Abstract

Objectives: Optimal chemotherapy regimen for peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) has not been fully defined. This study aimed to evaluate the optimal chemotherapy regimen in the first-line treatment for PTCL patients.

Methods: Between 2003 and 2014, 93 consecutive patients with PTCL were enrolled in this study. Of 93 patients, 42 patients received CHOPE, 40 patients with CHOP, and 11 patients with GDP regimen.

Results: Response could be evaluated in 88 of 93 patients at the end of primary treatment. The CR rate for patients received CHOP (n = 38), CHOPE (n = 39), and GDP (n = 11) were 28.9, 51.3, and 45.5%, respectively, (P = 0.132) with an ORR of 65.8, 76.9, and 90.9%, respectively, (P = 0.210). The median follow-up time was 17.1 (1.4–108.3) months. Median progression-free survival (PFS) in CHOP (n = 40), CHOPE (n = 42), and GDP (n = 11) groups were 6.0, 15.3, and 9.7 months (P = 0.094) with 1-year PFS of 35.0, 54.8, and 45.5%, respectively, (P = 0.078). One-year OS for patients received CHOP (n = 40), CHOPE (n = 42), and GDP (n = 11) were 65.0, 83.3, and 100%, respectively, (P = 0.013) (CHOP vs CHOPE, P = 0.030; CHOP vs GDP, P = 0.024; CHOPE vs GDP, P = 0.174).

Conclusion: CHOPE has a trend to improve CR rate, 1-year PFS and OS compared with CHOP alone. GDP shows promising efficacy which worth further exploration in large cohort studies. Clinical experience presented in this study may serve as reference for future large cohort studies.

Introduction

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) are a heterogeneous and uncommon group of lymphoid malignancies, accounting for about 10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL).Citation1 PTCL are aggressive in nature with poorer prognosis compared with aggressive B-cell NHL.Citation2–Citation4

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) regimen is mostly common used for PTCL patients, but with the exception of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), treatment results in PTCL are generally less favorable.Citation5,Citation6 Evidence of other regimens being superior to CHOP is unfortunately not sufficient.Citation7–Citation9

Intensive chemotherapy regimens have been assessed in the first-line treatment of patients with PTCL. The addition of etoposide to CHOP (CHOPE) may be favorable, however, the benefit was limited to relatively young patients (age <60 years), and only a trend toward improved event-free survival (EFS) was found with no OS difference in PTCL patients (except ALK positive ALCL).Citation9 Other intensive chemotherapy regimens, such as hyper CVAD and EPOCH, have also not been proved successful for those with non-ALCL subtypes.Citation5,Citation8,Citation10

A large cohort multi-center retrospective study showed that the use of anthracycline-containing regimens were not associated with an improved outcome in PTCL-not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS) or angioimmunoblastic patientsCitation5. Clearly, better therapeutic regimens are needed to improve the survival outcome of these patients. Recently, a series of studies indicated that gemcitabin based regimens have encouraging activity in PTCL patients.Citation11–Citation13

As PTCL are rare, much knowledge derives from retrospective analyses and only limited data exist from randomized trials comparing the efficacy of first-line chemotherapy regimens exclusively in PTCL patients. Therefore, optimal chemotherapy regimen has not been fully defined. In this study, we aimed to compare CHOP, CHOPE, and GDP (gemcitabin, cispaltin, and dexamethasone) in the first-line treatment of PTCL patients and clinical experience presented in this study may serve as reference for future prospective clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between 2003 and 2014, 93 PTCL patients (including 71 PTCL-NOS patients, 13 ALK negative ALCL patients, and 9 angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma patients) who consecutively treated in cancer hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) & Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) were included in this study. The eligibility criteria for patients in this study included: (1) histological diagnosis of PTCL based on the WHO classification, (2) at least one measurable lesion, (3) no previous therapy, (4) received chemotherapy first (chemotherapy regimens include CHOP, CHOPE, or GDP), (5) did not receive autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (AHSCT). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee and the Human Research Committee of the cancer hospital, CAMS & PUMC. Patient records was anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis. Initial staging was assessed according to the Ann Arbor system. All pathological specimens were reviewed in pathology department to confirm the diagnosis in our hospital.

Chemotherapy

Of 93 patients, 42 patients received CHOPE, 40 patients with CHOP, and 11 patients with GDP. CHOP regimen consisted of epirubicin (75 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), vincristine (1.4 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1, maximum 2.0 mg/body), prednisolone (100 mg/d PO days 1–5) which was administered every 21 days. CHOPE regimen consisted of epirubicin (75 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), vincristine (1.4 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1, maximum 2.0 mg/body), prednisolone (100 mg/d PO days 1–5) and etoposide (total dose 200 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1–3) which was administered every 21 days. GDP regimen consisted of gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1 and 8), cisplatin (25 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1–3), and dexamethasone (20 mg/d on days 1–4 and days 11–14), which was administered every 21 days.

