ABSTRACT

Background

There is substantial evidence supporting that remote interventions are useful to change dietary habits. However, the effect of a remote intervention based on Mediterranean diet (MD) in depressive patients has been less explored.

Objective

This study aims to assess the effectiveness of a remotely provided Mediterranean diet-based nutritional intervention in the context of a secondary prevention trial of depression.

Methods

The PREDIDEP study was a 2-year multicenter, randomized, single-blinded trial designed to assess the effect of the MD enriched with extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) on the prevention of depression recurrence. The intervention group received usual care for depressed patients and remote nutritional intervention every three months which included phone contacts and web-based interventions; and the control group, usual care. At baseline and at 1-year and 2-year follow-up, the 14-item MD Adherence Screener (MEDAS) questionnaire and a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) were collected by a dietitian. Mixed effects linear models were used to assess changes in nutritional variables according to the group of intervention. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03081065.

Results

Compared with control group, the MD intervention group showed more adherence to MD (between-group difference: 2.76; 95% CI 2.13–3.39; p < 0.001); and a healthier diet pattern with a significant increase in the consumption of olive oil (p < 0.001), and a significant reduction in refined cereals (p = 0.031) after 2 years of intervention.

Conclusions

The remote nutritional intervention increases adherence to the MD among recovered depression patients.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03081065.

Introduction

Unipolar depression is a growing global Public Health challenge. It is estimated that unipolar depression will be one of the most important causes of global burden of disease by 2030 [Citation1]. In recent years, life factors such as diet, have been identified as a target for the development of adjunctive treatment that could help reduce the current relapse rates of depression [Citation2]. One of the dietary factors that has been inversely most associated with depression is the adherence to the Mediterranean Diet (MD) [Citation3–6].

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis have showed that online interventions targeted in lifestyle behaviour changes can significantly reduce depressive symptoms [Citation7]. It is important to highlight My food & Mood study [Citation8], which showed that dietary changes were associated with reduced depressive symptoms when a dietary intervention delivered via smartphone application was applied.

As far as we know, no previous study has assessed the effect of a 2-year MD intervention for the prevention of relapses of depression. The PREDIDEP study was an ongoing secondary prevention trial aimed at assessing the effect of an MD enriched with extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) on depression recurrence [Citation9]. The novelty of this trial is that dietitians conduct the nutritional intervention remotely in coordination with the face-to-face intervention conducted by the psychiatrists and health care team. The principal objective of this study was to assess the effect of a remote intervention in obtaining favourable dietary changes in the context of the PREDIDEP trial.

Methods

Overview of the PREDIDEP study

The PREDIDEP study was a multicentre, randomized, controlled, single-blind trial for 2 years. The study design and methodology have been previously described [Citation9]. Briefly, study participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups (Mediterranean diet or control) once their data are included in a centralized data management system by the specialists. Various stratification factors are considered for the randomization, sex, age group (<65 years or ≥ 65 years), and recruitment centre. At baseline, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are blinded to the allocation of the participants, following the CONSORT guidelines for randomized trials to prevent selection biases.

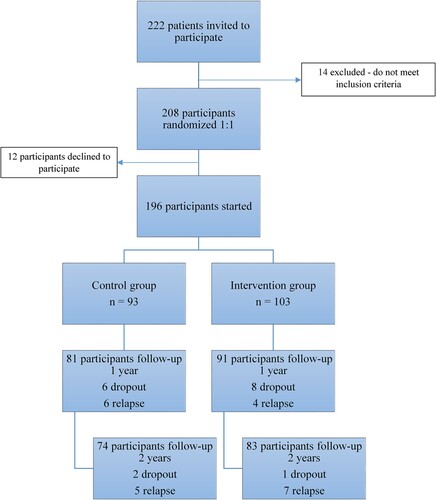

The flowchart () shows participants who completed 1- or 2-year follow-up. Two hundred and twenty-two patients were invited to participate in the study. Fourteen patients did not meet the inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded. Two hundred and eight patients were finally recruited and randomized, and after 12 patients declined to participate, a total of 196 individuals started the intervention. Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention (MD enriched with EVOO) or the control group (standard clinical care). The number of dropouts was 17, and the retention rate was 92.9% among participants with follow-up over 12 months (182/196), and 91.3% at 24 months (179/196).

