ABSTRACT

Of the variety of ways governments, organisations and artists are embedding art and culture within rural tourism strategy, public art trails have emerged as a popular form and approach. However, rural and remote local governments face challenges in realising possible benefits of arts tourism for their communities. This article takes remote northern Australia art tourism initiative, the Savannah Way Art Trail, as a case study to consider principles for successfully connecting public art trails with tourism in remote communities. Processes of delivering the Savannah Way Art Trail are framed and discussed under three themes: 1) local government capacity and relationships; 2) listening to locals; and 3) the ‘art’ of creating and managing remote art trails. These themes are considered as recommendations that can provide ways to enact cultural policy in practice in remote communities, and opportunities for extending the potential for art trails to reflect and benefit those communities.

Introduction

Art and culture offer a range of strategies and strengths for sustaining and developing rural and remote communities. Of these, cultural and art tourism present specific opportunities. For communities facing major environmental and social challenges and a decline in traditional industries such as manufacturing and agriculture, tourism strategies that leverage art, culture, history and heritage assets provide a path to adaptation, regeneration and resilience (see Anwar Mchenry Citation2009, 63; Campbell and Maclaren Citation2021, 88; Duxbury Citation2020, 5; S. M. Cunningham et al. Citation2019, 7; Qu and Zollet Citation2023). However, rural and remote destinations face challenges of distance, accessibility and attractiveness when targeting key tourist markets. For tourism diversification strategies to be successful, and provide the intended economic benefits to communities, the development of tourism experiences that draw tourists into the region and provide opportunities/activities to engage with local attractions, including art galleries, festivals and installations, are needed. This can be achieved through tourism themed routes or trails developed to attract the drive tourism market.

This article takes an art tourism initiative, the Savannah Way Art Trail, as a case study to explore principles and strategies for successfully connecting a public art trail with tourism opportunities in remote places. In doing so it draws out key considerations for cultural policy in practice on the ground in rural communities. Jointly funded through both arts and tourism portfolios of the Queensland state government, and five local governments, the Savannah Way Art Trail was delivered by the Central Queensland Regional Arts Services Network (housed within Central Queensland University) between 2020 and 2023. Noting the project’s explicit tourism agenda, the research component of the project explored how each participating remote local government envisaged the connection between public art and local tourism, as well as understanding principles for collaborating and engaging remote communities in the narrative of their art trail. Through the learnings of this project, this article identifies what is needed on the ground to best support the development of a community-informed art trail with potential tourism outcomes.

Art and tourism in non-metropolitan Australia

There is an expanding body of research demonstrating the important role of art and culture in supporting tourism outcomes in rural and regional communities (see Anwar Mchenry Citation2009; S. M. Cunningham et al. Citation2019; Rentschler et al. Citation2015), and a great deal of enthusiasm by governments for arts and cultural tourism to sustain or revitalise non-urban communities. In Australia, public art trails – particularly the silo art ‘movement’Footnote1 throughout rural areas – have increased in number and popularity over the past decade. The Local Government Association of Queensland frames silo art trails as ‘a winner for small communities’, emphasising place-branding, tourist attraction and economic outcomes (Green Citation2020, 240). In the mainstream media, silo art has been described as ‘a lifesaver’ for struggling rural towns because it ‘put[s] towns on the map’ and attracts new visitors (Kearney Citation2018). However, as Green (Citation2020) observes, the economic, social and cultural benefits of silo art to communities remain underexplored.

The opportunities and potential benefits of art tourism are not evenly distributed across geographies and require more analysis in the context of rural and remote communities with little existing hard or soft arts and cultural infrastructure. In Australia, these opportunities were further highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, where attention shifted to regional, rural and remote destinations as potential travel spots. In particular, the response from the tourism industry was to focus on the intrastate, domestic market, where sentiment for travel was strong amongst domestic tourists to return to travel in 2021 and 2022 (Flew and Kirkwood Citation2021). As post COVID-19 recovery continues with the reopening of international borders, destinations face increasing competition to maintain tourist visitation. The question of how to grow art tourism in rural and remote communities is a pertinent one for governments requiring creative solutions to the social and economic challenges faced by these communities.

Within Australia’s tripartite system of government, all three tiers position art, culture and tourism as allied sectors which contribute importantly to national and local economies, and the sustainability of metropolitan and non-metropolitan communities. New federal arts policy, Revive: a place for every story, a story for every place – Australia’s cultural policy for the next five years, identifies increased visitation to the country’s regions as an important role and function of art and culture (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2023b, 41), while the Australian Trade and Investment Commission notes the visitor economy plays a critical role in supporting the national arts and cultural sector (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2023a, 6). Departmental structuring within the federal government also makes a link between art, culture, tourism and regional development goals, with the Office for the Arts included in federal super-department, the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, suggesting arts and culture are valued for their contribution to regional and economic development. Such alignment is reflected internationally. While not the only way governments value the arts, economic development is a values-oriented theme espoused by many national cultural agencies globally (in 40 percent of the 92 national cultural agencies studied – see Foreman-Wernet Citation2020, 7).

Prior to COVID-19, international art tourism was growing strongly as a significant form of tourism in Australia (Franklin Citation2018, 401), and particularly throughout regional Australia (Australia Council for the Arts Citation2018, 24). Research by peak federal body Creative AustraliaFootnote2 notes ‘[i]nternational visitors who engage with the arts are already more likely to go beyond the east coast states [and capital city areas] and to visit regional locations’ (Australia Council for the Arts Citation2018, 24). The Domestic Arts Tourism research report also highlights the growing significance of arts tourism to regional Australia, finding that although ‘[m]ajor cities account for the largest volume of arts tourism’, ‘the destinations where [domestic] tourists are especially likely to engage with the arts are in regional Australia’ (Australia Council for the Arts Citation2020b, 20), thus highlighting art tourism as an important growth area for Australia’s rural, regional and remote towns and cities.

COVID-19 has sharpened the alignment between art, culture and tourism in Australia’s regions as federal, state and local governments seek to support the regional arts sector and stimulate much-needed economic activity in non-metropolitan communities. Tourism and the arts, culture and entertainment sectors have been amongst the industries most severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant international and domestic border closures (Pennington and Eltham Citation2021). The Australian federal government, all state and territory governments, and many local governments responded through a range of targeted stimulus programs and funding boosts, a suite of which have positioned arts and cultural tourism as a path to recovery for both sectors as well as rural, regional and remote communities. For example, in late 2021 the Australian Government announced a one-off A$5 million Cultural Tourism Accelerator Program to ‘enable arts organisations to promote and develop cultural events for tourists across regional Australia’ and ‘increase tourism visitation in regional, rural and remote communities across Australia by providing financial support for arts and cultural activity’ (Flying Arts Alliance Citation2021). The Savannah Way Art Trail discussed in this paper emerged within this context.

