ABSTRACT

Book publicists are important intermediaries in generating earned media attention, creating discoverability opportunities, and getting new books into the hands of potential readers. Despite their important function in book culture, publicists’ labour in producing and framing value in the book industry is often rendered invisible in the industry and scholarly literature, which we trace back to field-defining conceptual models, particularly Robert Darnton’s Communications Circuit (1982). This article draws on interviews with eight Australian publicists to make visible, interrogate, and explain the material and symbolic labour involved in the affective relationship-building and cultural framing work of publicity. This article explores publicists’ day-to-day work, their relationships with authors, colleagues and the media, and publicity’s function in contemporary book culture. Book publicists are important cultural intermediaries: they are integral to the economic and social contexts of publishing, and influence and shape cultural tastes and value through strategic promotional work, resulting in considerable effects across the domains of production and reception.

Introduction

In March 2020, Affirm Press, a small independent publishing house in Melbourne, Australia, published Pip Williams’ The Dictionary of Lost Words. This historical fiction novel by a debut author about a girl who collects slips of words misplaced, discarded or neglected by the men compiling the first Oxford English Dictionary, could have been lost amongst the abundance of new books published and marketed each year and the overwhelming worldwide news coverage of Covid-19. Instead, it is one of the lucky few debut novels that has achieved tremendous success. The sixth bestselling fiction book in Australia in 2020 (Books+Publishing, 17 March 2021), by May 2022 it had sold more than 200,000 copies in Australia and New Zealand. It won several awards between 2020–2021 (including Adelaide Writers’ Week MUD Literary Prize, the People’s Choice Award at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, and the Australian Book Industry Award for General Fiction Book of the Year) and received positive reviews in many Australian newspapers. It was featured on ABC Radio National’s The Book Show, and had endorsements from bestselling authors including Geraldine Brooks and Tom Kenneally. Internationally, according to the Affirm website, The Dictionary of Lost Words has been sold into 17 territories and was the Reese’s Book Club pick in May 2022. This success was achieved despite Williams not being on social media and, due to the pandemic and subsequent travel restrictions across Australia and the world, no in-person promotional events in its debut year.

As with other high-selling titles, success was produced through ‘profitable interactions’ and ‘affective connections’ between the author, publisher, professional critics, and readers across digital platforms, media organizations, and public institutions (Parnell and Driscoll Citation2021, 1). Cultural intermediaries, including reviewers, prize judges and festivals organizers, remain highly influential as agents of consecration in building reputation in contemporary book culture (Dane Citation2020). More intangible forces, including hype (Thompson Citation2012) and buzz (Driscoll and Squires Citation2020) also kindle success. Successful outcomes are largely the result of promotional work by marketing and publicity teams that tend to work closely together, sometimes with overlap, on promotional campaigns.

Publicity is typically positioned as an activity under the marketing umbrella. In Marketing Literature, Claire Squires (Citation2007, 2) adopts a ‘catholic’ definition of marketing that encompasses both specific activities as well as processes of representation and interpretation. Marketing, she poses, ‘includes the acts of a publisher’s marketing and press departments: for example, the production of point of sale (POS) materials, advertising, reading events and publicity campaigns’ as well as ‘the decisions publishers make in terms of the presentation of books to the marketplace, in terms of formats, cover designs and blurbs, and imprint.’ These activities, performed by marketers, publicists, publishers, editors and, increasingly, authors, share a commercial goal, not only to sell books but, in Squires’ words, to do with ‘the creation and construction of audiences for a book’ (Squires Citation2007, 65). While some of these activities are very clearly delineated under specific positions, the organizational adjacency of marketing and publicity departments has often led to a conflation of the two roles.

An important distinction between marketing and publicity professionals in publishing houses is the kind of media they work with; marketers work with owned and paid media (such as advertisements and social media), while publicists are responsible for gaining earned media (e.g. obtaining reviews and radio and TV interviews) (Margolis Citation1985). Baverstock and Bowen describe this latter kind of coverage in the media as ‘free advertising’ (Baverstock and Bowen Citation2019, 247), though the time of the publicist who organizes these opportunities is certainly not free. Another distinction is the kind of labour publicists perform; publicists also tend to work more closely with authors, building individual brands and providing author care (Dane, Weber, and Parnell Citation2023; Parnell, Dane, and Weber Citation2020). While book marketing has been explored in detail (see Greco Citation2013; Nolan and Dane Citation2018; Noorda Citation2019; Squires Citation2007), publicity and the labour of publicists have yet to be explored empirically.

