ABSTRACT

Much research has been carried out on the discursive dehumanization of non-Anglo Celtic migrants to Australia – especially refugees and asylum seekers. However, this discourse also has an affective dimension that, in Sara Ahmed’s terms, ‘stick’, impressing upon non-white migrants at a corporeal level. Depictions of self and Other in comic zines such as Where Do I Belong? by Silent Army, Villawood: Notes from a Detention Centre by Safdar Ahmed, and The Refugee Art Project’s zine collection clearly demonstrate the ways in which the body is implicated in narratives about migration and asylum. This paper argues that the comic zine medium also allows for ‘something else’ to surface; namely, an excess with an interruptive rhythm. This excess is posited here as a type of ‘diasporic intimacy’—a dystopic and unsuspecting affective force that disrupts the temporal and spatial rhythms of everyday life. By harnessing diasporic intimacies, the comic zines discussed here redeploy sticky and toxic discourses about migration and asylum, creating space for the migrant body to resist and reassemble.

Introduction

Migration studies has a hard time letting go of binaries. Conventionally, sociological models of migration have been based on either macro structures, such as the political economy and nation state, or micro factors, such as individual migrant agencies and desires. Within these models – known as structuralist and voluntarist respectively – there has also been a repertoire of descriptors that take on a polarized dynamic, for example, the voluntarist model argues that migrants are pushed and pulled, and both models involve the binary notions of destination and origin, home and away, past and present. And yet, ‘[e]very story and crisis around immigration reveals that the subject of migration is neither linear nor contained … The dramatis personae involved, the issues and implications, are all geographically dispersed and yet transnationally interconnected’ (Hedge Citation2016, 4). Increasingly, it is recognized that binary models and descriptors do not adequately capture this complex and fractured nature of migration (Papastergiadis and Trimboli Citation2019).

Undoubtedly, migration involves forms of spatial and temporal rupture – when a person migrates from one place to another, a split occurs in their experiences of space and time (Gunew Citation2017; Trimboli Citation2020). This splitting, or site of rupture, tends to be conceptionalised as the moment of migration, the point at which a person (having been pushed or pulled) migrates from one place to another. However, contemporary research on migration framed through any number of lenses (mobility, transnationalism, diaspora, to name just a few) consistently points to the fact that the contemporary migrant occupies a space of intersecting realities that are always moving (Hedge Citation2016; Robertson, Harrris, and Baldassar Citation2017; Papastergiadis and Trimboli Citation2019). Indeed, the experience of past migration is often embodied as a disposition; the possibility of future migration remaining alive (Hage Citation2014). As such, migration is not experienced as a singular split so much as an ongoing splitting, especially for migrants affected by racialization.

In this paper, I examine migrant and refugeeFootnote1 zines and comics I have encountered in recent years, either materially or digitally, to explore what it means for migrants to have to occupy ongoing states of temporal and spatial rupture. In particular, I consider how the state of rupture is represented in these texts, and how this rupture can be an example of, or at least related to, what Svetlana Boym terms ‘diasporic intimacy’ (Citation1998). I read the zines and comics as a form of autographics, a term coined by Gillian Whitlock (Citation2006) to describe a mode of graphic memoir that assembles visual and verbal text and requires different kinds of reading practices than written memoir. Importantly, each autographic allows the subject of racialized migration, the migrant body that bears rupture, to be drawn onto the page as an act of re-animation. Thus, the characters of these texts document the experience of migratory rupture at the same time they actively re-deploy it.

How is a migrant body figured when arrival is constantly (and/or forcibly) deferred by social regimes of movement, or if the experience of racialization at the so-called destination is such that one’s body is unable to fully ‘land’? What room is there for these migrant bodies to resist or find space amidst the restlessness? And, zooming out: if we take these questions as entry points into migration studies, how can they open up the field and help avoid falling into binary typologies?

Migration as accumulative motion

Thomas Nail opens his book The figure of the migrant (Citation2015) with a play on Simone de Beauvoir’s famous line. He writes: ‘One is not born a migrant but becomes one’ (Citation2015, 3), beginning his argument that mobility acts as constitutive of social life in a perpetual manner. Indeed, I would proffer a slight but important reworking of his statement: ‘One is not born a migrant but is becoming one’. In contrast to the models of migration founded on polar points of stasis, Nail argues that motion needs to be the starting point for the theorization of migration. His work adds to that of Aihwa Ong (Citation1999), Nikos Papastergiadis (Citation2000, Citation2012), and Ruchira Ganguly-Scrase and Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt (Citation2016), among others, who have each offered alternative ways to map migration through notions of trans-movement, turbulence, and displacement respectively.

Despite being heavily rooted in political systems theory, and thus different to the approach I employ here, Nail’s work interests me because of its capacity to add to understandings of how the migrant in contemporary society is materially shaped by motion, and, just as importantly, how that motion might be channelled into new kinds of resistance. Nail illustrates how mobility acts as constitutive of social life, rather than, as Papastergiadis writes, ‘the temporary disruption to the timeless feeling of national belonging’ (Citation2012, 49). Additionally, Nail’s book provides an interesting (albeit macro/State-orientated) reading of the emergence of ‘undesirable movers’, including today’s ‘illegal immigrant’, which he traces back to the fifth century figure of the ‘vagabond’. He argues that social movement is regulated by various apparatuses of expulsion that take on territorial, political, juridical, and economic forms. These forces give form to what he identifies as key migrant figures: the nomad, the barbarian, the vagabond, and the proletariat. The emergence of each of these figures is the result of different articulations of movement so that the ‘movement of creation precedes the thing created’ (42). As Michel Foucault (Citation1978) and later Judith Butler (Citation1993, 2) demonstrated, the performative power of discourse is its ability to create that which it names. This performative power is evidenced in Nail’s historical analysis of the four main types of migrants, each of whom emerges as a particular figure in accordance with certain kinds of kinetophobias; that is, a fear of mobility and, in particular, migrants deemed to threaten a State power (see also Papastergiadis Citation2012). Specifically, anyone moving in ways that could potentially undermine the State’s core directive of maintaining and expanding control is targeted, grouped, and ‘moved elsewhere.’ Thus, as Nail observes, when unwanted forms of mobility like vagabondage increased, so too did the types of people deemed to be vagabonds. In short, when unwanted forms of movement increased, more types of unwanted movers are produced.

