Abstract

For the 1965 Melbourne Cup Carnival, chemical giant DuPont de Nemours Inc. brought English model Jean Shrimpton to Australia to model youth fashion in Orlon, a synthetic fibre marketed as a wool substitute. By contrast, fibre rival, the Australian Wool Board, sponsored French model Christine Borge’s appearance in traditional racewear in wool. Utilising a ‘new materialist’ lens, this article revisits the well-known story of Shrimpton’s Melbourne appearances while highlighting a lesser-known aspect – the performative clash between the models and the fibres that serves as a case study into marketing fibres and styles in 1960s Australia. I argue that cultural and economic forces powerfully melded through novel cross-promotions and sponsorship arrangements between Victoria Racing Club and fibre producers in the service of capitalism. This article also examines marketing’s co-optation of youth culture to promote synthetic fibres and new fashion and to encourage the pursuit of individuality in dress and comportment.

On 30 October 1965, young, high-profile, English photographic model, Jean Shrimpton, jetted into Melbourne. The twenty-two-year-old’s assignment was to promote Orlon, a synthetic substitute for wool produced by multinational chemical giant E. I. DuPont de Nemours Inc. (DuPont). Sporting the now-iconic Orlon mini-dress, Shrimpton traversed the tarmac in step with her boyfriend, English actor Terence Stamp. (). The pair, dubbed ‘London’s most gorgeous couple’, touched down on Derby Day, the first day of the week-long Melbourne Cup Carnival (hereafter the Cup Carnival). They arrived a day later than expected, and DuPont representatives hastily bundled them into a waiting vehicle bound directly for the Derby Day meeting already underway at Flemington Racecourse.Footnote1 What transpired when the entourage entered Flemington’s Members’ Enclosure has become legendary.

Figure 1. Jean Shrimpton and Terence Stamp arrive at Melbourne’s Essendon Airport. Published in The Age, 31 October 1965. ID. FXT74625. © Fairfax Media. Image reproduced with the permission of Fairfax Media.

However, if the clock is wound back five days, a different story emerges. On 25 October 1965, after disembarking the last leg of a flight from Paris, French fashion model Christine Borge fainted onto that same tarmac.Footnote2 As television and print media cameras devoured the incident, a ‘dark and handsome’ employee of Borge’s sponsors, the Australian Wool Board (hereafter the Wool Board), ran to the aid of the stricken woman and chivalrously carried her into the terminal ().Footnote3 As with Shrimpton, the purpose of Borge’s visit to Australia was also business-related. Her task was to promote wool, Australia’s traditional fibre of choice. Synthetic fibres, the so-called miracles of science, had flooded the local textile market throughout the 1950s and 1960s and the Wool Board sought to remind Australians of the superior qualities of the home-grown natural product.Footnote4 Borge was to model French haute couture in fine Australian wool over the days of the Cup Carnival and present the prizes for the Fashions on the Field Competition alongside Shrimpton.Footnote5

Figure 2. Australian Wool Board’s Tony Lewis carries Christine Borge at Melbourne’s Essendon Airport. Published in The Age, 26 October 1965. ID. FXB1430081 © Fairfax Photographic. Image reproduced with the permission of Fairfax Photographic.

Shrimpton’s appearance on Derby Day embodied the cutting-edge, youth-influenced look of ‘Swinging London’ fashion and has become immortalised in the Australian popular collective memory. Fashion historians credit Shrimpton with triggering a shift in style that saw ‘youthquake’ fashions from the northern hemisphere sweep Australia.Footnote6 Others, such as Sylvia Harrison, have viewed this moment as a vector of transnational social and cultural influences on 1960s Australian youth, and specifically, of new ideas around young women’s identity and societal roles. Shrimpton’s unfettered youthful style and non-conformist comportment have been read as impetus for Australia’s youth to embrace ideas of social change that ran deeper than sartorial style alone.Footnote7 Without wishing to diminish the significance of popular culture in histories of the 1960s, I argue that to understand this period we must attend also to the economic forces grounding cultural change.