Efficacy assessments

The treatment response was assessed after every two cycles of chemotherapy according to International Workshop Criteria. Initial response includes complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). Overall response rate (ORR) was defined as CR rate plus PR rate.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initiation of therapy to the date of either last follow-up or death. Patients who were alive at last follow-up visit were referred to as censored data. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of initiation of therapy to the date of disease progression, deaths or last follow-up. Patients who were not progressed or deaths at last follow-up were recognized as censored data.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of clinical characteristics and response rate between different groups were performed using χ2 test and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Survival analysis was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and all P values correspond to two-sided significance tests. Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 19.0 software package.

Results

Patient characteristics

Clinical characteristics of 93 patients are outlined in Table . Thirty-one of 93 patients (33.3%) were categorized as stage I/II with 62 patients (66.7%) of stage III/IV. Thirty-eight of 93 patients (40.9%) had International Prognostic Index (IPI) scores between 0 and 1, and 55 patients (59.1%) had IPI scores ≥2. Seventy-two of 93 patients (77.4%) had Prognostic Index for T-cell lymphoma (PIT) scores between 0 and 1, and 21 patients (22.6%) had PIT scores ≥2. Patients in different chemotherapy groups were balanced with respect to baseline characteristics.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of all PTCL patients

Response

The response rates at the end of primary treatment were described in Table . Response could be evaluated in 88 of 93 patients at the end of primary treatment. The CR rate for patients received CHOP (n = 38), CHOPE (n = 39), and GDP (n = 11) were 28.9, 51.3, and 45.5%, respectively, (P = 0.132) with an ORR of 65.8, 76.9, and 90.9%, respectively, (P = 0.210).

Table 2 Response evaluated at the end of primary treatmenta

Survival

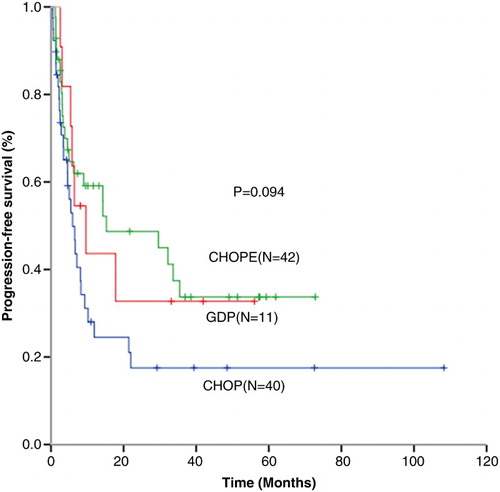

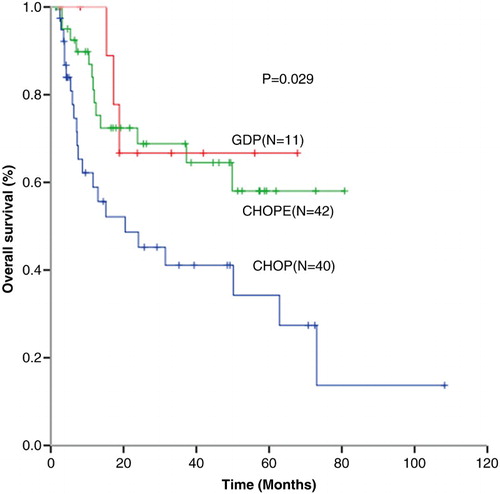

The median follow-up time was 17.1 (1.4–108.3) months. Median progression-free survival (PFS) in CHOP (n = 40), CHOPE (n = 42), and GDP (n = 11) groups were 6.0, 15.3, and 9.7 months (P = 0.094) with 1-year PFS of 35.0, 54.8, and 45.5%, respectively, (P = 0.078) (Fig. ). One-year OS for patients received CHOP (n = 40), CHOPE (n = 42), and GDP (n = 11) were 65.0, 83.3, and 100%, respectively, (P = 0.013) (CHOP vs CHOPE, P = 0.030; CHOP vs GDP, P = 0.024; CHOPE vs GDP, P = 0.174) (Fig. ).

Figure 1 Progression-free survival (PFS) for patients received CHOP (n = 40), CHOPE (n = 42), and GDP (n = 11) regimen.

Figure 2 Overall survival (OS) for patients received CHOP (n = 40), CHOPE (n = 42), and GDP (n = 11) regimen.

