ABSTRACT

With a lifelong path of funding struggles, cultural industries have been at the forefront of crowdfunding since its early stages in the beginning of this century. Worldwide, the volume of crowdfunding has been growing significantly and it has increasingly become a promising business model for cultural productions. However, research on cultural crowdfunding remains limited. The current study aims to understand how crowdfunding is shaping the cultural economy. We explore the evolution, trends and narratives of cultural crowdfunding, focusing on two crowdfunding platforms – Kickstarter and Bidra. By scrapping the universe of Norwegian cultural campaigns on these platforms in 2016–2021 and combining statistics with discourse analysis, the results demonstrate changes in cultural crowdfunding dynamics, with notable differences across cultural industries. Overall, cultural campaigns mainly acclaim artistic production and financial acquisition, also artists emphasize lack of finances (even in the case when public funding is given) and potential for product sales. This work demonstrates the growth and importance of cultural crowdfunding, especially for some industries (e.g. games), and highlights the need for cultural policy to consider crowdfunding as one of its instruments, extending, for instance, match-funding mechanisms. This study further contributes to the understanding of the cultural crowdfunding phenomenon for academics, policy-makers, and practitioners.

Introduction

Crowdfunding – a practice of obtaining funding from a potentially large pool of micro investors providing small amounts of money to support ideas (Shneor and Mæhle Citation2020) - is an alternative finance mechanism first embraced by artists as an innovation that helped them to tackle the culture sector’s long-term struggle of financing artistic expression. Crowdfunding is also a part of the worldwide fast-paced digitalization that also affects cultural productions. To date, cultural-creative industries (CCIs) are leading in terms of the amount of money raised through crowdfunding campaigns (Boeuf, Darveau, and Legoux Citation2014; Rykkja et al. Citation2020a). Moreover, recent cuts in public funding and growing competition from private donors make crowdfunding an increasingly promising instrument for realizing a broad range of cultural and artistic activities. However, cultural crowdfunding is still a fragmented and unrealized market (Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020) despite the recent growth of the global volume of crowdfunding transactions (Ziegler et al. Citation2021); this growth and the cultural crowdfunding field require further scientific exploration.

Hence, the current study aims to understand how crowdfunding is shaping the contemporary cultural economy. By exploring the evolution of cultural crowdfunding, this study seeks to identify major trends in the various cultural industries and discover the narratives employed in their respective campaigns. We choose to focus on two major crowdfunding platforms used by Norwegian cultural actors, an international platform (Kickstarter) and a national platform (Bidra). Norway was chosen for study for two main reasons. First, despite standing out in terms of extensive public support in the culture sector, crowdfunding is still growing in Norway (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Ziegler et al. Citation2021). This growth means that crowdfunding not only represents a financial vehicle but there is also a more complex rationale behind crowdfunding adoption by artists. Second, due to the country’s relatively small size (approximately 5 million inhabitants), it is possible to work with the entirety of its cultural crowdfunding campaigns, allowing for this empirical investigation to gain broader insights that can inform academics, policy-makers and practitioners.

Accordingly, the universe of cultural crowdfunding campaigns on these platforms in the period 2016–2021 was scrapped, and the campaigns were classified into subcategories according to their cultural sector, following both Kickstarter’s tags and Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circle model. After that, we conducted statistical analysis and discourse analysis of the campaigns. First, we considered the statistical data highlighting the trends of crowdfunding use during the analyzed period and its variation across the different cultural industries (e.g. the high and increasing presence of music versus the low number of theater projects). Subsequently, in the discourse analysis, we focused on narrative frames, i.e. the issues, arguments, or storytelling used in crowdfunding campaigns published on platforms (Majumdar and Bose Citation2018; Nisbeth Citation2009). The effects of linguistic styles in crowdfunding have been addressed in the literature (Gorbatai and Nelson Citation2015; Parhankangas and Renko Citation2017), but the extent to which artists in diverse cultural sectors use narratives to construct their crowdfunding campaigns remains underexplored. The way artists frame their crowdfunding campaign sheds light on artists’ perception of crowdfunding as a mechanism to support artistic production, and it certainly deserves deeper attention to inform the cultural field in an ecosystem of funding.

By combining quantitative and qualitative methods, this paper seeks to contribute to the further understanding of the cultural crowdfunding phenomenon and its dynamics as a part of the art markets. The study demonstrates the growth of cultural crowdfunding and its relevance for the culture sector, especially for certain industries, such as sound recording and gaming. It also contributes to a deeper comprehension of how artists and creators perceive the practice of crowdfunding, its potential and its limitations. Therefore, complementing this brief introduction, the article has five sections. The next section expands on the theoretical background of the cultural economy within the emerging crowdfunding trend. The third section presents the methodology, followed by the results and discussion in the fourth section. Finally, the fifth section provides some final considerations and an agenda for future research.

Theoretical background: the culture sector meets alternative finance

The reality of the 21st century global economic system, driven by digitalization and technological innovation, has been defined as cognitive-cultural capitalism in which cultural-creative industries (CCIs) occupy a central space (Scott Citation2008). Scholars have been discussing the direct effects of the culture sector, such as employment, income generation, and the attractiveness of companies and job creation, as well as its more indirect and abstract aspects linked to the notion of identity, belonging, community formation, and the encouragement of creativity (Throsby Citation2001, Citation2008; Bille and Schulze Citation2006; Scott Citation2008; Towse Citation2020). As a matter of fact, the issue of financing artistic and creative activities has been in the spotlight of academic research, given that, in its broad scope, cultural production has predominantly struggled to obtain funding (Rushton Citation2003; Colbert Citation2012; Agrawal, Catalini, and Goldfarb Citation2014).

Driven by such a challenge amid the contemporary contour, artists were at the forefront of crowdfunding practices from its very beginning. The ArtistShare platform, founded by musicians in 2003, was the first crowdfunding platform, mainly dedicated to financing artistic works (Bannerman Citation2012; Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b). However, cultural crowdfunding has been largely unexplored in academic literature, even if CCIs are raising the largest amounts of money in campaigns (Ibid.; Boeuf, Darveau, and Legoux Citation2014). Moreover, there is an alarming tendency of hardships in acquiring public funding due to austerity policies as well as increasing competition for private sponsors and donors (Peltoniemi Citation2015; Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020). In this sense, within the framework of worldwide fast-paced digitalization reconfiguring cultural productions (Nordgård Citation2018), there is an urgency to expand the understanding of cultural crowdfunding, its evolution, trends, and discourse.

Cultural and creative crowdfunding (hereafter CCCF) then comes as an innovative alternative channel for financing arts and culture. In this sense, the theoretical background of this paper needs to address both the cultural economy literature and the field of alternative (technological) finance, specifically crowdfunding. Therefore, this review includes the following three subsections: culture economy, the alternative finance of crowdfunding in the cultural and creative sectors, and frames used in cultural-creative crowdfunding.

Culture economy

The culture sector is inherently complex and diverse. The word culture itself carries both anthropological and sociological dimensions and is defined as a ‘set of attitudes, beliefs, customs and practices that are common or shared by some group’ (Throsby Citation2001, 4). There is also a more practical definition of culture related to cultural activities and products. The latter represents the object of study in the present work. Potts (Citation2016) argues that the cultural sector is defined by the intense presence of creativity, and Throsby (Citation2001, Citation2008) also acknowledges the intention to generate and communicate symbolic meaning and the potential production of intellectual property behind cultural and creative goods. From this perspective, value creation in cultural industries is quite distinct from the pure economic/monetary value. Notably, the definitions of the diverse culture (and creative) sector and the CCIs are subject to variation but often seem to overlap with no strict conceptualization (Hesmondhalgh and Pratt Citation2005; UNESCO Citation2013; Machado Citation2016).

According to Throsby (Citation2001), to grasp a definition of cultural goods and services, activities, and other creative phenomena, there are six forms of (cultural) values embedded in the notion of the cultural sector and its industries, which represent an attempt to translate the symbolic-intangible dimension of the arts and culture into economic terms. To name: 1) aesthetic value, arising from the object’s aesthetic properties, such as beauty and harmony; 2) spiritual value, manifested in religious/spiritual context, in that the activity/product has some particular meaning for those who share that belief; 3) social value, derived from cultural activity/manifestation that confers a sense of identity in space, connecting a society in its various hierarchies; 4) historical value, expressed by historical connections, serving as a rescue of the past as a way to ‘illuminate’ the present; 5) symbolic value, generated by symbolism and by the meaning that a certain cultural good or expression awakens in the individuals who consume it; and 6) authenticity value, resulting from originality, demonstration of uniqueness and real characteristic of a certain work (Throsby Citation2001, 29). These values are indeed not strictly monetary or measurable.

