Abstract

Bullying of medical residents is associated with numerous negative psychological and physiological outcomes. As bullying within this demographic grows, there is increased interest in identifying novel protective factors. Accordingly, this research investigated whether interpersonal forgiveness buffers the relationship between two forms of workplace bullying and indices of well-being. Medical residents (N = 134, 62% males) completed measures assessing person and work-related bullying victimization, dispositional forgiveness, and depressive symptoms and underwent a series of cardiovascular assessments during which cardiovascular reactivity was induced by a 3-min serial subtraction math task. It was hypothesized that the tendency to forgive would be negatively related to bullying victimization and that forgiveness would reduce the association of bullying with psychological distress (i.e. depressive symptoms), cognition errors (i.e. incorrect serial subtraction computations), and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and recovery. Findings show that forgiveness reduced the harmful relationship between the two forms of workplace bullying and depressive symptoms, serial subtraction errors, and cardiovascular reactivity and recovery for systolic blood pressure (SBP). Study results suggest that forgiveness may serve as an effective means for reducing the outcomes of bullying for medical residents. Implications for forgiveness interventions are discussed.

This research demonstrated that forgiveness reduced the harmful relationship between bullying victimization and negative outcomes (i.e. depressive symptoms, subtraction errors, and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and recovery for SBP) in medical residents. This study suggests that forgiveness may serve as a protective factor and provide an effective means for reducing the negative association between workplace bullying and negative outcomes.

Lay summary

Introduction

Workplace bullying involves the repeated mistreatment of an employee targeted by another employee(s) with a malicious confluence of humiliation, intimidation, and sabotaging of performance (Kohut, Citation2007) using behaviors which are emotionally and psychologically punishing (Yahaya et al., Citation2012). Medical residents are a demographic of increasing concern regarding workplace bullying due to their training status (i.e. naïve, novice, and in an impressionable career state) and the marked differential in authority that characterizes doctor-to-trainee and mentor-to-mentee relationships (Chadaga, Villines, & Krikorian, Citation2016; Schlitzkus, Vogt, Sullivan, & Schenarts, Citation2014). Bullying of medical residents occurs globally at an alarmingly high rate (66.5%, ranging from 30% in Ireland to 89% in India, Leisy & Ahmad, Citation2016). In a review of 62 studies, the most frequent source of bullying was fellow physicians in superior positions with the most frequent form of maltreatment consisting of verbal abuse, although many additional forms of abuse were noted (Leisy & Ahmad, Citation2016).

Resident bullying is associated with numerous negative effects, including substance use, job errors, cardiovascular disease, suicidality, and mortality (for additional negative effects, see Halim & Riding, Citation2018; Leisy & Ahmad, Citation2016; Samnani & Singh, Citation2012). The detrimental effects of bullying affect not only the victim (i.e. the medical resident), but also the victim’s interpersonal system (i.e. friends, romantic partner, child, and extended family) and the global healthcare system (Halim & Riding, Citation2018; Hymel & Swearer, Citation2015). Although the problems that arise with resident bullying are well documented, little is known about factors that may buffer its effect and thereby reduce negative states associated with resident bullying.

Dispositional forgiveness, or the tendency to forgive, may be an ideal candidate for buffering (moderating) the impact of bullying as it involves replacing the negative affective states (anger and fear) and motivations (desire to retaliate or withdraw) that follow an interpersonal transgression (insult or injury) with empathy and compassion toward the transgressor (McCullough, Citation2001). Indeed, perceived forgiveness predicts lower levels of school-aged bullying (Ahmed & Braithwaite, Citation2006) but this relationship has not been evaluated within a sample of medical trainees. Among adults, forgiveness is an effective coping response for ameliorating detrimental physiological (mostly cardiovascular) and behavioral states associated with different forms of anger, abuse, and trauma; aspects closely linked to bullying (Enright, Citation2001; Fincham, May, & Sanchez-Gonzalez, Citation2015; Lawler et al., Citation2003; May, Sanchez-Gonzalez, Hawkins, Batchelor, & Fincham, Citation2014).

Therefore, this research evaluates whether the tendency to forgive reduces the corrosive relationship between two forms of workplace bullying (person-related and work-related) and indices of well-being, including mental health, cognition, and physiology. Person-related bullying is defined as bullying behaviors directed toward the victim’s personality and character within the workplace whereas work-related bullying is defined as acts directed toward the victim to diminish work-related performance (Bartlett & Bartlett, Citation2011; Beswick, Gore, & Palerman, Citation2006; Maglich-Sespico, Faley, & Knapp, Citation2007). It was hypothesized that in a sample of medical residents, the tendency to forgive (1) will be related to both person and work-related bullying and (2) will buffer (reduce) the association of person-related and work-related bullying with negative mental health (depressive symptoms), cognition errors (serial subtraction mathematics task), and cardiovascular reactivity and recovery (i.e. an exaggerated and protracted physiological reaction to stress predictive of future cardiovascular disease, see review by Lovallo, Citation2005).

