ABSTRACT

There has been a relative dearth of scholarly discussions surrounding the production of girls’ love (GL) narratives in mainland China since the 2010s. This article offers an illustrative case study of a successful GL multimedia storyworld, Couple of Mirrors (CM), which unfolds across a webtoon, a novel, and a web series. First, this article scrutinizes the multilevel state regulation on queer content creation in different media formats. Second, we draw on Henry Jenkins’ canonical conceptualisation of “transmedia storytelling” to delineate the ways that the production of CM differs from the mainstream BL transmedia stories. Through a textual and paratextual analysis of official producers’ and fans’ participation, we argue that CM’s transmedia storytelling creates explicit GL elements through negotiation between market preferences, heteropatriarchal ideologies, and governmental censorship. In doing so, we show that CM represents a successful non-heteronormative cultural commodity within the mainland Chinese media market.

Introduction

This article examines the creation and consumption of girls’ love (GL) narrative in mainland China media market in the post-2010 years, when an abundance of queer Chinese media and pop cultural content has been produced due to the rapid expansion of digital media and the influence of transnational queer culture. Among these non-heteronormative cultural commodities, boys’ love (BL, or danmei 耽美; male same-sex romance) novels and drama adaptations have achieved continuous popularity and attracted mainstream attention. However, Chinese GL literature has remained at a lower level of visibility (Zhao and Ng Citation2022, 303), and its drama adaptations have remained largely non-existent. Against this backdrop, this article investigates the GL product Couple of Mirrors (Shuang Jing 双镜, 2021, hereafter CM), which was released as a webtoon (a type of digital comic that can be read vertically by scrolling down on a smartphone or computer), a novel and a live-action web series in 2021. CM is a rare and salient example showing how transmedia storytelling is essential to creating GL narrative and granting it visibility in the Chinese entertainment industry and heteronormative society, considering the marginalized position of GL cultural products therein.

As a popular genre in contemporary East Asian pop culture, ‘GL’ originated from Japan and is often used interchangeably with yuri (literally ‘lily’) in the Japanese context. The yuri genre, including animation, manga, fiction and TV drama, focuses on the intimate relationship (which may or may not involve sex) between two females (Yeung Citation2017, 36–37). After being introduced to the Chinese fan community, yuri has witnessed the emergence of a Chinese localized equivalent baihe 百合 (literally ‘lily’). Both ‘GL’ and ‘baihe’ are widely used in the Chinese ACGN (animation, comics, games and novels) fandom, but the Chinese fandom sketches different scopes for them: ‘GL’ involves homoeroticism and sex, while ‘baihe’ focuses more on spiritual intimacy, being an emotional bond that is more than friendship but not as close enough as romantic love (Lin Citation2018, 205). In addition, female same-sex intimacy does not necessarily indicate lesbianism for Chinese fans of queer content. GL/baihe is a fictional representation developed from writers’ creation as well as readers’ imagination and consumption of female homoerotism, while lesbian is a sexual identity label in real life with social and political meanings, encompassing gender politics, movements or activism (Lin Citation2018; Yeung Citation2017). In this article, we understand GL as queer content by following the line of thought in the rich scholarship of queer Chinese media and pop culture. This body of research uses ‘queer’ to ‘loosely refer to all kinds of nonnormative representations, viewing positions, identifications, structure of feelings, and ways of thinking’ (Zhao, Yang, and Maud Citation2017, xii), and ‘does not necessarily emphasize the linkage of queer media and culture to gay identity and LGBTQ politics and activism’ (Zhao Citation2022). It focuses on ‘the media and cultural representations, productions, and celebrity and fan cultures situated within and contradictorily enabled, commodified, celebrated, and carefully regulated by the largely heteronormative environment of contemporary China’s mainstream globalist media industries and neoliberal public spaces’ (Zhao Citation2022). In this sense, GL is not necessarily transgressive but is nonetheless nonnormative within the context of state regulation. We use ‘GL’ rather than ‘lesbian’ and ‘baihe’ to refer to CM as it is less associated with gender identity construction or LGBTQ+ activism, and the relationship between the two female protagonists in the CM storyworld, particularly as depicted in the webtoon, is more than spiritual intimacy.

Since commercial GL media products have rarely been produced and circulated in the Chinese cultural industry, CM can be considered one of the first mainland-made GL media products, the success of which benefits from the transmedia storytelling deployed by its producers. The CM webtoon was published serially from 24 February 2021 to 25 March 2022 exclusively on Kuaikan Manhua (hereafter Kuaikan), which is an online platform to share and publish Chinese-language webtoons in the domestic market. The novel was published in paperback in June 2021 by Sichuan Literature and Art Publishing House, and the two authors, Zhao NaFootnote1 and Li Zongchen are exactly the two screenwriters of the web series. On 12 August 2021, the CM web series (12 episodes) premiered on the ACGN-themed video streaming platform Bilibili exclusively in mainland China and on YouTube for the overseas market simultaneously. Although released later than the webtoon and the novel, the web series is the origin of the CM storyworld as the other two were adapted from it.