Of the variety of ways governments, organisations and artists are embedding art and culture within rural tourism strategy, public art trails represent a distinct form and approach. Public art can be defined broadly as artworks that are either permanent or temporary, which are commissioned for accessible locations outside of settings such as museums, studios and galleries (Zebracki Citation2013, 303). Public art offers ‘a way of providing art experiences for the wider public in a way that is usually both free and accessible’ (Ellison and Thompson Citation2020, 246), while trails organise the works along a purposive route (du Cros and Jolliffe Citation2017, 537; Hayes and MacLeod Citation2006, 48). For rural and remote locations with very limited cultural infrastructure – such as dedicated gallery spaces – forms of public art such as outdoor sculptures and large-scale murals are popular as a way of expanding a community’s artistic offerings for local residents as well as visitors (Ellison and Mackay Citation2023). Planning, presenting or ‘packaging’ such works as a trail offers a means of connecting geographically dispersed places, and encouraging visitors to stop in small towns they might otherwise drive through.

According to Malor (Citation2003, 1) ‘regional public art functions in a markedly different manner to that in large cities’. The agendas driving rural and regional public art trails are often concerned with ‘whole of site’ development and strengthening, and not only the development of a tourist trail (Malor Citation2003, 5). In rural Australia, large-scale murals painted on disused grain silos and water tanks are becoming an iconic feature in a growing number of towns and regions.

The enthusiasm for silo art and trails is evidenced by the increasing number of towns being added to the Australian Silo Art Trail Map (see https://www.australiansiloarttrail.com/). Research suggests silo art has had significant tourism impact in isolated rural communities, supported local communities to reimagine place identity, and rejuvenate disused spaces (see Gunn Citation2020; Tsakonas Citation2019). However, there are of course many questions to be asked about how well public art can reasonably boost rural and remote economies, and under what conditions. Seeing the potential benefits of public art – and art trails – for rural communities, governments, communities and arts organisations are eager to replicate perceived successes. While large-scale public art may be effective in some regional locations, the remote context presents challenges such as greater distances between towns and less supporting infrastructure like cafes and other attractions.

Methodology and research context

Taking the Savannah Way Art Trail as a case study, the research considers how remote communities may be better supported – or what is needed – to make a public art trail a success in remote places. There is an increased call within governments and cultural policy research to ‘listen to locals’ (Duxbury Citation2020, 10), and understand how they perceive the value and function of arts and culture in their own communities (see Crespi-Vallbona and Mascarilla-Miró Citation2020, 426; Røyseng Citation2022, 581). Attention to local contexts and concerns supports more appropriate, relevant policymaking and the delivery of arts and cultural products and experiences with potential for long-term benefits for communities. In the context of this research, we argue that exploring remote local governments’ and residents’ aspirations for public art in their communities, and studying the processes, principles and practicalities of remote public art, are crucial for expanding the potential for public art to sustain and grow those economies and communities.

In rural and remote Australia, opportunities exist for arts and culture to represent and continue the rich cultures and stories of First Nations peoples, for the benefit of locals and visitors, and support a range of economic, social and cultural outcomes through increased tourism; however, small rural towns and underserved remote communities face a range of challenges in realising the possible benefits of arts tourism in their unique locations. In this article, we examine the challenges and opportunities of public art trails as a distinct approach to remote art tourism, through a case study of one public art trail implemented in remote northern Australia, the Savannah Way Art Trail.

The research received ethical clearance through Central Queensland University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 0000023217). The team undertook a qualitative methodology, informed by autoethnographic frameworks and using a case study approach. Our data collection process involved: semi-structured interviews conducted with the Mayors and tourism and community development staff of the five rural local governments (representing the six towns) that invested in the project. This data was further enriched through surveys completed by council staff unavailable for interviews and adult community members who attended consultation workshops, as well as participant observation and reflective journaling of the project team.

It is important to note the limitations of this project. Firstly, the number of participants across all forms of data collection were 52. This low number is, comparatively, a high participation rate from those engaged in the project from these six remote locations. However, this does limit the ability to segment these participants for analysis in this article as it will be identifiable. Secondly, the identifiable and recognisable nature of roles and communities in these small towns means we have considered the Savannah Way Art Trail as an individualised case study rather than six individual sites. Thirdly, we as the authors of this paper were embedded within this project.Footnote3 This lived experience was, ultimately, crucial to the delivery of the project for the communities and the funding partner, and we acknowledge the ethnographic nature of our role within this project as included through the data collection and subsequent analysis. As a case study, the Savannah Way Art Trail provides opportunity to investigate how policy visions for art tourism may be supported on the ground in remote communities. In this case, local and state government tourism strategies informed components of the research design and project delivery. Reflective of their remote context, tourism strategies within the participating local governments tended to be implicit – amounting mainly to intentions to increase visitation and overnight stays – as opposed to the explicit, multi-departmental strategising and planning at the level of state government.

Drawing on our experience as researchers and arts professionals involved in the coordination, management and research components of the Savannah Way Art Trail, the next section describes key themes which emerged as considerations within the project: 1) the importance of identifying, connecting to, and brokering relationships with local government; 2) listening to locals, while obvious, remains paramount; and 3) there is an ‘art’ to developing, creating, and managing public art trails. While the project is specific and locally unique, these recommendations are likely to be transferable and applicable for other art tourism projects in remote communities. The Savannah Way Art Trail subsequently offers a rich case for drawing out policy-relevant considerations for extending the potential for art tourism in remote communities.

Case study: the Savannah Way art Trail

Background

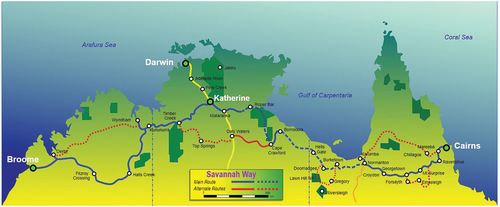

The Gulf Savannah region of North Queensland reaches west from the Atherton Tablelands to the Northern Territory border – a driving distance of approximately 1,000 km (see ). The Savannah Way Art Trail comprises six site-specific, corten steel sculptures in the towns of Georgetown, Croydon, Karumba, Normanton, Burketown and Doomadgee. This part of the trail is all situated within Queensland, which is the most decentralised Australian state and covers a land area of over 173 million hectares − 2.5 times larger than the US state of Texas.

Figure 1. The Savannah Way reaches across three states in northern Australia. The Savannah Way Art Trail is part of the Queensland (eastern) section from Georgetown to Doomadgee. Image by summerdrought - own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Savannah_Way_0216.svg.

Earlier research has noted the importance of differentiating between regional, rural and remote communities and geographies, citing the problematic use of the term ‘regional arts’ in Australia, which ‘is used as a catch-all for vastly different activities and areas, from large prosperous regional centres to isolated remote townships’ (Hancox et al. Citation2020, 162). This can mean the realities, potentials and needs of very remote and peripheral communities are not reflected or addressed in regional arts policy and funding. There are no formal or consistent definitions of regional, rural and remote in Australia; however the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Remoteness Structure (Citation2023) is useful as it measures relative geographic remoteness based on distance from major cities, population density, and access to major cities. The six towns that participated in the Savannah Way Art Trail project are classified as Very Remote according to the ABS, denoting a population density of fewer than one person per hectare, geographic remoteness from large towns and capital cities, and low access to major facilities and services.

