Abstract

Schizotypy denotes psychosis-like experiences, such as perceptual aberration, magical ideation, and social anxiety. Altered physiological arousal from social stress is found in people with high schizotypal traits. Two experiments aimed to determine the relationship of schizotypy to physiological arousal from social stress. Experiment 1 tested the hypotheses that heart rate from social stress would be greater in high, than mild-to-moderate, schizotypal traits, and disorganized schizotypy would explain this effect because of distress from disorganisation. Experiment 1 tested social stress in 16 participants with high schizotypal traits and 10 participants with mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits. The social stress test consisted of a public speech and an informal discussion with strangers. The high schizotypal group had a higher heart rate than the mild-to-moderate schizotypal group during the informal discussion with strangers, but not during the public speech. Disorganized schizotypy accounted for this group difference. Experiment 2 tested the hypothesis that mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits would have a linear relationship with physiological arousal from social stress. Experiment 2 tested 24 participants with mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits performing the abovementioned social stress test while their heart rate and skin conductance responses were measured. Mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits had a linear relationship with physiological arousal during the discussion with strangers. Distress in disorganized schizotypy may explain the heightened arousal from close social interaction with strangers in high schizotypy than mild-to-moderate schizotypy. Mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits may have a linear relationship with HR during close social interaction because of difficulty with acclimatizing to the social interaction.

Introduction

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are often characterized by hearing threatening voices and having beliefs that others are going to harm them (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Schizophrenia has more severe psychopathology and a poorer rate of remission than other psychotic disorders (Harrow et al., Citation1997). These psychosis-like experiences occur at a subclinical level, and are collectively referred to as schizotypy. Schizotypy is a latent personality organization that reflects psychosis-like experiences at a subclinical level and denotes a putative liability for these schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and the psychoses (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., Citation2018; Grant et al., Citation2018). Schizotypy is a multidimensional construct that consists of a cluster of personality traits that feature both normal and aberrant variations of psychosis-proneness (Cohen et al., Citation2015; Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Schizotypy consists of three main dimensions, namely positive, negative, and disorganized traits, and a fourth possible dimension, namely eccentricity (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Positive schizotypy consists of perceptual aberrations, paranormal experiences, and spiritual and magical beliefs. Negative schizotypy consists of social anhedonia and emotional withdrawal. Disorganized schizotypy refers to cognitive slippage and loosening of association (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., Citation2017; Mason et al., Citation1995; Meehl, Citation1962). The eccentric dimension is characterized by odd behavior, odd speech, and impulsive non-conformity (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). These schizotypal traits are common in the British population, where 75% of a representative sample (n = 1,000) has encountered a paranormal experience (Pechey & Halligan, Citation2012). The incidence of such positive schizotypal traits in the general population is 100 times higher than that of schizophrenia (Hanssen et al. Citation2005). Whether schizotypal traits decompensate to schizophrenia-liability or psychosis-proneness depends on the prominence of the positive schizotypal traits (Schultze-Lutter et al., Citation2019).

Disorganized schizotypy includes social anxiety (Mason et al., Citation1995) and poor verbal fluency (Tan & Rossell, Citation2017). Disorganized schizotypy is also considered to be an analogue of thought disorder in psychosis (Coleman et al., Citation1996; Rossell et al., Citation2014). Thought disorder features illogical thinking, loose association, and peculiar language (Grant & Beck, Citation2009), as well as communication deviance within the family (Tompson et al., Citation1997). Disorganized schizotypy and thought disorder are related to elements of social anxiety, such as sensitivity to social rejection (Grant & Beck, Citation2009; Premkumar et al., Citation2018b). Hence, greater disorganized schizotypy could relate to greater perceived stress in casual social encounters.

Vulnerability to social stress along the psychosis continuum

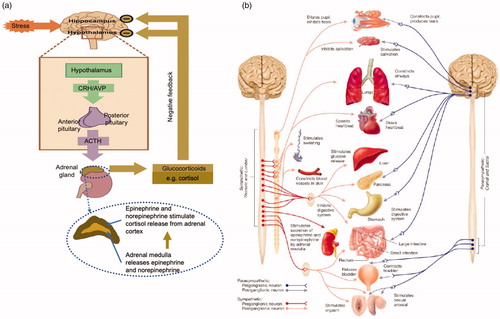

Physiological arousal from stress is a multisensory response aimed at restoring the body’s homeostasis (Day, Citation2005). Stress is characterized by nervousness, becoming upset, overreacting easily, and/or having difficulty relaxing (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). To experience social stress, one must believe that their social surroundings are taxing, exceed their resources to manage them, and/or endanger their well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). During stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis stimulates the secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla (Carlson & Birkett, Citation2017; Naughton et al., Citation2014) (). Secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine increases blood flow to the cardiac muscles, and increases heart rate (HR) and cortisol release from the adrenal cortex. Separate to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, stress activates the sympathetic branch of the vegetative nervous system, also known as the autonomous nervous system but no longer regarded autonomous because of the partial regulatory control of this nervous system (Rasia-Filho, Citation2006). Activation of the sympathetic branch of the vegetative nervous system increases HR, elicits the skin conductance response (SCR), and increases cortisol release from the adrenal cortex upon stimulating the secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla (Carlson & Birkett, Citation2017) (). SCR occurs when sympathetic preganglionic neurons within the vegetative nervous system transmit impulses across synapses to the sympathetic postganglionic neurons in the sweat glands and results in secretion of acetylcholine within the sweat glands (Carlson, Citation2001).

Figure 1. (a) Flow diagram of the response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal cortex (HPA) axis to stress. Taken with copyright permission from Naughton et al. (Citation2014). (b) The vegetative nervous system showing how the sympathetic branch increases heart rate. Taken with copyright permission from Carlson and Birkett (Citation2017).

The change in HR, SCR, and cortisol level due to stress can be tested in vitro by the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) (Kirschbaum et al., Citation1993a). The TSST is a public-speaking task and an ecologically valid measure of daily social stress (Kirschbaum et al., Citation1993a). The standard TSST consists of a 30-minute baseline resting phase, followed by a 3-minute anticipatory phase for preparing a speech on the participant’s suitability for a job, delivering a short public speech in front of a small audience for 5 minutes, performing a mental arithmetic test for 5 minutes, and lastly a 60-minute recovery phase (Allen et al., Citation2014). The long baseline and recovery phases allow for samples of plasma cortisol to be obtained whilst hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity normalizes (Allen et al., Citation2014). Higher HR and cortisol release during the public speech than the mental arithmetic task (Kirschbaum et al., Citation1993a) suggests that the public speech is more stressful than the arithmetic task.

Social stress often precedes the onset of psychosis (Lange et al., Citation2017). The stress diathesis model posits that psychosis arises from stressors, including prolonged unpleasant social interaction. These stressors interact with a preexisting vulnerability for psychosis and increase the likelihood of the onset of psychosis (Nuechterlein & Dawson, Citation1984). There is evidence for both elevated and diminished basal cortisol levels in psychosis (Bradley & Dinan, Citation2010), and elevated basal cortisol levels in high schizotypy (Walter et al., Citation2018). Elevated cortisol at baseline may indicate a hyper-aroused stress response system in individuals with schizotypal traits. Sustained daily stress could disrupt cortisol secretion in psychosis. Against this backdrop of altered basal cortisol level at baseline, patients with psychosis have a blunted cortisol response to the TSST at both the anticipatory stage and the post-speech stage (Ciufolini et al., Citation2014). Similarly, individuals with high schizotypal traits and those at risk for psychosis have been shown to have diminished cortisol release in the post-speech phase of the TSST (Walter et al., Citation2018; Pruessner et al. Citation2013). Diminished cortisol release following the public speech could imply an attenuated endocrine response to an already over-exerted hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis due to chronic arousal from daily stressors and/or slow recovery after the stressful event has passed (Collip et al., Citation2013; Walter et al., Citation2018). The change in cortisol level due to daily stress varies according to the type of at-risk group. Lower cortisol during the TSST relates to higher daily stress in individuals at risk for psychosis (Pruessner et al. Citation2013), whereas higher cortisol from daily stress relates to greater momentary psychosis-like experiences in siblings of patients with psychosis (Collip et al., Citation2011a).

