Abstract

In 2008, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) announced that in the next few decades, it will be essential to study the various biological, psychological and social “signatures” of mental disorders. Along with this new “signature” approach to mental health disorders, modifications of DSM were introduced. One major modification consisted of incorporating a dimensional approach to mental disorders, which involved analyzing, using a transnosological approach, various factors that are commonly observed across different types of mental disorders. Although this new methodology led to interesting discussions of the DSM5 working groups, it has not been incorporated in the last version of the DSM5. Consequently, the NIMH launched the “Research Domain Criteria” (RDoC) framework in order to provide new ways of classifying mental illnesses based on dimensions of observable behavioral and neurobiological measures. The NIMH emphasizes that it is important to consider the benefits of dimensional measures from the perspective of psychopathology and environmental influences, and it is also important to build these dimensions on neurobiological data. The goal of this paper is to present the perspectives of DSM5 and RDoC to the science of mental health disorders and the impact of this debate on the future of human stress research. The second goal is to present the “Signature Bank” developed by the Institut Universitaire en Santé Mentale de Montréal (IUSMM) that has been developed in line with a dimensional and transnosological approach to mental illness.

Mental health research in the twenty-first century

The period from 1990 to 2000 has been termed the decade of the brain (Health, 2015), leading to major discoveries in the field of genetics, neuroimaging and degenerative disorders (Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2010, Citation2013). Based on these significant discoveries, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States announced in its 2008 strategic plan (Health, Citation2008) that the next decade would be devoted to applying the acquired knowledge to patient populations suffering from mental health disorders. In other words, it would be committed to making this period the “decade of the patient”.

According to the NIMH, mental health research must correspond to the four Ps of personalized medicine – Predictive, Preemptive, Personalized and Participatory – in order to be innovative. To accomplish this, it will be essential to study the various biological, psychological and social “signatures” of mental disorders as well as the interactions between different biological signatures, clinical manifestations and psychosocial determinants of mental health across the lifespan and as a function of exposure to different environments. The “signatures” of mental illness is a term formulated by the NIMH to designate the broad range of biological, psychological and social factors that may “sign” a specific mental health disorder, depending on an individual’s sex, history, lifestyle habits and so on (Health, Citation2008, Citation2015).

Personalized mental health medicine represents an approach specifically adapted to the challenges of twenty-first century health, especially with regard to chronic illnesses. Chronic illnesses are now recognized as being the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in contemporary societies, as well as the main drivers of health service utilization and associated expenses. In the health care system, mental health disorders are among the most common and costly chronic illnesses (Reeves et al., Citation2011). In 2004, an estimated 25% of adults in the United States reported having a mental illness in the previous year (Reeves et al., Citation2011), and this led to a total cost of $300 billion in 2002. Despite this, mental illnesses do not always receive the attention they deserve, and those affected by mental illness do not receive all the treatment they need, since current research is still being conducted in a non-concerted manner, with researchers separately seeking to identify the gene, the biomarker or the psychological factor that predicts a mental illness categorized as a function of symptoms rather than validated medical tests.

At the present time, there is significant growth in the area of developing genetic biobanks that enable long-term storage of DNA samples with the goal of later studying various diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disorders. However, the studies conducted to date on the genetic causes of mental disorders have had little success, and the NIMH suggested that this failure may be due to the fact that researchers are still looking for a single signature of mental illness when they should instead be seeking multiple signatures (Health, Citation2008). The fact is, to understand complex chronic illnesses such as mental diseases, it is necessary to be innovative and move away from a reductionist approach that basically involves identifying one gene or one brain abnormality as the factor explaining a mental disorder.

One of the main reasons that have been given to explain the failure of biological mental health studies is the absence of a good phenotypic classification (Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2010, Citation2013; Kapur et al., Citation2012). Here, it has been suggested that neurobiological studies have been unable to find any genetic or neuroscientific evidence or a single “biological signature” of the different categories of mental illnesses proposed by DSM over its various versions (Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2013; Doherty & Owen, Citation2014; Insel et al., Citation2010), because the phenotype used in these studies, i.e. the diagnostic criteria as determined by DSM categories, is not the best phenotype to use in order to determine the biological signature of mental illness (Casey et al., Citation2013; Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2010; Insel et al., Citation2010).

The categorical approach to mental health disorders

Long before the first edition of the DSM was published in 1952, it was recognized that there was a need to distinguish between diseases – i.e. to differentiate between various pathologies when choosing a treatment. Indeed, the more clearly various problems were distinguished, the greater the likelihood of successful medical treatment. It was Emil Kraepelin who developed the first classification system resembling what is now found in the DSM. His Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie categorized mental disorders based on their nature, and he developed hypotheses about their causes, evolution and prognoses (see Kohl, Citation1999a,Citationb).

Since DSM-I was published, many revisions have been made in order to provide caregivers and researchers with the most up-to-date data. However, across all of the versions of DSM, there is one common assumption, i.e. such a categorical approach to mental illnesses assumes that mental disorders are discrete entities shared by relatively homogeneous populations that will display similar symptoms of any given disorder. Based on this definition, a categorical diagnosis can thus only have two values, i.e. presence or absence of a given disorder. Over the years, there have been various discussions about the validity of the way these diagnostic categories are constructed. Three main critics of the categorical approach to psychiatry have been raised in the scientific literature over the years.

First, it has been stated that the first assumption of the categorical approach (i.e. “mental disorders are discrete entities shared by homogeneous populations”) is not valid. Indeed, it is well known that psychiatric populations are highly heterogeneous and it is highly common to see patients showing more than one clear psychiatric diagnosis (Regier, Citation2008; Widiger & Coker, Citation2003). This heterogeneity led, over the years, to the diagnostic category of “Not otherwise specific” (NOS; First, Citation2010). The NOS category is often referred to as the “catch-all” category (Millon, Citation1991). It is generally used when a clinician determines that a mental illness is present, although the patient fails to meet the criteria for one of the existing diagnostic category. Although this category should be given rarely, studies show that the NOS category is used as often as any of the specific diagnostic categories of the DSM (Cassano et al., Citation1999; Fairburn et al., Citation2007; Wilberg et al., Citation2008).

Second, although a categorical diagnostic approach considers that patients suffering for a given mental illness display similar symptoms, we now know that there is a lot of overlap of symptoms in psychiatric populations, and this explains the high level of comorbidities observed in patients. “Pure” psychiatric syndromes are extremely rare in psychiatric research, and it is very common to see patients receiving two, three and even four types of psychiatric diagnoses (Andrews et al., Citation2002; Kessler et al., Citation1996; Mineka et al., Citation1998). For example, an Australian study of 10,000 participants reported that 40% of the sample met the diagnostic criteria for more than one current mental health disorder (Andrews et al., Citation2002). Moreover, mood disorders show high comorbidity with anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., Citation1996; Mineka et al., Citation1998), and mood and anxiety disorders are comorbid with substance use disorders, personality disorders and eating disorders (Mineka et al., Citation1998; Widiger & Clark, Citation2000). This suggests that there might be a problem with the “phenotype” of mental illness, i.e. an organism's observable characteristics or traits related to a particular mental disorder (Kupfer, Citation2005).

