ABSTRACT

To advance the understanding of the nature and dynamics of creative entrepreneurship in specific contexts, this paper explores how creative entrepreneurship both shapes and is shaped by its peripheral context. This paper adds to the growing work that is helping us understand that when looking at the periphery through the lens of cultural and creative practice we find a much more nuanced set of relations between place and practice. We focus on geographically separate regions facing the same obstacles of geographic peripherality. Underpinning the findings are semi-structured interviews reflecting the experience of creative entrepreneurs in North East Iceland, Västernorrland in Mid Sweden and the western region of Ireland. While we recognise that problems still exist in the creative industries policy domain, we argue that policy supports would be best designed in line with the characteristics of the sector in particular places. This work also helps to develop knowledge of the multifaceted role of the creative entrepreneur in peripheral societies and economies.

1. Introduction

For over a decade, the role of culture and creativity in the peripheral context has been the subject of our dedicated focus, and it has been rewarding to witness a surge in scholarly attention to this field (Audretsch and Belitski Citation2021; Eder Citation2019; Glückler Citation2014; Grabher Citation2018; Hautala and Jauhiainen Citation2019; Matarasso Citation2019; Power and Collins Citation2021; Pugh and Dubois Citation2021). The discipline of economic geography lends itself perfectly as an analytical lens to enhance our comprehension of creative practice, with creative practice in peripheral settings emerging as an exemplary case study. As we intend to elucidate in the ensuing sections, creativity in the periphery mirrors many attributes of its urban equivalent but maintains a more profound connection to its geography. This geography is both a source of opportunity and constraint.

Traditionally, peripheral regions have been associated with challenges such as geographical remoteness, limited access to resources, and smaller markets (Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022). However, recent literature has increasingly highlighted the unique advantages of these regions, including a wellspring of inspiration, spaces for experimentation, and a conducive environment for nurturing stronger social bonds (Eder Citation2019; Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015). These benefits tend to particularly favour creative enterprises, thus making these enterprises the prime focus of our study.

In an ever-globalising world, digitalisation and emerging technologies are reshaping the dynamics of creativity in peripheral settings. Peripheral regions are progressively integrating into the broader digital landscape, transcending traditional spatial constraints (Malecki and Moriset Citation2008). These advancements present a host of new opportunities, as well as challenges, for creative entrepreneurship in these areas. As the digital divide narrows, it is critical to investigate the evolving role of creative entrepreneurs within this transformed landscape (Tura and Harmaakorpi Citation2005).

Emerging from this backdrop, this paper aims to unravel the characteristics of creative and cultural entrepreneurs, with the objective of precisely evaluating the role of the creative sector in the socio-economic development of non-urban regions. We place a specific emphasis on entrepreneurs due to their acknowledged capacity as change agents who seize opportunities and drive local development (Andersson and Henrekson Citation2014; Raposo et al. Citation2011). This focus also stems from the pressing need for economic activities in peripheral regions to transition from traditional resource-based development to discover novel sources of economic competitiveness, such as knowledge economies (Petrov Citation2014).

The remainder of the paper will delve into the emerging literature on creative and cultural entrepreneurship in peripheral regions, outline the research data and selection framework for participants from peripheral regions in Ireland, Sweden, and Iceland, and discuss the unique characteristics of the creative and cultural entrepreneurs identified. We will also reflect on how these characteristics influence and are influenced by the challenges and opportunities of entrepreneurship in peripheral locations. The paper will culminate with recommendations for future research in this emergent field.

2. Creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions

Our literature review is split into two sections. The first looks at traits of entrepreneurialism. Recognising the vast amount of work carried out in this area from the seminal contributions of McClelland (Citation1961) to the work of Alvarez and Busenitz (Citation2001) on entrepreneurs’ ability to leverage and organise resources in certain ways, our focus is on how these traits can be recognised in the cultural and creative industries sector. Our second section pays particular attention to the geographic context of entrepreneurial endeavour. Here, the work of Mack and Mayer (Citation2015) that defines entrepreneurial ecosystems as interacting components that foster regional growth is important. We set out to narrow the focus on how this kind of activity manifests in the periphery with a particular focus on cultural and creative industries (see Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015).

2.1. Creative entrepreneurship

Creative entrepreneurship, the overlap between artistic flair, business savvy, and the innovative mindset, is gaining acknowledgment as a powerful engine of economic expansion, notably in the area of regional development (Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022; Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015). The crux of creative entrepreneurship revolves around the capacity to identify and harness opportunities within their surroundings (Florida Citation2014). The distinguishing factor of these entrepreneurs compared to traditional ones lies in their creative prowess and its application in the formation and execution of imaginative business concepts (Eder Citation2019; Ellmeier Citation2003). This fusion of creative talent with entrepreneurial ventures is instrumental in sustaining and expanding creative and cultural sectors (Coulson Citation2012).

Bilton and Cummings (Citation2010) see the triumph of creative entrepreneurs as reliant on their proficiency in balancing creativity and commerce, an often-referred-to dichotomy as the ‘double helix’ of creative industries. This fine equilibrium enables them to generate innovative concepts, commercialise them efficiently, and thus contribute to the economic vigour of their areas, be it urban or non-urban (Leick, Gretzinger, and Roddvik Citation2023). Bucking the clichéd image of the solitary genius, creative entrepreneurs often thrive in collective and networked settings (Caves Citation2000; Collins, Mahon, and Murtagh Citation2018; Woods Citation2011). These networks promote the exchange of ideas, resources, and opportunities, cultivating a favourable environment for entrepreneurial activity. In this context, the notion of ‘creative ecosystems,’ which include a diverse set of stakeholders such as artists, institutions, and policymakers, proves crucial in advancing creative entrepreneurship (Sacco and Segre Citation2009).

