ABSTRACT

In a world which is ‘hanging by a thread', or conversely ‘teetering on the brink', where ‘humanity stands at the precipice', systems thinking can offer clarity when confronted with the unwitting distraction of cliché riddled aphorisms. By the examination of the earth system, its externalities in relation to economic development and perspectives of our relationship to the global commons within the economy, within government and within the established literature, a series of propositions are developed. Some are used subsequently to offer explanation of current approaches to climate change; others highlight the obvious importance of systems thinking to the engineering professions. Finally, in a brief discussion, these propositions are used syllogistically to suggest that rationalism and universal self-interest will avoid irreversible climate change and its associated environmental apocalypse. Conflicting interests and self-interest, inter alia, within the global system of production and development suggest that the achievement of basic human rights and the UN Sustainable Development Goals, however rational and well supported, will prove rather more intractable.

1. Introduction

Systems are human constructs of structures and associated phenomena that offer clarity to our thinking and provide explanations of the interconnectedness of their parts and of their observed behaviour or condition. They are particularly helpful in understanding problems, in offering explanations and (sometimes normative) solutions or in unearthing issues that may have so far eluded consideration. A reductionist seeks explanation in only a few simple components, a dualist may see a whole as two completely separate parts (e.g. mankind and the natural world), whereas a systemicist should be able to consider the whole by understanding the interconnectedness of its parts.

The call for this Special Issue observed ‘Scientists and professional engineers recognise the impending climate crisis, the widespread frustration in tackling global poverty, environmental damage and resource depletion and the mass extinction of plant and animal species. The true costs of centuries of exploitation of what were once considered ‘free goods’ are now all too evident. The roles of the market, regulation and international agreements to bring about the changes necessary to avert future catastrophes are not clear. But many acknowledge the need for linked-up thinking and systems wide solutions’.

A well-constructed system will encourage us to examine it from different viewpoints, challenge conventional or orthodox approaches, and probe more deeply into the ideas and reflections of others who may have attempted similar investigations.

2. Systems and their importance

The training of any engineer must enable the resulting professionals to design new things, and with these designs, the calculations necessary for their construction and safe operation. It is important that widgets work correctly and bridges don’t fall down. And above all, this must be achieved efficiently, with efficiency invariably determined by some form of economic benefit-cost calculation. A reductionist training which limits a professional to these needs no consideration of any system beyond that which is entirely internal to the structure or widget or on which their associated mechanics depend and of course the associated costs. And these alone we know make for a very full syllabus.

Let us reflect on a premise that it is possible (albeit far from desirable) for the training of engineers to ignore the wider systems within which the practice of their discipline occurs. It is to suggest that it is possible for their professional practice to have no sense of any relationship with the natural world, other than that necessary for its construction in the environment in which it takes place.

It is not a premise that we restrict the training of engineers. Eugene Rabinowitch, editor of the scientific journal, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, wrote the following in a letter to The Times of 29 April 1972:

The only animals whose disappearance may threaten the biological viability of man on earth are the bacteria normally inhabiting our bodies. For the rest there is no convincing proof that mankind could not survive even as the only animal species on earth! If economical ways could be developed for synthesising food from inorganic raw materials—which is likely to happen sooner or later—man may even be able to become independent of plants on which he now depends as sources of his food … I personally—and I suspect a vast majority of mankind—would shudder at the idea [of a habitat without animals and plants]. But millions of inhabitants of ‘city jungles’ of New York, Chicago, London or Tokyo have grown up and spent their whole lives in a practically ‘azoic’ habitat (leaving out rats, mice, cockroaches and other such obnoxious species) and have survived.

Proposition 1:

a systems understanding is critical to avoiding the environmental apocalypse.

3. Externalities and development within the earth system

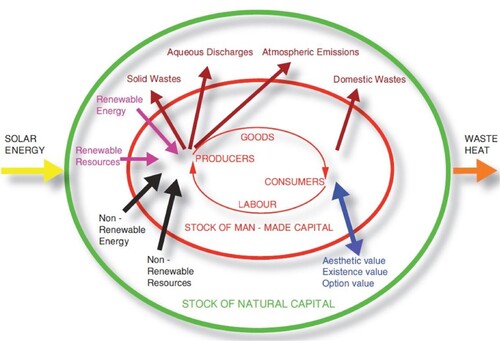

shows a simple earth system map with the economy performing as an engine, consuming fuel and emitting waste products, with the work done resulting in society’s stock of man-made capital. It has been reduced to its bare bones, but as a framework can be extended to incorporate other detail of our relationship with the natural world and within the economy. Some may recognise here a form of the famous Lauderdale Paradox: an increase in man-made wealth has only come about at the expense of a decrease in the wealth of the stock of natural capital or public wealth (The Earl of Lauderdale, Citation1804).