Third, studies on childhood and adolescence often report that psychiatric categories, as defined by the DSM, are unable to capture a common source of variation in developmental psychopathology: the stage of development (see Beauchaine & McNulty, Citation2013). Indeed, more and more studies report that the psychiatric diagnostic category seems to change with a child or teenager’s development (Cuthbert & Kozak, Citation2013). Clinicians and scientists have also criticized the fact that certain criteria do not sufficiently account for the full complexity of the psychopathological phenomena experienced by children and adolescents suffering from various forms of psychopathologies (Haggerty et al., Citation1996; Rutter, Citation2003; Rutter et al., Citation2003; Rutter & Sroufe, Citation2000). Consequently, the principle of categorization limits the ability to capture nuances that could be used to indicate the intensity of various symptoms or their evolution over time.

A new dimensional approach to mental disorders

Despite the millions of research dollars that were spent on trying to find the “biomarker” of a specific mental health disorder as defined by the DSM, not a single study led to the discovery of a biological test with a clinical utility to diagnose a given mental illness. Consequently, various scientists started to question the reason for this failure.

In an important paper published in 2012, Kapur et al. (Citation2012) suggested that four main factors can explain this failure. First, compared to other medical fields that have biological tests to diagnose disorders, the field of psychiatry did not find any biological marker that can differentiate between patients and control and/or between patients. Second, although there has been a very large number of studies published on neurobiological dysfunctions in various mental disorders, most of these studies have small or moderate effect sizes, even though group differences are significant at p < .05. This led to a tremendous number of scientific papers published on various “biomarkers” of mental disorders, but no single consensus on a single clinical test that could be efficient at distinguishing a given mental illness. Third, replication studies are extremely rare in psychiatry and the majority of studies that try to replicate a given finding include small variations in patient populations, measures and/or biological measures, which lead to “approximate replications”. When this happens, any difference between two studies is explained by differences in patients populations, measures or biological tests, and this prevents the development of significant biological tests for a given mental illness. Finally, most studies in psychiatric research compare prototypical patients and “picture-perfect” healthy controls, which leads to significant results that may be difficult to replicate when one tries to distinguish between different patient types. Based on Kapur and colleagues review (Kapur et al., Citation2012), all of these factors led to a Catch-22 where the current diagnostic system was not designed to facilitate biological differentiation, and the biological studies have not been able to propose a clinically viable alternative system.

Based on this analysis, they suggested that in order to provide clinical tests of psychiatric disorders, the field of biological psychiatry will have to change its mindset. Rather than having a strict allegiance on DSM or ICD diagnostic categories, the field should collect data across the current diagnostic categories, focus on comparing across disorders as much as comparing patients to control subjects, and should collect longitudinal data so that we can move toward the development of biological clinical tests for mental illness (Kapur et al., Citation2012).

The DSM-5 dimensional approach

The first attempt to develop such a transnosological approach was made by various committees working on the fifth version of the DSM. In 2000, over 500 world-renowned researchers and clinicians were invited to be involved in the DSM revision process. In addition to the general revision of diagnostic criteria for each disorder and a somewhat different approach to organizing disorders, modifications were being proposed that would affect most, if not all, mental disorders in the DSM.

One of the major modifications in the DSM-5 consisted of incorporating a dimensional approach to mental disorders, which would involve analyzing various dimensions or functions that are associated with many different types of mental disorders. For example, anxious symptoms occur in conjunction with many mental disorders, and consequently, the presence of anxiety in a given patient may therefore be enough to “sign” a mental disorder and cut across various diagnoses. Consequently, the nature of the anxiety could indicate an individual’s underlying vulnerability to specific disorders.

The DSM would continue to propose diagnostic categories of mental disorders, but would include this new, dimensional approach. Various working groups were developed between 2000 and 2012 to work on the revision of the DSM and in July 2006, a diagnosis-related research planning conference focusing on dimensional approaches in diagnostic classification was held at the Natcher Conference Center on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. Twenty-eight invited scientists from around the world participated and worked at delineating the advantages of adding a dimensional approach to the DSM5 (http://www.dsm5.org/research/pages/dimensionalaspectsofpsychiatricdiagnosis(july26-28,2006).aspx). Five general advantages of adding a dimensional approach to DSM-5 were described by this committee.

Greater precision

First, the decision to make use of dimensions in combination with categories was related to the quality of the diagnosis being made rather than the nature of the disorder being diagnosed. For instance, while a dimensional assessment would make it possible to evaluate on a scale with at least three points (e.g. no disorder versus mild disorder versus severe disorder), categorical assessment is by definition limited to two points (e.g. present versus not present). At the level of clinical practice, this restricts the extent to which it is possible to provide a detailed diagnosis. Either the disorder is present or it is not; there are no nuances. At the level of research, being able to use dimensional assessments as well as categorical measures could make it possible to study the potential modulating effect of certain aspects of mental disorders (e.g. anxious symptoms) on the severity of a given mental disorder.

Scientists and clinicians participating in this event suggested that introducing the use of dimensional measures should be entirely feasible given the current state of clinical practice and scientific research. First, dimensional tools (e.g. questionnaires) are already widely used in different fields (e.g. somatic and cognitive symptoms of anxiety, panic, avoidance), and the dimensional approach is already standard in research (e.g. asking about the number of panic attacks). Additionally, there was the possibility of drawing on work being done on other subjects in medicine (e.g. hypertension, obesity). In short, the beneficial effects on clinical practice and research offered by the increased precision and more complex nuances of dimensional measures were clear to the research field. They enhanced the ability to determine the effect of a treatment, enabled greater precision in quantifying that effect, improved the capacity to detect existing signals and made it possible to identify more treatment possibilities.

More faithful to reality

Dimensional measures would make it possible to establish an individual’s risk of a given disease with a greater degree of nuance. An example of this is the “metabolic syndrome,” that is associated with a high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Originally, a person with three of the five risk factors for CVD is deemed to have a metabolic syndrome and be at high risk of CVD. But with two risk factors out of five, an individual is still at risk of CVD; the risk is only slightly reduced. Adopting an approach based on “degree of risk” (dimensional approach) rather than on “at risk” versus “not at risk” dichotomy (categorical approach) therefore would seem appropriate. This approach better represents the reality and makes it possible to intervene in an incremental manner with less severe cases before they become more serious. This also offers a way to resolve the problem of categorical thresholds, given that individuals in a subclinical state may also be negatively impacted by their condition and could benefit from treatment.

This kind of dimensional approach would refine diagnoses and go above the problem of comorbidities. For example, patients often present not just with their diagnostic symptoms but also with a whole range of other symptoms and associated clinical characteristics. Dimensional assessment would make it possible to identify both the presence and the severity of symptoms. It would make it possible to understand the evolution of a clinical condition with greater precision (e.g. identify improvement even though the symptom remains), and it would encourage clinicians to document a patient’s overall symptomatology and not just those symptoms directly related to the primary diagnosis.

Enables more accurate prognosis

A dimensional approach would also enable more accurate prognosis. For instance, in the area of depression, differing levels of severity are associated with different therapeutic outcomes for antidepressants and/or psychotherapy. A dimensional diagnosis based on the severity of symptoms would make it possible to better predict the patient’s response to treatment as well as the likely timeframe until the disorder goes into remission.

Enables better understanding of comorbidity

One of the problems with DSM-IV-TR was the high degree of overlap between the criteria for various disorders – in other words, comorbidity. An example is depression and anxiety, which are often concomitant. It is possible that there is an underlying dimension that could explain this common instance of comorbidity by accounting for both disorders. In addition, disorders that appear in various stages of development, such as depression, can be better conceptualized, measured and classified when considered in terms of dimensions rather than categories. This is strongly supported by epidemiological data from community-based studies. For example, a study conducted by Dr. Ingvar Bjelland in Norway compared dimensional data and categorical data related to symptoms of depression and anxiety in the general population (Bjelland et al., Citation2009). His research team demonstrated that significant information was lost when continuous data was organized based on categories. It was also found that the dimensional approach was better for describing the symptoms and predicting the outcomes of comorbid anxiety and depression.

