ABSTRACT

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) has been faced with a declining budget for many years, resulting in the deterioration of prime mission equipment, inability to upgrade critical infrastructure, and a very limited capacity to recruit, train, maintain, and deploy forces. This paper argues that the military can alleviate the impact of budgetary constraints through a systematic and structured sweating of land assets under its control. It articulates the rationale for embarking on such an initiative, while proposing approaches and models for the decision-making process. It also highlights the risks of inaction based on precedents in other countries.

Introduction

Asset holders tend to review the status of their holdings through regular valuations. These valuations are designed to enable the asset holder to consider whether to offload some of the assets in the market. In South Africa, all government institutions are required to assess their asset base and report as part of their annual financial statements in line with the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA). Furthermore, National Treasury is mandated to make regulations on matters pertaining to immovable state assets.Footnote1

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) has an extensive immovable asset base, which includes land and buildings. While the issue of large land holdings is not unique to the SANDF, it may become problematic in terms of operational relevance and capacity required to maintain and safeguard such land against illegal use. Furthermore, given the current demand for land for housing, agriculture and infrastructure, military land may become a target for expropriation. This paper seeks to first ascertain, then assess the potential for alternative application of, and value extraction from current land assets of the SANDF. Most of the existing military bases were inherited from the South African Defence Force (SADF) and those bases that belonged to the former ‘Bantustan’ homelands (Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei).Footnote2

After nearly three decades of its existence, the SANDF has to assess the need for its land holdings so that they do not become a burdensome liability. The financial constraints under which the SANDF must perennially function begs the question whether there exists any scope for either rationalisation of military bases, or alternative use of land for value extraction, or even a combination of both.

Comparative military land holdings

The SANDF has access to land that it either owns or leases from the Department of Public Works (DPW). In 1998, the SANDF had 493,200 hectares (or 4932 km2) of land under its control, which, by 2015, had been reduced to 420,000 hectares (or 4200 km2). It is therefore a significant real estate role player in SA.Footnote3 Put in perspective, this would be equivalent to the combined land size of the City of Johannesburg (2300 km2) and Ekurhuleni (1975 km2). The two metropolitan cities house 4.4 million and 3.3 million people respectively. The ratio of population density to land size is irrelevant to SANDF real estate. Like all other defence forces around the world, the SANDF requires large tracks of land for multiple non-habitation purposes. By international standards, relative to South Africa’s territorial size, SANDF land holdings are modest (see ). They constitute less than half a per cent (0.34%) of total national territory, compared to the average of 1.28% for sampled countries displayed in , and compared to countries with less than half of the territorial size of South Africa, such as France (1.6% of total territory) and Germany (2% of total territory). Information on the sizes and locations of military estate is understandably extremely scarce. Global military training areas (MTAs) are estimated at between 5% and 6% of the total territorial surface of Earth, or, quantified in size, at least 50 million hectares (500,000 km2) globally.Footnote4

Table 1. Comparative size of military training areas (MTAs) relative to territorial size.

This implies that the landholdings of the SANDF are not excessive, as illustrated in . However, relative to its operational and related capacity requirements, the question is whether, such landholdings could possibly be in ‘excess’ rather than being ‘excessive’. If it is deemed to be in ‘excess’, that would widen the scope for possible reduction or rationalisation.

Military uses of land

The SA military uses the land for various purposes, but primarily for hosting military bases for training and operational purposes. Countries such as Britain, France and the U.S. have six (6) categories for defence land use. Category ‘A’ is used as administrative centres or for command control purposes; category ‘C’ comprises permanent structures for training and accommodation for troops; category ‘D’ is dedicated to defence works and fortifications used as air force and naval bases or spots for launching ground-based missiles; accommodation for officers and non-commissioned offices fall under category ‘H’; category ‘S’ is used for support installations such as stores for equipment, ammunition depots, and hospitals; and category ‘T’ is reserved for operational training exercises and firing ranges.Footnote5 Given that soldiers work with dangerous equipment, they have areas designated for safety especially for firing different calibre weapons. These are known as ‘weapon danger areas’ (WDA) or range safety template (RST).Footnote6 Shooting ranges for different calibre weapons are generally land that is not necessarily arable, sometimes very mountainous, hostile to human habitation. In 1998, the SANDF dedicated about 2729 km2 of land for rifle ranges only.Footnote7

Military personnel stationed on military bases (Categories C and H) and their families also require infrastructures such as housing, schools, sports, entertainment, and shopping facilities. This stimulates the local economy, especially when by policy essential supplies and services are procured from local service providers. In some cases, military bases serve as economic nodal points for development. Where permanent military bases are to be built, existing spatial planning may have to be adjusted, which may either be supported or resisted by residents. For instance, when the U.S. military sought to establish permanent bases in Pyeongtaek, South Korea, between 2004 and 2007, there were those who supported the move and those who opposed it. The South Korean government had to pass legislation – the Special Act in Support of Pyeongtaek – which incentivised support for the bases by highlighting the benefits to local population that would accrue because of such developments.Footnote8

National regulatory framework on land assets

All land assets that the SANDF currently controls were acquired prior to the enactment of the South African Constitution in 1996.