Figure 1. The earth system, showing the inputs and outputs from the economy within the earth’s stock of natural capital.

Presented this way it is easy to see the manner in which externalities (i.e. actions or processes external to the market) have made modern industrial development possible. The sources of fuel (e.g. the oil in the ground, the wind driving wind turbines) are free goods until captured and placed in the market. The ability to use the natural world for the discharge of wastes has also historically been a free good and for atmospheric emissions and many aqueous discharges mostly still is, although now sometimes regulated. Development has viewed our stock of natural capital as a free good, sometimes as a commons belonging to all, but for land mostly as something over which no one had a prior claim of property right until it was appropriated.

Demsetz argued, ‘property rights develop to internalise externalities when the gains of internalization become larger than the cost of internalization’ (Citation1967). In one sense Demsetz is correct. While many historical developments of property rights in land may have had little to do with internalising externalities, it is clear their maintenance by law ensures it.

One paper with now well over 40,000 citations, penned by the ecologist Garrett Hardin extended this thinking about externalities to examine the remaining commons. Here, the ‘commons’ is used in its broadest sense, from a small patch of common grazing land to the earth’s atmosphere or water cycle. In the Tragedy of the Commons, Hardin (Citation1968) uses a simple arithmetic device to demonstrate why herdsmen on a commons will always overgraze the pasture.

As a rational being each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain. Explicitly or implicitly, more or less consciously, he asks ‘what is the utility to me of adding one more animal to the herd?’ This utility has one negative and one positive component.

The positive component is a function of the increment of one animal. Since the herdsman receives all the proceeds from the sale of the additional animal the positive utility is nearly +1.

The negative component is a function of the additional overgrazing created by one more animal. Since, however, the effects of overgrazing are shared by all herdsmen, the negative utility for any herdsman taking this decision is only a fraction of −1.

Adding these together the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course of action for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd. And another. ..But this is the conclusion reached by every rational herdsman sharing a commons.

Of course, the characterisation of such externalities as a ‘commons’, a res communis, is not the only characterisation possible. The early civilisations of the Roman and Greek empires tended to view the seas as a commons belonging to all, with laws governing piracy and upholding freedom of navigation for trade. This changed dramatically in mediaeval times, most notably in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This established a line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands running from North to South Poles. Unless otherwise in the possession of Christian power, all lands to the west of this line were deemed Spanish, and to the east, Portuguese. No vessels were to voyage to these ‘new’ lands or to fish in their waters without agreement from these sovereign powers. Rather than res communis, these lands and waters were seen as res nullis, available for appropriation without infringement of anyone’s rights in the commons. The ideas of res nullis resurfaced during arguments over the characterisation of the deep seabed in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, which finally entered into force in 1994. Economists such as Denman (Citation1983), opposing its adoption, argued the deep sea belonged to no nation and was thus available to whomsoever wished to exploit it. Intriguingly, the treaty characterised the area of the seas beyond national jurisdiction as ‘the common heritage of mankind’, introducing, to the concept of the commons, the idea that it is a commons for our and future generations, a notion of intergenerational equity that was to be developed further a few years later in Gro Harlem Bruntdland’s definition of sustainable development.

We might characterise some broad typologies. The denier or obtuse who is unable to grasp or believe there is a threat to the commons (typified by responses of the Trump administration to the climate emergency). Those convinced by the partial rationality of Hardin’s argument, and/or for whom greed will always be the overwhelming response (even though they may recognise at least the dilemma between greed and cooperation), and those for whom cooperation is clearly the most rational of all responses.

Proposition 2:

True rationality leads to cooperation in managing externalities in a global commons, and of anthropogenic risks to it.

4. The climate emergency

Despite the confidence in so much of the science, there are still climate emergency deniers. The imperative of international cooperation, however, now seems so well established and practised that Proposition 2 seems completely supportable in tackling CO2 reduction. While everyone may vote for development that ‘does not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ quite what that means in this context is a little harder to determine.