HR is another measure of physiological arousal. Evidence suggests that HR increases under social stress along the psychosis continuum. Increased HR during the TSST is greater-than-normal in patients with psychosis (Lange et al., Citation2017). However, the increased HR during the TSST seen in individuals at risk for psychosis is comparable to that of healthy individuals (Pruessner et al. Citation2013). People at risk for psychosis have greater HR than health controls after listening to criticism (Weintraub et al., Citation2019), suggesting that elevated HR depends on the social context in at-risk individuals. No study to our knowledge has measured HR in people with schizotypal traits during social stress. Walter et al. (Citation2018) did not measure HR or SCR during the TSST in individuals with high schizotypal traits. When experiencing other forms of threat, such as imagining alien abduction, people with high schizotypal traits elicit greater-than-normal HR and SCR (Mcnally et al., Citation2004). Greater positive schizotypy relates to greater HR while viewing aversive pictures and films (Karcher & Glenn, Citation2012; Phillips & Seidman, Citation2008). Hence, people with high schizotypal traits and at-risk mental states may have elevated HR from perceiving social threat when imagining paranormal scenes, viewing aversive scenes, and listening to criticism.

An inverted U-shaped model of stress (Sapolsky, Citation2015; Yerkes & Dodson, Citation1998) could be used to explain the conflicting evidence of increased and decreased physiological arousal from social stress in schizotypy and at-risk mental states. HR when performing a task under observation has an inverted U-shaped relationship with social anxiety (Pujol et al., Citation2013). Increased HR during social stress, i.e. performing a task under observation, is seen in people with low social anxiety, but decreased HR is seen in patients with social anxiety disorder (Pujol et al., Citation2013). This finding suggests that persistent stress could diminish physiological arousal from social stress in high social anxiety. A similar association may be found between schizotypy and physiological arousal from social stress because social anxiety and neuroticism contribute to the distress in high schizotypal traits (Premkumar et al., Citation2015). Neuroticism is the preoccupation with negative emotions and contributes to disorganised schizotypy. Neuroticism found in disorganized schizotypy relates to the blunted cortisol response during the TSST (Grant & Hennig, Citation2018). Thus, elevated anxiety in high schizotypy could diminish physiological arousal from social stress. By studying individuals at different strata of schizotypal traits, the experiments conducted in the current study sought to test the U-shaped association between HR during social stress and schizotypy.

Social stress can be measured in vitro or in vivo, and could explain the confounding evidence of altered physiological arousal from social stress. The cortisol level was was tested in vitro and was blunted in individuals with high schizotypy and at-risk mental states under social stress (Walter et al., Citation2018; Pruessner et al. Citation2013). In contrast, cortisol level was assessed in vivo, and was elevated in genetically at-risk individuals under daily social stress (Collip et al., 2011a). Hence, stress induction may be greater when examined in vitro than in vivo. An informal discussion, when administered in vitro, might mimic daily social stress, and daily social stress elevates cortisol levels in at-risk individuals (Collip et al., Citation2011a). Hence, physiological arousal from interpersonal interaction might differ from a public speech which is a performance-based social situation.

People with high schizotypal traits could experience more stress in close interpersonal interaction than public-speaking situations because they feel paranoid in interpersonal situations (Horton et al., Citation2014). Paranoia constitutes suspiciousness, perceived hostility, and blaming others in ambiguous social situations, having less social engagement and more social problems (Combs et al., Citation2013). Individuals with a moderate level of paranoia are more alert to social threat from strangers and exhibit more momentary paranoia than those with a low level of paranoia (Collip et al., Citation2011b). High paranoia in adolescents with social anxiety disorder would further suggest that paranoia is a part of social anxiety (Pisano et al., Citation2016). People with high schizotypal traits are more anxious in interpersonal situations than people with depression-like tendencies (Miller & Lenzenweger, Citation2012). Hence, interpersonal sensitivity could be a hallmark of schizotypy.

Distress from disorganized schizotypy could explain the link between positive schizotypy and social stress because distress is more pronounced in disorganized schizotypy than positive schizotypy. Disorganized schizotypy includes social anxiety and has stronger correlations with sensitivity to rejection, criticism and praise than other schizotypal traits (Premkumar et al., Citation2018b, Citation2019). Furthermore, anxiety in schizotypy rather than “benign/happy schizotypy” could relate to physiological arousal from social stress (Grant et al., Citation2018). Benign positive schizotypy includes magical ideation, and it can be a positive experience, but not distressing (Grant & Hennig, Citation2020; Fumero, Marrero, & Fonseca-Pedrero, Citation2018). Instead, disorganized schizotypy consists of being overwhelmed, nervous, or confused, and it could explain the emergence of psychosis-like experiences when performing the TSST over and above positive and negative schizotypy (Grant & Hennig, Citation2020). Hence, the study sought to test the assumption that HR during social stress would be more strongly associated with anxiety in schizotypy, rather than benign schizotypy.

To summarize, the psychosis continuum is characterized by altered physiological arousal to social stress, namely blunted cortisol levels on the one hand but heightened HR on the other. Ambiguity about the direction of the relationship between schizotypal traits and physiological arousal from social stress could arise from (1) the non-linear nature of the relationship between social anxiety and physiological arousal during social stress (Pujol et al., Citation2013), and (2) the type of social stressor being performance-related or interpersonal. The aims of the following experiments were to determine (1) the relationship of schizotypy to physiological arousal from social stress, (2) whether this relationship differs according to the type of social stressor, namely public-speaking which is a performance-related social situation, or a discussion which is an interpersonal social situation, and (3) whether the positive and disorganized schizotypal traits differ in their relationship with physiological arousal from social stress.

Experiment 1

The main aim of the first experiment was to examine physiological arousal from social stress in schizotypy. It was hypothesized that,

People with high positive schizotypal traits would have greater HR than people with mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits during a close interpersonal interaction, namely an informal discussion,

Disorganized schizotypy would account for greater HR during an informal discussion in high positive schizotypy than mild-to-moderate positive schizotypy because disorganized schizotypy constitutes neuroticism (Mason et al., Citation1995; Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018), and

Overall schizotypy would have a non-linear positive relationship with HR during an informal discussion, such that mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits would have a positive relationship with physiological arousal and high schizotypal traits would have a weak relationship with physiological arousal. Evidence suggests that social anxiety has a non-linear relationship with HR during social stress (Pujol et al., Citation2013). We hypothesized a relationship between overall schizotypy, not positive schizotypy, and HR during an informal discussion because an overall schizotypal index encompasses social anxiety and distress from positive schizotypal traits better than either the positive or disorganized subscales alone.

Testing the validity of an informal discussion as a control task

The second aim was to determine if an informal discussion is a valid control task for the public speech task. A control task must match the experimental task in terms of social context, unpredictability, and challenge (Dickerson & Kemeny, Citation2004). An informal discussion is like a free speech which is a non-evaluative speaking task that matches a public speech in the level of social exposure and unpredictability (Het et al., Citation2009). An informal discussion is also like a social problem-solving task, such as solving an interpersonal problem or an informal discussion. A social problem-solving task is a standard social assessment and a good control task for public speaking because it matches public speaking in the level of social context, unpredictability, and challenge (Horan & Blanchard, Citation2003).