Nail’s analysis of these four historical migrant figures provides a way to conceptualize the formation of migrant figures in the twenty-first century. Today’s most undesired mover is undoubtedly the asylum seeker, referred to in many Western countries as an ‘illegal immigrant.’ Nail traces the emergence of the ‘illegal’ migrant to the period between the fifth and fifteenth centuries, where it surfaced as the figure of the vagabond. In his typology, the vagabond differed from its former counterparts – the nomad and the barbarian – however, due to the kinetic politics in play, it was not a completely new subject. Kinetic politics, in this instance, refers to the politicization of movement or mobility, in service of the state or power, to de-legitimize a group who are perceived to threaten power (see Suliman Citation2017). As such, the vagabond encapsulated the undesirable movers of earlier periods. Similarly, the nomad and the barbarian of former historical periods did not disappear but persisted in new forms, ultimately becoming refigured as the criminalized subject, or vagabond (2015, 65).

In a similar way, we can see the vagabond of the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries reflected in today’s asylum seeker. The vagabond was first demarcated in response to a perceived threat from serfs or slaves who were developing a sense of ownership over their labour, and beginning to recognize ‘the arbitrariness of feudal power relations’ (Nail Citation2015, 68). If these vagabonds were not expelled for demanding some entitlement of their labour, they were expelled via privatization of land, which forced them into a position of displacement and further roaming. Vagabond laws expanded accordingly, isolating wandering workers, beggars, and people with illnesses or belief systems that were deemed to be a threat to the working ‘health’ of the State. Often these vagabonds were expelled to external outposts (Nail Citation2015, 71), such as working camps, sick camps, or prisons. The act of expelling these people legitimated the reasons for their initial expulsion; for example, once someone was in a sick camp they were likely to become much sicker, thereby justifying their ejection (Nail Citation2015, 72). This strategy plays out in the contemporary West: the asylum seeker of the twenty-first century is first expelled from their home country, and then expelled from their destination or transit country to a refugee camp or, in Australia, an offshore detention centre. This asylum seeker is frequently associated with disease, animalism, and revolt (where revolt equates to a ‘terror attack’). The conditions within detention centres are incredibly poor, causing sickness and often compelling strikes and riots (see, for example, Fiske Citation2016; West Citation2018). The image of the ill, protesting asylum seeker helps to legitimate the figure of the asylum seeker as a violent threat to the Australian state, thereby ‘justifying’ their expulsion.

The key point for the purposes of this paper’s provocation is that these unwanted movers are not new subjects, but people bearing accumulative histories of undesirable mobility. The so-called refugee crisis of the twenty-first century is the material accumulation of a racism of many moving parts, a racism with historical momentum; it’s subject, the non-white refugee, is the result of different articulations of movement, where ‘movement of creation precedes the thing created’ (Nail Citation2015, 42). In Australia, the non-white refugee is recognized as being ‘already out-of-place’, because to recognize is, as Sara Ahmed argues, ‘to know again’ (Citation2000, 22). The differentiation of migrant figures – those who figure more and those who figure less – was pronounced in the recent Western-European discourse about the Ukranian-Russian 2022 war, in contrast to the same discourse about Afghan refugees fleeing the Taliban in August 2021. The Ukranian refugee was recognized in a way that is familiar; the Afghan refugee recognized for their ‘out-of-place’-ness. Indeed, even within the Ukranian refugee population, the figuring of migrants on a racialized basis took place: white Ukranian asylum seekers reportedly had a much easier time finding refuge in Europe, as opposed to black Ukranians who reported being turned away at borders (Ali Citation2022; Morrice Citation2022, 253). A kinetic model of migration allows us to think about how some migrants come to ‘figure less’ and some come to ‘figure more’. Histories of mobilities move ahead in time, so the migrant is always a subject-in-motion. However, some migrants bear the accumulated impact of undesirability and racialization.

The notion of a subject-in-motion returns me to the idea of rupture and the ways in which rupture becomes an epistemological position for some migrants. Rupture always involves movement, so if a subject is in rupture it is also in motion. But: is it in motion towards something, and if so, what? It is here that the binary plaguing migration studies seems to sneak in: the question of the ‘something’ quickly collapses into a particular place and time, a particular reality. This reality is co-positioned against another discrete reality, for example, the subject is moving from here to there, from past to future, and so on. As discussed earlier, reading migration as linear movement between dual locations is not adequate for mapping the complex and fragmented experience of contemporary migration. Even more problematic is that the binary conceptualizations of migration studies ultimately lean on a Western liberalist typology in which a Master-Slave dialectic is firmly embedded – even when, as Gayatri Spivak (Citation2012, 335–350) unpacks, migration is situated within the context of globalization and multiple modernities (see also Gunew Citation2009, Citation2017). After all, we are all subjects-in-motion, but we are not all subjects-in-motion in the same manner or on the same terms. As Dipesh Chakrabarty (Citation2000) argues in his conceptualization of the ‘First Europe, then elsewhere’ time structure: the West has already ‘arrived’ but ‘the rest’ is still moving, waiting to be allowed in. Racialized migrants are in motion but this motion is often contained with a liminal space between past and present – they have left one time but they are unable to fully arrive in the new time. Indeed, Helen Ngo’s (Citation2019, 242) re-reading of Alia Al-Saji’s (Citation2009) and Charles Mills’ (Citation2014) works on racialized time goes a step further to show how this movement is often contained within the past indefinitely, or at least, ‘dispositionally oriented towards it’.

Temporal disjointedness is certainly common to the way comic artists Rachel Ang and Safdar Ahmed experience life in Australia. In 2018, I facilitated a panel event at the Institute for Postcolonial Studies in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia on comics and diaspora. The panel featured Naarm-based artist Rachel Ang, and Eora-/Sydney-based academic-artist Safdar Ahmed, both of whom work with comics to explore cultural identity, diaspora, and racialization. I was keen to have them reflect on how they felt the comic medium enabled them to navigate the experience of rupture that diaspora and migration inevitably involve. Ang responded that she was not sure how to think about her artwork as alleviating the experience of rupture, because she still felt as though she was in the rupture. Despite being born in Australia thirty years ago, her racialized experience of being Asian-Australian made her feel as though the rupture was ongoing. Safdar Ahmed concurred, sharing his ongoing anxiety about being Muslim-Australian, especially since 9/11 and heightened Islamophobia in Australia.

