ABSTRACT

Consumer understanding of the past often revolves around myths or sanitized versions of history. Consumers resort to these fantasies to connect with values they feel are lost in modern life. Interpreted, however, such imaginations may also invoke moral dilemmas. Findings from interviews conducted on-site at a Viking-themed restaurant indicate that this is the case with the Viking myth, which has been misappropriated by white supremacists. Using Derrida’s concept of “hauntology” as a theoretical lens, findings suggest that the Viking myth, in addition to nostalgia, may evoke feelings of collective guilt when inscribed in a present-day ideological landscape. Findings also show that consumers can resolve such mythological tension by employing atonement as a self-authenticating act. The theoretical framework of collective guilt as a hauntology explains relationships between consumer myth-making and nostalgia that have not been recognized by prior research on past-themed consumption.

The specters of the past had been exorcised for years; though they were of course to be found hidden in everything (Tomasi di Lampedusa Citation2007/Citation1958, 207).

“If the past is a foreign country,” Lowenthal (Citation1985) once declared, “nostalgia has made it the foreign country with the healthiest trade of all” (4). Consumer researchers agree that nostalgia continues to be inextricably linked to myths or sanitized versions of history (e.g. Brown Citation2018; Brunk, Giesler, and Hartmann Citation2018; Cervellon and Brown Citation2018; DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin Citation2019). Consumers resort to these fantasies to connect with values they feel are lost in modern life. However, as noted by Brown and colleagues (Citation2001), consumers do not seek “to understand history in its own terms, but in today’s terms” (55). Taking such anachronism into consideration, myths and other signifiers of pastness may also invoke the specters of historical wrongdoing when inscribed in the present, animating moral dilemmas for the consumer (Baker, Motley, and Henderson Citation2004; Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler Citation2010; Robinson, Veresiu, and Babić Rosario Citation2021; Thompson and Tian Citation2008).

There is a need to reflect on the doubleness of romantic memories, on feelings about the past that combine intensified nostalgia with guilt feeling. Guilt regulates many consumption processes (Antonetti and Baines Citation2015; Chatzidakis Citation2015; Huhmann and Brotherton Citation1997) but is yet to be studied in relation to past-themed consumption. For this purpose, I use Arendt’s (Citation1968) definition of collective guilt as guilt by association, i.e. the idea that individuals who are identified as a member of a certain group carry the responsibility for an act or behavior that members of that group have demonstrated, even if they themselves were not personally involved. In other words, one can be held liable for things one has not done. Meanwhile, Mead and Baldwin (Citation1971) describe atonement as “useful guilt” (59) and “when you talk about atonement you are talking about people who were not born when [the crime] was committed” (177). Atonement denotes someone taking action to repent for a previous wrongdoing. Little is known about the dynamic between collective guilt and atonement in past-themed consumption where focus has mainly been on the sugar syrup of nostalgia (e.g. Brown Citation1999, Citation2001; Brown, Kozinets, and Sherry Citation2003; Goulding Citation2001; Hartmann and Brunk Citation2019; Holbrook Citation1993; Stern Citation1992).

While there is no doubt that myths can serve as vessels for nostalgia (Belk and Costa Citation1998), there is a pressing need to understand how they may also evoke specters of historical wrongdoing. Thus, heeding calls for more research studying menacing aspects of nostalgia (Brown, Patterson, and Ashman Citation2020), I address two research questions: (1) How are consumer feelings of nostalgia affected when myths are exposed to mask problematic elements in the past? (2) How do consumers resolve such mythological tension? I chose the Viking myth market in Sweden to answer the research questions. As the late David Lowenthal said in this journal, “in Sweden many people seem keen to re-enact some past experience or past ways of life” (Edwards and Wilson Citation2014, 107). Indeed, this is a market where issues of nostalgia and spectrality are ever-present. On the one hand, the Viking myth has been misappropriated by white supremacists looking to justify their xenophobia and acts of violence, which raises questions of collective guilt. Viking symbols are everywhere among the ultra-right, with Thor’s hammer being prevalent among neo-Nazi groups. The perpetrator of the 2019 Christchurch massacre in New Zealand wrote, “See you in Valhalla” at the end of his manifesto (Kirkpatrick Citation2019). More recently, Viking helmets were used as a countercultural fashion signifier in the “incel” storming of the US Capitol, in which more than 200 were arrested (Sullivan Citation2021). On the other hand, the Vikings are thought to embody values that have disappeared in contemporary urban life, such as “self-reliance, initiative, and ruggedness” (Belk and Costa Citation1998, 221) and “a sense of comfort and close-knit community” (Brown, Kozinets, and Sherry Citation2003, 20).

This article aims to scrutinize how the relation between myth and ideology shapes experiences of nostalgia in past-themed consumption. First, this article highlights how mytho-ideological tension may give rise to “spectrality effects” (Derrida Citation2012/Citation1993). Second, I extend the literature on nostalgia by explicating its hauntological relation to collective guilt, introducing and defining the concept of the haunted imagination as an amalgam of Derridean hauntology and collective guilt. Hauntology is a concept developed by Jacques Derrida in his book Specters of Marx, referring to the return or persistence of elements from the past, as in the manner of a ghost (Coverley Citation2020). It is a portmanteau of the words haunting and ontology, thus denoting cultural aspects of haunting, such as the manifestation of absences in cultural hegemony. Specifically, I emphasize the affective role of specters and spirits as a significant way of understanding consumer meaning-making in the evocation of the mythic past. Contrary to specters that are negative and backward-looking, spirits are, to put it crudely, more optimistic and forward-looking. Third, this article has implications for the authenticity literature by extending prior research on how traditions are rooted in myths that are upheld as “genuine, real, and/or true” (Beverland and Farrelly Citation2010, 839). More precisely, the recognition of atonement as a self-authenticating act offers promise as it acknowledges how consumers purposely reconjure haunting specters into something soothingly spiritual.

This paper is structured as follows. I begin with a brief review of the tenets of nostalgia in past-themed consumption specifying the theoretical gap that I address, whereby hauntology is proposed as a framework to understand the disposition of nostalgia and collective guilt. This is followed by the interpretive methods employed to address the research objectives, including a section explaining the enactment of Viking mythos among the enclave of “woke” Vikings in Stockholm (the term “woke” refers to a perceived awareness of issues concerning social and racial justice). In subsequent sections, I discuss insights derived from the data before presenting a model for how nostalgia may give rise to spectral doppelgänger images. Finally, the article concludes with a general discussion of the theoretical contributions and suggestions for future research.

Whither nostalgia?

There is a scene in Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (Citation1983) in which the exiled protagonist, struck by memories of his family back home, is unable to look at a fresco of the Virgin Mary because he is so overwhelmed, both by yearning for the Motherland and his idealization of the virtue of maternity. One could say that the figure of the Holy Mother who has come back to haunt the protagonist is a metaphor of Tarkovsky’s own nostalgia. Indeed, nostalgia was initially a psychological concept used to denote a human desire to return back to the wombFootnote1 (Holbrook Citation1993). Exploring spiritual and eschatological themes, Tarkovsky’s dream-like sequence touches upon still ongoing debates on what constitutes nostalgia in the twenty-first century with striking accuracy. For example, Hamilton and colleagues (Citation2014) identified urban nostalgia and diaspora among the key interdisciplinary themes in current engagements with past-themed consumption (Boym Citation2001). Tarkovsky’s film is also indicative of the spirited nostalgia described in this paper, whose spectral doppelgänger images, for example, can include nationalist or patriot memories (Brunk, Giesler, and Hartmann Citation2018).

