ABSTRACT

This study analyses the visual construction of girls and notions surrounding young femininities articulated by 15 contemporary advertisements of Nordic fast fashion companies, available on their public Facebook pages in Finland. A visual discourse analysis identifies some blatantly stereotypical and a few complex visual constructions of girls as heterosexual, caring, innocent, sexy posers, active self-presenters and self-surveyors, carefree and environmental activists. The implications of our findings, particularly in shaping societal notions surrounding girls, are discussed. The study contributes primarily to the research field of visual commercial representation of girls by unpacking how their complex portrayals can create an equivocation that eventually resurrects stereotypes surrounding young femininities. It advances studies on Nordic consumer culture by highlighting that girls’ portrayals by Nordic companies may not clearly reflect the values of state feminism. The study can benefit marketers by sensitising them to how the complex visual representations of girls may (re)produce stereotypes.

Introduction

In girlhood studies, discourses on young femininities are considered pivotal in shaping notions of girls (Driscoll Citation2002; Aapola, Gonick, and Harris Citation2005). Visual images also (re)produce societal discourses and impart certain ideas on the subject depicted (Rose Citation2016). Therefore, examining the discourses constructed by images featuring girls is essential because those images propagate notions on girls hence young femininities to their audiences and shape their ideas on girls. Advertised images have been described by Jonathan Schroeder (Citation2002) as a form of “visual consumption”. This emphasises the powerful role that advertisements play in shaping societal ideas (Schroeder Citation2002) and even societal views on gender (Schroeder and Zwick Citation2004). Visual representation of girls in advertisements is an established research field (see Holland Citation2004; Merskin Citation2004; Cann Citation2012; Lindén Citation2013; Graff, Murnen, and Krause Citation2013; Speno and Aubrey Citation2018). This study belongs to that research field. It analyses the visual construction of girls in contemporary fast fashion advertisements and the notions on young femininities they articulate.

Fast fashion refers to garments produced in a brief turnaround time and at low costs, usually in the Global South (Thomas Citation2019). Teenagers find fast fashion particularly appealing as it offers a variety of clothing at affordable prices (Nguyen Citation2021). Horton (Citation2018, 519) points out that women and girls are especially attracted to the variety offered by fast fashion. Given the influential position of fast fashion in specifically teenage girls’ clothing market, it is vital to study the visual construction of girls in fast fashion advertisements. The visual construction reflects notions about girls and young femininities that fast fashion companies propagate in society through their advertisements. The relative powerlessness of the important customer group of young girls further strengthens the social relevance of scrutinising these reflections.

To our knowledge, the visual construction of girls in fast fashion advertisements has not been examined before. In the current study, we address this topic by posing the following research questions: (i) How are girls visually constructed in fast fashion contemporary advertisements? and (ii) What kind of notions related to young femininities do these advertisements convey?

We have employed visual discourse analysis (Rose Citation2016) to analyse 15 advertised images. Our focus is on notions surrounding young femininities. Hence, we have examined advertisements that feature young girls and are targeted at buyers of teenage girls’ clothing. Advertisements addressing the Finnish market found on the public Facebook pages of the Nordic fast fashion companies Hennes & Mauritz (H&M), Lindex, KappAhl and GinaTricot from January 2019 to June 2020 have been analysed.

The Nordic context shapes our expectations that these advertisements may convey non-stereotypical notions on young femininities. Molander, Östberg, and Kleppe (Citation2019, 140) note that marketers in Nordic consumer culture often align their advertising messages with the welfare state’s orientation. For instance, Baby Bjorn’s advertisements use the Swedish welfare state’s values of gender-equal parenting to promote progressive ideas on fatherhood. Nordic welfare states are understood to follow “state feminism” due to their initiatives to encourage women’s labour participation and promote gender equality (Formark, Mulari, and Voipio Citation2017, 10). Korsvold (Citation2012, 14) shows that advertisements of Helly Hansen targeted at the Nordic market in the 1950s and 1980s reproduced historical, cultural and regional notions of an ideal Nordic childhood. She highlights that the societal contexts of markets shape advertised portrayals. The idea of agentic Nordic girlhoods (Österlund Citation2012) could get mirrored in these companies’ advertisements, and more so, because they address audiences in a country like Finland that ranks relatively high on gender equality (World Economic Forum Citation2020). This Nordic context thus forms a backdrop to this study.

The internal policy commitments of the companies mentioned above also shape our expectations of their possibly challenging stereotypes related to young femininities, which is the chief reason behind our analysis of their advertisements. “Institutionalised” corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives include internal policy commitments that promote social goals and help companies meet their social and ethical responsibilities (Pirsch, Gupta, and Grau Citation2007). These fast fashion companies have announced such initiatives as well, as they aim to promote gender equality in the workforce and supply chain (GinaTricot Citation2016, 2019; H&M Group Citation2017, Citation2019; KappAhl Citation2018, Citation2019; Lindex Citation2019, Citation2020). The companies that promote gender equality in their workforce could also be expected to reflect such commitments in their advertisements by portraying girls in non-gender stereotypical ways. This expectation stems from academic literature that urges for-profit companies to advance their ethical agenda by challenging stereotypes in their advertisements (Borgerson and Schroeder Citation2002; Stevens and Ostberg Citation2012).

Through this study, we intend to contribute to the research field of visual representation of girls in advertisements. Prior research suggests that young girls are represented in gender-stereotypical ways (Holland Citation2004) and their imagery is often sexualised (Merskin Citation2004; Graff, Murnen, and Krause Citation2013; Speno and Aubrey Citation2018). Previous studies have also identified multiple portrayals of girls in advertisements (Lindén Citation2013) as well as complex images encompassing contradictory ideas (Cann Citation2012). However, how complex images of girls end up resurrecting stereotypical notions related to young femininities remains understudied. We address this gap and contribute to the existing literature by identifying various ways by which girls’ portrayals are made complex to convey an equivocation that does not fully undo stereotypes related to young femininities. The unpacking of complex visual commercial constructions of girls is essential to understand how they may hinder the propagation of non-stereotypical notions on young femininities. We identify starkly stereotypical portrayals as well. By examining how the Nordic context shapes the visual representation of girls in these advertisements, the study also contributes to research on Nordic consumer culture.

The article is structured as follows: first, we discuss the previous literature on the visual representation of girls in advertisements. Next, we describe our materials and method and present the results. Finally, we discuss the contributions, implications and limitations of the study and conclude by making suggestions for future research.

Previous research on visual representation of girls in advertisements

Before we discuss previous studies on the visual representation of girls in advertisements of various products and by clothing companies per se, it is pertinent to point out that teenagers also fall in the category of children (United Nations General Assembly Citation1989). Therefore, we draw from studies that focus on children’s representation in clothing advertisements, even though they concentrate, for the most part, on younger children. In the upcoming sections, we first discuss how commercial portrayals of young girls have reflected assumptions about girls that are informed by traditional discourses on young femininities. Then, postfeminist discourses that project girls as actors are discussed along with the criticism of these discourses. These two discourses were discernible in our dataset, either singly in certain images or in a complex mix in others.

Traditional ideas on girls as heterosexual, caring, innocent and interested in appearance

The idea of heterosexuality is a constricting view on gender and sexuality often reproduced by advertisements. Judith Butler (Citation1990) argues that the consistent visualisation of only two genders has led to the consolidation of what she terms the “heterosexual matrix”—the idea of heterosexuality as natural. Daniel Thomas Cook (Citation1999, 27), in his study on children’s representation in clothing advertisements, shows that even young children are portrayed as heterosexual, reflecting adults’ assumptions on gender relations. A study on girls in Finland, Canada and Australia reports that heterosexuality was the hegemonic discourse within which young girls practised their evolving sexuality (Harris, Aapola, and Gonick Citation2000). Research on advertisements and magazine content targeted at teenage girls has revealed that they promote heteronormative values and assume girls’ heterosexuality (Durham Citation2007; Lindén Citation2013).

