Abstract

This cross-sectional study was designed to determine what role race plays in the relationship between obesity and child maltreatment (CM), which is currently unknown. One hundred fifteen participants successfully completed the study, including Whites (n = 60) and Blacks (n = 55) of both sexes. CM was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Total fat, trunk/total fat ratio, visceral adipose tissue (VAT), and VAT/trunk ratio, were measured through Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) and Corescan software estimation. A significant interaction between identifying as White and having a history of CM was found to predict body mass index (BMI) (β = 5.02, p = .025), total fat (kg) (β = 9.81, p = .036), and VAT (kg) (β = 0.542, p = .025), whereas race by itself was an insignificant predictor. An interaction between having history of physical abuse and identifying as White was found to predict BMI (β = 6.993, p = .003), total fat (β = 12.683, p = .010), and VAT (β = 0.591, p = .018). An interaction between having multiple CM subtypes and identifying as White predicts increased total fat (β = 5.667, p = .034) and VAT (β = 0.335, p = .014). Our findings indicate that the relationship between CM and obesity, measured through BMI, total body fat, and VAT, is seen in Whites but not in Blacks. Future research should investigate the nature of this racial influence to guide obesity prevention and target at-risk populations.

Introduction

Obesity has reached epidemic levels globally with high morbidity and mortality (Ng et al., Citation2014). Over the last three decades, obesity prevalence in the U.S. has gradually increased; current prevalence in adults is 37.7%, with variations between regions and ethnic populations (Flegal, Kruszon-Moran, Carroll, Fryar, & Ogden, Citation2016; Hruby & Hu, Citation2015). Obesity is known to increase the risk for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, some cancers, and depression (Hruby et al., Citation2016). Understanding factors that contribute to obesity risk may provide pathways for prevention and treatment that can decrease illness and death.

Obesity results from an excess in energy intake/storage or a deficit in energy expenditure, and many environmental and hereditary risk factors such as physical inactivity, diet, age, sex, and genetics influence metabolic mechanisms to affect risk of obesity (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2017). In addition, a history of child maltreatment (CM) is associated with obesity and increased visceral adipose tissue (VAT), independent of other risk factors (Danese & Tan, Citation2014; Li, Chassan, Bruer, Gower, & Shelton, Citation2015; Shin & Miller, Citation2012; Williamson, Thompson, Anda, Dietz, & Felitti, Citation2002).

CM can be categorized by abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual) or neglect (physical and emotional) (Bernstein et al., Citation2003). There are approximately 3.3 million reports of child abuse or neglect to Child Protective Services in the U.S. per year (43.8 in 1000 children) (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, Citation2017). This likely underestimates the true prevalence of CM due to underreporting. Studies estimate that as many as 1 in 5 children experience CM in their lifetimes (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, Citation2012). Males and females experience approximately the same rates of CM; however, Blacks have 1.5–2 times higher rates of maltreatment compared to Whites (Child Trends, Citation2019). CM has adverse effects on health, including both mental health disorders and chronic medical illness (Burke, Finn, McGuire, & Roche, Citation2017; Casement, Shaw, Sitnick, Musselman, & Forbes, Citation2015). Depression, associated with both CM and obesity, varies among races; Blacks have a lower prevalence compared to Whites (Williams et al., Citation2007).

There are significant differences in VAT, body mass index (BMI), and waist-to-hip ratio between Blacks and Whites (Demerath, Citation2010; Katzmarzyk et al., Citation2010). However, no studies have taken into account the possible role of race in the association of CM with obesity, only examining links between CM and a heterogeneous population. Therefore, it remains unclear what role race plays in the relationship between CM and obesity.

