ABSTRACT

Founded in 1997 by arts and community workers, the Feast Festival in Adelaide is one of the major LGBTQIA+ festivals held in Australia. 2022 marked the 25th year of the Feast Festival and, as such, was an opportunity to reflect upon the importance of community-driven festivals, especially those that explicitly services and advocates for social and cultural minorities. Researching this queer history required multimodal strategies. We interviewed past participants, organizers and performers, which resulted in a short documentary film that was exhibited as part of Feast’s 25th programme. This project has also been supported by extensive archival research. We investigated the role that archives play in research and in documenting the history of a community arts festival, and how archives can actively contribute to the research process at various stages of data collection and creative artefact creation. Further, we explored the festival organizers’ careful engagement with both open-access and curatorial approaches to festival management, including engaging with the South Australian LGBTQIA+ community to encourage participation and develop special events for the programme.

Introduction

In 2022, as we prepared to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Feast Festival in Adelaide, South Australia, we developed a project to showcase the significance of the festival’s history through a short film.Footnote1 Founded by Helen Bock, Damien Carey, Luke Cutler and Margie Fischer in 1997, Feast is South Australia’s leading arts festival for the LGBTIQIA+ community. This research concerns the accessibility of festival history, and in doing so, it is also our aim to make visible the often more hidden elements of qualitative research practices. So, while our ‘end’ artefact was a short documentary film, we seek to illustrate how archives can contribute not just to interviewing strategies via connecting with participants, and to the shaping of a creative output, but also how the archive can be brought ‘into the present tense, and at the same time animate the past’ (Munro Citation2025). We address each of these dimensions of research practice in turn throughout this article, informed by a research-creational approach (Loveless Citation2019), which we explain below.

In researching the Feast Festival’s history, we engaged in a project that sought to be a multidisciplinary blend of archival material and images, creative and analytical writing, audio recordings and uncut on-camera interview footage as a means to queer archival research. This research was further aided by the serendipitous discovery of archival material that was initially disposed of at an independent community arts organization (see ). After a chance lunch catch-up with a former artistic director of the festival, we managed to rescue this material only days before the waste bins, where the archive had been discarded, were scheduled to be collected. This article further details how this discovery and rescue of the archive contributed to our project by strengthening our understanding of the nature of queer open-access festivals through using this material as both an interviewing strategy, as visual material in the short film, and as a lived example of the precarious nature of queer archives. Therefore, we also illustrate how archives, often conceptualized as static, are instead active when utilized in interview settings and subsequent analysis of other festival ephemera. Or, as Jamie A. Lee describes, ‘oral history interviews produced for and within archives, work to further disrupt the long-standing traditional archival paradigm that advocates for a static and fixed archival record’ (Lee Citation2019, 162). Tracing through the different dimensions of this project, the archival material, the interviews with participants, and the creative artefact that was later screened at the festival, we further argue that returning to queer archives, in particular, demonstrates what Cvetkovich (Citation2003) terms ‘an archive of feelings’. Through this mixed-methods approach of both creative and critical responses, and engagement with a creational-research approach (Loveless Citation2019), we demonstrate that a strong engagement with the community is fundamental to the management of an open-access community festival. As such, the premise of this research project is itself multifaceted, in that researching the history of a marginalized community requires multimodal strategies that are sensitive to the histories and emotions of the participants of the project.

