ABSTRACT

Background: Regarding the importance of oral and dental health in patients with hemoglobinopathies and also due to the different results of different studies in this background, in patients with beta thalassemia (BTM) and sickle cell disease (SCD), this study aimed to evaluate and compare the oral and dental manifestations of patients with BTM and SCD.

Material and methods: In this cross-sectional study during the years 2014–2017, a total of 175 patients (with documented BTM or SCD attending to Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, and Tabriz cities central hospitals) were randomly recruited. Required information was gathered through a thorough physical examination of the oral cavity in a private office and a face-to-face interview by an orthodontist and two dentists. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0.

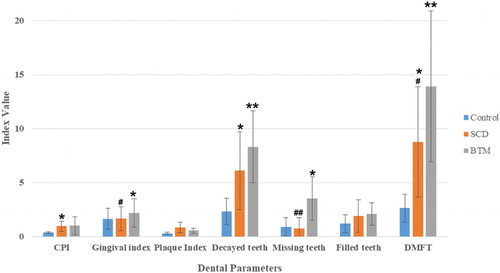

Results: In general, 120 diagnosed patients with BTM (88 males and 32 females) and 55 patients with SCD (25 males and 30 females) attending to Iran largest cities, central hospitals were randomly recruited. We found a significantly higher prevalence (p < .05) of some oral manifestations among the BTM patients (Gingival Index = 2.18 ± 1.300, 1.64 ± 0.963; Decayed teeth = 8.31 ± 3.330, 2.33 ± 1.221; Missing teeth = 3.51 ± 2.016, 1.19 ± 0.820; DMFT = 13.92 ± 7.001, 2.63 ± 1.301) than the apparently healthy people.

Conclusion: Finally, the study gives an insight into the various oral and dento-maxillofacial manifestations of SCD and BTM and also reveals an association that exists between the oral and dento-maxillofacial manifestations and systemic health in these patients, thus stressing the importance of the concise and periodic examination of these individuals to perform appropriate preventive dental and periodontal care, and the facilitation of the management of the disease.

Introduction

The sickle cell disease (SCD), thalassemia, and other hemoglobinopathies represent a major group of inherited disorders of hemoglobin synthesis. Hemoglobinopathies, mainly thalassemia and SCD, are globally prevalent. Thalassemia refers to a group of congenital and autosomal recessive hemolytic anemias, involving deficiencies in the synthesis of either the alpha or the beta polypeptide chains of hemoglobin [Citation1–3].The homozygous form of the disease, which is known as Beta-thalassemia major (BTM), is one of the most frequent monogenic diseases in the Middle East, Asia, and the south pacific region. In Iran, which is located in the global thalassemia ring, about 3 million carriers and 25,000 individuals with BTM are registered [Citation4,Citation6].

BTM is found in homozygous patients with an intense alteration of hemoglobin beta-chain production. Patients with BTM usually present within the first two years of life with inadequate growth rate, mild or severe anemia, and skeletal anomalies during infancy. In their youth, secondary sex features are deferred, hemosiderosis (due to Iron overload) is frequent, and almost all patients have ashen-gray skin color due to the combination of pallor and jaundice [Citation5] . Patients with thalassemia can experience an enlargement of their upper jaw, which is also known as the chipmunk face. The chances of the migration and spacing of upper anterior teeth also increase, and there may be varying degrees of malocclusion in such patients too [Citation7]. Other than that, the teeth of patients who have thalassemia might be discolored and have short crowns and roots [Citation8,Citation9]. Patients with BTM also present maxillary hyperplasia, pathologic fractures, cholelithiasis, systolic ejection murmur, and dental malocclusion [Citation10,Citation11].

On the other hand, SCD is a chronic condition that has been linked to hypoxia. The pathophysiology of the disease is said to have resulted from the polymerization of hemoglobin S in red blood cells under hypoxic conditions, which results in the occlusion of blood vessels and ineffective erythropoiesis. Symptoms of SCD may manifest in soft tissues as well as in bony structures of the maxillofacial region. The common oral manifestations of SCD include delay in tooth eruption, atrophy of the tongue papillae, paleness of the oral mucosa, impaired dentine mineralization, orofacial pain, mandibular osteomyelitis, craniofacial skeletal alterations such as exaggerated growth/protrusion of the midface, maxillary expansion, a predominance of vertical growth, a convex profile, and maxillary protrusion [Citation12–17]. Maxillofacial changes in SCD patients occur as the consequence of hyperplasia and compensatory expansion of the bone marrow, resulting in the maxillary expansion, exaggerated protrusion/growth of the midface, a predominance of vertical growth, mandibular retrusion, a convex profile, and maxillary protrusion. The oral, dental, and facial manifestations of BTM and SCD are frequent and intense, and are the consequences of the bony changes occurring due to ineffective erythropoiesis, with the formation of a bone expanding the erythroid mass. Important malocclusions have been observed, in previous investigations, as a consequence of severe maxillary protrusion, with the development of overbite and anterior open bite [Citation17,Citation18].

