ABSTRACT

Background/objectives: Major depression has a negative impact on quality of life, increasing the risk of premature death. It imposes social and economic costs on individuals, families and society. Mental illness is now the leading cause globally of disability/lost quality life and premature mortality. Finding cost-effective treatments for depression is a public health priority. We report an economic evaluation of a dietary intervention for treating major depression.

Methods: This economic evaluation drew on the HELFIMED RCT, a 3-month group-based Mediterranean-style diet (MedDiet) intervention (including cooking workshops), against a social group-program for people with major depression. We conducted (i) a cost-utility analysis, utility scores measured at baseline, 3-months and 6-months using the AQoL8D, modelled to 2 years (base case); (ii) a cost-effectiveness analysis, differential cost/case of depression resolved (to normal/mild) measured by the DASS. Differential program costs were calculated from resources use costed in AUD2017. QALYs were discounted at 3.5%pa.

Results: Best estimate differential cost/QALY gain per person, MedDiet relative to social group was AUD2775. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis, varying costs, utility gain, model period found 95% likelihood cost/QALY less than AUD20,000. Estimated cost per additional case of depression resolved, MedDiet group relative to social group was AUD2,225.

Conclusions: A MedDiet group-program for treating major depression was highly cost-effective relative to a social group-program, measured in terms of cost/QALY gain and cost per case of major depression resolved. Supporting access by persons with major depression to group-based dietary programs should be a policy priority. A change to funding will be needed to realise the potential benefits.

Introduction

Depression has a negative impact on quality of life, productivity and relationships, carrying substantial personal, social and economic costs [Citation1]. Worldwide it was estimated in 2010 that mental health disorders cost US$2.5–8.5 trillion, projected to double by 2030 [Citation2]. As a leading cause of disease burden globally, depressive disorders are an urgent public health priority for identifying effective and cost-effective treatments [Citation3,Citation4].

The most common treatments for depression are pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy/counselling. A recent commentary in the Medical Journal of Australia concluded that the available treatments, including antidepressants have proved disappointing in terms of treatment effect [Citation5]. Other high-profile papers report similar conclusions [Citation6]. Despite limited evidence of efficacy and small effect sizes, antidepressant use in Australia has more than doubled between 2000 and 2016 [Citation5]. In 2011, 1.7 million Australians were prescribed antidepressants (9% of 18.9 million aged 16+) [Citation7]. In 2016–2017, 24.77 million scripts for anti-depressant medication were filled at a government cost of just under AUD200 million [Citation8]. The Australian Government also spent AUD1.2 billion on subsidised private clinical mental health services, and State Governments $2.0 billion [Citation8], much of this related to depression as the most common disorder after anxiety.

Evidence is emerging from epidemiological studies that a healthy diet is associated with a lower risk of depression, while an unhealthy diet confers greater risk [Citation9–11]. This relationship is postulated as causal, based on well-defined biological pathways [Citation12]. A causal relationship has been confirmed in recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of dietary intervention as a treatment for depression [Citation13–16]. There is also evidence that persons suffering from depression are likely to have poor quality diets [Citation17].

Policy decisions are increasingly based on a combination of clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness, the latter concerned with ‘value for money’. To date, there has been just one published economic evaluation of a dietary intervention for treating depression, a cost minimisation analysis [Citation18]. A 2005 review identified 58 studies on the cost-effectiveness of treatments for mental illness, but no studies of dietary interventions [Citation19]. A 2015 systematic review of economic evaluations of interventions to prevent or treat mental disorders similarly identified no economic evaluations of nutrition interventions [Citation20].

The aim of the present study was to conduct an economic evaluation, comprising a cost-effectiveness and a cost-utility analysis of a dietary intervention for treating major depression based on the HELFIMED RCT.

HELFIMED recruited adults with major depression [Citation21], based on a depression diagnosis or at least moderate depressive symptoms for two+ months based on the depression subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale DASS-21 [Citation22]. At baseline, over 80% of eligible participants reported depressive symptoms in the ‘extremely severe’ category. The study aim was to test the effectiveness of a group-based dietary intervention in the treatment of depression.