Materials and methods

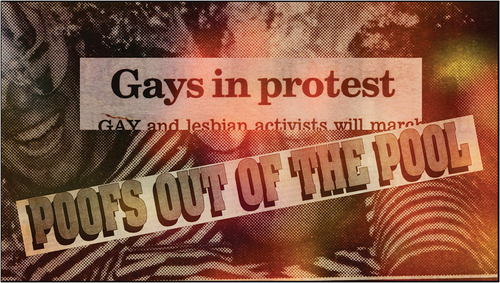

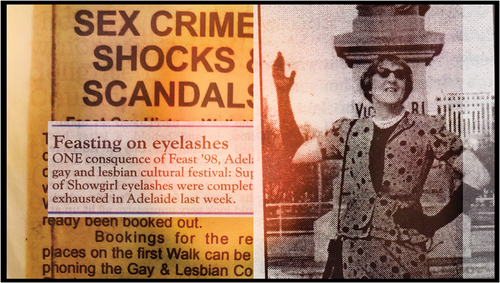

We initially conducted 14 interviews over Zoom with key past and present festival directors, board members, performers, producers and attendees. These were semi-structured interviews consisting of three primary questions. First, we asked what their best Feast Festival memory was as a means to break the ice and also to capture stories pertaining to their experience. Second, we asked what the Feast Festival meant to them to elicit responses pertaining to social and cultural value. Finally, we asked what they thought was the future of queer festivals in the contemporary era. This final question aimed to elicit responses pertaining to the precarious nature of community arts, as well as the interviewees’ perceptions of the significance of queer-run events and spaces. When asking these questions, we also showed them material from the rescued archive that either referenced them directly or other significant moments from the festival’s history. These significant moments included the attempt by a collective of conservatives to sabotage a pool party event by sneaking in and putting pink dye in one of the pools required for the event. The saboteurs put dye in the wrong pool, and the event carried on. However, the pool party attendees were, on the day of the event, met with a picket line of homophobic protesters dressed in Grim Reaper outfits and the chant ‘poofs get out of the pool’ (a newspaper clipping in refers to this event). Telling stories such as this, which were often met with humour as well as pensive introspection, contributed greatly to the interview process. Prior to conducting these interviews, we had spent several months ordering, reading and sorting the archive, which contained newspaper clippings of stories such as this one. Thus, incorporating these significant details was a deliberate interviewing strategy, for notions of selfhood, identity and meaning making are often not things that people will address head on. Instead, ‘they are [often] an exploration of representation, image and possibilities’ (Bloustien and Peters Citation2011, 44). Anthropologist and digital ethnographer Sarah Pink speaks more directly to this kind of experiential ethnography and the limitations of more traditional question-then-answer interviews:

Figure 2. Archival material used in Feast: 25 Years (source: Munro Citation2022).

[The interview] is a social encounter – an event – that is inevitably both emplaced and productive of place. It has material and sensorial components. Interviewees refer to the sensorality of their experiences not only verbally … but through sounds (e.g. playing music, demonstrating a creaking door), images (sharing photographs) and even tastes … An emphasis on ‘talk’ in discussions of what interviewing involves, and dependency on conversation analysis as a means of understanding the sorts of interactions that occur during interviews (e.g. Rapley 2004; Seale 1998) limits the ways interviews can be understood.

Following these, at times, materially sensory interviews, we conducted a series of on-camera interviews for the short film, eliciting further stories of pivotal Feast memories. We also encouraged participants to wear whatever they most felt comfortable in, and for some, this led to on-camera explanations about why their chosen outfits were so meaningful to them amid broader notions of ‘visibility’ and past events of the festival. This archival research in combination with the on-camera interviews resulted in the creative artefact of a short film that was screened at the 25th anniversary of Feast in Citation2022 titled Feast: 25 Years.

These methodological choices around multidimensional research outputs were deliberate. Queer archives or non-institutional archives, or what other researchers have termed ‘community-based archives’ (Lee, Finley Alper, and Emswiler Citation2023, 384) are ‘composed of some of the most valuable records documenting the living histories and contributions of non-dominant peoples and their home communities’. Inviting our participants to assist in the creation of a creative artefact that reflected their contributions was a powerful intervention. Or, as Natalie Loveless writes in her book How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation:

Research-creation, taken as critical interdisciplinary praxis, asks us to attend to how we habitually justify our research through disciplinary stories, those that we tell and those we have been told along the way. It also … asks us to attend to the form of those stories. A research-creational approach not only asks us to attend to whether we personalize our writerly voice, render it poetic, or write in a ‘neutral’ voice of authority; it asks us to question whether writing, on a page, in an article or book format, is, indeed, the appropriate, most effective, persuasive, or interesting way to ‘write’ our research. What if the most powerful way to communicate the research embodied within a certain ‘chapter’ is not to write about it on a page, but to ‘write’ it through video? Or in a multimedia installation? Or with a live performance event? Or through an art-activist intervention?

In this way, we, as researchers, aimed to invite our participants into a research-creation process, and in turn, create new material that was both reflective of the past, taking place in the present and to be remembered in the future.

