ABSTRACT

This special issue brings together a range of policy and research trends regarding COVID-19 Crisis, Work and Employment (CWE). Under the assumption that crises, disasters, emergencies are impediments to the broader Sustainable Development agenda, a rapid bibliometric analysis of CWE literature between 2020 and 2021 was also carried out as an antecedent to highlight emerging contexts and perspectives. As a collection, this special issue draws attention to empirical insights and practical cases from around the world for understanding the way various stakeholders responded to support the economy, employees and others during the COVID-19 crisis.

Introduction

“The pandemic has brought unprecedented disruption that – absent concerted policy efforts – will scar the social and employment landscape for years to come” (International Labour Organisation [ILO] Citation2021, 11)

The novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has spread globally with, at the time of writing, over 180 million cases, over 4 million deaths and close to 500 thousand new cases per day (Johns Hopkins University Citation2021) leading to disruption of the international economy. The speed and intensity of the crisis has been unprecedented, resulting in businesses being closed, increasing unemployment and underemployment, lockdowns, curfews, the collapse of global supply chains and international and national travel being curtailed or declining (Wheatley et al. Citation2021). Howe et al. (Citation2021) report on the 2020 Australian Business Statistics data stating ‘ … no occupation was spared from the adverse effects of COVID-19, but employment losses were concentrated in lower-skill occupations’ (p. 135). Some industries, such as tourism, airlines, high street retailing, and accommodation have been severely disrupted. Other sectors like health, security, and logistics have had increased demands placed on them, while sectors, such as education and retail, have been forced to adopt various (and sometimes new) technologies to perform their functions. While there have been crises previously such as disasters and emergencies including fires, floods, and earthquakes; and financial failures such as the global financial crisis (GFC), which have forced government, communities, and organisations to make short-term adjustments to employment and working conditions, these are generally one-off and location specific (Burgess and Connell Citation2013).

One of the major differences with the COVID-19 crisis has been the mandating and implementation of working from home (WFH) arrangements that have been enforced by lock downs and travel exclusions, and supported by technology (Wheatley et al. Citation2021). Employment regulations, including workplace agreements have been amended to accommodate new working arrangements (Dayaram and Burgess Citation2021). Consequently, a dichotomy has developed between the global, online world and the local and restricted, offline world, with populations confined to a region or city. Communication, business, employment, and entertainment are being maintained at arm’s length and/or virtually through digital technologies (World Economic Forum WEF Citation2020). Many governments have extensively intervened to support their economies, employers and employees through subsidies, support payments for businesses and workers, and increases in welfare payments (Spies-Butcher Citation2020). Rebuilding economies and workplaces, post COVID-19, will require enormous effort, resources, and expertise. Predictions as to the efficiency and effectiveness of recovery are unknown, although Tirole (Citation2020, webpage) posits that an optimistic scenario, may mean that ‘an economic stimulus will facilitate the transition back to normal, boosted by the budgetary and monetary efforts already underway’. That said, he cautions that we should ‘take advantage of the pandemic to act on social norms and incentives together … working towards a less individualistic, more compassionate society’.