Better characterization of developmental disorders

Participants at the meeting also raised the point that it is important to consider the benefits of dimensional measures from the perspective of developmental psychopathology. There are currently thousands of studies on childhood and adolescence that have used dimensional measures combined with categorical measures. In these studies, one can see that categories are unable to capture a common source of variation in developmental psychopathology: the stage of development. Indeed, more and more studies report that the psychiatric diagnostic category seems to change with a child’s development, and it is therefore possible that evaluating more general dimensions could better account for the nature and complexity of the underlying mental disorder during the child’s development, compared to an approach based strictly on categorical diagnosis.

The teams working on the development of DSM-5’s generally agreed that the main goal of adding dimensions was to provide supplemental information that clinicians may employ during evaluation, treatment planning and follow-up of the patient’s condition in response to the treatment received. In addition, it was hoped that these dimensional assessments would transcend the various disorders (i.e. they would not be limited by the definitions of different disorders) and they would provide quantitative measures for the most important clinical areas, meaning those that are most often observed and assessed in patients, regardless of their diagnosis. Dimensional assessments would therefore not refer to specific disorders and would not serve as screening tests for disorders in the DSM. They would be intended to complement diagnostic categories rather than replace them. Moreover, dimensional assessments would be a major asset for scientific research on the biological, psychological and social signatures of mental disorders in that they would enable quantitative analysis of the severity and extent of vulnerability to various mental disorders.

The DSM-5 Task Force proposed that assessments of dimensions be performed at two levels. Level 1 assessments would be self-report assessments evaluating major clinical domains such as depressed mood, anxiety, suicide risk, sleep disturbance, early childhood adversity and substance use. It has also been proposed that separate assessments be used for children and adults (Dayle-Jones, Citation2012). Then, if any Level 1 domain is rated as being clinically significant, the clinician would complete the Level 2 assessment that would consist of a more specific questionnaire to determine the nature and/or magnitude of the dimension rated as significant at Level 1.

Measuring dimensions in clinical and research practice

As we can see above, dimensional assessments are basically rating scales that measure the frequency, duration, and severity of psychological and/or mental states associated with various mental disorders. Although the dimensional classification approach clearly offered some advantages over the categorical approach, three main objections were also raised about dimensional assessments.

First, given the fact that dimensions involve assessing a set of symptoms on a rating scale (rather than using a checklist approach as in the categorical approach), it has been stated that dimensional assessments are more complex than diagnostic categories, which renders them laborious and time consuming in clinical practice (First, Citation2010). Second, although dimensional assessments could clearly have advantages for better classifications of mental disorders, another criticism involved the choice of scales to be used and methods to obtain these data. It has been raised that the DSM-5 Task Force was creating new dimensional scales to be used rather than choosing from the many hundreds of well-established scales covering every aspect of psychopathology. Given the amount of time, effort and research involved in scale development, scientists raised the fact that such an approach would prevent any further development and validation of dimensional assessment in psychiatry (Frances, Citation2010). Third, questions were raised by the clinical field as to how these dimensions would be measured in patients. The main approach in psychiatry has been structured interviews by professionals to validate categorical diagnosis. However, the notion of dimensions involved a very important shift in clinical psychiatry, i.e. the importance of using patient-reported outcomes as a measure of dimensions.

The benefits of patient-reported measures

Although very rarely used in clinical practice based on DSM categorization, self-report or patient-report measures have been widely used in psychology and/or psychiatric research. Questionnaires have been developed and used in psychological research for more than a century (Gault, Citation1907). In the majority of cases, self-report measures are used when the information and/or the mental health construct (emotion, thoughts, etc.) to be obtained is only known by the patient. Such “patient-report outcomes” (PRO) have largely been integrated in clinical practice in other fields of medicine such as arthritis (Aletaha et al., Citation2008) and cancer (Lipscomb et al., Citation2007; Sprangers et al., Citation2013) but these measures have not yet been fully integrated in mental health clinical practice.

One of the major reasons raised by clinicians to prefer clinical interviews to self-report measures concerns the reliability and validity of self-reports in individuals with cognitive deficits, emotional biases or mental illness (Riley et al., Citation2011). It has been suggested that given that the mental state of a psychiatric patient can dramatically change from time to time, this may lead to low reliability of answers on self-report measures (see Riley et al., Citation2011). Given the lack of longitudinal study assessing dimensional characteristics of mental illness, there are no data to this day that can confirm this suggestion.

Be this as it may, it became clear for the DSM5 working groups that inclusion of dimensional characteristics in the DSM5 would necessitate the use of self-report questionnaires (Narrow & Kuhl, Citation2011). These working groups therefore recommended that prior to examination by a doctor, clients should fill out questionnaires that enable evaluation of the various DSM5 dimensions. The answers to these questionnaires could then be transferred to the attending psychiatrist and used to guide the clinical interview, confirm a diagnosis or provide periodic assessments for the purpose of capturing the evolution of the patient’s condition over time.

In short, self-report assessments could facilitate the work of clinicians and refine their diagnoses by having patients themselves answered standardized questions. This would decrease the burden on clinician’s work and increase acceptance of dimensional assessments by psychiatrists. Additionally, it was suggested that self-report questionnaires might enhance clients’ sense of empowerment by making them a full-fledged participant in the process of treatment and recovery. The NIMH has stated that this approach makes it possible to address the last two Ps of personalized medicine, i.e. personalizing the approach to patients and integrating the latter’s active participation into treatment and rehabilitation (Narrow & Kuhl, Citation2011).

Interestingly, in 2004, the NIH implemented a “Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System” (PROMIS), with the goal to integrate web-based standard self-report measurements of various health indicators and symptoms across common medical conditions (Cella et al., Citation2007). This trans-NIH Roadmap Initiative was developed in order to integrate, within a single database, the diverse array of outcome measures used in clinical research. Such a common database would allow comparison of outcome measures across medical disorders and its web-based approach would facilitate the work of clinicians obtaining these measures.

In the first three years of its existence, the PROMIS network developed databases for assessing patient reports regarding their pain, fatigue, emotional distress, physical functioning, sleeping/waking patterns and social functioning (Cella et al., Citation2007; Riley et al., Citation2011). PROMIS validation studies have shown that this method of collecting data via technology tools is not only more secure in terms of data confidentiality but is also supported by empirical research: i.e. users of psychiatric services are likely to answer computerized questionnaires, and data obtained by such means have a normal distribution across various populations (children, teenagers and adults) suffering from mental disorders (Cook et al., Citation2012; Forrest et al., Citation2012). Based on the new technological tools developed by the NIH, it was thus suggested that the dimensions of DSM5 could be easily assessed through this NIH-funded initiative and the results obtained would lead to a better characterization of mental illness.

The end of the DSM5 dimensional approach

Although considerable work had been performed on the new dimensional approach of the DSM5, in July 2011, the DSM5 WorkForce published a paper in which it announced that it dropped the idea of including dimensions in the new DSM5 (see Kupfer & Regier, Citation2011). One of the main reasons for this was that the research data on biomarkers, imaging and genetics of mental illness were not sufficient to allow for the choice and/or clinical assessment of valid dimensions (Kupfer & Regier, Citation2011; Regier et al., Citation2012).

However, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in charge of the DSM5 development included a number of “emerging measures” in Section III of DSM5 that are now called “Cross-Cutting Symptom Measures”. These measures assess the 13 domains presented in and the APA proposes to measure these cross-cutting symptoms by the questionnaires described in . The dimensional measures described in were included in the field trials performed to assess the validity and reliability of the DSM5 categorical diagnosis (Clarke et al., Citation2013; Narrow et al., Citation2013; Regier et al., Citation2013).

Table 1. Dimensional measures proposed for DSM-5.

A study was performed in seven sites for adult patients and four sites for child and adolescent patients, and the dimensional measures were self-completed by the patient or an informant (parent and/or legal guardian). The questionnaires were filled twice from 4 h to 2 weeks apart. Results showed that in adults, test–retest reliabilities of the cross-cutting symptom items were good to excellent. In children/adolescents, results showed that parents were reliable reporters of their children’s symptoms, with few exceptions. However, it was also shown that reliabilities were not as uniformly good for child respondents. These results reported promising test–retest reliability results for this group of dimensions (Narrow et al., Citation2013).

Based on these results, the APA now suggests that these patient assessment measures be administered at the initial patient interview and to monitor treatment progress if the clinician chooses to use the dimensional aspect of the DSM5. Consequently, the dimensional assessments are now suggested but are not part of the core foundation of diagnosis. Categorical diagnosis is still the core of the DSM5 diagnostic system.

The NIMH’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework

Clearly, the drop of dimensional measures to be included in the DSM5 was a major challenge for all of those scientists and clinicians who worked on this 25$million dollars project. On 29 April 2013, the Director of the NIMH, Dr. Tom Insel wrote on his blog that “While DSM has been described as a ‘Bible’ for the field, it is, at best, a dictionary, creating a set of labels and defining each. The strength of each of the editions of DSM has been ‘reliability’ – each edition has ensured that clinicians use the same terms in the same ways. The weakness is its lack of validity […] Patients with mental disorders deserve better”.

Dr. Insel went on by describing a new NIMH initiative called the RDoC that is a new framework for collecting data needed for a new nosology of mental illnesses (Insel et al., Citation2010). Dr. Insel added: “It is critical to realize that we cannot succeed if we use DSM categories as the ‘gold standard’”. For Dr. Insel, in order to discover new clinical and medical tests for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, the diagnostic system has to be based on the emerging research data and not on current symptom-based categories. For the NIMH, it is not appropriate to reject a biomarker because it does not detect a DSM category. In these conditions, it might well be the phenotype of the mental health disorder (the diagnostic itself as described by the DSM category), that is not reliable and/or valid. Consequently, there is a need to start collecting genetic, imaging, physiologic and cognitive data to see how all of this data – taken across DSM categories – cluster and how these clusters relate to biology, genes and other important variables in psychopathology (Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2010, Citation2013; Insel et al., Citation2010).

On the same blog entry, Dr. Insel stated that this is why the NIMH will be reorienting its research strategy away from DSM categories. It has been stated that from now on, the NIMH would fund research projects that look across current DSM5 categories in order to learn more about the associations between various dimensions of mental health disorders and biological substrates. This new NIHM approach has a lot of implications for new projects in clinical research. Indeed, rather than comparing patients with a categorized diagnosis of depression to normal controls, a new RDoC study might study all patients in a mood disorder clinic, or even all patients seen at a psychiatric emergency department, to determine specific associations between a particular domain of functioning (e.g. presence of anxiety) and a biological and/or cognitive substrate. Consequently, instead of looking for a biological substrate of “depression”, one might look across many psychiatric disorders associated with anxiety symptoms (e.g. personality disorders, general anxiety disorders, eating disorders and depression) to find a common biological circuitry underlying anxiety symptoms such as high sensitivity to threat. If associations are found between a transnosological symptom (e.g. anxiety and/or measures of sensitivity to threat) and a biological substrate, then the symptom could become a “target” for treatment (Health, 2015). Consequently, the RDoC addresses the need for a new approach to classifying mental disorders and this approach begins with symptoms.

Many NIMH researchers did not welcome this change and raised severe critics with regards to the choice of NIMH to stop funding studies based on DSM5 categories. Consequently, in May 2013, Dr. Insel published a joint statement with Dr. Lieberman, president of the APA (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2013/dsm-5-and-rdoc-shared-interests.shtml). In this publication, it was now stated that although the NIMH considers that “the DSM5 represents the best information currently available for clinical diagnosis of mental disorders [and that] patients, families, and insurers can be confident that […] the DSM5 is the key resource for delivering the best available care”, the director of NIMH also wrote that “the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has not changed its position on DSM5”. Consequently, in a paper published in 2013, Bruce Cuthbert stated that the US NIMH will still give priority to grant applications that cut across diagnostic categories and that applications with traditional designs (e.g. comparing one DSM category to controls) will be given a lower priority (Casey et al., Citation2013), although they may be funded.

With this new approach, the NIMH has given greater flexibility to scientists in designing their studies for obtention of NIMH funding, which allows them to focus on the processes or mechanisms they wish to study rather than just measuring their associations to DSM diagnosis (Cuthbert, Citation2014a). As well, because there is now an explicit focus on the full range of functioning from normal to abnormal, it has been emphasized that the RDoC framework reflects clear priorities at the basis of developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti & Blender, Citation2006; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Citation2002; Cicchetti & Toth, Citation2009; Woody & Gibb, Citation2015).

Nowadays, in all messages from APA and NIMH, it is now emphasized that DSM5 and RDoC are complementary, not competing frameworks. Based on an epistemological analysis of the history of DSM5 and RDoC, some scientists predict that over the years, it might be possible that the RDoC framework replaces the DSM5 categorical approach (Aragona, Citation2014).

The RDoC framework

The NIMH RDoC framework is a new way of classifying mental disorders based on behavioral dimensions and neurobiological measures (Insel et al., Citation2010). The goal here is to link classifications of psychopathology to recent advances in genetics, neuroimaging, cognitive science and biomarkers (Cuthbert, Citation2014b; Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2013; Cuthbert & Kozak, Citation2013).

The central organizing principle surrounding the RDoC is that mental illnesses are viewed as biological and psychological disorders involving brain circuits that may change as a function of developmental stages and/or environmental factors. Consequently, the goal of RDoC is to define the basic dimensions of dysfunction that can cut across mental health disorders (for good examples of this approach, see Goodkind et al., Citation2015; Martins-de-Souza et al., Citation2012; Schwarz et al., Citation2012a,b). Contrary to the DSM5 that is a categorical (yes–no; presence versus absence of a disorder) system, the RDoC is a dimensional system that spans the range from normality to abnormality with continuous measures.

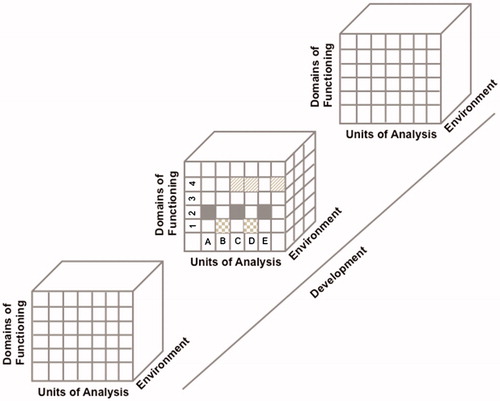

The RDoC framework comprises two main axes and two dimensions. First, there are the “domains of functioning” that are represented in the rows of a given matrix (see ). Five central domains of functioning have been laid out by the RDoC workgroups with the help of key experts in clinical and basic science (Cuthbert & Kozak, Citation2013). The domains of functioning and the constructs that they comprise have been selected on the basis of our current understanding of the neural circuitry of the brain. These five central domains are (1) Negative Valence Systems; (2) Positive Valence Systems; (3) Cognitive Systems; (4) Systems for Social Processes and (5) Arousal Systems. Expert workgroups have been gathered over the years to define these domains of functioning into subsystems (Cuthbert, Citation2014b; Cuthbert & Insel, Citation2013). For example, the Negative Valence Systems domain is comprised of five subsystems that are (a) acute threat or fear; (b) potential threat of anxiety; (c) sustained threat; (d) loss and (e) non-reward.

