ABSTRACT

Objectives: Pain is common in women with sickle cell disease (SCD), but the prevalence of dyspareunia in this unique patient population is unknown. In this study, we sought to determine whether chronic pain is associated with an increased prevalence of dyspareunia in premenopausal women with SCD.

Methods: A cross-sectional study of premenopausal women with SCD was systematically assessed for symptoms of dyspareunia and chronic pain using a standard questionnaire. These results were correlated with each subject's clinical pain phenotype determined by a review of the patient's electronic medical record.

Results: Ninety-one premenopausal women with SCD were examined. Thirty-two percent of the women reported dyspareunia. Women with dyspareunia were more likely to have a history of chronic pain (90% versus 61%, p = .006), report more pain days per week (median (interquartile range): 6 (4–7) vs. 3 (0–7), p = .005)), and had a higher oral morphine equivalent dose (145 (45–226) mg vs. 60 (9–160) mg, p = .030). Using a multivariable classification tree analysis, number of days of pain experienced per week was an important predictor of dyspareunia (p = .001).

Conclusion: Dyspareunia is common in women with SCD, and more common in women with SCD and chronic pain. Providers should assess women with SCD for dyspareunia, especially those with a chronic pain syndrome.

Introduction

Dyspareunia, or recurrent or persistent pain with sexual activity that causes marked distress or interpersonal conflict, affects 12–22% of women, but may be even more common in women with chronic pain syndromes [Citation1–3]. Although the etiologies of dyspareunia are typically thought to be complex and multifactorial, there is evidence to suggest that central mechanisms also contribute [Citation4] since up to 20% of women with dyspareunia carry the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, a chronic pain syndrome characterized by central sensitization [Citation3]. Central sensitization to pain may also contribute to the chronic pain syndrome of sickle cell disease (SCD). Thus, it is possible that dyspareunia is more common in women with SCD with chronic pain.

SCD is a hereditary hematologic disease complicated by acute and chronic pain [Citation5,Citation6]. Due to a missense mutation in the sixth codon of the beta-globin gene, sickle hemoglobin polymerizes under hypoxic conditions and causes sickle-shaped erythrocytes [Citation7]. Poorly able to traverse the microvasculature, sickle cells can cause vaso-occlusion, ischemia, and infarct [Citation7,Citation8]. The most common sequelae of sickle cell-induced vaso-occlusion are episodes of acute pain secondary to tissue injury [Citation8]. These intermittent episodes of pain, which occur about once per year in a child with SCD, evolve into a daily, chronic pain syndrome in approximately 50% of adults [Citation9,Citation10]. More than the sum of damage done to tissues, the mechanism of chronic pain involves peripheral and central sensitization due to inflammation, neuronal injury, and plasticity [Citation11]. The end result is often an adult with hyperalgesia and generalized pain and potentially dyspareunia.

We conducted a cross-sectional cohort study of premenopausal women with SCD and tested the hypothesis that the prevalence of dyspareunia is higher among premenopausal women with SCD who have chronic pain compared to those who do not. We secondarily evaluated the influence of dyspareunia on patient quality of life and mental health.

Methods

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the association between dyspareunia symptoms and a chronic pain phenotype in women with SCD. Study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital and Medical College of Wisconsin. After informed consent, we administered a standardized questionnaire that assessed for dyspareunia symptoms to a convenience sample of sexually active, premenopausal women ≥18 years of age with SCD who attend the Adult Sickle Cell Clinic at Froedtert Hospital in Milwaukee, WI.

Since few validated questionnaires for dyspareunia exist, the questions regarding dyspareunia and subject quality of life were adapted from two sources used clinically at our institution: (1) A modified John Hopkins University's Dyspareunia and Vulvar Pain Center new patient questionnaire (see supplemental figure), and (2) Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) screen for depression [Citation12]. PHQ-9 was administered to determine if there was an association between dyspareunia symptoms and depression. Each subject's clinical phenotype was determined by a systematic review of the electronic medical record for SCD and gynecologic medical history, medications, laboratory values, and emergency department and hospital admissions in the year prior to the study.

Key definitions

Dyspareunia: A persistent superficial or deep pain during or after sexual intercourse noted to occur on more than one occasion.

