ABSTRACT

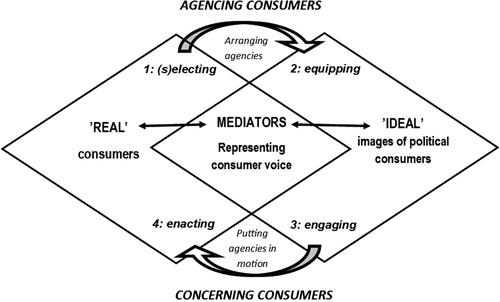

This paper explores the consumer role in marketplace transformation by examining how political consumers become produced in food retailing. It attends to situated representational practices in a Swedish consumer cooperative that seeks to strengthen consumer voice in markets. Combining notions of political and symbolic representations, the paper demonstrates the production of spokespersons for the cooperatives’ owners who, in turn, work to engage other consumers to voice and enact concerns in the cooperative. Four stages of representational practices are identified: (s)electing, equipping, engaging, and enacting. These practices are conceptualised as part of processes of agencing and concerning: (s)electing and equipping work to arrange consumer agencies, while engaging and enacting refer to ways of concerning others that put agencies into motion. Agencies are proposed as liquid in character and the capacity of consumers to shape markets comes into effect depending upon how agencies continuously become connected to each other.

Introduction

Retail markets are often the subject, as well as the producer, of political debates. A wide range of concerned actors – such as regulators, market professionals, consumers, and civil society organisations – come to shape marketplaces in response to various “matters of concern” (Latour Citation2004a; Geiger et al. Citation2014; Mallard Citation2016). For example, sustainability, which is a major societal concern today, is challenging for retailers who must strike a delicate balance between responding to consumer and societal pressure, while not limiting their business interests (Lehner Citation2015). In retail transformation, a complex integration between politics, market economy, and consumer cultures thus takes place, which involves the influence of multiple actors (Du Gay Citation2004; Freathy and Thomas Citation2015).

In particular, consumers are often depicted as endowed with political power to change retail markets. The so-called political consumer has been portrayed in the literature as being an active agent that directs the market through acts of boycotting or “buycotting” products, whereby consumers primarily express their concerns through their purchases (Micheletti Citation2003; Micheletti and Isenhour Citation2010; Stolle and Micheletti Citation2013). Other studies pertaining to cultural and symbolic dimensions also reveal that consumers play an active and more direct role in the formation and shaping of markets: for example, by co-creating value (e.g. Cova, Dalli, and Zwick Citation2011; Peñaloza and Mish Citation2011), by extending market offers (Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013; Martin and Schouten Citation2014), or by opposing dominant markets (e.g. Kozinets Citation2002; Thompson and Coskuner-Balli Citation2007; Giesler Citation2008). Moreover, being politically engaged through formal consumer associations has recently been put forward as an under researched way for consumers to expand and modify existing market logics from within markets (Kjeldgaard et al. Citation2016).

In the continuous work of integration between politics, economy, and consumption, however, it is not only markets that various actors transform; the very actors involved in this process also become reconfigured (Du Gay Citation2004; Cochoy Citation2008; Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2010). For example, Du Gay (Citation2004) showcased in a historical study of retail transformation to self-service, the way in which particular consumer subjects – the self-served retail consumer – became created. As du Gay argues, retail research tends to take as a given the building of consumer capacities in retail transformations. More recently, Harrison and Kjellberg (Citation2016) also noted that consumers are generally assumed as being active already at the outset of studies, which leaves out many other possible actor configurations of consumers in markets.

Building upon these insights, I argue that research on the political consumer in retailing still often departs from the image of consumers as politically active, while little is revealed of how political consumers in retail transformations become produced. This potentially underestimates the different capacities through which consumers engage in the shaping of markets (Harrison and Kjellberg Citation2016). How then, do political consumers become produced in retailing? And, how can such political consumers become enacted to voice their concerns in retail transformations?

Focusing upon the production of the political consumer, this research aims to explore how consumer voice to influence retail transformation becomes constructed. In doing so, I examine the relationship between consumption and the political from a different angle than that of traditional retailing to trace the “tools of democracy” (Asdal Citation2008) within markets: namely, a classical system of political representation and how it becomes organised within a consumer cooperative. Although cooperatives are not representative for the larger retail sector, they nevertheless provide an important outlet for understanding the different tools and capabilities of consumers to become politically active in retail markets (cf. Kjeldgaard et al. Citation2016).

The paper builds upon a case of a cooperative food retailer in Sweden that recently went through several changes in their relationship to their affiliated consumer associations. The retailer struggles with strengthening their effectiveness and competitiveness on the market; thus, it decides to separate the business unit from the consumer associations. Meanwhile, member engagement in the consumer associations is fading. In an effort to strengthen the link between its members and the business operations, the consumer associations have introduced in the local stores what are known as “owner representatives.” These changes could potentially enable the cooperative retailer to manage the delicate balance between being permeable to the multiple consumer voices in the associations, while also efficiently managing their competitive edge in the market.

I develop a conceptual lens drawn from constructivist market studies in order to explore the production of political consumers through the introduction of owner representatives. From this perspective, consumers are seen as the result of situated market practices that effectuate different modes of engagement in markets (Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2010; Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010; Reijonen Citation2011). Moreover, Fuentes (Citation2015) has noted how images of responsible consumers used in marketing practices act as configuring agents that organise retailing activities and marketing to consumers. By focusing upon the import of representations in market practice (Diaz Ruiz Citation2013; Fuentes Citation2014, Citation2015; Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2015), this research investigates how consumer representations – both in the form of political representatives and consumer images – become arranged in market practices and how they work to enact political consumers. In doing so, I neither regard consumers as being empowered nor disempowered by default; rather, I investigate the processes in which political consumers come into being. In order to follow the production of representations, I have adopted an “exploded view on representation” (Lynch Citation1994) where, through participant observation, I follow the production of political representatives and consumer representations (cf. Stern Citation1998; Cayla and Peñaloza Citation2006).

The empirical study illustrates how the consumer cooperative works to produce politically elected owner representatives; it also shows how the cooperative in this process is both driven by, and work to produce, idealistic images of the politically active consumer. The arranging of these representations is further conceptualised through the notions of agencing (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016; Hagberg Citation2016) and concerning (Latour Citation2004a; Geiger et al. Citation2014; Mallard Citation2016). An analytical framework outlines how agencing of consumers works to arrange representatives through practices of (s)electing and equipping that seeks to bring the “real” consumer closer to the “ideal” image of the political consumer. The resulting political representatives then work to concern others in practices of engaging and enacting, thus, working to bring the idealistic consumer image closer to a reality. It is suggested that these practices, together, work to produce politically active consumers. Nevertheless, agencies linked to the political consumer are proposed as multiple and liquid in character. Therefore, agencies need to be continually reconnected and appear as one voice throughout the consumer cooperative in order to have an effect.

The paper is structured in the following way: after this introduction, previous literature on the role of consumers in market formation is reviewed. I then present an overview of the theoretical framework, which describes how different consumer representations become arranged through the agencing and concerning of consumers. The method used to empirically study and analyse the making of political consumers is thereafter described. The case at hand is then presented in relation to its context. A more detailed account and analysis of the case is subsequently developed, which is followed by a discussion on different identified themes that work to represent the role of the politically active consumer in marketplace transformation.