Participants were randomly allocated to a dietary group-program or a social group-program. Dietary arm participants received a nutrition education workshop based on the Mediterranean-style diet (MedDiet), run by dietitians and nutritionists, followed by fortnightly group cooking workshops for 3 months, where they also received food hampers and fish oil supplements. The comparator group attended fortnightly social groups for 3 months. As described elsewhere [Citation13], participants were led through a range of social activities (such as book club, games, completing personality questionnaires), and were supplied with ‘nibbles’ (such as biscuits and cheese). As peer support in a group setting has been found to be as effective as psychotherapy for alleviating depressive symptoms [Citation23], the comparator constitutes an alternative treatment arm.

The HELFIMED study protocol describing recruitment strategy, diet and social group conditions and measured outcomes has been published elsewhere [Citation21]. Outcomes were measured at 3-months (end of intervention) and at 6-months (3-month post – trial follow-up). Trial participants were advised to continue current therapies and requested not to start any new treatments. Participants who had recently commenced a treatment had their baseline assessment delayed by one month. Any participants who commenced a new treatment after trial enrolment (n = 5) was excluded from outcome assessment [Citation13,Citation21].

Both the MedDiet and social groups showed significantly improved depressive symptoms at three-months compared to baseline, with significantly greater improvement in the MedDiet group [Citation13]. Improved depressive symptoms and other mental health outcomes (anxiety, stress and mental health-related quality of life) were correlated with improved diet, measured by change in ‘Mediterranean diet score’, and increased consumption of vegetables, legumes, nuts and fruit. (The validated measurement tools are described in the HELFIMED study protocol [Citation21].) Improvements in diet and mental health observed at 3 months were maintained at the six-month follow up in both groups.

The tasks of the economic evaluation were to estimate; (1) mean per person cost of the MedDiet and Social intervention; (2) differential cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gain MedDiet relative to the social group; (3) differential cost per case of depression successfully treated (resolved from moderate/severe/extreme to mild/not depressed) ().

Table 1. Disease severity at baseline and at 6-months, number and per cent. Intention to treat* HELFIMED RCT.

Methods

A cost-effectiveness analysis and cost-utility analysis (cost/QALY) were conducted drawing on outcomes and costs from the HELFIMED RCT. A limited societal perspective is taken, with scope restricted to intervention costs and health outcomes of trial participants.

The cost-utility analysis adopts a 24-month time-frame. Results are modelled to 24 months assuming maintenance of effect observed between 3 months (trial end) and 6 months (trail follow-up). In the MedDiet group, diet quality, depression status and quality of life scores were slightly improved between trial end and at 6-months [Citation13], supporting the expectation of long-term improvement. This is consistent with the many studies that report maintenance of diet change and clinical outcomes in MedDiet interventions well beyond intervention end – some followed up to 5 years [Citation24,Citation25]. Long term, maintenance of social group gains is less certain (a slight loss of effect was observed between 3 and 6 months), but is adopted as a conservative assumption (for differential benefit of the MedDiet).

Remission of depression into the mild or normal range (DASS-21 score <14), from extremely severe, severe, or moderate depression (DASS-21 scores of 28+, 21–27 and 14–20, respectively) was used for the cost-effectiveness analysis, defined by the differential percent of the MedDiet and social group cohorts achieving remission against baseline. Missing data was conservatively incorporated as last measure carried forward.

Health effects were restricted to the impact on depression status and quality of life. The possible wider impacts of a dietary intervention on comorbid chronic conditions common in persons with depression, or on treatment costs, were not modelled. Excluding potential clinical benefits and missing likely cost savings [Citation18] will yield a conservative estimate of ‘value for money’.

Quality of life utility scores were generated from the Assessment of Quality of Life, AQoL-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. This was administered to participants at baseline, 3 and 6 months, and scored using the published algorithm (www.aqol.com). The AQoL 8D was developed in Australia and has excellent coverage of physical, social, emotional and role aspects of health. The algorithm for translating responses into utility scores was developed from an Australian community and clinic sample, using the gold standard time-trade-off (TTO) technique. The AQoL 8D utility scores sit between −0.04 and 1.0, where 1 is full health, 0 equivalent to death, negative values for states worse than death. The scale is characterised by equal interval properties and an equivalence with loss of life. (An improvement in AQoL score from say 0.4 to 0.65 for 2 years = 0.5 QALYs is equivalent to living an extra 6 months (0.5 years.))

