ABSTRACT

This paper investigates practice dynamics in kitchens situated at the boundary between markets and consumption. The kitchen is conceptualized as a market-consumption junction, a space where multiple concerned actors in markets and consumption come to shape, and get shaped by, the practices in the kitchen. Drawing upon archival research of the Swedish household magazine Husmodern (1938–1958), this study traces two matters of concern in and around the kitchen: the scarcity of resources in food markets and the scarcity of time to prepare food for consumption. Findings reveal how thrifty and convenient practices became enacted, and their transformative implications for consumption, demand, and market action. The mechanisms involved in disrupting and reconnecting the dynamic elements of practices (meaning, competence, and objects) are explained through the notions of concerning, agencing, and overflows, which recursively work to redraw the boundaries between markets and consumption to establish novel practices.

Introduction

As times go by, markets and consumption change. New spaces and practices emerge as markets bridge, connect with, transform, and are transformed by consumer cultures (Chelekis and Figueiredo Citation2015; Otnes and Maclaran Citation2015). Yet, we know little about how such bridges connect markets with consumption and how they influence practice change. Previous studies of practice dynamics have looked into the overall regimes and conventions that work to direct and disrupt the development of practices (Hand and Shove Citation2004; Shove and Pantzar Citation2005; Arsel and Bean Citation2013; Phipps and Ozanne Citation2017). Herein, the development of practices involve both the internal dynamics of practice elements and their external linkages (Hand and Shove Citation2004; Shove and Pantzar Citation2005; Warde Citation2005; Arsel and Bean Citation2013). This has been suggested as a fruitful field to examine the boundaries between markets and consumption. However, how spaces and mechanisms work to link markets with consumption through the integration of new practice elements need further elaboration. We thus ask: What role does the link between markets and consumption play in influencing practice change? And, how do practice changes redraw the boundaries between markets and consumption?

In this paper, we seek to understand practice change at the boundary between markets and consumption as situated in and around the twentieth-century kitchen. We conceptualize the kitchen as a market-consumption junction (cf. Cowan Citation1987) as it is a site that reflects significant social changes over the past hundred years (Conran Citation1977), mirroring transitions in labour, leisure, gendered roles, technology, resource use, and consumption. It is both an abstract space of political negotiations amongst actors seeking to influence the direction of production and consumption (Oldenziel, de la Bruhèze, and de Wit Citation2005) and a concrete place where different actors and artefacts come together to enact practice change (Hand and Shove Citation2004). By studying situated practices (Knorr Cetina Citation1981; Woermann Citation2017) in a market-consumption junction we foreground neither markets nor consumption; instead, we study their interaction and the practices that emerge at the boundaries between them.

We should, however, first recognize that the meaning of consumption suffers from a chronic ambivalence; consumption as the acquisition of goods through markets versus consumption as using-up (Warde Citation2005). Whereas economics and marketing often see consumption as equivalent to acquisition (see, e.g. Alderson Citation1965), the social sciences have been more concerned with the post-purchase use and appropriation (Warde Citation2005; Shove and Araujo Citation2010). In the former interpretation, consumption is intrinsically part of markets. In the latter, consumption has to be understood more broadly as involving acquisition as well as use and disposal (Arnould and Thompson Citation2005). Needless to say, the notion of boundaries between markets and consumption only applies when we consider consumption in the broader sense and when acquisition involves market-based exchanges. Boundaries nonetheless constitute a particularly interesting space to study as boundaries are markers of difference as well as inclusion (Lamont and Molnár Citation2002). As such, boundaries make up sites of contestation and change (Abbott Citation1995), involving arduous work (Gieryn Citation1983) by multiple concerned actors (Geiger et al. Citation2014). Indeed, we argue that it is at the very boundaries that matters of concern (Latour Citation2004) may arise that trigger practice changes to emerge.

We track the evolution of two matters of concern through the analysis of the Swedish housewife magazine Husmodern (1938–1958): “the scarcity of resources in food markets” and “the scarcity of time in consumption,” as they rearrange boundaries through the enactment of thrifty and convenient practices in the kitchen. Drawing on Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017) and their study of resource scarcity as a source of practice change, we extend this work to show how the mechanisms of concerning (Mallard Citation2016) and agencing (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016) drive changes at the boundary between markets and consumption. Through processes of concerning, as concerted efforts to render boundaries problematic, interactions between markets and consumption redraw those boundaries and agence practice change. Our key theoretical contribution moves beyond the identification of the rearrangement of practice elements as sources of practice change (Hand and Shove Citation2004; Arsel and Bean Citation2013), and towards an understanding of the dynamics of change generated by the interplay between concerning and agencing actions.

The structure of the paper is as follows: first, we review the literature to understand how market-consumption boundaries have been conceptualized. We build on the notion of matters of concern as central to the agencing process of the transformations of boundaries between markets and consumption in the kitchen: a market-consumption junction (Cowan Citation1987). After presenting our methodology, we analyse the findings relating to two matters of concern – scarcity of resources and time – that drove key changes in kitchen practices: thrift and convenience. The paper ends with a discussion of our findings and a conclusion of our theoretical contributions.

Bridging boundaries between markets and consumption

To begin with, it is worth noting that there is a sparse but burgeoning social science literature on boundaries. Still, in their comprehensive review, Lamont and Molnár (Citation2002) complain about the fragmentation of the literature while Strathern (Citation1996, 520) notes that “the concept of boundary is one of the least subtle in the social science repertoire.” For the purposes of this paper, we look at boundaries as (1) sites of difference; (2) standing in a synchronic relationship to entities; (3) continuously being drawn and redrawn through the “boundary work” (Gieryn Citation1983) involved in defining and enforcing markers as well as connecting points between separate entities. We now proceed to discuss how the boundaries between markets and consumption have been conceptualized in various literatures, primarily as connected to consumer culture theory, constructivist market studies, and practice theories.

Within consumer culture theory, a number of studies have recently highlighted the role of consumption in market dynamics (e.g. Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013; Martin and Schouten Citation2014). Culturally derived meanings remain an important theme, as exemplified by studies on the legitimation (Humphreys Citation2010) and destigmatization (Sandikci and Ger Citation2010) of consumption. For example, Thompson and Coskuner-Balli (Citation2007) see markets as commodifying and depoliticizing countercultural symbols and practices, adding the possibility of countervailing responses. In this literature, the boundaries between markets and consumption are examined at the level of broader socio-cultural systems, which imbue market exchanges and consumption with particular meanings, negotiated amongst multiple market constituencies, not just producers and consumers (e.g. media, policy-makers, regulatory authorities). Thus, the boundaries between markets and consumption centre on how different market actors make distinctions between meanings attributed to objects, practices, and spaces (Lamont and Molnár Citation2002; Dolbec and Fischer Citation2015).

Within constructivist market studies, boundaries between markets and consumption have been addressed mainly through the notion of mediation. Mediation was first used by Hennion, Méadel, and Bowker (Citation1989) to describe the work of advertisers in connecting the otherwise estranged worlds of supply and demand. The work of these professionals does not dissolve boundaries but, instead, remodels the relationship between supply and demand through the multiplication of crossing points between the two, so that: “When the object appears at the end of the process, […] it is just as aware of its own future consumer as of its manufacture” (Hennion, Méadel, and Bowker Citation1989, 208).

Cochoy and Dubuisson-Quellier (Citation2013) take this notion further and use the term market professionals to account for the range of people (e.g. consumer activists, distributors), occupations (e.g. design, packaging), and devices (e.g. consumer reports, standards) whose task is to construct, organize and manage markets. But, market professionals are subject to competition from actors who are normally considered to be external to the market. For example, consumer groups and social movement organizations linked to particular causes (e.g. environmental protection, fair trade) take an active role in encouraging or discouraging particular forms of consumption, or even boycotting the sale of goods (Dubuisson-Quellier Citation2013).