Method

Participants

A total of 134 medical residents (Mage =31.76 years, SD = 6.71, 62% males, male body mass index (BMI)=26.52 kg/m2, SD = 3.98, female BMI = 24.72 kg/m2, SD = 4.58, 28% first-year, 16% second-year, 42% third-year, and 13% fourth-year) qualified for the study. To avoid potential cardiovascular functioning confounds, participants were excluded from study participation through an online health screening assessment if they exercised regularly (>120 min/week) in the previous 6 months, used nicotine products, were hypertensive (BP > 140/90 mmHg), were taking beta blockers, antidepressants, or stimulants, or had chronic diseases (see exclusion protocol used in May, Sanchez-Gonzalez, Brown, Koutnik, & Fincham, Citation2014; May, Sanchez-Gonzalez, & Fincham, Citation2015). The ethnic composition of the sample was 39% Caucasian, 5% African American, 19% Asian/Pacific Islander, 23% Hispanic, 2% endorsed biracial, and 11% nondisclosed ethnicity. All participants were from a major teaching hospital in the southeastern United States, were informed of the nature of the study, and gave their written consent prior to study participation as approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Measures and instruments

Anthropometrics

Height was measured using a stadiometer and body weight was measured using a Seca scale (Sunbeam Products Inc., Boca Raton, FL). BMI was calculated as kg/m2.

Forgiveness

Dispositional forgiveness was measured using the 4-item Tendency to Forgive Scale (TTF; Brown, Citation2003). Dispositional forgiveness refers to an individual’s general tendency to forgive over time and across varied situations. The TTF demonstrates concurrent validity with similar trait measures of forgiveness and discriminant validity with measures of mental health (depression and life satisfaction) and state forgiveness (Brown & Phillips, Citation2005). The TTF asks participants to report how they usually respond when someone offends them. Sample items include, “I tend to get over it quickly when someone hurts my feelings,” and “I have a tendency to harbor grudges,” (reverse coded). Responses ranged from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Responses were summed to form an overall score (range = 4 − 20) with higher scores reflecting greater forgiveness (α = 0.80).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Santor & Coyne, Citation1997). The CES-D has been widely used to measure depressive symptoms in nonclinical samples. The CES-D has participants respond to a list of ways they may have felt or behaved during the previous week (0 = rarely or none of the time, 3 = most or all of the time). Items include “I felt depressed,” “I felt fearful,” and “I was happy.” Responses were summed into an overall score (range = 0 − 30) with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms (α = 0.88).

Bullying

Bullying was assessed with the person and work-related bullying subscales of the 22-item Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R; Einarsen, Hoel, & Cooper Citation2003, α = 0.94, α = 0.92, respectively). The NAQ-R asks respondents to indicate how often they have experienced negative acts or bullying behaviors over the past 6 months on a 5-point Likert rating scale (1 = never, to 5 = very frequently, more than twice a day). All items are asked without mention of the word “bullying” or “harassment.” The 15 items of the person-related bullying subscale assess actions directed toward the victim relating to aspects of the victim’s personality or character within the workplace (e.g. public humiliation, ignoring, insulting, spreading rumors or gossips, intruding on privacy, and yelling, see Beswick et al., Citation2006). Example items included, “Spreading of gossip and rumors about you” and “Being shouted at or being the target of spontaneous anger or rage.” The 7 items comprising the work-related bullying subscale assess acts directed toward the victim to diminish work-related performance (e.g. giving unachievable task, impossible deadlines, unmanageable workloads, meaningless task or supplying unclear information, threat about security, Beswick et al., Citation2006). Example items included, “Being ordered to do work below your level of competence,” “Having key areas of responsibility removed or replaced with more,” and “Being exposed to an unmanageable workload.” Summed scores were used for each subscale, with higher scores indicating greater bullying victimization. Higher NAQ-R scores have been linked to negative health indicators, work-related distress, and reduced job satisfaction (Notelaers, Einarsen, De Witte & Vermunt, Citation2006; Silva, Aquino, & Pinto, Citation2017).

Hemodynamics

Automated oscillometric blood pressure measurements were obtained using an Omron HEM-907 brachial cuff (see validity demonstrated by Choi et al., Citation2018). The pressure indices reported here include systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Electrocardiography

Heart rate (HR) and HR variability (HRV) was measured with a monitor (Polar 800CXS; Kempele, Finland) placed below the sternum. Through electrocardiography, the calculation of the time duration of intervals between heartbeats (RR intervals) was automatically detected and inspected for artifacts, premature beats, and ectopic episodes. HRV parameters were calculated using the commercially available Kubios HRV version 2.2 software (Kubios HRV Premium; Kuopio, Finland; see Tarvainen, Niskanen, Lipponen, Ranta-Aho, & Karjalainen, Citation2014, for details on QRS detection, pre-processing, and parameter calculation). As Kubious provides numerous time and frequency-domain parameters, selected HRV parameters are reported to highlight sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system balance/cardiac autonomic regulation (for a comprehensive review of HRV parameters, see Shaffer & Ginsberg, Citation2017).