Mean utility scores were calculated from all data collected at baseline, 3 and 6 months using a generalised estimating equation to account for missing data at follow-up. No significant difference was observed in mean utility scores at baseline between the MedDiet and Social groups (p = 0.567), which approached significance at 3 months (p = 0.089) and was significant at 6 months (p = 0.041).

QALY gain (loss) was generated as the product of change in utility score and time in health state in years (area under the curve). Incremental QALY gain between the MedDiet and Social groups is the difference of differences in QALY gain from base-line to end model time-frame.

The three-month intervention was costed by describing the resources used in program delivery for the MedDiet group and the social group and applying 2017 unit-costs in Australian dollars (AUD). Labour costs were based on published awards for pertinent professions (plus wage on-costs @20%), food costs were taken from ‘Coles on-line’ mid-price range. Costs incurred for the trial that would not be included in normal clinical delivery setting (e.g. for evaluation) were identified and excluded.

The incremental cost per differential QALY gain and incremental cost per differential change in depression status are the quotient of the differential costs and outcomes.

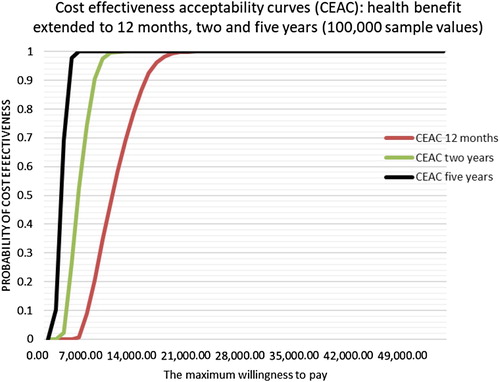

Sensitivity analysis was conducted adjusting the three parameters: (i) program cost – low bound excluding fish oil supplements [Citation13], upper bound adding 25% to best-estimate), (ii) quality of life utility gain – assuming a normal distribution, described by the mean and confidence limits and, (iii) period over which benefits were modelled – 12 months, 2 years or 5 years. (5 years is a plausible upper-bound for the MedDiet intervention given excellent effect maintenance between 3 and 6 months and studies reporting good adherence to 5 years with MedDiet interventions [Citation24,Citation25].)

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed on 100,000 generated cases using Microsoft Excel 2016. The utility function followed a beta function with the parameters alpha and beta defined from the mean and the standard deviation of the sample.

Cost followed a random function taking the value between the lower bound and the maximum bound of the cost of the program. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves generated when the health benefits of the program were hypothetically extended for 6 months, two years and five years and for the maximum willingness to pay varying from zero to AUD50,000. Future health benefits were discounted at 0.035% [Citation26]. (Costs were incurred only in year 1 so were not discounted.)

Results

Program costs

Program costs are summarised in , covering the 75 MedDiet and 77 social group participants, with more detail in Annex 1. Both group programs were inexpensive to deliver at an estimated mean per participant cost of AUD411 and AUD195 for the MedDiet/cooking workshop group and Social group respectively, based on 6 workshops per program with 8–10 attendees per group. All costs are expressed in AUD2017. Fish oil supplements add AUD91 per head to the diet group, for a cost differential between the MedDiet and social group of AUD307 per person (or AUD216 excluding the supplements). Costs for recruiting participants are not included, which would be similar across study arms and excluded as referrals are a normal part of clinical practice.

Table 2. Summary of costs of MedDiet and social group HELFIMED (a) AUD 2017.

