ABSTRACT

Objectives: Although many studies have assessed numerous molecular and immunohistochemical prognostic markers for diffuse large Bcell lymphoma (DLBCL), there is always a need for simple widely available markers. This study was planned to illustrate the clinical significance of baseline plasma fibrinogen levels in DLBCL patients.

Methods: We prospectively investigated 76 DLBCL patients treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and hostacortine between August 2015 and February 2018. Baseline plasma fibrinogen level was measured and correlated with patients’ clinical features, laboratory parameters, response to therapy, progression-free survival and overall survival.

Results: Significant association between fibrinogen level and clinical features such as the presence of B symptoms (P < .001) and clinical stage (P < .001) was observed while no association with age, gender, number of involved extranodal sites, performance status and international prognostic index (IPI) was found. Baseline fibrinogen level was significantly related to laboratory parameters including red cell distribution width (RDW) (P < .001), platelet count (P = .02), serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (P = .009) and B2-microglobulin (P = .008). No statistically significant correlations were detected between baseline fibrinogen levels; and response to therapy, progression-free survival and overall survival.

Conclusion: Baseline plasma fibrinogen level did not show prognostic significance for DLBCL patients, although it was associated with patients’ clinical features and laboratory parameters. Being simple, cheap and widely available laboratory test, its use should be encouraged routinely in clinical practice to precisely clarify its predictive merit.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an intermediate-grade lymphoma that represents the most prevalent histological subtype among adult patients with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). It is considered potentially treatable but its aggressive behaviour is a common feature. Despite the advances in the treatment of patients with DLBCL and the addition of rituximab to therapy, relapse or resistant to treatment is anticipated to occur in approximately 30% of the patients [Citation1].

Although the International Prognostic Index (IPI) is considered the current standard prognostic system for lymphoma, it has been suggested that IPI may not perfectly predict the clinical course of lymphoma due to heterogeneous prognosis exists among patients within the same IPI risk group [Citation2–4].

Many promising prognostic molecular and immunohistochemical markers have been utilized to characterize high-risk patients with lymphoma [Citation5,Citation6]. However, most of these markers are expensive, difficult to interpret and in some instances require further confirmation. Therefore, there is a continuous need for identification of cheap, widely available and readily interpretable prognostic markers [Citation7].

Fibrinogen is one of the most substantial acute phase reactants. It has a critical role in the maintenance of hemostasis, inflammatory responses and neoplastic progression. The presence of hyperfibrinogenemia in various types of cancers and its association with cancer progression and metastasis has been reported in some studies [Citation8–10].

As the prognostic role of fibrinogen in patients with DLBCL is not well identified, we designed this study to explore the possible correlations of hyperfibrinogenemia with clinical features, laboratory data and survival outcome of DLBCL patients.

Patients and methods

This prospective study was carried out on 76 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who attended the new cases clinic of Clinical Oncology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University. Patients were diagnosed, received chemotherapy and followed up between August 2015 and February 2018.

The inclusion of patients based on: newly diagnosed histologically proved DLBCL without prior chemotherapy and availability of full clinical information and follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria were transformed indolent lymphoma, patients on anticoagulant therapy, previous history of malignancy and previous radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

After approval of our local ethical committee and patients consent; patients were subjected to full history taking (including age, gender, complaint, co-morbidities, family and personal history of cancer and surgical interference), thorough clinical examination (including weight, height for body mass index assessment, performance status, local and general examination). Performance status (PS) was assessed, international prognostic index (IPI) was calculated and disease stage was evaluated in accordance with the Ann Arbor system. For all patients, the planned treatment regimen was to receive rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and hostacortine (R-CHOP). For patients with refractory disease or relapsed tumours second-line salvage chemotherapy was administrated.

Patients follow-up was maintained for at least 24 months from time of diagnosis. Patients were assessed every cycle by clinical examination and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) estimation. Computed tomography (CT) was requested every two cycles.

Complete remission (CR) was defined as disappearance of all lesions for 4 weeks. At least 50% reduction of lymph node masses was defined as partial remission (PR) while new lesions or increased size of lymph nodes were categorized as progressive disease (PD). Patients who experienced no CR, PR or PD lesions were classified as stable disease.