The few mentions of publicity in literature focus on specific activities rather than the nature of how publicity shapes books’ circulation and mediation. Albert Greco (Citation2013, 196), for example, briefly describes the kind of administrative work a ‘promotion manager’ may perform for an author who experiences ‘uneven hotel accommodations, late flights to distant cities, and enchanted radio and television personalities eager to book her for the next time she writes a book.’ While these activities allude to publicists’ affective work, this description positions the publicist solely as a passive envoy between publishing houses, authors and the media. Exploring publicists’ role exclusively in relation to reviewers and review outlets, Clayton Childress shows how publicists ‘translate’ the merits of a book from the perspective of publishing insiders (the extra-textual information such as whether it is a lead title or that editors love it) to selling points for consumers (the textual information such as plot, character and emotive reactions) (Childress Citation2017, 170, emphasis in original). There is also a chapter dedicated to publicity and PR in the guide How to Market Books, which offers advice to prospective publishing professionals (Baverstock and Bowen Citation2019). Publicists’ broader role in producing and framing value, and the intricacies of their public-facing promotional and intermediary work, are in each of these instances largely rendered invisible.

We trace a lack of recognition of publicity back to field-defining conceptual models, in particular Darnton’s (Citation1982), which focuses on explicating the movement of ideas between individuals through the manufacture and circulation of physical books, but locates ‘publicity’ and the ‘social and economic conjuncture’ in hazy conceptual spheres of influence, with no explicit connection to any other agent in the circuit. Our goal is to zoom in on, interrogate, and explain the specific processes and relationships that shape books’ movement and reception once the process of manufacture is complete, and we do this by focussing on the labour of book publicists in this space. While we acknowledge that marketing professionals also operate in this space, examining marketing activities and labour is outside the scope of this article. We base our research on in-depth interviews with eight publicists working in a range of Australian publishing houses, focusing in particular on adult trade fiction and non-fiction and educational publishing. This article explores the overall and day-to-day work of publicists, their relationships with authors, colleagues and the media, and the function of publicity in contemporary book culture. We argue that publicists operate as important cultural intermediaries, influencing and shaping cultural tastes through strategic promotional work alongside other industry agents.

Locating the publicist in the publishing process

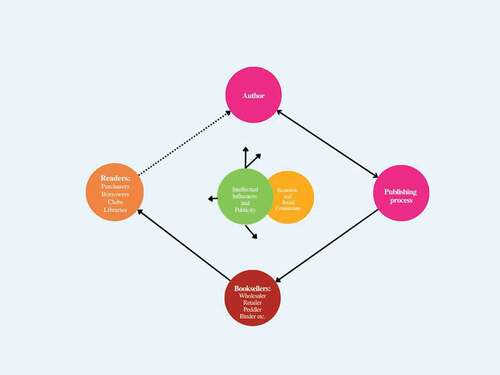

The labour of producing a book has been most influentially described in publishing studies by Darnton’s (Citation1982), reproduced at . Darnton’s circuit follows a book through the different stages of its lifecycle: conception, acquisition, production, circulation, and reception. Each of these stages is framed as the labour of specific individuals, guarding against Darnton’s concern that ‘[m]odels have a way of freezing human beings out of history’ (Darnton Citation1982, 69). The book moves through the hands of the author, publisher, printers, shippers, booksellers (and other associated workers), and readers. In addition, Darnton’s circuit includes an ‘economic and social conjuncture’ which influences publishing, and is associated with ‘intellectual influences and publicity’ and ‘political and legal sanctions’, but does not explicate these influences on the communications circuit further or assign them to human labour.

Figure 1. The Communications Circuit, Darnton (Citation1982).

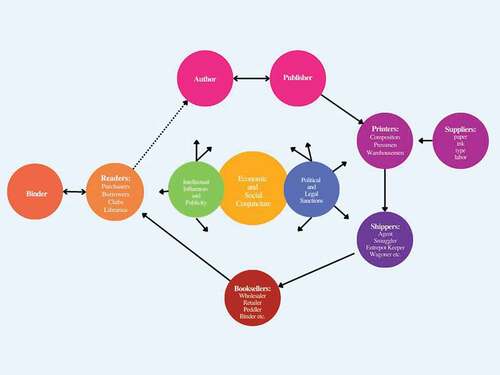

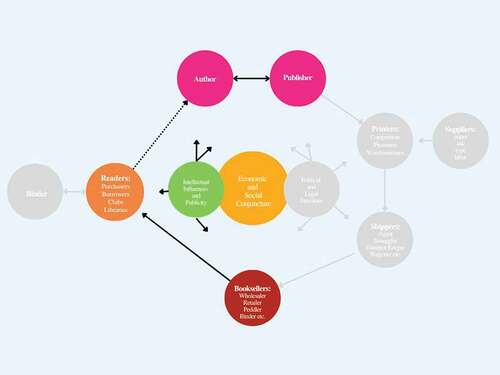

Multiple scholars have updated components of the circuit, most notably Padmini Murray and Squires (Citation2013), who brought it into the 21st century with modifications for digital publishing, self-publishing, contemporary changes to print publishing, and further development of the reader’s role. Again, however, the economic and social conjuncture remains apparently undisturbed. It is in this space, and specifically in the sphere of ‘intellectual influences and publicity’, that we locate our analysis.Footnote1 We illustrate this in , which highlights the components relevant to this article; shows a simplified version, collapsing the work of printers, suppliers, and shippers alongside that of publishers into ‘publishing process’.