Chronic pain: A report of pain on 3 or more days per week for 6 months or the requirement of daily opioids for the management of pain.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the report of dyspareunia. A Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test was used to compare the difference of continuous or ordinal variables between groups. A Chi-square or a Fisher's exact test was used to examine the associations between categorical variables and groups. Multivariable regression analysis was done by using a classification tree analysis (CART). A classification tree analysis was used to examine important factors in recurrent dyspareunia. The CART analysis was specifically used for this study because (1) the method allows for the inclusion of all predictor variables, regardless of established or possible interactions; (2) the method allows for inclusion of data that are missing-at-random; and (3) as we suspected that patients with chronic pain would be markedly different than those with no chronic pain, we selected this method because it is the best regression technique available when interactions between variables are predicted to be asymmetric [Citation13]. The tree was optimized by Gini with a 10-fold cross-validation. The split criteria were 10 for parent node and 5 minimum for the terminal nodes to mitigate over-fitting of the model [Citation13]. The variables included in the tree model were demographics (age, genotype), SCD characteristics (presence of chronic pain, duration/severity of chronic pain, number of pain days per week, use of red cell transfusions, opioid equivalent dose (mg), number of emergency departments (ED) or hospital admissions in the last 12 months, presence of depression, and PHQ-9 score), gynecological history (presence of a monogamous relationship, age at first intercourse, contraception use and type, history of pregnancy, delivery types, known sexually transmitted infections, known amenorrhea, history of sexual trauma, tampon use, and presence of any pelvic pathology), and dyspareunia history (sexual age when sexual pain was first noted, presence of sexual pain after delivery or abortion, pain-free intercourse episodes ever). Median and interquartile range (IQR) were used as a summary of a continuous or ordinal variable. A two-sided p-value of <.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were done by using SAS9.4, SPSS 23 for Windows and Salford Systems CART.

Results

Ninety-one women with SCD completed the questionnaires. Median age of the cohort was 29 years (range: 18–48) and 67% had HbSS (other genotypes were SC, Sβ-thalassemia+, and SO-Arab). Dyspareunia was reported in 32% of subjects.

Univariate associations with dyspareunia

Dyspareunia was significantly associated with chronic pain (p = .006). Additionally, compared to subjects without dyspareunia, those with dyspareunia reported more days of pain per week (median (IQR): 6 (4–7) vs. 3 (0–7), p = .005) and required higher doses of morphine milligram equivalents (median (IQR): 145 (45–226) mg vs. 60 (9–160) mg, p = .030) (). Consistent with prior literature, dyspareunia was associated with higher number of pregnancies (2 (1–4) vs. 1 (0–2), p = .026), with the start of the dyspareunia being significantly associated with a combined history event of previous pregnancy, delivery, or abortion (p = .027) ().

Table 1. SCD and gynecological variables in patients with dyspareunia in comparison to those without dyspareunia.

Dyspareunia was also significantly related to reports of lower quality of life (). In comparison to those with no dyspareunia, subjects with dyspareunia reported that their pain had a greater impact on their relationships at work (p = .012), relationships with significant others (p = .001), their sexual activity (p < .0001), physical exercise (p = .002), depression (p < .0001), and a worsened negative body image (p < .0001). In those with dyspareunia, moderate to severe dysfunction was most often reported in the domains of physical exercise, sexual activity, and relationships with their partner.

Table 2. Effect of dyspareunia on quality of life.

Classification tree analysis to predict recurrent dyspareunia

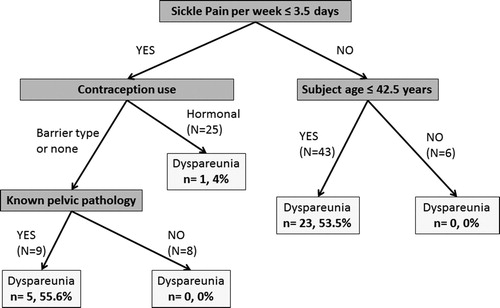

To examine the important predictors of dyspareunia, a multivariable analysis was done by using classification tree analysis. In the best fit model, the number of days per week of pain, patient age, contraception type, and history of known pelvic pathology (i.e. cervicitis, vaginitis, vaginal warts) were associated with dyspareunia. The most significant predictor was number of pain days per week (p = .001) ().