Literature review

Archives have long been critiqued as social constructions. Foucault (Citation1969 Citation1969) argues that the archive is not an entire account of a culture but rather an unseen and domineering structure that organizes social values and systems of knowledge. This structure allows for the visibility of some elements and the invisibility of others. Therefore, Lord, Marchessault, and Chew, Lord, and Marchessault (Citation2018, 8) argue, ‘archives are not static, transparent, value-neutral things filled with unchanging information, but rather are sites of struggle shaped by dominant ideologies’. Lord et al. highlighted the value of counter-archives that draw on the counter-cultural energies of archivists and volunteers. Brett Kashmere (Citation2018) develops this definitional work further by positing that archives can simultaneously be anti-archives through their engagement with both conservative and destructive functions, as archives are often repositories of other people’s refuse. We literally embodied this notion of the constant tussle between conservation and destructive functions of archives as we rescued much of the Feast Festival’s archives from the trash.

The traces of event-based community activism are often found through ephemera. Zielinski (Citation2016, 139) argues that film festivals, for example, not only borrow from queer histories and posit new queer pasts and futures but also produce new affective ephemeral material that is folded back into queer cultural experience. This ephemera gives us insight into how queer publics formed. Zielinski (Citation2016, 149) argues:

Festival ephemera have found ways to reference the affective histories of AIDS, the culture wars, gender struggle, LGBT movement, but also pop culture – films and television, especially via celebrity and camp culture associated with certain films. Another important source is queer cultural history itself, along with its specialized motifs and signs, including more ephemeral gestural tropes associated with queer bodies, as José Muñoz (1996) might call it.

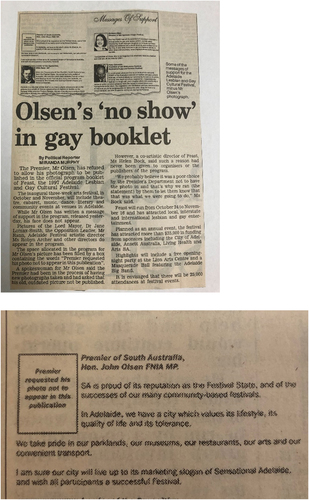

For example, in our rescued archive, we found a newspaper clipping that detailed how the state premier in 1997 (conservative politician John Olsen) refused to have his picture featured in the inaugural Feast Festival programme (see ). This material speaks directly to both the cultural history and political history of the operation of the festival. This story was included in a range of interviews as a way to reference significant historical moments and the broader social movement of queer inclusion and gay liberation in South Australia.

Figure 3. Press clipping from the advertiser newspaper and a close-up of the inlaid image with the text ‘Premier requested his photo not to appear in this publication’.

In his book LGBTQ Film Festivals: Curating Queerness (Damiens Citation2020) argues that smaller, marginal festival events are key to understanding the formation of queer (film) culture. He writes that some festival studies have a proclivity to privilege ‘festivals which have the resources, expertise, and will to preserve their own history [which excludes] amateur or less legitimate events which never attempted to safeguard their historical records in the first place’ from the body of festival studies proper (Damiens Citation2020, 50). In employing the term ‘festival as a method’, Damiens analyses the material of festivals – trailers, programmes, posters and other sorts of ephemera – to argue that these events generate an important body of knowledge that lets us appreciate the connection between queer communities and film. Festival events are not just the subject matter of research but also creators of knowledge in and of themselves. The precarious nature of the Feast archive, for instance, demonstrates the connection between South Australian social movements and community art practices. This body of knowledge afforded by the Feast archive is a result of the informal archival practices of key individuals associated with the festival.

Both Damiens and Zielinski draw on Cvetkovich’s (Citation2003) concept of an archive of feelings in the context of the lived festival. Ann Cvetkovich’s concept is founded on the notion that trauma is a social and cultural category. She theorizes the relationship between archives and the assemblage of audio-visual cultures, especially when concerning oft-hidden pasts and archives. Cvetkovich (Citation2003, 109) writes that ‘film and video can extend the reach of the traditional archive, collating and making accessible documents that might otherwise remain obscure except to those doing specialized research’. In drawing on Cvetkovich, Damiens argues that the curatorial processes at the queer film festival connect queer histories together in an act of projection. Past and present connect, creating an affective experience that simultaneously creates an archive of feelings while also generating new cultural memories.