Mean RR values (time period between successive heartbeats) and root mean square of successive RR interval differences (RMSSD) represent the reported time-domain HRV parameters. RMSSD is an index of the beat-to-beat variance in HR and is the primary time-domain measure utilized to represent vagally mediated changes reflected in HR (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, Citation2014) while also being minimal or less affected by respiration than respiratory sinus arrhythmia indices (Hill, Siebenbrock, Sollers, & Thayer Citation2009). Regarding the frequency-domain parameters, the ratio of the low frequency (LF; 0.04–0.15 Hz) and the high frequency (HF; 0.15–0.4 Hz) spectral HRV bands (LF/HF), the Total Power (sum of the energy in the ULF, VLF, LF, and HF bands), and normalized LF (LFnu) are reported. Calculation of nu is done by dividing the power of a given component by the total power from which the very LF band has been subtracted (Sgoifo, Carnevali, Pico Alfonso, & Amore, Citation2015). Due to structural algebraic redundancy inherent in the normalized spectral HRV measures with respect to each other (LFnu = 1-HFnu), we only report LFnu as an index of cardiac sympathovagal tone (Burr, Citation2007; Pagani et al., Citation1986). Cardiac sympathovagal tone represents the contribution of the sympathetic influence on the balance of the autonomic state resulting from sympathetic and parasympathetic influences (May et al., Citation2016). We do note that as a dynamic relationship exists between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, the ratio of LF, and HF will not absolutely indicate autonomic balance but rather a close approximation (Billman, Citation2013).

Serial subtraction task

A 3-min serial subtraction arithmetic task was administered via the DirectRT computer software program (see full procedure reported in May, Bauer, & Fincham, Citation2015). Instructions informed participants that the arithmetic task would involve subtracting 7 from a randomly selected number. Time-related pressure was eliminated as a potential confound by not telling participants there was a task time limit of 3-min. Practice trials demonstrated how a number would appear (e.g. 1107) and how the correctly computed answer (1100) would be accepted through a keystroke response. This correct response would then be the base number for the next subtraction trial. The trial would repeat if an incorrect solution was provided. The program ended after 3 min. An index of computation error was computed by dividing the number of correct computations by the number of computation attempts. In the current sample, the average number of correct computations was 26.70 (SD = 12.03) and the average number of attempts was 29.17 (SD= 11.24). Serial subtraction tasks have been identified as an acceptable proxy for functioning in the cognitive domains of attention and working memory (see a review by Bristow, Jih, Slabich, & Gunn, Citation2016) and have also been shown to effectively induce stress and cardiovascular reactivity (see review by Krantz & Manuck, Citation1984).

Procedure

Participants were recruited over 3 months in the fall of 2018 via IRB approved flyers. These flyers included an url link to online study information and allowed participants to provide informed consent before any study information was collected. After providing informed consent, participants completed an online health screener and those who met study inclusion criteria were contacted and provided a laboratory appointment time. For the laboratory visit, participants were asked to abstain from alcohol, caffeine, and strenuous physical activity for at least 24 h prior to testing. They were also instructed not to eat any food 4 h prior to the cardiovascular assessments during the laboratory visit. Female participants were asked to attend the laboratory session in the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle to avoid potential variations in pressure wave morphology and cardiac reactivity (Adkisson et al., Citation2010).

Upon arrival at the lab, participants were first introduced to the study procedures and familiarized with the lab setting. To assure a controlled setting and to minimize potential diurnal variations in vascular activity, lab sessions were conducted during the same time in the evening between 16:00 and 19:00 in a quiet, dimly lit, temperature-controlled room (73 ± 2 °F). Height and weight were measured first. Participants were then asked to complete the measurement scales via online computer access. After doing so, they underwent a series of cardiovascular assessments during which cardiovascular reactivity was induced by the 3-min serial subtraction task. Three repeated blood pressure (BP) and HR measurements were recorded at the end of the following intervals: a 5-min seated rest, the 3-min subtraction task, and a 3-min recovery period. Following the recovery period, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations between measurement scales and subtraction error rates are reported in . Prior to hypothesis testing, an exploratory t-test and one-way ANOVA were conducted to see if bullying scores differed by gender or year in medical residency. Also, to evaluate whether the serial subtraction task sufficiently induced heightened cardiovascular reactivity (i.e. a manipulation check for cardiovascular reactivity), one-way ANOVAs (comparing baseline, reactivity, and recovery phases) were conducted on each cardiovascular variable with follow up post hoc tests evaluating changes between (1) baseline vs. subtraction task and (2) baseline vs. recovery. presents descriptive statistics for physiological variables for baseline, serial subtraction task, and recovery periods.

Table 1. Correlations and descriptives of measurement scales and cognition errors.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for cardiovascular variables by task condition.