After being released for less than a month, the web series’ number of views reached 100 million on Bilibili on 7 September 2021. By the end of June 2024, the CM web series had achieved a rating of 9.6/10 (more than 29,000 ratings) on Bilibili and garnered 9.8 million views on YouTube; the webtoon had received 1.31 million likes and a rating of 9.3/10 (897 ratings) on Kuaikan; and the novel had received a rating of 96.6%/100% (92 ratings) on the reading app WeRead. By disseminating the stories in multiple media, the commercial producers have been able to create a cohesive storyworld where female intimacies and homoerotism are depicted at varying degrees under state regulatory policies.

In the following sections, we first scrutinize the rules and regulations governing state censorship of queer content creation in different media formats in mainland China. We then provide an overview of transmedia practices in the contemporary Chinese popular cultural industry. Specific focus is placed on how the production of CM is different from the mainstream BL transmedia stories and how it can enrich Jenkins’ conceptualization of ‘transmedia storytelling’. Through a textual comparison of the GL content delineated in CM’s three media and a paratextual analysis of fans’ transmedia engagement, we argue that CM’s transmedia storytelling exemplifies the efficacy and complementary nature of multiple media in explicitly integrating and spreading GL elements. This occurs against the backdrop of the dynamic and multilevel state censorship of queer content in different media and the market’s preferences for heterosexual or male–male romance.

The state regulation on creating and displaying queer content in contemporary China

Queer media content, like BL and GL, has been confronted with state censorship in contemporary heteronormative Chinese society. Since CM has released three different formats, i.e. web series, webtoon and novel, it is important to understand how censorship on commercial queer content has been operated divergently across media and platforms. After reviewing relevant rules and regulations, we find that censorship is tighter in web series and physical book publishing than in webtoon.

In July 2017, China Netcasting Services Association (CNSA), a government-affiliated organization under the supervision of the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), released the Wangluo shiting jiemu neirong shenhe tongze [General Provisions on Reviewing of Content in Online Audiovisual Programmes],Footnote2 which provided details on the regulation of content in online audiovisual programmes, such as web series, web movies, cartoons and documentaries. It is stipulated that programmes should not express and display abnormal sexual relationships and sexual behaviours, such as incest, homosexuality, sexual perversion, sexual assault, sexual abuse, sexual violence, etc.; otherwise, the plots should be cut or deleted before broadcast, and if the problem is serious, the entire programme must not be broadcasted (XinhuaNet Citation2017). In this case, streaming service platforms are required to exert self-censorship first before airing. In cases where a programme arouses controversy after broadcasting, NRTA will intervene.

Different from web series, webtoons are not counted as ‘wangluo shiting jiemu’ [online audiovisual programmes] but rather ‘wangluo chubanwu’ [online publications]. In February 2016, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT, which was reformed into NRTA in 2018) and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology released the Wangluo chuban fuwu guanli guiding [Regulations on the Management of Online Publishing Services]. This Regulations does not prohibit homosexual content, but it states that online publications must not contain any content that promotes obscenity, pornography, gambling, violence or incites crime (The State Council, PRC Citation2016). It also stipulates that online publishing service units need to have professionals responsible for reviewing online publications’ content, ensuring its quality and legality; local publishing administrative departments of places where online publishing service units are registered should supervise the content and quality of online publications, organize regular content review and quality inspections, and report the results to the higher-level publishing administrative departments (The State Council, PRC Citation2016). These policies illustrate that online publication service units, including literary websites, need to self-review the content they publish. However, the oversight conducted by local authorities is characterized as ‘dingqi’ [on a regular basis] rather than consistently implemented. Moreover, considering the tremendous quantity of web novels and webtoons, the actual implementation of such censorship is relatively looser than that of web series and print books.

When it comes to physical book publishing, it shows another picture. To publish a book, an author needs to send their applications to the publishing house, and then the publishing house needs to register it with the National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA) and obtain an ISBN from NPPA after being approved. Previously, SAPPRFT was responsible for the supervision and management of the press and publishing industry. It was abolished in 2018, and since then the Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee has taken over this part of function in a unified manner but performs the responsibilities in the name of NPPA (XinhuaNet Citation2018). Such adjustments illustrate that the government has tightened its regulation of the publishing industry for sociopolitical and ideological purposes. In January 2019, the Publicity Department published Tushu chuban danwei shehui xiaoyi pingjia kaohe shixing banfa [Trial Measures for the Assessment and Evaluation of Social Benefits of Book Publishing Units] to evaluate parameters such as publication quality, cultural and social influence, and professional characteristics of publishing houses. For the parameter of ‘Neirong zhiliang’ [content quality], publications are assessed against the criteria of whether they implement the Party’s theories, principles and policies, adhere to the correct political direction, publication orientation and value orientation, and ensure the overall quality of publication content (Sohu Citation2019). Although these regulations are not directly related to queer content creation, it is apparent that publishing houses will be cautious when choosing what themes to publish and how to implement content review by themselves.

The above analysis shows that state regulatory authorities exert different levels of supervision for different types of media or cultural products in the Chinese market. Notably, the censorship of homosexual content in web series and physical book publishing is tighter than that in webtoon. Such variations lead to the consciousness and cautiousness of queer media content producers to act tacitly when publishing homosexual content unfolding in different formats on different platforms.