To achieve such outcomes, it is important to examine the ongoing changes in work and labour regulation, the details and challenges associated with the recovery from COVID-19, and readiness for future pandemics. Until now, governments have equated the national ‘good’ with economic growth, yet in a short space of time this approach has changed to focus on the safety and well-being of the community, recognising that, in the longer-term, growth prospects will be improved if communities are healthy. It remains to be seen whether, post COVID-19, economies, organisations, and workers can return to ‘business as usual’. Over the course of the pandemic there have been inequities and gaps in the systems of protection and support. Some of the most vulnerable workers, such as those on casual contracts and gig workers were forced to work to survive (although in New Zealand Job Keeper payments included temporary visa workers); while other frontline workers, such as those in health, worked under potentially hazardous conditions. The support ‘safety nets’ offered in Australia have excluded some industries, contrasting with the government sentiment of us ‘all being in it together’ while in some cases being awarded to firms that have been unaffected by the pandemic (Barber and Law Citation2020). Richardson (Citation2020, 9) proposes that, where businesses receiving the Australian Jobkeeper support payments made a profit, the payment should be paid back ‘by making it taxable at a much higher rate than other business income’. Moreover, Hamilton (Citation2020) advocates that key stakeholders (governments, businesses, non-profits, and others) should come together and collectively promote the equitable workplace, especially for the most vulnerable. To address a range of these challenges this special issue volume examines the work and industrial relations nexus in the context of the ongoing disruption generated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This special issue follows on from the 2020 collection that was linked to the 2020 AIRAANZ Conference held in Queenstown, New Zealand. On that occasion the theme of the conference and the special issue was Doing things differently? IR practice and research beyond 2020. This was one of the last in person conferences before the global spread of COVID and the subsequent disruption to all aspects of people’s lives. The editors of the special issue stated that “the overarching theme throughout the conference, and which permeates the selected papers, addresses equity. This was reflected in issues such as ‘ongoing inequalities in the labour market and economy, both locally and internationally; the inherent and prevalent challenges associated with addressing global and local social inequities; and the intersectionality and dynamism of equity issues” (O’Kane et al. Citation2021, 1). The articles covered the challenges of climate change (Douglas and McGhee Citation2021); migrant workers (Faaliyat et al. Citation2021), and sex workers (Tyler Citation2021). This collection follows on from those themes with the benefit of another 12 months experience of the impact of COVID-19 in the world of work and employment. In that time the interventions and regulations imposed by the State have intensified across many countries as authorities seek to prevent the transmission of the virus and to protect public safety.

At this stage of the experience, in Australia and New Zealand, the focus is towards mass vaccination and developing an integrated process towards re-opening economies and encouraging a return to face-to-face work. However, it is debateable whether work and employment arrangements will be the same as before the pandemic and follow a return to ‘normalcy’. For example, a series of interviews and focus groups with Australian-based HRM professionals conducted by Larkin et al. (Citation2021) revealed that many HR managers believe there would be long-lasting effects of the pandemic, including a greater uptake in technology/software at the workplace to both replace and augment labour, and the embedding of WFH arrangements. The pandemic provided the opportunity for many organisations to accelerate changes to work and work practices that had previously been constrained by organisational inertia, or by regulatory barriers. For some organisations another positive development was greater cooperation and goodwill between management and trade unions. Conversely, in some industries there were reports of opportunism on the part of organisations attempting to dilute workplace conditions, intensify work, and re-negotiate workplace agreements (see Vassiley and Russell, this issue).

Work and employment during crisis

Crises, disasters, emergencies are impediments to the broader Sustainable Development agenda (see UN, Citation2015; Han and Waugh Citation2018). In the last decade, apart from the COVID-19, there have been various disasters and emergencies around the world including but not limited to volcanic eruptions (Iceland, Indonesia, Spain), earthquakes (Haiti, Nepal, Philippines); extensive forest fires (Greece, Russia, USA) and flooding (Australia, Germany, USA); political conflicts (Afghanistan, Myanmar, Syria); and economic crisis (Greece, Spain, USA). Although the three different terms disaster, crisis and emergency are often used interchangeably in the literature (Al-Dahash et al., Citation2016, August), there are granulated differences with disruption as a common thread. First, disaster is a sudden and calamitous event, manmade or natural, that triggers significant disruption to the functioning of an organisation or a community warranting a response that can accelerate recovery and resilience (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNODRR) Citation2005). Second, emergency can be described as a state in which normal procedures are disrupted or suspended and extraordinary actions are taken to safeguard people and property (Alexander Citation2003). Third, crisis is an unexpected problem that seriously disrupts the functioning of an organisation or a society and necessitates an urgent response under conditions of deep uncertainty (Shaluf and Said Citation2003).