The traditional association of girls with roles of care and domesticity has been reproduced in their visual representation (Holland Citation2004, 187). The gendered division of labour that arose in the industrial age has been seen as the genesis of the idea of women and girls as caring and suitable for the domestic sphere (Carter and Steiner Citation2004, 12). The portrayal of girls in outdoor, non-domestic spaces like forests and the countryside has been understood as a bid to connect nature with femininity and naturalise the latter (Cann Citation2012; Lindén Citation2013).

The conservative notion of girls’ innocence and naivety has been reinforced in their portrayals (Cann Citation2012, 77). Egan and Hawkes (Citation2008) describe the insistence on girlhood innocence as a bid to control girls’ sexuality, which amounts to positioning them as largely innocent and thereby asexual. However, some studies observe that visual elements articulating contradictory ideas of sexuality and innocence are often deployed in the same image to create ambiguity (Holland Citation2004, 192; Vänskä Citation2017). Vänskä (Citation2017, 87), in her study on young children’s representation in high fashion advertising, terms this as “eroticised innocence”.

The idea of appearance and preening as the domain of girls has been conveyed in advertisements (Holland Citation2004, 187). The association of the female body with appearance has been criticised by feminist scholars since the 1960s and 1970s (Gill Citation2007a). Bartky (Citation1990, 79–80) asserts that patriarchy and consumer capitalism exert an invisible gaze, akin to Michel Foucault’s idea of the panopticon gaze, to produce a female subject who practises self-surveillance and is fully aware that she is an object of display. Aapola, Gonick, and Harris (Citation2005, 136) contend that young girls work on their appearance because they are encouraged to view their bodies as objects that exist primarily for the pleasure of others. Research with young girls has shown that girls often discuss personal appearance in their peer groups, and practise self-surveillance to ensure that their bodies appear beautiful (Carey, Donaghue, and Broderick Citation2011).

Cook (Citation1999) argues that commercial visual representations of children express the various assumptions of marketers about childhoods. Similarly, the gender-stereotypical representations of girls discussed above seem to communicate certain ideas and assumptions about girls. Feminist scholars have criticised the gender-stereotypical depiction of young girls and women (Gill Citation2007a; Carter and Steiner Citation2004).

Girl power and postfeminism

Angela McRobbie (Citation1997) observes that although representations associating girls with domesticity and passivity did not completely disappear, some changes were discernible in media portrayals of girls and women from the late 1980s and early 1990s. They were represented more as active subjects instead of passive and docile (McRobbie Citation1997). Girl power discourses became very popular in many Western countries from the early 1990s and were characterised by the representation and positioning of girls as active, agentic subjects who could do and achieve anything (Harris Citation2004; Aapola, Gonick, and Harris Citation2005; Griffin Citation2004). British girl band the Spice Girls rendered girl power into a more commercial and marketable idea (Genz and Brabon Citation2009; Aapola, Gonick, and Harris Citation2005).

Girl power is a strand of postfeminism (Genz and Brabon Citation2009, 5). In relation to media representations, Rosalind Gill (Citation2007b, 149) has defined postfeminism as a contradictory sensibility, encompassing feminist and antifeminist ideas simultaneously. She asserts that various elements mark this sensibility, one of them being the idea of girls and women as subjects—as opposed to objects—choosing to display their bodies (Gill Citation2007b, 149). Sexualisation of teen girls’ images has been observed in fashion advertising (Merskin Citation2004) and advertisements of various products in teen magazines in the USA (Graff, Murnen, and Krause Citation2013; Speno and Aubrey Citation2018). However, these studies do not differentiate between sexual subjectivity and objectivity using the postfeminist discourse. Neoliberal ideas and values promote the view of individuals as autonomous agents who shape their lives through personal choices (Gill Citation2007b). Elements of individual choice chime well with neoliberal values that started gaining popularity during the time that postfeminist sensibility began to appear in media materials (Gill Citation2007b, 153; Gill and Scharff Citation2011, 7). The unabated popularity of neoliberal values has meant that this sensibility remains relevant even today (Gill Citation2017).

Postfeminist media texts have been criticised by feminist media critics for various reasons. One criticism is that they create a rhetoric of empowerment by using neoliberal values of individual choice and agency, but only reinstate some gender-stereotypical ideas and leave patriarchal values unthreatened (Gill Citation2007a, Citation2008; McRobbie Citation2008, Citation2009). Moreover, freedom to consume is narrowly equated with empowerment (McRobbie Citation2009). To sum up, feminist media critics assert that the propagation of agentic femininity by postfeminist discourses wraps within itself certain stereotypes about women.

Multiple and complex visual construction of girls

Lindén’s (Citation2013) visual discourse analysis of direct-to-consumer advertisements of the Gardasil HPV vaccine in Sweden reports multiple visual representations of girls. She identifies portrayals of girls that either deploy girl power discourses representing them as “independent” and “sporty” or traditional discourses depicting them as “dependent, at-risk and heterosexual” (Lindén Citation2013, 94). In her semiotic analysis of advertisements in British teen magazines, Cann (Citation2012) observes complexity through the use of signifiers that simultaneously indicate what she terms “traditional and contemporary femininities in the same text” (78). Cann’s (Citation2012) analysis almost suggests that the latter is superior to the former by under-problematising contemporary femininities.

However, how complex images of girls stop short of challenging stereotypes related to young femininities is understudied. This study intends to contribute to the existing literature by identifying how complexity gets created in girls’ portrayals to exude an ambivalence that does not adequately challenge stereotypes related to young femininities.

Materials

We study the visual construction of girls in contemporary fast fashion advertisements targeted at buyers of teenage girls’ clothing. Given the “institutionalised CSR commitments” (Pirsch, Gupta, and Grau Citation2007, 137) of Nordic fast fashion companies H&M, Lindex, KappAhl and GinaTricot to promote gender equality, their advertisements were chosen for our analysis. According to H&M’s sustainability report (H&M Group Citation2017), they aim at creating a workplace free from sex-based discrimination. They outline these goals for workers in the company’s supply chain as well (H&M Group Citation2019). Lindex aims to increase the number of women in leadership positions and ensure the implementation of gender-equal policies in its suppliers’ factories (Lindex Citation2019, 2020). Promoting gender equality in employment and at the workplace is mentioned in KappAhl’s sustainability strategy in successive annual reports (KappAhl Citation2018, Citation2019). GinaTricot has recognised gender equality as a goal and management approach (GinaTricot Citation2016) and pledged to support the empowerment of women workers in its supply chain (GinaTricot Citation2019, 20). These commitments lead us to expect these companies to portray girls with caution in a non-gender stereotypical fashion. Therefore, their advertisements were chosen for scrutiny in this study.

Since social media platforms have a higher ability to target customers by employing sophisticated algorithms (Montgomery, Chester, and Milosevic Citation2017, 118), a social media platform was selected as the source of data collection. Apart from traditional advertisements, even influencer advertising is prevalent on social media platforms. Nevertheless, brand control on messaging is somewhat diluted in influencer advertising (Martínez-López et al. Citation2020, 1819). Since our choice of analysing the advertisements of specific companies was rooted in an expectation that their policy orientation might be reflected in their advertising, we chose to analyse only traditional advertisements where company control over messaging is higher.

The data for this study was collected by visiting the public Facebook pages of the above-mentioned Nordic fast fashion companies catering to Finland. The advertised images were collected from the public Facebook pages of H&M (https://fi-fi.facebook.com/hmsuomi/), Lindex (https://fi-fi.facebook.com/Lindex), KappAhl (https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/) and GinaTricot (https://fi-fi.facebook.com/GinaTricot/). These images were collected by visiting the “photos” section (kuvat in Finnish). The data was collected in July 2020. Given our focus on contemporary fast fashion advertisements, we selected advertised images appearing from January 2019 to June 2020 for our analysis. All analysed images have been reprinted after obtaining permission from the companies.

