ABSTRACT

The critical frontline work of doctors in Pakistan was overlooked and undervalued by the government, hospitals, and the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Media reports and studies highlight that public sector doctors in Pakistan facing new societal, professional, and organisational challenges, compounding to the inherent demands of work potentially leading to its undervaluation. This study, explores how the work of doctors is (under)valued in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals, and how this aligns to the underpinnings of decent work. 27 semi structured in-depth interviews were conducted with doctors in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals. We found that serving others, recognition and appreciation, and professional learning and development were valuable aspects, while flaws in the healthcare system, issues from patients and public, poor work environment, a lack of essential health facilities, and physical and mental health challenges associated with work were considered factors which undervalue the work for doctors. Drawing on the intersect between the concept of decent work and psychology of working theory, we establish a value framework for decent work that aligns with its psychological and sociological dimensions. Based on the findings we offer policy and practice implications ensuring the provision of decent work to public sector doctors in Pakistan.

Introduction

COVID-19 profoundly impacted personal and working lives globally, and Pakistan was no exception. As of 13 April 2023, the nation recorded 1,580,021 confirmed cases and 30,652 deaths (WHO Citation2023). Characterised as a country with relatively underdeveloped health infrastructure (Arshad et al. Citation2016; Khalid and Ali Citation2020), Pakistan’s healthcare challenges were magnified during the pandemic, affecting both the public and healthcare professionals in numerous ways (Ali et al. Citation2021; Khalid and Ali Citation2020). Doctors and frontline healthcare workers, in particular, found themselves highly vulnerable during this period, continuing to grapple with pandemic’s after-effects (Buowari Citation2022; Pandey and Sharma Citation2020; Simons and Baldwin Citation2021). Their unwavering commitment to safeguarding public health entailed significant sacrifices in terms of their own physical and mental wellbeing (Atif and Malik Citation2020; Shaukat et al. Citation2020). For example, Elliott et al. (Citation2022) highlighted that doctors faced heightened infection risks due to increased exposure, alongside profound impacts on their mental health.

Besides health and wellbeing challenges, healthcare professionals contended with issues related to safe working conditions, work-life balance and societal perceptions of their roles (Ali et al. Citation2021; Khalid and Ali Citation2020; Simons and Baldwin Citation2021). For example, Amanullah and Shankar (Citation2020) and Buowari (Citation2022) noted that many doctors and healthcare workers experienced poor job satisfaction, depression, panic, isolation, burnout, emotional exhaustion, insomnia, and anxiety throughout the pandemic.

Recent studies and media reports have highlighted a range of societal, governmental, and organisational level factors affecting the work of doctors in Pakistan. Particularly acute in the public sector hospitals were concerns regarding insufficient personal protection equipment, inadequate occupational safety measures, lack of epidemic management training, staffing issues, and a scarcity of medicines and tools (Atif and Malik Citation2020; Khalid and Ali Citation2020; Khan Citation2020; Yousafzai Citation2020). Additionally, pressure from the government to work without the required safety gadgets, overwhelming patient influx, overcrowded medical facilities, weak healthcare infrastructure, and political influences further compounded the challenges (Ali et al. Citation2021; Shaukat et al. Citation2022).

Beyond systemic and regulatory shortcomings, various social factors exacerbate the difficulties faced by doctors. For example, public demurrals, conspiracy theories implicating doctors, reliance on faith healers, socio-religious beliefs about the pandemic, widespread ignorance due to low literacy rates, particularly in rural areas, and the stigmatisation of healthcare workers (Atif and Malik Citation2020; Rana et al. Citation2020; Razu et al. Citation2021). Ironically, several doctors who voiced concerns during this period faced arrest, physical assault, and were denied risk compensation and other incentives despite their frontline role in combating the pandemic (Dawn Citation2022; The Guardian Citation2020; Hakim et al. Citation2021). These factors not only jeopardised the physical and psychological health of public sector doctors but also profoundly impacted their experiences of decent work, encompassing motivation and sense of meaning, and the right to safe working conditions (Ferraro et al. Citation2018, Citation2020; International Labour Organization Citation2015). Such challenges essentially undermine the standards of decent work in Pakistan, including fundamental values and principles at work, adequate workload and working time, opportunities, health and safety, social protection (Ferraro et al. Citation2020; ILO Citation2022).

Understanding the value of work for doctors and its relation to the concept of decent work is crucial in the development and sustainability of quality healthcare (Denis and van Gestel Citation2016; Ferraro et al. Citation2020; Johnson and Butcher Citation2021; Tallis Citation2006). However, there is a notable gap in research exploring these concepts, particularly in the non-Western context of Pakistan. Understanding how the material conditions of work shape decent work is crucial, particularly when we consider that insufficient conditions can drive doctors to draw only on their own personal resources to experience purpose and meaning in their work. This is neither sustainable nor reflective of decent work. Accordingly, we aim to find answers to two research questions in this paper. First, ‘How does the value of work intersect with the concept of decent work?’ and second, ‘How does the value of work and related contextual factors manifest among public sector doctors in Pakistan?’

Drawing upon the tenets of psychology of working theory (Duffy et al. Citation2016) and elements of decent work (Ferraro et al. Citation2018; ILO Citation2022), this study explores how the work of doctors in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals is valued or undervalued in relation to decent work. An abductive approach was used, iteratively considering evidence from the data and existing literature on decent work. Thus, to understand the value of work in the broader framework of decent work, we engaged in a thorough review of the literature. This review facilitated an understanding of the psychological and sociological dimensions of work that resonate with the underpinnings of decent work. This further helped to identify elements that either enhance or contradict the degree to which doctors may experience intrinsic value in their work and examine how this aligns to decent work principles. The analysis provided important insight into the role of contextual factors in influencing the value of doctors’ work as well as the external working conditions. Consequently, we propose a range of policy and practice implications essential for ensuring conditions conducive to decent work for doctors in Pakistan.

Literature review

Value of work and decent work

There are different perspectives and definitions of value. The psychological perspective explains value as, ‘satisfaction, enjoyment, an attitude taken up towards an object which is valued’ or ‘being an object for feeling or conation, or affective and conational disposition’ as mentioned in Osborne (Citation1931 p.436). According to Gesthuizen et al. (Citation2019) and Hauff and Kirchner (Citation2015), work values are multidimensional as having intrinsic and extrinsic elements. Intrinsic values are content-related values of work that refer to an array of outcomes individuals associate with the work itself, such as a sense of fulfilment, meaningfulness, and self-actualisation. Extrinsic values of work are context-related and relate to economic benefits, security, relationships, and other tangible outcomes (Gesthuizen et al. Citation2019; Krumm et al. Citation2013). Based on these explanations, this paper uses the term ‘value’ to encompass elements that either enhance or diminish the significance of the work for doctors.

