Abstract

Purpose: The goal of the study is to provide guidelines for a simplified South African Value-Added Tax (VAT) Act.

Motivation: The current VAT Act lacks logical structure and is therefore complex to teach, apply in practice and administer. The study on which this article reports investigated the structure of the VAT Act as an element of legal complexity.

Design/Methodology/Approach: The research was conducted in two phases: a literature review, followed by semi-structured interviews.

Main findings: Existing empirical studies confirm that the poor structure, layout and organisation of the VAT Act contribute to its complexity. In addition, research confirms that improvements to structure, layout and organisation enhance the readability of statutes. Interviewees agreed that the current incoherent structure of the VAT Act contributes to its complexity. The findings confirm that the complexity of the VAT Act raises compliance and administrative costs.

Practical implications/Managerial impact: The literature review and interview findings contribute to the development of guidelines for a simplified South African VAT Act, which is the contribution of this study. The principles include adhering to a VAT vendor’s lifecycle, grouping sections together, introducing headings and subheadings, using clear signposting, employing international benchmarks and seeking a solution that addresses local challenges most effectively.

Novelty/Contribution: One recommendation that stands out is to completely rewrite the VAT Act. As a first step in this rewrite project, it is recommended that an index be developed using the guidelines. This is an initial step towards simplification of the South African VAT Act.

1. Introduction

Knowledge is a process of piling up facts; wisdom lies in their simplification.

The Value-Added Tax Act (VAT Act) was introduced in South Africa on 30 September 1991 (Republic of South Africa, Citation1991). The authors of the present article suggest that the VAT Act is incoherent in structure, which makes it difficult to teach, apply in practice and administer.

By way of an example to illustrate the problem of scattered sections, which contribute to the incoherent structure of the VAT Act, the VAT implications of importing “electronic services” are presented next. Before considering the VAT implications of importing “electronic services”, it is, however, necessary to consider the VAT implications of “imported services”.

The sections that must be considered for “imported services” are as follows:

Section 1 definitions: “supply”; “imported services”; “open market value”

Section 3: determination of “open market value”

Section 7(1)(c): imposition of VAT on imported services by any person

Section 14: collection of VAT on imported services, determination of value and exemptions; read with section 10(2) and (3): general value of supply rule; and section 3: determination of open market value.

The following sections must be considered when importing “electronic services”:

Section 1 definitions: “electronic services”; “enterprise” – paragraph (b)(vi); “export country”; “services”; “supply”

Section 7(1)(a): imposition of VAT on the sale of goods or services

Section 7(1)(c): imposition of VAT on imported services by any person; read with section 14(5)(a): exceptions to imposition of VAT on imported services by any person

Section 23(1A): registration requirements for suppliers of electronic services

Section 16(2)(b), read with section 20(7): input tax and documentary requirements

Government Notice No. 429 published in Government Gazette No. 42316: regulations in respect of electronic services.

In addition to the sections of the VAT Act, vendors must also consult the following documents issued by the South African Revenue Service (SARS) to fully comprehend the VAT obligations imposed on the supply of electronic services in South Africa:

SARS Frequently Asked Questions: Supplies of Electronic Services (SARS, Citation2019)

SARS External Guide: Foreign Suppliers of Electronic Service (SARS, Citation2022)

Binding General Ruling No. 28: Electronic Services (SARS, Citation2016).

The above example illustrates the number of sections that must be evaluated when importing services and electronic services, which are scattered throughout the VAT Act.

In addition, despite the fact that the time and value of supply rules are contained in sections 9 and 10 of the VAT Act, the Act is not always consistent in terms of its logical design. When evaluating imported services, the time and value of supply are found in section 14, rather than sections 9 and 10, respectively. Further, even though section 1 contains sections that are applicable throughout the Act, section 3 also contains the definition of “open market value” which is specifically referred to in sections of the VAT Act, i.e., section 10(2).

The VAT Act does not follow a VAT vendor’s lifecycle. VAT registration is first encountered in section 23 of the VAT Act, while the basis of registration is contained in section 15.

The sections do not always cross-refer both ways. In this specific example, there is no cross-reference contained in section 7(1)(c) to section 14. The backward cross-reference to section 7(1)(c) is, however, contained in section 14. Another example is section 23(1A) which contains a backward cross-reference to the definition in section 1 of “enterprise” – paragraph (b)(vi). However, the definition does not reference forward to section 23(1A).

External documents must also be consulted to fully comprehend the VAT obligations when importing electric services. The definition of “electronic services” in section 1 refers to the services prescribed by the Minister by regulation, namely Government Notice No. 429 (National Treasury, Citation2019). Further, SARS Frequently Asked Questions, Guide and Binding General Ruling must also be consulted. This further illustrates the scattering not only of sections in the VAT Act but also direct references to external Government Gazette Notices and other SARS issued documents that must be consulted when evaluating a single transaction or event in the VAT Act.

SARS guides are simply meant to assist taxpayers in the practical understanding and execution of the law’s obligations (SARS, Citationn.d.). SARS (Citation2021, n.p.) states as follows on its website: “Interpretation Notes are intended to provide guidelines to stakeholders (both internal and external) on the interpretation and application of the provisions of the legislation administered by the Commissioner”. In terms of section 1 of the Tax Administration Act (No. 28 of 2011) (the TAA) as read with section 5(1) of the TAA, a ‘practice generally prevailing’ is “a practice set out in an official publication regarding the application or interpretation of a tax Act” (Republic of South Africa, Citation2011). An ‘official publication’ is defined in section 1 of the TAA to specifically include an Interpretation Note. This further strengthens the argument for the urgent need for guidelines for a simplified South African VAT Act, i.e., the legislation must be clear, limiting the need to place reliance on SARS’s Guides and Interpretation Notes. SARS Guides and Interpretation Notes in effect have limited or no value when disputes arise and the interpretation is challenged in court, as is evident in Marshall NO v Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service (Citation2018) CCT 208/17 ZACC 11.