Apart from Facebook, social media platforms like Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok may host traditional advertisements as well. Since we aim to examine the notions surrounding young femininities articulated by contemporary fast fashion advertisements, we attempted to scrutinise advertisements viewed by a wider audience that are potentially instrumental in informing their ideas related to young femininities. Therefore, we sought to collect data from a social media platform that was employed to advertise to users of various age groups like girls, guardians and parents. Furthermore, parents as “second-order consumers” (Knudsen and Kuever Citation2015, 172) are significant customers of teenage girls’ clothing apart from girls themselves, so they may well be targeted with advertisements for teen girls’ clothes. Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok are used mainly by young people, but Facebook is used for advertising to all age groups of consumers (omnicoreagency.com Citation2021). Facebook was chosen as the source of data collection since its advertisements reach a wider audience.

Since these fast fashion companies produce offerings for different age groups, there were various advertised images targeted at buyers of girls’ clothing in the photos section. As our focus was on advertised images targeted at buyers of teenage girls’ clothing, our attempt was to select images featuring young girls as opposed to female children or women. It was not very challenging to distinguish young girls from women. However, that was not the case when we tried to distinguish between female children and young girls because the differences between their visual presentations were often somewhat blurry, posing some challenges in selecting the images to be analysed.

To address this challenge, we looked for visual markers employed in the images to communicate the visual presentation of young girls as opposed to female children. This included paying attention to the appearance of elements that are associated with young girls. Physical markers included the appearance of breasts, rounder hips, fuller thighs, fuller arms, longer legs and the style of posing adopted by the girl models in the images. Hair that was rough-looking and wavy, as opposed to the smooth locks of female children, was observed. Skin that appears rough, the explicit use of makeup to appear older and thicker eyebrows indicated the visual presentation of young girls and not female children. Some other visual indicators included the presence of accessories popular among young girls, such as choker necklaces, ankle-length boots and hooded sweatshirts. One or more of these visual markers appear in each of the images that form the data for analysis. Since images are polysemic (Gill Citation2007a), we acknowledge a level of researcher subjectivity in the selection of data for analysis.

The data consists of 15 advertised images. In some images in our dataset, girls appear with young boys and younger children. The small number of images catering to buyers of teenage girls’ clothing during the given period could be because, as mentioned above, these companies do not produce offerings only for the teenage girls’ clothing market. Moreover, it is important to reflect upon how our subjectivity may have impacted the number of images we chose to include in the dataset. Given the challenges and dilemmas we faced in determining if the girls represented young girls or female children, we may have excluded some advertised images because we interpreted the visual presentation of girl models in the images as more akin to that of female children. Therefore, we cannot claim this sample to be fully representative. Nevertheless, it is reflective because the mere presence of these images on companies’ Facebook pages indicates that these advertisements have been instrumental in communicating notions about young femininities that these companies have chosen to propagate.

Method

Gillian Rose (Citation2016, 187–188) developed the method of visual discourse analysis to analyse how images construct discourses and the manner in which visual presentations in them are articulated to appear truthful and (re)produce certain notions on the subject presented. According to Rose, images are not neutral but rather instrumental in presenting a selective version of the social world (Rose Citation2016, 2). Foucault’s ideas on discourse are central to the theory and method of visual discourse analysis. Rose explains Foucault’s ideas on discourse as a set of statements that shape knowledge and thereby influence people’s actions (Rose Citation2016, 188).

The importance of discourses related to girlhoods and young femininities in different historical, cultural and social contexts is emphasised in shaping societal ideas on girls in the field of girlhood studies (Driscoll Citation2002; Aapola, Gonick, and Harris Citation2005). In this study, this theoretical approach towards girls and young femininities has been combined with the theory and method of visual discourse analysis to analyse how girls are visually constructed in the advertised images and what notions on young femininities they (re)produce.

Rose (Citation2016) highlights that, as a method, visual discourse analysis involves studying images carefully and categorising them by identifying important key themes in and across images. It also requires paying attention to details, contradictions, complexities, visible and invisible in images to identify discourses articulated through them so as to construct a particular visual presentation as truthful (Rose Citation2016, 205–206). Intervisuality can be used to identify discourses as well (Sparrman Citation2018). Nicholas Mirzoeff (Citation2000, 7) explains that the concept of intervisuality involves thinking of what an image may be reminiscent of to the onlooker. We have used this concept of intervisuality by looking at what some images in our sample reminded us of and then paying attention to the discourses on young femininities that this similarity may indicate.

In line with Rose’s (Citation2016) method, we studied the images individually and then together. All the visual occurrences and textual references were noted, and these comprised our initial set of themes in every image. Some of these themes seemed related and were grouped under one key theme. Multiple themes and key themes that could be related to various discourses were discernible in these images. However, we concentrated on themes that were relevant to discourses on young femininities. Images with similar key themes were categorised together, but single images with important themes were not ignored. We also identified key themes in a single image that could be related to two different discourses on young femininities.

Rose (Citation2016) recommends undertaking multiple readings of images because it often leads to the revision of initial categories. Likewise, after the initial categorisation, the images in each category were again studied carefully to look for details, contradictions, visible, invisible and even intervisuality to identify the discourses that were being articulated through the images. Based on this reading, the initial categorisation was revised. We found that some images with common key themes like girls in an outdoor environment or girls posing with a pout were not necessarily indicative of the same discourse on young femininities. This close reading was performed multiple times to carefully identify the discourses articulated by the images in order to construct a particular visual presentation of girls as truthful. The categorisations were revised multiple times based on new observations. After this process of close readings and revisions, we concluded that in the advertised images in our sample, girls were visually constructed as heterosexual, caring, innocent, sexy-posers, active self-presenters and self-surveyors, carefree and environmental activists. We now discuss how these are visually constructed in the advertisements.

Results

We first elaborate on the visual construction of girls as heterosexual, caring and innocent that are based on stereotypical assumptions about girls. Then we describe the visual construction of girls as sexy posers that deploy postfeminist discourses by showing them as acting in front of the camera as sexual subjects. Finally, we discuss the complex visual constructions of girls as active self-presenters and self-surveyors, carefree and environmental activists. They use ideas of an agentic girl subject but do not disassociate from traditional notions on girls. Our analysis therefore contributes to the research field of visual representation of girls in advertisements. It does so by unpacking various ways in which girls’ portrayals can be made complex to impart an ambiguity that does not fully unseat stereotypes related to young femininities.

Heterosexual

Butler (Citation1990) explains, through the concept of the heterosexual matrix, that the constitution of gender within the binary frame helps “naturalise” heterosexuality. This conventional discourse of heterosexuality is constructed through four images from KappAhl. In , a girl and a boy are pictured wearing formal clothing, smiling and looking directly at the camera. They are shown standing huddled close to one another with the boy’s arm placed around the girl, his hand resting on her elbow and the girl’s arm around him resting on his shoulder. Her head is bent slightly towards the boy, while the boy is standing straight with legs apart, perhaps to signify authority and thereby masculinity. Elements like formal dressing, their manner of standing huddled together and the girl’s head bent towards the boy all combine to make it appear as if they are being projected as a future adult couple.

Figure 1. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2351922791756808/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

Somewhat similarly in , a young girl and a boy are pictured in an outdoor location with autumn leaves strewn around them. They appear to be running happily, as both are shown smiling and looking directly at the camera. Buildings or passers-by are not visible in the background, which signifies privacy. Their picturisation at a lonely spot combined with the gleeful look on their faces, seemingly to indicate happiness at being able to steal a candid moment together, gives the image a romantic tone.

Figure 2. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2438498443099242/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

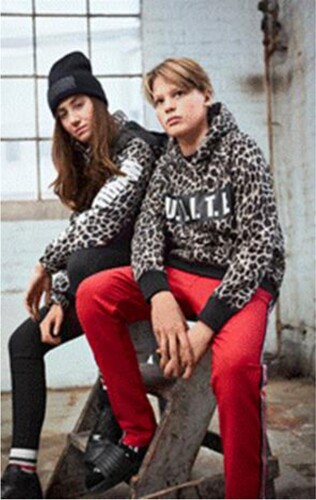

The picture in is in an indoor location and shows a boy and a girl seated together on the same stool. The girl looks directly at the camera with a serious and slightly defiant expression, while the boy looks away from the camera with a somewhat disinterested look. The boy is shown wearing a pair of deep red trousers as opposed to blue or grey colours “usually” associated with boys. Vänskä (Citation2017, 78) posits that even colours signify gender, and red is associated with strength and masculinity. Any visual indicators of androgyny such as makeup, long hair and blended clothing style (Vänskä Citation2017, 155) do not appear in this image. Moreover, visual markers of femininity and masculinity through long and short hair, respectively (Vänskä Citation2017, 139), are present in the image. These clear visual markers of gender identity of the boy and the girl seen alongside their placement on the same stool seem to indicate that they are both pictured as a couple, something that the defiant expression on the girl’s face helps reinforce.

