ABSTRACT

Is there one legitimate form of luxury, or are there many acceptable luxury forms? The answer is that it all depends on the perspective used to define luxury, and who is involved in doing so. Luxury research is a solid field of study. However, most studies in marketing and consumer research focus on the exclusive nature of luxury consumption and mainly adopt a goods-centric and conventional approach. Doing so does not allow scholars to capture the holistic aspects of luxury perceptions and consumption. To address this issue, this review article draws on recent developments calling for more approaches beyond the conventional conceptualization of luxury and advancing our understanding of it. This can be achieved by offering a comprehensive and multilayered framework to define luxury, which is viewed through various theoretical lenses, units of analysis, and the stakeholders involved in luxury domains.

Luxury is not the opposite of poverty but that of vulgarity – Gabriel (Coco) Chanel

My greatest luxury is not having to justify myself to anyone. Luxury is the freedom of mind, independence, in short, the politically incorrect – Karl Lagerfeld

Introduction

The luxury market has shown significant growth. Leading luxury brands are more profitable than ever and attracting new segments of consumers globally (Ko, Costello, and Taylor Citation2019). When it comes to academic interest, luxury has shifted from an emerging research topic to an established field explored by scholars across various disciplines. However, even though the luxury field is well-researched, most studies have mainly defined luxury by focusing on consumers’ social statuses (Han, Nunes, and Dreze Citation2010) and their attitudes towards luxury brands (e.g. Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004). , In addition, questioning the meaning of luxury from a more comprehensive and holistic perspective of what luxury is and what it is not has often been neglected.

Furthermore, the analysis of existing studies shows that what is considered to be a luxury is highly debatable. The search continues for a consensus and established definition of luxury in marketing and across disciplines. Considering economics, luxury has been defined in relation to pricing theories (Huang et al. Citation2017) based on the logic of higher prices of goods (products and services). This conventional definition draws on the principle of price elasticity and demand (Fibich, Gavious, and Lowengart Citation2005). It defines luxury by segmenting the market into three main categories of goods – inferior goods, goods of necessity, and luxury goods – so as to distinguish luxury from nonluxury items. This categorization, although practical and easy to apply, has been criticized due to its reductive nature and the fact that it ignores the intangible, emotional, historical, and symbolic aspects, which lie at the heart of luxury consumption.

Likewise, most existing marketing and consumer research studies disregard the idea of a holistic luxury, which might uncover many types of luxuries. Consequently, the concept of luxury has become more confusing due to the increased accessibility to luxury goods that create alternative categories such as “premium,” “high-end,” and “limited editions.” The lack of research that questions the meanings of luxury and identifies its major theoretical frameworks is problematic.

This review piece offers a comprehensive framework for defining luxury by discussing the perspectives introduced in the articles published in the special issue “Luxury or luxuries? Integration of cross-disciplinary frameworks and theories for a holistic conceptualization of luxury” (which appeared in the journal of Consumption Markets and Culture). The authors of these articles, namely von Pezold and Tse (Citation2022), Ho and Wong (Citation2022), and Iqani (Citation2022), respond to the call for further research examining luxury from a critical and holistic perspective. Thus, the special issue integrates different frameworks, theories, and methodologies to explore luxury meanings from a holistic standpoint. The aim is to advance luxury research by moving its conceptualization beyond the conventional economic logic that defines it as expensive, rare, and exclusive (e.g. Wang Citation2022).

The articles published in the special issue invite marketing scholars to review the current static and one-sided definition of luxury by embracing a holistic understanding. In marketing, most authors have adopted a goods-centric approach to luxury by identifying its categories based on different criteria. For instance, Bearden and Etzel (Citation1982) define luxury in terms of consumption spheres classified into public goods, private assets, luxury consumed in public spaces, and private luxury. For Dubois and Duquesne (Citation1993), luxury is related to product prices classified into accessible and cheap luxury versus exceptional luxury. Research criticizing luxury’s materialistic and discriminating nature has also been conducted (e.g. Hemetsberger Citation2018). A service research perspective on luxury defines the concept as a set of extraordinary hedonic and exclusive experiences (Wirtz, Holmqvist, and Fritze Citation2020). This definition underlines the intangible aspect of luxury, where its meaning is captured from the consumer’s subjective perception. Thus, identifying both tangible and intangible dimensions as well as personal and sociocultural aspects of luxury is needed to better understand how consumers define luxury and their motivations to purchase luxury goods.

The current special issue addresses this need by advancing the theoretical and empirical understanding of the construct of luxury. The three articles published in the special issue show that the meaning of luxury is embedded within a particular setting and is shaped by many factors that can affect its definition. Therefore, the perspectives followed by the authors in these articles highlight three key factors – people’s genders and maturity, time and space, and reflexivity – affecting and shaping the definition of luxury. Considering how gender and the temporal-spatial factor affect the meanings of luxury, the article by von Pezold and Tse (Citation2022) uses an anthropological perspective to examine luxury consumers’ intimate relationships with their wardrobes. The authors draw on critical luxury studies (Armitage and Roberts Citation2016) to explore an understudied group of luxury consumers: non-Western homosexual men and their perceptions of the luxury items in their wardrobes. The study results show that the inconspicuous luxury defined in Western studies is not a universal concept but culturally composite, idiosyncratic, and diverse.

Since prior studies that examined the relationships Asian consumers have towards their statuses and conspicuous consumption (e.g. Podoshen, Li, and Zhang Citation2011) have often been stereotypical and one-sided, von Pezold and Tse’s research (Citation2022) advances the field of studies on male homosexual consumers (e.g. Visconti Citation2008). The research does so by considering a spatial-temporal perspective through a qualitative investigation conducted in a post-colonial Asian context: Hong Kong. This research contributes to prior works by redefining luxury from an anthropological approach where luxury is understood from a subjective and personal standpoint embedded within the context in which luxury is consumed. Thus, von Pezold and Tse’s (Citation2022) research advances the current marketing and consumer research studies by integrating a more inclusive view of luxury (i.e. different ages, genders, and ethnicities of people) in less Western-centric settings.