There have been few studies demonstrating that different types of abuse and neglect confer different levels of risk for adverse health outcomes (Infurna et al., Citation2016; Norman et al., Citation2012; Petrenko, Friend, Garrido, Taussig, & Culhane, Citation2012; Trickett, Negriff, Ji, & Peckins, Citation2011). Risk for obesity may vary by CM subtype (Grilo & Masheb, Citation2001; Schneiderman, Negriff, Peckins, Mennen, & Trickett, Citation2015), however prior studies have focused on BMI measurements only. We previously found that physical abuse was most correlated with visceral obesity (Li et al., Citation2015). Many children experience multiple subtypes (Herrenkohl & Herrenkohl, Citation2009), which is associated with worse health outcomes (Walker, Gelfand, et al., Citation1999), but it is unknown what effect multiple subtypes of CM may have on fat distribution. One study has found combined occurrence of two subtypes increases risk for obesity measured by BMI, with variations across ethnicity and sex (Richardson, Dietz, & Gordon-Larsen, Citation2014). There are limited data on the relationship between different CM subtype or combined subtypes on VAT and trunk fat distribution, as well as the effects of race on this relationship.

The primary objective of this cross-sectional study was to investigate if the relationship between CM and obesity is influenced by race. A secondary objective was to investigate if different CM subtypes or the number of CM subtypes increases risk for visceral and trunk related obesity in a race-specific manner.

Methods

Participants

The University of Alabama at Birmingham’s (UAB) Institutional Review Board for Human Use approved the study prior to enrollment and data collection and all participants provided both oral and written informed consent. Participants were recruited from local communities in Alabama, including UAB Medical Center and UAB campus. Participants included White and Black females and males between the ages of 19–65. Exclusion criteria included autoimmune, endocrine, inflammatory, or neurological disorders; history of bipolar disorder, psychosis, or drug or alcohol use disorder within one year; uncontrolled hypertension; diabetes or other metabolic disorder; being pregnant or lactating; or taking corticosteroids, antibiotics, or anti-inflammatory medications within 30 days of the first study visit. Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) diagnosis was determined using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., Citation1998). Demographic information, including race, and medical history were also obtained by self-report. Out of the 157 participants screened, 115 completed the study and were included in data analysis.

Assessment of CM

CM was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) (Bernstein et al., Citation2003). The CTQ-SF measures five subtypes of maltreatment using five questions for each. The subscales are physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Each question contains a statement about childhood experience and is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from never true to very often true. These numbers are then added up for the subtype score, which could range between 5 to 25. Total CM score combines all five subtype scores and could range between 25 to 125.

The CTQ-SF has been shown to be reliable and valid compared to clinician and therapist interview ratings in diverse populations, as well as internal consistency within subscales (Chronbach α for physical abuse = 0.81–0.86, emotional abuse = 0.84–0.89, sexual abuse = 0.92–0.95, physical neglect = 0.61–0.78, and emotional abuse = 0.85–0.91) (Bernstein et al., Citation2003). Moderate to severe CM history was defined by any of the following standard criteria: scoring an 8 or above for physical neglect, sexual abuse, or physical abuse, scoring a 10 or above for emotional abuse, scoring a 15 or above for emotional neglect or scoring a 35 or above for total CM score. These thresholds were previously calculated to have high sensitivity and specificity to independent clinician assessment (Walker, Gelfand, et al., Citation1999; Walker, Unutzer, et al., Citation1999). CM and non-CM groups were created using these validated cutoffs. Because of the distribution, a multiple CM subtype variable was created by counting the number of subtypes scored past these thresholds, and creating groups with zero subtypes past threshold, having one subtype reach threshold, and having two or more subtypes reach threshold. Total CM severity refers to the total questionnaire score.

Body composition measurements

Anthropometric measurements (height, weight, waist circumference, and hip circumference) were recorded and used to calculate BMI and waist-to-hip ratio. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Lunar iDXA, GE-Healthcare Madison, WI) scans were done using a total body scanner in order to receive fat distribution measurements such as total fat and trunk fat. Participants were required to wear lightweight clothes, remove all metal objects from their bodies, and lie supine during the scan. CoreScan software was used to estimate the amount of VAT based on abdominal area and subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are shown as means ± standard deviation or count (%). Statistical significance was defined at an alpha level of ˂0.05. Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s test and Levene’s test of equality of error variances were used to determine normality and homogeneity respectively. Chi-square tests were used for categorical demographic data, and independent t tests were used for continuous demographic data.