Adopting a broad historical perspective, Oldenziel, de la Bruhèze, and de Wit (Citation2005) use mediation to refer to the role of actors and institutions who played a role in coordinating mass production and consumption in the twentieth century. Herein, the notion of mediation junction refers to the abstract spaces where these different groups (e.g. users, producers, consumer groups, the State) vied for influence over technological and market development. The term junction thus privileges an interpretation of boundaries as sites of connection, of flows coming from different directions joining together. The term consumption junction, first introduced by Cowan (Citation1987), was a call for the study of the evolution of domestic spaces, such as kitchens, as the product of the cumulative work of users. De Wit et al. (Citation2002) use the term innovation junction to describe the co-evolution of complementary office technologies under the watchful gaze of business consultants. In short, the notion of mediation regards boundaries as sites of connection between markets and consumption. Connections and crossing points are patiently built and rebuilt by a host of actors, namely market professionals and users.

Practice theories suggest that the link between markets and consumption is more nuanced and indirect than the approaches surveyed so far indicate. A practice is organized by rules, objectives, projects, materials, and shared understandings that are distinct from, and stand above, the understandings of individual practitioners (Reckwitz Citation2002). A practice depends on the active integration of different elements:

A practice – a way of cooking, of consuming, of working, of investigating, of taking care of oneself or of others, etc. – forms so to speak a “block” whose existence necessarily depends on the existence and specific interconnectedness of these elements, and which cannot be reduced to any one of these single elements. (Reckwitz Citation2002, 249–250)

In sum, the boundaries between markets and consumption are made and remade in the situated performance of practices and at the sites where the work of integration is accomplished (Knorr Cetina 1981; Hand and Shove Citation2004; Woermann Citation2017). Analysing the dynamics of practices reveals that coherent patterns of consumption are influenced by how disparate practice constituents are brought together. This approach has been used to theorize “mundane ongoing processes” (Arsel and Bean Citation2013), as well as changes in (Hand and Shove Citation2004) and disruptions to (Phipps and Ozanne Citation2017) everyday practices.

Arsel and Bean (Citation2013) suggest that discursively constructed taste regimes orchestrate multiple practices. A taste regime might emanate from a loosely linked network of media or from a singular source such as an influential magazine or blog. A regime orchestrates objects, doings, and meanings by integrating the dispersed practices of problematization, ritualization, and instrumentalization – by continuously questioning the alignment between objects and meanings, establishing ritualized behaviours that align objects with doings, and enrolling objects and doings to actualize meanings.

Hand and Shove (Citation2004) address practice regime change. They define a regime as the way in which materials, images, and forms of competence hang together at different points in time. Based on an exploration of three kitchen regimes, they propose that regime change is best understood as the shifting set of relations between the constitutive elements of a practice where the kitchen, as an orchestrating concept, facilitates and encourages the integration of certain constitutive elements.

Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017) explore disruptions in water consumption caused by a severe drought. Before the drought, consumers operated in the ontological state of embedded security where the alignment of practice elements was stable and effortless. While some consumers eventually reached a new state of stability and security within the new conditions, many struggled. For example, the “obdurate materiality” of rented apartments obstructs some attempts at practice realignment. Material and financial constraints limit the opportunities of some households to enact new practical understandings.

Like Hand and Shove (Citation2004) and Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017), we explore changes in practices. While Hand and Shove (Citation2004) and Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017) deal with the adjustments of practices within moments of change, they do not explicitly address the mechanisms involved in movements between different stages. Our context, not unlike Phipps and Ozanne’s (Citation2017), is one of unsecured access to consumption resources. However, we focus on the adjustments that take place as a practice moves from one regime to another. In particular, we ask what role the link between markets and consumption plays in practice change. Hand and Shove (Citation2004) and Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017) emphasize consumers’ appropriation of technologies, images, and forms of competence, whereas we in addition zoom out to explore the realignment of practices in the recursive relationship between markets and consumption.

In order to do so, we use the notion of matters of concern (Latour Citation2004) to examine the drivers for change. We suggest that matters of concern introduce controversies and disagreements, leading to practice changes with attendant implications for the reworking of boundaries between markets and consumption.

Matters of concern at the boundaries between markets and consumption

Markets bring together social, economic, and political worlds (Callon Citation2007; Geiger et al. Citation2014). The relationship between them is governed by how the boundaries of markets are set, since boundaries establish what belongs to the realm of markets and what does not. However, it is in relation to the very same boundaries that matters of concern may arise (Latour Citation2004; Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2009).

According to Callon (Citation2007), the development of concerns emerges through the work of multiple entities, which involves the appearance of new identities as emergent concerned groups. Matters of concern provide the means to connect and bind members of these groups together, to develop common actions. Thus, market boundaries represent a focal point for concerned groups who threaten market spaces by rendering matters of concern visible and demanding that they are taken into account (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2009).

Specifically, matters of concern distinguish individual interests from collective concerns (de la Bellacasa Citation2011). Geiger et al. (Citation2014, 2) define concerns in markets as “those things and situations that – for better or for worse – are related to us, can affect us and worry us in the current context of liberal market democracies.” Matters of concern thus also invoke the boundaries between markets and politics. As Callon (Citation2010, 165) suggests: “Saying and doing the economy […] means entering into the agonistic field where the delimitation-bifurcation between the economy and politics is constantly being debated and played out.”

Mallard (Citation2016, 56–57) suggests turning the noun matters of concern into the verb concerning, to refer to: worrying, creating public debate to make visible the social and political problems associated with economic activity; relating, linking the economic and the non-economic; and influencing, transforming markets to handle non-economic issues (also see Geiger et al. Citation2014). Compared to processes of problematization that deal with “deviations from normative and cultural standards” (Arsel and Bean Citation2013, 907), we define concerning as the processes performed by multiple actors trying to challenge the normative standards and established boundaries by bringing in alternative teleoaffective structures of practices (cf. Schatzki Citation1996, Citation2012). We further suggest that concerning fruitfully can be paired with the notion of agencing, which we turn to next, to better understand the processes and practices involved in redrawing the boundaries between markets and consumption.

Agencing and concerning as boundary work

Agencements are defined as the “arrangements endowed with the capacity of acting in different ways depending on their configuration” (Callon Citation2007, 320). The notion of agencement proposes a move away from individual agency to the complex socio-material arrangements that straddle the boundaries between markets and consumption (Callon Citation2007, Citation2008; Çalışkan and Callon Citation2010; D’Antone and Spencer Citation2015; Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016). Moreover, Gherardi (2016) suggests that the notion of agencement could help practice researchers to track the multiple actors (human as well as non-human) and resources (e.g. knowledge, rules) that come together to form a practice.

In this paper, we adopt the verb agencing, the gerund of the French verb agencer, to mean both “arranging market entities (agencing as producing specific agencements) and putting them in motion (agencing as ‘giving agency’, that is, converting people, non-human entities or ‘hybrid collectives’) into active agents, or rather actors … ” (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016, 4). Furthermore, agencing efforts produce differences and asymmetries (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016) that may lead to the creation of a concerned public and concerning activities – political actions geared to making markets accommodate matters of concern. Thus, while processes of agencing may produce matters of concern, it may, in turn, spur new agencing efforts to take these concerns into account.

In relation to the boundaries between markets and consumption, we propose that concerning efforts seek to modify the frames in which current interactions take place, while agencing actions work to establish and enact new boundaries. Concerning and agencing can thus be seen as two integrated forms of boundary work (cf. Gieryn Citation1983), disrupting as well as repairing boundaries.

Drawing upon the previous literature review, we next present a conceptual framework through which we will study the processes of concerning and agencing as situated practices in kitchens where markets and consumption meet.

