ABSTRACT

Objectives: To determine the referral patterns and etiology of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) at an academic hematology center in northeast Mexico.

Methods: We included all consecutive outpatients older than 16 years, non-pregnant, with IDA diagnosed in the Hematology Service of the Dr. José E. González University Hospital between January 2012 and May 2017. Appropriate data were collected retrospectively from the electronic medical record. Data regarding first medical contact (primary care physician or hematologist) were compared.

Results: One hundred fifty-three patients were included in this study. The median age was 43 years (interquartile range, 35–51) and 85.6% were female; 128 (83.7%) patients were seen by a primary care physician before our evaluation. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) was the cause of IDA in 76 patients (49.6%), gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) in 31 (20.2%), H. pylori infection in 12 (7.8%), urinary tract bleeding in three (1.9%) and malabsorption-syndrome in two (1.3%). The etiology remained unknown in 29 (18.9%). The p value was <0.05 between groups according to the first medical contact, including frequency of at least one sign or symptom of IDA, previous use of iron supplementation and blood transfusion, comorbidities, complete blood count at diagnosis, and resolution rates of anemia.

Conclusion: The majority of our IDA patients were referred by another physician. Nearly half of the patients with IDA had AUB. IDA remains a diagnostic challenge for first contact physicians requiring a targeted educational intervention to improve IDA awareness and diagnostic skills.

Introduction

Anemia represents one of the most frequently diagnosed disorders in the world, affecting 25%–35% of the total population, and is becoming a public health problem in both developed and underdeveloped countries [Citation1–3]. Moreover, iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is one of the top five global leading causes of years lived with disability [Citation3]. Iron deficiency is a nutritional problem that particularly affects low-income countries due to low iron bioavility in diet, as it is based mainly on non-hem iron [Citation2]. Mexico is considered an underdeveloped country, with 70% of its population having at least one social deprivation, which is a criterion for defining poverty [Citation4]. Median age of its population is 27 years, with a life expectancy of 75, and a per capita income of $8,201 USD [Citation5]. The prevalence of anemia in this country is 11.6% in premenopausal women and 16.5% in the elderly [Citation6]. The most common cause is iron deficiency.

There are many etiologies of IDA in adult patients [Citation7]. In underdeveloped countries, inadequate intake of iron due to poverty and malnutrition predisposes to IDA, mainly in women, but it is not the sole cause. [Citation2] According to Mexican guidelines, the recommended intake of iron in diet in adult women and men is 16 and 18 mg per day, respectively. [Citation8] One study reported that Mexican adult women living in poverty were more likely to have anemia than adult women residing in food-secure households [Citation9]. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is another common cause of anemia with some studies reporting that up to 66% of women with menorrhagia have IDA [Citation10]. Chronic blood loss, especially in the gastrointestinal tract, is a frequent cause of IDA [Citation11] and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is also associated with IDA [Citation12].

Referral to a hematologist is not indicated in the majority of patients with IDA. Referral is appropriate for those in whom iron studies are inconclusive, the diagnosis is unclear, or intravenous iron is under consideration. Some studies have reported the etiology of IDA in specific populations, but to the best of our knowledge no previous reports addressing IDA etiologies in Mexican outpatient populations exist [Citation13–18]. The aim of this study was to determine the referral patterns and etiology of IDA at an academic hematology referral center in northeast Mexico.

Methods

Study population

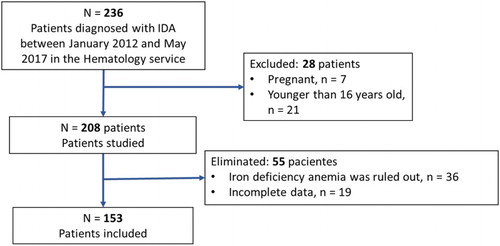

All consecutive outpatients diagnosed with IDA between January 2012 and May 2017 in the Hematology service of the Dr. José E. Gonzalez University Hospital in Monterrey, México were included. Patients younger than 16 years or pregnant were excluded, in order to obtain a homogeneous population. Patients for whom diagnosis of IDA was not confirmed in the electronic medical record were eliminated.

