ABSTRACT

Recently, considerable attention has been devoted to the rise of private art museums in the field of museum and cultural studies. One question which has figured prominently is if these museums are able to stand the test of time. Systematic empirical studies of this issue are so far scarce. On the basis of a new database of private museum closures worldwide, this paper explores why private museums close. By studying such closures, this article aims to advance our understanding of private museum sustainability and longevity. On the basis of statistical data and qualitative content analysis, we also examine what happens to the displayed art collections after such institutions close. Our main findings are that private museum closures are multifaceted, complex events frequently involving financial issues. Moreover, we conclude that because of their funding models and reliance on a sole founder, they are inherently fragile organizations. Indeed, we find that the median number of years private museums have been open before closing is no more than 10.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global rise of private art museums has received growing attention in the field of museum studies (Adam Citation2021; Kalb Cosmo Citation2021; Walker Citation2019) as well as related fields such as the sociology of art (K. J. Kolbe et al. Citation2022) or cultural economics (Meier and Frey Citation2003). The increasing body of scholarship focuses on different aspects of this institutional form, including their art collector founders (Larry’s List, Citation2015, Citation2023), financial situation (Walker Citation2019), historical origins (Higonnet Citation1997; Kalb Cosmo Citation2021), global dimensions (de Castro Citation2018; De Nigris Citation2018; Dieckvoss Citation2020; Esquivel Durand and McDaniel Tarver Citation2018), the motivations behind setting up a private museum (Adam Citation2021; Kalb Cosmo Citation2021; Walker Citation2019), or their longevity (Meier and Frey Citation2003; Walker Citation2019). Regarding the latter issue, scholars and art market experts wonder if a private museum is able to stand the test of time (see, for example, Adam Citation2020) and if not, what leads to its closure or incorporation or transformation into a potentially more sustainable form, such as a publicly funded museum. Little systematic knowledge is available, however, about private museum closures and about the destination of their collections after closure, and no frameworks have been developed to theorize them. The few studies that exist (see, e.g., Adam Citation2020; Walker Citation2019) mainly focus on cases, which have the advantage of providing rich, contextual details. In this paper, we take a quantitative approach by creating a database of closed private museums and identifying the reasons for their closure.

Better knowledge of why private museums close is of both academic and societal importance. What is at stake among others is the question if private museums, as an organizational form, constitute a new and lasting addition to art worlds, which may reconfigure power dynamics within these fields (Foster Citation2015; Graw Citation2009), or, instead, if they should be considered as a temporary phenomenon which is not sustainable in the long run. From a societal point of view, this question is important as they are frequently seen as an important addition to the cultural landscape or even a remedy to declining government support for the arts (Walker Citation2019). If they close down easily, however, the remedy may not be long-lasting and sustainable. Moreover, private museum closures raise the question of what happens to their collections, often holding costly artworks which public museums cannot afford to buy themselves (Adam Citation2020): are they sold, will they become available in other arts institutions, or will they not be visible to the public anymore? Enhancing our understanding of these reasons is indispensable for established collectors as well, who may face the choice of whether to donate their collections to an already existing (public) museum or found a museum of their own. The aim of this paper is therefore to provide a systematic account of why private art museums close worldwide. This in turn should advance our knowledge of private museum sustainability and their survival in the long run. By analyzing the destination of the art collection of the closed museums, this article also seeks to understand the impact of museum closures on the art world.

In line with previous studies, we define private art museums as museums which have been established and controlled primarily by private individual art collectors or their descendants, which receive limited or no public funding, have a permanent art collection, and make this collection accessible to the public in a physical structure on an ongoing basis (K. J. Kolbe et al. Citation2022). Given that most private museums collect and exhibit modern and contemporary art, we focused on this category of art. We define modern and contemporary art as art that was created after 1900.Footnote1

We show that 76 out of 523 private museums for modern and contemporary art, which we managed to identify worldwide, closed down over the recent decades. These closures were both voluntarily and involuntarily and happened for structural as well as incidental reasons. In particular, we differentiate between 12 different reasons that contributed to the closure of these museums. We find that closures are mainly motivated by financial reasons, followed by insufficient interest from the public, the relocation of the museum, building issues, and new strategies to display the museum’s collection. On the basis of these findings, we argue that private museums are fragile in the sense that their livelihood can easily be threatened, given that they tend to be expensive to run and heavily depend on a single founder’s financial support. This support may in turn be withdrawn if the founder’s own finances deteriorate or if his interest in the museum wanes. With this study, we therefore raise important theoretical points regarding the sustainability of private art museums; the closures of these institutions, for example, can question whether the long-term operation of private museums is feasible. Similarly, our findings point towards another key question: if a large number of these museums close down after a period of time, what are their contributions to the art world and display of artworks to the public in the long run?

In the next section, we review literature on private art museums’ longevity and closure. We then turn to explaining the methodological approach of this study (section 3). Afterwards, we present key characteristics of museums which close (section 4), their closure reasons (section 5), and the destination of their collections (section 6). We then discuss our results and conclude the paper (section 7).