This is only one example that displays the problem at hand, namely that the VAT Act lacks a coherent structure. In many cases, the sections applicable to a single event are scattered throughout the Act, and while comprehensive, it is incoherent, which makes it complex. It appears like a number of provisions thrown together, often in an illogical manner. The problem existed at inception with the introduction of the VAT Act, but the situation has been compounded since its introduction. As suggested earlier, the incoherent structure of the VAT Act makes it difficult to teach, to apply the provisions in practice and to administer the VAT Act by SARS. This in turn ultimately has an impact on VAT compliance and collection levels.

There is currently a lack of published empirical studies conducted on the logical structure of the VAT Act and its complexity. The aim of this study is to aid with the restructuring of the VAT Act in South Africa. The overall goal is to provide guidelines for improvements to the structure of the VAT Act. In this regard, the study sought to make a meaningful practical contribution by presenting guidelines for a simpler and more coherent South African VAT Act.

The rest of this study is organised as follows. The next section presents an outline of the research methodology employed. This is followed by Section 3, which sets out a summary of the literature review on tax complexity, as well as an examination of empirical studies that demonstrate that the incoherent structure in legislation contributes to tax complexity, with Section 4 setting out the findings. Section 5 concludes.

2. Research methodology

The research was conducted in two phases, namely a literature study and semi-structured interviews. The design was sequential, i.e., in Phase 1, the literature review partly informed the structure of the interviews in Phase 2. The literature review explored empirical studies conducted in relation to the incoherent structure in legislation, which leads to tax complexity. The interviews solicited views from those who were impacted by the problem on possible improvements to the incoherent structure as an element of complexity in the VAT Act. The findings from the literature review were used to support the finding from the interviews.

Information and documents were sourced through online searches, making use of search engines such as Google Scholar and the University of Johannesburg’s databases, namely UJoogle, Jutastat Online and Lexis Library. Online searches were also carried out on the websites of professional accountancy firms, government (SARS and the National Treasury) and international organisations, namely the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Monetary Fund. Keywords that were used for the search included, but were not limited to, Value-Added Tax Act, unstructured, complexity, difficulty, simplicity, scattered, dispersed, uncertainty and ambiguity.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect primary data from participants who directly worked with the VAT Act. Given the complexity of the research problem and the small number of specialists within the stakeholder groups, interviews were favoured over surveys. The research problem involved legal complexity; therefore, interviews were deemed an appropriate data collection technique, as recommended by Babbie and Mouton (Citation2001).

The type of purposive sampling used in this study was expert sampling, which is a technique used to collect information from individuals with specialised knowledge (Rai & Thapa, Citation2015). The researchers applied judgement, using their experience and expertise, to base the selection of the sample on VAT specialists in industry and academia who worked and engaged directly with the VAT Act.

In this study, the researchers were interested in the perspectives of four key stakeholder groups: tax lecturers who teach VAT, tax practitioners in the sector (i.e., VAT specialists), SARS employees working in the VAT department and National Treasury employees involved in the development of the VAT Act. Consideration of these four stakeholder groups was based on the fact that each stakeholder group contained VAT specialists who worked and interacted daily with the VAT Act. These participants understood the research problem, i.e., the interviewees were close to the issue at hand. The judiciary was considered a stakeholder, but was excluded, because judges do not work and interact with the VAT Act closely enough on a daily basis to fully comprehend the overall structural concerns, and their focus is rather on the interpretation of the VAT Act.

The sample of interviewees therefore included the following four stakeholder groups, with the reason for their selection:

Tax lecturers who taught VAT at a postgraduate level at a South African university (academics) in relation to teaching difficulties;

With the consent of industry professional bodies, tax practitioner industry VAT specialists who served on the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) VAT Sub-committee and/or the South African Institute of Taxation (SAIT) VAT Committee (advisors) for a practical perspective on challenges;

With the consent of the SARS Commissioner, SARS personnel working in the VAT department (developers) in relation to administration and interpretative difficulties; and

With the consent of the Head: Tax and Financial Sector Policy at the National Treasury, personnel involved in drafting the VAT Act (developers) to provide insight into the rationale behind the current design, layout and structure of the VAT Act and suggested areas of improvement.

SAICA is South Africa’s leading accounting body (SAICA, Citationn.d.). SAIT is the largest of South Africa’s professional tax organisations, and it aims to improve the tax profession by establishing standards for education, compliance, monitoring and performance. SAIT contributes to the development of professional practices and individuals of the highest calibre (SAIT, Citation2022).

presents a summary of the number of interviews conducted with each of the four stakeholder groups.

Table 1. Summary of interviews with each stakeholder group.

No detailed demographic information was collected from the participants, because it was deemed unnecessary for the purposes of this study. An hour was set aside for each interview. The list of core questions contained only 10 questions. Some questions were included as a subset of main questions. The main themes of the questions were incoherent structure, plain English, sentence length, active/passive voice, ambiguity, exemptions (including rebates and concessions), amendments, economic policy, best practice and solutions. The focus of this research, which is part of a larger study, is incoherent structure, best practises, and solutions. The primary language of the interviewees was either English or Afrikaans, and care was taken to ensure that the questions were clear and lacked ambiguity. Confidentiality was ensured. Even though the researcher asked the questions in chronological order, the interviewees’ responses were not always centred on the question at hand, as the discussions occasionally shifted. This was permitted by the researcher because it enhanced the collection of rich qualitative data.

