ABSTRACT

True Crime Games is an award winning Melbourne-based game company headed by artist and designers Andy Yong and Emma Ramsay. This paper explores the first of their games–Misadventure in Little Lon – a case study that brings to light local histories that have been lost, elided or marginalized in traditional accounts of Melbourne and its development around the time of Federation. Drawing upon the phenomenology of Vivian Sobchack and the microhistory of Carlo Ginzburg, the article argues that implementing AR in historically driven game contexts allows for an improved grasp of the microhistory of a specific area. It does this by bringing the agency to the ‘ghost in the machine’ –characters in the AR game who enable players to resituate themselves and reorientate themselves to city streets through game play. This method of resituating historical sources so that players discover ‘opaque zones’, new ways of viewing located history that encourages reading ‘against the grain’ , is coincidental with important archaeological work that has been undertaken in the Little Lon district of Melbourne. Misadventure in Little Lon therefore joins a larger effort to reveal, circulate and celebrate the communities, individuals, and stories that traditional histories have ignored.

History, I have long felt, is an outdoor as well as an indoor occupation.

-(Davison Citation2004, viii)

Misadventure in Little Lon is an Australian 2019 augmented reality (AR) game produced and made by partner team Andy Yong and Emma Ramsay as the launch game for their company, True Crime Games. This article argues that the game provides a case study in the way microhistory can be mobilized by AR to offer what I am terming the experience of historical ‘presence.’ That is, Misadventure in Little Lon enables the player to gain insights and access to otherwise lost, forgotten, or overlooked histories. In providing an experience that draws us into the contours of a single historical event (the circumstances surrounding the death of a man named Ernest Gunter in Melbourne, in September, 1910), the game helps us to unpack the people, events, and contested explanations that surrounded Gunter’s death. It does this through a process of narrative and locational inquiry, using AR to expose some of the people and histories that have been traditionally elided from Melbourne’s history. This focus on the experience of an event unfolding across the city, and the revelation of new and unfamiliar histories, indicates that the game is not an electronic version of a written text, nor an audio tour that allows you to plug in headphones and have a new history recounted to you as you are guided through city streets. Instead, Misadventure in Little Lon gives players the ability to choose how they want to play (alone or in a group, with a tablet or phone, at any given time, on any particular day, and at a pace they can determine). It urges players to choose and decide outcomes based on the facts presented, and to ask questions.

Focused on the altercation between a man named John Evans with Gunter on September 3rd, and then Gunter’s subsequent death on 9 September, the game is set in a period of time that is notable in Australian history. Indeed, 1910 was the year that Australia had its first national coinage issued. This was also a period when Melbourne was the state capital where the new Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia convened. It is to be recalled that Australia was a nation that had only recently been formed through the Federation of six British colonies (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania) in 1901. It was not until 1913 that Canberra was named the nation’s capital, and not until 1927 that Federal Parliament was relocated. In 1910, Melbourne was consequently a stable and important national city that had weathered the boom-and-bust decades of the late nineteenth century. In this earlier period, Melbourne was best known as ‘Marvellous Melbourne’: a global city whose population of almost half a million rivalled major European capital cities, where modern industry was celebrated through the introduction of cable trams, electricity, telephones, and skyscrapers, and where major international exhibitions were held in 1881 and 1888 (Davison, Citation2004). Although the prosperity of Marvellous Melbourne did not continue – the depression of the 1890s saw banks collapse, and a third of all wage earners lose their jobs – the year that Misadventure in Little Lon returns us to be one in which Melbourne had re-emerged as a political and cultural hub in the world’s newest nation.

Prompting questions to be asked to a range of historically verifiable individuals across a series of Melburnian locations, Misadventure in Little Lon removes itself from the more grandiose sweep of Federation and other teleological, national histories that often frame our understanding of this period of time. Instead, Misadventure in Little Lon literally integrates AR into the streetscape of our experience as a player. Through directed gestures (tossing a coin, offering a handkerchief, lighting a candle), we are encouraged to engage in and question figures who emerge to describe a local history. This modest piece of Melbourne’s history does not so much contest official histories of 1910s Melbourne, than supplement and expand them through the player’s own experience. ‘Little Lon’, we learn, was a vibrant, important early twentieth century working-class slum. It boasted a wide and diverse range of cultures and communities, and these expose a history of people and quotidian objects that might otherwise be lost today.

