ABSTRACT

Using Social Movement Theory (SMT) as a methodological framework and explicitly employing the core SMT concepts of political opportunism and framing, this paper seeks to examine Boko Haram's use of discourse in activism. As a rarely employed research method within the Boko Haram literature, SMT holds explanatory power around the movement's approach to transforming motivation potential into actual mobilisation via frame resonance. Focusing on the application of framing within (interpreted) sermons, lectures and exhortations by both Muhammad Yusuf and Abubakar Shekau as former substantive leaders of Boko Haram, this paper unpacks the discourse of Boko Haram's ideology. The paper shows that this ideology, which contrasts the softened core of the Salafist/Wahhabi doctrines from which Boko Haram broke away, relies on problematic interpretations of Qur’ānic exegesis and political thought as both relate to faith and governance in northern Nigeria. One policy recommendation to emerge from this study is that counter-narratives to Boko Haram's ideology should highlight not just why but also how the group's rhetoric employs lies and half-truths in an attempt to rationalise its activism; despite what appears to be an adherence to Qur’ānic exegesis, in making its claims.

Introduction: Social movement theory (SMT) and Islamic activism

Islamic activism, ‘the mobilisation of contention to support Muslim causes’,Footnote1 is a form of contention that has gained peculiar currency within the academic discourse over the past two decades, simultaneously evolving and spreading across the globe.Footnote2 This broad concept accommodates a spectrum of contentious repertoires frequently employed under the banner of Islam. The contentious repertoires include activism by terrorist groups but also accommodate for ‘collective action rooted in Islamic symbols and identities, explicitly political movements that seek to establish an Islamic state and inward-looking groups that promote Islamic spirituality through collective efforts’.Footnote3

Each of these groups claims to be ‘Islamic’ but also differ from other similar claimants within the Muslim world in many ways. Consequentially, it would be problematic to narrowly assume that certain groups are non-Islamic, whereas others are, for the convenience of analysis or labelling. Timothy Peace, for instance, considers ‘Muslims’ to mean those who self-identify as that, regardless of whether they practice or whether their actions are inconsistent with what might be considered Islamic tenets. ‘Muslim’, along these lines, is, therefore, ‘a sociological category for identification rather than a strict faith category’.Footnote4 Thus Islamic activism relates to the mobilisation and actions of those who self-identify as Muslim and assert their Islamic identity within these actions, drawing on it to make political commitments.Footnote5 This is regardless of what those commitments are precisely and where they lie on the spectrum of contentious politics.

Additionally, the study of Islamic activism does not exist in a theoretical or practical vacuum but instead is part of a broad knowledge base of contentious politics at large.Footnote6 Typical tactics of activism and dissent, including petitions, public protests, and even the use of violence, as an example, have a storeyed career. Indeed, the timing, choice and targets around the tactics employed tend to be context-specific. Nevertheless, the commonalities of the repertoires of contention are such that they ‘exhibit consistency across time and space’.Footnote7 Indeed, as Sidney TarrowFootnote8 reminds us, such tactics are so common, they can be interpreted as a reflection of modular protest forms, which can be employed: by different actors, at different times, in different places.

That Islamic activism is not unique is also revealed in the fact that other collective actors also respond to repression, are impacted by structural strain, link political opportunism to discourse, mobilise resources, and employ frames ‘rooted in symbols, discourse, and practice, often designed to evoke a sense of injustice to encourage activism’.Footnote9 This indicates that the organisation of Islamic activism, including its dynamics and processes, can be viewed as ‘elements of contention that transcend the specificity of ‘Islam’ as a system of meaning, identity, and basis of collective action’.Footnote10

Certainly, the ideational components of Islam and its ideological worldview differentiate Islamic activism from other forms of contention.Footnote11 Nevertheless, so far as collective action within Islamic activism is concerned, the concomitant mechanisms are broadly consistent across movement types. In other words, as Quintan Wiktorowicz concludes, ‘Islamic activism is not sui generis’.Footnote12

This conclusion and the supporting arguments within this introduction suggests that SMT holds such potential explanatory power for Islamic activism, regardless of the tactics employed by movement actors. Accordingly, such groups should not be situated in a separate box and given ‘special explanations’. Nevertheless, despite the similarities between Islamic activism in all its forms, and other types of collective action, it has for the most part ‘remained isolated from the plethora of theoretical and conceptual developments that have emerged from research on social movements and contentious politics’.Footnote13 The same critical approaches, such as SMT, employed in the study of activism, have not been employed to the same degree within the debate on Islamic activism.

With this relative neglect of SMT as a framework of interrogation for Islamic activism, the potential for further studies manifests, and it is here that this article seeks to advance the debate as it relates to Boko Haram. This article will show that it is possible — perhaps even necessary — in conducting a sociological enquiry of Islamic activism to treat it no more or less like a social movement such that ‘the standard social movement questionnaire to ask telling questions about Islamic activism’ can be adopted.Footnote14

The rationale for this non-preferential or discriminatory treatment of Islamic activism is that, like other social movement organisations (SMOs), radical Islamic groups employ frames, mobilise resources, respond to repression, and exploit political opportunism. Moreover, just like other SMO actors, Islamic activists also engage the process of ‘boundary activation’, whereby one of several previously existing divisions among social locations is made so salient that any other divisions are suppressed, and most political interaction is organised around (and across) that division alone.Footnote15 Thus, insofar as SMT can help explain the sociology of political activism, it can also play a similar role within the context of Islamic activism.

This approach to analyzing Islamic activism using SMT has merits both in what it prevents and facilitates. More specifically, treating Islamic activism as part of the sphere of contentious politics makes it ‘easier to avoid the reduction of Islamic activism to a straightforward product of distinctive Islamic mentalities or of a peculiar social milieu’.Footnote16 Indeed, viewed this way, Islamic activism no longer needs to be presented as a solo performance of sorts, wherein a particular doctrine or biographical entry pertinent to one actor or group is said to be the main reason for their behaviour. Furthermore, interrogating radical Islamic movements from this lens may well attenuate the so-called research taboo long associated with the study of terror movements.Footnote17 That is, if SMT research applies just as much to Islamic activism, why should SMT researchers be stigmatised for interacting with terror movements that identify with the Muslim identity?

An added benefit of treating Islamist activism as no more or less than any other form of political activism is that this makes it ‘easier to grasp interactions between groups of activists (as well as between activists and governments) that shape and reshape the locus, intensity, and form of Islamic activism’ by a social movement organisation (SMO).Footnote18 An SMO is ‘a complex or formal organisation which identifies its goals with the preferences of a social movement or countermovement and attempts to implement those goals’.Footnote19 And SMT applies to activism by all SMOs, including radical Islamic movements.

SMT as an underused theoretical framework within the Boko Haram debate

This article analyses how Boko Haram, as an SMO, selectively employs ideological resources (from within their political environment and religious texts) to frame discourse towards energising and mobilising receptive audiences. The article's focus use of SMT in analyzing Boko Haram's is a significant differentiator, as existing multidisciplinary research on Boko Haram is not unified by a shared research agenda. Instead, scholarly analysis of Boko Haram tends to be scattered across various disciplines.

