ABSTRACT

Previous research has neglected media audiences’ and citizens’ opinions on how the media should be organized, how they should function in society and what individual, corporate and state responsibilities should be in regard to these questions. In an attempt to understand the relationship between citizens’ broader political attitudes and their attitudes on media-related politics and responsibilities, this study uses a survey (n = 2003) of the adult Swedish population to investigate the distribution of a range of media political attitudes in the contemporary space of political positions. The results reveal overlaps between the space of media political attitudes and the broader political space, where support for a Nordic ‘media welfare state’ corresponds to leftist and GAL-oriented values, while TAN-oriented and right-wing attitudes link to scepticism towards state interventionism in the media landscape. A small but highly opinionated right-wing and TAN-oriented segment displays laissez-faire views on media policy that are reflected in current policy propositions from right-wing political parties in parliament.

Introduction

Media policy has always been an arena in which conflicts between different political interests, ideas and ideologies have shaped the media societies that we inhabit (Freedman Citation2008). During the last decades, however, it would be safe to say that public debates on how the media are organized, regulated and operating have become more vivid and heated. To some extent, this might be due to the fact that we lead increasingly media-saturated lives (Hepp Citation2019). Rapid technological development, as well as democratic and economic challenges in the so-called ‘platform society’ (Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018), have raised new questions and brought new issues to the table of media policy debate. Of equal importance is the changing political climate in many parts of the world, which includes the rise of right-wing populist movements and radical right-wing and neo-fascist parties, for whom the traditional media have become a main target (Carlson Citation2018). The new right-wing rhetoric comes with a framing of the media – and of public service media and journalism in particular – as being allied with the ‘elites’ of society and standing in the way of the ‘people’ (Sehl, Simon, and Schroeder Citation2020; Holtz-Bacha Citation2021). There are thus reasons for the contention that media policy has been re-politicized, and that conflicts and debates on how to organize the media in society have become more intense. Ordinary citizens’ views on how the media should be organized and function, and on individual, corporate and state responsibilities regarding the media, can be broadly labelled as ‘media political attitudes’ and are referred to as such in this paper. Although this concept has recently attracted scholarly interest, media policy research has not fully understood the link between media political attitudes and people’s broader, non-media-related political attitudes. This study sets out to remedy this gap.

Even though public debate on media policy has become more intense in recent years, media policy largely remains an elite discourse in which experts, opinion leaders, politicians and lobbyists play the main roles. While media policy in Europe has changed rapidly – in a neoliberal direction since the 1980s (Jakobsson, Lindell and Stiernstedt Citation2021, Ala-Fossi Citation2020) and currently in a more authoritarian direction (Holtz-Bacha Citation2021; Sehl, Simon, and Schroeder Citation2020; Surowiec and Štětka Citation2020) – change has mainly been orchestrated from ‘above’ or from external stakeholders in international flows of policy transfer (Freedman Citation2003; Sarikakis and Ganter Citation2014), rather than being the result of public political debates or popular demands (Freedman Citation2010; Ward Citation2002). At best, the extent to which media policy shifts are the outcome of democratic processes and popular demand remains unclear. In this context, research has an important role to play in the public debate by highlighting citizens’ ‘normative and value-based expectations concerning media performance’ (Hasebrink Citation2011, 334). To date, this task has not been taken up by media scholars, which implies that we have little understanding of the extent to which people support overarching media policy paradigms (Van Cuilenburg and McQuail Citation2003) and how that support (or lack of support) relates to people’s political attitudes. As argued by Flew (Citation1998, 324), media policy processes have often been a ‘translation of normative principles to processes of technical calculation and of routine administration’. Obtaining a better understanding of popular support for various forms of media organization and of how this support connects to ideological sentiments and political orientations is hence a way for policy research to help to reconnect the issues of media policy to a political sphere, in which such questions belong, and to increase opportunities for public participation in policy formation (Hasebrink Citation2011).

It is against this backdrop that we in this article analyse media policy attitudes in the Swedish population and understand them in relation to general political attitudes. The aim is hence to clarify how the specific subset of media policy issues is related to the overall attitudinal structure among the citizens.

We take as our case Sweden – a Nordic ‘media welfare state’ (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014) known for well-funded public service media, extensive media subsidies, a consensus-oriented media market and high levels of media access, use and trust. In what follows, we probe citizens’ views on various functions, institutions and responsibilities connected to the Swedish/Nordic media model. Previous research (Lindell, Jakobsson and Stiernstedt Citation2022) has identified strong citizen support for a welfare-oriented media policy and identified significant gaps between neoliberal media policy measures taken in the political field over the last 30 years on the one hand, and citizens’ views on how the media should be organized on the other (ibid.). While welfare-oriented media policy has been shown to be supported by a majority of Swedish citizens, disagreements exist between citizens with different political views. In this article, our aim is to analyse further the relationship between citizens’ ideological differences and their attitudes towards media politics.

The research question that we set out to answer with the help of a web based survey of Swedish citizens (n = 2003) is: what is the relationship between citizens’ political and ideological orientations, conceptualized here as a multidimensional space of political attitudes, and their attitudes on media politics? This study is relevant particularly because of (1) the technical and administrative character of media policy, which makes the connection to political ideologies and party preferences uncertain; (2) the hidden nature of media policymaking, which has resulted in questions on media policy often having been absent from public debate (Freedman Citation2010); (3) the recent politicization of media policy, which appears to have moved questions on media policy onto the political agenda; and (4) the fact that such research can assist in facilitating a stronger link between citizens’ opinions and policymaking.

Political attitudes and attitudes towards the media

Media policy scholars have generally not prioritized attitudes among citizens as an area of research. As argued above, however, we find that media research has an important role to play in analysing and highlighting citizens’ ideas, wishes and attitudes in regards to media policy and thereby creating a link between citizens and the policy field. Verboord and Nørgaard Kristensen (Citation2021) present a recent exception to this rule – albeit one that concerns cultural policy more broadly – in their work on ‘cultural value orientations’ in relation to EU cultural policy and different media systems in Europe.