Ang’s and Safdar Ahmed’s comments reminded me of a comment by the anthropologist Ghassan Hage, when he spoke at a small community-arts event in 2016, also in Naarm. He was reflecting on his experience of returning to his family home after an evening out in Lebanon as a young adult, only to discover abruptly from his panicked parents that the civil war had started. Hage said: ‘my life changed in a split second […] Suddenly, there was the possibility of things disintegrating overnight’ (2016, in person). He added that he had never fully stopped living that possibility, despite living in Australia for decades. There are, of course, important differences between the experiences of refugees/displaced migrants and migrants who experience subjective displacement due to racialization, and they should not be seamlessly conflated. However, for the purposes of this paper, it is (what I see to be) their common experiences of rupture that I want to examine theoretically.

Migration models that lean on enduring binaries are incapable of attending to the ongoing experience of migratory disruption that Ang, Safdar Ahmed, and Hage all describe. The kind of rupture they experience is not a singular moment as we might often imagine it, but an activated mode of subjectivity and hyper-vigilance. In this framework there is no past/present; home/away; origin/detination. The fact that both Ang and Safdar Ahmed were born in Australia and yet experience perpetual unsettledness because of enduring racism illustrates how necessary it is for migration to be reconceptualized both spatially and temporally.

Counter-memorial aesthetics in migrant autographics

What room is there for resistance and affirmative politics if one is having to embody the possibility of their existence ‘disintegrating overnight’ (Hage 2016, in person)? How can a racialized migrant unbind themselves from the ‘burden of the past’ (Ngo Citation2019) if their experiences of migration are constantly relegated to ‘elsewhere’ times and locations offset against the present? Artistic interventions are frequently acknowledged as being a channel through which abject Others negotiate the terms of their belonging and push back against racialized discourses that work to contain them. Aesthetic practice can help open up the rigid, binary dimensions usually afforded to racialized migrants, at the same time that it can create spaces of respite from the ongoing feeling of turbulence. Sudeep Dasgupta (Citation2019, 102) describes:

Migrants […] cannot be described as stable bodies trespassing across equaly stable territorial, cultural and social borders. Instead, the contemporary forms of globalization reveal that bodies produce spaces of coexistence rather than trespass into spaces which separate the globe. […] The aesthetic experiences furnished by artworks can provide a sensorially intense and intellectually fruitful apprehension of a less oppressive, more inclusive, relational and dynamic understanding of the movements of people in the contemporary world. The dynamic, shape-shifting, aesthetic experience of migration afforded by art can alter the fixed meanings ascribed to spaces by opening up spaces to bodies, realities and histories that are entangled together through processes of displacement.

Of course, artistic works are not somehow removed from the problems that plague all forms of representation. Artistic representations of migration can also fall into the racialized binaries that they are attempting to undo (see Gunew Citation2009; Trimboli Citation2020). Veronica Tello’s book Counter-Memorial Aesthetics (2006) argues, for example, that the ‘bare life’ of refugees is a common focal point of artworks that explore refugee experiences and this often reinstates the less-than-human status of the refugee as a performative accomplishment. There has certainly been a good deal of exploration of how refugee testimonies get consumed by privileged audiences or become the ‘suffering subject’ of dark anthropological studies (see, for example, Robbins Citation2013; Perera and Pugliese Citation2018). Some postcolonial scholars, Rey Chow (Citation2014) a notable example, have gone so far to say that artistic interventions with an auto/biographical bent can never fully unbind themselves from the lockhold of racialization.

As a counterpoint, Sneja Gunew’s (Citation2009) ‘Between auto/biography and theory: Can “ethnic abjects” write theory?’, shows how artistic interventions, particularly migrant writing, can function as a mirror that turns back onto a dominant gaze, thereby undoing racialized binaries and creating a platform of agency. In her latest book, Gunew (Citation2017) extends this to show how the migrant condition is actively re-mediating cultural encounters, creating a critical form of cosmopolitanism that displaces it from the Master-Slave dialectic haunting migrant creative practice.

Similarly, Tello argues there is an emerging aesthetic in refugee artworks that greatly troubles the racialized tendencies of many refugee representations. They identify the following characteristics in this emerging aesthetic, and term them: ‘counter-memorial aesthetics’: 1. contemporaneity – being in time rather than thinking as past or future; constructing both past and future temporalities but never fully dwelling in either; 2. desubjectivisation rather than identification; 3. techniques of negation and antagonism; 4. the use of heterogeneity as a process of world-picturing; 5. embodies critical reflexivity; the mode of the artwork is itself disassembled; and 6. the use of irony and humour (Citation2016, 10–35). Tello sees these characteristcs as reflective of an active diasporic aesthetic.

Autographics, as coined by Whitlock, are a rich artistic site at which Gunew’s and Tello’s arguments intersect. Whitlock (Citation2006, 966) conceptualized autographics as a particular kind of graphic narrative, so as to ‘draw attention to the specific conjunctions of visual and verbal text in this genre of autobiography, and also to the subject positions that narrators negotiate in and through comics’. The comic has become a popular site for migrant and refugee autobiography, particularly in the Australian context, as Safdar Ahmed (Citation2021, online) details. Further, zines by migrants frequently take the form of the ‘perzine’ or personal zine, ‘an autobiographical mode that takes the author’s life or experiences as the focus’ (Douglas and Poletti Citation2016, 180). Importantly, the zine format blends with the comic-style content giving the author creative space to dynamically represent their vast experiences of displacement and everyday life. This is especially useful for refugees, who can also push back against the common tendency for their humanity to be rendered invisible or, just as problematic, visible in one-dimensional formats (O’Brien Citation2019). There is, ultimately, something moving in migrant autographics, and it is to this movement I turn to now in my reading of comics and zines.

