ABSTRACT

This paper analyses women’s voice at the intersection of climate change, work, and industrial relations in Australia. Despite the urgency of climate change and the need for a just transition, research on women’s voice in Australia’s climate change policy is scarce. This study conducts a content analysis of 17 policy documents from 2011–2022 related to women and climate change, produced by the National Women’s Alliances. These documents include qualitative interviews with individuals and communities affected by climate change exacerbated natural disasters. The study identifies four main themes of women’s voice: family and community care (unpaid work), employment (paid work), recognition of women’s roles and resilience, and natural disaster response and recovery. Findings highlight a focus on reactive responses to natural disasters rather than proactive measures addressing gendered impacts of climate mitigation and adaptation for a just transition. The results underscore the need for a nuanced understanding of women’s voice in shaping a just transition.

Introduction

The relationship between work, industrial relations and climate change has emerged as a pressing issue in recent years, with an increasing awareness of the implications of climate change on employment (Goods Citation2017). Unions have been actively advocating a just transition to a low-carbon economy to support the rights of workers affected by climate change, and promote sustainable practices in the workplace (Goods Citation2017; Markey and McIvor Citation2019). For some industries, such as energy provision and resource extraction, the negative impacts of climate mitigation are evident, making their vulnerability and viability apparent (Snell Citation2018; Wilgosh et al. Citation2022). For many other industries, the impacts are far less obvious, for example, increasing community vulnerability from climate-related changes will have significant impacts on demand for care and community services sectors (Carr Citation2022; Ravenswood Citation2022). Consequently, a transformation of work is expected across a broader section of the labour market than what is immediately apparent (Denham and Rickards Citation2022; Humphrys et al. Citation2022).

While unions have traditionally focused on better wages and conditions, there is now pressure to directly engage in shaping decisions related to addressing climate change (Douglas and McGhee Citation2021). Arguably, the policy response to climate change requires an interventionist state response to the ‘twin crises’ of the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change (Dean and Rainnie Citation2021). Diversification of stakeholder representation via increased policy intervention may circumvent ‘green collar’ employment growth being dominated by employer associations and market forces that may expose workers to precarious employment conditions and erode social justice objectives of a just transition (Masterman-Smith Citation2010), contributing to reifying existing labour market inequalities. However, as Goods and Ellem (Citation2022) show, employer associations have utilised structural and associational influence, and wield overt and covert political tactics to oppose climate policies.

Simultaneously, links between climate change and work are increasingly recognised, focusing on more inclusivity and equity in the transition to a low-carbon economy (Goods Citation2017). Notably, comprehensive consideration of women’s voices in the context of climate change and employment relations has been lacking across relevant stakeholders. As such, there has been a lack of attention given to the intersection of women’s perspectives and climate change policy.

This study aims to examine the implications of foregrounding women’s voices and perspectives on climate mitigation and adaptation for extending our conceptualisation of just transitions. Due to the nation’s vulnerability to frequently occurring natural disasters on an increasingly nationally significant scale, especially fires, floods and droughts (see National Emergency Management Agency, & Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience Citation2023) Australia becomes a site of interest. Though climate mitigation policy has been the subject of a polarising political discourse that has influenced institutional responses and effectiveness in Australia (see MacNeil Citation2021), concerns over response and recovery from natural disasters have consistently had bipartisan support by successive governments. This support has precipitated a long history of Royal Commissions and Senate inquiries into response, recovery and resilience to natural disasters, recent examples include The Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements (Commonwealth of Australia Royal Commissions Citation2020), established on 20 February 2020 in response to the extreme bushfire season of 2019–20 and Senate Select Committee on Australia’s Disaster Resilience (Parliament of Australia Citation2022) appointed on 30 November 2022 to inquire into ‘Australia’s preparedness, response and recovery workforce models, as well as alternative models to disaster recovery’. This has resulted in a body of policy literature on disaster impacts incorporating a sub-set with a gender perspective, this paper examines the national response and resilience to increasing effects of natural disasters and looks to inform other nations facing increased adaptation requirements. To do this we focus on our central research question: how do women’s experiences of natural disasters inform policy at the intersection of climate adaptation and industrial relations? Findings of this analysis reveal that gendered vulnerabilities entrenched in existing institutional responses to family and community care, employment opportunities and economic security, recognition of women’s roles and resilience, response and recovery to natural disasters argue for conceptualisations of just transitions to further consider the gendered nature of climate mitigation and adaptation.

Integrating women’s voice into just transitions

Within the employment relations literature on climate change, ‘just transition’ is the concept that has arguably received the widest attention (Flanagan and Goods Citation2022). The term historically arose from North American Trade Unions but has come to signify a range of concepts and approaches to climate compatible development (Snell Citation2018). Approaches to just transitions vary widely, from expansive to narrow. Expansive definitions argue the need to situate workers in high-emitting industries in their communities, broadening the scope of those potentially impacted by climate sensitive development. Policy interventions under these formulations include the use of locally sensitive transition and assistance programmes. Alternatively, narrower definitions including Eisenburg (Citation2019) advocate specific focus on supporting workers who depend on high-carbon industries to transition away from them. Given current and historic substantive challenges associated with climate mitigation action on all levels of governance, government and business, both in Australia and globally, these conceptualisations were developed in attempts to resolve job-environment dichotomies towards solutions, including gathering and galvanising public support for transitions (Goods Citation2013). Successive IPCC reports, especially the most recent (IPCC Citation2022), make clear that these programmes of just transition and climate mitigation are far from resolved, and accelerating mitigation while concurrently preparing for and adapting to existent effects of living in a climate changed world is required. Arguably this implies the conditions underpinning conceptualisations of just transitions have radically shifted towards recognising adaptation and a greater variety of workers.

The just transition literature has been primarily informed by climate mitigation specifically, moving from high-emitting industries to low-carbon economies. It follows that the literature addresses transitioning workers, under narrow definitions, and community issues, under more expansive definitions, with male-dominated high-emitting industries having prominence over impacts of transition and climate related policies for women.

Emphasising extractive industries and energy production is warranted with the imperative for transitioning away from fossil fuels, however it is increasingly recognised that many more industries will be impacted by changing environments and conditions, for example hotter weather, and more frequent and extreme weather events (see Humphrys et al. Citation2022). To incorporate likely and existent conditions of a climate changing and changed world, what Carr (Citation2022) refers to as the ‘everyday work of coping with planetary breakdown’ and the ‘tangible work of climate crisis’, requires broadening our understanding of likely impacted industries. This everyday work involves not only repairing and re-building physical infrastructure but also social cohesion, community trust and civility (Flanagan Citation2019); in short, the infrastructure for order in daily life. This work has historically and predominantly been performed by women and has been relatively low paid. Reappraising just transitions towards adaptation concurrently proposes re-examining the work society values and how this ‘value’ intersects with moving to low-carbon economies and societies.