Consumer voice in market formation

The consumer has thus far been presented in the literature with different capacities to express their political concerns in markets. I follow Hirschman’s (Citation1970) classic categorisation of different means to voice concerns in order to better understand the literature according to whether exit, voice, and/or loyalty is called upon as a strategy to influence market formation. Hirschman (Citation1970) describes exit and voice as two strategies that influence an organisation, which is affected by the degree of loyalty to the organisation. The basic principle is simple: either one feels obliged to voice one’s concerns or silently leaves to mark one’s dissent. Using exit as a strategy formally belongs to the economic arena and market mechanisms; however, voice is grounded in the political sphere and democratic mechanisms to achieve change. Combining voice and exit can, for example, become an expression of loyalty or care for an organisation, even if one decides to leave. Regardless of which strategy one chooses, the question essentially becomes whether one chooses to change from within or from outside the organisation or market.

In research on political consumption, consumers are shown to use markets for political purposes and, thereby, seek to achieve change in retail companies (Micheletti Citation2003; Micheletti and Isenhour Citation2010; Stolle and Micheletti Citation2013). Political consumerism is here defined as: “conscious consumer use of the market as an arena for politics” (Micheletti and Isenhour Citation2010, 133). As Boström and Klintman (Citation2009) state, political consumers are viewed as being active and critical, using their free will to make informed choices on the market with the aid of labels and promotion of diversified niche markets. Consumers influence markets through their purchases and, therefore, “vote with their pennies” by boycotting socially and environmentally harmful products and “buycotting”: for example, eco-labelled products. In this approach, individuals express their political beliefs through consumption choices, implying that any purchase actually could become political. In turn, this reveals how political consumption in this vein builds upon the market mechanisms of exit as a strategy: where consumers silently speak indirectly through the generated purchase data. Exit, on the other hand, leaves the consumer with few other opportunities to raise concerns and to directly engage in the shaping of markets towards alternative ends.

This assertion is in line with another strand of research on political consumerism that is sceptical of consumer demand’s ability to foster changes in markets (Micheletti and Isenhour Citation2010). Instead, this research suggests that lifestyle changes in combination with government support would be the prime drivers for achieving change in markets. Moreover, practice research on political consumption is in line with this argument where domestic everyday practices are seen to shape how consumption is performed both as usage and as purchase (Warde Citation2005; Halkier Citation2010). By focusing upon the consumers’ everyday dealing with challenged consumption areas – such as food – it is possible to reveal how consumer agency become unfolded as part of the complexities of everyday life (Halkier Citation2010).

The political consumption literature, however, strangely omits the possibility to make consumption political by introducing democratic and collective action through political representation. Although the notion of “individualized collective action” (Micheletti Citation2003) implicitly assumes a collective as consisting of aggregated individual action, there is no formally organised collective that can speak up on behalf of the individuals. Conversely, additional perspectives to the field of political consumption have looked at how civil society organisations act on behalf of the individual through “collectivized individual action” (Holzer Citation2006). From this perspective, formal organisations work to recruit individual consumers to build up support for political purposes, which later can be used to put pressure upon companies to act more responsibly (Balsiger Citation2010; Dubuisson-Quellier Citation2015). Consumers give their consent by primarily paying charity to an increasing number of civil society organisations working for different political purposes on behalf of individuals (Papakostas Citation2012). However, individuals often do so without receiving in return any formal membership in the organisation, which forms the base for the control of leadership in the organisation (Einarsson and Hvenmark Citation2012). In this way, individual citizens have become consumers of politics rather than active producers of it.

Meanwhile, the consumer has been portrayed as active and influential on the market in the disperse field of studies in connection to Consumer Culture Theory. In one strand of research the consumer is seen to voice their concerns by actively opposing mainstream markets altogether, rather than using them for political purposes. Instead, consumers seek to resist or reject markets that, in turn, lead to new market formations (e.g. Kozinets Citation2002; Thompson and Coskuner-Balli Citation2007; Giesler Citation2008). However, consumers are still reliant upon market mechanisms for achieving change, which easily becomes co-opted by corporations (Thompson and Coskuner-Balli Citation2007).

Another line of research in CCT looks at how consumers engage to change markets from within with a higher degree of loyalty to the established markets: for example, by entrepreneurially or collectively working to modify and co-create the meanings, values, and supplies of products and services (Peñaloza and Mish Citation2011; Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013; Martin and Schouten Citation2014; Kjeldgaard et al. Citation2016). Herein, consumers work to achieve change by actively modifying the available market offers. Thus, earlier research tends to primarily rely upon market mechanisms to achieve change; however, as Kjeldgaard et al. (Citation2016) explains, these studies have largely neglected to explore the formally organised activities of consumers in markets. Thereby, the alternative, democratic mechanisms in shaping markets has been relatively under researched.

As Kjeldgaard et al. (Citation2016) show in their study of the Danish beer market, this overlooked area of exploration holds the potential to capture the market dynamics that emerges from formalised consumer activities. The consumers’ collective action is portrayed here in a story of success: as a means to influence the market’s technological and legislative dimensions (Kjeldgaard et al. Citation2016). Little is revealed in this study, however, of how the members of the consumer collective became active, and what it was that worked to strengthen the consumer voice in markets. As Harrison and Kjellberg (Citation2016) noted, there is a general tendency to assume that active consumers already exist at the outset of research, which potentially neglects many other actor configurations of consumers in markets.

Hence, combining the need for further studies on consumers’ formal organisation with the need to study how they acquire a capacity to act within this alternative mode of exchange, I set out to study the processes of how consumers become produced as politically active through membership in formal consumer associations. To do so, I will employ a different conceptual lens as drawn from the field of constructivist market studies.

Representing the political consumer in market practices

Markets constitute a place and space where different actors meet to negotiate various matters of concerns (Latour Citation2004a; Geiger et al. Citation2014). Markets are thus often the subject, as well as the producer, of political controversies (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010). Kjellberg and Helgesson (Citation2010, 282) draw upon Thévenot (Citation2002) by suggesting that the political is something that takes place in ongoing negotiations and conflicts concerning what is considered “good” and what is considered “real.” A perceived disconnect between these two positions – for example, something “good” is not “real” or something “real” is not “good” – leads to various concerns that fuel political debates (Geiger et al. Citation2014; Kjellberg and Stigzelius Citation2014). The concept of engaging (Thévenot Citation2002, 54) can be used to describe “an attempt by an agency to link what is ‘good’ with what is ‘real’” (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010, 282). By engaging, then, actors seek to realise specific values. Engagements, however, often give rise to political controversies since other actors do not necessarily share those values. This way, engaging to do “good” becomes part of the active production of the social world, since “while the ‘real’ is indeed ‘real’, it is also made” (Law and Urry Citation2004, 395).

Moreover, following Barry (Citation2002) I more specifically define the political as being different from politics: where politics refer to the “set of technical practices, forms of knowledge, and institutions,” the political is “an index of the space of disagreement” (Barry Citation2002, 270). Something is political, then, depending upon the degree to which it opens up the possibility for disagreement. In turn, politics become a frame or set of tools for reaching an agreement, for example, as in democratic elections. Similar to Asdal (Citation2008), I am, however, not that interested in what politics and democracy is in principle; rather, I seek to explore how it is carried out in practice.