Zines of Rupture:The Refugee Art Project zine collection and Muslim Zombies

The Refugee Art Project began in 2011 when Safdar Ahmed and a few other artists began running weekly art workshops in the Villawood Detention Centre in Eora/Sydney. Detained in Villawood were refugees from Iran, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. The artists would take art materials into the Visiting Area every week. Safdar Ahmed (Citation2020, online). describes:

many had been held for around two years, after committing no crime, with no idea of when they would be released. This created intense uncertainty, stress and illness, and so our gatherings weren’t really ‘workshops’ as such, but social events where people could relax amongst friends and try to draw something for fun or to develop a new skill

The response from the detained refugees was positive: ‘participants discovered an aptitude and enjoyment for art, and a few told me they did it as a point of immersion and relief from the daily stressors of being locked up’ (Ahmed Citation2020, online).

Over time, as more art was produced, the Refugee Art Project began exploring ways for artwork to be shared or exhibited publicly. Zines became one of the primary mediums through which to do this. Zines are small, self-published texts, usually A5 in size and made on a photocopier, each consisting of 1–30 pages. The internet has ensured zines ‘remain a dynamic international network of publishing and reading, where the handmade text has gained importance in juxtaposition to the ease of online “push button” publishing’ (Douglas and Poletti Citation2016, 180). Zines are traded and sold at cost price, often directly from the author, and although some make their way online, many do not. Instead, they are printed in small, limited runs and distributed haphazardly in both private and public spaces (Poletti Citation2008, 183–184). These qualities give the zine an ephemeral, enigmatic quality. Comics and zines are closely related and draw on one other in a fluid manner. Comics are often distributed as zines, and non-comic zines often incorporate comic aesthetics within them, in addition to other popular zine practices, such as cutting-and-pasting and collage. Digitization adds another layer to this aesthetic – because sound can be incorporated along with moving image and montage. Although, in the case of the Refuguee Art Project, the digital works remain quite straightforward – usually static images that are not digitally complex.

The accessibility of the zine – both in terms of its lo-fi DIY mode and its ephemeral quality, was highly suited to the aims of the Refugee Art Project, which worked to enable artistic production within highly securatized environments and then share it externally. Zines could be produced cheaply and with the use of minimal art materials, at the same time that they could defy the high level of surveillance placed on detainees in Villawood. Safdar Ahmed explains that, due to restrictions placed on objects moving in and out of Villawood, the main tools of expression became sketchbooks, pens, and pencils. The artworks produced could then be more easily transported out of the confines of the Centre for sharing.

Taking objects out of the detention centre was always tricky because they wanted you to put the stuff through property, and one time they lost someone’s canvases in the process, but drawings were easily slipped into my sketchbook and taken out under the arm. We would scan the images and put the books together in InDesign. A PDF was sent to the printers, to return as books [zines] a few weeks later.

There is something to be said about the way the ephemeral quality of zines and their materiality become linked in the context of the Refugee Art Project. Paradoxically, it is the slipperiness of the zine format, its enigmatic nature, that enables the refugee artworks to become more materially present in the world. The digitization of the zines and comics by the Refugee Art Project serves to enhance this outcome; that is, an audience is often led to the material object (the physical zine itself) by first encountering it (or parts thereof) online. Many of the Refugee Art Project’s zines have been shared and published online, first on a Tumblr site and later a website and an Instagram page – indeed, this is how I first came across the zines and investigated how to purchase hard copies.

The sharing of the zines physically and online allows refugees to ‘[r]ecount intimate memories within a larger project of bearing witness to an unrecorded history’ (Khadem Citation2018, 480). Additionally, while the autographic mode frames these narratives, it does so in more unbridled ways. As such, counter-memorial characteristics are easily identifiable in the Refugee Art Project’s comics and zines. Authors create particular combinations of images, narrative and blank space (through page margins and comic strip gutters, for example), storying their experiences in ways that feels more open and ‘on their own terms’ (Ahmed Citation2021, online). Reflecting on the Refugee Art Project artists, Safdar Ahmed describes:

For some, this meant grasping the opportunity to address their political situation. Some would depict the difficulties they faced in their home country, or the punishment they were experiencing in detention. For others it was the chance to practice culture in myriad ways, to draw religious symbols or deities, or to develop escapist or fantastical themes.

Crucially, autographics allow new forms of telling and listening, so the act of bearing witness acquires a depth and nuance not always present in traditional forms of storying. Autographics ‘[i]nterrupt static media images with the plenitude, fragmentation, and unruliness of the comic’s page.’ (Rifkind Citation2017, 649).

The ‘unruliness’ of the comic’s page can be aesthetically representative of the unruliness of migration and the traumatic experience that some forms of migration entail. For refugees and other racialized migrants dwelling in the space of rupture-by-migration, the autographic can, as Hillary Chute argues, challenge tendencies in cultural theory pertaining to trauma. In particular, they ‘require a rethinking of the dominant tropes of unspeakability, invisibility, and inaudibility that have tended to characterize recent trauma theory’ (Chute Citation2008, 93). Comics and zines enable their authors to recalibrate the ways their bodies, and the spaces they occupy, are typically constructed by others and made foreign through trauma. Integral to many comics and zines is a tussling with the subject position of the narrator, who as Poletti (Citation2008) notes, uses image, text, and the materiality of the zine itself strategically. This subjective tussle is embroiled in the materiality of the text leaving ‘traces’ of the author’s body (Whitlock and Poletti Citation2008). The fact that authors can ‘literally reappear – in the form of a legible, drawn body on the page – at the site of their inscriptional effacement’ means authors can ‘materially retrace inscriptional effacement; they reconstruct and repeat in order to counteract’ (Chute Citation2008, 93).