Those comprising the next immediate generation are taking to the streets across the world, organising school protests and have concluded their own international conference in Milan, Youth4Climate: Driving Ambition (Citation2021), with young delegates from around the globe setting out their demands in advance of Glasgow’s COP26. It does seem that these next-generation stakeholders and their demands are the most relevant when we consider intergenerational equity. On their Friday march through the streets of Glasgow and in meetings during COP26, their message was clear: they will be the first to live through our generation’s failures or successes, and their voices should be heard. There is a distributional dilemma as well when considering which countries should take on the greatest burden of reduction and countermeasures. This appears also to have been partially resolved – those nations who have contributed least to atmospheric emissions historically are generally those who are most vulnerable to their effects now and in the future. Any notion of fairness of international (between countries) or of intergenerational (between generations) justice suggests the burden cannot be equally shared, but distributed largely to this generation and to high-income countries. But how much action and how quickly and exactly by whom it should be taken (or on whom the distribution of burdens will be apportioned) remain still matters for ongoing international cooperation and dialogue to establish, and there is a long way to go.

At the time of writing, we are simply not on track for holding the world to an ‘increase in … temperature to well below 2°C’, let alone the preferred 1.5°C favoured in the Paris Agreement. The pledges made by parties at the time of the Paris Agreement (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions), even when fulfilled, suggest an increase in global surface temperature of 2.7°C (UNEP Citation2021 and see Rogelj et al. Citation2016 for median and other ranges). Rather more alarmingly, the now widely adopted goal of ‘net zero’ by the middle of this century incorporating capture technologies and planting of trees or biofuels as offsets for allowing continued CO2 emissions appears to many to have been little more than fanciful (Anderson Citation2015).

The amount of land required as offsets is staggering and amounts to some 25–80% of the land which is presently farmed (Fajardy et al. Citation2019). Mostly, this will mean the introduction of fast-growing non-native species consuming greater amounts of water, all at the expense of biodiversity and traditional agriculture. Carbon, capture and storage have yet to be demonstrated in any cost-effective way, let alone at any scale, with most of the originally planned demonstration projects now axed or put on hold. Ironically, the surviving and recently announced projects are largely limited to enhanced oil recovery schemes injecting CO2 to increase oil production from aging reservoirs or generating hydrogen from hydrocarbon production. There are many ways in which small reductions in greenhouse gas emissions can be achieved, but it is all too easy to pledge ‘net zero’ by 2050 without demonstrating any real substance or magnitude to the measures envisaged.

It is obviously good to plant native trees and woodland, but far better to halt the existing rates of deforestation. So at COP26, world leaders, representing over 80% of the global area of natural forests, made a commitment to reverse forest loss by 2030, with 11 states and the EU committing $12 billion to this endeavour. We have been here before. In 2005, the UN Forum on Forests committed to reverse the loss in forest cover worldwide by 2015. Other efforts were made in 2008 (Brown and Zarin Citation2013). Failures resulted in the overarching goal of the New York Declaration on Forests (NYDF), agreed upon in September 2014, which was to halve the loss of natural forests by 2020 and halt it by 2030. Despite this not only are we not close to halving forest loss, but humid tropical primary forest loss is well above pre-NYDF levels, with an average of 41% more loss each year after the NYDF was signed than before (Progress on NYDF, 2020). The Progress Report notes that the ‘sustained reductions in forest loss needed to achieve the 2030 target would be unprecedented and are highly unlikely’.

This highlights a significant failure of the COP process (see Timperley Citation2021). For many low- and middle-income countries, pledges on climate finance have become a double-cross to bear. First, the pledges made (e.g. $100 billion per annum by 2020, from COP15 in 2009), although miniscule compared to what is needed (estimated at $5.8–$5.9 trillion by 2030 by the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance Citation2021), have not materialised. Second, around 80% of those pledges actually fulfilled are in the form of loans and non-grant instruments, which is simply increasing the debt burden and debt distress of the developing world (Oxfam Citation2020).

Holding the rise in global temperature to 1.5°C rather than 2°C will result in ‘substantial economic benefits’ with ‘particularly large benefits for the poorest populations’ (Burke, Davis, and Diffenbaugh Citation2018) and would undeniably prevent huge losses in biodiversity as well as a myriad of other benefits, over the 2 degree scenario (IPCC, Citation2018). Put simply, as many suggest, we need to halt carbon emissions, provide far more climate finance support in the form of grants, focus on the emerging green technologies, think again about what is meant by sustained economic growth, and not rely on technological fixes to continue our old fossil fuel burning habits.

