ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to explore social discourse on “green” consumption in Spain by analysing how guilt and logic of practice are involved in this type of consumption from a psycho-sociological perspective. The empirical work was qualitative: we analysed 14 focus groups and nine interviews with “green” and “non-green” consumers from different social backgrounds. The results show that “green” consumption involves a dual process of social differentiation and guilt, especially in “greener” consumers from middle and middle-upper class social backgrounds, whose discourse is developed in socio-environmental terms. These findings question whether “green” consumption is an effective element within a transformative environmental policy.

Introduction and objectives

There is currently a large volume of research on “green” consumption (Zang and Dong Citation2020; Lorenzen Citation2014). Most work relating “green” consumption to environmentally-friendly practices has focused on consumers’ reflexivity and bounded rationality (Zang and Dong Citation2020; Moser Citation2016; critically: Zollo Citation2021). Based on theories of reflexive modernity and risk (Giddens Citation1991; Beck Citation1992), “green” consumption has been analysed as a self-reflexive strategy adopted by consumers oriented towards conservation of the environment (Böstrom et al. Citation2017; Conolly and Porthero Citation2008). In line with this, “green” consumption has also been analysed as a particular form of political action (Böstrom et al. Citation2019) linked to ethical forms of consumption and the exercising of citizenship (Saraiva, Fernandes, and Schwedler Citation2021; Rief Citation2008). The manifestations of these forms of consumption comprise different practices, from boycotts and/or support for certain products, the purchase of products with the “green” certificate and/or from local producers, and so on (Lorenzen Citation2014), to attitudes, where the construction of identities and social networks around more “simple” or “austere” lifestyles would play a central role (Perera, Auger, and Klein Citation2018; Horton Citation2003; Connolly and Porthero Citation2003).

These approaches, which are undoubtedly relevant, explain the phenomenon mainly from its reflexive and rational-cognitive dimension (Zollo Citation2021; Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016). It is widely believed, for example, that “green” consumers are more supportive, ethical and altruistic (Saraiva, Fernandes, and Schwedler Citation2021; Fuentes and Sörum Citation2019; Başgöze and Özkan Citation2012; Carrington, Neville, and Whitwell Citation2014), interpreting that their attitudes imply the renunciation of personal benefit in favour of the environment, although some inconsistencies in consumer attitudes and behaviours have also been identified (Chen et al. Citation2016; Connolly and Porthero Citation2008). All that being said, however, the above works do not make sufficient issue of, nor question, the origins of these moral reflective values, or the individualized and sovereign framework of consumer behaviours. Taken together, these analyses tell us little about the motivational logics underlying “green” consumption, or the effect of consumers’ social positions in this regard.

This article takes the above observations as a starting point to explore Spanish consumers’ social discourses on “green” consumption, with the ultimate aim of unravelling the role that guilt and logic of practice play in this regard. As we shall see, despite more attention having been paid to them in recent years, the relevance of these elements to an overall interpretation of “green” consumption has yet to be sufficiently established. The justification for focusing the work on these two aspects is, firstly, their growing presence in the literature as factors that help explain “green” consumption. And secondly, the need to shed light on the processes of “individual responsibility” and “containment” typical of “green” discourses when it comes to consumption, in order to understand what factors these processes are in response to, and why “green” consumption is associated with contradictions such as those that define it as a “difficult and demanding” type of consumption (Moisander Citation2007; Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016; Denegri-Knott, Nixon, and Abraham Citation2018). The study of guilt, especially in its unconscious forms, can provide some interpretive clues as to the meaning of “green” consumption not taken into account by previous research. We therefore emphasize that the discourses and attitudes of “green” consumers should not be understood in terms of moral and rational aspects alone, but also be related to unconscious emotional components.

Furthermore, the role of emotions and the effect of consumers’ social positions have traditionally been explored separately. In contrast, here we propose a joint approach that allows us to explore the relationship between the two aspects. Studying logics of practice can illuminate the socio-symbolic principles of “green” consumption, while also allowing us to gauge the extent to which guilt may be related to symbolic domination (Malier Citation2021; Anantharamant Citation2018; Brand Citation2010). Although our analysis focuses on these two issues, we also outline the main discursive elements of “non-green” consumers in order to observe the main differences with respect to their “green” counterparts.

This work centres around an exploration of discourses developed in the recent history of consumption in Spain. Here we explore those discourses developed years after the 2008 economic crisis to identify guilt and certain logics of practice as underlying elements of the new forms of “green” consumption in a sociohistorical and discursive context of rupture from the consumerist “excesses” existing prior to said crisis (Alonso, Fernández Rodríguez, and Ibáñez Citation2015; Barbeta-Viñas Citation2022). This approach contributes to understanding why, despite its growth in recent years, “green” consumption continues to be a niche form of consumption in markets such as Spain (Mapama Citation2017) and not a phenomenon that penetrates all groups and social strata, regardless of the central role that environmental problems have acquired in the public debate.

In the present context, with the ecological crisis at the heart of many academic and political debates, the implications of this work may be relevant for discussing and rethinking some social and environmental policies. They also shed light on the complexity and multidimensionality of the motivational processes of “green” consumption, thus advancing the understanding of the bases of consumers’ attitudes in contexts of crisis (Moisander Citation2007). This information may not only be of interest in promoting sustainable consumption patterns and rethinking marketing approaches, but may also invite reflection on the limits of “green” consumption as a factor of social change, (Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016), and a more critical approach to research on the phenomenon itself.

Theoretical review

The guilt in “green” consumption

The literature has gradually come to agree that feelings of guilt are linked to “green” consumption, symbolically aligned with values of environmental sustainability (Wonneberger Citation2018). Guilt in consumption corresponds to the subjective acknowledgment of having done or desired something that does not meet moral standards. The feeling of guilt may thus be related to self-discipline, moral responsibility, self-control, or to having, or not having, some or other attitudes to consumption (Dedeoglu and Kazançoglu Citation2010). Empirical work published in recent years indicates that the role of guilt in “green” consumption involves significant multidimensional complexity. To begin with, guilt emerges in these consumption processes while constructing identities and consumption styles full of contradictions and dilemmas (Bray, Johns, and Kilburn Citation2011). In today's consumer societies, the chances of experiencing guilt or moral weakness because of a missing attitude, such as not consuming environmentally friendly products, have greatly increased (Cremin Citation2012). This suggests that the phenomenon of “green” consumption tends to develop in an individualized context, in which individual responsibilities within consumption styles are considered a solution to environmental problems (Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016).

It has been stated that in this case the norms and moral values related to the environment are key factors in the link between guilt and “green” consumption (Sharma and Paço Citation2021; Peloza, White, and Shang Citation2013). Several studies indicate that guilt is a regulating feeling for pro-environmental behaviour and empathy. In these cases, “green” consumption helps consumers to not feel guilty and to move away from hedonistic consumption, or it plays a key role in regret, it being understood that it is a “guilt-free” consumption practice, central to consumers’ moral identity (Beserra de Lima, Ribeiro, and Rocha Citation2019; Newman and Trump Citation2017; Antonetti and Maklan Citation2014). Other work has found that “green” consumption acts as a compensatory regulator of consumers’ dissonance and anticipatory guilt (Gregory-Smith, Smith, and Winklhofer Citation2013). However, in the presence of barriers to “green” consumption, morals and guilt can lead to psychological distress in consumers (Sharma and Lal Citation2020). These results are consistent with studies that have found narratives of guilt redemption among “green” consumers (Fontanelle Citation2013), or phenomena of “interpassivity” in which guilt is delegated to the goods themselves by paying more money to maintain moral integrity (Haynes and Podobsky Citation2016).