From a market practice perspective, the political should not be confined to a separate process that takes place in parallel to the market exchanges; it should be seen instead as part of the ordinary practices that occur in markets (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010). Moreover, the question of which concerned actors and voices are called upon to take part in market negotiations becomes a political one, drawing attention to how democracy is enacted in markets. Following the democratic tools and devices of politics in market practices may be a way of understanding how consumers gain a capacity to act politically: being able to disagree on matters of concern and make their voices heard to promote particular values. Thus, by attending to the political dimension in market practices it is not only possible to attend to the negotiations of what is “good” to pursue, one can also look at the processes and tools that engage critical others as an input to realise those “goods” (cf. Neyland and Simakova Citation2010).

By organising and shaping exchanges in accordance to specific values or concerns (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010; Geiger et al. Citation2014) markets can take on multiple forms (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2006). Meanwhile, in the process of organising markets, market practitioners also become configured into different agential variations (Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2010). This opens up the possibility for multiple actor constellations, not the least involving consumers, to more or less directly engage in the shaping of how markets are organised (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010; Harrison and Kjellberg Citation2016). Hence, consumers should be seen from this perspective as results of situated market practices that effectuate different forms of engagement in markets (Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2010; Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010; Reijonen Citation2011). In this regard, I view political actors aiming to change markets as being integrated in, and a consequence of, market practices rather than being an external force of an assumed already active political consumer or consumer movement (cf. Balsiger Citation2010; Micheletti and Isenhour Citation2010). By not assuming any pre-determined hierarchies between different market actors, this provides a way to “flatten” markets and consumers that enable them become more on par with each other at the outset of studies (Latour Citation2005; Bajde Citation2013).

According to Kjellberg and Helgesson (Citation2007), market practices can be divided into three inter-linked practices: exchange practices, normalisation practices, and representational practices, which work in different ways to constitute markets and the actors therein. For example, representations or images of markets appear to play a role in not only depicting markets, but also working in realising them (e.g. Diaz Ruiz Citation2013; Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2015). Similarly, the production of consumer images also works to enact consumer identities as well as marketing practices (see e.g. Cayla and Peñaloza Citation2006; Fuentes Citation2014).

By focusing upon representational practices, Hagberg and Kjellberg (Citation2015) further suggest that these can be separated into two different spheres: the political practices, which effectuate that one person can act or speak on behalf of a group, as well as the linguistic and symbolic practices in how we refer or depict different things or ideas that, in turn, help to enact them. Building upon these two dimensions, Hagberg and Kjellberg (Citation2015) define representation as “any arrangement that allows one entity to speak or act on behalf of another” (Callon Citation1986; Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2015, 183).

Moreover, the role of representations could be related to the political sphere (Barry Citation2002): both in terms of the politics, such as in democratically elected representatives in parliament, as well as in relation to the political and the distinction between what is represented as “good” and what is “real” (Thévenot Citation2002). Representations can, therefore, come into play in politics through the portrayed images of idealistic states of the world: where actors become engaged to make these images a reality. These perspectives offer opportunities to rethink how consumer representations become arranged in market practices (cf. Fuentes Citation2015) – both in terms of political as well as symbolic representations – and how these representations either help or obstruct political consumers to come into being. Next, I will develop a conceptual lens that allows me to examine the arranging of consumer representations in market practices.

Arranging representations through agencing and concerning consumers

One way of overcoming the problem of defining consumers as being active at the outset of the study is by focusing upon the construction of agencement in consumption (Callon Citation2007; Çalışkan and Callon Citation2010, Citation2008; D’Antone and Spencer Citation2015). This perspective also includes a move from the individual agency of consumers to the complex socio-material assemblages that configure consumption. According to Callon (Citation2007), agencements are “arrangements endowed with the capacity of acting in different ways depending on their configuration” (Callon Citation2007, 320). In turn, various socio-material elements constitute the configuration of actors; these include equipment, tools, and material devices that work to change the course of action (Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008; MacKenzie Citation2009; Hagberg Citation2010).

Although the term agencement originally denotes both processes of assembling configurations and the resulting outcome, there is a recent move within market studies towards using the term agencing instead: to capture more of the processes involved in arranging agencements and how agency becomes realised (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016; Hagberg Citation2016). Thus, agencing refers to both the processes of arranging different elements, and the work done to put them into motion (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016, 6). By stressing agencing rather than stable configurations of agencement (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016), it becomes possible to more explicitly study the process in which consumers become equipped as market actors (Cochoy Citation2008). By assembling a certain set of acting elements in anticipation of future situations, actors can also become pre-configured to act in future situations (Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008). Moreover, I will employ the notion of concerning to better capture the work to put agencies in motion.

Matters of concern (Latour Citation2004a) has been defined as “those things and situations that – for better or for worse – are related to us, can affect us and worry us” Geiger et al. (Citation2014, 2). Matters of concern can be further distinguished from individual interests, as they deal with issues of public concern. Mallard (Citation2016) suggests that the noun “matters of concern” could be rephrased into the verb concerning to cover more of the processes in which market actors become concerned about specific matters. Concerning could then be confined to the political work, as taking place in the “spaces for disagreement and negotiation” (Barry Citation2002; Geiger et al. Citation2014, 2).

Moreover, concerning in market practices refers to “the collective process through which a variety of stakeholders (public authorities, suppliers, consumers, NGOs etc.) contribute to shape the resources that make market transactions compatible with these matters of concern” (Mallard Citation2016, 56–57). Thus, creating concerns is a highly collective process (de la Bellacasa Citation2011), developed through the work of multiple entities, which evolve into new identities as “emergent concerned groups” (Callon Citation2007). In accordance with Geiger et al. (Citation2014), concerning, therefore, provides the means to connect and bind members into new identities or representations. The matters that appear to be troublesome to some concerned actors is spread through efforts to relate the concern to others and influence them to also become troubled that, in turn, work to configure them to further engage others (Geiger et al. Citation2014). Hence, I will in this way attend to the processes of agencing and concerning in order to study the production of political consumers in situated representational practices.

Study design and method

I have chosen to focus upon a single case of a consumer cooperative in Swedish food retailing in order to investigate the production of political consumers. This is a particular interesting case to study since consumer cooperatives were originally organised in order to ascribe greater market power to consumers (Ruin Citation1960; Björk and Kaijser Citation2014). Meanwhile, current research on the organising of consumer cooperatives in the retail sector remains relatively scarce, despite its potential import for making consumers more influential in the market (Kjeldgaard et al. Citation2016). Thus, studying this retail context can provide a richer understanding for the different tools and capacities that consumers may possess in the shaping of markets.

This study empirically follows one effort to render consumers capable of voicing concerns within the Swedish consumer cooperative federation (“Kooperativa Förbundet”, KF) and in one of their member organisations: the Stockholm Consumer Cooperative Society (SCCS). Together they stand as the owners of the food retailer Coop Sverige AB. KF is in the process of revitalising its business operations and member organisations after several years of declining sales and member engagement (Edsta and Näslund Citation2014). As part of this work, they have recently introduced a new parliamentary order with owner representatives that aims to strengthen the link between the members and the business operations at local Coop stores. This calls into question how consumers, through membership in formal associations, are represented and how they, as owners, can make their voice heard in markets.