Moreover, the research questions, theoretical frameworks and methodologies tend to be narrow because they are often pre-determined by a particular disciplinary drive. This is not unlike the existing state of affairs surrounding research on Islamic activism as a broader field.Footnote20

Political scientists, for example, have primarily been concerned with how Boko Haram's interpretation of Islam impacts the state and politics.Footnote21 Sociological analyses of Boko Haram's constitution have mostly been interested in exploring the demographic roots of Islamist recruits and the viability of the government's rehabilitation programme.Footnote22 Islamic theologians and jurists, along with religious studies scholars, meanwhile, have predominantly focused on the ideas that motivate Boko Haram's approach to contentious politics—whether, for instance, Boko Haram's ideology is shaped by local or international influences is already an area of divided scholarly debate.Footnote23

Historians, on their part, tend to investigate and narrate the histories of Boko Haram.Footnote24 Military scholars focus more on the threat posed by the group, its evolution, along with how the Nigerian state has responded.Footnote25 Human Rights reports tend to emphasise the plight of the victims and the problematic practices of both Boko Haram and Nigeria's forces in response.Footnote26 The gendered view of the insurgency, meanwhile, examines the role of women and the nature of gender-based violence (GBV) within Boko Haram's calculus of warFootnote27 but also points to the ‘gender-bending role of women as frontline fighters, knowledge brokers, state informants, and producers of vigilante technologies’.Footnote28

The result of such disciplinary fragmentation is that understanding within each sub-field around Boko Haram has evolved into a robust literature body within a relatively short time. However, so far as all these elements fit together, potentially interact, and certainly influence the nature of Boko Haram's contentious repertoire, only a few models or frameworks have been developed, and these have broadly emerged in the last few years – see, as examples, Subrahmanian et al.,Footnote29 Iyekekpolo,Footnote30 and Amaechi and Tshifhumulo.Footnote31 In this sense, as proposed by this study, SMT acts as a unifying framework and agenda by which an effective mode of inquiry can help expand existing boundaries of research on Boko Haram. Boko Haram's history, idea system, activism, response to repression, view of the political environment and the state, ability to recruit, and problematic Qur’ānic exegesis will all be unified within this study.

Drawing from social movement theory (SMT) and focusing specifically on the problematic interpretations of Qur’ānic exegesis and political thoughts in the lectures of two dead leaders of a northern Nigerian-based Boko Haram (Yusuf and Shekau), the paper seeks to explain how interpreted sermons of both leaders contrasted the softened core of the salafist/Wahhabi doctrines from which the group broke away.

Boko Haram's discourse is examined in the form of interpreted speeches, writings, and sermons between 2006 and 2016. The source of this discourse is a compendium within The Boko Haram Reader by Abdulbasit Kassim and Michael Nwankpa.Footnote32 As the analyzed discourse relates to faith and governance in Islam in general and the political tensions within the ‘crowded religious marketplace’ of northern Nigeria at the time,Footnote33 it came to resonate with a larger audience.

One of the key themes examined within this article is how the resonance of a social movement's discourse increases motivation and mobilisation for activism. Such mobilisation is critical: grievances and dissatisfaction in existing networks do not automatically translate to mobilisation. On the contrary, grievances not effectively situated within existing discourse may not lead to any substantive action at the group level. Thus, as this paper seeks to show, such grievances need to be framed to align with the changing religious and socio-political realities in which potential recruits and activists identify.

In other words, the ability of an SMO to transform motivation potential into an actual mobilisation is contingent on the extent of frame resonance. Along these lines, a question that SMO leaders must tackle to translate grievance into activism is how the framing of such grievances resonates with the cultural symbols, languages and historical narratives with which both SMO members and potential recruits identify. Indeed, it is within such framing that potential activists see engagement as compelling and, in some instances, inevitable. The start point of framing is the movement's environment,Footnote34 and it is indeed here that many of Boko Haram's influences can be found.

Debating Boko Haram as a product of its environment

In the debate of Boko Haram as a global or local actor,Footnote35 the movement has been argued by one school of scholars to be a product of its immediate religious, political and social environment: a local phenomenon, not a global one.Footnote36 This is consistent with the view by GunningFootnote37 that social movements do not function exogenously to localised considerations of the broader social, economic and political environment. Therefore, along this train of thought, emergent movements are shaped by the same environment from where they come to hold relevance.

In the instance of Boko Haram, Adam Higazi, Brandon Kendhammer, Kyari Mohammed, Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, and Alex Thurston believe that local references to jihad underpin Boko Haram's push for jihad.Footnote38 This camp of scholars argues that international influences on Boko Haram's emergence should not be overembellished and that radical shifts within Nigeria's Salafist movement, evidenced since the 1970s, are the origins for the jihad being waged today by the likes of Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS) and Islamic State West Africa (IS-WA).Footnote39

Moreover, employing Social Movement Theory (SMT), Amaechi interrogates the exploitation of political Islam as a mobilising resource for Boko Haram, arguing that the movement's isolation from the Islamic establishment, including formal political and religious institutions, lowered ‘the opportunity for legitimate means’ and ultimately influenced the movement's pivot towards violence.Footnote40 Building on revolutionary theories developed by Jeff Goodwin,Footnote41 Amaechi contends that countries, such as Nigeria, which exhibit ‘exclusive’ and ‘elite’ government institutions, tend to experience more violent movements than those where such institutions are more open.Footnote42

State internal repression also features within this discourse. Della Porta's research suggests that the use of the police as a coercive instrument of the state increases the likelihood of repressive response to dissident movements. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of meso- (group-level) political grievances and could then push a social movement over the precipice of contentious repertoires and into violence in response.Footnote43 Applying this to Boko Haram, research findings indicate that police and military aggression against the movement in 2009, which led to the death of its leader, Muhammad Yusuf the same year, marked a turning point in Boko Haram's pivot towards violence.Footnote44

The situating of Boko Haram within local or global contexts are helpful to understanding how the group presents its Qur’ānic exegesis as a means to energise and mobilise its ‘oppressed’ radical base in a part of the country where religion and ethnicity supersede nationhood loyalties. Certainly, Boko Haram is not the only movement repressed by Nigeria's security forces. Nevertheless, this article shall show that the group's ability to ‘frame’ its discourse in a way that exploits both religious fervour and political opportunism augments its mobilisation potential. Indeed, this exploitation of political opportunism by Boko Haram is a valuable start point of analysis around the movement's use of discourse.

Political opportunism and Boko Haram’s insurgency

By the time Mohammed Yusuf formed Boko Haram as a Salafi organisation c. 2002, ‘12 state governments in the region had already adopted Sharia as their states’ binding penal code’.Footnote45 Thus, the timing of Boko Haram's emergence is instructive as its rejection of the institution of the Nigerian government came just a few years (post-1999) after the implementation of Sharia across Northern Nigeria.Footnote46 One interpretation is that Boko Haram's formative worldview reflected both ‘a rejection of the postcolonial state’ and Northern Muslims’ endeavours ‘to work within the postcolonial state structure to achieve an Islamic state democratically peacefully’.Footnote47

It is also noteworthy that the political and religious institutions, which enforced Sharia, were linked to those individuals with whom Yusuf had fallen out.Footnote48 Consequentially, Yusuf and his group criticised the loose implementation of Sharia. However, the strictest criticisms for the non-Islamic rule of law and systems of governance, where Yusuf cautions that ‘those who follow their legal system and resort to illegitimate rulers (ṭawāghīt) for judgments are polytheists, as the Parliament and representatives combine deifying themselves and associating others with Allah’.Footnote49

However, the federal government showed no inclination to revisit Sharia implementation. This further set Boko Haram at odds with the government in addition to already being ostracised both politically and from the Muslim community.Footnote50

With that being said, let us pause before running off with the idea that Yusuf was a pariah and that Boko Haram, by the mid-2000s, retained no support. Indeed, Boko Haram might have been gradually isolated due to its anti-Western, anti-government, and anti-establishment views. Nevertheless, the movement retained a following. After all, many others disagreed with the co-existence of Sharia with the Nigerian constitution.Footnote51

Moreover, there was also growing concern around the Nigerian government's ‘failure to eradicate corruption’.Footnote52 This situation — which festered in all the years that Yusuf antagonised the police, politicians and the northern Nigerian religious establishment — was one that even the broad implementation of Sharia failed to address. All of this meant that Yusuf and his movement identified a political opportunity and exploited it: attracting large numbers of followers to Boko Haram, not despite Sharia implementation but perhaps even because of it.Footnote53