Figure 1. Schematization representation (from an original idea from Woody & Gibb, Citation2015) of the four dimensional matrix of the RDoC framework. Each row represents a subdomain of functioning that could be studied in different studies or in a single study. Each column represents a unit of analysis. The different matrices are represented as a function of the environmental and developmental dimensions. For example, the domain of functioning in figure could represent the “Negative Valence System” where “1” represents acute threat or fear, “2” represents potential threat of anxiety, “3” represents sustained threat and “4” represents loss. The units of analysis could be represented by “A” Genes; “B” Stress Hormones; “C” EEG; “D” Brain imaging and "E": Metabolic markers. Each row of this schematized RDoC matrix represents a particular study (e.g. the gray boxes in Row #1 could represent a study measuring acute threat of fear as a function of stress hormones and brain imaging in an adult population) and the results of various studies are represented in figure by the different filled boxes represented in rows and columns. Environmental and developmental factors could be added to all of these studies.

The other axis (the columns of the matrix in ) represents the “units of analysis”. These are the different classes of variables or measures that are used to study the domains of functioning. These units of analysis can include genes, molecules, cells, circuits, physiology, behavior and self-reports (Doherty & Owen, Citation2014). As presented in , a scientist interested at using the RDoC approach in a research project can select a dimensional construct from the five domains of functioning (e.g. cognitive systems), and within this domain choose a sub-domain (e.g. working memory) and study this construct using one or more units of analysis (e.g. genes, biomarkers and electrophysiology). This type of approach can be used across different diagnoses of mental disorders in order to delineate the unique and shared associations of units of analyses with the domain of functioning that is under study.

Two additional dimensions are added to the RDoC matrix. First, environmental aspects refer to how the environment interacts with the domains of functioning, and this is represented on the Y axis of the matrix. For example, exposure to various environmental stressors has been shown to be associated with depressive symptomatology (Doane et al., Citation2011; Hammen et al., Citation2009; Hori et al., Citation2014) and the influence of environmental stressors could be analyzed in association with a given domain of functioning (e.g. depressive symptoms) using various units of analysis (e.g. stress hormone levels (Claes, Citation2009; Munafo et al., Citation2009), genes (Clarke et al., Citation2010; Hudziak et al., Citation2000; Rende et al., Citation1999) and brain imaging (Krishnan et al., Citation1991; Sheline et al., Citation1996; Vythilingam et al., Citation2004)). Second, developmental aspects are represented as changes to the domains of functioning over time. For example, there appear to be important effects of exposure to early adversity on stress hormone levels (Heim et al., Citation2008; Lopez-Duran et al., Citation2009; Rao et al., Citation2010) and development of certain brain regions (Dannlowski et al., Citation2012; Lupien et al., Citation2011; Swartz et al., Citation2015; Whittle et al., Citation2011). These environmental and developmental influences can thus be added to the RDoC matrix to allow for a better understanding of the association between a given domain of functioning (e.g. depressive symptoms) on various units of analysis (stress hormones, genes and brain imaging) using an environmental (e.g. exposure to stress) and developmental (e.g. exposure to early adversity) framework.

presents a schematic representation of the four dimensions of the RDoC matrix that could emerge from various studies organized as a function of the RDoC domains of functioning and units of analysis as measured across development and in response to various environments.

It is important to note that RDoC is a translational mechanism that has been developed to study human disorders. However, scientists conducting animal work are typically using a dimensional approach whereby they work at linking various dimensions of behaviors to biological units of analysis. Although these scientists may not usually submit research proposals that fit with the RDoC framework described above, it is clear that any human study that also includes an animal protocol in a translational approach can be done using the RDoC framework (see the NIMH website for a clear description of the RDoC approach: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml).

Will the RDoC framework survive?

Many scientists have raised the issue that although it might be advantageous for the NIMH research agenda to no longer constraint scientists to build research projects around DSM5 diagnostic categories, it could be also disadvantageous for mental health research if NIMH imposes rigid and sole adherence to the RDoC framework. Three reasons have been raised on this issue.

First, although the five domains of functioning of the RDoC framework have been developed based on the wealth of data on the various units of analysis, some scientists fear that some areas of research that might have important implications for mental health research be left out of the RDoC Matrix (Doherty & Owen, Citation2014; Woody & Gibb, Citation2015). Consequently, the high focus on these particular domains of functioning of the RDoC matrix could divert funding away from other important mechanisms that could shed light on psychopathological processes underlying mental illness.

Second, it has been raised that the RDoC’s focus on neural circuits might undermine important research on psychological processes and mechanisms. Although this point has been criticized on the basis that many domains of functioning are of psychological nature (see Doherty & Owen, Citation2014), various scientists now discuss this important limitation of the RDoC framework in these terms. In an important paper published in 2014, Kirmayer and Crafa raised the point that the RDoC framework takes for granted that every human being will respond to a given environment with a similar biological response (Kirmayer & Crafa, Citation2014). However, many studies show that this is not the case and, as a function of cultural or personal factors, biological responses might greatly differ between individuals. For example, Weinberger and Goldberg (Citation2014) have reported that individuals suffering from different mental health disorders respond to the fMRI environment with different biological responses and a paper by Sindi et al. (Citation2013) showed that even normal elderly individuals react to a fMRI environment with a significant increase in stress hormones when compared to young individuals. These results show that psychological processes can modify biological responses and this effect can greatly differ between normal and pathological populations. Consequently, the point now raised by many scientists is that the units of analysis used in the RDoC approach represent different levels of biological complexity where molecules can change in concentration, genes and neuronal excitability can be regulated as a function of different conditions, and complex phenotypes can involve various polygenic actions. These rich interactions between psychology and physiology are not taken into account in the actual RDoC approach and consequently, a more dynamic approach to the various psychological and biological systems under study could lead to a better understanding of mental health disorders.

A third point relates to the different sample sizes that may be necessary to fill out the various boxes of the RDoC matrices. Although large epidemiological studies can identify associations between genotypes and phenotypes, in most cases, these associations have limited capacity to predict phenotype in individuals (for an excellent paper on this issue, see Khoury & Galea, Citation2016). Moreover, genetic and epidemiological studies necessitate very large sample sizes that are unable to be achieved by studies using brain imaging technologies. It is thus unclear how statistical power will be distributed into the various rows and columns of the RDoC matrices (see Doherty & Owen, Citation2014).

Clearly, the RDoC framework that has been developed in response to the shortcomings of our current classification systems of mental disorders is a long-term project that will take a few decades to be validated or invalidated. Based on the wealth of new data in the fields of genetics, brain imaging and psychology, it is clear that such a project will lead to important discoveries and a new culture of data sharing between scientists with the ultimate goal of developing new treatments for individuals suffering from mental illnesses.

However, as stated by Doherty and Owen in their excellent analysis of the RDoC framework (Doherty & Owen, Citation2014), these new developments will only be possible if the research community from around the world accepts these changes, not only by submitting grants aligned with the RDoC framework, but also by playing a significant role in peer reviews of grant applications written as a function of the RDoC framework. Basically, what this means is that although good research grants should still be accepted if they are based on DSM5 categories, no research grant should be refused if it is not built around these diagnostic categories but rather built around the RDoC framework.