The concept of representation is pervasive and perhaps overrated (Fenichel Pitkin Citation1967; Lynch Citation1994); nevertheless, it is useful in exploring the inter-relationships between two common distinctions: for example, markets, and consumption. According to Lynch (Citation1994), any form of representation needs to be understood in its proper context. Problems arise when we analytically attempt to ascribe a stable set of properties to representational entities when they have been removed from the actions that performed them in the first place. This is the case when consumers, for example, are a priori represented as active market actors. As a way of getting around this matter, Lynch (Citation1994) proposes an “exploded view” of representation, whereby ordinary means of investigation are used to study the very practices and methods employed by practitioners who are said to represent something or someone. This approach implies that one should attempt to study how representations come into being rather than simply trying to establish what they are per se.

Data collection was conducted during one year by participating in multiple events that are connected to the representatives. I thereby “followed the actors” (Latour Citation2005) through ethnographic observations in multiple sites (Czarniawska Citation2007): mainly, the introduction of owner representatives in the SCCS. After conducting initial interviews with the Project Managers and the Head of Environment and Consumption at SCCS, I gained access to different meetings and activities with the representatives where I performed participant observation (see ). These included a board meeting, an election, three education sessions, and an “Inspiration Day.” I also attended a gathering where the representatives got introduced to their respective store managers, an annual meeting, and a forum to discuss sustainability issues with those in charge of the environment at Coop and SCCS. In parallel to these events, I followed the different activities that representatives conducted in five different stores: in-store elections, meetings with store managers and customers, and other store activities. Complementing the observations, I also conducted shorter interviews with representatives, substitutes to the representatives, and several customers. Moreover, I collected various artefacts that the consumer cooperative produced: such as member motions and leaflets, in addition to taking photographs of different materials in use. A summary of the number of interviews, observations, and other collected material can be found in . The voices and the materiality involved were recorded and photographed with the aid of a multi-functional mobile phone. Meetings and events were recorded with the permission from the organisation and actors involved.

Table 1. Summary of data collection.

The analysis has been conducted in iterative steps, moving back and forth between the empirical and theoretical during data collection. Observations were documented in a field diary following the events. I listened through critical episodes of my recordings, which were then transcribed and translated from Swedish into English. The transcribed material was then coded based upon empirical themes that emerged from the data, which gradually moved from first order of concepts to second order themes (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013). An analytical structure based upon more aggregate dimensions of major empirical episodes subsequently appeared, which allowed me to structure an empirical narrative in relation to four inter-related theoretical concepts: (s)electing, equipping, engaging, and enacting. These steps first served to group the overall empirical material in different sections, which consisted of rich text, quotes, pictures, and observations from the field. Each step was first illustrated with three different empirical scenes. The text was further edited after several revisions in order to highlight the most relevant parts, which were further analysed with the aid of the theoretical concepts and previous literature.

Empirical context: the consumer cooperative in Swedish food retailing

The consumer cooperative federation (KF) in Sweden was established in 1899. KF is an economic association consisting of 31 different consumer associations and directly connected members, which amount to 3.4 million members (KF Citation2016). This means that almost half of the adult population in Sweden stand as owners of KF. Founded in 1916, the SCCS, with its 750,000 members, is the oldest as well as the largest of the consumer associations in KF. Although KF operates several different consumer-owned businesses, its largest commitment lies with the retail business corporation, Coop Sweden. KF (with 67 per cent) and SCCS (with 33 per cent) are the formal owners of Coop Sweden AB. Together, they issue specific owner directives to Coop.

The Swedish food retail market is highly concentrated; three major actors dominate the industry: ICA, Coop, and Axfood. As of 2015, ICA held 50.7 per cent of the market share; Coop had 19.8 per cent, and Axfood had 16.1 per cent (HUI research Citation2016). For Coop, this is a decrease by −0.8 per cent from the previous year: a reduction that keeps repeating annually. Edsta and Näslund (Citation2014) report on ongoing financial losses within KF over the last 25 years and call to question whether they currently are facing “their last battle.”

Through a “new historical agreement,” an organisational structure was enforced in 2013 where the consumer cooperative federation (KF), along with ten other consumer associations, decided to recreate Coop’s business unit into a new company called Coop Sweden AB (Coop Citation2013). In doing so, all operations connected to the running of the stores became part of the same company, which was previously run through KF’s different subsidiaries and the various consumer cooperative societies.

Thus far, the reorganisation has started to pay off. Coop reported in 2015 a profit for the first time in many years, which shows that they are in a “turn-around-process” (Coop Citation2016). The company’s CEO asserts the following:

All that we do ultimately has one purpose: to create one Coop. With a clear profile and an attractive brand. We shall be the company that sets the agenda on the retail market: who is the good force. For example, this includes our active work with sustainable development, which is part of our DNA. (Coop Citation2015 annual report, 5)

Consumer cooperatives in Sweden were historically set up as alternative means of exchanging products, based upon democratic principles and cooperation among consumers to gain market power through collective purchases from reliable producers (Ruin Citation1960). Membership in these organisations would ensure good prices and high-quality food products at a time when price cartels and dishonest trading were common (Björk and Kaijser Citation2014).

Coop released a commercial in 2015 conveying its history of past resistance to dishonest trading and the company’s efforts to promote improved conditions for the consumers: from breaking the price cartel on margarine in 1909, introducing declarations of content in 1946, and the dating of products in 1963, to the development of new product categories of organic food in 1986. In this way, KF and its members are portrayed as having played an important role throughout history by spearheading changes in food retailing in Sweden (Andersson and Sweet Citation2002). However, with alarmingly negative economic results over the last decade (Edsta and Näslund Citation2014), the consumer cooperative struggles to be an alternative force in Swedish retailing. Coop admits in the commercial to have lost connection with its original purpose, by stating:

Somewhere along the way we lost the reason to be and the mission we have. We started to believe that we are like all the other food chains. Now we will do all that we can to once again be the good force in the food nation of Sweden. […] The most inconvenient food chain in Sweden is back again. (Quote from Coop commercial, 2015)

The ideas of an organic assortment was initiated in 1984 by thirteen women who demanded to meet the management to voice their concerns on how food could be produced in a better way. (Mersmak, Citation2015, Issue 3, 38)

Several consumer societies have decided to introduce a new parliamentary order as part of the efforts to vitalise member democracy, bringing the members closer to the in-store operations through what is known as owner representatives (“ägarombud”). The election of these representatives in each store is intended to strengthen the connection between the respective stores and its members. The new organisational structure, which was tested in other associations before, was initiated at SCCS in 2015. I will now describe in an empirical account the process involved in trying to produce politically active Coop consumers.

Findings and analysis: producing politically active Coop consumers

The findings section first explores the agencing of political consumers through arrangements of (s)electing and equipping owner representatives as embodied spokespersons for the consumer. Secondly, the processes of concerning consumers and other market actors are explored by analysing ways of putting these arrangements into motion whereby owner representatives work to engage others to enact matters of concern.