Change in mood and physiological arousal are good measures of the successful emotional manipulation of stress. Change in mood can assess the ecological validity of the TSST because it relates to the change in mood following an actual oral exam (Henze et al., Citation2017). The public speech task in the TSST increases negative mood and decreases positive mood more than the control task (free speech or mental arithmetic task) (Boesch, et al., 2014). Furthermore, social interactions alter mood and physiological arousal (Henze et al., Citation2017; Horan & Blanchard, Citation2003). A control task is valid if it elicits less negative mood and greater positive mood and less physiological arousal than the experimental task (Giles et al., Citation2014). Thus, it was hypothesized that:

4.Physiological arousal will be higher during a public speech than an informal discussion, and

5.Positive mood would be lower, but negative mood would be greater during a public speech than a discussion.

Method

Participants

Twenty-six participants (mean age = 25.8, S.D. = 6.2, 16 females) took part in the experiment. Participants were aged between 18 and 60 years and did not have a current diagnosis of psychosis. Participants were recruited by advertising the experiment on social networking websites for people with spiritual or paranormal beliefs, on the psychology department website in return for research credits and at a wellbeing event that offered psychic communication and spiritual remedies. It is thought that people with alternative spiritual beliefs score highly on schizotypal traits (Day & Peters, Citation1999). Eleven participants with high positive schizotypal traits were recruited from the well-being event and scored one S.D. above the mean score of a normative sample on O-LIFE-Unusual Experiences (Mason & Claridge, Citation2006). Sixteen participants were psychometrically defined as having high positive schizotypal traits by scoring ≥ 15 on the Unusual Experiences subscale of the O-LIFE, which represents the 75th percentile of the subscale (Mason & Claridge, Citation2006). Participants scoring <15 (n = 10) were classified as having mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits. Scores on the O-LIFE-Unusual Experiences subscale ranged from 16 to 29 in the high schizotypal group and from 0 to 12 in the mild-to-moderate schizotypal group. Participants provided informed consent before the experiment began. The experiment was approved by the University’s School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee.

Assessments

O-LIFE (Mason et al., Citation1995; Mason & Claridge, Citation2006): The O-LIFE has 104 questions to which participants answer “Yes” or “No.” The scale has four subscales, namely Unusual Experiences (positive schizotypy), Introvertive Anhedonia (negative schizotypy due to solitude and lack of enjoyment from general activity), Cognitive Disorganization (social anxiety and difficulty focusing attention) and Impulsive Nonconformity (reckless behavior). The internal reliability of these subscales ranges from acceptable to good in the current sample according to Cronbach’s alpha (α), with scores 0.88, 0.86, 0.74, and 0.69 on reliability, respectively.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al., Citation1988): The PANAS was administered to measure the change in mood during the social stress test and to test whether the informal discussion would be a valid control task for the public speech. Ten positive mood descriptors denote a state of high energy and pleasurable engagement. Ten negative mood descriptors denote aversive mood. Participants indicated how much they felt about each descriptor at that moment on a 5-point Likert scale. The positive and negative subscales have good internal reliability in the current sample, namely 0.94 and 0.86, respectively.

Social stress test

Speech: Participants were asked to deliver a 2-minute speech in front of an audience of two members. Participants spoke about their favorite subject in school and had 5 minutes to prepare the speech and make notes beforehand. Participants were asked to stand while delivering the speech. The panel gave no emotional or verbal feedback during the speech and maintained a neutral expression to minimize external cues that may affect the participant’s performance.

Informal discussion: Participants were asked to engage in a 3-minute informal discussion with the two-member audience. Participants spoke about their favorite hobby and had 5 minutes to prepare beforehand. The panel members engaged in the discussion by asking questions and sharing their thoughts about the participant’s hobbies. Participants remained seated during the discussion.

HR measurement

HR was recorded from a Biosemi Active Two electroencephalography amplifier and three Ag/AgCl electrodes. An Ag/AgCl electrode was placed close to the heart and two Ag/AgCl electrodes (reference electrodes) were placed one inch apart on the neck. HR was measured as the peak-to-peak intervals of the heartbeat and calculated as the average number of heart beats per minute (Weintraub et al., Citation2019). Heartrate was averaged over 30-second epochs, resulting in four speech epochs and six discussion epochs (Owens & Beidel, Citation2015).

Procedure

The experiment was approved by the University’s School of Social Sciences research ethics committee. Participants who met the screening criterion for schizotypy were invited to take part in the social stress test. Participants gave informed consent before the social stress test began. Participants performed the social stress test and HR was monitored. The PANAS was administered before and after the public speech and the informal discussion.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) compared the group with high schizotypal traits and the group with mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits on age and O-LIFE scores. ANOVAs were performed with group as the independent variable and HR during the social stress test as the dependent variable to test the first hypothesis. To test the second hypothesis, these ANOVAs were repeated using the standardized residual of HR as the dependent variable. The standardized residual of the HR was obtained by regressing Cognitive Disorganization on each HR variable. To test the third hypothesis, logarithmic and linear regressions were performed between positive schizotypy and HR during the six epochs of the discussion. Analyses were performed in SPSS, version 24. One-tailed tests were performed due to the directional nature of the hypotheses.

HR data and PANAS data were combined from Experiment 1 (n = 26) and Experiment 2 (n = 24) to test the fourth and fifth hypotheses. ANOVA was performed with task (speech and discussion) and time (first 4 epochs, 0–30 s, 31–60 s, 61–90 s, and 91–120 s) as the independent variables and HR as the dependent variables. Skin conductance response (SCR) was measured in addition to HR in Experiment 2 (see Experiment 2, Methods). Hence, the ANOVA was repeated with task and time as independent variables and SCR as the dependent variable in Experiment 2. ANOVAs were performed with time (baseline, post-speech, and post-discussion) as the independent variable and positive mood and negative mood as the dependent variables to test the fifth hypothesis. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied when the sphericity assumption was violated. Analyses were performed in SPSS, version 24.

Results

Group comparisons of demographic characteristics, schizotypy, and HR during the social stress test

The high positive schizotypal group had higher overall schizotypal traits, Unusual Experiences, Cognitive Disorganization and Impulsive Non-conformity than the mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal group (). The high positive schizotypal group had significantly higher HR at each epoch from 31 s to 180 s of the discussion than the mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal group. The group difference remained significant after covarying for Cognitive Disorganization at 61–90 s, F (1, 24)=3.14, p = 0.044 and at 121–150 s, F (1, 24)=3.93, p = 0.029. The group differences were no longer significant after covarying for Cognitive Disorganization at 31–90 s, F(1, 24)=2.31, p = 0.07; at 91–120 s, F (1, 24)=2.93, p = 0.05; and at 151–180 s, F (1, 24)=2.70, p = 0.057.

Table 1. Differences in demographic characteristics and heart rate between high and mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits groups in Experiment 1.

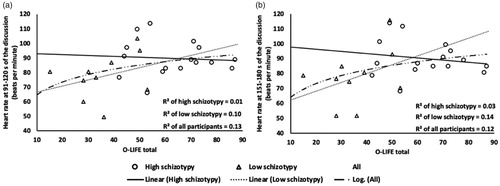

Relation between schizotypal traits and HR during the discussion

At 91–120 s of the discussion, the logarithmic regression between total schizotypal traits and HR was statistically significant, R = 0.36, R2=0.13, F (1,25)=3.51, p = 0.036. At 151–180 s of the discussion, the logarithmic regression between total schizotypal traits and HR was statistically significant, R = 0.35, R2=0.12, F (1, 25)=3.35, p = 0.040 ().

