ABSTRACT

Cultural policy typologies are a widely discussed topic in cultural policy research, though only a few typologies have been developed so far. The aim of this paper is to analyze existing cultural policy typologies for European countries and contextualize them for Central-Eastern European countries with a focus on cultural economies. Based on existing indicators on national and international levels to compare these assumed typologies, we use Bayesian hierarchical cluster analysis supported by spike and slab empirical priors. The article focuses specifically on four Central-Eastern European countries: Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Results reveal several inconsistencies in the existing typologies and a strong common cluster of Eastern European countries in terms of cultural policy and cultural economic characteristics. We sketch out a new cultural policy model typology based on empirical evidence on cultural economies.

1. Introduction

Typologies, defined as organized systems of types, are a well-established analytic tool in the social sciences (Collier, LaPorte, and Seawright Citation2012). They make crucial contributions to diverse analytic tasks: forming and refining concepts, drawing out underlying dimensions, creating categories for classification and measurement, and sorting cases. Some scholars consider typologies and the categorical variables from which they are constructed to be old-fashioned and unsophisticated. As Collier, LaPorte, and Seawright (Citation2012) state, their critique largely underestimates the challenges of conceptualization and measurement in quantitative work and fails to recognize that quantitative analysis is built in part on qualitative foundations. It also fails to consider the potential rigor and conceptual power of qualitative analysis and likewise does not acknowledge that typologies can provide new insight into underlying dimensions, thereby strengthening both quantitative and qualitative research.

Typologies construction, potentially conceptual and not based on formal modeling, can lead to problems of authority relationships. The relevant questions are as follows. Who constructs the typologies? And for whom are they made? If the typologies are based on conceptual work, problems of orientalism (Said Citation1978) can be present: Western authors can view the Eastern world through a Western lens, which can distort the validity of the approach and lead to a ‘Western bias.’ It is also possible that if the typologies are empirically constructed, the used indicators can be ‘Western-driven,’ i.e. view and chosen in the lens of the analyst. While it is difficult to avoid this issue, revealing the assumptions under which the typologies are constructed can reduce the bias in the results.

Definitions of cultural policy date to the 1960s. The first and most common understanding of ‘cultural policy’ was encapsulated many years ago by Girard and Gentil (Citation1983: 13, in Isar Citation2009) as ‘a system of ultimate aims, practical objectives and means, pursued by a group and applied by an authority, combined in an explicitly coherent system.’ Here cultural policy is defined as what governments (as well as other entities) envision and enact in terms of ‘cultural affairs,’ defined as relating to ‘the works and practices of intellectual, and especially artistic activity’ (Williams Citation1988, 90).

However, state policies are far from being the only determinants of a cultural system. A range of other forces are at work. For example, the marketplace, formal and informal institutions, personal dispositions and actions, and civil society campaigns relating to cultural causes and quality of life all impact ‘culture’ to a far greater extent than the measures taken by local and federal governments. Moreover, this kind of cultural policy research is overwhelmingly descriptive.

McGuigan (Citation2004) revisited the five axes of state versus culture relations defined by Williams in 1984. He drew a distinction between ‘cultural policy as display’ and ‘cultural policy proper.’ Williams articulated ‘cultural policy as display’ as follows: 1) national aggrandizement and 2) economic reductionism; under the second, ‘cultural policy proper’: 3) public patronage of the arts; 4) media regulation and 5) negotiated the construction of cultural identity.

In regards to ‘public patronage of the arts,’ Hillman-Chartrand and McCaughey’s typology of State stances (Citation1989) – the Facilitator State, the Patron State, the Architect State, and the Engineer State – also retain its relevance, although recent developments, particularly multiple convergences, and the growth of the cultural industries, have muddled the landscape. Still this typology prevails in teaching and researching cultural policy typologies, most likely due to its clarity and simplicity of application. In short, the Facilitator State funds the arts through foregone taxes or tax deductions, provided according to the wishes of individual, foundation, and corporate donors with the marketplace being the main driver. The United States embodies this model. Most European countries follow the Patron State model. The United Kingdom, honors the ‘arm’s length’ principle. Finally, the Architect State constructs an official system of support structures and measures (i.e. France and The Netherlands). An increasing number of Nordic countries according to Mangset et al. (Citation2008) may be a cross between the two. The final model, the Engineer State, which is ideologically driven and owns the means of cultural production, is almost inexistent, yet many aspects are aspired to in developing countries that practice dirigiste or interventionist cultural discourses.