Agencing consumers: arranging consumer representations

Processes of agencing consumers involve ways of arranging entities, which are attended to in this case through the representations of consumer images that become enacted through practices of selecting, electing, and equipping political representatives.

Selecting: configuring political consumer images

First, the making of a representative is a matter of selecting members with the right substrate with which to start. Specific election committees are designed in a democratic manner particularly for this purpose, initially involving intense work of searching for election committee candidates, who in turn should search for members that will be nominated in the upcoming elections. Each Coop store constitutes one election district for which the election committee suggests a representative and, if possible, also a substitute. The election committee should ensure the nominee is a member who shares the cooperative values and fulfils the pre-defined criteria for the member representatives. This idealised image (cf. Aléx Citation1993) works to guide the search process, thus, preconfiguring the future owner representative (cf. Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008).

A typical script working to preconfigure the candidates is the open call for owner representatives. For example, SCCS designed a pamphlet entitled Do you have what it takes to be an owner representative? The pamphlet outlined the qualities expected in those who aspire to become a spokesperson, thus, informing them that they search for someone who: “wishes to represent the members in your store, who share our values, and who wants to work in the consumer cooperative society’s best interests.” Moreover, it is stated that: “You often shop at Coop; you keep track of what is happening in and around the store, you have an interest in food, ecology, and health, and you like to meet and talk to people.” The successful applicant is granted compensation for the work through payment, but foremost receives: “a good education, while playing a role in creating fun events around issues of the environment, ecology, and sustainable consumption. Above all, you will be given a fantastic opportunity to influence.”

The SCCS operates 116 Coop stores, which all need to have at least one representative. The pamphlet was distributed in the stores, the member magazine, on SCCS’s website and on their popular member day at Skansen in August 2015, which gathered around 20,000 members. As a result, more than 500 respondents showed an interest in becoming a representative. To apply, the candidates were required to fill in the following information on the SCCS webpage: age, main education, work experience, previous commissions within and outside the cooperation, and the area in which they feel a special engagement: for example, consumer concerns, environment, ecology, health, foreign aid, cooperation, and Fairtrade. Each applicant was also required to express why he or she would be a good candidate. The election committee selected around 230 candidates out of the 500 nominations, to proceed in the selection process. These names were listed on a spreadsheet, of which I reviewed a sample of hundred responses. Each candidate listed numerous reasons for applying for the position; some responses were more common than others (see ).

Table 2. Reasons for applying to the role as owner representative.

Electing: efforts to legitimise the link between selected representatives and members

The actual elections took place both online and in the stores: an arrangement that formally worked to legitimise the link between the chosen representative and the wider member base. In order for this link to be established, however, actual members must be inspired to vote for the candidates. Therefore, different devices and means to engage customers are organised within the store. For example, a temporary polling station was put up upon entering the store, consisting of a laptop on a table with some signs attached to it that advertises the elections with a promise of a reward: 3000 member points for everyone who votes ().

According to some members who acted as election officials, most customers knew nothing about the store, nor that there is an election going on: “They just ran in and out. But if we can catch them, we can tell them that they are needed here.” The customers were then asked if they had a member card. They were subsequently invited to log into the computer where they would encounter the nominees for the election, often for the first time. Pictures could be seen, along with a short statement from each candidate. One can subscribe to the election committee’s proposal by ticking the box on the next page: “I vote for the elections proposal,” where one of the candidates is already listed as a regular representative; the other is listed as the substitute. The voter is then required to fill in his or her 7-digit member number and 10-digit personal number.

Voters were then given 3000 member points (the equivalent of roughly 30 SEK). Compared to the previous years when elections were made for representatives to the district board and no awards were offered, this incentive appears to have a major impact upon the number of people who voted (). The reward seems to be an efficient way to attribute agency to the member and, thus, establish a link between the representatives and the members. However, the question is: how strong really is the established link? Compared to the total number of members in SCCS (750,000), the number of voters was still a mere 2.9 per cent. Thus, working to engage the wider member base into political actors seems necessary.

Table 3. Number of voters in different years with and without a reward.

Equipping: socio-material shaping of the owner representatives

The (s)elections pre-configured the owner representatives by defining the right set of personal qualities. In order to make the representatives ready to act, however, they must also be equipped with the necessary knowledge and tools to fulfil their role as a spokesperson. Each elected representative was, therefore, required to complete three educational sessions that the SCCS and Coop organised.

The first session worked to assemble the link between the representative and the consumer cooperative society by introducing the representative to the SCCS and its relationship to Coop. SCCS’ CEO explains in this session that the mission of the consumer society is to “create member benefits and to strengthen your rights as a consumer: to uphold the democratic organisation, to influence Coop and the public opinion, provide member offers, consumer knowledge, and sponsorship.” They were additionally introduced to the practical work of the representative that lies ahead the following year.

The second educational session worked to assemble the link between the store and the representative by focusing upon the store itself and the representatives’ relationship with the store managers. Three people from Coop’s central management team came to talk to the owner representatives, providing them with information about the new plan for how to run the businesses more effectively. Following Coop’s recruitment of a CEO from the competitor ICA in 2014, Coop has undergone a number of changes in management, stressing the need for all the stores to act in concert with each other by following a common path called Our plan (DN Citation2014).

The third session worked to assemble the link between the representative and the context of the store (). The owner representative is supposed to be the store’s “extra eyes and ears”: they monitor competitors, social media, local news, and the customers. Representatives are asked to suggest good ways to get to know what the customers think about the store: for example, they mentioned surveys, neighbours, and acquaintances, a guest book, and an in-store announcement board, as well as having in-store activities that encourage customers to share their views. The key to keeping customers appears to be in the customer encounter, which has been revealed through The Satisfied Customer Index and the Coop Member Panel, of which both also constitute important information channels for the stores. Therefore, representatives are advised to look at each store with new eyes, while paying particular attention to the customer encounter.

Additional meetings were also set up to inspire the representatives for their task with presentations of ongoing trends in and around the store. Herein, the representatives were asked in a group exercise led by SCCS’s steering board to discuss “how the representative should retrieve well-founded questions and opinions in the meeting with the store manager.” The CEO admitted that there was a specific thought behind the question: information generated by the representative should not only portray their own concerns or those of their closest friends. The CEO, however, acknowledged that generalisable and statistical surveys already exist, citing The Satisfied Customer Index as an example. Moreover, the representative was required to convey information about the consumer cooperative society to the members (e.g. the new loyalty programme) in addition to inform them about Coop’s high-value product campaigns (e.g. Fairtrade and organic food). Thus, it became necessary to equip the representatives with background knowledge of the consumer society and the Coop stores.