Figure 1. Classification tree analysis representing the significant predictors of dyspareunia in adult female patients with SCD (N = 91). The number of subjects with dyspareunia (n) in each category is compared by a percent to the total number of subjects (N) in each category. The number of days per week where sickle-related pain is noted, patient age, contraception type, and history of known pelvic pathology (i.e. cervicitis, vaginitis, vaginal warts) are the key variables that predict dyspareunia in these patients, with frequency of sickle pain representing the primary predictor. The majority of women with reports of dyspareunia reported sickle pain greater than 3.5 days per week, and were younger than 42.5 years of age (23/43, 54% of those with reported recurrent dyspareunia). In those who experienced fewer days of sickle pain, contraception type used (none or barrier) and vaginal pathology were most predictive (5/9, 56%).

Discussion

For the first time, our study examined dyspareunia in a cohort of premenopausal women with SCD. Thirty-two percent of the women in the cohort reported dyspareunia, 90% of whom had chronic pain. Patients with dyspareunia also reported more pain days per week and required higher opioid doses compared to women without dyspareunia. Number of pain days per week was the most important predictor of dyspareunia in a multivariate regression model. Our study also confirmed that other established risk factors for dyspareunia, such as pregnancy and pelvic pathology, are risks in women with SCD.

The mechanism of chronic pain in adults with SCD is multifactorial, but central sensitization likely plays a major role [Citation14–17]. Inflammation, nerve damage, chronic opioid use, and persistent painful input cause neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system that promotes sensitization to pain [Citation14]. Symptoms of central sensitization, hyperalgesia, and allodynia are present in patients with SCD [Citation14–17]. Moreover, studies have shown that patients with SCD have hypersensitivity to both cold and heat stimuli [Citation18]. These associations have also been well demonstrated in a number of studies of women with dyspareunia. In the general population, women with dyspareunia demonstrate decreased pain thresholds and hyperalgesia [Citation19,Citation20], quantifiable changes to central nociceptors [Citation21,Citation22], and have increased prevalence of other central pain syndrome populations such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia [Citation3,Citation23]. Opioid use, because it also suppresses luteinizing hormone and estradiol secretion in women, may further influence the risk for dyspareunia [Citation24]. One review of the literature identified that patients addicted to heroin (34–85%), methadone (14–81%), or buprenorphine (36–83%) showed higher rates of dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction in comparison to the general population [Citation24]. Taken together, the results from our study and the previous literature suggest that the higher prevalence of dyspareunia in our study of women with SCD compared to studies in the general population may be from chronic pain and opioid use [Citation1,Citation2,Citation25,Citation26].

Quality of life measures are lower for adults with SCD compared to the general population [Citation27,Citation28]. Although many factors may contribute to lower quality of life for patients with SCD, including environmental, psychosocial, and physical factors, acute and chronic pain may affect their quality of life more than any other disease-related complications [Citation29,Citation30]. Dyspareunia is also a well-established and independent factor that variably lowers quality of life as determined by general validated measures, such as the SF-36 [Citation31]. Patients with endometriosis, for instance, many of whom have dyspareunia, reported a large quality of life impact on general health, social functioning, and mental role limitations; moderate impact for physical role limitations and pain; and small impact for physical functioning, vitality, and mental health [Citation31]. Consequently, addressing and managing pain issues, such as dyspareunia, may have a significant and immediate impact in this population.

Our study has limitations. First, the small sample size increases the risk of type I and type II error. However, SCD is a relatively rare disease and large sample sizes are a challenge. Second, the sample was a convenience sample of women with SCD who presented to the clinic. Potentially, they are not representative of the entire clinic population. However, the demographics of the study cohort were similar to the entire clinic population of women in terms of demographics, SCD genotype, and morbidities. Third, the dyspareunia questionnaire was not a validated questionnaire. Although true, no validated questionnaire exists specifically for dyspareunia. The questionnaire used in our study addresses the pertinent questions, which is why it is used in major gynecology clinics throughout the country. Lastly, we were not able to individually evaluate the unique factors that contribute to sexual pain with entry (vulvodynia) or deep pain. While it is known that these two types of dyspareunia have distinct etiologies, we found that in our cohort, there was a significant overlap in the reporting of both superficial and deep sexual pain, with 20 of 29 subjects (69%) experiencing both.

Conclusion

Dyspareunia is a sensitive issue that may not be raised by women with SCD, unless they are specifically asked. Our results demonstrate that dyspareunia is common and significantly affects the quality of life for these patients. Our study supports the conclusion that providers should inquire about and manage dyspareunia in women with SCD, especially in those with a chronic pain syndrome. Future studies aimed at establishing best practice for managing dyspareunia in women with SCD may help improve quality of life for those suffering from a devastating disease.