Conceptual framework: studying kitchens as market-consumption junctions

As a reminder, practices comprise multiple elements that come together as an integrated block (Reckwitz Citation2002). Where and how the work of integration is accomplished remains an open, empirical question. We propose to study the dynamics of integration processes by focusing on kitchens.

We view the kitchen as multi-dimensional (cf. Oldenziel and Zachmann Citation2009): (1) a site containing multiple artefacts and technologies (e.g. cookers, freezers); (2) a spatial arrangement where particular domestic practices are conducted (e.g. cooking, socializing); (3) a node in a complex socio-technical work connecting homes to infrastructures such as gas, electricity, and waste disposal; (4) a node connecting markets to consumption generated by domestic practices (e.g. cooking, cleaning). Thus, the kitchen constitutes a meeting place of multiple elements linked to both markets and consumption that become defined in relation to each other. We conceptualize this as a market-consumption junction, which is a place where the different elements of practices (i.e. meanings, competence, objects) became activated and rearranged (cf. Hand and Shove Citation2004; Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012).

Our empirical study explores changes in these practice elements generated through the recursive relationship between concerning and agencing. We follow processes of concerning through tracing acts of worrying, relating, and influencing (Mallard Citation2016). Moreover, we look at processes of agencing as the rearranging of different elements and the work done to put them in motion, which produce actors with a capacity to act (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016). Next, we describe the situated methodological approach employed in our empirical study (Knorr Cetina 1981; Woermann Citation2017).

Methodology

Our interest in how matters of concern become manifested in the kitchen suggests a focus on major societal changes. World War II and the following post-war period represent a period of distinct changes in consumption levels and allow us to trace the changing patterns of consumption before, during, and after a major crisis (Trentmann Citation2012). In order to track these events over time, we conducted an in-depth archive study of a household management magazine (cf. Hand and Shove Citation2004; Cochoy Citation2010; Hagberg Citation2015). Following Hand and Shove (Citation2004) and Cochoy (Citation2010), we acknowledge the media as an influential actor playing a role in shaping ideals and practices. We chose to examine the magazine Husmodern (“The Housewife”), which was targeted primarily at middle-class housewives in Swedish cities, thus creating the ideals of the middle classes (Olsson Citation2012).

There are several reasons for choosing this specific magazine. First, it was a well-recognized magazine in Sweden published during World War II and the post-war period (1917–1988). Secondly, the magazine represented a varied outlet as attested by the editorial columns written by home economists, recipes, readers’ letters, stay-at-home stories of prominent housewives, and advertisements. This variety of content allowed us to capture the perspectives of multiple actors and track matters of concern as they were presented to Swedish housewives. In line with Hand and Shove (Citation2004), we do not claim that the magazine acted as a faithful representative of these actors since content was mediated by the magazine’s journalists and editors to varying degrees. However, we can still claim that the magazine provides an insightful glimpse into the multi-actor work of concerning and agencing.

Previous studies on kitchen practices have highlighted historical matters of concern that are broadly understood to have disrupted, altered, and reshaped practices (see, e.g. Floyd Citation2004; Hand and Shove Citation2004; Jerram Citation2006; Vileisis Citation2008; Theien Citation2009; Calder Citation2012; Shove Citation2012; Tellström Citation2015). Based on this literature and readings of Husmodern, we tried to discern matters of concern in the data that had observable new agencements and that brought about changes in practices (Araujo and Kjellberg Citation2016). We subsequently chose to focus on two key matters of concern: (1) scarcity of resources in food markets during wartime and (2) scarcity of time in performing practices in the kitchen. We noted the thrifty and convenient practices being promoted to help housewives cope with these concerns.

Adopting the methodological principle of situationalism (Woermann Citation2017), we looked for evidence of the interlinked processes of concerning and agencing in the concrete situations of Husmodern’s published materials. The magazine is seen as being part of the constructing and addressing of matters of concern that were deemed relevant for the performance of practices situated in the kitchen. As a complement, we also looked into other contemporary sources, such as cookbooks and advice directed at the housewife during these periods.

We accessed issues of Husmodern (1923–1963) from the Carolina Rediviva archive library in Uppsala, Sweden, undertaking a broad review of printed issues between 1923 and 1973 before narrowing down the selection to at least two issues from each year between 1938 and 1958. Even though manifestations of thrift and convenience can be found in many different time periods (cf. Trentmann Citation2012), we selected 1938 as the starting point as it clearly marked a moment before war began and thrift emerged as a concern. The following two decades (representing one generation) were deemed appropriate to trace substantive changes towards convenient practices. Issues from 1938 to 1958 were chosen systematically based on the first issues of January and July, in addition to other relevant issues. The selected issues were manually reviewed and photographed, using a digital camera, which resulted in a data set of around 2300 pictures of texts and images. Data were filed and shared among the co-authors for analysis, allowing us to track the emergence of thrifty and convenient practices as a response to the matters of concern.

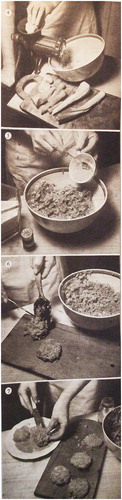

We started the analysis by studying these texts and images, and making running notes about the key changes identified each year. We searched for manifestations of practices enacting thrift and convenience and the related matters of concern. As a next step, a spreadsheet was compiled that presented the different manifestations of thrift and convenience, as well as associated processes of concerning and agencing. We thus paid attention to any objects or activities that made claims of, or were connected to, the themes of thrift and convenience. exemplify the type of representations featured in the magazine. We noted how some concerns were already taken for granted in the text and we sometimes had to track back in time to understand the emergence of a matter of concern. Moving forward, we also noted overflows (cf. Callon Citation1998), stemming from agencing efforts to promote thrift and convenience. We then linked the manifestations of thrift and convenience to the practice elements of meanings, competences, and objects.

Figure 1. Image from Husmodern (1943) of the different steps to prepare a vegetable mince. Facsimile reproduced with kind permission from Bonnier Tidskrifter.

Figure 2. Image from Husmodern (1943) of an advertisement for meat bouillon. Facsimile reproduced with kind permission from Bonnier Tidskrifter.

Figure 3. Image from Husmodern (1944) of the oxygen tests performed by HFI on someone doing the dishes. Facsimile reproduced with kind permission from Bonnier Tidskrifter.

Figure 4. Image from Husmodern (1958) of an advertisement for washing powder. Facsimile reproduced with kind permission from Bonnier Tidskrifter.

We identified two specific practices situated in kitchens which were central in the data: cooking and doing the dishes. We structured the data according to concerning and agencing and the related overflows for both types of practices, as presented in . Lastly, we mapped out associations between changing kitchen practices and the links with markets and consumption. We then looked for patterns of key actors (organizations, individuals, and objects) featuring in multiple events. Finally, we developed narratives of the practice changes associated with each kitchen concern. These narratives, and the context of them, are presented in the following sections.

Table 1. Overview of the empirical findings.

The context of kitchen concerns in Sweden

Up until the 1930s, Sweden had some of the worst housing conditions in Europe. Cramped conditions and the lack of domestic equipment dominated the political debate (Hofsten and Cornell Citation1946). Kitchens stood at the centre of these concerns. Used for eating and sleeping, the kitchen constituted a crowded and unhygienic general living space (Ohlsson Citation2013). Poor access to equipment made it difficult to cook. A shortage of knives and forks, for example, meant that family members could not all eat at the same time (Husmodern 1943, issue 6). The kitchen became a cornerstone of governmental efforts to promote the Welfare State, with policies designed to raise living standards. However, World War II interrupted this programme, and it was not until in the late 1940s/early 1950s that the “convenient kitchen” became a common feature in Swedish homes (Tellström Citation2015, 45).