Cost utility analysis (Cost per QALY gain)

The mean quality of life utility scores derived at baseline, 3 and 6 months are reported in . Mean utility scores improved between baseline and 3 months in both groups, from very low levels of 0.462 and 0.445 increasing to a mean of 0.648 in the MedDiet group and 0.586 in the social group at 3 months. Mean utility scores were maintained at 6 months, at 0.660 in the MedDiet group (a further small increase) and 0.583 in the social group (a small reduction). The gain in mean utility scores from baseline in both groups was considerable. The differential gain in mean utility scores at 6 months was 0.06 in favour of the MedDiet group, while small, it is clinically relevant. A threshold change in utility score of 0.03 is considered discernible [Citation27]. It is notable that the standard errors on these estimates are low.

Table 3. Mean (95% CI) AQoL-8D utility scores at baseline, 3 and 6 months. HELFIMED RCT (Generalised estimating equation).

The mean differential QALY gain, MedDiet group relative to the social group modelled out to 2 years, (area under the curve, assuming mean utility scores at 6 months maintained to 24 months) is 0.1106 QALYs per person. See . The estimated incremental cost per QALY gain, MedDiet compared with Social group program over 2 years is $2776 ($307 ÷ 0.1106). See .

Table 4. Differential QALY gain and cost per differential QALY gain MedDiet vs. social group – Effect of model time-frame for health benefit.

Sensitivity analysis – cost-utility analysis

Extending the health benefit to 5 years, the mean differential cost/QALY is just over $1000/QALY gain, while reducing the health benefit period increases the cost per QALY gain. The result of the sensitivity analysis on 100,000 sample values are displayed in , drawing on the range of parameter values in . Willingness to pay (WTP) for a QALY in Australia was over AUD40,000 over a decade ago [Citation27], suggesting the MedDiet intervention is almost certainly cost-effective under almost all plausible scenarios even if WTP for a QALY was < AUD15,000.

Table 5. Attributes incorporated into probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

We estimated the cost per case of depression successfully treated at 6-month follow-up. Successful treatment is classed as moving from extreme, severe or moderate depression, into the mild or normal range. The percent of persons who moved into the mild/normal range at 6 months was significantly greater in the MedDiet group, a 29.4 percentage point increase, than in the social group a 15.6 percent point increase. That is, the MedDiet group achieved a nearly doubling of cases resolved into the normal or mild category. See . This equates to an incremental cost per additional case of depression successfully treated of AUD 2,225 {307÷ (29.4–15.6)}. Given improved outcomes at 3 months in the MedDiet group were still observed at 6 months (3 months after the intervention ceased), good maintenance of outcome is indicated.

Discussion

This economic evaluation finds a group-based MedDiet intervention, involving a combination of dietary advice, cooking workshops/social eating and food hampers for the treatment of major depression represents an exceptionally good societal investment. The best-estimate cost per QALY of AUD2773 can be compared with an observed threshold for the listing of prescription medications on the Australian Pharmaceutical Befits Schedule of around AUD 42,000/QALY [Citation28], below which listing is almost certain, given good quality (e.g. RCT) evidence. It is also exceptional value relative to accepted societal norms for valuing a ‘life year’, essentially what a QALY is. A recent Australian study [Citation29], based on government spending pertinent to health across modalities and sectors, estimated a mean cost to ‘buy a QALY’ of $28,000. HELFIMED, as a treatment for major depression, compares favourably, offering exceptional value for society.

The estimated differential cost per case of depression resolved at AUD2227 further confirms the value of the group MedDiet intervention for the treatment of major depression. The impact of depression on quality of life is massive. It is larger than almost any other condition, affecting almost all aspects of a person’s life and often family, friends and work colleagues. The severity of major depression is underlined by the extremely low baseline utility scores of 0.45, compared with a societal norm of 0.786 (AQoL 8D persons aged 25–54) [Citation30]. Such low utility scores are consistent with the known high suicide risk associated with major depression. Depression also involves considerable cost to the health system, and the economy through unemployment, underemployment and welfare dependency.

Our results are highly concordant with the clinical outcomes [Citation16], and economic evaluation results [Citation18], of the SMILES trial – an RCT in persons with major depression, comparing a MedDiet intervention (delivered through individual dietetic consults) with a ‘befriending condition’ control. A large and significant improvement in depression symptoms was reported, and significantly lower health system and societal costs (work days lost) in the diet group, compared with the control group. The MedDiet intervention was dominant, reducing costs while yielding a large and significant improvement in depression outcomes. Both these studies confirm previous research that has found allied health are often highly cost-effective [Citation31].