Until now alternative typologies were sociological and economic, based on more common welfare regime arguments. In recent decades, several different classifications of EU countries have been suggested based on welfare regimes, type of capitalism, and other institutional characteristics. Hall and Soskice (Citation2001) identified a core distinction between two types of political economies: liberal market economies, in which firms coordinate their activities primarily via firm hierarchies and competitive market arrangements, and coordinated market economies, in which coordination relies more heavily on non-market relationships (see also Amable, Barré, and Boyer Citation1997; Amable Citation2000, Citation2003; Dilli and Elert Citation2016). Esping-Andersen’s (Citation1990) original classification is composed of three models: Liberal, Social-Democratic, and Continental, with later studies pointing to the existence of Mediterranean and Eastern European regimes (see Arts and Gelissen Citation2002, Citation2010).

The aim of this article is to assess the validity of those typologies by adopting an empirical approach. We use a large set of cultural policy (mainly economic) indicators to cluster the European Union EU-27 member countries in groups. The variables are presented in the Appendix, . Due to the high-dimensional nature of the problem (i.e. number of variables is larger than the number of units), we adopt an empirical Bayes approach, derived in Partovi Nia and Davison (Citation2012). We specifically focus on four Central-Eastern EuropeanFootnote1 countries: Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, and Slovenia, which are all located in the same part of Eastern Europe and related both historically and linguistically (the latter apart from Hungary). On the basis of this geographical and cultural proximity, we assume they should cluster towa the same ‘model.’ Since the cultural typologies are rare and underdeveloped in these countries and as these countries have slightly different historical trajectories and different institutional structures, the opposite could also be true. Comparing the previous frames, we identify a consistent and strongly separate cluster of Central-Eastern European countries. However, the countries we focus on are not always part of this cluster. For example, for the Czech Republic and Slovenia, we explain with the selection of the indicators in the analysis and cultural policy and economic characteristics of those two countries.

In modern Czech history, the cultural and educational sectors have been closely tied (resulting in a joint ministry for culture and education), continuing a tradition from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the First Republic (1918–1938), culture was primarily associated with the enlightenment, and pursued by voluntary associations rather than the State. After the Second World War, the territory of Czechoslovakia, as it was then known, fell under Soviet communist influence. Until 1989, there was a dense network of ideologically controlled and endowed cultural facilities – libraries, cultural centers, cinemas, theatres, museums, monuments, observatories, etc. This network was centralized in the 1950s and structurally reorganized in the 1970s (for works on Czechoslovakian cultural policy see Marek, Hromadka, and Chroust Citation1970). Some of the central elements of Czech’s cultural policy today can be summarized as follows: the expenditure to support culture is 1% of the state budget expenditures; a culturally diverse society focused on fostering innovation and on using tangible and intangible cultural heritage at the regional level and in local associations emphasizes individual cultural expression. Czech culture became an active agent in the European cultural space, international cultural cooperation was promoted, and European and international awareness of Czech culture increased. An understanding of culture and its consideration as an economic factor are an important component of the state’s economic policy. There is also an increase in citizen participation in cultural events. Private, public, and state institutions also significantly contributed to the support, organization, and funding of the development of cultural services. The state universally supported the influx of additional financial resources into cultural life and used economic, regional, and tax policies to stimulate culture’s active role in the development of society (Petrova Citation2018). In particular, the Czech Republic has recently achieved high levels of economic growth and prosperity in comparison to other European countries. Although publicly funded cultural budgets have recently decreased, it seems likely that in time Czech cultural policy will stand out in comparison to other Central-Eastern European countries due to its assertion of economic policies and snowballing economic development.

In the course of the twentieth century, Slovakia underwent several fundamental social and political changes that had a strong impact on its cultural development and cultural policies. After the fall of the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian empire at the end of the First World War, Slovaks had the opportunity to become a state-forming nation. The creation of Czechoslovakia was the first time in history that international recognition was given to Slovakia’s borders and its capital city – Bratislava. During the socialist period, 1948–1989, cultural policy in Czechoslovakia used culture as an ideological instrument. The fall of the communist dictatorship in 1989 introduced new principles to society’s functioning. In the new democracy, culture was to become an identifier of value that would balance economic and social development. The main documents relating to the Slovak Republic’s cultural policy do not include an expressly defined model of cultural policy such as strategic plans, objectives, and concrete steps. (for more on Slovakian cultural policy see Jaurová Citation2012). The key principles of Slovakian cultural policies are defined in the Programme Declaration of the Government of the Slovak Republic and its specifications in the Ministry of Culture’s scope of work during the period between 2006 and 2010. It advances the perception of culture, in the general sense, as an inevitable precondition to increase the quality of life for citizens of the Slovak Republic. In fact, it unequivocally declares that the support of culture from public funds is a right and, goes further to state that a direct political and ideological interference in culture is unlawful or unacceptable. The government doctrine considers the protection of cultural heritage and direct support and presentation of new authentic artistic works, to be one of the crucial pillars to safeguard and strengthen the Slovak identity. It emphasized that the government of the Republic, when operating in the area of culture and while applying a cultural policy, would observe three fundamental principles: continuity, communication, and coordination (Smatlak Citation2008). While Slovakia has recently experienced more economic growth than other Central-Eastern European countries, its cultural policy features less emphasis on the economic aspects of culture and seems more in line with the general cultural policy structure of other Central-Eastern European countries.