These six towns have populations of First Nations peoples well above the national average of 3.2 per cent. For instance, 89.3 per cent of the population of Doomadgee identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021a). In Croydon, 28.6 percent of the population identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021b). The entire Gulf Savannah region ranks in the lowest two quintiles of the Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage, which indicates a relatively disadvantaged population in terms of ‘people’s access to material and social resources, and their ability to participate in society’ (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2018, 6). Beef cattle production, fishing, and local government are major industries of employment across the region, and it is growing an active tourism industry.

The Savannah Way is marked as one of Australia’s major drive tourism routes, taking drive tourists 3,700 km across northern Australia to explore a range of natural, geological, adventure, community and cultural experiences that comprise the outback. The drive route attracts between 40,000 and 60,000 visitors each year (Gulf Savannah Development Inc Citation2018) However, it is difficult to obtain precise and up to date visitation data for this region.As noted by economic development agency Gulf Savannah Development Inc (Citation2018), reports by Tourism Research Australia (TRA) do not drill down to provide Gulf region-specific data. Further, Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) accommodation data does not encompass the majority of accommodation businesses operating in the region (Gulf Savannah Development Inc Citation2018, 5). It has been reported that the Queensland-based Gulf Savannah route, which is the focus of this research, is one of Queensland’s most popular drive tourism routes (Queensland Government Citation2023a), and discussions with industry stakeholders suggest that the drive route experienced increased visitation during COVID-19, but this has since declined.

Nonetheless, interviews undertaken for this research, in addition to local government and industry reports reviewed, reveal the importance of tourism for the region and local government’s desire to further develop and grow this industry. For instance, Gulf Savannah Development estimated the value of tourism to the region as AU$69.8 m in 2017, excluding air services. Prolonged international border closures have inspired an increased focus to encourage domestic tourism – that is, travel through Australia by Australians (Cunningham et al. Citation2021, 775). Even prior to COVID-19, the domestic drive tourism market has been the main tourism market for the Gulf Savannah region and the envisioned market for the Savannah Way Art Trail. The Trail seeks to complement the experiences along the Savannah Way for drive tourists. Mirroring enthusiasm for silo art, the mainstream media has emphasised the potential tourism outcomes of the Savannah Way Art Trail, saying it will ‘boost drive tourism … and increase visitation’ across the region (Gall Citation2022). However, it is also important to consider the Art Trail’s role in and representation of local communities.

The Savannah Way Art Trail represents a cross-government, cross-department collaboration between the state agency for arts and culture, Arts Queensland, and state-wide tourism initiative the Year of Outback Tourism. Additionally, the project received funding through national and state disaster recovery funding arrangements (The Monsoon Trough Fund), and from four participating Local Government Authorities through the Regional Arts Development Fund. Funding collaborations between arts and culture and tourism are not unique in Australia, and in Queensland the Regional Arts Development Fund represents a sustained and productive collaboration between state and local government to support arts and cultural development in non-metropolitan communities. The objectives for the project brought together by the two funding arms – arts and tourism – are complementary, though also very ambitious which provokes some discussion about how to align and realise these objectives ‘on the ground’ in remote communities.

The Year of Outback Tourism’s objectives for the project, described in the contract agreement, included: ‘Each permanent installation will be themed on Queensland’s Great Outback, aiming to attract more tourists to the region and enhance the visitor experience, while building the skills and capacity of local artists through mentoring and connection’. The stated expected outcomes included ‘encourage community participation and engagement; promote social, cultural or economic benefit to the community; enhance the profile of Georgetown, Croydon, Normanton, Karumba, Burketown, Doomadgee … [and] generate a media profile of the initiative in the lead up to, and during, the Initiative’. These themes were also included in the Arts Queensland contract which indicated an ambitiously large list of intentions for the project: increased collaboration between local governments and the arts, cultural and creative sector; consultation with and active participation from/by First Nations artists and communities; increases to cultural tourism in the Far North Queensland [FNQ] region; sharing and strengthening of culture and stories unique to FNQ; strengthening community pride and sense of place. These objectives lend to each of the themes explored in this article.

The Savannah Way Art Trail project initially commenced in late 2019, led by Arts Queensland. The original proposal was for a silo- or mural-based art trail. However, Arts Queensland’s early consultation process revealed that local communities were concerned about the longevity of the murals and the lack of grain silos or other large, suitable surfaces for the murals. The idea for a sculpture trail that explored the thematic, iconic and cultural considerations of each town emerged from these early consultations. COVID-19 delayed the start of the project until late 2020 when, following an invited tender process, the Central Queensland Regional Arts Services Network (CQRASN) was awarded the contract to deliver the project through 2021–2022. The processes of delivering the project, the ensuing challenges and tensions, are next framed and discussed under the three themes. These themes represent important learning experiences from this project and point to critical opportunities for supporting public art trails in remote communities, in ways that reflect and benefit those communities.

Theme 1: local government capacity and relationships

As a collaborative project, the Savannah Way Art Trail was enabled and inevitably shaped by the relationships between state government and the five local government authorities (representing the six towns) involved in this project. Part of the role of CQRASN was to mediate tensions that emerged as multiple state government, local government, and community agendas intersected through the project. The CQRASN team – comprising a project manager, regional arts officers, First Nations cultural consultants, and researchers from Central Queensland University – established a project steering committee involving representatives from the state government through Arts Queensland and each participating local government. This group facilitated an Expression Of Interest (EOI) process for a Queensland-based artist to work from a community consultative model across all communities to design, develop, fabricate, and install six works of public art. An open competition model was used in accordance with Australia’s National Association of Visual Artists’ (NAVA) best practice guidelines for publicly funded projects. The EOI process required submission of initial concept designs for the six sculptures, a budget, and community engagement plan. As part of this process applicants were provided with a summary report from Arts Queensland’s 2019 consultation which noted various themes, histories, stories and iconographies that local governments, tourism operators and Traditional Owner groups wanted depicted in their town’s sculpture. The CQRASN team and steering committee engaged in a rigorous assessment and scoring process which illuminated differing perceptions of what constituted a worthwhile investment of state and local government funds, and what proposed works were suitable for each of the six communities. These tensions reflect different priorities for the project and different perceptions of art.