Another interesting but little explored avenue is the psychoanalytic analysis of the role played by unconscious guilt. Chatzidakis (Citation2015) and Chatzidakis, Shaw, and Allen (Citation2021) have proposed that “depressive guilt” would form part of the motivational origins of ethical consumption. On the other hand, some empirical investigations have found indications of a more punitive model of guilt, close to the Freudian one (Barbeta-Viñas Citation2015). As Freud (Citation1929) stated in his famous Civilization and its discontents, it seems that we cannot take the existence of primary moral feelings in individuals for granted, but rather that they respond to unique emotional orientations. According to Freud, morality can be situated on a conscious level when guilt and regrets are experienced for having acted improperly. This is the level of analysis of dominant guilt in research on green consumption. But it can also be situated at the unconscious level, when something illegitimate is desired for the individual, and guilt manifests as a need for punishment, rather than remorse.

Logic of practice and social differentiation in “green” consumption

The line of sociological research that focuses on structural logics has established “green” consumption as a space for social and symbolic struggle; a field comprising a dynamic structure of positions that struggle to build systems of legitimacy and conceptions about the world, in this case, in consumer relations (Bourdieu Citation2000, 120). The conception of “green” consumption arising from each social position would not only aim to be hegemonic, but would be built from the mobilization of the different and unequal levels of capital (economic, symbolic, cultural) that consumers have, and would obey particular logics of practice. Bourdieu (Citation1990) defined logic of practice as those systematic elements that lend meaning and plausibility to actions, and that tend to guide perceptions, practices, and with them, the expression of preferences. According to this French sociologist, logic of practice arises from the confluence between the habitus and different fields, constituting that which provides meaning in the social game of a specific field such as consumption. Beliefs and assessments regarding a field linked to a logic of practice are therefore not fully conscious elements thought out rationally and reflexively, but rather respond to certain social conditions of existence. Thus, a logic of practice can be understood as a principle of action that, in the context of a field, acquires both a subjective and an objective sense: it acts as “common sense” and a guiding principle for individuals’ values and actions (Bourdieu Citation1990, 113–116). From this perspective, in some consumers logics of practice can promote the ability to value and choose “green” products due to the close evaluative familiarity that they bring with them in their reference groups, and due to the possibilities that these allow consumers to position themselves within the social and symbolic structure.

Near this framework, empirical research has been developed that shows how this type of consumption is used as a differentiation and assimilation strategy according to consumers’ social status, particularly among those with high levels of cultural capital (Yan, Keh, and Chen Citation2021; Elliott Citation2013; Laidley Citation2013; Brand Citation2010). Generally speaking, these results are consistent with those of other recent studies that have observed a relationship between socioeconomic status and pro-environmental attitudes (Grandin et al. Citation2022). That being said, according to the results provided by Elliott (Citation2013), differentiation-oriented logics should not always be understood as traditional forms of conspicuous consumption: what is though to be at stake in such consumption is the unintended demonstration of “austerity”; that is, an expression of the logic of practice employed by consumers with high cultural capital. In line with this, we find studies such as that conducted by Griskevicius, Tybur, and Bergh (Citation2010), who highlighted the “conspicuous altruism” involved in “green” consumption, as well as others that reveal the role played by the latter in symbolic differentiation between social groups (Malier Citation2021; Caniëls et al. Citation2021). Recent works have questioned whether these “green” and simple forms of consumption convey distinction or are ideologically oriented to hide social class differences (Thompson and Kumar Citation2020; Eckhardt and Bardhi Citation2020).

In a similar theoretical line, important differences have been reported in discourse on and perceptions of green consumption between groups with high social status, which embody an “eco-habitus” that would underly the moral and reflective schemes favourable to green consumption, and classes with low status, who express “eco-impotenc,” that is, uncertainty in the face of environmental problems and a perception of the scarce relationship between their daily actions and global sustainability problems (Kennedy and Givens Citation2019; Anantharamant Citation2018).

Sensitizing concepts and research proposition

The literature outlined so far informs us of the relevant role that guilt and logic of practice play in green consumption. Both are employed as sensitizing concepts in this work. The American sociologist Harold Blumer defined such concepts as those that guide analysis by providing conceptual starting points with which to explore or analyse empirical data (Bowen Citation2006). Guilt provides us with a theoretical orientation to focus on the motivational genesis underlying the morality of green discourses, particularly those forms of unconscious guilt that consumers might feel in the face of desires experienced as contradictory and illegitimate. On the other hand, logics of practice point to the possibility that green consumption obeys an essentially differentiating logic between consumers, its effects being more linked to the social exclusion of “non-green” sectors than to reduction of the carbon footprint.

In accordance with this approach, we ask the following questions: what is behind discourses that celebrate the relationship between “green” consumption and sustainability, while at the same time expressing green consumption as an arduous task? Does green consumption express logics of practice linked to social and symbolic differentiation by consumers? And finally, can guilt play the role of a differential value in green consumers? In response to these questions, we adopt the following research propositions regarding the meaning of the discourses, which be developed in the results section: (1) in certain discourses on “green” consumption, feelings of guilt are expressed (consciously or not) that motivationally guide consumers towards this type of consumption; and (2) a certain construction of “green” consumption responds to a logic of practice that is based on symbolic struggles between social groups.

Methodology and design

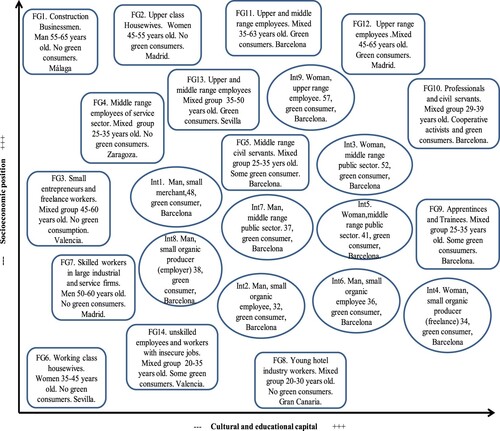

Our empirical research followed a socio-motivational approach combining empirical observation and theoretical reflection. This approach was based on an analysis of the motives, norms and values that guide consumer attitudes and behaviour. Its aim was to provide a sociological and motivational interpretation of the social meaning of consumption processes. This approach is especially useful for the analysis of consumption processes at different levels. We did not, however, analyse individuals’ motives or impulses, but rather carried out psycho-social analysis in which the cultural-symbolic and ideological formations (such as values, norms and consumer habits), produced in certain social environments (see ), condition the emotional dynamics experienced by consumers with a greater or lesser degree of awareness.

Qualitative analysis methods and techniques were necessary. The objectives of the study called for the recording and analysis of consumers’ social discourse. To this end, the techniques employed were the focus group (FG) and the semi-structured interview, as traditionally used in sociology (Krueger and Casey Citation2015; Tadajewski Citation2016). Both techniques allow us to investigate the ways in which individuals collectively make sense of a social phenomenon such as “green” consumption, and construct meanings around it in the micro-context of focus groups and interviews. The discourse that emerged from these conversational dynamics was explored and interpreted as key elements reflecting the macro-social contexts represented by the individuals interviewed. For this reason, it was important to maintain the participants’ anonymity within the groups; we wanted them to pool their discourse until consensus or fractions were reached. And this discourse was not attributable to individuals alone, but to the participants as members of specific social groups (Ruiz Citation2018; Ibáñez Citation1979). We did not, therefore, explore an aggregated individual discourse nor apply a strictly linguistic analysis to the texts arising from the FGs and interviews. We instead focused on analysing a symbolic and discursive universe linked to specific social groups and contexts, to explore in them social descriptions of “green” consumption and the socio-structural and emotional factors that condition them. The sampling was therefore structural (Ibáñez Citation1979): by means of the FGs and the interviews, a representative sample of the main social groups in Spanish society was created to observe from which social backgrounds discourse in favour of “green” consumption emerged and by means of which psycho-social logic it took on meaning; that is, to what extent guilt and differentiation play a relevant role.

The FGs and interviews subjected to analysis were taken from three different and independent research projects. In total, there were 14 FGs and 9 interviews. Interviewee recruitment involved the administering of questionnaires to determine consumers’ socio-demographic characteristics and their relationship with “green” consumption, combining (a) contact made by specialized companies using anonymous pre-made lists of citizens; and (b) the snowball method via the researcher’s own networks (see Table 1A).Footnote1

The first research project (Project 1) provided 2 FGs and 9 interviews with “green” consumers, mostly from middle and upper-middle class social backgrounds. It was conducted by the author of this paper, who participated in all phases of the fieldwork, and enquired about the practices, meanings and motives behind “green” consumption.