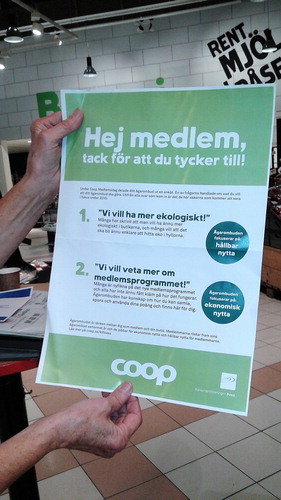

Equipping the representatives does not only concern the education sessions, however; it also involves a material dimension: for example, providing a specific type of clothing and different gear: such as pins, nametags, email accounts, leaflets, and so on (). Moreover, the so-called member point is a physical place that constitutes a meeting point for the representative and the members during in-store activities (). During these activities, the representative would normally stand close to the member point in an attempt to attract people’s attention: for example, to the member programme that is materialised on a computer positioned at the member point. The embodiment of being a representative also comes to matter. Several of the representatives that had been in the store for a couple of hours of interaction with customers stressed the need for breaks: “I think I need to go home now; I cannot talk anymore. After the last Member Day, I was hoarse for two days. I will go and get some more [water] … ” Thus, bodily stamina becomes important in order to maintain a strong voice.

Concerning agencies: putting consumer voice in motion

Processes of concerning market actors involve different ways of putting agencies in motion through engaging and enacting concerns. The engaging of other consumers involves efforts to qualify and provoke what particular concerns they may have. The representatives in turn work to relate and influence the concerns to relevant decision-makers in order to further enact these concerns.

Engaging: qualifying and provoking consumers to express their concerns

The representative acts as a spokesperson between the Coop stores and the members of the consumer cooperative society, implicitly involving all in-store customers. The representatives performed activities in the store in order to become better acquainted with the customers, and to inform them about various matters: such as the membership programme, fair trade or organic food. However, as expressed by one representative, it was often difficult to establish a contact with customers in the first place: “There are many who try to get away [from me] quite fast.”

This implicates that the equipped representative must engage consumers in order to make their voices heard. The consumer cooperative society provided the representatives with various tools in order to produce relevant information about what the members want: such as ready-made customer surveys, which the representative can distribute to the people they meet. Through interaction with the customers in store and by providing surveys, the representative seeks to retrieve and, thus, qualify the members’ viewpoints (cf. Dubuisson-Quellier Citation2010; Ariztia Citation2015): that is to say, finding out what they want and, thereby, produce a specific version of consumer concerns. Meanwhile, the representative provokes customers to actually have a point of view in the first place by asking customers to express what they want (cf. Muniesa Citation2014). Muniesa (Citation2014, 89) previously noted the phenomenon of being provoked: “ … I did not know which perfume I prefer from a set of, say, 20 samples until I was put in a position in which I had to come up with an answer to that question.”

For example, a representative explicitly mentioned that it is good to urge consumers to have an opinion: “It is good to provoke them to say something.” Another representative said that she needed to suggest things to people while they filled in the surveys: something that they might not have expressed or even considered otherwise:

Yes, in principle, you have to help the customers to write something. Most of the people think it’s too banal. But I say that I am interested in everything, your point of view about the store, and about us who stand here, or whatever.

Despite their simplicity, these representations would, in principle, direct and legitimise the link between the work of the representative and the concerns of the consumers. However, given how much work it takes to convince consumers to express their opinions and to only come up with rather obvious statements, one must wonder how concerned consumers actually are in the first place.

Enacting: concerning decision-makers to connect agencies

The representative seeks to strengthen the link with those who make the decisions through practices of enacting concerns, that is: to relate concerns to others in order to connect agencies into new concerned groups that together can act to make a difference (cf. Geiger et al. Citation2014). In doing so, the representatives can for example speak directly with the store managers or approach Coop’s central managers, as well as use the traditional means of influencing in the consumer cooperation through proposing member motions at annual meetings.

One of the representatives revealed his experience of speaking up at the annual meeting in 2014, when he brought up a matter of concern: the use of cans in the Coop stores that potentially contains the harmful chemical bisphenol A as a layer inside to protect the food. Although authorities claim this is not to any harmful levels (Livsmedelsverket Citation2016), the potential impact of bisphenol A has been tested and contested (SvD Citation2012). Since 2011, the European Union banned the use of bisphenol A in baby bottles. In 2012, the Swedish government decided to forbid bisphenol A in all food packages aimed for children under the age of three. However, it is still permitted to use the chemical in any other food packages. The representative says that, after giving his speech, he felt an immense support for raising this matter of concern from other elected representatives, as well as the Head of the Environment and the CEO at the SCCS.

In April 2015, the food retailer ICA announced that they would phase out their cans to use vacuum packages instead (SvD Citation2015). Both Axfood and Coop mention their intention to phase out the cans, yet cannot promise when that will occur. Other alternatives are already in the store: for example, tetra packs; however, they are not the retailers’ own brand. When the Head of Environment and Consumption at SCCS later asked Coop about the use of cans for products of Coop’s own organic brand, Änglamark, it was explained that the factory where they produce Änglamark chickpeas and beans only permits cans in its assembly line, making it difficult to switch to other types of packaging instead ().

During one of the in-store activities, the representative encountered a customer who shared his concerns over the use of cans at Coop. This customer, an older lady, brought up the issue when they met and said that she had reminded the store manager about it. The representative agreed: “I can only continue to email them [the managers at Coop]. They say that the factory cannot be converted, but why can ICA and Hemköp [the competitors] (successfully) do it?”

The concerned representative once again mentioned the issue of cans at a sustainability discussion forum of the 2015 annual meeting. At a follow-up meeting in February 2016, the representative persisted and raised his concerns once again. The sustainability manager at Coop then explained:

We are working on trying to phase out bisphenol A from our packages, and this is where we have a problem too. We want to get rid of the cans, but since we do common purchases with other countries, such as Coop Denmark, Coop Finland and Coop Norway, we face some challenges since they want to keep the cans. And for some products, we have not found any good alternatives yet. We are working on it, but we are not quite there yet.

Hence, one representative’s repeated efforts to phase out cans reveal how they can potentially influence decision-making, yet are also kept at a distance. While managers are eager to listen to the various concerns from the owners, they are also busy dealing with other operational matters that are central to the organisation. Managers need to connect and stabilise multiple agencies (e.g. collective purchases with the Nordic partners and capacity in factories), before he or she can engage the owner representative in any decisions. Some matters of concern will be picked up and put into motion when stabilised agencies are ready for change, yet there are still many other issues that will not fall onto equally fertile ground.

Nevertheless, as the Head of Environment and Consumption at SCCS also expressed, the owners do not represent the only and perhaps the most effective way to influence:

There are other ways to influence that are equally effective, I would say. I mean, three emails on a question on the same day: this is a public outcry in the customer contacts and it gets directly into the board of Coop … . and spreading bad rumours on twitter or Facebook, it hits immediately. (Head of Environment and Consumption at SCCS)

Discussion: liquid agencies in the production of political consumers

This research suggests that the production of political consumers in cooperative retailing can be understood by attending to the processes of agencing and concerning that work to arrange and enact representations of political consumers. The empirical study has revealed how the consumer cooperative strives to produce owner representatives who can strengthen the link between owners and stores. In this process, the cooperative is both driven by, and works to produce, an idealistic image of the politically active consumer.

illustrates an analytical framework for examining how processes of agencing and concerning work to enact representations of political consumers. The figure captures how the gap between the “ideal” of politically active consumers and “real” consumers gradually become bridged through processes of agencing and concerning, as mediated through the representative. Different socio-material actors perform these processes, which work together to arrange and put into motion political consumer representations through essentially four practices: (s)electing, equipping, engaging, and enacting. Multiple forms of agencies are enrolled in these processes that gradually work in different ways to realise idealised images of political consumers.