2. Literature review

Almost any study of private art museums emphasizes that running them is costly. Although precise figures are difficult to obtain as most private museums are not fully transparent about their finances, an estimation by Larry’s List’s private museum report offers a point of departure: the authors of the report estimate that ‘operating one square meter of museum costs 431 USD worth of expenses’ per year (Larry’s List, Citation2015, 100). Taking the average size of a private museum (3.389 square meters), they calculated that the average private museum’s operating costs would be a total of 1.5 million USD per year and a multiple of this amount for the larger, more established private museums. Covering these costs is challenging. Several studies have noted that in many countries, these entities are not or only partially entitled to public subsidies because of their private nature (Global Private Museum Network, Citation2020; K. J. Kolbe et al. Citation2022). Given that they are founded by an individual collector and often even carry their founders’ name (Velthuis et al. Citation2023), attracting charitable contributions from other philanthropists is equally hard. Frey and Meier (Citation2002) show that private museums need to rely more than public museums on market sources of income such as ticket sales, the museum shop, and a museum restaurant, and need to be more entrepreneurial in developing these. Others have noted, however, that it is unachievable to run and sustain a museum solely on these sources of income (Alexander Citation1996; Froelich Citation1999; Lindqvist Citation2012). Walker (Citation2019, 146) likewise notes that private museums permanently require such large funds that they ‘struggle to endure beyond the original founder’s lifetime without substantial endowments.’ In the absence of these endowments, museum founders try to secure a long-term future for their collections by seeking to donate the collection or transferring the entire institution to a public entity (K. J. Kolbe et al. Citation2022; Schuster Citation1998).

Although finances are most widely mentioned as reasons for museum closure, they are not the only ones. Focusing on the Chinese art museum scene, De Nigris (Citation2018) notes that many of the founders opened up private museums without a long-term strategy – that is, curatorial, preservation, and research plans for the future are frequently missing. Adam (Citation2020) identifies two other reasons behind the private museum closures: the founders’ disengagement from their project and wrongdoing by the founders, either alleged or supported by evidence. Studies of the destination of the art collection after a private museum closes are even more scarce. Generally, the assumption is that ‘collections are disappearing from public view at a rate of knots’, due to sudden closures of such institutions (Adam Citation2020). While the case study approach that all these studies take has the benefit of providing rich insights into closing processes, the downside is that a systematic review of museum closure reasons is lacking. As a result, we do not know if other reasons may exist for museum closures, how regularly private museums close, or how long they have typically been in operation at the moment of closure. In addition, no study has examined what happens to the collections of the museums that close down. In the next section, we provide the methodology for our study which seeks to address these issues.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research approach

To study the closure of private museums, we relied on a new database created by Velthuis et al. (Citation2023), which in turn built on an earlier database of the art market research company Larry’s List (Larry’s List, Citation2015).Footnote2 The latter included more than 300 private museums that opened up until 2016, while the database by Velthuis et al. (Citation2023) updated this until 2022 and included private museums which had potentially closed down. Both databases rely on publicly available resources and were established on the basis of a systematic search of a wide variety of art media, as well as pre-existing art collector and art institution databases (for the full methodology and the most recent findings about private art museums in general, see Larry’s List, Citation2023; Velthuis et al. Citation2023). While it is possible that some low-profile museums are not represented in it, as of today, this is the only up-to-date and comprehensive database on private art museums.

To ascertain if museums in the database had indeed closed was not always straightforward, as we could not visit all the museums in person, given their global dispersion. Therefore, we (1) sent an email to the museum to inquire if it was indeed closed; (2) checked if the museum’s official website (if any) was still functioning; (3) checked if the museum’s Facebook pageFootnote3 (if any) was still active; and (4) scrutinized if closure of the museum was mentioned on the museum’s official website, Facebook page, in any local or international newspaper archived in the international newspaper archive LexisNexis or in any reviews and comments on online consumer review (OCR) systems (Google Maps, TripAdvisor, and, in a few cases, Yelp). If one or more of these criteria indicated that the museum was closed, and none of the other criteria suggested it was still open, we considered it closed (see for the frequency of each closure criterion).

Table 1. Criteria used to establish if a private museum is closed.

Next, we created a document database for all closed museums in order to identify the reasons for closure and the destination of the collection. First, we used the main newspaper database LexisNexisFootnote4 as well as a systematic Google search to retrieve documents (news articles, media interviews with the founders or their representatives, websites, cached web pages). We also searched the online archives of three widely read international art news magazines and websites: The Art Newspaper, Artforum, and ARTnews. In a further round of data collection, we utilized data from the closed museums themselves: in the aforementioned e-mails, we asked the museum representative if, when, and why the museum had closed (see for the composition of the document database).

Table 2. Composition of the document database.

For the data analysis of the 196 documents in the database, we used the software package Atlas.ti (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). This approach allowed us to obtain detailed insights into the life trajectory of each museum. We first carefully read the data in order to identify excerpts which were relevant to the topic of museum closure and then coded these. After multiple rounds of coding by both authors, we thematically grouped closure reasons which resulted in the categories that we discuss in the following sections. In many cases, the references to closures in our data were clear and unambiguous (for instance, a newspaper article cited the founder who told why they closed down the institution); in some other instances, however, we had to look for and compare with other sources to determine the closure reason(s).

In some instances, we encountered competing narratives, for instance, when the founders in email exchanges identified different closure reasons than media reports. Such competing narratives may result from several factors. Founders, for instance, have an interest in a narrative that puts themselves in a positive light and shifts the blame for the closure on others or unforeseen circumstances. We therefore treat the data critically and cautiously and explicitly look for data triangulation (that is, comparing and contrasting data from various sources) where possible. Also, for some museums, we found multiple reasons for their closure. The Marciano Foundation in Los Angeles is exemplary in this respect. ‘Low attendance records’ were presented as the official reason for its closure, only 2 years after its opening (Miranda Citation2019). Media reports suggest that the museum’s closure was also informed by the founders – the fashion entrepreneurs and art collectors Paul and Maurice Marciano – underestimating the costs of running it (Moynihan Citation2019; Perman Citation2020). Moreover, the museum was seen as poorly managed, while the founders apparently became disgruntled with the employees’ attempts to unionize and laid off employees in response to those attempts (Perman Citation2020).