The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (reference NCT03081065). The Research Ethics Committees from each recruitment centre approved the protocol. All participants provided written informed consent after they received the information sheet and additional verbal explanation.

Remote nutritional intervention

The aim of our study was to assess the effectiveness of a remotely provided Mediterranean diet–based nutritional intervention in the context of a secondary prevention trial of depression. The MD is characterized by the use of EVOO for all culinary purposes and high consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, and nuts; moderate consumption of fish; and very low consumption of red and processed meats, refined grains, sweet desserts, and whole-fat dairy products and ultra-processed foods [Citation3].

Specifically, the dietary recommendations for the intervention group were the use of 4 or more tablespoons of EVOO per day; consumption of 2 or more servings of vegetables per day; 3 or more servings of fruits per day; 3 or more servings of legumes per week; 3 or more servings of fish or seafood per week; 3 or more servings of nuts per week; selected white meats instead of red or processed meats; regularly cooking with sauce made with minced tomato, garlic, and onion simmered in olive oil (sofrito); selected whole grain cereals instead of refined cereals; eliminate or limit the consumption of cream, butter, and margarine, carbonated and/or sweetened beverages, commercial bakery products, and ultra-processed foods.

The intervention began with a phone call from the dietitian who collected information about lifestyle, nutrition, and quality of life [Citation10–12]. Those participants in the control group received only general information about the study and they were called every year of follow-up to collect further information. Every 3 months during the 2-year follow-up, participants in the intervention group were contacted by the dietitian by phone to complete the MEDAS questionnaire and to conduct the personalized nutritional education session [Citation12].

Participants in the control group had access to general information on the website; for participants in the intervention group, the content was divided into five areas. Recommended foods encompassed 53 typical foods, with an overview of the food including a definition, portion size, frequency of consumption, nutritional value, health benefits, and examples of how to include it in the diet. The Menus area included a week eating plan and recommended frequency of consumption. The area News and Online resources included 71 news items, 7 web pages, blogs, and web-based tools. Practical tips used graphic images to calculate the hand-based portion size of food groups, and to identify the seasonality of food, guide healthy food shopping, how to eat healthy food outside, and the benefits of eating in family. The Mediterranean diet classroom area consisted of 24 videos related to theoretical aspects of nutrition, and 12 videos with practical tips.

Intervention group participants also received a book about the traditional MD [Citation13], binders with print modules with the information of the website and 0.5 L of EVOO per week for free.

Dietary assessment

MEDAS questionnaire [Citation12] was used to assess the level of compliance with the intervention and to evaluate MD adherence. This instrument comprised of 14 questions regarding the main groups of food consumed as part of the MD and was validated against a 136-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). The 14-item MEDAS questionnaire was indicated to be a moderate and reasonably valid tool for the rapid estimation of MD adherence. Its scores range from 0 to 14. Dietary intake was analysed through a 147-item semiquantitative FFQ validated in Spain [Citation10], and energy and nutrient intakes were calculated from Spanish food composition tables [Citation14].

For the present analysis, changes in food consumption were assessed for 12 food groups: vegetables, fruits, refined cereals, whole grain cereals, pulses, nuts, white fish, fatty fish, white meat, red meat, olive oil, and red wine; and 10 nutrients: total fat, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), saturated fatty acids (SFAs), trans fatty acids, omega-3, magnesium, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and folic acid.

In addition, the Provegetarian Dietary Pattern (PDP) or preference for plant-derived foods but not exclusion of animal foods [Citation15], was also evaluated. To build the PDP the consumption of seven food groups from plant origin and 5 food groups from animal origin was adjusted for total energy intake by using the residual method proposed by Willett [Citation16].

