood. 2013;122(21):2364–3264.

- Witmer C, Young G. Factor VIII inhibitors in hemophilia A: rationale and latest evidence. Ther Adv Hematol. 2013; 4(1):59–72.

- Kenet G, Bidlingmaier C, Bogdanova N, Ettingshausen CE, Goldenberg N, Gutsche S, et al. Influence of factor 5 rs6025 and factor 2 rs1799963 mutation on inhibitor development in patients with hemophilia A-an Israeli-German multicenter database study. Thromb Res. 2014;133(4):544–9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.01.005

- Astermark J. Genetic and environmental risk factors for factor VIII inhibitor development. In: C. A. Lee, E. E. Berntorp and W. K. Hoots., editor. Textbook of hemophilia. Vol. 3; 2014. p. 48–52.

- Report on the WFH Global Survey. Compiled and produced by the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2014.

- Mehdizadeh M, Kardoost M, Zamani G, Baghaeepour M, Sadeghian K, Pourhoseingholi M. Occurrence of haemophilia in Iran. Haemophilia. 2009;15(1):348–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01874.x

- Ziaei J, Dolatkhah R, Dastgiri S, Mohammadpourasl A, Asvadi I, Mahmoudpour A, et al. Inherited coagulation disorders in the northwestern region of Iran. Haemophilia. 2005;11(4):424–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2005.01118.x

- Mansouritorghabeh H, Manavifar L, Banihashem A, Modaresi A, Shirdel A, Shahroudian M, et al. An investigation of the spectrum of common and rare inherited coagulation disorders in North-Eastern Iran. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(2):233.

- Karimi M, Haghpanah S, Amirhakimi A, Afrasiabi A, Dehbozorgian J, Nasirabady S. Spectrum of inherited bleeding disorders in southern Iran, before and after the establishment of comprehensive coagulation laboratory. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2009;20(8):642–5. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32832f4371

- Rezaei N, Aliasgharpoor M. Prevalence of factor VIII inhibitor in patients with hemophilia A in Sanandaj. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2011;15(2):127–31.

- Sharifian R, Hosseini M, Safai R, Gh T, Ehsani A, Lak M, et al. Prevalence of inhibitors in a population of 1280 hemophilia a patients in Iran. Acta Medica Iranica. 2003;41(1):66–8.

- Haghpanah S, Bazrafshan A, Silavizadeh S, Dehghani J, Afrasiabi A, Karimi M. Evaluation of thrombin generation assay in patients with hemophilia. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;6(4):1–5.

- Mansouritorghabeh H. Clinical and laboratory approaches to hemophilia A. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;40(3):194.

- Modaresi A, Torghabeh HM, Pourfathollah A, Shooshtari MM, Yazdi ZR. Pattern of factor VIII inhibitors in patients with hemophilia A in the north east of Iran. Hematology. 2006;11(3):215–7. doi: 10.1080/10245330600667526

- Ravanbod S, Rassoulzadegan M, Rastegar-Lari G, Jazebi M, Enayat S, Ala F. Identification of 123 previously unreported mutations in the F8 gene of Iranian patients with haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2012;18(3):e340–e6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02708.x

- Boekhorst J, Lari G, D'oiron R, Costa J, Novakova I, Ala F, et al. Factor VIII genotype and inhibitor development in patients with haemophilia A: highest risk in patients with splice site mutations. Haemophilia. 2008;14(4):729–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01694.x

- Haghpanah S, Sahraiian M, Afrasiabi A, Enayati S, Peyvandi F, Karimi M. The correlation between gene mutations and inhibitor development in patients with haemophilia A in southern Iran. Haemophilia. 2011;17(5):820–1.

- Enayat M, Arjang Z, Lavergne J, Ala F. Identification of intron 1 and 22 inversion mutations in the factor VIII gene of 124 Iranian families with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2004;10(4):410–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00920.x

- Rafati M, Ravanbod S, Hoseini A, Rassoulzadegan M, Jazebi M, Enayat M, et al. Identification of ten large deletions and one duplication in the F8 gene of eleven unrelated Iranian severe haemophilia A families using the multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification technique. Haemophilia. 2011;17(4):705–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02476.x

- Roozafzay N, Kokabee L, Zeinali S, Karimipoor M. Analysis of Intron 1 Inversion at F8 gene in severe hemophilia A patients by inverse shifting-PCR referred from Isfahan Seyedolshohada Hospital. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2013;13(1):93–101.