Figure 2. The ‘economic and social conjuncture’ of Darnton’s (Citation1982).

The aim of this article is to illustrate in more detail how the publicity function intervenes in the transition from the book out of Darnton’s warehouses and waggons, onto bookstore shelves, and into readers’ hands as well as the vital labour that contributes to the book’s passage around the circuit. While many industry agents contribute to readers discovering and buying books, including marketers, booksellers, influencers, and authors themselves (all of which publicists work alongside at different times, publicity is a crucial intermediary in this process.

The publicist as a cultural intermediary

In exploring the humanness in the overlapping circles of ‘intellectual influences and publicity’ and ‘social and economic conjuncture’, we conceptualize the publicist as a cultural intermediary (Edwards Citation2012; Surma and Daymon Citation2013), facilitating not only the movement of ideas and cultural products from one sector to another, but also ultimately influencing that nature and profile of cultural tastes. In one sense, we might see the publicist operating in this fashion as an envoy for the publisher, taking the book to the media and to other literary institutions, who subsequently frame or translate the book and the author for the reading public. This representation of the role of the publicist is consistent with most of the scholarly attention paid to publicists’ labour thus far, which focuses on publicity as an outcome rather than a function (see Parnell, Dane, and Weber Citation2020).

Moving forward, however, we highlight the limitations of this conceptualization for explicating the work that publicists do as cultural intermediaries: not only as publisher envoys, but also comprehending substantial affective relationship-building and cultural framing work. The overlapping circles that provide vague context to Darnton’s circuit suggest that there is a direct and productive relationship between publicists and the social and economic environment within which books are produced and consumed. We see this idea as directly according with a theorization of publicists as cultural intermediaries who, through their work, are afforded the opportunity to ‘contribute to the shaping of … attitudes, opinions and consumption patterns’ (Surma and Daymon Citation2013, 50). We can see the power of publicists as cultural intermediaries in the example of Pip Williams and The Dictionary of Lost Words that opened this article; in the absence of an authorial social media presence (on which many publishers increasingly rely as part of marketing plans), and in the context of adult trade fiction (which does not have a strong social media community of Bookstagrammers and BookTokers to generate digital word-of-mouth), publicity work was foundational to how this book was framed, understood and taken up by the media and readers, undoubtedly contributing to both its symbolic and economic success.

Examining publicists’ location within Darnton’s model also offers insights into the influence of publicists and their work, and where the impact of this is felt. Arrows from the circle ‘intellectual influences and publicity’ are directed at authors, publishers, readers and booksellers, indicating how publicists frame books and authors to the media and other literary institutions has a generative effect on publishing production as well as reception. Unlike marketing, which targets readers directly through social media, advertisements and product placements, the work of publicists is primarily directed at other cultural intermediaries, such as journalists, reviewers, festival organizers, prize judges, and booksellers, which Squires describes as opinion formers or leaders; people ‘in a position of privileged authority, with an advantaged capacity for communicating the book to other potential readers’ (Squires Citation2007, 65). These mediators are leaders ‘in word-of-mouth recommendation and hence influential in “shaping reading habits” and, moreover, of constructing meanings that are then affirmed or contested by readers’ (Squires Citation2007, 66); a process which begins with the publicist choosing relevant outlets, programs, prizes, and so on to pitch as well as deciding what points of the book or author to emphasize in their pitches. This generative effect and the work publicists perform are typically classified in association with the commercial activities of publishing, placing them separate from the creatively productive work held in high regard in the sector.

The tension between cultural and commercial imperatives is a defining feature of much of book publishing: an uneasy relationship between making books for their own sake, and doing so within a capitalist framework that necessitates profitability and thus promotion. Within publishing studies, this tension is well-trodden ground. What is important to highlight here is that publishing as an industry has been shaped by both cultural and commercial imperatives, and by an uneasiness about these imperatives’ coexistence. In Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption, Laura Miller describes book professionals’ outcries against commercializing developments throughout the twentieth century: mergers and acquisitions, agents, book clubs. The book industry, Miller argues, subscribes to the notion that

… hucksterism, greed, ruthless competition, and obsequence to the ‘mass’ market should simply not be associated with something as valuable to society as are books. As the potential for profit making in bookselling has expanded, it is therefore not surprising that this sector has become a focal point for debates about commercialism.

Per Miller, this perception is not only held by industry insiders, but is part of public understandings, both popular and academic, that cultural and economic interests are at odds with one another. However, more critical perspectives foreground ‘how commercialization affects the status and power of cultural authorities’ (Miller Citation2006, 7).