Reliance on analyses of the popular media coverage and popular culture images alone leads inevitably to a simplified view of the 1960s. Neglecting the link between the global economy and culture reduces the decade to one driven by youthful rebellion and feminist activism or, in the case of teen girls, what Lesley Johnson calls the open-ended project of feminine self-determination.Footnote8 While interrogating the ideologies and desires to emerge from 1960s popular youth culture, historians Robin Gerster and Jan Bassett miss an opportunity to contextualise these with the broader Australian experience of a decade that was marked by rampant consumerism and shaped by both economic and technological change.Footnote9 Analysing cultural change throughout the global Cold War, American historian Louis Menand ably reconnects the cultural and economic drivers of his case studies by unpacking such change through a ‘series of vertical cross-sections’.Footnote10 He slices through accounts of the events and ideas representative of everyday life and exposes the moving parts of ‘the economic, geopolitical, demographic and technological’ forces that underpin them.Footnote11 In popular representations of the 1965 Melbourne Cup, the separation of the cultural story from its economic roots has concealed the powerful role of market-driven forces in which the producers and sellers of wool and synthetics were key players. Thus Shrimpton has been disproportionately credited with more personal agency than her sponsors.

This article revisits the Shrimpton story through a ‘new materialist’ lens to provide a fresh interpretation of this well-known cultural history. New materialism offers another way of looking at the 1960s, reading newspapers, magazines and memoir, the sources typical of social and cultural history, in conjunction with hitherto under-utilised archival materials such as trade journals, and the Victoria Racing Club’s committee minutes and 1999 oral history project on Fashions on the Field. It will be shown that Christine Borge’s Melbourne appearances and the performative clash that occurred between the two models was an integral part of the narrative – one that has been overlooked in existing scholarship as well as forgotten in public memory. Restoring Borge to the frame reveals a larger economic story of commercial rivalry between the competing producers of the natural and synthetic fibres that the two women represented. Thus, professional competitiveness between the models combined with efforts to arrest declining attendance at the races and innovative methods of marketing and cross-promoting through the media, including the important new medium of television. Cultural and economic forces powerfully melded at Flemington in 1965 in the service of capitalism that co-opted youth culture to promote synthetic fibres, create desire for new youth fashion, and encourage the idea of expressing new kinds of individuality in dress and style.

Calling attention to ‘the material’ in cultural histories, Hannah Forsyth and Sophie Loy-Wilson, amongst others, have pointed to the agency of ‘things’ in shaping the past.Footnote12 Others such as Anneke Smelik have championed a similarly interdisciplinary theoretical framework in the study of fashion and culture, arguing that cultural objects are embedded in networks of ‘human and non-human actors’ and are linked also into ‘the world of production and consumption’.Footnote13 British historian Kate Smith refers to this as local ‘social entanglements and relationships’ that are subject to what New Zealand scholar Toni Ingram calls non-human ‘material-affective forces’, often missing from histories of capitalism.Footnote14 Examining the entangling of the models, their sponsors, the Victoria Racing Club (hereafter VRC) and the fibres, as ‘things’, enables us better to understand fashion’s influence on both business and culture in 1960s Australia.

The Shrimpton-Borge story needs to be told as part of an economic subplot of cross-promotional publicity efforts by the VRC.Footnote15 Although fashion historians have described horse-racing events as sites of spectacle and traced their connection to fashion, they have paid little attention to marketing and cross-promotional activities.Footnote16 Building on the longstanding symbiosis between horse racing and fashion, the VRC sought to enhance the Cup Carnival spectacle with sponsorships and product cross-promotions through a novel initiative, ‘Fashions on the Field’. The VRC’s goal was to reverse flagging attendance by enticing more race-goers, particularly women, to the races to raise the Cup Carnival’s appeal as an event for a ‘family outing’, thus ensuring its longevity as a leisure activity in an increasingly affluent society.Footnote17 Due to the work of intermediaries such as models, marketers, fibre producers and the media, the lawns of Flemington Racecourse became a space (not unlike the airport tarmac) where the spectacle of fashion and style was commodified for the mutual economic benefit of the VRC and its sponsors. The efforts of the VRC would be further enhanced by rivalry for market share between two contemporary fibre producers, DuPont and the Wool Board. To omit Borge from the story is to conceal the VRC’s strategy. The Shrimpton-Borge clash was a snapshot of social, cultural and economic change in motion.