The concept of values holds prime importance in the conceptualisation of decent work. The concept of global decent work, as articulated by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), is encapsulated in its four strategic objectives, as outlined by Somavia (Citation1999). These objectives are integral to one of the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, set forth in 2015, which emphasise rights at work, full and productive employment, social protection, and the promotion of social dialogue (UN Citation2015). As detailed in the ILO’s (Citation2022) report, these pillars form the foundation of decent work on a global scale. These four basic principles have been further presented as ten substantive elements of decent work including, employment opportunities, adequate earnings and productive work, decent working time, combining work, family and personal life, work that should be abolished, stability and security of work, equal opportunity and treatment in employment, safe work environment, social security, and social dialogue, employers’ and workers’ representation.

Building upon this foundational framework, various studies have expanded the traditional understanding of decent work by operationalising its core principles to examine how they apply in diverse working environments. For instance, research by Duffy et al. (Citation2017) and Ferraro et al. (Citation2018) has reinterpreted the ILO’s concept of decent work from both macro-economic and psychological perspectives. The models of Duffy et al. (Citation2017) and Ferraro et al. (Citation2018) are an extension of the psychology of working theory initially formulated by Duffy et al. (Citation2016). These studies incorporate broad themes such as adherence to fundamental values and principles at work, ensuring adequate workload and manageable working hours, promoting productive and fulfilling work environments, providing meaningful remuneration and opportunities for advancement, and emphasising health and safety along with social protection.

While the importance of decent work is well-established in literature, with extensive discussion on its psychological and sociological dimensions, there is an ongoing need for a more comprehensive understanding of how the value of work, as underpinned by tenets of decent work, intersects with the psychology of working theory. According to Blustein et al. (Citation2016), the elements of decent work agenda broadly represent the political and economic consensus within ILO while the social justice and psychological aspects of work have been overlooked. In essence, this restricts, ‘how decent work is understood and implemented’ (Blustein et al. Citation2022, 293) in terms of personal significance and value of work for individuals (Baranik et al. Citation2022; Pratt and Ashforth Citation2003). This implies that the value of work, which individuals desire should be clearly understood in the conceptualisation of decent work (Baranik et al. Citation2022). This is particularly pertinent when considering the value of doctors’ work in the context of public sector hospitals in Pakistan, where they face unique challenges such as lack of facilities, and other problems in their healthcare system (Arshad et al. Citation2016; Khalid and Ali Citation2020). Referring to the values aspect of decent work, and building on the concepts of psychology of working theory (Duffy et al. Citation2016), the following section presents a detailed account on the need for value framework of decent work considering the unique challenges and opportunities in context of public sector doctors.

The need for a value framework for decent work

According to Duffy et al. (Citation2016), psychology of working theory explains ‘important elements in the process of securing decent work – conceptualised and defined below – and describe how performing decent work leads to need satisfaction, work fulfillment, and wellbeing’ (p.128). The psychology of working theory offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the role of work in human life, particularly conceptualising ‘decent work’ as a pivotal mediator. This theory, as outlined by Autin and Duffy (Citation2019) and Duffy et al. (Citation2016), suggests that decent work is influenced by a blend of psychological and sociological factors. These factors together shape an individual’s work experience and lead to a range of outcomes. Firstly, the theory highlights the significance of work in meeting basic survival needs, which is fundamental for any individual (Blustein et al. Citation2018). Beyond this, it highlights how work fosters social connections, linking individuals to a broader community and providing a sense of belonging. This aspect is particularly crucial in the context of doctors working in public hospitals, where the nature of their work often necessitates intense collaboration and communication with colleagues and patients.

Moreover, the theory addresses the role of work in facilitating self-determination (Gagné et al. Citation2022). For doctors, this can mean autonomy in making decisions that impact patient care, thereby enhancing their professional satisfaction (Martela et al. Citation2018). Achieving work fulfilment, another key outcome proposed by the theory (Blustein et al. Citation2018), is especially relevant in the health sector. For many doctors, the ability to make a difference in people’s lives and contribute to public health is a significant source of job satisfaction and fulfilment. Lastly, the theory suggests that decent work to promotes overall wellbeing and quality of care (Ferraro et al. Citation2020). For doctors in public hospitals, where the work environment can be challenging and stressful, the presence of decent work conditions is essential for maintaining their psychological and emotional health.

Furthermore, the psychology of working framework acknowledges the importance of integrating individual psychological components, such as personal goals, meaningfulness, and resilience, with sociological variables like workplace culture, societal factors, and economic conditions (Autin et al. Citation2019; Duffy et al. Citation2016). This integration is vital in understanding the unique experiences of doctors in public hospitals, as it reflects how their personal aspirations and challenges are interwoven with the broader social and economic context of their work. In summary, the psychology of working theory provides a multi-dimensional perspective on the importance of decent work, particularly in complex and demanding fields like the health sector. It recognises the intricate interplay between individual psychology and broader sociological factors in shaping work experiences and outcomes, especially in settings like public hospitals where doctors face unique challenges and opportunities.

While the psychology of working theory provides valuable insights into the psychological and sociological factors influencing decent work, its scope remains vague in understanding the intrinsic value of work, as determined by individual subjective experiences. This aspect is pivotal since the intrinsic value of work is often intertwined with personal significance, profoundly affecting one’s personal development and sense of job fulfilment, as Arendt et al. (Citation2018) has noted. Gesthuizen et al. (Citation2019) found that individuals with a strong sense of work fulfilment are more inclined to remain in their roles, regardless of other extrinsic factors. This implies that the extrinsic values associated with decent work cannot fully substitute the intrinsic values inherent in the work itself, as argued by Hauff and Kirchner (Citation2015). Consequently, understanding the role of individual subjective experiences becomes essential in comprehending occupation-specific decent work, which is influenced by a myriad of contextual factors.

The realisation that not all aspects of decent work are consistently present, due to various psychological and sociological factors at individual, organisational, professional, and societal levels, further emphasises the importance of focusing on the intrinsic value of work through individual subjective experiences (Haller et al. Citation2023). This holds particular relevance in the healthcare sector because a persistent sense of professional fulfilment serves as a continuous motivational force, influencing physicians’ daily work, career choices, and the broader evolution of healthcare (Lindgren et al. Citation2013).