In sum while mitigation is urgent, arguably we should acknowledge our lives in an already climate changed world. This recognition necessitates engagement with the additional implications of climate adaptation on work. Therefore, gender sensitivity in climate change more broadly is crucial in informing a just transition as particular government policies may reproduce power relations in the labour market, promote essentialist norms on roles of men and women regarding unpaid work, and unequal resource distribution to men and women in transitions from fossil fuel intensive energy production. In this environment, voices and experiences of disaster survivors adopt a reinvigorated significance.

Australia’s gendered climate change dialogue and the untapped potential of women’s voice

The relationship between the women’s movement and climate change highlights the balance between feminist structures within government and their potential to provide opportunities for women’s voice in policy development (Sawer and Gray Jamieson Citation2014). One such expression of women’s voice are the National Women’s Alliances (NWA), a series of bodies that collaborate with Federal Government to inform decision making to ensure women’s voices are heard in the Federal Government’s policy making process (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation2022). In their reports on climate change exacerbated disasters and disaster recovery the NWA thread a careful line, ostensibly concerned with the pragmatics of disaster impact and recovery, while arguably being embedded within broader feminist and ecological concerns on impacts of increasing disasters on women and their livelihoods (Phillips Citation2016). In this way the NWA continue an at times strategically quiet quest to impact policy relevant to women’s livelihoods, including those related to work (Magarey Citation2014), but also highlight concerns on the future of work subject to the consequences of climate change. Hannah Gissane (Citation2016) from the Equality Rights Alliance speaks to this delicate balance arguing that contingent funding of the NWA places restrictions on open criticism of government policy, which is pivotal in shaping industrial relations policies. The vested interests of employer associations in influencing climate change policy, as identified by Goods and Ellem (Citation2022), may further limit the ability to provide constructive feedback. Hence, the focus on producing tangible outputs could prioritise short-term results over addressing the root causes of systemic policy issues pertinent to women’s livelihoods, work and the just transition.

Within the international arena, Australia has officially endorsed a gender perspective as a critical issue for climate action (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Citation2022). Despite a common and self-evident gender lens being applied to climate change by Australia in its international dealings (Tyler and Fairbrother Citation2013) this has not been effectively translated to a domestic policy context in climate change, where Australia is not alone in the developed world (Lau et al. Citation2021; for Canada, see; McNutt and Hawryluk Citation2009). Several governments in developed nations, including the Australian Government, continue to draft climate change policies, programs and practices that are almost universally what Enarson (Citation2012, xix) refers to as ‘stubbornly gender blind’. Indeed, Hazeleger (Citation2013, 41) has noted the ‘pervasive gender-blindness’ in Australia’s emergency recovery plans, despite gender-relevant differential outcomes in women’s health, well-being, and exposure to domestic violence after climate change induced natural disasters. While men and women are viewed as ‘equal’ in the national imagination in Australia, this overrides the complex intersections between discrimination and disadvantage that women face relative to men and their status as ‘other’, leading women to be overlooked in policy debates and development, including on climate change (Magnusdottir and Kronsell Citation2021).

In distinct contrast, the global literature concerning developing nations has a more established focus on gender perspectives. This is likely due to the direct impact of climate change on the work of people in developing countries providing labour for agriculture (Agarwal Citation2010; Ahmed and Fajber Citation2009). Much of this literature cannot be transposed to the lived experience and challenges that women in developed nations face. Indeed, this literature generally overlooks gender perspectives in developed nations, such as Australia, altogether (Magnusdottir and Kronsell Citation2021).

In this context ‘just transition’, particularly as it relates to the intersection between climate change, women and work in Australia has been overlooked (Alston Citation2011). Despite recent intense climate change exacerbated natural disasters in Australia, policy discussion from stakeholders including government, unions and employer associations rarely incorporates a gender lens to consider the implications of climate change mitigation and adaption strategies in the just transition debate. While there have been commitments to improving women’s voice in decision-making processes and bodies (see Commonwealth of Australia Citation2020), and to recognise the different experiences that women and girls face in relation to their safety, economic security, health and well-being (see Commonwealth of Australia Citation2022), climate change and broader environmental issues have been absent from the official Federal Government Women’s Economic Security Statements and Women’s Budget Statements. This is despite the establishment of the NWA and an increase in female representation in the Australian Public Service (Eisenstein Citation1996; Yeatmen Citation2020). However, perhaps marking a shift in focus, the October 2022–23 Women’s Budget Statement includes an inaugural mention of the interaction between climate change and gender (see Commonwealth of Australia Citation2022, 19).

Nonetheless there has been limited evidence of voice in policy debates linking gender relations and climate change implications, mitigation and adaption policy issues. Buckingham and Le Masson (Citation2017, 3) lament the lack of focus on ‘relations in relation to climate change causes, effects, mitigations and adaptions, and the implications of not adopting gender sensitivity in all these places’. Indeed, Nelson (Citation2009) argues that many of women’s traditional responsibilities, including unpaid caring work such as the bearing and raising of children, and caring for the sick and elderly have been neglected from debates surrounding climate policy. While there are instances where men and women may be affected by climate change in similar ways, climate change will also have differential impacts by gender (Nagel Citation2015).

Research on the social implications of climate change has been slow to develop while feminist research into the gender dimensions of climate change adaption and mitigation has been even slower (MacGregor Citation2010). Limited attention to gender perspectives in climate change public policy occurs despite the importance of gender analysis in understanding women’s disproportionate share of unpaid household and caring labour (see Baird Citation2011; Collins et al. Citation2021; Tomlinson et al. Citation2018), vertical and horizontal sector and occupational gender-based segregation and undervaluation (Cortis et al. Citation2023), long-term gender disadvantage in labour markets (see Baird et al. Citation2012; Foley and Cooper Citation2021; Whitehouse and Smith Citation2020), gender based violence after climate change induced natural disasters (see Whittenbury Citation2013), and a lack of recognition of women’s contribution to climate change exacerbated natural disaster response and recovery (Parkinson et al. Citation2022). Hence, an analysis of women’s voice and climate change is crucial as it interrogates the allocation of power over natural resources, economic opportunities and decision-making processes.

While governments in developed nations have increasingly examined impacts of climate change on national wellbeing and development, Australia’s limited focus on a gender perspective in climate policy reflects an assumption that gender is not a defining factor. It therefore is rarely central to decision-making and climate change policy making more broadly (Griffin Cohen Citation2017), despite research linking low-wage workers, predominately women, to disproportionate vulnerability to climate change exacerbated natural disasters (Alston et al. Citation2019).