Two independent professional transcribers were used to transcribe all the interviews. To ensure the confidentiality of the interviewees and the interview content, the two transcribers signed confidentiality agreements. The researcher verified the accuracy of all transcriptions by comparing them to the interview recordings. The original recordings and the transcriptions will be stored in a secure location for five years, after which they will be destroyed.

The data were analysed as follows: transcriptions were coded, codes were grouped into categories and categories were combined into themes (see Bryman & Bell, Citation2014). The researcher used ATLAS.ti Windows (Version 22.2.5.0) to manage the data. Prior to collecting data and conducting interviews, ethical clearance and approval were obtained from the participants’ institutions and participants provided their consent to participate in the research.

3. Literature review

The literature review is presented in this section as follows: Tax complexity which form the theoretical basis of this study is explained. This is followed by first presenting the general literature findings on improvements to legal complexity (with a focus on logical structure), then the specific literature findings on the incoherent structure in relation to the VAT Act (internationally and in relation to the South African VAT Act), and finally the general literature on guidelines for logical structure in legal drafting.

3.1. Tax complexity

The term ‘tax simplification’ refers to the process of making the tax system easier to understand (Tran-Nam et al., Citation2019). As a result, the definition of tax simplification is determined by what tax simplicity, or its inverse, tax complexity, entails. Despite its widespread use, tax complexity is not a concept that can be easily defined, measured or agreed upon. Tax complexity occurs as the tax legislation becomes more sophisticated (Richardson & Sawyer, Citation2001). There are, however, different approaches to characterising tax complexity.

The approach by Tran-Nam (Citation1999) is to distinguish between tax complexity that is legal (formal) and tax complexity that is economic (effective). The difficulty with which a given tax statute may be read, grasped, interpreted and applied in diverse practical scenarios is referred to as legal complexity. Legal simplicity is therefore clearly of fundamental interest to academic or practising tax lawyers, tax advisors and judges when defined in this way.

According to Tran-Nam (Citation1999), the degree of complexity of a tax law is determined by both the language used to express the law (e.g., plain English, grammar, sentence length, active voice and logical structure) and the content of the law (e.g., ambiguity; exemptions, rebates and concessions; and annual amendments). When described in this manner, this study focused on logical structure, which is an element of legal complexity.

3.2. General literature findings: Legal complexity (logical structure)

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Valabh Committee was an appointed committee of the New Zealand government charged with reviewing various aspects of the income tax system (Smaill, Citation2021). The New Zealand rewrite project, the Valabh Committee’s 1991 report titled “Key reforms to the scheme of tax legislation” recommended certain key features for the reform strategy, including “the reorganisation of the legislation into a more logical and coherent scheme” (Smaill, Citation2021, p. 2). In 1995 the rewrite project in the UK was presented as “an awesome undertaking” (Budak & James, Citation2018, p. 30). It was established with a comparable purpose to that of the New Zealand rewrite project. The rewrite initiative in the UK intended to reorganise legislation by utilising modern language and shorter sentences, as well as offering logical definitions and clear signposting (Budak & James, Citation2018).

After the New Zealand rewrite project, Saw and Sawyer (Citation2010) assessed the success of the rewrite by examining the readability of the New Zealand Income Tax Act and other materials. A comparison of the results of Tan and Tower (Citation1992) and Saw and Sawyer (Citation2010) showed that New Zealand’s initiative to redraft the tax rules was successful with respect to readability (Sawyer, Citation2013). The New Zealand Income Tax Act was revised in phases, with the first step being the reorganisation of the Income Tax Act of 1976 and the Inland Revenue Department Act of 1974, which culminated in the Income Tax Act of 1994 plus the Tax Administration Act of 1994 and the Taxation Review Authorities Act of 1994. This reaffirms the issue of the present study, namely that an unstructured Act leads to tax complexity, and hence the need for South Africa’s VAT Act to be reorganised.

The Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) was initially established for a five-year period in the UK in 2010 to study various aspects of the tax system and report on its recommendations, both in the short term and in the long term, while avoiding policy issues and formulating recommendations on a revenue-neutral basis. The OTS became a permanent part of the UK tax landscape in 2016, receiving full statutory authority (Dodwell, Citation2021). The OTS has since been disbanded (OTS, Citation2022; Whiting, Citation2019). According to Sawyer (Citation2023, pp. 1–2), “[t]he available evidence clearly indicates that the decision [to disband the OTS] is misinformed and is expected to be a retrograde step that risks undoing the extensive effort of the OTS”. The OTS created a complexity index to help analyse different aspects of the tax code and focused its efforts on those that provided the most reward. The index was created over time and went through several versions before settling on 10 factors (OTS, Citation2017). A question posed about readability is whether the provision can be read alone, or whether it requires extensive cross-referencing and validation of definitions in other sections of the code. It is argued that this rating should be subject to a supplement if the provision requires significant effort to collect all relevant information. It can be noted that the OTS did take the distribution of sections, i.e., cross-referencing to definitions, into account while establishing the complexity index.