Misadventure in Little Lon can be played both on location and off-site. Whether or how the game perceptively and historically grounds domestic and/or transnational participants in its off-site iteration is beyond the scope and intent of this article. It is the located, in situ version of the game that I explore. Indeed, what interests me is the coincidence of Misadventure in Little Lon with developments in our local understanding of Melbourne’s anthropology and archaeology. As I will evidence below, the game materializes and makes available a burgeoning public awareness of the idiosyncratic nature of the Little Lon district. While microhistory and it’s relationship to AR will be discussed further below, it is the work of historian Carlo Ginzburg that informs the understanding of microhistory throughout this article. As Ginzburg explains in a 2015 interview, microhistory does not mean that we study small things; it is ‘not the cult of the fragment (or the case [study]), as such.’ It is instead a method that applies a ‘microscopic’ (and therefore scientific) regard to history, so that the fragment or historical case study can allow us to raise further questions, or to understand new, provisional realizations (Ginzburg Citation2015).

Locating ‘Little Lon’

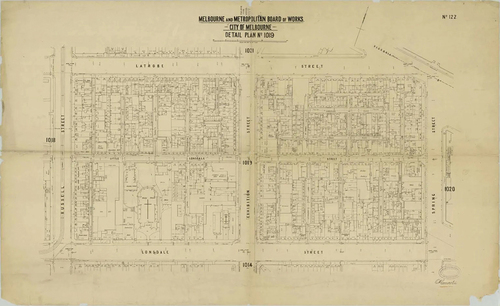

For those who are not familiar with Melbourne, it is important to introduce the location of the game. Little Lon is a discreet area that is today part of the inner-city. The eastern boundary of this is Spring Street, the west is marked by Exhibition Street; it includes Lonsdale Street to la Trobe Street, with Little Lonsdale Street going through the middle []. As Michael Shelford has explained, for the purposes of Misadventure in Little Lon the two adjacent blocks (that is, covering the area through to Russell Street) are included in the Little Lon district (Godden Citation2020). This is where the events that we are tracing historically took place; we therefore literally return to the space where history happened.

Figure 1. Yong and Ramsay’s working map for Little Lon, Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works, 1895. Image courtesy of Yong and Ramsay.

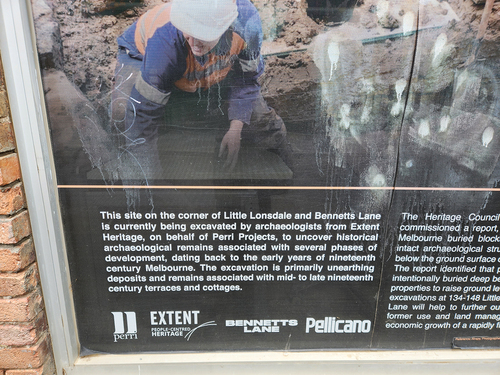

Little Lon is the precinct that bounds the experience through which we are led; it is also a district where a series of archaeological digs have recently been undertaken in Melbourne. The introduction to Museums Victoria’s Little Lon Collection explains that archaeological excavation has taken place in Little Lon in 1987–8, 1991, 1995, 2001, and 2002–2003 (Willis Citation2010). Over half a million artefacts were recovered in these digs. More recently, two excavations were undertaken in 2017 (Executive Media Citation2021); in 2020 another excavation began in Little Lon (Rees Citation2022). Just two years ago, one of the ‘best buried blocks’ in Melbourne was discovered when developers Perri Projects and Pellicano bought a site to develop a 20-storey office building (Dexter Citation2022). Co-incidentally, this means that Misadventure in Little Lon is played, at least in one of it’s ‘located’ scenes, alongside a fenced site that provides signage to confirm the archaeological significance of place. In other words, Misadventure in Little Lon technologically reconfigures the cultural space of a neighbourhood and community, while archaeological digs take place around it.

I was introduced to Misadventure in Little Lon a little belatedly, at the Extended Reality Forum at Deakin University in 2021. Meeting one of it’s two makers (Andy Yong) at the Forum, I became aware of the difficulty of locating the game in terms of industry funding for project development. My reflections on Misadventure in Little Lon therefore emerge from discussions generated in the Forum itself, but also sit in an ancillary relation to it. I focus on the technological enablement that AR brings to the telling and experience of local microhistory, rather than on the language that we might (or might not) use in industry and archival contexts. I also consider what this AR game captures in terms of microhistorical method, rather than what happens when the mobile devices it supports are no longer available. In other words, what interests me – and what motivated me to spend days carrying a dated iPad around a small network of streets in inner city Melbourne to experience the game – is the way that Misadventure in Little Lon uses microhistory to burrow into a singular event so that we imagine and experience history in its phenomenological ‘locatedness’. I believe the game’s major achievement lies here, in the critical and cultural space that AR establishes in relation to our perception of history, particularly when this history is subsequently covered over, to make space for new urban office blocks.