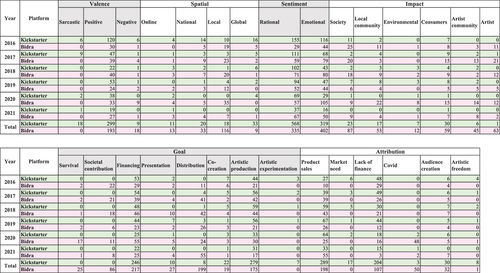

There is, then, a pivotal element of intangibility associated with the CCIs that cannot be ignored when conducting research in the cultural field, which CCCF is part of. However, the inherent diversity of the cultural industries also helps in dealing with such complexity: the different industries can be separated according to their level of abstraction. To simplify this debate, Throsby (Citation2008) introduced the concentric circles model (), in which CCIs are organized into four groups: core cultural expressions (e.g. literature, music, performance, and visual arts), other core creative industries (e.g. cinema, museums, photography), wider cultural industries (e.g. publishing, recording, video games), and related industries (e.g. fashion, design, architecture). Such a distinction is crucial to comprehend the diverse dynamics of the broad variety of cultural production, which again involves the use of crowdfunding. Later, in the methodology section, we acknowledge how we followed such structure in our data analysis.

Figure 1. Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circles model.

Scholars in the field of CCCF have discussed the importance of distinct economic features, according to the four groups presented above, for fundraising results (Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021). The CCIs are set apart from the core cultural arts/expressions when considering cultural/aesthetic content and (non)reproducibility. For instance, design, sound recording, and video games, are to some extent more subject to reproducibility, and are seen as more innovation-driven, tech-intensive and with higher appeal to commercialization (Ibid.). These aspects facilitate their production and distribution processes, whereas for some of the core cultural arts and creative industries, there are unique dimensions which detach them from normative economic activity, such as intrinsic motivation, superstar effects, oversupply, experience goods, highly differentiated products, and expressive demand uncertainty (Bille and Schulze Citation2006; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2022). From this perspective, crowdfunding practices can somewhat disrupt the traditional art market (Boeuf, Darveau, and Legoux Citation2014; Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020; Dalla Chiesa and Dekker Citation2021); therefore, there is a need to further comprehend the use of crowdfunding amid the culture sector and its intrinsic dynamics.

The alternative finance of crowdfunding in the culture sector

According to Willfort, Weber, and Gajda (Citation2016), crowdfunding, in a nutshell, is defined as the ‘co-thinking’ of micro investors who provide small amounts of money to support ideas. Moreover, crowdfunding can be interpreted as community-enabled financing (Shneor and Flåten Citation2015), following the principles of crowdsourcing, adapted to the context of fundraising. Mostly online-based, crowdfunding provides benefits going beyond the acquiring of monetary value, e.g. leveraging the power of social networks and user-generated (social) innovation (Mollick and Kuppuswamy Citation2016; Toxopeus and Maas Citation2018), as it can also be understood as a collective effort of investing and supporting projects that people believe in (Ordanini et al. Citation2011). Hence, such a socioeconomic perspective on crowdfunding can relate better to the distinct and intangible reality of the economy of the arts, differentiating the CCCF literature from the theories of creators as entrepreneurs seeking investment for their business ideas (Dalla Chiesa and Dekker Citation2021).

Indeed, there are diverse models of crowdfunding (Rykkja et al. Citation2020a; Carè, Trotta, and Rizzello Citation2018). Studies on this alternative finance mechanism agree that it can be basically divided into two financing logics, investment and noninvestment, within four main formats: lending-, equity-, reward-, and donation-based. In general, the first two models are more common within the first logic, and the last two models fit the second logic (Shenor, Zhao, and Flåten Citation2020). While the models of lending and equity actually represent the largest share of crowdfunding volume, in terms of global statistics, nonexperts associate this finance mechanism with (almost exclusively) the other two types: reward- and donation-based (ibid). Nevertheless, both reward- and donation-based crowdfunding practices are the most commonly used within the culture sector (Shenor, Zhao, and Flåten Citation2020; Rykkja et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Given the focus of this paper on arts and culture production, when referring to the concept of (cultural) crowdfunding or its literature, the current article does not further consider the models within the investment logic. Moreover, the two chosen platforms in the study (Kickstarter and Bidra) adopt the reward-based model.

The incipient literature on CCCF has mostly focused on the reasons for campaigns’ success (Mollick and Kuppuswamy Citation2016; Josefy et al. Citation2017; Kaartemo Citation2017), the role of crowdfunding as a complementary or substitute source of funding for the art community (Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020; Alexiou, Wiggins, and Preece Citation2020; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021), and crowd engagement (Mollick and Nanda Citation2014; Josefy et al. Citation2017; Bürger and Kleinert Citation2021). The majority of these contemporary studies naturally follow, to some extent, the socioeconomic approach, given the specificities of cultural and creative products and projects. Nevertheless, the potential of crowdfunding not only as an alternative financing tool but also as an instrument of a symbolic dimension further encouraged by prosocial behavior has been marginalized. Moreover, there is a lack of a framework acknowledging crowdfunding’s role in cultural project development as a specific case of co-production and a practice of value(s) co-creation (Boeuf, Darveau, and Legoux Citation2014; Chaney Citation2019; Carè, Trotta, and Rizzello Citation2018; Minutolo et al. Citation2018; Toxopeus and Maas Citation2018; Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021).

Various theories can help to comprehend crowdfunding adoption as an alternative financing mechanism and co-creation tool within the multiple CCIs, as some scholars have already pointed out (Quero, Ventura, and Kelleher Citation2017; Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021). For instance, the notion of intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation – inspired by self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000), network analysis (Granovetter Citation1983), social capital theory (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Citation1998), and entrepreneurial research (Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2016) – can contribute to the development of cultural crowdfunding frameworks. Given the increasing importance of crowdfunding during at least the past 15 years, it is possible to draw on some insights into the long-term economy, reputation and aesthetic practices of arts. Further investigation is especially relevant in light of the unprecedented growth of the online community due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this sense, the literature also indicates that crowdfunding practices are influenced by contextual factors (Kaartemo Citation2017) and the geography of proximity vis-à-vis online spaces (Breznitz and Noonan Citation2020; Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022). Thus, the global pandemic outbreak and successive lockdowns may have caused changes in the cultural crowdfunding arena, forcing various artists to reinvent themselves in a post-digital context. In fact, crowdfunding utilizes a very particular method to engage with audiences through ‘internet-based, computer-mediated and asynchronous communication, through a crowdfunding platform’ (Maehle et al. Citation2021, 2). As written appeals account for a large portion of interaction and decision-making information in this case, effective communication is key to crowdfunding campaigns’ success (Gorbatai and Nelson Citation2015; Parhankangas and Renko Citation2017). Anderson (Citation2016) acknowledges the pivotal role of narratives for a crowdfunding project.

Narrative can be understood as a story or a set of storylines that can be interpreted through frames communicating the ‘wh-’ questions of a certain issue (Nisbeth Citation2009). According to Maehle et al. (Citation2021), framing refers to how to describe a project in the most convincing way in order to gain backers. To our knowledge, the framing of crowdfunding narratives has not yet been explored in the CCCF literature. Due to the peculiarities of the cultural and creative economy, constructing CCCF frames can shed light on artists/creators’ engagement in this alternative finance mechanism.

Cultural (and creative) crowdfunding in frames

This subsection explains the frames proposed to further comprehend how CCCF campaigns build their virtual narratives, which currently represents a gap in the field. Information is never purely objective, and therefore the way project descriptions are framed can trigger emotional response (Nisbeth Citation2009; Maehle et al. Citation2021) and influence the campaign process – from its setup to the end results. We believe that to fully understand the rationale behind CCCF and artists’ motivations for using crowdfunding, it is critical to explore the way artists and creators describe and frame their campaigns. Maehle et al. (Citation2021) provided an overview of the frames discussed in the crowdfunding literature, focusing on identifying the frames used in sustainable crowdfunding campaigns. CCCF and sustainable crowdfunding are similar, as both have dynamics much more complex than in conventional crowdfunding within a socioeconomic perspective (Maehle et al. Citation2021; Dalla Chiesa and Dekker Citation2021).