By focusing on climate adaptation and its literature, this study seeks evidence for the current situation as well identification of key themes to understand how the industrial relations system relates to gender, disadvantage and the necessities of adaptation, with a view to informing our understanding of how to approach the evidenced issues.

Methods

This study uses text-mining and quantitative content analysis of policy documents sourced from the NWA including Gender and Disaster. We use this analysis to answer our central research question: how do women’s experiences of natural disasters inform policy at the intersection of climate adaptation and industrial relations? The NWA documents comprise the nearest relevant corpus of publicly available material relating to climate change policy, just transitions and women in Australia.

The corpus of literature was drawn from policy documents developed by the NWA, six specialist organisations funded by the Australian Federal Government under the Women’s Leadership and Development Program as a part of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. These six organisations include the National Women’s Safety Alliance, Equality Rights Alliance, Harmony Alliance, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Alliance, National Rural Women’s Coalition and Women with Disabilities Australia (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation2022). Literature was also sourced from Gender and Disaster Australia which was initially established in 2015 to highlight the role of gender in survivor responses to climate change induced natural disasters – including increased family violence (Gender and Disaster Citation2022). The resulting corpus of policy documents predominately feature and are grounded in in-depth interviews and surveys from women and men who have experienced climate change exacerbated natural disaster.

Literature from the NWA and Gender and Disaster was chosen for its climate relevance, notably the documents span the years 2011–2022 that correspond to introduction of a carbon pricing scheme by the Gillard Labor government in 2011, and of the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison Coalition governments from the 2013 Federal election where climate change featured prominently in policy debate. The time frame 2011–2022 also captures the period immediately succeeding the repeal of Australia’s carbon pricing scheme on 17 July 2014, where emissions resumed their growth evident before the introduction of the carbon price (Department of Parliamentary Services Citation2014).

The NWA document set was analysed using text-mining, correspondence analysis, co-occurrence network analysis using KHCoder (see KHCoder Citation2016). The relevant literature and codes are summarised in . These text-mining and analysis methods are used to identify key terms and language developed by the NWA (for an example see Yamada Citation2021). Once highest occurring words and phrases have been identified, co-occurrence and correspondence analysis is used to find associations between these words and phrases. These associations point to the places in the documents where concepts are brought together, which can then be traced back to the document to highlight frequently occurring relationships between significant concepts within the document set (Lock and Seele Citation2015). These identified associations and concepts can then be examined within their context and their meaning re-contextualised within the overall study and explicated. The NWA document set was analysed using text-mining, correspondence analysis, co-occurrence network analysis using KHCoder (see KHCoder Citation2016). The relevant literature and codes are summarised in . These text-mining and analysis methods are used to identify key terms and language developed by the NWA (for an example see Yamada Citation2021). Once highest occurring words and phrases have been identified, co-occurrence and correspondence analysis is used to find associations between these words and phrases. These associations point to the places in the documents where concepts are brought together, which can then be traced back to the document to highlight frequently occurring relationships between significant concepts within the document set (Lock and Seele Citation2015). These identified associations and concepts can then be examined within their context and their meaning re-contextualised within the overall study and explicated.

Table 1. The national women’s alliances document codes and names.

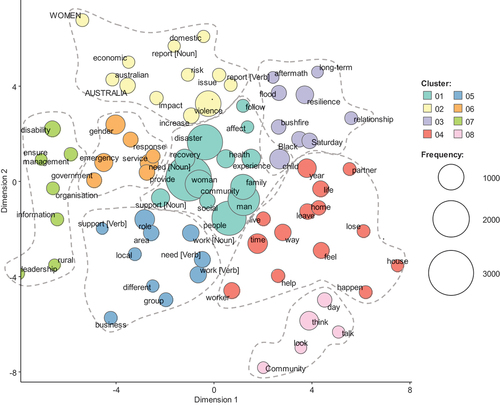

Once a corpus was established, a two-stage process was undertaken to analyse the documents. The first stage was a quantitative content analysis, including developing a co-word network which was then visualised using multi-dimensional scaling (MDS). KHCoder provided descriptive statistics on word frequencies and allowed searching for individual terms to identify local word co-occurrence networks as well as examining any target word in its original context.

MDS graphic proximity represents words with high degrees of co-occurrence as closer together on a 2- or 3-dimensional plane (for a detailed discussion of correspondence and quanitative text analysis see Fytilakos Citation2021). We have chosen a 2-dimensional plane for readability. The MDS visualisation also represents how frequently the word appears (see ), with larger circles indicating greater word frequencies. A cluster analysis was also performed based on the score obtained in the MDS, using the Ward method based on Euclidean distance where words plotted close to each other are classified under the same cluster. This clustering allows associations between words and phrases to be identified: words and phrases that have higher co-occurrence appear closer together and their relationship is likely to be more significant, noting some of these relations are not visible with the 2D visualisation, but will be explained in the text of the paper. High frequency associations can then be traced back to their context in the original documents so they can be further analysed.

Figure 1. National women’s alliances literature KHCoder analysis visualisation.

Quantitative content analysis offers the advantage of replicability and drawing out frequently occurring words, therefore the ability to reveal themes somewhat distinct from the researchers’ expectations of what will emerge (Riffe et al. Citation2019). Pre-processing of documents in the corpus was kept to a minimum to maximise the documents speaking for themselves. A stop word list was developed to remove the most frequently occurring non-content words, examples of common stop words include ‘the’, ‘an’ and ‘of’.

The second stage of analysis involved tracing strongly associated words and phrases back to their context within the corpus documents. The associations that occurred frequently or that occurred at intersections or boundaries between clusters are particularly focused on as they indicate important concepts or where concepts have been brought together by the authors in less expected groupings. Quantitative content analyses use text-mining techniques to identify areas of text that are more likely to indicate analytically significant sections of text. These can then be traced and read in more depth. The following analysis was completed by iteratively moving between the two stages to establish the dominant themes across the corpus and how each was discussed within the context of a document and in relation to the other documents in the corpus.

Mapping women’s voice in Australia’s just transition

The co-occurrence analysis and MDS performed using KHCoder is visualised in . Overall, the co-occurrence analysis suggests that themes related to formal and informal work, balancing work and care as well as maintaining livelihoods emerge as central concerns for women and their communities in the short and long-term aftermath of climate change related disasters. It also emerges that disaster recovery policy is yet to engage with work and livelihood concerns of those who experience climate related natural disaster. Placed within the broader societal and political context in which this corpus was developed, a certain political expediency is displayed where natural disaster and emergency service management is foregrounded and the impetus for climate change mitigation and adaption is backgrounded. In effect this corpus points to recommendations for climate change adaption policy rendered politically tangible within the social and political terrain of its time.