Where are we now? Changing the scenes of the screen

As a phenomenological experience, Misadventure in Little Lon grounds us in a particular social and cultural history through the functionality of our mobile screens. Such a grounding – and I discuss this further below – has nothing to do with the realism of the characters and objects we engage with on our screens, nor with the veracity of the gestures we need to enact in order to action the game forward. Instead, a grounded experience of being (in the body, in its location in a determined streetscape) emerges because of the historical perception that this AR game extends. The significance of contemporary historical perception being both enabled and extended through the computer-generated technology of an AR game can be appreciated if we return to Vivian Sobchack’s essay, ‘The Scene of the Screen: Envisioning Photographic, Cinematic, and Electronic “Presence”.’ Here, Sobchack characterizes her present moment in terms of ‘the electronic’ (Sobchack Citation2004, 140). She describes the electronic as ‘a centerless, networklike structure of the present, of instant stimulation and impatient desire’ (152); she argues that the electronic ‘constructs a metaworld where aesthetic value and ethical investment tend to be located in representation-in-itself’ (154). Correspondingly, Sobchack concludes that the dominant cultural techno-logic of the electronic diffuses and/or disembodies ‘the lived body’s material and moral gravity’ (158).

Arguing that the culturally pervasive technologies of photography, cinema, and the electronic media of television and computer have radically remade the expression of the world and, with it, our sense of ourselves within it, Sobchack is reflecting on the late twentieth-century’s changed co-ordinates of our shared social, personal, and bodily existence. Sobchack situates these changes in the historical framework of revolutionary capital (or rather, in Fredric Jameson’s seminal model of how capital develops). As Jameson argues,1840s market capitalism gave way to 1890s monopoly capital, which finally changed to multimodal capitalism in the 1940s. For the purpose of this article, what is important about these successive periods of economic and social change is that Sobchack integrates perceptual revolution into the more traditional categories of economic, social and industrial revolution. As her title indicates, she is concerned with phenomenological presence in a period where electronic screens proliferate and predominate. How we collectively yet also individually navigate and make sense of who and where we are through these screens is what Sobchack explores. Because she wrote her article roughly 30 years ago, Sobchack focuses on film, television and the computer as the technologies that bring perception into being.

Opening her essay with a provocative and emphatic reminder that technological expression is indelibly tied to phenomenological perception, Sobchack asks: ‘What happens when our expressive technologies also become perceptive technologies – expressing and extending us in ways we never thought possible, radically transforming not merely our comprehension of the world but also our apprehension of ourselves?’ (135). Sobchack’s answer to this question locates her computer-generated electronic moment as one which increasingly disembodies, refuses, and elides our lived bodies. Because of this, she concludes that ‘we are all in danger of soon becoming merely ghosts in the machine’ (162). While Sobchack is cautionary about us all becoming ‘merely ghosts in the machine’, I argue that Misadventure in Little Lon evidences the ways in which electronic media does not so much free the body and/or elide its perceptive presence, but actively prompt us to seek, activate, materialize and make sense of historic ‘ghosts’ in the machine. Indeed, Misadventure in Little Lon builds a meeting ground around electronic ‘ghosts’: the gamer is present but disembodied in the game, while historical characters are re-embodied as ‘ghosts’ who engage the invisible gamer in play. In this context, Misadventure in Little Lon is a cautionary celebration – not just of new developments in the frontiers of expressive technologies such as AR, but of history becoming a pervasive benchmark in the contemporary perception of ourselves. In other words, a fundamental premise of Misadventure in Little Lon is not just that the user has access to the technological capacity of an AR game (a phone, a tablet), but that through this game they can correspondingly transform their perception of Melbourne, its history, and their own place within it.

Learning to listen: audible instructions from a ghost in the machine

An important ‘ghost’ that we meet in Misadventure in Little Lon is not, however, imaged or pictured on our screen. She is the buoyant, first-person narrator whom we follow through the game, or rather, who tells us the rules of the game, and who narrates findings and reflections in the game. Providing the geographic and historic context for the Melbourne in 1910 that we apprehend, her character is that of an entrepreneurial young news reporter. In her introduction, we learn a range of facts. Firstly, that Melbourne’s history can be constructed and recounted as an oral history, and that this history can be spoken, presented and interrogated by a young woman. Narrative authority, the construction of story, and even the ability to independently negotiate the city streets in order to meet and question participants and witnesses is thereby firmly feminized (Abel Citation2021). Moreover, Melbourne is presented as a city which was important enough to attract international visitors (our narrator mentions the ‘escapologist’, Hungarian-born American Harry Houdini), enable public research in a State Library, and contain a thriving slum district in its city centre. We begin, therefore, with the acknowledgement of Melbourne’s cultural presence on the world stage, and with the awareness that women might interrogate evidence and tell important newspaper stories.