Comparative media systems researchers have included citizens in their research to some extent, but this has mainly been done by conceptualizing citizens as media audiences. Research interest within this field has thus been directed towards differences in media use in and between different countries – for instance, in terms of levels of news consumption (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004; Syvertsen et al. Citation2014). The media user as a political subject and her role as a citizen and participant in processes of media governance have thereby been side-lined.

There is some research on popular movements for media reform (e.g. Pickard Citation2014; Segura and Waisbord Citation2016), as well as research on forms of media activism (e.g. Freedman Citation2019; Milan Citation2017); however, such practices only include very small fractions of the general population. The question of the broader citizenry and their attitudes on how to organize the media in society and what the functions and responsibilities of the media are, as well as the relation between such attitudes and general political sentiments, have been overlooked. Consequently, there is little previous research to build on in this study. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to believe that general differences in political attitudes, such as an acceptance of state interventions versus more laissez-faire contentions, play into citizens’ views on media political issues. In order to contextualize this study, we rely on research on the connection between political attitudes, ideologies and party preferences on the one hand, and media preferences, media use, perceptions of the media and media trust on the other. Here, research has consistently shown that the political orientation of citizens affects how they view the media. This body of research provides clues on how the political orientation of citizens might overlap with their attitudes on media policy.

Firstly, an important part of the Nordic media model – the media system taken as our case – is its strong public service institutions, which are upheld by generous funding, institutionalized autonomy from the state and a broad mission provided in the broadcasting license. Even though the last 30 years have seen an increasing marketization of broadcasting in the Nordic countries (e.g. Sjøvaag Citation2012), previous research has suggested that there is a relative consensus around this policy design, at least among the elites, and that ‘diverging political perspectives on public service media should not be exaggerated as they have so far more focused on principles than on practices’ (Arriaza Ibarra and Nord Citation2014, 82). In a study from the Netherlands, which has a similar media system and political system to that of Sweden, Bos et al. (Citation2016) found that public service media act as a bridge between different segments of the media audience and that people consume public service media regardless of political affiliation. In a similar vein, Dahlgren (Citation2019) found that both the political left and the political right in Sweden turn to public service media and that this has not changed during the years from 1986 to 2015, despite an increased availability of commercial alternatives in the Swedish media market. Rather than left-wing or right-wing viewpoints, substituting public service media with other media outlets can be explained by political disinterest and an attraction to political parties outside parliament (Dahlgren Citation2019).

Consequently, it seems reasonable to expect that policy attitudes towards public service media institutions in Sweden should be more or less positive across the political spectrum. However, previous research has also revealed differences in the use of and trust in public service media among Swedish citizens (Bergström and Wadbring Citation2012; Jakobsson, Lindell and Stiernstedt Citation2021) that can be explained by age, generation and political orientations. Historically in Sweden, there has been a divide between left-wing and right-wing parties in their relation to public service media, with the former generally having a more positive opinion to a ‘broad’ public service media (Arriaza Ibarra and Nord Citation2014). In recent years, the polarization between right-wing and left-wing parties on the issue of public service media has intensified, with proposals on re-fashioning and defunding the public service media coming from the political right (Jakobsson, Lindell and Stiernstedt Citation2021). If this intensification is reflected in the popular attitudes of right-wing voters, we should expect to find a polarized view on public service media within the citizenry.

Secondly, a key dimension of Nordic media policy concerns the broader role of the press and journalism. The Nordic countries are not only characterized by a high degree of press freedom (Press Freedom Index Citation2021), but also by a relatively high news readership among all strata of the population, even though such readership is decreasing, especially among younger people who tend to turn to social media for news (Bergström and Jervelycke Belfrage Citation2018). The Nordic press has a strong tradition of self-regulation (i.e. ethical codes and an ombudsman) and has been supported by the state through uniquely generous direct subsidies, which have increased in recent years (Nord and von Krogh Citation2021). Do previous studies provide any clues on whether this policy framework is an area of political conflict? For one thing, previous research has shown that people with populist attitudes tend to prefer ‘tabloid’ media over ‘quality’ media (Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017). Since the tabloid press is more often accused of transgressing the ethical boundaries of the press (Biressi and Nunn Citation2008), this leads us to expect that people who support the Swedish right-wing populist party might be more negatively attuned to the notion that media companies should be obliged to take social responsibility and to press ethics and other forms of self-regulatory frameworks for media publishing. This expectation is also supported by the fact that the most visible ‘alternative’ media actors in the Nordic countries, which operate outside of the established system of professional journalism, are mainly right-wing populist media outlets.

In the last few years, press subsidies in Sweden have been transformed into platform-neutral media subsidies; they have also increased. However, there has not been much public debate on this issue, and no research has been conducted on whether there is popular support for this policy measure. Since the subsidies mainly go to established and traditional news outlets, it might be expected that people who do not consume news (or are hostile towards mainstream news) would be less in favour of media subsidies. This assumption relates to findings on political selective exposure, which indicate that people with extreme political views are more likely than others to turn to partisan news outlets that support their political preferences and to avoid content that contradicts their political position (Rodriguez et al. Citation2017). Previous research also indicates that distrusting traditional media outlets and political selective exposure is more common among people on the right-wing side of the political spectrum (ibid.). The consumption of alternative news sites operating outside of the political support systems for news and journalism should thus be more prevalent among people who agree with conservative or right-wing ideologies. This expectation is supported by the fact that most of the high-profile alternative news outlets in the Nordic countries brand themselves as right-wing outlets (Ihlebæk and Nygaard Citation2021) and that the consumers of these media are more critical towards traditional media (especially public service media) and more sceptical of news quality in general (Schulze Citation2020). These segments of the citizenry display what Holt (Citation2018) refers to as a general ‘anti-systemness’. It can thus be expected that people with (extreme) right-wing views are less positive towards media regulations that support news and journalism in various ways.