But, as Europe and North America have witnessed in recent years: no country, group or class is free from the impacts of climate change. New green industries are burgeoning here, and existing ones are transforming around renewable energy and green hydrogen production from renewable sources, with numerous trials for hydrogen substitution and energy storage. The cost of these technologies has also fallen dramatically with wind and photovoltaics more than able to compete with fossil fuel generation. Some $330 billion or around 0.3% of world GDP was private climate funding in 2017, mostly for renewable energy projects and from corporations and commercial finance institutions (CPI Citation2019). This may be a cause for optimism and indeed was for many delegates at COP26, but once again – as with climate finance in the form of loans – it results less in technology transfer but more in the net transfer of funds from the developing to the developed world, but as profits to private capital. Although Proposition 2 undoubtedly applies, one has to acknowledge that so many vested interests are still pursuing Hardin’s ‘rational herdsman’s’ conclusion, or simply kicking the can down the road.

5. Environmental valuation and ethics

also shows us as consumers or assigners of non-market values in the natural environment and its stock of capital. The Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) has come to prominence in recent years as the principal means of internalising non-market environmental goods, in money terms (Pearce and Turner Citation1990). These include, at least, (1) the aesthetic value from experiencing the natural world; (2) the existence value from knowing elements of the natural world continue to exist even though they may not be experienced firsthand; and (3) the bequest or option value where the benefit is maintained for future generations. CVM is a means of internalising environmental externalities into the market decision-making process by establishing an experimental surrogate value by polling respondents. As individuals are infinitely willing to accept (WTA) compensation for losses, now almost universally willingness to pay (WTP) to prevent something from being lost or changed (or less often a benefit created) is the technique used in CVM surveys. One is asked merely to state how much of one’s disposable income/wealth one would part with in order to achieve or prevent X. But in each survey X is an almost infinitesimal part of the natural world, and summing these parts suggests that the natural world can only be worth less than the disposable surplus value created by the economy, an inefficient economy which grows by continuing to consume, damage and destroy it. CVM appears a somewhat strange reversal of the Lauderdale Paradox (The Earl of Lauderdale, Citation1804).

After all, some of us might have inherited something for which our disposable wealth could never pay and which we wish to pass to our children or which we may simply consider to be without price.

A number of studies have addressed this apparent difficulty, often with surprising results. In one study seeking to set up a trust fund to preserve an area of ancient Scottish woodland for rare birds and mammals (see Spash Citation2000), 194 of those responding replied that animals/ecosystems/plants have rights and should be protected regardless of the costs to society. Although 46 of these refused to offer a WTP value and thus were taken to have demonstrated a strong ethical stance in this study, the remaining 148 went along with the CVM questionnaire and supplied a value, perhaps assuming that the only proposal on offer was worth some support in this way, despite previously having expressed a clear ethical position.

Others have argued that an environmental ethic is a contradiction in terms. The environment is not sentient, nor able to reciprocate, and surely an ethic requires both in those to which it applies. Nature, they might say, has no intrinsic value, only instrumental value to those who exploit it (or as we see with the above contingent valuation method, perhaps wish to conserve/preserve it). The bible gave Christendom ‘dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth’ (Genesis 1:26). Descartes, the greatest of dualists, asserted that only men have souls and the rest of the living world is just like a machine, lacking in feeling and unable to feel pain – a recipe that cleared Vesalius’ conscience when nailing living dogs to his dissection table to examine them in much the same way as one would the workings of a ticking clock. It was the Scot John Muir who was the first to challenge seriously the Christian orthodoxy: ‘Why should man value himself as more than a small part of the one great unit of creation?’ (1916). Muir founded the Sierra Club and campaigned to establish the Yosemite National Park, the first national park designated for the purposes of nature preservation.

The idea of nature being there for mankind runs through so much western philosophy, leading finally to articulation in what is often referred to as the resource conservation ethic. This is really an extension of Jeremy Bentham’s ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ to which the US forester Gifford Pinchot added ‘for the longest time’. It is truly anthropocentric and dualist seeing nature as a bundle of resources; however, it does imply these should be used efficiently and also with a view to the future. Thomas Tredgold provided a definition of civil engineering, which appeared in the original 1821 ICE charter: ‘the art of directing the great sources of power in nature for the use and convenience of man’. Chairing the ICE Task Force for embedding sustainability into engineering education, Professor Jowitt, suggested altering three words to: The art of working with the great sources of power in nature for the use and benefit of society. (Jowitt Citation2018)