The Kingdom of Hungary was established in 1000 followed by the Ottoman expansion (1526 to 1686) and subsequent Austrian domination. Not until the 19th century was there a successful national revival in which culture played a significant role. After World War I, cultural policy played a strategic role in helping the country overcome its national trauma. After World War II, cultural policy focused on physical and political reconstruction. Up until the revolution of 1956, a crude schematic course imitating the Soviets, dominated the scene. After the suppression of the revolution, cultural dogmatism began to melt away in the early 1960s. From the political turn of 1989–1990, the shaping of cultural policy was influenced by two main sources: precommunist national traditions and modern western examples. It would be difficult to place Hungarian cultural policy into any one of the existing ‘models.’ If anything, the Hungarian cultural policy can be described as eclectic (for more on Hungarian cultural policy see Inkei Citation2012; Bozóki Citation2017). Like other countries in the region, the Hungarian cultural policy has inherited two complementary features, which can be labeled as plebeian and aristocratic (Keresztély et al. Citation2016). Historically, culture has had the social function, or rather mission, to empower the lower classes. This, for example, is reflected by the significant share of socio-cultural programs and institutions in the various cultural budgets, especially at the local levels. At the same time, explicit efforts serve the achievement of cultural excellence, often in the spirit of adding to the pride of the nation (Keresztély et al. Citation2016).

In Slovenia, cultural policy developments have gone through extreme historical changes. Four distinct periods of transition mark the development of cultural policy in the post-war era which also reflects the major ideological transformations of the recent past. The first period from 1945 to 1953, can be recognized as a party-run cultural policy in which the Communist political machine blatantly used culture as a propaganda tool. From1953 to1974, the period of state-run cultural policy is characterized by extreme territorial decentralization with communities that were not independent self-government entities but political units that executed governmental tasks. From 1974 to 1990, the so-called self-management system of devolution in which cultural programming was delegated to the self-managing cultural communities. The supply of cultural services to cultural producers was not, in fact, part of the administration but rather separate legal entities. Finally, in the last period (from 1990 to the present), the parliamentary democracy is distinct with a return of cultural policy to the hands of the state and public authorities.

Some of the chief elements of today’s cultural policy system in Slovenia include:public authorities central role in the area of culture; intensive regulation but weak monitoring; complicated procedures but weak ex-post evaluation; expert advice on financial decisions; heavy institutionalisation with public cultural institutions not part of state or local administration; multiannual program financing; decentralized cultural infrastructure; policy of extensions, in terms of no new construction or any developments in the national cultural infrastructure after Slovenia’s independence in 1991 (for more on Slovenian cultural policies see Čopič and Tomc 1997; Čopič and Srakar Citation2015; Srakar Citation2015). Slovenia is also known for its high level of government support of culture and economic development, which has surpassed all other Central-Eastern European countries for more than a decade.

Based on the brief explanations above, we want to verify our claim, that cultural policies of the selected four countries follow similar paths and belong to the same cultural policy model typology. Even though Hungary and Slovenia have different characteristics (Hungary with eclectic cultural policies and Slovenia with a self-management-based Yugoslav system both of which differs from other socialist systems of Eastern Europe), we also expect to see some divergence of countries belonging to the same cluster. Moreover, we would expect that economic differences between the countries, as noted above (Slovenia and the Czech Republic to stand out for their higher level of economic development compared to other Central-Eastern European countries). Furthermore, we want to verify if these countries belong to the same cluster as other Eastern European countries who are members of the European Union.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the data and methods used for the analysis. Section 3 presents the results, verifications, and discussion of the positions of Central-Eastern European countries while Section 4 concludes by deriving a new, empirical-based typology of cultural policy models, to inspire further research and applications.