Consequentially, Yusuf's polemics against the government and the Islamic establishment increasingly pointed to rebellion. This was made clear within the movement's emerging discourse, such as where Yusuf states, ‘when they commit unbelief then rebelling against them is obligatory to the one who is capable; for the one who has no capability then it is incumbent upon him to emigrate, just as we cited previously from the statement of al-Qāḍī ‘Iyāḍ’.Footnote54

Circa 2002, Yusuf did see a legitimate means of accessing political institutions through Bornu Central Senator, Ali Modu Sheriff, who was a one-time political ally. However, once elected, Sheriff failed to keep his promises to Yusuf, causing him to grow even more frustrated with the political structures he now seemed permanently denied access to.Footnote55 This growing lack of access to political institutions led the Yusufiyya, the followers of Yusuf, further away from legitimate means of achieving their goals and more towards violence. Invariably, this pivot towards violence set Boko Haram at odds with Nigeria's repressive authorities.Footnote56

The state of affairs described above is consistent with the theories of political opportunism and the gradual pivot towards violence by social movements.Footnote57 Furthermore, Della PortaFootnote58 and CrenshawFootnote59 argue for the impact of state repression on a social movement's pivot towards violence. Similarly, several other theorists including Brockett,Footnote60 Zimmerman,Footnote61 Opp and Roehl,Footnote62 Mason and Krane,Footnote63 Mason,Footnote64 Davenport,Footnote65 TarrowFootnote66 and EarlFootnote67 suggest that states within which police and military institutions are exploited to repress dissent movements, risk facing even more violent social movements.

This theory, tested within the Boko Haram case, holds explanatory power around why the group's violence gradually escalated as it faced more police harassment. Along this train of thought, it was repression and the murder of Yusuf in July 2009, which acted as the tipping point within the group's pivot to violent insurgency. Whereas yielding a tactical victory for the government, such repression was a strategic mistake.Footnote68 Moreover, the government's repressive posture against Boko Haram was exploited by the movement's discourse over the years that followed.Footnote69

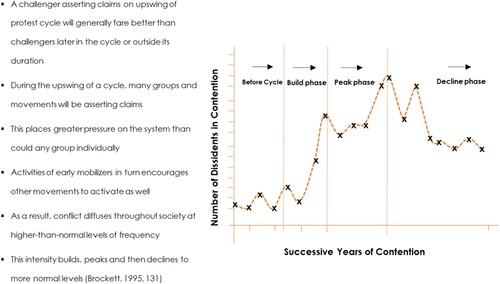

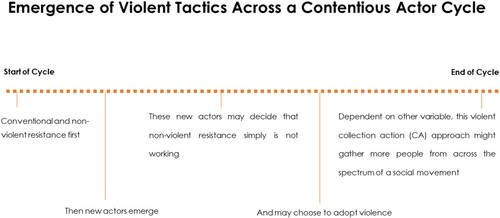

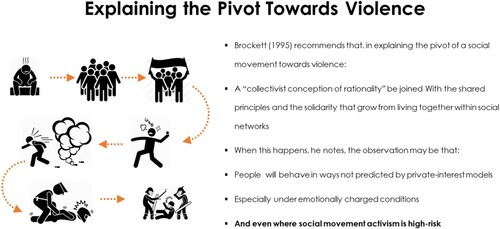

Moreover, as Sidney TarrowFootnote70 argues regarding tactics and cycles of contention, the most violent repertoires employed by a social movement are unlikely to emerge at the start. Instead, these extreme repertoires of contention tend to emerge much later in the protest cycle, as more actors enter the fray, who decide that non-violent resistance against the government is not working. Underpinned by political opportunism theory, attempt to capture this gradual pivot towards violence.

In the case of Boko Haram, the movement in its formative years was radical but non-violent, although this would change. However, by 2009 when Yusuf was assassinated, Shekau took over, further splintering the movement into two factions: Jama’atu Ahlus-Sunnah Lidda’Awati Wal Jihad (JAS) and the Islamic State West Africa province (IS-WA). Attempting to out-compete each other while also maintaining separate military campaigns against the Nigerian government, the violence attributed to ‘Boko Haram’ (which is now at least two separate factions as of 2021) has escalated beyond whatever repertoires of contention the group first employed during its formative phases.Footnote71

Nevertheless, Boko Haram's violence and its ability to exploit existent political opportunism are only one part of its approach to activism. Especially where activism is violent, SMO actors often attempt to rationalise their choice of contentious repertoires.

Boko Haram's ability to justify its ideology and situate its actions within the broader justification for its jihad is captured within the way it has framed its discourse for over a decade. Boko Haram exploited political opportunities in northern Nigeria as it sustained its activism via framing processes. An examination of Boko Haram's discourse between 2006 and 2016 will reveal why and how the movement's actors have employed frames within that discourse. First, however, it is worth explaining how frames and framing processes work and the theory governing their use by SMOs.

Theoretical framework: Frames and why social movements employ them

Frames are culturally determined definitions of reality, which assist the interpretation of objects and events by enabling an individual or group to ‘locate, perceive, identify, label events within their life space and the world at large’.Footnote72 Thus, framing is an agentic process in which actors articulate, demarcate, and narrate events with the hope of influencing others.Footnote73 Viewed this way, frames ‘simplify and condense the ‘world out there’ by selectively punctuating and encoding objects, situations, events, experiences, and sequences of actions within one's present or past environments’.Footnote74 Therefore, frames help social movements render events or occurrences meaningful and thereby organise experience and guide action.

A social movement is ‘a set of opinions and beliefs in a population which represents preferences for changing some elements of the social structure and/or reward distribution of a society’.Footnote75 Thus, social movement actors invariably apply frames, whether intentionally or not, insofar as they act as ‘signifying agents’. A ‘signifying agent’ is one who ‘assigns meaning to and interpret, relevant events and conditions’ in ways deliberately ‘intended to mobilise potential adherents and constituents, to garner bystander support and to demobilise antagonists’.Footnote76

Since the seminal research by GoffmanFootnote77 on framing, the study of this concept has evolved over the decades. Leading this discourse are Benford and SnowFootnote78 who developed three core framing tasks.Footnote79

First, diagnostic framing identifies the problem and attributes blame or causality (that is, diagnosing a problem and a perpetrator). Such framing embellishes a situation, redefining it from being merely unfortunate to being unjust.Footnote80 However, even the realisation of a bad situation is not enough. Action (‘activism’) is required. Thus, the second core framing task, prognostic framing, entails solution-seeking and strategizing. Finally, motivational framing acts as a ‘call to arms’ or ‘rationale for action’. The product of this framing activity by SMOs are ‘collective action frames’ defined as ‘action-oriented beliefs that inspire and legitimate the activities of SMO’.Footnote81

For an SMO to maximise ‘resonance’ (which is to say, provoke reactions from the public), it needs to ‘align’ its frames. The discourse of an SMO is critical here, as the spoken words and written exhortations could help ensure congruency between ‘interests, values and beliefs [of mobilisation targets], and SMO activities, goals, and ideology.Footnote82 Indeed, without discourse-driven frame alignment, the interests, activities and ideologies of an SMO and its members may not be complimentary and effective activism cannot be achieved.

The need for frame alignment can be fulfilled via four alignment processes. First, movement actors clarify and highlight an interpretive frame based on a particular issue, problem, or set of events via frame amplification. Second, via frame bridging, actors link two or more ideologically congruent but hitherto structurally unconnected frames to reach out to those with common grievances. Third, movement actors situate frames beyond primary interests to include issues and concerns of potential adherents. This process is called frame extension. Finally, frame transformation helps movement actors assign new meanings to frames.