Supplementary_material.docx

Download MS Word (78.1 KB)Disclosure statement

JJF is a consultant for NKT Therapeutics and receives research funding from NKT Therapeutics and Astellas. The remaining authors do not declare any conflict of interest.

References

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537

- Danielsson I, Sjoberg I, Stelund H, et al. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: results from a population study. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31:113–118. doi: 10.1080/14034940210134040

- Terzi H, Terzi R, Kale A. The relationship between fibromyalgia and pressure pain threshold in patients with dyspareunia. Pain Res Manag. 2015;20:137–140. doi: 10.1155/2015/302404

- Boardman LA, Stockdale CK. Sexual pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:682–690. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181bf4a7e

- Ashley-Koch A, Yang Q, Olney RS. Sickle hemoglobin (HbS) allele and sickle cell disease: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:839–845. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010288

- Hassell K. Sickle cell disease population estimation: application of available contemporary data to traditional methods. 35th Anniversary Convention of the National Sickle Cell Disease Program; Washington, DC; 2007.

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X

- Bunn HF. Pathogenesis and treatment of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):762–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371107

- Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:94–101. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00004

- Ballas SK, Lusardi M. Hospital readmission for adult acute sickle cell painful episodes: frequency, etiology, and prognostic significance. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:17–25. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20336

- Brandow AM, Farley RA, Panepinto JA. Early insights into the neurobiology of pain in sickle cell disease: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(9):1501–1511. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25574

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

- Cook E, Goldman I. Empiric comparison of multivariate analytic techniques: advantages and disadvantages of recursive partitioning analysis. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:721–731. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90041-9

- Tran H, Gupta M, Gupta K. Targeting novel mechanisms of pain in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2017;130(22):2377–2385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-782003

- Treede RD, Meyer RA, Raja SN, et al. Peripheral and central mechanisms of cutaneous hyperalgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:397–421. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90027-C

- Brandow AM, Farley R, Panepinto JA. Neuropathic pain in patients with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:512–517. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24838

- Ezenwa MO, Molokie RE, Wang ZJ, et al. Safety and utility of quantitative sensory testing among adults with sickle cell disease: indicators of neuropathic pain? Pain Pract. 2016;16(3):282–293. doi: 10.1111/papr.12279

- Brandow AM, Stucky CL, Hillery CA, et al. Patients with sickle cell disease have increased sensitivity to cold and heat. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:37–43. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23341

- Sutton KS, Pukall CF, Chamberlain S. Pain ratings, sensory thresholds, and psychosocial functioning in women with provoked vestibulodynia. J Sex Marital Ther. 2009;35:262–281. doi: 10.1080/00926230902851256

- Granot M. Personality traits associated with perception of noxious stimuli in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Pain. 2005;6:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.010

- Bohm-Starke N. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome – pathophysiology of the vestibular mucosa. Scand J Sexol. 2001;4:227–234.

- Chadha S, Gianotten WL, Drogendijk AC, et al. Histopathologic features of vulvar vestibulitis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998;17:7–11. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199801000-00002

- Arnold LD, Bachmann GA, Rosen R, et al. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:617–624. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000199951.26822.27

- Grover S, Mattoo SK, Pendharkar S, et al. Sexual dysfunction in patients with alcohol and opioid dependence. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36(4):355–365. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.140699

- Öberg K, Fugl-Meyer AR, Fugl-Meyer KS. On categorization and quantification of women’s sexual dysfunctions: an epidemiological approach. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:261–269. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901151

- Jamieson DJ, Steege JF. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00360-6

- McClish DK, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Health related quality of life in sickle cell patients: the PiSCES project. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:50. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-50

- Graves JK, Hodge C, Jacob E. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Nurs. 2016;42(3):113–119.

- Dampier C, LeBeau P, Rhee S, et al.;Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers (CSCC) Clinical Trial Consortium (CTC) Site Investigators. Health-related quality of life in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD): a report from the comprehensive sickle cell centers clinical trial consortium. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(2):203–205. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21905

- Barakat LP, Patterson CA, Daniel LC, et al. Quality of life among adolescents with sickle cell disease: mediation of pain by internalizing symptoms and parenting stress. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-60

- Graaff AA D, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GA, et al. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(10):2677–2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det284