Results: making history accessible

Feast: 25 Years was a creative artefact that generated an archive of feelings for Feast. More importantly, however, these queer archives, which are often unstable and multidimensional, contributed to our project by strengthening our understanding of the nature of queer open-access festivals. This final step of turning some of these stories into on-camera interviews and screening them at a public event was an important and deliberate choice that we made for two reasons. First, we did not just want to do research on a minority community, even one that we happen to be members of. Far too often research is made inaccessible to those who contributed to its existence. Second, we wanted to make something that the festival could use, either as a promotion for future funding, to promote its current programming, and also as a commemorative artefact, a slice of Feast history. And in fact, it was our desire to make an accessible artefact that directly led to the cooperation of many of our participants. This speaks to Cvetkovich’s argument that multimodal usages of archives ‘demonstrate the profoundly affective power of a useful archive’ (Cvetkovich Citation2003, 241). She continues: ‘Lesbian and gay history demands a radical archive of emotion in order to document intimacy, sexuality, love, and activism – all areas of experience that are difficult to chronicle through the materials of a traditional archive’ (241).

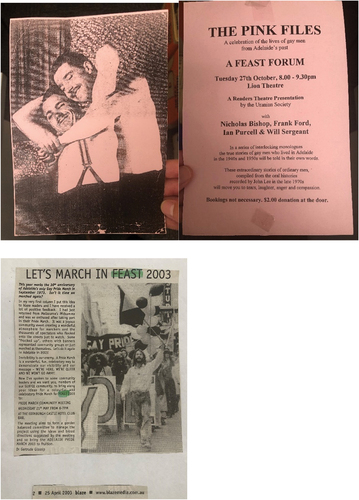

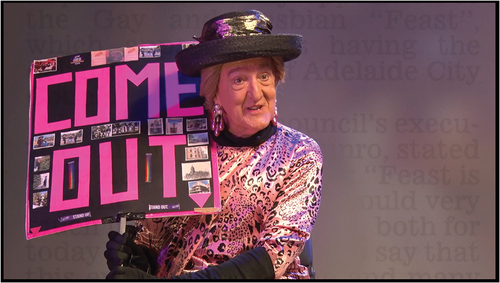

The power of queer archives, as such, is founded upon a history of traumatic loss associated with the organization of the sexual publics. Without fully realizing it at the time, these archives, an unexpected and serendipitous find for this project ended up making a significant contribution to our data collection and interviewing strategies via their emotional connotations. As we began the first round of interviews, which took place via Zoom, there were many instances where we brought up a newspaper clipping, story or artefact that had a relationship to the participant. The archive offered a number of unintended intimacies, uncovered partial stories and faceted histories, providing inspiration, humour, sadness, controversy, nostalgia and pride. This archive offered material that sparked sensorial and ephemeral components of our interviews. For example, several pieces of material featured the extensive work of historians Ian Purcell and Will Sergeant (see ). When interviewing Will, who performs as Dr Gertrude Glossip on the Adelaide LGBTQ History Walks, we drew his attention to archival material for several events, such as The Pink Files musical written by Purcell and the first Pride March in Adelaide in 1973 where Will featured prominently (as he would later remark, ‘I was the “I” in PRIDE’) while he recounted his memories of these events (see ). These materials from the archive, such as flyers and newspaper clippings that we could hold and show participants, helped us gain the participants’ trust. This elicited responses that went beyond the typical question-then-answer interview.

Figure 4. Image of the pink files flyer front and back, and Will as the I in PRIDE at the 1973 pride March in Adelaide.

Figure 5. Gertrude Glossip and her iconic ‘COME OUT’ sign in feast: 25 Years, which featured in her history walks (source: Munro Citation2022).

Ian Purcell and I devised the history walks. We were approached by Margie Fischer, one of the artist directors … that very first one, doing it for the first time, being on the street frocked, was a very special memory that stays with me.

What became clearer as the interviews with participants progressed was that the archive also became an unintended member of the research team – asking questions and contributing in ways that we had not fully anticipated. Using an archive in interviewing settings, and also framing it as another fieldwork site, is all at once ‘conceptual, theoretical and practical’ (Kumbier Citation2014, 2). It takes up space, quite literally, and also gives it. Having to sort this archive, having it take over most of the free space in our offices, we have since begun to wonder whether queer archives themselves are inherently queered. And are we, through our own intuitive process of chronological ordering and discarding, subjecting this archive to an unintended homonormativity? These are questions we currently do not have an answer to – such is the nature of the research that is part of a broader, ongoing project. Joan Nestle, founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archive in Brooklyn, and long-time archivist, historian and activist, recently commented in an interview with the Australian Queer Archives and the National Gallery of Victoria that we need to beware of public archives creating what she terms ‘a dangerous respectability’ for queer culture (NGV Citation2022). She also says that living with history can often be harder than living without history because then we have a record of our failures as a community. So perhaps it does not have to be an either/or. Perhaps it is the blurry nature of queer archives, the ecosystem of micro histories and macro institutions, the affective spatial folding of past and present that gives queer archives in particular the remit to operate as sites of both resistance and respectability.