Creating queer content through transmedia practices in contemporary Chinese popular cultural industry

Despite the abovementioned multilayered regulatory constraints on queer product creation and publication, the past decade has witnessed a surge in commercial queer content, particularly BL-adapted web series in the Chinese cultural market. Additionally, emerging women-centred TV programmes, like double-female-leads dramas and woman-group reality shows, provide fertile ground for audiences to interpret GL potentials and intimacies within such content through queer reading (Yang Citation2023; Zhao Citation2024b; Zhao and Ng Citation2022). However, GL-themed cultural products have remained peripheral and have been scantly discussed in queer Chinese media studies.

In the 21st century, East Asia became a major hub for transmedia storytelling (Jin Citation2020, 1). According to Jenkins (Citation2007), ‘storyworld’ in transmedia production means that this narrative universe is created by employing different media for different parts of the story, and none of a single part can give readers all the information needed to comprehend the whole story. Examining transmedia practices in the specific context of contemporary China, it has become a norm to adapt extremely popular, original web novels published on Chinese literary websites like Jinjiang wenxue cheng (Jinjiang Literature City, hereafter Jinjiang) into TV/web series since the 2010s (Gong and Yang Citation2017; Wang Citation2020), a phenomenon that has been called IP (intellectual property) adaptation, where IP primarily stands for the story created by web novel writers. Prior to this, TV dramas were mainly produced from original scripts or adaptations of serious literature. In comparison, IP adaptation can take advantage of the solid readership and fanbase accumulated by popular web novels, thereby more easily attracting liuliang (digital traffic data).

Current TV/web series with BL themes are primarily adapted from existing danmei novels. For example, in 2020, over 60 danmei novels from Jinjiang were purchased for live-action adaptation (Hao and Baecker Citation2021). Since the homoerotic content in BL novels may run the risk of being censored by authorities, copyright holders like platforms or producers need to alter the original plots and reshape the romantic relationships between characters into other forms (e.g. brotherhood), which gives rise to the genre of dan’gai or BL adaptation (Ye Citation2023, 1594). Over the last decade, there have been remarkable dan’gai web series achieving smashing success in the domestic and global markets, such as Zhen Hun (Guardian, 2018), Chen Qing Ling (The Untamed, 2019) and Shan He Ling (Word of Honor, 2021). Normally featuring pop idols as the two male leading characters, dan’gai web series can ‘[attract] BL fans and pop idol fans with the potential to expand to mainstream viewership, [and] would predictably become a profitable model for the entertainment industry’ (Lei Citation2023, 111).

Following the popularity of danmei in the second half of the 2000s, GL literature started to blossom in the Chinese online space, but Chinese GL literature has remained at a lower level of visibility and popularity when compared with its BL counterpart (Zhao and Ng Citation2022, 303), nor have GL web series been widely produced or adapted from existing GL web novels in mainland China in recent years. Currently, there have rarely been any scholarly discussions on why GL-adapted web series remain a minor presence in the market. One possible economic factor may be the fact that there are no extremely successful GL IPs on Chinese literary websites, so investors and producers do not want to run the risk of unsuccessful investment and dismal reception. Due to the government’s ‘Jingwang Xingdong’ [Cleaning up the Internet campaign] launched in 2014, Jinjiang restructured its website by renaming the danmei section into ‘chun’ai xiaoshuo’ [pure love novels] (Xiao Citation2015), which now publish both danmei (but are labelled as chun’ai), and baihe titles. For example, by April 2024, in the Zongfen bang [total score rankings] of chun’ai xiaoshuo, there had been only three baihe titles among the top 200, and the rest were all chun’ai/danmei titles (Jinjiang Citationn.d.). In addition, the anti-homosexuality and anti-pornography campaigns implemented by the state in recent years have mainly targeted BL literary and media products (XinhuaNet Citation2021; Yi Citation2021), which illustrates again that BL has been considered the primary representation of homosexuality and queer popular culture in mainstream Chinese society. Another possible factor from the sociocultural and ideological aspect contributing to GL media receiving scare attention in comparison to BL is ‘the deep-seated sociocultural trivialization (as well as a subsequent scholarly devaluation) of women’s non-heterosexuality as fleeting, nonthreatening moments to heteropatriarchal social systems’ (J. J. Zhao Citation2024a, 1).

Unlike many transmedia stories (e.g. the BL IP adaptations) where the narrative typically originates from a single source like a novel, the creation of CM storyworld operates in a reverse way: the web series is the master text and the webtoon and novel were adapted from it. In line with Jenkins’ conceptualization of transmedia storytelling, CM’s story has been adapted, developed and expanded in a unified way across these media formats, offering varied experiences and perspectives within the same narrative universe. However, CM’s distinct approach also shows the localization of Jenkins’ transmedia storytelling in a highly centralized sociopolitical environment, where both state ideology and economic interests influence its storytelling techniques and media choices.