Hence, inspired by Maehle et al. (Citation2021), we identify six relevant frames within the CCCF that consider the culture sector’s specificities and contribute to the further development of the CCCF literature. The proposed frames are the following:

Sentiment frame: rational vs. emotional appeals

From the broad crowdfunding literature, the ‘sentiment frame’ is an established one, with two distinct appeals: rational and emotional (Majumdar and Bose Citation2018; Chen, Thomas, and Kohli Citation2016). Rational appeal refers to communication based on evidence, presenting factual points, rather than persuasion through emotion (Majumdar and Bose Citation2018). Presenting facts and statistics can increase the confidence of potential investors when making an investment or donation decision (Ibid.; Parsons Citation2007). However, emotional appeal may also affect backers’ intentions in crowdfunding (Chen, Thomas, and Kohli Citation2016; Mitra and Gilbert Citation2014; Rhue and Robert Citation2018). For instance, research (Mitra and Gilbert Citation2014) shows that emotional language filled with feelings, e.g. responsibility or hope, can increase crowdfunding success. We include this frame for CCCF, although it was not considered in Maehle et al.’s (Citation2021), as emotional expression can be core to some activities in the culture sector. A cultural-creative project therefore often relies not only on rational communication but also on an emotional appeal (or even both).

Goal frame

The goal frame is already widely used in social marketing and so it is identified in crowdfunding (Maehle et al. Citation2021), also conceivable to CCCF communication. It addresses the project’s objectives and aspirations, directly encompassing what the project is about and what will be achieved if the campaign is successful. We extended the established promotion or prevention focus (Ibid.) by incorporating the specificities of the culture sector that might be manifested when adopting crowdfunding, such as intrinsic motivation to create or art for the sake of art (Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021) and co-creation (Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021). Furthermore, considering the struggles of both the art and art labor markets, the CCCF goals may include, for instance, using crowdfunding as a carrier intermediation and audience creation, bypassing traditional art market gatekeepers, and trying to deal with high uncertainty and asymmetric information (Dalla Chiesa and Dekker Citation2021; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021) or even straightforward financing given the long-term challenge of not having funding (Abbing Citation2008; Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020).

Impact frames

Impact frames target who and/or what will be influenced by the cultural-creative project. It embodies the potential effect of the project on the artist, consumers and/or broader socio-spatial sphere, which can be direct or indirect, concrete, or abstract (symbolic). This frame complements the goal frame, illustrating to a larger degree who and what will benefit if the campaign is successful. In this sense, within this frame, we consider narratives related to Throsby’s (Citation2001) cultural values, e.g. social, symbolic, authentic; the indirect effects linked to CCIs, e.g. identity and community formation, belonging, and encouragement of creativity (Throsby Citation2001; Bille and Schulze Citation2006; Potts Citation2016); and the economic features of experience and Veblen good and reproducibility within cultural products (Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021). Both artists/creators and backers react differently depending on what they perceive that the cultural project comprehends and what it can generate for individual backers or more broadly in terms of societal welfare.

Attribution frame

The frame of attribution relates to why the artists and creators have decided to use crowdfunding for their cultural-creative project. This frame addresses the reasons behind their choice of an alternative channel to finance their idea, instead of going through the traditional art market funding mechanisms and gatekeepers. Being early adopters of such a sociotechnical innovation (Dalla Chiesa and Dekker Citation2021), artists have a diverse rationale for using the mechanism of crowdfunding, which are connected to the peculiarities of CCIs and also overlap with the goal frame. For instance, the artists and creators can include in their campaign’s description the elements that can be connected to their intrinsic motivation to create, artistic authenticity, demand uncertainty, lack of finance, and struggles of the art labor market (Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021; Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020; Abbing Citation2008).

Valence frames

Valence frames refer to using either positive or negative messages, playing on a crowd’s emotions (Maehle et al. Citation2021). In positive framing, the crowdfunding campaign communication focuses on the benefits of, in the CCCF case, supporting that specific art activity, such as a music festival bringing people together and offering a unique experience. On the other hand, negative frames emphasize the harmful and perverse characteristics of the art market, such as the end of an artist’s career or, more broadly, pessimist views of contemporary society, which is connected to Stoknes’ work (2014, apud Maehle et al. Citation2021). The three main negative frames are apocalypse, uncertainty, high costs or losses. In fact, studies have indicated that a positive approach can be more effective, whereas overusing negative framing can decrease trust and result in counteractive reactions (Manzo Citation2010; Maehle et al. Citation2021).

Spatial frames

Spatial framing addresses the location of the CCCF project considering the aspect of the relevance (or not) of geographical proximity for funding results (Breznitz and Noonan Citation2020; Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022). From this perspective, studies (ibid.) have been discussing the locational dimension regarding the choice of either local or international platforms to launch a campaign. Therefore, framing a project’s spatiality alludes to whether it is important to emphasize the project location. For example, when there is a possible benefit for the local communities, city, or national scene (e.g. the opening of a new museum), the project communication can focus on the proximity aspect for backers and all the direct and indirect effects of the CCIs to society, as mentioned previously in this literature review section. Nonetheless, in the advent of digitalisation promoting virtual cultural production and consumption, some cultural-creative projects do not necessarily have to frame their campaign’s particular spatiality since the respective product can have an international (or online) demand (Nordgård Citation2018; Towse Citation2020).

In the next section, we display how we composed our data sample and operationalized these frames to the data analysis.

Methodological approach

We collected data from totally or partially funded cultural crowdfunding campaigns endorsed by Norwegian actors/creators on a local platform (Bidra) and an international platform (Kickstarter) from January 2016 to December 2021. Noteworthy there are several reasons for choosing Norway as a case study, and the first part of this methodology section is dedicated to the Norwegian cultural economy before describing the data process – sampling, operationalization, and methods of analysis.

Cultural sector in Norway

The Norwegian political economy is well known worldwide for its social welfare system with its inclusive and extensive coverage. The country’s relatively small size, approximately 5 million inhabitants, makes it possible to work with the universe of cultural crowdfunding campaigns and thus allows the empirical investigation to point out broader insights that can inform academics, policy-makers and practitioners. Moreover, because of the petroleum industry and the Government Pension Fund Global (‘Oil Fund’), the public sector budgets in which culture is included are relatively generous (Henningsen, Håkonsen, and Løyland Citation2017; Røtnes, Tofteng, and Marie Frisell Citation2021). Respectively, the Norwegian culture sector has been heavily financed by public authorities, with a constant increasing trend: government expenditure in ‘Recreation, culture, and religion’ was more than NOK 52 million in 2016 and more than 66 million in 2020, according to Statistics Norway (Citation2021).

However, even with substantial public funding, crowdfunding numbers have been growing. For instance, from 2019 to 2020, the Norwegian crowdfunding volume grew by 102%, according to the 2nd Global Alternative Finance Market Benchmarking Report (Citation2021). It is important to mention that those numbers include the other types of crowdfunding models within investment logic (equity and lending) that CCIs are currently not using. Nevertheless, when disaggregated, we observe that both reward-based and donation models also follow a trend of expansion, although we cannot separate by sector, e.g. CCCF or civic crowdfunding (Ziegler, Shneor, and Zheng Zhang Citation2020). This fact means that the decision of using crowdfunding can be motivated by nonfinancial reasons, which can include, for example, career intermediation, audience creation, and artistic freedom. Therefore, with the universe of CCCF campaigns and the possibility of finding diverse rationales for crowdfunding adoption, Norway arises as an encouraging case to study.

Data collection

The data sample consisted of the universe of Norwegian CCCF campaigns totally or partially funded through either the Kickstarter or Bidra platform between January 2016 and December 2020. Based on the literature on CCIs’ decisions to conduct crowdfunding campaigns on global versus local platforms (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022), we chose both types of platforms: Kickstarter is the world’s largest platform for the culture-creative sector, and Bidra is the largest platform in Norway (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b). Kickstarter was launched in 2009 following the all-or-nothing model, meaning that the creators only collect the money when they reach (or pass) the goal amount, with the vast majority of the projects fitting the reward-based format. The Norwegian platform, Bidra, came later, in 2014, allowing both reward-based and donation models, where creators can receive the amount raised if it is considered an ‘adequate funding’ – there is no clear requirement here, i.e.: goal, Bidra decides in consultation with the project owner (Bidra Citation2021).