In the same vein, the article by Ho and Wong (Citation2022) conceptualizes luxury in relation to its inconspicuous meaning by focusing on the consumer’s maturity. Ho and Wong (Citation2022) define luxury as an evolving process allowing consumers to acquire knowledge from past experiences. The outcome of the process is that consumers gain maturity, which leads to changes in their tastes, from conspicuous to inconspicuous luxury perceptions and consumption. The authors contribute to the existing definitions of luxury, whereby people’s economic and social statuses lie at the heart of luxury definition (Han, Nunes, and Dreze Citation2010), by proposing the theory of luxury consumer maturity. The theory refers to inconspicuous luxury as part of Bourdieusian cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1984) to explain how consumers’ tastes can evolve over time. By proposing the mechanisms that facilitate the maturity development of consumers, including their knowledge, saturation, and time, Ho and Wong (Citation2022) contribute to the current literature on the relationship between luxury and taste formation and evolution (Valsesia, Proserpio, and Nunes Citation2020) by identifying the process by which luxury consumers mature, which results in their preferring inconspicuous luxury items instead of conspicuous luxury items.

Going beyond a consumer-centric definition of luxury, the article by Iqani (Citation2022) considers a relevant and unusual angle to define luxury from a self-reflexive standpoint: the researcher’s view. The article proposes a conceptualization of luxury from the reflexive perspective of a researcher (the author Iqani) acting as an outsider observing and reflecting on luxury. The study draws on Stuart Hall’s classic decoding model (Hall Citation2004) to explore luxury perceptions and acquisition modes. The research advances current studies by underscoring the importance of adopting reflexivity when it comes to luxury research – that is, research that calls into question the authority of both the researcher/actor and the ontology of luxury itself. Future research should then approach luxury as a discursive construction where its meaning is celebrated, negotiated, or opposed.

Therefore, a new conceptualization of luxury is needed to respond to consumers’ emerging needs and the changing context due to the rise of environmental and social issues, digital transformation, and global health and economic crises. By synthesizing the abovementioned discussions, I propose the following definition of luxury as an evolving and multidimensional construct. It encompasses several meanings individuals assign to it according to the norms and codes of their consumption cultures. These meanings evolve with time as well as with social and individual changes. Luxury is also closely tied to the culture and practices of the group in which it emerges, shapes, and develops. Therefore, luxury is in all of us. It is produced by and for individuals, professionals, and institutions, as well as political and social actors. What is luxury for some is, therefore, mundane for others. This definition underlines the importance that the meaning of luxury depends on the chosen perspective that must be identified beforehand. Certainly, luxury is a multifaceted concept that cannot be comprehended from a single, one-sided perspective that does not integrate its various layers. Thus, an integrative framework is needed to allow scholars to better understand the different perspectives on luxury. The next section introduces a comprehensive framework for defining luxury.

A comprehensive framework for defining luxury

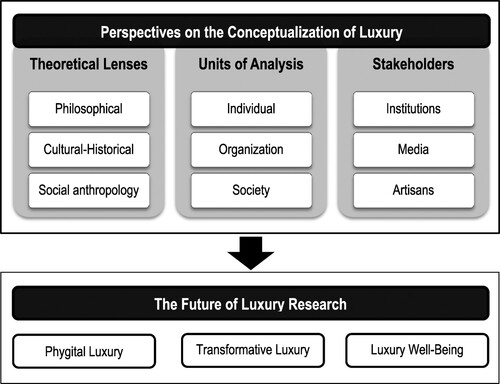

The abovementioned articles published in the special issue have responded to the recent calls in marketing for critical approaches to luxury (Armitage and Roberts Citation2016) and more studies exploring new types of unconventional luxury (Thomsen et al. Citation2020). In this section, I introduce a comprehensive framework scholars can adopt to define the construct of luxury. The framework shown in offers an in-depth understanding of the perspectives both scholars and professionals can embrace to examine luxury consumption. The all-inclusive and multilevel framework proposed in this article encompasses several theoretical lenses, units of analysis, and stakeholders that can affect and reshape the meanings of luxury.

Defining luxury from multiple theoretical lenses

Luxury is a cross-disciplinary research area covering different theoretical fields, such as sociology, anthropology, philosophy, economics, cultural studies, and business, among others. Although numerous disciplines have defined luxury, undeniably, the dominant literature in marketing and consumer behavior studies refers to a conventional view of luxury as a functional utility (Han, Nunes, and Dreze Citation2010). Such a view fails to capture the intangible, subjective, and changing aspects of luxury. Thus, considering luxury from a holistic perspective is critical for researchers trying to understand the paradoxes and the cultural complexity of luxury consumption and consumers’ heterogeneous behaviors and perceptions. This view calls for a more experiential, holistic, and multidisciplinary examination of luxury in marketing and consumer research. Following this logic, I propose a multidisciplinary approach to luxury, which includes three core theoretical lenses for conceptualizing luxury: philosophical theories, cultural-historical theories, and social anthropology theories.

Philosophical theories on luxury discuss two aspects related to its conceptualization in the field: aesthetic possession and exclusivity. According to Wiesing and Roth (Citation2019), luxury is an aesthetic experience individuals pursue by possessing physical objects. Likewise, aesthetic luxury depends on the perceptions of individuals, who, through their experiences, develop the ability to make judgments about the value and quality of their purchases and thus distinguish between what is luxury and what is not (White Citation1970). This statement aligns with Gardner’s (Citation1993) concept of aesthetic intelligence, which emerges from different lived experiences. Accordingly, luxury as an aesthetic experience is an evolving concept that should be viewed as an ongoing process instead of a static object defined by its tangible features (Atwood Citation2004). In this sense, aesthetic luxury requires distinguishing between two segments of people: unacquainted and erudite individuals. Moreover, defining luxury as exclusive refers to its discriminating aspect. Several philosophers have questioned if luxury is a human need (Mendonça Citation2020) and whether the exclusive aspect of luxury goods is still valid, especially in today’s globalized consumer societies in which luxury becomes easily accessible online, marking the era of the decline in the exclusivity and uniqueness of luxury (Turunen Citation2018).