We traced changes in Sweden’s Welfare State, as reflected by the magazine Husmodern. Introduced in 1917 during World War I (1914–1918), Husmodern set out to teach “householding” during a time of crisis. It expanded its remit during the 1920s to deal with household economy and the raising of children. In 1944, Husmodern advertised itself thus: “every issue will come in handy, with useful and pleasurable advice.” The magazine sought to educate its female readers, with contributors frequently portrayed as home economics teachers. These teachers worked at The Training School for Home Economics in Uppsala. Established in 1895, the school played a prominent part in debates on the role of women in society and had its own organization for testing products and experimenting with recipes (Lundh Citation1945). Husmodern represented an important outlet for circulating the results of their studies.

From Husmodern’s perspective, the kitchen in Sweden was more than a place of ordinary practices to be maintained, negotiated, and changed through the interaction of multiple actors. Instead, it was a site that reflected contemporary debates about necessary changes in society, with the magazine discussing how the kitchen was supposed to be used, and by whom (Hand and Shove Citation2004). We will next describe how thrifty and convenient practices became enacted by Husmodern through promoting specific interactions between markets and consumption in kitchens.

Findings and analysis: bridging market-consumption boundaries in the kitchen

In order to explore the kitchen as a market-consumption junction, we look into how the boundaries between markets and consumption become negotiated through processes of concerning and subsequently repaired through processes of agencing that enact novel practices. We will first show how thrift is invoked to manage food scarcity in markets, and second how convenience is enacted to manage scarcity of time in consumption. To illustrate this, we trace two specific practices situated in kitchens – cooking and doing the dishes – as they become thrifty and convenient through processes of concerning and agencing ().

Bridging scarcity in food markets: concerning and agencing thrift

Matters of concern may emerge when consumers find it difficult or impossible to access markets. During World War II (1939–1945) Sweden, as a neutral state, stood prepared in a context of political unrest (Huldt Citation2000). It regulated the production and pricing of food by introducing rationing cards to keep demand in check and secure a fair distribution of food for the whole population. For example, sugar, coffee, flour, bread, rice, meat, eggs, and butter were all rationed (Nilstein Citation1946). In response, different institutions in society promoted thrifty consumption, which became related to the housewife seen as embodying the virtue of thrift. A promotional campaign in 1943 stated:

Thriftiness has always belonged to the virtues of the housewife. That’s why she listens with a little smile on her face, when it is said that we now shall save more than ever. She knows that it often relies on her. (Husmodern 1943, issue 10, 5)

Concerning and agencing thrifty cooking

Focusing on the resources used in daily cooking practices, being thrifty was something that the journalists at Husmodern made into a concern for the housewife. Many articles directed attention to the need to save food. As told by a reporter who visited many homes in Sweden: “What especially made me think was how much food is not eaten in our homes. […]. If there were some left-overs one day, I rarely saw them again at the table” (Husmodern 1940, issue 25, 25). The journalist subsequently suggests that one should not waste even a small piece of dry bread and that everything can be put to good use, if only one knows how. Saving food was also connected to making use of available food:

As housewives, we do, indeed, need to save but, even more importantly, we need to make use of every single resource we actually have. Now, if ever, we need to realize how to make root vegetables more appetizing. (Husmodern 1940, issue 1, 6)

Meat was rationed and a rethink of key cooking ingredients was thus required. The magazine provided recipes with instructive images showing the different steps and equipment needed to cook food that looked or tasted like meat. Subsequently, many of the products advertised in the magazine promised to tackle the issue of cooking without meat. Meat bouillon was frequently advertised as a solution to the concerns of meat scarcity ():

How can you get such a delicious meat taste to the soup? Well, get the rich and fine bouillon with Arikos soup extract (without giving up any meat ration cards!). (Husmodern 1943, issue 1, 56)

Another way to accommodate rationed food was to create new meanings around available food. Well-known families were asked how they dealt with the absence of lutfisk, a dried white fish treated with lye, traditionally served at Christmas. Interviewees reported serving another type of fish, cooked with white sauce and pepper. A certain Mrs Oscar Wallinder explained: “See, it’s not the treatment with lye, but rather the pepper in the milk sauce that turns cod into lutfisk” (Husmodern 1943, issue 1, 32). This is also the case in an article advocating the use of onions:

Under normal circumstances, the onion is a lovely thing – and even more so now. It is both a food and a spice. And, perhaps most importantly, it gives the taste sensation of meat. When you eat fried onion and mashed potatoes – yes, then you actually have a feeling of eating a meat dish! (Husmodern 1943, issue 11, 6)

Concerning and agencing thrifty washing up

A number of articles in Husmodern, written by home economics teachers in the 1940s, identified different resources for future rationing and saving. The housewife needed to stay prepared: “Heating and warm water are mere memories; when is it time for gas?” (Husmodern 1940, issue 11, 30). Thriftiness is portrayed as something that should concern all: “If every household were to save wood, gas and electricity, it would mean more than you think for the single household and the national budget” (Husmodern 1940, issue 13, 6). The concern of saving energy became related to the practices of doing the dishes, which afforded opportunities for saving on heated water. The waste of energy was also related to the large amount of crockery being used in Sweden: “It is alleged that we, in Sweden, use eight times more crockery than Germany” (Husmodern 1940, issue 13, 6).

Efforts to agence the housewife subsequently included several recommendations, for example, less crockery should be used when setting the table: “We could do with being less fancy at the dinner table” (Husmodern 1940, issue 13, 6). Also, readers were advised to refrain from using the kitchen sink as normal, but rather to place a small tub in it:

These are lovely, as long as you have a lot of hot water; however, if you need to heat the water on the stove, you would need to heat a lot, only to barely fill the sink. No, get tubs instead! (Husmodern 1940, issue 13, 6)

Overflows from agencing thrifty consumption

The creation of novel practices often led to overflows – generating new elements of practice not previously taken into account (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016). One instance was the emergence of the black market: organizing the illegal exchange of rationed goods. Even though the black market constituted a partial solution to obtain food, it brought with it concerns about food safety. Badgers, known for their tasty and fatty meat, were accessible through the black market; however, badgers often contained the dangerous intestinal worms, Trichinella parasites. In issue 4 of the magazine, Husmodern (1943) argued that black market hunters could not be expected to use governmental inspection facilities to check for Trichinella parasites (the norm in rationed markets). Thus, organizing markets around one concern – the scarcity of food – could generate new concerns: food safety.

Another overflow from agencing thrift was the creation of a concern for the lack of time to perform these new food preparations:

Food has become a troublesome chapter for the housewives. You first have to count and count to get the ration cards to last. And, in order to get what you want, you have to stand in line and waste loads of valuable time. It has become troublesome to think about what to eat. This is the case even in normal circumstances, but how much more time-consuming is it not now! (Husmodern 1943, issue 2, 4)

Bridging scarcity of time in consumption: concerning and agencing convenience

Matters of concern may arise when consumption cannot be performed as it has been previously. During the 1940s–1950s, housewives entering the labour market were increasingly pressed for time. The resulting constraints on consumption were related to a market boundary: a shortage in the labour market of maids. The post-war period of economic growth created employment opportunities that were more attractive than domestic service, leading to “the servant problem” (Hagberg Citation1986). These conditions amplified the need for efficient households, as both housewives and maids started to work elsewhere. Magazine articles frequently discussed ways to rationalize shopping, cooking, and cleaning.

Husmodern often invoked the idea of convenience to encourage fewer chores for the housewife. As stated by Shove (Citation2012), convenience-related consumption is not “simply about saving or shifting time as such, but is instead about re-designing and re-negotiating temporal demands associated with the proper accomplishment of specific social practices” (Citation2012, 300). Convenience got manifested in kitchens through a concern for balancing time scarcity with maintaining the appropriate performance of different practices. Next, we follow the concerns, negotiations, and suggestions to make kitchen work more convenient in relation to cooking and doing the dishes. As we will show, the practices of cooking and doing the dishes became coupled as a nexus, which reconnected the boundaries between markets and consumption to perform convenience in the kitchen. Moreover, we propose that the transformation of practices in the kitchen depended on how the kitchen was envisioned as a new use-environment (Burr Citation2014, 20), dependent on who used it and for what purpose.