Study limitations

The economic analysis builds on the results of a high quality randomised control trial, published in Nutritional Neuroscience. But loss to follow-up (F-U), expected in a study of persons with depression, did occur, which was larger in the social group than the MedDiet group. As reported by Parletta and colleagues [Citation13], there were no significant differences between those who completed all assessments and those who were lost to follow up. The statistical analysis for generating utility values, using the generalised estimating equation, factored in all available cases, while the estimated change in depression classification used last reading carried forward.

The 3-month post intervention follow-up (that is the 6-month data collection point) was helpful in ascertaining possible maintenance of benefit, but even longer follow-up would have been desirable. We note few drug trials report even 3 months of follow-up.

The documented improvement in diet is likely to confer a range of additional health benefits, especially for cardiometabolic health, adding to health benefits and reducing health care costs [Citation32]. This would be expected to be considerable given high rates of comorbidity in people with depression. As noted, this was indeed the finding for the SMILES trial economic evaluation, which did measure health system costs [Citation17]. In the HELFIMED study, health system costs (other than program delivery) were not measured, nor time off work (or performing other roles), due to depression. Thus, potential cost savings may have been missed.

This contrasts with studies of antidepressant medications, which carry considerable adverse side effect profiles that are rarely adequately costed into economic analyses. And post marketing analyses of drugs invariably find side effect profiles considerably worse than those reported in clinical trials [Citation33].

The social group comparator is an active intervention, with social support reported as effective as psychotherapy in treating depression [Citation22], thus relative to ‘treatment as usual’ MedDiet group benefits would be expected to be larger. To illustrate, the utility gain from baseline was 0.2, which would generate a more favourable cost/QALY estimate and the cases of depression resolved was 29.4% point.

While fish oil supplements were provided to the MedDiet group and have been included in the ‘best-estimate’ cost, as the blood omega-3 analysis showed no correlation with depression outcomes [Citation13], it was considered to have no impact on outcomes. Fish oil supplementation is not recommended as part of community roll-out. In the sensitivity analysis, the lower cost bound excluded fish oil supplements.

Conclusions

Access to a group MedDiet program involving dietary advice, cooking workshops/social eating for persons with major depression was found to offer a good return on investment for society. A group dietary intervention can be viewed as a comprehensive approach to treating depression, comprising the social contact of group cooking and shared meals with added therapeutic benefits from a healthy diet, creation of skills and confidence in participants building capacity for long-term change.

Facilitating attendance at group diet/cooking program for persons with diagnosed depression is desirable. Funding under universal health insurance plans, such as Australia’s Medicare, the UK National Health Service or US Medicaid is critical. This would support better health of persons suffering from depression, but potentially also reduce health care and other costs (such as disability pensions) and contribute to gross production, through likely lower unemployment and ‘presenteeism’.

Given the community recruitment strategy and minimal exclusion criteria, the results are likely generalisable to other adults experiencing depression in Australia and elsewhere. Given the high and increasing burden posed by depression and limited efficacy of current treatments, the findings of this study offer new hope to many.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes on contributors

Professor Leonie Segal has a Ph.D. in Economics and has held the Foundation Chair Health Economics and Social Policy at the University of South Australia since 2007. The purpose of her research is to improve the life chances of society’s most vulnerable populations. This is pursued through cutting edge research working in partnership with clinicians, service providers and government to conduct policy-driven research to achieve evidence informed policy and practice. Economic evaluation alongside clinical trials forms a core part of her work. Segal has a record of >120 economic evaluations, covering all health modalities, especially life-style interventions. Her published cost–utility (C-U) analysis of 10 nutrition interventions in 2007 was the largest study of its kind and still represents a major contribution to the literature on the economic performance of dietary interventions. She has also published on nutrition policy to support desired changes in citizen and clinician behaviour.