The mandible is generally less protruded than the upper jaw, apparently because the dense mandibular cortical layer resists expansion. In addition, the existence of orbital hypertelorism is a frequent finding [Citation19,Citation20]. Regardless of the impact of BTM and SCD on the oral tissues and structure, the dental health of these patients is essential to prevent dental infections that could precipitate a vaso-occlusive crisis or act as a bacterial source for the development of the mandible that has lost its blood supply.

Rare studies have examined the relationship between SCD, BTM, and oral health, and the results have been contradictory [Citation7,Citation21,Citation22], so this investigation aimed towards a comparative evaluation of the oral and the dento-maxillofacial manifestation of the patients with BTM and SCD within the Iranian population.

Material and methods

Study design and subjects

In this cross-sectional study during the years 2014–2017, a total of 175 patients (with documented BTM or SCD attending to Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan and Tabriz cities, central hospitals) were randomly selected and considered as the study population. We used the oral and dental examination data of 100 apparently healthy people (age and sex matched), who were referred to private offices for annual checkups, as the control population. This information had been collected from their files with prior permission. All the participants had similar socioeconomic backgrounds and were age matched. The study has been confirmed by the ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The written informed consent obtained from each participant, and the study was carried out in accordance with the principals of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All the patients were regularly attending the Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization centers around the country for repeated blood transfusion, or were admitted in the wards of general hospitals in each city. The eligibility criterions for the inclusion in the study were as follows: a diagnosis of SCD HbSS or BTM in the patients’ medical records, not suffering from a painful crisis at the time of the survey for the SCD patients, no medical conditions other than SCD or BTM, no emergency dental appointment in the past three months, written consent, and willingness to participate in the study. The subjects were excluded from the study in the case of incomplete data and/or having any mental or systemic disorders, other than SCD and BTM.

Dental and oral examination

Required information was gathered through a thorough physical examination of the oral cavity in a private office and a face-to-face interview by an orthodontist and two dentists. A disposable mirror, Community Periodontal Index (CPI) probe, flashlight, and sterilized gauze were used to examine the oral and dental health status. Teeth that were missing for any reason, other than dental caries, according to the subjects’ self-reports were excluded. Gingival bleeding, calculus, and periodontal pocket depth were measured with William's periodontal probe, according to the CPI. Possible CPI scores were: 0 (healthy), 1 (bleeding after probing, observed directly or by mouth mirror), 2 (calculus detected during probing, but the entire black band of the probe remained visible), 3 (4–5-mm periodontal pocket depth), and 4 (>6-mm periodontal pocket depth). For the examination of the oral and dental health status, we used an exam sheet to determine the DMFT (decayed, missing, and filled teeth), GI (Gingival index), PI (Plaque Index) indices, and bleeding on probing, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [Citation23]. Angle's classification was used to evaluate occlusion, as described previously [Citation24].

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0. In order to compare the quantitative variables of the study, firstly, the normal distribution of data was analyzed with the use of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare the frequency distributions of the quantitative variables of the study. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

In general, 120 diagnosed patients with BTM (88 males and 32 females) and 55 patients with SCD (25 males and 30 females), attending to Iran largest cities central hospitals, were randomly recruited. The mean ages of the patients with SCD, BTM, and healthy control were 19.2 ± 2.91, 18.8 ± 1.124, and 19.3 ± 3.211 years, respectively. Patients with BTM and SCD were hospitalized on an average of 4.36 (range, 1–12) and 5.82 (range, 1–16) times per year, respectively. The majority of patients with BTM (90.1%) and SCD (81.9%) visited the dentist only when they experienced dental pain.

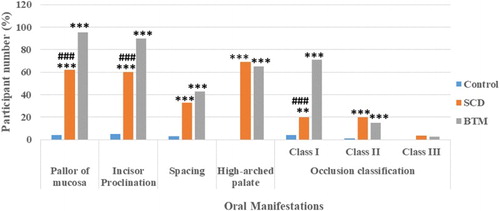

As shown in and , the results of this study showed that some of the dental parameters or oral manifestations were significantly different in patients with SCD, BTM, and healthy subjects. We found that the mean value for the GI and the number of decayed teeth, missing teeth and the overall DMFT in BTM patients were significantly increased compared to healthy subjects (p < .05, p < .01, p < .05, and p < .01, respectively). In addition, there was a significantly (p < .05) higher number of decayed teeth in patients with SCD (6.10 ± 3.620) as compared with healthy subjects (2.33 ± 1.221). It was also found that the mean value for the CPI and DMFT was significantly increased compared to healthy subjects (p < .05). In addition, we observed a significant high prevalence in mean value for the GI, the number missing teeth, and the overall DMFT count in BTM in comparison with SCD patients (p < .05, p < .01, p < .05 respectively) ().