The second project (Project 2) provided 9 FGs of consumers with different social characteristics (see ); some of the groups only comprised “green” consumers. The stimuli for the debate focused on the effects that the economic crisis had had on consumption in Spain, with the aim of delving deeper into aspects of “green” consumption and uncovering social perceptions on “green” consumption among “green” and “non-green” consumers. It should be added that this project produced relevant results (e.g. Alonso et al. Citation2014, Citation2015).

The third project (Project 3) contributed 3 FGs, two from an upper-middle class and one from a lower-middle class background; all three had a significant number of “green” consumers. The aims with the FGs were to determine the future possibilities of this type of consumption and what might hold it back, as well as its link to broader ideologies within the framework of the consumer society in Spain (Colectivo IOÉ Citation2013).

The FGs were set up and held following these guidelines: groups of between 7 and 10 people; each FG lasted approximately two hours (one and a half hours for the interviews); the FGs were recorded, with subsequent verbatim transcription, as were the interviews. Following the criteria of the type of sample discussed earlier, internally homogeneous groups were used, but with sufficient heterogeneity among the participants to cover a wide range of backgrounds and social discourses. The variables considered in the selection of participants were gender (with mixed and non-mixed groups), socio-economic background, level of education, age, and, in some cases, to what degree they practise “green” consumption (with its different names: responsible, sustainable, ethical, etc). All the groups were held between 2010 and 2013 in major Spanish cities (see and Table 1A). There was a strategic reason for analysing a corpus from these dates. During those years, Spanish society was in the middle of a deep economic crisis that had a strong impact on consumer relations, and the climate crisis was already being debated publicly. In this historical context, finding discourse in which “green” and sustainability issues had a strong legitimacy among the population as a whole was to be expected, as was finding the social and emotional logic that are typical and common among “green” consumers. The work plan was, precisely, to take advantage of this historical situation in order to elucidate, a priori in a more obvious way, how blame and certain logics of practice were articulated through discourses around “green” consumption following a crisis that had truncated the population’s consumption habits.

We are aware of the particular nature of the data set, in that we drew on studies that are independent of each other and with different original objectives. However, the use of secondary data in qualitative research has gained ground in recent years. The opportunities provided by digital technology for storing and accessing large amounts of data, as well as the sometimes underfunding of research, are among the main reasons for this increase (Ateeq Citation2021; Hughes and Tarrant Citation2019). In this case, the use of data from different projects enabled the formation of a corpus of texts that is broad enough to cover most social backgrounds, as well as to extend the comparison with conjectures arising from earlier, less empirically based work. This should not, however, be confused with attributing statistical representativeness to the results. The use of these secondary sources made it possible to compare data from different projects, to monitor their coherence, and to develop new research questions and objectives. We believe that in the case of this study, the sharing of methodological postulates by academic networks involved in qualitative research facilitated this strategy. The FGs and interviews were, in all cases, relatively smooth, open and less directed than a focus group that follows the Morgan model (Citation1993). It was therefore no impediment that the exploration of guilt and logics of practice was not explicit in the objectives of the original investigations, since they were worked on as aspects emerging from the discourses. Thus, as we have already pointed out, the analysis was guided by our conjecturing on the possible emergence of these aspects in social discourses on “green” consumption.

To explore the data, we focused on psycho-socio-hermeneutic sociological discourse analysis (Alonso Citation2013; Conde Citation2009; Barbeta-Viñas Citation2020). This approach is especially valuable for analysing the dimensions of meaning and emotion in social phenomena. Broadly speaking, this analysis combines, on the one hand, a semantic (textual) approach, where it is possible to explore the socio-cultural and ideological level of the discourse, thereby understanding the semanticization of experience and the valuation and rationalization processes of the participants in their interactions and in their use of certain linguistic codes, and, on the other hand, but coordinated with the previously described approach, a pragmatic (contextual) and expressive approach, whereby attention is paid to the different social and emotional contexts of discursive production. In other words, understanding how contexts are part of the conversation as an integral element of the semantic structure (Voloshinov Citation1976), as well as recording the emotional attitudes and feelings of the participants in the discourse. In the latter case, we drew on some conceptual tools from the psychoanalytic model for the social interpretation of emotional and non-conscious processes (Stamenova and Hinshelwood Citation2018).

The main limitations of the study should be mentioned, since they are related to the methodological approach. Firstly, the aim was to capture the social meanings of “green” consumption by analysing discourses; however, the factual dimension of the behaviours studied has not been analysed, for which an ethnographic approach would be necessary. Secondly, the use of empirical material from various research projects weakened the possibility of focusing more specifically on the specific interests pursued by the present work.

Results: interpretative analysis

Between 2010 and 2013, the years when the fieldwork was carried out, Spain went through a very serious economic crisis that put the brakes on the differentiating overconsumption of the previous period. At this time, discourse about consumption was generally marked by the material restrictions brought about by the crisis: dominated a disciplining, moralizing, and blaming discourse associated with the “excesses” of consumption in previous years was dominant (Alonso, Fernández Rodríguez, and Ibáñez Citation2015). However, as observed in social discourses, “green” consumption and its legitimization had not reached most of the population. In the FGs without “green” consumers, especially those with medium to low cultural capital, there were not even clear, positive references to “green” consumption, let alone the possibility of practising it. The majority of society found it difficult to pivot the critique of the wastefulness of the previous years to environmental sustainability, and even more so via actual “green” consumption (Alonso, Fernández Rodríguez, and Ibáñez Citation2014). The discourse associated with “green” consumption and “sustainability” belonged to specific social sectors, so that “green” consumption corresponded to a very particular niche of consumption within the hyper-segmented context of the Spanish consumer market, rather than to a generalized type of consumption practised by the majority of society. This is consistent with the quantitative data about the profile of the “green” consumer in Spain (Mapama Citation2017), as well as those taken from research conducted in other countries (Grandin et al. Citation2022; Kennedy and Givens Citation2019; Elliott Citation2013).

For the sake of explanation, we divided the two processes for analysis described above into the following sections: firstly, analysis of the role of guilt as an emotional underlier of “green” consumption; secondly, analysis of basic logic of practice found in “green” discourse.

From virtuous ethics and morality to self-punishment: guilt in “green” consumption

Guilt in the socio-motivational process of “green” consumption tended to appear as a particular dimension of the discourse which, consistent with the literature cited above, grounded this type of consumption in a socio-environmental code. “Green” consumption was identified in this discourse as a reaction to “consumer capitalism” and its impact on environmental sustainability. Despite having this correlation to reaction, it is a practice that is effectively linked to a reflective dimension whereby, as Connolly and Porthero (Citation2008) observed, consumers perceive possibilities of acting in favour of the environment and equitable social development through consumption. However, the concrete ways these “green” consumers expressed the reasons for their actions and the extent of their impact showed a certain amount of ideological and discursive variability.

Activist discourse in “green” consumption

On the one hand, among middle and upper-middle class, educated “green” consumers (FGs 10, 11, 12, 13; interviews 1, 4, 6), some of whom were consumer cooperative activists, the ideologeme of “green” consumption as a practice at the service of “eco-social transformation” was observed. For them, being “green” meant going way beyond recycling or consuming products labelled as “green,” which is how it was identified by participants from lower-middle class or uneducated backgrounds (FGs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6). It instead implied a commitment to “building alternatives,” to “new social, economic and environmental models” (FGs 10, 12, interviews 1, 4, 6). This discourse even tended to equate “green” consumption with a form of “struggle.” In the context of consumer cooperatives, this took on a sense of the collective, the communal and the organized, shifting the meaning of “green” consumption to the semantic space of political practice, as other authors have argued (Böstrom et al. 2019).