In fact, the zines and comics produced via The Refugee Art Project leave doubled traces of the authors’ bodies: the material imprint of the author who has created the work, as well as the ghostly nature of the refugee more broadly. A refugee body is an abject body, a body that is both too much body and not enough body simultaneously. As Michel O’Brien (Citation2019) articulates, the refugee body is rendered invisible but this rendering stems from racialized visibility. This contradictory mode of corporeal (non)existence is affectively palpable in the texts by Refugee Art Project. As the bearer of rupture, it is not surprising that refugees frequently depict themselves as monsters, ghosts, and zombies – their bodies excruciatingly visible and yet despairingly transparent. Written text accompanying the images often includes statements such as: ‘get rid of the sick mind’; ‘I don’t belong to myself, I’m lost … ” However, characters in the Refugee Art Project comics and zines also actively engage this precarious existence so as to both reflect and deflect this liminal subjective positioning. In ‘Sleep Cycle in Villawood’, a comic strip by Alway, Talha, and Zeina (Citation2015), the narrator feels diminished by the zombie-like crowd during the day at Villawood, and chooses another type of routine. This routine is that of another nonhuman trope – the vampire – another not-quite alive not-quite dead character that thrives on humans. Choosing a vampire routine rather than a zombie routine is far from a moment of liberation, but it is a considered act of resistance, which is then accentuated by the sharing of this experience through the project.

I like to avoid the daytime … All I see during the day are the same sad faces. They feel sorry for me, I feel sorry for them. At night, after 2am, there is hardly anyone around. This is the time I’m awake. I can use any room I want without the crowd. I feel more relaxed.

Here, the refugee deliberately thwarts their everyday, creating space for themselves to relax by deliberately distancing themselves from the common daily rhythm of the detention centre. In her research on the ‘daily individual interactions and social relations’ of detainees in Australian detention centres, Lucy Fiske (Citation2016, 2) explains how refugee resistance can be large and publicly-facing, but it can also be subtle and interpersonal. Fiske (Citation2016, 7–8) writes:

Resistance may take the form of non-compliance with directives or work ‘go-slows’, actions that can be difficult to police and which rarely come to public light, but which nonetheless aim to subvert, frustrate or directly challenge immigration detention, through to more explicit protests such as hunger strikes, escapes or riots.

Alway, Talha, and Zeina’s zine thus demonstrates a type of estrangment as pedagogy, where one learns to be themselves under surveillance (Muller 1999 in Gunew Citation2017, 39).

Similarly, in the children’s refugee comic zine Mr Man from the Garden (Citationn.d), the figure of the poltergeist is inverted, creating an aesthetic of refusal by ‘turning the mirror’ (Gunew Citation2009) back onto white Australia. The ghost that haunts is not the refugee, ‘Mr Man’, but the colonial legacy of Australia, represented by the Immigration Officer. Mr Man spends his days trying to enjoy his peaceful garden, which throughout the zine comes to stand not only for a literal garden (a place where he can live at ease), but a symbolic garden; that is, Mr Man’s mind and imagination. The Immigration Officer’s persistent surveillance and punitive measures disrupt Mr Man’s attempts to find peace, ruining his garden. However, despite harassment and disturbance, Mr Man persistently returns to thoughts of his peaceful garden, imagining it and re-imaging it. In the end, Mr Man’s garden is too robust for the bully ghost to exist, causing it to eventually give up and skulk away. The accumulated racialization the refugee bodies carry is persistently and cleverly moved elsewhere in these zines, in this case it departs with the defeated white Immigration Officer.

In Safdar Ahmed’s comic zine and essay, Islamophobia: Night of the Muslim Zombies (INMZ) (Ahmed Citation2015), the monstrous Muslim Other as constructed by white Australia is appropriated with gusto. Islamaphobia has been rampant in Australia since 9/11; Muslim bodies are persistently described as sickening the nation, the latter of which is represented as the white, healthy body. This situation is captured by the heinous comment made by former One Nation Senator Pauline Hanson in a Citation2017 interview: ‘Let me put it in this analogy – we have a disease, we vaccinate ourselves against it. Islam is a disease; we need to vaccinate ourselves against that.’

The abjection of the Muslim Australian as toxic, sickly, and life-sucking is exaggerated to (quite literally) comic ends by Safdar Ahmed. His zine includes a scholarly essay that gives a historical account of the zombie as a racialized trope. Interspersed with this sharp analysis are page-size illustrations that resemble posters, each of which play on the grotesque figure of the zombie. For example, ‘Zombie boat people’ features an asylum seeker ship with Muslim men aboard, some of whom have become zombies, and capitalized text above the ship reads: ‘ZOMBIE BOAT PEOPLE: THEY JUMP QUEUES TO JUMP YOU’. A zombie with a skull for a head peers at the viewer from the side of the page, slyly shouting ‘Land Ahoy!’ in a speech bubble. In another, a Muslim zombie man pushes a trolley full of assorted limbs, browsing an aisle full of heads, the text above reading: ‘MUSLIM ZOMBIE SHOPPING MALL.’

Safdar Ahmed’s comics are an example of Imogen Tyler’s conceptualisaiton of ‘revolting testimony’, and which Whitlock (Citation2015) uses in her analysis of testimony made on board the asylum seeker boat the Triton. Revolting testimony actively uses its abjection to enact a form of resistance, speaking to what it means to be made abject, to be made a revolting subject: ‘This injury then becomes a site of transformation and social activism’ (Whitlock Citation2015, 259). The strategy in INMZ is similar to the kind of storytelling that Amir Khadem (Citation2017) reads in Mana Neyestani’s graphic novel Iranian Metamorphosis, in which an ‘ironic connection’ and ‘embodiment transformation’ corroborate.

the narrative strategy—disappointing the readers’ familiar anticipation while highlighting such a disappointment as an integral element for maintaining empathy—becomes the book’s signature diagetic formula.

Safdar Ahmed’s artworks create a laugh, but it’s an uncomfortable laugh, a laugh that awkwardly scrapes against the implied white viewer. At the same time, Safdar Ahmed is clearly speaking over the top of that white viewer, to an audience of alterity. The joke is not on the Muslim Other, and the white viewer must sit with this discomfort and displacement, even if momentarily, highlighting ‘the metaphors that constrain our imaginings’ (Gunew Citation2017, 43).