It is clear that, just like the climate emergency, the COVID-19 pandemic is an ongoing crisis that has disrupted normalcy and had unpredictable affects warranting concerted responses from individuals, organisations, and nations. Scholars have contended that despite growing attention to manage crisis and responses to mitigate adverse impacts on organisations, little attention has focused on the dynamics of work and employment during crises (see Donnelly and Proctor‐Thomson Citation2015). The ability to respond to and recover from crisis will depend on the scale of the disruption and the supporting infrastructure and capacity to respond. Here, there are considerable differences across countries in terms of capacity. On the one hand, in poor, developing economies, the scale of crisis can not only place strains on limited infrastructure and on the financial capacity for dealing with disruption, but they can also destroy the available work and employment ecosystems. For example, this was the case with the crisis in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake that led to 9 thousand deaths and wounded over 22,000 people (Dhakal Citation2018). More importantly, the capacity of the country to generate work and employment opportunities was severely crippled by the fact that the country was in recovery from two decades of civil war (Dhakal and Burgess Citation2021). On the other, developed economies are better equipped to tackle the economic crisis, whether it is regional i.e., the 1997 Asian Financial crisis) or international i.e., the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (see Burgess and Connell Citation2013). For example, although the economic crisis in Greece accelerated longer term industrial relations trends including falling trade union membership and led to wage cuts, job losses, pay freezes, welfare cuts, and reduced redundancy payments, and greater flexibility in employment conditions (Carassava Citation2018), it had been showing promising signs of recovery in terms of creating employment opportunities (Wolf Citation2019) prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

There is no doubt that rebuilding economies and workplaces post COVID-19 will require enormous effort, resources, and expertise – not just financial resources. Potentially there is scope for addressing deep seated inequalities and exclusions that were partially acknowledged by some of the policy responses to COVID. Winton and Howcroft (Citation2020) propose this re-evaluation could lead to policies that ensure that key workers are paid and protected in a way that reflects their critical contribution to society. This special issue examines a range of policy and research trends regarding COVID, Work and Employment. Specifically, we ask how various stakeholders have responded to support the economy, employees and others during the COVID-19 induced pandemic? It is important to consider the roles of various stakeholders, such as governments, industry and universities while moving forward towards recovery. It is in this context, the next section outlines the research methods (and findings) used to identify current academic research on COVID, work and employment using a rapid bibliometric analysis.

Rapid bibliometric analysis of literature on ‘COVID, work and employment’

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have been examining its impact on all sectors. More importantly, an examination of the impact on jobs, working and workplaces has been an important part of ongoing research. Under the assumption that an analysis of ‘COVID-19, Work and Employment’ [CWE] related literature can capture emerging research trends, a rapid bibliometric analysis [RBA] was conducted to inform this article. While bibliometrics generally focus on assessing the magnitude and scope of literature in a particular field or subfield of research (see Hood and Wilson Citation2001; Donthu et al. Citation2021), we propose that RBA also allows researchers to capture emerging research themes and their impacts on the CWE nexus in an iterative and expeditious manner. Drawing on Mahmood and Dhakal (Citation2021), a two-staged RBA process was adopted. This comprised: i) the extraction and screening of literature from the Scopus database using a reproducible search code (), and ii) the utilisation of two different types of software: Microsoft Excel and the VOSviewer. These processes enabled the generation of summary tables and/or visual maps concerning the number of publications; prominent countries, authors, and outlets; and co-occurrence of various topics. identifies the full search code used in Scopus to identify relevant publications.

The literature search in Scopus was conducted on 9 September 2021 and yielded 337 research outputs. Research outputs on the CWE agenda, as expected, more than doubled in 2021 (n = 230) when compared to 2020 (n = 107) across four subject areas: Social Sciences, Business Management and Accounting, Economics, Econometrics and Finance, and Multidisciplinary. 323 of the 337 outputs were journal articles and the remainder comprised book series (n = 6), books (n = 4), and conference proceedings (n = 4).