The Constitution mandates the SANDF to be the ultimate guarantor for the protection and defence of the Republic and its territorial integrity.Footnote9 In executing its constitutional mandate, the SANDF must regularly review, inter alia, its military bases to assess whether they are either enabling or inhibiting it from performing its primary mandate, defending, and protecting the sovereignty of the Republic of South Africa. Furthermore, to regulate access to and utilisation of land, government has passed pieces of legislation such as the Government Immovable Asset Management Act (GIAMA),Footnote10 Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA),Footnote11 and public submissions in relation to the Expropriation Bill were closed on 28 February 2021.Footnote12

Government Immovable Asset Management Act (GIAMA) 2007

The primary purpose of GIAMA is to ensure that all immovable assets held or owned by provincial and national government, are managed in a uniform manner.Footnote13 It is noteworthy that GIAMA does not make mention of SANDF land because the latter is managed by its own specific legislation (the Defence Act). However, its omission in GIAMA, even just cross-referencing it, may be an oversight which may cause confusion or uncertainty in future. It is also not clear whether the South African Department of Defence (DOD) received any exemption from GIAMA in line with its section 15 which allows any organ of state to be exempted for any provision of this Act. It obligates asset holders to keep such assets operational, which necessitates a fitting budget. Disposal of any assets should be done in a manner that promotes socio-economic objectives of government, such as land reform, black economic empowerment, job creation and redistribution of wealth.Footnote14

Even though GIAMA is not a primary legislation for defence land, it is conceivable that it may become relevant in those aspects which are either not covered in the Defence Act or Endowment Property Act, or where there is ambiguity in the interpretation of specific sections applicable to the defence environment. GIAMA objectives are further supported through enactment of the SPLUMA which seeks to manage land use within municipalities. Unlike GIAMA, section 52(1)(b) of SPLUMA requires municipalities to engage the DOD in case national interests may be adversely impacted, including defence.Footnote15 A typical example of such a situation would be when the municipality establishes a housing settlement project next to an existing military shooting range.

Draft Expropriation Bill

The Draft Expropriation Bill (hereafter ‘the Bill’),Footnote16 as published in December 2018 has potentially far-reaching implications for the SANDF in respect of its land holdings. The Bill seeks to empower the Minister of Public Works to expropriate both private and public land for public purpose or in the public interest. The only proviso, in respect of expropriation of property owned by state-owned corporation or entity, such as the SANDF, is the consent of the relevant Minister.Footnote17

Generally, public interest is generated through civic organisations, political parties, local community activists and the media. Unlike where land is expropriated for public purpose, public interest expropriation entails acquisition of land by government for transfer to private parties. The first reported case in which expropriation was ever done based on public interest was Administrator, Transvaal v Van Streepen (Kempton Park) (Pty) Ltd 1990 4 SA 644 (A). In this case, the Administrator of Transvaal expropriated land that belonged to Van Streepen and transferred it to Sentrachem, a private company that was operating a railway line in the Kempton Park area.Footnote18

Defence land

Land owned by or under the control of the SANDF is managed in terms of the Defence Endowment Property and Account Act No. 33 of 1922Footnote19 (‘the Endowment Act’) and the Defence Act of 2002, (as amended in 2020).Footnote20 Defence also leases immovable assets such as land and buildings from the DPW.

Defence Endowment Property and Account Act

One of the major contributors to the defence land holdings emanated from the Endowment Act. Following the formation of the Union of South Africa (‘the Union’) in 1910, the United Kingdom (U.K.) government passed the Endowment Act, which transferred land to the Union government. Some of the conditions of said transfer were the continued use of such land for defence purposes. The Minister of Defence was mandated to use, lease, or sell defence land as may be deemed necessary. This Act was amended in 1986 because South Africa had become a republic in May 1961.Footnote21

Defence Act

In terms of section 65 (1) of the Defence Act,Footnote22 the Minister of Defence may, at the request of the Chief of the SANDF, as and when exigencies of the training require, designate any area, whether on public or private property, as an area in which the SANDF may conduct military exercises. Section 80(2) of the same Act also empowers the Minister to ‘manage, provide, acquire, hire, construct and maintain defence works, ranges, buildings, training areas and land required for defence purposes, either singly or in conjunction with other users’. It also mandates the Minister to ‘sell, let or otherwise dispose of movable or immovable property of the Defence Force which is no longer needed for defence purposes’.Footnote23 This re-emphasised the Minister’s discretionary powers as reflected in the Endowment Act. It may be argued that further elaboration could have been done through section 83 of the Defence Act which refers to the protection of assets, but this section is only dealing with movable assets such as defence animals, equipment, and articles.Footnote24

The necessity to review defence land holdings

The SANDF must continually conduct what it refers to as ‘strategic appreciation’ which encompasses the assessment of all factors that may impact on the mandate of the defence force, inter alia, resource management, including immovable assets such as land. Some of the factors that may necessitate assessment of land holdings may include, but not limited to the following:

Change in military strategy

Internal realignment of the organisation

Change in foreign policy direction or conclusion of a long deployment campaign, thus resulting in closure of temporary, semi-permanent and even permanent bases

Budgetary constraints

Ministerial directive. In this regard, the former Minister of Defence and Military Veterans, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, announced in Parliament on 18 May 2018 that she had ordered the DOD to develop a policy and practice notes for the ‘sweating of surplus Defence Endowment assets’ and ‘to lease under-utilised facilities’.Footnote25 This was also reflected in the DOD Annual Performance Plan 2021/22 as one of the Minister’s strategic priorities.