A final note on frame theory is that the framing strategies of social movements are typically characterised by movement actors, who conceptually and rhetorically expand frames as it suits them. However, movement actors can also contract frames: by deliberately excluding frame elements. For example, a movement might need to excise a frame if it becomes politically problematic. Thus, frame contraction can be defined as the ‘purposeful exclusion of frames’ when changing political or cultural landscapes render specific frames irrelevant or even toxic by Lavine et al.Footnote83

Overall, framing is critical as it provides an opportunity for social movement agents to amplify selective interpretations of events and ‘diagnose’ them as problems. Therefore, the following section shall explicitly apply framing as an analytical framework for Boko Haram's discourse.

Applying the framework: Boko Haram’s use of frames in discourse

Framing processes are essential in mobilisation by providing a meaningful reason for members to participate a social movement. Boko Haram has successfully framed its discourse and evolve its use of frames over the years. Indeed, Boko Haram's use of frames in its discourse can be traced back to Yusuf's original departure from Izala and his pivot away from the teachings of Ja’afar Adam, his former mentor who had led the Yan Izala movement.Footnote84

Yusuf, to begin with, succeeded in intra-movement framing by discrediting Adam and claiming his former Salafi movement was ‘intolerably corrupt and irredeemable’.Footnote85 This discrediting worked. Yusuf's supporters within the Izala were moulded into a more radical movement, Boko Haram. The group employed the previously-discussed core framing tasks as defined by Benford and Snow.Footnote86

The diagnostic frame for Boko Haram was pointing out that the Nigerian government is secular and can therefore not accommodate Islamic laws and ways of life. Furthermore, the government's failure to implement Sharia has led to persistent socio-economic inequalities in the region.Footnote87 More than that, the problem was what Western education had introduced in terms of normative belief systems that were un-Islamic. As Yusuf put it, ‘First, the spread of the Freudian, Darwinian, Marxist, belief in the development of ethics (Lévy-Bruhl), and society's development (Durkheim), with the focus upon existential secular thought, and the supposed freedom. These are in opposition to the sharī’a texts’.Footnote88

Nor was it just the government that was blamed within this diagnostic framing. Both Kyari MohammedFootnote89 and Abdulkareem Mohammed,Footnote90 along these lines, observe that Boko Haram was also persistently critical of the existing Islamic movements and their acceptance of Westernisation, as well as their willingness to co-exist in a pluralistic society with what Boko Haram view as an innovative (and thus non-permissible) form of Sharia. The prognostic framing process, however, proposed a solution: Boko Haram actors must arm themselves and go to war: put their words in action, and it was not even that difficult to do, according to Shekau's call to arms:

May Allah bring the day when we will put into action what our mouths have uttered. This is so because admonition is not admonition when it is [merely] mouthed, but not translated into action. We pray to Allah to allow us to act upon our statements and safeguard the weapons beside us. Let us put our words into actions.Footnote91

Lastly, the motivational framing posited that it was the duty of Muslims to wage jihad as the generations had done,Footnote92 and in line with the teachings of Ibn Taymiyya.Footnote93 This was especially the case, Yusuf argued, where the government placed Muslims in a situation where they would be sinful. Such motivational framing — a ‘call to arms’ — is identifiable in the exhortations of Yusuf:

On this basis, we follow the rulers of the Muslims according to the Book and the Sunna, even if they are unjust, iniquitous and do wrong, as long as they do not command rebellion against Allah. […] This is our proclamation, and we announce it to the umma. We call the people to reform the creed, application of the Law and to jihad.Footnote94

This is Western education. January, February, March, April, May, June, and July are all names of idols which people worship. […] For instance, January is for the god of love and other months are for the god of praise, god of war etc. This is exactly the meaning of these months. The days of the week Sunday, Monday etc. are also names of idols. They are all names of idols. This is unbelief and they have surrounded us with it. They left us with prayers, fasting and alms-giving, but you should know that if you are engaging in polytheism, all other acts of worship are null and void. Allah told Allah's Messenger: ‘If you associate any others with Allah, He will frustrate your work, and you will certainly be one of the losers (Q39:65).’

[…] We are following [Lord Frederick] Lugard. We are following the constitution. Yet, we still call ourselves the people of Sunna.Footnote95

You should remember what happened in the city of Maiduguri. They cleaned faeces with the Qur’ān in your Western schools. […] When they perpetrated this action, no measure was taken against them. Instead, they stationed weapons at the scene so that whoever intended to instigate chaos because of the incident could be curtailed. […] They employed different tactics to provoke us. Afterwards, we rose to defend ourselves and our religion.Footnote96

Look at this book, the title is al-Muḥallā and it is written by Ibn Ḥazm. It is a well-known book. The volume I am going to quote from is the twelfth, pp. 128–129. In the book, Ibn Ḥazm said: ‘If an entire town that is completely Muslim is invaded by a crusading unbeliever, who is victorious over the town of the Muslims, then says: ‘I have defeated the town, but you can stay in your town and follow the laws of your Qur’ān. However, you must accept that I am the leader of the land.’’ Ibn Ḥazm said: ‘If you stay in the town, you will all be unbelievers.’ Do you hear his statement? This is what Ibn Ḥazm said:

For example, America has captured Iraq, so if they would allow the people of Iraq to follow the Qur’ān, but insisted that America is the country which would run the affairs of the land, both foreign and domestic affairs, including ambassadors and ministers—according to Ibn Ḥazm whoever stayed in the land would become an unbeliever.Footnote97

[…] What is the meaning of government of the people by the people and for the people? Whatever the people want, even if it contradicts the law of Allah, will be accepted. Is that not democracy? Is this what you believe is not polytheism?

Several scholars have made explanations concerning this issue. According to Ibn ‘Uthaymīn, he said democracy is the methodology of the unbelievers. It is not permissible for a Muslim to participate in democracy. He did not say that it is good, let alone for a person to participate in it, or let alone for Muslims to be encouraged to participate in it. This is what Ibn ‘Uthaymīn said.Footnote98

O Allah! We desire to be under one banner, although it is necessary to consider closely before this, as our religion is one of close consideration and knowledge. We desire to have this close consideration, and our goal is the raising of the Word of Allah upon the face of the earth, and seeking His favor. We ask Allah Almighty to aid us in this goal, and to place us among those who are fighting in Allah's path, not among those who are unbelievers fighting in the path of the ṭāghūt.Footnote100

We ask Allah Almighty to help our brothers the fighters in every place. And to destroy America and its allies. And let the world witness generally, and America, Britain and other Crusader [states], and the Jews of Israel who kill Muslims in Palestine every day, the polytheists, the apostates and the hypocrites specifically, that we are with our fighter brothers in Allah's path in every place—those who have sacrificed themselves in order to raise the Word of Allah and to save the downtrodden Muslims under the humiliation of the Jews and the Crusader Christians, like in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Pakistan, Iraq, Muhammad's [Arabian] Peninsula, Yemen, Somalia, Algeria and other countries.

I will remind our brother Muslims of what Shaykh Abu ‘Abdallah Osama b. Laden has reminded them […] Lastly, I send my greeting of peace to the fighters’ commanders, and to the Commander of the Believers in the Islamic State of Iraq, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi […].Footnote102

Concerning frame transformation, whereby new interpretative meanings are assigned to elements of the contentious issue by the movement actors, this is also identifiable within Boko Haram's exhortations. As an example, in the following statements by Shekau in response to a question around Boko Haram's use of Western appliances. The non-permissibility of these appliances is transformed to permissibility by the speaker:

[Moderator reads a question to Shekau]: This questioner is asking about your position concerning the impermissibility of Western education, but he said you are making use of loudspeakers, mobile phones and microphones. If Western education is impermissible, how would they invent all these appliances? What is the ruling on using these electrical appliances?