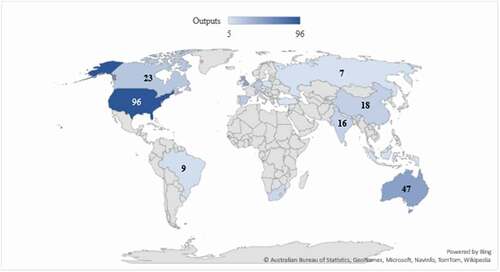

illustrates the main contributing journals with at least four published articles being CWE focused. The journal ‘Plos One’ published the most journal articles (n = 25), followed by ‘Sustainability Switzerland’ (n = 14), and ‘Gender Work and Organization’ (n = 13). In terms of the country/territory of the authors, the United States of America had the most outputs (n = 96), followed by Australia (n = 47) and the United Kingdom (n = 47). shows the full extent of countries/territories represented with at least five research outputs.

Table 1. Contributing journals on CWE related themes between 2020 and 2021 (n ≥ 4)

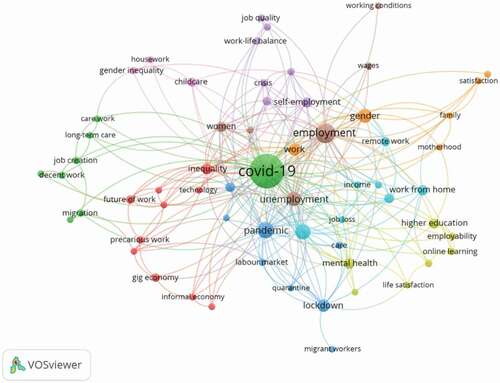

The core content and range of research themes represented in publications on the CWE agenda can be identified through the co-occurrence of keyword analysis. In the VOSviewer a total of 1059 keywords were extracted from the Scopus dataset. With the minimum number of occurrences set to the default value of three, 67 keywords met the threshold value. The analysis revealed nine different clusters with various research themes (see ). For example, the first cluster includes 10 research themes: future of work; gig economy; inequality; informal economy; labour; precarious work; public policy; sustainability; technology; and universal basic income. The last cluster included three research themes: childcare; gender inequality and housework.

With three research outputs each, Churchill (University of Melbourne), Collins (Washington University), and Ruppanner (University of Melbourne) tied for the top spot of prominent researchers in terms of published outputs. summarises the most influential articles on the topics searched based on the citation count.

Table 2. Most influential papers on CWE (Citations ≥ 50)

The most cited studies, as outlined in , reveal two interesting patterns and commonalities. First, and not surprisingly, the top cited research is within the context of developed countries, and specifically, North America and Europe. In terms of recorded COVID infections, high rates of infection have been spread across developed countries (USA, UK, and Spain) and developing countries (Brazil, Philippines, India, Turkey). Second, methods are dominated by quantitative research, with an emphasis on statistically estimating the impact of COVID across a range of indicators. This special issue deviates from these norms in that the countries covered include those from outside Europe and North America, some of the studies employ qualitative research and the issues covered extend to labour regulation, training and skill development, as well as the positioning of employment relations research.

The organisation and contribution of this SI

The rapid bibliometric analysis identified the emergence of CWE related research themes. The 7 most popular themes emerging from the RBA: the future of work; gig economy; inequality; informal economy; labour; precarious work; public policy; sustainability; technology; and universal basic income are highly pertinent to the topics researched in this volume and most feature in the articles. The countries represented in the articles in this volume include developed (Australia, Norway) and developing (India) economies. Generic articles are also included that address the impact of COVID-19 on labour globally, and on employment relations research. Each study examines different issues and policy responses in the context of COVID-19 impacts using a range of different research methods.

