ABSTRACT

The present article focuses on the image of Finland in the National Geographic Magazine between 1905 and 2013. The study contributes to the research on national images by answering the following questions: a) how are Finland and the Finns represented in the photojournalist articles in the magazine, b) how has the image of Finland changed over the decades, and c) what kind of cultural, social, and political meanings are conveyed through the image(s)? The research material consists of 37 English written articles including in total 250 photographs and other images. The results show four overlapping but still distinctive phases in the thematic transformation of the image: Finland as a part of the diverse Russian Empire, Finland as a progressive but traditional European nation, Finland as the opposite to the Soviet Union, and Finland as a country of wild nature. The findings are discussed in light of the previous national image research.

Introduction

Over the 20th century, Finland has been in the interests of the United States especially because of its geopolitically significant location next to Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. Paasivirta (Citation1962) has shown that the interest in Finland started to increase in the US in the early twentieth century at the time when Finland was seen as an opponent of Russian oppression. According to Suchoples (Citation2000), the US attitudes changed from suspicion to a willingness to strengthen mutual relations with Finland, and these changes were motivated by US policy towards Russia. The Finnish protestant religion as well as the emphasized ‘Western’ nature of the country appealed to an American audience, although the country was also seen to reflect traditionality which had negative connotations (Jokela Citation2011; Paasivirta Citation1962, 29, 41).

The Second World War firstly marked a growing interest towards Finland fighting alone against the Soviet Union (Paasivirta Citation1962, 110–113). However, the Finnish collaboration with the National Socialist Germany distanced the relationship, and from the US perspective, the years after the Winter War were characterized as suffering from a ‘deteriorating relationship’ (Golden Citation1989, 8). After the war, there existed a dual image of Finland in the US: on the one hand, there were misbeliefs that Finland had fallen under Soviet rule, and on the other hand, the Finnish independence next to Soviet Union attracted positive attention (Paasivirta Citation1962, 140). The recognition of Finland as a member of the Nordic community supported Finns’ aspirations to regain their spot in the international limelight as Americans started to show growing interest in Nordic countries as models for social security and for a ‘third way’ between the two world blocs (Marklund and Petersen Citation2013).

In the present study, drawing on the previous research on national images and photojournalism, we explore how Finland is discussed in the articles of the National Geographic Magazine from the early 1900s to the 2010s. More specifically we ask: a) how are Finland and the Finns represented in the photojournalist articles in the magazine, b) how has the image of Finland changed over the decades, and c) what kind of cultural, social, and political meanings are conveyed through the image(s)?

Vanhanen (Citation2015) has previously analysed the articles published in 1954, 2009 and 2012 from the perspective of the representations of people and nature depicted in them. The present article extends the analysis to cover all articles depicting Finland and Finnishness over a period of a century, from a historical perspective which allows changes and continuities in the image disseminated by and for an international audience to be seen. The specific focus of the study is in the photographs depicting Finland, as photographs hold a special power which lies in their the ability to awake people’s interest and emotions and in the extraordinary high credibility that people tend to give to photographs (Hamann Citation2007, 36). Furthermore, the present study makes a novel contribution by introducing social representations theory as an analytical framework. Social representations refer to everyday conceptions of a certain issue, including values and ideas associated with it (Moscovici Citation1973, xiii). Through an empirical analysis of the image of Finland in photojournalism, we aim to show that the social representations theory, drawing from the idea of social construction of knowledge, can provide suitable analytical tools for the detailed analysis of the evolution of images in photojournalist communication.

The study is structured as follows: we will first make a gaze on the photojournalist practices in the National Geographic Magazine, then discuss the theoretical framework and the context, Finland. After describing the research material and analytical procedure we will present the results of the analysis and discuss them in the light of previous research.

Photojournalism in the National Geographic Magazine

The National Geographic Magazine is the official journal of the National Geographic Society and has been published continuously since 1888. The US-based society was established to succeed a club of researchers interested in exploration, geography, natural sciences, and other fields. The magazine was founded as a forum for reporting the explorations and other practices of the society also towards a broader audience (Schulten Citation2000; Collins and Lutz Citation1992). In the early 1900s the role of illustrations in the journal was increased and it became famous for its high-quality photography reportages (Mendelson and Darling-Wolf Citation2009; Poole Citation2004). Additionally, the scope of the magazine broadened to include science, history, and culture. The magazine has been published in over 40 different language editions over the years. In the present study, we focus on the oldest and the most widely circulated version for an English-speaking audience.

Due to its long history and wide circulation, the contents and discourses in the National Geographic Magazine have been of interest to researchers in various fields. Because of its well-established position, the magazine has been characterized as a central actor in the global mediascape (Parameswaran Citation2002; Collins and Lutz Citation1992). Previous studies on the content of the magazine have, for example, shown how in the early decades of the 20th century the journalism followed the ideals of positivism, direct observation, and documentation but in the 1940s the articles become characterized by a personal, subjective, and experiential style (Pérez-Marín Citation2016). In the second half of the 20th century, trends in the magazine have been characterized as an avoidance of ‘Western’ topics (Lutz and Collins Citation1991) and as having an increasing environmental concern and examination of environmental change (e.g. Ahern, Bortree, and Smith Citation2012; Vanhanen Citation2015). On the other hand, the editorial attitude in general has been characterized as optimistic, encouraging, avoiding controversial topics (Jansson Citation2003), and emphasizing societal progress and advancement (Collins and Lutz Citation1992).

The journal has also been a target of critical voices blaming it for a Western or US-biased representation of the world. O’Barr (Citation1994) has argued that besides its global appearance, the magazine is still closely tied to its origins and its general discourse aims to present the non-Western world to the Western audience. In a more critical tone, Parameswaran (Citation2002, 287) argues that from the postcolonial perspective, the journalism in the magazine (in the late 1990s) ‘echoes the othering modalities of Euro-American colonial discourses’. On the other hand, Lutz and Collins (Citation1991) characterize the magazine’s ‘gaze’ towards non-Westerners as dynamic and having multiple perspectives, constructing a diverse and complex image instead of perpetuating stereotypes.

The articles in the magazine can be described as photojournalism, photo stories, or photo essays, in which a sequence of images are integrated into cohesive narrative (e.g. Kobré Citation2004). The developed printing and camera technology in the early 1900s made it possible to print text and high-quality images together. From the beginning on, the role of the images could be seen impressing the reader and evoking emotions (Mendelson and Darling-Wolf Citation2009). This new form of journalism was closely connected to both the tradition of travelogues and to the tradition of eyewitness accounts (e.g. Raetzsch Citation2015) – both of which can also be seen in the case analysed in the present paper. Additionally, so-called ‘social reportages’ which were produced in order to address certain social problems, had a strong influence on the form of photojournalism (Knöferle Citation2013, 14).