Given these complexities, there is a pressing need to find answers to ‘How does the value of work intersect with the concept of decent work?’ and ‘How are the value of work and the contextual factors influencing this intersect manifested among public sector doctors in Pakistan?’ Accordingly, the responses based on individual experiences will facilitate in determining the value of work, set against the backdrop of decent work’s psychological and sociological aspects. This emphasis on the critical role of contextual factors, grounded in the psychology of working theory, will facilitate a deeper understanding of the multitude of psychological, sociological elements that shape the value of work and are essential for attaining decent work in the healthcare settings. Lastly, different factors in the context of public sector doctors will also help identify challenges and barriers that potentially devalue work for doctors.

Methodology

The aim of this research is to understand the value of the work of Pakistani public sector doctors during COVID-19 pandemic through their subjective experiences and to develop a framework that aligns with the concepts of decent work. Based on the conceptualisation of psychology of working theory (Duffy et al. Citation2016) and elements of subjective experiences in determining decent work, some key questions were asked from the participants. The questions included, ‘What are the factors that add value to the work of Pakistani public sector doctors in the context of COVID-19 pandemic?’, ‘What are the factors that hinder the work of Pakistani public sector doctors in the context of COVID-19 pandemic?’ These questions were further discussed through sub-questions from the participants to obtain detailed overview and perspectives. An in-depth exploratory qualitative study was designed, and semi-structured interviews were conducted to obtain the lived experiences of doctors in the tertiary care public sector hospitals located in Islamabad, the capital territory of Pakistan in August-Sept 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. An exploratory approach, using semi-structured interviews as in this study, allows for the generation of rich perspectives related to the lived experiences of participants (Adams Citation2015; Magaldi and Berler Citation2018; Rendle et al. Citation2019). The lived experiences of doctors were important to understand the factors that were influencing their experiences related to the value of their work, and to identify the elements of decent work for doctors in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals.

Non-probability purposive sampling was employed to recruit doctors from four different tertiary care public sector hospitals in Islamabad, Pakistan that were engaged in the diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of COVID-19 patients. The tertiary care hospitals in Islamabad were chosen for this study because they have relatively advanced infrastructure and draw a wide array of healthcare professionals from multiple regions of Pakistan. This makes them a fitting microcosm of the country’s diverse sociocultural makeup (Arshad et al. Citation2016; Hafeez et al. Citation2023). These medical centres cater to patients from both rural and urban areas across Pakistan, serving as hubs for diagnosis, treatment, and recovery (National Health Vision Pakistan Citation2016). Given their critical role in handling the healthcare challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, these public sector tertiary care hospitals were particularly relevant for sample selection. A purposive approach suits in-depth qualitative exploratory studies such as this one and helps to obtain rich data relevant to the research aims (Ames et al. Citation2019; Palinkas et al. Citation2015).

The criteria for recruitment included the condition of experience of work during the COVID-19 era, having a regular job in a tertiary care public sector hospital, and the ability to communicate in English. 40 doctors were contacted initially and invited to participate in the study. 34 doctors provided consent for participation. All the potential participants were provided with a detailed information letter about the aims, procedure, and possible outcomes of the study. They were assured about the confidentiality of their identity and the use of information solely by the researcher.

Face to face semi-structured interviews were conducted from the participants using the interview guide technique to facilitate the process and to focus the important points (Chenail Citation2011; McGrath et al. Citation2019). presents the list of the interview participants and their details. Participants provided their opinions and perspectives based on their lived experiences of work in the public sector hospitals and specifically in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Each interview lasted for 20 to 30 minutes and there was a sufficient discussion in each of the interview to cover the key and sub-questions. All the interviews were audio recorded with the consent of participants and notes were taken to make sure that all verbal and non-verbal cues are included in the analysis of the data. The data was collected until saturation had been reached, in line with the recommendations of Guest et al. (Citation2006) and Moser and Korstjens (Citation2018) and the concept of Saunders et al.’s (Citation2018) informational redundancy. The saturation point was determined when no new information and reflection could be noted in the data, and it was decided not to conduct further interviews after the 27th participant.

Table 1. Details of the interview participants.

The authors transcribed the obtained data themselves for a better understanding of the responses and to minimise chances of errors in the data analysis. The data was stored, sorted, and coded in QSR NVivo 12. As the process of analysis was initiated during the interviews, it helped to compare the responses of the participant to the concept of decent work and different models mentioned earlier. This helped to ask sub-questions from other participants for a comprehensive view of the value of work for doctors associated decent work. The process of analysis included a series of steps adopted from the recommendations of Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008), and Neuman (Citation2014). It began with an open or line by line coding of the interview data. For example, a statement in response to a question asked to identify factors that add value to doctors’ work was ‘my professional learning through practice gives me a sense of value, like it makes my work effective.’ Another statement was ‘this is a very interesting thing that you are a part of learning curve, and the learning curve belongs to you and you other colleagues’. These and other similar statements were initially coded as ‘learning process’. With the same pattern other statements such as, ‘When I was going through the bad part of my career, when I was not the part of this training, I was pessimistic, sometimes disappointed and there was lack of motivation. Now, I am getting excellence and I am where I wanted to be’, was coded as ‘professional training’. The codes obtained were matched by looking back into the pieces of data to identify the emerging ideas as what is being said by the participants and how that corresponds to the questions asked and to the research questions. This process of coding was further strengthened by merging the common concepts and using an abductive approach of their theoretical comparison with the existing literature on the psychology of working theory and decent work. Accordingly, the code of professional training was merged with the code of learning process and other closely related codes and named ‘professional learning and development’. This theme was considered as one of the occupation-specific values in the backdrop of decent work for doctors.

The process of iteration between the collected data and the existing literature in the abductive approach allows the researcher to relate the existing literature themes to the data themes (Thompson Citation2022; Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012). The process of constant comparison of data and the literature helped in deriving main themes that aligned with research questions, ‘How does the value of work intersect with the concept of decent work?’ and ‘How does the value of work and related contextual factors manifest among public sector doctors in Pakistan?’ The main themes explained the value of doctors’ work and the elements that are important for their decent work in the public sector hospitals of Pakistan.

Findings and discussion

The data was analysed to explore doctors’ experiences regarding the value of their work and the elements required for decent work in their context. Since the doctors who participated in the study were the frontliners against COVID-19, they expressed their opinion about the value of their work in the broader context of the pandemic. The broader context of COVID-19 pandemic was linked to the role of the healthcare system in Pakistan, different social and societal factors, professional and individual psychological factors, and factors at the public sector hospitals level. Eight main themes emerged from their discussion on the two research questions and the analysis of data themes in the light of existing literature on the concepts of decent work. presents illustrative quotes for each of the main themes derived from the data analysis.

Table 2. Data themes and illustration quotes.

