ABSTRACT

Objective: A major cause of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is malignant neoplasms of the blood system, among which NK/T cell lymphoma is one of the most common risk factors. Patients with NK/T cell lymphoma hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (NK/T-LAHS) have a worse prognosis and higher mortality. We aimed to explore the factors that affect the prognosis of NK/T-LAHS.

Methods: Clinical data of 42 patients with NK/T-LAHS diagnosed by Beijing Friendship Hospital from June 2008 to June 2016 were analyzed retrospectively. The survival time was counted until 1 August 2016.

Results: For the 42 NK/T-LAHS patients, 1-month survival rate was 48.9%, 2-month survival rate was 36.7%, 3-month survival rate was 28.8%, 6-month survival rate was 23.0%, and 12-month survival rate was 15.4%. NK/T-LAHS patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Allo-HSCT) (p = 0.000), exhibited peripheral blood Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positivity (p = 0.004), and achieved overall response (OR) remission after initial induction therapy (p = 0.007) had statistical significance.

Conclusion: NK/T-LAHS is a disease of poor prognosis and high mortality. NK/T-LAHS patients who achieved OR remission after the initial induction therapy had a better prognosis than non-remission patients and Allo-HSCT was an effective way to prolong the survival of NK/T-LAHS patients. However, EBV positivity in peripheral blood was a poor prognostic factor in NK/T-LAHS patients.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening disorder characterized by high inflammatory cytokines production induced by excessive immune activation. HLH can be divided into primary disease, which is characterized by cell dysfunction due to gene mutation; and secondary HLH which is secondary to infection, autoimmune diseases, malignant tumors, and other causes [Citation1–3]. Letendre and co-workers [Citation4] examined 62 cases of HLH patients, and found that tumor-related HLH was the most common cause, accounting for 52% of patients with HLH. Furthermore, Rivière et al. [Citation5] studied 162 cases of HLH patients, and demonstrated that hematological malignancies, especially non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, were one of the main cause of hemophagocytic syndrome, accounting for 56% incidence. These data suggest that malignant tumors; especially non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is one of the most common risk factors of HLH. Moreover, in LAHS patients, NK/T cell lymphoma hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (NK/T-LAHS) subtype is one of the most common pathology, accounting for up to 35% of the LAHS patient population [Citation6].

NK/T-cell lymphoma is an extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, usually with a poor prognosis, whose survival rate depends on the different parts of the primary site tumor [Citation7]. NK/T cell lymphoma is often co-morbid with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. Suzuki et al. [Citation8] found that in NK/T cell lymphoma patients, the detection rate of EBV-DNA was greater than 90%. Quantitative detection of serum EBV-DNA levels in patients found that high EBV-DNA expression was related with poor clinical stage and prognosis compared with patients with low EBV-DNA expression, suggesting a positive relationship between EBV-positivity and NK/T cell lymphoma prognosis. Additional studies have shown that EBV-positive NK/T cell lymphoma patients have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 50% [Citation9].

NK/T-LAHS is a disease with poor prognosis and high mortality that is often associated with the presence of EBV infection [Citation6]. Letendre et al. [Citation4] investigated the prognosis of patients with HLH, and found that the overall median survival time was 2.1 months, tumor-related HLH patients had a median survival time of only 1.4 months, while those with non-tumor-related HLH had a median survival time of 22.8 months; the difference of which was significant (p = 0.01). Furthermore, Rivière et al. [Citation5] found that for hematologic malignancies, especially in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma-related HLH, early mortality (within 1 month after diagnosis) was as high as 20%, and the prognosis of patients with hematologic malignancy-associated hemophagocytic syndrome was even worse. Imashuku and co-workers [Citation10] conducted a study of 567 HLH patients in 292 medical institutions in Japan from 2001 to 2005, and showed that the 5-year survival rate of patients with EBV or other infection-related HLH was more than 80%. The 5-year survival rate of familial HLH and B-LAHS was second, while the prognosis of patients with NK/T-LAHS was the worst, with a 5-year survival rate of <15%. This suggests that patients with LAHS have a worse prognosis [Citation4,Citation5,Citation10,Citation11], among which patients with NK/T-cell lymphoma have a worse prognosis than patients with B-cell lymphoma in all LAHS patients, and a higher mortality as well [Citation10,Citation12,Citation13]. Herein, we aimed to investigate factors that influence the prognosis of patients with NK/T-LAHS, thus conducted a multivariate analytical study.