- Onsori H, Feizi MAH, Feizi AAH. A novel missense mutation, E1623G, in the human factor VIII gene associated with moderate haemophilia A. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1):e672–7. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.6727

- Onsori H, Hosseinpour MA, Montaser-Kouhsari S, Asgharzadeh M, Hosseinpour AA. Identification of a novel missense mutation in exon 4 of the human factor VIII gene associated with sever hemophilia A patient. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10(23):4299–302. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.4299.4302

- Zadeh-Vakili A, Eshghi P, Lari GR. Efficiency of BclI restriction fragment length polymorphism for detection of hemophilia A carriers in Sistan and Baluchestan Province, Southeast of Iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;33(1):33–6.

- Moharrami T, Derakhshan SM, Pourfeizi AAH, Khaniani MS. Detection of hemophilia A carriers in Azeri Turkish population of Iran usefulness of HindIII and BclI markers. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;6(4):1–5.

- Karimipour M, Zeinali S, Graham Tuddenham E, Nafissi N, Lak M, Green P. Molecular characterization of the factor IX gene in 28 Iranian hemophilia B patients. Iran J Blood Cancer. 2009;1(2):43–7.

- Karimipoor M, Zeinali S, Nafissi N, Tuddenham EG, Lak M, Safaee R. Identification of factor IX mutations in Iranian haemophilia B patients by SSCP and sequencing. Thromb Res. 2007;120(1):135–9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.07.011

- Kamali DE, Karimipour M, Samiei S, Kokabee L, Zinali S, Nafissi N, et al. Mutation analysis of coagulation factor IX gene in Esfahanian hemophilia B patients by SSCP and sequencing. Sci J Blood Transfus Organ. 2007;4(3):299–308.

- Karimi NK, Koukabi L, Badiei Z, Shahabi M, Banihashem S, Zeynali S, et al. Molecular analysis of coagulation factor IX gene in hemophilia B patients of KhorasanRazavi Province. Sci J Blood Transfus Organ. 2010;7(1):17–56.

- Dorgalaleh A, Naderi M, Hosseini MS, Alizadeh S, Hosseini S, Tabibian S, et al. editors. Factor XIII deficiency in Iran: a comprehensive review of the literature. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2015;41(3):323–9.

- Ghaffarpoor M, Sharifian R, Mehrabi F, Salehi M. Neurologic complications in hemophilia: a study in 214 cases. Acta Medica Iranica. 2001;39(4):182–4.

- Roushan N, Meysamie A, Managhchi M, Esmaili J, Dormohammadi T. Bone mineral density in hemophilia patients. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;30(4):351–5. doi: 10.1007/s12288-013-0318-4

- Srivastava A, You SK, Ayob Y, Chuansumrit A, de Bosch N, Perez Bianco R, et al. editors. Hemophilia treatment in developing countries: products and protocols. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2005: New York: Stratton Intercontinental Medical Book Corporation, c1974-.

- Kiadaliri AA, Pourmohammadi K, Bastani P, Karimi M. The impact of factor VIII inhibitors on factor consumption in haemophilia A: a case-control study in South of Iran. Middle East J Sc Res. 2011;8(3):694–8.

- Report on the WFH Global Survey. Compiled and produced by the World Federation of Hemophilia; 2010.

- Salimi C. The history of care in Iran, Hemophilia Today, Spring 2002, p. 13.

- Report on the WFH Global Survey. Compiled and produced by the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2005.

- Rasekh HR, Imani A, Karimi M, Golestani M. Cost-utility analysis of immune tolerance induction therapy versus on-demand treatment with recombinant factor VII for hemophilia A with high titer inhibitors in Iran. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;3(2):207–12. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S25909

- Daliri AAK, Haghparast H, Mamikhani J. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against on-demand treatment in boys with severe hemophilia A in Iran. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(04):584–7. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309990420

- Oldenburg J, Brackmann H-H, Schwaab R. Risk factors for inhibitor development in hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2000;85(10 Suppl.):7–13. discussion 4.

- Faranoush M, Abolghasemi H, Mahboudi F, Toogeh G, Karimi M, Eshghi P, et al. A Comparison of efficacy between recombinant activated factor VII (Aryoseven) and Novoseven in patients with Hereditary FVIII deficiency with inhibitor. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;6(3):14–19.

- Nesheli HM, Hadizadeh A, Bijani A. Evaluation of inhibitor antibody in hemophiliaA population. Caspian J Intern Med. 2013;4(3):727.

- Torghabeh HM, Pourfathollah A, Shoosshtari MM, Rezaieyazdi Z. Coagulation therapy in hemophilia A and its relation to factor VIII inhibitor in Northeast of Iran. IJMS. 2004;29(4).