Cultural-historical theories on luxury highlight the evolution of the definition of luxury, which, in turn, is shaped by different periods, cultures, and emerging social classes. This perspective questions if luxury has a culture and a history that can explain consumers’ attitudes by virtue of the products they consume. Indeed, cultural diversity due to globalization and the democratization of people’s access to luxury, particularly in developing countries and among the newly rich, have contributed to the rise of different attitudes towards luxury. Therefore, the cultural-historical perspective shows that the definition of luxury has evolved throughout time, ranging from medieval luxury to modern and marketing luxury era. Medieval luxury, which can be traced back to the Middle Ages, is defined in terms of the aesthetics of tangible objects – objects charged with cultural symbols and used for two purposes: power and seduction (Batat and De Kerviler Citation2020). Modern luxury refers to royalty and the newly emerging bourgeoisie, which emphasizes luxury’s intellectual and elite aspects. In this case, luxury goes beyond the aesthetics of objects; it is more about one’s arts and intellect (e.g. opera), along with pleasures (e.g. the pleasure of haute cuisine). The modern luxury era is also characterized by the development of royal factories and the creation of norms for quality control to distinguish luxury from nonluxury. The last era, marketing luxury, refers to mercantile luxury shaped by marketing and branding strategies and the rise of high-tech devices (e.g. Apple products) that are viewed as luxury goods. In the marketing era, luxury is fragmented (Batat Citation2019). It includes different profiles of consumers: the elite, bourgeoisie, nouveau rich, middle class, and consumers from developing countries (e.g. Asia and the Middle East) who can access it but have different expectations and perceptions of what luxury is.

Therefore, the definition of luxury is primarily cultural. Different cultures have different narratives and traditions that define the meaning of luxury. For instance, the French definition of luxury is not similar to North American luxury and is also very different compared to Chinese, Russian, or Arab luxury.Indeed, the meaning of French luxury is shaped by the habits of aristocracy and high society. In this sense, luxury, defined from a French standpoint, is not only the symbol of social status and power but also of sophistication, small details, and the love of what is “inherited,” along with an ancestral “savoir-faire” that makes the prestige of the “maison,” which is family-owned and combines tradition, craftsmanship, and elegance. Hence, the history of luxury, from its rise to its present state, shows that luxury meaning is not static. Instead, it has evolved throughout history and across cultures.

In Social anthropology theories, most existing works have focused on the motivation of individuals’ purchasing luxury goods and the meanings they assign to their luxury consumption. Sociology, for instance, defines luxury goods as a set of expensive products aimed at social elites (Schrage Citation2012). This definition has some limitations. For example, other classes of people can also use luxury goods to achieve their social goals in terms of societal elevation, recognition, distinction, identity building, socialization, or belongingness. Moreover, sociologists have examined luxury in relation to “taste,” a concept referring to luxury goods as products of refinement that other people aspire to have. Social anthropologist scholars who examined luxury refer to two major theories: (1) the theory of the leisure class, introduced by the anthropologist Veblen (Citation[1899] 2005); and (2) the distinction theory, developed by the sociologist Bourdieu (Citation1984). The works of Bourdieu and Veblen explain what motivates people to buy and consume luxury items. While defining luxury from a leisure-class theory approach refers to the conspicuous aspect of luxury consumption (Mason Citation1984), stating that the motivation of people to display and preserve their social status, as per the Bourdieusian perspective, is distinctive. Consuming luxury allows individuals to distinguish themselves from the mass trends in society.

In distinctive luxury, consumers seek exclusive and meaningful experiences that encompass hedonism and elitism to develop their knowledge and thus better appreciate luxury experiences. This kind of distinctive luxury can be found in luxury dining experiences as well, such as in Michelin-starred restaurants. Also, distinctive luxury is embraced by consumers, mainly people in the upper classes, to construct distinct identities of their own by referring to the symbolic dimension of luxury. In contrast, conspicuous luxury highlights the importance of the visibility of luxury, whereby consumers show their power by displaying well-known luxury brand logos (e.g. Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Ferrari) and ostentatious luxury items (i.e. noticeable gold and diamond accessories) to communicate their social statuses to other actors who can decode the signals displayed.

Consequently, while conspicuous luxury is about recognizable luxury brands and prominence, distinctive luxury focuses on meanings shaped by different luxury cultures. For instance, the meanings conveyed by brands, such as Chanel and Saint Laurent, belong to two different luxury cultures and thus communicate distinct meanings: Chanel cultural codes connect with female customers by celebrating femininity: The classic Chanel suit with a jacket and straight skirt emphasizes elegance, sophistication, and seduction. On the other hand, Saint Laurent’s cultural meanings are related to female empowerment by promoting masculinity. Moreover, Saint Laurent was the first to introduce a tuxedo for women, thus portraying women as powerful, independent, inaccessible, and in competition with men. However, although the two theories approach luxury from different angles – conspicuous luxury for Veblen versus distinctive luxury for Bourdieu – they are not opposed to one another. Rather, they are complementary.

Defining luxury by considering different units of analysis

The conceptualization of luxury depends on the unit of analysis, which may differ from one study to another. Analyzing the literature, I identified three major units – individual, organizational, and societal – scholars can adopt to examine luxury.

The individual unit of analysis includes a set of studies that examined luxury from a subjectivist perspective, mainly based on the idea that luxury is not about goods but more about luxury perceptions approached from the consumer’s perspective (Berger and Ward Citation2010). In this case, luxury can be defined as a mundane consumption process that does not reflect the conventional definition, usually associated with craftsmanship, premium prices, and/or exclusivity. When focusing on how consumers define luxury, especially in times like the post-pandemic era, luxury takes on new meanings. For example, it can be linked to the rare moments people spend with their families. As a result, mundane items and experiences become luxurious only when individuals can, at the end of the day, do without the items. Thus, luxury lies within everyone at every single moment; it all depends on how an individual perceives and defines luxury.

Drawing on a consumer-centric perspective, the meaning of luxury depends on how different groups of consumers perceive it (Wiedmann, Hennigs, and Siebels Citation2009) and how luxury items can be considered a source of meaning in consumers’ lives (Fournier Citation1998). This perspective shows that the meaning of luxury is constructed by the experiences consumers have – experiences whereby luxury goods are not considered for their material aspects but more in relation to their experiential dimensions (e.g. Roper et al. Citation2013), which are expressed differently depending on an individual consumer’s profile and knowledge. On the one hand, the definition of luxury, in this case, is related to consumers’ profiles and attitudes towards luxury. On the other hand, recent studies have highlighted the importance of examining luxury from an individual’s personal and social experience (e.g. Wirtz, Holmqvist, and Fritze Citation2020). These works have marked the entry of an era whereby consumers are more self-centered and focused on their emotional states when they are in contact with luxury brands. This logic shifts the luxury definition from distinctive or conspicuous to luxury as a meaningful experience in which the consumer’s feelings and emotions lie at the heart of the purchasing and consumption process.