In the context of commercial publishing houses – the dominant business model since the beginning of conglomerate publishing in the early 1970s and the environment within which all our participants work – differentiating aesthetic and commercial values is tricky; work traditionally positioned as aesthetic, such as acquisitions and editing, is increasingly market-focused. As Clayton Childress shows in his research into how acquisition editors use BookScan sales data, while ‘acquisition editors still rely on their personal tastes and enthusiasm when selecting manuscripts, they must make the case for the works that they select, and negotiate their values in meetings with other editors and staff from marketing, publicity and sales departments’ (Childress Citation2012, 608). Claire Squires likewise shows how sales data is often by editors to support their ‘gut decisions’ rather than inform them (Childress Citation2017). Taking acquisition editors in contradistinction to publicists, we can see how different cultural intermediaries in the same cultural context are invested to varying degrees in different value schemes that ‘continue to rest on juxtapositions of elite and popular, restricted and mass, artistic and commercial’ Maguire and Matthews (Citation2012), 557).

We must also acknowledge how values that are associated with non-commercial legitimacy (elite, restricted, artistic) are contextualized by the neoliberal, conglomerate structures of the contemporary global publishing industry. To borrow an argument by Smith Maguire and Matthews, acquisition editors, publicists and other cultural intermediaries in the publishing industry are differentiated by their location within a commodity chain; ‘Considering cultural intermediaries as contextualized market actors … requires a sensitivity to markets and value as pragmatic accomplishments, and regards context as constitutive of agency, not as an external determinant of action’ (Maguire and Matthews Citation2012, 552). Most publishing activity, and certainly the kind of publishing with which our participants are engaged, is commercial. This context does not preclude other kinds of value, such as the development of national cultural identities through literature, for example (Day and Mannion Citation2017), but undoubtedly shapes the kind of value publicists contribute to literary culture, and its significance.

These structures of value that shape the industry contextualize the labour performed by book publicists, and how and why this labour has historically been overlooked and devalued. Characterising publicists solely as envoys for the publishing house – rather than as cultural intermediaries integral to the economic and social contexts of book publishing – effectively leans into these fears of commercialization (and its implicit power to depreciate cultural value), and thereby ensures the imaginary boundary between commercial and cultural aspects of publishing remains guarded.

Drawing on Edwards (Citation2012) and Surma and Daymon (Citation2013), we seek to illuminate the opaque parts of Darnton’s circuit to define the labour of publicists as cultural intermediaries. This approach highlights both the symbolic influence of the publicist on public literary tastes, and the specialized labour that underpins this work. In discussing publishing economics, vocational expectations and professional relationships, we examine the strategic work publicists perform, and illustrate how publicists, as cultural intermediaries, undertake material and symbolic labour that shapes cultural tastes. This work exists in a broad and expansive literary ecosystem and operates in tandem with the work of marketers, booksellers, influencers, reviewers, authors, and others. This article analyses in-depth, semi-structured interviews with eight publicists working at Australian publishing houses. Previously, we have hypothesized that the working conditions publicists faced contributed to their higher risk of workplace sexual harassment (Books+Publishing, 12 December 2017; The Bookseller, 10 November 2017; Parnell, Dane, and Weber Citation2020). In response, publicists were invited to participate in this research with the promise of confidentiality to protect participants who work in an occupation with a small population in Australia and who may disclose negative experiences associated with their work, further contributing to their precarity. Thus the specifics of their work, including titles on which they worked, are omitted from this analysis in the interest of ensuring anonymity. The sample, designated as P01-P08, comprised publicists working in large multinational, mid-size and small independent publishing houses, across trade and educational publishing. Interviews were conducted via Zoom in late 2020 and early 2021, and lasted approximately an hour. Transcripts were coded using thematic analysis, with a focus on specific work tasks, social aspects of the role, and working environments and conditions.

In the following section we analyse book publicists’ discussions of their work to theorize book publicists as cultural intermediaries. We begin with the paradigm that has been associated with publicists’ labour in their cursory treatment in existing book industry research, and that in its simplification best fits the circuit model of production, circulation and consumption: the publicist as envoy between publisher and media. We then focus on the less visible, more tacit components of publicists’ roles. We look at the strategic decision-making – the applied knowledge of multiple cultural and media spaces – that publicists develop and deploy in their work, and the substantial affective labour that goes into building and maintaining media relationships. We consider the complexities of publicists’ relationship to authors, too, and the way that this inflects both how they work and how they are perceived to work on behalf of the publisher. Lastly, we zoom out and consider the way that different publishing houses are positioned in relation to the structuring commercial and cultural tensions of the book industry, and discuss how this affects publicists’ work practices as well.

The publicist as envoy

Publicists work in the liminal space between the fields of production and reception, undertaking a range of tasks, sometimes concurrently, to gain media attention for books. When describing her role in simple terms, P03, who works at a medium-sized independent publishing house, states ‘if you’re seeing a review in a newspaper or an interview on TV or you’re hearing an interview on the radio with an author, then that’s something that’s been set up by the publicist.’ The goal of publicity, as this quote infers, is simple: to ‘get media’ (P07) and ‘as much PR as I possibly can’ (P03) for a title and author in order to increase chances for discoverability and awareness, and sales. A central part of the work of publicists is pitching media and other cultural intermediaries to obtain reviews, interviews, and event spots. This work leads to many other kinds of quotidian labour, such as sending out books to reviewers along with other promotional materials, accompanying authors on book tours and to media appearances, and organizing, scheduling and managing events. In this way, the work involves campaign planning, ‘a weird combination of kind of really timely administration … and also being required to be present for events and tours or, you know, like the things that are actually happening in real time’ (P07). This sample of material, seemingly straightforward, and relatively visible tasks does little to describe the highly strategic manner in which publicists undertake this work or its impact in creating, shaping and communicating cultural tastes.