But it was another American forester, Aldo Leopold, who first gave substance to the idea of an environmental ethic. For Leopold, the constituency over which our ethics exerted influence was continually expanding. Changing our ideas and actions so that human beings could no longer be viewed as the property of another, developing clarity in social relations between races and peoples, and ultimately he argued this social evolution in ethics would guide our actions in relation to the environment. Just as we have a social conscience so we would adopt an ecological one, providing guidance on right or wrong actions. Leopold (Citation1947) argued:

A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

There are other voices (see ). The American philosopher James (Citation1890) first distinguished between the ego and the empirical self:

It is clear that between what a man calls me and what he simply calls mine the line is difficult to draw. We feel and act about certain things that are ours very much as we feel and act about ourselves. Our fame, our children, the work of our hands, may be as dear to us as our bodies are, and arouse the same feelings and the same acts of reprisal if attacked. Our father and mother, our wife and babes, are bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh. When they die, a part of our very selves is gone. If they do anything wrong, it is our shame. If they are insulted, our anger flashes forth as readily as if we stood in their place. Our home comes next. Its scenes are part of our life; its aspects awaken the tenderest feelings of affection.

Table 1. Ideas and Reflections on the Value of Nature and its Biodiversity.

For ecologists, it may seem paradoxical that while we attribute intrinsic value to humankind, for the rest of the global biodiversity and the very processes of nature, of natural selection and evolutionary change, from which ours, other species and the global biosphere have emerged, there remains the view that these can only be of instrumental value to us. (In the present-day parlance, nature is valued only for the ‘environmental services’ it provides).

Might we take the final step and declare that nature has intrinsic value? It matters little here whether that is derived from value objectivism or value subjectivism. If nature has intrinsic value then halting the environmental apocalypse would not (as Emmanuel Kant would have it) be an act of good sense or even beauty, but rather it would be a truly moral act.

Proposition 3:

An environmental ethic can bring about changes in behaviour without requiring changes in the law or market regulation and is not dependent on financial measurement, incentive or benefit.

6. The SDGs, poverty, inequality and distributive justice

‘So distribution should undo excess

And each man have enough’. (Shakespeare, King Lear, Act 4, Scene 1)

SDG8 is concerned with promoting growth, sustained per capita economic growth for all countries, raising annual increases in GDP by 7% in the least developed countries, (thus?) achieving full and productive employment for women, men, the young and disabled but at the same time decoupling growth from environmental degradation. These targets are unlikely to be achieved and were problematic even before the pandemic. Naidoo and Fisher (Citation2020) note that even before the coronavirus pandemic, the shortfall in financing necessary to achieve the SDGs was $2.5trillion. Underpinning the SDG project is blind faith in the panacea of economic growth. Just grow the economy and watch wealth trickle down. Many have and continue to challenge this mantra (see Daly Citation2005). Why not focus on development (improving well-being) rather than on growth? (Naidoo and Fisher Citation2020).

Table 2. Extracts from the Report of the United Nations Secretary General.

The achieving of so many of the SDGs depends on poverty reduction (SDG1). Obviously, freedom from hunger or poor nutrition (SDG2) is clearly linked to this, as is good health and well-being (SDG3) and access to quality education (SDG4). Education in turn helps reduce poverty; can contribute to the reduction in child marriages, to the uptake of contraception, and to greater gender equality (SDG5); and will contribute to the reduction in inequalities within and between countries (SDG10). With this in mind, we can examine more closely what comprises the stock of man-made capital shown in and probe a little more deeply into its distribution.

Plato argued in his Laws that the income of the highest paid in society should never amount to more than four or five times that of the lowest (Citation1980 translation). According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, in August 2020, Jeff Bezos became the first person in history to be worth more than $200 billion. In the same year, despite the COVID 19 pandemic the richest 500 people in the world accumulated a total worth of $7.6 trillion, by adding $1.8 trillion in those twelve months, and for the first time, 1% of the global adult population became dollar millionaires. To put this in perspective the global GDP in 2020 was $84.5 trillion; thus between them, 500 people amassed over 2% of the global GDP. In sharp contrast, 750 million continue to live in extreme poverty (using the World Bank’s $1.90 a day threshold), and COVID 19 is projected to push a further 70–119 million people into extreme poverty (World Bank Citation2020 and United Nations Secretary General Citation2021). Wealth from growth, it appears, is being sucked up rather than trickling down.