As can be seen in , eight clusters emerged from analysis of the co-occurrence matrix and visualisation of the NWA literature. From an iterative process of quantitative content analysis, examining the resulting keywords in context and their placement within the visualisation these clusters were identified as summarised in :

Table 2. Cluster and co-occurrence analysis of the national women’s alliances literature.

The quantitative content and cluster analysis provides a relatively unadorned insight into the concerns and considerations that emerge from the NWA literature on gender and disaster recovery. These analyses point to potential further research on work, employment and livelihoods to further inform disaster resilience, response, recovery processes and policies. However, it should be noted that the studies and reports that comprise this literature do not examine aspects of work, employment and livelihoods in a systematic or deliberate way. The reports were originally created with the intention of documenting and describing the experiences of disaster survivors from a gendered perspective. Being primarily evidenced by focus groups and long-form interviews the overall coverage of concerns and experiences is very broad and emanate from the methods used. This is beneficial in that respondents are not asked to explicitly speak to issues of work, employment and livelihoods but these issues organically emerge as central to the concerns of disaster survivors. However, this indirect observational approach required another step in our analysis. To move beyond and between the clusters that emerged from the documents, we needed to return to the documents with a focus on issues that relate to work, employment and livelihoods. provides representative quotes from our analysis that translated clusters and correspondences emerging from the quantitative context analysis.

Table 3. Representative quotes derived from following correspondences in the cluster analysis.

In the following sections, we present the results of our analysis of the NWA literature on women’s experiences of natural disaster events and recovery in context of work and climate adaptation.

Themes in women’s experiences: insights from NWA literature

Based on the results four main themes of women’s voice and experience emerge from the NWA literature: 1. ‘Family and community care’, 2. ‘Employment’, 3. ‘Recognition of women’s roles and resilience’ and 4. ‘Natural disaster response and recovery’.

Family and community care

The first theme, family and community care, emerges quite readily from the analysis of NWA literature. Coping with the aftermath of disasters reinforces pre-existing ‘traditional’ gender-roles within families and communities, in turn, exacerbating asymmetrical divisions of household labour and a disproportionate share of unpaid community support work and caring for children and family being taken by women (AWAL-01). The disproportionate share of unpaid care work leaves women inordinately effected by disasters, including natural disasters, and demonstrates one of the gendered faces of disasters. In one instance, evidence points to women with children having little time for natural disaster preparation and fewer skills operating equipment to aid flood or fire damage prevention, survival, rescue and escape; this absence reinforces the male domination of this work (AWHN-01). Evidence from previous Australian bushfires, shows that stereotypes within heterosexual couples of men’s work being involved in fighting fires to protect women and children, with women’s role being one of family and community care are further entrenched (Eriksen and Gill Citation2010).

Women’s caretaking responsibilities at home and in the community render them especially vulnerable. When natural disasters destroy shelters and other safe spaces, women are susceptible to domestic violence as they struggle to rebuild their lives. The co-occurrence analysis in validates the unfortunate centrality of violence as a feature of women’s experience after disaster recovery. Analysis of Australia’s Black Saturday bushfires, a series of fires across the state of Victoria in 2009 which were one of Australia’s all-time worst disasters, indicated that while men feel the need to dutifully defend property, women wished to flee (GEND-04). Hence, post-disaster recoveries are associated with men suffering increased incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder which increases domestic violence against women (Jewkes Citation2002). The financial stresses associated with dislocation and property damage are likely to see internal family unit pressure increasing the risk of domestic violence against women. The increased burden of unpaid community and social care for women indicated in , in combination with geographical dislocation may diminish women’s access to institutional supports, with higher reliance on the perpetrators of domestic violence for financial survival and/or access to essential services (VicHealth Citation2009).

Natural and economic disasters further solidify rigidity and differentiation of gendered roles and social norms. In Australia, more men die in direct response during disasters, but more women die while in a home or fleeing, indicating that gendered social norms and narratives of men as heroic and women as carers shape differential experiences of susceptibility and recovery (GEND-03). The gendered nature of care roles become increasingly rigid as access to public and social infrastructure that supports care during other times becomes limited (ES4W–01). This rigidity and differentiation of gendered roles and social norms lead to a greater risk of economic insecurity for women (ERA-02) and increased vulnerability to insecurity in food, water and electricity supply.

Employment opportunities and economic security

Economic security issues featured in the NWA literature with disaster included increased family and community care demands; by comparison they are generally neglected by official government climate change policy documents. This increase in demand for community, social and health work further entrenches women’s role as carers thereby exacerbating aspects of female disadvantage in employment opportunities.

Women’s disproportionate share of unpaid work during the post-disaster recovery stage prevents the earning of wages, or delays and creates barriers to the return of paid work in the labour market (ES4W–02). For some women, wages for the time taken off work to rebuild from disasters was deducted from pay, leaving many with increased experience of job-insecurity (GEND-03). Furthermore, the time demands women face towards allocating labour towards unpaid caring work diminishes time allocated towards paid work, further exacerbating the gender pay gap, vertical and horizontal segregation (Workplace Gender Equality Agency Citation2020, Citation2022). Overwork is a commonly reported consequence of balancing unpaid forms of labour such as caring and volunteer work. This has been found to have significant health implications, particularly evident in women in rural communities who frequently extend their existing financial contributions with activities like bookkeeping for the farm (AWHN-01).

Climatic and economic disasters leave women disproportionately more economically vulnerable than men. Pre-existing gender norms foster employers’ beliefs that ‘when jobs are scarce, men have a greater right to paid work’ (AWHN-01). These gendered perspectives and their effects are similarly reflected in recovery efforts in natural disasters. The repair and re-establishment of ‘hard’ physical infrastructure, incorporating government generally allocating funding to hard infrastructure and ‘shovel-ready jobs’, is likely to generate immediate employment in male-dominated industries. This is prioritised after natural disasters with limited consideration given to the re-establishment of community-based and female-dominated requirements. This leaves women less likely to be employed in paid recovery efforts (Hazeleger Citation2013), even though many female-dominated sectors such as hospitality and tourism are more vulnerable to reduced discretionary spending and can see the greatest job losses after natural disasters (Hickson and Marshan Citation2022). In contemporary debates around climate change mitigation the focus is heavily weighted towards the impacts on male jobs in male-dominated industries including agriculture, forestry, fishing, fossil fuel extraction and energy utilities (Parkinson et al. Citation2018). However, limited focus is placed on the impact on female-dominated industries that climate change, its mitigation and adaptation are likely to bring, for example, retail, health, education, childcare and hospitality that face threats due to workers moving away from previously carbon intensive industry areas after a loss of employment (AWHN-01). Nor is much consideration given to the rising need for female dominated industries such as health and aged care with the increased impacts of climate change on community health (AWAL-01).