Thirdly, much current debate on media policy has concerned ‘platformization’, which refers to the rise of large tech companies and their role in the Swedish media landscape, along with the related issues of personal integrity, safeguarding of personal information and control over personal data. Another issue concerns freedom of speech and the occurrence of hate speech and defamation on these platforms, which has pushed the issue of media education and media and information literacy to the forefront. These are issues in which the state can play a key role through the educational system. Wagner (Citation2019, 87) argues, however, that media and information literacy does ‘not have a central foundation in Swedish politics, nor is there an overall political framework for such matters’. There is no previous research on how such policy issues have been interpreted and embraced (or not) by the public; however, considering the absence of media and information literacy questions in the Swedish political system, a low political polarization regarding this issue might be expected. Cocq et al. (Citation2020) showed that Swedes are generally aware and critical of online surveillance, as they tend to value their online privacy and integrity. However, rather than seeking technical or political solutions to this problem, they tend to handle online surveillance by adapting their individual behaviour. Therefore, a low level of political polarization on the issue of the importance of control over data might be expected.

The debate on hate speech and freedom of expression on digital platforms is arguably a more polarized discussion, in which suggestions for regulation have been manifold (e.g. Banks Citation2010). The fact that this discussion taps in to the broader political issues of interventionism versus laissez-faire, which have a long history in the area of freedom of expression (Peters Citation2005), makes it reasonable to expect that political attitudes will be a predictor for where an individual stands on both the regulation of content on digital platforms and the support for media education and media literacy programmes. Furthermore, the fact that parties and groups belonging to the radical right have been shown to be active in creating and spreading hate speech and using social media and digital platforms for distributing such content, as well as in attacking political opponents (Edström Citation2016; Pettersson Citation2020; Wahlström, Törnberg, and Ekbrand Citation2021), suggests that a far-right political affiliation might affect an individual’s standpoint on this media political issue.

The space of political attitudes

In this study, our interest lies in mapping the relationship between citizens’ political attitudes and their attitudes to media policy. Political attitudes can be approached in many different ways. Following Harrits et al. (Citation2010), we conceptualize citizens’ political attitudes in an open-ended and empirical way as a multidimensional space of position-takings. The ‘materialist’ or ‘economic’ left-right dimension has dominated political analysis for a long time and is arguably still the most important political dividing line in today’s politics. However, in order to nuance contemporary political dividing lines, political scientists have added the so-called post-materialist or GAL (green, alternative, libertarian)/TAN (traditionalist, authoritarian, nationalist) dimension (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002). Political disputes along this dimension revolve around ‘questions relating to the environment and climate change, (nuclear) war, rights for homosexuals, racism and xenophobia’ (Flemmen Citation2014, 545). It can be questioned, however, whether ‘post-materialism’ is a good label for these issues, given that all have a clear economic dimension – such as the intersection of race and class, the uneven economic consequences of climate change and how migration is believed to impact the economy (Evans and Tilley Citation2017). Nevertheless, the two-dimensional approach used in many contemporary analyses has been shown to be useful to study overlaps, or homologies, between, for instance, social class positions and political attitudes (Harrits et al. Citation2010; Enelo Citation2012; Harrits Citation2013; Flemmen and Haakestad Citation2018).

As mentioned above, previous research shows that the right-/left-wing dimension influences how people consume and relate to the media. It is thus reasonable to expect that such ideological oppositions affect people’s attitudes towards media policy issues. The inclusion of post-material attitudes (e.g. GAL/TAN values), however, is not particularly common in media studies. Considering that media policy is a form of cultural policy (as well as economic policy), and since previous research has revealed connections between GAL-TAN orientations and support for welfare-oriented media politics – with people holding GAL-views being more positively attuned (Lindell, J., P. Jakobsson, and F. Stiernstedt Citation2022) – it is necessary to include the post-material dimension in the present analysis.

The drawback of the ‘material’ and ‘post-material’ approach to contemporary ideological conflicts is that it does not fully capture the rise of right-wing populism. Populism is often described as a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013), as it is defined with just a few key characteristics and does not hold a fixed place along the two dimensions of the political spectrum described above. Still, as previously discussed, populist attitudes seem to correlate with attitudes towards news and journalism. It is thus relevant to include populist and non-populist orientations in an analysis. One way to address this issue is to include party preferences in the analysis. The current Swedish parliament hosts one party – the Swedish democrats (with 17.5 percent of the votes in the 2018 general election) – that shares some characteristics with European right-wing populist parties (Hellström and Kiiskinen Citation2013). Moreover, including current party preference in the analysis provides additional details to the overall analysis, since ideological opinions do not always overlap with party preferences (Dahlgren Citation2019).

Data and method

The aim of this study was to study the relationship between citizens’ media political attitudes – that is, their views on how the media should be organized, how they should function, and the responsibilities held by individuals, corporations and the state with regard to these questions – on the one hand, and peoples’ general political attitudes on the other hand. This endeavour required fairly specific data, not only on people’s standpoints on various media policy measures, but also on their political opinions. To obtain the necessary data, we developed a web-based survey that was administered by the research institute Kantar-Sifo. The survey was distributed to 10,395 Swedes between the ages of 18 and 99 in November 2020. We received 2003 responses, for an answering rate of 19.3 percent. While the survey captured well citizens of different ages (M = 49, SD = 18) and genders (men/women = 50/50 percent) it did not adequately represent people with no or very low educational qualifications, which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

Our first step was to delineate the structure of the Swedish space of political attitudes. In following previous studies on the space of political attitudes (e.g. Harrits et al. Citation2010; Enelo Citation2012; Harrits Citation2013; Flemmen and Haakestad Citation2018), and in order to plot media political attitudes in the space of political attitudes, to visualize the results, and to avoid assumptions on linearity in the model, we relied on multiple correspondence analysis (MCA).