Methods

Study subjects

Clinical data of 42 patients with NK/T-LAHS diagnosed by Beijing Friendship Hospital from June 2008 to June 2016 were analyzed retrospectively. All patients met the following inclusion criteria: age ≥14 years of adolescent and adult patients; met HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria of secondary HLH diagnostic criteria [Citation14]; existence of tumor-related evidence [Citation15]: lymphoid tumor system was classified as NK/T-cell lymphoma by tissue and organ biopsy. The pathological criteria of the diagnosis of the NK/T lymphoma were according to the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. All pathological biopsies were reviewed double blinded by two pathologists.

Clinical observation

(1) Patients’ general health condition, including age, and sex; (2) body temperature; (3) laboratory examination: blood, liver function, serum ferritin levels, fibrinogen levels, triglyceride levels, hemophagocytosis, spleen size, NK cell activity, soluble CD25 level, survival time, prognosis, peripheral blood and serum EBV, and pathological diagnosis of EBER. Liver function abnormalities were defined as ‘one or more of the liver enzyme index was higher than the upper limit of 2 times the normal’.

Positive EBV in peripheral blood

Defined as EBV-DNA copy number of peripheral blood ≥500 copies/ml. Positive EBV in serum: defined as EBV-DNA copy number of serum ≥500 copies/ml. Pass the EBV international standard, namely: 09/260 (NIBSC number) for detection [Citation16].

Evaluation criteria for the therapeutic effect

According to the revised efficacy standards developed by United States HLH collaborative group [Citation17], include complete response (CR), partial response (PR) and no response (NR).

Treatment

(1), Initial induction therapy included: HLH-94/04 regimen [Citation18,Citation14], chemotherapy targeting tumor, and simple glucocorticoid therapy; (2), salvage therapy was the DEP regimen (doxorubicin-etoposide-methylprednisolone) [Citation19]; (3), autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Statistical methods

SPSS version 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. All the data that conformed to the normal distribution was represented by x ± SD, while non-normal-distributed data were presented using the median and extreme values. Survival analysis (Kaplan–Meier analysis) was used to calculate the survival rate of NK/T-LAHS patients in January, February, March, June and December. Multivariate analysis (logistic regression) were used to calculate ‘sex’, ‘age’, ‘initial treatment outcome is OR or not’, ‘whether underwent Allo-HSCT’, and ‘whether peripheral blood EBV was positive’, ‘whether HLH was present “during tumor chemotherapy” or “after chemotherapy” and other six factors which had an effect on NK/T-LAHS patients’ prognosis. Statistical difference was defined as p < 0.05, significant statistical difference was defined as p < 0.01.

Results

General information of patients

A total of 42 NK/T-LAHS patients were recruited in our center, 30 cases were male (71.43%), 12 cases were female (28.57%). The age of the patients ranged from 14 to 78-year-old, and the median age was 34.5-years ().

Table 1. Patient demographics.

The clinical and laboratory characteristics of the NK/T-LAHS patients

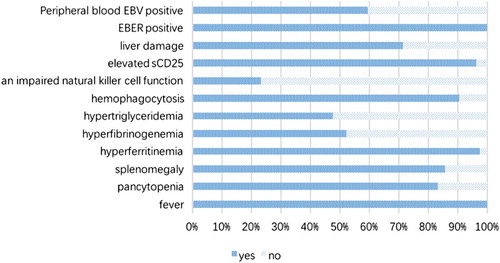

Findings from analysis of clinical manifestations and laboratory tests of NK/T-LAHS patients showed that among the HLH diagnosis-related indicators, the most significant manifestations were fever, increased level of serum ferritin, increased levels of sCD25, and hemophagocytic phenomenon, with the rate matching the positive diagnostic criteria were 100, 97.62, 96.43, and 90.48%, respectively. Next were reduction of blood cell (83.33%), and splenomegaly (85.71%); while hypertriglyceridemia and low fibrinogenemia were nearly half of the diagnostic criteria at 47.62 and 52.38%, respectively. The incidence of NK cell activity reduction in NK/T-LAHS patients was only 23.33% ().