While Arts Queensland steering committee members assessed EOIs based on artistic ‘excellence’ (as reflects traditional assessment criteria for securing funding), local governments were more concerned with which artist’s concept designs demonstrated an understanding of their community, its identity, and had capacity to ‘add value’ to local businesses and individuals. While the concept of artistic excellence is subjective and contested, it is noteworthy that state government steering committee members assessed the EOIs from ‘inside’ the discipline of arts and culture. The majority of the participating remote local governments, however, were too small and under-resourced to have a dedicated office or staff for arts and culture, and none had an arts and cultural strategy. For local governments, this project fit within the tourism portfolio and steering committee representatives included tourism and marketing directors, economic development managers, and community development coordinators. These stakeholders therefore spoke from ‘outside’ the arts and culture discipline and represented localised community concerns and interests which often seemed at odds with Arts Queensland’s specific, big-picture interest in state government investment in arts and culture. This tension resonates with Røyseng’s (Citation2022) discussion of ‘boundary struggles’ in public art projects, where the appropriateness of the art in-situ is evaluated differently by art experts and non-experts. As Røyseng describes, art is given meaning by different publics based on their differing cultural resources – and, we would add, different knowledges of communities and their needs. This leads to struggles over the value and relevance of specific works (Røyseng Citation2022, 591). The short-term outcome of this tension for the Savannah Way Art Trail was that the steering committee was challenged to appoint one artist to complete all six works, and some local government stakeholders felt their voices and visions were overshadowed by Arts Queensland.

A related challenge was the rolling personnel within the local governments which meant stakeholders involved in Arts Queensland’s 2019 consultation had moved on by the time CQRASN took leadership of the project in 2021. Several local government stakeholders therefore stepped into the project with no knowledge of its long gestation. For some, the themes and stories identified in the 2019 consultations were outdated by 2021 and did not reflect the community story or local identity they wanted to promote. Such tensions and ‘boundary struggles’ are inevitable in public art projects which involve multiple stakeholders and their diverse agendas and expertise; however, considering how such challenges manifest in rural and remote contexts usefully helps identify what is needed to support ventures such as art trails for the benefit of communities.

These challenges relate to the capacity of remote local governments to embed arts and culture in their overall planning and strategy for communities. Strategies emerging from this case study are therefore to advocate for the distinct role of local government in local arts and cultural sectors, and relatedly to further empower and equip them to envision, plan and strategise the arts and cultural future of their communities. In Australia’s rural and remote communities, local governments are a critical resource and player in local arts and cultural sectors. Local governments enact national cultural policy at the local level and provide independent, responsive policies and initiatives that grow local arts and cultural sectors (Johanson, Kershaw, and Glow Citation2014, 218; S. Cunningham et al. Citation2021, 772–773). In the remote Gulf Savannah communities, for instance, the vast majority of arts and cultural services – including workshops, activities, festivals, productions, exhibitions and other opportunities for arts engagement and participation – are those organised and resourced by local government. Rather than entities which sit alongside local arts and cultural sectors, local governments are an integral part of the sector and a critical resource and collaborator for strengthening national arts and cultural capacity. There is as such a great need to build local government capacity to play a leadership role in arts and cultural decision-making and service delivery.

Ideally, this could be done through supporting all local governments to devise a locally-relevant arts and cultural plan, and through funding dedicated arts and cultural officers, even in remote and small councils. This would support local governments to bridge the distance between strategic visioning and operationalising arts and cultural initiatives such as the Savannah Way Art Trail. It may also help in shoring-up workforce mobility, which is also important. In cases where it is not possible for local governments to develop their own local arts and cultural plans the third party ‘broker’ such as CQRASN is important and useful in operationalising projects.

Of course, genuine engagement with local government is crucial so that their voices are heard. The Savannah Way Art Trail project was ‘top down’ from state government – both in terms of the project’s conception and also reflecting the balance of financial investment – which is not ideal in projects that want to prioritise community engagement, and seek to be responsive to community-identified interests and needs. As such, there was a clear perceived ‘gap’ between Arts Queensland’s and local government’s understandings of the project’s value, and this meant a process of translation and mediation was required to make the project suitable and successful from the perspectives of all involved. Advocating to Arts Queensland for the distinctive role of local government in enacting national cultural policy and state strategic arts plans at the local level, and providing independent, locally relevant policies and initiatives, was therefore an important role fulfilled by CQRASN. Importantly, this had to happen in an organisational context because of the inevitability of changing personnel across institutions during this time.

Theme 2: listening to locals

Public art is recognised as one of the most contested forms of art and many projects globally have shown the problem of artists external to the community being ‘parachuted’ in, and the ‘plop-art’ that results, having little significance or relationship to place and community (see Anwar-McHenry et al. Citation2018, 241; Cartiere and Guindon Citation2018, 85). Since public art exists in public spaces and is supported by public funds, there can be a tendency to privilege local government, artists’, and funding bodies understandings of art and of place in such projects. However, there is also increasing recognition in cultural policy research for ‘knowledge regarding how “ordinary people” understand and evaluate art’ (Røyseng Citation2022, 581), and of the critical role of local residents in determining the overall success of creative projects. Cartier and Guindon (Citation2018, 85) demonstrate the importance of meaningful community engagement, arguing that ‘one cannot create a site-specific work without taking the time to understand that site (its history, people, and so on): one cannot produce effective social practice without an engaged audience’. Anwar-McHenry et al. (Citation2018, 241) also say ‘it is the locally-generated constructions of place that have the potential to connect in real and meaningful ways with audiences’. Such views are reflected in the Australian Research Council-funded Creative Hotspots project, which found that cultural soft and hard infrastructure must be ‘owned’ locally (appreciated, engaged with, supported) before it can be successfully embedded within tourism strategy (S. M. Cunningham et al. Citation2019, 19). This speaks to the importance of collaborating with communities and involving them as partners and stakeholders in the design of a public art trail.

In the Savannah Way Art Trail project, initial sculpture designs based on Arts Queensland’s early consultation were presented to Council stakeholders (and met with varying degrees of dismay, outrage, ambivalence, pride and satisfaction). The 2019 consultation documentation revealed that Arts Queensland’s consultation had focused on ‘official’ community voices, such as local government representatives, tourism operators and community leaders, rather than seek to engage the full diversity and complexity of community voices. This likely exacerbated feelings the 2019 consultation was outdated or inadequate, and CQRASN’s project team therefore sought to engage a greater diversity of community representatives – including Council staff but also professional and hobbyist artists and local craft groups, and other adult residents. CQRASN’s community consultations in each project site were designed to introduce the idea of public art, learn what local residents viewed as unique about their community and what they wanted to communicate through the art, and use this information to refine or redesign the proposed sculptures. This process revealed that, at times, local residents’ understandings and appreciations of place and community differed from local governments’, and revealed new functions the project had to fulfil in order to appropriately acknowledge and represent community stories, and be accepted and valued by its members. This highlights the value of bringing together a cross-section of community to contribute to decision-making – a point also espoused by Gattenhof et al. (Citation2021, 47).