Considering Bidra’s launch date, its time of setting in the market, and the 2nd Global Alternative Finance Market Benchmarking Report – which shows the most significant growth of reward-based crowdfunding between 2016 and 2017 for Norway, we decided to start the data scrapping from the beginning (January) of 2016. Moreover, we covered the entire period to the end (December) of 2021 to ensure that we could observe the effect (or not) of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak and ‘normalization’ within the CCCF evolution, trends, and narratives.

We manually scraped all funded Norwegian projects in Kickstarter, excluding the projects tagged by Food, Journalism, and Technology, as we based our study on Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circles model, which does not include those industries. Some campaigns having a Norwegian city as a location but a non-Norwegian as an artist/creator were also excluded, e.g. an Italian director wanting to raise money to go somewhere in Norway to film a part of her project. Ultimately, we collected a total of 235 funded Norwegian CCCF projects in Kickstarter. In addition, we manually scraped all totally or partially funded cultural-creative projects on Bidra, using the search mechanisms with words such as ‘art’, ‘culture’, ‘book’, etc.,Footnote1 since Bidra does not have preestablished categories for projects. At the end, we collected 310 projects on Bidra.

Data analysis

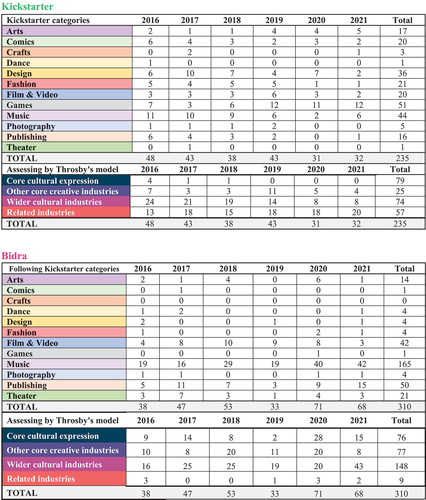

The descriptions of the 545 collected cultural-creative projects were stored in a database and uploaded to NVivo software, a program that allows both qualitative and quantitative analysis of data (NViVo Citation2019). Before proceeding with the data analysis through NVivo, we organized our database to also conduct some basic statistics. First, we categorized Bidra’s project according to Kickstarter’s tags, to name Art, Comics, Crafts, Dance, Design, Fashion, Film & Video, Games, Music, Photography, Publishing, and Theater, to have comparable variables for our graphics. Appendix A shows the number of campaigns per tag and per year for both platforms.

Furthermore, we delved deeper into the nature of the projects to classify them following Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circles model without letting the tag define to which of the four groups the CCI project belong (core cultural expressions, other core creative industries, wider cultural industries, related industries). The aim of this classification method was to preserve the complexity and diversity inherent in cultural productions chains, meaning that, for example, a project tagged as music was not necessarily into the core arts once the funding was specifically collected for recording, which is a wide CCI. This structure permitted our statistical results to be aligned with the literature regarding which group of CCIs are more inclined to/are using crowdfunding (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021; Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022).

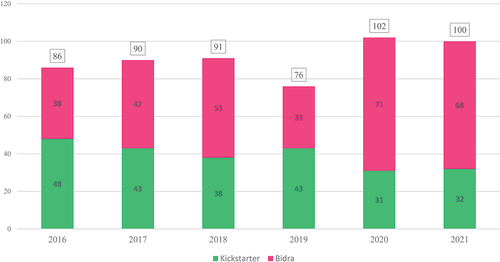

In parallel, based on the CCCF frames presented in the previous section, we created a set of codes in NVivo for the qualitative and quantitative analysis. According to Saldaña (Citation2015), codes were adapted and added by attending a provisional coding procedure, again based on the literature (Section 2). Both authors independently coded the data in the project descriptions and discussed the codes until full consensus was reached (Ibid.; Maehle et al. Citation2021). In Appendix B, we illustrate the coding with examples of phrases from projects’ descriptions selected as evidence for the presence of a particular frame. While reading each project description, we classified the parts of the text into different codes within the six proposed frames. This means that we conducted a discourse analysis (Haguette Citation2001) by studying the written language/linguistic style of the collected projects. In the same project, we sometimes encountered more than one code in the same frame while consulting all the proposed frames through the whole reasoning process, seeking to observe trends in the CCCF narrative. displays the final codes for operationalizing the CCF frames. The discourse analysis results are presented in the next section together with the main statistics and discussion.

Table 1. Final codes for analyzing the CCCF frames in project descriptions.

Results and discussion

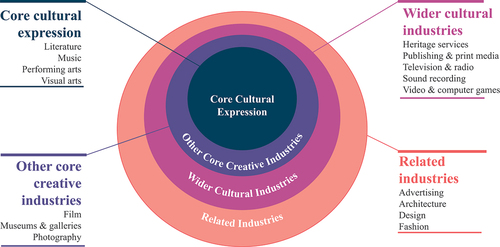

Evolution and trends of CCCF in Norway: the statistics

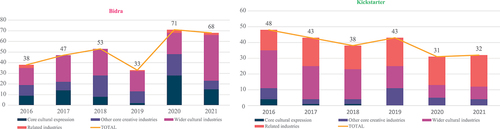

The statistical results related to the evolution of Norwegian CCCF demonstrate a growth of 16,28% in the number of funded campaigns between 2016 and 2021 and an increasing number of funded projects on Kickstarter and Bidra – from 86 projects in 2016 to 100 projects in 2021. Although there was a growing tendency from 2016 to 2017, also followed in 2018, there was a decrease of almost 38% in 2019, with the lowest number of totally or partially funded CCCF campaigns, 76 in total. In contrast, 2020 comes as the year with the highest number (102 projects), slightly higher than in 2021 with 100 projects. Another interesting tendency is a changing dynamic in Norwegian cultural crowdfunding: a growing preference for a national platform, with an increasing number of campaigns on Bidra and a decreasing number on Kickstarter, except in 2019, when the number of projects on Bidra decreased and on Kickstarter increased. However, this dynamic change becomes even more evident again in 2020, with Bidra publishing the highest number of cultural-creative campaigns ever, 71. This can be a direct effect of the COVID-19 outbreak, right in the beginning of that year, and the pandemic can have also contributed to a further shift to national platforms. illustrates these points.

Figure 2. Evolution of totally or partially funded Norwegian CCCF campaigns in the period of 2016–2021 on the Kickstarter and Bidra platforms.

The identified trend of overall growth combined with a gradual shift from the global platform to the local one can be interpreted in a longitudinal perspective as a sign of maturation of the Norwegian CCCF market. The importance of providing local solutions was especially evident during the recent pandemic as a manifestation of solidarity for the local artists who were affected by social isolation and could not perform their activities in a normal way. Festivals are a great example here given their local affiliation, with the projects using the local platform to stay closer to the community. In this sense, two propositions can be pointed out: (P1) The greater the local market maturity and familiarity with crowdfunding, the more likely the use of a local platform; (P2) the greater the dependency of creative work on understanding of local particularities (e.g.: the dynamics of the pandemic on a local level) the more likely the use of a local platform.

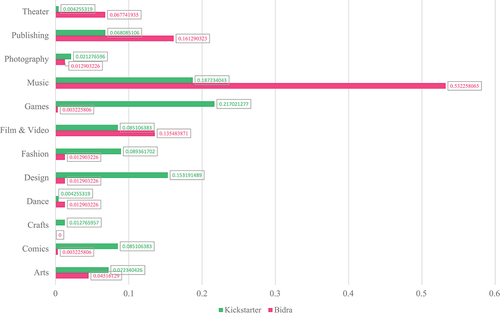

Moreover, there are notable differences across the different CCIs, both in terms of Kickstarter’s categories and the four groups of Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circles model. While considering Kickstarter’s categories, we observe that music dominates on Bidra, making up 53% of all cultural-creative campaigns on the platform, followed by publishing (16%) and films & video (14%) – see . Thus, music is more than 3 times more represented on Bidra than the second category, publishing. On Kickstarter, there is no such dominance, although the game industry has the highest number of projects, representing 21,70% of the campaigns between 2016 and 2021. This industry has only 1 project in Bidra in the considered period, which can be explained by its global appeal and, often, virtual audience. Nevertheless, music also appears high up (2nd position) in the international platform, with 44 campaigns (18,71%) in total, followed by 36 design projects. illustrates the presence of each category on each platform, according to Kickstarter’s categories and the complete table with all the numbers per category per year can be found in Appendix A for both platforms.