To construct a statistical representation of the contemporary Swedish space of political attitudes 16 measurements of various political standpoints, including both traditional left-wing versus right-wing attitudes (eight variables) and post-material (GAL/TAN) attitudes (eight variables), were used. While the process of operationalization drew inspiration from previous attempts to study the space of political attitudes (e.g. Harrits et al. Citation2010; Harrits Citation2013; Flemmen and Haakestad Citation2018; Lindell and Ibrahim Citation2021), it also included specific items related to the political landscape in Sweden (e.g. attitudes on the Employment Protection Act [LAS] and tax subsidies on household services and renovations [ROT/RUT]). lists the active variables that were used in MCA to construct a statistical representation of the Swedish space of political attitudes by extracting and visualizing the principal factors, or dimensions, among the 16 variables. The variable ‘political party preference’ was used as a supplementary variable to study where prospective voters according to their political attitudes were positioned in the political space. In order to avoid a skewed model, variables were recorded so that no individual value held less than 5 percent of the observations (Hjellbrekke Citation2018).

Table 1. Active variables creating the space of political attitudes in Sweden.

To study citizens’ opinions on how the media should be organized, how they should function, and the responsibilities of individuals, corporations and the state with regard to these questions, we probed peoples’ attitudes on various functions and institutions connected to the media system they inhabit – that is, the Swedish, or Nordic, media system (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014). Among these 16 variables were statements saying, for instance, that communication services should be organized in a way that ensures their character as ‘public assets’, that extensive subsidies exist and that requirements should be set for universal access (e.g. broadband expansion, public service media). Other statements captured whether or not the respondents agreed that regulation should exist to ensure the freedom of the press, editorial freedom and professional autonomy in the media industry and in the journalist corps. shows the supplementary variables and their distribution. In the subsequent analyses, these variables were recoded so that no value held less than 5 percent of the observations.

Table 2. Citizen’s media policy attitudes (percentages).

We were only concerned with respondents who displayed their political standpoints. In the following analyses, all ‘I don’t have an opinion’ answers in the active variables were coded as missing.

Results and analysis

In order to study the relationship between attitudes on how the media should be organized and function in society and the wider space of political attitudes, we began by constructing a statistical representation of the contemporary Swedish space of political attitudes. We then plotted our 16 variables measuring media political attitudes in the space of political attitudes as supplementary, passive variables.

The space of political attitudes

shows a statistical representation of the contemporary Swedish space of political attitudes. More specifically, it displays the result of an exploratory statistical method (i.e. MCA) that extracted dimensions from the 16 variables used to measure the respondents’ political attitudes. The first dimension (explaining 64.9 percent of the variance) and second dimension (explaining 14.5 percent) account for a total of 79.4 percent of the variance; we have chosen to focus only on these two main dimensions (see ).

Figure 1. The Swedish space of political attitudes. MCA, axis 1 and 2. Missing values (including “I don’t have an opinion”) have been removed (n = 874). - - = “I don’t agree at all”, - = “I don’t agree”, + = “I agree”, + + = “I fully agree”.

The first dimension (horizontal axis in ) captures differences (in the form of distances in the space) between left-wing and right-wing views, as well as between GAL and TAN views (see for the active variable contribution to dimensions 1 and 2). To the right in are individuals who favour both right-wing and TAN-oriented policy. Individuals located towards this pole in the space tend to prefer economic liberalism (e.g. reducing taxes, creating a more flexible labour market and keeping a commodified welfare system) over material redistribution. At the same time, they favour social conservatism or TAN values (e.g. opposing the legalization of homosexual marriages, wanting a stricter migration policy and opposing the allocation of energy and resources into creating more equality between genders) over GAL values. In opposition, to the left in the space are individuals with left-wing and GAL-oriented attitudes.

The second (vertical) dimension differentiates individuals according to the intensity of their political views. Individuals located at the top of the space tend to strongly agree or disagree with the policy statements provided. In contrast, the majority of the respondents, which are positioned in the bottom half of the space, hold more modest political views.

These results are in agreement with previous studies on the space of political attitudes in that we identify an ‘intensity of opinion’ dimension (e.g. Flemmen and Haakestad Citation2018; Harrits Citation2013; Harrits et al. Citation2010; Lindell and Ibrahim Citation2021). The results, however, go against the body of previous research arguing that the GAL/TAN and left-wing versus right-wing dimensions make up two separated realms of contemporary politics (e.g. Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002). While separating the GAL/TAN dimension from the left-wing versus right-wing dimension makes conceptual sense and might reflect the policy profiles of political parties quite well (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002), our analysis aligns with those of Evans and Tilley (Citation2017) and Lindell and Ibrahim (Citation2021) in that attitudes connected to ‘material’ matters and redistribution (left-wing versus right-wing) and ‘post-material’ values (e.g. GAL or TAN orientations) seem to be highly interlinked, at least in terms of the attitudinal constellations of ordinary citizens.

Projecting the variable measuring respondents’ current favourite party preference as a supplementary, passive variable reveals that the Left Party is preferred by people located towards the top left in the space – that is, where people with intense GAL/leftist views are located. In contrast, the Sweden Democrats are the preferred party for individuals in the middle of the top-right quadrant of the space, where relatively intense TAN/right-wing attitudes prevail. Citizens that favour the Centre Party and the Liberals are found in the middle on the horizontal (GAL/left vs. TAN/right) axis and 0.5 deviations south of the centre on the vertical axis – a finding that implies that people who prefer these parties do not hold intense opinions on the policy issues probed here. People favouring the Social Democrats and the Green Party are unsurprisingly drawn to the left-wing/GAL pole, but they do not hold as intense views as the Left Party voters. Finally, respondents preferring either the Moderate Party (conservative) or the Christian Democrats are found towards the TAN/right-wing pole in the space, but they do not display as intense opinions as the Sweden Democrats.