Modernisation of military hardware, with more focus on simulation, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality. The virtualisation of war has added advantages such as cost saving, negligible environmental impact, improved performance monitoring, customisation of arm-of-service-specific or joint/combined training, and a related reduction in the amount of land required for military training.Footnote26

Economic and political dimensions of military base realignment

The National Development Plan Vision 2030 highlights the importance of land reform, including the de-racialisation of the rural economy and redistribution of land. It also recognises the slow progress made by government in land restitution since 1994. Most of the land that had been made available for redistribution and/or land restitution came not from public or private land, but from land owned by government itself.Footnote27 By 2020, government had by then released 44,000 hectares (440 km2) of state land for redistribution claims and sought to release another 700,000 hectares (7000 km2) for agricultural production.Footnote28

As one of the significant landowners, the SANDF remains vulnerable to government intervention in its land assets. The presence of a military base has both economic and political significance. The local economy tends to benefit from military procurement in terms of regular high-rate-of-use supplies, maintenance, infrastructure development and reinforcement of local and regional safety and security structures, such as the police and emergency support. However, its presence may also bring with it social challenges such as allegations of abuse of women, prostitution, gambling, and other substances.Footnote29 The military has deep-rooted historical traditions and ceremonies; thus, any form of realignment would require participation of local political leaders. Any attempt at closing a military base would not go unnoticed and/or without resistance. Generally, fierce political exchanges and negative media coverage because of closing military bases could expose the military to politicisation or even exploitation for political gain. To deal with this type of political dilemma and risk, the United States Department of Defence, for instance, appointed a commission in May 1988 called the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC).Footnote30

The BRAC process was instituted after it became evident that there were economic, financial, and political consequences to closing or realignment of military bases. Budget is required to rehabilitate physical environment, dispose of properties, and settle running contracts with service providers.Footnote31

In the U.K., base realignment has been linked to the defence strategic review process but with dedicated documents that focus on defence estate management. Since the Defence Strategic Review of 1998 till 2016, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) has set targets of downsizing and/or selling off land assets. For instance, it seeks to downsize by 30% of its defence land holdings by 2040 and generate revenues estimated at £3 billion.Footnote32 However, the responsibility of realigning military bases was assigned to the Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO) in April 2011. This followed the recommendation of the Strategic Defence and Security Review 2010, which called for a transparent process of disposing military landholdings, not holding land longer than necessary, and stipulating that such disposals should ensure value for money and ‘promote development, economic activity and growth’.Footnote33

Given South Africa’s low economic growth, high general unemployment and political polarisation, the military could find it difficult, if not morally indefensible and politically unpalatable, to close or merely realign military bases. However, inaction or avoiding the issue of base realignment has inherent risks and challenges too. It is therefore advisable that a formal review and proposal process, which culminates with parliamentary approval, should be introduced. This will ensure certainty and predictability of the process, and accountability upon execution.

Risks for not reviewing military bases

Fear for adverse political repercussions stemming from closing military bases could paralyse the military into indecisiveness, inertia and being caught up in a strategic ‘no-man’s-land’. Under such circumstances, the SANDF could be forced to retain military bases that are no longer serving the original operational purpose but offers only political expediency. Non-mandatory retention of bases would expose the military to inherent risks such as poor maintenance, potential for ‘land grab’ and environmental hazards. As already stated, the U.S. and the U.K. introduced the BRAC and the DIO respectively to mitigate potential political fallout.Footnote34

Poor maintenance

Under-utilised military bases tend to receive reduced budgetary allocation for maintenance. Infrastructure such as buildings, roads and facilities would start to deteriorate below required standards as funds for maintenance dry up. Criminal elements would seize the opportunity to vandalise buildings and steal equipment, thus contributing to exposure to reputational risk. Perimeter fencing could be compromised, and buildings declared uninhabitable in terms of the law, while critical military infrastructure such as weapons stores and ammunition magazine would become primary targets for criminals.Footnote35 Under these conditions, the morale of military personnel is likely to deteriorate, which could be compounded by collusion with criminals. Eventually, it may lead to total breakdown of military discipline. Criminal elements and political opportunists could target wholly or partially unused defence land for informal occupation or formal expropriation. In fact, the report of the SA President’s Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture of 2019 recommended that state land that is not being used beneficially to the mandate of the SANDF, or ‘state-owned unmaintained buildings’ which are ‘under-utilised, vandalised, abandoned’ should be accessed to reduce pressure on land demand. The same should happen to land that is privately owned by absentee landlords.Footnote36