In the next section I explore the generation and manipulation of media publicity around the two models’ appearances at the Cup Carnival. Then I consider the rivalry between the fibre producers sponsoring each model. In the final section, I present a fresh new materialist interpretation of a well-known story of Australia’s 1960s through the VRC’s ‘Fashions on the Field’ initiative and bring Shrimpton into better focus as having agency in the world of ‘things’ in addition to her ability to shape taste as a cultural icon.

‘No such thing as bad publicity’

The Members’ Enclosure at Flemington Racecourse, with dress standards rivalling those of England’s Royal Ascot, was the domain of Melbourne’s wealthy social elite. It epitomised the ideal of respectable elegance that informed the way Australian women dressed; wearing hats, gloves and stockings was de rigueur in 1960s polite society, no more so than at the races.Footnote18 Shrimpton’s casual comportment shocked and outraged many in attendance – some were incensed by the amount of bare thigh revealed below her hemline while others perceived her lack of formality, of decorum and of the appropriate accessories (hat and gloves) to be the greater transgression.Footnote19 In this traditional space of conspicuous consumption, the perceived inexpensiveness of Shrimpton’s simple outfit also stood out sharply against other expensively, but conservatively, dressed and coiffed women. The national media widely covered the hostile reaction among fellow race-goers to Shrimpton’s appearance on Derby Day. In a front-page report in Melbourne’s Sun, journalist Barrie Watts sardonically captured the mood on the ground by suggesting, ‘If the skies had rained acid not a well-dressed woman there would have given The Shrimp an umbrella’.Footnote20 Nevertheless, other media suggested that the wider community included supporters of Shrimpton’s Derby Day wardrobe choices, with opinion loosely divided along gender and generational lines.Footnote21 Shrimpton was a celebrity: she had begun modelling in 1960, aged seventeen, appearing on the covers of magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. News of her antipathetic Melbourne reception reached the fashion capitals of the northern hemisphere and the story reinforced Melbourne’s reputation for snobbish intolerance of difference and its provincialism as a fashion backwater.Footnote22

Shrimpton is now remembered as the sole source of media controversy.Footnote23 However, at the time, newspapers and television news featured both her and Borge – Borge for the brouhaha she created at the airport and Shrimpton for her controversial attire and other perceived breaches of Flemington’s dress codes.Footnote24 While we have no evidence that Borge faked her airport fainting episode, her later comments hint that she may well have been seeking to snare pre-Cup limelight. In the days leading up to the Cup Carnival, journalist and commentator Keith Dunstan chauffeured Borge to many publicity events around Melbourne at the request of the Wool Board.Footnote25 Dunstan’s reporting of his time in Borge’s company – for the daily press, and in retrospect – gives credibility to the inference that the fainting spell was an opportunistic melodrama staged for the benefit of the media. For example, he advised readers of the Sun that Borge had been delighted to learn that her photograph featured on the paper’s front page on two consecutive days.Footnote26 However, the nationally-circulated images of Borge in the arms of her male rescuer depicted a ‘damsel in distress’ persona which, when contrasted with images of Shrimpton striding independently and purposefully from her aircraft, may have appeared quaint and passé to Australia’s young in the context of emerging 1960s feminist ideas.

Shrimpton’s arrival had been expected on the eve of Derby Day but due to her direction of travel from Los Angeles, confusion had arisen over time differences when crossing the International Dateline and she had missed a cocktail party that DuPont had arranged in her honour at Richard and Lillian Frank’s Melbourne restaurant.Footnote27 Over a decade later, Dunstan recalled that when Borge learnt of Shrimpton’s delay she ‘smiled a very feline smile [and] said silkily, “All right, I’d just like to know how the Shrimp is going to beat all the publicity I had”’.Footnote28 On the same evening, Borge appeared on Channel 9 Melbourne’s popular In Melbourne Tonight program, gathering more publicity for herself and for the woollen garments she was paid to promote.Footnote29 Combined with the fainting episode and other pre-Carnival publicity events, Borge had accrued considerable public awareness before Shrimpton had set foot on Australian soil.