Figure 1. Abnormal incidence of clinical manifestations and laboratory test indices in patients with NK/T-LAHS.

The finding from the analysis of other secondary indicators showed that while not included in the diagnostic criteria of HLH, there was a high incidence of liver function impairment (71.43%) in NK/T-LAHS patients. Furthermore, NK/T-LAHS patients with pathological examination revealed the EBER-positive rate of 100%, while the positive rate of peripheral blood EBV was 59.52%. It should be noted that beginning in 2015, our hospital started serum EBV detection, and have since found of the 25 cases of peripheral blood EBV-positive patients, 6 patients were tested for serum EBV, and all 6 cases were positive. Among the 42 NK/T-LAHS patients, HLH appeared in 4 patients (9.52%) during and after chemotherapy, while 38 patients (90.48%) had HLH at the time of initial diagnosis.

Treatment effect on NK/T-LAHS patients

Initial induction therapy of NK/T-LAHS patients

Among 42 NK/T-LAHS patients, 36 cases were enrolled in initial induction therapy, of which 9 patients underwent HLH-94 regimen, 5 patients underwent HLH-04 regimen, 5 patients were treated with glucocorticoids as the main therapy, and 17 patients received chemotherapy for tumors. The response of the first induction therapy was analyzed, 2 patients achieved CR, accounting for 5.6% of evaluable patients; 10 patients achieved PR, accounting for 27.8%; 24 patients had no NR to the induction therapy; and the OR rate was 33.4%. In all, 14 patients received HLH-94 or HLH-04 regimen treatment, and 5 patients achieved PR, and the OR rate was 35.7%. For the17 patients that received chemotherapy for tumors, 5 patients achieved PR, 2 patients achieved CR, and the OR rate was 41.2% ().

Table 2. Patients’ initial induction therapy.

Salvage therapy for NK/T-LAHS patients

Some patients had no response to initial induction therapy, while other HLH relapse patients failed upon re-induction thus received salvage treatment, which mainly comprised DEP regimen. A total of 15 patients received DEP regimen (2 of whom were not enrolled in the initial treatment regimen and received DEP in our center). One patient achieved CR criteria of 6.7%, seven patients achieved the PR criteria of 46.7%, and the OR was 53.4%.

The application of autologous HSCT and allogeneic HSCT in NK/T-LAHS patients

Of the 14 patients who were responsive to initial induction therapy and salvage therapy (6 of whom were responsive to initial induction therapy, however, HLH relapse failed upon re-induction thus received salvage treatment), 2 patients received auto-HSCT after initial treatment reached PR criteria, 1 patient died (survival time of 3 months), and 1 patient survived (survival time of 21 months); 6 patients received allogeneic HSCT (3 patients achieved CR, 3 patients achieved PR), of which 1 patient died of HLH recurrence (survival time of 4 months), 1 patient died of infection (survival time of 12 months), and 4 patients survived, (survival times of 5, 5, 89, and118 months, respectively). Additionally, there were six patients who responded effectively to initial induction therapy and salvage therapy but without transplant (all subjects died), the median survival time was 2.5 months. One patient who did not achieve PR from the initial treatment underwent allo-HSCT died of HLH recurrence (survival time of 4 months). Among the 27 patients who had failed to achieve OR from the initial treatment and did not receive transplantation, 24 patients died, 1 patient was lost to follow-up, and 2 patients survived, with a median survival time of 1.0 months.

Survival analysis of NK/T-LAHS patients

Overall survival analysis of NK/T-LAHS patients

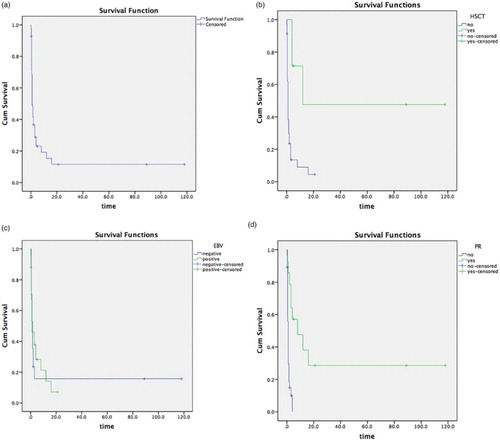

The survival time was counted until 1 August 2016. For the 42 NK/T-LAHS patients, 1-month survival rate was 48.9%, 2-month survival rate was 36.7%, 3-month survival rate was 28.8%, 6-month survival rate was 23.0%, and 12 month survival rate was 15.4%. Survival curve is depicted in (A). This data confirms that NK/T-LAHS is a serious life-threatening disease with poor prognosis.