Land grabbing

Studies conducted by many scholars, including the Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI), show that the land grabbing is a global phenomenon. The motivations for land grabbing vary for each country in terms of causes, intensity, duration, and consequences of resistance to land deals.Footnote37 Land grabbing is generally characterised by poor and/or landless people confronting government or the corporate sector that either has or is perceived to have excessive land, much of which is not necessarily used productively. It could also involve the state releasing land to foreign or international corporations or wealthy people, thus making it unaffordable to landless local citizens. Desperation for land for residential settlement, especially in urban and peri-urban areas in closer proximity to places of employment and amenities could spark resistance from the local people against any land deal involving the state or corporations.Footnote38 In Guatemala, for instance, government was forced to adopt draconian measures to deal with land-grabbing. Using the 1965 counterinsurgent ‘Decree 7 on Preventive State of Emergency’, the Guatemalan government had to deploy the military to apprehend land-grabbers.Footnote39 Similarly, citizens have embarked on land-grabbing campaigns in countries such as Argentina (e.g. challenging the sanctity of private property rights), Philippines (e.g. challenging land rights to Chinese investors), Nicaragua (e.g. reversal of land reforms following the loss of elections by the Sandinistas in 1990), and Mali (e.g. Malibya land deal).Footnote40

As the land debate rages on in South Africa, the risk of land grab through illegal occupation of military land remains the biggest challenge facing the defence establishment. The Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) has admitted its inability to deal with land rights infringements.Footnote41 There was already a noticeable rise in illegal land occupations in Cape Town as the city was still grappling with the issues of COVID-19. The South African Human Rights Commission challenged the City's efforts to evict land grabbers in court.Footnote42 If this involved defence land, especially where there is apparent neglect or non-use of such land and buildings, it could have had far-reaching implications for the SANDF which would entail lengthy legal challenges in court. Unlike the U.S. which used the BRAC process to address the rise in illegal encroachment on defence land during the early 2000s, South Africa does not have a comparable mechanism.Footnote43

Environment

The military is known for its close interaction with fauna and flora, both in positive and negative ways. Nature conservation is a crucial element of defence real estate management. Vegetation on military training areas enables exercises such as camouflage, disguise, and tactical movement. Animals kept in military training areas tend to thrive as they enjoy coincidental military protection from poaching. Defence land with its largely unspoilt terrain is ideal for research, and it is thus frequented by scientists interested in specific or rare species. It is not uncommon for scientists to discover rare animal or plant species on military land. Therefore, nature conservation is managed consciously in line with defence policies and in collaboration with non-military nature conservation authorities.Footnote44 On the negative side, the military makes use of explosives and heavy equipment which impact negatively on the environment. Such negative impact could include pollution, noise, ecosystem degradation, soil, and wildlife disturbance. In Netherlands, it is estimated that the military accounts for between 2% and 5% of national environmental degradation.Footnote45

However, where bases are targeted for closure, or where physical boundaries are not being properly maintained, animals on military land become targets for poachers who opportunistically exploit vandalism or degradation of perimeter fencing. Furthermore, there could be informal settlement which does not necessarily support environmental conservation, as survival is the main priority.Footnote46

Defence options in land asset sweating

There are at least two broad options at the disposal of the SANDF in relation to whether to initiate the sweating of land assets. One option is to wait for national government to request that the defence force either ‘donates’ or ‘relinquishes ownership or use’ of some land assets as may either be identified by Cabinet or by landowners like the SANDF itself. The other option is for the SANDF to identify bases which need to be closed down or leased to private sector as part of realignment of its military strategy. The first option is regarded as ‘top-down’ because it is imposed by Cabinet, while the second option is regarded as ‘bottom-up’, because it is self-initiated and based on an internal reprioritisation process.

Top-down: government imposed

The Defence Act empowers the Minister to make a determination on land use by the military based on consultation with, or advice from the Chief of the SANDF. The legislative approach to land transfer in South Africa has delivered slow, confusing, and complex results, thus causing the landless majority to lose patience. Government resorting to ‘expropriation without compensation’ through either the amendment of Section 25 of the SA Constitution, or through the Expropriation Bill, or both bears testimony to the relative failure of the legislative approach.Footnote47 This explains the rise in land grab among disgruntled citizens as a last resort. Even though participants in most of these land occupations comprised small groups, they have been attracting a lot of media attention and consequent public interest.Footnote48 If such land occupations involved defence land on a large scale, government could possibly invoke the constitutional justification of public interest and advise the SANDF to seek alternative land.Footnote49 Faced with a similar situation in 2011, the U.K. MOD conceded to the demand for releasing defence land by 2014/15 financial year for building about 31,000 homes. The same happened again in 2016 when it undertook to release defence land to build an estimated 55,000 homes.Footnote50 It is therefore self-evident that the top-down approach does not hold too many benefits for the defence force, as political considerations and expediency would prevail over ill-defined national security considerations.