Linear regression analysis was used to determine the interaction effects of CM and race on BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, total fat, trunk/total fat ratio, and VAT. Variables entered into the model included race, CM, race*CM, age, sex, education, smoking, employment, and MDD. CM = 1 indicates history of CM and race = 1 indicates identifying as White.

Similar linear regression models were conducted for BMI, total fat, and VAT outcomes to test effects of CM subtypes, total CM severity, and having experienced multiple CM subtypes. For the five CM subtypes, each subtype was analyzed using a separate model, which included the subtype, race, subtype and race interaction term, as well as all covariates. For CM severity, the total CTQ-SF score was analyzed within a model with an interaction term created was between it and race. Finally, the effect of having experienced multiple subtypes of CM was tested by analyzing an ordinal variable that divided participants into groups based on having zero, one or two and more subtypes that reached the subtype threshold values mentioned previously. All other covariates such as age, sex, education, smoking, employment, and MDD were also included in every model.

Results

Participant characteristics

Characteristics of the participants fat measurements are listed in . There were no differences between Whites and Blacks in age, sex, education level, employment status, smoking status, MDD, or total CM and CM subscale scores. However, Blacks had greater BMI but lower trunk/total fat ratio compared to Whites. Total CM and CM subscale scores for each group are listed in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Table 2. CM characteristics.

CM*race interaction on body/fat measurements

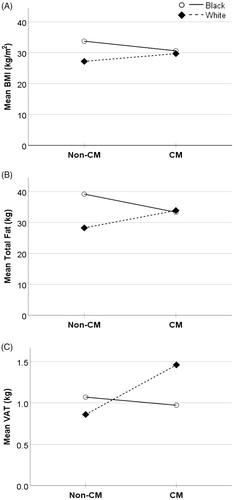

Interaction of CM and race on fat measurements was tested using the full model, which includes all covariates, and results are shown in as unstandardized coefficients (β). For BMI, total fat, and VAT, the interaction of CM and race was significant (βCM*race), which indicates that having maltreatment and being White predicted a higher level of obesity. The coefficients for the interaction term were 5.02 (p = .025) for BMI, 9.81 (p = .036) for total fat (kg), and 0.542 (p = .025) for VAT (kg). Race and CM interaction was not significant in predicting waist-to-hip ratio, trunk/total fat ratio, and VAT/trunk ratio. βrace was significant in BMI (β = –6.17, p = .001) and total fat (β = –9.51, p = .01) as well, but not significant for VAT. β CM itself was not significant for any outcomes, indicating that CM by itself did not predict any fat measurements. Interaction effects can be seen in for BMI, total fat, and VAT.

Figure 1. Interaction plots for body mass index (BMI), Total Fat, and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) by child maltreatment (CM) and race. Significant interactions between race and CM are shown for (A) BMI, (B) total fat, and (C) VAT. Interactions predict higher BMI (p = .025), total fat (p = .036), and VAT (p = .025) for Whites who have history of CM. BMI, body mass index; VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

Table 3. Predictors for body/fat distribution measurements.

CM subtype effects on adipose tissue

Secondary analysis included testing interaction of having a subtype (physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse) with race while controlling for all aforementioned covariates. Tests for multicollinearity were conducted for each full model and indicated that even with inclusion of the interaction term, multicollinearity did not bias the results (variance inflation factor for physical neglect = 2.19, physical abuse = 2.46, emotional neglect = 2.47, emotional abuse = 2.67, sexual abuse 3.12). Results shown in indicate significant physical abuse and race interaction for BMI (β = 6.993, p = .003), total fat (β = 12.683, p = .010), and VAT (β = 0.591, p = .018); this indicates an increase in these three outcomes when comparing Whites with history of physical abuse against Blacks with history of physical abuse. There were no other statistically significant interaction terms for other subtypes.

Table 4. Regression analysis of race*subtype interaction.