National images as social representations

At the fundamental level, national images could be defined as conceptions of ‘imagined communities’ (Anderson Citation1991) that can be shared by the ingroup (‘the members of the nation’) or outgroup (‘the members of other nations’). Common to these images are that there may be underlying political or economic reasons for reinforcing them but they may also serve a symbolical function to stand out positively from other countries (Clerc Citation2016). In recent research, country images are often approached from the perspective of nation branding, referring to an intentional attempt to create positive associations with a particular country, or from the perspective of foreign images guiding the orientation towards a particular country (Clerc Citation2016; Ipatti Citation2019). Furthermore, national images are often approached from the perspective of current business and marketing interests (e.g. Askegaar and Ger Citation1998; Bannister and Saunders Citation1978) which neglects the fact that the construction and evolution of the image is often a longitudinal process (e.g. Kivioja, Kleemola, and Clerc Citation2015).

The construction and evolution of nation states or imagined communities especially as a result of media communication has for long been in the interest of social sciences (Anderson Citation1991). On the other hand, the research has been criticized for the methodological nationalism, referring to the fact that while deconstructing the socially constructed nature of nations, the research may also strengthen national narratives by focusing on nation states instead of looking broader transnational communities (Wimmer and Schiller Citation2002). Nordic countries are one example of such a transnational community or a region whose self-image as well as image among foreign publics has been an object of study in the past few decades (e.g. Andersson and Hilson Citation2009). However, at least in the case of the Nordic countries, a regional perspective to the study of national images has certain restrictions. As Musiał (Citation2002) and Marklund and Petersen (Citation2013) have shown, from the 1930s to 1970s, the image of a single Nordic country, namely Sweden, strongly dominated the portrayal of the whole region in the American press and literature. Less space was left for smaller and younger Nordic countries, Finland and Iceland; for a long time, they were not even considered belonging together with the Scandinavian countries Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. Furthermore, as Andersson and Hilson (Citation2009, 224) have pointed out, ‘the Nordic model itself became nationalized, so that scholars and politicians alike began to talk of a separate Finnish model […] a Danish model […] and a Norwegian model’ from 1990s onward. For these reasons, while keeping the criticism of methodological nationalism in mind, we argue that images of individual countries or nation states are still relevant and justified research subjects beside broader communities.

Definitions of national image attach the concept often to cognitive beliefs defining it, for example, as: ‘Generalized images’ (Bannister and Saunders Citation1978, 562) having an affective dimension or ‘evaluative significance’ (Askegaar and Ger Citation1998, 52). These definitions correspond with Moscovici’s (Citation1973, xvii) description of social representations as shared conceptions combining ideas and values on a certain topic and having an evaluation guiding how people perceive the topic in question. However, social representations are broader phenomenon than just a cognitive structure. We argue that the additional value social representations theory brings to national image research is to understand national images as socially shared conceptions constructed within social communication like journalism (Höijer Citation2011). This approach is justified as our interest is in conceptions constructed between people – for example, in the present study in relations between the journalists and their (expected) audience. Furthermore, social representations theory includes the idea that social conceptions are always historical: they do not emerge from scratch but are based on previous images (Bauer and Gaskell Citation1999). Thus, the approach is suitable for tracing the roots of certain representations and analysing the evolution of those conceptions (Hakoköngäs et al. Citation2020).

Photojournalism constructing national images

Before the rise of television, magazines employing photographs had an important role in familiarising readers with new topics such as distant countries (Raetzsch Citation2015). Höijer (Citation2011) has argued that a social representations approach provides a conceptual framework for the analysis of the social meaning-making process in the midst of societal and political interests in the media communication. Similarly, to, for example, Hall’s (Citation1999) conceptualization of representation as a result of cultural meaning-making, Moscovici’s theory focuses on the processes through which something abstract and distant is made tangible and understandable in social communication. However, as Höijer (Citation2011) notes, unlike Hall, Moscovici provides a detailed description of the processes included in the meaning-making and analytical tools to be employed in the analysis.

In photojournalism, the meaning-making happens by combining the visual choices of the photographer, the textual choices of the author of the article, and the layout or the mode of presentation. For example, Poole (Citation2004) has noted how in the National Geographic Magazine the articles are constituted of three elements: photographic lines, captions, and text. The role of the plain text is to deliver the substance, while the photographs provide an emotional impact, and the captions connect the two previous elements. Martikainen (Citation2019) has argued that visual journalism is a combination of compositions aiming to serve certain intentions, and the researcher should pay attention to exclusion and inclusion of information in the journalist communication.

The conceptual tools the social representations theory offers to analyse this kind of multimodal material are two interrelated processes through which conceptions of socially salient issues are constructed. These processes are called objectification and anchoring (Moscovici Citation1984). Objectification refers to the process in which something abstract is turned into something tangible for example through photographs and a journalist’s description. Anchoring, in turn, refers to the process in which a topic is given a meaning. To take an example from Vanhanen’s (Citation2015) research on photojournalism in the National Geography Magazine, objectification could include presenting selected photographs visualising the topic, for example natural environment in Finland. Anchoring could include describing the presented photographs to depict a place unoccupied or untouched and associating it to wider networks of meaning such as recovering nature or environmental concern. Höijer (Citation2011) lists naming and metaphors (e.g. ‘terrorists’), familiar emotions (e.g. climate worry), basic thematic categories (e.g. culture/nature) and antinomies (e.g. fear/hope) as subprocesses of anchoring.

Finnish image building efforts from the Russian period to the European Union era

Finland was a part of the Russian Empire for over a century, until reaching the independence in 1917. In the interwar period, newly independent Finland tried to convince international audiences that despite its geographic location, the country was a firmly Western democracy (Jokela Citation2011). This message was further backed up by the increasing acceptance of Finland as one of the modern, progressive Nordic countries, by both Nordic and prominent Anglo-American writers (Musiał Citation2002, 121–129).