The articles are organised as follows – the first focuses on climate change and policy responses in relation to the world of work and beyond COVID-19. The next two articles analyse pay and contracts. The first is on contracts, specifically non-standard employment relationships and the COVID-19 consequences in Norway and the second is on minimum wage regulation in Australia in the wake of the pandemic. The next three articles focus on higher education (HE) – one on the development of post-pandemic workplace skills in HE, the next on employment relations research and HE and the third with an HE context concerns the National Jobs Protection Framework (NJPF) proposed by the National Tertiary Education Union. The final article concerns a mediation analysis of reactions to COVID-19, social media engagement and well-being providing a range of topics and contexts in relation to the main themes of the special issue. The next section briefly introduces each of the articles.

The first article by Dean and Rainnie (this issue) examines the COVID-19 crisis on labour globally and the potential policy responses, within the context of the global warming crisis. The context is Australia, and the approach is critical policy analysis. Examining a range of proposed policy solutions for Australia from environmental think tanks, the authors highlight the inherent contradictions between more jobs (ongoing economic growth) and effective environmental action. The authors suggest that the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, which is already backgrounded by the influence of the ongoing climate crisis, has revealed the tensions between growth programs, incorporating green objectives, that have been superimposed on an economic structure that incorporates extreme inequalities across and within nations.

The second article by Ingelsrud (this issue) explores how the work-related consequences of COVID-19 in Norway varied between workers in different employment arrangements. From a survey of employees, the statistical analysis of the data compared temporary and self-employed workers with permanently employed workers, and those in voluntary and involuntary part-time positions with full-time workers. The results indicate that the self-employed had a higher likelihood of experiencing reduced working time and income loss whereas those in temporary employment did not experience a higher likelihood of any measured outcomes. Part-time workers had a higher chance of income loss and a lower chance of being directed to work from home than full-time workers and employees in part-time positions had a higher likelihood of having reduced working hours. The findings are considered with respect to flexibility and risk highlighting how standard jobs provide the foundation for work regulation and welfare policy. Despite the government’s efforts to increase the safety nets for workers outside of standard employment, the results indicate that the coverage was not wide enough overall.

Next, Hamilton and Nicol (this issue) highlight the importance of Australia’s minimum wage for low paid workers during the concurrent crises of wage stagnation and the COVID-19 pandemic. Under consideration is whether, in this current regulatory paradigm, the minimum wage will be able to continue its history of fulfiling its social, economic, and industrial objectives. The authors review the minimum wage principles that have applied in Australia to date including assessing the needs of workers, the capacity of employers to pay, and the function of the minimum wage as a safety net. Maintenance of the high level of the minimum wage and whether any groups of workers are left behind are key issues to address in assessing the future of minimum wage regulation.

Bayerlein, Hora, Dean and Perkiss (this issue) explore how the rise of technology-based distributed work arrangements impact the knowledge, skills, and competencies that university graduates need to succeed in the post-COVID-19 work environment. The article examines the nature of future workforce challenges faced by graduates. The authors suggest that the interactions between digital workplace preparation and real-world work experiences should inform the future university curricula arguing that there is a need to improve the alignment of higher education and the word of work through developing (digital) WIL models that are aligned with and driven by employer organisations.

Hodder and Lucio (this issue) examine the implications of COVID-19 for the field of employment relations within advanced economies through a research note. The authors suggest that COVID demonstrates the resilience of employment relations, through its critical relevance to analysing and understanding work, workplaces, working conditions, and workplace relations. The article discusses the challenges faced by academics in higher education (HE) and practitioners in employment relations concerning the maintenance, authority and centrality of the discipline that has been conferred through COVID.

Vassiley and Russel examine the National Jobs Protection Framework (NJPF) in the Australian higher education sector. The Australian government’s Jobkeeper program was introduced to support jobs but was selectively applied and excluded the higher education sector. As a result, universities reduced costs primarily through job losses and diluted employment conditions. The National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) responded with a concession-bargaining strategy, offering university management a National Jobs Protection Framework (NJPF), which traded pay reductions for job security measures. The article outlines the development, and eventual collapse of the NJPF, following its rejection by rank-and-file members of the union. Through an analysis of concession bargaining and the NTEU experience, the authors suggest an alternative industrial strategy to deal with the crisis within the industry.