However, realising these consumer images and, thus, agencing consumers to voice their concerns, requires continuous work to first connect and then put into motion the multiple forms of agencies within the cooperative retailer. To capture this multiple and fluid character of agencies, I draw on Bauman (Citation2005) and use the metaphor of liquidity to introduce the notion of liquid agencies (cf. Hagberg Citation2008). This refers to the dynamics of agency and asserts that the consumer capacity to act and make a difference in markets is a continuous process in need of ongoing efforts and multiple mediators to streamline agencies in order for them to have an effect. The concept of liquid agencies, however, is not used as an analytical tool for evaluating modernity (Bauman Citation2005), nor does it depart from any pre-determined dichotomies (active–passive) or spectrums (solid-to-liquid) in the forms of consumption (cf. Bardhi, Eckhardt, and Arnould Citation2012; Bardhi and Eckhardt Citation2017). The concept works instead to capture the process and plasticity of how agency is continuously acquired in the dynamic socio-economic context of the market (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2007). Ontologically, liquid agencies emphasise the emergent state of the world, thus, assuming ontological instability (cf. Zwick and Dholakia Citation2006): where stability is seen as a temporal outcome. As such, agencies only momentarily become stabilised with different effects depending upon how they are associated to each other (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2006). To gain momentum, liquid agencies however need to be kept in motion through processes of concerning that continuously work to relate and bind agencies together as new matters of concern may arise. In this way, the stability and liquidity of agencies become two sides of the same coin.

This concept will be further discussed in more depth in relation to the analytical framework and research questions that focus upon the following: (1) How do political consumers become produced in retailing? And (2) how can such political consumers become enacted to voice their concerns in retail transformations?

Producing political consumers: arranging multiple and liquid agencies

To describe the processes in which political consumers become produced, I will follow the work of Diaz Ruiz (Citation2013) and Hagberg and Kjellberg (Citation2015) who argue that representational practices play a role in the construction of markets. I postulate that such practices also take part in the construction of consumer agency and the making of political consumers. As Kjellberg and Helgesson (Citation2010) suggest, ideas, models, and various representations not only describe an existing reality; they also contribute to make it a reality (Donald and Millo Citation2003; MacKenzie Citation2004; Callon Citation2007). Nevertheless, these representations also need to become inscribed with agency to have an effect. The agencing (Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo Citation2016) of these representations involves acts of arranging what to represent and to agence, thus bringing together a set of qualities connected to the representation of politically active consumers.

Through the overall processes of agencing consumers, the specific qualities of the owner representative first become arranged and pre-configured through selections based upon idealistic images of active members (). These representations work to identify consumers within the wider member base who have the right set of qualities. For example, the advertisement searching for representatives had a long list of personal criteria. The election committee, guided by this idealised image (cf. Aléx Citation1993), subsequently selected suitable candidates, thus, enacting the image of the political consumer. As previously shown, the resulting nominees also resembled the idealistic image: for example, someone who is familiar to the local store, talkative, and likes the cooperative idea as well as organic food.

The pre-selected member formally becomes a representative through subsequent elections and is, thus, entitled to represent the voice of the owners. However, the capacity of members to cast their vote was not taken for granted. Instead, the election officials had to rely upon a number of technical and democratic tools needed to vote (Barry Citation2002; Asdal Citation2008): such as a polling station with a computer that had an internet connection. Moreover, the election officials also needed to build up the members’ capacity to vote by inscribing them with other agencies not normally associated with politics: to award the act of voting with loyalty credits. This implies that there are multiple liquid agencies floating around that need to become arranged and allied in order to have an effect. However, the effect might not necessarily be a political consumer. As Barry (Citation2002) stated, framing political action through politics holds the potential to make the actions apolitical in the end. Using loyalty credits for compensating a lack of political engagement to start with could especially run the risk of substituting something political with ordinary consumption activities: that is to say, collecting loyalty credits.

The subsequent process of equipping the elected representative then works to agence the representative with a certain set of qualities and devices that prepares them for future situations (Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008). As representatives, they become equipped to constitute a link between several different agencies: the consumer cooperative society, the store, and the context of the store. The potential to become political and to mediate matters of concern between these different sites lies in the capacity of the representative to locate spaces of disagreement and possible solutions. In order to do so, the representative becomes equipped with different socio-material tools that could enable the representative to retrieve knowledge of customers and their opinion of the store: such as pre-designed customer surveys and in-store activities. Thus, the processes of agencing consumers that inscribe representatives with the right set of qualities work to bring the “real” consumer closer to the “ideal” political consumer ().

Through the subsequent processes of concerning, the agenced representative works to engage (Thévenot Citation2002) others to voice matters of concerns and, thus, links the “ideal” consumer closer to what is “real” (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010). To begin with, there is a need to arrange what particular concerns should be represented and voiced. Coop’s central administration and the owner representatives made several attempts to represent consumer concerns through surveys and member panels. Through engaging with consumers, the representative worked to qualify their concerns (Dubuisson-Quellier Citation2010; Ariztia Citation2015). In doing so, they also provoked (Muniesa Citation2014) potential issues that could be brought up in the survey as suggestions for improvement. For example, the pre-specified questions in the survey directed to customers in the store, gave the respondent a certain set of options from which to choose. This provoked certain representations: such as “We want more organic food.” The representatives, thereby, helped to represent different consumer concerns that, in turn, aided sustainable marketing efforts (Fuentes Citation2014; Citation2015): in this case, by proposing to provide more organic food.

However, the owner representative’s difficulty to first get in contact with customers rushing in and out of the store and to get them to come up with potential matters that would concern them, calls into question whether these concerns are even that concerning. The political, hence, subject areas of disagreement (Barry Citation2002), have already cooled off to a large degree, whereby agreements are easily identifiable (Callon Citation1998). This indicates that the “real” matters of concern potentially lie elsewhere and that the representative would need to be better equipped to qualify (or provoke) them.

Moreover, problems arose regarding whether or not these kinds of representations of concerns were useable (cf. Sjögren and Fernler Citation2010). For example, this was debated in a discussion forum: how the representative could raise well-founded questions and opinions in the meeting with the store manager, implicitly doubting that the representative was presenting ideas other than his or her own self-interests.

The problem lies in knowing whether or not the information the owner representatives have retrieved is reliable, which stems from the fact they represent multiple agencies. For example, they both represent others and themselves as significant owners, loyal members, and random customers, while also constituting a link between the store manager and the consumer association. The owner representatives are equipped for all of these situations; however, the crux seems to be how to represent what the owners really want. Another dimension of this problem resides in the large numbers of owners (more than 3.4 million!) with only small stakes and interest in the business organisation.

In order to retrieve any general claims of what the owners want, we would need to bring them together and recognise them as one actor (Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008). The owner directives constitute an important script for Coop, which is an example of where this actor constellation is effectively arranged and put into motion. Nevertheless, one problem arises: these directives do not necessarily account for the multiple and liquid actor constellations of the owners and their representatives.