In the WWII, the country fought against the Soviet Union maintaining the independence in the end. During the war, Finnish foreign propaganda propagated Western audiences with the idea of Finland as defender of Western civilization, Christianity and the values associated with this heritage (e.g. Raento and Brunn Citation2008), and Finnish public relations organizations funded the visits of foreign journalists and photographers to Finland during the wartime in order to promote the Finnish cause (Paasivirta Citation1962, 111–112). After the war, Finland aspired to balance politically between the Eastern and the Western blocs. Maintaining friendly relations with the Soviet Union but at the same convincing the West that Finland was a free democracy with the same Western values as before the war became the top priority of Finnish politics. This balancing act led to coordinated ‘image politics’ striving to construct an image of a ‘progressive Finland’ which served political, economic, and even symbolic need in an attempt to gain respect among other independent nations (Raento and Brunn Citation2008; Jokela Citation2011).

The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s allowed and, according to Finnish officials, also required updating the national image. The economic depression in the 1990s broke the ideals of welfare state built in the previous decades. On the other hand, the integration in the European Union provided material for a new, more international image as Finland had become an EU member in 1995 (Raento and Brunn Citation2008).

Material and method

The data for the present study was collected from the electronic archive of the National Geographic Magazine in 2018. An OCR-based (optical character recognition) search tool was used to find articles in which the terms ‘Finland’, ‘Finnish’ and ‘Finns’ appeared. In total 37 English written articles from the years 1905 to 2013 were found. PDF-versions of these articles were downloaded for a more detailed analysis. The material collected included both longer photojournalistic articles focusing on Finland, as well as reportages in which Finland was mentioned as one country among others. Shorter photojournalist contents like pieces with only an image or a couple of images with a caption locating the photograph in Finland were included in the analysis as well. The material consisted in total 250 photographs and other images associated with Finland. The analysed articles are listed in Table A1.

To answer the first and the second research questions concerning the contents and the change of the image, a thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was employed. The aim of the method was to identify common patterns within the data by: a) familiarizing the researchers with the material, secondly b) generating initial codes describing the contents (e.g. ‘students’, ‘a farmer’), c) combining the initial codes into broader and more abstract themes (e.g. ‘education’, ‘countryside’), and finally d) reviewing and defining the set of themes that contribute to the construction of the image of Finland in the Magazine (e.g. ‘Finland as a civilized but traditional European nation’). The second, third and fourth steps of the analysis included the theoretical reading of the material by employing the conceptual tools of social representations theory.

In practice, by generating the initial codes describing the contents of the photographs and the other images, the objectifications were identified. Objectification refers to the way something abstract is made tangible by presenting its (selected) visible features. By defining the more abstract themes, anchorings were identified, in other words, the associations and meanings conveyed by naming, metaphors, antinomies, thematic categories or familiar emotions. (Moscovici Citation1984; Höijer Citation2011.) For example, a photograph depicting a massive granite building (A11, 509) was first given initial codes of ‘Urban scene’ and ‘Parliament’ (indicated by the caption ‘Finland’s new parliament building’) which define the main objectifications that the photograph implements. Next, the anchorings of the photograph were interpreted: here, the photograph represents the ideas of democracy and progression through a visual metaphor. These interpretations were strengthened by the context: the article is titled as ‘The Farthest-North Republic’, where anchoring through naming is being employed, and in the caption the author enthusiastically describes the electronic voting system of the Finnish Parliament. Finally, along with other photographs relating similar themes, the example photograph was interpreted to contribute to the construction of the representation of ‘Finland as a developed European nation’.

Social representations theory was also employed to answer the third research question, that is, to identify the cultural, social, and political meanings conveyed through the material. Every article is a result of several choices, and for example the choice to depict the Parliament house in the 1930s and raise it as a symbol of democracy and progress resulted in a different image of Finland than focusing on other aspects such as social problems or political discrepancies of the time. The identification of these subtle meanings required placing the analysed material in the historical context which is described within the identified themes in the next section.

Results: the evolving national image of Finland

As a result of thematic analysis accompanied with theory-driven reading of the material, we identified common patterns in the National Geography Magazine articles dealing with Finland. The magazine viewed Finland from the angles of societal development, Christian and Western traditions, exoticism, and wild nature frequently. The differences between Finland and the Soviet Union were also emphasized. These ways of depicting the country were partly overlapping, but we could also identify broader themes that correspond to different periods of Finnish history from the 1900s to the 2010s. We named the identified themes – and hence, the different aspects of the image of Finland – as: Finland as a part of the diverse Russian Empire; Finland as a progressive but traditional European nation; Finland as the opposite to the Soviet Union; and Finland as a country of wild nature.

The image themes and the time periods of their occurrence, as well as the main objectifications and anchorings, are presented in . As the table shows, the shifts between the themes are not clear-cut but gradual. In fact, the analysed articles do not exist in isolation, but the authors often refer to the magazine’s previous issues in which Finland has been depicted. This notion of subtle change corresponds with Bauer and Gaskell’s (Citation1999) idea of social representations as temporal constructions which are not replaced suddenly with a new representation but are gradually complemented by new elements resulting in due course in a shift in the meaning of representation. Hakoköngäs et al. (Citation2020) argue that these changes in the representation can be traced back to the change in the social context from which the social representations emerge.

Table 1. National image of Finland in the National Geographic Magazine 1905–2013 (N = 37)

Next, we will describe the central features of each theme and pick out the cultural, social, and political meanings conveyed through the photojournalist practices of the magazine. The abbreviations A1–A37 refer to the analysed articles listed in Table A1.

Finland as a part the diverse Russian Empire (1905–1917)

Finland was a Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire until 1917, and the last five decades of it were a time of increasing political autonomy and rising Finnish national thinking. In the early 1900s, Finns aspired to gain sympathy in international newspapers in their fight against the Russian policy of limiting the autonomy of the Grand Duchy. Especially the Finnish pavilion at the Exposition Internationale in Paris in 1900, and Finland’s opening parade under the Finnish national insignia at the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912, were steps in the publicity project that emphasized Finnish culture and separate history from the mainland Russia (Raento Citation2006; Ashby Citation2010). Additionally, the effects of the WWI on the Russian Empire sparked the US interest towards Finland (Paasivirta Citation1962, 52–53).