2. Cluster analysis, Bayesian approach and basic descriptives

For this analysis, Eurostat data from two main sources are used: Cultural Statistics Pocketbooks (Eurostat Citation2007; Citation2011) and COFOG (Classification of the functions of government) data on public financing of culture. The dataset choice is limited by existing sources: to date, no long-standing time series exists (with equally spaced time points, say, on yearly basis) as a comparable dataset of cultural policy indicators for European countries. The exception is the COFOG, which includes data on public financing of culture (Eurostat Citation2011). Overall, limited data sources are clearly the main shortcoming of this study as well as for other comparative quantitative studies on cultural policies.

This analysis departs from commonly done empirical analyses in cultural policy (Srakar et al. Citation2015). It relies on existing indicators and secondary data sources, as the aim is not based on cultural statistics (in terms of the descriptive analysis of some indicator set) but on statistical modeling possibilities for composing groups of countries. The objective is to derive a more consistent typology, which would be robust in terms of modeling. Moreover, it would therefore not only reflect basic descriptive typologies – which could be prone to many errors and dependencies in the data. Namely, this paper’s modeling is less prone to errors based on the choice of indicators and dimensions (arbitrary upon the decisions of the researcher). As it provides formal modeling, it can easily be robustified with later analyses with a different selection of indicators or methods used. The models we derive are therefore heuristic (not conceptually grounded) and help to understand and explain structural factors that constitute cultural policy systems, that can also be used to forecast the future development of cultural policy systems, as it is based on indicators that can drive the forecast assessment with any other dataset for any other time period.

Cluster analysis is used here with the purpose to divide] partition observations (in our case countries) into groups, assuming that observations belonging to the same group are more similar than observations belonging to other groups. There are a number of ways to attribute observations to clusters. A first and broad approach is to use distance-based (nonparametric) while a second approach is to use model-based (parametric) techniques. Our approach lies between them: a model to define a distance and hierarchical clustering as used in distance-based methods is implemented. Combining parametric (distributional-based) and nonparametric (distribution-free) modeling provides both robustness to the analysis as well as limits possible problems related to both approaches.

In Bayesian clustering, the allocation of observations to clusters is regarded as a statistical parameter (Cheeseman and Stutz Citation1996; Hall, Marron, and Neeman Citation2005; Tadesse et al. Citation2005; Ahn et al. Citation2007). An appropriate prior distribution (usually a multinomial-Dirichlet) is assumed and Bayesian posterior distributions (Gelman et al. Citation2013) the basis for the construction of clusters are calculated. It can be shown that the method produces valid clusters with good statistical properties (Wade and Ghahramani Citation2018).

Below we present descriptive statistics of the included variables for the four selected Central-Eastern European countries. We impute the values for the missing data using multiple imputation methods (Van Buuren et al. Citation2006; Van Buuren Citation2012) as their absence might distort the results of multivariate analysis (Koch Citation2013).

shows the results of general development indicators (we compare only the years 2005 and 2009 due to lack of comparable historical series of data for, a longer and complete period of years). Clearly, Slovenia stands out for its high development in most of the indicators, followed by the Czech Republic, as it features the largest GDP per capita, education levels, activity rate, and the lowest levels of unemployment. Hungary and Slovakia lag quite far behind in all the categories. The differences in the level of economic development between the countries became less pronounced in 2009 with Hungary and Slovakia achieving higher GDP, education (at least for the age category 25–39), and activity rates than previously. The selection of economic indicators is based on previous literature and could be extended, but additional analyses do not provide significant differences in the results.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics – general development

In terms of heritage objects per capita, shows Slovenia as a country with no object so far on the UNESCO listFootnote3 and the Czech Republic as having the highest value here (in terms of heritage indicators, we limit ourselves to the Eurostat Cultural Statistics Pocketbooks datasets, which include only these indicators on cultural heritage for a complete list of countries). Interestingly, this holds also for the level of arts tertiary students, in particular for the Czech Republic, but the differences are significantly smaller in 2009. In terms of expenditure and cultural industries indicators, though, Slovenia again emerges as a clear leader, with all the other three countries lagging significantly behind. This seems interesting as Slovenia does not feature a clear cultural policy or measures but is likely a consequence of the general differences in economic development as well as development orientiations of the included countries.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics – heritage, education, private expenditure for culture and cultural industries’ value added

In terms of cultural employment,Footnote4 the figures shown in are more even, with Slovenia still leading the way in both observed years. Correlation of the level of economic development and level of employment has to be noted, but it also points to the special position of the cultural sector in Slovenia, noted previously. On the level of cultural participation though, it is interesting that the high levels for Slovakia, in all categories, are being followed by Slovenia. Hungary lags quite far behind in almost all cultural participation categories (the values were accessible only for the year 2009) which can be surprising in the light of a large number of social programs noted above. But from we can note a low level of general (employment) activity rate as well which could explain low results in the below category for Hungary.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics – employment and participation in culture

shows the data on public financing of culture.Footnote5 Clearly, Slovenia is far ahead on this category, with others only slowly catching up (naturally, the perspective of only two chosen years for comparison does not allow generalizations based on this). Interestingly, the Czech Republic scores rather low, for the level of central (i.e. state) financing of culture. Hungary scores well and has in recent years become the leader in the level of public financing for culture per capita and in percentage of GDP. The differences seem to be exacerbated in 2009 (in particular for the level of central government expenditure for culture per capita), which is likely a consequence of the global financial crisis of the time.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics – public funding for culture

3. Consistent Eastern European cluster and different four countries’ positions

In the previous section, we examined the basic descriptive statistics of the chosen datasets and observed some apparent similarities and differences. In the following, we cluster the countries based on the chosen (Bayesian) clustering method and observe the final groupings of countries as derived by the formal empirical modeling.

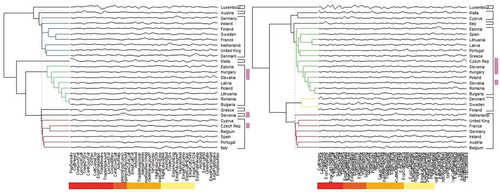

presents the results of two cluster analysis groupings, in so-called dendrogram plots. The left graph for 2005 shows the presence of three large groupings (the straight line represents the cut line where the number of clusters is set). At the top, there is a cluster of Western European countries, including Germany, Ireland, Finland, Sweden, France, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Denmark. The group collects both continental (Germany, France, The Netherlands), liberal (Ireland and the United Kingdom) as well as social democratic (Finland, Sweden, and Denmark) countries from Esping-Andersen’s typology. The second cluster is located in the middle of the graph and consists exclusively of Central-Eastern European countries: Estonia, Hungary, Slovak Republic, Latvia, Poland, Lithuania, Romania, and Bulgaria. It includes the previously observed Baltic cluster (Srakar, Čopič, and Verbič Citation2018) and includes two of our selected countries: Hungary and Slovakia. Connecting to our previous discussion above this shows that Hungary and Slovakia closely follow the general line of cultural policy indicators of the Central-Eastern European countries. The third cluster is at the very bottom of the graph, and consists mainly of Mediterranean countries (Cyprus, Spain, Portugal, and Italy), but collects also the Czech Republic and Belgium. This shows that the Czech Republic differs from other Central-Eastern European countries likely due to its different cultural policy orientations and development path. There are also some outliers, not grouped in any cluster by our method: Luxembourg, Austria, Malta, Greece, and Slovenia. In particular, the latter stands out for its disproportionate attention devoted to culture as compared to other Central-Eastern European countries.

To the right side of are the results for the year 2009. Again, three larger clusters are derived using the method proposed. At the top of the picture is again the Eastern European cluster, which consists of significantly more countries than the one derived for the year 2005, including several Mediterranean ones: Estonia, Spain, Lithuania, Latvia, Portugal, Greece, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria. It includes all four of our selected Central-Eastern European countries which confirms findings from on the decrease in the differences among the four selected countries, which is likely because of the consequence of the financial crisis as well as different cultural policies and general economic development trajectories. The second small cluster in the middle of the picture is the socio-democratic »trio«: Denmark, Sweden, and Finland. Finally, at the very bottom of the picture are Western European countries of continental and liberal Esping-Andersen regimes: The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Ireland, Austria, and Belgium. There are four outliers: Malta and Cyprus are grouped into their very own small cluster, while Luxembourg and Italy are completely single.

Figure 1. Dendrogram plots for years 2005 (left) and 2009 (right), vertical straight line is the cluster cut

shows the contributions of individual variables to the cluster groupings. The variables are to the bottom of the figure and are denoted by heatmap, red denoting the ones with most importance and white the ones with the least importance/weights in our cluster groupings. Clearly, the variable of public financing and GDP are in both sides of the picture, for 2005 and 2009, among the most important variables (the variables have been prestandardized before inclusion in the analysis, so the size of the variables plays no role). This would also be expected as European cultural policies are usually located on the architectural side and rely strongly on public resources. Interestingly, the least important variables are mainly related to employment in culture and cultural industries.

We can also observe that Luxembourg and Malta both characterized as outliers in 2005 and 2009 (), feature a large volatility/instability particularly for the most important variables, which explains the reason for their special status. Luxembourg is known for its extremely high level of GDP per capita, as it is known to be one of the world's highest ones but features much lower values on some other variables.

4. Conclusion: proposal of a new empirical-based cultural policy typology

Apart from interesting findings in terms of the four selected countries and Eastern (and Central Eastern) Europe in general, our analysis provides a ground for a new cultural policy typology, based on indicators on economic and social indicators of cultural economies and policies of the European Union countries. Doing this, we have restricted the analysis to the usage of indicators from Eurostat publications (Cultural Statistics Pocketbooks) which enables easier and more correct comparability in our statistical analysis. While previous classifications were largely based only on theory and/or descriptive analysis, our analysis adds more formal empirical and modeling insights. Although limited in the range of indicators (being focused on the economic and social condition of culture), it provides grounds for an improved approach to the existing classifications. Conspicuously, there is an Eastern country cluster, and considering that we focus on indicators of economic and social development in the field of culture, Eastern countries are different here and trailing behind Western countries, in almost all of the cultural indicators. Furthermore, there are no apparent strong differences within the cluster of Eastern countries in those aspects (apart from occasional outlier countries).

The analysis did not agree with some of the theoretical typologies of the existing literature. We were not able to observe any significant difference between the Patron and Architect countries: the liberal countries like the United Kingdom and Ireland, and the continental ones like France grouped together in all the analyses performed. More evidence for an Esping-Andersen’-type typology is found; however, his conjectures need to be abridged to derive a sensible cultural policy model typology.

We propose to group together all Western European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, France, Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom), which Esping-Andersen groups into three separate groups: continental, liberal, and social-democratic. Empirical analysis provides no evidence of a significant difference in the performance of any of the included countries. What connects those countries are high levels of budgetary and monetary variables and a high level in most of the analyzed variables. There are some outliers such as Luxembourg which we consider to be a special outstanding country.

Moreover, Central-Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia) can also be grouped separately, while no sufficient evidence for the separate Baltic cluster has been found. This model naturally includes all four specifically analyzed Central-Eastern European countries. What connects the countries in this large cluster is low development in most of the analyzed cultural economic and policy variables. The Czech Republic and Slovenia clearly stand out here and sometimes group closer to a the Mediterranean or even Western model.

Although the evidence for this is not conclusive, we suggest to separately include a model of Mediterranean countries: Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, and Portugal. These countries are closer to the Eastern group than to the Western in terms of the level on most of the variables. Finally, there is a second outlier in addition to Luxembourg: Malta. This country is characterized by a special type of cultural system, being reliant strongly on private foundations and cultural industries, and in those terms close to liberal countries. Nevertheless, the high volatility in levels of the variables prevents the countries to be grouped close to any of the above clusters, with probably the closest being the Mediterranean one.

The relevance of the findings is substantial. They provide a different perspective of understanding the structural composition of cultural policies nationally as a basis to formulate a hypothesis of structural similarity of the region that could be further explored in qualitative analysis. We provide empirical and model-based evidence on the composition of cultural policies on the European level. Also, a new modeling approach to the field of cultural policy model typologies is outlined. Cluster analysis is a very general statistical approach and can be improved with the addition of using other Bayesian approaches to cluster analysis (see, e.g. Wade and Ghahramani Citation2018) and a plethora of existing clustering approaches, whether model-based or not, could be used to model cultural policy typologies in the future to provide the field with rich empirical insights. Limitations of applying quantitative approaches to the analysis of cultural policy also have to be noted and triangulation with qualitative analysis and theoretical considerations would have to be applied in the future to come to valid and robust results.

This article contributes to confirming European Union ‘isomorphism’ in terms of similarities between countries, and evidence of existing groupings. Interestingly, isomorphism is present within Western countries – no large differences can be found in the composition of cultural policy indicators based on economies and social development. This has large implications and goes against the prevailing typologies, which advocate for, e.g. a Nordic cultural policy model (Duelund Citation2008) or others. Our findings resemble the Cold War division between East and West and the historic division between the industrial north and the underdeveloped South in its many multidimensional features (see, e.g. Eloranta and Ojala Citation2015). They, therefore, need to be contextualized and, largely, amended with a larger group of indicators, encompassing also other dimensions of cultural policies apart from economic and social development. It must be noted that we do not take into account regional differences – datasets used do not allow for such analysis. But the findings provide a ground for a new line of research on cultural policy typologies which would verify the existing typologies with empirical data and provide ground for improved understanding of difference and similarities between European countries in their cultural policies. Furthermore, they shed light on the role of Central European countries in this context, in particular the four selected ones.

The article features several limitations, the prevalent being in the selection of the indicators used. Following previous literature, the selection is largely based on quantitative economic and social indicators. In the future, it would be opportune to also include qualitative-based indicators, such as the presence and efficiency of cultural policy legislation and sectorial variables based on core arts and less on cultural industries (Throsby Citation2001); significantly improved set of variables related to cultural heritage; and, largely, longer and more complete selection of years included. The analysis is limited by the availability of the statistical data from different sources. Furthermore, methods could be improved, while the results largely concur with previous analyses confirming that the type of the method does not influence the results to such an extent.

The article opens possibilities for research in a largely underresearched area of ‘empirical’ cultural policy, in particular in terms of methodologically sophisticated analyses using state-of-the-art quantitative methods. We hope it will provide ground for significantly more research in this area.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrej Srakar

Andrej Srakar, corresponding author, Scientific Associate, and Assistant Professor at School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana (Slovenia). His research focuses on cultural economics and mathematical statistics.

Marilena Vecco

Marilena Vecco is Associate Professor in Entrepreneurship at Burgundy Business School (France) and Associate Professor to the Carmelle and Rémi Marcoux Chair in Arts Management HEC Montréal (Canada). Her research focuses on cultural entrepreneurship, cultural heritage, and art markets.

Notes

1. In the article, we use labeling Eastern European countries to denote the complete set of countries of Eastern Europe belonging to the European Union. We also use the term Central-Eastern European countries, encompassing Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, and the three Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (Directorate, OECD Statistics).

2. Activity rate denotes the number of active persons (employed and unemployed) as a percentage of the total population (15–64 years old) of the same age (Eurostat Citation2007).

3. Selection of the indicator being listed on UNESCO list is based on comparability: this is one of rare indicators on cultural heritage included in the Cultural Statistics Pocketbooks of Eurostat (Eurostat Citation2011).

4. We define cultural employment as counting all jobs in cultural activities (classified by NACE) and all cultural occupations (classified by ISCO) found in other (non-cultural) sectors.

5. For public financing in culture, we use level of public budget per capita. This usage is justified by some previous analyses on an international level (e.g. Srakar, Čopič, and Verbič Citation2018). The data for the public funding of culture are taken from the Eurostat COFOG database, which also has two additional measures of government funding for cultural services: Percentage of GDP and Percentage of Total Government Expenditure. As there is much less variation in these two variables among countries (cross-section dimension), we use only level of public budget per capita as a variable in our index. Most of the results have also been tested using two other measures and have been corroborated.

References

- Ahn, J., J. S. Marron, K. M. Muller, and Y. Y. Chi. 2007. “The High-Dimension, Low-Sample-Size Geometric Representation Holds Under Mild Conditions.” Biometrika 94 (3): 760–766. doi:10.1093/biomet/asm050.

- Amable, B. 2000. “Institutional Complementarity and Diversity of Social Systems of Innovation and Production.” Review of International Political Economy 7 (4): 645–687. doi:10.1080/096922900750034572.

- Amable, B. 2003. The Diversity of Modern Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Amable, B., R. Barré, and R. Boyer. 1997. Les Systèmes d’innovation à l’ère de la Globalisation. Paris: Economica.

- Arts, W., and J. Gelissen. 2002. “Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism or More? A State-of The-art Report.” Journal of European Social Policy 12 (2): 137–158. doi:10.1177/0952872002012002114.

- Arts, W., and J. Gelissen. 2010. “Models of the Welfare State.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, edited by F. G. Castles, S. Leibfried, J. Lewis, H. Obinger, and C. Pierson, 569–583. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bozóki, A. 2017. “Nationalism and Hegemony: Symbolic Politics and Colonization of Culture.” In Twenty-Five Sides of a Post-Communist Mafia State, edited by B. Magyar and J. Vásárhelyi, 459–489. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press.

- Cheeseman, P., and J. Stutz. 1996. “Bayesian Classification (Autoclass): Theory and Results.” In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, edited by U. M. Fayyad, G. Piatetsky-Shapiro, P. Smyth, and R. Uthurusamy, 153–180. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Collier, D., J. LaPorte, and J. Seawright. 2012. “Putting Typologies to Work: Concept Formation, Measurement, and Analytic Rigor.” Political Research Quarterly 65 (1): 217–232. doi:10.1177/1065912912437162.

- Čopič, V., and A. Srakar. 2015. Slovenia. Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Accessed 06 Aug 2019. http://www.culturalpolicies.net/web/index.php.

- Dilli, S., and N. Elert. 2016. “The Diversity of Entrepreneurial Regimes in Europe.” In 14th Interdisciplinary European conference on entrepreneurship research, Chur, Switzerland.

- Duelund, P. 2008. “Nordic Cultural Policies: A Critical View.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 14 (1): 7–24. doi:10.1080/10286630701856468.