Anemia was defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [Citation19] as a hemoglobin (Hb) level of less than 12 g/dl in women and less than 13 g/dl in men. It was classified as mild if Hb was greater than 11 g/dl; moderate if 8–10.9 g/dl; and severe if < 8 g/dl. For the purpose of our study, IDA was defined as anemia with body iron depletion, measured by a serum ferritin < 15 µg/dl or a serum ferritin < 50 µg/dl and a transferrin saturation < 20% or as anemia with a positive response to a therapeutic test established as a 1 g/dl increase in hemoglobin after 30 days of adequate iron treatment.

Study design

This study was observational, descriptive and retrospective. Data extracted from the electronic medical record included: age; gender; body mass index; comorbidities; gynecological history (patients who had 62 days or more of menstrual flow/year were considered to have menorrhagia [Citation20]); use of concurrent medications (aspirin/ nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)), proton pump inhibitors, or anticoagulants); first medical contact at the diagnosis of anemia; the presence of at least one sign or symptom of anemia (fatigue, paleness, headache, dyspnoea, vertigo, palpitations, cramps, tinnitus, tachycardia, or angina pectoris); the presence of at least one sign or symptom of iron deficiency (pica, alopecia, paresthesia, neurocognitive dysfunction, brittle nails, atrophic glossitis, koilonychia, stomatitis or restless legs syndrome); previous iron supplementation; previous blood transfusions; anemia severity; Hb; mean corpuscular volume (MCV); mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH); serum ferritin; transferrin saturation; total iron binding capacity and serum iron at diagnosis; all previous and current diagnostic studies and evaluations made in order to reach the diagnosis of IDA; number of follow-up consultations; treatment used; resolution rates of the anemia in the last consultation; socioeconomic level classified into six different categories (A/B: highest level, C+: high middle level, C: middle level, C−: emerging middle level, D+: low level, D: extreme low level), as calculated by the Mexican association of market intelligence and opinion agencies [Citation21]; and the dietary iron intake, classified as sufficient (more than 15–20 mg per day) or insufficient (less than 15–20 mg per day), calculated by a nutrition specialist according to the nutrient recommendations for the Mexican population [Citation22].

Etiology was defined as the finding of any underlying diagnosis that the treating physician considered to be the cause of IDA. An unknown etiology was established in patients with normal results in the evaluation performed or with an incomplete evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR), mean and standard deviation or, when appropriate, absolute counts and percentages. Differential characteristics of groups of patients with different first medical contact of IDA were evaluated by appropriate statistical tests (χ2 test, for categorical variables; Student’s t-test, for parametric variables; and Mann–Whitney U test, for non-parametric variables) using SPSS statistical software version 22. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Case studies

One hundred fifty-three patients were eligible for this study (). The clinical and demographic characteristics of the studied population are presented in . Median age was 43 years (IQR, 35–51 years), 28 patients were older than 60 years (18.3%). One hundred thirty-one patients (85.6%) were women. Dietary assessment was obtained from 28 patients, all of whom had sufficient iron intake. The incidence of IDA was 29 ± 9.2 new cases diagnosed per year. The diagnosis of IDA was confirmed by iron-status analysis in 120 patients (78.4%) and in the rest was confirmed by a positive therapeutic test. The frequency of at least one sign or symptom of IDA in the study population is summarized in .

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients at diagnosis of IDA.

Table 2. Frequency of signs and symptoms of IDA.

The median follow-up was three consults (IQR, 2–5 consults) per patient. All patients were on iron replacement therapy after the diagnosis, 124 patients (81%) were given oral, 15 (9.8%) both oral and parenteral, and eight (5.2%) parenteral preparations. Six patients (3.9%) needed blood transfusion before oral repletion, due to their critical clinical situation. Ninety-nine patients (71.2%) had an adequate response (a 1 g/dl increase in hemoglobin after the first month of iron replacement therapy) and 74 patients (53.2%) had complete remission of anemia (Hb > 12 g/dl in women and > 13 g/dl in men) at their last registered visit. Treatment for the specific etiology of IDA was given in 76 patients (49.7%).

Causes of IDA

All patients underwent a diagnostic workup for IDA according to the criteria of their attending hematologist. Not all patients completed the diagnostic workup (). Causes of IDA are shown in . The main reported etiology was AUB in 76 patients (49.6%), followed by gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) in 31 patients (20.2%). Other etiologies (H. pylori infection, urinary tract bleeding, and malabsorption syndrome) were responsible in 17 patients (11.1%). The remaining 29 patients (18.9%) were classified as having an unknown etiology.