There have been more than 200 academic publications on nostalgia in marketing and consumer research since the early 1990s (Veresiu, Rosario, and Robinson Citation2018). It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a full summary of the vast literature on nostalgia and consumer myth-making. While most scholars today agree that nostalgia is a bittersweet emotion—in Greek, nostalgia means pain from an old wound (Brown Citation2018)—the focus has mostly been on its positive and uplifting qualities. From this perspective, nostalgia comes across as a celebration of the past. Costa (Citation1998) argues that the mythic past akin to the idea of paradise underscores the connection between consumption and the good life unburdened by postcolonial guilt. Because of the tendency in previous literature to attach mythic narratives with sacred feelings taken as authentic (Belk Citation2013; Brown and Patterson Citation2000; Thompson and Coskuner-Balli Citation2007; Zhao and Belk Citation2008) or enchanted (Hartmann and Östberg Citation2013), consumer researchers are prone to view both myths and nostalgia with overtly rose-tinted glasses (Belk and Tumbat Citation2005; Bradshaw and Holbrook Citation2007; Brown, McDonagh, and Shultz Citation2013; Kessous Citation2015; Lowenthal Citation1985; Thompson Citation2004a). As noted by Brown and colleagues (Citation2020), “the dark side of nostalgia, the scary side, the unsettling side” (4) also needs exorcising. In their paper on the mountain man myth, for example, Belk and Costa (Citation1998) bring up the “cultural appropriation of Indianness” (235) without providing any further inquiry on its possibly harmful social implications. Indeed, although there is no universally accepted definition of nostalgia in consumption, nostalgia has been ascribed with mostly positive attributions such as carnivalesque (Kozinets Citation2002), pastoral (Thompson Citation2004b), playful (Hartmann and Brunk Citation2019), pure and idyllic (Canniford and Shankar Citation2013). Drawing on Fred Davis’s (Citation1979) sociological study Yearning for Yesterday, a common feature of research here is that nostalgia refers back to an earlier period sometimes even preceding the individual’s lifetime and draws on biased or selective recall of past experiences (e.g. Baker and Kennedy Citation1994; Belk Citation1990; Havlena and Holak Citation1991; Holbrook and Schindler Citation1991).

Furthermore, as indicated by previous CCT scholarship, the concepts of myth and ideology are deeply interlinked (Holt Citation2004; Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler Citation2010; Thompson Citation2004b). “Myth,” Fitchett, Patsiaouras, and Davies (Citation2014) rightly observe, “constructs the idea of a “dominant” mode” (499). “Myth,” Baker, Motley, and Henderson (Citation2004) suggest as a synonym to collective memory as it “explains how members of particular social groups retain, alter, or reappropriate public knowledge of history” (38). “Myths,” Brown, McDonagh, and Shultz (Citation2013) assert, “are ambiguous” (609) and conform to “narrative structures typical of a culture” (Stern Citation1995, 166). Yet, the typology Stern (Citation1995) introduced to consumer research based on Northrop Frye’s taxonomy, consisting of comedy, romance, tragedy, and irony, overlooks one important mythoi, horror. Fear was one of the themes Stern (Citation1988) identified in her landmark study on medieval allegories in advertisements (Brown, Stevens, and Maclaran Citation2021). The horror genre is responsible for some of the highest-grossing films. The Exorcist and The Shining, not to mention Hitchcock’s entire oeuvre, are part and parcel of our cultural DNA. From Stephen King to Edgar Allan Poe, literary giants also have a knack for making their readers fear the dark.Footnote2 In marketing, both Hirschman (Citation2000) and Sherry (Citation2005) rely on spectral figures as metaphors for branding.

For this paper, myths—akin to superstitions and ghost stories—are understood as projections of our assumptions and values onto the world. Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. These imaginations purport to explain and justify what happens in society. In doing so, certain content is suspended. Hence, in the independent film Ghost Dance (McMullen Citation1983) starring the French deconstructionist Jacques Derrida as himself, it is implied that each city creates its own myths to forget something horrible or unspeakable. Elsewhere, Derrida (Citation1986) continues, “there is a memory left of what has never been, and to this strange rememoration only a mythical narrative is suitable” (xxxiii) indicating that mythic structures encrypt horrors in the actual past, leaving out problematic or unspeakable elements for ideological closure. Hence, I seek to address the theoretical gap between the mythic past (which is thought to mask the absence of reality) and the haunted past (in which the myth, less innocently, is exposed to mask a perverted reality) (Goulding Citation2000). To this end, Derrida’s concept of hauntology is applied as a framework for understanding the collectivization of guilt, which is overlooked in extant literature on past-themed consumption. As Derrida (Citation1982) points out, “we must think of this without nostalgia, that is, outside of the myth” (27, italics in original).

A hauntological approach to nostalgia in past-themed consumption

As noted by Higson (Citation2014), modern nostalgia has a strongly temporal dimension to it. However, postmodern nostalgia is more inclined to the atemporal. The irrecoverable becomes attainable, which leads to a certain type of cultural dyschronia as the tension between past and present is so easily overcome. Artefacts, Ahlberg, Hietanen, and Soila (Citation2021) note, are plucked from history and stripped bare of their problematic historical context. Derrida (Citation2012) studied hauntological dimensions of this condition, such as the uncanny impression, the déjà vu, when signs and commodities seemingly returning from the grave are conjured not only with nostalgia but with spectrality effects. As Jameson (Citation1999) explains, spectrality has nothing to do with whether or not one believes in ghosts. Consider, for example, the Whitney Houston hologram tour that was launched a few years ago, which one reviewer described as a “ghoulish cash-in” and “jerky simulacrum” (Simpson Citation2020)—one hardly has to believe in ghosts to fear the specter(s) of capitalism!

The term hauntology refers to temporal and ontological disjunction in which presence is replaced by the figure of the ghost as that which is neither present nor absent. Derrida (Citation2012) shamanically elaborates, “time is disarticulated, dislocated, dislodged, time is run down, on the run and run down, deranged, both out of order and mad. Time is off its hinges, time is off course, beside itself, disadjusted” (20). More specifically, Derrida (Citation2012) insists on “disjointure … this radical untimeliness or anachrony” as the basis for an attempt to “think the ghost” (29, italics in original) as something that is “neither living nor dead, present nor absent: it spectralizes” (63).

From reboots to reunions, applying the concept to contemporary consumer culture, it seems that the present is oversaturated with undead significations to its own past as manifested in persistent recycling of retro aesthetics and incapacity to escape old social forms (Brown Citation2001; Mackintosh Citation2021; Reynolds Citation2011). Specifically, drawing attention to the shift into post-Fordist economies in the 1970s, Fisher (Citation2014) argued that neoliberalism has “gradually and systematically deprived artists of the resources necessary to produce the new” (15). From this perspective, there is a doomed sense that the future has been canceled (Ahlberg, Hietanen, and Soila Citation2021; Bradshaw, Fitchett, and Hietanen Citation2020). For example, social media and other technological innovations encourage us never to fully commit to the present, fostering a ghostly presence–absence (Deuze Citation2016). Taking consumer culture’s obsession with its own memory into consideration, such aspects become specifically relevant in the context of retro marketing and past-themed consumption (Brown, Kozinets, and Sherry Citation2003).

The emerging stream of marketing and consumer research that has already employed hauntology as a theoretical framework has focused either on the apparent death of retailing (Brown, Patterson, and Ashman Citation2020) or late capitalism’s persistent recycling of retro aesthetics (Ahlberg, Hietanen, and Soila Citation2021). However, Derrida (Citation2012) emphasizes that there are many specters (of Marx). An underexplored research avenue is the relation between hauntology and collective guilt (after all, one of the book’s subtitles is The State of the Debt). As Gordon (Citation2008) reminds us,

the ghost is not simply a dead or a missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life … being haunted draws us affectively, sometimes against our will and always a bit magically, into the structure of feeling of a reality we come to experience, not as cold knowledge, but as a transformative recognition (8).

Akin to Gordon (Citation2008) above, Derrida’s reflections on spectrality suggests a productive and responsible way of engaging with postcolonial histories and ethnic oppression. The book initiated an ethical turn in Derrida’s work (Salmon Citation2021). Specifically, Derrida (Citation2012) is writing about ethical responsibility toward others across time where the possibility of a just future depends on our “ability to live with ghosts” (xviii, italics in original). Significantly for Derrida (Citation2012), the specter is always both revenant (i.e. returning from the past) and arrivant (i.e. inhabiting the present with the spirit of the “future-to-come” [p. 19]). The temporal disjunction between specters and spirits provides a useful framework for studying how the relation between myth and ideology shapes experiences of nostalgia in past-themed consumption.

Research procedure

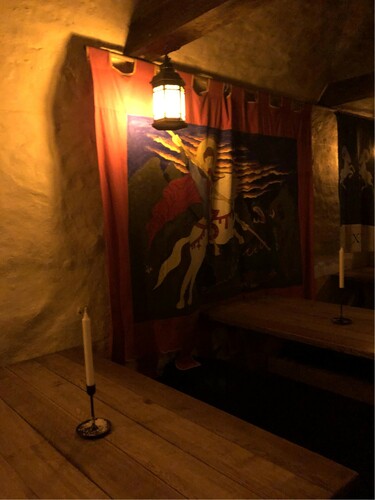

To select cases, the scope of this research project was limited to a Viking-themed restaurant in Sweden. The interviews have all been conducted on site at Sjätte Tunnan, a medieval cellar in the old town area of Stockholm (). The old town is generally considered a touristic epicenter and, dating back to the thirteenth century, its architecture consists of medieval alleyways, cobbled streets, and archaic architecture.