Figure 3. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2282798822002539/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

It is relevant to point out that the boy and girl pairs pictured in these images are not engaged in any sexually explicit or romantic acts, and they could well be interpreted as siblings or just friends. However, the manner of picturing the boy and girl pairs as a future adult couple standing close to one another in formal clothes in , running in an outdoor location in and seated on the same stool in provides less support for alternative interpretations of these images. Notably, peers, generally considered important in young people’s lives, are invisible in these images indicating an intent to show the girl and boy pairs as a couple.

The fourth image () shows a group of children of varying ages sitting on a sofa that appears to be placed surprisingly in the middle of a forest. The oldest-looking girl and boy are sitting together. A toddler sits near the girl, and older children (older than the toddler) occupy the sofa with them. The visual arrangement bears an intervisuality with a heteronormative nuclear family posing for a family photograph. Heteronormativity even gets expressed in how the girl and the boy, visually presented as the two oldest, sit next to one another with the girl’s legs placed comfortably on the boy’s lap signifying familiarity and fun.

Figure 4. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2438497956432624/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

The images help sustain the traditional notion that girls are primarily heterosexual as they align with the heterosexual matrix.

Caring

Emerging from the industrial economy’s gendered division of labour, traditional discourses on women and girls construct them as predisposed to undertake caring responsibilities (Carter and Steiner Citation2004, 12). This traditional discourse on girls gets articulated in three advertised images from KappAhl. In all three images, older girls are pictured along with younger children.

shows a group of mixed-age children sitting near a Christmas tree, wearing clothes in Christmas colours like red, green and white. Four out of the five children are visible, while one is partly visible. Notably, while all the children, including the partly visible child, are shown holding a gift, the girl represented as the oldest has a small child on her lap and not a gift. She smiles and looks happily at the child, visually indicating contentment. Furthermore, the comfort with which she is shown holding the toddler suggests confidence. A similar idea of confidence and contentment in caring is exuded through . Here, a toddler is placed near the older girl and not near the older boy. Similar to , the girl is shown holding a toddler happily and confidently.

Figure 5. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2523190361296716/?type=3&theatre%5C. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

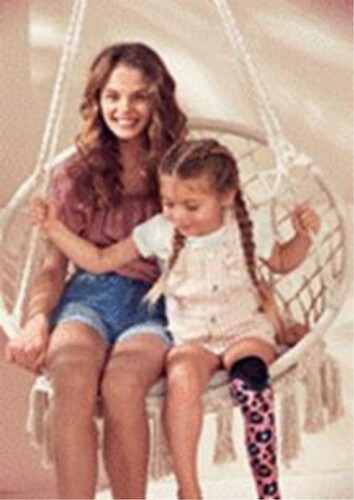

While not pictured directly caring for a child, a young girl appears with a female child in need of care in . This image shows two girls sitting on a swing and smiling. The older girl looks at the camera while the girl child gazes at the floor. Though the older girl is not directly caring for the girl child in this image, she is pictured alongside a child with a plastered leg hence someone potentially in need of care.

Figure 6. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2660784260870658/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

Holland (Citation2004, 187) points out that gender-stereotypical images of girls present them as training to take over the roles of their mothers and occupy a gendered world of adults. In these images, girls are not only associated with caring but are shown to be enjoying it, thereby creating an effect of truth that girls are “naturally” adept at caring. The invisibility of boys in these caring responsibilities or the placing of younger children only on girls despite the presence of boys in the image further cements this notion related to girls.

Innocent

Egan and Hawkes (Citation2008) point out that ideas of innocence and almost compulsory asexuality are pushed onto young girls, which becomes a means of monitoring their sexuality. This discourse of girlhood innocence gets articulated in two images.

shows two girls wearing night pyjamas. Partly covered in a white duvet, they are standing against a white background, making white predominant in the image, with only the clothes of one girl in deep red appearing as a contrast. The girl in white clothes looks away from the camera and has a dreamy look in her eyes. Her head is slightly tilted as she leans on the other girl indicating dependence. It is somewhat contradictory that the dreamy-eyed girl sports a T-shirt with the image of Snow White, a fairy tale character, more likely to be the choice of little girls instead of older ones. These overly childlike pyjamas could indicate a bid to emphasise the girl’s innocence that the dreamy look in her eyes and pose of dependence further reiterate.

Figure 7. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/hmsuomi/photos/a.1923897201169167/3180550135503861/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/hmsuomi/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © H&M. Reuse not permitted.

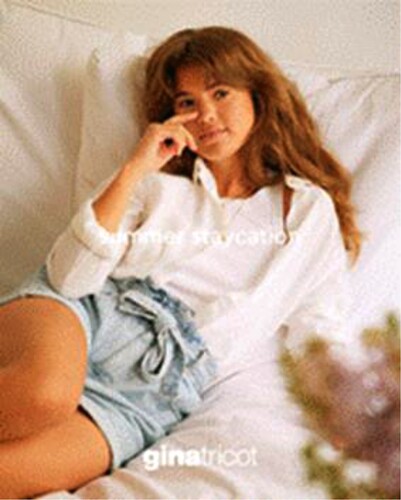

White is also predominant in that shows a blonde-haired girl sitting with white cushions in the background. She is pictured wearing an unbuttoned white shirt, a white vest or sleeveless T-shirt underneath and a pair of denim shorts that make her legs visible. She looks away from the camera with a soft smile and a slightly dreamy look in her eyes. Perhaps she is dreaming of a “summer staycation”, as the text on the image indicates. Just like the other image, the predominance of white in this image is stark. White is associated with purity, virginity and innocence (Vänskä Citation2017, 90).

Figure 8. Image URL: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/GinaTricot/photos/a.10150107818417896/10157505646827896/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/GinaTricot/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © GinaTricot. Reuse not permitted.

In visual representations, boundaries between innocence and sexuality are made rather blurry because advertisers often deploy elements signifying both within the same image (Holland Citation2004; Vänskä Citation2017). In , this blurriness between innocence and sexuality is discernible. While innocence gets expressed by the use of white and a dreamy look on the girl’s face, certain features also lend the image a sexualised character. Elements like the girl’s visible naked legs and her white unbuttoned shirt could be read as suggestive when combined with her soft smile and gaze away from the camera that seems to suggest that she is waiting for someone to join her in her cosy, cushioned space.

However, the theme of innocence is distinct in both images and gets expressed through the predominantly white background and the dreamy look on the girls’ faces. By picturing an older girl in a manner reminiscent of a young child, helps in reproducing the traditional discourse of girlhood innocence and sustains the notion that older girls are primarily asexual. produces the notion of girlhood innocence but intermixes it with sexuality by playing with both elements.

Sexy posers

An essential element that characterises postfeminist discourses is the construction of girls and women as sexual subjects (Gill Citation2007b). This postfeminist discourse gets produced in two images where visual strategies are deployed to show that girls are willingly posing in a sexy manner.