Statistical analysis

We used the PREDIDEP database including 1- and 2-year follow-up data. The analysis was performed by protocol with participants with complete information available. Quantitative variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs), whereas categorical variables were described as number and percentages (n [%]). The Student t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables were applied to test differences in baseline characteristics between the intervention groups. Mixed effects linear models were used to assess changes in nutritional variables from baseline to 12- and 24-month follow-up visits. A 2-level mixed linear model with random intercepts at the recruitment centre and participant was fitted. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA (v 12.0, StataCorp LP). The significance level (2-tailed) was set at p-values lower than 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among 157 patients which completed the intervention, 70.06% were women with a mean age of 51.15 years (SD 13.74). shows the demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle baseline characteristics of participants according to the randomized groups. Intervention group showed an increased protein intake. No other significant differences between intervention groups were found.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of PREDIDEP participants (n = 157).

Mediterranean diet adherence

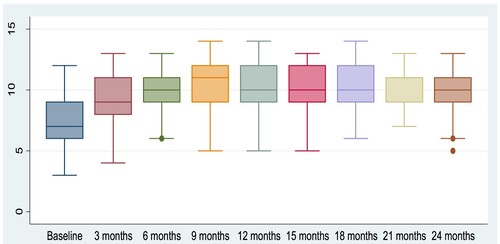

After 12 and 24 months of follow-up, a significant increase in adherence to the MD was observed in the intervention group. The mean (95% CI) MEDAS score was 7.2 (6.73–7.67) at baseline, 9.91 (9.44–10.38) at 12 months (increase 2.71 [2.06–3.36]) and 9.79 (9.34–10.25) at 24 months (increase 2.59 [1.95–3.23]) in the intervention group.

In the control group, the mean observed was 6.83 (6.28–7.38) at baseline, 7.13 (6.68–7.58) at 12 months (increase 0.3 [−0.99 to 0.39]) and 7.03 (6.59–7.47) at 24 months (increase 0.2 [−0.88 to 0.48]). Accordingly, no significant increment in adherence was observed for this group.

The increase in MD adherence was higher in the intervention than in the control group at 12 months (between-group difference 2.77, 95% CI 2.12–3.43, p < 0.001) and at 24 months of follow-up (between-group difference 2.76, 95% CI 2.13–3.39; p < 0.001).

shows the adherence to the MD for each 3-month follow-up visit among participants of the intervention group. The median score of the adherence to the MD increased gradually until the 9-month follow-up visit. After that, the median adherence was maintained until the last follow-up phone call.

Food group consumption

After one year of intervention, the intervention group showed an increased consumption of nuts = 53.58 (8.10–99.06) (). However, no significant changes were observed in olive oil, pulses, and whole grains consumption in the intervention group. A significant reduction in the consumption of these food items was observed in the control group after 1 year. The intervention group reduced the consumption of refined cereals, red meat, and sweets after 1year of follow-up, but these reductions were also observed for the control groups; so, no significant differences were found between groups.

Table 2. Baseline food groups consumption and changes by randomized treatment group at 12- and 24-month follow-up visits of PREDIDEP participants (n = 157).

After 2 years of intervention, a significant increment in olive oil consumption was observed for the group assigned to the MD = 8.45 (3.99–12.91) with no changes in the control group [between groups difference = 15.07 (8.96–21.19)] Furthermore, a significant reduction in the consumption of fruits, whole grains, nuts, and white meat was observed in the control group after 2 years of follow-up with no significant changes for the intervention group although differences between both groups were only significant for fruits [between groups difference = 92.3 (14.21–-170.4)] and nuts [between groups difference = 67.56 (21.17–113.95)]. Although both groups reduced similarly the consumption of several unhealthy products such as red meat and sweets, the reduction in the consumption of refined cereals was higher in the intervention group after 2 years of follow-up [between groups difference = −36.31 (−69.37 to −3.24)]. Both groups showed a lower vegetable and legume consumption after 2 years of follow-up.