Subgroup analysis showed that for patients with PIT 0–1, 1-year PFS in CHOP (n = 29), CHOPE (n = 34), and GDP (n = 9) groups were 37.9, 52.9, and 44.4%, respectively, (P = 0.218) with 1-year OS of 69.0, 82.4, and 100% (P = 0.072). While for PIT ≥2 patients, 1-year PFS and OS in patients received CHOP (n = 11), CHOPE (n = 8) and GDP (n = 2) were 27.3, 62.5, 50.0% (P = 0.533) and 54.5, 87.5, 100% (P = 0.232), respectively.

Safety

All patients were assessed for toxicity. Common adverse events that occurred at an incidence of 10% or greater are listed in Table . With the exception of more incidence of thrombocytopenia for patients received GDP regimen, there was no significant difference of other adverse events in three groups.

Table 3 Most common adverse eventsa

Discussion

As PTCL is a rare subtype of NHL with poor outcome. Standard first-line chemotherapy regimen for PTCL has not been fully established. Our study compared the efficacy of GDP, CHOP, and CHOPE in the first-line treatment of PTCL, indicating that CHOPE has a trend to improve CR rate and 1-year PFS and OS compared with CHOP alone. GDP shows promising efficacy which worth further exploration in large cohort studies.

PTCL are less responsive to standard CHOP regimen, thus carrying a poorer outcome than aggressive B cell lymphoma.Citation14–Citation16 Dose intensive therapies, when compared to CHOP, have been largely disappointing.Citation8 Owing to disease rarity, there have been few randomized studies evaluating intensive regimens compared to CHOP exclusively in PTCL patients. In a phase 3 randomized trial, six cycles of alternating VIP/ABVD (etoposide, ifosfamide, cisplatin/doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) was not superior to eight cycles of 3-weekly CHOP for newly diagnostic PTCL patients with a 2-year EFS of only 41%.Citation16 Even if widely used, there is no definite evidence that the addition of etoposide to CHOP improves outcome for PTCL patients.Citation17 The best evidence for the benefit of adding etoposide comes from a retrospective analysis where a better EFS for younger PTCL patients without ALK positive ALCL treated with CHOEP was observed, and there was no OS difference.Citation9

In the present study, the median PFS for PTCL patients received CHOP regimen was 6.0 months with 1-year PFS and OS of 35.0% and 65.0%. Compared with CHOP, CHOPE could significantly improve 1-year OS to 83.3%. It is worthwhile to note that this survival benefit can be observed both in low-risk (PIT 0–1) group and higher risk (PIT ≥2) group. The data present in our study essentially in agreement with previous studies, indicating that the addition of etoposide to CHOP is associated with survival benefit compared with CHOP alone. Thus for patients who can tolerate intensive chemotherapy, CHOPE is an optimal choice.

Apart from ALK positive ALCL, anthracyclines based regimens cannot achieve satisfactory efficacy against PTCL. The International PTCL Study found no survival differences comparing the outcome of patients with PTCL treated with or without antracyclines, although the number of patients treated with non-anthracycline based regimens is small.Citation5 Thus non-anthracycline based regimens such as gemcitabin based chemotherapy were explored in several studies for PTCL patients.Citation11–Citation13 The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) conducted a phase 2 study assessing the efficacy of PEGS (cisplatin, etoposide, gemcitabine, and methylprednisolone) among patients with newly diagnosed PTCL, excluding patients with ALK positive ALCL, showed a 2-year PFS of 14% and a 2-year OS of 36%.Citation7 Arkenau et al.Citation12 reported that 1-year survival was 68.2% using GEM-P (gemcitabine, cisplatin, and methylprednisolone) regimen for the treatment of PTCL. A phase 2 trial showed that the 5-year EFS was 49% and median survival was 30.5 months using GIFOX (gemcitabine, ifosfamide, and oxaliplatin) as first-line treatment in high-risk peripheral T-Cell/NK lymphomas, but grade 4 thrombocytopenia and anemia were observed in 38 and 24% of patients, respectively. A retrospective study showed that the 1- and 2-year PFS rates were 58.7 and 45.9%, while 1-and 2-year OS rates were 80.6 and 63.7%, respectively, for 26 PTCL patients received gemcitabine-based combination regimen.Citation13 In the present study, the CR rate and ORR were 45.5 and 90.9% for patients received GDP. The median PFS was 9.7 months, and 1-year PFS and OS were 45.5 and 100%. Although the sample size in GDP group is relatively small, the results were comparable to previous studies. Notably, a proportion of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma patients, the disease of whom were more sensitive to gemcitabin based regimens, were enrolled in previous studies. But all patients evaluated in our study were PTCL, indicating that GDP, as first-line treatment for PTCL, has promising efficacy.