Furthermore, consumers are no longer interested in seeking to only distinguish themselves and stand out from the masses; they also expect luxury brands to be inspiring and allow them to live unforgettable experiences. Drawing on consumer subjectivity, luxury is then viewed as an enchanting experience that goes beyond its tangible features (e.g. craftsmanship) by focusing more on its intangible elements, including symbolism (Wang Citation2022), emotions (Schmitt, Brakus, and Zarantonello Citation2015), and hedonism (Hagtvedt and Patrick Citation2009), among others. Therefore, an individual and subjective view of luxury should integrate the experiential perspective, along with consumers’ profiles and their levels of knowledge, to define luxury. However, although the subjective approach is recommended, examining luxury from an experiential perspective is difficult to implement due to the abstract aspect of the concept of experience combined with the multiple definitions of luxury in the literature.

Adopting an organizational level as a unit of analysis highlights the idea that the meanings of luxury are generated within organizations operating in the luxury sector. Luxury groups and industries believe that the definition of luxury should keep its specificity vague and imprecise. In this sense, the meanings of luxury are shaped by marketing, advertising, and merchandising techniques that deal with the design and branding of what luxury should reflect based on targets and markets. For instance, luxury leaders such as the groups LVMH, Richemont, and Kering encourage the definitional blur because it allows them to offer various products and brands that might not include luxury craftsmanship and exclusivity under the category of luxury. As a result, advertising and merchandising are used to elevate mundane consumption items (e.g. sneakers and t-shirts), usually targeting the mass market so as to convince consumers to pay premium prices because the products are branded as a luxury.

Providing an organizational definition means that luxury is apprehended from the perspective of the firm’s vision and culture. For example, the French group LVMH, a leading luxury conglomerate, defines luxury, not in terms of demand and social trends but more in relation to the group’s strategy and its impact on communities. For LVMH, luxury is about growing its portfolio of what could be acquired to extend its offers by integrating leading brands across different sectors – from fashion and leather goods to cosmetics and luxury hospitality. The growth strategy and the impactful actions of the French group show that LVMH is moving towards a definition of luxury that is more about services, as evidenced by its interest in luxury hospitality and its acquisition of various luxury hotels, such as Cheval Blanc, a high-end French ski resort (Forbes Citation2018). Also, the strategic vision of LVMH shows that luxury should also be defined by its diversification, along with the integration of minorities’ voices through collaborations, such as one in which LVMH collaborated with the singer Rihanna to create Fenty Beauty, an inclusive cosmetics brand aimed at groups of customers with different ethnicities.

Moreover, the organizational definition of luxury does not only focus on the strategic vision and the social impact; it also involves the role of luxury in promoting arts and curating exhibitions and cultural programs (Wierzba Citation2015). It is a way to inject “intellectual thickness” into luxury goods, especially because of the diversification strategy that includes the manufacturing and commercialization of mass-market products (e.g. sneakers), which are more accessible to consumers and more profitable for luxury groups. Therefore, an organizational definition highlights the struggle of luxury companies to maintain the balance between three aspects: (1) a global leadership positioning and profitable business; (2) a social role with positive impacts on communities; and (3) the preservation and the promotion of the cultural and artistic heritage that makes a good or service luxurious.

Lastly, society level as a unit of analysis refers to a definition of luxury rooted in a sociocultural setting in which the codes and norms of a specific consumption culture shape its meaning. Researchers may, therefore, consider the framework of the consumer culture theory (CCT) introduced by Arnould and Thompson (Citation2005) to examine luxury. The CCT framework invites researchers to focus more on the meanings of consumption and marketplace dynamics by examining the social and cultural representations, along with the significance consumers assign to their consumption practices and experiences. The central idea of the framework is that consumption is not merely a mercantile phenomenon but a culture with its own myths, rites, and stories. In other words, individuals can use luxury for the identity capital it provides them. More broadly, luxury goods serve as a vehicle to communicate signs and symbols among social actors.

Yet although much of the literature in marketing has examined consumers’ attitudes towards luxury, its significance and the way it has evolved over the years have received significantly less attention. For instance, in marketing research, the meaning of luxury is usually associated with status (Han, Nunes, and Dreze Citation2010), conspicuous and inconspicuous consumption (Wu et al. Citation2017), and materialism (Podoshen, Li, and Zhang Citation2011). This assumes that luxury originates its meaning principally from a conventional standpoint that defines luxury according to economic and social benefits (Hemetsberger Citation2018). Likewise, most works in marketing have defined luxury based on an economic logic of higher prices than nonluxury products (e.g. Hemetsberger Citation2018; Huang et al. Citation2017). Doing so results in a narrow view of luxury that does not consider its evolving aspects while ignoring its symbolic, emotional, and ideological values (Roper et al. Citation2013; Wang Citation2022).

Furthermore, the traditional view of luxury, widespread in marketing and consumer research, does not allow scholars to embed luxury meanings in a changing context. For example, luxury consumption practices have shifted due to new emerging markets (e.g. the Middle East, India, and Asia), the rise of social and environmental movements (e.g. the anti-fur movement), the advent of a new postmodern consumer displaying paradoxical behaviors (Batat Citation2019), and the digital revolution (e.g. e-commerce websites, social media). All of these changes have affected the sense of luxury exclusiveness.

Therefore, defining luxury from a conventional perspective based on economic and social values is insufficient to develop a comprehensive understanding of the concept. That is why embracing a consumer culture framework to understand luxury is critical. Indeed, defining luxury from a consumer culture perspective highlights the idea of consumers as cultural producers (Allen, Fournier, and Miller Citation2008) capable of creating, shaping, and reshaping the meanings of luxury that should be culturally shared among consumers (Thompson and Haytko Citation1997). These consumers may have different profiles yet belong to similar consumption cultures. Therefore, considering society as a unit of analysis allows scholars to develop a deep understanding of luxury by defining it as a social co-construction (Palmer and Ponsonby Citation2002) embedded in a given cultural context in which its meaning is affected, shaped, and reshaped by consumers who belong to a uniform consumption culture. This means that the definition of luxury is negotiated by consumers at a sociocultural level and can differ from one consumption culture to another.

Defining luxury from a stakeholder standpoint

Luxury incorporates the perceptions of multiple market actors involved in the luxury industry and who can affect its definition. Thus, developing an in-depth understanding of luxury should assess the various considerations of multiple stakeholder groups involved in its conceptualization. A stakeholder approach (Freeman, Dmytriyev, and Phillips Citation2021) to luxury refers to any groups or individuals who can affect or be affected by a luxury business’s strategy. A stakeholder approach is critical to identifying luxury actors who play an essential role in shaping a luxury’s present and future, depending on their profiles. These actors include institutions, policymakers, consumers, and business actors.