Between the years 1905–1917, six articles in which Finland was depicted were published in the National Geographic Magazine. Most of the articles addressed the social and cultural diversity of the Russian Empire (A1, A3, A4) or the diversity of immigrants arriving in the United States (A2, A5). Lapland as a far-away area was mentioned in 1914 by Gilbert Grosvenor who used it as a demonstration of the vastness of Russia: ‘Russia is not a state; it is a world. (…) Its history borrows from Mongol-land, Lapland, Finland; from the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea, and the Okhotsk Sea,’ (A4, 423). However, women’s suffrage was also used to mark the positive difference between Finland the rest of Russian Empire: ‘Although at the time the suffrage was granted it seemed to people outside Finland radical and even revolutionary, in Finland itself the change was looked upon as a merely natural process of political and social evolution … ’ (A3, 487)]

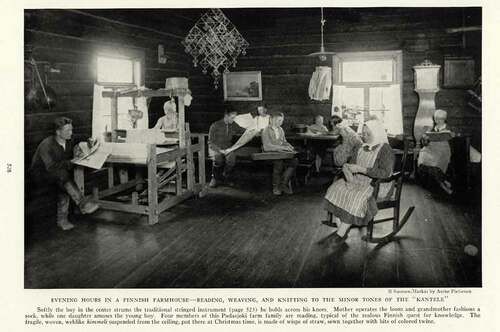

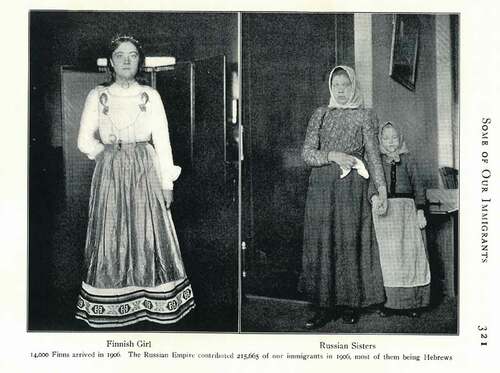

The positive distinctiveness of the Finns was constructed also in articles in which Finland had a minor role. Articles depicting immigrants arriving in the United States had an ethnological approach in introducing different ‘folk types’. In such introductions, Finns were represented as separate folk from Russians as shown in the photographs in . The juxtaposition of the photographs shows a ‘Finnish Girl’ on the left and ‘Russian Sisters’ on the right. The visual objectification constituted by the photographs and layout creates a striking contrast between the girls: the Finnish girl is dressed in a decorated white folk costume and jewellery while the physically smaller looking Russian girls wear modest looking clothes and scarfs (A2, 321). In this example, through a thematic antinomy, Finnishness is anchored in ethnically distinctive culture, and prosperity, in opposite to the unimpressive appearance of the depicted Russians. In another article, a photograph of a wealthy looking Finnish family is accompanied with the characterization: ‘Hardy, self-reliant, industrious, they make good citizens of the type that Scandinavia sends us’ (A5, 116; same image: A2). Besides anchoring Finnishness to a positive connotation of diligence, the author anchors through naming Finns as Scandinavians instead of Slavs.

Finland as a progressive but traditional European nation 1910–1954

After the independence in 1917, Finns sought to capitalize on the positive international reputation they had already won. According to Clerc (Citation2016) the construction of Finland’s image in the 1920s and 1930s was a combination of improvisation and organized propagation, serving both political and economic interests as well as the young republic’s need to form a national identity. In general, Finland’s image abroad consisted of the ideas of Finland as a land of winter, high levels of education and sports, as well as the idea of Finland as a Nordic country. Additionally, architecture and design as cultural products became part of the image (Ashby Citation2010). In the National Geographic Magazine, the image of Finland during this period was twofold, characterized by the dichotomy between progressiveness and traditionalism.

Progressiveness

The image of the Finnish progressiveness started to take form already during the Russian era when the article ‘Where women vote’ (A3) in 1910 focused on women’s suffrage and the fact that Finland was the first country in Europe to give women the right to vote and eligibility for election. In this article politically active women were the objectification of Finland. Anchoring employed thematic category (progressive/outdated) depicting Finland as the country of societal progress – compared to Russia and most of the other countries of the time. In the next decade, the image came to include three main components: education, gender equality and urbanity. In the National Geographic, the Finnish educational system was praised already in the 1910s for providing ‘excellent schools for girls’ (A3, 488), and in 1914, a caption of a photograph depicting a well-dressed urban family states: ‘The people of Finland are the best educated of any in Russia, illiteracy there being no higher than in Western Europe’ (A4, 511) which anchors Finland rather to Western European than Russian cultural sphere. From the 1920s onwards, the ‘famous university’ (University of Helsinki) was depicted in several articles (e.g. A7, 163) as an objectification of the high level of the education. As a new feature in the ‘folk type’ characterisation, a ‘desire for education’ was introduced, for example by Alma Luise Olson in 1938 as the Finnish ‘quest for knowledge’ (A11, 528), and it was still alive in 1982 when the National Geographic wrote, ‘Helsinkians are among the best read people in the world’ (A21, 252). The high-level education was often connected to gender equality and they were objectified through photographs depicting women in action: a female tram conductor in the 1920s (A8, 607; A11, 529), members of women’s organisations the Martha League, and Lotta Svärd in the wartime (e.g. A14, 250), and happy-looking nurses skiing and bicycling to work in a post-war article (A15, 244).

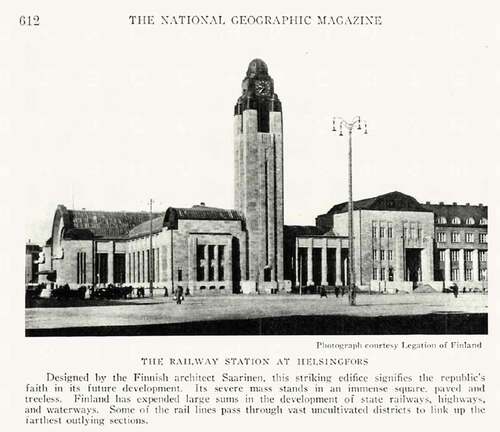

The idea of Finnish progressiveness was also made tangible through the photographs depicting the capital Helsinki. Helsinki as an objectification of urban development was introduced for the first time in 1914 when the article ‘Young Russia’ showed two full-page pictures depicting the Harbour of Helsinki and the Lutheran Cathedral, and described the city as ‘a busy and growing metropolis’ (A4, 510). The other often visualized places in Helsinki were the market square and harbour (e.g. A4, A7–A11; see also: A1); the photographs of them objectify urban life and mercantile activity.

The photographs of new architecture were explicitly anchored to an idea of societal progress, as demonstrated in . The photograph depicts the main railway station in Helsinki, which was opened in 1919. The tower of the station reaches up to the sky and accentuates the size of the building. In the anchoring process, the building is used as a visual symbol of progress, and according to the author, it ‘signifies the republic’s faith in its future development’ (A8, 612). The railway station was presented in several articles (e.g. A8, A10, A11, A14, A19) and was described as signifying strength (A10, 799) and ‘Finnish aspirations’ (A11, 503). For the US-based audience the building was a meaningful object as its architect Eliel Saarinen emigrated to the US (A10, A11, A19; see also: Paasivirta Citation1962, 102). In other words, the name of the architect was exploited to make the distant Finland more familiar to foreign readers. The important detail in the photograph in is that it was provided to the National Geographic by the Finnish Legation, which shows that the Finns actually managed to feed material to the magazine in the 1920s and thus actively contributed to the construction of their image abroad.