Based on clinical assessment, laboratory tests and imaging; patients were categorized into responders ‘those with regressive disease’ and non-responders ‘those with stable or progressive disease.’

Progressionfree survival (PFS) was calculated for all patients as the length of time from the date of start of treatment until the disease started to progress in the form of relapse, newly developed nodal/extranodal sites, or increased in size and/or number of previously involved lymph nodes. Overall survival (OS) was determined as the time from the start of chemotherapy till the date of last follow-up visit or patient death.

Laboratory investigations

Venous blood samples were collected from each patient before the initiation of any therapy. Work up for patients included the following: complete blood count (CBC) using Sysmex XN-10 Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan), C-reactive protein (CRP) using CRP analyzer (HEALES, Shenzhen, China); lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) by AU680 Chemistry Analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc; Brea, California, U.S.A.); and beta2-microglobulin using mini VIDAS analyzer (Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Plasma fibrinogen levels were measured using the Clauss method by STA compact coagulometer (Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions, the reference range of plasma fibrinogen level was determined as being between 200 and 400 mg/dl and a concentration greater than 400 mg/dl was defined as hyperfibrinogenemia.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 23 (IBM SPSS statistics, version 23.0, Armnok, NY: IBM Corp.). Chi-square test (χ2) was used to study the association between categorical variables. Mann–Whitney's test was employed to compare quantitative variables of not normally distributed data. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were determined using Kaplan–Meier statistics with log-rank test to express the significance. A probability value of less than 0.05 was reported as statistically significant.

Results

The current study included 76 patients with DLBCL, 40 females and 36 males, most of the patients were less than 60 years old. There were 43(56.6%) patients with plasma fibrinogen levels below 400 mg/dl, and 33 (43.4%) patients with plasma fibrinogen levels above 400 mg/dl. During the follow-up period, 20 patients experienced progressive or stable disease or were relapsed and they considered as non-responders while 56 patients experienced partial and complete remission and those were considered as responders ().

Table 1. The Clinical features of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma in relation to baseline fibrinogen level.

The relation between baseline fibrinogen levels and clinical data was assessed. No association was found with age, gender, number of involved extranodal sites, performance status, IPI and response to treatment (all Ps > .05) while the significant association was observed with B symptoms (P < .001) and clinical stage (P < .001) ().

The mean baseline fibrinogen level among the included patients was 408.43 ± 158.29 mg/dl and the mean baseline fibrinogen level among hyperfibrinogenemia group was 563.03 ± 104.23 mg/dl. The relation between baseline fibrinogen levels and laboratory parameters was also tested. Baseline fibrinogen level was significantly related to red cell distribution width (RDW) (P < .001), platelet count (P = .02), serum LDH (P = .009) and B2-microglobulin (P = .008) ().

Table 2. The Laboratory data of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma in relation to baseline fibrinogen level.