Although usually less layered than in this case, we will see that private museum closures are complex events where multiple reasons, usually including financial ones, interact with each other.

4. Characteristics of museums which close

The private museum database we took as a starting point contains 547 museums in total, founded between 1960 and 2022. Of these, we were able to identify 76 museums which had closed. Another 24 museums were still open, but while they had started out as private museums, they had changed structure in the meantime, for example, because they had been transformed into a government entity. Because this latter category is beyond the scope of this article, we will ignore it in the remainder. Four hundred and forty-seven museums in the database fit the definition we formulated and are still open. In other words, 14.6 percent (76 out of 523 private museums) have closed. While it is difficult to compare this number to, for example, the closure of public museums (especially because they operate differently and no systematic data on their shutdown exist), we consider this percentage relatively high, in particular, given how recently many of them had opened; indeed, the median number of years that private museums were open before they closed is 10 years. Understanding what led to their shutdowns, is therefore all the more important.

Before doing so, however, we discuss some of the main characteristics of both open and closed private museums, as well as the main characteristics of their founders. Of the 76 closed museums we identified, most were located in the United States, Germany, and South Korea (see ), which reflects the fact that these are also the three countries with the largest number of private museums. The United States hosts 13.4 percent (or 60) of all 447 open museums, as well as 13.2 (or 10) of all 76 closed museums. In countries like Russia, Switzerland, and Brazil, the number of closures is relatively high in relation to the private museum population in these countries, but given the low overall numbers, we are cautious in attributing meaning to this. When it comes to gender, over two thirds (67.6 percent) of the closed museums were founded by men, which again reflects the overall population. The size of the permanent collection ranges from 300 to 13.300 works, with an average of 1666 works, which is slightly lower than the average (1835) of museums which are open. Among the closed museums are some, such as the Marciano Art Foundation in Los Angeles or the Cass Sculpture Foundation in Chichester (UK) which were relatively well known to the public, while others were small and seemed to be frequented by a local public of arts insiders. The oldest private art museum which has closed (La Casabianca in Italy) opened in 1978 and remained open for 43 years, but the vast majority of closed museums (57) opened in the new millennium, some as recent as 2018. The earliest closure of a private museum in our database took place in 1990, and the most recent ones in 2021.

Table 3. Main locations of open and closed private museums.

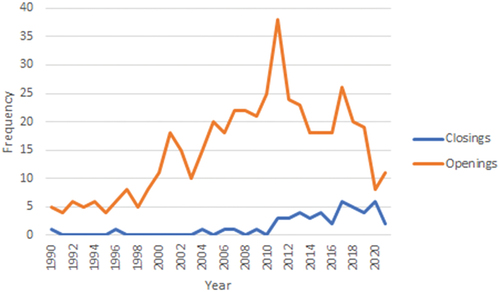

Most private museums for modern and contemporary art opened in 2011 (38 museums), while most museums closed in 2017 and 2020 (6 museums; see ).Footnote5 With its operation time of no more than a year, the Dairy Art Centre in London, United Kingdom, was the shortest-lived museum: it was open from 2013 until 2014. We had expected that private museum closure hinges on the age of the founder: founding the museum at a high age may mean that little time is left to make provisions for its longevity. However, we found no differences in the age of founders of closed museums and those which are still open (57 in both cases). In some cases, the founders died before their museums even opened their doors; this does not, however, mean that the museums had to close right away, as frequently family members step in. In 13 cases, the founders have, at the moment of writing this article, died. But the museum’s closure was rarely related to the founder’s death, as in four cases, the museums had already closed before the founder died; in three cases, there was a long time lag (of 6, 8, and 13 years) between the death and the closure; in one case, a different reason for closure was stated (the Covid crisis); and in one other case, the museum opened after the founder had already died, so the actual foundation was executed by the founder’s descendants (for the remaining four cases we were not able to make any claims based on our data).

5. Reasons behind museum closures

We were able to identify 56 reasons for closure, pertaining to 38 private museums in total (see ). For 25 museums, only one closure reason was identified; for eight museums, two reasons, and for five museums, three reasons. In general, our data suggest that the closure of private museums is a complex, layered process, frequently involving financial issues, which are amplified by a variety of other reasons. Before discussing these in detail, we should point out that ‘relocation’ stands out from all other reasons, as in this case, the closure of one museum coincides with the opening of another by the same founder. The total number of private museums does not change, in other words, unlike in all the other cases. The relocation may be within the same city, as was the case, for instance, of the Museo Jumex, which moved locations within Mexico City in 2013 (Esquivel Durand and McDaniel Tarver Citation2018; Fundación Jumex, Citationn.d.), within the same country, or across borders. In the latter case, the impact of the closure on the local arts scene may not be different than when the museum had closed without opening a new location elsewhere, as local artists and arts audiences no longer have easy access.

Table 4. Reasons for private museum closure.