3.3. Specific literature findings: Incoherent structure of the VAT Act

Malla (Citation2016) conducted the only empirical study worldwide on the design and structure of the VAT Act in India from the perspective of traders in Jammu and Kashmir State. The purpose of his study was to examine and analyse the structural design aspect of VAT in Jammu and Kashmir from the perspective of traders and to suggest ways to make the structure of VAT more accommodating to the state’s trading community. According to his findings, traders in Jammu believed that the structure of the VAT Act was moderate to grasp, while traders in Kashmir believed the structure was difficult to grasp.

Young (Citation2021, p. 8) comments as follows on the logical structure of the South African VAT Act:

Cross-references between sections also abound, making the interpretation of the sections extremely complex. Section 16(3) of the VAT Act includes fourteen subsections, some with numerous sub-subsections and provisos, each of which is cross-referenced to a different section in the Act.

3.4. General literature: Guidelines on logical structure

A statute’s logical organisation aids comprehension (Thuronyi, Citation1996). When a statute is well organised, it is also easier to determine where to look for an answer to a specific question and which sections of the statute can be ignored by a specific taxpayer. Provisions on the same topic must be grouped together for organisation. Furthermore, each subdivision of the statute, including individual sections, should be written in a logical order. Typically, this entails stating the general rule first, followed by exceptions and special rules for specific cases. Kimble (Citation1996) conducted a literature study on the use of plain English and puts forward a number of suggested guidelines for legal writing, which also include grouping related ideas together and ordering the parts in a logical sequence. Even though the time and value of supply rules are contained in sections 9 and 10 of the VAT Act (i.e., the VAT Act does have grouping), the logical design of the Act is not always consistent; when evaluating imported services, for instance, the time and value of supply are found in section 14, rather than sections 9 and 10, respectively. The definitions contained in sections 1, 2, and 3 of the VAT Act are another example of inconsistency.

An example of poor organisation is when a large statute is not divided into sections, forcing the reader to search the entire statute for the relevant provisions (Thuronyi, Citation1996). Many cross-references can be found in a well-written tax statute, whether explicit or implicit (i.e., the use of a term whose meaning is defined elsewhere in the statute). The example of imported electronic services revealed that a number of sections and external SARS documents must be consulted to fully comprehend the VAT implications. The VAT Act does not always provide clear signposting. The example of imported electronic services analysed also demonstrated that sections do not always cross-reference in both directions. In this instance, section 7(1)(c) does not contain a cross-reference to section 14. However, the cross-reference to section 7(1)(c) is contained in section 14.

Petelin (Citation2010, pp. 212–213) suggests beginning the process of writing clearly by creating a profile of your intended and potential readers, and then expounds on a range of guidelines that she recommends under the headings of “substance and structure” and “style (verbal and visual)”. Substance and structure include a “coherent, logical structure and appropriate sequence (general information before specific and before exceptions), with appropriate transitional words and phrases” (Petelin, Citation2010, p. 213). To achieve logically organised content, the text must be structured from the perspective of the reader, not the author. This means that readers should be able to easily navigate the text, locate the desired information and comprehend it (Cutts, Citation2013). The analysed example of imported electronic services appears to be written from a perspective of a VAT expert rather than that of a VAT vendor, requiring a VAT specialist to comprehend the VAT requirements on a VAT vendor.

Commenting on simplifying the corporate tax system in South Africa, the Davis Tax Committee (DTC) (Citation2018, p. 91) states as follows:

One radical suggestion has been that the Act should be re-written and re-structured in its entirety. Such a rewrite would undoubtedly result in a rearrangement of the provisions of the Act into a more coherent logical sequence. This may enhance the efficiency of the compliance environment of taxpayers. (emphasis added)

4. Findings

The findings are presented as follows: The opinions of interviewees regarding the incoherent structure are discussed, along with examples demonstrating that the interviewees concurred that the VAT Act is structured incoherently. The discussion then turns to the pertinent comments and remarks made by interviewees when discussing the incoherent structure of the VAT Act, followed by notable remarks.

In order to preserve anonymity, the participants were categorised as academics, advisors and developers (i.e., employees from SARS and the National Treasury).

4.1. Incoherent structure

The following was stated by an academic in relation to the incoherent structure:

You almost don’t start with the Act when you start preparing for VAT. You start with other documents. You go to textbooks. You go to the SARS guide … to get the information that you need. Then you might go to the Act and even then, you don’t have the comprehensive picture. You have to look at other sources as well and the risk is always there that you are not aware that it’s there and this is for us that are people that deal with taxes and acts every single day. So, if it’s difficult for us to do it, I can’t imagine for a person who is just a businessperson, and their specialty is not in law. So, it’s definitely a big problem.

An interviewee from the advisors group made the following comment in relation to the incoherent structure:

… I’ve never thought of the VAT Act as complex or disorganised, to be honest, to put it out there, because the VAT Act as you know has been around since ‘91 … based on New Zealand … what I do think is that I think there is definitely scope to do some adjustments to the structure …

An interviewee from the developers group expressed the following sentiment in relation to the incoherent structure:

… I haven’t found it to be that difficult to understand being an attorney … because I’ve been in VAT for so many years that I sort of know where to find things … I do see […] a point that certain cross-references are not there and that sort of thing, right, but you look at 14 it talks about 7(1)(c) and yes 7(1)(c) will not take you to 14 and yes those are the times when you need to look at, read the SARS guide.

Interviewees provided specific examples in support of the incoherent structure. Imported services, VAT adjustments and fixed property transactions were the three examples that were cited by the interviewees as the most grounded examples to illustrate the dispersed incidence of the sections in the VAT Act in relation to a single transaction or event. The example of imported services was also analysed in the introduction to the research problem earlier in the present article.