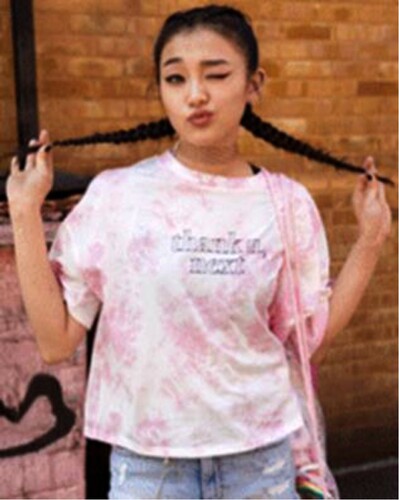

In , a girl of Southeast Asian origin stands holding her braids on both sides, simultaneously winking and pouting, and wearing heavy eye makeup. She is pictured looking directly at the camera and so at the onlooker of the image. The words “thank u, next” are inscribed on her T-shirt, making an intertextual reference to Ariana Grande’s popular song about her multiple ex-boyfriends (Grande Citation2018). The visual arrangement makes both the girl and the words inscribed on her T-shirt prominent. The latter viewed along with the pouting, winking and her heavy eye makeup—that accentuates the wink—give the image of the girl a sexualised character. It makes one wonder if the “next” in “thank u, next” indicates sexual frivolity. It could even be read as a mark of power, suggesting that the girl can choose and dismiss who she courts, thus signifying individual choice and agency.

Figure 9. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/hmsuomi/photos/a.1923897201169167/3057059121186297/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/hmsuomi/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © H&M. Reuse not permitted.

In , three girls of Southeast Asian origin are pictured looking directly at the camera. The girl in the middle sports a slight pout, while the girl on her left is pouting with her eyes partly closed and chin held slightly up in a manner that signifies sexual pleasure. The third girl has a serious and defiant look on her face. She is wearing a sweatshirt with the image of a woman whose cleavage is visible and eyes are closed in a manner that suggests sexual pleasure. The sexualised imagery of a woman on a young girl’s sweatshirt is confusing. It could be interpreted as the projection of the wearer’s aspirational self or could indicate that the image recognises lesbian girls. In Gill’s (Citation2008) analysis of the representation of “hot lesbians” in advertisements, she identifies the portrayal of two similar-looking girls posing together and embracing in a sexually explicit manner, looking feminine and suiting a heterosexual male’s fantasy. While the girls in are similar-looking, they are not engaged in sexually explicit acts amongst themselves and are simply pictured standing. Thus, it cannot be conclusively suggested whether the girls are being portrayed as lesbians or not. However, components like the first girl’s pout and partly closed eyes to indicate sexual pleasure, the second girl’s soft pout and the suggestive image on the third girl’s sweatshirt offer the image a sexualised character.

Figure 10. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/hmsuomi/photos/a.1923897201169167/3057059124519630/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/hmsuomi/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © H&M. Reuse not permitted.

Although both these images have a sexualised tone, they also communicate volition by using visual strategies like girls looking directly at the camera and so at the onlooker of the image. It leads one to argue that these images depict girls as actively engaged in posing in a sexy manner and not as passive objects. In so doing, they produce the postfeminist discourse of sexual subjectivity. The images exude the notion that girls willingly enjoy posing sexily.

Active self-presenters and self-surveyors

Aapola, Gonick, and Harris (Citation2005, 136) observe that, “Young women are encouraged to relate to their bodies as objects that exist for the use and aesthetic pleasure of others, and to work on the improvement of their appearance.” This discourse that associates girls with interest in appearance and self-presentation gets articulated in three images. However, it has been cloaked in the language of choice and agency characteristic of girl power discourses (Harris Citation2004).

shows a girl wearing a pair of skin-tight jeans or jeggings, an off-white woolly jumper and ankle-length boots. She is pictured standing, looking directly at the camera with a smile on her face. Her hands rest on her waist as she strikes a pose with the heel of one shoe resting on the floor and her toe in the air, suggesting that she is posing confidently to display the clothes that she is wearing. shows a girl looking directly at the camera and smiling. She is posing confidently in her outfit with her hands outstretched in a manner that indicates self-presentation.

Figure 11. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/Lindex/photos/a.10150778194024094/10156985254999094/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/Lindex. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © Lindex. Reuse not permitted.

Figure 12. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/Lindex/photos/a.10150778194024094/10156879744324094/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/Lindex. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © Lindex. Reuse not permitted.

In both images, girls are actively presenting themselves in their clothes. It can be argued that to pose for a clothing company’s advertisements, one has to present the body in those clothes. Noteworthily, in both images the girls are advertising a woolly jumper and brown furry jacket as well. However, the need for these clothes is not visually argued to be based on the attribute of comfort because the girls are not shown to be engaged in an activity wearing them. They actively pose in them instead.

Both images deploy gestures that indicate confidence. In , gestures like the girl facing the camera with a smile, hands on her waist, chin up, heels resting on the floor and the toes of a foot in the air reflect confidence. In , confidence is indicated through gestures like the girl facing the camera with a smile and her hands outstretched. Although laced with confidence, the deployment of these gestures in the images helps pass on the impression that the girls are seeking to be seen and approved in their clothes.

Exuding similar ideas of self-presentation, shows three girls sitting in an outdoor location under the open sky. They are pouting and posing in front of an invisible object held by one of the girls. It could be a mirror or perhaps a phone camera to take a group selfie. One of the girls is winking, another pouting. The third girl uses her hair to make a moustache held above her pouted mouth and is perhaps toying with a transgender identity. Through visual occurrences like the girls’ playful pouting and winking, the image attains an element of fun even as the girls engage in scrutinising themselves in the clothes and accessories that they sport. The text alongside the image “make the school hallway your own catwalk with the season’s latest collection” (translated from Finnish) further echoes the idea of self-presentation and thereby self-scrutiny.

Figure 13. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/hmsuomi/photos/a.1923897201169167/3080119108880298/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/hmsuomi/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © H&M. Reuse not permitted.

Girls are shown pouting and winking in and as well, as previously discussed under the visual construction of sexy posers. However, this image is interpreted differently because the pouting and winking that the girls perform here appear to be activities they playfully engage in amongst themselves. Unlike the images of girls discussed under the visual construction of sexy posers, these girls are not shown looking directly at the camera in a manner that indicates they are inviting the onlooker.

In , self-surveillance gets indicated because the girls gaze at themselves in a mirror or pose for a selfie, with the text urging them to “make the school hallway their own catwalk”. Interestingly, the advertisement addresses the girls directly and calls upon them to “make” the school hallway their catwalk. While this can be interpreted as addressing girls as empowered and choice-making subjects, the choice they are being asked to exercise is related to presenting their bodies in multiple clothes, just like a model does on a catwalk, to invite everyone’s gaze and envy. Therefore, the tone of empowerment is invoked only to encourage girls to present their bodies in different clothes. Furthermore, the text seems to send out the message to girls that even at school, they should be conscious of how they appear to others and therefore engage in self-surveillance.

Both the images in and portray girls as actively and confidently presenting themselves. Similarly, shows them as engaged in self-surveillance, with the text calling upon them to make active choices in buying new clothes to present their bodies. Therefore, these images together articulate the notion that girls are “naturally” inclined towards self-presentation and practise self-surveillance, but it has been well-packaged in ideas of choice and agency that characterise postfeminist girl power discourses using textual and visual strategies.

Carefree

Girls are traditionally associated with home and domesticity, and even though they are increasingly visible in social spaces, they are often affiliated with enclosures like shopping malls (Driscoll Citation2002, 259). Outdoor spaces can also be connected with nature (Cann Citation2012; Lindén Citation2013), thereby invoking the traditional idea of a natural association between femininity and nature (Ortner Citation1972). A complex portrayal of girls in an outdoor space that could be interpreted as either progressive or traditional is observed in one image.

shows two girls in an outdoor location. Perhaps it is a playground because a wire net and some parts of a playground are visible behind them. One girl holds and balances the other on her shoulders as both smile and have fun outside in the sun; these elements give them a carefree look. One can argue that showing girls having fun in an outdoor space like a playground produces a counter-discourse to the one that associates them with domestic spaces. However, the playground itself is open to two interpretations. If one associates the playground with sports, the image could be interpreted as breaking stereotypes related to girls. On the other hand, the playground could be viewed as an outdoor space close to nature, thus invoking femininities’ natural association with nature. This image constructs two discourses on young femininities depending on how the outdoor space in it is interpreted.