Figure 3. Comparison of the totally or partially funded Norwegian cultural crowdfunding campaigns on Kickstarter versus Bidra in 2016–2021, categorized according to Kickstarter’s tags.

The aforementioned observations demonstrate that certain sectors prefer the international platform, while others prefer the local one. This can be explained by the extent of sector’s local relevance and appeal, as well as by its scalability and reproducibility potential, and consumption characteristics. Hence, to gain more in-depth perspective in these sectorial differences, we categorized the collected campaigns according to the four groups of Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circles model (see ).

Figure 4. Comparison of the totally or partially funded Norwegian cultural crowdfunding campaigns on Kickstarter versus Bidra in 2016–2021, categorized according to Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circle model.

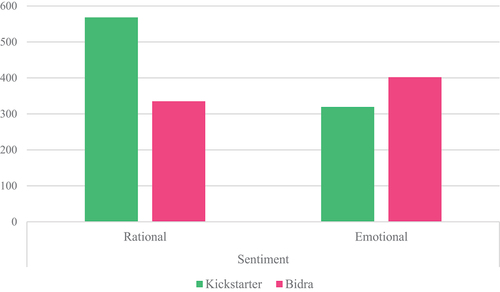

Figure 5. Number of references per code within the sentiment frame in project descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra platforms in 2016–2021.

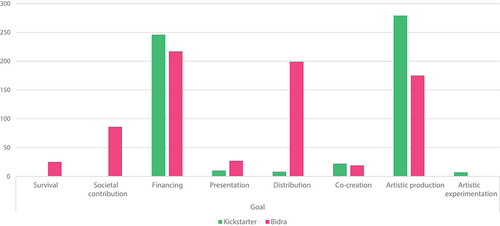

Figure 6. Number of references per code within the goal frame in project descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra platforms in 2016–2021.

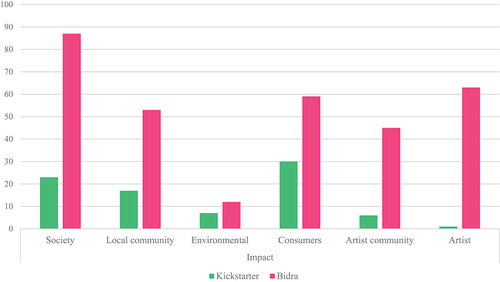

Figure 7. Number of references per code within the impact frame in project descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra platforms in 2016–2021.

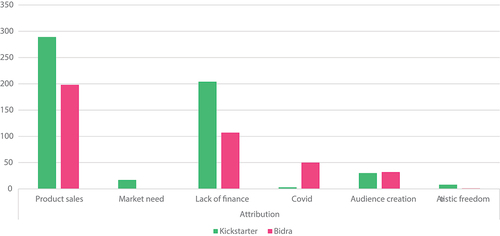

Figure 8. Number of references per code within the attribution frame in project descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra platforms in 2016–2021.

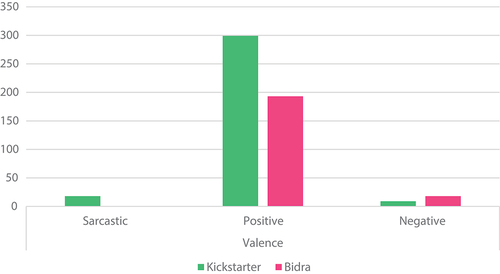

Figure 9. Number of references per code within the valence frame in project descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra platforms in 2016–2021.

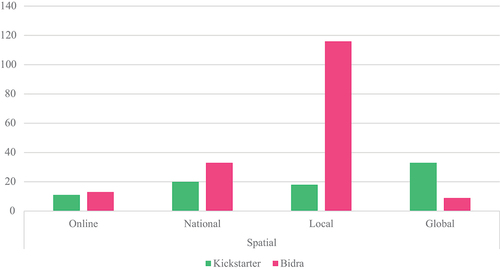

Figure 10. Number of references per code within the spatial frame in project descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra platforms in 2016–2021.

The literature on CCCF shows that there is a need for empirical studies mapping crowdfunding suitability/appeal vis-à-vis different cultural industries/creative projects (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021). The graphics in are an attempt to address this gap by illustrating the trends and evolution of funded Norwegian CCCF campaigns regarding their type of industry: core cultural expressions, other core creative industries, wider cultural industries or related industries (Throsby Citation2008). We observe that projects from wider cultural industries have a significant presence on both Kickstarter and Bidra throughout the years, also following the general trend of decreasing numbers on Kickstarter and increasing numbers on Bidra. Notably, this group is composed of, for instance, sound recording and publishing/printing, which are activities highly inclined to use crowdfunding, given their scalability and reproducibility potential, and that are not necessarily influenced by proximity to backers (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021; Nordgård Citation2018). This finding is especially interesting for the campaigns previously classified as music since, in their nature, their majority actually represents sound recording. In Bidra’s case, for example, more than 40 campaigns in 2021 aimed to record a CD with Norwegian classics, and this can explain the choice of a local platform, which is related to the language matter (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b). Similarly, the group of other core creative industries is present on both platforms with no strong pattern, and again, the choice of international or local platform depends on the project, e.g. if a film is in Norwegian, a local platform seems to be the most obvious choice.

Moreover, it is intriguing to note the dynamics of core cultural expressions. While there were few projects on Kickstater in 2016, there were none in 2021; and, although demonstrating an oscillating pattern, this group was present on Bidra for all the years, with a significant number in 2020 of 28 projects, representing the largest group for this year. One of the possible explanations for this occurrence is that COVID-19 pushed the core cultural expression industries to reinvent themselves virtually when traditional income generation sources became unavailable due to lockdowns and social distancing. In addition, the importance of language can also explain the dominance of core industries on Bidra compared to Kickstarter, as literature, performing arts and music are sensitive to the written/spoken language. On the other hand, related industries stand out on Kickstarter, with Bidra not having this group either in 2017 or 2018. Fashion and design represent the majority of the campaigns. Such industries use crowdfunding as a way to increase market visibility (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021); hence, they choose an international platform instead of being limited to a relatively small (Norwegian) market.

In sum, we propose that (P3) the greater the scalability and reproducibility potential, the more likely the use of crowdfunding for a cultural-creative project – as already established in the literature (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021). In addition, the choice between a local or an international platform depends on the sector’s concentration and market appeal, interlinked with local particularities, such as a national language. If the quantitative analysis presenting the evolution and trends on Norwegian CCCF allowed to draft some general points, to further understand its dynamics, the next subsection goes more in depth by discussing the results of the discourse analysis of the campaigns’ narratives.

Narratives of CCCF: the discourse analysis results & discussion

The discourse analysis results are displayed alongside the six CCCF frames proposed in Section 2. See Appendix C for a complete table per year. Noteworthy that when comparing to Maehle’s et al. (Citation2021) original framework, five out of six frames were kept similar. The exception was the sentiment frame, which was added in this study to capture the pivotal place of emotional expression for arts and culture. Moreover, we excluded the temporal frame, as cultural-creative campaigns have less focus on the long-term effects compared to the sustainable crowdfunding campaigns.

Sentiment frame

On both platforms, projects use sentiment framing rational as well as emotional (see ). Rational descriptions are predominant on Kickstarter, whereas emotional descriptions dominate on Bidra. This can relate to the characteristics of the target audience. Due to its international coverage, the diversity of backers is greater on Kickstarter, which influences the decision to present facts and figures as a more standardized way of communication. Moreover, as a large, well-established platform, Kickstarter has many backers with a great deal of crowdfunding experience. Such expert backers are more inclined to base their decision on factual information instead of emotions (Ahsan, Cornelis, and Baker Citation1018). Additionally, project creators on Kickstarter tend to be more experienced and business-oriented, which may lead to less use of emotional language (Kotler and Armstrong Citation2020). On a local platform such as Bidra, the project creators are physically and linguistically closer to the backers, which can increase the use of emotional language. In addition, the number of projects on Bidra has heavily increased during the COVID-19, which can explain the prevalence of emotional framing. While asking for support during the major crisis, such as the pandemic, many creators tended to appeal to feelings and emotions. Hence, all in all, we believe that (P4.a) cultural campaigns on global platforms are more likely to use rational appeals as their sentiment frame, especially in the sectors adopting crowdfunding as a business model, e.g. design and fashion; while (P4.b) cultural campaigns on local platforms tend to use more emotional framing, particularly when related to events of social commotion, e.g. Covid-19.