Beyond the envoy: strategic decision making and affective labour

Shifting the perspective from transmitting information from the publishing sector to the media to producing value between the two spaces highlights the strategic knowledge work of publicity. Interviews with participants revealed the multi-layered strategic thinking that informs this translation work, which involves complex understandings of the media ecosystem together with the affective labour of building and maintaining productive relationships. P04 describes the work as ‘positioning’ across different media spheres such as events, broadcast media and print, and explains the complexity involved in this process:

I do put a lot of time into figuring out like, where I’m going to pitch things. And sometimes I think it hinders me, because I get overly worried about like, whether something’s targeted or not, but and sometimes, like, depending on what it is, it’s just, like, get [it] out to as many people as possible, but … I’ve had much better luck with the process of like, actually figuring out exactly who needs this book.

The process of developing a targeted pitch strategy for a book involves a deep and multifaceted understanding of both the producers and the consumers of particular media content. ‘Who needs this book’, as P04 notes, is a clear driving factor in a strategic media campaign, which involves a deep understanding of market tastes and a developed network of relationships with journalists and media producers, as well as a clear articulation as to why particular audiences might be interested in the book in question. These skills are increasingly important as competition for earned media coverage becomes more fierce; book coverage in Australian newspapers, for instance, reduced by more than a third between 2013–2017 (Nolan and Ricketson Citation2019).

In developing and maintaining relationships with the media, publicists are framing both the book that is the focus of the publicity campaign, as well as the publishing house that produced the title. In this way, the publicist is involved in framing or positioning two entities simultaneously. P07 spoke of how it is not just personal but also contextual relationships with journalists that help to build successful publicity campaigns. They stated that maintaining good media relationships involves ‘making sure that your book is something that they’re interested in’ (P07). They go on to explain that:

I think kind of over the years, it’s probably not so much the personal relationships I’ve developed with journalists, it’s that they have got a sense of the kind of books that [our house] publish[es], and they know that they suit their outlet. So I would say that’s more the reputation of the publisher, rather than me doing any kind of, wining and dining or kind of nourishing relationship.

Publicists shape how journalists and media producers understand the reputation of the publisher and the kinds of books they publish through the ways in which they translate value between these spaces. The intricacies of the way publicists frame or package information for each media outlet, which over time builds upon itself (alongside strategic list-building by the publisher) to establish the reputation that P07 describes, draws upon contextual knowledges of multiple spaces, practices and individuals. P03 explained the importance of these knowledges for current and future campaigns, saying ‘if you just start pitching to places that are not going to cover it, you make yourself look like such an idiot, and then they’re going to ignore your emails … and you have to be really conscious of that … ’ This highlights the ways in which publicists are working with multiple, sometimes competing, interests that stretch across multiple campaigns.

P03 also encapsulated the complexity of managing a book’s media campaign and the simultaneous strategic affective relationship management that exists as a constant in their work. They spoke of an instance where they were reprimanded by a producer at a morning television program on ‘[Network A]’ for pitching to and promoting a book on a similar program on a different network (Network B), citing Network A’s higher viewership. In order to maintain the relationship with the producer and Network A, P03 felt the need to explain the rationale for promoting the book with Network B to the producer:

I was just like, I had to then explain to her my process. I had to explain to her that I had secured [primetime program on Network C] to run first. I needed to then secure morning TV, which I did with [high-rating breakfast program on Network A]. I had then secured [Network C] and [Network A], so I wanted to get something on [Network B], and the last slot available to me was the morning slot rather than the breakfast slot, so I went with [morning program on Network B] over. [morning program on Network A]

A tension exists between the strategic goals of the publishing house and the goals of the media outlet, a tension that ultimately falls upon the publicist to navigate as they work to maintain long-term relationships with the media outlet and producers. P03 spoke about another instance of affective manoeuvring to preserve relationships with the media. P03 did not discuss exclusivity for an excerpt of an upcoming book, despite the fact that the journalist/publication appeared to expect it. While the responsibility of securing exclusivity lies with both the journalist and publicist, in order to maintain a positive working relationship, P03 assumed the blame for the oversight:

The journalist was furious at me and I just had to write back this really cringy email being like, ‘Oh my god, I’m so sorry. That is entirely my fault. It will never happen again. I’m usually so much better at this than I’ve been on this occasion. I was just really inundated with this campaign,’ blah, blah, blah. I didn’t want to send it, but knew I had to in order to maintain that relationship.

Here we can see the coming together of the strategic and the affective elements of publicists’ work as media campaign managers, and the quotidian complex negotiations that underpin this labour.