An interviewee from the academics group commented: “Things like electronic services. Imports for me, I said also it’s all over the place … ” An interviewee from the advisors group said: “I said one thing that would help me is imports, maybe have a whole coherent section dealing with imports and everything that has to do with imports, so that it’s together”, while an interviewee from the developers group commented: “So, we don’t have by any means a perfect electronic services regime. There’s still a lot of problems with it, but what we have, we know what’s there, we know more or less why it’s there.”

Even though interviewees from the advisors and developers groups may not have agreed that the incoherent structure of the VAT Act is causing complexity due to their natural VAT expertise, they still cited specific examples where the VAT Act is incoherently structured.

The interviewees discussed and described a number of concerns (i.e., categories) related to the incoherent structure of the VAT Act. Tax complexity was the most prominent issue discussed and raised when discussing the incoherent structure. An interviewee from the advisors group made the following comments regarding the complexity of the VAT Act: “With this it’s really difficult and it’s a tax that a lot of people are exposed to, so it should not be that difficult to understand what’s going on.” The interviewee went on to state: “I remember relying on the legislation very little … but just in general the VAT Act is complex and if you speak to students and you even speak to practitioners, they will all tell you that the VAT Act is difficult to apply.”

Therefore, interviewees from the academics group asserted that poor structure contributes to the complexity of the VAT Act. This corresponds with the study conducted by Malla (Citation2016), as discussed in the literature review, which is the only empirical study on the design and structure of the VAT Act.

Regarding the incoherent structure of the VAT Act, it should be noted that the OTS considered the distribution of sections, i.e., cross-referencing to definitions, when calculating the complexity index (OTS, Citation2017). Consequently, the review of relevant literature supports the contention that the distribution of sections contributes to tax complexity.

Interviewees cited inconsistencies as complicating the incoherent structure. Inconsistencies in the VAT Act refer to instances in which a section seems misplaced, and its natural placement would be under a more specific heading that encompasses the section. Several examples of inconsistencies were also provided by the interviewees.

The examples of inconsistencies include section 18(3), the adjustment section, yet it pertains to a deemed supply of fringe benefits. The section that addresses all deemed supplies, section 8, would be the most logical placement. An interviewee from the advisors group commented: “For instance section 18(3) belonging a bit and I know I am jumping the gun, but belonging a bit more with section 8 than with section 18.” Other examples cited include sections 9 and 10 (time and value of supply) and sections 13 and 14 (which deal with imported goods and services, respectively). This is despite the fact that sections 9 and 10 deal with specific time and value rules and that sections 13 and 14 include the time and/or value rules in their scope. In this regard, an interviewee from the academics group commented: “ … you taught us that the time and value rules is in 9 and 10 and now look at this 13 and 14 and there is time and value rules.” Under adjustments, it was suggested that section 22, which deals with irrecoverable debts, be placed more appropriately. In this regard, an interviewee from the academics group commented: “I will also say section 22, the irrecoverable debts, that for me is also belonging to adjustments.”

This all corroborates the comments made by Thuronyi (Citation1996), namely that a poor example of organisation is when a large statute is not divided into logically located sections, requiring the reader to search the entire statute for the relevant provisions. Explicit cross-references can be found in a well-written tax statute (e.g., the use of a term whose meaning is defined elsewhere in the statute).

Interviewees also mentioned that complexity ultimately results in an added layer of costs for the VAT vendor. An interviewee from the academics group commented: “It’s an additional cost [of] doing business, but it should not drive what you decide to do and whether you want to comply or not comply with something.” An interviewee from the advisors group commented as follows in this regard:

… I think it’s a very honourable thing … simplifying and making sure people can read the law a lot better, making it more accessible to the taxpayer and to academics and to people who want to learn about it you know to be an advisor, I think there’s a lot that can be done to simplify it so that people are more willing to get into VAT consulting and VAT advisory and because the more you know, the better you will be compliant. I mean that’s in interest of the state, interest of SARS, and it’s in the interest of all taxpayers out there not having to pay a lot [of] penalties and interest getting it wrong. So, I think it’s definitely something in the public interest […] because you’ve got all stakeholders winning or getting a win-win from that, so it’s worth taking on, definitely.

An interviewee from the academics group commented:

I think my assumption is in practice they just use the VAT guide. It is so comprehensive that they will fall back to the VAT guide as we do in teaching in sort of clarifying it. They use the VAT guide as their primary legislation. So that’s why people in practice I think are not as concerned with it because they just follow the VAT guide but we in teaching it and in disputes have a problem with it.

An interviewee from the advisors group said the following:

… the exportation of goods, direct and indirect exports where you refer to into interpretation notes and BGR [Binding General Rulings], if I recall correctly and I think that might be difficult because it’s not in one place and for that reason, I’ve always found it challenging to actually give advice on exportation of goods specifically.

An interviewee from the developers group commented, in relation to SARS guides: “Well, it’s not an official publication either.” Therefore, due to the incoherent structure of the VAT Act, vendors also consult external documents such as SARS guides. However, SARS guides are not an “official publication” as defined in section 1 of the TAA and accordingly do not create a practice generally prevailing under section 5 of that Act. It is also neither a binding general ruling under section 89 of Chapter 7 of the TAA nor a ruling under section 41B of the VAT Act, unless otherwise indicated. SARS guidelines are simply meant to assist taxpayers in the practical understanding and execution of the obligations of the law (SARS, Citationn.d.).