Traditionalism

Along with representing the Finns as being urban and educated, the articles in the magazine provided another dimension to Finland’s image by emphasizing the long history of Finns and depicting agricultural life in rural Finland. According to Paasivirta (Citation1962, 95), rural Finland was often seen in the US negatively as primitive. However, in the National Geographic, the rurality of Finland was not separated from the idea of progressiveness but subtly connected to it. As a result, Finnish history and rusticity amounted to charming traditionalism, not off-putting backwardness. This was done for example through emotional anchoring, as demonstrated in .

Image 3. ‘Evening hours in a Finnish farmhouse – reading, weaving and knitting to the minor tones of the “kantele”’. Photograph: Aarne Pietinen/Suomen-Matkat. (A11, 528).

The photograph in shows a scene of everyday life in the Finnish countryside in 1938. In a rustic but clean and decorated wooden house, a family of several generations, wearing simple clothing, spends their ‘evening hours’ in the productive work of weaving and knitting, but also educating themselves by reading. The idyllic moment is accompanied by a traditional Finnish instrument, the kantele. Even though the objectification is distinctively different from the urban scene in , the details of this photograph objectify positive elements of traditionalism – nurturing old customs (e.g. kantele), close social relationships, tranquillity – and the caption anchors them to the positive attributes like diligence, and strive for education: ‘the zealous Finnish quest for knowledge’ (A11, 528). The is also an example of another successful attempt of the Finns to disseminate selected messages of themselves to the international audience. The photograph was taken by the Finnish photographer Aarne Pietinen and was provided by the Finnish tourism agency ‘Suomen-Matkat’. Pietinen’s photographs were used also in other articles of the magazine.

The southwestern archipelago of Ahvenanmaa (Åland) represents Finnish traditionalism in several articles from the 1920s to the 1940s. The location of the archipelago made it possible to objectify long historical connections between Finland and Scandinavia, as mentioned in one article depicting President Svinhufvud and an Ålander shipowner: ‘In the veins of many sea-roving Ålanders flows the blood of the ancient Vikings’ (A9, 102). The photographs showing castle ruins, Lutheran churches and the old but neat farmhouses (e.g. A9, 122–123, 127) anchor the image to similar positive attributes than the above.

The reason why the editors of the magazine selected this Swedish-speaking area to represent the Finnish countryside had underlying political interests: due to its strategically important location in the Baltic Sea, the area was given autonomy in the 1920s by decision of the League of Nations, and the authors emphasized this interesting detail for their US-based readers. Due to the Winter War, the political interest towards the area grew, and for example the portrait of a smiling girl published in February 1940 is accompanied by the following text: ‘The blond maiden lives on the strategic archipelago (…) Now the Soviets wants them for a naval base.’ (A14, 243) explicating the political interest behind the reports on Ahvenanmaa.

The articles covering Lapland and the Saami people also represent old Finnish traditions but through the lens of exoticism. International reportages on the Saami way of living were not favoured by the Finnish authorities as they did not fit the idea of the modern homogeneous Finnish nation they wanted to promote (Raento and Brunn Citation2008). However, wintry Lapland was of interest to international journalists (Lähteenkorva and Pekkarinen Citation2008, 60–61). In the articles of the National Geographic focusing on the Saami people, their way of living was considered positive traditionalism, too. The authors stated that besides their ‘mysterious’ habits and nomadic way of living, the Saami people are also civilized (e.g. images of school children, A12, 673, 676) and Christians who had rejected their old beliefs over a century ago (e.g. A12, 654). In general, references to the protestant religion, such as images of Lutheran churches were used to represent Finnish European history and Christian values (e.g. A8, A11, A17; see also: Raento and Brunn Citation2008).

Finland as the opposite to the Soviet Union 1940–1989

The Finnish public relation organizations were employed to gain international sympathy during the WWII (Clerc Citation2016). In the US, the Winter War attracted positive attention towards Finland including romantic metaphors of ‘David’ Finland against the ‘Goliath’ Soviet Union (Paasivirta Citation1962, 110–113; see also Raento and Brunn Citation2008). The wartime article in the National Geographic Magazine used a photograph of a historical castle to anchor Finland to the idea of being a defender of Europe, accompanied by the text: ‘Modern artillery could soon destroy Olaf’s castle, formerly one of Europe’s strongest’ (A14, 254) employing antinomy between the past and the present as a form of anchoring.

Finland maintained its independence in the war, unlike the Baltic countries, and a determined image management continued through the following Cold War era. In the National Geographic, unbroken curiosity towards Finland characterized the Finland-themed photojournalism in the following decades. In addition to being seen as a progressive nation Finland was represented as an important bridgehead of Western culture next to the Soviet bloc. The political background of this image was explicitly stated for example in an article in 1964 which stated: ‘For a long time the Finns have lived on the difficult spot in northern Europe where the West begins’ (A18, 280) anchoring Finland through naming to belonging to ‘the West’. Finland was even more strongly than previously anchored to Nordic countries. For example, one article published in 1948 noted: ‘Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway (…) remain friends despite varying wartime experiences,’ (A16, 184). The blue cross in the Finnish flag was used as an objectification of the Nordic connection as well as the Christian religion (A16, A19).

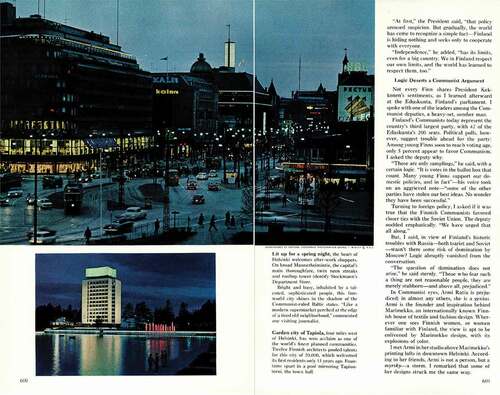

Despite the – sometimes successful – Soviet attempts to interfere in Finnish domestic policy, Finland remained a democratic market society that maintained relations with both the East and the West during the Cold War decades. In the National Geographic, the capital Helsinki, which had earlier represented Finland as a progressive nation, was now shaped into a symbol of freedom in contrast to the Soviet Union. This was done by objectifying post-war Finland with urban images of Helsinki and by employing anchoring through thematic opposites free–restricted, democracy–totalitarianism, market society–socialism, though the latter opposites were only implicated in the text and images.