Energy and nutrient intake

All the subjects of the trial reduced their energy intake during the follow-up. However, although a significant decrease in MUFA and omega-3 fatty acids intake was observed for the control group, we failed to find significant changes in these fats among participants assigned to the MD group. Between-group difference was 0.22 (0.04–0.40) for omega-3 fatty acids intake and 9.18 (3.11–15.25) for MUFA intake after one year of follow-up; and 13.54 (7.73–19.35) for MUFA intake after 2 years of follow-up ().

Table 3. Baseline nutrient intake and changes by randomized treatment group at 12- and 24-month follow-up visits of PREDIDEP participants (n = 157).

Moreover, although both groups reduced their intake of trans fatty acids during the follow-up this decrease was higher among participants in the MD group. Regarding several micronutrients such as magnesium and several B-group vitamins such as B6 vitamin or folic acid it is important to highlight that although both groups decrease their intake after 2 years, this decrease was more pronounced in the control group.

Dietary patterns adherence

As intended, the MD intervention group showed a significant improvement in the adherence to MD pattern analysed by MEDAS at 1 and 2 years of follow-up when compared with the control group. In addition, there were no significant differences between groups for PDP ().

Table 4. Baseline dietary patterns adherence and changes by randomized treatment group at 12- and 24-month follow-up visits of PREDIDEP participants (n = 157).

Discussion

Principal findings

This trial is, to our knowledge, the first multiprofessional intervention study which has assessed [open-strick]the effect of an MD intervention enriched with EVOO on preventing recurrences of depression[close-strick] the effectiveness of an MD intervention enriched with EVOO with personalized nutritional information through different remote access routes, in coordination with the face-to-face intervention conducted by psychiatrists and psychologists.

Participants’ baseline scores were similar and showed that they had a reasonably good Mediterranean-style food pattern. In general, our results showed an important reduction in healthy products intake in control group, such as fruits, whole grains, nuts, and white meat. Moreover, it seems that intervention group also reduced some healthy products intake, such as vegetables and pulses, but to a lesser extent than in control group. These results are according to depressed patients’ tendency to deteriorate eating habits. However, we also found refined cereals intake reductions in both groups, more marked in the intervention group. It seems that the intervention with Mediterranean diet enriched with EVOO did not show great changes in food group consumption but allowed maintaining the intake of healthy products in the intervention group.

Comparison with prior work

On one hand, the nutritional interventions are classically made face-to-face. However, in recent years, e-Health or ‘internet medicine’ are becoming more frequent [Citation17]. This remote consultation and telemedicine have especially increased during the last year due to COVID-19 pandemic showing promising results [Citation18]. Using the internet or smartphone technology to deliver interventions for behaviour change in mental health has been seen as an advantageous way to intertwine self-management and/or treatment into daily activities. A recent systematic review established the efficacy of online lifestyle interventions and its potential to improve depressive symptoms when targeting lifestyle behaviour change [Citation7]. To increase the effectiveness of remote interventions, it is recommended to use multiple styles of communication and techniques based on the theory of planned behaviour [Citation19]. For these reasons, we used different behavioural change strategies and remote tools such as phone calls and web page notifications. Moreover, we also used printed resources to overcome potential barriers to internet access, especially among older participants.

On the other hand, there is substantial observational evidence supporting the relationship between high adherence to MD and low risk for depression [Citation3,Citation4,Citation20–22]. Furthermore, intervention studies and trials [Citation5,Citation6,Citation23] have shown that improving diet quality leads to reduced depressive symptoms. Regarding remote nutritional interventions based on the MD carried out among depressed patients, it is worth to mention two randomized, controlled trials that obtained positive results [Citation5,Citation6]. Firstly, the SMILES trial, an adjunctive dietary improvement face-to-face 12-week programme for the treatment of moderate to severe major depression including 166 participants [Citation5]. Secondly, the HELFIMED study, with 152 participants, which tested a face-to-face MD intervention with fish oil supplementation for 6 months [Citation6]. Participants’ baseline scores were similar. However, the improvement in the adherence to the MD was significantly higher in the intervention group after 2 years of follow-up. These results are similar to shown in a previous face-to-face intervention study developed in the Mediterranean area with depressed patients [Citation24]. In concordance to the SMILES trial, we found significant differences between groups in fruits and olive oil consumption [Citation5]. As in the HELFIMED study, statistically significant differences according to the intervention were found for fruits and nuts consumption in our trial [Citation6].