In Marshall NO v Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service (Citation2018) CCT 208/17, ZACC 11, the Constitutional Court firmly resolved on the extent to which a court may consider or refer to an administrative body’s interpretation of legislation (such as SARS interpretation notes and guides). The Constitutional Court confirmed that courts should disregard interpretation notes or guides when interpreting law as a rule (Le Roux & Mia, Citation2020). However, it did implicitly recognise that in any marginal question of statutory interpretation, a court may have regard to an interpretation as set out in an interpretation note if there is evidence that the interpretation has been recognised and followed by SARS and taxpayers alike for a number of years.

The comments above are consistent with the literature findings, which confirmed that simple tax laws are required so that taxpayers can comprehend the rules and comply with them correctly and cost-effectively (AICPA, Citation2001). Therefore, complexity raises tax compliance costs.

Other noteworthy comments made by interviewees when discussing the incoherent structure in the VAT Act are discussed next.

When discussing the incoherent structure, interviewees from the developers group also named anti-avoidance as a related topic causing complexity. An interviewee from the developers group commented as follows:

… the level of fraud with VAT is far higher than any of the other taxes because of the fact that it’s transaction-based … eventually things can become complicated because you are trying to plug in loopholes and industry finds another loophole and then you try to plug that and then something else happens and then you know by the end of the day, the wording in the sections is not what you set out for it to be.

The working relationship between SARS and the National Treasury, and the lack of skills and capacity at the National Treasury, were also cited as contributing to the complexity of the VAT Act. An interviewee from the developers group made the following comment regarding the working relationship between SARS and the National Treasury:

Now, if you don’t have a team in National Treasury and SARS, that’s 100% in step with each other and talk to each other regularly and listen to each other and do what is required, then you’re going to have issues, so that’s just part of the problem as well, and you won’t pick that up just from, you know, reading the legislation.

The working relationship between the revenue authority and those responsible for policy and the capacity constraints on the policy drafting team contributing to tax complexity are new empirical findings not identified in the literature review. These empirical findings contribute to the body of knowledge (i.e., literature) as a result of this study.

4.2. Guidelines

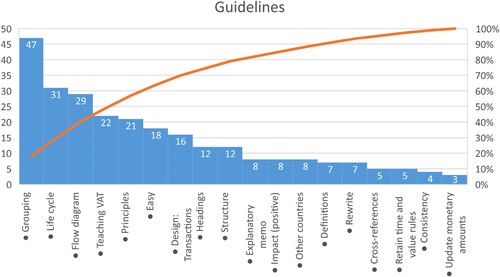

The researchers probed interviewees’ suggestions on guidelines that must be considered when designing a solution to the incoherent structure. indicates how many times a specific guideline was mentioned during the interviews. It plots the distribution of data in descending order, with a cumulative line on the secondary axis as a percentage of the total.

An analysis of confirmed that grouping and headings that adhere to a logical structure, such as the lifecycle of a VAT vendor, should be a crucial element of the design, layout and structure of the VAT Act. The Act must include cross-references and be uniformly formatted.

An interviewee from the academics group made the following comment in relation to grouping:

… we have a general rule and then a grouping per concept and like fixed property … you can also group vouchers and coupons and the fringe benefits you can group, and I made a comment here, it’s like the Seventh Schedule. We have the Seventh Schedule now where we group these different sort of fringe benefits and in that the value of supply and things are talked about under the one heading. So, the grouping per concept or theme, I think that was my first thought on how to simplify it.

An interviewee from the advisors group commented as follows in relation to headings:

… you can even have headings that say you know, registrations, accounting for VAT … because that’s actually how the textbooks set out the various sections of the law, so I think it’s a brilliant idea to do that … you would find the section in a certain place almost because you would know where to go and find it … and then you can deal with special cases … [for example] … you can even after each section have like a special … section that deals with special cases.

An interviewee from the academics group commented as follows on following the lifecycle of a VAT vendor: “I think it will simplify it. It will simplify it most certainly if we follow that lifecycle approach.” An interviewee from the academics group said: “I think it’s a brilliant idea, I think it’s an excellent idea to work on the lifecycle because then the sections [follow] … a chronological order [of] the lifecycle.” An interviewee from the developers group commented: “ … yes, that can work and in the process of doing that you will actually be forced to rewrite the legislation.” In its 1991 report, “Key reforms to the scheme of tax legislation”, the Valabh Committee recommended reorganising the legislation into a more logical and coherent scheme for the New Zealand rewrite project (Smaill, Citation2021).

An interviewee from the developers group made the following comment in relation to missing cross-references: “Sometimes they write the time and value of supply in that section 18 and sometimes they don’t. Also, section 18(3), is that an adjustment or is it a separate supply on its own?” There are numerous cross-references between sections of the VAT Act, making interpretation of the sections exceedingly complex (Young, Citation2021). The UK Tax Law Rewrite initiative aimed to reorganise legislation by using clear signposting (Budak & James, Citation2018). When calculating the complexity index, the OTS considered the distribution of sections, i.e., cross-referencing to definitions (OTS, Citation2017). A well-written tax statute contains explicit and implicit cross-references (i.e., the use of a term whose meaning is defined elsewhere in the statute) (Thuronyi, Citation1996).

Strong sentiments by the interviewees also supported the introduction of a flow diagram, i.e., an index to the VAT Act. An interviewee from the academics group suggested: “ … a mind map”. An interviewee from the advisors group commented as follows: “I think the VAT Act could probably benefit more from … how you teach for instance that you use a flow diagram and add that as almost not as a ruling but as a guidance somewhere … or even as a schedule to the VAT Act.” An interviewee from the developers group commented as follows in this regard:

… if there could be an easier way to find sections that [are] relevant to a specific topic … I think it would be very useful if you had an index by topics like fixed property to say here all the sections dealing with it all, something like that … can help you to find the relevant sections.