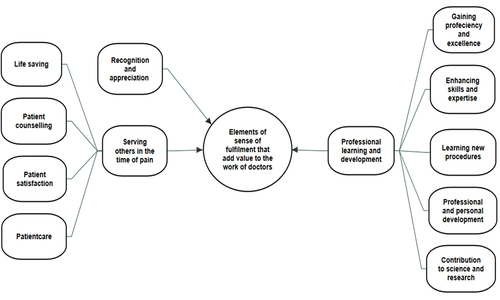

The participants expressed that different societal, professional, organisational, and individual factors, influenced their value of work during COVID-19 pandemic. Participant description of the supporting factors and the challenges helped in understanding the value of the work of doctors in the public sector hospitals of Pakistan and the elements that are necessary for their decent work. depicts the conceptual map of themes based on the analysis of the data.

Serving others

The first theme that emerged from the data was the value of work participants derived from serving others as depicted in . For instance, as expressed by most of the participants, doctors consider their work as a source of helping others and it gives them a sense of happiness and motivation.

‘Being in a country like this, first my satisfaction and happiness would be serving your people and society’ (Participant 9: Medical Officer Emergency)

‘I have been through the process; we are full of energy at that time. We face risks and we want to serve the society’ (Participant 5: Medical Officer Infectious Diseases)

Participants expressed that when they play a crucial role in alleviating others’ suffering during times of distress, they experience a profound sense of value, recognition, and fulfilment. This sentiment is rooted in their direct involvement in patient care, counselling, ensuring patient satisfaction, and the critical role they play in saving lives, which are seen as pivotal sources of satisfaction, motivation, meaning, and fulfilment in their professional lives. The importance of these elements aligns with research by Lindgren et al. (Citation2013) and Restauri et al. (Citation2019), which highlight the experience of fulfilment and meaningfulness as integral to the intrinsic value of work, especially in medical professions.

In the context of Pakistani doctors, as examined by Afshan et al. (Citation2022) and Buowari (Citation2022), this sense of fulfilment and meaning is not just a personal benefit. It has a broader impact, significantly enhancing work engagement and motivation, while concurrently reducing burnout. The psychological impact of such fulfilment derived, is central to understanding the intrinsic value of work for doctors within the framework of decent work. This intrinsic value, deeply interwoven with the doctors’ sense of professional identity, offers a unique perspective on the psychology of working theory. It highlights how meaning in work transcends mere economic necessity. This aspect is particularly relevant in the healthcare sector, where the act of healing and saving lives provides a profound sense of purpose and self-fulfilment, which, according to self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000), is essential for intrinsic motivation. Therefore, in the framework of decent work, the intrinsic value of work for doctors extends beyond conventional metrics of job satisfaction and encompasses a deeper, more existential dimension of professional fulfilment and societal contribution.

Recognition and appreciation

Another theme which was considered as an element that contribute to their sense of fulfilment and add to the value of doctors’ work was recognition and appreciation. Different examples from participants’ statements illustrate how recognition and appreciation add value to the work of doctors or, on the other hand, undervalue it.

‘Yes, for me, it would be if a patient that I treat in the end of the treatment, he prays for me, and he tells me that doctor, you have treated me really well and I’m feeling better. I think so nothing can top that situation, that feeling when I get some patients thanking me for good work, good service. I think so that is the best thing I can find in this job’. (Participant 2: Consultant Critical Care)

Many participants expressed that when they feel that patients are satisfied with their work and that when their efforts are recognised or appreciated, they feel valued and accomplished. On the other hand, the absence of recognition or appreciation made them feel less valued.

‘If I have a bad day and after a daylong of hard work I do not get appreciation from my seniors, it affects [our] mental health and it affects me’. (Participant 16: Registrar Gastroenterology)

According to Laaser and Karlsson (Citation2021) and Winchenbach et al. (Citation2019), the intersubjective experiences of recognition and appreciation are fundamentally linked to social dignity, self-worth, and respect within the professional sphere. In the specific case of doctors, especially those in the public sector of Pakistan, fostering an environment that enhances self-worth and respect is not just beneficial but essential. Such an environment is likely to augment their sense of fulfilment and the intrinsic value they derive from their work.

The importance of recognition and appreciation cannot be overstated, especially when considering the drivers of job satisfaction and engagement. Lindgren et al. (Citation2013) highlights the significant role these factors play in cultivating a sense of professional fulfilment and work engagement. In the framework of decent work for public sector doctors in Pakistan, the elements of recognition and appreciation emerge as critical components. They act as catalysts for motivation and engagement, leading to improved job performance and personal satisfaction.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of doctors has been more crucial than ever, with them being on the front lines of a global health crisis. Their tireless efforts and sacrifices have been central to managing the pandemic’s challenges. This recognition should be embedded in the organisational culture and policies, reflecting in tangible actions like adequate compensation, supportive work environments, and opportunities for professional growth. These are not just elements of a supportive work environment but are integral to the concept of decent work, particularly in the challenging times of a global pandemic. Such initiatives will show genuine appreciation and contribute to their overall sense of dignity and self-worth.

Professional learning and development

The third theme that emerged from the analysis of data is the professional learning and development adds value to doctors’ work. Participants expressed that their work at hospitals is a source of learning and professional and personal development as depicted in . As expressed by most of the participants, their work helps them in enhancing their skills and expertise, gaining proficiency and excellence and contribution to medical research in their respective fields.

‘Learning, skills and experience are important to become a successful doctor’. (Participant 6: Senior Medical Officer Infectious Diseases)

‘Although, it is a kind of very tough job, attending 24 hours calls, doing emergencies and many things but we are learning’. (Participant 24: Medical Officer Nephrology)

The recognition of continuous professional learning and development emerges as a cornerstone for the value of work for doctors, emphasised by the necessity for updated knowledge and expertise in daily work, career decisions, and clinical practices, as highlighted by Lindgren et al. (Citation2013). This was especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period that exemplified the urgent need for doctors to rapidly acquire new knowledge and skills to effectively manage the crisis. Such a dynamic environment highlights the significance of purpose-driven learning and development, which not only equips medical professionals with the necessary tools to adapt to evolving challenges but also fosters a heightened sense of self-efficacy, commitment, and persistence. These attributes are crucial for doctors who often aim to transcend beyond mere economic objectives in their service delivery, as discussed by Kosine et al. (Citation2008).

This concept of purpose-driven professional learning and development embodies more than the acquisition of knowledge; it encapsulates the very essence of fulfilling work in the medical profession. Doctors, through their ongoing education and skill enhancement, come to recognise and embrace the rewarding nature of their work. This process of continuous learning aligns with their intrinsic motivation and dedication to healthcare excellence. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the potential implications of any impediments to this professional growth. As Ferraro et al. (Citation2018) suggest, obstacles hindering professional development can significantly diminish a doctor’s sense of fulfilment, thereby contravening the principle of ‘opportunities’ within the broader framework of decent work.