Regarding hypothesis testing, this research proposed that forgiveness scores would be related (negatively) to person and work-related bullying (Hypothesis 1) and would buffer (i.e. moderate, attenuate, or decrease) the negative relationships between person-related and work-related bullying scores and outcomes pertaining to negative mental health (depressive symptoms), cognitive errors (serial subtraction task errors), and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity (Hypothesis 2). Pearson correlations served to evaluate Hypothesis 1. To evaluate Hypotheses 2, the two-way interactions were tested using PROCESS version 3.1 (Hayes, Citation2018) in SPSS version 25 (Chicago, IL) with 5000 bootstrapped samples. PROCESS is a modeling macro that uses an observed variable OLS regression analysis to provide two-way interaction estimates and follow-up simple slopes to probe any identified significant interactions. For the physiological variables used in the PROCESS moderation analyses, two sets of change scores were calculated: (1) baseline values minus serial subtraction task values and (2) baseline values minus recovery period values. Correlations showing forgiveness and bullying relationships with baseline physiological variables are presented in . Correlations with change scores from the serial subtraction task are presented in and correlations with change scores from the recovery period are presented in . Sample size consideration was based on prior studies investigating associations between dispositional forgiveness and cardioprotective indices (see May, Sanchez-Gonzalez, Brown, et al., Citation2014 with sample sizes ranging from 80 to 134) and attenuation of cardiovascular reactivity by dispositional forgiveness scores (N = 131 in Sanchez-Gonzalez, May, Koutnik, & Fincham, Citation2015) which demonstrated small to medium effect sizes. An a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.4 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, Citation2009) of a three predictor linear multiple regression, with α set to 0.05, and contingent on a medium effect of f2 = 0.15 indicated that a minimum of 68 participants were needed to demonstrate statistically significant findings with power at 0.80. Thus, given prior sampling standards and informed by a power analysis, initial sampling included 145 participants with exclusion criteria eliminating 11 participants, leaving n = 134 for use in statistical analyses.

Table 3. Correlations between measurement scales and baseline cardiovascular variables.

Table 4. Correlations between measurement scales and change scores presenting reactivity for cardiovascular variables.

Table 5. Correlations between measurement scales and change scores presenting recovery for cardiovascular variables.

Results

Exploratory analyses demonstrated that bullying did not differ as a function of gender for either person-related bullying, t(1, 132) = 0.914, p = .363, or work-related bullying, t(1, 132) = 0.61 p = .546. Similarly, bullying did not differ between years in residency for person-related bullying, F(3, 130) = 0.13, p = .942, or work-related bullying, F(3, 130) = 0.21, p = .889. Bivariate correlations (see ) demonstrated significant negative associations between forgiveness and both person-related and work-related bullying scores as well as depression scores (but not subtraction errors). Both person and work-related bullying were positively related to depression scores and subtraction errors. Bivariate correlations with baseline cardiovascular values indicated that higher forgiveness scores related to greater RMSSD (r = 0.19) and lower LF/HF (r = −0.24). Although work-related bullying was not related to any baseline cardiovascular variable, person-related bullying was linked to increased DBP (r = 0.29), LF/HF (r = 0.25), and LFnu (r = 0.22), and decreased RMSSD (r = −0.20).

Evaluating the serial subtraction task inducement of cardiovascular reactivity, one-way ANOVA findings indicated significant differences between conditions (baseline, subtraction task, and recovery period) for all cardiovascular variable (F’s ranged from 5.94 to 87.32 with all p values <.05). Post-hoc tests demonstrated that the subtraction task sufficiently (p < .05) changed values in comparison to baseline scores (increased SBP, DBP, HR, LF/HF, LFnu, and decreased RR, RMSSD, Total Power) thus inducing cardiovascular reactivity. Regarding reactivity, correlations of change scores calculated for the serial subtraction task indicated that forgiveness was linked to suppressed SBP (r = −0.25). Person-related bullying was linked to elevated DBP (r = 0.22), HR (r = 0.20), and LF/HF (r = 0.21), and suppressed RR (r = −0.24). Work-related bullying was only linked to suppressed RR (r = −0.20). Regarding change scores calculated for the recovery period, forgiveness did not relate to any cardiovascular variable and person and work-related bullying only related to suppressed DBP (r = 0.22) and (r = 0.18), respectively.

Evaluating Hypothesis 2, regression moderation analyses indicated that forgiveness moderated the relationship between person and work-related bullying and depressive symptoms, serial subtraction errors, as well as SBP during both the subtraction task and recovery period. No other significant forgiveness by bullying interactions emerged (all other p>.05). Specifically, there was a significant interaction between forgiveness and both person, ΔF(1, 130)=4.61, p = .034, ΔR2 = 0.02, 95% CIs [−0.056, −0.002], Full Model R2 = 0.48, and work-related bullying, ΔF(1, 130)=5.32, p = .023, ΔR2 = 0.03, 95% CIs [−0.13, −0.01], Full Model R2 = 0.37, for depression scores. Similarly for cognitive performance, significant interactions emerged between forgiveness and both person, ΔF(1, 130)=4.06, p = 0.046, ΔR2 = 0.03, 95% CIs [0.001, 0.002], Full Model R2 = 0.08, and work-related bullying, ΔF(1, 130)=4.90, p = .029, ΔR2 = 0.04, 95% CIs [0.001, 0.004], Full Model R2 = 0.09, for subtraction errors.

Regarding physiology, a significant interaction between forgiveness and work-related bullying occurred for ΔSBP during the subtraction task, ΔF(1, 130)=5.91, p = .016, ΔR2 = 0.05, 95% CIs [−0.28, −0.04], Full Model R2 = 0.11, and ΔSBP during the recovery phase, ΔF(1, 130)=15.34, p<.001, ΔR2 = 0.12, 95% CIs [0.31, 0.10], Full Model R2 = 0.15. Although a significant interaction between forgiveness and person-related bullying was not found for ΔSBP during the subtraction task, ΔF(1, 130)=0.90, p = .345, the interaction did appear for ΔSBP during the recovery phase, ΔF(1, 130)=10.75, p<.001, ΔR2 = .08, 95% CIs [0.13, 0.03], Full Model R2 = 0.11.