Implications of the DSM5/RDoC debate for human stress research

Over the years, many scientists worked at developing biological markers to establish laboratory tests to diagnose psychiatric disorders. One of the most popular and well-studied area of biological markers has been the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Glucocorticoids, which are the end-product of HPA activation, are known to play an important role in the stress response and for many years, scientists and clinicians have recognized the important role of stressors at increasing vulnerability to mental disorders.

One of the first approach to the study of the effects of stress and stress hormones on the risk for psychopathologies was to measure levels of glucocorticoids in various psychiatric disorders. Here studies have shown that glucocorticoids are increased in depression (Barden, Citation2004; Charney & Manji, Citation2004; Gold et al., Citation2002), anxiety (Yoon & Joormann, Citation2012), schizophrenia (Berger et al., Citation2016), bipolar disorder (Belvederi Murri et al., Citation2016, although they are decreased in PTSD (Yehuda et al., Citation2005 #5143)), conduct disorders (Buydens-Branchey & Branchey, Citation2004; Pajer et al., Citation2001) and burnout (Pruessner et al., Citation1999). This high discrepancy of data has been related to various factors, ranging from publication bias (Carvalho et al., Citation2016), changes in glucocorticoid receptors' regulation (Yehuda et al., Citation2006) and adaptation mechanisms to chronic stress (Miller et al., Citation2007).

However, based on the DSM/RDoC debate, it is quite possible that this large discrepancy of data in biomarkers of stress be related to the weakness of the phenotypes (in terms of psychiatric diagnosis) that have been used in the past to assess activity of the HPA axis in various psychiatric disorders. If this is the case, then it would mean that HPA activity might be a better predictor of the presence of specific symptoms across various mental disorders, than a marker of any specific DSM-based psychiatric illness. A close analysis of the RDoC tables published by the various working groups (see https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/constructs/rdoc-matrix.shtml for a complete description) of the NIMH suggests that this could be the case.

presents the five research domains of the RDoC approach and their associated constructs and units of analysis. We have included in this table all the stress markers (genes, physiology, behavior and paradigms) that have been reported by NIMH to be associated with each research domain. The methodology we used to create is the following: we have looked at each research domain of NIMH, and for each unit of analysis, we have extracted the molecules, genes, physiological markers, etc. that relate to human stress research in order to offer a general and objective perspective of how human stress research can meet RDoC criteria. Given this methodology, the variability in terminology to describe similar constructs (e.g. cortisol versus glucocorticoids) in the various research domains of the RDoC matrix is based on the results of the various working groups that defined these research domains and units of analysis. Be this as it may, it was important for us to keep the same terminology as the one used by NIMH to guide the reader in the RDoC matrices as they relate to stress research.

Table 2. RDoC research dimensions and associated units of analysis.

From this table, one can see that stress markers are significantly associated with the research domain of “Negative Valence System”, “Social Processes” and “Arousal and Regulatory Systems”.

As an example, this table shows that for the research domain of “Negative Valence System”, stress markers such as basal and/or stress reactive levels of glucocorticoids, various genes associated with the stress responses (e.g. COMT, BDNF, etc.) and scores on various stress questionnaires could be better markers of “increased sensitivity to potential threat” across various DSM-based psychiatric disorders than markers of any given psychiatric disorder per se. Based on the RDoC approach, one could measure biomarkers of stress in a group of individuals suffering from various psychiatric disorders known to be sensitive to stressors and delineate subgroups of individuals based on low versus high reactivity to stress. In a second set of analysis, one could determine sensitivity to potential threat in low versus high stress reactors and show that increased sensitivity to threat is only present in those individuals with high reactivity to stressors. This result would suggest that increased reactivity to stressors can increase vulnerability to mental illness through the effects of stress hormones on the cognitive processes sustaining detection of threat. Such a result could help guide new forms of interventions that could be developed and applied across psychiatric diagnoses.

Although the RDoC approach has just recently been launched, various groups of scientists have started to publish papers showing the scientific benefits of this approach in the field of PTSD (Kaufman et al., Citation2015), panic (Hamm et al., Citation2016) and anxiety disorders (Lang et al., Citation2016).

Another impact of the RDoC approach for the field of stress research is that the RDoC approach calls for the inclusion of subthreshold, subsyndromal, partial or subclinical diagnosis populations for the search of associations between specific units of analysis and research domains. For example, and as recently discussed by Schmidt (Citation2015), a significant proportion of trauma-exposed individuals does not develop full PTSD but still present subthreshold levels of deficits in threat processing. Inclusion of individuals with subthreshold levels of pathology or even self-selected populations (e.g. individuals stating that they are suffering from anxious thoughts without being diagnosed with a full anxiety disorder) could add to the continuum of data linking specific research domains (e.g. “potential threat”) and various units of analysis. Clearly, the RDoC approach offers a robust and very rich approach to the study of mental health, and research on stress could greatly contribute at filling up the RDoC matrixes for the generation of the NIMH database on mental health.

Putting into action the NIMH RDoC approach: the signature bank

In 2010, the research center of the Institut Universitaire en Santé Mentale de Montréal (IUSMM) decided to undertake a shift toward twenty-first century research on human mental health. Based on the recommendations of an international advisory committee composed of some of the best scientists in the world in the field of mental health research, the research center developed the “Signature Project” that aims to systematically collect a vast bank (thereafter the “Signature Bank”) of biological and dimensional signatures from all clients of the IUSMM.

Over 4000 patients are admitted annually at the IUSMM, while an additional 2000 patients per year are treated by means of outpatient or ambulatory services. Our activities provide us with one of the largest populations of psychiatric patients in Canada. Having access to such a large pool of patients suffering from a range of mental disorders was described by our international advisory committee as being the key strength of our research center, upon which we should concentrate our research efforts.

What is unique about this ambitious mental health project is the extensive involvement of the hospital site in the attempt to establish an exclusive niche for discoveries in the signatures of mental health. By collaborating with the research center, hospital managers have contributed to the implementation of this large-scale project that aims at measuring the biological, psychological and social signatures of people who suffer from mental disorders, who use the hospital’s clinical services, and who consent to taking part in this research initiative, which brings together clinicians, patients and researchers.

For all hospital clients who agree to participate, blood specimens are collected for the purpose of measuring metabolic, genetic, toxic and infectious biomarkers, while saliva samples are collected to measure sex hormones and hair samples are collected to measure stress hormones. provides a detailed description of the different types of biomarkers that are analyzed as part of the Signature project and the different biospecimens and concentrations collected.

Table 3. Description of the different types of biomarkers analyzed as part of the Signature Project.

All biospecimens (blood, saliva and hair) are obtained by three trained research nurses in the early morning after an overnight fasting period. The biospecimens are processed upon their arrival at the Signature laboratory according to standard methods for each biomarker (a detailed description of this methodology can be obtained upon request to the Signature team). In order to maintain the integrity of biospecimens during blood fractionation, tubes waiting to be processed are kept in a cold room at 4 °C.

Clients also fill out psychological and social self-report questionnaires enabling assessment of some of the constructs and subconstructs of the various research domains of the RDoC approach. Assessment of these dimensional aspects of mental health can then be linked to the various units of analyses (genes, molecules and physiology) in order to better understand human vulnerability to certain mental disorders. presents the list of self-report measures that enables measurement of various dimensions, constructs and/or subconstructs of the RDoC approach that can be administered within the 45- to 60-min timeframe.