Figure 1. Photo of the medieval interior taken by the author during one of the visits to Sjätte Tunnan.

The restaurant itself is advertised as a time travel.Footnote3 Furthermore, taking its association to Viking mythos into consideration, it provides a considerably useful context for studying linkages between nostalgia marketing and stimuli to authenticate from which the specter makes its appearance. Although the clientele to some extent consists of tourists, and the interior of the restaurant therefore could be seen as front stage using MacCannell’s (Citation1973) terminology, it is also a popular water hole for locals who thirst for medieval history while having something to eat or drink. In comparison with Aifur, a competing Viking-themed restaurant in the neighborhood, however, the clientele at Sjätte Tunnan seems less playful, more historical and constative in the sense that the spectacle is typically de-emphasized in favor of more serious historical re-enactment. As such, the research site allowed me to focus on the enclave of “woke” Vikings rather than, for example, tourists for whom the Viking myth is a part of their Stockholm trip or mainstream consumers who do not usually take an interest in Vikings but nevertheless dress up in horned helmets during football games as a signifier of their Scandinavian identity.

Interviews were conducted with twelve volunteer informants ranging in age from twenty-one to fifty-two. I selected informants on the basis of their previous experience with Viking-themed consumption ranging from occasional visitors who merely visit the pub for fun to regulars who also partake in role playing activities and engage in blót (i.e. the term for “sacrifice” in Norse paganism) rituals. Vikings are predominantly associated with males. Thus, informants comprised a purposive sample of consumers drawn from the broader population of Viking enthusiasts within Sweden. In other words, the inclusion of two female informants roughly reflects the gender division among visitors to Sjätte Tunnan.

I have no personal experience of Viking mythology but classify myself as a novice who has only visited Sjätte Tunnan and other Viking-themed restaurants for enjoyment. As such, the researcher cannot be classified as a member of the target population (Wallendorf and Brucks Citation1993). While running a series of film screenings in Stockholm during the summer of 2019, I was introduced to Ella, a Viking enthusiast who provided contact details to other members of her roleplaying group. Thus, I interviewed Samuel who is the leader of a group of friends who regularly get together to play the fantasy game Trudvang ChroniclesFootnote4 that takes place in a Viking-inspired world. Four of the informants were recruited from this group. Other informants were recruited through Facebook groups about medieval fairs, the Swedish Forn Sed AssemblyFootnote5, and informal visits to the Viking-themed tavern in question. I contacted informants in person, by phone, or e-mail. I did not discuss informant identities with other informants, even when interviewing people from the same roleplaying group or blót team. displays informant information. The French informant was a Swedish citizen who had lived in Stockholm for the last year.

Table 1. List of informants.

Ahead of the interviews, I engaged in informal conversations with members of the staff at Sjätte Tunnan. As a final step, two additional informants partaking in the commercial mythmaking of Vikings were interviewed. Most informants were recruited prior to settling for the site of location. Nostalgia is deeply connected to sensual stimuli. The presences and practices of smell constitute an often-ignored sensory feature of market and consumption spaces (Canniford, Riach, and Hill Citation2018). Therefore on-site interviews were conducted. This allowed informants to emphasize scents, tastes, background music, and other sensual aspects of the atmosphere that spontaneously could draw them back in time in a form of fantasy or make-believe. The interviews lasted up to two hours. I sought out cases that allowed me to investigate tension between mythic structure and ideological disconformity, as well as how consumers elicit different types of nostalgia to authenticate their consumption fantasies. This allowed me to analyze how nostalgia in various ways connects to authenticating elements in consumers’ lived experiences.

Following McCracken’s (Citation1988) procedure for long interviews, I asked a mix of grand tour questions and floating prompts. At the beginning of each interview, informants were asked to think about Viking-themed consumption. Since the informants would often approach this question with personal stories or experiences, further prompts were used to understand the significance of such events. Following a general discussion of nostalgic experiences, I also focused on its relation to mythological dynamics and collective identity. Informants were asked to discuss different commodities they felt a deep connection to and whether they considered them nostalgic or authentic. Informants selected these from their own experience. Occasionally the informants would struggle to define the concepts, in some cases they altered their view during the interview in a spirit of joint discovery and critical reflexivity. As noted by Beverland and Farrelly (Citation2010), such enrichment occurs due to availability of prompts and noninvasive interview procedure. I also tried to make the informants relax as they told their stories. Given the semistructured interview format, informants were often asked to elaborate on various statements they made regarding their personal experiences, hence informants spoke for most of the interview (Thompson, Locander, and Pollio Citation1989).

Already from an initial scanning of the cases, it emerged that more or less all informants in various ways had a nostalgia-elicited imperative to legitimize their consumption fantasies as mediated by Viking mythos. Yet these imperatives were often haunted by counter memories and inscriptions in a present-day ideological zeitgeist. Finally, the interpretive step of analysis involved linking consumption practices to social-historical forces that shape the way people consume in order to extend the theories that previously have been developed on nostalgia and its shadow components (Burawoy Citation1998). In analyzing the transcripts, there was a focus on classifying the links between nostalgia and collective guilt. Closely reading the textual data, it appeared that these hauntings were symbolically transferred to the consumption activities. At this point, theoretical categories were elaborated through open and axial coding procedures. Then began a process of dialectical tacking, moving back and forth between the findings and relevant literature on the nature of nostalgia to deepen our understanding of the processes by which collective guilt becomes a haunting specter (Spiggle Citation1994).

Consuming the Viking myth and its “woke” counter memories

Medieval references have a special place in popular culture (Dagalp, Brunk, and Hartmann Citation2020; O’Neill, Houtman, and Aupers Citation2014; Stern Citation1988). The aesthetics of the Middle Ages—which spanned from the 5th to the fifteenth century—have worked their way into different corners of the cultural industries. For the current generation, heroic images of Vikings have been shaped and mass mediated by films and television series (e.g. Game of Thrones, The Lord of the Rings, Vikings), along with video games (e.g. Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, Skyrim) and folkloric stories about Vikings such as Beowulf and the paintings by John Bauer. Thus, Samuel (male, age twenty-three) who is currently studying for a master’s degree in medieval history, spending his leisure time organizing game nights based on the fantasy game Trudvang Chronicles, elaborates.

This video game [Skyrim] has played a big part in initiating the recent phase of Vikings that we’ve seen in popular culture. It’s inspired by Norse mythology but takes place in a fantasy setting. They drink mead, they’re warriors … In this fantasyland called Skyrim, the local beverage is mead. Everyone’s drinking mead. There are mead breweries you can enter and look inside, there are people in the wilderness offering you mead. This happened before I’d even tasted mead myself, which created a certain curiosity for what mead tastes like. (Samuel)

This passage shows the widespread commodification of Viking aesthetics. To authenticate or suspend disbelief, it seems to suffice if the consumer can make a connection to images in popular culture (Södergren Citation2019). Viking mythos have also entered the world wide web. In 2000, the Techno Viking became an internet phenomenon (a so-called “meme”) based on a video from the Fuckparade in Berlin (https://youtu.be/UjCdB5p2v0Y). More recently people have started uploading medieval covers of modern pop-songs onto YouTube getting millions of streams (Yalcinkaya Citation2020). The “bardcore” trend finds creators reworking mainstream hits using lutes, fiddles and harps as well as rewriting lyrics in old-timey language. As Borgerson and Schroeder (Citation2002) have shown us, “much of the ideological power of the representations discussed here lies in their almost infinite repetition—similar images are presented over and over again in a wide variety of marketing contexts and epochs” (580). In this manner, Vikings have become the “ludic raw material” for hedonic playwork (Hartmann and Brunk Citation2019, 7) providing “the raw materials for contemporary fantasy construction” (Belk and Costa Citation1998, 220). As the restaurant owner Blaise points out, most visitors already have a mental preconception that if they go to Sjätte Tunnan they should drink like a Viking. However, the spectacle does not fall far from the specter.

Unlike Belk and Costa’s (Citation1998) mountain men for whom the utopian consumption fantasy seemed to alleviate any ethical issues whatsoever, for the informants in my study the Viking myth raises a number of critical concerns based on dualisms such as victimizer vs. victim, dominant vs. subordinate, to name a few. This is indicated by the following vignette.