Luxury stakeholders naturally have sector-specific goals and differ from one cultural context to another, depending on the history and the institutionalization of luxury in each local ecosystem. For instance, luxury stakeholders shaping the luxury market in France (e.g. Comité Colbert) are different from those in Italy (e.g. Fondazione Altagamma). Thus, recognizing the roles stakeholders play in a globalized luxury market provides researchers with a more comprehensive view of what luxury is. Analyzing the literature on the topic, I identified three major luxury stakeholders – institutions, the media, and artisans – each of whom is shaping the meanings of luxury. Although these stakeholders play a critical role in defining what luxury is and what it is not, their engagements are outlined by the cultural settings and histories of luxury in each country.

Institutions as major stakeholders include governments, policymakers, and lobbyists, among others. Institutions are crucial actors in the luxury industry, especially in a country known for its leadership in a specific industry, such as haute couture and haute gastronomy in France or luxury watchmaking in Switzerland. Indeed, luxury cannot be understood without considering the country in which it is rooted and where its meaning is shaped by the institutions and local regulations. These institutions define luxury according to economic, political, and social criteria. In France, the luxury sector has been strictly regulated since the rise of luxury under the reigns of royalties. During the reign of Louis XIV, the King’s minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, formed the first committee to regulate the quality control of products that were considered to be luxuries (e.g. silk, perfume, gloves, and food). The effort promoted an elite and high-end approach to shaping luxury so as to distinguish exquisite craftsmanship from ordinary craftsmanship across different industries (Batat and De Kerviler Citation2020). The committee’s regulations have also made France the center of the European and international luxury industry. In 1954, the Comité Colbert, an association that today consists of 92 luxury houses, along with 17 major French cultural institutions (comitecolbert.com Citation2022), was formed. To become a member, applicants must embrace the values of the committee, be embedded in the French culture, and be internationally renowned for their excellence in the field of luxury. The Colbert committee defines luxury as a field encompassing various facets of the French highbrow culture, which should be preserved and transmitted to the next generations (comitecolbert.com Citation2022).

Another example of the institutionalization of luxury is Italy’s Foundation Altagamma or Fondazione Altagamma, which was created in 1992. The foundation is a trade association of Italian luxury goods producers. Foundation Altagamma’s mission is more focused on business. The group’s main work consists of identifying and gathering high-end Italian cultural and creative manufacturers who are globally recognized for their artisanal knowhow and are considered to be legitimate promotors of the Italian style (Foundation Altagamma Citation2022). The foundation includes over 100 members and covers many sectors, such as furniture design, hospitality, fashion, and the automotive sector, among others. The foundation empowers its members and defends the interests of Italian luxury makers by raising awareness about the market. The foundation also provides guidance and knowledge about the state of the market and new trends, along with insights about the future of design to enhance the competitiveness of Italy’s luxury industries and thus contribute to their economic growth.

The media, as a stakeholder, is involved in the luxury market as well. The media plays a key role, especially in luxury fashion. For instance, online and print magazines define luxury as a dream created by several elements of the luxury world, such as the atmosphere, materials, architecture, products, attitudes, and employees’ elegance. The media actors’ definition of luxury goes beyond the commercial aspect by underscoring in their writings, online and offline, the existence of a universe of desire, pleasure, and elegance. From a media perspective, luxury can also be referred to as refinement, dreams, preciousness, and celebrity – aspects that are part of extraordinary moments and things that individuals can engage in to please, seduce a person and have fun.

Additionally, in media and magazines that focus on high-end fashion, luxury is defined as a form of emancipation – that is, as the ability to choose and enjoy one’s choices. Luxury is also defined by the features of products promoted via stories online and in print. The media portrayed luxury in the 1980s and 1990s through its tangible and possession aspects. Today, however, most media actors have shifted their discourse from quality, lavishness, and exclusiveness towards a more emotional, sober, and engaged content to adapt to social trends and consumer movements, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic. For instance, in the post-pandemic era, Vogue, an influential luxury fashion magazine, has evolved its definition of luxury from product-centric to consumer-centric. In a context influenced by environmental and social issues, defining luxury in terms of opulence is no longer as relevant as in a time where people are seeking meaning. They expect luxury brands to play a social role beyond merely selling rare products. Moreover, the media should become social actors in improving communities’ well-being while embracing sustainable business models. Thus, for Vogue, luxury should be about approachability, democratization, and accessibility (Raniwala Citation2021). Also, the media discourse emphasizes the importance of luxury businesses embracing emotional connections and digital well-being.

For example, to help consumers improve their digital well-being, some luxury brands (e.g. Bottega Veneta) recently decided to log off of Instagram. Moreover, most media content today refers to luxury as culture (Vogue Citation2021). This shift shows that luxury is no longer related to the prestige of a brand but is more considered in terms of the ability of luxury brands to create and share cultural values with their customers through expanding their curated offerings, endorsing young creative designers, and promoting minorities. Therefore, the way the media defines luxury shows that it is more about building a cultural meaning and playing a social role by empowering luxury actors (e.g. curating designers) alongside enhancing people’s well-being

Artisans, as stakeholders, lie at the heart of luxury craftsmanship, aesthetics, and exclusiveness. From a craftsperson’s standpoint, luxury is defined by its excellence and the highest quality of goods (Fuchs, Schreier, and Van Osselaer Citation2015). Craftspeople and their artisanal knowhow represent a critical success factor for many luxury houses (Caniato et al. Citation2009) across various sectors (e.g. fashion, jewelry, home design, and gastronomy). Craftsmanship is tied to luxury in the minds of consumers who perceive it in terms of high-quality materials and fabrics, ancestral manufacturing methods, transmission of knowhow, and the elite professional training of craftspeople. Moreover, craftspeople are considered to be vital actors in the conception, definition, and establishment of luxury brands (Wang Citation2022).

On the one hand, craftspeople constitute a critical touchpoint (De Keyser et al. Citation2020) as they can affect consumers’ attitudes towards the luxury identity of a brand. Indeed, craftspeople’s handcrafted and artisanal knowhow enhances consumers’ perceptions of luxuriousness while emotionally engaging them in meaningful brand experiences (Armitage and Roberts Citation2016). Therefore, artisans – highly qualified craftspeople – contribute to the definition of luxury by incarnating and emphasizing a brand’s values and heritage (Mainolfi Citation2020), along with the brand’s history, knowhow, and creativity. Doing so emphasizes the uniqueness and exclusiveness of luxury goods, which should be fostered and sustained over time.