Differences in physiological arousal and mood between the public speech and informal discussion

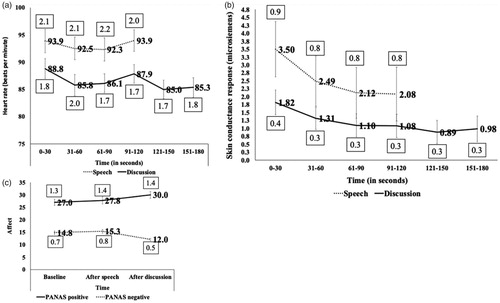

Heart rate: An ANOVA was performed with task (speech vs. discussion) and time as within-subject factors and HR as the dependent variable. The task-by-time interaction was not significant, F (3, 144)=1.31, p = 0.276, η2=03. The main effect of task was statistically significant, F (1, 48)=10.54, p = 0.002, η2=0.15, which indicated higher HR during the speech than the discussion (). There was a main effect of time, F (1.7, 129.9)=19.4, p < 0.001, η2=0.251. Separate ANOVAs for each task revealed that HR changed during the discussion (6 epochs), F (3.4, 45)=4.046, p = 0.006, η2=0.08, but not the speech, F (2.5, 120.1)=1.5, p = 0.223, η2=0.03. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons revealed higher HR at 0–30 s of the discussion than at 31–60 s, t = 3.14, p = 0.021, Cohen’s d = 0.44, and 121–150 s, t = 3.81, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.54. No differences between time were observed during the speech.

Figure 3. Change in (a) HR and (b) skin conductance between 30-second epochs during the 2 min speech (solid line) and 3 min discussion (dotted line), (c) positive affect (solid line) and negative affect (dotted line) before and after the speech and discussion. Values on the trend lines are means. Values in boxes are the standard error of the mean.

Skin conductance: An ANOVA with task (speech vs. discussion) and time as within-subject factors and SCR as the dependent variable revealed a task-by-time interaction, F (3, 69)=5.51, p = 0.002, η2=0.19 (). In addition, the main effect of task was statistically significant, F (1, 69)=11.22, p = 0.003, η2=0.3, indicating higher SCR during the speech than the discussion. The main effect of time was not significant, F (1.1, 46.9)=2.32, p = 0.139, η2=0.09. To test the task-by-time interaction further, separate ANOVAs were performed with time as the independent variable and SCR during the speech and discussion as the dependent variables. The ANOVA with speech as the dependent variable was significant, F (1.1, 26.3)=9.99, p = 0.003, η2=0.3. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons revealed a change in SCR over time during the speech, with greater SCR at 0–30 s than at 31–60 s, t (23)=3.18, p = 0.025, Cohen’s d = 0.65; 61–90 s, t (23)=3.37, p = 0.016, Cohen’s d = 0.69; and 91–120 s, t (23)=3.16, p = 0.03, Cohen’s d = 0.64. SCR was greater at 31–60 s than at 61–90 s, t (23)=3.08, p = 0.032, Cohen’s d = 0.63. In addition, the ANOVA with discussion as the dependent variable was significant, F (2.2, 51.6)=5.30, p = 0.006, η2=0.19. SCR was greater at 0–30 s than at 121–150 s, t = 3.26, p = 0.051, Cohen’s d = 0.67.

Positive mood changed over time (baseline, post-speech and post-discussion), F (2, 98)=8.63, p < 0.001, η2=0.15 (). Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons revealed lower positive mood during the speech than the discussion, t (49)= −3.15, p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.45; and at baseline than the discussion, t (49)= −3.68, p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.52. Negative mood also changed over time, F (2, 98)=15.7, p < 0.001, η2=0.24. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons revealed greater negative mood during the speech than the discussion, t (49)=5.37, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.759, and at baseline than the discussion, t (49)=4.5, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.64.

Discussion

The first experiment tested the hypotheses that (1) physiological arousal would be higher between people with high and mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits during a social stress test, (2) disorganized schizotypy would account for the differences between the groups with high and mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits in HR during an informal discussion, and (3) the relation of schizotypy to physiological arousal from social stress would be non-linear. The first hypothesis was supported. As hypothesized, HR was higher in the group with high schizotypal traits than the group with mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits during 31 s to 150 s of the discussion. This relationship was absent from the public speaking stage of the social stress test. Hence, schizotypy may affect social stress in close social interaction more than performance situations. Social interactions, such as delivering a public speech, have anticipation (the minute before the interaction), confrontation (first minute), and adaptation stages (last minute) (Sawyer & Behnke, Citation2002). Having higher HR during the discussion in the group with high schizotypal traits would suggest that people with high schizotypal traits have difficulty acclimatizing to a close interaction with strangers. People with high schizotypal traits may continue to feel nervous and have difficulty relaxing when interacting with strangers. Individuals at a high risk of psychosis have increased HR following criticism from a stranger which constitutes communication in an interpersonal situation (Weintraub et al., Citation2019). Being sensitized to criticism and rejection, people with high schizotypal traits may anticipate more social threat than normal in interpersonal interaction situations (Premkumar et al., Citation2018b; Citation2019). People with high positive schizotypal traits may have also found the informal nature of the discussion particularly stressful because of their propensity for anomalous experiences and paranoia during daily social interactions (Horton et al., Citation2014). The topic for the informal discussion was about hobbies which is more informal than the topic of their favorite subject in school for the public speech. The personal nature of the discussion could have provoked anxiety. The finding concerning the second hypothesis supports this view. As hypothesized, disorganized schizotypy fully accounted for differences in HR between the high and mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal groups at early and late stages of the informal discussion. This finding supports the view that disorganized schizotypy accounts for the distress in positive schizotypy (Grant & Hennig, Citation2020). Engaging in a discussion with a stranger may require more cognitive control than just “giving a prepared speech,” as holding a discussion involves following a conversation and interacting with others. Thus, the informal discussion may have emphasized the cognitive difficulties found in disorganized schizotypy.

The third hypothesis was also supported. There was a non-linear relationship between schizotypy and HR during the middle-to-late stages of the discussion. An inverted U-shaped pattern of physiological arousal from stress is also seen in social anxiety, extraversion, and neuroticism (Burkhard & Wolfgang, Citation1992; Pujol et al., Citation2013; Sapolsky, Citation2015; Werre, Citation1987). Physiological arousal during an informal discussion with strangers may co-vary linearly with mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits but reach a plateau at a high level of schizotypal traits owing to emotional dysregulation during close social interaction at a high level of schizotypal traits (Collip et al., Citation2013). A larger sample of n = 25 of people with mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits would have 80% power to test a linear relation between mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits and HR during a discussion.

Differences in HR, SCR and mood changes between the speech and informal discussion

As hypothesized, the levels of HR and SCR were higher during the public speech than the informal discussion. Furthermore, HR and SCR were higher at the confrontation stage (0–30 s) than at the adaptation stage (121–150 s) of the discussion task. HR is highest at the confrontation stage of social situations because people habituate to the social stressor following sensitization (Sawyer & Behnke, Citation2002). The higher physiological arousal during the public speech than the discussion and the habituation to the discussion over the time signature would suggest that the discussion is a suitable control task. SCR was also higher at the start of the speech than at later stages. Positive mood was lower, but negative mood was higher after the public speech than after the discussion, which supported the hypotheses. These results suggest that an informal discussion is a suitable control task for the speech task. As a control task, the discussion elicits less physiological arousal and change in mood than the experimental task (Giles et al., Citation2014). Future testing should counterbalance the task order to account for differences in task difficulty. It is possible that any difference in response between the two paradigms may be due to participants receiving verbal and non-verbal feedback (which is potentially rewarding) during the informal discussion. Although the panel maintained a neutral stance, the reciprocal nature of the discussion might have contributed toward improvement in mood during the informal discussion.