There is much slippage across the participants’ answers about their best Feast memory and what Feast means to them. Using these interviews in the short film demonstrates the entanglement of memory through the site of a queer festival. Dr Gertrude Glossop, above, spoke of their activism in the 70s, and creating the first gay history walk of Adelaide in the inaugural year of the Feast See . Bel Mac (see ) spoke of firsts, a kink space where queer fat black bodies like her own could be vessels for erotic pleasure and admiration:

Everyone was walking around with their leathers and buckles, and they were all sizes. They were women of all sizes and that did something for my innards because there is not always the space to be anything but what we see in the media. And here was a space where people were being revered and adored and respected and owned and powerful and fierce within their own self. Not in spite of their size. Big eye opener … you are allowed to do you. As a thicker Aboriginal queer woman, there’s not a lot of spaces in Australia for that but there is at Feast.

Figure 6. Having this material on hand, and being able to directly show it, coaxed Sergeant to refer to festival highlights that featured Purcell.

Figure 7. Bel Mac shares her personal experiences of feast in feast: 25 years (source: Munro Citation2022).

She also spoke about how very vital it was in her own experience to be seen and to be visible:

I did Pride march with my partner at the time, and my same-sex partner, which was massive. It was my first out relationship. And my brother and his partner. Walking through the streets of Adelaide and looking at my brother and looking at my partner. And in that moment, of feeling both entitled and free to be in that space. That was a big one.

This supports the notion that queer festivals are themselves sites of activism and emotional complexity. There was also a sense of agency created with being a presence on film – being seen, and being visible. But festivals do not exist in social, cultural or economic isolation. They change, adapting to changes in policy, funding cuts (particularly within the Australian context, see Pacella, Luckman, and O’Connor Citation2021), and an evolving demographic. For what is an open-access queer festival, if not a representation to and of the community it is meant to serve?

Queer festivals, open access and curation

The research into Feast’s history via their archives has contributed to our understanding of how open-access festivals must maintain a strong connection to their community. The queer festival has always been an integral player in the development of queer art, culture and politics. Many began as underground radical and experimental art events that directly challenged the dominant ideologies of sexuality and gender identity. The queer arts festival has long been at the intersection of community and neoliberal creative industries (Richards Citation2016). These festivals are sites of exhibition for LGBTQIA+ creators so that they can access the community and vice versa. However, as Richards (Citation2016) has argued, in order for the festivals to achieve their social missions, they must achieve financial sustainability. To fulfil their social mission, queer festival directors and curators engage with various income streams to create sustainable social transformations. This is a dramatic development from the early inceptions of the queer festival, many of which began as activist-based community art events. For Dhaenens (Citation2022), queer festival organizers tend to see their organizational role as a political one. In his analysis of BFI Flare, however, ‘the adoption of a creative industry logic resulted in an identity politics that only partially and subversively criticizes the hegemony of heteronormativity’ Dhaenens (Citation2022, 852).

Like many other community-based arts organizations, the queer festival has traversed the arduous journey from being an informal event to a professional organization. In a neoliberal arts economy, this adds to the precarity that many marginalized communities already face.

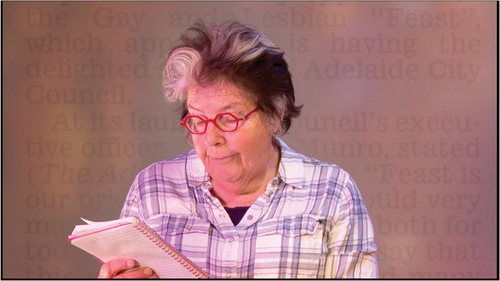

Margie Fischer (see ) spoke to this challenge of running a queer festival in a commercialized creative arts sector. ‘The lack of funding and understanding of the value of the arts,’ she says in Feast: 25 Years, ‘and constantly having to repeat this over the years and being despairing’ is key to her experience of Feast.

Figure 8. Margie Fischer lists what feast means to her in feast: 25 years (source: Munro Citation2022).