Table 4. Self-report measured used to assess dimensions of mental health in the Signature Project as a function of RDoC constructs.

All categorical information related to a psychiatric diagnosis is taken from the medical file and is accompanied by information about the medication prescribed. In order to obtain information about other chronic disorders and medications taken in the last 2 years by each patient, we leverage on the benefits of the Canadian health care system, which enables us to access these data from the centralized medical data that is archived by the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ).

With the goal of promoting patient involvement in the Signature project, a customized iPad application was developed that enables participating clients to fill the questionnaires measuring the dimensional aspects of their illness. In keeping with the new clinical research methodologies implemented by the NIMH, and in order to ensure the confidentiality of information, all data related to the Signature project are obtained, transferred and processed by means of information technology (IT) tools.

Once a participant has finished filling out the questionnaires, the attending psychiatrist may immediately consult the questionnaires’ total score using his or her personal iPad. A hard copy of this report is also placed in the participant’s medical file, so that the rest of the authorized clinical team may access it. This computerized report includes an official document stating that these are research data that cannot be used for diagnostic purposes.

A pilot study conducted in 2010 with 120 patients admitted to the hospital’s psychiatric emergency ward and inpatient and outpatient clinics of the IUSMM showed that over 85% of patients were in favor of the project using the iPad and that over 87% reported highly positive experiences with completing the questionnaires by means of this technological tool. No clients reported being frustrated with using the technology, and 95% reported that they had no problem with this methodology (Pelletier et al., Citation2013). To this day, we have tested over 1000 patients at our psychiatric emergency service, hospitalization services and in outside clinics, and we do not report any problems with the use of these new technological tools to measure dimensions of mental health.

As the term itself suggests, a mental illness “signature” implies that different people suffering from the same mental disorder may present different biological, psychological and/or social signatures. However, a single individual may also present different signatures at different stages of the illness’s evolution. Therefore, in order to better understand the signatures of mental illnesses, it is vital to capture the signature of a mental disorder at different points of an individual’s clinical development. In light of this objective, we have implemented a longitudinal arm to the Signature Project in which the biological, psychological and social signatures are obtained at four different points in the clinical visit of patients at the IUSMM: (1) when clients are admitted to the psychiatric emergency services of IUSMM, (2) when they are discharged from the hospital, (3) when they are admitted to one of our outpatient clinics and (4) 12 months later or at the end of outpatient treatment. By means of this longitudinal methodology, it will be possible to better understand changes in biological and/or psychological and/or social signatures associated with the psychiatric crisis (time 1), acute response to treatment (time 2), success (or not) of long term treatment (time 3) and recovery (time 4).

The Signature Project started on November 2012 and at the time of submission of this perspective paper, the Signature bank is composed of 924 patients, 536 (42%) men and 388 (58%) women, recruited at time 1, i.e. the psychiatric emergency unit of the IUSMM. The consent rate is 64%. Patients are aged 18–81 years (mean = 40.4, SD = 14.2).

The first analysis we performed on the Signature Bank was to determine the psychometric properties of the self-report measures in order to ensure that they are in line with the published literature. As can been seen in , the Cronbach alpha obtained on the self-report measures are very close to the original Cronbach published in the literature for each questionnaire. This validates the utilization of these self-report measures and goes along with the results of the NIMH PROMIS system (Cella et al., Citation2007).

Table 5. Psychometric properties of the Signature bank project.

describes the major diagnostic categories according to the primary diagnosis given by the psychiatrist when the patient was treated at the Psychiatric Emergency Service of the IUSMM. Diagnoses are coded according to ICD-10 (WHO) classification. We can see from that consistent with the literature (Beauchaine & McNulty, Citation2013), there are a lot of comorbidities and some patients can have up to four diagnoses. shows the frequencies and percentage of comorbidities across diagnoses. One can see in that high comorbidity exists between mood disorder and substance use disorder (32.3%), between personality disorder and substance use disorder (30.1%) and between personality disorder and anxious disorder (26.6%).

Table 6. ICD-10 categories of the primary emergency diagnostic (N = 899).

Table 7. ICD-10 categories of the comorbid disorders (N = 899).

One of the main critic of the PROMIS approach developed by NIMH was that it is not clear whether self-report measures obtained by individuals with various mental illness can be reliable across time. In order to assess the test–retest validity of self-report measures in this population of psychiatric patients seen at the emergency, we present data from the Childhood Experience of Violence Questionnaire (CEVQ). The CEVQ is a questionnaire taken from the Statistics Canada – Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS; Canada, Citation2008). It is composed of seven questions; one question asked if the patient witnessed violence in the household as a child, two questions asked the patient if he/she had been victim of physical abuse, two questions asked the patient if he/she had been victim of sexual abuse. The last question asked if the patient was ever reported to the child protection services. Three scores are derived from this questionnaire: child abuse, physical abuse and sexual abuse. If patients seen at the psychiatric emergency services are not reliable for assessment of various self-report measures, then one would predict high variability in scores on the CEVQ questionnaires, even if the events should show stability across measurements.

A subset of 315 participants was tested at time 2 and/or time 3 and/or time 4 of the project. Each participant answered the CEVQ at each visit. To assess the test–retest validity of the instrument and since all events in the questionnaires refers to the childhood period, the agreement rate was analyzed across time. presents the percent of agreement from one time to another and a linearly weighted kappa. We see that the level of agreement is around 60% (50–70%) for most items, and a kappa around .60 that represents a modest to good agreement. The agreements are higher amongst the last two items that measure sexual abuse. Most disagreements occur across levels of severity. For instance, if we compare the agreement of the abuse indicator between time 1 and time 2, the percentage of agreement goes from 65.5% to 81.6%. The kappa stays at .6 because the weighted kappa used in the previous analyses adjust the kappa proportional with the disagreement level. This results confirms reports from the PROMIS groups of NIMH (Cella et al., Citation2007) showing the reliability of using self-report measures, even when individuals are seen at the psychiatric emergency services.

Table 8. CEVQ agreement across time.

Discussion

On 28 July 2016, Dr. Joshua A. Gordon, MD, Ph.D., was named new director of the NIMH, a year after Dr. Insel left NIMH to join Google’s life sciences team. When asked by a magazine whether he planned to pursue the RDoC approach for the NIMH, Dr. Gordon stated that he wants to learn more on the RDoC approach before deciding where to go with this approach for the NIMH. Clearly, with all the work that has been done on the RDoC framework to this day by the various NIMH teams, one can predict that it will continue to emerge as a new way of performing psychiatric research. However, as many clinical researchers have stated in various blog entries, it will also be important for Dr. Gordon to understand the importance of the categorical DSM approach to study patients as a function of their personality, culture, life experiences, etc. Consequently, many scientists and clinicians now hope that both approaches will continue to develop in order to provide the best of treatment and research for people suffering from mental health disorders.

In this paper, we have presented the historical background surrounding the DSM-5 and RDoC approaches to mental health research and how the RDoC approach can be used by scientists working in stress research. Thereafter, we have presented the Signature Bank of the IUSMM that aims at measuring the biological, psychological and social signatures of mental health using both a categorical (DSM-5) and dimensional (RDoC) approach to mental health research. The Signature Bank is thus a good example of a research project that was built around the debate between the DSM5/RDoC approach. For a small access fee that ensures survival of the Project, access to the Signature Bank is open to any scientist in the world who wishes to analyze data using a DSM5 and/or RDoC approach (access by: http://www.iusmm.ca/research/signature-bank.html).