5.1. Financial, governmental and legal issues

In many cases, the decision to close the museum was not voluntary but was made because of unforeseen circumstances. Most frequently – in 14 cases, or 36.8 percent of the museums on which we have data – these unforeseen circumstances are related to finances. This was for instance because the financial situation of the founder – who usually needs to provide ongoing support to the museum as ticket sales and income from, for example, a gift shop, a restaurant or building rental are not sufficient for covering the operational costs – deteriorated. For instance, the Dutch Scheringa Museum of Realist Art closed down when the financial institution which the museum’s founder owned and ran, DSB Bank, went bankrupt in 2009. As part of the bankruptcy proceedings, one of the bank’s main creditors seized the museum’s collection as a guarantee (Wensink and de Witt Wijnen Citation2009). Likewise, the operation of the Austrian Essl Museum was endangered by the financial losses that the Essl family’s company Baumax (a home improvement chain) suffered in the Balkans (Michalska Citation2016). In 2014, media reports suggested that the family hoped for the government to buy the collection so that the company could be saved; this, however, did not happen. The museum eventually had to close down in 2016 (Michalska Citation2016).

Financial issues also include cases where the costs of running the museum were higher than originally expected. Take the Werner Coninx Stiftung, which made part of the 14,000 art objects collected by the Swiss artist and arts patron Werner Coninx accessible to the public in a museum. The foundation closed down in 2012 after 26 years because of ‘financial issues’ (pers. comm., January 19, 2022) – in particular, according to media reports, high costs of the maintenance and renovation of the museum building and the lack of income of the foundation (Fankhauser Citation2014). Casa Daros Brazil is another example. Part of the Switzerland-based Daros Latinamerica collection, Casa Daros Brazil was only open for 2 years in Rio de Janeiro as ‘horrific operating costs’ (Szczesniak Citation2015) interrupted its run in 2015. Besides the high costs, Casa Daros Brazil’s operation, as a media report pointed out, was complicated by the fact that the founder Ruth Schmidheiny’s ex-husband, the billionaire entrepreneur and philanthropist Stephan Schmidheiny, stepped away from the foundation. In addition, the departure of key staff members, such as the curator and the art and education director of the space, rendered the museum’s operation difficult (Martí Citation2015).

Financial issues are not just the most prevalent closure reason; indirectly, they come up again in a number of other closure reasons. This holds for the four museums (10.6 percent) which closed because of legal issues. In some cases, these legal issues meant that the museum or its founders had to cover costs of litigation. The Hallen Fur Neue Kunst, for instance, a museum founded by the artist Urs Raussmüller in the Swiss border town of Schaffhausen was involved in a lengthy lawsuit regarding ownership of one of the works in the collection. The lawsuit depleted the museum’s resources, resulting in the museum’s closure in 2014 (Mustedanagic Citation2014). Likewise, legal issues may prevent the founder from continuing to support the museum. The Shi Shang Art Museum in Beijing, China, for example, had to close down in 2018 after its founder, the businesswoman and art collector Liu Fengzhou was detained by Chinese authorities in a graft investigation (Adam Citation2020). Likewise, the Institute of Russian Realist Art (IRRA), which displayed Soviet and post-Soviet realist artworks from the 20th century, closed down in 2019 after the founder Alexei Ananyev’s bank Promsvyazbank was nationalized and fled the country in order to avoid – allegedly politically motivated – embezzlement charges (Adam Citation2020; Fletcher Citation2020).

Lack of government support, which was identified as a closure reason in four cases (10.6 percent of the total), likewise frequently has a financial component, for instance, when government subsidies are withdrawn or do not materialize.

5.2. When the public’s interest is lacking

Insufficient interest from the public also regularly (in six cases or 15.8 percent) plays a pivotal role in closures by questioning the legitimacy of the museum and therefore eroding the motivation of the founder to continue devoting financial resources. We encountered two different reasons for low interest from the public. First of all, private museums frequently display a permanent collection and do not always have rotating exhibitions; as a result, visitors may not be prone to return once they (think that they) have seen the permanent collection. In some cases, the collection itself may raise little interest. Take, for example, the Terra Museum of American Art in Evanston, which closed down in 2004 due to low visitor numbers, despite the fact that the museum did not charge admission fees. As The New York Times reported on the museum’s closure: ‘most Chicagoans, including members of the city’s art establishment, have greeted the closing with a collective shrug’ (Bernstein Citation2004). The foundation then decided to develop a different strategy to make its collection accessible to the public.

Second, we found that the location of the museum can be a factor in limited visitor interest. On the one hand, private museums located in metropolitan art centers may face competition over visitors from well-established other museums in the vicinity. On the other hand, private museums located outside of those centers can be confronted with a small local audience and difficulties in attracting visitors from afar. This applies, for instance, to the Fondation d’art contemporain Daniel et Florence Guerlain in Les Mesnuls, which closed in 2006. The founders attributed that to the fact that the institution was ‘40 kilometers from Paris’, and while people came for the openings, later, there were not enough visitors to ‘carry on’ (pers. comm., March 31, 2022).

The closure of another five museums (13.2 percent) was related to the fact that the museum building was no longer available for the collection or displaying the collection in an aging building was no viable option. Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact were invoked as the main reason for the permanent closure of the museum in three cases (7.8 percent). We cannot exclude, however, that underlying structural reasons may have played a role as well, so that the pandemic was the trigger for a museum already facing financial trouble or limited interest from audiences.

5.3. Voluntary closures

While in all the previous cases, the closure was framed in involuntary terms, in response to ‘external’ problems of a structural or incidental nature, in another set of cases, the decision is framed as planned and voluntarily, i.e. as a decision the founders took autonomously and were not forced to take because of external circumstances. Again, it is hard to say for sure that finances were not playing a role in the background as well, but they were not mentioned by founders or anybody else with knowledge of the closure. The data allow us to distinguish three main types of voluntary closures. First of all, in three cases the founder lost interest in the project or in the art world more generally (Adam Citation2020; K. J. Kolbe et al. Citation2022). This happened, for instance, to Dennis School, founder of World Class Boxing in Miami which closed in 2013 after 11 years of operation:

I got burnt out in the contemporary art world. For me [it] had become too much about money and personality, so I wanted to take a break, but still wanted to keep collecting. (Harris Citation2017)

In a second set of (three) cases, the museum was intended as a temporary project.