The strategic work involved in publicity is often hidden due to a confluence of factors. Successful publicity is designed to confer visibility onto authors and their books, rather than the people performing the work. As P07 describes, a skill of the job is ‘…landing the interview, the festival, spot, whatever, and making it look … completely magic.’ While editorial work is completely visible to authors as a collaborative process, oftentimes the extent of labour publicists perform in achieving media attention is necessarily hidden in the interest of managing the author’s feelings and morale. This concealment, in turn, results in a lack of understanding about the process of obtaining media. As P07 stated:

So everything you present [authors] with, it’s almost like you were invisible … as if the journalist just came to us … we would never tell them how much work it was to get [the media’s] attention and to present it to them in a way that they wanted to do [the review]. So all that work is always kind of hidden from the author.

While the work involved in unsuccessful pitches and securing successful ones may be made visible to colleagues or managers, recorded in spreadsheets and email servers, its obfuscation to authors falls under author care work (Parnell, Dane, and Weber Citation2020). Publicists balance the requirements of highly strategic campaign planning and relationship management with media professionals to ensure its execution with an equally important part of their job in managing the publisher’s relationship with authors. In doing so, publicists work at the intersection of multiple entities: they work with authors to promote their books, media professionals to generate opportunities for visibility, and publishers to achieve strategic goals.

Negotiating labour environments and the broader publishing landscape

Our findings thus far demonstrate that the publicist’s labour should be modelled, not only as that of an envoy, brokering the movement of cultural goods between different spaces in a transactional manner, but also as that of a strategic operative. The publicist is required to attain and strategically draw on significant understanding of the bigger picture of both the cultural field of book production and the broader media landscape in order to maximize the visibility of a title, and in order to successfully perform their role they also need to draw on substantial social and affective competencies in their interactions with authors and media alike. Our final observation is that the role of the publicist is also impacted by and demands strategic understanding of the position of the publishing house itself within the cultural field of book production. Factors like the publisher’s prestige, size, relationship to multinational houses, and explicit internal policies, play out in material ways for our interviewees, including in their navigation of acquisitions processes, in different front- and back-listing cultures within specific publishing houses, and also reveal themselves in the way that publicists explicitly and tacitly reference the tensions between their publishers’ commercial and cultural imperatives.

At some publishing houses, publicists are involved in the entire publishing pipeline, attending acquisitions meetings and engaging in strategic decision-making alongside other publishing staff, while at others they have little input until they are handed campaigns. P04, working at a medium-sized independent, is expected to ‘read for acquisition and go to acquisitions meetings, as well.’ This involvement leads to greater knowledge of the list, and a degree of control over the relationship with the author: ‘I’m involved in, like, a lot of author acquisition meetings and having to sort of be like, yeah, this is what your campaign is going to be like. Which I don’t think is, unlike, I don’t think it’s quite the same for a lot of publishers.’

P03 likewise compares the level of involvement in their previous role at a large multinational and current role at a medium-sized independent, observing that ‘at [multinational] I was involved in the acquisitions process, even as a communications assistant. Everyone was involved in the acquisitions process. At [independent], I am not.’ This involvement provided access to knowledge about the publisher’s strategic commercial decisions that in turn informed publicity:

At [multinational], I could understand the justification for publishing something, even if I hadn’t read it or even if I was questioning it. A big, I don’t know, big war book, why something like that would be a super lead. I would be like why the hell is this a super lead in my head, but having gone through the acquisitions process, I could understand that there was a very clear market for this, that previous war books similar had sold incredibly well, and that if we get this, this, this and this in terms of publicity or do this, this, this and this in terms of marketing, then we can have an amazing campaign and the book will fly off the shelves.

In this situation, we see a close, circular relationship at play between the major multinational publisher and the market. The market has determined the appetite for previous, similar books, which goes on to determine the allocation of resources by the publisher, which in turn heavily influences the market share of those titles going forward. Designating books as lead or super lead titles – those for which authors are usually paid higher advances – also influences how much publicity and marketing is budgeted for the title. Therefore, while the conception is that higher advances guarantee success for books, higher advances almost always guarantee more publicity and marketing efforts, which is a greater factor in determining success.

Different publishing houses also have vastly different approaches to front- and back-list titles. Continuing the comparison between their experiences at a major multinational and a mid-sized independent, P03 describes how, at the former they would work with one or two authors per month depending on books’ status as ‘super leads’ or ‘leads’, whereas at the latter they work with between 40 and 50 authors to varying degrees at any one time. P04 explains that their mid-size independent has a policy of never backlisting authors, which means that they may be ‘still doing bits and pieces for authors whose campaigns ran two years ago. And as well as managing the front list’, leading to them ‘in any given day […] working on bits and pieces for probably 15 to 20 authors’ despite an allocation of two to three frontlist titles per month. The publicist, in this instance, must make careful choices based on an understanding not only of the book and media industry’s symbolic structure, but also their temporal structure and explicit preference for novelty, with ‘authors who, whose campaign sort of ran, you know, six months or so ago’ in a particularly ‘tricky spot’, both in regards to the indeterminacy of their status as neither front- nor back-list, and the dwindling of resources as their campaign winds down. In turn, this places the publicist in a challenging position, where:

I feel like I can’t have that conversation with an author where I’m going […] ‘I think your campaign’s over now’, like, I don’t feel like I can say that to them. So I tend to sort of be like, things are winding down a little bit. If you want to keep the momentum going. Here are some things you can do. You can keep posting on socials. And some others don’t seem to care so much. And some are really stressed about it.