There has, of course, been a large literature since Plato on poverty, inequality and ethics. Within this the concept of distributive justice, which underpins our approach to the SDGs, has given rise to many often conflicting strands (or - isms), for example:

That every person should have enough to be able to meet their needs (sufficient-ism). This was perhaps first fully expressed in the writings of Tom Paine, but presented in his Rights of Man as fundamental human rights.

That every person should have an equal distribution, or the distribution should be equitable in some way (egalitarian-ism), or at least this should inform the priorities for further distribution (prioritisation-ism). Addressing these is a multitude of differing interpretations, views and perspectives.

There should be upper limits to the income and wealth that people can hold (limitarian-ism), an idea first championed by Plato and Aristotle, but developed more recently in work such as Robeyns (Citation2019), and as applied to corporations by Meyer (Citation2021).

None of the above is correct as they distract from what matters, i.e. the basic human rights that people should enjoy (libertarian-ism). Not surprisingly, this is mostly invoked as an argument against 2 and 3.

It is important to see the real world against a backdrop of these more philosophical reflections. Our international treaties on human rights continue to be interpreted as merely aspirational, and human rights remain marginal and often invisible in the overall SDG context (Alston Citation2020). Instead of the SDGs, the concept of ‘extreme poverty’ is employed by the World Bank as the threshold at a level of $1.90 per day subsistence, making improbable the meeting of even the most basic of human rights for those so restricted. Yet some 750 million live below this threshold, and over half the world’s population (4.1 billion people) live without any form of social protection for basic subsistence, health, disability or provision for old age, etc. As Credit Suisse notes: ‘the bottom 50% of adults in the global wealth distribution together accounted for less than 1% of total global wealth at the end of 2020’ (Shorrocks, Davies, and Lluberas Citation2021).

In contrast, global corporate taxation rates have fallen from 40.11% in 1980 to 23.85% in 2020 (Asen Citation2020), and some 40% of multinational corporation profits were shifted to tax havens in 2015 (Tørsløv, Wier, and Zucman Citation2020), depriving governments of around $600 billion annually, the greatest losers being low- and middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia (Cobham and Janski Citation2018). Low- and middle-income countries pay $860 billion annually in principal repayments and $220 billion in interest repayments on an aid debt of $8.1 trillion (The World Bank Citation2021). This is additional to the climate loans already discussed. As Alston (Citation2020) notes following centuries of colonial exploitation, developing countries continue to be net providers of resources to the rest of the world. Borrowing terms are so much more favourable for high-income countries.

Yet there are so many potential solutions that we can all recognise:

Reverse the trends in taxation policy and tax capital more than labour.

Engage in wide-scale international debt relief linked to social protection programmes.

Ditch the neoliberal idea of ever-increasing GDPs and the mantra of trickle-down economics, but target growth to achieving social and environmental protection.

Instead of development that keeps wages low, consumes resources and emits wastes, focus on development in a circular economy that pays a living wage.

While many would require international and political cooperation perhaps even on a similar scale to that being undertaken to avert the climate apocalypse, there is nothing here that is technically impossible, given the political will and cooperation.

We should reflect again, avoiding a reductionist approach. Unlike much of the stock of natural capital in , the economy and man-made capital by definition are not a commons: unlike the climate emergency that affects the entire world and thus is clearly a problem for us, we see global poverty as a problem for others, and their governments and economies to solve. Within developed countries, poverty is often localised, and between-country poverty seems even more distant to those of us fortunate to live in high-income countries. The developed world is willing to chip in to help but ultimately it is someone else’s problem and we are all too easily persuaded of the benefits of our economic status quo. (Instead we may even suggest: perhaps the best response is to revise the SDGs so that they become more achievable.) As with COVID-19, which given global travel and exchange, does potentially affect a global commons, the response of the developed world has nonetheless been one determined by singular self-interest.

Proposition 4:

No group, class or nation is free from the impacts of the climate emergency and consequential environmental degradation. The same cannot be said for the impacts that other sustainable development goals seek to remedy.

7. Discussion

Few would argue with the first proposition; it is difficult to negate, but does imply that the training of engineers, and professionals whose work involves alteration of the natural world in some way should be encouraged to avoid reductionist and dualist thinking, but rather should be given the tools to think holistically in terms of systems.

The second proposition seems supportable at least in so far as international cooperation in seeking the adoption of measures to tackle the climate emergency has taken us this far. It provides at least the basis for optimism. Nonetheless, avoidance of business as usual based on the belief in some spurious technological fix, such as flooding the atmosphere with sea water clouds, or even sulphuric acid, is essential. There is no alternative to that of reducing and continuing to halt carbon emissions as quickly as possible in the next decade. This way we should avoid the apocalypse but it is very doubtful that we will hit the 1.5-degree target.

Of the third proposition, there is evidence that increasingly we are adopting a sense of morality in our relationship with the natural world, and this also increases pressure to achieve climate goals particularly from the young. There are of course many dualists who maintain that nature is ours and while we might sometimes despoil it or conversely protect it, it is only the benefits it conveys to us that are important – the so-called environmental services. But these are under threat from the climate emergency and equally demand action. Others argue that those deeply concerned about nature show little interest in improving the human condition, or those who are poor cannot afford moral actions in regard to the nonhuman world. The first argument is blatant nonsense and easily countered by examining any manifestos of the environmentalist movement and its parties. As for the second, we should remember that the UN World Charter on Nature () was championed by a group of economically poorer nations. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly with only one dissenting vote, that of the United States.

That the SDGs and their predecessors, the Millennium Goals, exist at all suggests some internationally accepted moral view that the quality of life of most of the world’s population needs to be improved. We acknowledge, as did Kant, that all human life has intrinsic value. But for decades we have had in international law the right to an adequate standard of living for every person and their family, ‘including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions’. Freedom from hunger is a ‘fundamental human right’ in international law, and everyone should likewise enjoy the right to social security and insurance. Here, there is little optimism. Even were all of the SDG targets to be met, the world would still be a long way from fulfilling these basic human rights established in international law; of course, few of the targets will be met. Unlike the global climate which is undeniably a commons, the economy and the capital it generates are based on private property rights, with governments and international institutions maintaining faith in neoliberal capitalism, growth in GDP and the false premise that the wealth thus generated will trickle down. The self-interest implied in Proposition 4 suggests that the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, however short they may fall in terms of the sufficient-ism of basic human needs, will still prove rather intractable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alston, P. 2020. The parlous state of poverty eradication. Report of the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. 43rd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council. 19 November 2020, A/HRC/44/40. The parlous state of poverty eradication: (un.org) accessed November 2021.

- Anderson, K. 2015. “Talks in the City of Light Generate More Heat.” Nature 528, 437. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/528437a.

- Asen, E. 2020. Corporate Tax Rates Around the World. The Tax Foundation. Washington: Corporate Tax Rates Around the World.

- Brown, S., and D. Zarin. 2013. “What Does Zero Deforestation Mean?” Science 342 (6160): 805–807. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241277.

- Burke, M., W. M. Davis, and N. S. Diffenbaugh. 2018. “Large Potential Reduction in Economic Damages Under UN Mitigation Targets.” Nature 557 (7706): 549–553. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0071-9.

- Carson, R. 1963. Silent Spring. London: Hamish Hamilton: 304.

- Cobham, A., and P. Janski. 2018. “Global Distribution of Revenue Loss from Corporate tax Avoidance; re-Estimation and Country Results.” Journal of International Development 30: 206–232. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3348.

- C.P.I. 2019. Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019 [Barbara Buchner, Alex Clark, Angela Falconer, Rob Macquarie, Chavi Meattle, Rowena Tolentino, Cooper Wetherbee]. Climate Policy Initiative, London. Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019 - CPI (climatepolicyinitiative.org).

- Daly, H. 2005. “Economics in a Full World.” Scientific American 293 (3): 100–107. Economics in a Full World - Scientific American.

- Demsetz, H. 1967. “Towards a Theory of Property Rights.” American Economic Review 57 (2): 347–359. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-8282%28196705%2957%3A2%3C347%3ATATOPR%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X.

- Denman, D. R. 1983. Markets Under the sea. A Hobarth Society Paperback. London: Hobarth Society, Institute of Economic Affairs. 80pp.

- The Earl of Lauderdale. 1804. Inquiry Into the Nature and Origin of Public Wealth. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Co. (Second edition 1819). InquiryNatureOriginPublicWealth.pdf (mcmaster.ca) accessed November 2021.

- European Commission. 2011. Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. COM(2011) 244 final. EUR-Lex - 52011DC0244 - EN - EUR-Lex (europa.eu).

- Fajardy, M., A. Koberle, N. MacDowell, and A. Fantuzz. 2019. BECCS Deployment: A Reality Check. London: The Grantham Institute.

- Hardin, G. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162: 1243–1248. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1724745

- Hugo, V. 1895. Victor Hugo's Letters to His Wife and Others (The Alps and the Pyrenees), Classic Reprint. London: Forgotten Books. Reprinted 2018.

- IPCC. 2018. “Global Warming of 1.5 degrees.” An IPCC Special Report. Global Warming 1.

- James, W. 1890. The Principles of Psychology. New York: Henry Holt & Co. (Reprinted 1918).

- Jowitt, P. 2018. “Defining Civil Engineering.” New Civil Engineer March 2018: p23.

- Leakey, R., and R. Lewin. 1996. The Sixth Extinction: Biodiversity and its Survival. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 271pp.

- Leopold, A. 1947. “The Land Ethic.” In A Sand County Almanac, edited by A. Leopold, 201–226. Well Oxford University.

- Meyer, K. 2021. “Corporate Limitarianism.” Penn. Journal of Philosophy, Politics and Economics 16: 33–44.

- Muir, J. 1916. A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf. Boston and New York: Houghton and Mifflin.

- Naess, A. 1984. “Identification as a Source of Deep Ecological Attitudes.” In Deep Ecology, edited by M. Tobias, 256–270. California: Avant Books.

- Naess, A. 2008. The Ecology of Wisdom. Berkeley: Counterpoint. 339pp

- Naidoo, R., and B. Fisher. 2020. “Sustainable Development Goals: Pandemic Reset.” Nature 583: 198–201. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01999-x

- Oxfam. 2020. “Climate Finance Shadow Report 2020: Assessing Progress Toward the $100 Billion Commitment.” Oxfam UK for Oxfam International 1–32 DOI:https://doi.org/10.21201/2020.6621

- Pearce, D. W., and R. K. Turner. 1990. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf. 378pp

- Plato. 1980. edition. The Laws of Plato. Translated by Thomas L. Pangle, 1980. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Robeyns, I. 2019. “What, if Anything, is Wrong with Extreme Wealth?” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 20 (3): 251–266. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2019.1633734

- Rogelj, J., M. den Elzen, N. Höhne, T. Fransen, H. Fekete, H. Winkler, R. Schaeffer, F. Sha, K. Riahi, and M. Meinshausen. 2016. “Paris Agreement Climate Proposals Need a Boost to Keep Warming Well Below 2 °C.” Nature 534: 631–639. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18307.

- Shorrocks, A., J. Davies, and R. Lluberas. 2021. Credit Suisse. Global Wealth Report 2021. 57pp. Global wealth report – Credit Suisse (credit-suisse.com) accessed November 2021.

- Soulé, M. E. 1985. “What is Conservation Biology?” Bioscience 35: 727–734. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2307/1310054.

- Spash, C. L. 2000. “Ecosystems, Contingent Valuation and Ethics: The Case of Wetland re-Creation.” Ecological Economics 34: 195–215. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00158-0.

- Timperley, J. 2021. “The Broken $100-Billion Promise of Climate Finance — and how to fix it.” Nature 598: 400–402. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02846-3

- Tørsløv, T. R., L. S. Wier, and G. Zucman. 2020. “The Missing Profits of Nations.” NBER Working Paper No. 24701 1–40. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3386/w24701.

- UNEP. 2021. Emissions Gap 2021. The Heat is on: A World of Climate Promises not yet Delivered. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya. 79pp. Emissions Gap Report 2021 | UNEP - UN Environment Programme accessed November 2021.

- UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance,. 2021. First report on the determination of the needs of developing countries Parties to the Convention and the Paris Agreement. UNFCCC, Bonn. 182pp. 54307_2 - UNFCCC First NDR technical report - web (004).pdf accessed November 2021.

- UN Secretary General. 2021. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Report of the Secretary General to the United Nations Economic and Social Council. E/2021/58. 28467E_2021_58_EN.pdf (un.org) accessed November 2021.

- UN World Charter on Nature. . 1982. World Charter for Nature. (un.org).

- World Bank. 2020. Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty. World Bank Blogs, 8 June 2020. Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty (worldbank.org) accessed November 2021.

- World Bank. 2021. International Debt Statistics. International Debt Statistics 2021 (worldbank.org) accessed November 2021.

- Youth4Climate. 2021. Driving Ambition 2021. Youth4Climate-Manifesto.pdf (ukcop26.org) accessed November 2021.