Finally, Khatri Raina, Dutta, Pahwaa, and Kumari argue that COVID-19 has increased employee anxiety and stress, and in this context, social media has an important role to play in providing informational, emotional, and community support to workers who in many cases were isolated and removed from the workplace. Based on a survey of employees in the hospitality and IT sectors in India, the authors propose a model and explore the relationship between pandemic reactions, social media engagement, and employee well-being. Based on the findings, the authors contend that placing social media at the centre of employee well-being strategies is vital in this pandemic and the post-pandemic hybrid workplace.

Concluding remarks

The COVID-19 crisis is different from the natural, financial, and human crises in that its impact is global, not isolated to one or a few countries, and it is ongoing. Global recovery will be uneven, given the limited financial and institutional capacity across countries to accommodate crisis, together with the uneven distribution and access to vaccines. Unexpected consequences from the COVID-19 experience to date include: the failure of global supply chains (Ivanov Citation2020); the reduction in international and national migration from border closures (Guadagno Citation2020) and reconsideration of the need for centralised and rental/infrastructure in relation to expensive real estate in central business districts in large cities that are dependent upon commuting workforces (Rosenthal et al. Citation2021). However, the COVID-19 crisis has extended beyond a consideration of the impact on employment and core employment conditions, such as pay and performance. Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, the climate change crisis was also evident. In some cases, the climate crisis has exacerbated the COVID-19 health risks since as, Salas et al. (Citation2020) argue the risks are ‘greater when weather events are more intense, since widespread catastrophic damage results in mass displacement, which risks introducing the virus into new locales and clustering vulnerable survivors together in temporary accommodation’ (p. 1).

The rapid bibliographic analysis illustrated that a number of these themes were prevalent research topics in the cluster and were also covered in the SI articles, for example, inequality, precarious work and the informal economy. The findings highlight UNDESA’s (Citation2021) position that the COVID-19 crisis has: ‘exposed and exacerbated the weaknesses that persist because of the lack of progress in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ (p. 2). More importantly, the articles in this special issue also assist in deepening our understanding in relation to the topics covered but, at this stage with the pandemic and climate change crisis still apparent, there are more questions than answers remaining. So, what do these issues mean for the future? As Howe et al. (Citation2021, 238) point out ‘the evidence on how COVID-19 is impacting work and labour markets is somewhat mixed – and definitely incomplete – with few systematic, well-designed field studies from which we can draw firm conclusions’. Consequently, there is a need for ongoing research to be conducted on these topics for some time to come.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdullah M, Dias C, Muley D, and Shahin M. 2020. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 8: 100255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100255

- Al-Dahash, H., Thayaparan, M., and Kulatunga, U. (2016, August). Understanding the terminologies: disaster, crisis and emergency. In Chan, P. W. and Neilson, J. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM conference, Vol 2 (1191-1200). Manchester UK. https://www.arcom.ac.uk/-docs/archive/2016-ARCOM-Full-Proceedings-Vol-2.pdf

- Alexander, D. 2003. “Towards the Development of Standards in Emergency Management Training and Education.” Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 12 (2): 113–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560310474223.

- Baker, M. G., Peckham, T. K., and Seixas, N. S. 2020. Estimating the burden of United States workers exposed to infection or disease: a key factor in containing risk of COVID-19 infection. PloS one 15 (4): e0232452.

- Barber, R., and S. F. Law. 2020. “Exposing Inequity in Australian Society: Are We All in It Together?” Social and Health Sciences 18 (2): 96–115.

- Baum, T, and Mooney, S. K., Robinson, R. N., and Solnet, D. 2020. COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce–new crisis or amplification of the norm? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32 (9): 2813–2829.