From this perspective, “green” consumption encapsulated a set of practices that these consumers carried out in their daily lives. As they stated, these practices, especially those related to consumption, had direct effects on the environment and social inequality. Beyond their buying habits, “green” consumption was expressed by these consumers as social spaces – both physical and symbolic – where “networks” were created among those who shared values and sustainable lifestyles (Horton Citation2003). In these spaces, which often refer to themselves as “green” consumer cooperatives, causes, values, norms of consumption and products were shared which, they argued, involved “contradicting the logic of capital” (FG 10), “transforming unjust relationships” (interview 1), or “considering the product’s impact until it reaches me” (FG 12). This pragmatic dimension of the implications of consumption was central to this discourse; consumption was not only defined as buying certain products labelled as “green,” but by a holistic attitude to consumption that followed rules associated with defending socio-environmental values.

Our consumer FGs linked to these consumption networks tended to agree on a discourse in which “green” consumption was to be found in a symbolic public space, where it was defined as a key and central tool in the battle against the socio-economic and environmental problems that, according to them, beset the world. Profit was the basis of capitalism and was defined as one of the key vectors for the (de)legitimization of “green” consumption; “green,” they stated, not only involved controlling pesticides, additives and transgenics, but being “fair and sustainable,” and therefore, legitimately in their opinion, not subject to the logic of profit: “The added value of a “green” product is lost because it is part of the chain and I know it is a business” (FG 12). This discourse also referred significantly to “anti-consumption” (FGs 10, 13) to express the failure to which the consumerist model of consumption was condemned. This expression inherently opened up a symbolic space with rules of what, from their ideological standpoint, legitimate non-consumerist consumption should be, which is precisely where “green” consumption is expressed. From a clear, rhetorical point of view, the ethical foundation of this discourse included “green” in the framework of discussion about the organization of society.

M (Men): Of course, if you go to the supermarket, you’re giving money to food multinationals, to food distribution multinationals, and you’re favouring an economic model that’s based on profit, it’s based on wanting to make money …

W (Women): Yes, yes …

M: … and it’s like that, and this is the basis of the capitalist system, the profit motive. If you consume from a local producer, you’re trying to establish much fairer exchange relationships, much more (…), which is very, very different from the logic of the capitalist system. (FG 10)

M: That it’s not for profit. The key is profit. (FG 12)

Individualistic moral discourse on “green” consumption

On the other hand, a second discourse arose from the FGs and interviews with “green” consumers from middle and upper-middle class backgrounds with higher education (FGs 11, 12, 1 3, 5; interviews 2, 3,5, 7, 8, 9) but with a lower degree of activism, where “green” consumption was linked in a more ambiguous way to the individual possibilities of moral action; that is, “helping,” “doing good in the world,” “doing something” in the face of problems with negative connotations such as domination by large corporations, excessive consumerism or the energy crisis. In this discourse, “green” consumption seems to move away from justice, from public projects, to be limited to individualized visions of morality, solidarity, and altruism, often connected to a self-satisfying experience: when one consumes “green” one is doing something “good,” and this is gratifying for the consumers themselves on a personal level. This type of consumption therefore corresponds to a Weberian model of individual evaluative action. The success of this action depends on the sum of individual acts of purchase, as expressed in FG 11 and FG 12 in analogy with voting. This discourse basically follows the sovereign and rational actor model of neoclassical economics: moral and rational will is what constructs our aggregate individual preferences in favour of “green” products (Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016; Alonso et al. Citation2014). Buying “green” is the beginning and the end of the same action, whose subjective rationale is to be found in the exercise of individual moral responsibility.

M: I would say so, in the sense that it makes you responsible, and if you’re a responsible person and you want to deceive yourself, you can deceive yourself, obviously, but at least it opens a door, a door to responsibility. (FG 11)

W: Yes, and then this feeling of responsibility has awakened, hasn’t it? And to feel good doing something responsible for the planet, that makes you feel satisfied. (Interview 3)

W: I also think that responsible consumption is what I do with my money. So, let's see, I have so much income that I try to give some of it back to certain people, or to certain things, to certain projects. (FG 12)

Guilt in discourses on “green” consumption: beyond remorse

Despite the ideological differences among these comments, the dimension of guilt is a common aspect that runs through them. As we have observed, this dimension of guilt comes from two basic socio-motivational conflicts in the consumption process. The first of these revolves around the question of “coherence,” an expression that appeared in some groups and interviews. For these consumers, “coherence” is a word for the ideal and aspirational framework in which they define their identity, particularly in relation to how they consume. In Freud's terms (Citation1933), it is a model of the ideal ego, in that it is an external model, defined by sustainability culture and ideology, with which these consumers identify and with which they try to conform. Thus, the meaning of “green” consumption is based on the projection of the value of socio-environmental “coherence” onto it, and for them the possibility of approaching this ideal model. However, the comments reveal the presence of a conflict around the “(in)coherence” of their own practices and lifestyles, which they often verbalize with this same signifier.

As an ideal model to be followed, contradictions arise for consumers when their consumption practices deviate excessively, in their opinion, from their own ideal based on more or less strict environmentalist values, and this is when the feeling of guilt may emerge. Despite the fact that the “green” consumers in our research had “green,” partly “austere,” even, in some cases, “ascetic” lifestyles, their comments show the difficulties associated with consumption habits typical of their middle and upper-middle class social backgrounds: difficulties in refraining from purchasing certain goods and only making “green” purchases for reasons not linked to budget; difficulties in reaching a consensus in the FGs on what would be “rational and sustainable use” of certain goods that they themselves use but recognize as not being very sustainable (mobile phones, computers, cars, etc.) (FGs 10, 13); the “poor sustainability” of certain needs they recognize they have, such as consuming certain goods in quantity (FGs 9, 13); etc. Thus, the discourses reveal doubts about the “coherence” of their actual consumption, linked to the system of tastes and desires that guides them in their daily, and the ideal of the environmentalist self with which they identify emotionally.

M: … who has bought an Apple. One of my priorities is to take into account the company that sells it, I try to avoid multinationals at all costs, products that come from certain countries that I don't like, but I have a computer that’s an Apple, I don't like the company, but this computer has features like no other. I don't like the fact that it comes from the United States but … (FG 13)

W: Well, yes, it's very difficult to be coherent with everything, with what you buy, but yes, yes …

M: Well, maybe you can't be completely coherent but … yes, you can be fairly coherent. Sure, 100% is impossible but, I don't know … I know people from the A. de Gràcia [organic consumption cooperative], for example, and I’m sure you do too, who tell me they buy 80–90% of everything they consume through the cooperative. That’s a very high level of coherency and is very good. (…)

M: The point is to use things sustainably, rationally, and look … if you need it … that's it …

W: Exactly, what you can't do either is put on more … , no … I dress like this and I don't do anything else …

M: Sure, no, exactly … but …

M: Yeah, I also … I think what we’re doing is good, it's very good, I mean … I mean, it's something to be very happy about, setting up cooperatives, finding out about these things, changing consumer habits …

W: Of course, of course …

M: I find this revolutionary, and … I would look at it from a very positive perspective and say that this is great! Being completely coherent … Pfff! That’s impossible, that … (FG 10)

M: It's impossible, I think, to be completely coherent in all areas of your life, to say, I'm going to live in the mountains with an electric generator that generates exactly two kilowatts for …

M: But that's not coherence.

M: Why isn't it coherence?

M: Because you have to live somehow, because you have a family, I mean …

M: It's coherence when you think it is … . (FG 9)

W: … but recently, I've been reflecting more on over-consumption, because sometimes we consume things that are completely unnecessary … now I'm trying to reflect more on what I consume …

M: What do we need? Nobody can decide for anybody other than yourself because … (FG 12)

M: In the end you say: well, if part of my life is shopping, then I'm going to shop in places that I feel good about, not that make me feel a bit guilty … (FG 14)

On a second level of motivational overdetermination, the role of the ideal ego is reinforced by the super-ego. In this case, it is consumers’ identification with a socio-environmentalist super-ego in the orientation of their attitudes. As defined by psychoanalysis, this structure is linked to norms, self-restraints, moral conscience, and emotions such as guilt, which are linked to environmental sustainability in this case.