Therefore, the provision and support for continuous learning and development are not merely beneficial but essential for maintaining the high standards of healthcare practice. It is a critical factor in ensuring that doctors remain at the forefront of medical advances, thereby safeguarding both their professional satisfaction and the efficacy of the healthcare system at large. This focus on learning and development aligns with the broader principles of decent work, reinforcing the idea that such opportunities are fundamental to the sustainability and effectiveness of healthcare services.

Hindrances to decent work

Apart from the elements of sense of fulfilment that were considered essential for the value that doctors draw through their work, some other elements linked to different contextual factors were considered as hindrances for doctors’ decent work. The elements that were highlighted in the data included: a) poor healthcare system; b) issues from patients and public; c) poor work environment; d) lack of essential facilities; and d) physical and mental health challenges.

The participants’ description of a range of element that were considered as hindrances for externally decent work were influencing the value of their work. As evident from the participants data, the healthcare system of Pakistan has many deficiencies and flaws which create different hindrances in their work, and they feel undervalued. The burden of patients in public sector hospitals, lack of doctors and healthcare staff, lack of hospitals and healthcare infrastructure for public, and political interference, create different challenges for the work of doctors such as long work hours, increased workload, burnout, fatigue, and stress.

‘It is our bad luck or system flaw that we have courtesy centres in our hospitals. We have to provide special care to politicians, bureaucrats, they are given special attention’. (Participant 1: Director Immunisation Centre)

‘Due to a big flow of patients, we cannot do a proper examination of each and every patient. For a good examination 25–30 mins are required, which is literally impossible here’. (Participant 19: Head of the Psychiatry Department)

Participants were vocal about the patients’ and public lack of awareness about health issues, which make them feel that their work is undervalued. Furthermore, some participant complained about the misbehave of patients or their attendants with doctors, which make them feel less valued. Additional to this, the lack of essential facilities such as lack of basic health facilities in different public sector hospitals, lack of updated or enough medical equipment, lack of personal protection equipment for doctors, and poor work environment especially during the initial days of COVID-19 pandemic were perceived as critical challenges for the value of their work.

‘If you are not provided with adequate facilities and you are exposed to health and life risks, especially, in this pandemic, it does affect your work and output’. (Participant 14: Medical Officer Pulmonology)

‘I think I do not have many positive words when it comes to the environment of the Pakistan’s public sector. It is challenging’. (Participant 21: Medical Officer Urology)

The risks inherent in the work of doctors, as highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, extend to severe consequences including the mortality of doctors themselves. These challenges, situated within the broader context of the pandemic, significantly impede their sense of fulfilment, meaning, and the effective execution of professional healthcare practices.

The value framework

A critical aspect to consider is the interconnectedness of these elements, which collectively amplify their impact on the decent work environment for doctors. These elements intersect at various layers of societal, professional, and organisational dimensions, as depicted in of the value framework of decent work. For instance, public health awareness, hospital policies, and the provision of resources and facilities are intricately linked to the healthcare system. A substandard healthcare system can adversely affect hospital policies, patient management, and the overall hospital environment. This cascading effect, compounded by poor working conditions, challenges from patients and the public, and a lack of essential facilities – all stemming from broader healthcare and hospital policy issues – create a myriad of physical and mental health challenges for doctors. These interconnected elements, influenced by societal, healthcare system, professional, and organisational factors, are effectively elucidated through the comprehensive framework and principles of decent work. While individual psychological factors shape doctors’ sense of fulfilment and add value to their work, different societal, healthcare system, professional, and organisational factors mould the elements of their externally decent work.

The insufficiency of conditions essential for decent work fundamentally undervalues the work for doctors. The hindering elements, influenced by diverse contextual factors, contravene the basic tenets of decent work. They particularly contradict the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) principles, where fundamental values and standards for a safe working environment and social protection are breached. Ferraro et al. (Citation2020) highlights that fundamental principles and values at work, alongside opportunities, are significant predictors of work engagement, whereas conditions like prolonged working hours and heightened workload precipitate burnout among physicians. Moreover, beyond the absence of fundamental values aligned with the principles of decent work, various challenges specific to doctors’ roles, such as risks of infections and patient mortality, exert a profound impact on physicians’ emotional wellbeing, leading to stress, insomnia, anxiety, and depression (Buowari Citation2022). Research by Afshan et al. (Citation2022) and Ali et al. (Citation2021) also highlights that, particularly in Pakistan, public sector doctors face multiple physical and psychological challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Accordingly, we offer the value framework of decent work as in , determining the value of work, set against the backdrop of decent work’s psychological and sociological aspects. This framework is a synthesis of the psychology of working theory and the concept of decent work. It facilitates in achieving several objectives in the context of public sector doctors: a) identifying factors that influence individual subjective experiences and thereby affect the intrinsic value of work; b) exploring the factors that impact decent work and their effect on work’s value; c) pinpointing occupation-specific elements that shape the subjective experiences of fulfilment; d) examining occupation-specific elements that influence decent work; and e) understanding how both subjective experiences and elements of externally decent work can augment or diminish the overall value of work.

The medical profession, by its very nature, is rife with stressors and challenges, as documented in studies by Ali et al. (Citation2019) and Arnetz (Citation2001). This is particularly true within healthcare systems and hospitals, and the situation is even more pronounced in Pakistan’s public sector. Here, doctors often face a significant devaluation of their work, with prevalent issues that starkly contrast with the ideals of decent work as defined by the International Labour Organisation. Despite these suboptimal conditions, it is important to recognise that doctors often find intrinsic value in their work. This internal satisfaction is not merely about compensation or working conditions; it stems from a deeper sense of fulfilment, recognition, and appreciation. It is also closely tied to opportunities for professional growth and development. This intrinsic value is a crucial component in understanding and conceptualising decent work within the healthcare context.

The findings of this study corroborate the argument that doctors with a heightened sense of work fulfilment are likely to remain committed to their roles, even when there are limited extrinsic elements. This suggests that the external factors associated with decent work cannot fully compensate for the intrinsic value integral to the work itself, as articulated by Hauff and Kirchner (Citation2015). However, the existence of intrinsic satisfaction should not be misconstrued as a justification for the lack of decent work conditions. Relying solely on the intrinsic motivations of doctors is insufficient and unsustainable. It is imperative that hospitals and the broader healthcare system take proactive steps to improve conditions, aligning them with the principles of decent work. This includes ensuring adequate remuneration, manageable workloads, safe working environments, and opportunities for career advancement. By doing so, not only will the wellbeing of doctors be safeguarded, but it will also likely lead to improved patient care and overall efficiency within the public healthcare system. In conclusion, while the intrinsic value of medical work is undeniably important, it must be complemented with concerted efforts to provide decent work conditions in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals.