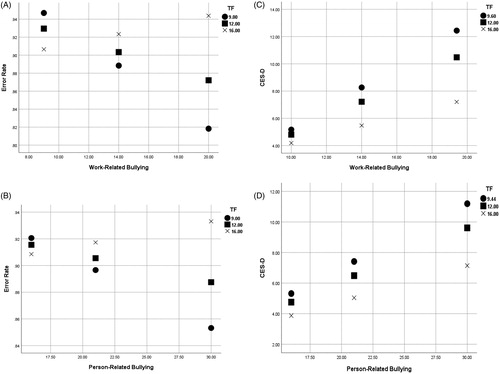

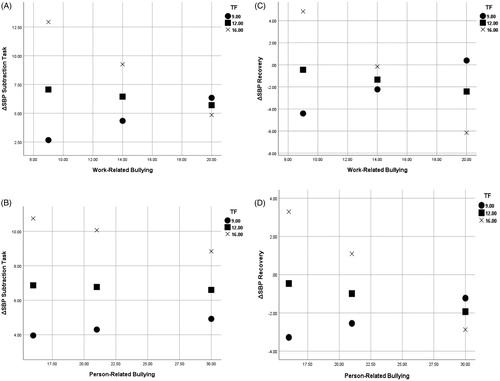

Follow-up simple slopes to the interactions indicated that increased forgiveness: (1) decreased the strength of the relationship between bullying and depression, (2) improved the relationship between bullying and math performance, and (3) (generally) attenuated ΔSBP during the subtraction task and recovery phase. displays simple slopes showing forgiveness attenuating subtraction errors and depression under person and work-related bullying. displays simple slopes showing forgiveness attenuating ΔSBP during the subtraction task and recovery phase under person and work-related bullying.

Figure 1. Simple slopes: forgiveness attenuates subtraction errors and depression under work and person-related bullying in medical residents. Note. Simples slopes of error rates for subtraction task at -1SD below mean (^), at mean (□), and at + 1SD above mean (×) of forgiveness scores for work (Panel A) and person-related bullying (Panel B). Simples slopes of depressions scores (CES-D) at -1SD below mean, at mean, and at + 1SD above mean for forgiveness scores for work (Panel C) and person-related bullying (Panel D). TF: tendency to forgive.

Figure 2. Simple slopes: forgiveness attenuates ΔSBP during the subtraction task and recovery phase under work and person-related bullying in medical residents. Note. Simples slopes of ΔSBP subtraction task at -1SD below mean (^), at mean (□), and at + 1SD above mean (×) of forgiveness scores for work (Panel A) and person-related bullying (Panel B). Simples slopes of ΔSBP at recovery at -1SD below mean, at mean, and at +1SD above mean for forgiveness scores for work (Panel C) and person-related bullying (Panel D). TF: tendency to forgive.

Discussion

Bullying in medical residency is an increasing concern. With some experts asserting that it is reaching epidemic proportions (Ayyala et al., Citation2018), raising awareness, discussion of solution strategies, and efforts to identify and bolster protective factors seem vital. Accordingly, this research examined the role interpersonal forgiveness may play in reducing the detrimental relationship between bullying victimization and well-being for medical residents. The novel findings of this research demonstrated that one’s tendency to forgive reduced the harmful relationship between two forms of bullying (person-related and work-related bullying) and indicators of negative mental health (i.e. depressive symptoms), cognitive errors (serial subtraction math errors), and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and recovery (for SBP). These findings suggest that forgiveness may serve as an effective protective factor shielding medical residents against the negative outcomes stemming from bullying victimization.

Forgiveness has been conceptualized as a coping behavior and has been shown empirically to operate as such in the context of interpersonal transgressions (Ysseldyk & Matheson, Citation2008). In this regard, it is important to note that forgiveness is conceptually unique from constructs such as denial, condoning, pardon, forgetting, and reconciliation (Fincham, Citation2015). Although limited research has shown cross-sectional relationships between forgiveness and bullying (e.g. see research in school children by Ahmed & Braithwaite, Citation2006; Ogurlu & Saricam, Citation2018), a novel aspect of this research is the establishment of forgiveness as a potential coping mechanism in the workplace to ameliorate the negative effects of bullying. This finding points to forgiveness as a potentially effective intervention point (Enright & Fitzgibbons, Citation2015). A large body of research has demonstrated the feasibility and utility of implementing standardized forgiveness interventions, even in group settings (see Fincham, Citation2015).

This research suggests that interventions based on forgiveness training may improve the health and workplace performance of the resident (e.g. victim), and it should be emphasized that this advantage may be a two-way street benefiting both the victim and the perpetrator. As described by Ahmed and Braithwaite (Citation2006), forgiveness offers a positive response toward a wrongdoer as it conveys kindness to them. The process of re-establishing a relationship of trust and hope initiated by the victim may then increase the attitude of responsibility for the well-being of the victim in the wrongdoer. Indeed, this cyclical process of forgiveness-responsibility acceptance has been linked to ending cycles of violence and reducing their occurrence (see discussions of shame management by Ahmed & Braithwaite, Citation2006; Tutu, Citation1999; Citation2001).