Concerning and agencing convenient cooking as entangled with doing the dishes

With both servants and housewives working outside the home, the situation facing many middle-class housewives was a lack of competent others to do the necessary work of buying food, cooking, and cleaning. For a housewife used to servants, this required a rethinking of kitchen size, its equipment, and how kitchen work was organized. For example, one journalist at Husmodern disclosed her concerns over all the large pots normally being used in a large household with a servant. These are presented as inappropriate when switching to a smaller kitchen owing to the lack of servants:

All the pots are too big, also the crockery and especially the serving plates, which are needed for the large household. If you want any comfort in the small household, you immediately have to make some radical changes. (Husmodern 1940, issue 5, 34)

It now becomes an even clearer requirement […] that, to the greatest possible extent, one should avoid moving food from the pot, where it was cooked, to the serving plate, only to later, move the food to a smaller plate where it is stored, if anything is left over – until it is used again and poured into a pot. And then when it is heated, transferred back to a serving plate again. (Husmodern 1940, issue 5, 34)

Advertisements also offered ovenproof goods in different shapes for different purposes. Kitchen equipment from Husqvarna, was advertised to “make the kitchen modern and easy to work in,” promoting a making-soup pot that could be used for both cooking and serving (Husmodern 1940, issue 5, 1). Since Husmodern rarely showed images of food being served at the table, it is difficult to discern whether this principle was common practice. However, an article from 1951 about “happy pots” proclaimed:

Now we cook the food in a deep dish, serve it from the same dish, store it, and heat the left-overs in it. Simple, practical, dish saving. It keeps the aroma, heat, and it is decorative. Everything – thanks to ovenproof goods. (Husmodern 1951, issue 14, 30–31)

Concerning and agencing the convenient kitchen as entangled to new use(r)s

To attain convenience required a new envisioning of the kitchen as a different use-environment (Burr Citation2014). Interpretations of use-environments changed with the redefining of household members’ roles and duties. As described in the booklet The Working Housewife produced by The Society for Rational Householding from 1943 (KF Citation1943), many homes were ill-suited to the needs of working mothers. While families needed a labour-saving and practically furnished kitchen, specific demands depended on how kitchen life was organized: whether only the housewife used the kitchen, whether there was hired help, or whether family members helped and were responsible for kitchen duties. In the latter case: “The kitchen cannot be so small that only one person can work there; there should be room for at least one more, without them being in each other’s way” (KF Citation1943).

The 1943 booklet suggests several ways of responding to the challenges faced by mothers and wives who were employed outside the home. Everything needed for setting the table, it suggested, should be placed so that children could reach it. Advertisements in Husmodern portrayed children helping out at home, doing the dishes or cooking, for example: “Lilly cooks her morning meal by herself – it is always Gyllenhammar’s wonderful oat drink” (Husmodern 1946, issue 2, 48). However, family members were also presented as unreliable helpers. The husband might have time, but not necessarily the competence to do grocery shopping. Meat and fish, highly variable in price and quality, must be bought by the wife; groceries with fixed prices and less variable quality could be left to the husband (KF Citation1943). Instead of sharing the full workload between family members, the straining work of the housewife became associated with the poor organization of the kitchen and a need for better design (Höjer Citation2011).

The kitchen became a concern for a number of women’s organizations. In 1944, the Women’s Social Democrats, Active Householding, and various housewife societies throughout Sweden gathered together, with the financial support of government, to form Hemmens Forskningsinstitut (HFI), i.e. The Research Institute of The Home (Höjer Citation2011). The aim was to improve the quality of life of hard-working housewives. Through ethnographic studies, researchers observed and measured the daily work and movements of women in the kitchen. This concerning work highlighted areas in need of improvement in the design of kitchens, reframing and creating an awareness of kitchen concerns, producing new market solutions for the (un)organized kitchen.

Doing the dishes was made into a central concern by the HFI that tried to discern ways to rationalize the tedious work that was found to take up 15% of household worktime. In commenting on the HFI initiative, Husmodern asked: “Isn’t doing the dishes the most boring of all household work?” (Husmodern 1944, issue 25, 27). Husmodern further reported that, at the institute, they tried to find out how much bodily energy was required when doing the dishes by hand. A photograph in Husmodern shows a woman wearing an oxygen mask to measure the use of energy (). Meanwhile, Miss Skog, a representative from HFI, performed time tests for energy consumption. The test was repeated for different heights of the kitchen sink. This is a clear example of how research practices were carried out to visualize matters of concern. In turn, these understandings of the kitchen as a new use-environment (Burr Citation2014), with different needs and demands, enabled marketers and other concerned actors to influence what went on therein.

In 1953, Husmodern published the results of HFI on “the ideal kitchen set-up,” providing “labour-saving details” for reducing walking, thus saving time: “What new horizons are not opened for the tired and worn-out housewife, who has to run unnecessary miles in unpractical, old kitchens, and bow their backs over too-low sinks” (Husmodern 1953, issue 1, 17). Doing the dishes in a well-organized kitchen takes eight minutes (as opposed to fourteen in a poorly organized one). Practicality is linked to time-saving to promote convenience. The kitchen as a convenient use-environment, in turn, demanded products adapted to new ways of cooking and doing the dishes.

The reinterpretation of food, as a central object in the practice of cooking, played a key role in the transition to convenience. As a solution to the scarcity of time to cook, home economic teachers in Husmodern promoted ready-made tinned food that had become available in the stores again: “The retailers really feed us with canned food […] you could easily say that tinned cans have secured their place in the household” (Husmodern 1950, issue 18, 4).

Frozen foods were proposed as another time-saving solution. A 1953 issue of Husmodern praised the qualities of frozen foods: “One package is equivalent to 450 grams of shrimps and costs 2 kronas, but you get the small animals cleaned and ready, and personally I would then happily pay the price to skip the work” (Husmodern 1953, issue 11, 33). The kitchens of the time, however, were poorly suited for using frozen goods. The article suggests that not having a freezer would mean having to make daily trips to the store, which, combined with the inconvenience of possibly having to travel further to a store with frozen goods, would be detrimental to the overall goal of rationalizing grocery shopping. The article calls for more stores selling frozen goods and frozen storage at home.

As “convenience food” entered the market, kitchen practices gradually gained new meaning by a re-negotiation of what was done and how suitable it was (Shove Citation2012). In an article entitled “Housewife of the Week,” Maria Robhar provided a solution to the problem of having time to cook when hosting a party: “Bring about simpler parties!” She states that the closer her friends were, the simpler her parties became:

I can never learn how to line up coffee, bread, cake, sodas, fruit and bonbons, which are expected at a “simple” Swedish coffee party. If I have any of those to offer, then it will suffice. Undeniably, it is more fun to talk to your friends, than to eat all the time! (Husmodern 1957, issue 2, 8–9)

These observations extend Hand and Shove’s (Citation2004) argument by highlighting how practice transformations come about through processes of interaction between consumption and markets in the kitchen. The generation of concerns related to consumption brought about new market-based solutions, which in turn assigned new meanings to consumption. For example, unorganized kitchens and time pressure demanded new products (frozen and ready-made foods), which, in turn, called for yet new kitchen devices (freezers). The mediating role of the magazine, government finances, and the social movement of housewives came to reshape the relationship between markets and consumption through changing practices. Changes of practices in the kitchen were brought about by a concern for the kitchen as a new use-environment that redirected needs and market demand (Burr Citation2014). And vice versa, the work of integration (introducing new devices for organizing, family members) and separation (the rejection of large pots and exaggerated coffee parties) at the boundaries between markets and consumption also shaped kitchen practices and the role of the housewife.