This initial step, which yielded a statistical representation of the space of ideological conflicts between contemporary Swedish citizens, provides the basis for understanding the relationship between political ideology and polarization and views on how the media should be organized and function in society.

Media political attitudes in the space of political attitudes

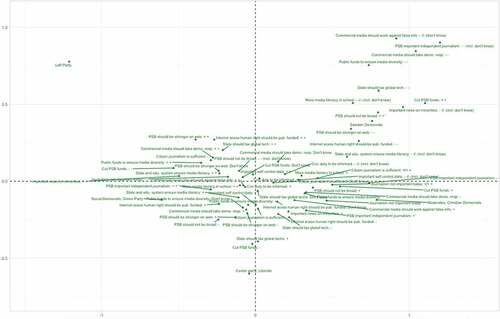

retains the structure explored above, in which the contemporary space of political attitudes in Sweden seems to be structured around two main principles of division: an opposition between GAL/left-wing views on the one hand and TAN/right-wing views on the other hand (horizontal axis), and a differentiation between those with ‘intense’ views on political matters and those with less animated views (vertical axis). In this figure, the active variables have been made invisible; instead, shows the distribution of our supplementary variables: the respondents’ media political attitudes. As a first observation, it is noticeable that many variable categories are located relatively far (>.4 deviations) from the centre of the space, which suggests that oppositions in political orientations explain differences in views on how to organize the media rather well. In most cases, the relationships between attitudes on how to organize the media in society and views on responsibility in media politics and the axes described above are statistically significant (). However, a couple of media political attitudes tend to be distributed very close to the centre of the space, meaning that variations in these variables are not well explained by peoples’ political views and the intensity of those views. These media political attitudes include the view that citizens have a duty to keep up to date with current affairs and that it is important to have control over personal data collected on social media. As discussed above, the latter result was expected, due to the fact that Swedish citizens regard online privacy issues as an individual responsibility rather than a political one. The notion that citizens have a civic duty to keep up with news and current affairs is shared by virtually all citizens (Lindell 2018), and is thus not a politically divisive opinion.

Figure 2. Projecting media policy attitudes into the Swedish space of political attitudes. MCA, axis 1 and 2. Missing values (including “I don’t have an opinion”) have been removed (n = 874). - - = “I don’t agree at all”, - = “I don’t agree”, + = “I agree”, + + = “I fully agree”.

In regard to most of the variables measuring citizens’ attitudes on media politics, there are clear political divisions within the citizenry. The role, function and funding of public service media is one of the most divisive issues, where individuals drawn to the top-right corner of the space (right-wing/TAN attitudes) are of the opinion that the public service media should be defunded, that these organizations should not expand their activities in the digital realm and that being part of public service media is not a guarantee of independent journalism. This result only partly aligns with what we had expected based on previous research on how audiences value the public service media. Studies have shown that there are differences in whether media audiences trust public service media or not that are dependent on political ideology (Bergström and Wadbring Citation2012); however, previous studies also suggest that public service media in the Nordic countries (Dahlgren Citation2019) and in other democratic-corporativist countries (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004) function as a bridge between people with widely differing political views among the audience (Arriaza Ibarra and Nord Citation2014). Judging from our results, it seems that the increased politization and polarization of the public service media has begun to be reflected in the attitudes of citizens. The differences within the citizenry analysed here, in contrast to the results of Arriaza Ibarra and Nord (Citation2014), are not only a matter of consumption habits but of principles, since they involve attitudes on the defunding of the public service media and the belief that being a part of the public service media does not guarantee independent journalism. Furthermore, this stand against public service media is associated with preferring the right-wing populist party (i.e. the Sweden Democrats) in Sweden, as shown in . To some extent, this is an expected result, since the Sweden Democrats are the political party with the most outspoken and aggressive rhetoric towards the public service media in their communications and in the policy suggestions they have put forward, both in parliament and in the public debate (Bengtsson Citation2021).

Overall, the segment of the population holding relatively intense TAN and right-wing views, which overlaps with the segment voting for a right-wing populist party, holds a more laissez-faire view on how to organize the media, with resentment towards state intervention in the media market. These segments of the population do not support the system of press subsidies and oppose a publicly funded strategy for broadband expansion. This lack of support for press subsidies was expected, based on the observation that right-wing attitudes are associated with a distrust of the mainstream news media (Schulze Citation2020) and on the establishment of right-wing populist alternative media outlets, some of which are not included in the Swedish system for press subsidies. We found no previous research on the support of media policy measures for Internet and broadband access; however, the results show that such support is distributed in the same way as support for press subsidies. The economic liberal standpoint is also reflected in the opposition to the taxation of global tech companies. Even though this segment has attitudes that can be interpreted as nationalistic – pro-military, against the EU and with migration scepticism – the economic liberalist position held by these individuals seems to override their national interest in curbing the power of the global tech giants, most of which are based in the United States or China.

The same segment of the population (right-wing, TAN-oriented) has strong views against the responsibility of the commercial media to act against false information. This finding aligns with the laissez-faire sentiments explored above. However, the survey question did not mention regulation by law but referred to moral obligations, so a negative response is compatible with a libertarian political standpoint. The response to this question that stands out in might therefore primarily link to how the issue of ‘fake news’ and ‘misinformation’ has become politicized and discursively configured in the contemporary moment. While the notion of ‘fake news’ has been appropriated by right-wing populist leaders (Farkas and Schou Citation2018), the fight against ‘misinformation’ is culturally coded as an elite project and as having alleged attempts to produce news that is in line with current ideas about ‘political correctness’. It is clear, for example, that negative opinions about the EU cluster together with strong opinions against the need for the media to take democratic responsibility and combat false information. The EU has been outspoken about its intention to combat disinformation (Kuczerawy and Kloza Citation2019), which might explain why these opinions are found close together. A similar line of reasoning might explain the opposition towards the inclusion of media literacy as a responsibility of the state and the education system. Media literacy, it might be speculated, is in some people’s view associated with a state-sanctioned ‘correct’ way of critiquing and interpreting media content, rather than being perceived as a politically neutral skill of processing information.