Moreover, the characteristics of creative entrepreneurs extend beyond personal qualities and business expertise. Social and cultural influences also play a significant part. In their work, Lingo and Tepper (Citation2013) point to how successful creative entrepreneurs navigate both artistic and business spheres, comprehend the languages and norms of both domains, and act as ‘cultural intermediaries’. Contemporary studies offer a more expansive view on these characteristics, emphasising the mutual relationship between creative entrepreneurs and their environments (Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022; Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015). The influence of space and place in fostering entrepreneurial creativity and innovation features prominently in these conversations (Martinus et al. Citation2021). For instance, creative entrepreneurs in peripheral regions harness local resources in distinctive ways, revealing the close connection between their creativity and their locale (Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022; Pato Citation2020).

The effect of physical space on creative entrepreneurs is demonstrated by the rising popularity of coworking spaces. A recent study by Mariotti, Akhavan, and Rossi (Citation2023) displayed a clear preference for these spaces in both urban and peripheral regions in Italy. This preference signals that the physical environment can play a pivotal role in promoting creative entrepreneurship and spurring innovation. In addition, the transformative role of creative entrepreneurs as disruptors is accentuated, especially their ability to function on the margins of established sectors and ignite innovation (Domareski-Ruiz et al. Citation2020; Eder Citation2019). This vibrant creativity is particularly impactful in peripheral regions, highlighting the need for supportive infrastructures to nurture and leverage this potential (Eder Citation2019).

However, the challenges faced in creative entrepreneurship, notably the friction between creative integrity and commercial viability, are significant (Domareski-Ruiz et al. Citation2020). Therefore, promoting creative entrepreneurship requires a deep understanding of these hurdles and the provision of customised support mechanisms. This strategy enables creative entrepreneurs to strike a harmonious balance and prosper in their endeavours (Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015).

The traits of creative entrepreneurs are key to catalysing growth and development, particularly in peripheral regions. A more in-depth grasp of these nuanced attributes, their preferences (such as their propensity towards coworking spaces more general disposition towards collaboration), and their reciprocal relationship with their environment can guide the formulation of policies and programs to support creative entrepreneurship (Mariotti, Akhavan, and Rossi Citation2023). These endeavours can harness the transformative potential of creative entrepreneurs to fuel economic growth, innovation, and cultural vibrancy, particularly in peripheral regions.

In their work, Leick, Gretzinger, and Roddvik (Citation2023) draw from resources-based theories, the concept of network embeddedness, and a process view on entrepreneurship to challenge the idea that creative entrepreneurship is primarily an urban phenomenon. Their theoretical framework sheds light on how creative entrepreneurship arises and grows in non-urban locales, underscoring the role of multiple network embeddedness and resource-exchange configurations.

Indeed, creative entrepreneurs display the ability to spot and capitalise on opportunities within their environments. However, their distinction from conventional entrepreneurs lies in their distinct creative skills and application of these talents in generating and implementing innovative business concepts (Ellmeier Citation2003). The investigation into creative-design entrepreneurs on Norway’s Lofoten Islands (Leick, Gretzinger, and Roddvik Citation2023) exemplifies this, suggesting that creative entrepreneurs can become locally embedded in non-urban places through various resource-exchange combinations with diverse networks. This approach fuels the growth and sustainability of creative and cultural industries (Coulson Citation2012), even in peripheral regions.

2.2. The role of the periphery in creative entrepreneurship

Recent times have borne witness to a paradigm shift in how we perceive the role of peripheral regions as sites of creative entrepreneurship. Traditional views that confined peripheral regions to a receptive role are making way for progressive perspectives that see them as critical contributors (Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022). This shift stems from acknowledging the unique potentialities these regions offer, often laden with rich cultural heritage, local wisdom, and distinctive resources, potent to ignite innovative business ventures. Coupled with the generally reduced living and operating costs in these areas, peripheral regions emerge as attractive arenas for entrepreneurial endeavours (Eder Citation2019; Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015).

Power and Collins (Citation2021) study of Galway, Ireland, is a good example of this emerging view. They highlight the inception of a vibrant industry cluster, infused with culture, in a region often discounted due to its peripheral status. The birth of this creative hub there owes much to a diverse cast of stakeholders – postcolonial activists, Irish language advocates, Hollywood directors, to local politicians. In this case study, Galway stands as a symbol of how the periphery can exploit its innate cultural, communal, and linguistic endowments to fuel a prospering creative sector.

Moreover, the contribution of the periphery to creative entrepreneurship surpasses the mere perks offered by location. The symbiotic interaction between entrepreneurs and their environment considerably shapes entrepreneurial endeavours, emphasising the strategic significance of place (Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015). This interplay is evident in our case study regions, the West of Ireland, North East Iceland, and Mid Sweden, where unique regional dynamics considerably propel entrepreneurial activities within creative and cultural industries.

As our comprehension evolves, the term ‘peripheral creative entrepreneurship’ can begin to suggest scenarios where peripheral regions actively propel the expansion of creative enterprises. This development promises to rejuvenate peripheral regions and position them as leaders in economic and cultural evolution (Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022). Further, the social capital inherent to these peripheral areas, characterised by strong social bonds and networks, can foster an environment conducive to creative entrepreneurs, contributing to the success of their ventures (Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015).

Further investigation is required to gauge the influence of social and cultural factors on creative entrepreneurship in peripheral settings. Given the significant role that social and cultural dynamics play in creative entrepreneurship, a deeper understanding of these elements could help illuminate how they shape creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions (Florida Citation2014; Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015). There is a need for a multifaceted understanding of creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions, emphasising the unique traits of creative entrepreneurs and the dynamic and influential role of the periphery. Important also is the role of institutions and policies that help or hinder these dynamics. In this regard, the role of institutions and policymakers is instrumental in creating conducive environments for the growth and sustainability of creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions (Eder Citation2019).

Moreover, the future of creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions also rests upon the shoulders of entrepreneurs who have the ability to capitalise on unique regional resources and opportunities (Boschma Citation2015; Glückler, Shearmur, and Martinus Citation2022). Considering ongoing global transformations like digitalisation, modern work practices, and recent advancements in AI, understanding their impact on creative entrepreneurship within peripheral regions becomes critical. Digital technologies gradually blur the line between core and periphery, presenting novel opportunities and challenges for creative entrepreneurship in these regions. Given the profound role of social and cultural elements in creative entrepreneurship, a deeper examination of these aspects in peripheral contexts becomes essential. A more detailed understanding of these dynamics can enhance our comprehension of how cultural and social dynamics influence creative entrepreneurship in these settings.

Nevertheless, questions remain, one of those meriting further scrutiny is how creative entrepreneurs engage with their peripheral milieu. Specifically, a detailed understanding is necessary on how the attributes of creative entrepreneurs interact with the specific characteristics of the periphery, influencing the nature of creative entrepreneurial activities. Furthermore, empirical inquiries probing how creative entrepreneurs explore and leverage the unique opportunities and challenges characteristic of the periphery are still nascent. Our intention is that the case study of these three regions can help deliver invaluable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and academics aiming to nurture creative entrepreneurship within peripheral regions. Understanding creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions is a complex, multifaceted issue. The above highlights the need for further research in this area, to foster more comprehensive, nuanced, and context-specific explorations of creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions. Our hope is that such future research will contribute towards building resilient, sustainable, and vibrant peripheral regions driven by creative entrepreneurship.

3. Definitions, data and methods

This research adopts a qualitative approach to scrutinise subjective experiences, aiming to shed light on new insights (Maynard Citation1994; Robson Citation2011). Semi-structured interviews were conducted in three peripheral regions that were strategically selected due to their unique but comparable socioeconomic and institutional contexts: North East Iceland (comprising 13 municipalities), Västernorrland county in Mid Sweden with seven municipalities, and the western region of Ireland (encompassing seven counties under the remit of the Western Development Commission).

All three regions were represented as part of the INTERREG/Northern Periphery and Arctic (NPA) funded project entitled ‘Creative Momentum’. Under the tagline: ‘Make it local; make it global’ the project had a shared vision that good ideas should transcend distance and that creativity not be bounded by geography. Running from 2016 to 2019, it was led by the Western Development Commission in Ireland and supported by researchers at the University of Galway. Through a number of initiatives, the project provided enterprise development and market expansion spaces, services and supports with a transnational focus.

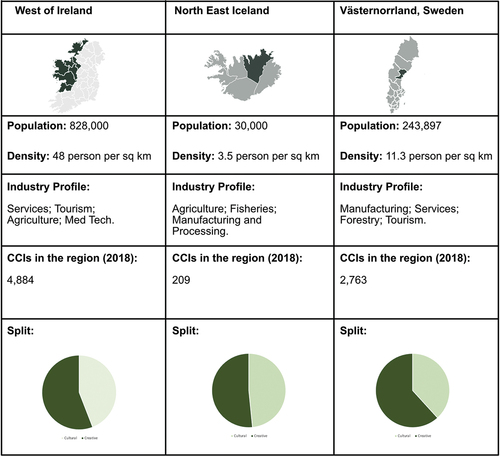

Our case study regions share common characteristics of peripheral regions as per the Northern Periphery and Arctic (NPA) programme’s definition, which includes low population density, limited accessibility, economic diversity challenges, abundant natural resources, and high impacts of climate change (NPA Citation2016). A brief socio-economic profile of each region, providing insight into the rates of self-employment, the nature of (creative) entrepreneurship in these regions, and other pertinent institutional and economic contexts is provided in .

Figure 1. A socioeconomic profile of the case study regions.

The creative economy and its workforce are diverse, comprising numerous sub-sectors, from performing arts and publishing to film and fashion (Hui Citation2007; The Work Foundation Citation2007). Entrepreneurship within this creative ecosystem has been variously defined, and the terminology is still being refined (Essig Citation2017; Hausmann and Heinze Citation2016; HKU Citation2010; Rae Citation2004). This study aligns with Hausmann and Heinze’s (Citation2016) framing of creative entrepreneurship as the ‘discovery, evaluation and exploitation of an entrepreneurial opportunity’ (11). Interview participants were selected based on this characteristic, operating either in ‘cultural’ or ‘creative’ domains within the broadly conceived creative economy (see for a distinction of creative pursuits).

Table 1. Creative industries typology.

Despite the challenge that entrepreneurs do not always fit neatly into categories, attempts were made to classify participants based on their primary entrepreneurial domain, facilitating data collection and ensuring a balanced representation across the creative industries.

Sampling was conducted using a purposive strategy, wherein entrepreneurs with a specific focus on either ‘cultural’ or ‘creative’ domains were sought. The sample was further refined through snowball sampling, with interviewees suggesting other potential participants. This strategy allowed for the collection of rich, in-depth data, albeit with the recognition that the relatively small sample size may limit the generalisability of the findings. In total, 16 semi-structured interviews were conducted between 2017 and 2019. The majority were conducted face-to-face (11), with the remainder taking place over the phone or online (5). The sample was evenly split between creative and cultural industries (see ).

Table 2. Breakdown of interviews.

Interviews were guided by a range of themes including the nature of the company; resources; distribution; revenue streams/investment; management/organisation; networks; customers/markets; regional factors; inspiration; and support schemes/policy. Despite the focus on three distinct regions, the research is exploratory in nature and does not intend to propose blanket generalisations about peripheral creative and cultural entrepreneurship. Instead, it seeks to identify patterns that can stimulate future debate and research.

4. Peripheral regional development and characteristics of the creative and cultural entrepreneur

4.1. Adaptable

Creative and cultural entrepreneurs strongly display the ability to adapt and take on a number of roles that require different skillsets. Research discussed in previous sections highlighted how the growth of peripheral enterprises is limited by a small local market. We argue that being flexible and having the ability to take on a number of different types of work is a response to this. Adaptability appears to be a survival strategy. For example, a photographer based in North East Iceland notes that in the region you need to have the skills to work on a diverse range of projects, from family portraits, advertising, documentary to event photography (Interview 10, Creative, North East Iceland). Another entrepreneur based in Mid Sweden describes their main work as web development, but they also work on web design, graphic design, e-learning, photography, and filming (Interview 8, Creative, Mid Sweden). A games entrepreneur describes how they develop many types of games targeting different consumer groups (Interview 15, Cultural, West of Ireland).

Creative and cultural entrepreneurs also combine their creative profession with work in other sectors to ensure a sustainable living in the face of small local markets. For example, two cultural entrepreneurs interviewed previously worked in teaching before moving towards entrepreneurship as a way to focus on their creative practice full-time. They also tap into other industry sectors, most notably tourism from our evidence. They may target recreational tourists or business visitors. For example, one product design entrepreneur describes their main market:

Companies that buy gifts for their representation … that is a good customer relationship … quite big too … We also have weekend tourists who might come for restaurants, theatre … we have a lot of tourists who like nature too, who go hiking and skiing. (Interview 4, Creative, Mid Sweden)

Entrepreneurs can also develop cross-overs with other local economy sectors, such as education and the social economy. In Mid-Sweden for example, one cultural entrepreneur runs art classes for people with special needs, but also links to the local tourist market by providing residential courses.

Adaptability also plays out in relation to creative practice. Creative entrepreneurs focus on certain inspirations to balance creative and commercial goals. Inspiration can also be driven by a commercial imperative and the tension between a creative and commercial outlook is often approached pragmatically. Some entrepreneurs focus on areas of inspiration that produce content or products that have more commercial value, but are clear that they still remain driven and focused on their primary, core inspirations. A textile designer from North East Iceland describes how they target a growing consumer market, but remain primarily driven by their original motivation, which is to promote and preserve Icelandic traditions. For example: ‘ … because of the growth in tourism here, tourists are my main customer … I am focused on that. But I am also loyal to my roots, that is to focus on our history’ (Interview 1, Creative, North East Iceland). A video production company, based in the west of Ireland originally started producing music videos, but now focuses on promotional videos for a range of clients as their core revenue stream.

However, being adaptable also results in tensions which creative entrepreneurs find difficult to resolve. Not all entrepreneurs have reconciled this tension, and it appears that cultural entrepreneurs have difficulty balancing creative and commercial goals. For example, a performing artist discusses how they teach, and while it might provide more stable, ongoing employment they keep this at a low level because of its impact on their creativity: ‘ … it is also very dangerous … I am mainly an artist and to teach is a completely different thing than to dance. Both intellectual and also in the body’ (Interview 7, Cultural, Mid Sweden). A ceramic artist discusses how they are very reluctant to sell their art. They see it as creating the risk that they will be heavily influenced by others. In this case, teaching provides an effective way to balance this tension: ‘I have always been very cautious about being influenced by others … I started giving classes instead for my living and I developed my art on the side’ (Interview 9, Cultural, Mid Sweden).

4.2. Determined

Determination is a characteristic perhaps more generally associated with entrepreneurs regardless of location. Creative and cultural entrepreneurs display strong determination to apply their creativity to create a livelihood for themselves, and sometimes also others. However, in some cases they are reluctant to identify themselves as entrepreneurs. One interviewee classed as a cultural entrepreneur describes the love of their work as a driver, but does not necessarily see themselves as an entrepreneur:

It is about doing something that you really love … if you love doing something you will work at it as hard as you can. But then you have to be grown up and see is there any way of making a living out of it. (Interview 6, Creative, West of Ireland)

A visual artist describes how they have successfully mobilised local public and private funding, as well as collaborated with other local artists to develop new ideas that have driven projects, highlighting their determination but say: ‘I’m not a good businessman, I don’t have that in me’ (Interview 13, Cultural, North East Iceland). Another creative entrepreneur based in the west of Ireland can be much more closely aligned with entrepreneurship as traditionally understood in terms of discovery and exploitation of an entrepreneurial opportunity:

There was a gap in the market … we were literally working at our kitchen tables for the first year … literally just the two of us doing everything. I then bought my business partner out and moved the business over to Ireland because I wanted to create jobs … I sold my house and put all of the money from the proceeds of that into the business. (Interview 5, Creative, West of Ireland)

Both creative and cultural entrepreneurs display strong determination; however, some, in particular cultural entrepreneurs, are reluctant to identify themselves with entrepreneurship.

4.3. Cooperative

Cooperation is embedded in the practices of cultural and creative entrepreneurs. It appears particularly central in relation to cultural entrepreneurs. Cooperation with other local artists emerges as an effective way to develop new projects. For example, one performing artist working in dance has cooperated with a local cultural organisation and theatre production company on projects. In Mid Sweden, cooperation appears strong within the local design community. The national organisation Svensk Form has an active local branch here, driven by local design entrepreneurs. In the west of Ireland, a cultural entrepreneur in the games sector describes how even in a small market where business opportunities are low, having local competitors is still important as businesses can share talent and knowledge. Another involved in media production comments:

Competition is good … the competitors we have here … we work with them. We bid for the same jobs often. If you have a big job that you can’t handle yourself it’s always good to have some other crew that can help you out and vice-versa … .Competition proves there is a market for what you are doing. (Interview 6, Creative, West of Ireland)

4.4. Stubborn

Creative entrepreneurs appear quite reluctant to relinquish control over their creative outputs. This relates more to core creative tasks rather than wider cultural production activities. More established and internationally successful entrepreneurs displayed a tendency to outsource some work that might have previously been completed in-house, such as tasks requiring business or legal expertise, or creative tasks that are less central to the product or service provided. In the case of one cultural entrepreneur based in the west of Ireland, they describe how they once tried to do paperwork associated with intellectual property themselves, but now work with legal experts (Interview 11, Cultural, West of Ireland). Another example identified is where a textile designer describes how for greater time efficiencies they sometimes work with a graphic designer to covert hand drawings to digital versions (Interview 10, Creative, North East Iceland). This characteristic is not just linked to creative practice, but also enterprise goals. For example, a creative entrepreneur from the West of Ireland felt their key strengths are producing quality work with a personal touch: ‘I would be very particular about getting stuff right and I would spend a long time getting it right … you kind of have to do that, especially when you are starting off too’ (Interview 6, Creative, West of Ireland). This characteristic could potentially impact enterprise growth.

5. Navigating, shaping and being shaped by the peripheral environment

In line with previous work, all interviewees made comment on their location as inspiration. This has long been part of studies of arts practice ‘on the edge’, often coinciding with a dramatic and inspirational landscape. Here, we are interested in seeing how location affects practice beyond aesthetic inspiration and consider how ‘working’ (albeit in a creative pursuit) is affected by an entrepreneur’s location and what that effect can have of the location itself.

5.1. Development patterns shape creative entrepreneurs

Reflective of the determination of creative entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship itself is one way that creative and cultural entrepreneurs navigate the issue of limited jobs in peripheral places. Entrepreneurship is a strategy to facilitate staying at work in the creative and cultural sector full-time. Relatively stable job opportunities are rare in this sector of the peripheral economy. For example, a creative entrepreneur interviewed in the area of software and web design provides an illustrative example. They describe that before they established their company they worked from contract to contract, but had no job security. While their skills were needed, the nature of the industry resulted in only short-term contract jobs being available:

I realised that my kind of expertise is wanted and needed but companies can’t hire someone for a longer period because they are working on something that is for a fixed term so then they don’t need me anymore … it was kind of natural to start my own company because of that. (Interview 8, Creative, Mid Sweden)

Developing your own enterprise gives the opportunity to capture more value from creative work and greater employment stability. A similar pattern is identified among cultural entrepreneurs. One artist based in Mid Sweden specifically identifies that limited local job opportunities were a major reason for starting their business.

Also, reflective of their determination and cooperation, creative and cultural entrepreneurs show a strong ability to mobilise funding and navigate the issue of low availability of investment finance in peripheral regions. They often use multiple-funding sources to support development of a product, idea or project. This can be sourced from social connections such as family, friends, business colleagues but also personal funds such as savings or sale of assets. Local and national sources of funding are also often availed of, such as from local councils, enterprise supports or arts and cultural funds. Crowdfunding also emerged in a number of cases, tied to specific projects or products. Public funding does appear more essential in the case of cultural entrepreneurs. Projects may not go into development without it. A cultural entrepreneur in North East Iceland mentions the importance of government funding that supports an artist’s salary. This has given them the freedom to explore their own creative inspiration: ‘When you get this funding it really helps you grow into something that you want … It has helped me create new projects that I carry on working with independently’ (Interview 14, Cultural, North East Iceland).

5.2. Creative entrepreneurs shape the development of the periphery

Creative entrepreneurs capitalise on and value ‘soft’ resources, such as tradition, nature and amenities within peripheral regions. They help to reinvent these regions and can turn what others can interpret as a disadvantage into an advantage.

Peripheral regions generally have low population densities and this emerges as an advantage for creative and cultural entrepreneurs based here. It can provide creative freedom. For example, a performing artist describes how they spent time in Stockholm but this was not the correct environment to support their creativity:

I think the environment of Stockholm … it was too crowded for me. I think it maybe held me back a bit … so many creative people, so many, there is no need for more creation, but here there is … space. It is not crowded … with people … or too many creative ideas. (Interview 7, Cultural, Mid Sweden)

In this example, the local creative community is small, but also accessible, developing a good general awareness of its composition, sub-communities and meeting places can be done with ease.

More positive associations with the peripheral places can have a constructive impact on the entrepreneurial environment. The cooperative nature of creative entrepreneurs can impact this. For example, a games entrepreneur based in the west of Ireland described the positive impact that a well-known games developer moving to the region has had on it. This helped to highlight and increase interest in a handful of existing, indigenous games companies. It also helped to connect existing companies with high-quality games industry networks. The same entrepreneur describes how networks are vital. Building networks needs an investment of time and financial resources such as attending key industry events. The opportunity to connect through an established game developer helps to break through the crowd more quickly.

It also emerged that without first-hand experience in a region, soft factors can impact hard factors and how their presence is perceived. A place’s image may not necessarily be reflective of reality. For example, one cultural entrepreneur in games development based in the west of Ireland argued that the region is perceived too often as a quaint, traditional place, but they see it as a modern economy with a good talent pool of software engineers and developers. The perception of other places can also attract entrepreneurs away from the periphery. For example, a games developer based in the west of Ireland compares the funding environment in Ireland and Northern Ireland. They highlight the more comprehensive supports available in Northern Ireland that aim to develop the sector because of its job creation potential.

Creative entrepreneurs play a role in re-shaping the periphery by harnessing opportunities, such as building businesses around local heritage and culture. Evidence of this is found from both the creative and cultural entrepreneurs interviewed for this research. For example, a textile designer based in North East Iceland describes how their designs are inspired by food heritage, in particular Icelandic food heritage. Inspiration from the natural world, such as landscape, flora and fauna, emerges as a strong theme across creative and cultural sub-sectors, with a number of entrepreneurs interviewed specifically identifying with this area. While peripheral environment and traditions are a creative resource, this is not the only source of inspiration. Other commonly cited areas of inspiration are travel and human behaviour. Also while local traditions and nature can be used as a creative resource and for inspiration, wider traditions nationally, as well as in other nations, can also be drawn upon. Inspiration is not only creative, but also can provide motivation for entrepreneurship, such as from another inventive business or entrepreneurs in their own sector, as well as other sectors of creative industries, in particular music, visual and performing arts.

Other ‘soft’ factors emerged from our research and are worth further investigation. Trust appears to be an essential resource in peripheral entrepreneur relationships, both with business colleagues and clients. The value of trust is also consciously recognised, actively built and preserved. The relative importance of amenities, such as local heritage and landscape, also merits further analysis in the creative and cultural entrepreneurship context.

6. Entrepreneur by default or design? Discussion and conclusion

This research helps shed some light on the complex dynamics of creative entrepreneurship within peripheral regions, revealing both its multi-faceted nature and its potential as a key driver for regional development. Our work, while exploratory in nature, builds upon the foundational scholarship in this area (Bell and Jayne Citation2010; Bennett, McGuire, and Rahman Citation2015; Collins, Mahon, and Murtagh Citation2018; Glückler and Eckhardt Citation2022; Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2015; Luckman Citation2012) and contributes several critical observations that we anticipate will catalyse further debate and research.

Four key attributes of creative entrepreneurs emerged from our analysis – determination, adaptability, a cooperative spirit, and a protective stance towards creative autonomy. These traits mirror findings from Shane and Venkataraman’s (Citation2000) work on entrepreneurial opportunity and Maynard’s (Citation1994) exploration of the entrepreneurial mindset. These qualities are integral for entrepreneurs operating in peripheral regions characterised by limited job prospects, heightened migration, and other barriers to economic growth (NPA Citation2016).

A significant paradox inherent in creative entrepreneurship, particularly in peripheral settings, is the struggle between maintaining creative control and fostering business growth. This reflects findings by Hausmann and Heinze (Citation2016) and Essig (Citation2017), who noted this delicate balance in creative ventures. Our study underscores the role of this balance, especially pronounced in peripheral settings, which may further distinguish peripheral creative entrepreneurship from more urban manifestations. What needs to be better understood is how commercialisation is viewed differently in the periphery. This allied with the conundrum faced by all creatives on the commercial versus creative divide therefore takes on a slightly different nuance in peripheral places.

Moreover, creative entrepreneurs in our study demonstrated a profound connection to their peripheral environment, both as a source of inspiration and as a distinctive marker for their products in the marketplace. This finding echoes Petrov’s (Citation2014) work highlighting the inherent value of peripheral settings for creative work. Such locational attachments can potentially offer peripheral creative entrepreneurs a competitive advantage, while also contributing to the place’s cultural vibrancy and identity, as suggested by Florida (Citation2002).

Examining the intersection of peripherality and entrepreneurship through our study advances the heuristic framework proposed by Glückler and Eckhardt (Citation2022). We agree with their assertion that the core-periphery relations are not fixed but are in fact fluid, dependent on a multitude of factors such as the industry’s stage of growth and the unique opportunities that peripheral regions may offer (Andersson and Henrekson Citation2014; Raposo et al. Citation2011). This research challenges conventional, linear models of entrepreneurship, emphasising its inherent dynamism and the pivotal role of individual motivations and personal aspirations (Drucker Citation1985). The concept of ‘lifestyle’ entrepreneurship, often perceived as a desire to ‘stay still,’ appears to be more pronounced in peripheral regions. This aligns with the work of Petrov (Citation2014), who notes that peripheral areas may provide greater creative freedom.

We therefore add to Bell and Jayne (Citation2010), Luckman (Citation2012), and Bennett, McGuire, and Rahman (Citation2015) and their call for a more tailored policy approach to supporting the unique needs of creative and cultural entrepreneurs in peripheral regions. Recognising the creative sector’s potential to spur sustainable development in peripheral regions, we also stress the imperative for continued, in-depth investigations in this area.

In light of these observations, we propose that future research should delve deeper into the intersectionality of creative entrepreneurship and peripherality. Additional studies could explore the dynamics of digital technology’s influence on creative entrepreneurship in peripheral regions, or the different challenges faced by peripheral creative entrepreneurs compared to their urban counterparts. Moreover, the importance of peripherality as a unique competitive advantage, creative inspiration, and defining marker of creative goods, raises further questions about the reciprocity of the relationship between creative entrepreneurs and their peripheral settings. All of which has been made more prescient by the shifting work practices resulting from the COVID pandemic.

A comprehensive understanding of the distinctive attributes and contributions of creative entrepreneurs in peripheral regions could be invaluable in informing future policies, initiatives, and support systems. A place-specific approach to entrepreneurship, which recognises the unique characteristics of peripheral regions, would potentially enhance both the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the broader regional development. A key question to explore is the sustainability of peripheral regions, and how creative entrepreneurship can be leveraged to address this critical issue. Through this exploratory study, we argue for the dynamic nature of peripherality and entrepreneurship, providing a platform for a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. We anticipate that our observations will stimulate further research and debate in the burgeoning field of peripheral creative entrepreneurship, a terrain ripe for continued investigation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Patrick Collins

Patrick Collins is a Senior Lecturer in Economic Geography at the University of Galway. Through a number of EU funded projects, Pat has sought to better understand the relationship between culture, creativity and production as well as identifying the unique role played by Geography. He is currently Director of the newly formed UrbanLab Galway at the University of Galway.

Aisling Murtagh

Aisling Murtagh is a Postdoctoral Researcher with the RURALIZATION project at the Rural Studies Centre within the Discipline of Geography at the University of Galway, Ireland. Her current research examines the issues of rural regeneration and generational renewal. She has worked on a number of rural development related national and European projects in areas including creative industries, short food supply chains and food cooperatives. She also worked with Ireland’s National Rural Network as Research and Development Officer where her work particularly focused on the LEADER programme.

References

- Alvarez, S. A., and L. W. Busenitz. 2001. “The Entrepreneurship of Resource-Based Theory.” Journal of Management 27 (6): 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700609.

- Andersson, M., and M. Henrekson. 2014. Local Competitiveness Fostered through Local Institutions for Entrepreneurship (IFN Working Paper No. 1020). Institute for Industrial Economics. http://www.ifn.se/wfiles/wp/wp1020.pdf.

- Audretsch, D. B., and M. Belitski. 2021. “Towards an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Typology for Regional Economic Development: The Role of Creative Class and Entrepreneurship.” Regional Studies 55 (4): 735–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1854711.

- Bell, D. 2015. “Cottage Economy: The ‘Ruralness’ of Rural Cultural Industries.” In The Routledge Companion to Cultural Industries, edited by K. Oakley and J. O’Connor, 222–231. London: Routledge.

- Bell, D., and M. Jayne. 2010. “The Creative Countryside: Policy and Practice in the UK Rural Cultural Economy.” Journal of Rural Studies 26 (3): 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.01.001.

- Bennett, S., S. McGuire, and R. Rahman. 2015. “Living Hand to Mouth: Why the Bohemian Lifestyle Does Not Lead to Wealth Creation in Peripheral Regions?” European Planning Studies 23 (12): 2390–2403. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.988010.

- Bilton, C., and S. Cummings. 2010. Creative Strategy: Reconnecting Business and Innovation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Boschma, R. 2015. “Towards an Evolutionary Perspective on Regional Resilience.” Regional Studies 49 (5): 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.959481.

- Caves, R. E. 2000. Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. London: Harvard University Press.

- Collins, P., M. Mahon, and A. Murtagh. 2018. “Creative Industries and the Creative Economy of the West of Ireland: Evidence of Sustainable Change?” Creative Industries Journal 11 (1): 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2018.1434359.

- Coulson, S. 2012. “Collaborating in a Competitive World: Musicians’ Working Lives and Understandings of Entrepreneurship.” Work, Employment and Society 26 (2): 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011432919.

- Domareski-Ruiz, T. C., A. F. Chim-Miki, E. Añaña, and F. A. Dos Anjos. 2020. “Impacts of Mega-Events on Competitiveness and Corruption Perception in South American Countries.” Tourism & Management Studies 16 (2): 7–15. https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2020.160201.

- Drucker, P. F. 1985. Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Practice and Principles. New York: Harper & Row.

- Eder, J. 2019. “Peripheralization and Knowledge Bases in Austria: Towards a New Regional Typology.” European Planning Studies 27 (1): 42–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1541966.

- Ellmeier, A. 2003. “Cultural Entrepreneurialism: On the Changing Relationship Between the Arts, Culture and Employment1.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 9 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028663032000069158a.

- Essig, L. 2017. “Theorizing Cultural Entrepreneurship: An Integrative Framework for Exploring the Creative Industries.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 29 (3): 21–44.

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: New York Books.

- Florida, R. 2014. The Rise of the Creative Class Revisited. New York: Basic Books.

- Glückler, J. 2014. “Bridging the Gap? The Location Behaviour of Creative Knowledge Workers in Germany.” Urban Studies 51 (4): 761–779.

- Glückler, J., and Y. Eckhardt. 2022. “Illicit Innovation and Institutional Folding: From Purity to Naturalness in the Bavarian Brewing Industry.” Journal of Economic Geography 22 (3): 605–630. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbab026.

- Glückler, J., R. Shearmur, and K. Martinus. 2022. “Liability or Opportunity? Reconceptualizing the Periphery and Its Role in Innovation.” Journal of Economic Geography: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbac028.

- Grabher, G. 2018. “The Project Ecology of Creative Cities: The Case of Media Cities.” Regional Studies 52 (5): 626–635.

- Harvey, D., H. Hawkins, and N. Thomas. 2012. “Thinking Creative Clusters Beyond the City: People, Places and Networks.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 43 (3): 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.11.010.

- Hausmann, A., and A. Heinze. 2016. “Entrepreneurship in the Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from an Emergent Field.” Artivate 5 (2): 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1353/artv.2016.0005.

- Hautala, J., and J. S. Jauhiainen. 2019. “Creativity-Related Mobilities of Peripheral Artists and Scientists.” Geo Journal 84 (2): 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9866-3.

- HKU. 2010. “The Entrepreneurial Dimension of the Cultural and Creative Industries.” Utrecht: HogeschoolvordeKunsten Utrecht. http://kultur.creative-europe-desk.de/fileadmin/user_upload/The_Entrepreneurial_Dimension_of_the_Cultural_and_Creative_Industries.pdf.

- Hui, D. 2007. “The Creative Industries and Entrepreneurship in East and Southeast Asia.” In Entrepreneurship in the Creative Industries: An International Perspective, edited by C. Henry, 9–29. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Korsgaard, S., A. Anderson, and J. Gaddefors. 2015. “Entrepreneurship and the Business Environment in Peripheral Regions: A Comparison Between Northwest Scotland and South Jutland.” European Planning Studies 23 (11): 2260–2279.

- Leick, B., S. Gretzinger, and I. N. Roddvik. 2023. “Creative Entrepreneurs and Embeddedness in Non-Urban Places: A Resource Exchange and Network Embeddedness Logic.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 29 (5): 1133–1157. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-07-2022-0606.

- Lingo, E. L., and S. J. Tepper. 2013. “Looking Back, Looking Forward: Arts-Based Careers and Creative Work.” Work and Occupations 40 (4): 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888413505229.

- Luckman, S. 2012. “Whose Creative Economy? Geography and the Cultural Economy of Creative Industries.” Progress in Human Geography 36 (5): 541–560.

- Mack, E., and H. Mayer. 2015. “The Evolutionary Dynamics of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems.” Urban Studies 52 (16): 2971–2988.

- Malecki, E. J., and B. Moriset. 2008. The Digital Economy: Business Organization, Production Processes and Regional Developments. London: Routledge.

- Mariotti, I., M. Akhavan, and F. Rossi. 2023. “The Preferred Location of Coworking Spaces in Italy: An Empirical Investigation in Urban and Peripheral Areas.” European Planning Studies 31 (3): 467–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1895080.

- Martinus, K., T. Sigler, I. Iacopini, and B. Derudder. 2021. “The Brokerage Role of Small States and Territories in Global Corporate Networks.” Growth and Change 52 (1): 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12336.

- Matarasso, F. 2019. A Restless Art: How Participation in the Arts Can Change Communities. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

- Maynard, M. 1994. “Methods, Practice and Epistemology: The Debate About Feminism and Research.” In Researching Women’s Lives from a Feminist Perspective, edited by M. Maynard and J. Purvis, 10–26. Cornwall: Taylor and Francis.

- McClelland, D. C. 1961. The Achieving Society. New York: Free Press.

- NPA. 2016. “Northern Periphery and Arctic Cooperation Programme 2014–2020.” Copenhagen: Interreg. http://www.interregnpa.eu/fileadmin/Programme_Documents/Approved_Cooperation_Programme_Jan2016.pdf.

- Pato, L. 2020. “Entrepreneurship and Innovation Towards Rural Development Evidence from a Peripheral Area in Portugal.” European Countryside 12 (2): 209–220. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2020-0012.

- Petrov, A. 2014. “Creative Arctic: Towards Measuring Arctic’s Creative Capital.” The Arctic Yearbook 2014 (1): 149.

- Power, D., and P. Collins. 2021. “Peripheral Visions: The Film and Television Industry in Galway, Ireland.” Industry and Innovation 28 (9): 1150–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2021.1877633.

- Pugh, R., and A. Dubois. 2021. “Peripheries within Economic Geography: Four ‘Problems’ and the Road Ahead of Us.” Journal of Rural Studies 87:267–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.007.

- Rae, D. 2004. “Entrepreneurial Learning: A Practical Model for the Creative Industries.” Education & Training 46 (8/9): 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910410569614.

- Raposo, M., D. Smallbone, K. Balaton, and L. Hortoványi. 2011. Entrepreneurship, Growth and Economic Development: Frontiers in European Entrepreneurship Research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Robson, C. 2011. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner Researchers. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Sacco, P. L., and G. Segre. 2009. “Creativity, Cultural Investment and Local Development: A New Theoretical Framework for Endogenous Growth.” In Growth and Innovation of Competitive Regions: The Role of Internal and External Connections, edited by U. Fratesi and L. Senn, 281–294. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Shane, S., and S. Venkataraman. 2000. “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research.” Academy of Management Review 25 (1): 217–226. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791611.

- Tura, T., and V. Harmaakorpi. 2005. “Social Capital in Building Regional Innovative Capability.” Regional Studies 39 (8): 1111–1125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400500328255.

- Woods, M. 2011. “Winning and Losing: The Changing Geography of Europe’s Rural Areas.” European Urban and Regional Studies 13 (3): 282–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776406065440.

- The Work Foundation. 2007. Staying Ahead: The Economic Performance of the UK’s Creative Industries. London: Department of Culture, Media and Sport.