A third and final set of reasons to close the museum voluntarily relates to strategic changes in making the collection accessible (this reason contributed to the closure of five museums; 13.2 percent). A good example of such a decision is the case of the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation in Miami, which closed down its CIFO Art Center in 2018 after displaying Ella Fontanals-Cisneros’ collection for 13 years. The reason which the foundation provided was transitioning to an ‘international exhibition model’, which would allow the foundation to share its collection with a wider set of audiences (Durón Citation2018) by working together with partner institutions throughout Latin America. Similar reasons led to the closure of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary museum in Vienna in 2017. Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza stated that she no longer wanted her engagement with the arts to take the shape of a private museum or ‘the world of galleries, art fairs and art institutions’ (Vogel Citation2015, translation from German by the authors). After the museum closed, the foundation started to organize temporary exhibitions of its collection around the world (pers. comm., January 19, 2022).

6. The destination of the collection

The above discussion of closure reasons suggests that private museum closure does not necessarily mean that the collection disappears from view but rather, they can appear at other exhibitions or museums. Building on this notion, in this last section, we study more systematically what happened to the closed museums’ collection. Answering this subquestion is crucial to understanding the trajectory of the art collections of the closed museums: did they remain available to the public in some form after the shutdown, or was the public accessibility of these frequently valuable collections as short-lived as the museums themselves? Apart from asking if the collection remained accessible to the public, we also want to know whether the collection changed ownership (for example, through a sale to another collector or donation to a museum). It is important to realize that a collection is rarely handled in its entirety – the founder may keep some works available for strictly private viewing, sell some others, donate them, or make them available for loans. What we therefore report on is what happened to major or key parts of the collection, but not necessarily to the entire collection.

For the 31 closed private museums with data on the current whereabouts of (main parts of) the collection, in 24 cases (77.4 percent), the collections are still (potentially) on view to the public (see ). Within this category, ownership of the collection did not change in 16 cases (51.6 percent). These include the five museums which have closed in order to re-open at another location, as well as four of the five cases where the museum closed because of a change in collection strategy (in the fifth case, the new strategy involved a change in ownership): works from the collection are now actively loaned to other arts institutions or made available for temporary exhibitions. For instance, the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation still owns the art collection that is shared through its itinerant exhibition model (Durón Citation2018). In eight other cases (25.8 percent) within this category, the collection remained available to the public, but the ownership changed either because the founders or foundation donated or sold (major parts of) the collection to a museum or to another party which continued to exhibit it. This happened, for instance, to the aforementioned Fondation d’art contemporain Daniel et Florence Guerlain; in 2012, 6 years after the closure, the founders donated 1,200 drawings from the collection to the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (pers. comm., March 31, 2022). In the case of the Scheringa Museum of Realist Art, the collection was first seized and passed to the Deutsche Bank as part of bankruptcy proceedings but then sold to a Dutch businessman who made it available to the public again in his own private museum (Kunst Citation2012; Wensink and de Witt Wijnen Citation2009).

Table 5. Destination of the closed museums’ art collections.

In seven cases (22.6 percent), the collection disappeared from public view. Within this category, we can again make a distinction between cases where the ownership changed (two cases; 6.4 percent) and where the original owner held on to the collection (five cases; 16.2 percent). An example of the first is the Me Collectors Room Berlin – Stiftung Obrecht, whose owner sold major parts of the collection at auction, while an example of the latter is the aforementioned Hallen Fur Neue Kunst: when it closed, the collection was transferred to the foundation’s headquarters in Basel, where it is ‘not on view for the public’ (pers. comm., February 15, 2022). In at least one other case, it seems like the collection changed ownership as well and is no longer on view, but it would take detective work to know the current whereabouts: the Institute of Russian Realist Art (IRRA), whose collection, together with the founder’s bank Promsvyazbank, seems to have been seized by the Russian government as part of a lawsuit involving embezzlement charges – which may, however, have been politically charged. In 2019, part of the collection was found in a storage facility. At the time, reports in the media speculated that the art would be distributed over Russian state museums (Kuesel Citation2019; Martin Citation2019).

7. Discussion and conclusion

On the basis of a new database of 547 private museums worldwide, in this paper, we identified 76 which had closed, as well as the reason for their closure. In doing so, our study has both systematized and enriched findings of previous studies. In particular, we find that each closure is unique and comes with its own constellation of reasons and its own closure narratives. At the same time, we identify clear patterns in the closure reasons of the 76 museums in our database: financial issues dominate, but they are rarely the sole cause. They are rendered urgent when public interest in the museum (read: attendance figures), which lends legitimacy to the project, is waning. Moreover, financial issues manifest themselves in many different ways: for instance, it may be the founder’s company, on which his wealth is based, running into financial trouble; lawsuits using up the operating budget; or the art market’s proverbial death, divorce, and debt which render the necessary ongoing financial support for the museum from its founder unsustainable (see, e.g., Velthuis Citation2005).