[Shekau responds]: Yes, Western education is impermissible, but these electrical appliances are good. […] Even if there is no Western education, the people can learn how to create all these appliances. Yes, even without Western education. They do not even learn about these things in Western education, they only learn deception. It is deception. You would see someone with a master's degree in engineering, but cannot manufacture even an engine to produce pasta. Yet, another person is coming from the village who has not attended primary school, in fact, he does not understand ‘go and come,’ but he can dismantle a machine and cobble it together. The so-called engineer cannot do this, yet someone who did not attend primary school can do this. Is it Western education that taught him this knowledge? Therefore, even without Western education, this knowledge can be learnt. Western education is not a revelation. The only thing that cannot be learnt except in front of a scholar is the Qur’ān. Western education is just about the brain. Whatever someone's brain knows, another person can also know the same thing.Footnote105

Next is the concept of frame extension, whereby the discourse is shifted to the very boundaries of a contentious issue without accomodating a less extreme interpretation. An example can be seen in the following statements by Shekau:

However, I am preaching to anyone who prostrates in prayers never to attempt to fight against Islam. Never should you fight against Islam. Even if he is a traveler, you should never fight against him to help an unbeliever. Do you understand my explanation? Even if he is a traveler, once he declares that he is a Muslim, you should never help an unbeliever against him. Do you understand my explanation? It is only permissible for both of you to join hands together and fight the unbeliever and thereafter you can both fight each other. Do you understand? This is the teaching of Islam.Footnote107

Finally, in terms of frame contraction, where interpretative frames are excluded — perhaps because they have become politically toxic for the movement — we also see this in Boko Haram's failure to reference (or embellish the narrative around) the number of Muslim women and children, killed as unarmed combatants, in its suicide bombings. Likewise, on the issue of the drinking of alcohol by mujahideen ( مجاهدين ), Shekau contracts these interpretative frames by leaving excising other interpretations on the permissibility of alcohol consumption within the Qurʾān. Thus, in the exhortation below, specific frames are emphasised, whereas others are contracted:

[Shekau cites the chapters on tribulations and leadership in ‘Tafsīr al-Manār’, ‘Fathh al-bārī bi-sharhh SSahhīhh al-Bukhārī’ and SSahhīhh Muslim.] Even if he drinks alcohol, once the law they follow is the law of the Qur’ān and the Sunna, and he sends soldiers to fight jihād, we do not care about his flaws—and it is compulsory to follow him and his land is a land of the Muslims. However, the leader who governs with the constitution, even if he was born in the middle of the Ka’ba [in Mecca], it is forbidden to follow him. Do you understand my explanation? This is our explanation. All what we are saying, we saw it written in the book.Footnote109

Lies and half-truths: Interpreting Boko Haram’s use of frames

So, what does this testing of framing theory concepts within the Boko Haram case reveal? To begin with, each of the concepts discussed here demonstrates some overlap. Elements of transformation are identifiable within frame contraction, as an example, as there is some scope for intertwining the various framing concepts. Nevertheless, collectively, the three core framing tasks, the four frame alignment processes and also frame extension and contraction contribute to an enriched understanding of the method, so to speak, to Boko Haram's ‘madness’.Footnote110 Boko Haram's interpretative framing of the problem it sees, its objectives, and its motivations underpinned its discourse and helped resonate its ideologies. Resonance is critical here: an SMO's ability to attract followers — to relocate them from the out-group to the in-group — requires that the emergent discourse appeals to recruits while also staying aligned with the movement's core doctrine and the beliefs and motivations of the ‘old guard’.

In its framing of discourse to employ the core framing tasks, the four frame alignment processes, frame extension and frame contraction, Boko Haram has made conspicuous efforts to justify its activism. Indeed, Boko Haram's consistent use of framing within its discourse ‘provided the needed ideological resource upon which mobilisation for such activism was sustained’.Footnote111

Conclusion

In summary, whereas it is unlikely that Boko Haram will substantively change its narrative and thus its preferred repertoires of violent activism, this paper makes it evident that the movement's use of frames, and the emergent discourse, has not held well under closer scrutiny. In theory, this should translate to opportunities for the Nigerian government to discredit Boko Haram's narrative with a powerful religious and political counter-narrative.

Moreover, Shekau's death in May 2021Footnote112 may have removed the last vestiges of the most hardened frames within the original movement. Again, in theory, this should allow for a softened core to gradually emerge within Boko Haram's discourse, as Shekau's detractors within Boko Haram had long resented his Qur’ānic exegesis and the controversial ideologies he presented as fact.Footnote113 However, in practice, Boko Haram, leading into the final months of 2021, has shown no signs of becoming more moderate or ‘softer’. Nor has the group demonstrated a willingness to back-pedal from violence in its activism.

Time will tell what this means for the future of security in a part of Nigeria where the Salafi religious debate remains divided, interpretations of injustice framing continue to exploit the victimhood narrative perceived by some muslims, and the historical tensions between Islam and Western influences endure.

Shekau's demise and inter-factional tensions along political and schismatic lines within Boko Haram might weaken the movement in some ways.Footnote114 However, the aftermath of the disintegration of Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA) in Algeria case serves as a cautionary tale: that even where SMOs splinter and the operational environment becomes ‘a melting-pot for very diverse factions which have little more in common than Islam’, this may not always translate to a more peaceful agenda.Footnote115

Regardless of what Shekau's demise portends, a possible policy recommendation to emerge from this study is that the Nigerian government's counter-radicalization strategy should not only emphasise reintegration and rehabilitation via Operation Safe Corridor and the use of orientation camps such as that at Mallam Sidi, Gombe State. The government should, in addition, develop a substantive bottom-up counter-radicalization component focused on unpacking Boko Haram's discourse and deconstructing the group's use of frames. Moreover, this discourse-focused element of government policy should popularise this study's central argument: that despite the group's claims that its narrative is strictly in line with Qur’ānic exegesis, much of what has been said and written by Boko Haram's previous leadership was carefully framed and approximates lies and half-truths.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Akali Omeni

Akali Omeni joined the CSTPV, University of St Andrews, from the University of Leicester as an Assistant Professor in African Politics. At Leicester, he led (and founded) the Africa Research Group. Omeni joined Leicester from King’s College London, where he taught at the Department of War Studies. He previously worked with the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) and was co-chair of the Africa Research Group at King’s (affiliated to their world-leading War Studies department). In 2019, Omeni won the prestigious ‘Rising Star’ excellence award at King’s. Omeni’s research covers themes relevant to security, rebellion and warfare in Africa. His fourth book, on martial race theory, the colonial army and ethnic politics in Nigeria, is under contract with Hurst and Oxford University Press. A fifth book, Rebel: 500 Years of Small Wars, Civil Wars and Insurgencies in Africa, is also forthcoming with Oxford University Press.

Notes

1 Wiktorowicz, ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’, 2.

2 Chrome, ‘From Islamic Reform to Muslim Activism: The Evolution of an Islamist Ideology in Kenya’; Singerman, ‘The Networked World of Islamist Social Movements’.

3 Wiktorowicz, ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’, 2.

4 Peace, ‘European Social Movements and Muslim Activism’, 2.

5 Ibid.

6 Tilly, ‘Foreword’, xi.

7 Wiktorowicz, ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’, 3.

8 Tarrow, ‘Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action, and Politics’.

9 Wiktorowicz, ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’, 3.

10 Ibid.

11 Peace, ‘European Social Movements and Muslim Activism’.

12 Wiktorowicz, ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’, 3.

13 Ibid.

14 Tilly, ‘Foreword’, xi.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Zulaika and Douglass, '‘Terror and Taboo: The Follies, Fables, and Faces of Terrorism’.