Figure 14. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/hmsuomi/photos/a.1923897201169167/3266748903550650/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/hmsuomi/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © H&M. Reuse not permitted.

This image shares certain features with that was discussed under the visual construction of active self-presenters and self-surveyors. In both images girls are shown having fun in an outdoor environment. However, we chose not to categorise that image under the visual construction of carefree girls because we noted several essential differences between the two images. Girls in this visual construction are having fun with each other, whereas the girls in are engaged in acts like looking at themselves in the mirror or taking selfies that seem to construct them as self-conscious. The textual emphasis in is on the self-presentation of girls.

Environmental activists

Girl power discourses are understood to propagate the idea of girls as agentic (Harris Citation2004; Aapola, Gonick, and Harris Citation2005; Griffin Citation2004). An assumed closeness between femininity and nature is a traditional idea related to femininity (Ortner Citation1972). Two discourses related to girls get constructed and sustained through the image from KappAhl in , thus creating a complex mix.

Figure 15. Image URL: https://www.facebook.com/KappAhlSuomi/photos/a.1538935169722245/2596914433924308/?type=3&theater. Source: https://fi-fi.facebook.com/KappAhl/. Date of access: 10 July 2020. © KappAhl. Reuse not permitted.

shows two girls, one of a shorter height and one slightly taller. They are pictured standing, with tall green grass and tropical trees appearing behind them. The taller girl has an arm placed around the shorter girl’s shoulder. Although visual markers of femininity like long hair (Vänskä Citation2017, 139) are sported by the taller girl, the dominating manner in which she stands, with legs apart in a masculine fashion and arm over the shorter girl’s shoulder, can be read in different ways. The pose could indicate masculinity and thereby an androgynous identity, especially if the tropical trees in the background were to be read as signifying the depiction of people from certain indigenous groups where boys keep long hair. However, the pose could well indicate an attempt to portray a powerful girl.

The text “fix the future” written on the shorter girl’s T-shirt, and the grass and trees in the background aid in establishing that the advertisement is referring to the Earth’s future. These elements show that the message of saving the environment is what the advertised image is attempting to communicate by using the imagery of these girls. The taller girl’s serious expression and slightly raised eyebrows viewed alongside the message “fix the future” offers her image an intervisuality with the famous Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg, who is known for demanding the same from significant world leaders (BBC Citation2020). However, the girl is not blonde and as white-skinned as Thunberg.

Therefore, the girls, especially the taller girl with the overpowering pose in which she stands with the shorter girl, are shown to occupy the role of activists. Girl power discourses are typically understood to portray girls as empowered, agentic and active (Harris Citation2004; Aapola, Gonick, and Harris Citation2005; Griffin Citation2004); this could be read as an articulation of girl power discourses. Noteworthily, environmental degradation—the issue to which these girls are employing their activism and the future for which they are urging action—impacts the entirety of humankind and not just girls. Nevertheless, boys and younger children are not present in this image even though they appear in other advertisements from KappAhl in our sample. The discourse of a natural closeness between femininity and nature (Ortner Citation1972) gets constructed through the invisibilisation of boys and younger children in the image.

While intervisuality with a teen activist associates the girl with agency and action, characteristic of girl power discourses, the image also naturalises femininity by showing the environment as the subject of activism. Therefore, the image articulates the notion that girls can deploy their activism but are likely to do so for causes like the environment because of their assumed closeness to the Earth.

Discussion

In this study, we employed visual discourse analysis to analyse the visual construction of girls and notions on young femininities articulated by 15 contemporary fast fashion advertisements. We found some outrightly stereotypical depictions and some complex ones that upheld stereotypes, albeit in relatively subtle ways.

Some images depicted girls in a traditional manner as heterosexual, caring and innocent. The portrayal of sexy posers reproduced postfeminist discourses. These results conform with previous studies on the visual representation of girls in advertisements which observe the portrayal of girls as caring (Holland Citation2004), innocent (Cann Citation2012), heterosexual (Lindén Citation2013) and sexy (Merskin Citation2004; Graff, Murnen, and Krause Citation2013; Speno and Aubrey Citation2018). Like Lindén (Citation2013), we found some images that either use traditional discourses or postfeminist discourses.

We also found some complex images which created an ambiguity that did not fully dislodge stereotypes related to young femininities. The visual construction of environmental activists associates girls with agency and action on the one hand but also reinstitutes the traditional association of femininity with nature on the other. This is somewhat similar to Cann’s (Citation2012) study, where contradictory ideas create complexity. However, Cann (Citation2012) identifies this through signifiers, and we show visual discursive constructions.

Unlike previous research, and as an original contribution, we have identified more visual and textual means by which girls’ portrayals can be made complex so as to convey an ambivalence that does not fully challenge feminine stereotypes. While progressive ideas of choice and agency were used, the stereotypical association of girls with appearance and self-presentation was simultaneously reinstated in the visual construction of girls as active self-presenters and self-surveyors. In the visual construction of carefree girls, the image is left ambiguous by showing girls with a playground behind them—an outdoor space that could either be associated with closeness to nature or sports. Therefore, we identified more ways by which complexity was created by either cloaking the image in the language of girls’ agency or by using a background that is open to two interpretations, with neither of the portrayals avidly challenging stereotypes related to young femininities.

We also aimed to consider how these advertisements were positioned in the Nordic context. Given Nordic states’ initiatives to promote gender equality through “state feminism” (Formark, Mulari, and Voipio Citation2017, 10), traditional visual constructions seem a little out of place. Postfeminist girl power discourses purportedly align with notions of an agentic Nordic girl subject (Lindén Citation2013), and their utilisation can be understood as a convenient choice while advertising in Nordic markets. However, since the postfeminist sensibility does not challenge the status quo (McRobbie Citation2009; Gill Citation2007b), the deployment of this discourse seems like rhetoric as opposed to genuinely progressive imagery. Molander, Östberg, and Kleppe (Citation2019, 140) have observed that Nordic companies often align with the welfare state’s orientation in their advertisements. Korsvold (Citation2012) shows that children’s portrayal in advertisements targeted at the Nordic market upheld regional ideals of Nordic childhoods. Traditional portrayals neither display an alignment with state feminism nor reflect regional ideals of agentic Nordic girlhoods. Visual constructions invoking postfeminist discourses and complex portrayals give the impression of being in tandem with the values of state feminism and the ideals of agentic Nordic girlhoods. Therefore, our results do not conform fully with Molander, Östberg and Kleppe’s (Citation2019) and Korsvold’s (Citation2012) observations related to Nordic consumer culture.

We chose to analyse the advertisements of Nordic fast fashion companies H&M, Lindex, KappAhl and GinaTricot as we were interested in exploring whether their institutional CSR commitments towards promoting gender equality percolate down to their commercial portrayal of girls. The expectation that such companies would likely challenge stereotypes on young femininities guided our choice. However, our findings left us asking for some vehemently non-stereotypical depiction of girls. At a contextual level, our results suggest that these companies do not extend their institutional agenda of promoting gender equality to the visual representation of girls in their advertisements.

Since advertisements play a central role in shaping societal ideas on gender (Schroeder and Zwick Citation2004), our results have broader implications as well. Gender-stereotypical representations could limit the expectations of societal groups portrayed stereotypically, thereby restricting their life opportunities (Knoll, Eisend, and Steinhagen Citation2011). The visual construction of girls as caring may promote the societal view of girls primarily as future carers. It might even encourage girls to unquestioningly accept a gendered division of labour. An alternative portrayal could have shown girls coding on a laptop, preparing to join the future workforce. In images showing mixed-age children, older boys instead could have been pictured holding younger children. The visual construction of girls as heterosexual tends to normalise girlhood heterosexuality. Propagation of girlhood innocence and asexuality reinforces the traditional good and bad girl binary, wherein the latter signifies sexuality (Vänskä Citation2017). Likewise, instead of portraying girls as innocent and reproducing such binaries, a progressive image could have shown girls and boys enjoying friendship together.