An example of anchoring Finland to freedom is demonstrated in . It shows a spread from the article ‘Finland: Plucky Neighbor of Soviet Russia’ (1968) depicting a night scene of the Helsinki city centre in darkness lighted up by shop windows and advertising signs. The advertising and mercantile activity detail of the photograph anchors Finland to the free market society in implicit contrast to socialism. The journalist uses anchoring through metaphor by calling Finland a ‘modern supermarket perched at the edge of a tired old neighborhood’ (A21, 601) in which the neighbours refer to the Baltic states under the Soviet rule. The lower photograph shows a modern tower block objectifying new urban architecture. Similar to the forty years older photograph in in the post-war articles the modern architecture anchors the image to the idea of progressiveness. A positive tone was extended to the characterisation of Finnish people by stating that ‘despite the loss of territory and huge reparations imposed by the Russians, the Finns are cheerful, and move forward as a free and independent nation’ (A16, 624) in which emotional anchoring is employed. In another article, the publication stated that ‘Finland today shows what free men can do,’ (A19, 587). The latter article was considered so valuable in Finland that the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs ordered 5,000 copies of it for image building purposes (Lähteenkorva and Pekkarinen 2008, 246–248).

Finland as a country of wild nature 2002–2013

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 changed the political and economic context that had motivated the Finnish image construction since the 1920s. Finland sought to strengthen its European connection and in 1995 became a member of the European Union. The 1990s marked the clearest shift in the image of Finland conveyed in the National Geographic Magazine so far. It seems that while in the previous phase, viewing Finland was motivated by the political intentions of the Cold War, the dissolution of Soviet bloc in Russia and the Eastern Europe resulted in a loss of interest towards the Finnish society in the magazine. Firstly, there was a decade-long gap (1992–2002) in reports on Finland, and secondly, when the country was again found to be of interest in the 2000s, the role of the society was reduced to the minimum. Twelve pieces about Finland were published in the magazine between 2002 and 2013, and they focus almost unequivocally on nature (an exception A35; Vanhanen Citation2015; see also Raento and Brunn Citation2008).

Even though the change in the contents of the articles was distinctive, the idea of Finland as a country of wild nature has its origin in the earlier decades. Finnish natural landscapes had been depicted in the magazine already in the 1910s (e.g. A6) but nature had remained in the side-role characterizing the geographical location of the country in the North and the Finnish people’s close-to-nature lifestyle (e.g. A19, 338; A21, 597). The environmental concern strengthened nature’s role in the articles in the 1980s, and in 1989, a reportage on the Baltic states shows a photograph depicting Greenpeace activists protesting against marine pollution in front of a Finnish chemical company (A23, 624) – an objectification of environmental concern loaded with critical tones unpresented in the previous decades.

In the 2000s, problems were pushed again into the background and replaced with nature aesthetics as well as signs of the resolution of environmental issues in Finland. This is demonstrated in which shows a spread from an article focusing on the Oulanka nature park in Finland. An aerial photograph depicts a swamp without any visible signs of human interference, thus objectifying the wild untouched nature. In the caption, the meaning of the image is anchored to environmental concerns and hope, as the caption states that similar areas are ‘slowly being destroyed elsewhere in Scandinavia’ but parks like Oulanka are helping in preserving them (A29, 68). Several other articles in this phase have even more positive tones: nature photographs of wild animals such as wolverines (A25), owls and bears (A28; A34), and whooper swans (A29) represent the recovering wildlife, as one article states: ‘As Europeans abandon farming for other livelihoods, and the countryside for cities, wildlife is reclaiming lost territory’ (A28, 133). The idea of humans stepping aside is most explicit in an article showing Finnish photographer Antti Leinonen’s pictures of wild animals in abandoned Finnish houses: ‘The people moved away. And the animals moved in,’ (A32, 137; see also A33, 16). The photographs objectify the renewed wildlife and anchor to the idea of untamed nature unoccupied by humans. This is in clear contrast to the earlier phases in the magazine where the modern, yet traditional Finnish society was an emphasized aspect of the image of Finland.

Discussion

In the present article, we have analysed the construction and evolution of the image of Finland in the National Geographic Magazine from 1905 to 2013. By employing a thematic content analysis along with the theoretical tools provided by social representations theory we identified four distinctive but interrelated phases in the development of the image: Finland as a part of the Russian Empire; Finland as a civilized but traditional European nation; Finland as the opposite to the Soviet Union; and Finland as a country of wild nature. Although the present analysis focused on the image of a single nation in journalistic writing, the social and political interests behind journalism open broader views of the construction and dissemination of an image. The portrayals of a nation can be interpreted to reflect signs of wider discussions and interests in areas such as urbanization, the progress of democratic societies, tensions in international relations, and global environmental concerns.

The analysis indicated that the American representation of Finland to the US-based (and more broadly to an English-speaking) audience during the first phase (1905–1917) was motivated by the transformation of the Russian empire, and the outcome corresponded with the Finns’ own intentions to positively distinguish themselves from Russia. During the next phase (1910–1954), a positive image of Finland as a progressive but traditional European nation was constructed, and Finns managed to contribute to this process by providing selected photographs to the magazine. We can detect an interest in the Finnish geopolitical situation underlying the America portrayal of Finland as a country neighbouring the Soviet Union, but this was not as conspicuous as later (see also: Paasivirta Citation1962, 42). The Second World War marked the emergence of the next phase in the evolution of the image (1940–1989) as Finland was represented as an opposite to its Soviet neighbours. This benign picturing of Finland corresponded with the mutual interest of maintaining good relations between Finland and the USA (Golden Citation1989, 8). The fundamental change in global politics in the 1990s resulted in a loss of American interest in Finland and its society. In the 2000s, a new layer was added to the image: Finland as a country of wild nature. Environmental concerns constituted the motivation for the most recent phase in the evolution of the image (2002–2013). The findings correspond with the previous general characterizations of the National Geographic Magazine’s editorial attitude as optimistic and encouraging, focusing on development instead of problems (Collins and Lutz Citation1992; Jansson Citation2003), and on the rise of environmental issues as a content of the magazine since the 1980s (Vanhanen Citation2015; Ahern, Bortree, and Smith Citation2012).