Overflows with agencing convenient consumption: the “death” of the housewife?

With time, the role and the competence of the housewife changed, along with other social changes and the meanings of what was regarded as appropriate practice. This is apparent when examining the last publications of the Husmodern magazine before its closure in 1988. What happened to the thrifty and competent housewife that made use of the left-overs and looked for ways to do more with less? In 1972, the housewife was still someone who was interested in good recipes based on cheap food, who wanted the luxury of having time to do things by and for herself (Husmodern 1972, issue 1, 5). However, as the well-being of the family and the completion of household chores were no longer reliant on her competence alone, the need for the housewife diminished and, thus, the demand for the magazine Husmodern also collapsed. Others have noted the “death of the housewife” as a matter of fact (Danius Citation2014). However, questions remain over what matters of concern this may lead to and how to best address them.

Discussion

This study has explored practice changes in times of scarcity that redraw the boundaries between markets and consumption in the kitchen. By attending to matters of concern as sources of practice change, we have moved beyond the realignment of practice elements (objects, meanings, and competence) to also include the boundary work involved in efforts to enact novel practices taking those matters of concern into account.

outlines an analytical framework for investigating the interaction between consumption and markets in the kitchen. The kitchen is positioned as a market-consumption junction, being connected to markets and consumption through the generation of needs and demand as well as systems of provision. The link between markets and consumption is thus established through practices in the kitchen, where the boundaries between them are recursively moderated through processes of concerning and agencing, being enveloped by the wider socio-political systems.

In relation to this framework, three inter-related themes need discussing: (1) the situated nature of practice changes at junctions between markets and consumption; (2) how established boundaries between markets and consumption are negotiated through concerning that drives processes of change; (3) how the creation of new boundaries enacts novel practices through agencing; and finally, (4) how potential overflows work to continually redraw the boundaries.

Situating practice changes in junctions between markets and consumption

First, building on the work of Cowan (Citation1987) and others, we introduced the concept of market-consumption junctions. We define the market-consumption junction as a place, space, and time where consumers give meaning to, and make choices about, the objects and competences they use in their everyday practices. In the case of our study, the kitchen as a market-consumption junction constitutes a place where markets and consumption meet through the alignment of different practice elements (Hand and Shove Citation2004), enabling thrifty and convenient practices to emerge and become normalized.

Our analytical framework () positions the kitchen as a site of practices that generate particular consumption needs, which are translated into market demands, for example, food produce, utensils, and energy. We have seen how the practices of cooking and doing the dishes became integrated as a nexus of practices, where market actors picked up the demand for ovenproof goods that could be used for both cooking and serving, thus enabling new agencements of thrift and convenience to emerge. The kitchen is thus a place where consumer needs are generated by the work of integrating bundles of practices in the kitchen with market practices that provide access to the objects required to perform them. These connections are forged through practices in the kitchen (cf. Warde Citation2005). Thus, the market-consumption relationship is neither direct nor obvious. Rather, our study illustrates that changes in demand and supply are not unidirectional and do not come easily, especially when resources are scarce.

In drawing on the work of Hennion, Méadel, and Bowker (Citation1989), we showed how Husmodern professionals remodel the relationship between supply and demand by making visible the multiplication of crossing points between them. Journalists, home economic teachers, and other concerned actors mediated through Husmodern visualized matters of concern and simultaneously introduced ways to address them. This was done by integrating objects, competences, and meanings that both agenced the future consumer (the housewife) as well as the manufacturer. In short, these changes required arduous work to negotiate new boundaries of the assemblages of objects, meanings, and competences amongst multiple concerned actors. This, we argue, is the process by which bridges between market and consumption entities are constituted at the kitchen as a market-consumption junction.

By invoking the concept of market-consumption junction and looking at the concerns that promote changes to the practices performed there, this research goes some way to substantiate Warde’s (Citation2005, 141) claim that “the effect of production on consumption is mediated through a nexus of practices.” In line with Hand and Shove (Citation2004), we acknowledge that the seeds of practice change lie within the mutual adaption between practice elements that, in turn, shape consumption. Nonetheless, by drawing on Arsel and Bean (Citation2013), we also “flip the coin” by arguing that practice changes are mediated through interactions between markets and consumption. We do not, however, see conventions or regimes as primarily an outcome of external developments, but rather propose to see markets and consumption as integral parts of practices in the kitchen. In doing so, we extend the discussion of Hand and Shove (Citation2004) by highlighting how practice transformations come about through processes of interaction between markets and consumption in the kitchen. In short, we suggest that the relationship between markets and consumption is shaped by the practices in the kitchen, and, at the same time, the continuous work of integration and separation at the boundaries between markets and consumption shapes the practices in the kitchen.

Concerning boundaries between markets and consumption

We argue that the notion of concerning helps to explain the changing relationships between markets and consumption through a variety of means (). For example, concerns about food waste may emerge from pressure groups, media outlets, or the government. This highlights how kitchen encounters are enveloped by the broader socio-political systems where changes in the security of resources and rationing come to change user-environments. In this way, the context of our study resembles that of Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017), dealing with practice disruptions due to resource scarcity. However, Phipps and Ozanne (Citation2017) concern themselves primarily with challenges within different ontological states of security associated with scarce resources. By bringing in the notion of concerning, we provide an alternative theoretical frame to help explain the mechanisms involved in the transitions between different states of ontology: from concerns for scarce market resources to thrifty and gradually convenient consumption. Similarly, whereas Arsel and Bean (Citation2013) show how disparate practice constituents are brought together through a discursively constructed taste regime (which then orchestrates objects, doings, and meanings to produce new practices), we show the mechanisms – specifically the concerning work of Husmodern and other actors represented in its pages – involved in gradual movements between different stages in a change process. We do this by revealing the boundary work (cf. Gieryn Citation1983) where multiple actors become allied to raise awareness around concerns in order to imagine, conceptualize, and put the new regimes of thrift and convenience into place.

Concerning processes thereby direct attention to the ongoing efforts of rebuilding the teleoaffective structures of a practice (cf. Schatzki Citation1996, Citation2012). This way, concerning enables an understanding of the process of problematization that take place at a societal level as well as in the daily practices (cf. Arsel and Bean Citation2013). Thus, the notion of concerning shows how concerned actors attempt to render issues at the boundaries between markets and consumption problematic and visible which, in turn, reframe what is excluded or included in kitchen practices. Moreover, our study illustrates how efforts to make matters of concern visible are tightly coupled to efforts to address those concerns through processes of agencing, which we discuss next.

Agencing bridges between markets and consumption

The notion of agencing (cf. Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016) constitutes the other side of the coin (): multiple actors work to bridge the boundaries between markets and consumption by reconfiguring practices in the kitchen. We reveal the boundary work done through observation, reporting, and representation of kitchen practices as use-environments change, become politicized, and later reformed and performed through multiple actors in socio-political systems. Attempts at agencing particular types of practices can be initiated by any of these systems. Market actors may try to influence kitchen practices by introducing new objects, new meanings to existing practices, or spur the emergence of novel practices (see Truninger Citation2011). Indeed, we have seen how researchers, kitchen designers and home economists may introduce new ideas regarding what practices should be conducted in kitchens and how novel spatial arrangements and artefacts may facilitate the introduction of these practices. However, no one actor (human or non-human) determines the re-configuring process on its own. Rather, new configurations in the kitchen emerge from the powerful associations being made between new assemblages of actants. Such agencements (cf. Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016) become generated in the kitchen by reconfiguring and agencing the market-consumption junction, and this necessarily includes both market and consumption actions. Put together, the interactions between markets and consumption take place through processes of concerning and agencing, which under the influence of socio-political systems, work to accomplish practice change. Moreover, we suggest that the recursive relationship between concerning and agencing need to be understood in light of the unintended consequences and overflows that reoccur in response to these efforts.