Contribution to research and implications for practice

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study represents a pioneering exploration into how the work of doctors in Pakistan’s public sector is valued or undervalued, and how this evaluation aligns or contradicts with the concept of decent work. It presents a nuanced framework that examines the interplay of various contextual and occupation-specific factors, analysing the value of doctors’ work within the broader ambit of decent work, as depicted in . The study sheds light on the impact of societal, healthcare system, professional, and organisational contextual factors, which are intricately connected with the psychological and sociological dimensions of decent work, as outlined in the models by Duffy et al. (Citation2016) and Ferraro et al. (Citation2018).

A key finding is that the subjective experience of a sense of fulfilment emerges as the most significant element enhancing the value of work for doctors in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals. This is intimately linked to the sense of serving others, receiving recognition and appreciation, and engaging in professional learning and development through work. This finding resonates with the conditions of ‘fundamental principles and values of work’, ‘fulfilling and productive work’, and ‘opportunities’, as emphasised in the models of decent work and psychology of working theory. Unlike, considering sense of fulfilment as an outcome of decent work as discussed in Duffy et al.’s (Citation2016) model, this framework regards it as a predictor and a core element of decent work for public sector doctors.

Conversely, this study identifies several factors that diminish the value of work for doctors, including flaws in the healthcare system, patient-related issues, poor work environments, lack of essential facilities, and physical and mental health challenges stemming from various societal, healthcare system, professional, and organisational factors. These detractors are articulated through the elements of decent work, encompassing ‘fundamental values and principles at work’, ‘adequate workload and working time’, ‘productive and fulfilling work’, ‘opportunities’, ‘health and safety’, and ‘social protection’.

In advancing the conceptualisation of decent work, this study highlights that the intrinsic value of work is pivotal in sustaining the persistence and commitment of individuals, even in the limited provision of conditions conducive to externally decent work, as evidenced by the experiences of doctors in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic. While elements vital for externally decent work are important, they cannot fully substitute the intrinsic value of work, which is inherently tied to individual subjective experiences of sense of fulfilment. This intrinsic motivation enabled the doctors to persevere in their duties during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite numerous challenges to achieving externally decent work. However, this should not be considered as a replacement for the provision of other extrinsic elements of decent work.

The study suggests that strategies at both organisational and healthcare system levels are essential to mitigate these challenges and enhance decent work of doctors in Pakistan’s public sector hospitals. The Ministry of National Health Services of Pakistan has a crucial role to play in addressing healthcare system flaws, raising public awareness, improving the work environment in public sector hospitals, and ensuring the availability of essential facilities. These improvements are critical for safeguarding healthcare professionals’ safety and wellbeing, and for fulfilling other conditions of decent work. For example, adherence to safe working conditions, provision of necessary facilities, implementation of policies promoting a conducive work environment, and enhancement of public healthcare policies could significantly reduce stressors and challenges faced by doctors, thereby enabling them to provide quality care. Such improvements would also facilitate opportunities for doctors to fulfil their motivation to serve, engage in professional learning and development, receive recognition and appreciation for their services, and satisfy their drive for excellence and proficiency.

Limitations and recommendations for future studies

This study is subject to limitations commonly associated with qualitative research including the limitation on generalisability to other contexts. Its focus is narrowly defined, exploring only doctors within tertiary care public sector hospitals in Islamabad, Pakistan. The scope excludes other healthcare professionals working in the similar context and does not include any comparative analysis with the experiences of doctors in the private sector or those operating in different regions. Additionally, the timing of the study, conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, may have inadvertently led to an emphasis on the factors that diminish the value the work for doctors in Pakistani public sector. Despite these limitations, the study advances the understanding of decent work by exploring the value of work and the specific conditions that either enhance or undermine the work of public sector doctors in Pakistan.

For future research it would be beneficial to broaden the scope to include the value of work for healthcare professionals in the private sector, as well as other healthcare workers in varying cultural and socio-economic contexts. An in-depth exploration of resilience and commitment among doctors, particularly in the light of increased workloads and psychological pressures, in addition to their inherent job demands. Such research should aim to identify additional factors that cultivate a sense of fulfilment in doctors, especially in environments where the conditions for decent work are not fully met. This approach could provide a more comprehensive understanding of what sustains healthcare professionals in challenging work environments and contribute to the development of more supportive work structures and policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abid Hussain

Abid Hussain is the Research Associate at Mental Awareness, Respect and Safety (MARS) - an ECU Industry Collaboration Centre for the Mining Sector.. He earned his Doctor of Philosophy from Edith Cowan University, with his thesis examining “The Concept and Role of Meaningful Work in the Context of the Public Healthcare Sector of Pakistan.” His areas of research are meaningful work, health and wellbeing, psychosocial safety, and leadership.

Esme Franken

Esme Franken is the Mental Awareness, Respect and Safety (MARS) Centre Course Coordinator - an ECU Industry Collaboration Centre for the Mining Sector and a Senior Lecturer in the School of Business and Law. Her research has led to productive partnerships in countries including Brazil, the UK, Germany, and New Zealand. Esme currently serves as a board member for the Australia and New Zealand Academy of Management, and is a member of the British Academy of Management.

Tim Bentley

Tim Bentley is the Mining Work Health and Safety Professorial Chair and Director of the Mental Awareness, Respect and Safety (MARS) Centre, which is an ECU Industry Collaboration Centre for the Mining Sector. He is the former Director of the New Zealand Work Research Institute and Auckland University of Technology’s Future of Work Program; Director of Massey University’s Healthy Work Group; and Director of the Centre for Human Factors and Ergonomics at Forest Research. Tim’s research primarily focuses on psychosocial risk, workplace bullying, and new ways of working, and he is passionate about creating healthy work for the advancement of organisational and employee wellbeing.

Uma Jogulu

Uma Jogulu is a Senior Lecturer at Edith Cowan University, Australia. Prior to this appointment, she was a senior lecture at Monash University and Deakin University. Uma has published in leading refereed journals and engages in the scholarship with great passion. Uma also inductively applies her conceptual understanding as a way of guiding data analysis and interpretation. Her research focuses on careers and human resource management, migrant and self-initiated expatriate, diversity and workplace iclusion and mixed methods.

References

- Adams, W. 2015. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119171386.ch19.

- Afshan, G., F. Ahmed, N. Anwer, S. Shahid, and M. A. Khuhro. 2022. “COVID-19 Stress and Wellbeing: A Phenomenological Qualitative Study of Pakistani Medical Doctors.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:920192. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.920192.