However, media interest in Borge waned after Shrimpton’s memorable entrance to the Members’ Enclosure on Derby Day. DuPont’s Australian marketing manager, John Silverton, had escorted Shrimpton and Stamp through the packed Members’ Stand and recalls the moment when ‘all the noise suddenly ceased; it was deafening – the silence! People were horrified … we stopped … and then the press just descended like a hoard [sic]’.Footnote30 In the days of the Cup Carnival that followed, Borge faded in newsworthiness as the media fanned Melbourne’s polarised opinion over the appropriateness of Shrimpton’s Derby Day attire and comportment. What Borge modelled for the Wool Board continued to occupy media space on the fashion and social pages, but publicity given to Shrimpton’s perceived transgression of Flemington’s conventional dress standards, not least in the perceived cheapness of her synthetic attire, eclipsed Borge. Journalists tantalised the Australian public’s fascination with what some described as Shrimpton’s bad manners. As the controversy dogged her footsteps in Melbourne, aspects of her personal life including her relationship with Stamp became the subject of speculation.Footnote31

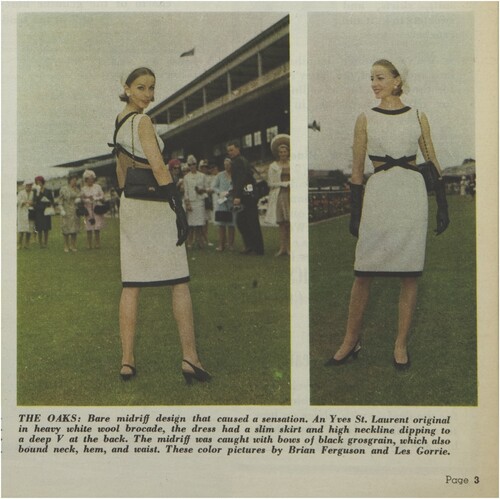

After a promising head start in the media stakes, Borge and wool fell behind Shrimpton and synthetic fibres. Wool scrambled to recover ground. On Oaks Day, Borge played what could be considered the trump card – ‘a bare back cutaway dress’ from Yves St Laurent.Footnote32 According to Australian Women’s Weekly’s fashion editor, the exposed back and midriff was a trackside sensation ().Footnote33 In modelling this dress, however, Borge created a promotional dilemma: how many customers who could afford it had the necessary body shape of youth?Footnote34 The actual market appeal of such haute couture was unclear. Although Melbourne’s Sun declared her overall attire superior to Shrimpton’s, Borge never recovered ground and is now largely forgotten.Footnote35 The publicity and notoriety that Shrimpton amassed in the now-famous shift dress overshadowed the elegant ‘damsel in distress’ persona that Borge had exuded initially and the later attempt to counter that image with sensational dressing ostensibly selected for youth market appeal.

Figure 3. Christine Borge modelling Yves St Laurent dress, Oaks Day, 1965. Published in The Australian Women’s Weekly, 17 November 1965. Image reproduced with the permission of ARE Media.

At the time, opinion within the DuPont team on managing Shrimpton’s publicity was also divided. Apparently aiming to mitigate expressions of antipathy towards Shrimpton (and what they saw as unfavourable press for the company), for the Cup Day race meeting itself, the Chairman of DuPont Australia’s Board insisted on the addition of hat, gloves and stockings to Shrimpton’s attire.Footnote36 Now dressed in a demure, sombre suit, more in keeping with conventional 1960s racing attire, Shrimpton was reportedly unhappy with this censure; sheltering in the grandstand and only mingling when necessary, she appeared to shun trackside attention.Footnote37 On the other hand, the executive head of the Clemenger agency, responsible for DuPont’s advertising campaigns in Australia, considered the fallout from Shrimpton’s controversial appearance at Derby Day a positive. ‘Leave her alone, this is absolutely sensational!’ John Clemenger advised DuPont.Footnote38 Following Clemenger’s intervention, by the following Oaks Day meeting Shrimpton had abandoned the hat and gloves provided by the wife of DuPont’s Chairman after Derby Day, but still sported stockings – perhaps more of a pragmatic response to cooler weather conditions than a capitulation to conservative pressures.Footnote39