The DTC (Citation2018:91) suggests rewriting and reorganising the entire Income Tax Act to simplify it. Such a rewrite would reorder the provisions of the Act to make more sense, which will improve taxpayer compliance. No such mention was made in respect of the VAT Act. Complex tax law may threaten the tax system, resulting in lower compliance levels by taxpayers (Sulaiman Umar & Saad, Citation2015). Readability (including logical structure) is therefore crucial for tax compliance and administration. Therefore, a rewrite of the VAT Act will increase taxpayer compliance and improve SARS’s tax administration.

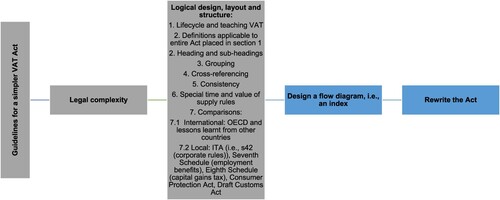

The guidelines in were then consolidated to present the final guidelines for this study. The literature review and the semi-structured interview data analysis supported the guidelines offered for a simplified VAT Act, which is presented in .

The guidelines outline the principles that must be incorporated when simplifying the VAT Act in terms of its logical design, layout and structure as an element of legal complexity. In relation to logical design, layout and structure, which was the focus of this study, guidelines include following the lifecycle of a VAT vendor and the way the Act is explained by educators, including all definitions that apply to the entire Act in section 1. This includes incorporating headings and subheadings, grouping complex sections together and avoiding inconsistency, i.e., sections should always be included under their logical section headings and include clear signposting. Further, it draws from local and international best practices. As a first step in the project to rewrite the VAT Act, the guidelines suggest that a flow diagram or an index, be developed.

The researcher sent the guidelines for a simplified VAT Act to the interviewees to obtain additional qualitative data, i.e., the interviewees’ opinions and any suggested improvements (see Bryman & Bell, Citation2014). Even though the interviewees were only requested to respond to the researcher’s email if they had additional suggestions or comments, 9 out of 15 of the interviewees responded to the request for suggestions and/or improvements. Five of the nine participants were academics, three were consulting professionals (i.e., from the advisors group) and one was from the National Treasury. The high response rate confirms the professionalism of the sampled interviewees and reaffirms the importance and prevalence of the current research issue. The interviewees did not make any additional changes to the guidelines.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the incoherent structure of the VAT Act, which contributes to its complexity and makes it difficult to teach, apply in practice and administer. The research was conducted in two phases, namely a literature review and semi-structured interviews.

This is the first published study of its kind to investigate the incoherent structure of the South African VAT Act. The findings, which are supported by the literature, confirm that the incoherent structure of the VAT Act contributes to its complexity. Guidelines are proposed for the restructuring of the VAT Act, which is the main contribution of this study. The guidelines outline the universal principles that must be incorporated when simplifying the VAT Act. The guidelines include adhering to the lifecycle of a VAT vendor, which also follows the process that educators use to teach the VAT Act. The guidelines further include incorporating headings and subheadings, grouping complex sections together and avoiding inconsistency, i.e., sections should always be included under their logical section headings and contain clear signposting. In addition, local and international best practices must be incorporated. As a first step in the project to rewrite the VAT Act, the guidelines recommend the creation of a flow diagram or index. The rewriting of the VAT Act is a key recommendation following the creation of the index. The empirical findings of this research not only supplement the existing literature, but also add to it. For example, this study found that the working relationships between the revenue authority and policymakers as well as capacity constraints add to complexity of taxes.

It is recommended that the guidelines for a simplified VAT Act be applied practically to the Act in order to create an index that, if implemented, will improve the teaching of VAT to students, the interpretation and application of VAT by tax practitioners and the administration of the VAT Act by SARS officials. Ultimately, this will lead to increased VAT collection and reduced compliance costs. This is the initial step towards simplifying the VAT Act.

Declaration

This article is derived from the following doctoral thesis:

Hassan, M. E. (2023). A framework for a simpler Value-Added Tax Act [Doctoral thesis]. University of Johannesburg. Link: Awaiting publication

Ethical clearance

Prior to collecting primary data and conducting semi-structured interviews, the University of Johannesburg, School of Accounting Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval [Ethical clearance code: SAREC20220414/03].

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to:

the National Treasury for granting permission to interview staff;

SARS for granting permission to interview staff;

the SAIT for granting permission to interview members of the VAT Committee; and

SAICA for granting permission to interview members of the VAT Sub-committee.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2001). Tax policy concept: Guiding principles of good tax policy: A framework for evaluating tax proposals. Author.

- Babbie, E., & Mouton, J. (2001). The practice of social research. Oxford University Press.

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2014). Research methodology: Business and management contexts. Oxford University Press.

- Budak, T., & James, S. (2018). The level of tax complexity: A comparative analysis between the UK and Turkey based on the OTS index. International Tax Journal, 44(1), 23–36.

- Budak, T., Sawyer, A. & James, S. (2016). The complexity of tax simplification experiences from around the world. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cutts, M. (2013). Oxford guide to plain English. Oxford University Press.

- Davis Tax Committee. (2018). Report on the efficiency of South Africa’s corporate tax system. https://www.taxcom.org.za/docs/20180411%20Final%20DTC%20CIT%20Report%20-%20to%20Minister.pdf

- Dodwell, B. (2021, January 20). The OTS: The story so far. Tax Journal. https://www.taxjournal.com/articles/the-ots-the-story-so-far-

- Erard, B. (1993). Taxation with representation: An analysis of the role of tax practitioners in tax compliance. Journal of Public Economics, 52(2), 163–197.