- Burgess, J., and J. Connell. 2013. “The Asia Pacific Region: Leading the Global Recovery Post GFC?” Asia Pacific Business Review 19 (2): 279–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2013.767641.

- Carassava, A. 2018. “Greeks Stuck in Lousy, Part-time Jobs as Government Claims Success.” https://www.dw.com/en/greeks-stuck-in-lousy-part-time-jobs-as-government-claims-success/a-42220857

- Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., and Scarborough, W. J. 2021. COVID‐19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 101–112.

- Craig , L., and Churchill, B. 2021. Dual‐earner parent couples’ work and care during COVID‐19. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 66–79.

- Dayaram, K., and J. Burgess. 2021. “Regulatory Challenges Facing Remote Working in Australia.” In Handbook of Research on Remote Work and Worker Well-being in the post-COVID-19 Era, edited by D. Wheatley, I. Hardill, and S. Buglass, 202–220. Hershel: IGI Global.

- Del Boca D, Oggero N, Profeta P, and Rossi M. 2020. Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Rev Econ Household 18(4): 1001–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09502-1

- Dhakal, S. P., and J. Burgess. 2021. “Decent Work for Sustainable Development in Post‐crisis Nepal: Social Policy Challenges and a Way Forward.” Social Policy & Administration 55 (1): 128–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12619.

- Dhakal, S. P. 2018. “Analysing News Media Coverage of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake Using a Community Capitals Lens: Implications for Disaster Resilience.” Disasters 42 (2): 294–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12244.

- Dingel, J. I, and Neiman, B. 2020. How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics 189: 104235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

- Donnelly, N., and S. B. Proctor‐Thomson. 2015. “Disrupted Work: Home‐based Teleworking (Hbtw) in the Aftermath of a Natural Disaster.” New Technology, Work and Employment 30 (1): 47–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12040.

- Donthu, N., S. Kumar, D. Mukherjee, N. Pandey, and W. M. Lim. 2021. “How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines.” Journal of Business Research 133: 285–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070.

- Douglas, J., and P. McGhee. 2021. “Towards an Understanding of New Zealand Union Responses to Climate Change.” Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 31 (1): 28–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1895483.

- Dube, K., Nhamo, G., and Chikodzi, D. 2021. COVID-19 cripples global restaurant and hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism 24 (11): 1487–1490.

- Faaliyat, N., S. Ressia, and D. Peetz. 2021. “Employment Incongruity and Gender among Middle Eastern and North African Skilled Migrants in Australia.” Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 31 (1): 47–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1878571.

- Guadagno, L. 2020. Migrants and the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Initial Analysis. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- Hamilton, A. 2020. “Imagining Life after COVID-19.” accessed 3 April 2020. https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2020/03/imagining-life-after-COVID-19-19/

- Han, Z., and W. L. Waugh. 2018. “Special Issue ‘Disasters, Crisis, Hazards, Emergencies and Sustainable Development’.” https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/Disasters-Crisis_Hazards_Emergencies_Sustainable_Development?view=default&listby=date#published

- Hood, W. W., and C. S. Wilson. 2001. “The Literature of Bibliometrics, Scientometrics, and Informetrics.” Scientometrics 52 (2): 291–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017919924342.

- Howe, J., J. Healy, and P. Gahan. 2021. “The Future of Work and Labour Regulation after COVID-19.” Australian Journal of Labour Law 34: 130–145.

- International Labour Organisation [ILO]. 2021. World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2021. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_794834/lang–en/index.htm

- Ivanov, D. 2020. “Predicting the Impacts of Epidemic Outbreaks on Global Supply Chains: A Simulation-based Analysis on the Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19-19/sars-cov-2) Case.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 136: 101922. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.101922.

- Johns Hopkins University. 2021. “Corona Virus Resource Centre.” https://coronavirus.jhu.edu

- Kecojevic, A., Basch, C. H., Sullivan, M., and Davi, N. K. 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PloS one 15 (9): e0239696.