Bottom-up: defence initiated

The bottom-up approach remains the most viable and sensible option for the SANDF in terms of managing its land resources. Through this approach, the SANDF initiates a process of assessing its land resources and their relevance to the implementation of its strategy. Given that it would be self-initiated, and not imposed by Cabinet, the defence force would retain the initiative and ownership of the process. It has discretionary powers to decide which properties to release to the open market, and which not. It would also be able to determine criteria, terms and conditions for the use, possession, or transfer of defence land to interested parties. This approach would ensure that the defence force is seen as being in control of a considered and measured process of land asset sweating, and not either being reactionary, or holding on to land intransigently even though particular land has no military significance, operational use, or any prospects for development in the foreseeable future. This approach would be in line with the DOD’s commitment during the 1998 Defence Review process to introduce new land management models. Accordingly, the SANDF’s land holdings would reflect South Africa’s defensive posture.Footnote51

Approach and process

Once the SANDF has concluded that it prefers a bottom-up approach, one which is self-initiated, rather than a top-down directive from government, it would have to be decisive, unambiguous, and systematic in its decision-making process. The process would include developing some criteria for deciding which land assets are to be either released or retained. These criteria could include, but are not limited to the following:

Operational necessity

Market value

Level of infrastructural investment

Geographic location

Existing contractual obligations with various major service providers

Cost–benefit of moving or retaining the land asset

Likelihood of population encroachment

Socio-economic impact on the local community and local business

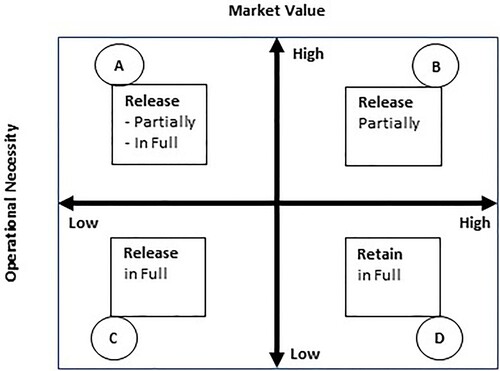

Despite the afore-going list of criteria, there are two key variables that should weigh heavily in the decision-making process, namely, operational necessity and market value. Operational necessity would reflect whether the land asset still has relevance to the defence force’s immediate and foreseeable operational requirements. If affirmative, it would have to be decided on the level of criticality (high, medium, or low). Where relevance to SANDF requirements is low, such land would become a potential target for release. Conversely, should its relevance be high, then such land would likely be maintained, but that does not exclude it from consideration for possible future sweating. Market value and assessing the potential market appetite for defence land, whether sweated land would be able to bring in significant monetary value to the organisation, is equally important. Where market value is high, it provides a prima facie possibility for land sweating. depicts a typology of the two variables, operational necessity and market value, based on the low-high scale for both.

Figure 1. Operational necessity and market value of defence land for asset sweating. Source: Author’s Illustration.

Quadrant A shows a low-level operational necessity but high market value. In this case, it would make sense to release either the whole asset, or part of the asset. The situation is very different in Quadrant B where both operational necessity and market value rate high. This places the decision-makers in a dilemma, as both variables have significant military relevance, which is the core-business of the defence force, and potentially significant returns from the market value. The asset would attract premium value if it were to be placed in the market, which would enable the defence force to raise much-needed capital. In this scenario, it would be advisable to release it partially because it is likely that the private sector might exert more pressure on government in future to release the asset for economic development. On the other hand, Quadrant C shows low operational necessity and low market value combination, which implies that releasing the asset would not have any adverse impact on the defence force's operational function. Therefore, releasing the whole asset may be a strong consideration. The situation is totally different with Quadrant D because there the asset is extremely important for operational purposes, and its market value is very low. It would therefore make sense to retain the asset in full.

Modalities and process

For the SANDF to successfully implement an asset sweating process of its land holdings, it would have to identify and assess land, secure support from other stakeholders, raise capital and design a credible governance process.

Identification and assessment of current land assets

Guided by the Ministerial directive, the Chief of the SANDF would have to identify and assess assets currently owned or occupied by the SANDF. They would be assessed for operational relevance and potential for economic development. Included in the assessment criteria would be factors such as indispensability of the land parcel to the SANDF, vulnerability to land grab or encroachment, and current utilisation and its equivalence in the civilian environment.

Support from key government departments

Key national departments, such as the National Treasury, Public Works and Public Enterprise would be crucial in ensuring a successful land asset sweating for the DOD. National Treasury would, inter alia, enable the DOD to retain revenue emanating from its asset sweating initiatives, instead of being transferred to the national fiscus. DPW controls several assets that the SANDF uses, and therefore these two departments (DPW and DOD) would require common understanding on the management of sweated assets. The Department of Public Enterprise would be instrumental in ensuring that the SANDF collaborates with the various state-owned enterprises to extract maximum revenue for sweated land from the market.

Capital raising campaign

The comprehensive process of asset sweating, including valuations and developing models for alternative use of military land, would require expertise not limited to the DOD. Consideration of legal and socio-economic impact on the realignment of military bases would also require a width of external expertise. In this regard, the DOD as ‘landlord’ would have to raise capital to fund such an important and complex process.

Governance of the process

The process of asset sweating will enjoy legitimacy and support from the public if it is rooted in good corporate governance, characterised by legislative compliance, political oversight, transparency, inclusivity, and competitive participation. The normal constitutional and PFMA provisions of competitive process would have to apply. Given the revelations of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State (or the ‘Zondo Commission’, as chaired by the then Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo), it is vitally important that an asset sweating process is not marred by corruption. In its findings, the commission found widespread corruption which involved some members of the National Executive, Parliament, and senior officials of government and state-owned enterprises, such as the South African Airways.Footnote52 It is advisable that all contractual arrangements for total or partial release of military land include exit clauses or mechanisms. This would become relevant if a changing national security situation dictates that the land that was previously earmarked for release to the market has become operationally relevant. In this regard, military operational readiness would supersede any economic benefits that would be accrued either by the military or private business, or both.