Figure 1. CPI, GI, PI, and DMFT mean values for SCD and BTM patients. *indicate significant differences in comparison with control. # indicate significant differences in comparison with BTM (*, #p < .05, **, ##p < .01). Notes: CPI; Community Periodontal Index, SCD: Sickle Cell Disease; BTM: Beta-Thalassemia Major.

Figure 2. Comparison of frequency of each oral manifestation between healthy control, SCD, and BTM. *indicate significant differences in comparison with control. # indicate significant differences in comparison with BTM (***,###p < .001, **,##p < 0.01). Notes: SCD: Sickle Cell Disease; BTM: Beta-Thalassemia Major.

The oral manifestations in 120 BTM, 55 SCD patients, and in 100 healthy controls are shown in . BTM and SCD patients had significantly higher frequencies of all oral manifestations (other than class III occlusion) in comparison with healthy controls (p < .001 for all). Also when we made a comparison between BTM and SCD, it was found that patients with BTM had a significantly (p < .001) higher prevalence of pallor of mucosa, incisor proclination and class I occlusion compared with SCD patients.

In the present study, there was no significant relationship between the incidence of dento-maxillofacial manifestations and onset of blood transfusion, age at diagnosis, the blood transfusion intervals, and regular use of Deferoxamine and blood transfusion.

Discussion

The incidence of oral and dental issues in BTM and SCD is higher than that in many other disorders. Investigations around the world have shown a frequency rate of 45–50% for such manifestations [Citation25]. The most predominant manifestations of patients with SCD or BTM in the head and maxillofacial area are the protrusion of the malar bones and the premaxilla, which is due to the hyperplasia of the bone marrow. In addition, many oral manifestations of BTM and SCD that affect the gingival tissue, oral mucosa, nerve supply, mandible, and tooth enamel and pulp have been reported previously [Citation19,Citation20,Citation25–27]. Regarding the importance of oral and dental health in patients with hemoglobinopathies and also due to the different results of different studies in this background, in patients with thalassemia and SCD, this study aimed to evaluate and compare the oral and dental manifestations of patients with BTM and SCD.

We found no significant differences in mean CPI, gingival, plaque indices, and decayed and filled teeth between patients with SCD and BTM. The frequency of mean DMFT and missing teeth differed significantly between the groups (p < .05). Missing tooth was rarely prevalent and the mean DMFT was lower among patients with SCD than among patients with BTM. These findings are in line with the populations of the studies conducted among the Brazilians [Citation28], Sudanese [Citation29], and Saudis [Citation30], with SCD.

Singh et al. [Citation21], Al Alawi et al. [Citation18], and Navpreet Kaur et al. [Citation31] concluded that patients with Beta thalassemia had a higher prevalence regarding the experience of caries (DMFT = 13.33 ± 6.813,7.85 ± 7.071,3.45 ± 4.20) than the healthy controls (DMFT = 3.51 ± 1.131,6.97 ± 3.729,1.82 ± 2.51). These findings are also in accordance with those of the studies conducted among the thalassemic patients of the Iranian population by Mottalebnejad et al. [Citation32], Babaei et al. [Citation26], Ajami et al. [Citation33], and Shooriabi et al. [Citation34]. The high level of dental caries may be attributable to the chronic nature of these life-threatening diseases, because oral health and dental hygiene is not a major concern among these patients. Numerous studies stated that no significant differences existed regarding the periodontal diseases between the patients with SCD and healthy individuals [Citation27,Citation35], which are in line with the findings of our study. Our results, which were in disagreement with the findings of Singh et al. [Citation21] and Guzeldemir et al. [Citation25], suggested that SCD is associated with increased levels of gingivitis and periodontitis in patients with SCD.

In this survey, the most common manifestation observed in SCD and BTM was the pallor of the mucosa and malocclusion, respectively, as has been stated in literature. Previous studies stated that malocclusion seen in SCD or BTM is caused by the proliferation of the marrow within the frontal and facial bones, resulting in a hypertrophy of the osseous structures and a consequent prominence of the lateral margins of the malar eminences, together with an anterior and medial displacement of the developing teeth.