Figure 2. Patients who completed diagnostic work-up. Gast: gastroenterological; Gyn: gynecological; US: ultrasonography; U/L: upper and lower; FOBT: fecal occult blood test.

Table 3. Iron deficiency anemia etiology.

First medical contact

Patients were divided into two groups according to the first medical contact they had to treat their anemia, either a primary care physician or a hematologist. A significant statistical difference was found between both groups for the following variables: hemoglobin, MCV and MCH at diagnosis, the method of confirming IDA diagnosis, comorbidities, the presence of at least one sign or symptom of IDA, previous iron supplementation, previous blood transfusion, and resolution rate of the anemia in the last registered visit ().

Table 4. Difference between first medical contact in the diagnosis of IDA.

Discussion

Evaluation of IDA etiology, according to Mexican guidelines [Citation8], should be performed by primary care physicians with prompt referral to hematology or internal medicine specialists for patients in whom IDA remains unclear or unresolved. This is consistent with the finding that 83.7% of our study population had already been seen by another physician before our evaluation. These patients were more likely to have clinical manifestations of IDA and had a slightly lower hemoglobin level (8.8 vs 9.6 g/dl, p = 0.033), despite previous iron supplementation or blood transfusion in the majority, compared to those whose first medical contact was a hematologist. This may reflect the lack of experience of general practitioners in our country to properly treat IDA, and the loss to follow-up and lack of re-evaluation in these patients. In the group for which the hematologist was the first medical contact, the diagnosis of IDA was more frequent based on red blood cell indices (red blood cell distribution width or mean corpuscular volume) posterior to iron administration.

Mexican guidelines [Citation8] recommend evaluating socioeconomic factors and eating habits in all patients with IDA. However, we found that this was inconsistently evaluated. Although 64% of patients evaluated had a low socioeconomic level, none had insufficient iron intake, contrasting with previous studies reporting that suboptimal iron intake was common in patients with IDA. However, this was seldom the sole cause of anemia [Citation9,Citation13,Citation23]. Our population had a similar frequency of signs and symptoms of IDA compared with other studies [Citation7,Citation24].

We found that AUB was the leading cause of IDA in our population, compared to other reports in which the main cause was GIB [Citation13–15]. This could be explained by the higher proportion of women included compared to other studies: 85% vs 61%–66% [Citation13–15]; and younger median age: 43 years vs 59–70 years [Citation13–15]. GIB was the second most common cause of IDA in our study. Less common causes were H. pylori infection, urinary tract bleeding, and malabsorption syndrome.

IDA is still a diagnostic challenge that needs a multidisciplinary approach. In previous studies, the percentage of patients with IDA with an undefined etiology ranged from 9% to 46% [Citation13–17], while in our study, the etiology remained unknown in 19% of cases. The latter can be explained by the fact that most of our patients did not undergo a complete diagnostic workup despite medical advice, mainly attributed to the low cultural and economic level of our population. Incomplete workup was also reported in an Italian study in which 15% of patients refused a colonoscopy as part of their IDA evaluation [Citation18]. Sociodemographic factors may in part explain our results: the country in which this study was performed is considered a middle-income country with a young population and with a lower life expectancy than developed countries [Citation25].

Our study has some limitations: the data was retrospective and there was no homogeneity in the diagnostic approach used by the hematology physician, including the IDA diagnosis per se made by iron-status analysis or therapeutic test. This is mainly attributed to the limited economic sources of our population, as previously mentioned. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study carried out in a Mexican outpatient population addressing the etiology of IDA. Our results may help to develop future public health programs and enhance the targeted teaching in primary care as the majority of patients referred to our hematology center could have been evaluated by a primary care physician and then sent for gastroenterologic or gynecologic evaluation. These actions could have reduced costs and time, and improved the yield of IDA diagnostic approach.

In conclusion, IDA is a frequent disease seen in our reference center. The majority of our patients had been seen by another physician before our evaluation. Nearly half of our patients with IDA had AUB, although the most common cause in men was GIB. IDA remains a diagnostic challenge for first contact physicians requiring a targeted educational intervention to improve IDA awareness and diagnostic skills.

Ethics approval

Despite being an observational study, the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethics Committee of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León Medical School, Registration no.: HE16-00009).