Agency mechanisms

The SANDF would require an agency that would be responsible for conducting a land asset-sweating initiative. In this regard, it has the option of either doing it in-house, or entering into a public-private partnership or adopting a hybrid model.

In-house agency

The SANDF could implement the whole process internally by using either its own capacity, or by using Armscor as agent. This approach would be advantageous in the sense that it could save costs; the SANDF could maintain full control of the process; security of such assets would remain intact; access to information would be provided on a ‘need-to-know’ basis; and the SANDF could retain the leadership of the initiative, which means it may always change its mind on whether to either release or retain any assets. The downside of this approach is that military practitioners may potentially be biased; relevant expertise may not be available; the legitimacy of the process may be questioned, and it may also take too long to conclude because of resource and capacity constraints. In assessing the assets and their potential impact on communities and the environment, the SANDF could use commercially-off-the-shelf (COTS) tools such as the Military Land-use Evolution and Impact Assessment (mLEAM) model. Developed by the University of Illinois, the mLEAM model provides computer-based visual scenario modelling capabilities with regards to the use of military land, its potential impact on the surrounding communities, the resources required to sustain such land use, and engagement with all stakeholders.Footnote53

Public–Private Partnership (PPP)

Since 1998, South Africa’s National Treasury officially adopted and implemented the PPP approach to major projects. PPPs were designed to mitigate the project risks associated with lack of funding, expertise, delivery, and value for money. In 2018, government announced the establishment of the Infrastructure Fund which sought to support PPP initiatives.Footnote54 By mid-2021, 34 PPP projects have since 1998 been completed, with a total value of R89.8 billion.Footnote55 The SA military could identify one of the following options for the approved PPP in operation in South Africa, namely:Footnote56

Design, finance, build, operate and transfer (DFBOT);

Design, finance and operate (DFO);

Design, build, operate and transfer (DBOT);

Equity partnerships; and

Facilities management projects.

Hybrid model

The military could also adopt a hybrid model, which entails using an agent such as Armscor to procure private partners that would constitute a PPP under the auspices of the government acquisition agency. Through such a model, the military would benefit from the combined expertise of Armscor and the private sector, while retaining proximity to the project. While both the in-house and the PPP approaches would still get the job done, the hybrid model has added advantages. It enables the defence force to make informed decisions based on professional advice in doing defence land realignment or value extraction. It can also make use of regular and/or military veterans in implementing the exercise. This will be in line with what countries such as China and Egypt have done in utilising the inherent skills and capacity of soldiers to implement government infrastructure programmes, including those in the civilian environment such as factories, hotels, and building and maintaining military bases.Footnote57

Conclusion

Even though the SANDF has modest land holdings by international standards, it is operating in an environment characterised by extraordinary high demand for land. Political considerations, coupled with financial constraints could compel the SANDF to relinquish land holdings under unfavourable terms, unless it takes the preventative or visionary initiative on its own accord. An urgent review and assessment of existing land assets, supported by solid business cases for alternative utilisation could help alleviate financial dependency on the national fiscus. However, the key success factors are decisiveness and swift action on the matter of sweating defence land assets.

It is crucial that the process of asset sweating is conducted after a thorough assessment of current and future military operational needs, affordability, and the value to be extracted from sweated land for the benefit of the SANDF. The roles of National Treasury and Armscor should be clearly identified to ensure that sound governance principles are adhered to and that concerns of corruption are addressed by securing absolute transparency of the process. Parliament should receive regular status reports in line with its oversight mandate.

Note on the contributor

Moses B. Khanyile holds a PhD in International Politics. He is currently serving as Director: Centre for Military Studies, Stellenbosch University. His research interests include defence industry, defence policy, intelligence, and security sector reform.

Moses B. Khanyile holds a PhD in International Politics. He is currently serving as Director: Centre for Military Studies, Stellenbosch University. His research interests include defence industry, defence policy, intelligence, and security sector reform.

Notes

1 Republic of South Africa (RSA), Public Finance Management Act, Section 76(2)(d).

2 Department of Defence (DOD), Defence Review 1998, Chapter 12.

3 DOD, Defence Review 2015, 14–24; and Defence Review 1998, Chapter 12.

4 Svenningsen, Levin, and Perner, ‘Military Land Use’, 114–15; Zentelis and Lindenmayer, ‘Bombing for Biodiversity’, 1.

5 Svenningsen, Levin, and Perner, ‘Military Land Use’, 114–115; Zentelis and Lindenmayer, ‘Bombing for Biodiversity’, 1, 3; Doxford and Judd, ‘Army Training’, 250; Dobson and Bagaeen, ‘Forces for Good’, 184; Artioli, ‘Sale of Public Land’, 4.