Figure 2. (A) Overall survival curves of patients with NK/T-LAHS. (B) Survival curves of NK/T-LAHS patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation vs. without allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. (C) Survival curves of NK/T-LAHS patients with EBV-positive vs. EBV-negative peripheral blood. (D) Survival curves of NK/T-LAHS patients who achieved OR remission with initial induction therapy or those who did not achieve OR after initial induction therapy.

The effect of all indicators of prognosis of patients with NK/T-LAHS

The factors influencing the survival time of patients with NK/T-LAHS were analyzed by multivariate logistic regression, which examined the effect of six indicators such as gender, age, whether initial induction treatment achieved OR, whether subject received allo-HSCT, whether peripheral blood EBV was positive, and whether HLH appeared during and after chemotherapy on NK/T-LAHS patients’ survival time. Results indicated that receiving allo-HSCT (p = 0.000) ((B)), EBV-positive peripheral blood (p = 0.004) ((C)), and achieving OR from initial induction therapy (p = 0.007) ((D)) had statistical significance on NK/T-LAHS patients’ prognosis. However, gender (p = 0.181), age (p = 0.056); or whether HLH appeared ‘during chemotherapy’ and ‘after chemotherapy’ (p = 0.081) in patients with NK/T-LAHS did not impact the prognosis of NK/T-LAHS patients.

Discussion

Malignant neoplasms are one of the most common causes and risk factors for HLH [Citation4,Citation5]. Hematologic malignancies are often seen, especially NK/T cell lymphoma, which accounts for 35% of HLH-related tumors [Citation6]. Thus NK/T cell lymphoma plays an important role in HLH induction. HLH can occur in the beginning or recurrence of the tumor, and can also occur during or after chemotherapy. However, the exact pathogenesis is unclear, but it is suggested that it might be due to hyperactivation of macrophages or massive secretion of cytokines by tumor cells and/or tumor-activated lymphocytes. Some studies have suggested that the tumor itself or treatment options such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy further puts the patients in immunosuppressed state, thus they are prone to persistent infection, further activating lymphocytes that ultimately results in release of large amounts of cytokines [Citation20]. Our study showed that HLH was found in 4 patients (9.52%) during or after chemotherapy, and HLH was found in 38 patients (90.48%) at the time of initial diagnosis. However, our study showed that the occurrence time of HLH did not have an effect on prognosis of NK/T-LAHS patients (p = 0.081).

Active HLH disease progresses rapidly, and without timely and effective treatment, the median survival time is only 1–2 months and 1-year overall survival rate is only 5% [Citation21]. LAHS patients had a worse prognosis in all HLH patients [Citation4,Citation5,Citation10,Citation11]. In LAHS, NK/T cell lymphoma had a worse prognosis than B-cell lymphoma and had a higher mortality rate [Citation10,Citation12,Citation13], with 5-year survival rate of <15% [Citation10]. Our study found that the survival rate from 1-month to 12-month drastically reduces. This underscores the fact that NK/T-LAHS is a high mortality disease with poor prognosis. Therefore, for NK/T-LAHS patients, timely and effective treatment is particularly important. Owing to the lack of prospective studies, it remains unclear whether the primary treatment for HLH or for malignant tumors, or for the combination of the two treatments yields better results; thus should be explored in future studies [Citation22,Citation23]. Current standard HLH treatment regimens include the HLH-94 and HLH-04 regimens, which increases disease remission rates from <10% in the past to around 70% presently [Citation24]. From our data, HLH-94 and HLH-04 regimen still have a certain value in NK/T-LAHS patients; and the initial induction of remission rate can reach 35.7%. Additionally, chemotherapy of tumors also benefited some patients, with an OR of 41.2%, and our study showed that the initial induction of remission to achieve OR or not (p = 0.007) affected NK/T-LAHS patients’ prognosis. Moreover, patients with NK/T-LAHS who responded to initial induction therapy had a better prognosis than those who did not.