Shrimpton’s memoir and many later interviews indicate that she nursed bruised feelings over the public criticism experienced in Melbourne. Upon completing the Australian assignment, she snubbed reporters and those gathered to witness her departure from Sydney Airport.Footnote40 Her failure to give a final interview or pause for photographers was deemed a further lack of good manners, causing additional public disenchantment.Footnote41 However, the passage of time was to reveal that, indeed, ‘there is no such thing as bad publicity’, as famously attributed to nineteenth-century American showman and entrepreneur P.T. Barnum. For it is the Shrimpton story, not Borge’s, that has endured and is now indelibly stamped in Australia’s collective memory.Footnote42 But what about the story of wool and synthetics that ran alongside their unequal success in securing a place in Australian media and memory?

Marketing fashionable fibres

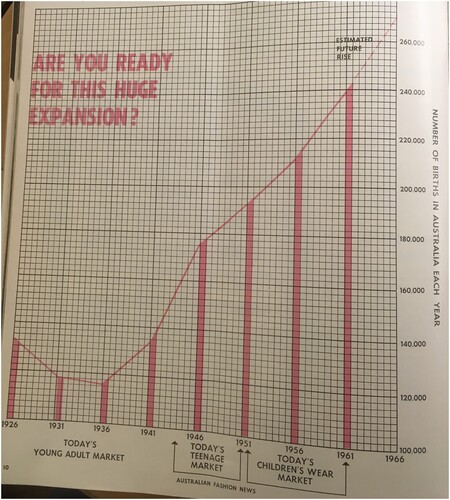

In relation to both quality and price, the two fibres pitted against each other via the story of these two women and their competing media profiles during the Cup Carnival sat at opposite ends of the fashion and fibre spectrum. The Wool Board had battled the incursion of synthetics into fibre markets since the interwar years when the first true polyester synthetic, Nylon, had been invented in an American DuPont laboratory. Then Britain, a major customer for Australian wool, supported investment in the further research and development of synthetics in the postwar period – no doubt an attempt to satisfy the imperative for textile self-sufficiency that the war years had highlighted.Footnote43 Initially an expensive product, synthetic fabrics’ global prices fell as production and competition among individual patented fibres increased throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s. As volume, popularity and consumer acceptance rose, synthetic prices further tumbled. Wool was not the only natural fibre to lose market share.Footnote44 In the United States, cotton similarly lost ground to synthetics in textile markets over the course of the 1960s.Footnote45 The synthetics industry aligned its product with modernity and aggressively targeted the mass ready-to-wear market.Footnote46 This market segment was ballooning with the coming of age of the postwar baby boom generation keen for textile convenience and performance as well as affordability and a new look in fashion styles ().

Figure 4. ‘Are you ready for this huge expansion’. Published in Australian Fashion News, June 1963. State Library of Victoria.

Wool was promoted as having more quality than synthetics. To defend a position for Australia’s natural fibre in the fast-changing global and domestic marketplace, the Wool Board continued to reinforce wool as a premium product and courted the luxury market of haute couture for its flagship fibre, fine Merino wool.Footnote47 In 1959, a fibre marketing guru, Nancy (Nan) Sanders, became head of a department within the Board dedicated to promoting wool. Sanders had had a successful career in the synthetic fibre industry, as the Australian agent for British Celanese before switching to ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) in 1956.Footnote48 For ICI she directed the Australian launch and promotion of Terylene, a fibre that had successfully challenged wool in the 1950s.Footnote49 The Wool Board poached Sanders in 1959, giving her full control of the promotions budget.Footnote50