Safdar Ahmed’s comic creates what Tello might describe as a ‘dizzying’ and contradictory aesthetic, activating the vacillatory movement of im/mobility. However, this kind of aesthetic movement is not a floundering form of movement, but in Jacques Ranciere’s framework, a deliberate ‘movement out of a situation’. The narrative and aesthetic re-routings presented in these comics not only provide space for the subjects to ‘move out of a situation’, but, crucially, also rattle the network of whiteness which holds them in these situations. Sara Ahmed (Citation2007) argues that whiteness holds its place in dominant culture by a repeated and accumlated geneology; a point that extends the argument made by Nail. Autographics such as these disrupt that accumulation, confusing and dis-placing whiteness. Describing the Refugee Art Project zines, Safdar Ahmed states:

Regarding the public I hope people are shocked by Australia’s treatment of refugees but also struck by the power, depth, variety, quirkiness and richness of the work on display. Refugees should not be viewed only through the lens of their trauma or persecution, which is a reductive and ultimately demeaning way to be framed. Against this I think our zines reflect the richness and complexity of people’s experiences, which hopefully provides a fuller, more realistic picture of how people assert their agency and personality than the shallow stereotype of the poor, suffering refugee who needs our ‘help’.

In all of these ways, the comics and zines made by the Refugee Art Project poignantly illustrate Douglas and Poletti’s (Citation2016, 192) argument that zine making is a a metonym for creating a meaningful life and seeking self-determination: ‘zinesters enact the labour, commitment and care that they discover is needed to live a life they can bear’.

Diasporic intimacy and finding resistance in rupture

Crucially, the counter-memorial aesthetics present in these comics and zines are not just a movement but an ongoing moving out of a situation; they never settle on a resolved future or reality. Other realities are alluded to, even experimented with, but they never fully take hold. Thus, the Refugee Art Project’s autographic style:

explicitly refuses an explanatory paradigm for describing the crisis for refugees today. This paradigm, which maps the world in terms of invasion and threat, incursion and expulsion, boundaries and walls, is powerfully but gently displaced by the fragmented and networked visual kaleidoscope […] depicting movement as a relational, dynamic and partly inscrutable process.

The urge to locate a ‘something beyond’ motion is indefinitely suspended, avoiding the problematic tendency to fall into the binary, racialized modes of representation earlier discussed.

Indeed, there is an ambivalence in all of these comic narratives, that appears as a ‘living with excess’ (Tello Citation2016). As I move forward with this research, I want to explore this excess as indicative of what Svetlana Boym (Citation1998, Citation2007) calls diasporic intimacy – the pangs of emotion that, in her words ‘sneak in through the back door. (1998, 501). These unsuspecting affects sneak into migrants’ business-as-usual situations, restructuring the moment of experience. Often, these pangs are difficult to manage – showing up unannounced, disrupting the temporal and spatial moment that is often already a disrupted mode of living. Speaking of this diasporic predicament in 2016, Hage described: ‘Reality lures you to trust it; it incites you to trust it, and sometimes it succeeds. And then somehow it can mug you and so today I am haunted by the possibility of being mugged by reality.’

When analysing diasporic writing, Gunew (Citation2017, 39) notes that there is, for abject authors, ‘an inability to trust the everyday [much less see it as a refuge]; there is no stability to anchor even one’s waking conscious moments’. But, she also notes the double-edged sword that is the abject subject's distrust:

Abjection resides on that borderline that decays into the ambiguous slimy dimension between solid and liquid, between human and inhuman, and meaning and non-meaning, hence its potency within cultural theory because it overcomes absolute binaries: thus neither/nor; both/and. The minute abjection becomes linked with supposedly solid concepts such as the human, language, nation and so forth, it generates a penumbra, including affective anxiety, but this ambiguity may also hold potential for other futures. These dynamics are exacerbated by the ways mobility is conceived

Ironically, then, it is through abject rupture that space is carved out for the racialized body, creating possibilities for “‘both-and’ and ‘what else’ mode[s] of being in the world’ (Jagoda in Boym 2009, 174). I thus want to think about how diasporic intimacies can create a mode of politics, not only in extreme modes of rupture, but in everyday modes of rupture, where the racialized body, such as Hage’s and Ang’s, is made to feel like it might be mugged by its own reality at any moment. Inspired by Sara Motta (Citation2016), I want to further explore (via these kinds of autographics) how a ‘deliberate dwelling in the temporality of the Other,’ can become a method of re-rooting that occurs by ‘listening to the monstrous inner Other, to all that has been exiled.’ For Motta (Citation2016) this is a critical and intimate act of resistance for abject subjects, a way to weather the ruptured mode of being by ‘sitting inside’ and slackening the pace of the movement they’re immersed within. It is perhaps for this reason that, when I asked Ang to reflect on the common visual technique of the ‘gap’ in her comic strips, she responded: ‘sometimes that gap is really small – but other times: I need that gap to be really big.’ Reading Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Chute (Citation2008, 98) comments on the use of Satrapi’s spare or even ‘entirely black’ background panels. For Chute, the visual emptiness in this instance is related to memory, portraying ‘not the scarcity of memory, but rather its thickness, its depth’ (2008, 98). This thickness and depth resembles Ang’s use of the gap, and is strategically conjured within migrant graphic narratives as a form of diasporic comfort: a way of sitting inside abjection.

I find the adaptive quality and surprise agency of diasporic intimacy and rupture poignantly illustrated in Accident: A Story of Entrapment, by Michael Fikaris and Osme (Citation2015). The comic shares one of Osme’s experiences of exile in East Timor as a six year old boy. Osme and his two friends try to cross military guards to visit the town but are inevitably caught. As punishment, the Commanding Officer orders the youths to somersault up to the edge of the jungle and back:

The boys began to roll but the bigger of the three had trouble. He rolls in a manner unique to him. Others, not wanting to get too dizzy trying summersaults, drew inspiration from him. Soon all three are rolling badly in the vague direction of where they had been commanded to head but their form is lousy and their style is sloppy.

The boys are reprimanded for their bad technique, and the Officer demonstrates how a well-disciplined body does somersaults – cleanly, neatly, and highly practiced. However,

his trajectory is not thought through and on the second tumble the commanding officer of the camp finds himself landing on his back in a thorn bush. He is in pain. He is enraged. He leaps up and grabs his rifle—with full intention of shooting the youth.

The Officer’s highly practiced routine has failed him – the unique and sloppy summersaults unintentionally performed by the boys give them the upper hand. The boys run into the jungle and are once again safe.