Indeed, it falls on the publicist to manage the actions, expectations and emotions of the author around their own campaign, in conjunction with the author’s perception of their campaign in relation to that of other authors at the same publishing house. P06 explains that, internally at a large multinational publishing house, ‘there’s sort of an expectation […] with the bigger, more important authors, you’re kind of there for them all the time’, but this can lead to issues when other authors perceive that they are getting different treatment. This hierarchy is not explained directly to authors:

No one tells the authors that they’re more important or less important, they might tell them that they’re very important because the book might be like the top fiction release of February. And so they’ll have the sense that it’s like a top title for [our house]. But then the other kind of less important authors will see all that stuff. Its … publicity is very visible. So they’ll be able to see what’s happening for other authors that you’re working with at the same time. And they will, they’ll text you and be like, why is this author getting to do bookshop visits all around Sydney, and where’s my bookshop visits?.

The publisher’s deliberate choice not to explicitly communicate authors’ relative prioritization within the company, while understandable, leads to expectation management issues that subsequently fall to the publicist to mitigate. This particular situation reveals the publicist’s positioning as a perceived gatekeeper for promotional opportunities, and also demonstrates how they work as a translator for the author of the author’s own position within both the publishing house and within the cultural field of book production.

Lastly, we see the position of the publishing house within the cultural field of book production revealed in publicists’ discussion of their publishers’ competing priorities. This was visible in our interviews with P07 and P05. P07 works for a small, independent publisher of literary fiction and serious non-fiction: titles often programmed at literary festivals and other face-to-face events. P07 describes how these events can ‘obviously increase sales’ as well as ‘creating an awareness for the author’, observing that ‘[t]hat’s the main business that we’re in, to sell books’. Immediately reflecting on the position that they have taken, however, this publicist cautions against a solely commercial interpretation of their motivations, and that of the author:

Often, it’s the time where people will come up and say, I really loved your book. And you know, it’s a memoir about whatever this happened to me as well in my past, and there’s some really kind of beautiful things that happen between authors and readers in events. That isn’t just the sales, it’s sort of I deny that something more just to the general experience of it and kind of bigger conversation.

P05 makes similar discursive manoeuvres, explicating the commercial nature of their publisher’s operations (‘at the end of the day, it’s about selling the books’), and then immediately restating the company’s commitment to educational outcomes:

Yes, all right, we exist to make money, but also our sort of ethical motivation as a business is to lift everyone up through education, really. […] So we are about making money, but we’re also about brand reputation and we’re very serious about that brand reputation and standing that we have in the sector and that responsibility to also nurture and give back. At the same time, that we’re making profit out of selling books, we are nurturing an educational industry. We’re facilitating research, facilitating knowledge and learning and all of that.

For both publicists, the labour they do in representing the interests of their respective publishing houses involve the careful negotiation of commingled commercial, cultural and ethical positions often seen as at odds with one another in the world of book publishing.

Conclusion

This article explicates the labour involved in publicity work and its function in the book sector. Through empirical investigation of the work practices of Australian publicists in the book publishing industry, we detail the spheres of ‘intellectual influences and publicity’ and ‘economic and social conjuncture’ in Darnton’s field-defining communication circuit model, and provide a framework for thinking about publicists as cultural intermediaries. This perspective highlights the material and symbolic labour publicists perform and the role they play in creating cultural tastes and value, and move beyond simplified understandings that position publicists as envoys responsible for conveying a book’s unique selling points. This work is structured by affective relationships with authors and media professionals as well as the cultural objectives and financial resources of publishing houses. It is also underpinned by publicists’ extensive multidisciplinary knowledge across book publishing, journalism and media production.

While none of our participants spoke of engaging directly with social media influencers such as Bookstagrammers or BookTokers, these professionalized readers are increasingly prominent cultural intermediaries with whom publicists engage. As Danielle Fuller and DeNel Rehberg Sedo argue (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo Citation2023, 45), book influencers ‘punch above their weight relative to the numbers of followers required for social and commercial success in other online recommendation cultures.’ Other, traditional cultural intermediaries such as prize judges and professional reader-critics in magazines and newspapers, remain important sources for book recommendations (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo). Therefore, while we have seen a shift in the popularity of some cultural intermediaries in recommendation culture – Fuller & Rehberg Sedo cite Oprah Winfrey’s book club being a popular site of readers discovering and choosing books in 2007; in 2020, she had been replaced by Reese Witherspoon, Emma Watson, and Jenna Bush – the essential role of connecting and framing books and their authors with the media and opinion leaders on which readers rely to discover books continues to be done by publicists.