6 Childs, ‘Short History of the Military Use’, 101.

7 Wilson et al., ‘Guided Weapon Danger Area’, 2.

8 DOD, Defence Review 1998, Chapter 12.

9 Martin, ‘From Camp Town to International City’, 967, 969.

10 RSA, Constitution, section 200(2).

11 RSA, GIAMA, No. 19 of 2007.

12 RSA, SPLUMA, No. 16 of 2013.

13 RSA, Draft Expropriation Bill.

14 RSA, GIAMA.

15 Ibid.

16 RSA, SPLUMA.

17 RSA, Draft Expropriation Bill.

18 Ibid.

19 Slade, ‘Public Purpose’, 180–1.

20 RSA, Endowment Property, No. 33 of 1922.

21 RSA, Defence Act No. 42 of 2002. This Act was amended by Defence Amendment Act No. 6 of 2020.

22 RSA, Endowment Property, No. 33 of 1922; RSA, Transfer of Powers, No. 97 of 1986.

23 RSA, Defence Act No. 42 of 2002.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 DOD, ‘Defence Budget Vote 2018/19’.

27 Doxford and Judd, ‘Army Training’, 261.

28 National Planning Commission, National Development Plan, 140.

29 The Presidency, ‘State of the Nation Address’.

30 Woodward, ‘From Military Geography to Militarism’s Geographies’, 728.

31 United States Department of Defence (USDOD), Base Realignment and Closure, 1.

32 USDOD, Base Realignment and Closure, 1–2; Ashley and Touchton, ‘Reconceiving Military Base Redevelopment’, 392.

33 Artioli, ‘Sale of Public Land’, 4.

34 Dobson and Bagaeen, ‘Forces for Good’, 186; Woodward, ‘From Military Geography to Militarism’s Geographies’, 731.

35 USDOD, Base Realignment and Closure, 1; Ashley and Touchton, ‘Reconceiving Military Base Redevelopment’, 392.

36 Patrick, ‘Thieves Breach Security’.

37 Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture, Land Reform and Agriculture, 58, 78, 80.

38 Hall et al., ‘Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation?’, 468–70; McMichael, ‘Rethinking Land Grab Ontology’, 34–5; Zoomers, ‘Globalisation and the Foreignisation of Space’, ‘Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation?’, 430–2.

39 Hall et al., ‘Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation?’, 475–8.

40 Alonso-Fradejas, ‘Anything but a Story Foretold’, 511.

41 Hall et al., ‘Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation?’, 468–70.

42 Gontsana, ‘Activists Threaten’.

43 Githahu, ‘Eviction Rights’.

44 Quesa, ‘Land Use Planning’, 3.

45 Doxford and Judd, ‘Army Training’, 247.

46 Ibid.

47 Lozar et al., Removing the Veil, 61.

48 Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture, Land Reform and Agriculture, 78.

49 Gontsana, ‘Activists Threaten’; Githahu, ‘Eviction Rights’.

50 The Presidency, ‘State of the National Address’; Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture, Land Reform and Agriculture, 80.

51 Artioli, ‘Sale of Public Land’, 4.

52 RSA, Defence Review 1998, Chapter 12.

53 Judicial Commission of Inquiry, State Capture Report, 436–46.

54 Deal and Jenicek, Military Land Use Evolution.

55 National Treasury. Budget Review 2021, 167.

56 National Treasury. Budget Review 2018, 153.

57 Ibid.

58 Abul-Magd, ‘Egypt’s Military Business’; Dobson and Bagaeen, ‘Forces for Good’, 185–7.

Bibliography

- Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture. Final Report of the Presidential Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2019.

- Alonso-Fradejas, Alberto. ‘Anything but a Story Foretold: Multiple Politics of Resistance to the Agrarian Extractivist Project in Guatemala’. Journal of Peasant Studies 42, no. 3–4 (2014): 489–515.

- Artioli, Francesca. ‘Sale of Public Land as a Financing Instrument: The Unspoken Political Choices and Distributional Effects of Land-Based Solutions’. Land Use Policy 104 (2021): 1–11.

- Ashley, Amanda Johnson, and Michael Touchton. ‘Reconceiving Military Base Redevelopment: Land Use on Mothballed U.S. Bases’. Urban Affairs Review 52, no. 3 (2016): 391–420.

- Childs, John. ‘A Short History of the Military Use of Land in Peacetime’. War in History 4, no. 1 (1997): 81–103.

- Deal, Brian, Elisabeth M. Jenicek, and William J. Wolfe. The Military Land Use Evolution and Impact Assessment Model, 1–4. ERDC/CER TN-01-2, November 2001.

- Department of Defence. Annual Performance Plan 2021/22. Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Dobson, Julian, and Samer Bagaeen. ‘Forces for Good’. Town & Country Planning (April 2012): 184–7.

- Doxford, David, and Alan Judd. ‘Army Training: The Environmental Gains Resulting from the Adoption of Alternatives to Traditional Training Methods’. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 45, no. 2 (2002): 245–65.

- Githahu, M. ‘Eviction Rights Dominate First Day of SAHRC Case against City of Cape Town’. Cape Argus, March 26, 2021. https://www.msn.com/en-za/news/other/eviction-rights-dominate-first-day-of-sahrc-case-against-city-of-cape-town/ar-BB1f03gj?ocid=wispr&pfr=1.