However, caution is necessary to avoid victim-blaming and efforts need to be made to avoid the potential pitfalls pertaining to the “dark side” of forgiveness (i.e. forgiveness leading wrongdoers to feel free to reoffend by removing unwanted consequences of their actions, McNulty, Citation2011; McNulty & Russell, Citation2016). While this field of research highlights the interpersonal nature of bullying between the victim and perpetrator, administrators concerned with medical resident bullying contend that increased efforts are still needed to increase bullying awareness at superordinate levels, for example within the medical education curriculum and within hospital organizational structures (Ayyala et al., Citation2018). In-depth discussion of these concerns are beyond the scope of the current research, but it is possible (as mentioned above) for both educational curricula and hospital organizations to integrate forgiveness interventions.

Notwithstanding the strengths of this study, several study limitations should be noted. Given our use of a cross-sectional design, the threat of reverse causality and relevant alternate hypotheses needs to be addressed via additional studies with greater sensitivity to time ordering (i.e. longitudinal studies). For example, it may be that those who are bullied may be less likely to forgive and/or depression may account for a greater likelihood of being bullied. Also, although an attempt was made to supplement use of self-report (i.e. the use of the CES-D to assess depressive symptoms) with more objective assessments (i.e. use of behavioral task via serial subtraction to assess cognition and physiological assessment to assess stress reactivity and recovery), many other indicators representative of well-being and functioning could be substituted. For example, even though the subtraction task used has been shown to approximate the cognitive domains of attention and working memory, aspects pertinent for job performance, future research may seek to instead use hospital reports of medical errors or reprimands to more proximately assess workplace performance. In a similar vein, future research may choose to utilize an alternative measure of stress induction (e.g. cold pressor task and the Trier social stress test), although the manipulation check of the subtraction task did demonstrate the task-induced reactivity in all cardiovascular parameters. Finally, the sample studied came from a single residency program and data from other residency programs in different geographical regions that replicate the current findings are needed before the results can be generalized. It is also necessary to study samples beyond those identified by this study’s exclusion criteria.

Another observation that suggests the need for caution is that the buffering effects of forgiveness on the relationships between cardiovascular functioning and bullying were not ubiquitous. Although forgiveness did show univariate relationships (correlations) with cardiovascular parameters indicative of healthier functioning (e.g. greater RMSSD, lower LF/HF, ΔSBP), SBP reactivity and recovery values were the only cardiovascular parameters moderated by forgiveness. Although prior reports link forgiveness to baseline and stress-induced cardiovascular functioning (see Fincham et al., Citation2015; Lawler et al., Citation2003), closer inspection demonstrates a more nuanced picture of reactivity. For example, Lawler et al. (Citation2003) demonstrated that dispositional forgiveness related only to SBP reactivity (and only in women) but not diastolic or mean arterial blood pressure reactivity. Associations with SBP reactivity and its attenuation are important to note, as SBP reactivity has been shown to be a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases throughout the lifespan (National High Blood Pressure Education Program, Citation2004; Zanstra & Johnston, Citation2011).

This research largely replicates prior investigations regarding univariate associations between forgiveness and health while also going beyond these to demonstrate that forgiveness can serve as a protective (moderating) factor for harmful associations (e.g. bullying–physiology relationships). This is particularly important regarding physical health as exaggerated sensitivity to cardiac stress reactivity and blunted recovery has been shown to be risk factors for the future development of cardiovascular disease (Lovallo, Citation2005). However, as the correspondence between forgiveness and cardiovascular reactivity is still relatively understudied, it would be fruitful for future research to continue to explore both physiological and psychosocial pathways and mechanisms to better explain the relationship between forgiveness, bullying, and cardiovascular functioning.

To conclude, bullying of medical residents is widespread and deleterious to their well-being. The current findings show that forgiveness reduced the harmful relationship between workplace bullying and indicators of negative mental health (i.e. depressive symptoms) and suboptimal cognitive and physiological functioning (i.e. serial subtraction errors, cardiovascular reactivity, and recovery for SBP). Thus, the present findings suggest that increasing forgiveness may serve as an effective means of reducing the negative outcomes of bullying for medical residents. Prospective intervention research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of forgiveness interventions for improving the health and work performance of physicians in training.

Disclosure statement

This study was unaccompanied by external funding. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the article. All authors assert no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ross W. May

Ross W. May, Ph.D., is a research faculty member and associate director of the Family Institute at Florida State University. His research program focuses on psychocardiology, the interplay between psychological states and physiology. His research investigates the relationship between hemodynamics, cardiac autonomic modulation, and affective states both intra and interpersonally.

Frank D. Fincham

Frank D. Fincham, Ph.D., is an Eminent Scholar at Florida State University. A former Rhodes Scholar and Fellow of six professional societies, his work received numerous professional awards, including the President’s Award for "Distinguished contributions to psychological knowledge"(British Psychological Society) and the Distinguished Career Award (International Society for Relationship Research).