This is a retrospective study, so the bias between different treatment groups exists. To reduce the imbalance, the interclass equilibration were compared which showed that the different treatment groups were well-balanced with respect to baseline characteristics. Now the studies assessing first-line chemotherapy for PTCL patients are limited and a long period would be needed to wait for the results of prospective studies. The sample size in this study is not large enough, but with regard to the results in our study, new chemotherapy regimens have been explored which worth further evaluation in prospective, randomized, phase 3 clinical trials. Significant challenges remain in the management of PTCL and until major advances are made, the CHOP or CHOPE regimen will continue to be the standard backbone of therapy.

In conclusion, CHOPE has a trend to improve CR rate and 1-year PFS and OS compared with CHOP alone for PTCL-NOS patients. GDP shows promising efficacy which needs further exploration in prospective, randomized, phase 3 clinical trials. Clinical experience presented in this study may serve as reference for future large cohort studies.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors BJ, XH and YS designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. BJ and SH collected data. HL contributed to medical records management in this study. BJ, XH, SH, JY, SZ, PL, YQ, LG, SY, CZ, PX, LW, MD, LZ, YS and YS participated in patients treatment in this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding The study was supported by grants from the Chinese National Major Project for New Drug Innovation (2008ZX09312, 2012ZX09303012-001) and National Key Technology Support Program (2014BAI09B12).

Conflict of interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the Ethics Committee and the Human Research Committee of the cancer hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) & Peking Union Medical College (PUMC).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients, medical staff and physicians who participated in this study.

References

- The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood 1997;89(11):3909–18.

- Gallamini A, Stelitano C, Calvi R, Bellei M, Mattei D, Vitolo U, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified (PTCL-U): a new prognostic model from a retrospective multicentric clinical study. Blood 2004;103(7):2474–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3080

- Gisselbrecht C, Gaulard P, Lepage E, Coiffier B, Briere J, Haioun C, et al. Prognostic significance of T-cell phenotype in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA). Blood 1998;92(1):76–82.

- Savage KJ, Chhanabhai M, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM. Characterization of peripheral T-cell lymphomas in a single North American institution by the WHO classification. Ann Oncol 2004;15(10):1467–75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh392

- Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2008;26(25):4124–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4558

- Coiffier B, Brousse N, Peuchmaur M, Berger F, Gisselbrecht C, Bryon PA, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas have a worse prognosis than B-cell lymphomas: a prospective study of 361 immunophenotyped patients treated with the LNH-84 regimen. The GELA (Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Agressives). Ann Oncology 1990;1(1):45–50.

- Mahadevan D, Unger JM, Spier CM, Persky DO, Young F, LeBlanc M, et al. Phase 2 trial of combined cisplatin, etoposide, gemcitabine, and methylprednisolone (PEGS) in peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Southwest Oncology Group Study S0350. Cancer 2013;119(2):371–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27733

- Escalon MP, Liu NS, Yang Y, Hess M, Walker PL, Smith TL, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment of patients with T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer 2005;103(10):2091–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20999

- Schmitz N, Trumper L, Ziepert M, Nickelsen M, Ho AD, Metzner B, et al. Treatment and prognosis of mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T-cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2010;116(18):3418–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270785

- Nickelsen M, Ziepert M, Zeynalova S, Glass B, Metzner B, Leithaeuser M, et al. High-dose CHOP plus etoposide (MegaCHOEP) in T-cell lymphoma: a comparative analysis of patients treated within trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol 2009;20(12):1977–84. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp211

- Zinzani PL, Venturini F, Stefoni V, Fina M, Pellegrini C, Derenzini E, et al. Gemcitabine as single agent in pretreated T-cell lymphoma patients: evaluation of the long-term outcome. Ann Oncol 2010;21(4):860–3. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp508

- Arkenau HT, Chong G, Cunningham D, Watkins D, Sirohi B, Chau I, et al. Gemcitabine, cisplatin and methylprednisolone for the treatment of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma: the Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Haematologica 2007;92(2):271–2. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10737

- Dong M, He XH, Liu P, Qin Y, Yang JL, Zhou SY, et al. Gemcitabine-based combination regimen in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Med Oncol (Northwood, London, England) 2013;30(1):351. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0351-4

- Greer JP. Therapy of peripheral T/NK neoplasms. Hematology 2006;2006(1):331–7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.331

- Horwitz SM. Management of peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol 2007;19(5):438–43. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282ce6f8f

- Simon A, Peoch M, Casassus P, Deconinck E, Colombat P, Desablens B, et al. Upfront VIP-reinforced-ABVD (VIP-rABVD) is not superior to CHOP/21 in newly diagnosed peripheral T cell lymphoma. Results of the randomized phase III trial GOELAMS-LTP95. Br J Haematol 2010;151(2):159–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08329.x

- Moskowitz AJ, Lunning MA, Horwitz SM. How I treat the peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2014;123(17):2636–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-516245