The visual construction of girls as sexy posers sustains postfeminist ideas of girls as empowered sexual subjects. However, Gill (Citation2008) criticises this postfeminist version of sexual agency as hollow because it upholds normative beauty standards, excludes girls who do not fit them and gives paramount importance to sexual attractiveness. Likewise, by depicting girls as sexy posers, these advertisements might encourage society to value girls merely for sexual attractiveness. Gill (Citation2008) warns that the postfeminist idea of sexual agency could be rather insidious for girls’ subjectivities because it prompts them to monitor their bodies to suit the male gaze but does so under the garb of empowerment and choice, making it harder to critique and easier to internalise.

Gender stereotyping in advertising has become more subtle (Gauntlett Citation2008, 85), and this also holds for the complex portrayals of girls that we observed in our analysis. Although the complex portrayals seem to deploy some progressive ideas, a close reading suggests that they simultaneously resurrect certain stereotypes related to young femininities. In doing so, the notions surrounding girls and young femininities they promote are somewhat restrictive. For instance, the visual construction of girls as active self-presenters and self-surveyors limits the use of girls’ agency to the domain of self-presentation. The stereotypical notion that associates femininity with appearance (Holland Citation2004) thus gets endorsed. An unequivocally non-stereotypical advertisement could have encouraged girls to make consumption choices of clothes for comfort rather than to showcase themselves.

Similarly, the visual construction of carefree girls seems only a half-hearted attempt to disassociate girls from feminine stereotypes. Instead of showing girls in an outdoor space that is open to interpretation, a more gender-equal portrayal could be girls engaging in sports in mixed-gender teams. Likewise, the visual construction of girls as environmental activists that portrays them as agentic is indeed positive. Nonetheless, these advertisements could have extended girls’ activism to other domains instead of sustaining the traditional idea of closeness between nature and femininity. Instead, boys and younger children could have appeared alongside girls as environmental activists.

We do not and cannot conclusively suggest that these images are intentionally made non-stereotypical. Nevertheless, we wish to highlight that marketers must engage critically with the advertisements they produce for their audiences, and more so if their companies commit to promoting values of gender equality. The analysis provided in this study can be used for such critical engagement, and the study also has practical usage. It can benefit marketers designing advertised images featuring young girls, as it sensitises them to how complex portrayals of girls can resurrect stereotypes related to young femininities. It even offers some suggestions to make portrayals of girls unambiguously non-stereotypical, which marketers might find helpful.

Like all studies, this study suffers from certain limitations. First, it is limited to a rather small sample of 15 advertised images. Furthermore, it only considers a very small sector of the market: the clothing and advertisements of four fast fashion companies. Future research could study advertisements from more market sectors and clothing companies. Since this study mainly contributes to the research field of visual representation of girls and young femininities in advertisements, our focus was chiefly on discourses related to gender. Future research could analyse the visual commercial construction of girls at the interstices of discourses on gender, body, beauty standards and race.

This study contributes to the research field of visual commercial representation of girls in new ways. It identifies various visual and textual means by which complexity gets created in girls’ images to express an equivocation that does not fully dislodge stereotypes related to young femininities. It advances studies on Nordic consumer culture. It does so by highlighting that Nordic companies’ advertisements targeted at buyers in a relatively gender-equal Nordic country neither clearly reflected the values of state feminism nor cogently mirrored ideas of agentic Nordic girlhoods in their portrayal of girls. Furthermore, this study raises a potent question in the Nordic context which is equally pertinent to the visual commercial construction of girls in general. It asks the following question: If Nordic companies can align with the welfare state’s orientation and promote progressive ideas on fatherhood globally through their advertisements (Molander, Östberg, and Kleppe Citation2019), why do they shy away from vehemently endorsing values of state feminism while portraying girls? It is beyond the scope of this study to pinpoint why these marketers do not challenge stereotypes avidly while portraying girls. Presumably, they use these advertisements because their research data indicates that such images will resonate with young girls and their parents and help sell fast fashion. Eventually, this kind of equivocal approach that this analysis has identified only fritters away opportunities to propagate progressive notions on young femininities through advertisements, not least because these companies are present in non-Nordic markets as well.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for all their valuable and helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sonali Srivastava

Sonali Srivastava (Master of Social Science in child studies, Linköping University) is a Doctoral Student of Sociology at the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research interests include visual culture, consumer culture, digital marketing and children's online privacy.

Terhi-Anna Wilska

Terhi-Anna Wilska is Professor of Sociology at the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research covers consumer behaviour, sociology of consumption and consumer culture. Recent topics of interest include sustainability in consumption and everyday life, ageing and life course, digitalisation and commerce.

Johanna Sjöberg

Johanna Sjöberg is an Associate Professor at the Department of Thematic Studies - Child Studies, Linköping University, Sweden. Her research focuses on children, consumption and visuality. She is currently working on two research projects: “Escaping shame or taking a vacation from the family? The market for private mother/baby homes and children's boarding houses 1915-1975” and “Children's Cultural Heritage - the visual voices of the archive”.

References

- Aapola, Sinikka, Marnina Gonick, and Anita Harris. 2005. Young Femininity: Girlhood, Power, and Social Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bartky, Sandra Lee. 1990. Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression. New York: Routledge.

- BBC. 2020. Greta Thunberg: Who is She and What Does She Want?”, last modified February 28. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-49918719.

- Borgerson, Janet L., and Jonathan Schroeder. 2002. “Ethical Issues of Global Marketing: Avoiding Bad Faith in Visual Representation.” European Journal of Marketing 36 (5/6): 570–594. doi:10.1108/03090560210422399.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Cann, Victoria. 2012. “Competing Femininities: The Construction of Teen Femininities in Magazine Adverts.” Networking Knowledge 5 (1): 59–83. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/53738/.

- Carey, Renee N, Ngaire Donaghue, and Pia Broderick. 2011. “‘What you Look Like is Such a big Factor’: Girls’ own Reflections About the Appearance Culture in an all-Girls’ School.” Feminism & Psychology 21 (3): 299–316. doi:10.1177/0959353510369893.

- Carter, Gynthia, and Linda Steiner. 2004. “Mapping the Contested Terrain of Media and Gender Research.” In Critical Readings: Media and Gender, edited by Cynthia Carter, and Linda Steiner, 11–36. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Cook, Daniel Thomas. 1999. “The Visual Commoditization of Childhood: A Case Study of a Children’s Clothing Trade Journal, 1920s-1980s.” Journal of Social Sciences 3 (1–2): 21–40. doi:10.1080/09718923.1999.11892220.

- Driscoll, Catherine. 2002. Girls: Feminine Adolescence in Popular Culture & Cultural Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Durham, Meenakshi Gigi. 2007. Sex and Spectacle in Seventeen Magazine: A Feminist Myth Analysis.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Feminist Scholarship Division, San Francisco, CA.

- Egan, R. Danielle, and Gail Hawkes. 2008. “GIRLS, SEXUALITY AND THE STRANGE CARNALITIES OF ADVERTISEMENTS.” Australian Feminist Studies 23 (57): 307–322. doi:10.1080/08164640802233278.

- Formark, Bodil, Heta Mulari, and Myry Voipio. 2017. “Introduction: Nordic Girlhoods—New Perspectives and Outlooks.” In Nordic Girlhoods: New Perspectives and Outlooks, edited by Bodil Formark, Heta Mulari and Myry Voipio, 1–22. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan

- Gauntlett, David. 2008. Media, Gender and Identity: An Introduction, 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Genz, Stéphanie, and Benjamin A. Brabon. 2009. Postfeminism: Cultural Texts and Theories. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007a. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007b. “Postfeminist Media Culture.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 147–166. doi:10.1177/1367549407075898.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2008. “Empowerment/Sexism: Figuring Female Sexual Agency in Contemporary Advertising.” Feminism & Psychology 18 (1): 35–60. doi:10.1177/0959353507084950.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2017. “The Affective, Cultural and Psychic Life of Postfeminism: A Postfeminist Sensibility 10 Years On.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 20 (6): 606–626. doi:10.1177/1367549417733003.