- Eloranta, J., and J. Ojala, eds. 2015. East-West Trade and the Cold War. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities 36. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Eurostat. 2007. Pocketbook Cultural Statistics (2007th Ed.). Brussels: European Commission.

- Eurostat. 2011. Pocketbook Cultural Statistics (2011th Ed.). Brussels: European Commission.

- Gelman, A., J. B. Carlin, H. S. Stern, D. B. Dunson, A. Vehtari, and D. B. Rubin. 2013. Bayesian Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC Texts in Statistical Science. 3rd ed. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Girard, A., and G. Gentil. 1983. Cultural Development: Experiences and Policies. Paris: UNES.

- Hall, P., J. S. Marron, and A. Neeman. 2005. “Geometric Representation of High Dimension, Low Sample Size Data.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B 67: 427–444. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00510.x.

- Hall, P., and D. Soskice, Eds. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hillman-Chartrand, H., and C. McCaughey. 1989. “The Arm’s Length Principle and the Arts: An International Perspective – Past, Present and Future”. Who’s to Pay for the Arts? The International Search for Models of Arts Support. New York: ACA Books.

- Inkei, P. 2012. “Culture and the Structural Funds in Hungary.” Brussels: EENC Paper, August 2012. https://www.interarts.net/descargas/interarts2571.pdf.

- Isar, Y. R. 2009. Cultural Policy: Towards a Global Survey. Culture Unbound, 51–65. Vol. 1. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Jaurová, Z. 2012. “Culture and the Structural Funds in Slovakia.” Brussels: EENC Paper, September 2012. http://interarts.net/descargas/interarts2572.pdf

- Keresztély, K., P. Inkei, J. Z. Szabó, and V. Vaspál. 2016. Hungary. Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Accessed August 06 2019. http://www.culturalpolicies.net/web/index.php.

- Koch, I. 2013. Analysis of Multivariate and High-dimensional Data: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mangset, P., A. Kangas, D. Skot‐Hansen, and G. Vestheim. 2008. “Nordic Cultural Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 14 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/10286630701856435.

- Marek, M., M. Hromadka, and J. Chroust. 1970. Cultural Policy in Czechoslovakia. Studies and Documents on Cultural Policies. Paris: UNES.

- McGuigan, J. 2004. Rethinking Cultural Policy. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Partovi Nia, V., and A. C. Davison. 2012. “High-Dimensional Bayesian Clustering with Variable Selection: The R Package Bclust.” Journal of Statistical Software 47 (5): 142–157.

- Petrova, P. 2018. Czech Republic. Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Accessed August 06 2019. http://www.culturalpolicies.net/web/index.php.

- Said, E. 1978. L’Orientalisme. L’Orient Créé Par l’Occident. Points Essais: Editions du Seuil.

- Smatlak, M. 2008. Slovakia. Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Accessed August 06 2019. http://www.culturalpolicies.net/web/index.php.

- Srakar, A. 2015. “Financiranje Kulture V Sloveniji in Ekonomski Učinki Slovenske Kulture V Letih 1997-2014.” Likovne Besede: Revija Za Likovno Umetnost Special Issue: 5–25.

- Srakar, A., V. Čopič, and M. Verbič. 2018. “European Cultural Statistics in a Comparative Perspective: Index of Economic and Social Condition of Culture for the EU Countries.” Journal of Cultural Economy 42: 163–199. doi:10.1007/s10824-017-9312-2.

- Srakar, A., M. Verbič, and V. Čopič. 2015. “European Cultural Models in Statistical Perspective: A High-dimensionally Adjusted Cultural Index for the EU Countries, 2005–2009. Working paper. Oviedo: Association for Cultural Economics International. 6, 2015.

- Tadesse, M. G., N. Sha, and M. Vannucci. 2005. “Bayesian Variable Selection in Clustering High-Dimensional Data.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 100 (470): 602–617. doi:10.1198/016214504000001565.

- Throsby, D. 2001. Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Buuren, S. 2012. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Van Buuren, S., J. P. L. Brands, C. G. M. Groothuis-Oudshoorn, and D. B. Rubin. 2006. “Fully Conditional Specification in Multivariate Imputation.” Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 76: 1049–1064. doi:10.1080/10629360600810434.

- Wade, S., and Z. Ghahramani. 2018. “Bayesian Cluster Analysis: Point Estimation and Credible Balls (With Discussion).” Bayesian Analysis 13 (2): 559–626. doi:10.1214/17-BA1073.

- Williams, R. 1988. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London: Fontana.

Appendix

Table A Definitions of included variables