Dr Asterie Twizeyemariya has a Ph.D. in Economics. Her research interests include using methods such as economic evaluation, economic modelling, policy analysis, statistical analysis, evidence synthesis, research translation and uptake, budgeting, planning, and self-management to learn about behaviour and risk factors that affect individuals and to estimate population health outcomes.

Dr Dorota Zarnowiecki has a Ph.D. in Nutrition and is currently at Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia. As a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of South Australia, she was on a team led by Dr Natalie Parletta to extend the group diet HELFIMED program for including Mediterranean-style diets into rehabilitation programs with people who have mental illness in a randomised controlled trial to people suffering depression (now published: https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320).

Dr Theo Niyonsenga is Associate Professor in the Centre for Research and Action in Public Health, University of Canberra. He has a Ph.D. in Mathematical Statistics and more than 20 years of experience in statistical data analysis and consulting. His interests are in developing and applying statistical methodology to collaborative health research focusing on various areas of Biostatistics in general (e.g. generalized linear models, survival analysis) and in particular on spatial statistics with applications to spatial epidemiology, multivariate data analysis methods (such as structural equations modelling) as well as both growth curve hierarchical data modelling. His research interests include quantitative research within spatial epidemiology and evaluation research (hierarchical growth models and spatial clustering models) and environmental and social determinants of health.

Dr Svetlana Bogomolova is Associate Professor and Senior Marketing Scientist at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science at the University of South Australia. Her research interests include consumer food choices in a supermarket and the influence of price promotions, in-store signage, packaging, nutrition, region-of-origin labelling and other elements of the shopping environment on shopper decisions. Her current projects focus on healthiness of food choices and support for locally produced foods. This work advances important emerging cross-disciplinary areas of Health Marketing and Social Marketing.

Amy Wilson is a research associate at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, University of South Australia and a Ph.D. candidate in Marketing. Her cross-disciplinary research combines theory and research from Marketing, Social Marketing, Behavioural Economics and Nutrition to encourage consumers to engage in healthier behaviours.

Dr Kerin O'Dea is Emeritus Professor: Nutrition and Population Health in the School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia. As a scientist, she has made major contributions to understanding the relationship between diet and chronic diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes and CVD. She is probably best known for her novel research on the marked beneficial health impact of temporary reversion to traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle on diabetes and associated conditions in Australian Aborigines. This led to a strong research interest in the therapeutic potential of traditional diets and lifestyles.

Dr Natalie Parletta is an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the University of South Australia, nutritionist and freelance science writer. She has a PhD, Bachelor of Psychology (first-class Honours) and a Master of Dietetics. For more than 10 years she has researched links between nutrition and mental health, parental influences on child and adolescent diets and benefits of the Mediterranean diet for heart and mental health. Dr Parletta developed a group diet program (HELFIMED) for including Mediterranean-style diets into rehabilitation programs with people who have mental illness, in collaboration with Outer South Mental Health, Southern Adelaide Local Health Network. With postdoctoral research fellow Dorota Zarnowiecki, her team extended this program in a randomised controlled trial to people suffering depression (now published: https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:171–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2

- Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547

- Cuijpers P, Beekman ATF, Reynolds CF. Preventing depression: a global priority. JAMA. 2012;307:1033–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.271

- Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:415–24. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4

- Davey CG, Chanen AM. The unfulfilled promise of the antidepressant medications. Med J Aust. 2016;204:348–50. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00194

- Kirsch I, Moore TJ, Scoboria A, Nicholls S. The Emperor's new drugs: an analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. Preven Treat. 2002;5:23.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 4329.0.00.003 – Patterns of use of mental health services and prescription medications, 2011. Canberra, ACT: ABS; 2016.

- Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. Mental health services in Australia. [Cited July 18, 2018]. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/summary.

- Lai JS, Hiles S, Bisquera A, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Attia J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:181–97. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.069880

- Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, Sergentanis IN, Kosti R, Scarmeas N. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:580–91. doi: 10.1002/ana.23944

- Sanchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Alonso A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1090–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.129

- Parletta N, Milte C, Meyer B. Nutritional modulation of cognitive function and mental health. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24(5):725–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.01.002

- Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, Wilson A, Bogomolova S, Villani A, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diets and mental health in people with depression: a 6 month randomised controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci. 2017. DOI:10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320. [online ahead of print].