This, in turn, results into clinically apparent proclination, spacing, etc [Citation36–38]. In our survey, most of the patients, among both SCD and thalassemic patients, had class I occlusion (20.1%) and (70.9%), respectively. Among thalassemic patients, the occlusal examination results were compatible with other related studies in Iran and it was approximately similar to the normal Iranian occlusion prevalence (70%), [Citation24,Citation32,Citation39,Citation40]. The frequency of the pallor of the mucosa (p = .022) and incisor proclination (p = .03) among the patients with BTM had significant differences with SCD patients. In addition, we found significant differences in the occlusal class I prevalence between the SCD and BTM patients (p < .05). Class I occlusion was very less among patients with SCD than among patients with BTM and the control group. On the other hand, according to the data, it can be concluded that class II occlusion prevalence among the patients with BTM is less than the normal population, which is in contrast with the conclusions of some studies [Citation32,Citation39,Citation41]. One of the limitations of this study was the circumstance that it was not possible to take patients’ radiographs for more detailed assessments. It is recommended that in future studies, dento-maxillofacial manifestations be evaluated with the use of radiographs. In addition, another limitation was a lack of access to all the patients with SCD or BTM in other provinces of Iran.

In conclusion, the study gives an insight into the various oral and dento-maxillofacial manifestations of SCD and BTM and also reveals an association that exists between the oral and dento-maxillofacial manifestations and systemic health in these patients, thus stressing the importance of the concise and periodic examination of these individuals to perform appropriate preventive dental and periodontal care, and the facilitation of the management of the disease.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Salmeh Kalbassi is a DDS, MDS, Morth Specialist in Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics and is working in UAE, Iran and Oman as private dentist.

Mohammad Reza Younesi is a Hematologist with MSc degree, graduated from Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Vahid Asgary is a Manager in Research and Development Laboratory, Javid Biotechnology Company, Incubator of Pasteur of Iran, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. The thalassaemia syndromes. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- Akcalı A, Kahraman Çeneli S, Gümüş P, et al. The association between thalassemia major and periodontal health. J Periodontol. 2015;86(9):1047–1057. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140639

- Jain D, Warthe V, Colah R, et al. Sickle cell disease in central India: high prevalence of sickle/beta thalassemia and severe dsiease phenotype. Blood. 2015;126(23):4588.

- Valizadeh N, Noroozi M, Hejazi S, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses among thalassemia patients in west north of Iran. Iran J Ped Hematol Oncol. 2015;5(3):145.

- Younesi MR, Louni Aligoudarzi S, Bigdeli R, et al. Alloimmunization against platelets, granulocytes and erythrocytes in multi-transfused patients in Iranian population. Transfus Apher Sci. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.06.003.

- Miri M, Tabrizi Namini M, Hadipour Dehshal M, Sadeghian Varnosfaderani F, Ahmadvand A, Yousefi Darestani S, et al. Thalassemia in Iran in last twenty years: the carrier rates and the births trend. Iran J Blood Cancer. 2013;6(1):11–17.

- Laurence B, George D, Woods D, et al. The association between sickle cell disease and dental caries in African Americans. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26(3):95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01430.x

- Singh J, Singh N, Kumar A, et al. Dental and periodontal health status of Beta thalassemia major and sickle cell anemic patients: a comparative study. JIOH. 2013;5(5):53.

- Hattab FN. Mesiodistal crown diameters and tooth size discrepancy of permanent dentition in thalassemic patients. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013;44(5):e239–e244. doi: 10.4317/jced.51214

- Greene DN, Vaughn CP, Crews BO, et al. Advances in detection of hemoglobinopathies. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;439:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.006

- Helmi N, Bashir M, Shireen A, et al. Thalassemia review: features, dental considerations and management. Electron Physician. 2017;9(3):4003. doi: 10.19082/4003

- Mendes PHC, Fonseca NG, Martelli DRB, et al. Orofacial manifestations in patients with sickle cell anemia. Quintessence Int (Berl). 2011;42(8):701–709.

- Erdogan O, Kisa HI, Charudilaka S. Sickle-cell disease: a review of oral manifestation and presentation of a case with an uncommon complication of the disease. Rangsit J Arts Sci. 2011;3:179–185.

- Maia NG, dos Santos LA, Coletta RD, et al. Facial features of patients with sickle cell anemia. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(1):115–120. doi: 10.2319/012910-61.1

- Wilson BH, Nelson J. Sickle cell disease pain management in adolescents: a literature review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(2):146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.05.015

- Javed F, Correa FOB, Almas K, et al. Orofacial manifestations in patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345(3):234–237. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318265b146

- Ralstrom E, da Fonseca MA, Rhodes M, et al. The impact of sickle cell disease on oral health-related quality of life. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36(1):24–28.