The comic’s juxtaposition of the humorous – unruly – summersault with the seriousness of its potential outcome performs what Dasgupta (Citation2019) reads in the refugee film Fuocammare, setting the reader on a voyage that traverses micro and macro entanglements: ‘ranging from the mundane to the fatal’ (2019, 115). The everyday storytelling present in the comic is also a clear example of the counter-memorial aesthetic that Tello (Citation2016) identifies as contemporaneity, that is, being in time, rather than thinking as past or future, constructing both but never fully dwelling in either. This technique, surfaces as it does through diasporic intimations, may well prove a powerful pathway for rethinking migrant studies more broadly; namely, rupture as a mode can be used to actively deconstruct the way racialization attempts to back migrants and refugees into representative corners or binary positionalities. These ruptures, or diasporic intimacies, need not be on a macro scale, ‘not majoritarian, not the god’s eye view of the old cosmo, but instead comprise the stammering pedagogies, the minoritarian interjections that disrupt the business as usual of certain forms of globalization’ (Gunew Citation2017, 52).

Conclusion

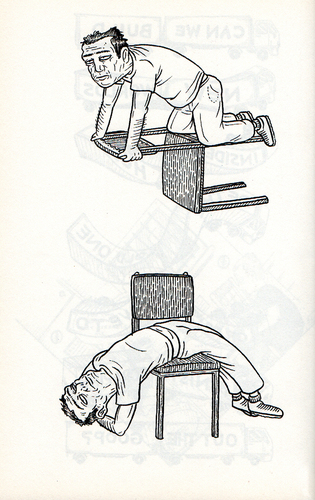

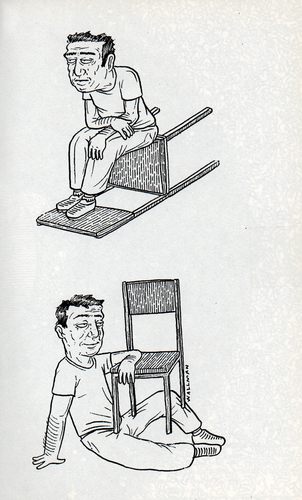

The comic starts to show us how the body always manipulates the material and discursive constraints it is within. As Sam Wallman’s (2015) drawings of a detainee and a chair (inspired by visits to Broadmeadows Immigration Centre in 2012 and 2014) illustrate: the body adapts, invents, and survives. This becomes a creative strategy for displacing the moving histories of racialized accumulation that migrants and refugees often carry. Comics and zines can help one get out of one’s body and return to it in a more livable way, but not to smooth over temporal and spatial fissures – how can they be smoothed over if one still feels they are in the middle of them? Rather, these texts re-channel the kinetic force of rupture, the ongoing experience of moving elsewhere, thereby deflecting the full arrival of a racialized materiality. There is space here. Perhaps, then, it is through the framework of rupture that migrant studies can also trace the various, moving legacies of migration that build over time, intersecting and implicating bodies in contemporary life, and yet, find space.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the GASt (Gesellschaft für Australienstudien/German Association for Australian Studies) for providing a travel bursary to attend their Biennial Conference Australian Perspectives on Migration in October 2018, where a draft version of this paper was presented for feedback. My sincere thanks to the blind peer reviewers of the paper who offered very thoughtful and useful advice to sharpen the work. And of course: to the artists and activists featured within, for the vital work you do.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. I have chosen to use the word refugee throughout the paper, even though many of the authors of these works still have not been officially deemed to be refugees, remaining ‘asylum seekers’, ‘illegal immigrants’, or worse: ‘boat people’.

References

- Accident: A Story of Entrapment. 2015. A Comic by Michael Fikaris and Osme in Where Do I Belong? In A Silent Army Print Concern, edited by M. Fikaris, S. Ahmed and S. Wallman. Australia: Silent Army and Refugee Art Project.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2007. “A Phenomenology of Whiteness.” Feminist Theory 8 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1177/1464700107078139.

- Ahmed, Safdar. 2015. Islamophobia: Night of the Muslim Zombies, an Art Series and Essay. Sydney: zine produced for Other Worlds Zine Fair.

- Ahmed, Safdar. 2020. “Zines from the Refugee Art Project.” In Museum of Australian Democracy, edited by. S. van Egmond. Old Parliament House. URL https://www.moadoph.gov.au/blog/zines-from-the-refugee-art-project/?fbclid=IwAR01QRKlGuhj3c9b0IpXedIdXknLNsxNIlspZ2ECNGvX2kzN6-i0qJQuegM#

- Ahmed, Safdar. 2021. “Why Comics? Australian Comics and the Autographic Turn.” Folio: Stories of Contemporary Australian Comics, 9 December, https://www.foliocomics.com/australian-comics-essays-2021/why-comics-australian-comics-and-the-autographic-turn-by-safdar-ahmed?fbclid=IwAR1w5cXd5GlCwkuW0KM7K11pgRrQVBtcfMPs09x-F44DkqnEERY7urWHK6s

- Ali, Soraya. 2022. “Ukraine: Why so Many African and Indian Students Were in the Country.” BBC World News. 4 March 2022. URL: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-60603226

- Al-Saji, A. 2009. “An Absence That Counts in the World: Merleau-Ponty’s Later Philosophy of Time in Light of Bernet’s “Einleitung”.” Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 40(2), 207–227.

- Boym, Svetlana. 1998. “On Diasporic Intimacy: Ila Kabakov’sinstallations and Immigrant Homes.” Critical Inquiry 24 (2): 498–524. Intimacy (Winter 1998). doi:10.1086/448882.

- Boym, Svetlana. 2007. “Nostalgia and Its Discontents.” The Hedgehog Review 7 (Summer 2007): 7–18.

- Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton and Oxford UK: Princeton University Press.

- Chow, Rey. 2014. Not Like a Native Speaker: On Languaging as a Postcolonial Speaker. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chute, Hillary. 2008. “The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36 (1–2): 92–110. doi:10.1353/wsq.0.0023.