- Sanchez-Villegas A, Martínez-Gonzalez MA, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Covas M-I, et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression: the PREDIMED randomized trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:208.

- Stahl ST, Albert SM, Dew MA, Lockovich MH, Reynolds CF. Coaching in healthy dietary practices in at-risk older adults: a case of indicated depression prevention. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:499–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101373

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med. 2017;15(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

- Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:408–13. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058925

- Chatterton ML, Mihalopoulos C, O’Neil A, Itsiopoulos C, Opie R, Castle D, et al. Economic evaluation of a dietary intervention for adults with major depression (the “SMILES” trial). BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):599. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5504-8

- Barrett B, Byford S, Knapp M. Evidence of cost-effective treatments for depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2005;84(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.10.003

- Mihalopoulos C, Chatterton ML. Economic evaluations of interventions designed to prevent mental disorders: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9(2):85–92. doi: 10.1111/eip.12156

- Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, Wilson AM, Bogomolova S, Villani A, Itsiopoulos C, et al. A 6-month randomised controlled trial investigating effects of Mediterranean-style diet and fish oil supplementation on dietary behaviour change, mental and cardiometabolic health and health-related quality of life in adults with depression (HELFIMED): study protocol. BMC Nutr. 2016;2:52.

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(2):227–39. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657

- Pfeiffer PN, Heisler M, Piette JD, Rogers MAM, Valenstein M. Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: a meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.002

- de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin J-L, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99(6):779–85. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.6.779

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas M-I, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):1279–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: NICE; 2013.

- Gerhards SAH, Huibers MJH, Theunissen KATM, de Graaf LE, Widdershoven GAM, Evers SMAA. The responsiveness of quality of life utilities to change in depression: a comparison of instruments (SF-6D, EQ(5D), and DFD). Value Health. 2011;14(5):732–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.12.004

- George B, Harris A, Mitchell A. Cost-effectiveness and the consistency of decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19(11):1103–9. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119110-00004

- Edney LC, Haji Ali Afzali H, Cheng TC, Karnon J. Estimating the reference incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for the Australian health system. PharmacoEconomics. 2018;36(2):239–52. doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0585-2

- Maxwell A, Özmen M, Iezzi A, Richardson J. Deriving population norms for the AQoL-6D and AQoL-8D multi-attribute utility instruments from web-based data. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(12):3209–19. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1337-z

- Dalziel K, Segal L, Mortimer D. Review of Australian health economic evaluation - 245 interventions: what can we say about cost-effectiveness? Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2008;6:9.

- Dalziel K, Segal L. Time to give nutrition interventions a higher profile: cost-effectiveness of 10 nutrition interventions. Health Promot Int. 2007;22(4):271–83. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam027

- Khawam EA, Laurencic G, Malone DA. Side effects of antidepressants: an overview. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73(4):351–61. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.4.351

Appendix

Costs of delivery HELFIMED Med-diet and social group (a) AUD 2017.

(a) number of groups – Costs based on a 6-session programs (diet or social group) with 8–10 people per group. 50 workshops were run in each study arm, to deliver the program to 77 persons enrolled in the diet and social groups respectively. There were in addition 5 Introductory diet education workshops for the diet group.

(b) Wage rate includes 20% wage on-costs – for dietitians the rates it is based on published median hourly rate of $37.80 /hour (adding 20% wage-on-costs http://www.payscale.com/research/AU/Job=Dietitian/Salary (accessed March 2018)).

(c) http://www.cookingspace.com.au/index.php/rates; http://cdch.org.au/halls-for-hire/commercial-kitchen/large-kitchen/ Thursday, 6 December 2018 www.booktocook.com.au/

(d) Recommendation was 2capsules 3times per day for 6 months – @ $43.19 per 120 capsules = $129.57 per person; assuming 70% compliance (based on costs from Coles On-line) costed at $91.