Experiment 2

Evidence suggests that having responses from multiple measures of physiological arousal can strengthen the validity of finding a relationship between schizotypy and social stress. SCR is another sensitive measure of physiological arousal besides HR (Coren & Mah, Citation1993; Rozenman et al., Citation2017). Emotional arousal tasks elicit heightened SCR across the psychosis continuum (Kring & Moran, Citation2008). A high level of positive schizotypal traits relates to greater SCR when watching aversive pictures (Ragsdale et al., Citation2013) and hearing innocuous acoustic tones (Allen et al., Citation2007), which suggests that SCR is elevated in schizotypal traits. Hence, the second experiment measured SCR and HR in response to social stress.

Experiment 1 found that disorganized schizotypy explained the difference in physiological arousal between high and mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal groups. This experiment aimed to explore this relationship further. Disorganized schizotypy comprises distress because it includes items about neuroticism when it is measured by the O-LIFE Cognitive Disorganization subscale. Items about neuroticism within O-LIFE Cognitive Disorganization explain the relationship between disorganized schizotypy and a blunted cortisol response to the TSST (Grant & Hennig, Citation2018). Together, these findings suggests that distress in disorganized schizotypy relates to social stress. Stress when engaging in a discussion with strangers may correspond with features of disorganized schizotypy concerned with social anxiety, including maintaining cognitive control over the direction of the conversation, difficulty with speech expression and comprehension, and discomfort when speaking on topics of a personal nature. So, social anxiety could specifically explain the relationship between positive schizotypy and increased SCR from social stress. Social anxiety is an intense fear of being rejected, embarrassed, or humiliated in social and performance situations (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000). People with social anxiety avoid looking at positive and negative facial expressions before delivering a speech (Mansell et al., Citation1999; Singh et al., Citation2015). People with social anxiety are vigilant for rejection and expect to be more accepted than people with low social anxiety (Harrewijn et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, anxiety in disorganized schizotypy may be related more closely to social threat when interacting with strangers than in a public speech, since anxiety and neuroticism explain the relationship between mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits and vigilance for rejection (Kwapil et al., Citation2012; Premkumar et al., Citation2015).

The aims of this experiment were to test (1) the linear relation of mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits to multiple indices of physiological arousal during a social stress test, and (2) the role of social anxiety in disorganized schizotypy in this relationship. It was hypothesized that:

Mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits will relate to greater physiological arousal (HR and SCR) during social stress, and

Disorganized schizotypy as social anxiety will mediate the relation between mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits and physiological arousal in a close interaction.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-four participants (mean age = 24.4 years, S.D. = 9.5, range = 20 to 57) were recruited from the University student population by social networking and advertising the experiment in the psychology department in return for research credits. A third of the sample (n = 16) was female. Participants who scored ≤13 out of 74 on the SPQ total were classed as having mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits. A score below 13 on the SPQ denotes the 90th percentile of schizotypal traits in the healthy population with the local region (Castro & Pearson, Citation2011),

Assessments

Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ) (Raine, Citation1991): The SPQ has 74 items to which participants respond “Yes” or “No.” The SPQ was used instead of the O-LIFE, because the SPQ contains nine subscales that are based on the diagnostic criteria of Schizotypal Personality Disorder (Asai et al., Citation2011; Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Hence, it is possible to examine these finer constructs in relation to physiological arousal (). These subscales combine into the three dimensions of schizotypal traits, namely Cognitive-Perceptual (positive schizotypy), Interpersonal (social anxiety, no close friend), and Disorganized (odd speech and behavior). However, the SPQ is less adept at measuring psychometrically-defined schizotypy than the O-LIFE (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Still, the internal reliability of the three main subscales in the current sample ranges from poor to acceptable, having Cronbach’s α values of 0.55, 0.83, and 0.72 respectively.

Table 2. One-tailed Pearson correlations, r (p), between schizotypal traits (total and subscale scores of the SPQ), social anxiety and heart rate averaged over 30 s epochs during a public speech test and an informal discussion in Experiment 2.

Leibowitz Social Phobia Scale (LSPS) – self-report version (Liebowitz, Citation1987; Safren et al., Citation1999): The scale measures anxiety and avoidance in 11 social interaction situations and 13 performance-related situations, resulting in four subscales, namely Social Interaction-related Anxiety and Social Interaction-related Avoidance, Performance-related Anxiety and Performance-related Avoidance. Participants rate each item on anxiety and avoidance (0 = none to 3 = severe). The subscales have good internal reliability in the current sample, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.81, 0.81, 0.87, and 0.88 respectively.

HR and SCR measurement

HR and SCR were recorded from a Biopac MP160 system with a Bionomadix wireless photoplethysmograph. HR was recorded from a pulse transducer placed on the fifth-digit finger of the left hand that recorded the pulse pressure waveform. SCR was recorded from Ag/AgCl electrodes placed on the second-digit and third-digit fingers of the left hand that were connected to an SCR amplifier. HR and SCR data were recorded at 75 kiloHz and transmitted to the AcqKnowledge computer software. HR was measured as the peak-to-peak intervals of the heartbeat. HR was calculated as the number of heart beats per minute (Weintraub et al., Citation2019) and averaged over 30 s epochs (Owens & Beidel, Citation2015). SCR was calculated as the absolute conductance averaged over 30 s epochs (Öhman, Citation1981, p. 91).

Procedure

The experiment was approved by the University’s School of Social Sciences research ethics committee. Participants gave informed consent and proceeded to complete the self-report assessments. The social stress test was administered in an identical manner to that of experiment 1. Participants rated the PANAS before and after the public speech and the informal discussion.

Statistical analyses

One-tailed Pearson correlations between schizotypy and physiological arousal tested the first hypothesis. A mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986) tested the second hypothesis. Zero-order correlations first tested for statistically significant relationships among SPQ-Cognitive-Perceptual (the predictors), SPQ-social anxiety, SPQ-odd speech and LSPS-Social Interaction Anxiety (the mediators) and the physiological responses (the outcome variable). Mediation analyses were performed with SPQ-Cognitive-Perceptual as the predictor (X), SPQ-social anxiety, SPQ-Odd Speech and LSPS-Social Interaction Anxiety as the mediators (M), and HR at 0–30 as the outcome variable (Y). HR at 0–30 s alone was used as the outcome variable because it correlated with schizotypal traits and LSPS-Social Interaction Anxiety (see results). The SPQ Disorganized subscale was not used as a mediator because it does not measure “true” disorganized schizotypy as well as O-LIFE Cognitive Disorganization (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Instead, many items from the Social Anxiety and Odd speech subscales of the SPQ go to form the “adjusted factor” for disorganized schizotypy (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Hence, the SPQ-Odd Speech subscale of Disorganized dimension alone was used in the mediation analyses. The mediation analyses were performed using PROCESS, version 3.3 (Hayes, Citation2018).

Results

Total SPQ and all three SPQ dimensions were correlated with HR at 0–30 s of the discussion (). SPQ Cognitive-Perceptual was also correlated with HR at 31–60 s of the discussion. Of the SPQ Cognitive-Perceptual dimension, the Magical Thinking subscale was correlated with HR at 31–60 s, 91–120 s and 121–150 s of the discussion, and the Unusual Experiences subscale was correlated with HR at 0–30 s, 31–60 s, 61–90 s and 151–180 s of the discussion. LSPS – Social Interaction Anxiety was correlated with total SPQ, the Interpersonal and Disorganized SPQ dimensions, and the SPQ subscales of Magical Thinking, Suspiciousness, Social Anxiety, Odd or Eccentric Behavior, and Odd Speech. LSPS – Social Interaction Anxiety was correlated with HR at 0–30 s and 31–60 s of the discussion. In a mediation analysis, the following mediators – namely, SPQ-Social Anxiety, SPQ-Odd Speech, and LSPS-Social Interaction Anxiety – fully mediated the relation between SPQ Cognitive-Perceptual and HR at 0–30 s of the discussion ().