You can imagine a past that was much better but actually never existed which freaks me out a bit. Popular culture often flirts with that imagination. Of course I know that it never existed, but I’ve been here and seen people sitting by the table next to me who obviously have been part of some Nazi community. You know they’ll be here, far-right nationalists take an interest in these sorts of things. At the same time I have this feeling that I don’t want to let go of [the Viking myth] and let them have it. It would be a shame if we would let them have it. (Samuel)

While racism is not the focal point of this study—and I do not wish to trivialize the many tragedies that members of the black population still face on a regular basis by pushing it to the realm of memory—nostalgia and nationalist mythologies are often intertwined (Derrida Citation2001). This reveals a sinister side of nostalgia.Footnote6 Indeed, while relics (i.e. genuine antiques from the Viking age), reproductions (i.e. contemporary copies of the original where more or less the same ingredients are used), revivals (i.e. products that are not only brought back but are given a facelift such as chili-flavored mead), and replicants (i.e. completely new products that are made to look old) are useful to denote the authenticity of a nostalgic consumption experience in spatio-temporal terms, a fifth R could be added to Brown’s (Citation2018) typology—the revenant. Enter the specter.

The Viking myth serves as a ludic raw material for hedonic playwork, but it is also “a journey into unimaginable barbarism” (Walchester Citation2018). The Viking reputation is of “bloodthirsty seafaring warriors” (Richards Citation2005) and the Viking myth has been misappropriated by white supremacists such as the ones Samuel mentions above. He feels possessive about the myth (“I don’t want to … let them have it”) but he cannot escape the itchy feeling of collective guilt. All these elements coalesce into a process by which the consumption activity as the embodiment of the myth transforms into a haunting specter (and that is not just the mead talking). What we can conclude from this is that nostalgia does not transport consumers “back to a time when they were safe and happy and cared for” (Brown Citation2018, 10) quite as unproblematically as previously has been suggested (e.g. Belk and Costa Citation1998). In this case, the Viking myth, which, for instance, is manifested in the consumption of mead, is neither relic nor replicant but revenant.

Moreover, the Viking myth is associated with strength and masculinity as lamented by Denis (male, age thirty-five).

I’ve been working on a project with some Swiss colleagues and we became friendly with each other. Every time I was freezing, one of them would say “Come on, you’re a Viking,” whereby I would respond “Even the Vikings were freezing when it was cold!” The cultural meaning of Vikings never goes any deeper than this simplistic idea of tough, blond men. I’m actually interested in learning about what it was living back then, it wasn’t all fun and games. The only thing that’s survived is this imagination of horned helmets—which didn’t even exist! And then of course, this whole association with white supremacy doesn’t make my life any easier. (Denis)

Many—if not all—of the informants in this study consider themselves as feminists and try to resist dominant ideologies in which Vikings are thought to invoke masculine identity myths (Holt and Thompson Citation2004). As Gordon (Citation2008) discusses, “those who haunt our dominant institutions and their systems of value are haunted too” (5). Derrida (Citation2012) calls attention to the specter as something that “belongs to the structure of every hegemony” (46). Thompson and Tian (Citation2008) similarly assert, “the hegemonic construction of popular memory will also selectively omit conflicting perspectives and historical details that would otherwise threaten the dominant group’s self-affirming vision of the past” (596). Derridean hauntology helps us illustrate how these excluded histories can come back to unsettle the consumer. Spooky.

Reluctantly taking the symbolic position of victimizer/dominant, it would appear that the Viking archetype becomes a haunting specter through the collectivization of guilt. This is in line with contemporary, entwined public discourse concerning gender and race as my informants are quick to take a stand against racism and sexism. Sobande (Citation2019) refers to this ideological formation as “woke” bravery. More precisely, she defines “woke” bravery as a form of social capital attached to individuals who are invested in challenging structural injustices faced by the most marginalized groups in society. The term “woke” became a watchword in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter and has evolved into a single-word summation of leftist political ideology, centered on social justice politics and critical race theory. It is used as a shorthand for political progressiveness by the left whereas the right usually refers to it sarcastically as political correctness gone awry. Viking mythology and “woke” bravery might at first glance seem like odd bedfellows, but such mythological tension (and ideological disconformity) is present throughout the interviews and serves as a vessel for collective guilt.

In total, three “woke” counter memories to the Viking as a romantic hero emerged from the data. These were based on: (a) nationalism on the rise and the normalization of far-right populism, (b) recent waves of feminism such as the #MeToo movement, raising issues of toxic masculinity, and (c) the decolonization of indigenous SámiFootnote7 culture that is often written out of hegemonic Swedish memory making (de Bernardi Citation2019). These issues of social injustice need to be resolved in order for an enchanted experience to be obtained from the Viking myth. In short, “woke” counter memories can cause an ideological disruption from which mythological tension gives rise to what I next will define as the haunted imagination ().

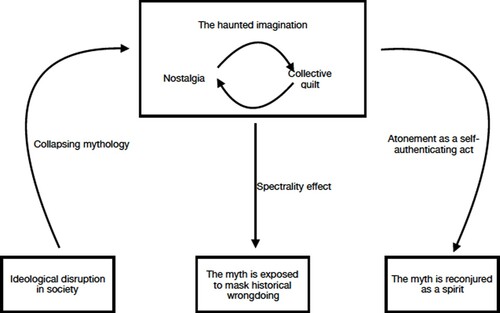

Holt (Citation2004) has written at length about the ideological disruption of myth-markets in his case study of iconic brands. Torn between (1) ideological disruption caused by “woke” bravery and (2) collapsing Viking mythology, (3) the haunted imagination is animated by tension between nostalgia and collective guilt. Its (4) spectrality effects include the resurrection of painful memories and historical wrongdoing, which may discomfort consumers’ identity projects in the present. Hence, Ella (female, age twenty-one) sought to protect her identity investment by devaluing the Viking myth, stating “it’s a universal, mythic nostalgia. You can play on grand emotions … but besides that, this Norse pantheon isn’t particularly something I identify with.” However, as indicated by the final step of the model, findings indicate that consumers may also employ (5) atonement as a self-authenticating act (e.g. “it’s actually common … that someone toasts for the bees and their threatened situation today”). In doing so, specters can be reconjured into spirits. In other words, following Derridean hauntology, nostalgia encapsulates both specters of the past and spirits with their promise of utopian elements to arrive from the future. Extant marketing and consumer research has largely focused on the latter.

The haunted imagination

The haunted imagination signifies a process by which the specter makes its appearance through the collectivization of guilt. While the Viking myth encapsulates a set of values that allows the consumer to “escape from the rules, contraptions, and stresses of daily life in the city” (Belk and Costa Citation1998, 234), the consumption fantasy may also be a vessel for spectrality, for example, if the consumer’s identity project is existentially anchored in a system of ideological beliefs in which the mythic structure is no longer canonized as being inherently virtuous. The haunted subject can, for example, feel obliged to a sense of moral responsibility. Thus, contrary to the patriot Hummer drivers in Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler (Citation2010) for whom responsibility is negotiated by framing themselves as “caretakers of the American frontier” which “echoes the pioneer spirit canonized by the ideology of American exceptionality” (1027), the “woke” Vikings in the present study do not necessarily seek to dramatize ideological differences as much as resolve mythological tensions that emerge from their own emic encounters with ideological disconformity. Thus, Peter (male, age forty-six) saw Vikings (in general) and mead (in particular) as symbols that could bring different mythological formations closer together.

If you look at old customs, there’s co-operation. The noaidi shamans interacted with northern culture … If I were to make any kind of association with mead, I would rather see its potential for reconciliation. I see the potential to use it as a ritual and ceremonial drink linked to reconciliation and union. (Peter)

Although the various conflicts invigorated by the mythic structure of the moral protagonist to some extent is present among my informants, not least when they distance themselves from the framing of white supremacists as moral antagonists whom they believe have misappropriated the Viking myth, this is typically de-emphasized rather than dramatized. Consider the following interview excerpt.