18 Tilly, ‘Foreword’, xi.

19 McCarthy and Zald, ‘Resource Mobilisation and Social Movements: A Partial Theory’.

20 Wiktorowicz, ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’, 4.

21 Ladbury et al, ‘Jihadi Groups and State-Building: The Case of Boko Haram in Nigeria’; Comolli, ‘Boko Haram: Nigeria's Islamist Insurgency’; Agbiboa, ‘The Ongoing Campaign of Terror in Nigeria: Boko Haram versus the State’.

22 Ugwueze, Ngwu and Onuoha, ‘Operation Safe Corridor Programme and Reintegration of Ex-Boko Haram Fighters in Nigeria’.

23 Brigaglia, ‘Boko Haram: the Local-Global Debate’; Brigaglia and Iocchi, ‘“Some Advice and Guidelines:” The History of Global Jihad in Nigeria, as Narrated by AQIM (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb)’; Zenn, ‘Boko Haram: The Local-Global Debate’; Higazi et al., ‘A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and Al-Qa'ida’; Zenn, ‘A Primer on Boko Haram Sources and Three Heuristics on Al-Qaida and Boko Haram in Response to Adam Higazi, Brandon Kendhammer, Kyari Mohammed, Marc-Antoine Pérouse De Montclos, and Alex Thurston’; Bukarti, ‘The Origins of Boko Haram—And Why It Matters’.

24 Bukarti, 'The Origins of Boko Haram—And Why It Matters'; Thurston, 'Boko Haram: The History of an African Jihadist Movement'.

25 Solomon, ‘Counter-Terrorism in Nigeria: Responding to Boko Haram’; Pham, ‘Boko Haram's Evolving Threat’; Eji, ‘Rethinking Nigeria's Counter-Terrorism Strategy’; Onapajo, ‘Has Nigeria Defeated Boko Haram? An Appraisal of the Counter-Terrorism Approach under the Buhari Administration’; Onuoha, Nwangwu and Ugwueze, ‘Counterinsurgency Operations of the Nigerian Military and Boko Haram Insurgency: Expounding the Viscid Manacle’;

26 Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Stars on their Shoulders: Blood on their Hands: War Crimes Committed by the Nigerian Military’; Akanni, ‘Counter-Insurgency and Human Rights Violations in Nigeria’.

27 Zenn and Pearson, ‘Women, Gender and the Evolving Tactics of Boko Haram’.

28 Agbiboa, ‘Out of the Shadows: The Women Countering Insurgency in Nigeria’.

29 Subhramanian et al., 'A Machine Learning Based Model of Boko Haram'

30 Iyekekpolo, ‘The Political Process of Boko Haram Insurgency Onset: A Political Relevance Model’.

31 Amaechi and Tshifhumulo, ‘Unpacking the Socio-Political Background of the Evolution of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria: A Social Movement Theory Approach’.

32 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’.

33 Umar, 'Salafi Narratives Against Violent Extremism in Nigeria'.

34 Benford and Snow, ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and Assessment'.

35 Zenn, ‘Boko Haram: The Local-Global Debate'; Zenn, ‘A Primer on Boko Haram Sources and Three Heuristics on Al-Qaida and Boko Haram in Response to Adam Higazi, Brandon Kendhammer, Kyari Mohammed, Marc-Antoine Pérouse De Montclos, and Alex Thurston'; Higazi et al., ‘A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and Al-Qa'ida’.

36 Higazi et al., ‘A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and Al-Qa'ida’.

37 Gunning, ‘Social Movement Theory and the Study of Terrorism’.

38 Higazi et al., ‘A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and Al-Qa'ida’.

39 Higazi et al., ‘A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and Al—Qa'ida’; Bukarti, 'The Origins of Boko Haram—And Why It Matters'.

40 Amaechi, ‘Islam as a Resource for Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’, 139.

41 Goodwin, ‘State-Centered Approaches to Social Revolutions: Strengths and Limitations of a Theoretical Tradition’, 18.

42 Amaechi, ‘Islam as a Resource for Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’.

43 Della Porta, 'Social Movements, Political Violence, and the State: A Comparative Analysis of Italy and Germany', 82.

44 Omeni, 'Insurgency and War in Nigeria: Regional Fracture and the Fight Against Boko Haram'.

45 Amaechi, ‘Islam as a Resource for Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’, 141.

46 Thurston, 'Salafism in Nigeria: Islam, Preaching, and Politics'; Harnischfeger, 'Democratization and Islamic Law: The Sharia Conflict in Nigeria'.

47 Philips, ‘Boko Haram: Context, Ideology and Actors’, 19.

48 Brigaglia, '‘Ja'far Mahmoud Adam, Mohammed Yusuf and Al-Muntada Islamic Trust: Reflections on the Genesis of the Boko Haram Phenomenon in Nigeria’, 38.

49 Kassim and Nwankpa, 'The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State', 28.

50 Amaechi, ‘From Non-Violent Protests to Suicide Bombing: Social Movement Theory Reflections on the use of Suicide Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’.

51 Philips, ‘Boko Haram: Context, Ideology and Actors’, 19.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Kassim and Nwankpa, 'The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State', 29.

55 Iyekekpolo, ‘Boko Haram: Understanding the Context', 2221.

56 Zenn, 'Unmasking Boko Haram: Unmasking Global Jihad in Nigeria'.

57 Goodwin and Skocpol, 'Explaining Revolutions in the Contemporary Third World'; Hafez and Wiktorowicz, 'Violence as Contention in the Egyptian Islamic Movement'.

58 Della Porta, 'Social Movements, Political Violence, and the State: A Comparative Analysis of Italy and Germany'.

59 Crenshaw, ‘The Causes of Terrorism’.

60 Brockett, ‘A Protest Cycle Resolution of the Repression/Popular Protest Paradox’.

61 Zimmermann, ‘Macro-Comparative Research-On Political Protest’.

62 Opp and Roehl, ‘Repression, Micromobilization, and Political Protest’.

63 Mason and Krane, ‘The political economy of death squads: Towards a theory of the impact of statesanctioned terror’.

64 Mason, ‘Nonelite Response to State-Sanctioned Terror’.

65 Davenport, ‘State Repression and Political Order'; 'Regimes, Repertoires and State Repression’.

66 Tarrow, 'Struggling to reform: Social Movements and Policy Change During Cycles of Protest'; 'Struggle, Politics, and Reform: Collective Action, Social Movement, and Cycles of Protest'.

67 Earl, 'Tanks, Tear Gas and Taxes: Toward a Theory of Movement Repression'.

68 Omeni, 'Insurgency and War in Nigeria: Regional Fracture and the Fight Against Boko Haram'.

69 Kassim and Nwankpa, 'The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State'.

70 Tarrow, 'Struggling to reform: Social Movements and Policy Change During Cycles of Protest'; 'Struggle, Politics, and Reform: Collective Action, Social Movement, and Cycles of Protest'.

71 Omeni, 'Counter-insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations against Boko Haram'; 'Insurgency and War in Nigeria: Regional Fracture and the Fight Against Boko Haram'.

72 Goffmann, 'Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of the Experience', 21.

73 Lavine, Cobb and Roussin, 'When Saying Less is Something New: Social Movements and Frame Contraction Processes', 275.

74 Benford and Snow, ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and Assessment'; Snow and Benford', 614; Snow and Benford, ‘Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization’, 198.

75 McCarthy and Zald, ‘Resource Mobilisation and Social Movements: A Partial Theory’, 1217-8.

76 Ibid.

77 Goffmann, ‘Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of the Experience’.

78 Benford and Snow, 'Master Frames and Cycles of Protest'. In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory'; 'Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and Assessment'; Snow and Benford, ‘Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization’.