Differences between local government and residents’ visions emerged in several project sites and inspired changes to the sculpture concept designs. In the town of Normanton, for example, the original proposal from local government was for a bronze bull which would reflect the region’s thriving beef industry. However, consultation workshops with residents revealed participants felt the beef industry was well represented through other means, and they expressed a strong desire to acknowledge First Nations peoples’ stories and experiences of life in Normanton. During the workshops, First Nations participants related memories of living on an Aboriginal mission outside of Normanton, and told stories of harvesting native waterlilies and birds for bushtucker. The artist created a new concept design for the sculpture which was approved by local government who appreciated the importance of acknowledging community voices. As an interviewee described, the sculpture had a dual function to appeal to tourists, but it was critical to first and foremost appeal to locals:

It is great for tourism and tourist season, but it is really important for locals to be involved in it, because they really take pride in that sort of stuff. What we find is, especially in communities like ours, if you really get the community involved, and they feel like we’re [local government] hearing what they’re saying, and taking notice, they really take pride in these projects … if they take pride and they’re invested in something, it is generally here for a lot longer. And it is really well looked after. (R009)

The sculpture designed, fabricated and installed in Normanton depicts the native Carpentaria waterlily and magpie geese (see ). For First Nations community members, the sculpture represents ‘a good start to beautify the town but also to start showcasing culture which is missing in Normanton’ (R010).

Figure 2. Carpentaria lily wetlands – corten steel sculpture by Manning Daly Art, situated on the main street of Normanton. Photograph by Philip Vids.

Similar experiences were reflected in the community of Doomadgee where local government stakeholders recognised the criticality of hearing and reflecting community members’ voices and stories. Doomadgee’s population comprises 89.9 per cent Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples and, according to ABS data, this remote community is the eighth most disadvantaged local government area in Australia. The exclusion of First Nations voices persists in decision-making and knowledge construction in many settler-colonial countries including Australia, heightening the need for meaningful community consultation and inclusion of local voices in the sculpture design and decision-making processes.

The project’s key contact from Doomadgee Aboriginal Shire Council went to significant lengths to ensure the CQRASN team’s project consultations engaged and included local Elders and Traditional Owner Groups, working between Council and community to mediate tensions and ensure the project was locally appropriate and impactful. Guided by the project’s key contact, CQRASN consulted with councillors, local government staff and local artists through face-to-face meetings and walking tours on Country, and via telephone. These conversations highlighted that, beyond consultation, the community of Doomadgee needed to be included as participants in the creation of the sculpture. This was not only culturally appropriate, but significant for fostering local ownership and pride. An interviewee stated:

Doomadgee is a very very hard place and they need to know that it’s theirs. And the only way they know that it’s theirs is if they have something to do with this artwork. … That is important for this place, for the kids to see that ‘hey Aunty did that’, or ‘that’s Uncle’s work there’, so then it is theirs and they are likely to respect it. But having a white person’s piece of artwork that probably doesn’t look like the fish that they know probably won’t mean much to these kids. But if they have artwork there that their people have put into it, that’s a whole different ballgame. (R002)

Subsequently, CQRASN contracted local Waanyi artist Kelly Barclay to create surface designs for the Doomadgee sculpture, and the lead artists integrated these designs into the work. For local First Nations artists, involvement in the sculpture design was a professional development opportunity and resulted in a great deal of personal pride. An interviewee stated that it provided opportunity to tell their grandmother’s story:

I was really happy. It told the story, and Nan was very happy – she was in tears, so proud of it all … If someone from out of town comes to see the sculpture and wants to know the back story of it, I’d be willing to share that. I’m proud of my Nan and the story she told is inspiring

The importance of ‘listening to locals’ through ensuring projects acknowledge their distinct understandings of place and respond to locally specific needs is recognised by artsworkers, organisations, and by rural and remote local governments. However, much research and experience indicates that adequate and appropriate consultation and engagement is a process that takes time and is rarely built into project budgets. Two recent research projects conducted for Creative Australia emphasise the need to invest in relationship-building with communities to ensure locally-relevant and impactful arts and cultural program design and delivery. This is particularly important for First Nations communities. The research notes ‘engagement, acceptance and interest from First Nations community participants is seen as central to being able to deliver into remote and less centralised spaces’ (Australia Council for the Arts Citation2020a, 61) – a point further emphasised by Gattenhof et al. (Citation2022, 71) who note the need to invest in long-term community engagement and relationship building. For First Nations peoples, ‘[s]trong relationships with communities, trust, and supporting communities to shape and have ownership over the artistic works which represent their stories and languages, are integral to artmaking processes supporting cultural wellbeing’ (Gattenhof et al. Citation2022, 71). The Savannah Way Art Trail underscores the value of relationship-building to support the development and delivery of arts and cultural products that are locally relevant and beneficial to community members.

The policy-relevant strategy emerging through this theme is to invest in genuine relationship-building with communities, noting the need for bespoke and tailored approaches to engagement and inclusion to suit the specific needs, strengths and capacities of communities. As emerged through the Savannah Way Art Trail, appropriate community engagement can mean something different to different communities. For instance, in Normanton, community members appreciated inclusion through consultation processes, while the Doomadgee community was adamant that community buy-in required hands-on artistic input by artists known and respected by community-members. The Savannah Way Art Trail project is not presented here as an exemplar in community engagement – indeed, many of the project processes and desired outcomes were determined and incorporated into the contracting before the project team engaged with residents of communities. However, the project was agile enough to allow CQRASN to respond to the particular needs of community members. A recommendation emerging through this project is therefore to allow time and budget for relationship-building, and some flexibility in process to allow community needs to evolve and change during a project’s lifetime.

Theme 3: the art of trails

The idea for a public art trail through the Gulf Savannah region was pre-determined by Arts Queensland, likely due to the state government’s current tourism priorities. Arts Queensland has also recently invested in the state-wide Queensland Music Trails which explicitly aim to bolster tourism to rural and regional parts of the state (Queensland Government Citation2023b). The aims and marketing around such initiatives are largely externally-facing with rural communities assumed to benefit from economic outcomes produced by increased visitation. The Savannah Way Art Trail provided opportunity to explore how an art trail can have other benefits for rural and remote communities, in addition to tourism and economic outcomes, and to consider how such benefits can be built into future projects from the outset.

Interviews with remote local governments revealed these stakeholders had a range of reasons for investing in the Savannah Way Art Trail, beyond the tourism agenda emphasised by state government. These reasons can be categorised as: increased collaboration and cooperation between remote local governments; a symbol of cultural investment for the area; and refinement and articulation of place identity. Some of the participating local governments are extremely small, and for these interviewees, ‘connecting’ the region and ‘linking’ towns with each other was an important impetus for participating in the Savannah Way Art Trail project, and an anticipated outcome. The local government of Georgetown, for instance, views arts and cultural activities as avenues for their geographically dispersed community to interact, and for strengthening a sense of community and belonging between people. Georgetown interviewees described the significance of the Trail for becoming ‘part of a regional approach to the promotion of what this wonderful part of the North and northwest of Queensland’ (R012), and for becoming a ‘link in the chain’ (R022). According to an interviewee, ‘we need a sense of community and feeling throughout the country [local government area] and this would be a step in the right direction’ (R022). A Burketown interviewee similarly expressed ‘these sort of projects gives us opportunity to show our differences but how aligned we are as well … Each of the communities is certainly different but, somewhat alike’ (R014), suggesting participation in the Art Trail helped define and express a whole-of-region narrative. The idea that the Art Trail was a means of connecting the local governments through the Gulf Savannah emerged in Croydon, too, where an interviewee said ‘it would be nice if we could use it as a mechanism for all the councils to work together’ (R004).