Table 3. Mediation analyses with Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire Cognitive-Perceptual as the predictor variable (X), heartrate at 0–30 s of the discussion (Y) and SPQ-Social Anxiety, SPQ-Odd Speech and Leibowitz social phobia scale (LSPS) – Social Interaction Anxiety as the mediators (M).

Total SPQ, the Cognitive-Perceptual dimension and its subscale of Referential Thinking, the Interpersonal dimension and its subscale of No Close Friends correlated with greater SCR at each epochs of the discussion from 31 to 180 s of the discussion. LSPS-Social Interaction Anxiety correlated with greater SCR at 31–120 s of the speech.

Discussion

This is the first experiment to our knowledge to study the relationship between mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits and physiological arousal during a social stress test and the role of social anxiety in this relationship. As hypothesized, a linear relationship emerged between mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits and physiological reactivity to social interaction. The relationship between schizotypy and social stress was linear when examining mild-to-moderate schizotypy. Social anxiety and odd speech fully mediated the relation between positive schizotypy and HR at 0–30 seconds. Greater overall schizotypy and its three dimensions, namely Cognitive-Perceptual, Interpersonal and Disorganized, related to greater HR at the start of the discussion. The Magical Thinking and Unusual Experiences subscales of SPQ-Cognitive-Perceptual related to greater HR from 31 s to 180 s of the discussion. The subscales of Referential Thinking and No Close Friends related to greater SCR throughout the discussion.

The first minute of taking part in a social interaction is known as the confrontation stage. HR is highest at the confrontation stage (Sawyer & Behnke, Citation2002). The Cognitive-Perceptual, Interpersonal, and Disorganization dimensions of the SPQ related to greater HR at the confrontation stage of the discussion. A greater level of these dimensions of schizotypal traits from mild-to-moderate levels may be associated with more stress of encountering close social interaction with strangers. A greater level of certain positive schizotypal traits, namely Referential Thinking, Magical Thinking, and Unusual Experiences, and the interpersonal trait of having No Close Friends could accompany higher HR and SCR. The finding that these relationships were present at each time point suggests that stress is elevated throughout the close social interaction with strangers. Stress is characterized by difficulty relaxing, getting nervous, and overreacting (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). Experiencing moderate levels of these positive and interpersonal schizotypal traits could make it difficult to relax with a stranger. Specifically, referential thinking could increase judgemental biases during social interaction and social anxiety (Meyer & Lenzenweger, Citation2009; Morrison & Cohen, Citation2014). Referential thinking is when casual external events, such as social encounters, are interpreted incorrectly as having an unusual meaning. Also, experiencing interpersonal schizotypal traits, such as having no close friends, relates to poor recognition of non-verbal cues during social interaction (Shean et al., Citation2007).

Social anxiety and odd speech denote disorganized schizotypy (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). The Social Anxiety and Odd Speech subscales of the SPQ mediated the association between positive schizotypy as measured by Cognitive-Perceptual dimension of the SPQ and HR at the beginning (0–30 s) of the discussion. This finding supports the view that disorganization can account for the distress in positive schizotypy (Grant & Hennig, Citation2020) and “effects of disorganized schizotypy are likely to be mis-attributed to positive/negative schizotypy” (Grant & Hennig, Citation2020). The finding mirrors the mediation of the effect of positive schizotypy on physiological arousal during social interaction by disorganized schizotypy found in Experiment 1. Among the schizotypal dimensions, disorganized schizotypy relates most strongly to social anxiety due to sensitivity rejection, criticism, and praise (Premkumar et al., Citation2018b; Citation2019). Hence, disorganized schizotypy may contribute toward distress in positive schizotypy (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Social anxiety in disorganized schizotypy may be characterized by more confusion and nervousness in social gatherings making it hard for people with disorganized schizotypal traits to follow the conversation (Oezgen & Grant, Citation2018). Social anxiety due to perceiving more criticism and rejection and less praise in schizotypy may play out in casual social interactions. Latent anxiety from past social interactions, either with family or peers, may relate to increased momentary stress in casual social interactions.

Limitations and directions for future research

Physiological arousal was not measured at baseline before the social stress test. Thus, the effect of antecedent extraneous stressors on HR and SCR or increased basal physiological arousal cannot be ruled out. Participants delivered the speech while standing but engaged in the discussion while sitting which could have confounded the differences observed in physiological arousal between the speech and the discussion. Future research could include a nonsocial condition as an additional control task. Administering different schizotypal scales in Experiments 1 and 2 would make it difficult to directly compare the findings from both experiments. Still, both experiments showed that schizotypy relates to social stress and this relationship is consistent across measures of schizotypal traits. The absence of a relation between schizotypy and physiological arousal during the public speech contrasts with previous findings (Grant & Hennig, Citation2018; Walter et al., Citation2018). The public speech task lasted for 2 minutes in the current study, while the public speech task lasts for 5 minutes in the TSST. Participants were given 5 minutes to prepare the speech in the current study compared to 10 minutes in the original TSST. Furthermore, the public-speaking task may have been less stressful in the current study than in the original TSST. The topic of the speech in the current study was about participants’ favorite subject in school, whereas the topic of the speech in the original TSST and the modified TSST (Grant & Hennig, Citation2018; Walter et al., Citation2018) which was about applying for their dream job. Future research could examine altered functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal cortex axis (Walter et al., Citation2018) and the vegetative nervous systems in terms of the pituitary volume, because the pituitary volume varies with the severity of psychosis (Shah et al., Citation2015) and is amenable to psychological intervention (Premkumar et al., Citation2018a).

Conclusion

An informal discussion with strangers is a valid control task for a public speech task in the social stress test as well as a sensitive test of social stress in schizotypy. The study found that participants with a high level of positive schizotypal traits had heightened physiological arousal during this informal discussion than participants with low-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits. A non-linear relationship exists between overall schizotypal traits and HR when interacting with strangers in Experiment 1, which could imply dysregulation of the vegetative nervous system in high schizotypal traits, but upregulation of the physiological arousal system in mild-to-moderate schizotypy. These findings lend support to the U-shaped relationship between arousal and stress (Sapolsky, Citation2015; Yerkes & Dodson, Citation1998). Having high positive schizotypal traits could inhibit the ability to acclimatize to informal social interaction. Acclimatization to social stress may co-exist with mild-to-moderate positive schizotypy, since mild-to-moderate positive schizotypal traits have a positive linear relationship with physiological arousal during social interaction. Distress in disorganized schizotypy could mediate the relationship between mild-to-moderate positive schizotypy and physiological arousal during social interaction (Grant & Hennig, Citation202019). Social anxiety in disorganized schizotypy may allow stress to persist in casual social interactions with strangers. Sensitivity to criticism and rejection are forms of social anxiety that relate strongly to disorganized schizotypy (Premkumar et al., Citation2018b, Citation2019). Such social anxiety could be associated with experiencing heighten arousal during social interaction with strangers.

Authors’ contributions

Prasad Alahakoon and Madelaine Smith collected the data. All authors contributed toward the data analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in drafting, writing or revising the research report and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the reviewers for their detailed and constructive review of the manuscript and their thoughtful suggestions in improving the analyses and interpretation of the findings.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen, P., Freeman, D., & McGuire, P. (2007). Slow habituation of arousal associated with psychosis proneness. Psychological Medicine, 37(4), 577–582. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706009615

- Allen, A. P., Kennedy, P. J., Cryan, J. F., Dinan, T. G., & Clarke, G. (2014). Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: Focus on the Trier Social Stress Test. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 38, 94–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.005

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association.