Recognition of women’s roles

Recognising the role women take in disaster recovery and rebuilding in developing resilience within households, families and communities is a key theme across the NWA literature. A lack of recognition is articulated most directly in NWA (Citation2020) report Disaster Recovery for Women: ‘across all areas it was reported that there had been little if any, attempt to acknowledge the extra caring and voluntary responsibilities that women have taken on in the recovery process’ (AWAL-01). The vital role women take in family and community rebuilding before, during and in the aftermath need to be made more visible to mainstream discourse and enable adequate policy and service provisions.

Mainstream public narratives and discourse tend to emphasise the role of males in disaster events, as protectors, firefighters or actively involved with groups such as the State Emergency Service, arguably paying homage to the myth of the male bushfire volunteer that dominates public discourse (Eriksen and Gill Citation2010). However, the NWA literature points to a more nuanced understanding of men’s role in disaster events and in recovery. The Black Saturday Royal Commission found that only a third of fire-affected people attempted to protect properties while women and children flee (Handmer et al. Citation2010). Often, it is women who are left to protect the home or escape with dependants when men are not present, either through paid or volunteer firefighting or for other reasons (De Laine et al. Citation2008; Proudley Citation2008; Raphael et al. Citation2008). The NWA literature indicate the central role women play providing care work and community support in the event of a disaster and during short-term and long-term recovery, these themes remain essentially invisible to the broader public and policy discourse.

The NWA literature also points to a more nuanced understanding of gendered dynamics and decision-making during disaster events and their aftermath than previously recognised. The Australian Women’s Health Network report on the impact on women’s health of climatic and economic disaster speaks to women’s decision-making being curtailed by a traditional and unspoken expectation that the ‘man makes the decisions’, in life-threatening situations the lack of recognition of the value of women’s tendency to take care rather than defend property may have avoided losing lives (GEND-08). Situations such as these point to the importance of recognising gender in decision-making during and in response to disasters. The NWA literature more broadly encourages recognition that sex and gender shape both women’s and men’s lives before, during and after disasters (GEND-02). While men are most frequently portrayed as having decision-making authority and control over key resources, these narratives can increase vulnerability for both men and women.

The NWA literature provides a longer term and community orientated view on disaster events and their aftermath, in turn bringing forward women’s experiences of disasters, rendering their perspectives more visible. From this visibility, the long-term impacts of mental-health, community vulnerabilities and the role women take in rebuilding communities and families emerge. Disasters create an environment where previous gains made by communities in recognising the impacts of mental health and domestic violence on women, families and communities are dissipated (AWHN-01, GEND-08). In disaster affected families and communities the overlapping of ‘violence’ and ‘women’ demonstrate how women are compelled to internalise domestic violence. In the context of post-disaster recovery, the institutional supports and constraints of society are diminished, and women’s reporting of violence is not heard or silenced before it is voiced (Austin Citation2016; Bradshaw Citation2004). The ongoing and extensive burden of increased mental health vulnerabilities and domestic violence, predominately reverting to being rendered highly localised ‘family’ issues, in the aftermath of disasters is a heavy legacy that is revealed as central to women’s experiences of disasters in both the longer and shorter term. Furthermore, the public services established in the post-disaster recovery stage tend to offer economic and physiological support, rather than support towards understanding the incidence of domestic violence (Enarson Citation2012; Houghton Citation2009; Parkinson et al. Citation2011; Sety Citation2012). Despite it appearing as central to women’s experience of disaster evident in the co-occurrence analysis of the NWA literature these issues receive limited recognition within broader disaster conversations.

Natural disaster resilience, response and recovery

Much of the focus of the NWA literature currently focuses primarily on disaster and disaster recovery rather than climate adaption, mitigation and strategy. Almost absent from the co-occurrence analysis of the NWA literature were words and concepts indicative of a direct response to climate change, such as greenhouse gas emissions, use of fossil fuels, job transitions related to decline in fossil fuel use and the uptake of renewable energy, use of carbon sinks including planting trees, or international initiatives to limit global warming to below 2°C including the Paris Agreement.

The word ‘climate’ appears 64 times within this literature and the concept of climate change’s treatment varies according to the authoring groups recognition of the relationship between increasing likelihood of natural disasters and climate change. A progression from disconnection between disasters and climate change can be seen in the series of reports produced by Gender and Disaster Australia between 2011 and 2018. The 2015 report ‘The way he tells it’ explicitly excludes climate change as a disaster as it is a ‘diffused’ disaster. For Gender and Disaster Australia disaster ‘includes natural disasters such as bushfires, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes and cyclones. War, terrorism, drought and climate change are excluded’ (GEND-03). Though this approach significantly under-represents the connection between increasing incidents of climate-related events with climate change, it attempts to direct discussion into the more concrete implications of climate change, being disasters. However, by 2018 recognition of the connection between the increased occurrence of disaster’s due to climate change grows ‘Almost ten years after Black Saturday, Europe is experiencing unprecedented heat and wildfires, and Victoria and other parts of Australia face a farming crisis due to prolonged drought conditions. Fire planning is less certain as climate change brings more frequent and more severe weather events’ (GEND-08).

Within the corpus, one exception to the trend of narrowly focusing on disasters and disaster recovery and implicitly or broadly linking them to climate change is the Australian Women’s Health Network report on ‘The impact on Women’s Health of Climatic and Economic Disaster’ (AWHN-01). This report explicitly links the tripartite concerns of gender inequality, economic inequality and response to climate change, naming the drivers of these resultant inequalities as globalised ‘free-market economics’ and it’s influence on Australian Federal Government policy. This report identifies both long-term (catastrophic bushfires) and short-term (urban heatwaves) climate disasters and clearly recognises that climate related disasters will increase as the effects of climate change magnify. Though the potential utility of applying understanding of disaster preparation, response, recovery and rebuilding to an understanding of climate change impact, mitigation and adaptation goes largely unspecified in the NWA literature it emerges clearly in analysis.