Poised as both our geographic navigator and our news narrator, this female voice is a teacher who leads us through a history of Melbourne that frames the city at the opening of the last century. Much of what we learn in this history coincides with the findings of recent scholarship, particularly around its attention to the diversity of communities that came together in what was earlier dismissed as a ‘slum’ (Hayes and Minchinton Citation2018; Minchinton Citation2021; Murray and Mayne Citation2003; Murray et al. Citation2019). Moreover, it is the availability of developments in historical thought and methods through a pervasive technology that drives my approach to AR and Misadventure in Little Lon. I regard the game and its availability on our screens as a form of enablement. AR is a technology that can ensure that microhistory – in this case, a popular, working-class microhistory, informed by working class experiences, events and people who sit, historically, on cultural and social margins – circulates through a developing mass medium to audiences. While there are still certainly social and financial barriers to access the game – a player needs a phone, working internet, to pay the $6 fee for the game, and time to play – what is inspiring about Misadventure in Little Lon is that these marginal histories can now reach and be understood by players who might not be vaguely interested in microhistorical method and developments in academic scholarship.

In this context, we can relate Yong and Ramsay’s commitment to representing the cultural physiognomy of working-class culture in Melbourne through an AR game to Ginzburg’s efforts in his seminal 1976 study, The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller. Opening the English preface to this history of Domenico Scandella, called Menocchio, a miller of the Friuli in the sixteenth century, Ginzburg states that his intention was to make history newly available to a wide range of readers. Working with the tools he had available to him – and therefore changing the style and format of the published history book – Ginzburg explains:

The Cheese and the Worms is intended to be a story as well as a piece of historical writing. This, it is addressed to the general reader as well as to the specialist. Probably only the latter will read the notes–which have been deliberately placed at the end of the book, without numerical references, so as not to encumber on the narrative. But I hope that both will recognize in this episode an unnoticed but extraordinary fragment of a reality, half obliterated, which implicitly poses a series of questions for our own culture and for us.

These projects – an AR game exploring a lost and overlooked history of Melbourne on the one hand, and a traditional but newly organized written history of an individual in preindustrial Europe on the other – are published in radically different circumstances and contexts. Nevertheless, they can be linked in their shared effort to popularize a lost fragment of history; to make it pervasive and available. Both histories, the AR game and Ginzburg’s accessible footnote-free book, can also be linked in their shared effort to promote and make visible histories that emerge through the study of historical records that open or enable lines of active inquiry on behalf of readers and researchers: police files, coroners reports and newspapers on the one hand, and Roman inquisitorial papers on the other. Adopting and encouraging the player’s own role as an active ‘reader- and in a sense ensuring that game play is seen in terms that resonate with Ginzburg’s own project of making history accessible, engaging, and meaningful to general audiences, the first-person reporter in Misadventure in Little Lon urges us to listen, check evidence, and read against the grain (‘don’t judge a book by its cover’). This encouragement given to the player as an agent in the discovery and uncovering of historical meaning means that the player is an active audience member. In this sense, they enjoy their ‘reading’ agency across and within the city in a process that parallels, in a sense, the process that Ginzburg describes when he explains that we can find layers of unwritten meanings hidden in historical, written texts. As Ginzburg explains in his discussion of microhistorical method in the introduction to his later work, Threads and Traces: True False Fictive: ‘By digging into the texts, against the intentions of whoever produced them, uncontrolled voices can be made to emerge: for example, those of women or men who, in witchcraft trials, eluded the stereotypes suggested by the judges … Reading historical testimonies against the grain … means supposing the every text includes uncontrolled elements’ (Ginzburg Citation2012, 3–4).

Opaque zones and blindspots: creating the experience of perceptive presence

When Ginzburg discusses reading historical sources against the grain, noting uncontrolled elements that spur new perceptions of history, he speaks of locating ‘opaque zones’ in a text (4). These opaque zones are evidence marshalled in the text’s retelling. They enable new ways into a text, and thus new ways of perceiving our relationship to history. Ginzburg does not relate these opaque zones to written texts alone: he states that opaque zones can be phenomenological (‘the perceptions that sight registers without understanding them’) as well as technological (and so related to finding opacity in ‘the impassable eye of the camera’) (4). In Misadventure in Little Lon, the game begins with the death of Gunter and our hunt for different witness testimonies. In this way, we are introduced to the opaque zone of the coroner’s finding of ‘death by misadventure’. Original newspaper articles are available during play, and these confirm the way that Gunter’s death was inserted into the public realm, circulated widely across local and regional presses, and justified administrative findings. At the same time that we can read these excerpts, the game exposes the contradictions in the submissions made to the police by witnesses and parties to Gunter’s death. In this way, the user’s own perceptive experience of the AR game makes them party to textual opacity. Rather than having history recounted, or simple answers found to the questions ‘Who died?, When?, How?’, users are encouraged to explore history in a dialogic way. They are then able to reach their own conclusion about the circumstance and cause of Gunter’s death.