Goal

When exploring the goals of the CCCF campaigns, we find that a variety of goals differ from the expected one of (only) collecting finances for cultural-creative projects, which is still heavily present on both Kickstarter and Bidra (see ). First, societal contribution is quite important for Bidra’s projects. This finding can be attributed to the proximity of these project to the local community (Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b). Given that Bidra mostly reaches the Norwegian audience, it is likely to expect a higher demand for cultural productions focusing on social values due to Norwegian cultural specifics (i.e. a feminine society dominated by values of caring for others; Hofstede Citation2011). Additionally, only appearing on Bidra is the goal of survival connected to proximity to backers, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Last, it is noteworthy that there is a higher number of distribution goal frames on Bidra. This can be explained by the fact that many creators are using Bidra as a distribution channel through the national mailing system, as there is no well-established e-commerce retail company for CCIs in Norway. We believe that the main contribution of such observations subject to further generalizability is to indicate (P5) that cultural campaigns on local platforms are more likely to explicitly state in their goal the symbolic dimension of social contribution.

Impact

Regarding the impact frame, the main finding is that projects on Bidra use this frame more actively than those on Kickstarter in every category (society, environment, artists, etc. (see ). Once again, this finding can be explained by the bias of proximity to the local community (Rykkja et al. Citation2020b; Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022) and the characteristics of Norwegian society, which emphasize the importance of social values and aspects related to corporate social responsibility and responsible innovation (Hofstede Citation2011; Hesjedal et al. Citation2020). Generally, this observation provides a reassurance of the previous propositions in the sense that (P6.a) cultural campaigns on local platforms are more likely to explicitly state their influence/effect on socio-spatial and communal dimensions. (P6.b) Cultural campaigns on global platforms, especially in the sectors adopting crowdfunding as a business model and retail mechanism, have less tendency to frame their positive impact, let alone on a broader symbolic level.

Attribution

While observing the reasons artists/creators attribute to their decision to use crowdfunding, there are two main trends: product sales and lack of finances () – both widely recognized in the literature (Bannerman Citation2012; Agrawal, Catalini, and Goldfarb Citation2014; Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021; Handke and Dalla Chiesa Citation2021). For product sales or e-commerce, the platform decision depends on the projects’ nature and aspirations. On both Kickstarter and Bidra, (P7) this attribution type is similar to pre-ordering (Belleflamme, Lambert, and Schwienbacher Citation2014; Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021); however, on international platforms, it is more strongly related to market visibility and artistic/creative production on demand (Ibid.; Handke and Dalla Chiesa 2022), while on Bidra, it is related to a local distribution channel. Regarding attributing the reasons for projects to the hardships of financing the arts and culture (Abbing Citation2008; Lazzaro and Noonan Citation2020), it is worth highlighting that many of the projects are within categories that would not be publicly funded (e.g. comics, games) or are created by amateur and not well-established artists (Dalla Chiesa and Dekker Citation2021).

Valence

Positive valence framing is the most common on both Kickstarter and Bidra (see ), which is consistent with the literature indicating that a positive approach can be more effective than negative language (Manzo Citation2010; Maehle et al. Citation2021). Noteworthy Kickstarter has a more commercial appeal with a more well-established marketing orientation. This may explain the higher presence of positive language in the campaigns’ descriptions of Kickstarter, as highlighting the quality and benefits of products is a part of a common marketing strategy (Kotler and Armstrong Citation2020). We believe that (P8) cultural campaigns will most likely employ a positive framing; however, due to high creativity potential of such campaigns, there is room for different valences to emerge, such as sarcasm which was found in some of the Kickstarter’s projects.

Spatial

As expected, Bidra’s projects frame their location more emphatically given proximity bias (Breznitz and Noonan Citation2020; Rykkja, Haque Munim, and Bonet Citation2020b; Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022), focusing on the benefits that the project can bring to the city/region where it takes place or even to the national scene - see . On the other hand, to increase market visibility (Rykkja and Hauge Citation2021), some projects on Kickstarter give greater importance to global outreach, framing international coverage. Notably, Covid-19 emphasized the importance of the virtual/online space for cultural production and consumption, reinforcing the earlier findings on digitalization shaping the culture sector and the post-digital context (Nordgård Citation2018; Towse Citation2020). Overall, we believe that (P9.a) cultural campaigns on international platforms tend to underline their global appeal, with increasing focus on the possibility of virtual/digital consumption – especially relevant for the game industry; while (P9.b) cultural campaigns on local platforms will emphasize the benefits for the local community by highlighting the project location (neighborhood, city, country, etc.)

Conclusion

Crowdfunding as a novel socio-technical practice in which artists were early adopters provides an innovative opportunity to tackle the culture sector’s long-term struggle of financing itself while representing more than an economic mechanism. Nevertheless, CCCF is fragmented, lies below its market potential, and lacks a more socioeconomic and artistic perspective. Hence, this article aims to understand how crowdfunding is shaping the contemporary cultural economy by exploring the evolution of CCCF, identifying major trends within the diverse CCIs and discovering the narratives employed in the campaigns. This investigation focuses on the universe of Norwegian totally or partially funded cultural-creative projects on a local platform (Bidra) and an international platform (Kickstarter) in the period 2016–2021.

Through a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods, the study demonstrates the growth of cultural crowdfunding and its relevance for the culture sector vis-à-vis the various industries, e.g. the outstanding trend of adopting this mechanism for recording (Bidra) and games (Kickstater). In addition, it indicates an increasing preference for the local platform versus the international one, emphasized during the COVID-19 outbreak and partly explained by the increasing maturity of the local cultural crowdfunding market.

Further, we seek to fill the gap in how artists and creators construct storytelling in their campaigns’ descriptions. The way artists frame their crowdfunding campaign sheds light on artists’ perception of crowdfunding as a mechanism to support artistic production, and its empirical investigation broadens insights that inform academics, policy-makers and practitioners. The results of the discourse analysis therefore contribute to greater comprehending of how artists and creators perceive the CCCF phenomenon and practice. Focusing on narrative frames used in crowdfunding campaigns, we elaborated on Maehle et al. (Citation2021) original taxonomy and exemplified its wider applicability beyond sustainability projects. Moreover, we introduced a new frame – the sentiment – which is relevant when addressing the emotional appeals used in cultural-creative campaigns.

Particularly, we found that cultural campaigns mainly acclaim artistic production and financial acquisition as their goals; however, they also acknowledge other objectives. For example, societal contribution is quite relevant on the local platform, and some artists see the potential of using crowdfunding as a co-creation mechanism. The projects on the local platform also pay considerable attention to discussing their impact, both direct and indirect, on the different stakeholders. By emphasizing the intangible dimension of the culture sector, project creators focus on a broader notion of the role of arts and culture for society, the local community, and consumers. As for attributing the use of crowdfunding, the artists emphasize lack of finance (even in the case when public funding is given) and potential for product sales. From this perspective, the commercial aspect of crowdfunding is well documented; however, our findings confirm the artists’ perception of crowdfunding as a broader mechanism than just a monetary tool having the potential to bridge arts and commerce (Dalla Chiesa, Bucco, and Handke Citation2022).

Based on our findings, we suggest nine theoretical propositions that the future studies are invited to validate statistically in other settings. These propositions among other things suggest a framework for predicting the use of narrative frames based on the cultural sector affiliation and platform’s scope of operations (local vs. global). Despite its merits, this study has limitations. First, it focuses on the funded cultural-creative projects on only two platforms in one country. Although this case works with an entire sample of cultural crowdfunding campaigns due to Norway’s relatively small size and the dominance of the two selected platforms, future studies can extend the research to other national contexts to achieve higher generalizability. Second, the categorization of cultural productions is a subjective assessment, especially using Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circle model over platform tags. Platform tags are simplistic, as they do not cover the whole spectrum of the cultural production chain. Therefore, the current study did not focus on the detailed analysis of the data presented in Appendix A. By addressing the complexity and level of abstraction of different CCIs, Throsby’s (Citation2008) model offers more accurate insights into which CCIs are using crowdfunding and indicates the potential of CCCF to be applied in all types of CCIs given the right framing approach. Understanding the frames behind CCCF is the first step to broadening the potential of crowdfunding as a bridging channel alleviating the tension between arts and commerce. Future research is encouraged to further investigate the CCCF discourse from a social-artistic perspective, which will allow for raising of the market potential of crowdfunding and its inclusion in public policy, such as match funding mechanisms aiming to reach a sustainable ecosystem of funding for the culture sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alice Demattos Guimarães

Alice Demattos Guimarães is currently a PhD Research Fellow in Alternative finance as a responsible innovation within the culture sector, at Mohn Centre for Innovation and Regional Development, Western Norway of Applied Science (HVL). She is a PhD Candidate in the Programme Responsible Innovation and Regional Development (RESINNREG) at the same institution and her research is embedded in the CrowdCul Project. The purpose of her PhD research is to delve into the opportunities of co-creation of (diverse) values within cultural crowdfunding. She is a cultural(-urban) economist, graduated from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, and holds a master in Global Markets and Local Creativity, awarded with the Erasmus Mundus Masters Scholarship for the two-years international jointed degree granted by the University of Glasgow, University of Barcelona and the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has been working for more than five years as a researcher in the field of urban development correlated to the cultural sector, with focus on museums and performance arts. Her research interests are within culture economy, sociocultural practices, sustainable-solidary finance, creativity management, and decolonial theories.