79 Snow and Benford, ‘Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization’, 199-204.

80 Benford and Snow, ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and Assessment’, 614.

81 Ibid.

82 Snow et al., ‘Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation’.

83 Lavine et al., ‘When Saying Less is Something New: Social Movements and Frame Contraction Processes’.

84 Mohammed, ‘The Paradox of Boko Haram’.

85 Walker, ‘What Is Boko Haram? Special Report’.

86 Benford and Snow, 'Master Frames and Cycles of Protest'. In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory'; 'Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and Assessment'; Snow and Benford, ‘Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization’.

87 Amaechi and Tshifhumulo, ‘Unpacking the Socio-Political Background of the Evolution of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria: A Social Movement Theory Approach’.

88 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’, 29.

89 Mohammed, ‘The Message and Methods of Boko Haram’.

90 Mohammed, ‘The Paradox of Boko Haram’.

91 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’, 219.

92 Amaechi, ‘From Non-Violent Protests to Suicide Bombing: Social Movement Theory Reflections on the use of Suicide Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’.

93 Omeni, ‘Insurgency and War in Nigeria: Regional Fracture and the Fight Against Boko Haram’.

94 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’, 29.

95 Ibid., 121-125.

96 Ibid., 215-216.

97 Ibid.,123.

98 Ibid.,121-122.

99 Zenn, ‘A Biography of Boko Haram and the Bay'a to Al-Baghdadi’.

100 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’, 234.

101 Zenn, ‘Boko Haram: The Local-Global Debate’; ‘Unmasking Boko Haram: Unmasking Global Jihad in Nigeria’, 1.

102 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’, 124.

103 Zenn, ‘Boko Haram: The Local-Global Debate’, 245.

104 Ibid.

105 Kassim and Nwankpa, ‘The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State’, 127.

106 Ibid., 3.

107 Ibid.,126.

108 Ibid.

109 Ibid., 124.

110 Ahmed, ‘Author's Interview with DSS Borno State Director, and Head of the JTF ORO DSS Component, Ahmed’.

111 Amaechi, ‘From Non-Violent Protests to Suicide Bombing: Social Movement Theory Reflections on the use of Suicide Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’.

112 Salkida, ‘ANALYSIS: What Shekau's Death Means for Security in Nigeria, Lake Chad‘.

113 Zenn and Pieri, ‘How much Takfir is too much Takfir? The Evolution of Boko Haram's Factionalization’.

114 Omeni, ‘Out of the Frying Pan: Abu Shekau's Death and Implications for Boko Haram and Security in North-East Nigeria’.

115 ‘From Marginalization to Massacres: A Political Process Explanation of GIA Violence in Algeria’.

Bibliography

- Agbiboa, Daniel. ‘Out of the Shadows: The Women Countering Insurgency in Nigeria’. Politics & Gender (2021): 1–32. Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000283.

- Agbiboa, Daniel Egiegba. ‘The Ongoing Campaign of Terror in Nigeria: Boko Haram versus the State’. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2, no. 3 (2013). Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.cl.

- Ahmed “Author's Interview with DSS Borno State Director, and Head of the JTF ORO DSS Component, Ahmed.” Maiduguri, 2012.

- Akanni, Nnamdi Kingsley. ‘Counter-Insurgency and Human Rights Violations in Nigeria’. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization 85 (2019): 15–23. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://bit.ly/3GS1QMX.

- Amaechi, Kingsley Ekene. ‘Islam as a Resource for Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 29, no. 2 (2016): 134–150.

- Amaechi, Kingsley Ekene. ‘From Non-Violent Protests to Suicide Bombing: Social Movement Theory Reflections on the use of Suicide Violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram’. Journal for the Study of Religion 30, no. 1 (2017): 52–77.

- Amaechi, Kingsley Ekene, and Rendani Tshifhumulo. ‘Unpacking the Socio-Political Background of the Evolution of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria: A Social Movement Theory Approach’. Journal for the Study of Religion 32, no. 2 (2019): 1–29.

- Amnesty International. 2015. Nigeria: Stars on their Shoulders: Blood on their Hands: War Crimes Committed by the Nigerian Military. London: Amnesty International. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://bit.ly/3k70dRM.

- Benford, R., and D. A. Snow. ‘Master Frames and Cycles of Protest’. In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, eds. C. Morris, and C. McClurg Miller, 133–155. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow. ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An overview and Assessment’. Annual Review of Sociology 26, no. 1 (2000): 611–39.

- Brigaglia, Andrea. ‘Ja’far Mahmoud Adam, Mohammed Yusuf and Al-Muntada Islamic Trust: Reflections on the Genesis of the Boko Haram Phenomenon in Nigeria’. Annual review of Islam in Africa 11 (2012b): 35–44.

- Brigaglia, Andrea. ‘Boko Haram: the Local-Global Debate’. In Boko Haram’s Past, Present and Future, 8 March, 2021. London: RUSI, 2021a. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://bit.ly/3w4X5Kr.

- Brigaglia, Andrea, and Alessio Iocchi. ‘“Some Advice and Guidelines:” The History of Global Jihad in Nigeria, as Narrated by AQIM (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb)’. The Annual Review of Islam in Africa 14 (2017): 27–35.

- Brigaglia, Andrea, and Alessio Iocchi. ‘Entangled Incidents: Nigeria in the Global War on Terror (1994–2009)’. African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review 10, no. 2 (2020): 10–42. Accessed June 5, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/africonfpeacrevi.10.2.02.

- Brockett, C. D. ‘A Protest Cycle Resolution of the Repression/Popular Protest Paradox’. In Repertoires and Cycles of Collective Action, eds. M. Traugott, 117–144. Chapel Hill, and North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1995.

- Bukarti, Audu Bulama. The Origins of Boko Haram—And Why It Matters. 13 January. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://bit.ly/34xFhvd, 2020.

- Bukarti, Bulama. (2019) Making Peace with Enemies: Nigeria’s Reintegration of Boko Haram Fighters. 27 March. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://bit.ly/3odJxcT, 2019.

- Chome, Ngala. ‘From Islamic Reform to Muslim Activism: The Evolution of an Islamist Ideology in Kenya’. African Affairs 118, no. 472 (2019): 531–52. Accessed November 5, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adz003.

- Comolli, Virginia. Boko Haram: Nigeria's Islamist Insurgency. London: Hurst Publishers, 2015.

- Crenshaw, Martha. ‘The Causes of Terrorism’. Comparative politics 13, no. 4 (1981): 379–99.

- Davenport, C. ‘State Repression and Political Order’. Annual Review of Political Science 10 (2007): 1–23.

- Davenport, C. ‘Regimes, Repertoires and State Repression’. Political Science Review 15, no. 2 (2009): 377–85.

- Della Porta, Donatella. Social Movements, Political Violence, and the State: A Comparative Analysis of Italy and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Earl, J. ‘Tanks, Tear Gas and Taxes: Toward a Theory of Movement Repression’. Sociological Theory 21, no. 1 (1995): 44–68.

- Eji, Eugene. ‘Rethinking Nigeria’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy’. The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs 18, no. 3 (2016): 198–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23800992.2016.1242278.

- Goffman, Eric. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of the Experience. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1974.

- Goodwin, Jeff. ‘State-Centered Approaches to Social Revolutions: Strengths and Limitations of a Theoretical Tradition’. In Theorizing Revolutions, ed. John Foran, 11–37. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 1997.

- Goodwin, Jeff, and Theda Skocpol. ‘Explaining Revolutions in the Contemporary Third World’. Politics & Society 17, no. 4 (1989): 489–509.

- Gunning, Jeroen. ‘Social Movement Theory and the Study of Terrorism’. In Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda, edited by Richard Jackson, Marie Breen Smyth, Jeroen Gunning, 156–177. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Hafez, Mohammed M. ‘From Marginalization to Massacres: A Political Process Explanation of GIA Violence in Algeria’. In Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach, ed. Quintan Wiktorowicz, 37–60. Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Hafez, Mohammed M., and Quintan Wiktorowicz. ‘Violence as Contention in the Egyptian Islamic Movement’. In Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach, ed. Quintan Wiktorowicz, 61–88. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Harnischfeger, Johannes. Democratization and Islamic Law: The Sharia Conflict in Nigeria. Frankfurt: Campus, 2007.