The opacity surrounding Gunter’s death was established by the work that local historian Michael Shelford undertook over a fifteen-year period while exploring the police files of the Public Record Office of Victoria. Shelford is the host of True Crime walking tours of Melbourne; he uses his research in the Public Record Office to inform the local tours that he hosts (Godden Citation2020). It was while undertaking one of Shelford’s tours that Yong and Ramsay began to think about putting the realization of their AR game into the streets of Melbourne. Shelford subsequently became a Historical Researcher credited on the Misadventure in Little Lon. In a certain sense, then, the oral history that Misadventure in Little Lon presents is a new technological realization of the changing parameters of these walks, and so a new technological tool brought to publicize (and make articulate) changes to historical perception. A game that is more accessible (and affordable) than a specific, scheduled Melburnian walking tour, Misadventure in Little Lon widens and expands possible audiences for Sheldon’s research.

It was during the slow process of examining police records that Shelford found conflicting accounts of Gunter’s altercation with Evans in 1910. This evidence exposed the gaps and omissions in the newspaper account of Gunter’s death; it also furnished evidence of the corruption in legal (and coronial) administration in turn of the century Melbourne. As Shelford explains,

When we get through to the coroner’s court, and I won’t ruin the story too much, there were differing explanations of what occurred that day. So, John Evans, from his side of things, and a lot of witnesses backed him up, said that Ernest Gunter had run at him with a knife in each hand, with murderous intent, and that he had simply thrown a punch to defend his own life. It was self-defence. When you get through to the other side of things, and that includes his sister Maud, who was present there at the time of the fight, they said they did not see any knives. In fact, he was baited to go back to the [Exploration] Hotel. Evans [then] ran out of the hotel, and hit him, blindsided him, when he was not expecting it, which is why his head impacted with the pavement. So, two very different stories.

The opacity surrounding Gunter’s demise is relayed, on the AR game, through the range of individuals we encounter during our exploration of Little Lon []. The characters that we meet – with the exception of the young newspaper boy – were drawn from the primary research Shelford undertook in the Victorian Police archives. Factual figures whose physiognomy is also based on existing indexical evidence (such as photographic mug shots), they meet us as animated characters in our screens with their own personalities, attitudes, and requests. There is a range of perspectives provided: the policeman at the site of death (Constable Barclay), the sister of the victim, Maud Gunter, the victim, Ernest Gunter, the suspect, John Evans, the ‘Bourke St Rats’ (gang members) Evans, McAuliffe, and Minnie Barry, as well as Reverend Adgar, and Gunter’s friend and possible lover, Cecelia Hamilton [ and ].

After we have met and questioned each character – and sometimes we meet and engage with them more than once – we are asked to decide the outcome of what we now understand to be a historically unresolved true crimes murder/manslaughter case. A series of questions is then posed: Was Ernest Gunter defenceless when he was stuck down? What were the circumstances of Gunter and Evans’s meeting? Did Gunter antagonize Evans by making an unwanted sexual advance on ‘his girl’? Showing competing sketches of each possible conclusion, and summarizing the evidence (now literally) drawn, the game exhorts: You Decide. We do indeed decide, clicking on whatever image (of two) best represents our conclusion.

While the division of our response into two options suggests that one is right, the other is wrong, this is not the case. We earn no game points nor prizes, there is no ‘hurrah’ moment. The picture chosen merely fades to another set of possible outcomes, and then we learn how Maud Gunter (Gunter’s very independent and strong sister) responded to his death. What we therefore achieve, through the playing of the game, is not historic certainty about a series of facts. Rather, we learn that history is opaque, even in its minutiae; we learn that the question of what is true, false or fictive must be brought to all historical sources. When we click on an image on our devices, we are making our own muddled way through competing sources and stories. In this game, AR is a technological tool that encourages a wider array of audiences to engage with an overlooked story; while we cannot argue that AR is historically transformative, it can certainly help change perceptions of Melbourne’s past.