- Ali, I., S. Sadique, and S. Ali. 2021. “Doctors Dealing with COVID-19 in Pakistan: Experiences, Perceptions, Fear, and Responsibility.” Frontiers in Public Health 9:9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.647543.

- Ali, F. S., B. F. Zuberi, T. Rasheed, and M. A. Shaikh. 2019. “Why Doctors Are Not Satisfied with Their Job-Current Status in Tertiary Care Hospitals.” Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 35 (1): 205–210. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.35.1.72.

- Amanullah, S., and Ramesh Shankar, R. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Physician Burnout Globally: A Review.“Healthcare (Basel) 8 (4): 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040421.

- Ames, H., C. Glenton, and S. Lewin. 2019. “Purposive Sampling in a Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: A Worked Example from a Synthesis on Parental Perceptions of Vaccination Communication.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 19 (1): 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0665-4.

- Arendt, H., M. Canovan, and D.-T. A.-T.-T. Allen. 2018. The Human Condition. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Arnetz, B. B. 2001. “Psychosocial Challenges Facing Physicians of Today.” Social Science & Medicine 52 (2): 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00220-3.

- Arshad, S., J. Iqbal, H. Waris, M. Ismail, and A. Naseer. 2016. “Health Care System in Pakistan: A Review.” Research in Pharmacy and Health Sciences 2 (3): 211–216. https://doi.org/10.32463/rphs.2016.v02i03.41.

- Atif, M., and I. Malik. 2020. “Why Is Pakistan Vulnerable to COVID-19 Associated Morbidity and Mortality? A Scoping Review.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 35 (5): 1041–1054. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3016.

- Autin, K. L., and R. D. Duffy 2019. The Psychology of Working: Framework and Theory BT - International Handbook of Career Guidance. edited by, J. A. Athanasou & H. N. Perera. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25153-6_8.

- Baranik, L. E., N. Wright, and R. W. Smith. 2022. “Desired and Obtained Work Values Across 37 Countries: A Psychology of Working Theory Perspective.” International Journal of Manpower 43 (6): 1338–1351. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-12-2020-0555.

- Blustein, D. L., M. E. Kenny, A. Di Fabio, and J. Guichard. 2018. “Expanding the Impact of the Psychology of Working: Engaging Psychology in the Struggle for Decent Work and Human Rights.” Journal of Career Assessment 27 (1): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072718774002.

- Blustein, D. L., E. I. Lysova, and R. D. Duffy. 2022. “Understanding Decent Work and Meaningful Work.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 10 (1): 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031921-024847.

- Blustein, D. L., C. Olle, A. Connors-Kellgren, and A. J. Diamonti. 2016. “Decent Work: A Psychological Perspective.” Frontiers in Psychology 7:407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00407.

- Buowari, D. Y. 2022. “The Well-Being of Doctors During the COVID-19 pandemic.” In Health Promotion, edited by M. Mollaoğlu, Ch. 12. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.105609.

- Chenail, R. 2011. “Interviewing the Investigator: Strategies for Addressing Instrumentation and Researcher Bias Concerns in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Report 16:255–262. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2011.1051.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd ed.): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153.

- Dawn. 2022. Contractual Doctors in KP Threaten to Boycott COVID-19 Duty. February 8. https://www.dawn.com/news/1673946.

- Denis, J. L., and N. van Gestel. 2016. “Medical Doctors in Healthcare Leadership: Theoretical and Practical Challenges.” BMC Health Services Research 16 (2): 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1392-8.

- Duffy, R. D., B. A. Allan, J. W. England, D. L. Blustein, K. L. Autin, R. P. Douglass, J. Ferreira, and E. J. R. Santos. 2017. “The Development and Initial Validation of the Decent Work Scale.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 64 (2): 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000191.

- Duffy, R., D. Blustein, M. Diemer, and K. Autin. 2016. “The Psychology of Working Theory.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 63 (2): 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000140.

- Elliott, R., L. Crowe, B. Abbenbroek, S. Grattan, and N. E. Hammond. 2022. “Critical Care Health professionals’ Self-Reported Needs for Wellbeing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Thematic Analysis of Survey Responses.” Australian Critical Care: Official Journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses 35 (1): 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2021.08.007.

- Ferraro, T., N. R. dos Santos, J. M. Moreira, and L. Pais. 2020. “Decent Work, Work Motivation, Work Engagement and Burnout in Physicians.” International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 5 (1): 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-019-00024-5.

- Ferraro, T., L. Pais, N. Rebelo Dos Santos, and J. M. Moreira. 2018. “The Decent Work Questionnaire: Development and Validation in Two Samples of Knowledge Workers.” International Labour Review 157 (2): 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12039.

- Gagné, M., S. K. Parker, M. A. Griffin, P. D. Dunlop, C. Knight, F. E. Klonek, and X. Parent-Rocheleau. 2022. “Understanding and Shaping the Future of Work with Self-Determination Theory.” Nature Reviews Psychology 1 (7): 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00056-w.

- Gesthuizen, M., D. Kovarek, and C. Rapp. 2019. “Extrinsic and Intrinsic Work Values: Findings on Equivalence in Different Cultural Contexts.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 682 (1): 60–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716219829016.

- The Guardian. 2020. “Pakistan Doctors Beaten by Police As the Despair of ‘Untreatable’ Pandemic. Lack of Equipment, Dysfunctional Government and Conflicting Messages Are Impeding country’s Efforts Against Virus.” April 9. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/09/pakistan-doctors-beaten-police-despair-untreatable-pandemic.

- Guest, G., A. E. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews Are Enough?” Field Methods 18:59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Hafeez, A., W. J. Dangel, S. M. Ostroff, A. G. Kiani, S. D. Glenn, J. Abbas, M. S. Afzal, et al. 2023. “The State of Health in Pakistan and Its Provinces and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.” The Lancet Global Health 11 (2): e229–e243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00497-1.

- Hakim, M., S. Afaq, F. A. Khattak, M. Jawad, S. Ul Islam, M. Ayub Rose, M. Shakeel Khan, and Z. U. Haq. 2021. “Perceptions of Covid–19-related Risks and Deaths Among Health Care Professionals During COVID-19 Pandemic in Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study.” INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, & Financing 58:00469580211067475. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580211067475.

- Haller, M., B. Klösch, and M. Hadler. 2023. “The Centrality of Work: A Comparative Analysis of Work Commitment and Work Orientation in Present-Day Societies.” Sage Open 13 (3): 21582440231192110. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231192114.

- Hauff, S., and S. Kirchner. 2015. “Identifying Work Value Patterns: Cross-National Comparison and Historical Dynamics.” International Journal of Manpower 36 (2): 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-05-2013-0101.