Taken together, these findings suggest that there are clear overlaps between the space of political attitudes and the space of media political attitudes. People holding GAL and leftist views have a more positive attitude towards the values, functions and institutions connected to the Nordic media model, whereas individuals with TAN and right-wing views have a more negative attitude. In addition, intense political views reflect intense media political views.

Conclusions and discussion

Media policy is sometimes seen as a technical, administrative affair (Freedman Citation2008). As such, there is a risk of it becoming disconnected from public debates and decided upon by experts, lobbyists and politicians, who are not held accountable for their decisions. Media research has a role to play here, by highlighting citizens’ views on crucial issues within media policy debates (Hasebrink Citation2011). This is one of the contributions of this study: connecting citizens’ attitudes on media political issues to their political ideologies and standpoints, and identifying clear affinities between the two realms. Although Sweden was used as the empirical case in this article, we hope that our open-ended approach in studying the relationship between ordinary citizens’ political standpoints and their views on how to organize the media can be used and developed in other contexts as well, not least in other media systems. Given the relatively low response rate on our survey, and the fact that people with no or very low educational qualifications were underrepresented we also encourage more studies in Sweden.

One conclusion that can be drawn from this analysis is that attitudes among Swedish citizens on how the media should be organized, how they should function, and the responsibilities of individuals, corporations and the state with regard to these questions tend to cluster together in the middle of the political space, as we conceived of it here. In the discussion of the results above, we mainly focused on the sentiments regarding media policies that were clearly connected to ideological polarization; however, the results also show that the disagreements on media policy are somewhat limited. Indeed, most Swedes have positive responses towards the values, functions and institutions that are connected to the Nordic way of organizing media in society (Lindell, Jakobsson and Stiernstedt Citation2022). Nevertheless, the differences that we have uncovered shows an overlap between media policy attitudes and general political attitudes, including both the material left- and right-wing dimension and the ‘post-material’ GAL-TAN dimension. We thus nuance previous research that has primarily focused on differences along left-wing versus right-wing oppositions.

A key finding of this study is that one particular segment of the citizenry is positioned outside of the central cluster, far away from the mainstream political and media political consensus. This is a highly opinionated segment with strong views against immigration, the EU, taxes on fossil fuels and same-sex marriages – that is, questions associated with the TAN position in the political space. This segment also contains those who express sympathy for the Swedish right-wing populist party. This part of the citizenry is highly sceptical of the media policy regime connected to the Nordic media model (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014). At the same time, this relatively small minority of the Swedish population displays media policy attitudes that are aligned with how the mainstream and public service media has been criticized by right-wing populist parties across Europe (Holtz-Bacha Citation2021). This finding also supports the observation of clear overlaps between citizens’ media political attitudes and their political attitudes.

These results relate to the wider field of media policy debates. The limited disagreements on media policy and the fact that most citizens are supportive of the general features of the Nordic media system create a ‘silent majority’ in media policy issues. When media policy is discussed in the public realm, the more ‘extreme’ or critical positions generally get the most attention (cf. Nord Citation2020); examples include the idea from the conservative party (Moderaterna) to close public service broadcasting all together (Folkö Citation2019), or the parliamentary motions from the right-wing parties to, for example, cut press subsidies, defund or refashion the public service broadcasters and increase political control over public service media (Bengtsson Citation2021). Also ideas from the left, such as harder regulations on platform companies or a ‘public service internet’ (JonassonCitation2015) represent such ideas, which as we have seen find little support in the attitudes held by the vast majority of the population.

The mis-match between citizens’ views on media policy and the policy debate and suggestions that is put forward in the public debate is most clearly pronounced for a large group of right-wing voters who hold relatively moderate views on media policy and therefore find themselves without political representation in large parts of the current media policy debates. Furthermore, the current, more general, policy discussion on the road ahead for the Swedish media system seems to be strangely disconnected from the standpoints and media policy ideals held by the great majority of the population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter Jakobsson

Peter Jakobsson is an Associate Professor in the Department of Informatics and Media, Uppsala University, Sweden.

Johan Lindell

Johan Lindell is an Associate Professor in the Department of Informatics and Media, Uppsala University.

Fredrik Stiernstedt

Fredrik Stiernstedt is an Associate Professor in the Department of Culture and Education, Södertörn University, Sweden.

References

- Ala-Fossi, M. 2020. “Finland: Media Welfare State in the Digital Era?” Journal of Digital Media & Policy 11 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1386/jdmp_00020_1.

- Arriaza Ibarra, K., and L. W. Nord. 2014. “Public Service Media Under Pressure: Comparing Government Policies in Spain and Sweden 2006–2012.” Javnost-The Public 21 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1080/13183222.2014.11009140.

- Banks, J. 2010. “Regulating Hate Speech Online.” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 24 (3): 233–239. doi:10.1080/13600869.2010.522323.

- Bengtsson, J. 2021. Högerfront mot public service. Vad vill de tre högerpartierna med SVT, SR och UR? [Right-Wing Front Against Public Service. What Do the Three Right-Wing Parties Want with SVT, SR andUR?]. Stockholm: Tiden.

- Bergström, A., and I. Wadbring. 2012. “Strong Support for News Media: Attitudes Towards News on Old and New Platforms.” Media International Australia 144 (1): 118–126. doi:10.1177/1329878X1214400116.