- Al-Alawi H, Al-Jawad A, Al-Shayeb M, et al. The association between dental and periodontal diseases and sickle cell disease: a pilot case-control study. Saudi Dent J. 2015;27(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.08.003

- Cutando SA, Gil MJ, López-González GJD. Thalassemias and their dental implications. Med Oral. 2001;7(1):36–40. 1–5.

- de Matos BM, Ribeiro ZEA, Balducci I, et al. Oral microbial colonization in children with sickle cell anaemia under long-term prophylaxis with penicillin. Arch Oral Biol. 2014;59(10):1042–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.05.014

- Singh J, Singh N, Kumar A, et al. Dental and periodontal health status of beta thalassemia major and sickle cell anemic patients: a comparative study. J Int Oral Health. 2013;5(5):53.

- Fernandes MLMF, Kawachi I, Corrêa-Faria P, et al. Caries prevalence and impact on oral health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0052-4

- Organization WH., et al. Oral health surveys: basic methods. Oxford: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Salem K, Aminian M, Khamesi S., et al. Evaluation of dento-maxillofacial changes in children and adolescent with ß-thalassemia major in northern Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2017;5:5219–5227.

- Guzeldemir E, Toygar HU, Boga C, et al. Dental and periodontal health status of subjects with sickle cell disease. J Dent Sci. 2011;6(4):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2011.09.008

- Babaei N, Tohidast Z, Nematzadeh F., et al. Oral manifestation and complication in patients with thalassemia major. Babol: Daneshvar Medicine; 2008.

- Crawford JM. Periodontal disease in sickle cell disease subjects. J Periodontol. 1988;59(3):164–169. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.3.164

- Luna AC, Rodrigues MJ, Menezes VA, et al. Caries prevalence and socioeconomic factors in children with sickle cell anemia. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26(1):43–49. doi: 10.1590/S1806-83242012000100008

- Hussein MO., et al. Association between sickle cell disease and malocclusion and dental caries among Sudanese children. Khartoum: University of Khartoum; 2016.

- Abed HH, Alsahafi EN, Abdallah MA, et al. The association between DMFT index and haemoglobin levels in 3–6 year-old Saudi children with anaemiaa cross sectional study. Taibah: Journal of Taibah City University Medical Sciences; 2016.

- Kaur N, Hiremath S. Dental caries and gingival status of 3–14 year old beta thalassemia major patients attending paediatric OPD of vanivilas hospital, Bangalore. Arch Oral Sci Res. 2012;2:67–70.

- Motallebnejad M, Noghani A, Tamaddon A, et al. Assessment of oral health status and oral health-related quality of life in thalassemia major patients. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;24(119):83–94.

- Ajami B, Talebi M, Ebrahimi M., et al. Evaluation of oral and dental health status in major thalassemia patients referred to Dr. Sheikh Hospital in Mashhad in 2002. Mashhad: Journal of Mashhad Dental School; 2006.

- Shooriabi M, Zareyee A, Gilavand A, et al. Investigating DMFT indicator and its correlation with the amount of serum ferritin and hemoglobin in students with beta-thalassemia major in ahvaz, south west of Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2016;4(3):1519–1527.

- Arowojolu M, Savage K. Alveolar bone patterns in sickle cell anemia and non-sickle cell anemia adolescent Nigerians: a comparative study. J Periodontol. 1997;68(3):225–228. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.3.225

- Alhaija ESA, Hattab FN, Al-Omari MA. Cephalometric measurements and facial deformities in subjects with β-thalassaemia major. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24(1):9–19. doi: 10.1093/ejo/24.1.9

- Kukuła K, Plakwicz P. Oral pathology: exostosis deforming face features. Br Dent J. 2016;221(2):50–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.514

- Saraswathi T. Shafer’s textbook of oral pathology. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2009;13(1):46.

- Baharvand M, Soleimani M, Manifar S, et al. Oral health-related quality of life and treatment needs in a group of Iranian dental patients. J Int Dent Med Res. 2016;9(1):23–28.

- Nakhaee N, Navabi N, Rohani A., et al. Assessment of oral health-related quality of life: comparison of two measurement tools. J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol. 2016;9:141–147.

- Salehi M, Farhud D, Tohidast T, et al. Prevalence of orofacial complications in Iranian patients with-thalassemia major. Iran J. Public Health. 2007;36(2):43–46.