Picturing people: animated avatars of engagement

It is the characters we meet in Misadventure in Little Lon who allow us to decide if a historic miscarriage of justice indeed took place in the coroner’s court of 1910. I have written above about how the female reporter is never imaged as a physical ghost within the screen. She is someone who creates co-ordinates, who is always on the move, and who leads us to locations and sites within Little Lon. In contrast, when we meet characters in Misadventure in Little Lon, we meet them as visible bodies who float, ungrounded, within the otherwise indexical frame of our mobile screen. These bodies are not avatars, lost within the spectacularity of a flat digital image. Nor are these ghosts a collective consciousness, somehow disenfranchised across a heterogeneous, kinetic and shifting datascape (where, as Sobchack states, we either ‘free-float, free-fall or free-flow’) (Sobchack 159). Rather, the ghosts in Misadventure in Little Lon are reimagined and animated spectres of past people who speak to us from the perspective of their own historic reality. They are also – to players – artificial humans who float, unapologetic apparitions on our mobile screen. They block themselves in bodies that are visually dense (we cannot see through them; they occupy their space) but that look artificial and computer-generated. Their clothes have texture (wool, cotton) and colour (grey, brown, white, possibly a burst of flowers on a hat) []. There is nothing unusual in this: the game engine is a resource whose logo is flashed into the ‘Place the scene’ prompt. What is interesting is therefore what we take largely for granted – the same but different bodies we engage, with clothes that hang on standardized frames, and that express modular movements that repetitively loop through gestures in order to enact digital presence.

Elusive yet brought into being through our various acts of ‘placing’ a scene, these figures hover unrealistically within the borders of our mobile phone or iPad. They are either too small or too big for the environment. Their figures are decipherable and actionable, negotiable on a street corner or against a wall, but never appear literally to scale. Even the act of sequential placement, in the sense that we are led from one physical site to another, is one of the location and not of scalability or size. We therefore scan the ground slowly, with our mobile devices slanted on the correct gradient angle needed to make these ghosts appear; we need to pinpoint place through this process in order to action AR. Once we click on placement, a figure and related objects appear. If we come too close to a figure we walk right through them, if we move too far away, we are unable to action the game. We might play with the character’s awkward ambition of spatial presence, but we need at some point to nevertheless maintain a distance to ensure the game’s functionality. That is, we can never lose sight of the fact that these ghosts are technological phantoms, summoned into our screen in order to transform ourselves as users of the game. The ghosts are not there to spread us across a digital platform, but are here to help us comprehend an inner city block, and our apprehension of our selves within it.

Materials that make meaning: the archaeology of AR

Our apprehension of history’s opacity is a layered experience. Each character brings more details, conflicting ideas, different facts to the newspaper articles we read about that describe Gunter and Evans’s altercation, and Gunter’s death. Our apprehension of history’s opacity is equally enabled by the range of materials we must engage in order to elicit (trigger) a verbal and/or gestural response from each character. With each character, therefore, comes a new range of objects to activate – these might be Gunter’s wallet, a Chinese hatpin, money, a newspaper, a two-up ‘kip’, a bottle of wine, a lighter, a tin of humbugs, or a handkerchief. With each object, again artificially reconstructed as a computer-generated asset, we are reminded that 1910 is a period of history that can be associated with a series of objects, clothes and materials that are specific to this time. In gesturing to activate any one of these items in the game, the player is exposed to an AR-generated material history. This material history coincides with discreet, physical gestures: for example, the ‘kip’ is flipped and the handkerchief is for dabbing tears. Becoming their own opaque zones of meaning, our embodied interactions with these game objects develops our ability to appreciate intergenerational historical difference. Not only has a new event been unearthed for us to explore, but Melbourne’s history is also re-told through the presence and function of ‘archaeological’ objects whose uses are possibly unfamiliar to us today.

We begin the game, most obviously, with a newspaper boy selling us a newspaper we must flick through. Child labour, the engagement of women in the new industrial urban workforce (and recall that our central female narrator is a news reporter), the use of printed language to build working-class community, and the location of news in printed sheets that are exchanged for physical coinage are all showcased in this scene. Instructed by the newspaper boy as to the whereabouts of a newsworthy story, we move on to ‘find’ a wallet with photographs hovering on the street beside Gunter’s bloody body. The wallet is an object of worth, that carries black and white photographs within it, and is exchanged for information from Gunter’s sister, Maud. Maud, in turn, gives us a Chinese hatpin to pass on to our next character. A symbol not only of the integration of different cultural communities within Little Lon (and Maud’s partner, we learn, is Chinese), the hatpin also provides a message for Cecelia Hamilton, and is equally an item of female adornment and a weapon.

