I thank David Elms for his thoughtful and extensive comments on my paper ‘Practical wisdom in an age of computerization’. His comments deserve a full reply.

He is right to highlight that that major challenges face everyone on the planet. The rise in global population and massive inequalities are equally important to us all. My choice to focus on three particular challenges does not imply that I consider the others to be of lesser importance. The points made in the paper are relevant, in my view, to all.

He perceives a lack of clarity in the paper. My purpose was clearly set out, as he acknowledges, to identify threats and opportunities, to re-evaluate the service we provide as civil engineers, to suggest ways of improving that service and to understand better what it is that we provide that cannot be turned into algorithms of AI.

Perhaps his perceived lack of clarity in the paper derives from his thinking that the threats and opportunities fit well with what we do and why we do it – but that increased efficiency and quality (including safety) and the effects of computerisation are somehow subsidiary. The reason I put them together is because quality and safety are paramount in our work and we are often rightly criticized for failures on time and budget as well as loss of life. That is why the section on the interacting objects process model (IOPM) is included. That model is about enabling joined-up systems thinking. It is about getting the right information (what) to the right people (who) at the right time (when) for the right purpose (why) in the right form (where) and in the right way (how). The effectiveness of the IOPM could be transformative if it is developed into servicing worldwide project intra-networks. I think Elms is also a bit dismissive of the loss and changing nature of engineering jobs. The lack of understanding by non-technically qualified decisions makers (politician and business-people) and opinion formers of what engineers ‘bring to the party’ is already leading, in some cases, to inappropriate and harmful decisions about the roles of engineers. These dangers could become even more serious in future projects where AI is used extensively. The distinction between routine work that can be covered by algorithms and that which requires practical intelligence and wisdom is crucial.

I agree entirely that we cannot base our decisions about the future on the past alone. Of course, we must learn lessons from the past and our theories do depend on testing in the past and present. We agree that a major concern is how we deal with unknown unknown surprises and that designing for resilience is key.

Our approach to resilience should be proactive and not reactive. This is why, in other work, my research team at Bristol developed a ‘Theory of Vulnerability’ (Wu et al. Citation1993; Lu et al. Citation2016). This is a proactive theory which identifies, in any engineering network, scenarios where small damage to a link can lead to disproportionate consequences.

Elms wants more specific examples of the similarities and differences between practical wisdom, intelligence, rigour and experience. First of all, I want to stress that our focus is on the practical as distinct from theoretical i.e. that which results from prudent acting or doing – the essence of engineering – rather than a theoretical ideal with its many contextual and generalized assumptions (e.g. elasticity). Wisdom is about discerning, judging properly and exercising discretion as to what is right. An analogy might be helpful. Writers often distinguish management from leadership by stating that good (practical intelligent) managers ‘do things right’ whereas good (practically wise) leaders ‘do the right things’. In the section ‘Practical wisdom is ethical’ I give 7 attributes. There could well be more and I have commented positively on Elms’ idea of a systems ‘stance’, in this volume.

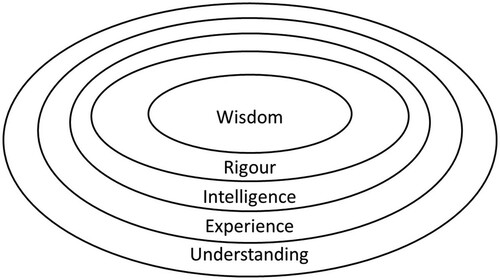

Put at its simplest one can imagine a Venn diagram with several sets contained inside each other like ‘Russian Dolls’ (). If set A is entirely contained in set B then A implies B. In other words (a) B is necessary but not sufficient for A and (b) A is sufficient for B.

The outermost set is practical understanding. Understanding is necessary but not sufficient for all engineering. It also deepens as we move to the inner sets of (in order) experience, intelligence, rigour and wisdom. So practical wisdom is sufficient for all of the others. It is perhaps worth noting that, by this view, experience does not necessarily bestow wisdom unless that experience is reflected upon and learned from. Likewise, experience does not necessarily bestow intelligence and rigour. Also, as I point out in the paper logical rigour is necessary but not sufficient for practical rigour.

In the example, of the seismic strengthening of a building, the problem is so constrained, as posed by Elms, so as to exclude many of the practical and ethical issues of a real project that particularly require practical wisdom. These include, sustainability, fitness for a right purpose, joined-up thinking that ensures design understanding is present onsite during construction, as well as the safety of people. Clearly, as posed, the problem requires the engineer to have an understanding of the flow of forces. However, the ‘blind’ following of a code of practice would demonstrate a lack of practical intelligence, rigour, foresight and wisdom. Elms describes a practically intelligent engineer who thinks through the behaviour of the actual structure rather than simply justfying a structural solution against the rules of a code of practice. That engineer may or may not be rigorous – which implies the thinking through of all options that could lead to a successful outcome. That rigour requires the engineer to have the practical foresight to imagine and anticipate all possible outcomes and scenarios. It requires a search for and production of solutions of varying ingenuity. Elms refers to the intelligent use of a beam to spread the load. There are others such as flexible roof bracing with springs and dampers. However, as noted, the example does not include any ethical choices and so there is small need, in the problem as posed, for practical wisdom over and above practical intelligence.

Elms worries that something is missing in our analysis but is unsure what it is. He comments that the three attributes of technical soundness, professionalism and personal qualities are necessary but not sufficient. The concept of practical wisdom was not part of the 1983 analysis by myself and Robertson (see references of original paper) but might now be added to that analysis. Practical wisdom touches on aspects of the qualities of a well-educated professional and of good personal qualities.

Finally perhaps Sellman (reference original paper) summarizes the issues well when he writes:

The competent practitioner is not concerned with merely getting through the work, not even with mere skills acquisition; rather, he/she aspires toward the Aristotelian ideal of doing the right thing to the right person at the right time in the right way for the right reason.

Supplement_Material.docx

Download MS Word (18.3 KB)References

- Lu, M., J. Agarwal, and D. Blockley. 2016. “Vulnerability of Road Networks.” Civil Engineering Systems. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10286608.2016.1148142

- Wu, X., D. Blockley, and N. J. Woodman. 1993. “Vulnerability of Structural Systems. Part 1: Rings and Clusters.” Civil Engineering and Environmental Systems 10 (4): 301–317. Part 2 Failure Scenarios. Civil Engineering and Environmental Systems. 10 (4): 319–333.