Acknowledgment

We thank Anel Melissa de la Torre-Salinas, specialist nutrition, for her evaluation of the patients and Sergio Lozano-Rodríguez, M.D. for his critical review of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

José Carlos Jaime-Pérez http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6804-9095

David Gómez-Almaguer http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0460-6427

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* All authors work at the Hospital Universitario ‘Dr. José Eleuterio Gonzalez’ in the Hematology service and most belong to the National System of Researchers in Mexico. This hospital-school is a public Hospital that belongs to the Medical School of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

References

- Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123:615–624. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325

- Osungbade KO, Oladunjoye AO. Anaemia in developing countries: burden and prospects of prevention and control. In: Silverberg D, editor. Rijeka: InTech Europe; 2012. ISBN: 978-953-51-0138-3.

- Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2

- Coneval [Internet]. Ciudad de México, México; [Cited 2017 Sept 12]. Available from: http://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/Paginas/PobrezaInicio.aspx.

- INEGI [Internet]. Aguascalientes, México. 2017 [Cited 2017 Sept 12]. Available from: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/temas/default.aspx?s=est&c=17484.

- Gutiérrez JP, Rivera-Dommarco J, Shamah-Levy T, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2012. Resultados Nacionales. Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2012.

- Longo DL, Camaschella C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1832–1843. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1502888

- Prevención, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la anemia por deficiencia de hierro en niños y en adultos. Guía de práctica clínica. [Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency anemia in children and adults. Clinical practice guidelines]. Mexico city: Secretaria de salud; 2010.

- Fischer NC, Shamah-Levy T, Mundo-Rosas V, et al. Household food insecurity is associated with anemia in adult Mexican women of reproductive age. J Nutr. 2014;144(12):2066–2072. doi: https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.197095

- Karlsson TS, Marions LB, Edlund MG. Heavy menstrual bleeding significantly affects quality of life. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:52–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12292

- Cilona A, Zullo A, Hassan C, et al. Is faecal-immunochemical test useful in patients with iron deficiency anaemia and without overt bleeding? Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:1022–1024. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2011.08.002

- Annibale B, Capurso G, Martino G, et al. Iron deficiency anaemia and helicobacter pylori infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;16:515–519. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00288-0

- McIntyre AS, Long RG. Prospective survey of investigations in outpatients referred with iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 1993;34:1102–1107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.34.8.1102

- Willoughby J, Laitner S. Audit of the investigation of iron deficiency anaemia in a district general hospital, with sample guidelines for future practice. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:218–222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.76.894.218

- Luman W, Ng KL. Audit of investigations in patients with iron deficiency anaemia. Singapore Med J. 2003;44(10):504–510.

- Logan E, Yates J, Stewart R, et al. Investigation and management of iron deficiency anaemia in general practice: a cluster randomised trial of a simple management prompt. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:533–537. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.78.923.533

- Hershko C, Vitells A, Braverman DZ. Causes of iron deficiency anemia in an adult inpatient population. Effect of diagnostic workup on etiologic distribution. Blut. 1984;49(4):347–352. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00320209

- Vannella L, Aloe Spiriti MA, Cozza G, et al. Benefit of concomitant gastrointestinal and gynaecological evaluation in premenopausal women with iron deficiency anaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:422–430. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03741.x

- World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

- Novak ER. Clinical features of menstruation. In: Nocak ER, Seegar JG, Jones HW, editor. Gynecology 8th edition. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1971. p. 41–42.

- López-Romo H. Nivel socioeconómico AMAI [Socioeconomic level AMAI]. Mexico city: Asociación Mexicana de Agencias de Investigación de Mercado y Opinión Pública; 2008.

- Ramos-Peña EG, Ramos-Cavazos MT, González-Rodríguez LG, et al. Cambios en la calidad de la dieta en familias de un estado del noreste de México; analisis comparativo de la ingesta de nutrimentos [Changes in the quality of the diet in families of Mexico; analysis of nutrition intake]. Rev Salud Publica Nutr. 2011;12(4):8–16. Spanish.

- Contreras-Manzano A, De la Cruz V, Villalpando S, et al. Anemia and iron deficiency in Mexican elderly population. Results from the Ensanut 2012. Salud Publica Mex. 2015;57:394–402. doi: https://doi.org/10.21149/spm.v57i5.7619

- Lopez A, Cacoub P, Macdougall IC, et al. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):907–916. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60865-0

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Selangor, Malaysia; 2016 [Cited 2017 Sept 12] Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/health-inequalities-persist/es/.