Among these same “green” consumers, there are different levels of evidence that allow us to conjecture the relevance of the super-egoic guilt dynamic in “green” consumption. On the one hand, the associative chain which the comments relate this type of consumption to basically corresponds to rules governed by socio-environmental values. Thus, the “ethical,” “responsible” or “conscientious” evaluations that “green” consumption should imply suggest the participation in a process of internalization of moral precepts through which this consumption passes. On occasions, these comments use the second person singular in key expressions, indicating the presence of the “you” as an objectification that consumers make of themselves. And as the psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas (Citation1987, 63) has pointed out, this type of discourse also reveals an object relation that is characteristic of the super-ego, with guilt as a latent element.

M: I would even apply that concept to not consuming more than you need (…), simply not wasting and not buying or acquiring products or objects that you’re not going to use, or that you’re going to use very little. Even if you don't think about the consequences, which is, of course, very important. So, for me, that would be a first level of responsible consumption (FG 12)

M: Something that it makes you is more aware of your inconsistencies …

M: One day I said: I'm going to be ethical about clothes …

M: It helps me to be more aware of my consumption,

W: I started organic meat and you try to be a bit like that … (FG 10)

M: You don’t like it, but you re-educate yourself, right? (Interview 1)

W: In the beginning, we had a lot of difficulties, because we began to consume not only fresh produce, but also “green” everything. So we had to make a lot of trips to get what we needed in each place. (FG 13)

Our interpretation suggests that what is happening in this discourse, in relation to the conflict between “non-green” consumer desires and the socio-environmentalist demands of the super-ego, is the manifestation of the unconscious feeling of guilt postulated by Freud (Citation1929). People experience this type of guilt for having desired something “bad,” something forbidden. And what indicates the presence of unconscious guilt is, as is the case with these “green” consumers to some extent, the need for punishment, not just conscious remorse, which is closer to the previous level. To the extent that “green” consumption is experienced as a compendium of abnegations, self-prohibitions and punishing demands, accompanied emotionally by expressions of suffering, it is an example of subordination to the socio-environmentalist super-ego and an attitude of deep guilt (“It’s hard; it implies a certain amount of effort.” FG 10).

W: I think what’s good is that we consume critically, above everything else. In the end we'll end up going to Zara or not, but we know what's what and that's what's important. And that you go to the cooperative and, and you consume local, ecological produce, such and such, of course … Well, we could sweat it and go every, once a week, consumption, fill the freezer and eat mashed beans and frozen onions. But we choose not to. I mean, within what would perhaps be more practical and more economical … it would be fantastic for everybody, because it would be that, but you say, within that, I prefer to build an alternative and, of course, from here and then, as I am in this alternative, I become (…) radical and an ecological fundamentalist … in the end it’s like that, you end up becoming … I mean, if you don't go crazy, I mean …

M: … of course, you get stressed …

W: … you can't do it, you get very stressed … Every day a thousand things (…)

W: You have to be there, battling, every day … (FG 10)

W: I acknowledge that, without being compulsive, you are seduced by the way the market offers you products. And sometimes you have to make an effort to … , well, to say: this is a matter of discipline, I have to do it, or of conscience. (FG 12)

W: And I am also sensitive to that, and when it’s April and there are grapes, from South Africa or Chile, I say: “grapes are in season in September and October, like heck we’re going to buy grapes in … ! I don't want grapes that have come by plane.” (FG 12)

M: It is everyone's individual responsibility. (…)

M: But you can read it as maybe someone who sees you and says, ah, look, this person is doing it, I'm going to do it too, there are people for everything, I for example am in favour of doing things even if others don't, I even feel better, look, these ten people don't do it but I do do it [“green” consumption].

M: You have to do it for yourself.

M: Well, that's why I feel better. (FG 9)

W: I try to find a balance between being aware of what I buy and what I eat and my relationship with the planet, without making too big a sacrifice. (FG 13)

Logic of practice in “green” consumption: social differentiation

The second question to be addressed in our analysis is how logic of practice in “green consumption,” orienting the “meaning of the game” in the process of social differentiation among consumers (Bourdieu Citation1990).

First of all, from our analysis, we detected discourse founded in ideological and symbolic distancing from social sectors that do not practise “green” consumption. What is happening here is not so much a process of ostentatious differentiation, but differentiation based on the projection of what we could call the “green habitus” on consumption practices whose connotations are associated with socio-environmental values (Kennedy and Givens Citation2019). Analysing the comments, we see how the dominant cultural-symbolic framework tends to focus evaluations on the forms of products, rather than on their substance, as Bourdieu (Citation1979) found in the processes of distinction. In our case, the appreciation of “green” products or attitudes is primarily based on judgements about the adequacy of the characteristics of the “green” products themselves over socio-environmental values: a “good” “green” product is an undeniably sustainable product in all its possible dimensions. This supposes the objectification of objects of consumption with regards to both the actual ideology of environmental sustainability and the economic, cultural, and symbolic capital of these middle and upper-middle class consumers.

The discourse on “green” consumption practices tends to assemble large amounts of information and complex knowledge about the different subfields that “green” tends to cut across. This is the case of food, in which “green” is intermingled with differentiating food particularisms specific to minority social groups: the processes of production and marketing of food or other products and their relationships with their impact on the environment, pollution, local farmers, etc; or citizen participation processes recontextualized and symbolically re-appropriated from consumer relations, also with differentiating effects (Horton Citation2003).

M: In other words, if we talk about ecological consumption, it is closely linked, or it has to be, at least as I experience it, it has to be closely linked to responsible consumption. Which means who the producer is, the mechanisms of production, how it gets to you, how local it is, responsible labour rights of the people who are working for the producer, the environment, what lifestyle you have …

M: … what responsible consumption implies is that you modify your consumption habits. Some habits, some ways of doing things, and also thinking about your needs (…) you have to restructure your daily life somehow. (FG 10)

These values therefore foster a (modifiable and non-substantialist) “green” identity in consumers, which develops in opposition to other values associated with conventional consumption, specifically Fordist, standardized, mass consumption, which was strongly criticized by these consumers in the context of the economic crisis when the FGs and the interviews were held. They judged this form of consumption to be degrading, consumerist, polluting and, in their opinion, lacking any legitimacy whatsoever. The legitimization process can be seen, for example, in the discursive thread about the inferiorization of “non-green” consumers. These consumers were “ignorant,” “blind,” “lazy,” “passive,” “alienated,” “lacking in culture,” and “incapable of realizing the existence of and understanding socio-environmental issues” (FG 10). This inferiorized image of “non-green others” was projected onto consumers from a working-class background, who, according to quantitative data, are the least likely to be “green” consumers (Grandin et al. Citation2022; Elliott Citation2013). This suggests an aspirational process, as we have already seen, expressed through identity signs and (partially) ascetic attitudes, which requires the mobilization of cultural and cognitive resources that make it possible to discern and classify legitimately “green” products. In consonance with Bourdieu (Citation1979), it is precisely this capacity to discriminate between products and their consumers, which is not always reflexive, that best exercises distinction through social classifications; classifications that also classify classification itself (Elliott Citation2013). According to this discourse, consumers who are “non-green” lack the necessary sensitivity, interest, and knowledge about the “goodness” of “green” consumption.

W: And that [conventional consumption] hooks people without good judgement … We’re older, we have an education, we think, but the immense mass media [sic] don't!

M: Exactly! (FG 11)

M: I’d say that we’re talking about most of the population … I’d say that it’s an overwhelming majority … And within this overwhelming majority there must be a large part that simply goes about their routine, and their routine doesn’t include ecology, because it simply doesn’t, there’s no question … simply … (FG 11)

W: I consider myself to be very much outside that tendency of consuming in a slightly uncontrolled way, so to speak. This has, on the one hand, cultural implications, and also implications of conscience and social convictions. (FG 12)

W: You generate a lot of distance …

M: Rejection …

M: Exactly. And you want to feel different, and you want to make a difference.