- Mansouri Torghabeh H, Pourfathollah A, Mahmoudian Shoushtari M. Evaluation of the relationship between factor IX inhibitor in hemophilia B patients and different types of therapy in the north-eastern part of Iran. Iran J Blood Cancer. 2009;1(2):83–6.

- Cheraghali AM, Eshghi P. Cost assessment of implementation of immune tolerance induction in Iran. Value Health Reg Issues. 2012;1(1):54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2012.03.014

- Merat S, Rezvan H, Nouraie M, Jamali J, Assari S, Abolghasemi H, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis B core antibody in Iran: a population-based study. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12(3):225–31.

- Owrang Eilami M, Sharifi A, Marzieh Tabatabaee M. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection among high risk groups in Kohgiloyeh and Boyerahmad province, Southwest Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(5):271–4.

- Javadzadeh-Shahshahani H, Attar M, Yavari M, Savabieh S. Study of the prevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in hemophilia and Thalassemia population of Yazd. Sci J Iran Blood Transfus Organiz Res Center. 2005;2(7):315–22.

- Abdollahi A, Shahsiah R, Nassiri Toosi M, Lak M, Karimi K, Managhchi M, et al. Seroprevalence of Human immunodificiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C infection in hemophilic patients in Iran. Iran J Pathol. 2008;3(3):119–24.

- Alavian S-M. Control of hepatitis C in Iran: vision and missions. Hepat Mon. 2007;7(2):57–8.

- Javadzadeh SH, Attar M, Yavari MT, Savabieh S. Study of the prevalence of Hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in hemophilia and Thalassemia population of Yazd. Sci J Blood Transfus Organ. 2006;2(7):315–22.

- Moghaddam MA, Zali MR, Andabili SHA, Derakhshan F, Miri SM, Alavian SM. High rate of virological response to Peginterferon α-2a–Ribavirin among non-cirrhotic Iranian hemophilia patients with chronic Hepatitis C. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14(8):466–73.

- Rafiei A, Darzyani AM, Taheri S, Haghshenas M, Hosseinian A, Makhlough A. Genetic diversity of HCV among various high risk populations (IDAs, thalassemia, hemophilia, HD patients) in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6(7):556–60. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60096-6

- Rahmani M, Toosi M, Ghannadi K, Lari G, Jazebi M, Rasoulzadegan M, et al. Clinical outcome of interferon and ribavirin combination treatment in hepatitis C virus infected patients with congenital bleeding disorders in Iran. Haemophilia. 2009;15(5):1097–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02042.x

- Yazdani MR, Kassaian N, Ataei B, Nokhodian Z, Adibi P. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with hemophilia in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S89–89.

- Alavian S, Ardeshir A, Hajarizadeh B. Seroprevalence of anti-HCV among Iranian hemophilia patients, Transfusion Today-Groningen, 2001;4(9):4–5.

- Mousavian S, Mansouri F, Saraei A, Sadeghei A, Merat S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C in hemophilia patients refering to Iran Hemophilia Society Center in Tehran. Govaresh. 2011;16(3):169–74.

- Mansour-Ghanaei F, Fallah M-S, Shafaghi A, Yousefi-Mashhoor M, Ramezani N, Farzaneh F, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C seromarkers and abnormal liver function tests among hemophiliacs in Guilan (Northern Province of Iran). Med Sci Monit. 2002;8(12):CR797–CR800.

- Sharifi-Mood B, Sanei-Moghaddam S, Salehi M, Eshghi P, Khosravi S, Khalili M. Viral infection among patients with hemophilia in the Southeast of Iran. J Med Sci. 2006;6(2):225–8. doi: 10.3923/jms.2006.225.228

- Zahedi MJ, Darvishmoghadam S. Frequency of Hepatitis B and C infection among hemophiliac patients in Kerman. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2004;11(3):131–5.

- Assarehzadegan MA, Boroujerdnia MG, Zandian K. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections and HCV genotypes among haemophilia patients in ahvaz, southwest iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14(8):470–4.

- Franchini M, Gandini G, Di Paolantonio T, Mariani G. Acquired hemophilia A: a concise review. Am J Hematol. 2005;80(1):55–63. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20390

- Lak M, Sharifian RA, Karimi K, Mansouritorghabeh H. Acquired hemophilia A: clinical features, surgery and treatment of 34 cases, and experience of using recombinant factor VIIa. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;3(4):48–53.

- Borna S, Hantoushzadeh S. Acquired hemophilia as a cause of primary postpartum hemorrhage. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10(1):107–10.