What we learn through this process of materializing objects is that each item can have a variety of uses (the hatpin), or it can be foreign to us (the small piece of wood we use to toss pennies in the ‘two-up’ game we encounter). An object might also be familiar to us – the white handkerchief, for example, used to quieten Cecelia Hamilton’s melodramatic tears. Even if familiar, it can nevertheless be experientially foreign for us to offer a handkerchief as a function of a game, and to learn that it can be considered an item of exchange. While I spoke above about characters appearing as animated ‘ghosts’ on screen, these objects are instead found objects that prompt the ghost story, that become part of the game’s telling. What is important here is the association of AR to the artificial archiving of material function, and also the relationship between AR and archaeology. Specifically, Misadventure in Little Lon leads us to and continually celebrates Melbourne’s hidden, lost, or elided materiality in everyday objects we might otherwise miss: printed local papers that are held and exchanged for community news, a random piece of white embroidered cloth, the lighting of a real fake candle with an animated flip top lighter, and so on.

While this AR game makes us think about and engage with found objects, it is nevertheless hard to argue that our activation of animated objects is archaeological. The layers that are exposed in each object (in meaning, in function, in exchange value) are, after all, dependant on the awkward artificiality of an on-screen swipe, tap, or toss. Like the characters in the game, they are also game engine assets, Unity Game Engine resources to be used in trade. Equally, they are objects that join us to the AR characters on screen, that represent a coming together or unity of shared endeavour. Indeed, if we take into account the locations in which items must be bought, swapped, exchanged, used or gifted, we begin to appreciate the impact that Misadventure in Little Lon has when played in situ, as an experience in the places and spaces where archaeological evidence has been painstakingly collected. These places are still, some five years after the game’s launch, literal sites of archaeological excavation. In this context, the digital context of our own archaeological dig within the game is activated in a space that reminds us of what we learn when we literally dig beneath the ground we stand on.

I mentioned, above, that in 2022 a site on Bennett’s Lane was being excavated to reveal hidden and lost treasures. Described in The Age as ‘Melbourne’s own “Pompei”’, what reporter Rachel Dexter highlighted was how an ‘unassuming site’ had transformed to become an ‘open-cut pit revealing layers of archaeological remnants’ (Dexter Citation2022). It is beside this site, on Bennett’s Lane, that we encounter Gunter’s bloody body and find his wallet on our first stop in the game. As a billboard in this location explains (beneath photographs of archaeological workers and above the logos of developers and excavators):

This site on the corner of Little Lonsdale Street and Bennetts Lane is currently being excavated by archaeologists from Extent Heritage, on behalf of Perri Projects, to uncover historical archaeological remains associated with several phases of development, dating back to the early years of nineteenth century Melbourne. The excavation is primarily unearthing deposits and remains associated with mid- to late nineteenth century terraces and cottages. []

What is interesting is the reiteration of the archaeological significance of the found materials in the location of an AR game ‘placed scene’ (which is outside the original site of Gunter’s collapse at the Exploration Hotel). What is also interesting is the serendipity of its cross-over into a contemporary excavation site that was not operational at the time of the game’s conception, development and delivery. Significantly, this site is fast disappearing. As Dexter concludes in her discussion in The Age in 2022, ‘The public has only about another month to walk past and see the site while the excavation is being completed, before all artefacts are ripped up and put in storage to make way for the several basements of the new office tower’. In this context, Misadventure in Little Lon becomes a perceptive technological tool guiding us back to some of the history that we are standing upon. Ironically, it is therefore AR that grounds the user in a moment of artificial yet historical happenstance.

The last shot: an augmented assemblage

When Sobchack discussed phenomenological presence in the age of the computer, she staked her critical ground in relation to experiences of the flesh: AIDS, homelessness, hunger, torture, the bloody consequences of war, and other ills that the lived body might experience (Sobchack 162). Countenancing the difficulty of lived experience with the insubstantiality of the digital image and the datascape, she argued that we need to remain attached to the value of our bodies, our flesh, and our grounded experience of the world. Sobchack first wrote her article in 1994 as a chapter in the book, Materialities of Communication. When she developed her essay a decade later, in 2004, she responded to critiques of this initial publication. In her developed, 2004 paper, virtual reality (VR) was consequently added as a rejoinder in one of her footnotes. Here, Sobchack argued that VR re-embodies us in electronic space, yet nevertheless devalues our lived body in these same ‘fantasies of reembodiment.’ To put it simply, Sobchack argued that there was no space or place for the integration of accumulated, lived experience with on-screen intertextual presence since it denied the body’s presence.