Severity of CM and multiple CM subtype effects on adipose tissue

Secondary analysis also tested interaction of race and severity measures (total CM score and multiple subtypes) while controlling for all aforementioned covariates. The results shown in show a significant interaction between race and having multiple subtypes that can predict total fat (β = 5.667, p = .034) and VAT (β = 0.335, p = .014). While not statistically significant, results included β race*multiple CM = 2.460 for BMI (p = .056), which may suggest a possible interaction that warrants further testing. Interactions between race and the total CM score did not significantly predict BMI, total fat, or VAT.

Table 5. Regression analysis of race*CM severity interaction.

Discussion

In this current cross-sectional study, the role of race on the association between CM and its subtypes and several obesity measures, including VAT, was examined. The primary findings are that the association between CM and obesity and the association between CM and visceral obesity may be found in Whites but not Blacks, indicative of an interaction between race and CM. This interaction was found to predict increased BMI, total fat, and VAT in Whites with CM compared to Blacks with CM. An interaction between being White and having history of physical abuse, as well as having multiple CM subtypes, was also found to predict higher BMI, total fat, and VAT.

VAT is especially important because it is a strong and specific predictive risk factor for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, some types of cancers, and diabetes (Després, Citation2001; Pi-Sunyer, Citation2004; Wajchenberg, Citation2000). Our data indicate that while there is a significant increase in visceral fat associated with CM, it should be considered in the context of the race and CM interaction. The significant positive βCM*race interaction term indicates an increase in VAT when comparing Whites and Blacks with CM. This trend is consistent with prior literature showing history of CM increases the risk of visceral obesity in general populations (Danese & Tan, Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2015; Shin & Miller, Citation2012; Williamson et al., Citation2002), but it indicates that this may be specific to Whites. The lack of significance of the βCM term indicates that there is no significant difference in VAT between CM and non-CM groups when all other variables including race are held constant. βrace was not significant for VAT, meaning there was no significant difference between Whites and Blacks when keeping all other variables constant, which contrasts with current literature that states Blacks have less VAT than Whites. However, this βrace term does control for CM, which may hide the effects of race on VAT, thus further supporting the importance of considering CM and race as an interaction when comparing VAT between races. These results support the idea that the pathway from CM to visceral obesity may be moderated by race and is seen in Whites but not Blacks.

In addition, our results indicate a significant CM and race interaction predicting BMI and total fat. This is consistent with the literature that CM is associated with higher BMI and total fat (Danese & Tan, Citation2014). Interpreted similarly with the VAT results, βCM is insignificant in predicting BMI and total fat, indicating the importance of the interaction itself in predicting increased fat. In a meta-analysis, studies with more White participants showed a stronger association between CM and obesity measured by BMI or waist-to-hip ratio, which may indicate a trend of the interaction that our study has observed (Danese & Tan, Citation2014).

Secondary analysis supported an interaction between being White and having a history specifically of physical abuse that significantly predicted higher BMI, total fat, and VAT. Physical abuse is associated with adverse health outcomes, including obesity (Springer, Sheridan, Kuo, & Carnes, Citation2007). Our results indicate that this association may only be significant when looking at the interaction, i.e. physical abuse is associated with obesity for those who are White and have a history of physical abuse, but this association may not be present for those who are not White and have history of physical abuse. Prior research showed an association of sexual abuse and obesity, but our study did not find such an association (Gustafson & Sarwer, Citation2004). The non-significant results may be due to the small proportion of participants reporting a history of sexual abuse, which may have obscured an association.

There are several studies that indicate a positive dose-response relationship between having a history of multiple types of abuse and worse health outcomes, including obesity (Felitti et al., Citation1998; Williamson et al., Citation2002). Consistently, this study found an association between having more than one CM subtypes and higher BMI, as well as greater amounts of total fat and VAT. Thus, having more than one type of maltreatment may be associated with higher risk for obesity and a greater amount of VAT.