7.1. Theoretical and practical implications

Our study has both theoretical and practical implications. First of all, it contributes to a better understanding of private museums as an organizational form. Studies so far have stressed that they are highly flexible institutions that can make decisions, take risks and respond to opportunities which public museums need to forego because of their bureaucratic organization (see Brown Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Alternatively, private museums have been characterized as powerful organizations, which are part of a wider privatization trend where art dealers and collectors are becoming more decisive in shaping the canon (Brown Citation2019, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Graw Citation2009). Although not necessarily contradicting the first characterization, but in contrast to the second one, our study suggests that private museums are highly fragile institutions: they are very expensive to operate and need financial support on an ongoing basis, given that market sources of income are usually insufficient. For this support, they rely by and large on a single person (the founder) as government subsidies and philanthropic contributions are unlikely to come in. Such heavy reliance on a single source of income renders these organizations vulnerable (see Carroll and Stater Citation2009): it means that changes in the wealth of the founder, a founder’s waning interest in the museum, or the founder’s death will almost inevitably have a direct impact on the financial health of the museum. While an endowment would be the main solution to keep the museum’s doors open for longevity, few founders are so rich that they can provide one that is sufficiently large. On top of this, the many unforeseen circumstances which private museums face, such as lawsuits or building issues, can also jeopardize the organization’s future. While these unexpected expenditures are in itself already hard to plan for, the challenge is even bigger because of the relative novelty of this organizational form, meaning that best practices have hardly been diffused yet, and some museum founders may not exactly know what they are venturing into.

The fragility of this organizational form questions the contribution of private museums to the art world: it can be applauded that the museums make art collections accessible to the public, which would otherwise remain behind closed doors. But at the same time, the fact that their operation will frequently be short-lived suggests that in many cases, they may be more of an addition to arts scenes, rather than a long-term substitute for museums, which are publicly funded or privately funded by a large group of cultural philanthropists. As private museums frequently enjoy tax benefits as well similar to their founders, meaning that implicitly public funds are involved, it is also legitimate to pose the question of whether more oversight is warranted. However, answering this question is beyond the scope of this article.

7.2. Practical implications

The practical relevance of these findings is threefold and pertains to different stakeholders involved. First of all, as a large number of private museums were founded in the last decade, art worlds and societies should be prepared for many more private museum closures to come in the near future. Concomitant requests to the government can be expected to ‘save’ these museums by incorporating them in pre-existing public museums or transforming them into public museums of their own, as has frequently happened in the past. As this may involve substantial public resources, local and national governments should already start discussing now under what conditions these resources should be committed and what policies should be developed.

The second practical contribution of our study is in thinking through the impact of museum closures. On the one hand, our data suggest that when it comes to the public accessibility of the art itself, the impact of private museum closures is limited: in more than two-thirds of the cases, the art remains accessible, because it is donated to a public museum or because the owners lend it out on a temporary basis to other institutions. On the other hand, it is important to realize that high numbers of closures may question the legitimacy of private museums as an organizational form and valuable addition to contemporary art worlds in the long run. This may call into question the legitimacy of the collectors who open these private institutions, too: opening a private museum might be seen as a fashion that is not fundamentally different from other forms of conspicuous, status-driven, and short-term oriented luxury spending. At the same time, it is crucial to note here that motivations behind founding a private museum are diverse (K. J. Kolbe et al. Citation2022; Velthuis et al. Citation2023); moreover, as we have shown, the closures are often related to external circumstances beyond the founder’s control, which the public may recognize and therefore not hold against the founder. Therefore, future research on perceptions of private museums and their founders among the public should make clear how the legitimacy and societal status of founders are affected by the opening and closing of museums (K. Kolbe Citation2023).

This brings us to the third practical contribution, which pertains to collectors in particular. Our study suggests that operating a private museum in the long run requires careful financial planning and a clear funding strategy in order to offset the inherently fragile character of the organizational form. Without such planning and strategy, financial turmoil on the part of the founders, events in their life course, or the variety of unforeseen circumstances which we have documented in this study are likely to force the museum to close (De Nigris Citation2018; Larry’s List, Citation2023; Walker Citation2019). Our study suggests that collector’s expectations should be tempered. It is hard to have their names remembered for longevity, following yesteryear’s private museum founders like Albert C. Barnes, Isabella Stewart Gardner, and Henry Clay Frick. The latter’s institutions are the exception rather than the rule; moreover, at a time when cultural policy budgets are under pressure and many more art museums exist in any region, governments are less likely to step in and ‘rescue’ a private museum than in the past. Viewing a private museum as a temporary project, as some of the cases in our study have done, may be more realistic.

7.3. Limitations and further research

Our findings come with the usual limitations. Although we identified museum closures by means of a wide variety of sources, we cannot conclusively state that our database is fully comprehensive. There might be institutions whose visibility was highly limited, meaning their closure remained under the radar as well. Another potential drawback of our study is that some closure reasons never came to light as the founders or other stakeholders had no interest in revealing them.

This study has several implications for future research. First, both private museum openings and their closures should be further theorized – no clear theoretical models currently exist to understand their life course. Second, we have not been able to scrutinize the impact of museum closures on the arts community in which it is embedded: how was the closure perceived, and what does it mean for audiences, artists, or other arts institutions in the former private museum’s vicinity? Also, for this study, we did not consider museums that have gone through a structural change, morphing into a new public museum or integrating into an existing one. Studying these processes can reveal under which conditions governments are (not) willing to rescue a private museum. Finally, more detailed studies of private museums’ funding models could be helpful to understand how, when, and where financial fragilities appear and to develop more robust alternatives.