It’s a political game and nothing else … In the nineteenth century, the nationalist movement grew stronger and realized, “We’re just pets of another bigger state, we don’t want to be that.” That’s when all this bullshit was invented, because they did not understand the myths. They wanted to understand in order to reproduce a strong cultural identity—racism was present for sure. Those romantic nineteenth century images and reimaginations are a burden to this day. Today if you’re heathen, people believe that you’re part of the Soldiers of Odin—and they have a very Christian imagination of paganism. [Contrives his voice] “Urgh, I’m Thor and I’m going to beat them up.” That’s not at all what it’s about. Both Christians and Nazis, whatever, stand in the way for an authentic understanding of what paganism is about. (Ronny)

As the excerpt conveys, mythological tension and ideological disconformity may give rise to spectrality effects. This is because feelings of nostalgia—as manifested in the Viking myth as a signifier of pastness—are in conflict with collective guilt, in this case guilt by association to white supremacists. What I call the haunted imagination is animated by this tension. It is somewhat remarkable that the term “spirit” is used fourteen times by Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler (Citation2010) while “specter” only appears once in their paper. In fact, what distinguishes American Hummer drivers from the “woke” Vikings in this study is the affective role of specters in the formation of the haunted imagination. This is itself the result of discrepancy between myth and ideology, where the specter makes its appearance as an obstacle to a more forward-looking or utopian spirit. For instance, whereas the mythic formulation of the moral protagonist (vs. the moral antagonist) is actively employed by Hummer drivers to legitimize their consumption ideology, thus providing a sense of moral superiority in their identity work, such dualism is less prominent among the enclave of “woke” Vikings. If anything, in Luedickean terms, “woke” Vikings could metaphorically be compared with tree huggers or environmentalists who drive Hummers while reflecting over their own latent identity positions as moral antagonists. Thus, Denis articulates his thoughts on toxic masculinity and anti-semitism which, for him, is one of the spectral connotations of Viking mythos.

My dad’s Jewish, he’s from Israel, thus my brother had a difficult time in school. He was bullied by the boys who went on to form the National Youth, the neo-Nazis … Just take this Tough Viking competition as an example—you’re supposed to be tough as a Viking. Now I’m not part of this culture whatsoever, but I can see from the outside that men are portrayed as overtly masculine. You have to be tough and that’s a problem. It’s a prison for many men that I could’ve had a friendly relationship with. It’s a wall, you’re supposed to be tough. (Denis)

If myths indeed are made for the imagination to breathe life into them, normative understandings of nostalgia have reiterated an all too sanguine conception of consumer myth-making. But as Denis’s narrative conveys, consumer imagination can also be haunted, for example, if the mythic structure encapsulates racism or toxic masculinity disconfirming the subject’s own ideological beliefs. Returning to , the haunted imagination could thus be defined as the process by which nostalgia is affectively transformed into collective guilt, where the weight of the past appears as a haunting specter.

Atonement as a self-authenticating act

The haunted imagination gives rise to spectrality effects as mediated by collective guilt. This potentially undermines the authenticity derived from the Viking myth as a nostalgic signifier of pastness. In the context of nostalgia and cultural memory, authenticity is said to be imbued into consumer objects through the processes of resistance, homecoming, and educating (DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin Citation2019). To this end, Peter stresses the importance of educating the mainstream beyond the typical frame of the Viking as a masculine archetype. Indeed, for most people the Viking myth is heavily informed by contemporary media portrayals of Vikings which all too often overlook ideologically more spirited values such as environmentalism and (surprisingly) progressive gender roles.

Do you associate mead to anything beside the Viking Age?

I make the connection to bees and their situation today. It’s actually common during blót rituals that someone toasts for the bees and their threatened situation today, that someone proposes a toast for the bees and their future.

Are there any other values in Viking mythology that you see in present life?

The myths often address the Gods’ mistakes. Let’s use the myth of Thor as an example, when he’s about to catch the Jörmungandr [the Midgård Serpent]. Thor encapsulates this masculinity ideal that’s usually associated with the Vikings. But we also see how the myth questions this archetype by poking fun at him when he dresses up as Freyja. The myth challenges the image of masculinity, it ridicules the stereotypical image of the Viking as masculine hero.

Although authenticating processes of resistance, homecoming, and educating were present among my informants, they miss out on one crucial element; atonement as a self-authenticating act. Contrary to DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin’s (Citation2019) diaspora consumers who “celebrate long-lost histories and traditions following … collective identity disruptions” (5) for whom it is “like an inner spirit kind of thing” (12) to dress up in clothing that remind them of their ancestral homes, the mythic image of the Viking as a masculine hero is haunted by various spectralities invigorated by ideological disconformity (e.g. white supremacy, toxic masculinity, postcolonial guilt). Thus, by employing atonement as a self-authenticating act, my informants reveal how haunting specters purposely can be reconjured to encapsulate a more spirited apparition.

Consider, for example, the Viking Beard Club (@vikingbeardclub on Instagram) which takes a stand on numerous sociopolitical issues (e.g. to stop violence against women) to atone for the hegemonic image of the Viking as a masculine (wife-beating) archetype. Peter’s remarks illustrate this practice.

In 2006, I was invited to a conference in India as a representative for the Assembly of Forn Sed Sweden. In total, thirty-forty religions were represented ranging from Indian tribes to Mayan Indians. We gathered for a weeklong conference and each morning we tried out a different ceremony. Different cultures showcased and participated in each other’s ceremonies. It was so obvious, for some it was a seashell that was passed on, it was either a beverage or a pipe that was passed on in circles. We had the horn that went around. Even if the others didn’t use mead, I had such a strong feeling that we were all doing the same thing. A ninety year-old shaman who had lived isolated in a village in North India could immediately recognize the different steps of blót. Mead had its parallel in almost all ceremonies. Then I got this idea of mead as a means of bridge-building. Rather than the stereotypical image of the Viking conqueror who drinks mead, I regard it as something that can reconcile and unite people. (Peter)

Rather than reiterating the spectrality of Vikings as barbaric conquerors, Peter seeks to restitute this image (e.g. “I regard it as something that can reconcile and unite people”). In line with this, atonement could be seen as a self-authenticating practice in which spectral signifiers (i.e. antecedents to collective guilt) are endowed with ideological meanings that support their “woke” bravery. Mead and Baldwin (Citation1971) describe atonement as useful guilt. In Peter’s case, atonement involves challenging nationalist mythologies and patriarchal or transphobic (“Odin could be viewed as a queer god”) assumptions in the prevailing normative order. Hence, it would seem that atonement enables Peter to reconjure the haunting specter (e.g. collective guilt) invigorated by ideological disconformity (e.g. toxic masculinity) into a spirit encapsulating qualities that he believes are missing in contemporary urban life (e.g. enchantment, close-knit community). As noted by DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin (Citation2019), “authenticating possessions may serve purposes such as investigating one’s heritage, reconstructing a group identity, restoring a sense of historical continuity, or contesting stigmatized representations” (4). The latter is certainly accurate for my informants who feel that too stereotypical media portrayals of the Vikings as masculine heroes, patriots, or colonizers can devalue their identity investments.

So what distinguishes the specter from its spirit? Romantic memories could conjure both spectral and spirited apparitions (see ). Albeit an approximation, the spectral is when the individual is haunted by negative emotions such as collective guilt or anxiety of a life unfulfilled, whereas the spirit provides a temporary connection to the utopia signified by the commodity, and is therefore experienced with less reluctance and more optimistic emotions. Celebration, for example, always corresponds to an exaltation of the spiritual (Derrida Citation1989). For Denis, the spiritual dimension is posited in his creativity. For example, at one point during the interview Denis is distracted by the bagpipes playing in the background because he recently picked up the instrument himself, and is trying to learn how to play the same song. Ella is haunted by the specter of her repressed childhood years (“I was embarrassed about who I’d been before, I think this constant shame made me … I’d rather look to the future”) but managed to connect spiritually to the past when she felt as if she was partaking in a grand drama. Similarly, Ramona had a spectral association to olde-worlde commodities such as opium (which “the Victorians loved and utilized to colonize Malayans”) and absinthe (which she associates with debauchery and “putting French poets on the street”) whereas she could authenticate mead because it encompassed “a pure, wholesome” spirit of the sagas.

In short, just because a commodity such as a retro brand or heritage attraction revives the past does not necessarily mean that it is endowed with authenticity (Brown Citation2018). The specter—spirit relation derived from Derridean hauntology and further unpacked in this study is useful to elucidate how nostalgia can elicit and set various authenticating/de-authenticating elements in motion. This is because the mythic past may simultaneously be a vessel for nostalgia and spectrality. For example, some mythic structures and counter memories were problematic because they exposed the consumer to spectral elements in the past. Hence, present findings support the proposition that nostalgia mediates authenticity through haunting and mythological dynamics. More precisely, by studying how the relation between the Viking myth and the ideology of “woke” bravery shapes experiences of nostalgia in the context of past-themed consumption, it is possible to explicate the hauntology of collective guilt. If “haunting” according to Derrida (Citation2012) “belongs to the structure of every hegemony” (46), the “spirit can do nothing other than affirm itself—and this, as we shall hear, in the movement of an authentication” (Derrida Citation1989, 464).