As cultural work is increasingly delegated to algorithmic processes, as traced by Ted Striphas (Citation2015), how might the role of publicity change in future? Young adult, romance and other genre fiction, which have larger and more developed online publishing and reading communities, would likely prove productive sites for future research into how publicity work is adapting and developing in online contexts and in relation to non-traditional cultural intermediaries. There are, of course, other structural influences that impact on publicity work that also deserve further investigation, such as the lack of cultural diversity and inclusion in the publishing and media industries (Bowen and Driscoll Citation2022) that reinforces hegemonic ideas of value and taste cultures (Dane Citation2023), and how this might be reflected in and buttressed by promotional strategies.

Ethics for this project was obtained from the University of Melbourne. Project number: 2057515.1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. It is because we are primarily interested in expanding and developing this space of ‘intellectual influences and publicity’, and specifically because it remains untouched in the redeveloped versions, that we decided to work with the original circuit.

References

- Baverstock, Alison, and Susannah Bowen. 2019. How to Market Books. London: Routledge.

- Bowen, Susannah, and Beth Driscoll. 2022. Australian Publishing Industry Workforce Survey on Diversity and Inclusion. Melbourne: University of Melbourne and Australian Publishers Association.

- Childress, Clayton. 2012. “Decision-Making, Market Logic and the Rating Mindset: Negotiating BookScan in the Field of US Trade Publishing.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 15 (5): 604–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549412445757.

- Childress, Clayton. 2017. Under the Cover: The Creation, Production, and Reception of a Novel. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691160382.003.0001.

- Dane, Alexandra. 2020. Gender and Prestige in Literature. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49142-0.

- Dane, Alexandra. 2023. White Literary Taste Production in Contemporary Book Culture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dane, Alexandra, Millicent Weber, and Claire Parnell. 2023. “‘You’re too smart to be a publicist’: Perceptions, expectations and the labour of book publicity.” Media Culture & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437231188447.

- Darnton, Robert. 1982. “What is the History of Books?” Daedalus 111 (3): 65–83.

- Day, Katherine, and Aaron Mannion. 2017. “Publishing Means Business: An Introduction.” In Publishing Means Business edited by Mannion, Aaron, Weber, Millicent, Day, Katherine, vii –xi. Melbourne: Monash University Press.

- Driscoll, Beth, and Claire Squires. 2020. The Frankfurt Book Fair and Bestseller Business. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Edwards, Lee. 2012. “Exploring the Role of Public Relations as a Cultural Intermediary Occupation.” Cultural Sociology 6 (4): 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975512445428.

- Fuller, Danielle, and DeNel Rehberg Sedo. 2023. Reading Bestsellers: Recommendation Culture and the Multimodal Reader. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Greco, A. N. 2013. The Book Publishing Industry. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203834565.

- Maguire, Smith, and Julian Matthews. 2012. “Are We All Cultural Intermediaries Now? An Introduction to Cultural Intermediaries in Context.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 15 (5): 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549412445762.

- Margolis, Esther. 1985. “Trade-Book Publicity.” In The Business of Book Publishing, edited by Geiser, Elizabeth, Dolan, Arnold, Topkis, Gladys, 166–178. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Miller, Laura J. 2006. Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption. Reluctant Capitalists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Murray, Ray, and Claire Squires. 2013. “The Digital Publishing Communications Circuit.” Book 3 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1386/btwo.3.1.3_1.

- Nolan, Sybil, and Alexandra Dane. 2018. “A Sharper Conversation: Book Publishers’ Use of Social Media Marketing in the Age of the Algorithm.” Media International Australia 168 (1): 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X18783008.

- Nolan, Sybil, and Matthew Ricketson. 2019. “The Shrinking of Fairfax Media’s Books Pages: A Microstudy of Digital Disruption.” Australian Journalism Review 41 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajr.41.1.17_1.

- Noorda, Rachel L. 2019. “Borrowing Place Brands: Product Branding from SMEs in the Publishing Industry.” Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 21 (2): 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-07-2017-0022.

- Parnell, Claire, Alexandra Dane, and Millicent Weber. 2020. “Author Care and the Invisibility of Affective Labour: Publicists’ Role in Book Publishing.” Publishing Research Quarterly 36 (4): 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-020-09763-9.

- Parnell, Claire, and Beth Driscoll. 2021 “Institutions, Platforms and the Production of Debut Success in Contemporary Book Culture“. Media International Australia 187(1): 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X211036192 .

- Squires, C. 2007. Marketing Literature: The Making of Contemporary Writing in Britain. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Striphas Ted. 2015. “Algorithmic culture“. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4–5): 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415577392

- Surma, Anne, and Daymon. Christine. 2013. “Caring About Public Relations and the Gendered Cultural Role.” In Gender and Public Relations: Critical Perspectives on Voice, Image and Identity, edited by Christine Daymon and Kristin Demetrious, 46–66. London: Routledge.

- Thompson, John B. 2012. Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. Westmeadows, Australia: John Wiley & Sons.