- Asai, T., Sugimori, E., Bando, N., & Tanno, Y. (2011). The hierarchic structure in schizotypy and the five-factor model of personality. Psychiatry Research, 185(1–2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.07.018

- Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bebbington, P., & Kuipers, L. (1994). The predictive utility of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: An aggregate analysis. Psychological Medicine, 24(3), 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700027860

- Bellack, A. S., Mueser, K. T., Wade, J., Sayers, S., & Morrison, R. L. (1992). The ability of schizophrenics to perceive and cope with negative affect. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 160, 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.160.4.473

- Boesch, M., Sefidan, S., Ehlert, U., Annen, H., Wyss, T., Steptoe, A., & La Marca, R. (2014). Mood and autonomic responses to repeated exposure to the Trier Social Stress Test for Groups (TSST-G). Psychoneuroendocrinology, 43, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.02.003

- Bradley, A. J., & Dinan, T. G. (2010). A systematic review of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function in schizophrenia: implications for mortality. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 24(4 Suppl), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359786810385491

- Burkhard, B., & Wolfgang, B. (1992). The arousal-activation theory of extraversion and neuroticism: A systematic analysis and principal conclusions. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 14(4), 211–246.

- Carlson, N. R. (2001). Physiology of Behavior (Vol. 7). Allyn and Bacon.

- Carlson, N. R., & Birkett, M. A. (2017). Physiology of behaviour (12th ed.). Pearson.

- Castro, A., & Pearson, R. (2011). Lateralisation of language and emotion in schizotypal personality: Evidence from dichotic listening. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(6), 726–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.017

- Ciufolini, S., Dazzan, P., Kempton, M., Pariante, C., & Mondelli, V. (2014). HPA axis response to social stress is attenuated in schizophrenia but normal in depression: Evidence from a meta-analysis of existing studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.004

- Cohen, A., Mohr, C., Ettinger, U., Chan, R., & Park, S. (2015). Schizotypy as an organizing framework for social and affective sciences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(Suppl 2), S427–S435. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu195

- Coleman, M. J., Levy, D. L., Lenzenweger, M. F., & Holzman, P. S. (1996). Thought disorder, perceptual aberrations, and schizotypy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(3), 469–473. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.469

- Collip, D., Nicolson, N. A., Lardinois, M., Lataster, T., van Os, J., & Myin-Germeys, I, G.R.O.U.P. (2011a). Daily cortisol, stress reactivity and psychotic experiences in individuals at above average genetic risk for psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 41(11), 2305–2315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711000602

- Collip, D., Oorschot, M., Thewissen, V., Van Os, J., Bentall, R., & Myin-Germeys, I. (2011b). Social world interactions: How company connects to paranoia. Psychological Medicine, 41(5), 911–921. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710001558

- Collip, D., Wigman, J. T. W., Myin-Germeys, I., Jacobs, N., Derom, C., Thiery, E., Wichers, M., & van Os, J. (2013). From epidemiology to daily life: linking daily life stress reactivity to persistence of psychotic experiences in a longitudinal general population study. PLoS One, 8(4), e62688. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062688

- Combs, D. R., Finn, J. A., Wohlfahrt, W., Penn, D. L., & Basso, M. R. (2013). Social cognition and social functioning in nonclinical paranoia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 18(6), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2013.766595

- Coren, S., & Mah, K. B. (1993). Prediction of physiological arousability: a validation of the Arousal Predisposition Scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31(2), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(93)90076-7

- Day, T. (2005). Defining stress as a prelude to mapping its neurocircuitry: No help from allostasis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 29(8), 1195–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.005

- Day, S., & Peters, E. (1999). The incidence of schizotypy in new religious movements. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00218-9

- Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Cute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 355–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Debbané, M., Ortuño-Sierra, J., Chan, R. C. K., Cicero, D. C., Zhang, L. C., Brenner, C., Barkus, E., Linscott, R. J., Kwapil, T., Barrantes-Vidal, N., Cohen, A., Raine, A., Compton, M. T., Tone, E. B., Suhr, J., Muñiz, J., Fumero, A., Giakoumaki, S., … Jablensky, A. (2018). The structure of schizotypal personality traits: A cross-national study. Psychological Medicine, 48(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001829

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Ortuño-Sierra, J., de Álbeniz, A. P., Muñiz, J., & Cohen, A. S. (2017). A latent profile analysis of schizotypal dimensions: Associations with psychopathology and personality. Psychiatry Research, 253, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.038

- Fumero, A., Marrero, R. J., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2018). Well-being in schizotypy: The effect of subclinical psychotic experiences. Psicothema, 30(2), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2017.100

- Giles, G. E., Mahoney, C. R., Brunyé, T. T., Taylor, H. A., & Kanarek, R. B. (2014). Stress effects on mood, HPA axis, and autonomic response: Comparison of three psychosocial stress paradigms. PLoS One, 9(12), e113618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113618

- Grant, P., & Beck, A. (2009). Evaluation sensitivity as a moderator of communication disorder in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 39(7), 1211–1219. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709005479

- Grant, P., Green, M. J., & Mason, O. J. (2018). Models of schizotypy: The importance of conceptual clarity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(suppl_2), S556–S563. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby012

- Grant, P., & Hennig, J. (2018). Stress induced cortisol release and schizotypy – The importance of cognitive slippage and neuroticism. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 96, 142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.06.016

- Grant, P., & Hennig, J. (2020). Schizotypy, social stress and the emergence of psychotic-like states – a case for benign schizotypy. Schizophrenia Research, 216, 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.052

- Hanssen, M., Bak, M., Bijl, R., Vollebergh, W., & van Os, J. (2005). The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 2), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29611

- Harrewijn, A., van der Molen, M. J., van Vliet, I. M., Tissier, R. L., & Westenberg, P. M. (2018). Behavioral and EEG responses to social evaluation: A two-generation family study on social anxiety. NeuroImage: Clinical, 17, 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.11.010

- Harrow, M., Sands, J. R., Silverstein, M. L., & Goldberg, J. F. (1997). with more debilitating effects than other psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 23(2), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/23.2.287

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). Guildford Press.

- Henze, G. I., Zänkert, S., Urschler, D. F., Hiltl, T. J., Kudielka, B. M., Pruessner, J. C., & Wüst, S. (2017). Testing the ecological validity of the Trier Social Stress Test: Association with real-life exam stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 75, 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.002

- Het, S., Rohleder, N., Schoofs, D., Kirschbaum, C., & Wolf, O. (2009). Neuroendocrine and psychometric evaluation of a placebo version of the ‘Trier Social Stress Test’. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(7), 1075–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.008

- Horan, W., & Blanchard, J. (2003). Emotional responses to psychosocial stress in schizophrenia: the role of individual differences in affective traits and coping. Schizophrenia Research, 60(2-3), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00227-X

- Horton, L. E., Barrantes-Vidal, N., Silvia, P. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2014). Worries about being judged versus being harmed: disentangling the association of social anxiety and paranoia with schizotypy. PLoS One, 9(6), e96269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096269

- Karcher, N., & Glenn, S. (2012). Magical ideation, schizotypy and the impact of emotions. Psychiatry Research, 197(1–2), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.033

- Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K., & Hellhammer, D. (1993a). The Trier Social Stress Test – a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1–2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000119004

- Kring, A., & Moran, E. (2008). Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: Insights from affective science. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(5), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn071

- Kwapil, T., Brown, L., Silvia, P., Myin-Germeys, I., & Barrantes-Vidal, N. (2012). The expression of positive and negative schizotypy in daily life: an experience sampling study. Psychological Medicine, 42(12), 2555–2566. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712000827

- Lange, C., Deutschenbaur, L., Borgwardt, S., Lang, U., Walter, M., & Huber, C. (2017). Experimentally induced psychosocial stress in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 182, 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.008

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Liebowitz, M. (1987). Social Phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. https://doi.org/10.1159/issn.0077-0094

- Lovibond, S., & Lovibond, P. (1995). Manual for the depression, anxiety and stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation.