General discussion

This article engages with conversations around nostalgia and one of its hauntological dimensions: collective guilt. Aimed at scrutinizing how the relation between myth and ideology shapes experiences of nostalgia in past-themed consumption, this study has explored how the Viking myth serves simultaneously as a vessel for nostalgia and spectrality among the alternative enclave of “woke” Vikings in Stockholm. In doing so, the article first contributes to the literature on commercial myth-making, enlightening issues related to ideology and consumer moralism which are central to the collectivization of guilt (Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler Citation2010). More precisely, I examine how ideas of the past can function as part of consumption fantasies and imaginations. However, rather than looking at the sentimental or nostalgic aspects of these myths (Belk and Costa Citation1998; Brunk, Giesler, and Hartmann Citation2018), I theorize their hauntological underpinnings, including the collectivization of guilt. Derrida’s (Citation2012) concept of hauntology has been criticized for its ambiguity (see Sprinker Citation1999) but serves here as a gateway from nostalgia to theories of collective guilt and atonement. Specifically, it is useful for investigating those fears and anxieties that exist in dialogue with consumer fantasies (Holbrook and Hirschman Citation1982), which are often written out of the literature on ludic consumption.

Second, this investigation reveals how consumers seek to protect their identity investments, for example, if their identity projects are existentially anchored in a system of ideological beliefs (e.g. “woke” bravery) in which the mythic structure (e.g. the Viking myth) is no longer canonized as being inherently virtuous. However, instead of relying on the mythic structure to dramatize ideological differences akin to patriot Hummer drivers—whose identity work attains a moralistic quality by “mobilizing particular mythic structures rather than reiterating any specific ideological content” (Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler Citation2010, 1028)—my informants seek reconciliation and truce (e.g. “rather than the stereotypical image of the Viking conqueror who drinks mead, I regard it as something that can reconcile and unite people”). I see this as the primary contribution of the research. It elaborates the notion that the evocation of a mythic or romantic past is employed to authenticate consumer experiences, complementing it with collective guilt. For example, my informants do not necessarily seem to believe that the Vikings epitomize what is desirable and worthy of emulation in life, yet the Viking myth serves as a source of consolidation that an enchanted experience can still be redeemed. Moreover, in the context of Viking-themed consumption, the “braggadocio” discussed by Belk and Costa (Citation1998, 221) could even serve as a source of shame, potentially undermining the symbolic or moral authenticity derived from the mythic past.

Hence, I more broadly extend the literature on nostalgia by explicating its relation to collective guilt. The concept of the haunted imagination is introduced to describe the process by which feelings of nostalgia are disrupted by mythological tension and ideological disconformity, such as when the Viking myth is reimagined in the ideological context of “woke” bravery. Sobande (Citation2019) notes that “woke” became an Oxford English Dictionary entry in 2017. Previous research has studied how “wokeness” has been operationalized by marketers and how brands attempt to tap into public discourse concerning “wokeness” to leverage “woke” credentials and legitimacy (Vredenburg et al. Citation2020). This article illustrates how consumers themselves engage in expressions of “wokeness” in the marketplace. I focus on the doubleness of collective memory, on feelings about the past that combine nostalgia with collective guilt. Thus, the “woke” Vikings in this study illuminates the affective role of specters and spirits as a significant way of understanding consumer meaning-making in the evocation of the mythic past.

Finally, the study extends the literature on the consumer quest for authenticity (Beverland and Farrelly Citation2010; DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin Citation2019; Södergren Citation2021) by identifying the notion of atonement as a self-authenticating act. In encounters with myths that are exposed to mask a perverted or problematic past (e.g. colonial history and wrongdoing), findings suggest that consumers can reconjure specters into spirits through self-authenticating acts of atonement. A theoretical recognition of consumer spirituality has already started to gain strength (Husemann and Eckhardt Citation2019; Rinallo, Scott, and Maclaran Citation2012). As Derrida (Citation2012) has demonstrated, we have to think of the spirit as something that becomes attainable by our ability to live with ghosts. However, it would seem that the specter evoked by collective guilt is closer to some sort of “bad conscience” than actual remorse, where the symbolic position as victimizer is exaggerated by ideological tension. Sjätte Tunnan could be seen as a “theatrical space in which the grand forgiveness, the grand scene of repentance which we are concerned with, is placed, sincerely or not” (Derrida Citation2001, 28). Derrida (Citation2001) continues,

each time forgiveness is at the service of a finality, be it noble and spiritual (atonement or redemption, reconciliation, salvation), each time that it aims to re-establish a normality (social, national, political, psychological) by a work of mourning, by some therapy or ecology of memory, then the “forgiveness” is not pure (31-32).

Conclusion and suggestions for future research

This work builds upon Belk and Costa’s (Citation1998) detailed writing on the evocation of the mythic past in nostalgic consumption, Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler’s (Citation2010) vital analysis of how myth and ideology animate moral conflict, and DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin’s (Citation2019) rigorous research regarding history and authenticity. It is notably shaped by Brown’s (Citation2018) prolific work on retro. This paper also contributes to ongoing consumer culture work dedicated “to unpack the role of commercial mythmaking in the resurgence of nationalism” (Brunk, Giesler, and Hartmann Citation2018, 1340) in a time when nationalism is on the rise.

Spectrality seeks less to take the place of other approaches of studying nostalgia and the evocation of mythic past than to supplement them with a twilight zone, thus elucidating the authentication of various cultural objects, histories, and sociopolitical issues. At a general level, haunting and spectrality could be seen as something that per Derridean hauntology is inherent to being. Potential avenues for further research include studying how Viking mythology has taken on a life outside the Scandinavian market where the colonies of New Sweden in the United States could serve as a rich empirical context.Footnote8 Does the two-ness of being Swedish-American inform the quest for heritage and the authenticating practices in which consumers engage similar to the double consciousness felt by the African-American informants in DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin’s (Citation2019) study—or does it reinvigorate feelings of collective guilt as for the “woke” Vikings in this study?

Opportunities for further research also present themselves around the continuous oppression and ethnostress of the indiginous Sámi people who were only touched upon briefly in this article. As Mead and Baldwin (Citation1971) remind us, “in any oppressive situation both groups suffer, the oppressors and the oppressed. The oppressed suffer physically; they are frightened, they are abused, they are poor. But the oppressors suffer morally” (33). In order to facilitate atonement and arrive at a form of double liberation, morally scarred oppressors must begin to understand the past and its inscription in the present (Mead and Baldwin Citation1971). How will, for example, the planned Arctic Railway linking the Norwegian Arctic port of Kirkenes with the Finnish railway network damage their lands? Testimonies from older Sámi or descendants of those who experienced the trauma of forced migration in the 1920s and 1930s could possibly provide rich data (see, e.g. Labba Citation2020).

Furthermore, as Derrida (Citation1993) points out, “neither the language nor the process of this analysis of death is possible without the Christian experience” (80). Other prospects thus include the trespassing of national or cultural borders to sketch the hauntology of other mytho-ideological consumption contexts, such as Shinto where spirits (kami) and phantoms (yōkai) are typically perceived as elements of the landscape or forces of nature that possess both good and evil characteristics, Arabian mythos where genies (Jinni) are haunting-demons of the wilderness that are thought to be extremely dangerous to unprotected persons, or Haitian vodou which has come to represent black magic when it appears in popular culture, where zombies and ghouls are part of the mythology (Toussaint-Strauss Citation2020). Projects as such would respond to recent calls to study authenticity beyond the customary frame of western-centric perspectives (DeBerry-Spence and Izberk-Bilgin Citation2019; Ozanne and Appau Citation2019; Södergren Citation2021).

Another worthwhile avenue for future research would be to explore hauntological elements in cancel culture, i.e. when people stop giving support to public figures and companies after they have done or said something considered objectionable or offensive. Consider the Harry Potter brand which Brown (Citation2018) describes as “a child of the retro boom” (21). Studying how fans reconcile transphobic comments by its author J.K. Rowling with their love for the brand could provide rich insights to the dynamic between nostalgia disruption and collective guilt.

At some point in time, history changes into an oversimplification, a myth that leaves out unpleasant memories. Here is the crux: to take responsibility for the past, one has to also embrace its ghosts. Rather than chasing them away, Derrida (Citation2012, 220) proposes that we grant them “a hospitable memory … out of a concern for justice.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonatan Södergren

Jonatan Södergren holds a PhD in Business Administration from Stockholm University. He believes in ghosts and is mainly interested in using literary theory to study consumption phenomena.

Notes

1 Derrida (Citation1995, 8) himself describes nostalgia as “the-shining-eyes-that-unhooked-the-child-too-soon-from-its-mother.”

2 Briggs (Citation1977) argues that the contemporary ghost story, through its reassuring formula, “has become a vessel for nostalgia” (p. 14).