The exact mechanisms underlying the race-specificity of fat disposition and CM are currently unknown. One such pathway of interest may be the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which has been shown to be dysregulated by CM (Li et al., Citation2015; Tarullo & Gunnar, Citation2006). Reduced availability of cortisol, shown in our previous study through blunted cortisol awakening response, may work with increased immune system activation to lead to increase visceral fat mass in subjects with a history of CM. Insulin resistance, for which CM is a risk factor for (Li, Garvey, & Gower, Citation2017), can increase risk for further weight gain and VAT as well (Scott, Melhorn, & Sakai, Citation2012). There is also evidence that CM can be a risk factor for lower socioeconomic well-being as an adult even when controlling for preexisting differences (Currie & Widom, Citation2010). While the current study controlled for factors such as education and employment, the potential for mediation or interaction of socioeconomic factors with race or CM were not investigated. Other possible mechanisms that have been associated with increased risk for obesity and/or maltreatment or chronic stress include food insecurity (Cohen, Barron, & Moore, Citation2018; Dhurandhar, Citation2016), eating behavior (Ford et al., Citation2016; Torres & Nowson, Citation2007), or different types of coping mechanisms utilized (Sesar, Simic, & Barisic, Citation2010). In one study, binge eating was associated with different predictors and Caucasian women exhibited more severe binge eating symptomology (Napolitano & Himes, Citation2011). In another study, depression, which is more common in Whites (Williams et al., Citation2007), was found to mediate the relationship between CM and BMI, but only with physical abuse (Sacks et al., Citation2017). While we did not examine the three-way effects of MDD, race, and maltreatment, future studies may investigate it. Not much research has looked at many of these mechanisms in relation to specifically CM-related stress however, and very little investigating race effects while considering CM and obesity. Although multiple explanations, including physiology, behavior and environment may contribute, the pathways from CM to obesity may be complicated, especially when considering documented racial differences in obesity and fat deposition (Cossrow & Falkner, Citation2004), warranting more studies in this field. Furthermore, the observation that the pathway from CM to obesity may be influenced by race has implications for future research on mechanisms that could be targets for intervention in specific racial groups. Specifically, investigating the association of CM and obesity in Whites and Blacks separately may lead to improved obesity prevention or treatment if race-specific CM mechanisms are elucidated. Clinical practice may be informed by these findings; history of CM can be another risk factor of obesity in addition to other previously documented adverse health effects, aiding preventative efforts in a personalized way by race.

This study’s strength includes using DXA-derived fat measurements and investigating race interactions, which better determines the different trends present. However, there are some limitations. This study was a cross-sectional study, and it should not be used to determine causality between CM and obesity or fat distribution. Longitudinal studies can better determine the causal effect between CM and obesity or fat distribution. This study had a relatively small sample size and larger samples may be needed to verify the findings. The CTQ-SF is a retrospective measure, and while it is well-validated, it is still subject to some recall bias. While we look at race differences, there is an overlap of biological race and socially constructed race self-reports. This study may provide insight on the effects of a race as defined by a social construct more than solely strict biological racial differences, since we did not do racial genetic profiling. Future studies using appropriate genetic analysis by race could lead to different effects. Investigating physiological mechanisms, environmental based mechanisms, and health behaviors may also provide insight as to why CM increasing risk for obesity is different among races.

Conclusion

Our study adds to the current understanding between obesity and CM, including subtypes and overall severity, by examining race interactions. To our knowledge, data on these measurements, including VAT, has not been collected and analyzed in the context of a CM and race interaction. Future research should account for the effects of race when investigating pathways and mechanisms between CM and obesity. Understanding the effects of race on CM-related obesity may lead to tailored interventions that target behavioral or physiological mechanisms that are effective at preventing CM and CM-related obesity for populations most at risk.