In addition to these official products and adaptations, CM’s transmedia storytelling is also attributed to fans’ participation in a way that they ‘create their own versions of what happened or what they believe could happen within the constraints of both the storyworld as well as the fandom itself’ (Donald, Austin, and Resuloğlu Citation2018). Given that both ‘the commercial and grassroots [i.e. fans] expansion of narrative universes’ (Jenkins Citation2010, 948) contribute to transmedia storytelling, we use ‘GL narrative’ to refer to the female–female intimacy narrated in stories created by both commercial producers and fans within CM’s transmedia storyworld. As such, we align our argument with the idea that transmedia storytelling is a result of convergence, taking it as ‘both a top-down corporate-driven process and a bottom-up consumer-driven process’ (Jenkins and Deuze Citation2008, 6).

Although fan participation is valued in transmedia storytelling, it is not hard to imagine or find examples where the stories created by fans are different or even contradictory to each other, a dissonant phenomenon against Jenkins’ idea that transmedia storytelling produces unified and coherent entertainment experiences. Noticing this problem, Ryan (Citation2015) reminds us that fan artefacts, like fan fiction, are a type of ‘by-product rather than a core constituent of transmedia storytelling’ (11), highlighting the central role of the official texts in transmedia storytelling. In addition, while CM’s three commercial media formats are central to the integrity of its storyworld, fans do not necessarily need to encounter all of them to immerse themselves within the CM storyworld. However, if fans are willing to appreciate CM across media, they can find specific details or pieces about the storyworld which are not narrated in all media formats. As will be presented in the following analysis, GL features are not presented in the three media formats in the same manner. Instead, fans need to ‘collect’ and ‘acquire’ (Ryan Citation2015, 4) various GL-featured information in their transmedial journey given the compensating relationship between CM’s multiple mediums.

Transmedia storytelling in CM: a holistic analysis of the web series, novel and webtoon

The CM story is set in an alternate Shanghai in the early Republican era (1912–1949). It depicts the encounter, mutual support and emotional bond between Xu Youyi, a successful and kind-hearted writer, and Yan Wei, a mercenary in disguise as the owner of a photography studio. Xu lives a seemingly perfect life until she discovers the affair between her husband and her best friend. Xu is portrayed as an independent and clear-headed female character with innate strength. She insists on divorcing her husband and refuses to live an arranged life full of deceit, even though she is pregnant and faces threats from her father-in-law. As for Yan, she has had a traumatic childhood and has been trained as a mercenary, but she wants to live an ordinary life. In the process of surviving the turbulent dangers surrounding them, they get closer, supporting and saving each other.

As previously discussed, the censorship of queer content varies across web series, novels and webtoons, with webtoons enjoying more flexibility and freedom than the other two. The following paratextual and textual analysis resolves around to what extent each medium is effective in explicitly presenting the GL elements in CM, considering the multilayered censorship and the affordance of each medium. Since the script of the web series is the origin of the CM storyworld and has been adapted to the novel, we will first analyse the interactions and differences between these two. This will help us understand how each medium navigates censorship and leverages its strengths to convey the GL narrative.

The CM web series was co-produced by Huanyu Entertainment, ‘the trendsetters in Chinese BL industry’ (Krishnanaidu88 Citation2021), and Bilibili. Though the CM web series was launched on 12 August 2021, its preheat of airing started a year before that, when CM’s official Weibo account posted its first Weibo on 18 June 2020. This post briefly described the relationship between the two female characters as always saving each other despite quarrelling, relying on each other like the closest friends and becoming mirror images of each other (Dianshijü Shuangjing Citation2020). This post apparently whetted audiences’ appetites, as audiences’ comments below the post asked questions such as when and where it would be released and whether it depicted shehui zhuyi jiemeiqing (socialist sisterhood)Footnote3 or baihe. In addition, the title of the web series, Couple of Mirrors, also leaves audiences with an imaginative association with ‘mojing [mirror rubbing]’, which is used to indicate female same-sex eroticism in premodern Chinese literature and history records (ifeng movie Citation2021). As for the novel, on its introductory webpage on Douban (a media review and social networking platform), the blurbs state that Xu and Yan are ‘guimi’ (best friends), their relationship is ‘shehui zhuyi jiemeiqing’ (socialist sisterhood), and the web series is ‘baihe zhiguang’ [the glory of baihe] (Douban Citationn.d.). It is evident that these paratexts do not explicitly frame the Xu/Yan relationship as romantic love but rather make it fall into the spectrum between the homosocial and the homoerotic.

In terms of the textual presentation of queerness, the novel’s main plots are more or less the same as those of the web series, except for the explicitness of depicting Xu/Yan intimacy and romantic chemistry. The novel contains more descriptions of Xu’s and Yan’s inner thoughts and interpretations of the reasons for their behaviour from an omniscient third-person point of view, which are not easy to capture in the visual presentation in the web series. In addition, there are more explicit descriptions of their intimate bodily gestures, such as holding each other’s hands, making micro-facial expressions and the increase of their emotional bond in the novel. For example, at the end of Chapter 38,Footnote4 after saving Yan from the court, Xu, holding hands with Yan, goes back to Yan’s photography studio together, and for the first time, she knows so clearly where she is going and who she wants to live happily with. When they are standing in front of the door of the studio, Xu, holding Yan’s hands, looks at her and says ‘Yan Wei, welcome home’. Yan smiles and replies, ‘Why does it look like your home? Isn’t this my home?’ Xu curls her lips, smiles and says, ‘It will be ours from now on’. Yan looks at Xu deeply for a long time, raises her hand and flicks Xu’s forehead lightly, and agrees ‘Okay, our home’ (Zhao and Li Citation2021, 360–361). This scene, however, was not included in the web series. Even though the novel contains more hints at GL elements than the web series, their relationship portrayed in the CM web series and novel is more like that of the double-female-leads drama. In other words, readers/audiences need to interpret the subtle female intimacy through queer reading of the subtexts.