3 For a virtual tour of Sjätte Tunnan, please visit their webpage (https://www.sjattetunnan.se/vara-lokaler?lang=en).

4 In Norse mythology, Þrúðvangr are the fields where the god Thor is thought to reside.

5 The Swedish Forn Sed Assembly is one of the most important heathen organizations in Sweden with more than 500 members.

6 Consider, for example, Sainsbury”s recent Christmas ad (https://youtu.be/GqtcpLywgRU). As Holak and Havlena (Citation1992) point out, the celebration of Christmas is our most nostalgic tradition. Featuring heartwarming home footage of a black family celebrating Christmas, Sainsbury”s ad was certainly in line with the holiday season”s festive sentimentality. Yet, it was met with a number of racist responses in line with: “I”m dreaming of a WHITE Christmas,” “Christmas in Nigeria,” and “You may as well rename yourself Blackbury”s!” (Young Citation2020).

7 The Sámi are a Finno-Ugric people inhabiting large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, and Finland as well as the Murmansk Oblast of Russia. They lived in coexistence with the Vikings whom they had a mutually symbiotic relationship with. Today, however, the Sámi are largely left out of hegemonic Swedish memory in favor of the Vikings.

8 Sweden established colonies in the Americas in the mid-17th century including the colony of New Sweden (1638–1655) on the Delaware River. Today, Swedish Americans primarily include the 1.2 million Swedish immigrants during 1885–1915 and their descendants. They are most prevalent in the Midwest with Minnesota being the state with the highest number of Swedish-Americans (their local football team is called Minnesota Vikings).

References

- Ahlberg, Oscar, Joel Hietanen, and Tuomas Soila. 2021. “The Haunting Specter of Retro Consumption.” Marketing Theory 21 (2): 157–175.

- Antonetti, Paolo, and Paul Baines. 2015. “Guilt in Marketing Research: An Elicitation–Consumption Perspective and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Management Reviews 17 (3): 333–355.

- Arendt, Hannah. 1968. “Collective Responsibility.” in Responsibility and Judgment. New York: Schocken Books.

- Baker, Stacey Menzel, and Patricia Kennedy. 1994. “Death by Nostalgia: A Diagnosis of Context-Specific Cases.” ACR North American Advances.

- Baker, Stacey Menzel, Carol Motley, and Geraldine Henderson. 2004. “From Despicable to Collectible: The Evolution of Collective Memories for and the Value of Black Advertising Memorabilia.” Journal of Advertising 33 (3): 37–50.

- Belk, Russell. 1990. “The Role of Possessions in Constructing and Maintaining a Sense of Past.” Advances in Consumer Research 17: 669–676.

- Belk, Russell. 2013. “The Sacred in Consumer Culture.” In Consumption and Spirituality, edited by Diego Rinallo, Linda Scott, and Pauline Maclaran, 69–81. New York: Routledge.

- Belk, Russell, and Janeen Arnold Costa. 1998. “The Mountain man Myth: A Contemporary Consuming Fantasy.” Journal of Consumer Research 25 (3): 218–240.

- Belk, Russell, and Gülnur Tumbat. 2005. “The Cult of Macintosh.” Consumption Markets & Culture 8 (3): 205–217.

- Beverland, Michael, and Francis Farrelly. 2010. “The Quest for Authenticity in Consumption: Consumers’ Purposive Choice of Authentic Cues to Shape Experienced Outcomes.” Journal of Consumer Research 36 (5): 838–856.

- Borgerson, Janet, and Jonathan Schroeder. 2002. “Ethical Issues of Global Marketing: Avoiding bad Faith in Visual Representation.” European Journal of Marketing 36 (5-6): 570–594.

- Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

- Bradshaw, Alan, James Fitchett, and Joel Hietanen. 2020. “Dystopia and Quarantined Markets: An Interview with James Fitchett.” Consumption Markets & Culture 24 (6): 517–525.

- Bradshaw, Alan, and Morris Holbrook. 2007. “Remembering Chet: Theorizing the Mythology of the Self-Destructive Bohemian Artist as Self-Producer and Self-Consumer in the Market for Romanticism.” Marketing Theory 7 (2): 115–136.

- Briggs, Julia. 1977. Night Visitors: The Rise and Fall of the English Ghost Story. London: Faber.

- Brown, Stephen. 1999. “Retro-Marketing: Yesterday’s Tomorrows, Today!.” Marketing Intelligence and Planning 17 (7): 363–376.

- Brown, Stephen. 2001. Marketing - The Retro Revolution. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Brown, Stephen. 2018. “Retro Galore! Is There no end to Nostalgia?” Journal of Customer Behaviour 17 (1-2): 9–29.

- Brown, Stephen, Elizabeth Hirschman, and Pauline Maclaran. 2001. “Always Historicize! Researching Marketing History in a Post-Historical Epoch.” Marketing Theory 1 (1): 49–89.

- Brown, Stephen, Robert V. Kozinets, and John F. Sherry, Jr. 2003. “Teaching old Brands new Tricks: Retro Branding and the Revival of Brand Meaning.” Journal of Marketing 67 (3): 19–33.

- Brown, Stephen, Pierre McDonagh, and Clifford J. Shultz. 2013. “Titanic: Consuming the Myths and Meanings of an Ambiguous Brand.” Journal of Consumer Research 40 (4): 595–614.

- Brown, Stephen, and Anthony Patterson. 2000. “Trade Softly Because you Trade on my Dreams: A Paradisal Prolegomenon.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18 (6/7): 316–320.

- Brown, Stephen, Anthony Patterson, and Rachel Ashman. 2020. “Raising the Dead: On Brands That go Bump in the Night.” Journal of Marketing Management 37 (5-6): 417–436.

- Brown, Stephen, Lorna Stevens, and Pauline Maclaran. 2021. “What’s the Story, Allegory?” Consumption Markets & Culture 25 (1): 34–51.

- Brunk, Katja H., Markus Giesler, and Benjamin J. Hartmann. 2018. “Creating a Consumable Past: How Memory Making Shapes Marketization.” Journal of Consumer Research 44 (6): 1325–1342.

- Burawoy, Michael. 1998. “The Extended Case Method.” Sociological Theory 16 (1): 4–33.

- Canniford, Robin, Kathleen Riach, and Tim Hill. 2018. “Nosenography: How Smell Constitutes Meaning, Identity and Temporal Experience in Spatial Assemblages.” Marketing Theory 18 (2): 234–248.

- Canniford, Robin, and Avi Shankar. 2013. “Purifying Practices: How Consumers Assemble Romantic Experiences of Nature.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (5): 1051–1069.

- Cervellon, Marie-Cécile, and Stephen Brown. 2018. “Reconsumption Reconsidered: Redressing Nostalgia with neo-Burlesque.” Marketing Theory 18 (3): 391–410.

- Chatzidakis, Andreas. 2015. “Guilt and Ethical Choice in Consumption: A Psychoanalytic Perspective.” Marketing Theory 15 (1): 79–93.

- Costa, Janeen Arnold. 1998. “Paradisal Discourse: A Critical Analysis of Marketing and Consuming Hawaii.” Consumption, Markets & Culture 1 (4): 303–346.

- Coverley, Merlin. 2020. Hauntology: Ghosts of Futures Past. Harpenden: Oldcastle Books.

- Dagalp, Ileyha, Katja Brunk, and Benjamin Hartmann. 2020. “The Aestheticization of Past-Themed Consumption.” Advances in Consumer Research 48: 47–51.

- Davis, Fred. 1979. Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York: Free Press.

- de Bernardi, Cecilia. 2019. “Authenticity as a Compromise: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Sámi Tourism Websites.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 14 (3): 249–262.

- DeBerry-Spence, Benét, and Elif Izberk-Bilgin. 2019. “Historicizing and Authenticating African Dress: Diaspora Double Consciousness and Narratives of Heritage and Community.” Consumption Markets & Culture 24 (2): 147–168.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Margins of Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1986. “Fors: The Anglish Words of Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok.” In The Wolf Man’s Magic Word: A Cryptonymy, edited by Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok, xi–xlviii. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1989. Of Spirit: Heidegger and the Question. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1993. Aporias. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1995. Points … Interviews, 1974-1994. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 2001. On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness. London and New York: Routledge.

- Derrida, Jacques. 2012/1993. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. New York: Routledge.

- Deuze, Mark. 2016. “Living in Media and the Future of Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 45 (3): 326–333.

- Edwards, Sarah, and Juliette Wilson. 2014. “Do We do the Past Differently now?” An Interview with David Lowenthal. Consumption Markets & Culture 17 (2): 105–119.