For some participating local governments, the Savannah Way Art Trail was a symbol of cultural investment and of a maturing tourism industry. Doomadgee, for instance, is an isolated Aboriginal community that is actively striving to build its tourism industry. An interviewee described:

We get the tourists come in now and buy goods but they don’t hang around – they usually get their stuff and move on. What we’re trying to do here now is actually get that tourist to stay and know that they’re welcome. And I think the art trail is one way of saying to the tourist ‘you can stop here’. (R002)

Other interviewees made a similarly firm connection between art and tourism. In Croydon, the project was embedded as part of broader local government intentions in enhancing local arts and culture and shaping sophisticated tourism offerings. The sculpture was seen as ‘an element of where we are going with tourism … to me, sculptures always seems to fit within that whole cultural and heritage approach’ (R004). In communities such as Croydon with very little existing arts infrastructure, and no formal gallery space, a public art project like this appeared to mark a significant step in growing local arts and cultural offerings.

Local governments recognised the value of arts events and cultural and heritage infrastructure for providing opportunities for rural communities to market their uniqueness (Rentschler et al. Citation2015, 9) and promote place identity (S. M. Cunningham et al. Citation2019, 8). In Georgetown, an interviewee noted the relationship between art and tourism and suggested it was of particular interest to the specific demographic that travelled along the Savannah Way (R012). This interviewee also suggested the sculpture helped their region ‘update’ their image beyond its focus on the beef industry and ‘highlights the fact that we are a region rich in attractions’ (R012) – such as art and culture. Speaking of how the Trail in its entirety might support tourism and further economic development across the Gulf Savannah region, another interviewee said:

I guess that’s what the art trail is pointing towards – to have that kind of public art just makes the destination so much more mature. It opens up conversations; it tells stories and represents iconic things in the region. So hopefully those things can be levers to put a coffee shop in next to the art piece – those kinds of drivers. (R001)

This comment highlights the fact that enhancing tourism through the Gulf Savannah requires further infrastructure – such as more accommodation and cafes or eateries.

These perspectives from the Savannah Way Art Trail’s local government stakeholders highlight a number of ways that art trails may represent value to remote local governments, and which can be strategically built into future projects undertaken in remote areas. The interviews also highlighted several important considerations for future projects. For instance, it was clear across many interviews that, for local governments, the Savannah Way Art Trail represents ‘a step in the right direction’, a ‘lever’ and strategy towards realising future outcomes. ‘Success’, then, is partially hinged on the trail’s sustainability and longevity. du Cros and Jolliffe (Citation2017) identify three success factors which ensure the ongoing maintenance and use of sculpture trails. These are: ‘the arts/leisure experience; linkage to existing walking trails or recreational areas; and strong partnerships with enthusiastic stakeholders, particularly visionary arts administrators, civic authorities and well respected sculptors’ (du Cros and Jolliffe Citation2017, 542). These factors have salience for the Savannah Way Art Trail, which utilises an existing drive tourism route and partners with multiple stakeholders invested in its success. However, the remote context requires additional aspects and strategies for ensuring the trail is sustainable, including: consideration of supporting infrastructure such as cafes and accommodation; ownership and ongoing maintenance requirements for public art that can be managed by those outside of the arts sector; and the need for an overarching body to manage and maintain the trail given the fluctuating and uncertain capacity of local governments.

The scale of the Savannah Way Art Trail and its spread across many local government authorities meant maintenance of the sculptures and marketing of the trail is a collective responsibility. However, as mentioned previously, the significant workforce mobility of remote local governments, and the potential fluctuating values and budgets ascribed to local arts and culture, means such projects run the risk of being abandoned before their potential is fully realised. One way the CQRASN team and Arts Queensland has sought to mitigate such risks in the Savannah Way Art Trail project is by assigning management of the Art Trail to an external organisation, Topology, the local Regional Arts Services Network provider for the region. The long-term success of this project and how it may evolve under Topology’s management remains to be seen.

Conclusions and future directions

The Savannah Way Art Trail represents a significant financial investment from state government, and both financial and in-kind contributions from local governments. The project faced numerous challenges, including many that were outside the control of the teams involved. For instance, travel through parts of the Gulf region are regularly impacted by inclement weather – two itineraries had to be changed because of rain cutting off road access. The remoteness of the locations brings access requirements not present in other projects of this type: much of the region is accessible only via four wheeled drive vehicles; visiting all six of the sites required significant contributions of time; the conditions require specific considerations for sculpture material and design choices. During the project’s lifespan, there was also a major flooding incident in Burketown which saw the entire town evacuated (Waterson Citation2023).

While there is always an element of unique ‘localness’ to remote art projects, the Savannah Way Art Trail provides an opportunity to identify themes that can be considered when strategically planning art trail projects in globally remote locations: 1) the importance of identifying, connecting to, and brokering relationships with local government; 2) listening to locals, which remains critical for success; and 3) there is an ‘art’ to developing, creating, and managing public art trails. From the perspective of remote local governments, public art offers a path to achieving a range of localised, largely tacit outcomes for remote communities, and these outcomes lay the groundwork for tourism growth and associated benefits. However, in order to maximise use of limited government funding for arts and culture and achieve best possible outcomes for rural and remote communities, a number of considerations are relevant. From these themes and through the discussion of the case study, it is possible to offer recommendations that can be used when considering, conceptualising, developing, and executing projects of this kind.

Firstly, it is important to advocate for the distinct role of local government in local arts and cultural sectors. These institutions, which may see personnel turnover, should be empowered to envision, plan and strategise the arts and culture future for their communities. Secondly, where possible it is crucial to aim to embed participatory processes – or deliver ‘participatory public art’ – over projects that propose artworks that could be ‘parachuted into’ any public space or community. This increases local attachment, relevance, and enables the art to become part of the story that locals tell about their place. Thirdly, while policy planning and decision-making can often be driven by top tiers of government, we argue that increased, meaningful involvement by those who regularly ‘inhabit’ the actual public space can help reduce conflicts (Tepper in Royseng Citation2022, 584). Many tensions in this case study could have been addressed early on through establishing a number of principles – more so than processes – for delivering the project (i.e. privileging locals’ perceptions of place over others; empowering local governments in leadership roles). However, fourthly, the cohesiveness of the trail has been undoubtedly supported by the implementation – via Arts Queensland – of CQRASN as a singular institution taking responsibility and accountability for the project management. And finally, rural or remote art trails are distinct from urban public art. There is an importance in understanding the entire town or community in which these sculptures are not intended to form part of the everyday landscape. They can become iconographic, emblematic, and powerful markers of community identity. As such, they must be adopted by the community to ensure their successful implementation and ongoing viability.