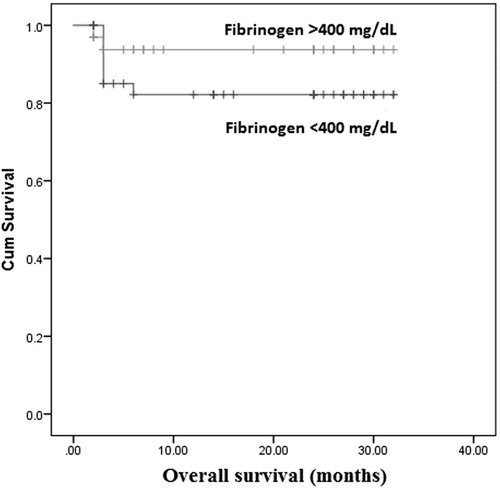

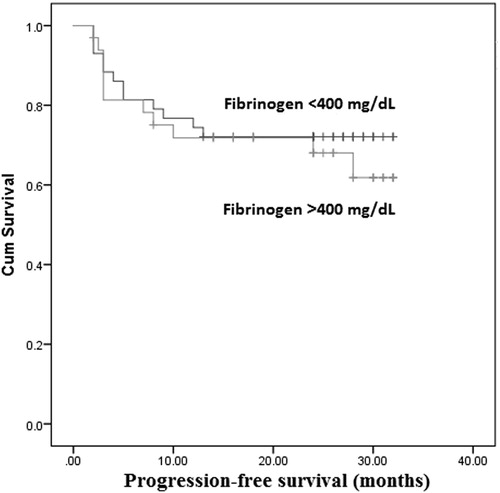

The Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to determine whether fibrinogen level was associated with OS and PFS. The overall DLBCL patients survival was not significantly different in hyperfibrinogenemia group [95% confidence interval (CI): 21.91–29.99] compared with fibrinogen <400 mg/dl group (95% CI: 22.06–29.13) (P = .77; ). Similarly, PFS showed no significant difference between hyperfibrinogenemia group (95% CI: 19.49–27.98) and fibrinogen <400 mg/dl group (95% CI: 21.07–28.23) (P = .58; ).

Discussion

Fibrinogen is a plasma glycoprotein which is mainly produced by liver cells, and also by epithelial and tumour cells [Citation11]. It is physiologically concerned with platelet aggregation, coagulation and wound healing [Citation12]. Fibrinogen is one of the positive acute phase proteins, which are characterized by elevated concentrations during inflammation [Citation13].

The link between tumorgenesis and inflammatory process is evident [Citation14]. The inflammatory microenvironment of tumour cells constitutes an essential part of the neoplastic process by maintaining high proliferative rate, sustained survival signals and migration of tumour cells [Citation15]. Fibrinogen induces production of proinflammatory cytokines by binding to inflammatory or neoplastic cells [Citation16]. Furthermore, fibrinogen enhances neoplastic cells proliferation, invasion and metastasis by inducing sustained adhesion of neoplastic cells and promoting tumour new vessels formation by fibroblast growth factor-beta [Citation17].

In this study, we demonstrated the association between hyperfibrinogenemia and different clinical and laboratory characteristics of DLBCL patients. Also, we investigated the possible prognostic importance of hyperfibrinogenemia in those patients.

Our results showed lack of association between baseline fibrinogen level and clinical data such as age, gender, number of involved extranodal sites, performance status and IPI while hyperfibrinogenemia was associated with the presence of B symptoms and advanced clinical stage. As regard laboratory parameters, baseline fibrinogen level was significantly related to RDW, platelet count, serum LDH and B2-microglobulin.

In addition, we demonstrated that hyperfibrinogenemia was not significantly associated with progression-free survival and overall survival by Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Similar to our results, Jiang et al. [Citation18] demonstrated lack of association between fibrinogen level in lymphoma patients and age while hyperfibrinogenemia was correlated with B symptoms, advanced clinical stage and increased serum LDH concentration.

The association between B symptoms and hyperfibrinogenemia might be explained by the systemic inflammatory response of malignant lymphoma. Presence of B symptoms in lymphoma patients was previously linked with both poor prognosis and increased serum concentrations of other inflammatory proteins such as CRP [Citation19].

Serum LDH was demonstrated by Ji et al. [Citation20] as a perfect surrogate marker of tumour burden in DLBCL patients. Therefore, the positive correlation between baseline fibrinogen and LDH levels in our study might suggest a possible connection between fibrinogen level and tumour burden.

Inconsistent with our results; Wang et al. [Citation21] reported a significant association between hyperfibrinogenemia and the number of involved extranodal sites in Non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Also, they found a tendency toward reduced 2-year progression-free survival in DLBCL patients with baseline hyperfibrinogenemia.

Similar to our results; Troppan et al. [Citation22] showed no correlation between baseline fibrinogen level in DLBCL patients and clinical characteristics including age, gender and IPI. However, our results regarding the relation between hyperfibrinogenemia and patients overall survival were against that of Troppan et al. [Citation22] who reported a significant association between increased fibrinogen concentration and worse 5-year OS.

Variation between the results of different studies may be explained by the various design and sample size of each study; and the different racial groups.