H: Look, last year I bought one pair of trousers, in the whole year, 5 pairs of socks, a pair of shoes every two years and stuff like that … (FG 10)

M: … more movements are emerging in the neighbourhood, it's like we're making more of a neighbourhood, right? We are becoming aware that we are citizens and that we can do things, and various initiatives are emerging to contact local people, small producers. (FG 12)

W: … a person who consumes organically and goes to Veritas [a green supermarket chain] is different from me. (FG 10)

M: So, we say one thing, but it seems that the world’s going in another direction … there’ll be a local Carrefour Market that will absorb a lot of shops (…) and normal people aren’t ready for this. (FG 12)

W: Yes, there is, I think there’s an important sector of organic consumers, people of a certain social and economic class, upper class, who are possible … fortunately, eh, and it's not a criticism, eh, but if they can afford it, it's cool, eh, to consume organically.

W: Yes, but that’s a pose …

W: Yes, it's a pose, there’s an expression in French that says “ecolochic,” because it looks chic … (FG 11)

Discourse on the rejection of green consumption

With regard to discourses emerging from sectors far removed from “green” consumption, it is not that they are necessarily less respectful of the environment, but rather that their discourse responds to a logic of practice and existential needs, which, at the time of the research, were closely linked to an economic crisis. For this reason, the discourse of middle class and working class sectors that are not “green” consumers tended to defend “negationist” or “conformist” positions in the face of the climate crisis (FGs 2, 5, 6) and focused their discourse on delegitimizing “green” consumption, either because of price, perceived as excessively high, as a “luxury good” for the rich, which makes it impossible for them to access it, or by discrediting the image of “green,” linking it to particular market interests (Alonso et al. Citation2014).

M: … what we were saying about ecology, of course, is that this plastic is going to take four hundred years to break down, or not, who knows, I mean, what are we basing it on, that there is someone who has done some carbon type tests, or whatever, I don't know, and has been able to determine that this material until this time has passed, this, well, OK, we believe it and then we enter into this ecological dynamic, but let's see … (FG 5)

M: It’s very expensive and can’t be consumed at the moment. (FG 1)

M: … as soon as companies see that there is profit there, they will throw ecology at us from all angles. (FG 7)

M: These things have to be mandatory (FG6)

M: … it’s the institutions that have to change it, because as an individual I can’t do anything (FG7)

M: It's all very well getting used to the good life, but getting used to the bad …

M: We get used to it.

M: Of course, because it's very easy to live well.

M: You get used to it out of necessity, but not because you want to (…)

M: But if you can have a twenty thousand one, why wouldn't you have one? (FG 9).

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we have explored two of the main socio-motivational types of logic that underlie the processes of “green” consumption that the literature, more focused on the model of reflexive rationality, has not sufficiently addressed. Our analysis of the emotional level of guilt has provided a new perspective on “green” consumption, emphasizing the different ways in which guilt can be expressed. The role of the socio-environmentalist super-ego is particularly relevant in this sense, as it explains, from a prism that has been little explored, the socio-motivational dynamics of “green” consumption, such as the case of the conflict between metapreferences and the unconscious feeling of guilt. The implications of these results highlight the motivational variability behind “green” consumption and extend Chatzidakis’ (Citation2015) insights, adding information about the self-punishing nature that may lie behind certain types of “green” consumption. In addition, the results provided are consistent with those studies that have analyzed strong contradictions in green consumption, to the point of defining in some cases a certain distress associated with morale and sometimes (unconscious) feelings of guilt (Bray, Johns, and Kilburn Citation2011; Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016; Sharma and Lal Citation2020). In this sense, this study reinforces the thesis that questions consumption as an “obligation to enjoy,” providing arguments about the genesis of ethic or moral responsibility pointed out by different authors (Saraiva et al. Citation2021; Connolly and Porthero Citation2008; Rief Citation2008).

On the other hand, the analysis of logic of practice shows that, at least in the Spanish context, “green” consumption is involved in socio-symbolic struggles between social groups. In these contexts, “green,” as applied to consumption, is not only used by sectors with high cultural capital to promote socio-environmental ideologies (Malier Citation2021; Horton Citation2003), but also to establish symbolic barriers against those who do not share a discourse based on environmental awareness and their corresponding consumption styles. In this area, our findings reinforce and complement other studies that has described motivational dynamics linked to “green status,” albeit in very specific social sectors (Anantharaman Citation2018; Kennedy and Given Citation2019; Griskeicius et al. Citation2010). In addition, they provide evidence to suggest the development of internal symbolic struggles in the field of “green” consumption. That is, strategies to assign meaning to and for the legitimate appropriation of the phenomenon of “green” consumption by particular social groups of the middle and upper-middle classes. This latter aspect is relevant because it has not been studied in depth in the literature.

As some scholars have pointed out, the implications of “green” consumers’ discourse stem from the individualistic approach, despite the communitarian rhetoric of cooperatives, according to which each individual must strive, in accordance with his or her moral responsibility, to orient his or her consumption goals towards sustainability (Mailer Citation2021). And this, as we have shown, is costly and sometimes difficult (Moisander Citation2007). We have seen that the feeling of (unconscious) guilt can work in favour of this approach, increasing the possibilities of “green” consumption in certain consumers, but its limitations seem clear: not everyone is willing to accept “abnegations and punishments” in an area, consumption, that tends to be experienced as free, as shown in the discourse of popular sectors and even among “green” consumers (the “trade-offs” that make “green” consumption more bearable. This aspect is consistent with the studies that associate guilt with preferences for “green” consumption (Peloza, White, and Shang Citation2013; Antonetti and Maklan Citation2014), and those indicating the absence of guilt among those less sensitive to environmental problems (Wonneberger Citation2018). However, it is worth insisting that our findings emphasize that non-conscious guilt is expressed in those discourses that show contradictory values and desires.

On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that a punitive moral orientation (of the super-ego) not only leads to significant suffering, but also prevents us from being truly critical in assessing whether or not to satisfy our desires. Because if we are driven by guilt, we do what we do out of submission to internalized rules, not out of critical judgement. In favour of this argument, some works have seriously questioned the impact of “green” consumption on the ecological footprint (Csutora Citation2012; Chen et al. Citation2016).

All this may lead to a rethinking of the idea of sustainability as a cultural value to be defended through voluntary environmental policies on “green” consumption. As Requena-i-Mora (Citation2021) suggests, if sustainability is a way of life linked to practical and existential needs, it can only be taken on by global social organization. This work shows that the moral values behind “green” consumption have their basis not in the rational or reflective sovereignty of individuals but in practical and emotional logics traversed by the hierarchical social structure. It would therefore seem naive to expect “moral responsibility” by all consumers as a way of achieving overall sustainability, while leaving the functioning of capitalism intact, if what is intended is social and environmental change (Ariztia and Araneda Citation2022; Carrington, Zwick, and Neville Citation2016). “Green” consumption, as a postmaterial moral-cultural value, is interesting fundamentally in the eyes of the most privileged, whose guilt and resources guide them to developing “green” styles of consumption. However, this is not the case with the popular social sectors, which are far removed from “green” consumption, but which in everyday practice are less responsible for environmental problems than the more privileged sectors.

These issues call for reflection on the need to incorporate issues such as symbolic and material inequalities into the analysis of “green” consumption, as well as a critical look at the relationship between this type of consumption, power and social justice. In line with this, future research should further explore sustainable consumption practices linked to needs and existential ways of life, with the aim of reconstructing a more plural, less elitist and less guilt-apportioning conception of “green” consumption (Anantharaman Citation2018).