Acknowledgments

Detailed feedback from the two anonymous reviewers, Johannes Aengenheyster, Kristina Kolbe and Andrea Friedmann Rozenbaum on a previous version of this paper is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Olav Velthuis

Olav Velthuis is Full Professor in Cultural and Economic Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. He is Principal Investigator of the research project Return of the Medici? The Global Rise of Private Museums for Contemporary Art, which is financed by the Dutch Research Council.

Marton Gera

Marton Gera is a final-year Research Master’s Social Sciences student at the University of Amsterdam and an incoming PhD candidate at the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University. His research interests include organizational processes in the creative and cultural industries and the intersection of organizational storytelling and politics.

Notes

1. This definition thus excludes corporate museums, private collections which are inaccessible to the wider public or museums with strong involvements of public or other private actors beyond the collector and their family, such as public–private partnerships or museums run by foundations or governed and financed by groups of philanthropists or those which predominantly rely on government subsidies. Given the focus on modern and contemporary art, we did not consider private museums displaying, for example, folk art, indigenous art or old master paintings.

2. Larry’s List is an art market research bureau that provides data and insights to art collectors.

3. The advantage of Facebook over other social media platforms is that it is among the oldest (so is likely to cover museums which closed a decade ago or even earlier), has been widely used in the cultural sector, and has relatively strong global coverage.

4. LexisNexis is a widely used news archive; it has a searchable database of news articles from all over the world. It includes general newspapers, weeklies, popular magazines, trade magazines, and legal journals (Gilbert and Watkins Citation2020).

5. Indeed, a correlation analysis over the period 1990–2021 reveals that there is a particularly strong (0,857) and highly significant correlation between the number of museum closings worldwide in a year and the number of museum openings 7 years earlier.

6. In one other case, the Salsali Private Museum in Dubai, United Arab Emirates relocation of the museum has been announced in 2019, and the old space closed down, but given that no new space has been opened in 2022, we consider it permanently closed rather than relocated.

References

- Adam, G. 2020. “Not Here to Stay: What Makes Private Museums Suddenly Close?” The Art Newspaper, February 13. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/02/13/not-here-to-stay-what-makes-private-museums-suddenly-close.

- Adam, G. 2021. The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum. Hot Topics in the Art World. London: Lund Humphries Publishers.

- Alexander, V. D. 1996. “From Philanthropy to Funding: The Effects of Corporate and Public Support on American Art Museums.” Poetics 24 (2–4): 87–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(95)00003-3.

- Bernstein, D. 2004. “A Museum in Chicago Is Closing Its Doors.” The New York Times, October 30. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/30/arts/a-museum-in-chicago-is-closing-its-doors.html.

- Brown, K. 2019. “Private Influence, Public Goods, and the Future of Art History.” Journal for Art Market Studies 3 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.23690/jams.v3i1.86.

- Brown, K. 2020a. “After Closing His Berlin Museum, Renowned Collector Thomas Olbricht Is Selling More Than 500 Works from His Collection.” Artnet News, August 7. https://news.artnet.com/market/thomas-olbricht-sale-van-ham-1900437.

- Brown, K. 2020b. “When Museums Meet Markets.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 19 (3): 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2020.1811488.

- Carroll, D. A., and K. J. Stater. 2009. “Revenue Diversification in Nonprofit Organizations: Does it Lead to Financial Stability?” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 19 (4): 947–966.

- Castro, M. B. D. 2018. “The Global/Local Power of the Inhotim Institute: Contemporary Art, the Environment and Private Museums in Brazil.” AM Journal of Art and Media Studies 15 (2018): 161–172. https://doi.org/10.25038/am.v0i15.239.

- De Nigris, O. 2018. “Chinese Art Museums: Organisational Models and Roles in Promoting Contemporary Art.” International Communication of Chinese Culture 5 (3): 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40636-018-0113-x.

- Dieckvoss, S. 2020. “The Musée d’Art Contemporain Africain Al Maaden in Marrakech: A Case Study in Collecting and Place-Making.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 19 (3): 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2020.1806503.

- Durón, M. 2018. “Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Will Close Miami Exhibition Space, Names 2018 Grant Recipients.” The Art Newspaper, January 24. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/cisneros-fontanals-art-foundation-will-close-miami-exhibition-space-names-2018-grant-recipients-9692.

- Esquivel Durand, L., and G. McDaniel Tarver. 2018. “Colección Jumex and Mexico’s Art Scene: The Intersection of Public and Private.” In Art Museums of Latin America, edited by M. Greet, 160–175. London: Routledge.

- Fankhauser, C. 2014. “Stiftungsrat Der Sammlung Coninx Wirft Das Handtuch.” Schweizer Radio Und Fernsehen, January 7. https://www.srf.ch/news/regional/zuerich-schaffhausen/stiftungsrat-der-sammlung-coninx-wirft-das-handtuch.

- Fletcher, L. 2020. “Ananyev Brothers Face Mounting Pressure Over Russian Bank.” Financial Times, December 9. https://www.ft.com/content/882eed14-e600-4d6f-b1e3-a1d1539dc12f.

- Foster, H. 2015. “After the White Cube.” London Review of Books 37 (6): 25–27. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v37/n06/hal-foster/after-the-white-cube.

- Frey, B. S., and S. Meier. 2002. “Museums Between Private and Public the Case of the Beyeler Museum in Basle.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.316698.

- Froelich, K. A. 1999. “Diversification of Revenue Strategies: Evolving Resource Dependence in Nonprofit Organizations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 28 (3): 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764099283002.

- Fundación Jumex. n.d. “History.” https://www.fundacionjumex.org/en/fundacion/historia.