In the current study, some limitations should be observed; the relatively small sample size and short duration of patients follow-up.

In spite of inconsistent results between different studies; our study reported important associations between fibrinogen levels and various clinical and laboratory parameters. The inclusion of baseline plasma fibrinogen as routine laboratory test and its integration in the prognostic scores for DLBCL patients may prove its utility as valuable predictive biomarker.

Conclusion

Elevated plasma fibrinogen was significantly related to disease stage, positive B symptoms, serum LDH and B2-microglobulin levels at presentation suggesting the possible prognostic utility of baseline fibrinogen concentration. But, further studies with larger sample size and longer follow-up period are recommended to precisely clarify the prognostic merit of fibrinogen in DLBCL patients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Amira Mohamed Foad Shehata http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3164-0265

References

- Li YL, Gu KS, Pan YY, et al. Peripheral blood lymphocyte/monocyte ratio at the time of first relapse predicts outcome for patients with relapsed or primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-341

- Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109:1857–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257

- Czuczman MS, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Alkuzweny B, et al. Prognostic factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients treated with chemotherapy may not predict outcome in patients treated with rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1830–1840. doi: 10.1080/10428190600709523

- Sweetenham JW. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: risk stratification and management of relapsed disease. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005;2005:252–259.

- Hasni MS, Berglund M, Yakimchuk K, et al. Estrogen receptor β1 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma growth and as a prognostic biomarker. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:418–427. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1193853

- Duncan VE, Ping Z, Varambally S, et al. Loss of RUNX3 expression is an independent adverse prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:179–184. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1180686

- Xin X, Liu Z, Meng F, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors in lymphoma patients with bone marrow involvement: a single center cohort study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:9676–9683.

- Mei Y, Zhao S, Lu X, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of preoperative plasma fibrinogen levels in patients with operable breast cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146233

- Zhang D, Zhou X, Bao W, et al. Plasma fibrinogen levels are correlated with postoperative distant metastasis and prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:38410–38420.

- Zhu LR, Li J, Chen P, et al. Clinical significance of plasma fibrinogen and D-dimer in predicting the chemotherapy efficacy and prognosis for small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18:178–188. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1350-7

- Lawrence SO, Simpson-Haidaris PJ. Regulated de novo biosynthesis of fibrinogen in extrahepatic epithelial cells in response to inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:234–243.

- Polterauer S, Grimm C, Seebacher V, et al. Plasma fibrinogen levels and prognosis in patients with ovarian cancer: a multicenter study. Oncologist. 2009;14:979–985. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0079

- Xu Q, Yan Y, Gu S, et al. A novel inflammation-based prognostic score: The fibrinogen/albumin ratio predicts prognoses of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:4925498.

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322

- Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, et al. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:1–19. doi: 10.1155/2014/149185

- Jensen T, Kierulf P, Sandset PM, et al. Fibrinogen and fibrin induce synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines from isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:822–829. doi: 10.1160/TH07-01-0039

- Bekos C, Grimm C, Brodowicz T, et al. Prognostic role of plasma fibrinogen in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma – a multicenter study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:681, Article ID: 14474. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13934-8

- Jiang YJ, Li XM, Han XH, et al. Relationship between coagulation function and international prognostic index in lymphoma patients. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2010;18:1489–11493.

- Sharma R, Cunningham D, Smith P, et al. Inflammatory (B) symptoms are independent predictors of myelosuppression from chemotherapy in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) patients – analysis of data from a British National Lymphoma Investigation phase III trial comparing CHOP to PMitCEBO. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-153

- Ji H, Niu X, Yin L, et al. Ratio of immune response to tumor burden predicts survival via regulating functions of lymphocytes and monocytes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;45:951–961. doi: 10.1159/000487288

- Wang JW, Li KC, Shi Z. Tang X: clinical significance of plasma fibrinogen level in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Tumor. 2014;34:370–373.

- Troppan KT, Melchardt T, Wenzl K, et al. The clinical significance of fibrinogen plasma levels in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:326–330. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203356