Natalia Maehle

Natalia Maehle is a Professor at the Mohn Centre for Innovation and Regional Development, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL). Maehle holds a PhD from the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH). She is doing teaching and research in the field of cultural crowdfunding, digital innovation, sustainability, and marketing. Professor Maehle is involved in several international research projects and coordinates the research project ‘Crowdfunding in the Culture Sector: Adoption, Effects and Implications’. Maehle has an excellent track record of publications in the highly-ranked international peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Marketing, European Journal of Marketing, British Food Journal, European Planning Studies, Baltic Journal of Management, International Journal of Market Research and Journal of Consumer Behaviour.

Notes

1. The list of words goes on: ‘literature’, ‘novel’, ‘poem’, ‘music’, ‘CD’, ‘LP’, ‘concert’, ‘song’, ‘album’, ‘record’, ‘film’, ‘documentary’, ‘cartoon ‘, ‘comics’, ‘painting’, ‘picture’, ‘museum’, ‘gallery’, ‘exhibition’, ‘fashion’, ‘clothing’, ‘clothing design’, ‘design’, ‘library’, ‘photography’, ‘photographer’, ‘poster’, ‘theatre’, ‘performance’, ‘dance’, ‘opera’, ‘musical’, ‘show’, ‘game’, ‘podcast’, ‘radio’, ‘festival ‘, ‘circus’, ‘sculpture’, ‘TV’, ‘web series’. We acknowledge that this list is not exhaustive, but it includes the major representatives of the four groups in the Throsby’s (Citation2008) concentric circles model.

References

- Abbing, H. 2008. Why Are Artists Poor? The Exceptional Economy of the Arts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Agrawal, A., C. Catalini, and A. Goldfarb. 2014. “Some Simple Economics of Crowdfunding.” NBER Innovation Policy & the Economy 14 (1): 63–97. doi:10.1086/674021.

- Ahsan, M., E. F. Cornelis, and A. Baker. 2008. “Understanding Backers’ Interactions with Crowdfunding Campaigns: Co-Innovators or Consumers?”. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JRME-12-2016-0053/full/html

- Alexiou, K., J. Wiggins, and S. B. Preece. 2020. “Crowdfunding Acts as a Funding Substitute and a Legitimating Signal for Nonprofit Performing Arts Organizations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 49 (4): 827–848. doi:10.1177/0899764020908338.

- Anderson, K. B. 2016. “Let Me Tell You a Story: An Exploration of the Compliance-Gaining Effects of Narrative Identities in Online Crowdfunding Textual Appeals.” PhD diss., State University of New York at Buffalo.

- Bannerman, S. 2012. “Crowdfunding Culture.” Wi: Journal of Mobile Culture 6 (4): 1–23.

- Belleflamme, P., T. Lambert, and A. Schwienbacher. 2014. “Crowdfunding: Tapping the Right Crowd.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (5): 585–609. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.003.

- Bidra. 2021. About Bidra.no. https://bidra.no/

- Bille, T., and G. G. Schulze. 2006. “Culture in Urban and Regional Development.” In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. 2nd ed., edited by V. A. Ginsburgh and D. Throsby. Oxford: North-Holland Elsevier.

- Boeuf, B., J. Darveau, and R. Legoux. 2014. “Financing Creativity: Crowdfunding as a New Approach for Theatre Projects.” International Journal of Arts Management 16 (3): 33–48.

- Breznitz, S. M., and D. S. Noonan. 2020. “Crowdfunding in a Not-So-Flat World.” Journal of Economic Geography 20 (4): 1069–1092. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbaa008.

- Bürger, T., and S. Kleinert. 2021. “Crowdfunding Cultural and Commercial Entrepreneurs: An Empirical Study on Motivation in Distinct Backer Communities.” Small Business Economics 57 (2): 667–683. doi:10.1007/s11187-020-00419-8.

- Carè, R., A. Trotta, and A. Rizzello. 2018. “An Alternative Finance Approach for a More Sustainable Financial System.” In Designing a Sustainable Financial System: Development Goals and Socio-Ecological Responsibility, edited by T. Walker, S. D. Kibsey, and R. Crichton, 17–63. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chaney, D. 2019. “A Principal–Agent Perspective on Consumer Co-Production: Crowdfunding and the Redefinition of Consumer Power.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 141: 74–84. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.06.013.

- Chen, S., S. Thomas, and C. Kohli. 2016. “What Really Makes a Promotional Campaign Succeed on a Crowdfunding Platform? Guilt, Utilitarian Products, Emotional Messaging, and Fewer but Meaningful Rewards Drive Donations.” Journal of Advertising Research 56 (1): 81–94. doi:10.2501/JAR-2016-002.

- Colbert, F. 2012. “Financing the Arts: Some Issues for a Mature Market.” Megatrend Review 9 (1): 83–95.

- Dalla Chiesa, C., G. Bucco, and C. Handke. 2022. “Exploring Home-Bias and the Economic Features of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Crowdfunding Success.” Working paper based on the PhD dissertation Crowdfunding culture: Bridging Arts and Commerce (2021) by Carolina Dalla Chiesa.

- Dalla Chiesa, C., and E. Dekker. 2021. “Crowdfunding Artists: Beyond Match-Making on Platforms.” Socio-Economic Review 19 (4): 1265–1290. doi:10.1093/ser/mwab006.

- Gorbatai, A., and L. Nelson. 2015. “Gender and the Language of Crowdfunding.” Academy of Management Proceedings. https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/ambpp.2015.15785

- Granovetter, M. 1983. “The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited.” Sociological Theory 1: 201–233. doi:10.2307/202051.

- Haguette, T. M. F. 2001. Qualitative Methodologies in Sociology. São Paulo: Vozes.

- Handke, C., and C. Dalla Chiesa. 2021. “The Art of Crowdfunding Arts and Innovation: The Cultural Economic Perspective.” Journal of Cultural Economics 46 (2): 249–284. doi:10.1007/s10824-022-09444-9.

- Henningsen, E., L. Håkonsen, and K. Løyland. 2017. “From Institutions to Events–Structural Change in Norwegian Local Cultural Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 23 (3): 352–371. doi:10.1080/10286632.2015.1056174.

- Hesjedal, M. B., H. Åm, K. H. Sørensen, and R. Strand. 2020. “Transforming Scientists’ Understanding of Science–Society Relations. Stimulating Double-Loop Learning When Teaching RRI.” Science and Engineering Ethics 26 (3): 1633–1653. doi:10.1007/s11948-020-00208-2.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., and A. C. Pratt. 2005. “Cultural Industries and Cultural Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/10286630500067598.

- Hofstede, G. 2011. ”Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2 (1): 2307-0919. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/

- Josefy, M., T. J. Dean, L. S. Albert, and M. A. Fitza. 2017. “The Role of Community in Crowdfunding Success: Evidence on Cultural Attributes in Funding Campaigns to ‘Save the Local Theater’.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 41 (2): 161–2587. doi:10.1111/etap.12263.

- Kaartemo, V. 2017. “The Elements of a Successful Crowdfunding Campaign: A Systematic Literature Review of Crowdfunding Performance.” International Review of Entrepreneurship 15 (3): 291–318.

- Korsgaard, S., A. Anderson, and J. Gaddefors. 2016. “Entrepreneurship as Re-Sourcing: Towards a New Image of Entrepreneurship in a Time of Financial, Economic and Socio-Spatial Crisis.” Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 10 (2): 178–202. doi:10.1108/JEC-03-2014-0002.