On the other hand, craftspeople are not only involved in the upstream process of making luxury products; craftspeople can also be part of luxury offerings. In luxury gastronomy, Michelin-starred chefs are integral to the luxury dining experience. A consumer’s choice of restaurants depends on the chefs’ names and reputations, their personas, and the personal stories they translate through their culinary arts. Michelin-starred chefs, who are also gastronomic craftspeople, are seen as artists and rock stars (i.e. customers often take selfies with them and ask them for autographed menus). In this sense, craftspeople are crucial in creating highly engaging and unique luxury experiences in which customers are fully immersed and enchanted. Studies show that interactions with craftspeople enhance a consumer’s perceptions of the craftsmanship’s uniqueness and superior quality (Israel, Jiang, and Ross Citation2017) and also justify the premium prices charged in the luxury sector. Therefore, finding creative talent and training the next generation of young artisans is a top priority for luxury houses. For Grönroos and Voima (Citation2013), talented craftspeople are important for luxury brands in terms of enhancing the value-in-exchange (Hawley and Frater Citation2017) by using their creative artistic ideas and concepts to create tangible products and items. However, luxury houses, particularly in countries acknowledged for their luxury maisons, such as France and Italy, are finding it hard to attract new craftspeople (Tarquini, Mühlbacher, and Kreuzer Citation2022). This is especially the case among youth generations who are not keen on doing manual labor and working in handcrafted industries (Tarquini, Mühlbacher, and Kreuzer Citation2022).

In marketing, studies that define luxury from the perspective of craftsmanship can be classified as follows: a company’s definition of luxury craftsmanship; and the consumer’s perception of luxury craftsmanship. From a managerial perspective, luxury is defined by its unique craftsmanship. It creates the DNA of the luxury brand (Ko, Costello, and Taylor Citation2019), which makes luxury products stand out in the mass market and distinguishes them from nonluxury products (Amatulli et al. Citation2017). A company-centric definition of luxury craftmanship encompasses tangible and intangible elements, such as product quality and detail-focused packaging (Brun and Castelli Citation2013), durability (Israel, Jiang, and Ross Citation2017), and heritage (Nueno and Quelch Citation1998), among others.

In contrast, a consumer perspective on luxury craftsmanship focuses on individuals’ motivations to purchase luxury products (Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004). These studies show that luxury craftsmanship is a powerful element when it comes to communicating meanings, values, and emotions to customers while enhancing their perceptions of luxuriousness and exclusivity (Wang Citation2022). Moreover, consumers being able to watch luxury craftspeople at work results in a highly engaging artistic and multisensory experience (Dallabona Citation2014) – one that generates a positive emotional reaction, which strongly connects customers with a brand and improves their experiences.

The future of luxury: research directions

This review article proposes a comprehensive framework for conceptualizing luxury by identifying its multidimensional and multilevel aspects that often create confusion among scholars. Yet although three categories – theoretical lenses, stakeholders, and units of analysis – should be considered while defining luxury, it is critical to keep in mind that luxury meaning is not static. It evolves with the evolution of societies, the rise of new social trends and movements, the advent of new consumers, emerging luxury countries (e.g. African luxury, Asian luxury, etc.), and digital transformation. All can significantly impact the definition of luxury products and their consumption.

In this article, I emphasized the importance of key stakeholders involved in defining luxury, including consumers, the media, and institutions. However, luxury scholars should consider new incumbents and indirect stakeholders who belong to the digital sector, such as Amazon, Meta, and Vestiaire Collective (a secondhand luxury e-commerce website). These market actors are joining the luxury sector and thus redefining the meaning of luxury. Digital players are investing in the luxury sector and are hiring skilled artisans from luxury and fashion industries to establish themselves as legitimate stakeholders in the luxury sector. For example, Amazon has launched its own online luxury store whereby designers can directly introduce their creations to fashion fans. Initially, only subscribers to Amazon’s Prime service in the United States were invited to access this service. Oscar de la Renta was the first brand to join the online store with its 2020 collections. Other luxury brands will follow, creating a new online place where luxury practices are being redefined.

The integrative framework proposed in this article allows scholars to examine luxury from a holistic perspective and thus prevent the narrow and siloed vision related to its actual conceptualization. In its application, the framework allows scholars to capture the meaning of luxury, its values, and the perspectives followed to define it within a constantly changing and shifting context. Therefore, the luxury conceptualization introduced in this article opens up three main research paths: phygital luxury, transformative luxury, and luxury well-being so as to advance studies on luxury and its evolution over time and across cultures.

The first research area scholars should consider is related to the digital revolution and the new emerging hybrid setting, namely phygital (Batat Citation2022a). Although many scholars have examined consumers’ online luxury purchase behaviors (Wang Citation2022) and the presence of luxury brands on social media (Chapman and Dilmperi Citation2022), most of these studies do not consider the connection of digital luxury with physical luxury and the continuum or rupture created by the shift from online to offline, and vice versa. Phygital luxury is the only approach that allows a continuum between physical and digital experiences and thus offers immersive and satisfying luxury experiences to customers. Consequently, examining phygital luxury as a new ecosystem will be a major challenge for scholars in the future. It will require redefining luxury in new settings that integrate both physical (offline) and digital (online) channels. Future research should therefore focus on phygital luxury and identify what the main consumption features and behaviors related to phygital luxury are. This is a growing field of research that remains largely unexplored.

The second research area refers to the rise of a new set of works that consider the impact of luxury on the environment, society, and stakeholders. These studies are gathered under a new stream, namely transformative luxury research (TLR), grounded in the transformative consumer research literature (Davis and Pechmann Citation2020). TLR, an emerging field in marketing (Batat Citation2022b), defines luxury in terms of its likely positive impact at the individual, social, and environmental levels. Further studies should explore the emerging meanings related to the rise of sustainable practices in the luxury sector, along with the new actors and brands redefining the luxury industry by injecting social meanings framing a new vision of more responsible and positive luxury business models.