Concerning, agencing, and overflows as continually redrawing boundaries

A historical perspective on consumer cultures reveals a continuous redefinition of boundaries to cope with either a scarcity or abundance of resources (Czarniawska and Löfgren Citation2013). Our longitudinal analysis thus emphasizes the dynamic nature of such boundary work that is only ever temporarily stabilized. Our key argument is that the alignment between the two sides of is never achieved in full or necessarily stable for too long. This is because the creation of novel practices leads to overflows elsewhere, for example, black markets, time pressures, and the degrading of cooking competences, which may spur new matters of concern. This necessitates a reframing of boundaries (cf. Czarniawska and Löfgren Citation2013; Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016) that prevent the reproduction of extant practices, while opening up new possibilities for others.

By acknowledging the potential unintended consequences stemming from this boundary work, we are able to further the understanding of the ongoing transitions between concerning and agencing as driving the overall development of practices. Thus, concerning, agencing and overflows continually work to reinforce new boundaries and definitions of markets and consumption, and enable novel practices to emerge. This view is important as it extends our understanding of how practices develop beyond mundane processes (cf. Arsel and Bean Citation2013), to times and situations of a scarcity of resources (cf. Czarniawska and Löfgren Citation2013; Phipps and Ozanne Citation2017) that can explain where regime changes come from and how they come about and are put into practice.

Thus, we suggest that the two processes of concerning and agencing need to be studied in tandem and as propelled by unintended overflows, while being situated in the broader systems within which these practices take place. We claim that it is in this recursive process that new assemblages of practice elements are introduced and adapted in the kitchen. This in turn generates new forms of consumption and consumer demand, while transforming markets. In this regard, markets and forms of consumption are recognized as dynamic and always in the making.

Conclusions and implications

Through this paper, we have provided insights into the spaces and mechanisms involved in practice changes at the boundary between markets and consumption. We offer a situated perspective of practice change in a market-consumption junction – the kitchen – where the relationship between markets and consumption mutually become shaped by, and shape practices in the kitchen. We suggest that the processes of concerning and agencing in conjunction to potential overflows constitute the mechanisms involved in driving these changes. As matters of concern arise through processes of concerning, the boundaries between markets and consumption are rendered problematic and thus visible. In turn, processes of agencing work to link them together again in novel ways – only until new matters of concern become surfaced again due to overflows stemming from the agencing efforts. These observations make two key contributions to our understanding of the dynamics of practices in markets and consumption.

First, building on the work of Mallard (Citation2016), we show the significance of public matters of concern and, by implication, the work of concerning. Our claim is that understanding the processes of concerning, and the work done to make people concerned, is a pre-requisite for understanding agencing actions and moments of transformation. This perspective goes beyond the rearrangement of practice elements as the seeds of change (Hand and Shove Citation2004; Arsel and Bean Citation2013) by illuminating the multi-actor work involved in the interplay between concerning, agencing and overflows that continuously redraw the boundaries between markets and consumption. This helps us to understand the tensions between continuity and change in markets and consumption, and the difficulties that actors face in both stabilizing and/or disrupting and transforming them (Kjellberg, Azimont, and Reid Citation2015).

As an implication of acknowledging the work that goes into concerning, we can better understand efforts to transform what markets offer, how these offerings and market objects are valued, and by whom. In turn, this also creates opportunities for new market offerings. We thus suggest that managers should see concerning and agencing as integral parts of marketing work. Managers can anticipate the emergence of barriers to the continued performance of extant practices by identifying new objects, ideas, or meanings (including matters of public concern) to disrupt how practices are performed.

Second, the notion of market-consumption junctions (cf. Cowan Citation1987) illustrates how a “market-widening” perspective can be enacted in a situated study of markets and consumption in use-environments (Burr Citation2014). While consumption is commonly defined as taking place in both exchange situations and moments of usage (Warde Citation2005), markets are confined to exchange situations. By explicating market practices in relation to consumption in a particular market-consumption junction, we follow Burr (Citation2014) in extending the boundaries of constructivist market studies by providing a concept and context for studying how market demand is created in specific use-environments. Conversely, using the notion of market-consumption junction and the associated boundary work taking place therein can also enable a deeper understanding of how boundaries of consumption become established in relation to markets and socio-political systems.

By implication, market-consumption junctions works to “flatten” (Bajde Citation2013) markets and consumption, which enables new agencies to be made visible in the use-environment. As shown through our study, transitions to thrifty and convenient practices were mediated by markets being framed within wider socio-political systems (cf. Theien Citation2009). Allied through concerns about the scarcities in food markets and consumption, multiple actors worked to shape practices that enabled a redrawing of the boundaries of markets and consumption to create societal well-being. In a similar fashion, further studies of other market-consumption junctions could reveal the dynamic, porous, and contentious nature of concerns at the boundaries between markets and consumption. For example, matters of concern related to how to cope with overflows in the form of excess (Czarniawska and Löfgren Citation2013), such as food waste, have now entered the public agenda. The density and complexity that a market-consumption junction reveals, generates valuable insights for those seeking to influence market-consumption action in a marketized society concerned with social and environmental constraints (Latour Citation2004). The politics and sociologies of market-consumption interactions seem likely to generate important insights into the creations of ideologies and socio-economic organizational designs that generate the boundaries for “good” markets and consumption, regardless of how we choose to define them for contemporary societies.

Acknowledgements

This paper was developed as part of two subsequent workshops at Lancaster University and the Stockholm School of Economics, which were attended by colleagues from these two institutions, as well as the Universities of Edinburgh, Leicester and Manchester. Draft versions of the paper were also presented at research seminars arranged by Måltidsakademien at Uppsala University as well as Mistra Center for Sustainable Markets at Stockholm School of Economics. We are grateful to participants at these workshops and seminars for their constructive comments and suggestions. We also acknowledge the valuable comments and critique received from three anonymous reviewers as well as the editors of this special issue. All remaining errors and omissions are ours alone. Finally, we wish to thank Bonnier Tidskrifter for kindly permitting us to reproduce facsimiles from the Husmodern magazine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Ingrid Stigzelius is a post-doc researcher and lecturer at Mistra Center for Sustainable Markets (Misum), Department of Marketing and Strategy, Stockholm School of Economics (SSE). Her primary research interest lies at the intersection of markets and consumption and how various socio-material practices work to produce green, political consumers as well as a more sustainable business and society. Her previous work has appeared in Scandinavian Journal of Management and the edited volume Concerned Markets: Economic Ordering for Multiple Values.

Luis Araujo is Professor of Marketing and Strategy at Alliance Manchester Business School, University of Manchester. His research is related to business marketing and purchasing as well as the relation between markets and marketing. His work has appeared in a number of international journals in marketing and management studies.

Katy Mason is a Professor of Markets, Marketing and Management at Lancaster University, UK. Katy's research focuses on understanding how managers make and shape markets, the market devices they use to enrol others and create new market boundaries. Her current work looks at the materials and practices of market makers, as they work out what to do next. Her work covers a number of contrasting market contexts, from engineering, healthcare, bioscience and bottom of the pyramid markets. Katy's work has been published in Journal Management Studies, Industrial Marketing Management, Long Range Planning, Journal of Business Research, Marketing Theory and Journal of Marketing Management.

Teea Palo is a lecturer at Lancaster University Management School, Department of Marketing. She is interested in the work of actors in constructing, organising and changing markets, and in particular the devices and practices of such work. Ranging from the narrative nature of business models to myths as market organising devices, her work explores ways in which actors develop, circulate and share stories of imagined markets, and how such stories are translated into market practices. She gained her doctoral degree in marketing at Oulu Business School, Finland.