- Kotler, P. T., and G. Armstrong. 2020. Principles of Marketing. 18th Global ed. London: Pearson Education.

- Lazzaro, E., and D. Noonan. 2020. “A Comparative Analysis of US and EU Regulatory Frameworks of Crowdfunding for the Cultural and Creative Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (5): 590–606. doi:10.1080/10286632.2020.1776270.

- Machado, A. F. 2016. “Cultural Economy and Creative Economy: Consensus and Dissensus.” In For a Creative Brazil: Meanings, Challenges, and Perspectives to a Brazilian Creative Economy, edited by A. F. Machado and C. Leitão, 53–62. Belo Horizonte: BDMG Cultural .

- Maehle, N., P. Piroschka Otte, B. Huijben, and J. de Vries. 2021. “Crowdfunding for Climate Change: Exploring the Use of Climate Frames by Environmental Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Cleaner Production 314: 128040. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128040.

- Majumdar, A., and I. Bose. 2018. “My Words for Your Pizza: An Analysis of Persuasive Narratives in Online Crowdfunding.” Information & Management 55 (6): 781–794. doi:10.1016/j.im.2018.03.007.

- Manzo, K. 2010. “Beyond Polar Bears? Re‐Envisioning Climate Change.” Meteorological Applications 17 (2): 196–208. doi:10.1002/met.193.

- Minutolo, M. C., C. Mills, J. Stakeley, and K. Marie Robertson. 2018. “The Creation of Social Impact Credits: Funding for Social Profit Organizations.” In Designing a Sustainable Financial System: Development Goals and Socio-Ecological Responsibility, edited by T. Walker, S. D. Kibsey, and R. Crichton, 239–261. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mitra, T., and E. Gilbert. 2014. “The Language That Gets People to Give: Phrases That Predict Success on Kickstarter.” In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. Baltimore.

- Mollick, E. R., and V. Kuppuswamy. 2016. After the Campaign: Outcomes of Crowdfunding. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Kenan-Flagler Research.

- Mollick, E., and R. Nanda. 2014. “Wisdom or Madness? Comparing Crowds with Expert Evaluation in Funding the Arts.” Management science 62 (6): 1533–1553. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2015.2207.

- Nahapiet, J., and S. Ghoshal. 1998. “Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage.” Academy of Management Review 23 (2): 242–266. doi:10.2307/259373.

- Nisbeth, M. C. 2009. “Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter for Public Engagement.” Environment, Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 51 (2): 12–23. doi:10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23.

- Nordgård, D. 2018. The Music Business and Digital Impacts: Innovations and Disruptions in the Music Industries. Cham: Springer.

- NViVo. 2019. What Is NVivo? https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/what-is-nvivo

- Ordanini, A., L. Miceli, M. Pizzetti, and A. Parasuraman. 2011. “Crowd-Funding: Transforming Customers into Investors Through Innovative Service Platforms.” Journal of Service Management 22 (4): 443–470. doi:10.1108/09564231111155079.

- Parhankangas, A., and M. Renko. 2017. “Linguistic Style and Crowdfunding Success Among Commercial and Social Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Business Venturing 32 (2): 215–236. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.11.001.

- Parsons, L. M. 2007. “The Impact of Financial Information and Voluntary Disclosures on Contributions to Not-For Profit Organizations.” Behavioral Research in Accounting 19 (1): 179–196. doi:10.2308/bria.2007.19.1.179.

- Peltoniemi, M. 2015. “Cultural Industries: Product–Market Characteristics, Management Challenges and Industry Dynamics.” International Journal of Management Reviews 17 (1): 41–68. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12036.

- Potts, J. 2016. The Economics of Creative Industries. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Quero, M. J., R. Ventura, and C. Kelleher. 2017. “Value-In-Context in Crowdfunding Ecosystems: How Context Frames Value Co-Creation.” Service Business 11 (2): 405–425. doi:10.1007/s11628-016-0314-5.

- Rhue, L., and L. P. Robert Jr. 2018. “Emotional Delivery in Pro-Social Crowdfunding Success.” In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3170427.3188534

- Røtnes, R., M. Tofteng, and M. Marie Frisell. 2021. For framtidens kultursektor. Oslo: Kulturrådet.

- Rushton, M. 2003. “Cultural Diversity and Public Funding of the Arts: A View from Cultural Economics.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 33 (2): 85–97. doi:10.1080/10632920309596568.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” The American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Rykkja, A., Z. Haque Munim, and L. Bonet. 2020b. “Varieties of Cultural Crowdfunding: The Relationship Between Cultural Production Types and Platform Choice.” Baltic Journal of Management 15 (2): 261–280. doi:10.1108/BJM-03-2019-0091.

- Rykkja, A., and A. Hauge. 2021. “Crowdfunding and Co-Creation of Value: The Case of the Fashion Brand Linjer.” In Culture, Creativity and Economy: Collaborative Practices, Value Creation and Spaces of Creativity, edited by B. J. Hracs, T. Brydges, T. Haisch, A. Hauge, J. Jansson, and J. Sjoholm, 43–55. London: Routledge.

- Rykkja, A., N. Mæhle, Z. H. Munim, and R. Shneor. 2020a. “Crowdfunding in the Cultural Industries.” In Advances in Crowdfunding: Research and Practice, edited by R. Shneor, L. Zhao, and B.-T. Flåten, 423–440. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Saldaña, J. 2015. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Scott, A. J. 2008. Social economy of the Metropolis: Cognitive-Cultural Capitalism and the Global Resurgence of Cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shenor, R., L. Zhao, and B.T. Flåten. 2020. “Introduction: From Fundamentals to Advance in Crowdfunding Research and Practice.” In Advances in Crowdfunding: Research and Practice, edited by R. Shneor, L. Zhao, and B.-T. Flåten, 1–18. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Shneor, R., and B.T. Flåten. 2015. “Opportunities for Entrepreneurial Development and Growth Through Online Communities, Collaboration, and Value Creating and Co-Creating Activities.” In Entrepreneurial Challenges in the 21st Century, edited by R. S. Shams, 178–199. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Shneor, R., and N. Mæhle. 2020. “Editorial: Advancing Crowdfunding Research: New Insights and Future Research Agenda.” Baltic Journal of Management 15 (2): 141–147. doi:10.1108/BJM-04-2020-420.

- Statistics Norway. 2021. ”Culture Statistics.” https://www.ssb.no/en

- Throsby, D. 2001. Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Throsby, D. 2008. “Modeling the Cultural Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 14 (3): 217–232. doi:10.1080/10286630802281772.

- Towse, R. 2020. “Creative Industries.” In Handbook of Cultural Economics. 3rd ed., edited by R. Towse and T. N. Hernánde, 137–144. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Toxopeus, H., and K. Maas. 2018. “Crowdfunding Sustainable Enterprises as a Form of Collective Action.” In Designing a Sustainable Financial System: Development Goals and Socio-Ecological Responsibility, edited by T. Walker, S. D. Kibsey, and R. Crichton, 263–287. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- UNESCO: United Nation Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2013. Creative Economy Report 2013: Widening Local Development Pathways. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

- Willfort, R., C. Weber, and O. Gajda. 2016. “The Crowdfunding Ecosystem: Benefits and Examples of Crowdfunding Initiatives.” In Open Tourism, edited by R. Egger, I. Gula, and D. Walcher, 405–412. Berlin: Springer.

- Ziegler, T., R. Shneor, K. Wenzlaff, B. Wang, J. Kim, F. F. C. Paes, K. Suresh, B. Z. Zhang, L. Mammadova, and N. Adams. 2021. The Global Alternative Finance Market Benchmarking Report. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/faculty-research/centres/alternative-finance/publications/the-global-alternative-finance-market-benchmarking-report/

- Ziegler, T., R. Shneor, and B. Z. Zhang. 2020. “The Global Status of the Crowdfunding Industry.” In Advances in Crowdfunding: Research and Practice, edited by R. Shneor, L. Zhao, and B.-T. Flåten. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Appendices Appendix A.

Summarized tables of scrapping data - successfully funded CCCF campaigns, per year according to Kickstarter’s categories for both Kickstarter and Bidra

Appendix B.

Examples of CCCF frames in the project descriptions

Appendix C.

Summarized tables of number of codes per frame and per year on projects’ descriptions on Kickstarter and Bidra