Twenty years after Sobchack insisted that we remain grounded in our bodies so that we keep our moral and physical gravity, we might argue that Misadventure in Little Lon provides a grounding experience across both of these fronts. An AR game that presents us as absent ‘ghosts’ to ‘ghosts’ in the machine who inhabit their own historical time, we together co-create an opaque zone of Melbourne’s history. This unfurls across a narrated and experienced story whose meanings and moral gravity are held at significant game point pieces- archaeological sites where we are asked to stop, engage, reconsider. The story of Gunter therefore emerges in the shape of a perceptive and receptive assemblage, thanks to these various and changing stages of game play. What we take seriously, what links us to the lived experience of the here and now, is the capacity to be artificially transported to the there and then, through an augmented reality that maps itself into and onto screens. These screens help us arrive and depart from where we stand. They also help us access a range of information, highlighting new histories of the working class, their community and physical experiences and exchanges that we might never before have considered or even known existed.

The AR experience of Misadventure in Little Lon ends when it brings us back to the female newsreporter in the city, telling the tale of Maud Gunter – Ernest’s vengeful sister, who was also a powerful sex-worker, running brothels across Little Lon. Responsive to the injustice of her brother’s death, we learn that Maud was angry at the miscarriage of law. Misadventure in Little Lon does not conclude, therefore, with the player’s decision about what represents the ‘right’ image in its pairing of summary sketches. Instead, Misadventure in Little Lon ends with our discovery that Maud took things into her own hands, unsuccessfully hiring a hitman to kill Evans. The ghosts in the machine might be digital avatars with modular movements, but they also remind us of the importance of historical presence, public history, and of the shifting horizons of our shared ethical being in the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abel, Richard. 2021. “Movie Mavens.” US Newspaper Women Take on the Movies, 1914-1923, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Davison, Graeme. 2004. The Rise and Fall of Marvellous Melbourne. 2nd ed. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press.

- Dexter, Rachel. 2022. “Melbourne’s Own ‘Pompeii’: Buries Neighbourhood Found in Bennetts Lane.” The Age. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/melbourne-s-own-pompeii-buried-neighbourhood-found-in-bennetts-lane-20220805-p5b7hv.html.

- Executive Media. 2021. ““Melbourne’s Little Lon” Traces: Uncovering the Past.” (Blog), Accessed June 9, 2021. https://tracesmagazine.com.au/2021/06/melbournes-little-lon/.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. ““Microhistory” Filmed.” Serious Science. Accessed June 25, 2015. https://youtu.be/VFh1DdXToyE?si=7ka0BBW706QmTOcd.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 1992. The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller. John and Anne Tedeschi, Translated by. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 2012. Threads and Traces: True False Fictive, edited by Anne C. Tedeschi and John Tedeschi. Berkeley and Los Angeles: The University of California Press.

- Godden, Carley. 2020. “Using Technology to Bring Life Stories from the Past.” Filmed, Australia: Royal Historical Society of Victoria video, 1:03:10. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLxsXs0-MzM.

- Hayes, Sarah, and Barbara Minchinton. 2018. “Sex and the Sisterhood: How Prostitution Worked for Women in 19th-century Melbourne.” The Conversation. Accessed February 14, 2018 6.06am AEDT, Arts, https://theconversation.com/sex-and-the-sisterhood-how-prostitution-worked-for-women-in-19th-century-melbourne-89858.

- Minchinton, Barbara. 2021. The Women of Little Lon : Sex Workers in Nineteenth Century Melbourne. Collingwood: Black Inc. Accessed October 2, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Murray, Tim, Kristal Buckley, Dr Sarah Hayes, Geoff Hewitt, Justin McCarthy, Professor Richard Mackay, Barbara Minchinton, Charlotte Smith, Jeremy Smith, and Bronwyn Woff. 2019. The Commonwealth Block, Melbourne : A Historical Archaeology. Vol. 7. University of Sydney, NSW, Australia: Sydney University Press. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=04ea1bce-b497-3c94-b623-4aca5e24114b.

- Murray, Tim, and Alan Mayne. 2003. “(Re) Constructing a Lost Community: ‘Little Lon,’ Melbourne, Australia.” Historical Archaeology 37 (1): 87–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25617045.

- Rees, Brendan. 2022. “Archaeologists Uncover Remnants of Historic Homes at Construction Site.” CBD News. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.cbdnews.com.au/archaeologists-uncover-remnants-of-historic-homes-at-construction-site/.

- Sobchack, Vivian. 2004. Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Willis, Elizabeth. 2010. “Little Lon Collection in Museums Victoria Collections.” Accessed December 2, 2023. https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/31.

- Yong, Andy, and Emma Ramsay. 2019. “Misadventure in Little Lon.” In True Crime Games. Augmented Reality, Australia: Yong and Ramsay.