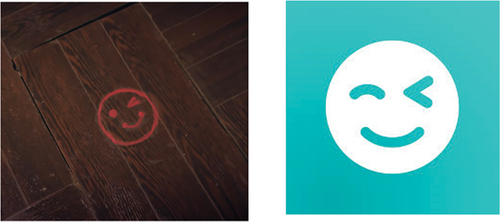

In contrast, the CM webtoon is undoubtedly an explicit GL story. There are a lot of intimate physical touches (such as hugging, cuddling in bed, touching face, and kissing face and forehead), dialogues expressing the affection between the two, and monologues of Yan expressing her admiration, affection and care for Xu. When watching these scenes, audiences normally use the danmu (bullet-screen comment) function on Kuaikan to express their excitement, saying ‘Guxiang de baihehua kaile’ [The lilies in my hometown are blooming] or ‘Wo tongyi zhemen hunshi’ [I agree to this marriage] (see ). Most importantly, there are plots of their self-discovery of love for each other, their doubts about what kind of relationship they are in, and the final confirmation of their mutual love.

Figure 1. A screenshot of an explosion of danmu posted to CM Chapter 2 on Kuaikan, taken by the authors on 3 April 2024. This chapter is publicly available on the Kuaikan app.

To be specific, in Chapter 41 of the webtoon, Yan asks herself, ‘Are my feelings for Xu Youyi really just friends? She had a boyfriend and was married … is it possible?’. In Chapter 42, Xu also asks herself, ‘Is this really just a simple friendship?’ She persuades herself that, as a woman of a new era, there is no need to get entangled in the secular definition of a relationship; she just needs to follow her heart. In Chapter 46, they finally confirm their love for each other. Xu bravely kisses Yan’s face, and they kiss each other emotionally. In Chapter 47, Xu first states her love, saying, ‘Weiwei, I love you’, and Yan replies, ‘I … I love you, too’. In Chapter 54, they discuss using the Chinese characters in their names to name the baby that Xu bears with her ex-husband. After that, they kiss emotionally. All of these scenes are exclusive to the webtoon. The danmu posted on these scenes also resonate with the idea that the webtoon presented more explicit GL plots and scenes than the web series.

When examining the CM storyworld, it is essential to consider the webtoon, novel and web series together as a whole rather than seeing them separately, as they complement and compensate for each other in expanding and enhancing the GL narrative. We are not suggesting that readers must consume all three products to fully engage with the GL narrative within CM’s transmedia story, but the interplay among these mediums under varying degrees of content control in the Chinese queer popular cultural market contributes to a more explicit and effective GL-themed storyworld for CM.

Fans’ digital and affective participation in co-constructing the GL narrative

In addition to the compensatory relationship between the three media formats, the creation and expansion of CM’s GL storyworld have also benefited from fans’ digital and affective participation and contribution. CP fansFootnote5 (aka shippers) and web series fans explicitise the absent GL attributes on the web series and the novel through their subjective interpretations and intertextual references, share their queer readings in online fan communities, and produce fan fictions, pictures or videos to grant CM ‘afterlives’ and lasting influence.

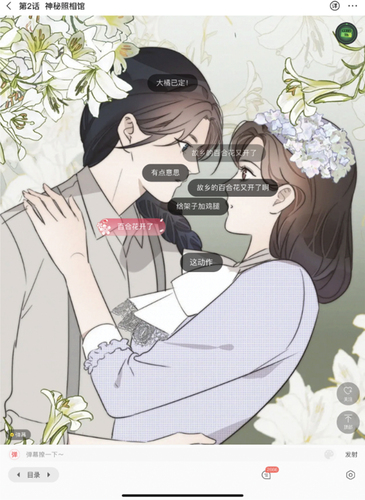

The Weibo chaohua [Weibo super topics] is an influential platform to form online fan communities. Regarding the CM web series, the Xu/Yan CP had more than 16 thousand members in its CP chaohua by the end of March 2024. The official name for these CP fans is ‘hao xifan’, literally means ‘good porridge’, as what Xu cooked for Yan for the first time was porridge; it is also a homophone to ‘like sth./sb. very much’. CP fans’ affective and digital participation plays an important role in interpreting, reinforcing and explicitising the GL features in CM’s transmedia storyworld. For example, in episode 9 (between 7:47 – 8:20) of the web series, when Xu is decorating Yan’s bedroom, she notices a bump on the floor, so she uses her lipstick to draw a smiley blink on it. Some fans pointed out that this smiling face looked similar to the logo of the lesbian dating app Rela (as shown in ), joking that Xu is actually the real founder of Rela. Although this scene is included in Chapter 31 of the novel, the written text only says that this smiling face looks like it was drawn by a primary school student. It does not allow much space for visual connections, so the queer intertextuality to the app Rela cannot be established. However, this scene is not included in the webtoon. We deduce that this could be due to the webtoon’s inclusiveness and tendency to make explicit and direct presentations of the GL narrative, which may not need the incorporation of subtle GL-relevant hints and signs. In contrast, the web series and novel rely heavily on such subtexts and fans’ queer reading to construct GL potentials within the storyworld.