- Gill, Rosalind, and Christina Scharff. 2011. “Introduction.” In New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity, edited by Rosalind Gill, and Christina Schraff, 1–17. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- GinaTricot. 2016. Sustainability Report 2016. https://www.ginatricot.com/cms/work/sustainability/policys/ginatricot_hallbarhetsredovisning2016_eng_low.pdf.

- GinaTricot. 2019. Sustainability Report 2019. https://www.ginatricot.com/cms/work/sustainability/policys/Gina-Tricot-Hallbarhetsredovisning-2019_low.pdf.

- Graff, Kaitlin A., Sarah K. Murnen, and Anna K. Krause. 2013. “Low-Cut Shirts and High-Heeled Shoes: Increased Sexualization Across Time in Magazine Depictions of Girls.” Sex Roles 69 (11–12): 571–582. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0321-0.

- Grande, Ariana. 2018. Thank u, next. YouTube video, 5:30. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gl1aHhXnN1k.

- Griffin, Christine. 2004. “Good Girls, Bad Girls: Anglocentrism and Diversity in the Constitution of Contemporary Girlhood.” In All About the Girl: Culture, Power, and Identity, edited by Anita Harris, 29–44. New York: Routledge.

- Harris, Anita. 2004. Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Routledge.

- Harris, Anita, Sinikka Aapola, and Marnina Gonick. 2000. “Doing it Differently: Young Women Managing Heterosexuality in Australia, Finland and Canada.” Journal of Youth Studies 3 (4): 373–388. doi:10.1080/713684386.

- H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) Group. 2017. H&M Group Sustainability Report 2017. https://sustainabilityreport.hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/HM-Group-Sustainability-Performance-Report-2019.pdf.

- H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) Group. 2019. H&M Group Sustainability Performance Report 2019. https://sustainabilityreport.hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/HM-Group-Sustainability-Performance-Report-2019.pdf.

- Holland, Patricia. 2004. Picturing Childhood: The Myth of the Child in Popular Imagery. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Horton, Kathleen. 2018. “Just Use What You Have: Ethical Fashion Discourse and the Feminisation of Responsibility.” Australian Feminist Studies 33 (98): 515–529. doi:10.1080/08164649.2019.1567255.

- KappAhl. 2018. KappAhl: Annual Report 2018. https://www.kappahl.com/globalassets/corporate/investors/annual–interimreports/20172018/kappahl_2018_eng_del1.pdf.

- KappAhl. 2019. Annual Report 2019: Operations Sustainability Earnings. https://www.kappahl.com/globalassets/corporate/investors/annual–interim-reports/20182019/kappahl_annual_report_2019/.

- Knoll, Silke, Martin Eisend, and Josephine Steinhagen. 2011. “Gender Roles in Advertising: Measuring and Comparing Gender Stereotyping on Public and Private TV Channels in Germany.” International Journal of Advertising 30 (5): 867–888.

- Knudsen, Gry Høngsmark, and Erika Kuever. 2015. "The Peril of Pink Bricks: Gender Ideology and LEGO Friends.” In Consumer Culture Theory (Research in Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 17). edited by Anastasia E. Thyroff, Jeff B. Murray, Russell W. Belk, 171–178. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Korsvold, Tora. 2012. “Revisiting Constructions of Children and Youth in Marketing Advertisements.” Young 20 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1177/110330881102000101.

- Lindén, Lisa. 2013. “‘What Do Eva and Anna Have to Do with Cervical Cancer?’ Constructing Adolescent Girl Subjectivities in Swedish Gardasil Advertisements.” Girlhood Studies 6 (2): 83–100. doi:10.3167/ghs.2013.060207.

- Lindex. 2019. “Lindex Launches New Code of Conduct with Focus on Gender Equality | Lindex Group,” Last Modified October 15. https://about.lindex.com/press/news-and-press-releases/2019/lindex-launches-new-code-of-conduct-with-focus-on-gender-equality/.

- Lindex. 2020. Lindex Sustainability Report 2020. https://about.lindex.com/files/documents/ lindex-sustainability-report-2020.pdf.

- Martínez-López, Francisco J., Rafael Anaya-Sánchez, Irene Esteban-Millat, Harold Torrez-Meruvia, Steven D’Alessandro, and Morgan Miles. 2020. “Influencer Marketing: Brand Control, Commercial Orientation and Post Credibility.” Journal of Marketing Management 36 (17–18): 1805–1831. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2020.1806906.

- McRobbie, Angela. 1997. “More! New Sexualities in Girls’ and Women’s Magazines.” In Back to Reality: Social Experience and Cultural Studies, edited by Angela McRobbie, 190–209. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2008. “YOUNG WOMEN AND CONSUMER CULTURE.” Cultural Studies 22 (5): 531–550. doi:10.1080/09502380802245803.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2009. The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Merskin, Debra. 2004. “Reviving Lolita?” American Behavioral Scientist 48 (1): 119–129. doi:10.1177/0002764204267257.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2000. “The Multiple Viewpoint: Diasporic Visual Culture.” In Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews, edited by Nicholas Mirzoeff, 1–19. London: Routledge.

- Molander, Susanna, Ingrid Östberg, and Ingeborg Astrid Kleppe. 2019. “Swedish Dads as a National Treasure: Consumer Culture at the Nexus of the State, Commerce, and Consumers.” In Nordic Consumer Culture State, Market and Consumers, Edited by Søren Askegaard and Jacob Östberg, 119–146. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04933-1

- Montgomery, Kathryn C., Jeff Chester, and Tijana Milosevic. 2017. “Children’s Privacy in the Big Data Era: Research Opportunities.” Pediatrics 140 (2): S117–S121.

- Nguyen, Terry. 2021. “Gen Z Doesn’t Know a World without Fast Fashion.” https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2021/7/19/22535050/gen-z-relationship-fast-fashion.

- Omnicoreagency.com. 2021. “Facebook by the Numbers: Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts,” last modified July 19, 2021. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/facebook-statistics/.

- Ortner, Sherry B. 1972. “Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?” Feminist Studies 1 (2): 5–31.

- Österlund, Mia. 2012. “Nordic Girlhood Studies: Do We Need to Get Over the Pippi Longstocking Complex?” In Peripheral Feminisms Literary and Sociological Approaches, edited by Petra Broomans and Margriet van der Waal, 35–42. Groningen: Centre for Gender Studies, Euroculture, Globalisation Studies. https://www.rug.nl/research/globalisation-studies-groningen/publications/researchreports/reports/peripheralfeminisms.pdf.

- Pirsch, Julie, Shruti Gupta, and Stacy Landreth Grau. 2007. “A Framework for Understanding Corporate Social Responsibility Programs as a Continuum: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Business Ethics 70: 125–140. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9100-y.

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Schroeder, Jonathan E. 2002. Visual Consumption. London and New York: Routledge.

- Schroeder, Jonathan E., and Detlev Zwick. 2004. “Mirrors of Masculinity: Representation and Identity in Advertising Images.” Consumption Markets & Culture 7 (1): 21–52. doi:10.1080/1025386042000212383.

- Sparrman, Anna. 2018. Visual Discourse Analysis I & II: To Research Image and Visuality. PowerPoint Presentation. Linköping: Linköping University.

- Speno, Ashton Gerding, and Jennifer Stevens Aubrey. 2018. “Sexualization, Youthification, and Adultification: A Content Analysis of Images of Girls and Women in Popular Magazines.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95 (3): 625–646. doi:10.1177/1077699017728918.

- Stevens, Lorna, and Jacob Ostberg. 2012. “Gendered Bodies— Representations of Femininity and Masculinity in Advertising Practices.” In Marketing Management: A Cultural Perspective, edited by Lisa Peñaloza, Nil Toulouse, and Luca M. Visconti, 392–407. London: Routledge.

- Thomas, Dana. 2019. Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes. New York: Penguin Press.

- United Nations General Assembly. 1989. “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” United Nations, Treaty Series 1577 (3): 1–15.

- Vänskä, Annamari. 2017. Fashionable Childhood: Children in Advertising. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2020. Global Gender Gap Report 2020. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf.