?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and the resultant negative effects thereof on the environment due to climate change remain a global challenge. In South Africa, passenger vehicles contribute significantly to the amount of CO2 that is emitted into the atmosphere. In an effort to address this challenge, South Africa introduced a CO2 emissions tax from 1 September 2010. The aim of this tax is to make the vehicles on South Africa’s roads more environmentally friendly by influencing consumer behaviour at the point of a new car purchase. This paper considers the effect of this tax by way of a survey that targeted consumers who have bought a new passenger vehicle since the implementation of the tax. The paper aimed to measure consumers’ awareness of and insight into this CO2 emissions tax, as well as to determine whether the CO2 emissions tax influenced their purchasing decision. The results of this survey indicate that most consumers are not aware of the CO2 emissions tax. There is thus evidence to substantiate that the CO2 emissions tax has not achieved its purpose of making South Africa’s fleet of motor vehicles more environmentally friendly by changing consumers’ behaviour through influencing the purchase decision relating to new car sales.

1. Introduction

The pace of global warming is accelerating and the scale of the impact is devastating. The time for action is limited - we are approaching a tipping point beyond which the opportunity to reverse the damage of CO2 emissions will disappear. (Spitzer, Citation2014)

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and their resultant negative effects on the environment remain a global challenge and are a serious threat globally that require a worldwide response (Anjum, Citation2008, p. 1; National Treasury, Citation2010a). The CO2 emissions from passenger vehicles are a contributing factor to this threat. The increase in the global human population leads to an increase in the sales of passenger vehicles annually. In South Africa, between 2009 and 2016, an average of 44 800 new passenger vehicles were sold monthly (Trading Economics, Citation2016).

During 2010, South Africa ranked among the 20 highest CO2 emitting countries globally – measured by absolute CO2 emissions. Furthermore, South Africa is by far the largest CO2 emitter in Africa (US Energy Information Administration, Citation2012). The largest part of South Africa’s Green House Gas (GHG) emissions (about 80%) is produced by the electricity sector, the metals industry and the transport sector (National Treasury, Citation2010a). According to the National Treasury (Citation2013a), the transport sector emissions are responsible for approximately 9% of the country’s total GHG emissions, with road transport being responsible for a large part of this percentage. Road transport emissions are mainly a result of the combustion of fossil fuels (e.g. petrol and diesel) in motor vehicles. The negative impact of motor vehicle transport on the environment far outweighs its positive economic and social impact, including the development of local and international trade relations, and fulfilling the human need for communication and mobility (Ioncică et al, Citation2012).

Globally, the transport sector CO2 emissions represent 23% of the total CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion. Furthermore, the transport sector is responsible for approximately 15% of overall GHG emissions (OECD/ITF, Citation2010; United States Environmental Protection Agency, Citation2014).

Governments’ actions in response to the CO2 emissions threat (specifically related to the CO2 emissions of passenger vehicles) are diverse. Certain countries levy a once-off CO2 emissions tax, while others tax the CO2 emissions of passenger vehicles annually (Walls & Hanson, Citation1996). In South Africa, consumers buying a new passenger vehicle after 1 September 2010 pay a once-off CO2 emissions tax based on the amount of CO2 that the vehicle emits (expressed as grams per kilometre) above a certain threshold (National Treasury, Citation2010b). National Treasury (Citation2010c) is of the view that an all-inclusive and complete approach, encompassing both regulatory interventions and green taxes, is needed to deal with ecological challenges; hence the introduction of the CO2 emissions tax.

The CO2 emissions tax is not merely a revenue-producing instrument by government. This green tax is aimed at both satisfying the ‘polluter pays’ principle (Economics.help, Citation2017), and at influencing and altering consumer behaviour (National Treasury, Citation2010c) by discouraging the acquisition of vehicles that produce high CO2 emissions (Nel & Nienaber, Citation2012). This CO2 emissions tax is added to the cost of passenger vehicles purchased with the primary objective to change the behaviour (purchase decisions) of consumers (National Treasury, Citation2010c). It is, therefore, important to determine and/ or evaluate whether and to what extent the primary objective has been met.

The main objective of this paper is to determine whether the CO2 emissions tax fulfils its primary objective of influencing the behaviour of consumers, buying new motor vehicles, by swaying their purchase decision to a more environmentally friendly passenger vehicle. Two specific research objectives guided the research. In the first instance, to determine whether CO2 emissions tax has altered the purchasing behaviour of consumers buying new motor vehicles. In the second instance, to establish whether consumers buying new motor vehicles are aware of the CO2 emissions tax charged on new motor vehicles and by what means did they become aware of the tax.

With this study, data was collected by means of a survey in order to perform exploratory empirical research to explore whether CO2 emissions tax had an influence on new car purchasing consumer behaviour. The results indicated that the CO2 emissions tax has not achieved its objective of influencing consumers’ behaviour when buying a new car.

From an academic perspective, this exploratory research will contribute to the knowledge regarding the expectations of government and policymakers concerning the implementation of CO2 emissions tax. In addition, the findings are important to motor vehicle manufacturers as well as to dealers in order to assist them in understanding the principles underlying this tax. From a theoretical perspective, this study sought to investigate the ultimate objective of CO2 emissions tax in South Africa, which is to influence consumers’ behaviour when buying a car.

The remainder of the paper will proceed as follows. First the objectives of the study will be presented, followed by the literature review and the development of the hypotheses. Subsequently, the research design, findings and conclusions will be discussed.

2. Literature review

This section provides the foundation for the research and discusses the history of CO2 emissions tax in South Africa; the objective of this tax; as well as vehicle costs and consumer behaviour.

2.1. History of CO2 tax in South Africa

During 2006, National Treasury identified three possible options for reforming the then existing environment-related taxes in the vehicle sector: 1) increasing the general fuel levy; or 2) increasing vehicle customs and excise duties (ad valorem tax); or 3) increasing vehicle licensing fees on fuel inefficient vehicles. All the above proposals served the same common purpose of addressing the impact of vehicle CO2 emissions (National Treasury, Citation2006). The proposal to increase the ad valorem tax was ultimately replaced by the CO2 emissions tax as it is known today.

In the 2009 Budget speech, the Minister of Finance announced a reform of the ad valorem excise duty on motor vehicles (both motor cars and light commercial vehicles) to include a component that links to the specific rate of CO2 emissions per vehicle. This was in line with an earlier proposal by the then Department of Minerals and Energy (in 2004) to encourage the use of more fuel-efficient vehicles through the taxation of ‘gas guzzlers’ – meaning vehicles with a high engine capacity such as double cabs/4 × 4s that are generally not fuel efficient. The South African government stated its intention to introduce environmental taxes and incentives to ensure that economic growth is directed towards a more sustainable path (National Treasury Citation2010b).

According to the National Treasury (Citation2010b), there are close correlations between vehicle engine size, fuel efficiency, and CO2 emissions. It is in this context that the 2009 Budget proposal to tax vehicles’ CO2 emissions was initiated. After consultation with the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa (NAAMSA), it was agreed that the implementation of the proposed vehicle CO2 emissions tax would be reformed into a specific ad valorem tax levied on each new passenger vehicle sold.

This amendment was announced in the 2010 Budget and took effect on 1 September 2010. The industry also requested that the tax be limited to passenger vehicles because there was no data available on CO2 emissions by light commercial vehicles; hence, the 2010 Budget Review only refers to passenger vehicles. In terms of the CO2 emissions tax introduced in 2010, taxpayers purchasing new passenger vehicles became burdened with the additional tax calculated based on the reported actual figure of CO2 emitted by vehicles (expressed as g/km), above a certain threshold (National Treasury, Citation2010c). This tax only became applicable to double cab vehicles from 11 March 2011.

The rates mentioned in Table applied to vehicles attracting CO2 emissions tax (National Treasury, Citation2010c). These amounts were changed for the first time in 2013 (South African Revenue Service, Citation2013) and the amended rates are also conveyed in .

Table 1. Rate of CO2 emissions tax charged.

When the tax was increased in 2013, it resulted in an average price increase for passenger vehicles between 2 and 3% (Droppa, Citation2013).

2.2. Intention of the South African government with the introduction of CO2 emissions tax

Green tax is aimed to satisfy the ‘polluter pays’ principle. When the responsibility for paying the additional tax is isolated to the ultimate user of the vehicle, the behaviour of the consumer may be affected (Kunert & Kuhfeld, Citation2007). Kunert and Kuhfeld (Citation2007) further suggest that consumers may not always be aware of, or at least they do not fully comprehend, the impact of their actions on the environment.

Currently, environmental taxes on passenger vehicles in South Africa consist mainly of a purchase tax (levied on the acquisition of a new vehicle). Klein (Citation2014, p. 38) and Gerlagh et al. (Citation2015, p. 1) revealed that an acquisition tax, based on the CO2 emissions of a motor vehicle, may have reduced vehicle sales which can contribute to the reduction of CO2 emissions of new motor vehicles sold. A purchase tax, when levied at the correct level, is found to be more effective than an ownership or a fuel tax to achieve this goal (Klein, Citation2014, pp. 34-35). Within the South African context, possible indication that CO2 emissions tax does not influence consumer behaviour is that even though South Africa introduced a purchase tax, the sale of certain high-emission vehicles continued to rise subsequent to September 2010 and outperformed the sales of vehicles with lower emissions (Carrim, Citation2014, p. 58). In addition, Barnard (Citation2014) and Ackermann (Citation2014) also revealed that within the South African context, consumer behaviour was not influenced by the introduction of a CO2 emissions tax when a new car was purchased. The failure of the CO2 levy to change consumer behaviour in South Africa could be due to the levy being too low to have a material impact on new vehicle sales. Further increases in usage taxes are not likely to result in a further reduction of CO2 emissions (Nel & Nienaber, Citation2012).

The second form of tax levied on the CO2 emissions of motor vehicles is an annual ownership tax, which is normally charged when the vehicle licence is renewed. Countries that charge ownership tax usually base the amount of tax payable on the engine power, cylinder capacity and weight of motor vehicles, and their fuel consumption. Klein (Citation2014, p. 1) found that with regard to the characteristics of the types of motor vehicles sold, ownership tax did not have a significant effect. It should be noted that short-sighted motor vehicle purchasers will focus on the initial purchase price and might not take the future annual CO2 ownership taxes into account (Klein, Citation2014, p. 5). The ownership tax currently charged in South Africa in the form of an annual licence fee that does not include a CO2 emissions component.

The third type of tax is a CO2 usage tax, which is normally included in the price of petrol and diesel in the form of a fuel levy. Like the CO2 ownership tax, the fuel levy accumulates over the lifetime of a motor vehicle and will be much higher for high-emission motor vehicles with high fuel consumption. Klein (Citation2014, p. 6) found that although a fuel levy does not affect the characteristics of new motor vehicles purchased, it still had an important role to play as it affected the market share of motor vehicles using diesel. The current fuel levy charged in South Africa does not include a levy on CO2 emissions.

When the CO2 emissions tax was introduced in 2010, the National Treasury (Citation2010c) intended to add the cost of the emissions tax to the cost price of the vehicle purchased. However, this intention drew a combination of responses from consumers as well as the South African Automotive Industry. A number of consumers do appreciate the need for change, while others see this tax simply as another income-generating exercise by government (De Siena, Citation2011). According to Nel and Nienaber (Citation2012), the South African Automotive Industry – represented by the Retail Automotive Industry (RMI) and the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa (NAAMSA) – expressed concerns about the possible negative implications of the tax for employment in the vehicle retail, manufacturing and component industries.

The RMI and NAAMSA asked whether the vehicle emissions tax would be effective in reducing CO2 emissions (Automotive Business Review, Citation2010; NAAMSA, Citation2010), particularly in view of the fact that, despite the introduction of the vehicle emissions tax, passenger vehicle sales figures continued to rise during the fourth quarter of 2010 (NAAMSA, Citation2011).

Based on the rates specified in , the actual amount of tax payable due to the introduction of emissions tax may be regarded as relatively small in comparison to the total cost of the vehicle. It could be argued that the effect of the increase in purchase price is relatively low. However, the higher the purchase price of a vehicle (for example, a luxury vehicle), the smaller the percentage taxation is in relation to the total purchase price, as the CO2 emissions remain relatively constant in specific engine sizes. In contrast, the lower the purchase price of a vehicle, the higher the percentage taxation is in relation to the total purchase price (Droppa, Citation2013).

Although it was the intention of the National Treasury that the CO2 emissions tax should not be seen as a revenue-producing instrument, it is interesting to quantify the actual amount received from this tax. Since its introduction, the amounts of CO2 emissions tax as disclosed in have been collected by SARS (South African Revenue Service, Citation2014).

Table 2. Amount of CO2 emissions tax collected by SARS.

The amount of tax, as indicated in , should be interpreted and read together with the number of passenger vehicles sold per month as provided in , bearing in mind that a tax year runs from March to February and that the CO2 emissions tax was only introduced with effect from 1 September 2010.

Table 3. South African new passenger vehicle sales from September 2010 to February 2014.

If we look at it univariately, according to , the amount generated from the CO2 emissions tax declined by R50 million from the 2011/2012 tax year to the 2012/2013 tax year. The number of passenger vehicles sold, however, increased with 53 848 sales for the same period. The amount of CO2 emissions tax collected in 2013/2014 increased in line with the increase in the number of vehicles sold. It is therefore not conclusive from that the cost in the form of CO2 emissions tax had the desired effect on consumer behaviour that the legislator intended.

2.3. Vehicle costs and consumer behaviour

Understanding all the permutations influencing a consumer’s consideration in ultimately making a purchase decision is complex. Brouhle and Khanna (2007, p. 377) argue that one of these considerations is the level of quality a consumer perceives a product to possess, and further suggests that consumers are willing to pay a premium for products that they believe to be of a higher quality than similar offerings. The limiting factor, however, is the consumer’s uncertainty regarding the extent to which the product in consideration is in fact of higher quality than the available alternatives. The consumer therefore needs to be informed of the various factors that could increase the quality of the product under consideration for purchase.

Sheth, Newman and Gross (Citation1991) laid down three fundamental propositions that are applicable to the theory of consumption values and are as follows: (1) Consumer choice is a function of multiple consumption values; (2) Consumption values make various contributions in any given choice situation; and (3) Consumption values are independent.

Lin and Huang (Citation2012) describe the consumption values as being the following:

Functional value (being the primary driver of consumer choice according to Sheth et al., Citation1991).

Social value (the perceived utility derived from an alternative association with one or more specific social groups).

Emotional value (the perceived utility derived from an alternative capacity to arouse feelings or affective states).

Conditional value (the perceived utility derived from an alternative as the result of a specific situation or set of circumstances facing the decision-maker).

Epistemic value (which is defined as the perceived utility derived from an alternative capacity to arouse curiosity, provide novelty, or to satisfy a desire for knowledge).

The notion of being informed is emphasised by Carpenter (Citation2000), who argues that there is a definite link between the level of consumer education relating to the particular purchasing decision and consumer behaviour. Brouhle and Khanna (Citation2007) point out that an increase in the quality of the product ultimately leads to an increase in the price of that specific product, accepting the argument that the more environmentally friendly a product is, the higher its quality. Minton and Rose (Citation1997) found that the intention to act in an environmentally friendly manner is driven by attitude. The more favourable consumer attitudes towards the environment are, the stronger their intentions to stop purchasing from polluting companies and to do their part to reduce their own contribution to pollution (Minton & Rose, Citation1997). This can be summarised as the consumers’ awareness of environmental issues and the resultant effect it has on their response thereto. Kunert and Kuhfeld (Citation2007) are of the opinion that consumers do not entirely comprehend the impact of their own (albeit small) contributions to achieving a more environmentally friendly world and they do not completely understand the effect of their actions (positive or negative) on the environment.

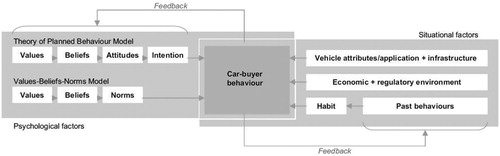

The applicable aspects of consumer behaviour should be contextualised, and made specifically relevant, within the process of purchasing a new passenger vehicle. Lane and Potter (Citation2006) point out that there are numerous aspects that influence new car buyers. The major two of those aspects are situational factors (which include the economic and regulatory environments, vehicle performance and application, and the existing fuel/road infrastructure) and psychological factors (which include attitudes, lifestyle, personality and self-image). Lane and Potter (Citation2006) conclude that environmental considerations have a low priority when consumers are considering, and ultimately deciding, on their new car purchase. It can therefore be expected that there is not a close correlation between environmental considerations and the decision-making process. A graphical presentation of Lane and Potter’s model is presented in .

Figure 1 The Lane and Potter model of factors influencing car buyer behaviour.

Source: Borthwick and Carreno (Citation2012).

These situational factors and psychological factors were further explored in Scotland by Borthwick and Carreno (Citation2012), using a questionnaire. Their study classified respondents (who purchased new motor vehicles) into categories, based on their responses to the significance of situational aspects and psychological concepts. The categories were named (Borthwick & Carreno, Citation2012) No-Greens, Go-With-The-Flow-Greens and Go-Greens, with the percentage representation of the total sample being 27%, 34% and 39% respectively. The different categories, according to Borthwick and Carreno (Citation2012), are summarised in . In each response category, the psychological and situational factors are indicated.

Table 4. Categories of new car purchasers.

The results contained in indicate that No-Greens contain a significantly higher portion of high-income earners than the other two categories, which negates the impact of the financial consideration on the purchasing decision (for higher income earners). At the time of the study, a significantly greater number of Go-Greens already drove vehicles with lower emissions in relation to the other two categories, and present further evidence of Lane and Potter’s (Citation2006) theory that the way in which individuals acted in the past is likely to determine their future conduct.

When the price of a car on offer is considered, Allcot and Wozny (Citation2010) argue that more often than not purchasing decisions are influenced more by the initial price tag than the lifetime costs. The most effective policies in dealing with the CO2 emissions of cars may therefore be those that are applicable when the car is purchased, as the short-sighted approach of the majority of consumers (by not considering the lifetime costs) cannot be changed. The fact that costs play a considerable role confirms the results of Borthwick and Carreno’s study (2012) that suggests income has a major effect on passenger car purchasing decisions; consequently, CO2 emissions tax is expected to influence consumers’ behaviour.

Given the views from literature, this paper endeavours to comprehend consumer behaviour in South Africa relevant to new car purchase decisions.

3. Hypotheses development

Given the conflicting views from literature, this paper and the relevant literature presented in the previous section, the following hypotheses are presented.

3.1. Effect of CO2 emissions tax on taxpayer’s purchase decision

National Treasury (Citation2010c) states the aim of this green tax is to satisfy the ‘polluter pays’ principle and to influence and alter consumer behaviour by discouraging the acquisition of vehicles that produce high CO2 emissions, rather than being merely a revenue-producing instrument by government (Nel & Nienaber, Citation2012). In this light, Lane and Potter (Citation2006) found that environmental considerations have a low priority when consumers are considering, and ultimately deciding on their new car purchase. It can therefore be expected that there is not a high correlation between environmental considerations and the decision-making process. The first hypothesis is therefore:

H1: CO2 emissions tax does not influence the purchasing decision of consumers that are purchasing new cars

3.2. Awareness of CO2 emission tax

Kunert and Kuhfeld (Citation2007) suggest that consumers may not always be aware of, or at least they do not fully comprehend the impact of their actions on the environment. The notion of being informed is emphasised by Carpenter (Citation2000), who argues that there is a definite link between the level of consumer education relating to the particular purchasing decision and consumer behaviour. The second hypothesis is therefore:

H2: Higher awareness of CO2 emissions tax will negatively influence the purchasing decision of consumers that are purchasing new cars

4. Research design

An exploratory empirical study was conducted with the aim of exploring whether the CO2 emissions tax has influenced consumer behaviour as intended by National Treasury.

4.1. Sampling

The target population consisted of persons who purchased a new passenger vehicle or double-cab utility vehicle in 2014 or 2015 in order to examine the effect of CO2 emissions tax on their purchasing decision. The units of analysis were therefore limited to the individuals who made the aforementioned purchases.

Sales representatives at 10 dealerships in Johannesburg and Pretoria (Gauteng Province), and at one dealership in Standerton (Mpumalanga Province) recruited respondents using a convenience sampling approach. The inclusion of the dealerships in both provinces was to have representation of new motor vehicle buyers from both rural and urban regions. Additionally, the researchers recruited approximately 10% of the respondents from their own personal networks using convenience sampling. In total, 306 respondents were surveyed.

4.2. Data collection

Data for the study were collected by means of a self-completed questionnaire. The questionnaire was pre-tested by an experienced survey statistician, two senior academics knowledgeable about CO2 emission tax, and three consumers from the study’s target population. Sales representatives at the aforementioned vehicle dealerships were trained to distribute the questionnaires to qualifying respondents. The sales representatives were also briefed on the meaning and purpose of the questions in the questionnaire and could assist respondents who had queries in this regard.

4.3. Measurement

At request of the participating dealerships, the questionnaire was kept as short as possible to avoid respondent fatigue and to minimise disruptions of the sales processes at the dealerships. The questionnaire was printed as a four-page, A5-sized booklet and included 18 questions, which were all specifically developed for the current research.

The first question asked respondents to indicate the make (e.g., Toyota), range (e.g., Fortuner) and model (e.g., 3.0 D) of the new vehicle they had purchased. This was followed by five categorical questions to determine: (a) whether respondents were aware of the CO2 emission tax charged on the new vehicle at the time they bought the new vehicle; (b) how respondents were informed of this tax; (c) respondents’ awareness of the CO2 emission levels of the new vehicle they had purchased; (d) respondents’ awareness of the fact that CO2 emission tax is charged proportional to the CO2 emission levels from a vehicle; and (e) how respondents became aware of the ZAR amount of the CO2 emissions tax payable on their new vehicle.

The questionnaire further contained six Likert scale statements presented on a five-point scale with scale points ranging from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’. These statements were used to, inter alia, measure respondents’ environmental consciousness; perceptions about the impact of CO2 emissions on the environment; perceptions about the impact of CO2 emission tax on their purchase decisions; and respondents’ perceptions of the fairness and effectiveness of CO2 emission tax.

In addition, the questionnaire contained a forced ranking scale in which respondents had to rank-order the five most important factors from a set of 11 factors that may have influenced their purchase decision.

The questionnaire concluded with demographic questions to determine respondents’ age, race, gender, highest education level attained and gross annual income.

4.4. Ethical considerations

The Research Ethics Committee of the relevant higher educational institution approved the study prior to data collection, and the introduction to the questionnaire contained the normal assurances of anonymity, confidentiality and voluntary participation. Respondents did not receive any incentives to encourage their participation.

4.5. Methods

Taking into account the stated objective of this paper, the data collected were analysed through various statistical tests. By employing Chi-Square tests for independence, the statistical significance of linear relationships between the awareness of the tax, the CO2 emissions level and the calculation method were determined. Furthermore, t-tests and multiple regression analysis were conducted in order to determine whether CO2 taxes and awareness thereof negatively and significantly influences the behaviour of consumers purchasing new cars. A significance level of 1% was employed to determine statistical significance.

5. Findings

5.1. Respondents’ profile

The 306 respondents ranged in age from 18 to 74 years (Mean (M) = 38.4 years; Median (Mdn) = 36.0 years; Standard deviation (SD) = 11.6 years). provides a demographic profile of the respondents in terms of race, gender, highest education level attained and gross annual income.

Table 5. Demographic profile of the respondents.

Respondents were asked to indicate the make (i.e. vehicle brand names), range and model of the new vehicle that they had purchased. The respondents mentioned 23 different makes that cover all segments of the South African passenger vehicle market and range from leading mass-market brands such as Volkswagen, Toyota and Ford to exclusive, niche brands such as Land Rover, Jaguar and Porsche. The three makes mentioned most frequently were Volkswagen (19.02%), Mazda (18.03%) and Ford (17.38%).

5.2. Descriptive statistics

This section provides descriptive statistics on the variables measured in the questionnaire. provides frequency counts on the respondents’ answers to the five categorical questions that dealt with their awareness of, and knowledge about CO2 emission tax on new vehicles.

Table 6. Awareness of, and knowledge about CO2 emission tax on new vehicles.

These results indicate that only 60.1% of respondents were aware of the CO2 emission tax charged on new vehicles at the time they purchased a new vehicle, while 39.9% were unaware. The majority (57.0%) of the respondents who were aware of CO2 emission tax were informed of this tax by the dealer, while a further 36.9% were informed by the media. The majority of respondents (67.3%) were aware of the CO2 emission levels of the vehicle they had purchased. However, respondents were less informed about the exact nature of CO2 emission tax, with only 45.4% indicating that they were aware that CO2 emission tax is directly proportional to the level of CO2 emissions from a vehicle. Most of the respondents (54.3%) indicated that the sales person informed them of the ZAR amount of the CO2 emission tax charged on their new vehicle, while 22.6% indicated that they became aware of this amount from information provided on the sales invoice.

shows a cross-tabulation between responses to questions 2 and 4 in the questionnaire. In question 2, respondents had to provide a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response to the question: ‘At the time you bought the vehicle, were you aware of the CO2 emission tax charged on new vehicles?’ In question 4, respondents had to indicate ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to the question: ‘Are you aware of the CO2 emission level of the vehicle that you purchased?’

Table 7. Awareness of CO2 emission tax versus awareness of the CO2 emission level.

The results in indicate that 88 of the 184 (47.8%) respondents who indicated that they were aware of CO2 emission tax at the time they bought their new vehicle were also aware of the CO2 emission level of the vehicle they purchased. Conversely, 96 of the 184 (52.2%) respondents who indicated that they were aware of CO2 emission tax at the time of purchase were not aware of the CO2 emission level of the vehicle they had purchased. This indicates that more than half of the respondents who were aware of CO2 emission tax, were not aware of the CO2 emission level of the vehicle they purchased.

Of the 122 respondents who indicated that they were not aware of CO2 emission tax, 110 (90.2%) were also not aware of the CO2 emission level of the vehicle they had purchased, while only 12 (9.8%) indicated that they were aware of their new vehicle’s CO2 emission levels, but not the CO2 emission tax.

A chi-square test indicates that the relationship between responses to questions 2 and 4 is statistically significant (χ2(1) = 48.13, p < .001, phi = .397). Therefore, the awareness of tax and emission levels are related.

shows a cross-tabulation between responses to questions 2 and 5 in the questionnaire. In question 2, respondents had to provide a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response to the question: ‘At the time you bought the vehicle, were you aware of the CO2 emission tax charged on new vehicles?’ In question 5, respondents had to indicate ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to the question: ‘Are you aware that the CO2 emission tax charged is directly proportional to the level of emissions from a motor vehicle?’

Table 8. Awareness of CO2 emission tax versus awareness of calculation of CO2 emission tax.

The results in indicate that 143 of the 184 (77.7%) respondents who indicated that they were aware of CO2 emission tax at the time they bought their new vehicle were also aware of the fact that CO2 emission tax is directly proportional to the level of CO2 emissions from a motor vehicle. Conversely, 41 of the 184 (22.3%) respondents who indicated that they were aware of CO2 emission tax at the time of purchase were not aware that CO2 emission tax is proportional to the CO2 emission level of a new vehicle.

Of the 122 respondents who indicated that they were not aware of CO2 emission tax, 98 (80.3%) were also unaware that CO2 emission tax is directly proportional to the CO2 emission levels of a new vehicle. Conversely, 24 (19.7%) of the respondents who indicated that they were not aware of CO2 emission tax at the time of purchase, indicated that they were aware that the tax was levied in proportion to the CO2 emissions of a new vehicle.

A chi-square test indicates that the relationship between responses to questions 2 and 5 is statistically significant (χ2(1) = 99.70, p < .001, phi = .571). Therefore, respondents that were aware of CO2 tax were also aware of how the tax is calculated.

contains a cross-tabulation between responses to questions 2 and 6. As indicated above, question 2 deals with respondents’ awareness of CO2 emission tax at the time of the purchase of their new vehicle. In question 6, respondents had to indicate how they became aware of the ZAR amount of CO2 emission tax charged by choosing from four options, namely ‘calculated it myself’, ‘invoice’, ‘marketing’ and ‘salesperson’.

Table 9. Awareness of CO2 emission tax and awareness of ZAR amount of CO2 emission tax.

The results in indicate that 84 of the 149 (65.4%) respondents who were aware of CO2 emission tax at the time of purchasing their new vehicle became aware of the ZAR amount of CO2 emission tax charged from the salesperson. A further 20.8% of these respondents mentioned that they became aware of the ZAR amount involved from the invoice, while 15.4% of these respondents mentioned ‘Marketing’ as their source of information on the amount of CO2 emission tax involved. The remaining 7.4% of respondents who were initially aware of CO2 emission tax calculated the ZAR amount involved themselves.

Thirty-seven (37) of the 186 respondents (19.89%) who answered both questions 2 and 6, indicated that they were not aware of CO2 emission tax at the time of purchase. Of these 37 respondents, 17 (45.9%) mentioned that they became aware of the ZAR amount of the tax from salespeople. Another 11 of these 37 (29.7%) respondents indicated that they obtained information on the ZAR amount of the CO2 emission tax involved from the invoice, while the remaining 9% became aware of this information from ‘Marketing’ sources.

Salespeople are an important source of information on the ZAR amount of CO2 emission tax for both respondents who were and who were not initially aware of CO2 emission tax at the time of purchasing a new vehicle.

However, a chi-square test indicates that the relationship between responses to questions 2 and 6 is not statistically significant (χ2 = 5.73, p = .125).

provides descriptive statistics on respondents’ answers to the six Likert scale items included in the questionnaire. This table provides the active sample size (n), the mean score (M), the standard deviation (SD), as well as the two low- and two top-box percentages for each scale item. The two low- and two top-box percentages indicate the percentage of respondents who selected the two lowest scale points (i.e., ‘Strongly disagree’ and ‘Disagree’) and the two highest scale points (i.e., ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly agree’) respectively, providing an indication of the distribution of responses.

Table 10. Descriptive statistics on the Likert scale items included in the questionnaire.

indicates that the respondents, on average, perceived themselves as being environmentally conscious (M = 3.88, SD = 0.90) and accepted the theory that emissions from motor vehicles harm the environment (M = 4.06, SD = 0.86). However, the respondents, on average, tended to disagree that CO2 emission tax influenced their purchase decisions (M = 2.39, SD = 1.21) and were ambivalent on whether they regard CO2 emission tax as fair (M = 3.20, SD = 1.19). Furthermore, the respondents, on average, tended to agree that a significant increase in CO2 emission tax, from the current 2-4% to 25%, would alter their purchase decisions (M = 3.90, SD = 1.12), but were ambivalent as to whether CO2 emission tax will achieve the purpose of making vehicles on South Africa’s roads more environmentally friendly (M = 2.96, SD = 1.24).

The two top-box percentages in indicate that the respondents overwhelmingly agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, ‘I am environmentally conscious’, with a two top-box percentage of 72.88%. Similarly, 83.01% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, ‘I accept the theory that emissions from motor vehicles are harmful to the environment’. However, only 18.30% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that CO2 emission tax influenced their purchase decision in terms of causing them to purchase a different motor vehicle from the one they originally wanted to buy.

The two low- and two top-box scores also suggest that a sizable proportion of respondents are ambivalent or negative towards CO2 emission tax. In this regard, 45.10% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that CO2 emission tax is fair, while 29.08% indicated that they neither agree nor disagree with the statement and 25.82% indicated that they strongly disagree or disagree with this statement. In total, 54.9% of the respondents were either neutral or negative about the fairness of CO2 emission tax.

Respondents held differing opinions regarding the achievement of initial purpose of the CO2 tax; it is thus unclear whether the CO2 emission tax will achieve the purpose of making the motor vehicles on South African roads more environmentally friendly. While 37.83% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, 26.6% selected the neutral scale mid-point and 35.53% disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. No distinct conclusion can therefore be drawn in this regard.

In the forced rank-order question, respondents had to select the five most important factors that may have influenced their purchase decision from a list of 11 factors and then rank-order the five selected factors in terms of importance from 1 (most important) to 5 (least important). Unfortunately, many of the respondents misunderstood this question and allocated the same ranking (e.g., 2) to more than one factor, ranked all the factors as ‘most important’, ranked fewer than 5 factors, or left the question unanswered. These responses were thus excluded from the analysis that follows.

provides an overall ranking of the 11 factors, based on the responses provided by 220 respondents who answered the rank-order question correctly by ranking five selected factors and by assigning each selected factor a unique ranking from 1 to 5.

Table 11. Ranking of the five most important factors that may have influenced respondents’ purchase decisions.

The overall ranking of the 11 factors shown in was calculated as follows:

First, the ranking scores were reversed so that a score of 5 indicated the most important of the five selected factors and a score of 1 indicated the least important factor.

For each factor, the number of times the specific factor was rated was counted as 5 (most important), as 4 (second most important), as 3 (third most important), as 2 (fourth most import) or as 1 (least important).

Next, the ranking scores were summed for each factor using the following formula:

(No. of respondents who ranked the factor as most important × 5)

+ (no. of respondents who rated the factor as second most important × 4)

+ (no. of respondents who rated the factor as third most important × 3)

+ (no. of respondents who rated the factor as fourth most important × 2)

+ (no. of respondents who related the factor as least important × 1)

The maximum summed score that any factor could obtain was 220 × 5 = 1 100, which would have occurred if all 220 respondents ranked a specific factor as most important. For each factor in the ranking questions, the summed rankings calculated in Step 3 were expressed as a percentage of the maximum possible summed score of 1 100.

Finally, the 11 factors were ranked from most to least important based on the percentages calculated in Step 4, with the most important factor obtaining the highest percentage and the least important factor obtaining the lowest percentage.

5.3. Inferential statistics

The first hypothesis, H1, states that CO2 emission tax has no influence on the purchasing decisions of consumers buying new cars. To test this hypothesis, a one-sample t-test was conducted to compare the mean score of 2.39 (SD = 1.21) obtained on the third Likert scale item listed in (i.e., ‘The effect of CO2 emission tax influenced my purchase decision … ’) against the scale mid-point of 3.

The result of the one-sample t-test indicates that the sample mean of 2.39 (SD = 1.21) was significantly different from 3, t(305) = −.8.80, p < .001 at a 1% level of significance. This result indicates that respondents, on average, are of the opinion that CO2 emission tax did not have an effect on their purchase decision, and is thus consistent with H1.

To probe the association between the awareness of CO2 emissions tax and consumers’ purchasing decisions further, an ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple regression analysis was conducted. In this analysis, responses to the third Likert scale item listed in (‘The effect of the CO2 emission tax influenced my purchase decision … ’) were regressed against the independent variables listed in .

Table 12. The dependent and independent variables included in the multiple regression analysis.

The regression equation tested in the multiple regression analysis was:where e represents the error term.

shows the bivariate correlations between the variables included in the multiple regression model. Statistically significant bivariate correlations are highlighted in bold. This information indicates that the dependent variable, Y, has statistically significant positive bivariate correlations with five of the predictors included in the model, namely with X4, X5, X6, X7 and X8.

Table 13. Bivariate relationships between the variables included in the multiple regression model.

contains the regression results. The overall regression model is statistically significant (F = 12.238, p-value < .001). The adjusted R2 of .229 indicates that the model accounts for nearly 23% of the variance in the dependent variable. The results in indicate that only three variables in the regression model — X3, X4 and X8 — are statistically significant predictors of the dependent variable at a 1% level of significance. More specifically, these results suggest that respondents’ perceptions of the extent to which CO2 emissions tax influenced their purchase decisions is predicted by each of the following three predictors:

Table 14. Regression results.

X3: Respondents’ awareness that CO2 emission tax is charged directly proportional to the level of emissions from a motor vehicle (b = −.419, p = .009, β = −.174);

X4: Respondents’ self-reported environmental consciousness (b = .348, p < .001, β = .261); and X8: Respondents’ beliefs that CO2 emissions tax will achieve its purpose of making vehicles on South Africa’s roads more environmentally friendly (b = .372, p < .001, β = .383).

The results also indicate that the stronger respondents’ self-reported environmental consciousness, the more strongly they agree that the effect of CO2 emissions tax influenced their purchase decisions. The results also show that the more strongly respondents believe that CO2 emissions tax will achieve its purpose of making vehicles on South African roads more environmentally friendly, the more strongly they agree that the effect of CO2 emissions tax influenced their purchase decisions.

6. Limitations and future research

The scope of the research was limited to consumers that had purchased a new vehicle for which a sample was drawn during 2014 and 2015 in Johannesburg, Pretoria and Standerton. The results are therefore not generalisable as views expressed by consumers that opted to buy a second-hand car or rather not buy a car, possibly due to the levying of a CO2 emissions tax, were excluded. Despite this limitation, the results provide important insights into the decision behaviour of consumers buying new cars. This, furthermore, provides scope for future research in order to provide a more holistic evaluation of the influence of CO2 emissions tax on total passenger car sales. Additional variables which have not been included in the analysis could also impact the decision to purchase a new vehicle, such as the demographics of the consumer.

7. Conclusion

The main objective of this paper was to determine whether the CO2 emissions tax fulfils its primary objective of influencing the behaviour of consumers, buying new motor vehicles, by swaying their purchase decision to a more environmentally friendly passenger vehicle. The following two hypotheses were developed to answer the research question:

H1: CO2 emissions tax does not influence the purchasing decision of consumers that are purchasing new cars

H2: Higher awareness of CO2 emissions tax will negatively influence the purchasing decision of consumers that are purchasing new cars

Finally, the research revealed that price was ranked as the most important factor to influence consumers’ purchasing decision and that ‘environmental factors’ and ‘green thinking’ were the least important considerations for consumers when buying a new vehicle. Therefore, environmental considerations appear to not be an important factor considered when consumers buy a new car. Policymakers should consider this finding in future developments in the design of CO2 emissions tax legislation.

References

- Ackermann, T. (2014). Vehicle emissions tax and its effect on consumer behaviour in rural South Africa (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

- Allcot, H. & Wozny, N. (2010). Gasoline prices, fuel economy, and the energy paradox. CEEPR. [Online] Available from: http://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/54753/2010-003.pdf?sequence = 1 [Accessed: 2014-10-31].

- Anjum, N. (2008). Prospect of green-taxes in developing countries. Business & Finance Review, 28 April. [Online] Available from: http://jang.com.pk/thenews/apr2008-weekly/busrev-28-04-2008/p7.htm [Accessed: 2014-04-09].

- Automotive Business Review. (2010). RMI challenges government’s CO2 tax plan. [Online] Available from: www.abrbuzz.co.za/whats-the-buzz/661-rmi-challenges-governments-co2-taxplan [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- Barnard, B.M. (2014). The effect of passenger vehicle CO2 tax on consumer behaviour (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

- Borthwick, S. & Carreno, M. (2012). Persuading Scottish drivers to buy low emission cars? The potential role of green taxation measures. [Online] http://www.starconference.org.uk/star/2012/BorthwickCarreno.pdf [Accessed: 2014-11-03].

- Brouhle, K., & Khanna, M. (2007). Information and provisions of quality differentiated products. Economic Inquiry, 45(2), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2006.00033.x

- Carpenter, A. (2000). Developing a more sustainable world through consumer choice (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Prescott, Arizona: Prescott College.

- Carrim, W.A. (2014). The impact of carbon emissions tax on consumers’ decision to purchase new motor vehicles (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

- De Siena, C. (2011). South Africa’s green car tax: Why you’re being screwed. [Online] Available from: http://www.2oceansvibe.com/2011/06/07/south-africas-green-car-tax-why-youre-being-screwed/ [Accessed: 2014-11-07].

- Droppa, D. (2013). Green grab: SA CO2 taxes to increase. [Online]. Available from: http://www.iol.co.za/motoring/industry-news/green-grab-sa-co2-taxes-to-increase-1.1498937 [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- Economics.help. (2017). Polluter pays principle (PPP). [Online] Available from: http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/6955/economics/polluter-pays-principle-ppp/ [Accessed: 2017-04-21].

- Gerlagh, R., Van den Bijgaart, I., Nijland, H., & Michielsen, T. (2015). Fiscal policy and CO2 emissions of new passenger cars in the EU. CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, CPB Discussion Paper 302. [Online] Available from: http://www.cpb.nl/en/publication/fiscal-policy-and-co2-emissions-new-passenger-cars-eu-0 [Downloaded: 2015-07-07]. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2597588

- Ioncică, M., Petrescu, E., & Ioncică, D. (2012). Transports and consumers’ ecological behaviour. Amfiteatru Economic, 14(31), 70–83.

- Klein, P. (2014). European car taxes and the CO2 intensity of new cars (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Netherlands: Erasmus University Rotterdam. [Online] Available from: http://thesis.eur.nl/pub/17563/ [Downloaded: 2015-07-09].

- Kunert, U., & Kuhfeld, H. (2007). The diverse structures of passenger car taxation in Europe and the EU Commission’s proposal for reform. Transport Policy, 14(4), 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.03.001

- Lane, B., & Potter, S. (2006). The adoption of cleaner vehicles in the UK: Exploring the consumer attitude action gap. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15, 1087–1092.

- Lin, P., & Huang, Y. (2012). The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. Journal of Cleaner Production, 22(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.002

- Minton, A. P., & Rose, R. L. (1997). The effects of environmental concern on environmentally friendly consumer behavior: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 40(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(96)00209-3

- NAAMSA. (2010). NAAMSA media release N8/1/1. [Online] Available from: www.naamsa.co.za/papers/20100805/ [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- NAAMSA. (2011). Quarterly review of business conditions: motor vehicle manufacturing industry: 1st quarter 2011. [Online] Available from: www.naamsa.co.za/papers/2011_1stquarter/index.html [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- National Treasury. (2006). A Framework for Considering Market-based Instruments to Support Environmental Fiscal Reform in South Africa. Pretoria: National Treasury.

- National Treasury. (2010a). Discussion paper for public comment. Reducing greenhouse emissions: The carbon tax option. [Online] Available from: http://www.treasury.gov.za/public%20comments/Discussion%20Paper%20Carbon%20Taxes%2081210.pdf [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- National Treasury. (2010b). Press release regarding CO2 vehicle emissions tax. [Online] Available from: http://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/press/2010/2010080301.pdf [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- National Treasury. (2010c). Press release regarding CO2 vehicle emissions tax. [Online] Available from: http://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/press/2010/2010082601.pdf [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- National Treasury. (2013a). Carbon tax policy paper: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and facilitating the transition to a green economy. [Online] Available from: http://www.treasury.gov.za/public%20comments/Carbon%20Tax%20Policy%20Paper%202013.pdf [Accessed: 2014-04-06].

- Nel, R., & Nienaber, G. (2012). Tax design to reduce passenger vehicle CO2 emissions. Meditari Accountancy Research, 20(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/10222521211234219

- OECD/ITF. (2010). Reducing transport greenhouse gas emissions: Trends & data. [Online] Available from: http://www.internationaltransportforum.org/Pub/pdf/10GHGTrends.pdf [Accessed: 2014-04-09].

- Sheth, J., Newman, B., & Gross, B. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(91)90050-8

- SARS (South African Revenue Service). (2013). Schedules to the customs and excise act, 1964. Schedule 1 Part 3 section D. [Online]

- SARS (South African Revenue Service). (2014). 2014 Tax statistics. [Online] http://www.sars.gov.za/AllDocs/Documents/Tax%20Stats/Tax%20Stats%202014/TStats%202014%20WEB.pdf [Accessed: 2014-11-12].

- Spitzer, E. (2014). A climate change fix conservatives can love. [Online] Available from: http://www.slate.com/ [Accessed 2016-05-19].

- Trading Economics. (2016). South Africa new car sales. [Online] Available from: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/car-registrations [Accessed: 2017-04-21].

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2014). Global greenhouse gas emissions data. [Online] Available from: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data [Accessed: 2017-04-11].

- US Energy Information Administration. (2012). Independent Statistics and Analysis. 2012. International energy statistics. [Online] Available from: www.eia.gov/cfapps/ipdbproject/IEDIndex3.cfm?tid = 90&pid = 44&aid = 8 [Accessed: 2015-10-05].

- Walls, M. & Hanson, J. (1996). Distributional impacts of an environmental tax shift: The case of motor vehicle emissions taxes. [Online] Available from: http://www.rff.org/Documents/RFF-DP-96-11.pdf [Accessed: 2014-04-09].