Riikka Murto is a PhD student at the Center for Market Studies, Stockholm School of Economics. She is interested in the role of marketing in shaping markets and society. Her dissertation research examines the use of gender and other social categories in marketing and digital product development.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, Andrew. 1995. “Things of Boundaries.” Social Research 62 (4): 857–882.

- Alderson, Wroe. 1965. Dynamic Marketing Behavior: A Functionalist Theory of Marketing. New York: RD Irwin.

- Araujo, Luis, and Hans Kjellberg. 2009. “Shaping Exchanges, Performing Markets: The Study of Marketing Practices.” In The SAGE Handbook of Marketing Theory, edited by Maclaran, Pauline, Michael Saren, Barbara Stern, and Mark Tadajewski, 195–218. London: Sage.

- Araujo, Luis, and Hans Kjellberg. 2016. “Enacting Novel Agencements: The Case of Frequent Flyer Schemes in the US Airline Industry (1981–1991).” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (1): 92–110. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1096095

- Arnould, Eric J., and Craig J. Thompson. 2005. “Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (4): 868–882. doi: 10.1086/426626

- Arsel, Zeynep, and Jonathan Bean. 2013. “Taste Regimes and Market-Mediated Practice.” Journal of Consumer Research 39: 899–917. doi: 10.1086/666595

- Bajde, Domen. 2013. “Consumer Culture Theory (Re)Visits Actor-Network Theory: Flattening Consumption Studies.” Marketing Theory 13 (2): 227–242. doi: 10.1177/1470593113477887

- Burr, Thomas Cameron. 2014. “Market-widening: Shaping Total Market Demand for French and American Bicycles Circa 1890.” Marketing Theory 14 (1): 19–34. doi: 10.1177/1470593113497741

- Calder, Lendol. 2012. “Saving and Spending.” In The Oxford Handbook of The History of Consumption, edited by Frank Trentmann, 348–375. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. 2010. “Economization, Part 2: A Research Programme for the Study of Markets.” Economy and Society 39 (1): 1–32. doi: 10.1080/03085140903424519

- Callon, Michel, ed. 1998. The Laws of the Markets. Oxford: Blackwell /The Sociological Review.

- Callon, Michel. 2007. “An Essay on the Growing Contribution of Economic Markets to the Proliferation of the Social.” Theory, Culture & Society 24 (7–8): 139–163. doi: 10.1177/0263276407084701

- Callon, Michel. 2008. “Economic Markets and the Rise of Interactive Agencements: From Prosthetic Agencies to Habilitated Agencies.” In Living in a Material World. Economic Sociology Meets Science and Technology Studies, edited by Trevor Pinch and Swedberg Richard, 29–56. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Callon, Michel. 2010. “Performativity, Misfires and Politics.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2): 163–169. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2010.494119

- Callon, Michel, Pierre Lascoumes, and Yannick Barthe. 2009. Acting in an Uncertain World. An Essay on Technological Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chelekis, Jessica Andrea, and Bernardo Figueiredo. 2015. “Regions and Archipelagos of Consumer Culture: A Reflexive Approach to Analytical Scales and Boundaries.” Marketing Theory 15 (3): 321–345. doi: 10.1177/1470593115569102

- Cochoy, Franck. 2010. “Reconnecting Marketing to ‘Market-Things’: How Grocery Equipment Drove Modern Consumption (Progressive Grocer, 1929–1959).” In Reconnecting Markets to Marketing, edited by Luis Araujo, Finch John, and Kjellberg Hans, 29–49. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cochoy, Franck, and Sophie Dubuisson-Quellier. 2013. “The Sociology of Market Work.” Economic Sociology – The European Electronic Newsletter 15 (1): 4–11.

- Cochoy, Franck, Pascale Trompette, and Luis Araujo. 2016. “From Market Agencements to Market Agencing: An Introduction.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (1): 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1096066

- Conran, Terence. 1977. The Kitchen Book. London: Mitchell Beazley.

- Cowan, Ruth S. 1987. “The Consumption Junction: A Proposal for a Research Strategy in the Sociology of Technology.” In The Social Construction of Technological Systems, edited by Wiebe Bijker, Thomas P. Hughes, and Trevor Pinch, 261–280. London: MIT Press.

- Czarniawska, Barbara, and Orvar Löfgren, eds. 2013. Coping with Excess: How Organizations, Communities and Individuals Manage Overflows. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Danius, Sara. 2014. Husmoderns död och andra texter. Stockholm: Bonnier.

- D’Antone, Simona, and Robert Spencer. 2015. “Organising for Sustainable Palm Oil Consumption: A Market-based Approach.” Consumption Markets & Culture 18 (1): 55–71. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2014.899217

- de la Bellacasa, Maria P. 2011. “Matters of Care in Technoscience: Assembling Neglected Things.” Social Studies of Science 41 (1): 85–106. doi: 10.1177/0306312710380301

- De Wit, Onno, Jan van den Ende, Johan Schot, and Ellen van Oost. 2002. “Innovative Junctions: Office Technologies in the Netherlands, 1880–1980.” Technology and Culture 43 (1): 50–72. doi: 10.1353/tech.2002.0012

- Dolbec, Pierre-Yann, and Eileen Fischer. 2015. “Refashioning a Field? Connected Consumers and Institutional Dynamics in Markets.” Journal of Consumer Research 41 (6): 1447–1468. doi: 10.1086/680671

- Dubuisson-Quellier, Sophie. 2013. “A Market Mediation Strategy: How Social Movements Seek to Change Firms’ Practices by Promoting New Principles of Product Valuation.” Organization Studies 34 (5–6): 683–703. doi: 10.1177/0170840613479227

- Evans, David. 2011. “Thrifty, Green or Frugal: Reflections on Sustainable Consumption in a Changing Economic Climate.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 42: 550–557.

- Floyd, Janet. 2004. “Coming Out of the Kitchen: Texts, Contexts and Debates.” Cultural Geographies 11 (1): 61–73. doi: 10.1191/1474474003eu293oa

- Geiger, Susi, Debbie Harrison, Hans Kjellberg, and Alexandre Mallard, eds. 2014. Concerned Markets: Economic Ordering for Multiple Values. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Gieryn, Thomas F. 1983. “Boundary-work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists.” American Sociological Review 48 (6): 781–795. doi: 10.2307/2095325

- Hagberg, Jan-Erik. 1986. “Tekniken i Kvinnornas Händer: Hushållsarbete och Hushållsteknik under Tjugo- och Trettiotalen.” Diss. Linköping: Malmö University.

- Hagberg, Johan. 2015. “Agencing Practices: A Historical Exploration of Shopping Bags.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (1): 111–132. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1067200

- Hand, Martin, and Elisabeth Shove. 2004. “Orchestrating Concepts: Kitchen Dynamics and Regime Change in Good Housekeeping and Ideal Home, 1922–2002.” Home Cultures 1 (3): 235–256. doi: 10.2752/174063104778053464

- Hennion, Antoine, Cécile Méadel, and Geofrey Bowker. 1989. “The Artisans of Desire: The Mediation of Advertising Between Product and Consumer.” Sociological Theory 7 (2): 191–209. doi: 10.2307/201895

- Hofsten, Erland, and Jan Cornell, eds. 1946. När Var Hur: aktuell uppslagsbok. Stockholm: Åhlén & Åkerlunds Boktryckeri.

- Höjer, Henrik. 2011. “Hemmens forskningsinstitut.” Framsteg & Forskning 9, October 31. http://fof.se/tidning/2011/9/hemmens-forskningsinstitut.

- Huldt, Bo. 2000. “Sverige Åter i Europa.” In Sverige 1900-talet, Nationalencyklopedin, edited by Båge Susan, 82–87. Höganäs: Bra böcker.

- Humphreys, Ashlee. 2010. “Semiotic Structure and the Legitimation of Consumption Practices: The Case of Casino Gambling.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (3): 490–510. doi: 10.1086/652464