For patients who do not respond to current standard treatment regimens, there is an urgent need to actively explore effective salvage regimens. However, at present, there is no unified recommendation for salvage regimen within China nor internationally; most are case reports or small samples clinical reports, in which infliximab and CD25 monoclonal antibody have been used as salvage therapy [Citation25,Citation26]. Some research showed that rituximab-containing regimens appeared well-tolerated and improved clinical status in 43% of patients [Citation27]; however, our center did not find significant improvement compared with a nonrituximab regimen in our small series of EBV-HLH (unpublished observations) [Citation19]. We identified the lineage of EBV-infected cells from EBV-HLH patients by immunohistochemistry double staining and identified most of them as CD31/EBER1. This suggests that EBV predominantly infects T cells in Chinese populations, which could explain the non-superiority of rituximab in Chinese adult EBV-HLH [Citation19]. The DEP protocol [Citation19], which was presented by Yini Wang from our research group, is the first prospective clinical study in adult patients with refractory HLH. The protocol achieved a response rate of 76% in adult HLH patients who failed to HLH-94 or HLH-04 regimen induction therapy, and provides a great help for patients who transition from the induction therapy to DEP treatment and onto allo-HSCT. Our data showed that the overall response rate of DEP was 53.4% in NK/T-LAHS patients with HLH-94 and HLH-04 initial induction failure, providing a bridge for the transition of allo-HSCT for NK/T-LAHS patients. Therefore, NK/T-LAHS patients who fail initial induction therapy can receive salvage therapy.

Since the first case of HLH patients in 1986 who received the successful implementation of allo-HSCT was reported [Citation28], allo-HSCT in HLH patients has received more attention. Allo-HSCT for patients with primary HLH is an important treatment, can achieve higher overall survival rate [Citation29], and for secondary HLH patients who fail chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy, allo-HSCT is the only cure [Citation30]. Allo-HSCT also plays an important role in the treatment of NK/T cell lymphoma [Citation9]. Our data showed that six patients responded to the initial induction therapy and salvage therapy and received allo-HSCT, of which four had long-term survival of 5, 5, 89, 118 months. For six patients who responded to initial induction therapy and salvage therapy but without transplantation the median survival time was 2.5 months and all patients died. Patients whose initial treatment did not achieve OR and who did not undergo transplantation died within 1 month. This shows that patients with effective NK/T-LAHS initial induction therapy and salvage therapy should be actively engaged in allo-HSCT. Allo-HSCT (p = 0.000) had a significant effect on the prognosis of patients with NK/T-LAHS, thus may be an effective treatment strategy for long-term survival.

The detection rate of EBV-DNA in patients with NK/T-cell lymphoma was higher than 90%; through quantitative detection of the EBV-DNA level in patients, we found that patient with higher EBV-DNA expression had poorer clinical stage and prognosis than EBV-DNA low expression patients, suggesting that the level of serum EBV-DNA is associated with NK/T cell lymphoma patients’ prognosis [Citation8]. EBV infection is one of the most common causes of secondary HLH [Citation31]. Studies from our center by Wang et al. [Citation32] have shown that comparing HLH patients with EBV-DNA <1 × 105 copies/ml to those with EBV-DNA >1 × 105, and comparing those with EBV-DNA <1 × 106 copies/ml to EBV-DNA ≥1 × 106 copies/ml, patients with low copy number had a longer survival time. Significantly longer survival (p = 0.018) was observed in patients whose EBV-DNA was reduced >100-fold compared with those EBV-DNA was reduced <100-fold after treatment. This indicates the close relationship between EBV and the prognosis of HLH patients. Demonstrated by our data, EBV-positive peripheral blood (p = 0.004) had an effect on the prognosis of patients with NK/T-LAHS; EBV-positive peripheral blood was a poor prognostic factor for NK/T-LAHS.