Discussion and conclusion

This article contributes to the contemporary academic discourse on work and climate change with a focus on facilitating gender-sensitive just transitions. It achieves this by conducting a textual analysis of women’s perspectives within the Australian Federal Government policy context, specifically though the examination of the National Women’s Alliances corpus of literature. Thus, this paper provides insight into gendered climate change implications, mitigation efforts, and adaptation strategies, addressing a crucial yet under-researched area in the existing academic literature. The study identifies four main themes that emerge in relation to women’s voice and climate change, as expressed through the National Women’s Alliances corpus of literature: 1. ‘Family and community care,’ 2. ‘Employment’, 3. ‘Recognition of women’s roles’ and 4. ‘Natural disaster response, resilience and recovery’).

The findings of the analysis suggest that women’s voice within the National Women’s Alliances literature is shaped, at least in part, by an awareness of the surrounding unpredictable political landscapes, which oscillates between overtly antagonistic and reluctantly resigned attitudes towards the ramifications of climate change. This observation resonates with Goods and Ellem’s (Citation2022) argument, highlighting the structural and associational influence wielded by employer associations in shaping climate change policies. This underscores a connection between women’s perspectives in the National Women’s Alliances and broader dynamics within the industrial relations scholarship concerning work and climate change.

The examination of NWA literature highlights the importance of incorporating gender considerations into a just transition, taking into account the expected impact on women’s roles in work and household responsibilities. Unless addressed, the likely strain with intensification of natural disasters will disproportionately affect women who already bear a disproportionate share of unpaid care work and paid work in social, community and health services. Further, women’s employment and household responsibilities are likely to be affected differently to men and may contribute to further entrenching existing social and economic inequalities.

Another key contribution of this article is that it identifies a disproportionate focus on the gendered responses to adapting, rather than mitigating climate change. This identification underscores a critical gap in the current discourse, shedding light on the need more a more balanced exploration of gendered dynamics in both the adaptation and mitigation dimensions of climate change initiatives. The analysis reveals a discernible gap in the current literature regarding the intersection of women’s roles in the workforce and their impact on shaping equitable and just transitions. Specifically, the results underscore the need to recognise and amplify women’s voices is discussions surrounding the mitigation of climate change, particularly in the domain of green energy employment. As the world undergoes a significant shift towards sustainable practices, it becomes imperative to acknowledge the gender dimensions inherent in the workforce, including access to decent work for women. By neglecting the gendered aspects of mitigation strategies there is a risk of perpetuating existing inequalities within the workforce and hindering the potential for a gender-sensitive just transition.

While it is valuable to understand reactionary responses to natural disasters, this approach overlooks important aspects of climate change, adaptation and prevention including the just transition to a low-carbon energy future. The increasing importance of decarbonisation speaks to the need for a more complete consideration of the gender sensitive personal and financial constraints that women face (Parkinson et al. Citation2011, Citation2018). For instance, in disaster recovery efforts, while women make up most of the unpaid volunteering roles, men predominate in paid professional roles and in governmental and organisational bodies involved in the design and implementation of policies related to climate change and the environment (Workplace Gender Equality Agency Citation2020). The NWA literature emphasis on natural disaster recovery concurrently provides insights into possible futures when applied in a climate aware context but needs extension to avoid the risk of marginalising women’s voices as Australia restructures to a low-emissions economy. Climate mitigation and adaptation policies that do not consider gender can perpetuate inequalities in the workforce. For instance, policies that prioritise male-dominated industries such as construction and engineering may exclude women from well-paying green jobs. On the other hand, policies that prioritise care work, which is often performed by women, can contribute to the feminisation of poverty and perpetuate low wages and poor working conditions in these sectors. A gender-sensitive just transition must consider not only the impacts of climate change on increasing severity and frequency of climate change events but also the changes that need to be made to industries, workplaces, and communities for possible mitigation and adaptation. Hence, it is essential to examine the interplay between gender, industrial relations and climate change as it is vital to prevent the inadvertent reinforcement of inequalities and mitigate the risk of marginalising vulnerable groups in making the transition to a low-carbon energy future.

The literature on just transition has closely followed the trajectory of climate mitigation imperatives. This alignment has resulted in a predominant focus on economic security within the discourse, with a particular emphasis on the well-being of workers transitioning from high-emitting industries, consequently intertwining the narrative with concerns about national productivity in the realm of work and industrial relations. This discourse fosters a strong focus on the role of male-dominated industries including fossil fuel extraction and mining, and de-centres discourse on women’s employment opportunities and issues of just transition. However, climate change is harder to maintain as an abstract claim in the face of devastating climate events such as droughts, fires and floods, and extreme weather events that directly and increasingly infiltrate lives, livelihoods and communities. Likewise, it is much harder to deny the economic costs of not mitigating and adapting to climate change scenarios.

The NWA literature effectively side-steps the broader politicised and polarising narratives and invites consideration of adaptation policy grounded in the lived experience of communities already facing the effects of climate change. It is telling that, within the Australian context, disaster response and recovery is the fullest expression of engagement with adaptation to climate change that includes women’s perspectives available. The NWA literature successfully bypasses the mainstream divisive and obtuse economy versus climate discourse. However, further research can further rectify a gender inclusive path to climate change adaption policy. It can also inform the foundation of gender-sensitive mitigation policy action.

In seeking to foreground women’s voice in just transitions, this paper has identified an imperative to extend consideration beyond mitigation to adaptation. It has also highlighted the gendered nature of the just transition discourse to date and offers a tangible approach to further examine the intersections between climate policy, women and their livelihoods.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: State: Employed as a Senior Advisor Policy & Strategy at NSW Treasury.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jo Orsatti

Jo Orsatti is a lecturer in Work and Organisational Studies with an interdisciplinary background in work studies, technology, environment and social theory. She received her PhD from the Disciplines of Work and Organisational Studies and Business Information Systems. Her doctoral thesis investigated the employment relationship, voices and citizenship surrounding a variety of social and environmental concerns, such as climate change, innovation and diversity via enterprise social media. She has worked with several industry groups including National Parks Australia and Deloitte. She has published on gender and environmental activism in and around organisations, disaster resilience and recovery and the evolution of green jobs in Australia.

Daniel Dinale

Daniel Dinale is a post-doctoral researcher based at the University of Sydney node of the Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR). He received his PhD degree from the Discipline of Work and Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney Business School. His doctoral thesis focused on cross-national patterns of female employment, motherhood and public policy regarding the reconciliation of employment and family. He has published a book entitled “Women’s Employment and Childbearing in Post-Industrialized Societies – The Fertility Paradox” and has contributed to international journals including Journal of European Social Policy. He has authored reports for Australia’s Fair Work Commission and the former NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet, and co-authored book chapters on working women’s lives and leave policies in the post-COVID era.

References

- Agarwal, B. 2010. Gender and Green Governance: The Political Economy of Women’s Presence within and Beyond Community Forestry. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199569687.001.0001.