Our findings also correspond with the previous research on visual construction of Finland’s self-image for example in postage stamps (Raento and Brunn Citation2008; Raento Citation2006) or tourism advertising (Jokela Citation2011) where especially noticeable is the Finnish attempt to show a positive distinction between Finland and Russia or the Soviet Union by emphasizing, on the one hand, Finnish modernity and, on the other hand, traditionality, and Protestant religion. Also, embracing nature as a part of national self-image was previously noted for example in the analysis of Finnish stamps (Raento and Brunn Citation2008). The present findings indicate that the image disseminated by Finns to a foreign audience followed the lines of the identity-political iconography that was targeted at Finns themselves. The image of Finland as a progressive Nordic country was supported also by the joint image building efforts of the Nordic countries. The Nordics sought to strengthen the image of themselves as an appealing community of welfare states that had found resonance among the American audiences already in the early 20th century. (Musiał Citation2002; Marklund and Petersen Citation2013.)

Furthermore, corresponding with Bauer and Gaskell’s (Citation1999) argument that social representations always have a history, and their recommendation to approach them in a longitudinal or cross-sectional setting, the present findings show that the different phases in the evolution of Finland’s image in the National Geographic Magazine did not emerge from scratch but always had their roots in the previous notions of Finland. In the course of over a century, the image of Finland was revised in the magazine in interplay with the current social and political situation, expected interests of the audience, as well as image building efforts of the Finns themselves. This demonstrates how social representations theory provides a useful approach in the analysis of photojournalism by focusing on the social meaning-making and its subprocesses objectification, and anchoring in different forms. As noted by Höijer (Citation2011), the employing of the analytical tools offered by the theory enables the identification of the nuanced ways in which certain meanings are created and conveyed in journalistic practices effectively via a combination of photographs and accompanying texts. The application of the theory is not limited to present-day forms of communication, but, as shown in the present study, the theory may also inform us about the historical evolution of socially mediated images.

This study is not without limitations, however. In particular, we lack information on the editorial processes behind the journal, although some general characterization has been provided (e.g. Collins and Lutz Citation1992) as discussed above. Secondly, we have only a few references on the Finns’ own active role in shaping their image in the magazine. However, already the few photographs provided by different Finnish operators indicate that Finns managed at least from time to time to make their own agenda visible in the magazine. Furthermore, the fact that in the 1960s Finnish officials ordered a large number of a certain issue of the magazine for image building purposes (Lähteenkorva and Pekkarinen 2008, 246–248) shows that Finns recognized the National Geographic Magazine as a prestigious forum in making Finland known abroad. The cases mentioned above also show that Finns understood the power of visuality in making sense of the world. As Lähteenkorva and Pekkarinen (2008, 18) state, this was realized in Finland relatively early, and especially today, pictures are deliberately used as a resource in the Finnish foreign politics (Koski Citation2005).

Even though the analysed articles covered different areas in Finland, from the capital Helsinki in the south to the Ahvenanmaa archipelago in the west and Lapland in the north, in reality, most of the country was left without visual exposure. The emphasis on Helsinki also characterises Finns’ own visual representations of the country (Hakoköngäs and Sakki Citation2016; Jokela Citation2011), excluding, for example, Karelia, the southeastern region of Finland, that was geopolitically critically located close to the Soviet border (see also Raento Citation2006).

Conclusions

In the present paper, we have shown how the image of Finland has evolved over a century in the photojournalistic communication of the National Geographic Magazine. The theoretical reading of the contents of the magazine from the perspective of social representations theory enabled the analysis of social meaning making through the processes of objectification and anchoring especially in the photographic content of the articles. The approach enriches the research of national images by treating them not only as entities motivated by business and marketing interests (e.g. Askegaar and Ger Citation1998; Bannister and Saunders Citation1978) but also as more general structures that people construct and share in social communication and employ to make sense of the nature of abstract topics (Moscovici Citation1984), like a character of a far-away nation. Following the criticism towards ‘methodological nationalism’ (Wimmer and Schiller Citation2002), in the future, the role of the photojournalism in constructing and disseminating social representations of nations, areas, and locations could be approached from a comparative perspective, for example, by analysing differences and similarities in the portrayals of the Nordic countries. The image of the Saami people in the magazine was only briefly mentioned within the present study but would also deserve a much deeper exploration. The comparison between the ways indigenous people are represented in the press would allow an analysis of more common attitudes towards different minorities, a topic which is of great political actuality today (Wheelersburg Citation2016). Furthermore, the study of such a central actor as the National Geographic Magazine in the global mediascape (Parameswaran Citation2002; Collins and Lutz Citation1992) would offer glimpses into the processes and policies of world-wide photojournalism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eemeli Hakoköngäs

Eemeli Hakoköngäs (Dr. Soc. Sci., University of Helsinki) is a lecturer in Social Psychology at the University of Eastern Finland. His research interests include visual rhetoric, collective memory and political psychology.

Virpi Kivioja

Olli Kleemola (Dr. Soc. Sci University of Turku) is a postdoctoral Reseacher of Contemporary History at the University of Turku. His research interests include the use of photographs as historical sources, history of propaganda and the so-called “New military history”.

Olli Kleemola

Virpi Kivioja (M.Soc.Sc. University of Turku) is a doctoral candidate of Contemporary History at the University of Turku. Her research interests include national stereotypes and country images, European history, and history of education.

References

- Ahern, L., D. S. Bortree, and A. N. Smith. 2012. “Key Trends in Environmental Advertising across 30 Years in National Geographic Magazine.” Public Understanding of Science 22 (4): 479–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662512444848.

- Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. revised ed. Londong: Verso.

- Andersson, J., and M. Hilson. 2009. “Images of Sweden and the Nordic Countries.” Scandinavian Journal of History 34 (3): 228–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03468750903134681.

- Ashby, C. 2010. “Nation Building and Design: Finnish Textiles and the Work of the Friends of Finnish Handicrafts.” Journal of Design History 23 (4): 351–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epq029.

- Askegaar, S., and G. Ger. 1998. “Product-national Images: Towards a Contextualized Approach.” European Advances in Consumer Research 3 (1): 50–58.

- Bannister, J., and J. A. Saunders. 1978. “UK Consumers’ Attitudes Towards Imports: The Measurement of National Stereotype Image.” European Journal of Marketing 12 (8): 562–570. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004982.

- Bauer, M. W., and G. Gaskell. 1999. “Towards a Paradigm for Research on Social Representations.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 29 (2): 163–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00096.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Clerc, L. 2016. “Variables for a History of Small States’ Imaging Practices – The Case of Finland’s ‘International Communication’ in the 1970s–1980s.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 12 (2–3): 110–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-016-0008-8.