Conclusions

NK/T-LAHS is a disease of poor prognosis and high mortality. Allo-HSCT, EBV-positive peripheral blood and initial induction achieving OR remission affect the prognosis of NK/T-LAHS patients. Subjects who responded to initial induction therapy had a better prognosis than those who did not. Allo-HSCT should be actively administered in patients whose initial induction therapy and salvage therapy are effective, and it may be an effective way to prolong the survival of NK/T-LAHS patients. EBV-positive peripheral blood is a poor prognostic factor for NK/T-LAHS patients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Henter JI, Elinder G, Ost A. Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The FHL Study Group of the Histiocyte Society. Semin Oncol. 1991;18(1):29–33.

- Tothova Z, Berliner N. Hemophagocytic Syndrome and Critical Illness: New Insights into Diagnosis and Management. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30(7):401–412. doi: 10.1177/0885066613517076

- Chandrakasan S, Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Pediatr. 2013;163(5):1253–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.053

- Parikh SA, Kapoor P, Letendre L, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(4):484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.12.012

- Rivière S, Galicier L, Coppo P, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adults: a retrospective analysis of 162 patients. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1118–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.034

- Lehmberg K, Nichols KE, Henter JI, et al. Study group on hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis subtypes of the histiocyte society. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with malignancies. Haematologica. 2015;100(8):997–1004.

- Lee WJ, Jung JM, Won CH, et al. Cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a comparative clinicohistopathologic and survival outcome analysis of 45 cases according to the primary tumor site. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(6):1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.023

- Suzuki R, Yamaguchi M, Izutsu K, et al. Prospective measurement of Epstein-Barr virus-DNA in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Blood. 2011;118(23):6018–6022. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354142

- Tse E, Kwong YL. How I treat NK/T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2013;121(25):4997–5005. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-453233

- Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, et al. Nationwide survey of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2007;86(1):58–65. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.07012

- Otrock ZK, Eby CS. Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and outcomes of adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):220–224. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23911

- Yu JT, Wang CY, Yang Y, et al. Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: experience in adults from a single institution. Ann Hematol. 2013;92(11):1529–1536. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1784-3

- Sano H, Kobayashi R, Tanaka J, et al. Risk factor analysis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma-associated haemophagocytic syndromes: a multicenter study. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(6):786–792. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12823

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004:Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569

- Collaborative Study to Evaluate the Proposed 1st WHO International.

- Marsh RA, Allen CE, McClain KL, et al. Salvage therapy of refractory hemophagocytic lymphohisocytosis with alemtuzumab. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(1):101–109. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24188

- Henter JI, Aricò M, Egeler RM, et al. HLH-94: a treatment protocol for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. HLH study group of the histiocyte society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28(5):342–347. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199705)28:5<342::AID-MPO3>3.0.CO;2-H

- Wang Y, Huang W, Hu L, et al. Multi-center study of combination DEP regimen as a salvage therapy for adult refractory hemopgagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126(19):2186–2192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-05-644914

- Celkan T, Berrak S, Kazanci E, et al. Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric cases: a multicenter study from Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51(3):207–213.

- Janka GE. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140(3):221–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00443367

- Lehmberg K, Sprekels B, Nichols KE, et al. Malignancy-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children and adolescents. Br J Haematol. 2015;170(4):539–549. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13462

- Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes an update. Blood Rev. 2014;28(4):135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.03.002

- Trottestam H, Horne A, Aricò M, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: long-term results of the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Blood. 2011;118(17):4577–4584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-356261

- Henzan T, Nagafuji K, Tsukamoto H, et al. Success with infliximab in treatment tefractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(1):59–61. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20462

- Olin RL, Nichols KE, Naghashpour M, et al. Successful use of the anti-CD25 antibody daclizumab in an adult patient with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(9):747–749. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21236

- Chellapandian D, Das R, Zelley K, et al. Treatment of Epstein Barr virus-induced haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapeutic regimens. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(3):376–382. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12386

- Fischer A, Cerf-Bensussan N, Blanche S, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):267–270. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(86)81002-2

- Jordan MB, Filipovich AH. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single(big) step. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(7):433–437. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.232

- Baker KS, Filipovich AH, Gross TG, et al. Unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(3):175–180. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.133

- Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, et al. Nationwide survey of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2007;86(1):58–65. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.07012

- Wang J, Wang Y, Wu L, et al. PEG-aspargase and DEP regimen combination therapy for refractory Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0317-7