Cooperative retailing is being trapped in a dilemma: whether to remain true to the cooperative idea and stay permeable to the fluidity and multiplicity of consumer concerns or to strive for efficiency to remain competitive on the market. Staying attuned to the market dynamics requires openness to the changing socio-economic conditions of which consumer concerns are part of shaping. Meanwhile, the concerns are also being shaped by the retail organisation wanting to be “the good force” in retailing, thus, provoking consumers to become more concerned and politically active. In order to also enact consumers’ voices and make them matter in retail transformations, there is, however, a need to scrutinise how liquid agencies become associated with each other.

Enacting consumer voice: mediating and setting liquid agencies in motion

The cooperative retailer seeks to revive their competitive edge as a cooperative while separating the business operations from the consumer associations. This hybrid retail form (Papakostas Citation2012) for which the cooperative has opted seems to require different connections of agencies for different purposes. As Kjellberg and Helgesson (Citation2006) suggest, entities become different things depending upon how they are associated with one and other. As we will see, the ontological liquidity of agencies comes in handy in managing the hybridity of this retailer.

The historical image of politically active consumers was picked up and (literally) put into motion in a Coop video commercial. Herein, the portrayed actions became attributed to a certain set of actors (Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008): namely, the collective actions of political consumers within the cooperative. Even though the actions of consumers in the cooperative are dependent upon the performance of many other entities that also produce these actions, there is a tendency to purify a complex world in order to understand it (Latour Citation1993; Canniford and Shankar Citation2013). The purification whereby many actors become allied as one is also maintained for other purposes: such as in a commercial seeking to attract new political consumers and potential customers. In this way, there is a possibility to tinker with agencies (cf. Fries Citation2010) whereby agencies are rendered liquid and then, in retrospect, become ascribed with political powers based upon historical experiences of making a difference as one actor.

Despite the need for recognition as being one actor, which the CEO of Coop stresses, the agencies need to be kept apart at times. For example, in KF and Coop's recent reorganisation, all business operations and decisions became centralised in the new Coop Sweden AB. By keeping the two organisations separate while simultaneously forging stronger connections within the new organisation through increased collaboration, Coop could incite a capacity to act for the retail organisation that was more adapted to the competitive market conditions. However, this also meant a withdrawal of power for the consumer association to directly influence business decisions.

Meanwhile, the creation of owner representatives can also be seen as an effort to reconnect the organisations by deliberately attempting to strengthen the link between the members in the consumer association and the business operations. The representations that the owner representative performs, however, can also be created for purposes other than actually representing the owner’s view. For example, the representatives provide the means to establish contact with people in the store in order to sustain a continuous customer dialogue. In doing so, they work to maintain the image of the political consumer despite the separation of the business unit and consumer associations to achieve a more streamlined organisation.

A more centralised organisation with inter-connected agencies, however, affects the agencies of other actors. For example, store managers have a rather limited capacity to act on their own means: such as easily introducing an alternative assortment to canned food. The agency of the representative that raises his or her concerns over cans might have influenced the decision of the sustainability manager, yet the owner representative was constantly kept at a distance until the issue was settled. There were instances in the store, however, where separate agencies could be activated for other purposes: such as when the incentive to get members to vote for the representative was to offer customer loyalty credits that were normally used as a reward for repeat purchases.

The SCCS itself is another efficacious constellation of where the multiple agencies act under a common label (Andersson, Aspenberg, and Kjellberg Citation2008). This is in line with Helgesson and Kjellberg (Citation2005) and their assertion that macro actors can represent something on a larger scale than its constituent parts. Grouping a large number of members with common concerns is much more effective than if one representative were to act alone. In this sense, SCCS could be regarded as a macro actor that amplifies certain voices, while simultaneously muting others (Helgesson and Kjellberg Citation2005). Helgesson and Kjellberg (Citation2005, 150) explain this phenomenon:

Metrological apparatuses (that) simultaneously channel, amplify, and translate some “sounds” from the periphery, while muting others. It is these two sides of reducing – amplifying and muting – that together make up the lever of a metrological apparatus. (Citation2005, 152)

The creation of owner representatives could ideally mediate matters of concerns in a systematic and democratic way. A large number of owners channelled through a representative can potentially raise their concerns and speak up across different situations in Coop to make a greater difference as a macro actor. The representative would as such mediate between the “real” and “ideal” political consumer: being agenced to bring these two versions together as one actor ().

According to Cochoy, Trompette, and Araujo (Citation2016), agencing processes are not only categorised into the arrangement of different elements; they also include the work that is done to put them into motion. Other actors would, in turn, need to recognise the concerns and further translate them in order for a matter of concern to be enacted in practice and put into motion. The question then is how the liquid agencies and concerns connected to them could be put and streamlined into motion.

The concept of concerning proves useful to explain how agencing processes require new concerned actors to be enrolled in order to maintain an engagement around matters of concern (Geiger et al. Citation2014; Mallard Citation2016). Concerning refers to the collective processes that worry, relate, and influence actors around particular matters of concern (Geiger et al. Citation2014). For example, the worry for the presumably harmful plastic bisphenol A in baby bottles was initially reported in media, and subsequently related to the containment of the plastics in cans of any conserved food being sold in grocery stores. One worried owner representative consequently takes on the role to influence others in ongoing efforts to also make the retailers’ decision-makers concerned about this matter. In order to influence their suppliers to switch their production lines, the Coop in Sweden also needs to influence their Nordic partners with whom they cooperate. Concerning processes, hence, involves a collective work of relating plastics, baby bottles, and cans to retailers and their suppliers in an effort to connect multiple agencies and, thereby, enable a capacity to convert to bisphenol-free cans. Thus, ways to deal with the multiplicity and liquidity of agencies are to forge connections between multiple roles (Nordic cooperatives and suppliers), while simultaneously trying to keep some of them apart (production lines of cans).

Agencies come into force in this way whereby the capacity to make a difference depends on how agencies are arranged and put into motion through processes of concerning. Agencing and concerning efforts, therefore, need to work in tandem in order to have an effect, which implies a circular and iterative process (). Thus, the building of consumer capacities to achieve changes in markets is a continuous and collective achievement, in which previously unrelated agencies come to change character depending upon how they become connected to each other.

Conclusions and suggestions for further research

I have shown in this paper how political consumer representations become produced by attending to the agencing and concerning of consumers and other market actors. The arranging of agencies is constituted through (s)elections and equipping processes, while the work to put agencies into motion requires efforts to engage and enact multiple and liquid agencies to become concerned and associated with each other. In this ongoing work, political consumers both become shaped while they are also part of shaping this idealistic consumer.

By providing a process perspective on the production of political consumer representations, this research is in line with extant market studies that stress the ongoing practices, which constantly work to bring different version of markets and consumers into being (cf. Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2010). In so doing, the study reveals the difficulty to engage consumers in market politics: where consumers must be convinced to vote and further provoked (Muniesa Citation2014) to express their concerns. This stresses the need for multiple socio-material mediators (Latour Citation2005), such as democratic procedures in electing owner representatives as well as market mechanisms of distributing loyalty credits. Together and in different ways, mediators can agence consumers to voice their concerns and, in doing so, become political.