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths and limitations of this study that should be considered when interpreting the results.

The main strength of this study is that, as far as we know, this is the first trial that has evaluated the effect of a remote dietary intervention for a large period of time, up to 2 years. That long duration has allowed us to accurately evaluate the intervention adherence and its medium-long term effects.

However, the results of the nutritional intervention might not be applicable to the general population for two main reasons. On the one hand, the target of this study was to recover depression patients, and some clinical features that are common in these patients, such as latent cognitive, volitional, or hedonic changes, could be interfered in a proper comprehension and compliance of nutritional recommendations given by dieticians. On the other hand, the free provision of EVOO, which could be a strength of our study, could also represent a barrier to recommendation generalization because of the high cost of this product.

Moreover, although the clinical providers were blinded to the allocation group, the dietitians were not. The dietitians might have introduced a differential information bias, although through the use of validated questionnaires such as FFQs to assess information minimizes this possibility. In this sense, the use of FFQs instead of objective instruments, such as biomarkers, could have led to the presence of a recall bias, a social desirability bias, and other potential biases affecting the results. However, the FFQ has been previously validated [Citation10].

Although self-reported use of nutritional intervention tools may not fully reflect the completion of health education, periodical phone calls from the dietitian were used as a monitor system to assess and meet the educational needs of each participant.

Finally, we acknowledge that our results do not provide evidence to indicate that a remote intervention is more effective than an in-person intervention because this study did not use a control group with face-to-face intervention.

Conclusions

We found that a multifaceted remote nutritional intervention is a useful tool kit to maintain the quality of the diet according to the goals of the MD. We also consider that remote health promotion interventions could offer a cost-effective community approach.

| Abbreviations | ||

| BMI | = | Body mass index. |

| CIs | = | Confidence Intervals. |

| DS | = | Standard deviation. |

| EVOO | = | extra virgin olive oil. |

| FFQ | = | Food Frequency Questionnaire. |

| HELFIMED | = | Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil. |

| MD | = | Mediterranea diet. |

| MEDAS | = | Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener. |

| MET | = | Metabolic equivalent. |

| MUFAs | = | Monounsaturated fatty acids. |

| PDP | = | Provegetarian Dietary Pattern. |

| PREDIDEP | = | Prevention of depression with Mediterranean Diet (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea de Depresión). |

| PUFAs | = | polyunsaturated fatty acids. |

| SFA | = | Saturated fatty acids. |

| SMILES | = | Randomized controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression. |

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the PREDIDEP study participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006 Nov;3(11):e442. PubMed PMID: 17132052; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1664601. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

- Lopresti AL, Hood SD, Drummond PD. A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):12–279. Epub 2013 Feb 14. PubMed PMID: 23415826. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.014

- Rahe C, Unrath M, Berger K. Dietary patterns and the risk of depression in adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:997–1013. Epub 2014 Jan 28. PubMed PMID: 24468939. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0652-9

- Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, Jacka F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Kivimäki M, et al. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;24(7):965–86. Epub 2018 Sep 26. Erratum in: Mol Psychiatry. 2018 Nov 21: Erratum in: Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Mar 4. PubMed PMID: 30254236; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6755986. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med. 2017 Jan 30;15(1):23. Erratum in: BMC Med. 2018 Dec 28;16(1):236. PubMed PMID: 28137247; PMCID: PubMed Central PMC5282719. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

- Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, Wilson A, Bogomolova S, Villani A, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: a randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci. 2019 Jul;22(7):474–87. Epub 2017 Dec 7. PubMed PMID: 29215971. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320

- Young CL, Trapani K, Dawson S, O’Neil A, Kay-Lambkin F, Berk M, et al. Efficacy of online lifestyle interventions targeting lifestyle behaviour change in depressed populations: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;52(9):834–46. Epub 2018 Jul 27. PubMed PMID: 30052063. doi:10.1177/0004867418788659