- Mansell, W., Clark, D. W., Ehlers, A., & Chen, Y. P. (1999). Social anxiety and attention away from emotional faces. Cognition & Emotion, 13(6), 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379032

- Mason, O., & Claridge, G. (2006). The Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE): Further description and extended norms. Schizophrenia Research, 82(2-3), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.845

- Mason, O., Claridge, G., & Jackson, M. (1995). New scales for the assessment of schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00132-C

- Mcnally, R., Lasko, N., Clancy, S., Macklin, M., Pitman, R., & Orr, S. (2004). Psychophysiological responding during script-driven imagery in people reporting abduction by space aliens. Psychological Science, 15(7), 493–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00707.x

- Meehl, P. (1962). Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. American Psychologist, 17(12), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041029

- Meyer, E. C., & Lenzenweger, M. F. (2009). The specificity of referential thinking: A comparison of schizotypy and social anxiety. Psychiatry Research, 165(1–2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.008

- Miller, A., & Lenzenweger, M. (2012). Schizotypy, social cognition, and interpersonal sensitivity. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3(4), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027955

- Morrison, S. C., & Cohen, A. S. (2014). The moderating effects of perceived intentionality: Exploring the relationships between ideas of reference, paranoia and social anxiety in schizotypy. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 19(6), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2014.931839

- Naughton, M., Dinan, T. G., & Scott, L. V. (2014). Corticotropin-releasing hormone and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in psychiatric disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 124, 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59602-4.00005-8

- Nuechterlein, K. H., & Dawson, M. E. (1984). A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 10(2), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/10.2.300

- Oezgen, M., & Grant, P. (2018). Odd and disorganized–Comparing the factor structure of the three major schizotypy inventories. Psychiatry Research, 267, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.009

- Öhman, A. (1981). Electrodermal activity and vulnerability to schizophrenia: a review. Biological Psychology, 12(2-3), 87–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(81)90008-9

- Owens, M. E., & Beidel, D. C. (2015). Can virtual reality effectively elicit distress associated with social anxiety disorder? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(2), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9454-x

- Pechey, R., & Halligan, P. (2012). Prevalence and correlates of anomalous experiences in a large non-clinical sample. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 85(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02024.x

- Phillips, L., & Seidman, L. (2008). Emotion processing in persons at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(5), 888–903. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn085

- Pisano, S., Catone, G., Pascotto, A., Iuliano, R., Tiano, C., Milone, A., Masi, G., & Gritti, A. (2016). Paranoid thoughts in adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(5), 792–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0612-5

- Premkumar, P., Bream, D., Sapara, A., Fannon, D., Anilkumar, A. P., Kuipers, E., & Kumari, V. (2018a). Pituitary volume reduction in schizophrenia following cognitive behavioural therapy. Schizophrenia Research, 192, 416–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.035

- Premkumar, P., Dunn, A., Onwumere, J., & Kuipers, E. (2019). Perceived criticism and perceived praise predict schizotypy in the non-clinical population: The role of affect and perceived expressed emotion. European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 55, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.10.009

- Premkumar, P., Onwumere, J., Albert, J., Kessel, D., Kumari, V., Kuipers, E., & Carretié, L. (2015). The relation between schizotypy and early attention to rejecting interactions: The influence of neuroticism. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry : The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, 16(8), 587–601. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2015.1073855

- Premkumar, P., Onwumere, J., Betts, L., Kibowski, F., & Kuipers, E. (2018b). Schizotypal traits and their relation to rejection sensitivity in the general population: Their mediation by quality of life, agreeableness and neuroticism. Psychiatry Research, 267, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.002

- Pruessner, M., Béchard-Evans, L., Boekestyn, L., Iyer, S. N., Pruessner, J. C., & Malla, A. K. (2013). Attenuated cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in individuals at ultra-highrisk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 146(1-3), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.019

- Pujol, J., Giménez, M., Ortiz, H., Soriano-Mas, C., López-Solà, M., Farré, M., Deus, J., Merlo-Pich, E., Harrison, B. J., Cardoner, N., Navinés, R., & Martín-Santos, R. (2013). Neural response to the observable self in social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine, 43(4), 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001857

- Ragsdale, K., Mitchell, J., Cassisi, J., & Bedwell, J. (2013). Comorbidity of schizotypy and psychopathy: Skin conductance to affective pictures. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1000–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.027

- Raine, A. (1991). The SPQ: A scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 17(4), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/17.4.555

- Rasia-Filho, A. A. (2006). Is there anything “autonomous” in the nervous system? Advances in Physiology Education, 30(1), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00022.2005

- Rossell, S. L., Chong, D., O'Connor, D. A., & Gleeson, J. F. (2014). An investigation of gender differences in semantic processing in individuals with high schizotypy. Psychiatry Research, 215(2), 491–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.015

- Rozenman, M., Vreeland, A., & Piacentini, J. (2017). Thinking anxious, feeling anxious, or both? Cognitive bias moderates the relationship between anxiety disorder status and sympathetic arousal in youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 45, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.11.004

- Safren, S. A., Heimberg, R. G., Horner, K. J., Juster, H. R., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1999). Factor structure of social fears: The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00003-1

- Sapolsky, R. (2015). Stress and the brain: Individual variability and the inverted-U. Nature Neuroscience, 18(10), 1344–1346. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4109

- Sawyer, C., & Behnke, R. (2002). Reduction in public speaking state anxiety during performance as a function of sensitization processes. Communication Quarterly, 50(1), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370209385649

- Schultze-Lutter, F., Nenadic, I., & Grant, P. (2019). Psychosis and schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorders require early detection on different symptom dimensions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 476. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00476

- Shah, J., Tandon, N., Howard, E., Mermon, D., Miewald, J., Montrose, D., & Keshavan, M. (2015). Pituitary volume and clinical trajectory in young relatives at risk for schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 45(13), 2813–2824. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171500077X

- Shean, G., Bell, E., & Cameron, C. D. (2007). Recognition of nonverbal affect and schizotypy. The Journal of Psychology, 141(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.141.3.281-292

- Singh, J., Capozzoli, M., Dodd, M., & Hope, D. (2015). The effects of social anxiety and state anxiety on visual attention: Testing the Vigilance–Avoidance Hypothesis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(5), 377–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1016447

- Tan, E. J., & Rossell, S. L. (2017). Disorganised schizotypy is selectively associated with poorer semantic processing in non-clinical individuals. Psychiatry Research, 256, 249–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.067

- Tompson, M. C., Asarnow, J. R., Hamilton, E. B., Newell, L. E., & Goldstein, M. J. (1997). Children with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: Thought disorder and communication problems in a family interactional context. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(4), 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01527.x

- Walter, E., Fernandez, F., Snelling, M., & Barkus, E. (2018). Stress induced cortisol release and schizotypy. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 89, 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.01.012

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Weintraub, M., de Mamani, A., Villano, W., Evans, T., Millman, Z., Hooley, J., & Timpano, K. (2019). Affective and physiological reactivity to emotional comments in individuals at elevated risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 206, 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.10.006

- Werre, P. F. (1987). Extraversion–introversion, contingent negative variation and arousal. In J. Strelau, & H. J. Eysenck, Personality dimensions and arousal (pp. 59–75). Plenum Press.

- Yerkes, R., & Dodson, J. (1998). The relation of strength of stimuli to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of comparative neurology and psychology, 18, 459–482.