- Dasgupta, Sudeep. 2019. “Fuocoammare and the Aesthetic Rendition of the Relational Experience of Migration.” In Handbook of Art and Global Migration: Theories, Practices and Challenges, edited by B. Dogramaci and B. Mersmann, 102–116. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Douglas, Kate, and Anna Poletti 2016. “Zine Culture: A Youth Intimate Public”. In Life Narratives and Youth Culture: Representation, Agency and Participation, Palgrave, UK. 10.1057/978-1-137-55117-1_7

- Fiske, Lucy. 2016. Human Rights, Refugee Protest and Immigration Detention. Palgrave Macmillan. URL https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/122461

- Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of sexuality, 1: An Introduction, Trans. R. Hurley. London: Penguin.

- Ganguly-Scrase, Ruchira, and Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt. 2016. “Dispossession, Placelessness, Home and Belonging: An Outline of a Research Agenda.” In Rethinking Displacement: Asia Pacific Perspectives, edited by R. Ganguly-Scrase and K. Lahiri-Dutt, 3–29. London: Routledge.

- Gunew, Sneja. 2009. “Between Auto/Biography and Theory: Can ‘Ethnic abjects’ Write Theory?” Comparative Literature Studies 42 (4): 363–378. doi:10.1353/cls.2006.0020.

- Gunew, Sneja. 2017. Post-Multicultural Writers as Neo-Cosmopolitan Mediators. London: Anthem Press.

- Hage, Ghassan. 2014. What is a Critical Anthropology of Diaspora? Paper presented to Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne, 2 April.

- Hedge, Radha. 2016. Mediating Migration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Khadem, Amir. 2017. “Framed Memories: The Politics of Recollection in Mana Neyestani’s An Iranian Metamorphosis.” Iranian Studies 51 (3): 479–497. doi:10.1080/00210862.2017.1338400.

- Morrice, Linda. 2022. “Will the War in Ukraine Be a Pivotal Moment for Refugee Education in Europe?” International Journal of Lifelong Education 41 (3): 251–256. doi:10.1080/02601370.2022.2079260.

- Motta, Sara. 2016. “The Coloniality of Knowing: From Identity Politics to a Politics of Integral Liberation.” Crossroads in Cultural Studies Conference 14-17 December, 14 December, Sydney.

- Mr Man from the Garden: A Refugee Art Project Children’s Book. Western Sydney: Refugee Art Project Women’s Art Workshop, Pop Up Parramatta Artists Studio.

- Mills, C. 2014. “White Time: The Chronic Injustice of Ideal Theory.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 11 (1), 27–42.

- Nail, Thomas. 2015. The Figure of the Migrant. PLACE: Stanford University Press.

- Ngo, Helen. 2019. “‘Get Over It?’ Racialised Temporalities and Bodily Orientations in Time.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 40 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1080/07256868.2019.1577231.

- O’brien, Michel. 2019. “Reanimating Vietnamese Australian Diasporas Through Digital Autographics: The Work of Lê Văn Tài.” Antipodes 33 (2): 298–314. doi:10.13110/antipodes.33.2.0298.

- Ong, Aihwa. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

- Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2000. The Turbulence of Migration: Globalization, Derritorialization and Hybridity. Cambridge UK: Polity.

- Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2012. Cosmpolitanism and Culture. Cambridge UK: Polity.

- Papastergiadis, Nikos, and Daniella Trimboli. 2019. “From Global Turbulene to Spaces of Conviviality: The potentialities of Art in Mobile Worlds.” In Handbook of Art and Global Migration: Theories, Practices and Challenges, edited by B. Dogramaci and B. Mersmann, 38–53. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Perera, Suvendrini, and Joseph Pugliese. 2018. “Between Spectacle and Secret: The Politics of Non-Visibility and the Performance of Incompletion.” In In Visualising Human Rights, edited by J. Lydon, 85–100. Place: UWA Publishing.

- Poletti, Anna. 2008. “Auto/Assemblage: Reading the Zine.” Biography 31 (1): 85–102. doi:10.1353/bio.0.0008.

- Remeikis, Amy. 2017. “Pauline Hanson Says Islam is a Disease Australia Needs to ‘Vaccinate.’” Sydney Morning Herald, 24 March, URL: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/pauline-hanson-says-islam-is-a-disease-australia-needs-to-vaccinate-20170324-gv5w7z.html

- Rifkind, Candida. 2017. “Refugee Comics and Migrant Topographies’.” Auto/Biography Studies 32 (3): 648–654. doi:10.1080/08989575.2017.1339468.

- Robbins, Joel. 2013. “Beyond the Suffering Subject: Toward an Anthropology of the Good.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19 (3): 447–462. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.12044.

- Robertson, Shanthi, Anita Harrris, and Loretta Baldassar. 2017. “Mobile Transitions: A Conceptual Framework for Researching a Generation on the Move.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (2): 203–217. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1362101.

- Sleep Cycle in Villawood, 2015, a Comic Strip by Alway, Talha, and Zeina. Sydney: Refugee Art Project.

- Spivak, Gayatri. 2012. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Suliman, Samid. 2017. “Mobilising a Theory of Kinetic Politics.” Mobilities 13 (2): 276–290. doi:10.1080/17450101.2017.1410367.

- Tello, Veronica. 2016. Counter-Memorial Aesthetics: Refugee Histories and the Politics of Contemporary Art. London & New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Trimboli, Daniella. 2020. Mediating Multiculturalism: Digital Storytelling and the Everyday Ethnic. New York, London, and Delhi: Anthem Press.

- Wallman, Sam. 2015. Untitled. In A Silent Army Print Concern, edited by M. Fikaris, S. Ahmed and S. Wallman. Australia: Silent Army and Refugee Art Project.

- West, Paige. 2018. “Dispossession and Disappearance in the Post Sovereign Pacific: The Regional Resettlement Agreement Between Australia and Papua New Guinea, an Ethnography of Loss.” ADI Occasional Lecture, Deakin University, Melbourne, 17 May.

- Whitlock, Gillian. 2006. “Autographics: The Seeing ‘I’ of the Comics.” Modern Fiction Studies 52 (4): 965–979. doi:10.1353/mfs.2007.0013.

- Whitlock, Gillian. 2015. “The Hospitality of Cyberspace: Mobilizing Asylum Seeker Testimony Online.” Biography 38 (2): 245–266. doi:10.1353/bio.2015.0025.

- Whitlock, Gillian, and Anna Poletti. 2008. “Self-Regarding Art.” Biography 31 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1353/bio.0.0004.