- Higazi, Adam, Brandon Kendhammer, Kyari Mohammed, Marc-Antoine Pérouse De Montclos, and Alex Thurston. ‘A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and Al-Qa’ida’. Perspectives on Terrorism 12, no. 2 (2018): 203–213. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26413341.

- Iyekekpolo, Wisdom Oghosa. ‘Boko Haram: Understanding the Context’. Third World Quarterly 37, no. 12 (2016): 2211–228.

- Iyekekpolo, Wisdom Oghosa. ‘The Political Process of Boko Haram Insurgency Onset: A Political Relevance Model’. Critical Studies on Terrorism 12 (2019): 673–92.

- Kassim, Abdulbasit, and Michael Nwankpa. The Boko Haram Reader: From Nigerian Preachers to the Islamic State. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Ladbury, S., H. Allamin, C. Nagarajan, P. Francis, and U. O. Ukiwo. ‘Jihadi Groups and State-Building: The Case of Boko Haram in Nigeria’. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 5, no. 1 (2016): 1–19. Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.427.

- Lavine, M., A. J. Cobb, and C. J. Roussin. ‘When Saying Less is Something New: Social Movements and Frame Contraction Processes’. Mobilization 22, no. 3 (2017): 275–92.

- Mason, T. ‘Nonelite Response to State-Sanctioned Terror’. Western Political Quarterly 42 (1989): 467–92.

- Mason, T., and D. Krane. ‘The political economy of death squads: Towards a theory of the impact of state-sanctioned terror’. International Studies Quarterly 33 (1989): 175–98.

- McCarthy, J., D. and M, and N. Zald. ‘Resource Mobilisation and Social Movements: A Partial Theory’. American Journal of Sociology 82, no. 6 (1977): 1212–241.

- Mohammed, Abdulkareem. The Paradox of Boko Haram. Edited by Mohammed Haruna. Nigeria: Moving Image Limited, 2010.

- Mohammed, Kyari. ‘The Message and Methods of Boko Haram’. In Boko Haram: Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria, edited by Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, 9–32. Leiden: African Studies Centre, 2014.

- Omeni, Akali. Counter-insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations against Boko Haram, 2011-17. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2018.

- Omeni, Akali. Insurgency and War in Nigeria: Regional Fracture and the Fight Against Boko Haram. London: I.B. Tauris, 2019.

- Omeni, Akali. Out of the Frying Pan: Abu Shekau's Death and Implications for Boko Haram and Security in North-East Nigeria. 2 June. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzKGTTPbLGQ, 2021.

- Onapajo, Hakeem. ‘Has Nigeria Defeated Boko Haram? An Appraisal of the Counter-Terrorism Approach under the Buhari Administration’. Strategic Analysis 41, no. 1 (2017): 61–73. Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2016.1249177.

- Onuoha, Freedom C., Chikodiri Nwangwu, and Michael I. Ugwueze. ‘Counterinsurgency Operations of the Nigerian Military and Boko Haram Insurgency: Expounding the Viscid Manacle’. Security Journal (2020). Accessed August 28, 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-020-00234-6.

- Opp, K., and W. Roehl. ‘Repression, Micromobilization, and Political Protest’. Social Forces 69 (1990): 521–47.

- Peace, Timothy. European Social Movements and Muslim Activism. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Pham, J. Peter. ‘Boko Haram’s Evolving Threat’. Africa Security Brief 20 (2012): 1–8.

- Philips, John Edward. ‘Boko Haram: Context, Ideology and Actors’. Al Irfan 4 (2018): 15–40.

- Salkida, Ahmad. ANALYSIS: What Shekau’s Death Means for Security in Nigeria, Lake Chad. 21 May. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://bit.ly/3kbADeC, 2021.

- Singerman, Diane. ‘The Networked World of Islamist Social Movements’. In Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Approach, ed. Quintan Wiktorowicz, 143–63. Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford. ‘Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization’. International Social Movement Research 1, no. 1 (1988): 197–217.

- Snow, David A., E. Burke Rochford, Steven K. Worden Jr, and Robert D. Benford. ‘Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation’. American Sociological Review 51, no. 4 (1986): 464–81.

- Solomon, Hussein. ‘Counter-Terrorism in Nigeria: Responding to Boko Haram’. The RUSI Journal 157, no. 4 (2012): 6–11. Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2012.714183.

- Subrahmanian, V. S., Chiara Pulice, James F. Brown, and Jacob Bonen-Clark. A Machine Learning Based Model of Boko Haram. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2021.

- Tarrow, S. Struggling to reform: Social Movements and Policy Change During Cycles of Protest. Western Societies paper no. 15., Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1983.

- Tarrow, S. Struggle, Politics, and Reform: Collective Action, Social Movement, and Cycles of Protest. Western Societies papers no. 21., Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1989.

- Tarrow, Sidney. Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action, and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Thurston, Alexander. Salafism in Nigeria: Islam, Preaching, and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Thurston, Alexander. Boko Haram: The History of an African Jihadist Movement. New Jersey: Princeton University, 2018.

- Tilly, Charles. ‘Foreword’. In Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach, ed. Quintan Wiktorowicz, x–xii. Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Ugwueze, Michael I, Elias C Ngwu, and Freedom C Onuoha. ‘Operation Safe Corridor Programme and Reintegration of Ex-Boko Haram Fighters in Nigeria’. Journal of Asian and African Studies (2021). Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211047996.

- Umar, M. Sani. Salafi Narratives Against Violent Extremism in Nigeria. Department of History, Ahmadu Bello University. Zaria, Kaduna: Centre for Democracy and Development, 2015.

- Walker, Andrew. What Is Boko Haram? Special Report. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2012.

- Wiktorowicz, Quintan. ‘Introduction: Islamic Activism and Social Movement Theory’. In Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach, ed. Quintan Wiktorowicz, 1–33. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Zenn, J., and E. Pearson. ‘Women, Gender and the Evolving Tactics of Boko Haram’. Journal of Terrorism Research 5, no. 1 (2014). Accessed November 4, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.15664/jtr.828.

- Zenn, Jacob. ‘A Biography of Boko Haram and the Bay’a to Al-Baghdadi’. CTC Sentinel 8, no. 3 (2015): 17–21.

- Zenn, Jacob. ‘A Primer on Boko Haram Sources and Three Heuristics on Al-Qaida and Boko Haram in Response to Adam Higazi, Brandon Kendhammer, Kyari Mohammed, Marc-Antoine Pérouse De Montclos, and Alex Thurston’. Perspectives on Terrorism 12, no. 3 (2018): 74–91. Accessed June 8, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26453137.

- Zenn, Jacob. Unmasking Boko Haram: Unmasking Global Jihad in Nigeria. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2020.

- Zenn, Jacob. ‘Boko Haram: The Local-Global Debate’. Boko Haram’s Past, Present and Future, RUSI Conference, 8 March 2021, London: RUSI, 2021. Accessed June 5, 2021. https://bit.ly/2SL3Nq9.

- Zenn, Jacob, and Zacharias Pieri. ‘How much Takfir is too much Takfir? The Evolution of Boko Haram’s Factionalization’. Journal for Deradicalization 11 (2017): 281–308.

- Zimmerman, E. ‘Macro-Comparative Research-On Political Protest’. In Handbook of political Conflict: Theory and Research, ed. T. Gun, 167–237. New York: Free Press, 1980.

- Zulaika, Joseba, and William Douglass. Terror and Taboo: The Follies, Fables, and Faces of Terrorism. London: Routledge, 1996.