Helming wool promotion, Sanders outsourced the selection of Christine Borge for the Cup Carnival to Madame Claude-Helene Neff, director of the Paris office of the International Wool Secretariat. Neff also officiated as one of the judges for the 1965 Fashions on the Field competition and brought with her a collection of exclusive Australian wool garments from Paris’s finest couturiers for Borge to wear.Footnote51 The international models engaged to represent each fibre appeared well-matched to their product. Borge’s personal alignment with the haute couture fashion she was to model meant that she was an apt choice for this prestigious assignment. Biographical reporting on Borge in the print media positioned her as an active participant in France’s elite and cultured society.Footnote52 ‘Her chicness and pert Parisian-isms’ portrayed in all corners of the media undoubtedly endeared her to Melbourne’s society matrons as well as cemented her suitability to move in the world of high fashion.Footnote53

Despite being the most photographed model at the time, Shrimpton’s projected image was that of the casual, girl-next-door.Footnote54 Therefore it was hardly surprising that Shrimpton’s racewear did not match the tone expected in Melbourne. For the Australian Orlon campaign, Shrimpton received little instruction from DuPont. The company supplied Orlon fabric with a request to have it made into racewear of her choice. With some prior experience in designing a small collection in conjunction with Mary Quant, Shrimpton engaged London dressmaker Colin Rolfe to realise her designs.Footnote55 Later, when interviewed on her wardrobe selections for Australia, she endeavoured to deflect the responsibility for the controversy back to DuPont. She feigned ignorance of the importance of the occasion, while simultaneously defending her right to dress as she saw fit.Footnote56 Justifying the short hemlines, Shrimpton told reporters in Melbourne that skirts were worn short in London in 1965 anyway.Footnote57 In her 1990 autobiography, Shrimpton claimed that she would have dressed similarly for any other race meeting in the world; she then contradicted that assertion by blaming DuPont for sending insufficient fabric, thus inferring that her outfits resulted from circumstances beyond her control.Footnote58 It is unlikely, even implausible, that a large and well-resourced multinational company such as DuPont would skimp on the fabric allowance for a model of Shrimpton’s global stature. It is inconceivable that the bare minimum of fabric that Shrimpton described as ‘inexpensive dress and suit lengths’ would have been provided or that additional fabric would have been denied if requested.Footnote59 In either case, the perceived shortcomings in her attire well rewarded DuPont in the long run and afforded Orlon a strong presence in the youth market.Footnote60 As a result of DuPont’s open-ended brief, Shrimpton embodied what Elizabeth Wissinger describes as an agent of style, a shaper of taste.Footnote61

Shrimpton’s Orlon outfits did not purport to be anything other than examples of comfortable, easy-care, affordable fashion. The styles appeared sufficiently uncomplicated, enabling them to be copied quickly by mass market manufacturers and home dressmakers alike. In fact, copies of her mini-dress appeared in Melbourne’s Sportsgirl store within days of Derby Day.Footnote62 In her 2015 recollections, journalist Helen Elliott considered that the style’s endearing feature for Australia’s young women was a freshness and simplicity that had not yet been seen in Australia.Footnote63 In contrast to Borge’s haute couture that only the wealthy could expect to afford, many of Australia’s young women could imagine themselves emulating Shrimpton’s style. As Kirsten McKenzie points out in her study of young Australian working women in the 1920s, movie magazines showed readers how to be modern on ‘a slender income’ through consumption, perpetuating an idea that the ‘modern-appearing woman’ could be visually transformed through commodities.Footnote64 In 1965, Shrimpton’s celebrity and appearance throughout the Australian media were similarly persuasive. With Shrimpton as its front-runner, DuPont’s promotions squarely hit their target in appealing to ordinary young women’s enduring desire to appear modern on any budget.

Celebrity models and fibre promotion at Fashions on the Field

The presence of celebrity models such as Shrimpton and Borge at the Cup Carnival was not by chance, but part of the VRC’s strenuous effort to raise revenue and resurrect the appeal of the Cup Carnival, especially to women. While some racing purists together with others in the wider community disliked linking fashion and horse racing, an alliance with the fashion industry presented the racing industry with an opportunity.Footnote65 Since 1953, a Cup Day fashion parade had been run collaboratively between Myer and high-end fashion manufacturer Leroy Manufacturing Co. Limited, providing trackside entertainment for wealthy female race-goers.Footnote66 However, the Fashions on the Field competition, with its democratising price limit categories and home-sewing section, was designed to engage a broader demographic of women in the fashion presented and to add to the appeal of the Cup Carnival.