The panorama presented by these findings raises some doubts about the possibilities of focusing effective environmental policies on this type of consumption. If, as we have seen, “green” consumption comes from differentiation based on guilt, with attitudes linked to this emotion being a symbol of “austere prestige,” it seems difficult to enlist broad layers of the population who do not share this way of thinking, these symbolic purposes, or who do not feel the obligation to respond to feelings of guilt through voluntary and “punishing” restrictions on consumption. These conclusions provide us with some of the keys as to why in markets such as the Spanish, “green” consumption and its discourses have had difficulty gaining hegemony among the general public, and particularly among sectors with lower social status. On the other hand, they inform us of the limitations of these “green” consumption discourses during the period immediately following an economic crisis such as that of 2008. This, without a doubt, opens up new questions for future research aiming to investigate the discursive evolution and transformations undergone by “green” consumption in the face of new periods of crisis such as the one that concerns us here. Will the end of the Covid-19 crisis bring with it new and deeper transformations in consumption, favouring the growth of sustainability? By means of which motivational pathways or logics might these changes occur? For the time being, some other works in line with ours indicate that consumption, including “green” consumption, is a multiplier of social differences that, being related to fields such as work, tend to be replicated symbolically and ideologically. Therefore, this phenomenon is by and large to be found in the moral and differentiating elitism of “green” consumption, at least in the Spanish market (Malier Citation2021; Anantharaman Citation2018; Kennedy and Given Citation2019). However, some other recent works have indicated that the pandemic crisis is promoting forms of survival and even resistance in some lifestyles, with a tendency towards recovering community ties and meeting spaces in common consumption, small neighbourhood stores, etc. (Alonso and Fernandez Citation2021). It remains to be seen to what extent these forms of consumption become consolidated and the place that “green” consumption occupies within them in future post-Covid-19 societies.

Finally, and in accordance with the above, the present work allows us to affirm the need to propose environmental policies that get rid of the centrality of “green” consumption, and that open opportunities for collective action favourable to new production/consumption models. If we view consumption through the anti-utopian lenses of Bourdieu, where domination and inequality will never find an end, then environmental policies highly focused on “green” consumption within the capitalist market offer little solution. Accordingly, we should perhaps modify our approach and focus on the economic structures of production and public powers. In a very general way, collective action should be guided by something similar to what Freud called the reality principle – adapting the concept to our purposes. In other words, consumption should not be based on projections of arbitrary, illusory and omnipotent desires, as consumerist ideology has traditionally done, even if this dimension of desire, which does actually exist, cannot be ignored either. This leads us to consider consumption in terms of how possible it is to express the desires of people and social groups, while in full contact with the limitations imposed by external reality. And that, in turn, means basing consumption on democratic, effective and sustainable production systems; or, put another way, that an increase in wealth does not necessarily imply a decrease in natural resources that can be depleted – indeed, models for a sustainable economy already exist: see Naredo (Citation2019). According to this proposal, the production/consumption model would therefore have to prioritize covering democratically established needs above all others.

Acknowledgment

Luis E. Alonso, Carlos J. Fernandez, Rafael Ibáñez (UAM) and Colectivo IOÉ for giving me access to your project data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marc Barbeta-Viñas

Marc Barbeta Viñas, PhD in Sociology (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2013) and specialist in qualitative research methods, sociology of consumption and culture, and experience in different fields of research (agrarian studies, education, inequalities, gender, fatherhood). Currently works as a sociology professor at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Universitat de Girona. Previously, he has been researcher in different research groups of the sociology department of the UAB. As a result of this research, he has published in national and international journals. He has also collaborated on collective books and has recently edited a book with the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC, in Spain).

Notes

1 The data extracted from the focus groups and interviews were literally transcribed to form the corpus of texts for analysis. Subsequently, the findings were translated into English by a professional translator financed by University of Girona.

References

- Alonso, Luis E. 2013. “La sociohermenéutica como programa de investigación en sociología.” Arbor 761: 1.15. doi:10.3989/arbor.2013.761n3003

- Alonso, Luis E., and Carlos J. Fernández Rodríguez. 2021. “COVID19 ‘Cambios en la sociedad de consumo española’.” In Sociología en Tiempos de Pandemia, Coords by O. Salido, and M. Massó, 237–248. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

- Alonso, Luis E., Carlos J. Fernández Rodríguez, and Rafael Ibáñez. 2014. “Crisis y nuevos patrones de consumo: discursos sociales acerca del consumo ‘verde’ en el ámbito de las grandes ciudades españolas.” EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 29: 13–38.

- Alonso, Luis E., Carlos J. Fernández Rodríguez, and Rafael Ibáñez. 2015. “From Consumerism to Guilt: Economic Crisis and Discourses About Consumption in Spain.” Journal of Consumer Culture 15 (1): 66–85. doi:10.1177/1469540513493203.

- Anantharamant, Manisha. 2018. “Critical Sustainable Consumption: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 8: 553–561. doi:10.1007/s13412-018-0487-4.

- Antonetti, Paolo, and Stan Maklan. 2014. “Exploring Postconsumption Guilt and Pride in the Context of Sustainability.” Psychology and Marketing 31: 717–735.

- Ariztia, Tomas, and Felipe Araneda. 2022. “A “Win-win Formula:” Environment and Profit in Circular Economy Narratives of Value.” Consumption Markets & Culture. doi:10.1080/10253866.2021.2019025.

- Ateeq, Abdul Rauf. 2021. “Making the Case for Reusing and Sharing Data in Qualitative Consumer Research.” Consumption Markets & Culture. doi:10.1080/10253866.2021.1987226.

- Barbeta-Viñas, Marc. 2015. “Entre renúncies, temors i deures: anàlisi de l’estructura motivacional del consum ecològic.” Papers, Revista de Sociologia 100 (1): 5–33.

- Barbeta-Viñas, Marc. 2020. “La sociohermenéutica de los tipos sociolibidinales.” Empiria, Revista de Metodología en Ciencias Sociales 45: 51–73.

- Barbeta-Viñas, Marc. 2022. “Consumo, crisis y clases medias: cambios y continuidades en los discursos sobre el consumo de la clase media española ante la Gran Recesión de 2008.” Revista Española De Sociología 31: 1. doi:10.22325/fes/res.2022.82.

- Başgöze, Pinar, and Oznur Özkan. 2012. “Ethical Perceptions and Green Buying Behavior of Consumers: A Cross-National Exploratory Study.” Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 4 (8): 477–488.

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society:Towards a New Modernity. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Bollas, Christopher. 1987. The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought. New York: Routledge.

- Boström, Magnus, Rolf Lidskog, and Ylva Uggla. 2017. “A Reflexive Look at Reflexivity in Environmental Sociology.” Environmental Sociology 3 (1): 6–16. doi:10.1080/23251042.2016.1237336.

- Boström, Magnus, Michelle Micheletti, and Peter Oosterveer. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1979. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Hardvard: Hardavrd University Press. 1984.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Standford, CA: Standford University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2000. Pascalian Meditations. Standford, CA: Standford University Press.

- Bowen, Glenn. 2006. “Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12–23. doi:10.1177/160940690600500304.

- Brand, Karl- Werner. 2010. “Social Practices and Sustainable Consumption: Benefits and Limitations of a New Theoretical Approach.” In Environmental Sociology European Perspectives and Interdisciplinary Challenges, edited by M. Gross, and H. Heinrichs, 217–235. SpringerLink.

- Bray, Jeff, Nick Johns, and David Kilburn. 2011. “An Exploratory Study Into the Factors Impeding Ethical Consumption.” Journal of Business Ethics 98 (4): 597–608.

- Caniëls, Marjolein, Wim Lambrechts, Johannes Platje, Anna Motylska-Kázma, and Bartosz Fortúnski. 2021. “’ Impressing my Friends: The Role of Social Value in Green Purchasing Attitude for Youthful Consumers’.” Journal of Cleaner Production 303: 126993. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126993.

- Carrington, Michal, Benjamin Neville, and Gregory Whitwell. 2014. “Lost in Translation: Exploring the Ethical Consumer Intention-Behavior Gap.” Journal of Business Research 67 (1): 2759–2768.

- Carrington, Michal, Detlev Zwick, and Benjamin Neville. 2016. “The Ideology of the Ethical Consumption gap.” Marketing Theory 16 (1): 21–38.

- Chatzidakis, Andreas. 2015. “Guilt and Ethical Choice in Consumption: A Psychoanalytic Perspective.” Marketing Theory 15 (1): 1–15.