Lastly, future research on the conceptualization of luxury should consider its impact on people’s collective and individual well-being, especially in the post-pandemic era where luxury brands were invested in the well-being of different parties, including employees and consumers. There is a need for scholars to examine how luxury relates to providing happiness and well-being. Future studies should focus on the process that improves people’s well-being when consuming or purchasing luxury goods. Because luxury can also be defined as an emotional support for individuals (Petersen, Dretsch, and Komarova Loureiro Citation2018), more research is needed to examine the strategies luxury brands pursue to improve people’s well-being internally (their employees) and externally (their customers as well as their suppliers). Although existing studies have shown that the emotional meaning of luxury is a source of positive emotional experiences, future works can explore additional well-being pillars, such as the relationship between luxury and people’s cognitive or social well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, C. T., S. Fournier, and F. Miller. 2008. “Brands and Their Meaning Makers.” In Handbook of Consumer Psychology, edited by C. Haugtvedt, P. Herr, and F. Kardes, 781–822. NJ: Erlbaum.

- Amatulli, C., M. De Angelis, M. Costabile, and G. Guido. 2017. Sustainable Luxury Brands: Evidence from Research and Implications for Managers. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Armitage, J., and J. Roberts. 2016. Critical Luxury Studies: Art, Design, Media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Arnould, E. J., and C. J. Thompson. 2005. “Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (4): 868–882. doi:10.1086/426626

- Atwood, J. A. 2004. “Heidegger and Gadamer: Truth Revealed in Art.” Eudaimonia: The Georgetown Philosophical Review 1 (1): 48–54.

- Batat, W. 2019. The New Luxury Experience: Creating the Ultimate Customer Experience. New York: Springer.

- Batat, W. 2022a. “What Does Phygital Really Mean? A Conceptual Introduction to the Phygital Customer Experience (PH-CX) Framework.” Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–24. doi:10.1080/0965254X.2022.2059775.

- Batat, W. 2022b. “Transformative Luxury Research (TLR): An Agenda to Advance Luxury for Well-Being.” Journal of Macromarketing 42 (2): 609–623. doi:10.1177/02761467221135547

- Batat, W., and G. De Kerviler. 2020. “How Can the Art of Living (Art De Vivre) Make the French Luxury Industry Unique and Competitive?” Marché & Organisations n° 37 (1): 15–32. doi:10.3917/maorg.037.0015

- Bearden, W. O., and M. J. Etzel. 1982. “Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decisions.” Journal of Consumer Research 9: 183–194. doi:10.1086/208911

- Berger, J., and M. K. Ward. 2010. “Subtle Signals of Inconspicuous Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (4): 555–569. doi:10.1086/655445

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brun, A., and C. Castelli. 2013. “The Nature of Luxury: A Consumer Perspective.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41 (11/12): 823–847. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-01-2013-0006

- Caniato, F., M. Caridi, C. M. Castelli, and R. Golini. 2009. “A Contingency Approach for SC Strategy in the Italian Luxury Industry: Do Consolidated Models Fit?” International Journal of Production Economics 120: 176–189. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2008.07.027

- Chapman, A., and A. Dilmperi. 2022. “Luxury Brand Value Co-Creation With Online Brand Communities in the Service Encounter.” Journal of Business Research 144: 902–921. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.068

- comitecolbert.com. 2022. Accessed August 2022. https://www.comitecolbert.com/.

- Dallabona, A. 2014. “Narratives of Italian Craftsmanship and the Luxury Fashion Industry: Representations of Italianicity in Discourses of Production.” Global Fashion Brands: Style, Luxury & History 1 (1): 215–228. doi:10.1386/gfb.1.1.215_1

- Davis, B., and C. Pechmann. 2020. “The Characteristics of Transformative Consumer Research and How It Can Contribute To and Enhance Consumer Psychology.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 30 (2): 365–367. doi:10.1002/jcpy.1139

- De Keyser, A., K. Verleye, K. N. Lemon, T. L. Keiningham, and P. Klaus. 2020. “Moving the Customer Experience Field Forward: Introducing the Touchpoints, Context, Qualities (TCQ) Nomenclature.” Journal of Service Research 23 (4): 433–455. doi:10.1177/1094670520928390

- Dubois, B., and P. Duquesne. 1993. “The Market for Luxury Goods: Income Versus Culture.” European Journal of Marketing 27: 35–44. doi:10.1108/03090569310024530

- Fibich, G., A. Gavious, and O. Lowengart. 2005. “The Dynamics of Price Elasticity of Demand in the Presence of Reference Price Effects.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 33: 66–78. doi:10.1177/0092070304267108

- Forbes. 2018. “4 Mega-Trends Ahead for the Luxury Market in 2019: Expect Turmoil and Slowing Sales.” Forbes. Accessed August 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pamdanziger/2018/12/18/whats-ahead-for-the-luxury-market-in-2019-expect-turmoil-and-slowing-sales/.

- Foundation Altagamma. 2022. https://altagamma.it/en/chi-siamo/. Accessed August 2022.

- Fournier, S. 1998. “Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 24: 343–353. doi:10.1086/209515

- Freeman, R. E., S. Dmytriyev, and R. A. Phillips. 2021. “Stakeholder Theory and the Resource-Based View of the Firm.” Journal of Management 47: 1757–1770. doi:10.1177/0149206321993576

- Fuchs, C., M. Schreier, and S. M. J. Van Osselaer. 2015. “The Handmade Effect: What’s Love Got To Do With It?” Journal of Marketing 79 (2): 98–110. doi:10.1509/jm.14.0018

- Gardner, H. 1993. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

- Grönroos, C., and P. Voima. 2013. “Critical Service Logic: Making Sense of Value Creation and Co-Creation.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

- Hagtvedt, H., and V. M. Patrick. 2009. “The Broad Embrace of Luxury: Hedonic Potential as a Driver of Brand Extendibility.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 19: 608–618. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2009.05.007

- Hall, S. 2004. “Encoding/Decoding.” In Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–1979, edited by S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis, 166–176. London: Routledge.

- Han, Y. J., J. Nunes, and X. Dreze. 2010. “Signaling Status With Luxury Goods: The Role of Brand Prominence.” Journal of Marketing 74 (4): 15–30. doi:10.1509/jmkg.74.4.015

- Hawley, J., and J. Frater. 2017. “Craft’s Path to the Luxury Market: Sustaining Cultures and Communities Along the Way.” In Sustainable Management of Luxury, Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes, edited by M. G. Gardetti, 387–407. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Hemetsberger, A. 2018. “The Vice of Luxury: Economic Excess in a Consumer Age.” Consumption Markets & Culture 21: 286–289. doi:10.1080/10253866.2016.1209294

- Ho, F. N., and J. Wong. 2022. “Disassociation from the Common Herd: Conceptualizing (In)conspicuous Consumption as Luxury Consumer Maturity.” Consumption Markets & Culture: 1–16. doi:10.1080/10253866.2022.2066655.