Marcos A. Sanchez-Gonzalez

Marcos A. Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.D., Ph.D., EPC, is the director of Division of Clinical and Translational Research at Larkin Community Hospital. His research aims to add to the existing line of knowledge by identifying potential cardiovascular physiological mechanisms associated with emotions and behavior.

Lidia Firulescu

Lidia Firulescu, M.D., is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow within the Division of Clinical and Translational Research at Larkin Community Hospital. Her research investigates the impact of academic and work-related stress on emotions and cardiovascular autonomic modulation.

References

- Adkisson, E.J., Casey, D.P., Beck, D.T., Gurovich, A.N., Martin, J.S., & Braith, R.. (2010). Central, peripheral and resistance arterial reactivity: Fluctuates during the phases of the menstrual cycle. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 235, 111–118. doi:10.1258/ebm.2009.009186

- Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2006). Forgiveness, reconciliation, and shame: Three key variables in reducing school bullying. Journal of Social Issues, 62, 347–370. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00454.x

- Ayyala, M.S., Chaudhry, S., Windish, D., Dupras, D., Reddy, S.T., & Wright, S.M. (2018). Awareness of bullying in residency: Results of a national survey of internal medicine program directors. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10, 209–213. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00386.1

- Bartlett, J.E., & Bartlett, M.E. (2011). Workplace bullying: An integrative literature review. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13, 69–84. doi:10.1177/1523422311410651

- Beswick J, Gore J, Palferman D (2006). Bullying at work: A review of the literature. Health and safety laboratory. Retrieved from http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/hsl_pdf/2006/hsl0630.pdf

- Billman, G.E. (2013). The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Frontiers in Physiology, 4, 26. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00026

- Bristow, T., Jih, C.S., Slabich, A., & Gunn, J. (2016). Standardization and adult norms for the sequential subtracting tasks of serial 3’s and 7’s. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 23, 372–378. doi:10.1080/23279095.2016.1179504

- Brown, R.P. (2003). Measuring individual differences in the tendency to forgive: Construct validity and links with depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 759–771. doi:10.1177/0146167203029006008

- Brown, R.P., & Phillips, A. (2005). Letting bygones be bygones: Further evidence for the validity of the Tendency to Forgive scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 627–638. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.017

- Burr, R.L. (2007). Interpretation of normalized spectral heart rate variability indices in sleep research: a critical review. Sleep, 30, 913–919. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.7.913

- Chadaga, A.R., Villines, D., & Krikorian, A. (2016). Bullying in the American graduate medical education system: A national cross-sectional survey. PLOS One, 11, e0150246. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150246

- Choi, SI., Kim, Y.M., Shin, J., Lim, Y.H., Choi, S.Y., Choi, B.Y., … Woo, K.J. (2018). Comparison of the accuracy and errors of blood pressure measured by 2 types of non-mercury sphygmomanometers in an epidemiological survey. Medicine, 97, e10851. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010851

- Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Cooper, C. (Eds.). (2003). Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice. London: CRC Press.

- Enright, R.D. (2001). Forgiveness is a choice: A step-by-step process for resolving anger and restoring hope. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Enright, R.D., & Fitzgibbons, R.P. (2015). Forgiveness therapy: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Fincham, F.D. (2015). Facilitating forgiveness using group and community interventions. In S. Joseph (Ed.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 659–680). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Fincham, F.D., May, R., & Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. (2015). Forgiveness and cardiovascular functioning in married couples. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 4, 39–48. doi:10.1037/cfp0000038

- Halim, U.A., & Riding, D.M. (2018). Systematic review of the prevalence, impact and mitigating strategies for bullying, undermining behaviour and harassment in the surgical workplace. British Journal of Surgery, 105, 1390–1397. doi:10.1002/bjs.10926

- Hayes, A.F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Hill, L.K., Siebenbrock, A., Sollers, J.J., & Thayer, J.F. (2009). Are all measures created equal? Heart rate variability and respiration - biomed 2009. Biomedical Sciences Instrumentation, 45, 71–76.

- Hymel, S., & Swearer, S.M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70, 293–299. doi:10.1037/a0038928

- Kohut, M.R. (2007). The complete guide to understanding, controlling, and stopping bullies & bullying: A complete guide for teachers & parents. New Delhi, India: Atlantic Publishing Company.

- Krantz, D.S., & Manuck, S.B. (1984). Acute psychophysiologic reactivity and risk of cardiovascular disease: A review and methodologic critique. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 435–464. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.435

- Lawler, K.A., Younger, J.W., Piferi, R.L., Billington, E., Jobe, R., Edmondson, K., & Jones, W.H. (2003). A change of heart: Cardiovascular correlates of forgiveness in response to interpersonal conflict. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 373–393. doi:10.1023/A:1025771716686

- Leisy, H.B., & Ahmad, M. (2016). Altering workplace attitudes for resident education (AWARE): Discovering solutions for medical resident bullying through literature review. BMC Medical Education, 16, 127. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0639-8

- Lovallo, W.R. (2005). Cardiovascular reactivity: Mechanisms and pathways to cardiovascular disease. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 58, 119–132. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.11.007