- Bergström, A., and M. Jervelycke Belfrage. 2018. “News in Social Media.” Digital Journalism 6 (5): 583–598. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1423625.

- Biressi, A., and H. Nunn, eds. 2008. The Tabloid Culture Reader. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Bos, L., S. Kruikemeier, C. de Vreese, and D. R. Chialvo. 2016. “Nation Binding: How Public Service Broadcasting Mitigates Political Selective Exposure.” PLoS ONE 11 (5): e0155112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155112.

- Carlson, M. 2018. “The Information Politics of Journalism in a Post-Truth Age.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1879–1888. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1494513.

- Cocq, C., S. Gelfgren, L. Samuelsson, and J. Enbom. 2020. “Online Surveillance in a Swedish Context: Between Acceptance and Resistance.” Nordicom Review 41 (2): 179–193. doi:10.2478/nor-2020-0022.

- Dahlgren, P. M. 2019. “Selective Exposure to Public Service News Over Thirty Years: The Role of Ideological Leaning, Party Support, and Political Interest.” The International Journal of Press/politics 24 (3): 293–314. doi:10.1177/1940161219836223.

- Edström, M. 2016. “The Trolls Disappear in the Light: Swedish Experiences of Mediated Sexualised Hate Speech in the Aftermath of Behring Breivik.” International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 5 (2): 96. doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i2.314.

- Enelo, J. -M. 2012. “Klass, åsikt och partisympati: Det svenska konsumtionsfältet för politiska åsikter [Class, opinion and party preference: The Swedish field of consumption of political opinions].” PhD diss., Örebro University.

- Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2017. The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Farkas, J., and J. Schou. 2018. “Fake News as a Floating Signifier: Hegemony, Antagonism and the Politics of Falsehood.” Javnost – The Public 25 (3): 298–314. doi:10.1080/13183222.2018.1463047.

- Flemmen, M. 2014. “The Politics of the Service Class: The Homology Between Positions and Position-Takings.” European Societies 16 (4): 543–569. doi:10.1080/14616696.2013.817597.

- Flemmen, M., and H. Haakestad. 2018. “Class and Politics in Twenty-First Century Norway: A Homology Between Positions and Position-Taking.” European Societies 20 (3): 401–423. doi:10.1080/14616696.2017.1371318.

- Flew, T. 1998. “Government, Citizenship and Cultural Policy: Expertise and Participation in Australian Media Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 4 (2): 311–327. doi:10.1080/10286639809358078.

- Folkö, R. 2019. “M-distriktets beslut: Vill skrota public service [The Decision of the Conservative Party in Stockholm: Want’s to Shut Down Public Service].” Svenska Dagbladet, May 11. https://www.svd.se/m-i-stockholm-vill-skrota-public-service

- Freedman, D. 2003. “Cultural Policy‐making in the Free Trade Era: An Evaluation of the Impact of Current World Trade Organisation Negotiations on Audio‐visual Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 9 (3): 285–298. doi:10.1080/1028663032000161704.

- Freedman, D. 2008. The Politics of Media Policy. Cambridge: Polity.

- Freedman, D. 2010. “Media Policy Silences: The Hidden Face of Communications Decision Making.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (3): 344–361. doi:10.1177/1940161210368292.

- Freedman, D. 2019. ”Media Policy Activism.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Methods for Media Policy Research, edited by H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders, and L. Van Audenhove. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi-org.ezproxy.its.uu.se/10.1007/978-3-030-16065-4_36

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hameleers, M., L. Bos, and C. de Vreese. 2017. “The Appeal of Media Populism: The Media Preferences of Citizens with Populist Attitudes.” Mass Communication and Society 20: 481–504. doi:10.1080/15205436.2017.1291817.

- Harrits, G., A. Prieur, L. Rosenlund, and J. Skjott-Larsen. 2010. ”Class and Politics in Denmark: Are Both Old and New Politics Structured by Class?” Scandinavian Political Studies 33 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2008.00232.x.

- Harrits, G. 2013. “Class, Culture and Politics: On the Relevance of a Bourdieusian Concept of Class in Political Sociology.” The Sociological Review 61: 172–202. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12009.

- Hasebrink, U. 2011. “Giving the Audience a Voice: The Role of Research in Making Media Regulation More Responsive to the Needs of the Audience.” Journal of Information Policy 1: 321–336. doi:10.5325/jinfopoli.1.2011.0321.

- Hellström, A., and J. Kiiskinen. 2013. ”Populismens dubbla ansikte [The Two Faces of Populism].” In IMER idag: aktuella perspektiv på internationell migration och etniska relationer [IMER Today: Contemporary Perspectives on International Migration and Ethnic Relations], edited by B. Petersson and C. Johansson, 186–214. Stockholm: Liber.

- Hepp, A. 2019. Deep Mediatization. London: Routledge.

- Hjellbrekke, J. 2018. Multiple Correspondence Analysis for the Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Holt, K. 2018. “Alternative Media and the Notion of Anti-Systemness: Towards an Analytical Framework.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 49–57. doi:10.17645/mac.v6i4.1467.

- Holtz-Bacha, C. 2021. “The Kiss of Death. Public Service Media Under Right-Wing Populist Attack.” European Journal of Communication 36 (3): 221–237. doi:10.1177/0267323121991334.

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, and C. J. Wilson. 2002. “Does Left/right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?” Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 965–989. doi:10.1177/001041402236310.

- Ihlebæk, K., and S. Nygaard. 2021. “Right-Wing Alternative Media in the Scandinavian Political Communication Landscape.” In Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries, edited by E. Skogerbø, Ø. Ihlen, N. N. Kristensen, and L. Nord, 263–282. Gothenburg: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg.

- Jakobsson, P., J. Lindell, and F. Stiernstedt. (2021). A Neoliberal Media Welfare State? the Swedish Media System in Transformation. Javnost - the Public, 28 (4), 375–390. doi:10.1080/13183222.2021.1969506.