- Ahmed, S., and E. Fajber. 2009. “Engendering Adaptation to Climate Variability in Gujarat, India.” Gender & Development 17 (1): 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070802696896.

- Alston, M. 2011. “Gender and Climate Change in Australia.” Journal of Sociology 47 (1): 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783310376848.

- Alston, M., T. Hazeleger, and D. Hargreaves. 2019. Social Work and Disasters: A Handbook for Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Austin, D. W. 2016. “Hyper-masculinity and disaster: The reconstruction of hegemonic masculinity in the wake of calamity.” In Men, Masculinities and Disaster, London and New York, Routledge.

- Baird, M. 2011. “The State, Work and Family in Australia.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22 (18): 3742–3754. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.622922.

- Baird, M., S. Williamson, and A. Heron. 2012. “Women, Work and Policy Settings in Australia in 2011.” Journal of Industrial Relations 54 (3): 326–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185612443780.

- Bradshaw, S. 2004. Socio-Economic Impacts of Natural Disasters: A Gender Analysis. Santiago, Chile: United Nations Publications.

- Buckingham, S., and V. Le Masson, Eds. 2017. Understanding Climate Change Through Gender Relations. London: Routledge.

- Carr, C. 2022. “Repair and Care: Locating the Work of Climate Crisis.” Dialogues in Human Geography 13 (2): 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221088381.

- Collins, C., L. Ruppanner, L. Christin Landivar, and W. J. Scarborough. 2021. “The Gendered Consequences of a Weak Infrastructure of Care: School Reopening Plans and Parents’ Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Gender & Society 35 (2): 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211001300.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2020. Women’s Economic Security Statement – 2020. https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/images/wess/wess-2020-report.pdf.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2022. Women’s Budget Statement 2022–23, Commonwealth of Australia. https://budget.gov.au/2022-23/content/womens-statement/download/womens_budget_statement_2022-23.pdf.

- Commonwealth of Australia. Royal Commissions. 2020. National Natural Disaster Arrangements. 4 https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/natural-disasters.

- Cortis, N., Y. Naidoo, M. Wong, and B. Bradbury. 2023. Gender-Based Occupational Segregation: A National Data Profile. https://www.fwc.gov.au/documents/consultation/gender-based-occupational-segregation-report-2023-11-06.pdf.

- Dean, M., and A. Rainnie. 2021. “Post-COVID-19 Policy Responses to Climate Change: Beyond Capitalism?” Labour and Industry 31 (4): 366–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1979448.

- DeLaine D, Probert J, Pedler T, Goodman H, Rowe C. 2008. “Consulting, Designing, Delivering and Evaluating Pilot women’s Bushfire Safety Skills Workshops.” The International Bushfire Research Conference 2008 – incorporating the 15th annual AFAC Conference, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

- Denham, T., and L. Rickards. 2022. Climate Impacts at Work. https://cur.org.au/cms/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/220926-web-climate-impacts-at-work-pages.pdf.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2022. Australia’s International Support for Gender Equality – Partnerships for Recovery and Gender Equality. https://www.dfat.gov.au/development/topics/development-issues/gender-equality-empowering-women-girls/gender-equality.

- Department of Parliamentary Services. 2014. Federal Election 2013: Issues, Dynamics, Outcomes. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/2956365/upload_binary/2956365.pdf;fileType=application/pdf.

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2022. The National Women’s Alliances. https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/grants-and-funding/national-womens-alliances.

- Douglas, J., and P. McGhee. 2021. “Towards an Understanding of New Zealand Union Responses to Climate Change.” Labour and Industry 31 (1): 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1895483.

- Eisenburg, A. 2019. “Just Transitions.” Southern California Law Review 92 (101): 273–330.

- Eisenstein, H. 1996. Inside Agitators: Australian Femocrats and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Enarson, E. 2012. Women Confronting Natural Disaster: From Vulnerability to Resilience. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Eriksen, C., and N. Gill. 2010. “Bushfire and Everyday Life: Examining the Awareness-Action ‘Gap’ in Changing Rural Landscapes.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 41 (5): 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.05.004.

- Flanagan, F. 2019. “Climate Change and the New Work Order.” Inside Story. February 28. https://insidestory.org.au/climate-change-and-the-new-work-order/.

- Flanagan, F., and C. Goods. 2022. “Climate Change and Industrial Relations: Reflections on an Emerging Field.” Journal of Industrial Relations 64 (4): 479–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856221117441.

- Foley, M., and R. Cooper. 2021. “Workplace Gender Equality in the Post-Pandemic Era: Where to Next?” Journal of Industrial Relations 63 (4): 463–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856211035173.

- Fytilakos, I. 2021. “Text Mining in Fisheries Scientific Literature: A Term Coding Approach.” Ecological Informatics 61:101203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2020.101203.

- Gender and Disaster. 2022. Organisational CV – Gender and Disaster. https://www.genderanddisaster.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/GADAus-CV-2022.pdf.

- Gissane, H. 2016. Networking for Change: The Role of the National Women’s Alliances in the women’s Movement. The power to persuade.https://www.powertopersuade.org.au/blog/networking-for-change-the-role-of-the-national-womens-alliances-in-the-womens-movement-part-1/14/10/2016.

- Goods, C. 2013. “A Just Transition to a Green Economy: Evaluating the Response of Australian Unions.” Australian Bulletin of Labour 39 (2): 13–33.

- Goods, C. 2017. “Climate Change and Employment Relations.” Journal of Industrial Relations 59 (5): 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185617699651.

- Goods, C., and B. Ellem. 2022. “Employer Associations: Climate Change, Power and Politics.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 44 (2): 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831x221081551.

- Griffin Cohen, M., Ed. 2017. Climate Change and Gender in Rich Countries: Work, Public Policy and Action. London: Routledge.

- Handmer, J., S. O’Neil, and D. Killalea. 2010. Review of Fatalities in the February 7, 2009, Bushfires Final Report.

- Hazeleger, T. 2013. “Gender and Disaster Recovery: Strategic Issues and Actions in Australia.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management 28 (4): 40–46.

- Hickson, J., and J. Marshan. 2022. “Labour Market Effects of Bushfires and Floods in Australia: A Gendered Perspective.” Economic Record 98 (S1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12688.

- Houghton, R. 2009. “Domestic Violence Reporting and Disasters in New Zealand.” Regional Development Dialogue 30 (1): 79–90.

- Humphrys, E., J. Goodman, and F. Newman. 2022. “‘Zonked the Hell out’: Climate Change and Heat Stress at Work.” The Economic & Labour Relations Review 33 (2): 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/10353046221092414.

- IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Jewkes, R. 2002. “Intimate Partner Violence: Causes and Prevention.” The Lancet 359 (9315): 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5.

- KHCoder. 2016. KHCoder – Version 3. https://khcoder.net/en/.

- Lau, J. D., D. Kleiber, S. Lawless, and P. J. Cohen. 2021. “Gender Equality in Climate Policy and Practice Hindered by Assumptions.” Nature Climate Change 11 (3): 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00999-7.

- Lock, I., and P. Seele. 2015. “Quantitative Content Analysis As a Method for Business Ethics Research.” Business Ethics: A European Review 24 (S1): S24–S40. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12095.

- MacGregor, S. 2010. “A Stranger Silence Still: The Need for Feminist Social Research on Climate Change.” The Sociological Review 57 (2_suppl): 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01889.x.

- MacNeil, R. 2021. “Swimming Against the Current: Australian Climate Institutions and the Politics of Polarisation.” Environmental Politics 30 (sup1): 162–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1905394.

- Magarey, S. 2014. “Women’s Liberation Was a Movement, Not an Organisation.” Australian Feminist Studies 29 (82): 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2014.976898.

- Magnusdottir, G. L., and A. Kronsell, Eds. 2021. Gender, Intersectionality and Climate Institutions in Industrialised States. London: Routledge.

- Markey, R., and J. McIvor. 2019. “Environmental Bargaining in Australia.” Journal of Industrial Relations 61 (1): 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618814056.

- Masterman-Smith, H. 2010. “Labour Force Participation, Social Inclusion and the Fair Work Act: Current and Carbon-Constrained Contexts.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 45 (2): 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2010.tb00176.x.

- McNutt, K., and S. Hawryluk. 2009. “Women and Climate-Change Policy: Integrating Gender into the Agenda.” InWomen and Public Policy in Canada: Neo-Liberalism and After?, edited by A. Dobrowolsky, 107–124. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press.

- Nagel, J. 2015. Gender and Climate Change: Impacts, Science, Policy. New York: Routledge.

- National Emergency Management Agency, & Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience. 2023. Australian Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub. Retrieved August from https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/disasters/.

- National Women’s Alliances. 2020. “Joint Position Paper: Disaster Recovery, Planning and Management for Women, Their Families, and Their Communities in All Their Diversity” AWAVA. Accessed April 7. https://awava.org.au/2020/04/07/research-and-reports/joint-position-paper-disaster-recovery-planning-and-management-for-women-their-families-and-their-communities-in-all-their-diversity.

- Nelson, J. A. 2009. “Between a Rock and a Soft Place: Ecological and Feminist Economics in Policy Debates.” Ecological Economics 69 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.08.021.

- Parkinson, D., A. Duncan, S. Davie, F. Archer, A. Sutherland, S. O’Malley, J. Jeffrey, B. Pease, A. A. G. Wilson, and M. Gough. 2018. “Victoria’s Gender and Disaster Taskforce: A Retrospective Analysis.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management 33 (3): 50–57. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.792937482433760.

- Parkinson, D., A. Duncan, W. Leonard, and F. Archer. 2022. “Lesbian and Bisexual Women’s Experience of Emergency Management.” Gender Issues 39 (1): 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-021-09276-5.

- Parkinson, D., C. Lancaster, and A. Stewart. 2011. “A numbers game: women and disaster.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 22 (2): S42–S45. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE11442.

- Parliament of Australia. 2022. Select Committee on Australia’s Disaster Resilience. December 4. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Disaster_Resilience/DisasterResilience.

- Phillips, M. 2016. “Embodied Care and Planet Earth: Ecofeminism, Maternalism and Postmaternalism.” Australian Feminist Studies 31 (90): 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2016.1278153.

- Proudley, M. 2008. “Fire, Families and Decisions.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management 23 (1): 37–43. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20081624.

- Raphael, B., M. Taylor, and V. McAndrew. 2008. “Women, Catastrophe and Mental Health.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 42 (1): 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670701732707.

- Ravenswood, K. 2022. “Greening Work–Life Balance: Connecting Work, Caring and the Environment.” Industrial Relations Journal 53 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12351.

- Riffe, D., S. Lacy, F. Fico, and B. Watson. 2019. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. New York: Routledge.

- Sawer, M., and G. Gray Jamieson. 2014. “The Women’s Movement and Government.” Australian Feminist Studies 29 (82): 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2014.971695.

- Sety, M. 2012. “Domestic Violence and Natural Disasters.” Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Thematic Review: 1–10. Sydney, N.S.W. https://library.nzfvc.org.nz/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=3919.

- Snell, D. 2018. “‘Just transition’? Conceptual Challenges Meet Stark Reality in a ‘Transitioning’ Coal Region in Australia.” Globalizations 15 (4): 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1454679.

- Tomlinson, J., M. Baird, P. Berg, and R. Cooper. 2018. “Flexible Careers Across the Life Course: Advancing Theory, Research and Practice.” Human Relations 71 (1): 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717733313.

- Tyler, M., and P. Fairbrother. 2013. “Gender, Masculinity and Bushfire: Australia in an International Context.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management 28 (2): 20–25. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20131670.

- VicHealth. 2009. National Survey on Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women 2009 Changing Cultures, Changing Attitudes – Preventing Violence Against Women: A Summary of Findings.

- Whitehouse, G., and M. Smith. 2020. “Equal Pay for Work of Equal Value, Wage-Setting and the Gender Pay Gap.” Journal of Industrial Relations 62 (4): 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185620943626.

- Whittenbury, K. 2013. “Climate Change, Women’s Health, Wellbeing and Experiences of Gender Based Violence in Australia.” In Research, Action and Policy: Addressing the Gendered Impacts of Climate Change, edited by M. Alston and K. Whittenbury, 207–221 . Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5518-5_15.

- Wilgosh, B., A. H. Sorman, and I. Barcena. 2022. “When Two Movements Collide: Learning from Labour and Environmental Struggles for Future Just Transitions.” Futures 137:102903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2022.102903.

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency. 2020. Governing Bodies, Workplace Gender Equality Agency. https://data.wgea.gov.au/industries/1#governing_bodies_content.

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency. 2022. Australia’s Gender Pay Gap Statistics – February 2022, Workplace Gender Equality Agency. https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Gender_pay_gap_factsheet_feb2022.pdf.

- Yamada, T. 2021. “Transforming the Dynamics of Climate Politics in Japan: Business’ Response to Securitization.” Politics & Governance 9 (4): 65–78. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i4.4427.

- Yeatmen, A. 2020. Bureaucrats, Technocrats, Femocrats: Essays on the Contemporary Australian State. London: Routledge.