Although the Signature Project is unique in the world and will certainly provide very interesting and important results, there are a few limitations of the project that have to be discussed. First, the Signature Project does not contain the entire set of research domains as developed by the NIMH RDoC approach. The main reason for this is that the Signature Project was developed at the same time as the RDoC and DSM5 dimensional approaches were being developed in the U.S. (i.e. between 2009 and 2012) and the Signature Consortium had to take important decisions as with the best dimensions to be studied while at the same time providing important clinical information for health professionals caring for patients of the IUSMM. However, the Signature Bank can easily provide scientists with dimensional factors that cut across the different diagnostic groups and that have been shown in various studies to be significantly associated with various mental health disorders. Based on the data that will be obtained from analyses of the Signature Bank and other RDoC databases in upcoming years, scientists all across the world will be able to determine what are the best additional research domains to include in our future signatures of mental illness and our team will be able to modify the Signature Project accordingly.

Another limitation of the Signature Bank is that we have not included a control group in the original project. This was mainly due to a lack of funding, given the high costs associated with the development and initiation of the Signature Project. However, we have recently launched a Phase 2 to the project and are now testing a control group paired to the individuals of the Signature Bank on age, education and income.

A third limitation of the Signature Bank is the lack of data in children. Here again, this limitation was induced by a lack of funding at the time of development of the study, and discussions are actually underway with research centers from children’s psychiatric hospitals in order to develop a Signature Project for children. Members of the Signature teams also discuss the possibility of testing the children of the patients tested in the Signature Project as these data could provide very important information on genetic and epigenetic vulnerability to mental illness.

Finally, as summarized in this perspective paper, the shift from categories to dimensions made at the NIMH was heavily oriented toward understanding the process by which mental health disorders can emerge and/or persist and/or resist to treatment. Yet, the basic notion of a “Signature of mental illness” is quite static and, although the concept of “Signature of mental illness” was mainly developed in the 2008 Strategic Plan of NIMH to refer to the importance of personalized medicine, it is important to note here that the Signature project described in this paper is only one way that one can use the RDoC approach to analyze biological and psychological data from people suffering from mental illness. Clearly, the approach taken by our team is not likely to be the method used by many scientists across the world to write RDoC proposals for NIMH and/or analyze data from various databases to better understand mental illnesses. However, what might be common across all these approaches and/or analyses is the transnosological vision that can provide rich information on the mechanisms underlying mental disorders in humans.

Although the Signature Project presents the limitations presented above, it is still the only project in the world assessing the biological, psychological and social signatures of mental illness using a longitudinal approach based on the DSM5 and RDoC dimensional approach. As the world’s only longitudinal mental health biomonitoring project, the Signature Bank thus has the potential to revolutionize the field of mental health research so that, in the words of the NIMH’s strategic plan, “breakthroughs in science can become breakthroughs for all people with mental illnesses.”

Acknowledgements

The Signature Project and its associated Signature Bank are supported by a donation from Bell Canada Enterprises to the Foundation of the IUSMM and by an infrastructure research center grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQ-S). The work of SJL is supported by a Foundation Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The Research Center of the IUSMM is supported by an infrastructure grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQ-S).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombardier C, Bombardier S, et al. (2008). Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 67:1360–4.

- Andrews G, Slade T, Issakidis C. (2002). Deconstructing current comorbidity: data from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Br J Psychiatry 181:306–14.

- Aragona M. (2014). Epistemological reflections about the crisis of the DSM-5 and the revolutionary potential of the RDoC project. Dial Phil Ment Neurosci 7:11–20.

- Barden N. (2004). Implication of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in the physiopathology of depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci 29:185–93.

- Beauchaine TP, McNulty T. (2013). Comorbidities and continuities as ontogenic processes: toward a developmental spectrum model of externalizing psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 25:1505–28.

- Belvederi Murri M, Prestia D, Mondelli V, Pariante C, Patti S, Olivieri B, Arzani C, et al. (2016). The HPA axis in bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63:327–42.

- Berger M, Kraeuter AK, Romanik D, Malouf P, Amminger GP, Sarnyai Z. (2016). Cortisol awakening response in patients with psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 68:157–66.

- Bjelland I, Lie SA, Dahl AA, Mykletun A, Stordal E, Kraemer HC. (2009). A dimensional versus a categorical approach to diagnosis: anxiety and depression in the HUNT 2 study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 18:128–37.

- Buydens-Branchey L, Branchey M. (2004). Cocaine addicts with conduct disorder are typified by decreased cortisol responsivity and high plasma levels of DHEA-S. Neuropsychobiology 50:161–6.

- Canada S. (2008). Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes: composante annuelle. Ottawa: Statistiques Canada.

- Carvalho AF, Kohler CA, Brunoni AR, Miskowiak KW, Herrmann N, Lanctot KL, Hyphantis TN, et al. (2016). Bias in peripheral depression biomarkers. Psychother Psychosom 85:81–90.

- Casey BJ, Craddock N, Cuthbert BN, Hyman SE, Lee FS, Ressler KJ. (2013). DSM-5 and RDoC: progress in psychiatry research? Nat Rev Neurosci 14:810–4.

- Cassano GB, Dell'Osso L, Frank E, Miniati M, Fagiolini A, Shear K, Maser J. (1999). The bipolar spectrum: a clinical reality in search of diagnostic criteria and an assessment methodology. J Affect Disord 54:319–28.

- Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, et al. (2007). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 45:S3–S11.

- Charney DS, Manji HK. (2004). Life stress, genes, and depression: multiple pathways lead to increased risk and new opportunities for intervention. Sci STKE 2004:re5.

- Cicchetti D, Blender JA. (2006). A multiple-levels-of-analysis perspective on resilience: implications for the developing brain, neural plasticity, and preventive interventions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1094:248–58.

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. (2002). A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol 70:6–20.

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. (2009). The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: the coming of age of a discipline. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:16–25.

- Claes S. (2009). Glucocorticoid receptor polymorphisms in major depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1179:216–28.

- Clarke DE, Narrow WE, Regier DA, Kuramoto SJ, Kupfer DJ, Kuhl EA, Greiner L, Kraemer HC. (2013). DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part I: study design, sampling strategy, implementation, and analytic approaches. Am J Psychiatry 170:43–58.

- Clarke H, Flint J, Attwood AS, Munafo MR. (2010). Association of the 5-HTTLPR genotype and unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 40:1767–78.

- Cook KF, Bamer AM, Amtmann D, Molton IR, Jensen MP. (2012). Six patient-reported outcome measurement information system short form measures have negligible age- or diagnosis-related differential item functioning in individuals with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93:1289–91.

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. (2010). Toward new approaches to psychotic disorders: the NIMH Research Domain Criteria project. Schizophr Bull 36:1061–2.

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med 11:126.

- Cuthbert BN, Kozak MJ. (2013). Constructing constructs for psychopathology: the NIMH research domain criteria. J Abnorm Psychol 122:928–37.

- Cuthbert BN. (2014a). The RDoC framework: facilitating transition from ICD/DSM to dimensional approaches that integrate neuroscience and psychopathology. World Psychiatry 13:28–35.

- Cuthbert BN. (2014b). Research domain criteria: toward future psychiatric nosology. Asian J Psychiatry 7:4–5.

- Dannlowski U, Stuhrmann A, Beutelmann V, Zwanzger P, Lenzen T, Grotegerd D, Domschke K, et al. (2012). Limbic scars: long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment revealed by functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Psychiatry 71:286–93.