A.Y.C. performed the study, collected the data, analyzed the data, drafted, edited and approved the final manuscript. Y.L. performed the study, collected the data, and edited and approved the final manuscript. B.A.G. and R.C.S. designed the study and edited and approved the final manuscript. L.L. designed and performed the study, collected the data, and edited and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the research participants for their time and effort in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bernstein, D.P., Stein, J.A., Newcomb, M.D., Walker, E.A., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., … Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 169–190. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Burke, N.N., Finn, D.P., McGuire, B.E., & Roche, M. (2017). Psychological stress in early life as a predisposing factor for the development of chronic pain: Clinical and preclinical evidence and neurobiological mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95, 1257–1270. doi:10.1002/jnr.23802

- Casement, M.D., Shaw, D.S., Sitnick, S.L., Musselman, S.C., & Forbes, E.E. (2015). Life stress in adolescence predicts early adult reward-related brain function and alcohol dependence. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10, 416–423. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu061

- Child Trends. (2019) Child Maltreatment. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=child-maltreatment

- Cohen, R.S., Barron, C.E., & Moore, J.L. (2018). Food insecurity and child maltreatment: A quality improvement project. [Article]. Rhode Island Medical Journal, 101, 31–34.

- Cossrow, N., & Falkner, B. (2004). Race/ethnic issues in obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 89, 2590–2594. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0339

- Currie, J., & Widom, C.S. (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment, 15, 111–120. doi:10.1177/1077559509355316

- Danese, A., & Tan, M. (2014). Childhood maltreatment and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 19, 544–554.

- Demerath, E.W. (2010). Causes and consequences of human variation in visceral adiposity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91, 1–2. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28948

- Després, J.P. (2001). Health consequences of visceral obesity. Annals of Medicine, 33, 534–541. doi:10.3109/07853890108995963

- Dhurandhar, E.J. (2016). The food-insecurity obesity paradox: A resource scarcity hypothesis. Physiology and Behavior, 162, 88–92. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.025

- Felitti, V.J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D.F., Spitz, A.M., Edwards, V., … Marks, J.S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Flegal, K.M., Kruszon-Moran, D., Carroll, M.D., Fryar, C.D., & Ogden, C.L. (2016). Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA, 315, 2284–2291. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6458

- Ford, M.C., Gordon, N.P., Howell, A., Green, C.E., Greenspan, L.C., Chandra, M., … Lo, J.C. (2016). Obesity severity, dietary behaviors, and lifestyle risks vary by race/ethnicity and age in a northern california cohort of children with obesity. Journal of Obesity, 2016, 1–4287976. doi:10.1155/2016/4287976

- Grilo, C.M., & Masheb, R.M. (2001). Childhood psychological, physical, and sexual maltreatment in outpatients with binge eating disorder: Frequency and associations with gender, obesity, and eating-related psychopathology. Obesity Research, 9, 320–325. doi:10.1038/oby.2001.40

- Gustafson, T.B., & Sarwer, D.B. (2004). Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obesity Reviews, 5, 129–135. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00145.x

- Herrenkohl, R.C., & Herrenkohl, T.I. (2009). Assessing a child’s experience of multiple maltreatment types: Some unfinished business. Journal of Family Violence, 24, 485–496. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9247-2

- Hruby, A., & Hu, F.B. (2015). The epidemiology of obesity: A big picture. PharmacoEconomics, 33, 673–689. doi:10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x

- Hruby, A., Manson, J.E., Qi, L., Malik, V.S., Rimm, E.B., Sun, Q., … Hu, F.B. (2016). Determinants and consequences of obesity. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 1656–1662. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303326

- Infurna, M.R., Reichl, C., Parzer, P., Schimmenti, A., Bifulco, A., & Kaess, M. (2016). Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.006

- Katzmarzyk, P.T., Bray, G.A., Greenway, F.L., Johnson, W.D., Newton, R.L., Ravussin, E., … Bouchard, C. (2010). Racial differences in abdominal depot–specific adiposity in white and African American adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91, 7–15. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28136

- Li, L., Chassan, R.A., Bruer, E.H., Gower, B.A., & Shelton, R.C. (2015). Childhood maltreatment increases the risk for visceral obesity. Obesity, 23, 1625–1632. doi:10.1002/oby.21143