Festivals transform places for a temporary period of time, with what Jarvis (Citation1996) refers to as transitory topographies. Writing on how festivals support place creation and promotion, Waterman (Citation1998, 58) argues that

successful festivals create a powerful but curious sense of place, which is local, as the festival takes place in a locality or region, but which often makes an appeal to a global culture in order to attract both participants and audiences.

In the context of a city, such as Adelaide, the Feast archives demonstrate how activists and artists maintain this localized connection with community while also engaging with an arts economy that addresses global trends.

Considering the changing political dynamics of the queer arts festival, Feast: 25 Years and the accompanying interview recordings provided an archive of feelings that reflected on the changing importance of Feast as a queer cultural festival. This shift from community event to a site of professional development, as discussed by Richards (Citation2016) with other queer festivals, is evident in the archival material. Queer art spaces, as such, have the power to challenge this alienation and neoliberalism of the contemporary culture. Queer festivals, Greer (Citation2012) writes, often share a common ambition to both stage and challenge the notion of queer culture and its relationship to non-heterosexual identities and experiences. Since neoliberalism ‘reinforces and reproduces inequalities’ (Mtewa Citation2003, 39), the queer festival must not be swayed by this economic approach, which ultimately disempowers many stakeholders.

It is important to clarify that a festival is so much more than the artworks, performances, parties and films that are programmed. Festival studies have historically ranged from anthropological to sociological. Jean Duvignaud (1976, 13) argues that the classic analysis of festivals goes back to Émile Durkheim, who distinguished between the sacred and profane and wrote about ‘collective effervescence’ as the supreme moment of the solidarity of collective consciousness. This development of queer arts festivals has thus had an impact on the nature of social activism. Loist (Citation2011) argues that we need to examine the queer festival in terms of power dynamics, including how cultural and finance capital are disseminated through various stakeholders and, more importantly, how this power can overcome the precarity of the more marginalized in these community spaces. This is particularly important when we consider the relationship between queer arts festivals and the broader arts sector.

Community festivals in particular also create social capital, which is the cornerstone of how community arts organizations are understood. Putnam (Citation1993) defines social capital as the connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of exchange and trustworthiness that arise from them. Queer festivals create social capital through developing community resources, and amplifying community and social cohesion, particularly during times of community hardship such as the debate for Marriage Equality in Australia. They also facilitate celebration and community life. When asked what Feast meant to her, Feast co-founder Margie Fischer offered the following list:

It means hard work, giving queer artists a platform, grant applications, worrying about money, the pleasure and honour of working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander queer artists and community members, the opportunity to meet and work with young queer people, performing in the festival, ‘Writing Live’ which is my favourite part of the Feast program, forums, which turned into queer conversations, which explored ideas and opinions and diversity, the queer spirituality conference, which happened really early on in Feast, the queer history conferences, the terrible times with some people I have come into contact with during my work at Feast, the lack of funding and understanding of the value of the arts and constantly having to repeat this over the years and being despairing, the weight of responsibility, issues about archiving, what is kept and what remains. And wanting the best for Feast in the future. That’s what Feast means to me.

Phrases such as ‘weight of responsibility’, ‘grant applications, lack of funding and value of the arts’, ‘archiving and what is kept’ are all discursive narratives that evoke vast organizational complexity. The use of archival material was key to developing trust with Fischer in our interview, which in turn elucidated the role of social capital in the community development of a queer open-access festival. Arcodia and Whitford (Citation2007) argue that festivals encourage a more efficient use of community resources by giving organizers and participants the opportunity to explore local resources that previously may have remained anonymous and not generally available for everyone’s use. The social networks that can develop through the organization of festivals have the potential to continue far beyond the short life of the festival. Festivals which involve volunteers provide opportunities for training and development in a variety of skills and encourage more effective use of local educational, business and community spaces (see Richards, Pacella, and Munro Citation2023). These community networks ensure a high level of social connectivity by re-introducing a healthy relational dimension to societies.