Due to many factors, which included changes to Victoria’s off-course gambling laws and the popularity of competing sports such as Australian Rules football, the VRC had lost revenue, as fewer attended the races.Footnote67 Televised races from 1960 further reduced on-course patronage.Footnote68 According to former VRC Chairman Hilton Nicholas, by the late 1950s racing needed to win back its share of the public’s discretionary spending. Despite opposition from the older, more conservative faction within the racing fraternity, the VRC looked to business sponsorship for individual races and to other ways of pumping life and revenue back into the Cup Carnival.Footnote69

The VRC’s Promotions Sub-Committee brainstormed promotional possibilities together with public relations firm Colebrook & Associates. The VRC had originally brought Tom Colebrook and his wife Marjorie to Melbourne from Sydney in the late 1950s to ‘originate the transmission of an odds service’ and to assist in lobbying the Victorian government for legalised off-course betting via the creation of the Totalisator Agency Board.Footnote70 With those tasks achieved, the Colebrook consultancy was extended for the Cup’s Centenary celebrations in 1960. Tom and Marjorie Colebrook, whose earlier careers were in fashion manufacturing and modelling respectively, envisaged the cross-promotional value of fashion advertising through sporting events. After mounting a successful ‘black and white’ fashion event for the Cup’s Centenary, the idea for Fashions on the Field was born.Footnote71 While some within the VRC were dubious of its merit outside the Centenary celebrations, the Colebrooks trialled a Fashions on the Field competition at the Bendigo Cup in 1961.Footnote72 The success of the Bendigo event convinced naysayers on the committee of the value of piloting it at Flemington the following year.Footnote73

The first Flemington Fashions on the Field event took place on Cup Day in 1962 with the enthusiastic sponsorship of business interests in Melbourne and beyond. Industry body Garment Industries of Australia Ltd coordinated the competition.Footnote74 In the weeks leading up to the Carnival, major retailers such as Myer and Buckley & Nunn participated with mannequin parades and window displays of racewear, while the City of Melbourne festooned the streets of the CBD with flowers.Footnote75 Sponsors of that first fashion competition and of races over the course of the Cup Carnival included hoteliers, Ford Australia and Qantas.Footnote76 The VRC gave sponsors what John Silverton recalled as ‘the royal treatment’ on a special Sponsors’ Day earlier in October, including invitations to festivities in a purpose-erected marquee in the carpark.Footnote77 In addition to such trackside bonhomie, Eric Anderson from P. Rowe International, the distributors of DuPont’s textile fibres, recalled tangible cross-promotional benefits such as ‘a lot of publicity in the newspapers on our product’ plus, due to Colebrook’s connections, ‘Channel 9 would run a one-hour spectacular on television’.Footnote78 Television exposure was a major drawcard for sponsors. With the rising popularity of television viewing in Australia, television advertising revenue had swiftly surpassed that of radio advertising.Footnote79

The idea to invite international celebrity models to add further glamour to Fashions on the Field germinated in 1965.Footnote80 Casting his sponsorship net into the textile sector, Colebrook on behalf of the VRC invited the main fibre producers represented in Australia to bring an international model to Australia for the Cup Carnival. He touted unprecedented media exposure for a company’s product in exchange for the outlay, and he proposed that airfares and accommodation expenses would be offset by other sponsors such as Qantas and the John Batman Hotel in Melbourne in reciprocal arrangements.Footnote81 The VRC had much to gain from this deal and very little to lose. If others covered the models’ fees and associated expenses, the VRC’s financial obligation would be limited to providing the venue and hospitality, in appreciation for the sponsors’ efforts.Footnote82