- Collins, J., and C. Lutz. 1992. “Becoming America’s Lens on the World: National Geographic in the Twentieth Century.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 91 (1): 161–191.

- Golden, N. L. 1989. The United States and Finland: An Enduring Relationship 1919–1989. Helsinki: United Stated Information Service.

- Hakoköngäs, E., and I. Sakki. 2016. “Visualized Collective Memories: Social Representations of History in Images Found in Finnish History Textbooks.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 26 (6): 496–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2276.

- Hakoköngäs, E., O. Kleemola, I. Sakki, and V. Kivioja. 2020. “War in Images: Visual Narratives of Finnish Civil War in History Textbooks.” Memory Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698020959812.

- Hall, S. 1999. “Encoding/Decoding.” In Media Studies. A Reader, edited by P. Marris and S. Thornham. originally 1973, 51–61. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hamann, C. 2007. “Visual History und Geschichtsdidaktik Beiträge zur Bildkompetenz in der historisch-politischen Bildung”. Dissertation, Berlin: Technische Universität Berlin.

- Höijer, B. 2011. “Social Representations Theory: A New Theory for Media Research.” Nordicom Review 32 (2): 3–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0109.

- Ipatti, L. 2019. “At the Roots of the ‘Finland Boom’: The Implementation of Finnish Image Policy in Japan in the 1960s.” Scandinavian Journal of History 44 (1): 103–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2018.1502680.

- Jansson, D. R. 2003. “American National Identity and the Progress of the New South in National Geographic Magazine.” The Geographical Review 93 (3): 350–369. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2003.tb00037.x.

- Jokela, S. 2011. “Building a Façade for Finland: Helsingin in Tourism Imagery.” The Geographical Review 101 (1): 53–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2011.00072.x.

- Kivioja, V., O. Kleemola, and L. Clerc. 2015. “Johdanto: Suomi-kuvaa kautta aikojen.” In Sotapropagandasta brändäämiseen: Miten Suomi-kuvaa on rakennettu, edited by V. Kivioja, O. Kleemola, and L. Clerc, 13–27. Jyväskylä: Docendo.

- Knöferle, K. 2013. “Die Fotoreportage in Deutschland von 1925 bis 1935. Eine empirische Studie zur Geschichte der illustrierten Presse in der Periode der Durchsetzung des Fotojournalismus.”. Academic dissertation, Hitzhofen: University Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

- Kobré, K. 2004. Photojournalism: The Professionals’ Approach. Boston: Focal Press.

- Koski, A. 2005. “Niinkö on jos siltä näyttää? Kuva ja mielikuva Suomen valtaresursseina kansainvälisessä politiikassa”. Dissertation, Helsinki: Tutkijaliitto.

- Lähteenkorva, P., and J. Pekkarinen. 2008. Idän etuvartio? Suomi-kuva 1945–1981. Helsinki: WSOY.

- Lutz, C., and J. Collins. 1991. “The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes: The Example of National Geographic.” Visual Anthropology Review 7 (1): 134–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1991.7.1.134.

- Marklund, C., and K. Petersen. 2013. “Return to Sender – American Images of the Nordic Welfare States and Nordic Welfare State Branding.” European Journal of Scaninavian Studies 43 (2): 245–257.

- Martikainen, J. 2019. “Social Representations of Teachership Based on Cover Images of Finnish Teacher Magazine: A Visual Rhetoric Approach.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 7 (2): 890–912. doi:https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v7i2.1045.

- Mendelson, A. L., and F. Darling-Wolf. 2009. “Readers’ Interpretations of Visual and Verbal Narratives of a National Geographic Story on Saudi Arabia.” Journalism 10 (6): 798–818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884909344481.

- Moscovici, S. 1973. “Foreword.” In Health and Illness: A Social Psychological Analysis, edited by C. Herzlich, ix–xiv. London: Academic Press.

- Moscovici, S. 1984. “The Phenomenon of Social Representations.” In Social Representations, edited by S. Moscovici and R. Farr, 3–55. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Musiał, K. 2002. “Roots of the Scandinavian Model: Images of Progress in the Era of Modernisation”. Dissertation, Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- O’Barr, W. 1994. Culture and the Ad: Exploring Otherness in the World of Advertising. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Paasivirta, J. 1962. Suomen Kuva Yhdysvalloissa. Porvoo: WSOY.

- Parameswaran, R. 2002. “Local Culture in Global Media: Excavating Colonial and Material Discourses in National Geographic.” Communication Theory 12 (3): 287–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00271.x.

- Pérez-Marín, M. 2016. “Critical Discourse Analysis of Colombian Identities and Human nature in National Geographic Magazine (1903–1952).” Dissertation, New Mexico: University of New Mexi.

- Poole, R. 2004. Explorers House: National Geographic and the World It Made. New York: Penguin Press.

- Raento, P. 2006. “Communicating Geopolitics through Postage Stamps: The Case of Finland.” Geopolitics 11 (4): 601–629. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040600890750.

- Raento, P., and S. Brunn. 2008. “Picturing a Nation: Finland on Postage Stamps, 1917–2000.” National Identities 10 (1): 49–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14608940701819777.

- Raetzsch, C. 2015. “‘Real Pictures of Current Events’ the Photographic Legacy of Journalistic Objectivity.” Media History 21 (3): 294–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2015.1053387.

- Schulten, S. 2000. “The Making of the National Geographic: Science, Culture, and Expansionism.” American Studies 41 (1): 5–29.

- Suchoples, J. 2000. Finland and the United States: The Early Years of Mutual Relations. Helsinki: SKS.

- Vanhanen, H. 2015. “The Paradoxes of Quality Photographs: Slow Journalism in National Geographic.” In Integrated Media in Change, edited by R. Brusila, A.-K. Juntti-Henriksson, and H. Vanhanen, 87–106. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press.

- Wheelersburg, R. 2016. “National Geographic Magazine and the Eskimo Stereotype: A Photographic Analysis, 1949–1990.” Polar Geography 40 (1): 35–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1257659.

- Wimmer, A., and N. Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-state Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00043.

Table A1.

Analyzed articles in the National Geography Magazine 1905–2013 (N = 37). References from the electronic archive of the National Geographic Magazine

![Image 5. ‘Oulanka [Park] helps preserve this type of wetland, which is slowly being destroyed elsewhere in Scandinavia’. Photograph: Peter Essick (A29, 68–69).](/cms/asset/34c07916-b6d7-4d11-85f3-a25aed521a43/gcul_a_1916482_uf0005_oc.jpg)