The screenshot of the smiley blink in CM episode 9 (8:18) (https://youtu.be/ErNQABOkj2k?si=GEXswhrhQ-GAx1cv) was taken by the authors on 3 April 2024. All of CM episodes are publicly available on YouTube.

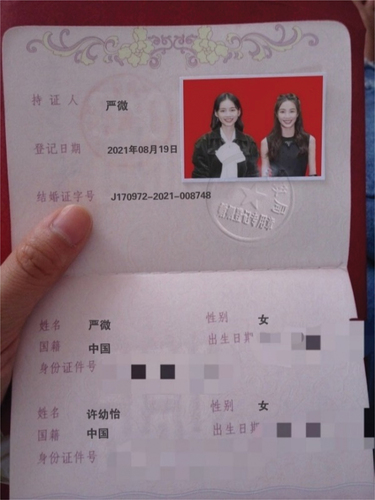

One of the popular themes that CP fans emphasize in their user-generated content in chaohua is the narrative of love, marriage and family between Xu and Yan. As shown in , Yan stands seriously behind the happily smiling Xu, holding a copy of the marriage certificate in her hand. This figure is recreated by fans from a scene in the last episode of the web series where Yan is actually holding a copy of Xu’s freshly published book. is a marriage certificate forged by a CP fan for Xu and Yan. It indicates a story proactively created by fans, but differs from the official story written by producers, thereby further indicating the collective authorship of CM’s transmedia storytelling where fans compensate the explicit GL narrative for its ‘unspeakable’ characteristic in the web series and the novel. Moreover, the abundant narratives on Xu/Yan love and marriage indicate not only CP fans’ enthusiasm for shipping this CP but also their potential yearning for same-sex marriage, which is not legally approved and protected in mainland China.

Figure 3. Posted by Yuchouyedengji on 19 September 2021 (https://weibo.com/5630001458/KyUlyEMko). This post is publicly available.

Figure 4. Posted by SOIYllllll on 19 August 2021 (https://weibo.com/7620720238/Kubzrg8Cu). This post is publicly available.

It is acknowledged that GL remains a sensitive theme or genre in the Chinese media environment, which is constrained from explicit expression and depiction in many cases. The CM producing team employed a more conservative storytelling strategy to disguise the Xu/Yan relationship as homosocial bonding in the web series, rendering it in general a suspense drama rather than a GL drama in the Chinese market. This approach is compatible with the prevalent heteronormative ideology in mainstream Chinese society, facilitating its acceptance by the general public. The CM novel, unlike the prevailing practice of publishing BL texts serially online in China, was published directly in printed form. This deviation from the norm may be attributed to the fact that it was adapted from the script of the web series, and the producing team did not see the need to publish it serially online beforehand to accumulate readership, especially when the webtoon had been published in instalments online. To navigate state censorship and obtain an ISBN, the novel contains a more opaque depiction of GL themes, probably due to self-censorship by the authors and publisher. The webtoon and fans’ creative activities serve to compensate for the absence of GL romantic love and intimate scenes in the web series and novel. This transmedia convergence of CM is more like a test of waters by the producing team to see if GL story is able to achieve success in the Chinese media industry. It is not necessarily related to queer identity construction or social formation but rather reflects a co-producing model of cultural commodity under the negotiation between Chinese popular culture, digital technologies, heteropatriarchal ideologies and governmental censorship and regulations.

Conclusion

In the face of intricate sociopolitical and sociocultural environments, GL content continues to occupy a marginalized position in mainland China. This is attributed not only to the tightening official regulations on queer media content production and dissemination but also the imbalanced marketing emphasis on BL content in the Chinese entertainment industry. GL media products are characterized by their scarcity and limited visibility, resulting in disproportionate attention and discussion compared to BL and dan’gai, from general audiences, industry and academia.

Recognizing the challenging contexts for creating GL narratives in mainland China, this article has investigated GL narrative production in the CM transmedia storytelling in the Chinese media market. By consulting official policies and regulations on queer content production, we initially found that the censorship implementations vary in audiovisual, online, and printed products. Notably, the webtoon format possesses greater freedom and space for queer narrative construction than printed books and web series. While GL narratives may not be overtly present in the latter two products, fan audiences and readers adeptly employ queer readings to derive GL interpretations. Moreover, through paratexts, the webtoon and fans’ user-generated contents, the hidden GL spirit within the web series and book has been compensated, culminating in a special media spectacle where the Chinese fan audiences and readers engage with the GL narrative within CM in a transmedial journey. In a time and space where commercial queer content is facing regulations on varying degrees, utilizing the compensating relationships involved in transmedia storytelling becomes a tactical strategy – an unconfrontational but effective means – to detour around governmental regulations while successfully explitising, expanding and disseminating GL information within Chinese society.