- Larkin, R., J. Connell, and J. Burgess. 2021. “Fourth Industrial Revolution & the Future Workforce: Implications for HRM, Report Prepared for the Australian Human Resources Institute.” accessed 1 October 2020. www.ahri.com.au/resources/ahri-research

- Lenzen, M., Li, M., and Malik, A., Pomponi, F., Sun, Y. Y., Wiedmann, T., . and Yousefzadeh, M. 2020. Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PloS one 15(7): e0235654.

- Mahmood, M. N., S. P. Dhakal. 2021. “A Bibliometric Analysis of Ageing Literature: Global and Asia-Pacific Trends.” In Ageing Asia and the Pacific in Changing Times: Implications for Sustainable Development (Chapter 3), edited by Dhakal, et al. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Morrow-Howell, N, Galucia, N, and Swinford, E. 2020. Recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on older adults. Journal of aging & social policy 32(4-5): 526–535.

- O’Kane, P., K. Ravenswood, J. Douglas, F. Edgar, and J. Parker. 2021. “Doing Things Differently: IR Practice and Research beyond 2020.” Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 31 (1): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1911041.

- Restubog, S Lloyd, Ocampo A Carmella, and Wang L. 2020. Taking control amidst the chaos: Emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119: 103440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103440

- Richardson, D. 2020. “JobKeeper: A Proposal for Clawing Back Unnecessary Spending.” https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=a4b1145d-2efb-40b3-a4ff-a8c218c3a589

- Rosenthal, S. S., W. C. Strange, and J. A. Urrego. 2021. “JUE Insight: Are City Centers Losing Their Appeal? Commercial Real Estate, Urban Spatial Structure, and COVID-19.” Journal of Urban Economics 103381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2021.103381.

- Salas, R. N., J. M. Shultz, and C. G. Solomon. 2020. “The Climate Crisis and COVID-19—a Major Threat to the Pandemic Response.” New England Journal of Medicine 383 (11): e70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2022011.

- Shaluf, I. M., and A. M. Said. 2003. “A Review of Disaster and Crisis.” Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 12 (1): 24–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560310463829.

- Spies-Butcher, B. 2020. “‘The Temporary Welfare State: The Political Economy of Job Keeper, Job Seeker and “Snap Back”.” Journal of Australian Political Economy 85: 155–163.

- Tirole, J. 2020. “Rebuilding the World after COVID-19-19.” accessed 3 April 2020 https://www.tse-fr.eu/rebuilding-world-after-COVID-19-19

- Tyler, M. 2021. “All Roads Lead to Abolition? Debates about Prostitution and Sex Work through the Lens of Unacceptable Work.” Labour & Industry 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2020.1847806.

- United Nations (UN). 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1.” New York. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Economic Analysis (UNDESA). 2021. “World Economic Situation and Prospects.” February 2021. Briefing, No. 146. New York.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNODRR). 2005. “Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters.” Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development, UN. ( 2015). A/RES/70/1. New

- Wheatley, D., I. Hardill, and S. Buglass. 2021. “Preface: The Rapid Expansion of Remote Working.” In Handbook of Research on Remote Work and Worker Well-Being in the Post-COVID-19 Era, edited by D. Wheatley, I. Hardill, and S. Buglass, xix–xxxiii. Hershel: IGI Global.

- Winton, A., and D. Howcroft. 2020. “What COVID‐19 Tells Us about the Value of Human Labour.” https://policyatmanchester.shorthandstories.com/value‐of‐human‐labour

- Wolf, M. 2019. “Greek Economy Shows Promising Signs of Growth.” https://www.ft.com/content/b42ee1ac-4a27-11e9-bde6-79eaea5acb64

- World Economic Forum (WEF). 2020. “How Next-generation Information Technologies Tackled COVID-19 in China.” accessed 3 April 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/how-next-generation-information-technologies-tackled-COVID-19-19-in-China