- ILO. 2022. Decent Work Indicators. https://www.ilo.org/integration/themes/mdw/WCMS_189392/lang–en/index.htm.

- International Labour Organization. 2015. Decent Work Country Diagnostics: Technical Guidelines to Draft the Diagnostic Report. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_mas/—program/documents/genericdocument/wcms_561044.pdf.

- Johnson, S. B., and F. Butcher. 2021. “Doctors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Are Their Duties and What Is Owed to Them?” Journal of Medical Ethics 47 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106266.

- Khalid, A., and S. Ali. 2020. “COVID-19 and Its Challenges for the Healthcare System in Pakistan.” Asian Bioethics Review 12 (4): 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-020-00139-x.

- Khan, M. I. 2020. “Coronavirus: Why Pakistan’s Doctors Are so Angry.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52243901.

- Kosine, N. R., M. F. Steger, and S. Duncan. 2008. “Purpose-Centered Career Development: A Strengths-Based Approach to Finding Meaning and Purpose in Careers.” Professional School Counseling 12 (2): 133–136. https://doi.org/10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.133.

- Krumm, S., A. Grube, and G. Hertel. 2013. “The Munster Work Value Measure.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 28 (5): 532–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2011-0023.

- Laaser, K., and J. C. Karlsson. 2021. “Towards a Sociology of Meaningful Work.” Work, Employment and Society 36 (5): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211055998.

- Lindgren, Å., F. Bååthe, and L. Dellve. 2013. “Why Risk Professional Fulfilment: A Grounded Theory of Physician Engagement in Healthcare Development.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 28 (2): e138–e157. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2142.

- Magaldi, D., and M. Berler. 2018. “Semi-Structured Interviews.” In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, edited by V. Zeigler-Hill and T. K. Shackelford, 1–6. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_857-1.

- Martela, F., R. M. Ryan, and M. F. Steger. 2018. “Meaningfulness as Satisfaction of Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness, and Beneficence: Comparing the Four Satisfactions and Positive Affect as Predictors of Meaning in Life.” Journal of Happiness Studies 19 (5): 1261–1282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9869-7.

- McGrath, C., P. J. Palmgren, and M. Liljedahl. 2019. “Twelve Tips for Conducting Qualitative Research Interviews.” Medical Teacher 41 (9): 1002–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149.

- Moser, A., and I. Korstjens. 2018. “Series: Practical Guidance to Qualitative Research. Part 3: Sampling, Data Collection and Analysis.” European Journal of General Practice 24 (1): 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091.

- National Health Vision Pakistan. 2016. National Health Vision Pakistan 2016–2025 for Coordinated Priority Actions to Address Challenges of Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Health and Nutrition, UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/media/1276/file/National%20Vision%202016-2025.pdf.

- Neuman, W. L. 2014. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 7th ed. UK: Pearson Education Limited.

- Osborne, H. 1931. “Definition of Value.“ Philosophy 6 (24): 433–445. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031819100032381.

- Palinkas, L. A., S. M. Horwitz, C. A. Green, J. P. Wisdom, N. Duan, and K. Hoagwood. 2015. “Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42 (5): 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.

- Pandey, S. K., and V. Sharma. 2020. “A Tribute to Frontline Corona Warriors–Doctors Who Sacrificed Their Life While Saving Patients During the Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic.” Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 68 (5): 939–942. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_754_20.

- Pratt, M., and B. Ashforth. 2003. “Fostering Meaningfulness in Working and at Work.” In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline, edited by K. Cameron, J. Dutton, and R. Quinn, 309–327. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303052224_Fostering_meaningfulness_in_working_and_at_work.

- Rana, W., S. Mukhtar, and S. Mukhtar. 2020. “Mental Health of Medical Workers in Pakistan During the Pandemic COVID-19 Outbreak.” Asian Journal of Psychiatry 51:102080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102080.

- Razu, S. R., T. Yasmin, T. B. Arif, M. S. Islam, S. M. S. Islam, H. A. Gesesew, and P. Ward. 2021. “Challenges Faced by Healthcare Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Inquiry from Bangladesh.” Frontiers in Public Health 9:647315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315.

- Rendle, K. A., C. M. Abramson, S. B. Garrett, M. C. Halley, and D. Dohan. 2019. “Beyond Exploratory: A Tailored Framework for Designing and Assessing Qualitative Health Research.” British Medical Journal Open 9 (8): e030123. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030123.

- Restauri, N., E. Nyberg, and T. Clark. 2019. “Cultivating Meaningful Work in Healthcare: A Paradigm and Practice.” Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology 48 (3): 193–195. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2018.12.002.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Saunders, B., J. Sim, T. Kingstone, S. Baker, J. Waterfield, B. Bartlam, H. Burroughs, and C. Jinks. 2018. “Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization.” Quality & Quantity 52 (4): 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

- Shaukat, N., D. M. Ali, R. Barolia, B. Hisam, S. Hassan, B. Afzal, A. S. Khan, M. Angez, and J. Razzak. 2022. “Documenting Response to COVID-Individual and Systems Successes and Challenges: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study.” BMC Health Services Research 22 (1): 656. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08053-8.

- Shaukat, N., D. M. Ali, and J. Razzak. 2020. “Physical and Mental Health Impacts of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Emergency Medicine 13 (1): 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5.

- Simons, G., and D. S. Baldwin. 2021. “A Critical Review of the Definition of ‘Wellbeing’ for Doctors and Their Patients in a Post COVID-19 Era.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 67 (8): 984–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211032259.

- Somavia, J. 1999. Decent Work for All in a Global Economy: An ILO Perspective. https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/dgo/speeches/somavia/1999/seattle.htm.

- Tallis, R. C. 2006. “Doctors in Society: Medical Professionalism in a Changing World.” Clinical Medicine 6 (1): 7–12. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.6-1-7.

- Thompson, J. 2022. “A Guide to Abductive Thematic Analysis.” The Qualitative Report 27 (5): 1410–1421. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5340.

- Timmermans, S., and I. Tavory. 2012. “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis.” Sociological Theory 30 (3): 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914.

- UN. 2015. Global Sustainable Development Report. 2015, https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/global-sustainable-development-report-2015-edition.html.

- WHO. 2023. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. April 13. https://covid19.who.int/.

- Winchenbach, A., P. Hanna, and G. Miller. 2019. “Rethinking Decent Work: The Value of Dignity in Tourism Employment.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27 (7): 1026–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1566346.

- Yousafzai, G. 2020. Doctors Strike in Southwest Pakistan in Row Over Coronavirus Protection. https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-pakistan-healthcare-idINKBN21P1IS.