- Young CL, Mohebbi M, Staudacher H, Berk M, Jacka FN, O’Neil A. Assessing the feasibility of an m-health intervention for changing diet quality and mood in individuals with depression: the My Food & Mood program. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2021 May;33(3):266–79. Epub 2021 May 27. PubMed PMID: 34039236. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1854193

- Sánchez-Villegas A, Cabrera-Suárez B, Molero P, González-Pinto A, Chiclana-Actis C, Cabrera C, et al. Preventing the recurrence of depression with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil. The PREDI-DEP trial: study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 11;19(1):63. PubMed PMID: 30744589; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6371613. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2036-4

- Martin-Moreno JM, Boyle P, Gorgojo L, Maisonneuve P, Fernandez-Rodriguez JC, Salvini S, et al. Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 1993 Jun;22(3):512–9. Pubmed PMID: 8359969. doi:10.1093/ije/22.3.512

- Martínez-González MA, López-Fontana C, Varo JJ, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martinez JA. Validation of the Spanish version of the physical activity questionnaire used in the nurses’ health study and the health professionals’ follow-up study. Public Health Nutr. 2005 Oct;8(7):920–7. Pubmed PMID: 16277809. doi:10.1079/phn2005745.

- Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 2011 Jun;141(6):1140–5. Epub 2011 Apr 20. PubMed PMID: 21508208. doi:10.3945/jn.110.135566

- Sánchez-Tainta A, San Julián B, Martínez-González MA. PREDIMED date el gusto de comer sano. Pamplona (Navarra): EUNSA; 2015.

- Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C. Tablas de composición de alimentos: Guía de prácticas (Spanish food composition tables). 7th edition. Madrid (Madrid): PIRAMIDE; 2003.

- Martínez-González MA, Sánchez-Tainta A, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Arós F, et al. A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Jul;100(Suppl 1):320S–8S. Epub 2014 May 28. Erratum in: Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Dec;100(6):1605. Pubmed PMID: 24871477. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071431

- Willett WC, Stampfer M. Implications of total energy intake for epidemiologic analyses. In: Willett WC, editor. Nutritional epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 273–301.

- Eysenbach G. What is e-health? J Med Internet Res. 2001 Apr-Jun;3(2):E20. Pubmed PMID: 11720962; Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC1761894. doi:10.2196/jmir.3.2.e20

- Jumreornvong O, Yang E, Race J, Appel J. Telemedicine and medical education in the age of COVID-19. Acad Med. 2020 Dec;95(12):1838–43. Pubmed PMID: 32889946; Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7489227. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003711

- Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010 Feb 17;12(1):e4. Pubmed PMID: 20164043; Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC2836773. doi:10.2196/jmir.1376

- Sánchez-Villegas A, Henríquez-Sánchez P, Ruiz-Canela M, Lahortiga F, Molero P, Toledo E, Martínez-González MA. A longitudinal analysis of diet quality scores and the risk of incident depression in the SUN project. BMC Med. 2015 Sep 17;13:197. PMID: 26377327; PMCID: PMC4573281. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0428-y

- Adjibade M, Assmann KE, Andreeva VA, Lemogne C, Hercberg S, Galan P, Kesse-Guyot E. Prospective association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of depressive symptoms in the French SU.VI.MAX cohort. Eur J Nutr. 2018 Apr;57(3):1225–35. Epub 2017 Mar 10. PMID: 28283824. doi:10.1007/s00394-017-1405-3

- Rienks J, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD. Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-aged women: results from a large community-based prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(1):75–82. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2012.193.

- Francis HM, Stevenson RJ, Chambers JR, Gupta D, Newey B, Lim CK. A brief diet intervention can reduce symptoms of depression in young adults – a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222768.

- Opie RS, O’Neil A, Jacka FN, Pizzinga J, Itsiopoulos C. A modified Mediterranean dietary intervention for adults with major depression: dietary protocol and feasibility data from the SMILES trial. Nutr Neurosci. 2018 Sep;21(7):487–501. Epub 2017 Apr 19. Pubmed PMID: 28424045. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2017.1312841