- Maglich-Sespico, P., Faley, R.H., & Knapp, D.E. (2007). Relief and redress for targets of workplace bullying. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 19, 31–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.11.007

- May, R.W., Bamber, M., Seibert, G.S., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A., Leonard, J.T., Salsbury, R.A., & Fincham, F.D. (2016). Understanding the physiology of mindfulness: Aortic hemodynamics and heart rate variability. Stress, 19, 168–174. doi:10.3109/10253890.2016.1146669

- May, R.W., Bauer, K.N., & Fincham, F.D. (2015). School burnout: Diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 126–131. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.015

- May, R.W., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A., Brown, P.C., Koutnik, A.P., & Fincham, F.D. (2014). School burnout and cardiovascular functioning in young adult males: A hemodynamic perspective. Stress, 17, 79–87. doi:10.3109/10253890.2013.872618

- May, R.W., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A., & Fincham, F.D. (2015). School burnout: Increased sympathetic vasomotor tone and attenuated ambulatory diurnal blood pressure variability in young adult women. Stress, 18, 11–19. doi:10.3109/10253890.2014.969703

- May, R.W., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A., Hawkins, K.A., Batchelor, W.B., & Fincham, F.D. (2014). Effect of anger and trait forgiveness on cardiovascular risk in young adult females. The American Journal of Cardiology, 114, 47–52. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.007

- McCullough, M.E. (2001). Forgiveness: Who does it and how do they do it? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 194–197. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00147

- McNulty, J.K. (2011). The dark side of forgiveness: The tendency to forgive predicts continued psychological and physical aggression in marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 770–783. doi:10.1177/0146167211407077

- McNulty, J.K., & Russell, V.M. (2016). Forgive and forget, or forgive and regret? Whether forgiveness leads to less or more offending depends on offender agreeableness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 616–631. doi:10.1177/0146167216637841

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program. (2004). The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Importance of Systolic Blood Pressure. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9632/

- Notelaers, G., Einarsen, S., Elst, T.V., & Vermunt, J.K. (2006). Measuring exposure to bullying at work: The validity and advantages of the latent class cluster approach. Work and Stress, 20, 289–302. doi:10.1080/02678370601071594

- Ogurlu, U., & Sarıçam, H. (2018). Bullying, forgiveness and submissive behaviors in gifted students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2833–2843. doi:10.1007/s10826-018-1138-9

- Pagani, M., Lombardi, F., Guzzetti, S., Rimoldi, O., Furlan, R., Pizzinelli, P., … Piccaluga, E. (1986). Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circulation Research, 59, 178–193. doi:10.1161/01.RES.59.2.178

- Samnani, A.K., & Singh, P. (2012). 20 years of workplace bullying research: A review of the antecedents and consequences of bullying in the workplace. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 581–589. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.08.004

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A., May, R.W., Koutnik, A.P., & Fincham, F.D. (2015). Impact of negative affectivity and trait forgiveness on aortic blood pressure and coronary circulation. Psychophysiology, 52, 296–303. doi:10.1111/psyp.12325

- Santor, D.A., & Coyne, J.C. (1997). Shortening the CES–D to improve its ability to detect cases of depression. Psychological Assessment, 9, 233–243. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.233

- Schlitzkus, L.L., Vogt, K.N., Sullivan, M.E., & Schenarts, K.D. (2014). Workplace bullying of general surgery residents by nurses. Journal of Surgical Education, 71, e149–e154. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.08.003

- Sgoifo, A., Carnevali, L., Pico Alfonso, M. D L A., & Amore, M. (2015). Autonomic dysfunction and heart rate variability in depression. Stress, 18, 343–352. doi:10.3109/10253890.2015.1045868

- Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J.P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258

- Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C.L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: An integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1040. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01040

- Silva, I.V., de Aquino, E.M., & Pinto, I.C.D.M. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire for the detection of workplace bullying: An evaluation of the instrument with a sample of state health care workers. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Ocupacional, 42, e2. doi:10.1590/2317-6369000128715

- Tarvainen, M.P., Niskanen, J.P., Lipponen, J.A., Ranta-Aho, P.O., & Karjalainen, P.A. (2014). Kubios HRV–heart rate variability analysis software. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 113, 210–220. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.024

- Tutu, D. (1999). No future without forgiveness. London: Rider

- Tutu, D. (2001). Tutu addresses issue of forgiveness and reconciliation in wake of terrorist attacks. Episcopal News Service, October 5.

- Yahaya, A., Ing, T.C., Lee, G.M., Yahaya, N., Boon, Y., Hashim, S., & Jesus, S.K.C.I. (2012). The impact of workplace bullying on work performance. Archives Des Sciences, 65, 18–28.

- Ysseldyk, R., & Matheson, K. (2008). Forgiveness and coping. In W. Malcolm, N. DeCourville, & K. Belicki (Eds.), Women’s reflections on the complexities of forgiveness (pp. 143–163). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Zanstra, Y.J., & Johnston, D.W. (2011). Cardiovascular reactivity in real life settings: Measurement, mechanisms and meaning. Biological Psychology, 86, 98–105. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.05.002