While the CQRASN team and authors would not suggest this project has been flawless or should be considered an exemplar for all remote art trails, there are learnings that the team and local communities have taken from the design and delivery of the Savannah Way Art Trail. Importantly, this project represents a significant investment of time, expertise, financial contribution, and passion from a range of people across locations, disciplines, and roles. It remains to be seen how the trail will be considered in the future.

Ethical approval

This project received ethical clearance from CQ University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, number 0000023217.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the extensive management and support of the Arts Queensland partnerships team involved with the Savannah Way Art Trail, led by Julie Tanner and Jessica Cotton. The lead artists, Manning Daly Art, were involved in the community engagement, artwork design, development and installation. We gratefully acknowledge the work, support and advice of the broader project team and contributors: Cultural consultants, Jenuarrie Warrie, Nancy Bamaga; RASN project workers Wanda Bennett, Julie Barratt, Charles Wiles and Tony Castles as well as the collegiality and support of the local councils along the trail. Further gratitude goes to the following organisations, individuals and groups: First Nations artists Siyesha Douglas, Krystal Spencer, Kelly Barclay and Frank Amini; David Hudson, the Ewamian Aboriginal Corporation, Tagalaka Aboriginal Corporation, Bynoe Community Advancement Co-operative Society, Carpentaria Land Council, Gangalidda and Garawa Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, Tourism Tropical North Queensland, The Savannah Way Limited, NorthSite Contemporary Arts, DATSIP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sasha Creina Mackay

Sasha Mackay is a Research Fellow in the School of Education and the Arts at Central Queensland University, affiliated with the Centre for Research in Equity and Advancement of Teaching and Education. Her research explores the practices and social impacts of participatory arts projects for underserved cohorts and communities. Sasha is co-author of the book The Social Impact of Creative Arts in Australian Communities (Springer, 2021).

Elizabeth Ellison

Elizabeth Ellison is Dean of Research, Creative, at University of South Australia and Adjunct Associate Professor at CQUniversity affiliated with the Centre for Research in Equity and Advancement of Teaching and Education. She is Chief Investigator on a number of externally funded regional arts projects and continues to publish on popular culture, regional arts, and supervising postgraduate students.

Michelle Thompson

Michelle Thompson is a Lecturer at Central Queensland University, Cairns, Australia. She has a PhD from James Cook University (2015), which modelled the drivers and barriers to tourism development in agricultural regions. Her research interests are in the areas of food, wine and agri-tourism, as well as aspects of regional and remote area tourism development, nature-based tourism and tourism sustainability. Michelle’s research experience reflects her passion for regional tourism issues and applied research that provides practical outcomes for industry, community and the environment.

Patty Preece

Patty Preece is a musician, electronic music producer, Ableton Live certified trainer and sound artist who works with hacked domestic objects to critically explore aesthetic and relational hierarchies at the intersection of sound, gender and technology. Preece’s practice spans performance, instrument design, production and most recently installation. This Cairns based artist creates performance ecosystems using discarded domestic steam irons, ironing boards, DIY sensors and electronics. Their live performances engage with augmented domestic objects, noise and the relationship of performer, instrument, and context. Preece’s creative practice research explores themes of labour, instrument design, sonic cyberfeminisms and sound art.

Bobby Harreveld

Bobby Harreveld is Professor Emerita at Central Queensland University. Her socially inclusive, equity and access focused qualitative research is in diverse fields from applied arts to agriculture to health and education professions. Her work is affiliated with the Centre for Research in Equity, Access, Teaching and Education of which she was the founding director.

Notes

1. Silo art refers to large-scale murals painted on disused grain silos. In the absence of silos, water tanks are sometimes used.

2. Creative Australia was previously known as the Australia Council for the Arts before the organisation’s rebrand in 2023.

3. 4 of 5 authors were named as Investigators on the project and the other collaborator was involved in early components of the project.

References

- Anwar Mchenry, J. 2009. “A Place for the Arts in Rural Revitalisation and the Social Wellbeing of Australian Rural Communities.” Rural Society 19 (1): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.351.19.1.60.

- Anwar-McHenry, J., A. Carmichael, and M. P. McHenry 2018. “The Social Impact of a Regional Community Contemporary Dance Program in Rural and Remote Western Australia.” Journal of Rural Studies 63:240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.06.011.

- Australia Council for the Arts. 2018. International Arts Tourism: Connecting Cultures. Sydney, Australia. https://australiacouncil.gov.au/advocacy-and-research/arts-experience-regional-australia/.

- Australia Council for the Arts. 2020a. “Creating Art Part 1 – the Makers’ View of Pathways for First Nations Theatre and Dance.” https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/research/creating-art-part-1/. Sydney, Australia.

- Australia Council for the Arts. 2020b. Domestic Arts Tourism: Connecting the Country. Sydney, Australia. https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/research/domestic-arts-tourism-connecting-the-country/.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018. “Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) Technical Paper.” Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/756EE3DBEFA869EFCA258259000BA746/$File/SEIFA%202016%20Technical%20Paper.pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021a. “Croydon 2021 Census All Persons QuickStats.” Accessed December 13, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA32600.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021b. “Doomadgee 2021 Census All Persons QuickStats.” Accessed December 13, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA32770.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2023. “Remoteness Structure: Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Edition 3.” Australian Bureau of Statistics. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/remoteness-structure/remoteness-areas.

- Campbell, H., and F. T. Maclaren. 2021. “Small Growth: Cultural Heritage and Co-Placemaking in Canada’s Post-Resource Communities.” In Cultural Sustainability, Tourism and Development: (Re)articulations in Tourism Contexts, edited by N. Duxbury, 87–109. London: Routledge.

- Cartiere, C., and A. Guindon. 2018. “Sustainable Influences of Public Art: A View on Cultural Capital and Environmental Impact.” In Public Art Encounters: Art, Space and Identity, edited by M. Zebracki and J. M. Palmer, 70–87. London: Routledge.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2023a. Thrive 2030: The Reimagined Visitor Economy - a National Strategy for Australia’s Visitor Economy Recovery and Return to Sustainable Growth, 2022 to 2030. Canberra, Australia: Australian Trade and Investment Commission. https://www.austrade.gov.au/en/news-and-analysis/publications-and-reports/thrive-2030-revised-the-re-imagined-visitor-economy-strategy.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2023b. Revive: A Place for Every Story, a Story for Every Place—Australia’s Cultural Policy for the Next Five Years. Canberra, Australia: Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. https://www.arts.gov.au/publications/national-cultural-policy-revive-place-every-story-story-every-place.