It should also be noted although Jenkins’ concept of transmedia storytelling has deeply affected global fan studies and digital narrative studies, it ‘is still closely associated with […] global media giants […] such as Disney and Time-Warner’ (Freeman and Gambarato Citation2019, 2). Representative cases like The Matrix and Harry Potter often come from contexts where commercial and grassroots producers have a relatively larger space to perform their creative agency without too many constraints or limitations. In this context, the case of CM echoes Filippo Gilardi’s and Celia Lam’s call that ‘[f]urther transmedia research should, therefore, depart from Jenkins’ canonic and entertainment-centred concept and explore the peripheries’ (Gilardi and Celia Citation2021, 308).

In addition, within the broader realm of queer media content production, the spotlight often falls on BL, both within and beyond China. While emphasizing the importance of amplifying queer visibility in media products to facilitate social transformation and gender power redistribution, it is imperative to acknowledge the imbalance in narrative creation concerning various sexual and gender groups. At the time when we celebrate the progress brought about by BL narratives in producing and disseminating queer knowledge to the public, there is a pressing need to direct increased attention to producing and disseminating narratives and storyworlds in association with other peripheral social groups. This will be vital for achieving diverse gender representations and a heteroglossic society online and offline.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our thanks to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank Hanyu Wang for reading the earlier draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. All the Chinese names in this article are listed with surnames first, followed by given names.

2. All the English translations in the square brackets are the authors’ translations.

3. ‘Socialist sisterhood’ is normally used by Chinese fans to talk about female same-sex relationship, in the sense of what its male counterpart ‘socialist brotherhood’ has indicated. The latter is defined as ‘a moniker developed by fans for male-male romance in dramas under the pressure of censorship … while being aware of the romantic subtext of the storyline’ (Ng and Li Citation2020, 486).

4. All of the dialogues, monologues and plots in the textual analysis of the novel and webtoon were translated from Chinese to English by the authors.

5. CP fandom, ‘which may be interpreted as character pairing fandom in English, is a rising type of fan culture on the Chinese internet in the 21st century. CP fans are defined by their imaginations about romantic relationships between real-life or fictional figures, and a pairing of figures is called a CP’ (Zhang Citation2019, ii).

References

- Dianshijü Shuangjing. 2020. “#电视剧双镜# #双镜# 永远争执不休,却依然互相拯救;成为镜中彼此,相互依偎,如同最亲密的朋友。许幼怡@张楠zz 严微@孙伊涵Annie.” Weibo. Accessed June 18. https://weibo.com/7470291196/J7b1IEcGp.

- Donald, Iain, Hailey J. Austin, and Filiz Resuloğlu. 2018. “Playing with the Dead: Transmedia Narratives and the Walking Dead Games.” In Handbook of Research on Transmedia Storytelling and Narrative Strategies, edited by Recep Yılmaz and M. Nur Erdem, 50–71. Hershey: IGI Global.

- Douban. n.d. Couple of Mirrors Novel. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://book.douban.com/subject/35442688/.

- Freeman, Matthew, and Renira Rampazzo Gambarato. 2019. “Introduction.” In The Routledge Companion to Transmedia Studies, edited by Matthew Freeman and Renira Rampazzo Gambarato, 1–12. New York: Routledge.

- Gilardi, Filippo, and Lam. Celia. 2021. “Conclusion.” In Transmedia in Asia and the Pacific: Industry, Practice and Transcultural Dialogues, edited by Filippo Gilardi and Celia Lam, 307–312. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gong, Haomin, and Xin Yang. 2017. Reconfiguring Class, Gender, Ethnicity and Ethics in Chinese Internet Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hao, Yucong, and Angie Baecker. 2021. “The Rise of boys’ Love Drama in China.” East Asia Forum Quarterly 13. 2. https://eastasiaforum.org/2021/07/08/the-rise-of-boys-love-drama-in-china/.

- ifeng movie. 2021 “Couple of Mirrors: In the absence of dan’gai 101, the poor GL drama is testing the waters again《双镜:耽改101缺席的日子,贫穷的百合剧又来试水了.”ifeng. Accessed August 18, 2021.ht tps://doi.org/i.ifeng.com/c/88nj2rtpcw6.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2007. “Transmedia Storytelling 101.” Henry Jenkins. Pop Junctions: Reflections on Entertainment, Pop Culture, Activism, Media Literacy, Fandom and More. March 21, 2007. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2007/03/transmedia_storytelling_101.html.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2010. “Transmedia Storytelling and Entertainment: An Annotated Syllabus.” CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 24 (6): 943–958. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2010.510599.

- Jenkins, Henry, and Mark Deuze. 2008. “Editorial: Convergence Culture.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14 (1): 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856507084415.

- Jin, Dal Yong. 2020. “East Asian Transmedia Storytelling in the Age of Digital Media — Introduction.” In Transmedia Storytelling in East Asia: The Age of Digital Media, edited by Dal Yong Jin, 1–12. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jinjiang. n.d. Pure Love Novel Total Score Ranking晋江纯爱小说总分榜. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.jjwxc.net/topten.php?orderstr=7&t=1.