- Fischer, M. H. (n.d.). Inspirational quotes at BrainyQuote. https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/martin_h_fischer_121669

- Kimble, J. (1996). Writing for dollars, writing to please. Scribes J. Leg. Writing,6, 1. HeinOnline. https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/scrib6§ion=5

- Le Roux, R., & Mia, H. (2020). The interpretation of tax legislation. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/za/en/pages/tax/articles/the-interpretation-of-tax-legislation.html

- Malla, M. A. (2016). An empirical study on the design and structure of Jammu and Kashmir State VAT: Traders’ perspective. Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, 7(1), 92–96.

- Marshall NO and Others v Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service (2018) CCT 208/17 ZACC 11.

- Mills, L., Erickson, M., & Maydew, E. (1998). Investments in tax planning. The Journal of the American Taxation Association, 20(1), 1–20.

- National Treasury. (2019). Regulation No. 429 – Value-Added Tax Act, 1991: Regulations Prescribing Electronic Services for the purpose of the Definition of “Electronic Services” in Section 1 of the Act, Notice No: 42316. Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Newberry, K. J., Reckers, P. M. J., & Wyndelts, R. W. (1993). An examination of tax practitioner decisions: The role of preparer sanctions and framing effects associated with client condition. Journal of Economic Psychology, 14(2), 439–452.

- Office of Tax Simplification. (2017). Office of Tax Simplification Complexity Index paper 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/603479/OTS__complexity_index_paper_2017.pdf

- Office of Tax Simplification. (2022). Update on the closure of the Office of Tax Simplification. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/update-on-the-closure-of-the-office-of-tax-simplification

- Petelin, R. (2010). Considering plain language: Issues and initiatives. Corporate Communications, 15(2), 205–216.

- Rai, N., & Thapa, B. (2015). A study on purposive sampling method in research. Kathmandu: Kathmandu School of Law, 5.

- Richardson, M. & Sawyer, A. (2001). A taxonomy of the tax compliance literature: Further findings, problems and prospects. Australian Tax Forum, 16(2):137–320.

- South African Institute of Chartered Accountants. (n.d.). About SAICA. https://www.saica.org.za/about

- South African Institute of Taxation. (2022). About us. https://www.thesait.org.za

- South African Revenue Service (SARS). (2021). Interpretation notes. Available from: https://www.sars.gov.za/legal-counsel/legal-counsel-archive/interpretation-notes/

- South African Revenue Service. (n.d.). Find a guide. https://www.sars.gov.za/legal-counsel/legal-counsel-publications/find-a-guide/

- South African Revenue Service. (2016). Binding General Ruling (VAT): No. 28 (Issue 2), Electronic services. https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Legal/Archive/BGRs/Legal-Arc-BGR-28-02-Electronic-Services-Issue-2-archived-10-February-2023.pdf

- South African Revenue Service. (2019). Legal Council: Value-added tax. Frequently Asked Questions: Supplies of electronic services. https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Ops/Guides/LAPD-VAT-G16-VAT-FAQs-Supplies-of-electronic-services.pdf

- South African Revenue Service. (2022). External guide: Foreign suppliers of electronic service. https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Ops/Guides/VAT-REG-02-G02-Foreign-Suppliers-of-Electronic-Services-External-Guide.pdf

- Saw, K. S. L., & Sawyer, A. (2010). Complexity of New Zealand’s income tax legislation: The final instalment. Australian Tax Forum, 25(2), 213–245.

- Sawyer, A. (2013). Reviewing tax policy development in New Zealand: Lessons from a delicate balancing of ‘law and politics.’ Australian Tax Forum, 28(2), 401–425.

- Sawyer, A. (2023). Vale the Office of Tax Simplification: Is its abolition an ill-informed decision? British Tax Review, 1, 1–8.

- Smaill, G. (2021). Taxation law drafting review and recommendations. Greenwood Roche Project Lawyers.

- Republic of South Africa. (1991). Value-Added Tax Act (Act No. 89 of 1991) (as amended). Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Republic of South Africa. (2011). Tax Administration Act (Act No. 28 of 2011) (as amended). Government Printer.

- Sulaiman Umar, M., & Saad, N. (2015). Readability assessment of Nigerian Company Income Tax Act. Jurnal Pengurusan, 44, 25–33.

- Tan, L. M., & Tower, G. (1992). The readability of tax laws: An empirical study in New Zealand. Australian Tax Forum, 9(3), 355–372.

- Thuronyi, V. (1996). Tax law design and drafting (Vol. 1). Washington DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Tran-Nam, B. (1999). Tax reform and tax simplification: Some conceptual issues and a preliminary assessment. The Sydney Law Review, 21(3), 500–522.

- Tran-Nam, B., Oguttu, A., & Mandy, K. (2019). Overview of tax complexity and tax simplification: A critical review of concepts and issues. In C. Evans, R. Franzsen, & E. Stack (Eds.), Tax simplification: An African perspective (pp. 8–38). Pretoria University Law Press.

- Whiting, J. (2019). Tax simplification in the United Kingdom: Some personal reflections. In C. Evans, R. Franzsen, & E. Stack (Eds.), Tax simplification: An African perspective (p. vii-xx). Pretoria University Law Press.

- Young, G. J. (2021). An analysis of ways in which the South African tax system could be simplified [Masters dissertation]. Rhodes University.