- Huang, A., J. Dawes, L. Lockshin, and L. Greenacre. 2017. “Consumer Response to Price Changes in Higher-Priced Brands.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 39: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.009

- Iqani, M. 2022. ““One Day You’ll Buy a Rolex from Me”: Reflexivity and Researcher Decoding Positions in Luxury Research.” Consumption Markets & Culture: 1–13. doi:10.1080/10253866.2022.2094920.

- Israel, R., S. Jiang, and A. Ross. 2017. Craftsmanship Alpha: An Application to Style Investing. Accessed June 2022. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3034472.

- Ko, E., J. Costello, and C. R. Taylor. 2019. “What is a Luxury Brand? A New Definition and Review of the Literature.” Journal of Business Research 99: 405–413. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.023

- Mainolfi, G. 2020. Heritage, Luxury Fashion Brands and Digital Storytelling. London: Routledge.

- Mason, R. 1984. “Conspicuous Consumption: A Literature Review.” European Journal of Marketing 18 (3): 26–39. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000004779

- Mendonça, M. 2020. “Understanding Luxury: A Philosophical Perspective.” In Understanding Luxury Fashion. Palgrave Advances in Luxury, edited by I. Cantista and T. Sádaba. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nueno, J. L., and J. A. Quelch. 1998. “The Mass Marketing of Luxury.” Business Horizons 41 (6): 61–68. doi:10.1016/S0007-6813(98)90023-4

- Palmer, A., and S. Ponsonby. 2002. “The Social Construction of New Marketing Paradigms: The Influence of Personal Perspective.” Journal of Marketing Management 18 (1&2): 173–192. doi:10.1362/0267257022775864

- Petersen, F. E., H. J. Dretsch, and Y. Komarova Loureiro. 2018. “Who Needs a Reason to Indulge? Happiness Following Reason-Based Indulgent Consumption.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 35 (1): 170–184. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2017.09.003

- Podoshen, J. S., L. Li, and J. Zhang. 2011. “Materialism and Conspicuous Consumption in China: A Cross-Cultural Examination.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 35: 17–25. doi:10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00930.x

- Raniwala, P. 2021. “The Changing Definition of Luxury in 2021.” Vogue India. Accessed August 2022. https://www.vogue.in/fashion/content/the-changing-definition-of-luxury-in-2021.

- Roper, S., R. Caruana, D. Medway, and P. Murphy. 2013. “Constructing Luxury Brands: Exploring the Role of Consumer Discourse.” European Journal of Marketing 47: 375–400. doi:10.1108/03090561311297382

- Schmitt, B. H., J. J. Brakus, and L. Zarantonello. 2015. “From Experiential Psychology to Consumer Experience.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 25 (1): 166–171. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.09.001

- Schrage, D. 2012. “The Domestication of Luxury in Social Theory.” Social Change Review 10 (2): 177–193. doi:10.2478/scr-2013-0017

- Tarquini, A., H. Mühlbacher, and M. Kreuzer. 2022. “The Experience of Luxury Craftsmanship – A Strategic Asset for Luxury Experience Management.” Journal of Marketing Management 38: 1307–1338. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2022.2064899.

- Thompson, C. J., and D. L. Haytko. 1997. “Speaking of Fashion: Consumers’ Uses of Fashion Discourses and the Appropriation of Countervailing Cultural Meanings.” Journal of Consumer Research 24 (1): 15–42. doi:10.1086/209491

- Thomsen, T. U., J. Holmqvist, S. V. Wallpach, A. Hemetsberger, and R. W. Belk. 2020. “Conceptualizing Unconventional Luxury.” Journal of Business Research 116: 441–445. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.058

- Turunen, L. L. M. 2018. “Concept of Luxury Through the Lens of History.” In Interpretations of Luxury. Palgrave Advances in Luxury. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60870-9_2.

- Valsesia, F., D. Proserpio, and J. C. Nunes. 2020. “The Positive Effect of Not Following Others on Social Media.” Journal of Marketing Research 57 (6): 1152–1168. doi:10.1177/0022243720915467

- Veblen, T. [1899] 2005. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. New Delhi: Aakar Books.

- Vigneron, F., and L. W. Johnson. 2004. “Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury.” Journal of Brand Management 11 (6): 484–506. doi:10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540194

- Visconti, L. M. 2008. “Gays’ Market and Social Behaviors in (De)constructing Symbolic Boundaries.” Consumption Markets & Culture 11 (2): 113–135. doi:10.1080/10253860802033647

- Vogue. 2021. “Luxury is Culture Now. Here’s How.” Vogue. Accessed August 2022. https://www.voguebusiness.com/companies/how-luxury-brands-become-cultural-curators-gucci-saint-laurent-vetements.

- von Pezold, J., and T. Tse. 2022. “Luxury Consumption and the Temporal-Spatial Subjectivity of Hong Kong Men.” Consumption Markets & Culture (in-press). doi:10.1080/10253866.2022.2120868

- Wang, Y. 2022. “A Conceptual Framework of Contemporary Luxury Consumption.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 39 (3): 788–803. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.10.010

- White, D. A. 1970. “Revealment: A Meeting of Extremes in Aesthetics.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 28 (4): 515–520. doi:10.2307/428492

- Wiedmann, K., N. Hennigs, and A. Siebels. 2009. “Value-Based Segmentation of Luxury Consumption Behavior.” Psychology and Marketing 26: 625–651. doi:10.1002/mar.20292

- Wierzba, L. 2015. “What is Luxury? Curating Connections Between the Hand-Crafted and Global Industry.” Luxury 2: 9–23. doi:10.1080/20511817.2015.11428562

- Wiesing, L., and N. A. Roth. 2019. A Philosophy of Luxury. London: Routledge.

- Wirtz, J., J. Holmqvist, and M. P. Fritze. 2020. “Luxury Services.” Journal of Service Management 31 (4): 665–691. doi:10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0342

- Wu, Z., J. Luo, J. E. Schroeder, and J. L. Borgerson. 2017. “Forms of Inconspicuous Consumption: What Drives Inconspicuous Luxury Consumption in China?” Marketing Theory 17 (4): 491–516. doi:10.1177/1470593117710983