Feast is an open-access festival, and this provides unique opportunities for queer social capital to develop. The open-access model requires artists or companies to register on the platform and take the artistic and financial risk of the entire process. The artists work with venues to produce and deliver the events as part of the overarching structure of the festival. The festivals also handle the ticket sales of the event and pay income to the artist and venue. There are challenges within the open-access model, however. As Caust (Citation2019) notes in her work on the open-access model in South Australian festivals, artists at festivals with large programmes such as SALA and Fringe can feel lost. Caust writes: ‘certainly, the hyperbole about being in a festival is attractive, but the reality for many is that they do not receive the exposure they expected and are liable to incur much greater expense than they had envisaged’ (Citation2019, 302–303). Artists and event coordinators that we interviewed certainly mentioned the importance of registering an event with Feast, in that there were benefits of being a queer artist in a queer festival. Margie Fischer argues that a community-based open-access festival requires community development:

Proper inclusion in the Feast Festival for me means that you don’t just go, here’s a Feast Festival and you can register events if you want to register an event, but it means doing community development where you actually go out to marginalized communities and invite them in and listen to what people want and go hunting for older people, young people, poor people, people from non-English-speaking backgrounds, Aboriginal people, gender-diverse people, people who wouldn’t necessarily feel included, people who need encouragement and to be invited in and then to talk to them about. That’s how Out Black Adventures started – saying what do you want to do? Is there something that you are interested in showing/doing/creating? Then getting the money for them to do it and bringing it all together. That’s what inclusion is. And then including the audiences! So making sure that there’s events that are free, events that are popular, like daytime events like picnic in the park, being associated with Pride March … inclusion of all sorts of audiences.

In arguing for an accessible and inclusive First Nations festival, Duffy and Mair argue that ‘a community festival is … constituted out of a complex set of power relations that nonetheless serve to define notions of belonging’ (Duffy and Judith Citation2015, 54). Fischer, above, articulated the need to dismantle these social barriers to accessibility for marginalized community groups. Another participant, Skye Bartlett, also spoke to this position:

Queer spaces are incredibly important and queer arts festivals are even more important because so many queer people don’t have an outlet to express themselves, to produce something that is their own voice into the world. So, festivals like Feast allow community members to express that light, express their voice in ways that they would never normally be able to. It’s such an important element of self-expression. Being able to express yourself through art … is very important. It’s what makes us human and able to communicate with each other.

In returning to the notion of a festival archive being a constantly fluctuating archive of feelings, archival material provided us with further details on how festival coordinators and participants connect with their art, local community, political contexts, and ultimately their own histories. To return to Cvetkovitch, viewing queer archives through the lens of emotion and trauma is fundamental to unpacking their queerness. Queer archives, Cvetkovitch writes, ‘address particular versions of the determination to “never forget” that gives archives of traumatic history their urgency’ (Cvetkovich Citation2003, 242). Having access to ephemeral material allowed us to build that trust in these interviews as we navigated these histories. Using archival material in this manner is demonstrative of making the complexities around open-access community festivals tangible.

Conclusion

To return to Lord, Marchessault, and Chew, Lord, and Marchessault (Citation2018, 8), archives are not ‘value-neutral’, but are ‘sites of struggle’. Drawing on the Feast archives meant a multifaceted approach was necessary to engage with the participants and, in turn, Adelaide’s queer history. Through our engagement with this archival material, we were able to draw on this history in our interviews, which made Adelaide’s queer history more accessible, and present to our participants. This archive will continue to evolve as all community-engaged archives do. Drawing on Loveless (Citation2019), the use of this material contributed to the film Feast: 25 Years, which was vital to our research-creational approach. Our use of this material and approach to these recorded interviews and short film was shaped by Cvetkovich’s notion of the archive of feelings and how they can be useful to their communities. Audio-visual culture, Cvetkovich (Citation2003) argues, extends the traditional reach of the archive. Photographs of activist Ian Purcell, flyers for Gertrude Glossip’s Queer History Walks and Margie Fischer’s events like Out Black Adventures are examples of artefacts that shaped an emotional connection between the researchers and participants. The short film, which was screened at an event at the Capri Theatre for a Feast audience, which included notable participants in the film, connects present community members with Adelaide’s queer history. The use of the material allows for a dance between past and present, producing new emotional and cultural resonances.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Susan Luckman and everyone at the Creative People Products and Places Research Centre. We would like to thank Dr Kim Munro and Dr Rosie Roberts for their involvement in the earlier stages of this project. We would like to thank Kate Leeson for copy editing assistance. We would especially like to thank all of the participants associated with the Feast Festival for taking part in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The short film is available on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/763088081/ea267e8abc.

References

- Arcodia, Charles, and Michelle Whitford. 2007. “Festival Attendance and the Development of Social Capital.” Journal of Convention & Event Tourism 8 (2): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J452v08n02_01.