- Fisher, Mark. 2014. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. London: John Hunt Publishing.

- Fitchett, James, Georgios Patsiaouras, and Andrea Davies. 2014. “Myth and Ideology in Consumer Culture Theory.” Marketing Theory 14 (4): 495–506.

- Gordon, Avery. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Goulding, Christina. 2000. “The Commodification of the Past, Postmodern Pastiche, and the Search for Authentic Experiences at Contemporary Heritage Attractions.” European Journal of Marketing 34 (7): 835–853.

- Goulding, Christina. 2001. “Romancing the Past: Heritage Visiting and the Nostalgic Consumer.” Psychology & Marketing 18 (6): 565–592.

- Hamilton, Kathy, Sarah Edwards, Faye Hammill, Beverly Wagner, and Juliette Wilson. 2014. “Nostalgia in the Twenty-First Century.” Consumption Markets & Culture 17 (2): 101–104.

- Hartmann, Benjamin, and Katja Brunk. 2019. “Nostalgia Marketing and (re-)Enchantment.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 36 (4): 669–686.

- Hartmann, Benjamin, and Jacob Östberg. 2013. “Authenticating by re-Enchantment: The Discursive Making of Craft Production.” Journal of Marketing Management 29 (7): 882–911.

- Havlena, William, and Susan Holak. 1991. “The Good old Days’: Observations on Nostalgia and its Role in Consumer Behaviour.” Advances in Consumer Research 18: 323–329.

- Higson, Andrew. 2014. “Nostalgia is not What it Used to be: Heritage Films, Nostalgia Websites and Contemporary Consumers.” Consumption Markets & Culture 17 (2): 120–142.

- Hirschman, Elizabeth. 2000. Heroes, Monsters and Messiahs: Movies and Television Shows as the Mythology of American Culture. Kansas City: McNeel.

- Holak, Susan, and William Havlena. 1992. “Nostalgia: An Exploratory Study of Themes and Emotions in the Nostalgic Experience.” ACR North American Advances 19: 380–387.

- Holbrook, Morris. 1993. “Nostalgia and Consumption Preferences: Some Emerging Patterns of Consumer Tastes.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (2): 245–256.

- Holbrook, Morris, and Elizabeth Hirschman. 1982. “The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and fun.” Journal of Consumer Research 9 (2): 132–140.

- Holbrook, Morris, and Robert Schindler. 1991. “Echoes of the Dear Departed Past: Some Work in Progress on Nostalgia.” Advances in Consumer Research 18: 330–333.

- Holt, Douglas. 2004. How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding, Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press.

- Holt, Douglas, and Craig Thompson. 2004. “Man-of-action Heroes: The Pursuit of Heroic Masculinity in Everyday Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (2): 425–440.

- Huhmann, Bruce, and Timothy Brotherton. 1997. “A Content Analysis of Guilt Appeals in Popular Magazine Advertisements.” Journal of Advertising 26 (2): 35–45.

- Husemann, Katharina, and Giana Eckhardt. 2019. “Consumer Spirituality.” Journal of Marketing Management 35 (5-6): 391–406.

- Jameson, Frederic. 1999. “Marx’s Purloined Letter.” In Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium on Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx, edited by Michael Sprinker, 26–67. London: Verso.

- Kessous, Aurélie. 2015. “Nostalgia and Brands: A Sweet Rather Than a Bitter Cultural Evocation of the Past.” Journal of Marketing Management 31 (17-18): 1899–1923.

- Kirkpatrick, David. 2019. “Massacre Suspect Traveled the World but Lived on the Internet.” in The New York Times. 15 March. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/15/world/asia/new-zealand-shooting-brenton-tarrant.html.

- Kozinets, Robert. 2002. “Can Consumers Escape the Market? Emancipatory Illuminations from Burning man.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (1): 20–38.

- Labba, Elin Anna. 2020. Herrarna satte oss hit. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Luedicke, Marius, Craig Thompson, and Markus Giesler. 2010. “Consumer Identity Work as Moral Protagonism: How Myth and Ideology Animate a Brand-Mediated Moral Conflict.” Journal of Consumer Research 36 (6): 1016–1032.

- MacCannell, Dean. 1973. “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings.” American Journal of Sociology 79 (3): 589–603.

- Mackintosh, Kit. 2021. Neon Screams: How Drill, Trap and Bashment Made Music New Again. London: Repeater.

- McCracken, Grant. 1988. The Long Interview. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- McMullen, Ken [Director]. 1983. Ghost Dance. Paris: Independent.

- Mead, Margaret, and James Baldwin. 1971. A Rap on Race. London: Michael Joseph.

- O’Neill, Carly, Dick Houtman, and Stef Aupers. 2014. “Advertising Real Beer: Authenticity Claims Beyond Truth and Falsity.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (5): 585–601.

- Ozanne, Julie, and Samuelson Appau. 2019. “Spirits in the Marketplace.” Journal of Marketing Management 35 (5-6): 451–466.

- Reynolds, Simon. 2011. Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past. London: Faber & Faber.

- Richards, Julian. 2005. The Vikings: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rinallo, Diego, Linda Scott, and Pauline Maclaran. 2012. Consumption and Spirituality. New York: Routledge.

- Robinson, Thomas Derek, Ela Veresiu, and Ana Babić Rosario. 2021. “Consumer Timework.” Journal of Consumer Research (online 10 August, 2021).

- Salmon, Peter. 2021. An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida. London: Verso.

- Sherry, John. 2005. “Brand Meaning.” In Kellogg on Branding, edited by Alice Tybout, and Tim Calkins, 40–69. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Simpson, Dave. 2020. “An Evening with Whitney review – Houston Hologram is Ghoulish Cash-In,” in The Guardian. 28 Feb. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/feb/28/an-evening-with-whitney-houston-hologram-review-liverpool.

- Sobande, Francesca. 2019. “Woke-Washing: “Intersectional” Femvertising and Branding “Woke” Bravery.” European Journal of Marketing 54 (11): 2723–2745.

- Södergren, Jonatan. 2019. “From Aura to Jargon: The Social Life of Authentication.” Arts and the Market 9 (2): 115–131.

- Södergren, Jonatan. 2021. “Brand Authenticity: 25 Years of Research.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (4): 645–663.

- Spiggle, Susan. 1994. “Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data in Consumer Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (December): 491–503.

- Sprinker, Michael. 1999. Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium on Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx. London: Verso.

- Stern, Barbara. 1988. “Medieval Allegory: Roots of Advertising Strategy for the Mass Market.” Journal of Marketing 52 (3): 84–94.

- Stern, Barbara. 1992. “Historical and Personal Nostalgia in Advertising Text: The fin de Siecle Effect.” Journal of Advertising 21 (4): 11–22.

- Stern, Barbara. 1995. “Consumer Myths: Frye’s Taxonomy and the Structural Analysis of Consumption Text.” Journal of Consumer Research 22 (2): 165–185.

- Sullivan, Helen. 2021. “US Capitol Stormed: What We know So Far,” in The Guardian, 7 January. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/07/us-capitol-stormed-what-we-know-so-far.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei [Director]. 1983. Nostalghia. Rome: Gaumont.

- Thompson, Craig. 2004a. “Dreams of Eden: A Critical Reader-Response Analysis of the Mytho-Ideologies Encoded in Natural Health Advertisements.” In Elusive Consumption, edited by Karin Ekström, and Helene Brembeck, 175–204. Oxford: Berg.

- Thompson, Craig. 2004b. “Marketplace Mythology and Discourses of Power.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (1): 162–180.

- Thompson, Craig, and Gokcen Coskuner-Balli. 2007. “Countervailing Market Responses to Corporate co-Optation and the Ideological Recruitment of Consumption Communities.” Journal of Consumer Research 34 (2): 135–152.

- Thompson, Craig, William Locander, and Howard Pollio. 1989. “Putting Consumer Experience Back Into Consumer Research: The Philosophy and Method of Existential-Phenomenology.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (2): 133–146.

- Thompson, Craig, and Kelly Tian. 2008. “Reconstructing the South: How Commercial Myths Compete for Identity Value Through the Ideological Shaping of Popular Memories and Countermemories.” Journal of Consumer Research 34 (5): 595–613.

- Tomasi di Lampedusa, Giuseppe. 2007 [1958]. The Leopard. London: Vintage Books.

- Toussaint-Strauss, Josh. 2020. “Black Enough? How ‘Voodoo’ became a Metaphor of Evil.” in The Guardian. 26 Nov. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/video/2020/nov/26/how-voodoo-became-a-metaphor-for-evil.