- Jonasson, M. 2015. “Behövs Public Service På Internet? [Is Public Service Needed on the Internet?].” Internetstiftelsen. Accessed 2022 06 16. https://internetstiftelsen.se/nyhetsartiklar-fran-internetstiftelsen/arkiv-med-blogginlagg-fran-den-fore-detta-iis-bloggen/behovs-public-service-pa-internet/.

- Kuczerawy, A. 2019. “Fighting Online Disinformation: Did the EU Code of Practice Forget About Freedom of Expression?” In Disinformation and Digital Media as a Challenge for Democracy (European Integration and Democracy Series, Vol. 6), edited by E. Kużelewska, G. Terzis, D. Trottier, and D. Kloza. Intersentia. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3453732

- Lindell J and Ibrahim J. (2021). Something ‘Old’, Something ‘New’? The UK Space of Political Attitudes After the Brexit Referendum. Sociological Research Online, 26(3), 505–524. 10.1177/1360780420965982

- Lindell, J., P. Jakobsson, and F. Stiernstedt. (2022). The Media Welfare State: A Citizen Perspective. European Journal of Communication, 37 (3), 330–349. doi:10.1177/02673231211046792.

- Milan, S. 2017. “Data Activism as the New Frontier of Media Activism.” In Media Activism in the Digital Age, edited by V. Pickard, G. Yang, 151–163. London: Routledge.

- Mudde, C., and C. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2013. “Exclusionary Vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America.” Government and Opposition 48 (2): 147–174. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.11.

- Nord, L. 2020. “Public Service 2020: Året då alla motgångar skymde framgången [Public Service 2020: The Year When All Adversity Obscured the Success.” In Mediestudiers årsbok: Tillståndet för journalistiken 2018/2020, edited by G. Nygren, 118–127. Stockholm: Institutet för mediestudier.

- Nord, L., and T. von Krogh. 2021. “Sweden: Continuity and Change in a More Fragmented Media Landscape.” In The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How Leading News Media Survive Digital Transformation, edited by J. Trappel and T. Tomaz, Vol. 1, 353–380. Gothenburg: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg. doi:10.48335/9789188855404-8.

- Peters, J. D. 2005. Courting the Abyss: Free Speech and the Liberal Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pettersson, K. 2020. ”The Discursive Denial of Racism by Finnish Populist Radical Right Politicians Accused of Anti-Muslim Hate-Speech.” In Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections Between Politics of Culture, Welfare, and Migration in Europe, edited by Norocel, C, Hellström, A and Jørgensen, M, 35–50. Cham: Springer.

- Pickard, V. 2014. America's Battle for Media Democracy: The Triumph of Corporate Libertarianism and the Future of Media Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Press Freedom Index. 2021. https://rsf.org/en/ranking/2021

- Rodriguez, C. G., J. P. Moskowitz, R. M. Salem, and P. H. Ditto. 2017. “Partisan Selective Exposure: The Role of Party, Ideology and Ideological Extremity Over Time.” Translational Issues in Psychological Science 3 (3): 254. doi:10.1037/tps0000121.

- Sarikakis, K., and S. Ganter. 2014. “Priorities in Global Media Policy Transfer: Audiovisual and Digital Policy Mutations in the EU, MERCOSUR and US Triangle.” European Journal of Communication 29 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1177/0267323113509360.

- Schulze, H. 2020. “Who Uses Right-Wing Alternative Online Media? An Exploration of Audience Characteristics.” Politics and Governance 8 (3): 6–18. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i3.2925.

- Segura, M. S., and S. Waisbord. 2016. Media Movements : Civil Society and Media Policy Reform in Latin America. London: Zed Books.

- Sehl, A., F. M. Simon, and R. Schroeder. 2020. ”The Populist Campaigns Against European Public Service Media: Hot Air or Existential Threat?” International Communication Gazette (ahead of print, July 12). doi:10.1177/1748048520939868.

- Sjøvaag, H. 2012. “Regulating Commercial Public Service Broadcasting: A Case Study of the Marketization of Norwegian Media Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 18 (2): 223–237. doi:10.1080/10286632.2011.573851.

- Surowiec, P., and V. Štětka. 2020. “Introduction: Media and Illiberal Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 36 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1692822.

- Syvertsen, T., O. Mjøs, H. Moe, and G. Enli. 2014. The Media Welfare State: Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Vol. 165. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Van Cuilenburg, J., and D. McQuail. 2003. “Media Policy Paradigm Shifts: Towards a New Communications Policy Paradigm.” European Journal of Communication 18 (2): 181–207. doi:10.1177/0267323103018002002.

- Van Dijck, J., T. Poell, and M. De Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Verboord, M., and N. Nørgaard Kristensen. 2021. “EU Cultural Policy and Audience Perspectives: How Cultural Value Orientations are Related to Media Usage and Country Context.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (4): 528–543. doi:10.1080/10286632.2020.1811253.

- Wagner, M. 2019. “Mapping Media and Information Literacy (MIL) in Sweden: Public Policies, Activities and Stakeholders.” In Understanding Media and Information Literacy (MIL) in the Digital Age: A Question of Democracy, edited by U. Carlsson, 87–96. Gothenburg: JMG, University of Gothenburg.

- Wahlström, M., A. Törnberg, and H. Ekbrand. 2021. “Dynamics of Violent and Dehumanizing Rhetoric in Far-Right Social Media.” New Media & Society 23 (11): 3290–3311. doi:10.1177/1461444820952795.

- Ward, D. 2002. The European Union Democratic Deficit and the Public Sphere: An Evaluation of EU Media Policy. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Appendix

Table A1. Benzécri-adjusted eigenvalues of the top 10 dimensions among the active variables.

Table A2. Relations of active variable modalities to dimensions 1 and 2 (eta squared).

Table A3. V-test for modalities in supplementary variables on the two main dimensions.