- Krishnanaidu88. 2021. “Couple of Mirrors’ series review (Ep.7 to 12).” The BL Xpress. AccessedSeptember 18. https://theblxpress.wordpress.com/2021/09/18/couple-of-mirrors-series-review-ep-7-to-12/.

- Lei, Jun. 2023. “Taming the Untamed: Politics and Gender in BL-Adapted Web Dramas.” In Queer TV China: Televisual and Fannish Imaginaries of Gender, Sexuality, and Chineseness, edited by Jamie J. Zhao, 105–123. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Lin, Pin. 2018. “Baihe/GL/Lala/Lesbian.” In Keywords in Chinese Internet Subcultures, edited by Yanjun Shao and Yusu Wang, 203–207. Beijing: Life Bookstore publishing co.

- Ng, Eve., and Xiaomeng Li. 2020. “A Queer ‘Socialist Brotherhood’: The Guardian Web Series, Boys’ Love Fandom, and the Chinese State.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (4): 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1754627.

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2015. “Transmedia Storytelling: Industry Buzzword or New Narrative Experience?” Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies 7 (2): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.5250/storyworlds.7.2.0001.

- Sohu. 2019. Trial Measures for the Assessment and Evaluation of Social Benefits of Book Publishing Units. https://www.sohu.com/a/300543010_210950.

- The State Council, PRC. 2016. Regulations on the Management of Online Publishing Services网络出版服务管理规定. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-11/09/content_5724634.htm.

- Wang, W. Michelle. 2020. “Screen to Screen: Adaptation and Transnational Circulation of Chinese (Web) Novels for Television.” In Media Culture in Transnational Asia: Convergences and Divergences, edited by Hyesu Park, 72–93. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Xiao, Yingxuan. 2015. “Jinjiang Website Director (ID: Iceheart) Answering Questions from Peking University Teachers and students女频周报副刊|晋江站长冰心答北大师生问.” Mei Houtai. May 15, 2015. https://reurl.cc/A4E4aQ.

- XinhuaNet. 2017 “General Rules for Content Review of Online Audiovisual Programs released《网络视听节目内容审核通则》发布.” Accessed July 1. http://www.xinhuanet.com/zgjx/2017-07/01/c_136409024.htm.

- XinhuaNet. 2018. “The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China Issued the Plans for Deepening the Reform of the Party and State Institutions (Full Text)中共中央印发《深化党和国家机构改革方案》(全文).” AccessedMarch 21. http://www.xinhuanet.com//zgjx/2018-03/21/c_137054755.htm.

- XinhuaNet. 2021. “NRTA: Resolutely Resist the Trend of Dan’gai and Other Pan-Entertainment Phenomena 广电总局: 坚决抵制“耽改”之风等泛娱乐化现象.”Accessed September 17. http://www.news.cn/2021-09/17/c_1127870884.htm.

- Yang, Fan. 2023. “The Matrices of Female Bonding and Lesbian Sexuality: Female Homoerotic Cinema in Mainland China.” Feminist Media Studies 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2023.2297164.

- Ye, Shana. 2023. “Word of Honor and Brand Homonationalism with ‘Chinese Characteristics’: The Dan’gai Industry, Queer Masculinity and the ‘Opacity’ of the State.” Feminist Media Studies 23 (4): 1593–1609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2037007.

- Yeung, Ka Yi. 2017. Alternative Sexualities/Intimacies? Yuri Fans Community in the Chinese Context.” Master’s thesis, Lingnan University. https://commons.ln.edu.hk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=soc_etd.

- Yi, Jun. 2021. “Be Wary of Dan’gai Dramas Leading Public Aesthetics Astray 警惕耽改剧把大众审美带入歧途.” Guangming Daily. August 26, 2021. https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2021-08/26/nw.D110000gmrb_20210826_4-02.htm.

- Zhang, Kaixuan. 2019. “A Semiotic Study of Character Pairing Fandom in Chinese Cyberspace.” PhD diss, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://repository.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/sc/item/cuhk-2399258.

- Zhao, Jamie J. 2022. “Queer Chinese Media and Pop Culture.” Oxford Research Encyclopedias. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1213.

- Zhao, Jamie J. 2024a. “The ‘Aroma of citrus’ as Transnational Queer Digital Culture: Girls’ Love Webtoons in Contemporary China.” Communication Culture & Critique:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcae005.

- Zhao, Jamie J. 2024b. “From ‘Kill This Love’ to ‘Cue Ji’s Love’: The Convergence of Queer, Feminist and Global TV Cultures in China.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 45 (2): 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2023.2232317.

- Zhao, Jamie J., and Eve Ng. 2022. “Introduction: Centering Women on Post-2010 Chinese TV.” Communication Culture & Critique 15 (3): 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcac029.

- Zhao, Jamie J., Ling Yang, and Lavin. Maud. 2017. “Introduction.” In Boys’ Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols: Queer Fan Cultures in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, edited by Maud Lavin, Ling Yang, and Jamie Jing Zhao, xi–xxxiii. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Zhao, Na, and Zongchen Li. 2021. Shuang Jing. Chengdu: Sichuan Literature and Art Publishing House.