- Gontsana, Mary-Anne. ‘Activists Threaten to Take Over Unused Land and Farms’. GroundUp, September 29, 2020. https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/activists-threaten-to-take-over-unused-land-and-farms-20200929.

- Hall, Ruth, Marc Edelman, Saturnino M. Borras, Jr., Ian Scoones, Ben White, and Wendy Wolford. ‘Resistance, Acquiescence, or Incorporation? An Introduction to Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘from Below’’. Journal of Peasant Studies 42, no. 3–4 (2015): 467–88.

- Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State. Judicial Commission of Inquiry into State Capture Report, Part 1, Volume 1, 2021.

- Lozar, Robert C., Wade Smith, William Croisant, Glenn Rasmussen, and Thomas Hale. Removing the Veil: Interest of Military Land Managers in Using Declassified and Classified Imagery, 1–94. US Army Corp of Engineers, August 2000.

- Mapisa-Nqakula, Nosiviwe. ‘Defence Department Budget Vote 2018/19’ (Speech by the South African Minister of Defence and Military Veterans, South African Parliament, Cape Town, 18 May 2018). https://www.gov.za/speeches/minister-nosiviwe-mapisa-nqakula-defence-dept-budget-vote-201819-18-may-2018-0000.

- Martin, Bridget. ‘From Camp Town to International City: US Military Base Expansion and Local Development in Pyeongtaek, South Korea’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (2018): 967–84.

- McMichael, Philip. ‘Rethinking Land Grab Ontology’. Rural Sociology 79, no. 1 (2014): 34–55.

- Patrick, Alex. ‘Thieves Breach Security at SA Air Force Base’. Timeslive, May 11, 2021. https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2021-05-11-thieves-breach-security-at-sa-air-force-base/.

- Quesa, Tony. ‘Land Use Planning May Include Military Bases’. Business Journal 19, no. 14 (16 January 2004): 1–3.

- Ramaphosa, Matamela Cyril. State of the National Address. Address to Joint Sitting of Parliament, Cape Town, February 13, 2020. https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-2020-state-nation-address-13-feb-2020-0000 (accessed September 15, 2021).

- Republic of South Africa. Public Finance Management Act (PFMA), No. 1. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1999.

- Republic of South Africa. Defence Act, No. 42. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2002.

- Republic of South Africa. Defence Amendment Act, No. 6. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2020.

- Republic of South Africa. Draft Expropriation Bill. National Government Gazette No. 1409. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2019.

- Republic of South Africa. Government Immovable Assets Management Act (GIAMA), No. 19. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2007.

- Republic of South Africa. Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act 28. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2002.

- Republic of South Africa. Occupational Health and Safety Act, No. 85. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1993.

- Republic of South Africa. Prohibition Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act, No. 70. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1970.

- Republic of South Africa. South African Defence Review. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1998.

- Republic of South Africa. South African Defence Review. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2015.

- Republic of South Africa. Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA), No. 16 of 2013. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2013.

- Republic of South Africa. Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act Repeal Act 64. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1998.

- Republic of South Africa. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1996.

- Republic of South Africa. Transfer of Powers and Duties of the State President Act, No. 97. Cape Town: Government Printer, 1986.

- Slade, Bradley Virgill. ‘‘Public Purpose or Public Interest’ and Third Party Transfers’. PER/PELJ 17, no. 1 (2014): 167–206.

- South African National Planning Commission. National Development Plan 2030 – Our Future, Make it Work. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2012.

- South African National Treasury. Budget Review 2018. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2018.

- South African National Treasury. Budget Review 2021. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2021.

- Svenningsen, Stig Roar, Gregor Levin, and Mads Linnet Perner. ‘Military Land Use and the Impact on Landscape: A Study of Land Use History on Danish Defence Sites’. Land Use Policy 84 (2019): 114–26.

- Union of South Africa. Endowment Property and Account Act No. 33. Union Gazette Extraordinary. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1922.

- United States Department of Defence. DOD Base Realignment and Closure: Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Estimates. Washington: Department of Defence, 2019.

- Wilson, Shaun A., Ivan J. Vuletich, Duncan J. Fletcher, Michael D. Jokic, Michael S. Brett, Cameron S. Boyd, Warren R. Williams, and Ian R. Bryce. Guided Weapon Danger Area & Safety Template Generation – a New Capability, 1–14. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, August 2008.

- Woodward, Rachel. ‘From Military Geography to Militarism’s Geographies: Disciplinary Engagements with the Geographies of Militarism and Military Activities’. Progress in Human Geography 29, no. 6 (2005): 718–40.

- Zeinab, Abul-Magd. ‘Egypt’s Military Business: The Need for Change’. Op-Ed Newspaper, November 19, 2015. https://www.cmi.no/publications/5672-egypts-military-business-the-need-for-change.

- Zentelis, Rick, and David Lindenmayer. ‘Bombing for Biodiversity – Enhancing Conservation Values of Military Training Areas’. Conservation Letters 8, no. 4 (2014): 1–7.

- Zoomers, Annelies. ‘Globalisation and the Foreignisation of Space: Seven Processes Driving the Current Global Land Grab’. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37, no. 2 (2010): 429–47.