- Gilbert, S., and A. Watkins. 2020. “A Comparison of News Databases’ Coverage of Digital-Native News.” Newspaper Research Journal 41 (3): 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532920950039.

- Global Private Museum Network. 2020. “Museums.” http://globalprivatemuseumnetwork.com/museum.

- Graw, I. 2009. High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Harris, G. 2017. “Miami Collector Dennis Scholl — “I Got Burnt Out in the Contemporary Art World”.” Financial Times, December 6. https://www.ft.com/content/2517c5fc-d9cf-11e7-9504-59efdb70e12f.

- Higonnet, A. 1997. “Private Museums, Public Leadership: Isabella Steward Gardner and the Art of Cultural Authority.” In Cultural Leadership in America: Art Matronage and Patronage, edited by W. M. Corn, 79–92. Boston: Trustees of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Kalb Cosmo, L. 2021. “Private Museums in Twenty-First Century Europe.” In Museums, Collections and Society.Yearbook 2020, edited by H. O’Farrell and P. ter Keurs, 31–58. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Kolbe, K. 2023. “The Art of (Self) Legitimization: How Private Museums Help Their Founders Claim Legitimacy As Elite Actors.” Socio-Economic Review. https://academic.oup.com/ser/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ser/mwad051/7266766.

- Kolbe, K. J., O. Velthuis, J. Aengenheyster, A. Friedmann Rozenbaum, and M. Zhang. 2022. “The Global Rise of Private Art Museums a Literature Review.” Poetics 95:101712. July. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2022.101712.

- Kuesel, C. 2019. “A Fugitive Russian Billionaire’s Missing Art Trove Was Discovered Near Moscow.” Artsy, November 12. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-fugitive-russian-billionaires-missing-art-trove-discovered-moscow.

- Kunst, A. 2012. “Collectie Scheringa Naar Hans Melchers.” Tubantia, March 8. https://www.tubantia.nl/achterhoek/collectie-scheringa-naar-hans-melchers~a4bf84fb/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F.

- Larry’s List. 2015. Private Art Museum Report. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications.

- Larry’s List. 2023. Private Art Museum Report. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications.

- Lindqvist, K. 2012. “Museum Finances: Challenges Beyond Economic Crises.” Museum Management & Curatorship 27 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2012.644693.

- Martí, S. 2015. “Time Running Out for Casa Daros in Rio.” The Art Newspaper, June 16. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2015/06/16/time-running-out-for-casa-daros-in-rio.

- Martin, W. 2019. “Promsvyazbank Intruded into the Married Life of Alexey Ananyev.” Medium, August 28. https://medium.com/@globalbankinghouse/promsvyazbank-intruded-into-the-married-life-of-alexey-ananyev-bf976540a93a.

- Meier, S., and B. S. Frey. 2003. “Private Faces in Public Places: A Case Study of the New Beyeler Art Museum.” In Arts & Economics, edited by B. S. Frey, 95–104. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Michalska, J. 2016. “Austria’s Essl Museum to Shut Its Doors After 17 Years.” The Art Newspaper, April 5. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2016/04/05/austrias-essl-museum-to-shut-its-doors-after-17-years.

- Miranda, C. A. 2019. “What’s Next for Nonprofit Museums After the Closing of the Marciano Art Foundation?” Los Angeles Times, November 8. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2019-11-08/marciano-art-foundation-closing-fallout-museum-union-drive.

- Moynihan, C. 2019. “Marciano Art Foundation Lays off Employees Trying to Unionize.” The New York Times, November 6. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/arts/design/marciano-art-foundation-layoffs-union.html.

- Mustedanagic, A. 2014. “Hallen Für Neue Kunst Ziehen von Schaffhausen Nach Basel Um.” TagesWoche, June 6. https://tageswoche.ch/kultur/hallen-fuer-neue-kunst-ziehen-von-schaffhausen-nach-basel-um/index.html.

- Perman, S. 2020. “Inside the Marciano Art Foundation’s Spectacular Shutdown.” Los Angeles Times, February 16. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-02-16/la-et-cm-marciano-art-foundation-story-behind-the-closure.

- Schuster, J. M. 1998. “Neither Public nor Private: The Hybridization of Museums.” Journal of Cultural Economics 22 (2/3): 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007553902169.

- Szczesniak, P. 2015. “Ruth Schmidheinys Casa Daros in Rio de Janeiro Schliesst.” Tages-Anzeiger, December 15.

- Velthuis, O. 2005. Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton Studies in Cultural Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Velthuis, O., K. J. Kolbe, J. Aengenheyster, A. Friedmann Rozenbaum, M. Gera, and M. Zhang. 2023. “Beyond the Global Boom: Private Art Museums in the 21st Century.” https://privatemuseumresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Private-Museum-Report_UvA_Beyond-the-Global-Boom_2023.pdf.

- Vogel, S. B. 2015. “Francesca Habsburgs Tauchgänge.” Die Presse, December 12. https://www.diepresse.com/4886162/francesca-habsburgs-tauchgaenge.

- Walker, G. S. 2019. The Private Collector’s Museum: Public Good versus Private Gain. New York: Routledge.

- Wensink, H., and P. de Witt Wijnen. 2009. “ABN Amro Legt Beslag Op Collectie Scheringa Museum.” NRC Handelsblad, October 20. https://web.archive.org/web/20091021205502/http://www.nrc.nl/economie/DSB/article2392306.ece/ABN_Amro_legt_beslag_op_collectie_Scheringa_Museum.