- Li, L., Garvey, W.T., & Gower, B.A. (2017). Childhood maltreatment is an independent risk factor for prediabetic disturbances in glucose regulation. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8, 151. doi:10.3389/fendo.2017.00151

- Napolitano, M.A., & Himes, S. (2011). Race, weight, and correlates of binge eating in female college students. Eating Behaviors, 12, 29–36. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.09.003

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. (2012). Child Maltreatment: Facts at a Glance.Retrieved from http://cte.sfasu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Child-Maltreatment-Data-Sheet.pdf

- Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., Margono, C., … Gakidou, E. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet, 384, 766–781. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8

- Norman, R.E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9, e1001349. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

- Petrenko, C.L.M., Friend, A., Garrido, E.F., Taussig, H.N., & Culhane, S.E. (2012). Does subtype matter? Assessing the effects of maltreatment on functioning in preadolescent youth in out-of-home care. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 633–644. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.001

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. (2004). The epidemiology of central fat distribution in relation to disease. Nutrition Reviews, 62(Suppl), S120–S126. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00081.x

- Richardson, A.S., Dietz, W.H., & Gordon-Larsen, P. (2014). The association between childhood sexual and physical abuse with incident adult severe obesity across 13 years of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Pediatric Obesity, 9, 351–361. doi:10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00196.x

- Sacks, R.M., Takemoto, E., Andrea, S., Dieckmann, N.F., Bauer, K.W., & Boone-Heinonen, J. (2017). Childhood maltreatment and BMI trajectory: The mediating role of depression. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53, 625–633. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.007

- Schneiderman, J.U., Negriff, S., Peckins, M., Mennen, F.E., & Trickett, P.K. (2015). Body mass index trajectory throughout adolescence: A comparison of maltreated adolescents by maltreatment type to a community sample. Pediatric Obesity, 10, 296–304. doi:10.1111/ijpo.258

- Scott, K.A., Melhorn, S.J., & Sakai, R.R. (2012). Effects of chronic social stress on obesity. Current Obesity Reports, 1, 16–25. doi:10.1007/s13679-011-0006-3

- Sesar, K., Simic, N., & Barisic, M. (2010). Multi-type childhood abuse, strategies of coping, and psychological adaptations in young adults. Croatian Medical Journal, 51, 406–416. doi:10.3325/cmj.2010.51.406

- Sheehan, D.V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K.H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., … Dunbar, G.C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59( Suppl):22–33; quiz 34–57.

- Shin, S.H., & Miller, D.P. (2012). A longitudinal examination of childhood maltreatment and adolescent obesity: Results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) Study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 84–94. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.007

- Springer, K.W., Sheridan, J., Kuo, D., & Carnes, M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 517–530. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003

- Tarullo, A.R., & Gunnar, M.R. (2006). Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior, 50, 632–639. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Adult Obesity Causes and Consequences. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html

- Torres, S.J., & Nowson, C.A. (2007). Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition, 23, 887–894. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008

- Trickett, P.K., Negriff, S., Ji, J., & Peckins, M. (2011). Child maltreatment and adolescent development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 3–20. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00711.x

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2017). Childhood Maltreatment 2015. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2015.pdf

- Wajchenberg, B.L. (2000). Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: Their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocrine Reviews, 21, 697–738. doi:10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415

- Walker, E.A., Gelfand, A., Katon, W.J., Koss, M.P., Von Korff, M., Bernstein, D., & Russo, J. (1999). Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Medicine, 107, 332–339. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00235-1

- Walker, E.A., Unutzer, J., Rutter, C., Gelfand, A., Saunders, K., VonKorff, M., … Katon, W. (1999). Costs of health care use by women hmo members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 609–613. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.609

- Williams, D.R., Gonzalez, H.M., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Abelson, J.M., Sweetman, J., & Jackson, J.S. (2007). Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 305–315. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305

- Williamson, D.F., Thompson, T.J., Anda, R.F., Dietz, W.H., & Felitti, V. (2002). Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. International Journal of Obesity, 26, 1075–1082. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038