- Bloustien, Geraldine, and Margaret Peters. 2011. Youth, Music and Creative Cultures: Playing for Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Caust, Josephine. 2019. “Open Access Arts Festivals and Artists: Who Benefits?” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 49 (5): 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2019.1617811.

- Chew, M., S. Lord, and J. Marchessault. 2018. Introduction. Public Journal: Art, Culture, Ideas 57 (57): 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1386/public.29.57.5_1.

- Cvetkovich, Ann. 2003. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Damiens, Antoine. 2020. LGBTQ Film Festivals: Curating Queerness. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Dhaenens, Frederik. 2022. “Moderately Queer Programming at an Established LGBTQ Film Festival: A Case Study of BFI Flare: London LGBT Film Festival.” Journal of Homosexuality 69 (5): 836–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1892405.

- Duffy, Michelle, and Mair. Judith. 2015. “Festivals and Sense of Community in Places of Transition: The Yakkerboo Festival, an Australian Case Study.” In Exploring Community Festivals and Events, edited by Allan Jepson and Alan Clarke, 54–65. New York: Routledge.

- Foucault, Michel. 1969 2006. “The Historical a Priori and the Archive.” In The Archive, edited by Charles Merewether, 26–30. London: MIT Press.

- Greer, Stephen. 2012. Contemporary British Queer Performance. London: Palgrave.

- Jarvis, Bob. 1996. “Mind/Body = Space/Time = Things/Events.” Urban Design Studies 2:101–114. http://www.araxus.org/urban_design_studies_4.html.

- Kashmere, Bree. 2018. “Neither/Nor: Other Cinema as an Archives and an Anti-Archives.” Public Journal: Art, Culture, Ideas 57 (57): 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1386/public.29.57.14_1.

- Kumbier, Alana. 2014. Ephemeral Material: Queering the Archive. Sacramento, CA: Litwin Books.

- Lee, Jaime A. 2019. “In Critical Condition: (Un)becoming Bodies in Archival Acts of Truth Telling.” Archivaria 88 (Fall): 162–195.

- Lee, Jaime A., Bianca Finley Alper, and emswiler Emswiler. 2023. “Origin Stories and the Shaping of Community-Based Archives.” Archival Science 23 (3): 381–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-023-09413-x.

- Loist, Skadi. 2011. “Precarious Cultural Work: About the Organization of (Queer) Film Festivals.” Screen 52 (2): 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjr016.

- Loveless, Natalie. 2019. How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mtewa, Phumi. 2003. “GLBT Visions for an Alternative Globalization.” In Globalization: GLBT Alternatives, edited by Irene Leon and Phumi Mtewa, 35–48. Quito, Ecuador: GLBT South-South Dialogue.

- Munro, Kim. 2025. “The Art of Work is a Work of Art: Feminist Theatre and Live Documentary.” In Women and Documentary: Global Practices, Global Perspectives, edited by Najmeh Moradiyan Rizi and Shilyh Warren. London: Bloomsbury Press.

- Munro, Kim dir. 2022. Feast: 25 Years. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

- NGV. 2022. QUEER X AquA: Mining Queer Histories | Queer People Archiving Their Histories. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/multimedia/queer-people-archiving-their-histories/.

- Pacella, Jessica, Susan Luckman, and Justin O’Connor. 2021. “Fire, Pestilence and the Extractive Economy: Cultural Policy After Cultural Policy.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1833308.

- Pink, S. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Putnam, Robert D. 1993. “The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life.” The American Prospect 4 (13): 35–42.

- Richards, Stuart. 2016. The Queer Film Festival: Popcorn & Politics. New York: Palgrave.

- Richards, Stuart, Jessica Pacella, and Kim Munro. 2023. “Comradery and the Arts: Experiences of Senior Volunteers in a Festival City.” Journal of Festival Studies 5:326–355. https://doi.org/10.33823/jfs.2023.5.1.139.

- Waterman, Stanley. 1998. “Carnivals for Elites? The Cultural Politics of Arts Festivals.” Progress in Human Geography 22 (1): 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298672233886.

- Zielinski, Ger. 2016. “On Studying Film Festival Ephemera: The Case of Queer Film Festivals and Archives of Feelings.” In Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice, edited by Marijke de Valck, Brendan Kredell, and Skadi Loist, 138–158. New York: Routledge.