- Crespi-Vallbona, M., and O. Mascarilla-Miró. 2020. “Street Art As a Sustainable Tool in Mature Tourist Destinations: A Case Study of Barcelona.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (4): 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2020.1792890.

- Cunningham, S., M. McCutcheon, G. Hearn, and M. D. Ryan. 2021. “‘Demand’ for Culture and ‘Allied’ Industries: Policy Insights from Multi-Site Creative Economy Research.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (6): 768–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2020.1849168.

- Cunningham, S. M., G. McCutcheon, M. D. Hearn, Ryan, and C. Collis. 2019. Australian Cultural and Creative Activity: A Population and Hotspot Analysis: Central West Queensland: Blackall-Tambo, Longreach and Winton. Brisbane, Australia: Digital Media Research Centre. https://research.qut.edu.au/creativehotspots/wp-content/uploads/sites/258/2020/02/Creative-Hotspots-Central-West-Queensland-FINAL-20190801.pdf.

- du Cros, H., and L. Jolliffe. 2017. “Sculpture Trails: Investigating Success Factors.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 12 (5): 536–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2016.1243120.

- Duxbury, N. 2020. “Cultural and Creative Work in Rural and Remote Areas: An Emerging International Conversation.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (6): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2020.1837788.

- Ellison, E., and S. Mackay. 2023. “The Role of Universities in Strengthening Regional Arts Sectors: Central Queensland University and the Regional Arts Services Network.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 53 (2): 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2023.2184895.

- Ellison, E., and M. Thompson. 2020. “Sculptural Coastlines: Site-Specific Artworks, Beachscapes, and Regional Identities.” In Regional Cultures, Economies, and Creativity: Innovating Through Place in Australia and Beyond, edited by A. Van Luyn and E. de la Fuente, 244–258. London: Routledge.

- Flew, T., and K. Kirkwood. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Cultural Tourism: Art, Culture and Communication in Four Regional Sites of Queensland, Australia.” Media International Australia 178 (1): 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20952529.

- Flying Arts Alliance. 2021. “Cultural Tourism Accelerator Program.” Accessed March 11, 2023. https://flyingarts.org.au/raf/cultural-tourism-program/.

- Foreman-Wernet, L. 2020. “Culture Squared: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Values Espoused by National Arts Councils and Cultural Agencies.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2020.1731040.

- Franklin, A. 2018. “Art Tourism: A New Field for Tourist Studies.” Tourist Studies 18 (4): 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797618815025.

- Gall, S. 2022. “Public Art on Savannah Way Gulf Section to Boost Drive Tourism.” North Queensland Register. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.northqueenslandregister.com.au/story/7898976/savannah-way-art-trail-set-to-paint-a-picture/.

- Gattenhof, S., D. Hancox, H. Klaebe, and S. Mackay. 2021. The Social Impact of Creative Arts in Australian Communities. Singapore: Springer.

- Gattenhof, S., D. Hancox, T. Rakena, S. Mackay, K. Kelly, and G. Baron. 2022. Valuing the Arts in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Australia: Australia Council for the Arts. https://australiacouncil.gov.au/advocacy-and-research/valuing-the-arts-in-australia-and-aotearoa-new-zealand/.

- Green, A. 2020. “Australian Silo Art: Creative Placemaking in Regional Communities.” Journal of Place Management and Development 14 (2): 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-11-2019-0101.

- Gulf Savannah Development Inc. 2018. Tourism Survey Report. Normanton, Australia: Gulf Savannah Development.

- Gunn, L. 2020. “The Art of Trails: How Public Art Trails Are Contributing to Rural Regeneration, a Case Study of the Yarriambiack Silo Art Trail.” Planning News ( Hawthorne, Vic.) 46 (7): 28–29. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.298146191728910.

- Hancox, D., T. Flew, S. Mackay, and Y. Wang. 2020. “Universities and Regional Creative Economies.” In Regional Cultures, Economies, and Creativity: Innovating Through Place in Australia and Beyond, edited by A. Van Luyn and E. de la Fuente, 159–172. London: Routledge.

- Hayes, D., and N. MacLeod. 2006. “Packaging Places: Designing Heritage Trails Using an Experience Economy Perspective to Maximize Visitor Engagement.” Journal of Vacation Marketing 13 (1): 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766706071205.

- Johanson, K., A. Kershaw, and H. Glow. 2014. “The Advantage of Proximity: The Distinctive Role of Local Government in Cultural Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 73 (2): 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12078.

- Kearney, M. 2018. “Art Silos Become a ‘Bit of a lifesaver’ for Struggling Rural Communities.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Accessed June 30, 2018. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-30/rochester-cashes-in-on-silo-art-trail-explosion/9918800.

- Malor, D. 2003. “Trailblazing: Public Art and Community in the Meander Valley, Survey.” Paper presented at the Australian Council of University Art and Design Schools Conference, Hobart, Australia. Accessed October 1–4, 2003. https://acuads.com.au/conference/article/trailblazing-public-art-and-community-in-the-meander-valley/.

- Pennington, A., and B. Eltham. 2021. Creativity in Crisis: Rebooting Australia’s Arts and Entertainment Sector After COVID. Canberra, Australia: The Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute. https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/creativity-in-crisis-rebooting-australias-arts-and-entertainment-sector-after-covid/.

- Queensland Government. 2023a. “Drive Tourism in Queensland.” Business Queensland. https://www.business.qld.gov.au/industries/hospitality-tourism-sport/tourism/qld/drive/qld.

- Queensland Government. 2023b. ““Queensland Music Trails.” Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.dtis.qld.gov.au/our-work/queensland-music-trails#:~:text=The%20Queensland%20Music%20Trails%20will%20support%20jobs%2C%20boost,tourism%20in%20Queensland%20for%20the%20next%2010%20years.

- Qu, M., and S. Zollet. 2023. “Neo-Endogenous Revitalisation: Enhancing Community Resilience Through Art Tourism and Rural Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Rural Studies 97:105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.11.016.

- Rentschler, R., K. Bridson, and J. Evans. 2015. “Economic Regeneration.” Stats and Stories: The Impact of the Arts in Regional Australia. https://regionalarts.com.au/resources/economic-regeneration-stats-and-stories.

- Røyseng, S. 2022. “Public Art Debates As Boundary Struggles.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 28 (5): 581–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2021.2009472.

- Tsakonas, A. 2019. “Victoria’s Silo Art Trail.” Fabrications 29 (2): 273–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2019.1566984.

- Waterson, L. 2023. “Burketown Residents Flown to Safety Amid Record Flooding in Gulf of Carpentaria.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-03-11/final-burketown-evacuation-call-gulf-of-carpentaria-floods/102084112.

- Zebracki, M. 2013. “Beyond Public Artopia: Public Art as Perceived by Its Publics.” Geo Journal 78 (2): 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-011-9440-8.