- Chatzidakis, Andreas, Deidre Shaw, and Matthew Allen. 2021. “A Psycho-Social Approach to Consumer Ethics.” Journal of Consumer Culture 21 (2): 123–145. doi:10.1177/1469540518773815.

- Chen, Xiaodong, Jeniffer de la Rosa, Nils Peterson, Ying Zhong, and Chuntian Lu. 2016. “Sympathy for the Environment Predicts Green Consumerism but not More Important Environment Behaviours Related to Domestic Energy Use.” Environmental Conservation 4 (2): 140–147.

- Colectivo IOE. 2013. La demanda de comercio justo en España. Frenos y palancas para su desarrollo. Inedit.

- Conde, Fernando. 2009. Análisis Sociológico del Sistema de Discursos. Madrid: CIS.

- Connolly, John, and Andrea Porthero. 2003. “Sustainable Consumption: Consumption, Consumers and the Commodity Discourse.” Consumption Markets and Culture 6 (4): 275–291. doi:10.1080/1025386032000168311.

- Connolly, John, and Andrea Porthero. 2008. “Green Consumption Life-Politics, Risk and Contradictions.” Journal of Consumer Culture 8 (1): 117–145. 1469-5405. doi:10.1177/1469540507086422.

- Cremin, Ciara. 2012. “The Social Logic of Late Capitalism: Guilt Fetishism and the Culture of Crisis Industry.” Cultural Sociology 6 (1): 45–60.

- Csutora, Maria. 2012. “One More Awareness Gap? The Behaviour-Impact Gap Problem.” Journal of Consumer Policy 35: 145–163.

- Beserra de Lima, Elton, Cristiane Ribeiro, and Georgia Rocha. 2019. “Guilt and Pride Emotions and Their Influence on the Intention of Purchasing Green Products.” Consumer Behavior Review 3 (2): 70–84.

- Dedeoglu, Ayla, and Ipec Kazançoğlu. 2010. “The Feelings of Consumer Guilt: A Phenomenological Exploration.” Journal of Business Economics and Management 11 (3): 462–482. doi:10.3846/jbem.2010.23.

- Denegri-Knott, Janice, Elizabeth Nixon, and Kathryn Abraham. 2018. “Politicising the Study of Sustainable Living Practices.” Consumption Markets & Culture 21 (6): 554–573. doi:10.1080/10253866.2017.1414048.

- Eckhardt, Giana, and Fleura Bardhi. 2020. “New Dynamics of Social Status and Distinction.” Marketing Theory 20 (1): 85–102.

- Elliott, Rebecca. 2013. “The Taste for Green: The Possibilitiesand Dynamics of Status Differentiation Through ‘Green’Consumption.” Poetics 41 (3): 294–322.

- Fontanelle, Isleide. 2013. “From Politicisation to Redemption Through Consumption: The Environmental Crisis and the Generation of Guilt in the Responsible Consumer as Constructed by the Business Media.” Ephemera 13 (2): 339–366.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1929. Civilization and Its Discontents. New York: Norton.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1933. New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. New York: Norton.

- Fuentes, Christian, and Niklas Sörum. 2019. “Agencing Ethical Consumers: Smartphone Apps and the Socio-Material Reconfiguration of Everyday Life.” Consumption Markets & Culture 22 (2): 131–156. doi:10.1080/10253866.2018.1456428.

- Giddens, Anthonny. 1991. Modernity and Self-identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Grandin, Aurore, Leonart Guillou, Rita Sater, Martial Foucault, and Colarie Chevallier. 2022. “Socioeconomic Status, Time Preferences and pro-Environmentalism.” Journal of Environmental Psychology. PsyArXiv.

- Gregory-Smith, Diana, Andrew Smith, and Heidi Winklhofer. 2013. “Emotions and Dissonance in ‘Ethical’ Consumption Choices.” Jo. Mark.Management 29 (11-12): 1201–1223.

- Griskevicius, Vradas, Joshua Tybur, and BramVan Den Bergh. 2010. “Going Green to Be Seen: Status, Reputation, and Conspicuous Conservation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (3): 392–404.

- Haynes, Paul, and Stephan Podobsky. 2016. “Guilt-free Food Consumption: One of Your Five Ideologies a day.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 33 (3): 202–212.

- Hirschman, Albert O. 1982. Shifting Involvements: Private Interest and Public Action. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press.

- Horton, Dave. 2003. “Green Distinctions: The Performance of Identity among Environmental Activist’.” The Sociological Review 51 (2): 63–77.

- Hughes, Kahryn, and Anna Tarrant. 2019. Qualitative Secondary Analysis. London: Sage.

- Ibáñez, Jesús. 1979. Más allá del grupo de la sociología. El grupo de discusión: técnica y crítica. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Kennedy, Emmily, and Jennifer Givens. 2019. “Eco-habitus or Eco-powerlessness? Examining Environmental Concern Across Social Class.” Sociological Perspectives 62 (5): 646–667.

- Krueger, Richard, and Anne Casey. 2015. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Laidley, Thomas. 2013. “Climate, Class and Culture: Political Issues as Cultural Signifiers in the US.” Sociological Review 61: 153–171.

- Lorenzen, Janet. 2014. “Green Consumption and Social Change: Debates Over Responsibility, Private Action, and Access.” Sociology Compass 8/8: 1063–1081.

- Malier, Hadrien. 2021. “No (Sociological) Excuses for not Going Green: How do Environmental Activists Make Sense of Social Inequalities and Relate to the Working Class?” European Journal of Social Theory 24 (3): 411–430. doi:10.1177/1368431021996611.

- Mapama. 2017. Caracterización de compradores de productos ecológicos en canal especializado. Madrid: Centro de Publicaciones Administración general del Estado.

- Moisander, Johanna. 2007. “Motivational Complexity of Green Consumerism.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 31: 404–409.

- Morgan, David. 1993. Succesful Focus Groups:Advancing Iusses the State of the art. NewburyPark: Sage.

- Moser, Andrea. 2016. “Consumers’ Purchasing Decisions Regarding Environmentally Friendly Products: An Empirical Analysis of German Consumers.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 31 (c): 389–397.

- Naredo, José Manuel. 2019. Taxonomía del lucro. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Newman, Kevin, and Rebecca Trump. 2017. “When are Consumers Motivated to Connect with Ethical Brands?” The Roles of Guilt and Moral Identity Importance.” Psychology & Marketing 34 (6): 597–609. doi:10.1002/mar.21008.

- Peattie, Ken. 2010. “Green Consumption: Behaviour and Norm.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 35: 195–228.

- Peloza, John, Katherine White, and Jingzhi Shang. 2013. “Good and Guilt-Free: The Role of Self-Accountability in Influencing Preferences for Products with Ethical Attributes.” Journal of Marketing 77 (1): 104–119.

- Perera, Chamilla, Pat Auger, and Jill Klein. 2018. “Green Consumption Practices Among Young Environmentalists: A Practice Theory Perspective.” Journal of Business Ethics 152 (2): 843–864. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3376-3.

- Requena-i-Mora, Marina. 2021. “Del fetichismo de la conciencia medioambiental al habitus y las lógicas prácticas: el ecologismo de los pueblos.” In Siempre nos quedará Bourdieu, edited by L. E. Alonso, 229–266. Madrid: Circulo Bellas Artes.

- Rief, Silvia. 2008. “Outlines of a Critical Sociology of Consumption: Beyon Moralism and Celebration.” Sociology Compass 2 (2): 560–576.

- Ruiz, Jorge. 2018. “Collective Production of Discourse: An Approach Based on the Qualitative School of Madrid.” In A New Era of Focus Group Research. Challenges, Innovation and Practices, edited by R. Barbour, and D. Morgan, 277–300. Portland, OR: Portland State University.

- Saraiva, Artur, Emília Fernandes, and Moritz Schwedler. 2021. “The pro-Environmental Consumer Discourse: A Political Perspective on Organic Food Consumption.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (2): 188–204.