For the plan’s success, Colebrook needed to stimulate the fibre producers’ cutthroat competitiveness. It became apparent to Silverton that Colebrook had already secured the support of the Wool Board’s Nan Sanders.Footnote83 Silverton recalled Sanders’ announcement at the first meeting between Colebrook and the invited fibre producers that high-profile French model Christine Borge would model wool at the Cup Carnival. Sanders then outlined what the Board hoped to achieve through its participation in Colebrook’s plan. As a respected and renowned fibre promotions veteran, Sanders’ positive response to Colebrook’s initiative carried weight.Footnote84

The VRC proposal for showing textile fibres at the races to both the end consumer and the trade on the backs of international models neatly dovetailed with DuPont’s marketing philosophy. From as early as the 1950s, DuPont’s US-based Textile Fibres Department had advocated various strategies to demonstrate possible end uses for its fibres to trade customers such as mills.Footnote85 Throughout the 1960s, DuPont marketers worked with retailers to educate the ultimate consumer through advertising and fashion parades, and it frequently used models and actresses to showcase the possibilities for fabric from DuPont fibres.Footnote86 Silverton anticipated his superiors’ favourable reception for the Fashions on the Field idea, but he considered that Sanders made a fundamental mistake in divulging that Christine Borge had already been engaged for wool. Relaying this intelligence back to the DuPont Board, Silverton suggested that DuPont counter wool by engaging ‘the top person in the world’.Footnote87 Enquiries to determine who was considered the world’s top model delivered the name Jean Shrimpton. Notwithstanding that Silverton recalled asking, ‘Who’s Jean Shrimpton?’, DuPont forged ahead, signing Shrimpton for a fee of £2,000 plus expenses, obliging her proviso that Terence Stamp accompany her to Australia.Footnote88 Despite initial interest from the other fibre companies, only the Wool Board and DuPont took up the challenge in 1965.

To earn her fee, Shrimpton’s duties were not solely to spend time at the Cup Carnival, wearing Orlon. Her Australian schedule for DuPont included photographic studio shoots modelling the following season’s Orlon trade knitwear garments for Australian print media; she was also to appear in the proposed television gala. According to Silverton, ‘[her fee] was incredibly good value as it turned out’. Silverton described Orlon as ‘a very nondescript product … [where] 95% of its consumption went into women’s twin sets or babywear. Hardly high fashion!’Footnote89 A 1957 DuPont report recommended a sustained marketing effort to ‘increase the social status of synthetic fabrics’ while at the same time convincing consumers of their affordability.Footnote90 Bringing the world’s top photographic model to wear a ‘nondescript’ fibre in a woven fabric was designed to elevate the fibre’s profile and overcome any lingering consumer resistance to synthetics.

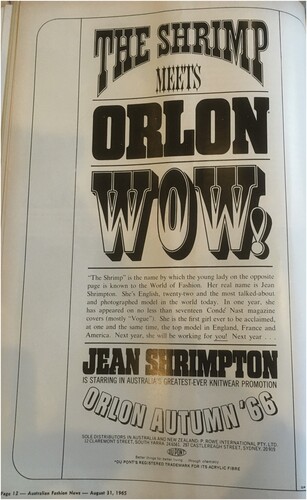

In a multi-page advertisement in trade journal Australian Fashion News (August 1965), DuPont announced to the trade that Shrimpton had been secured for Orlon ().Footnote91 Many mainstream media reports mistakenly suggested that the VRC had brought Shrimpton to Australia, but Silverton said, ‘It didn’t matter. What mattered was [that] the trade knew exactly who had brought her out’. DuPont’s upbeat trade announcement leaves little doubt that the ‘Orlon Autumn’ ‘66’ knitwear promotion was to be aimed at young consumers.Footnote92 The fonts and tone contain the hallmarks of ‘hip’ consumerism – advertisers commandeering the language of 1960s youth. According to marketing historian Thomas Frank, ‘hip’ consumerism entered general advertising as well as the trade discourse almost overnight in the 1960s, co-opting youth culture to sell products.Footnote93 But the results of the Shrimpton promotion ultimately reached far beyond the trade. Orlon on the back of Shrimpton signalled to the public that this synthetic fibre had graduated from utilitarian to the latest ‘cool’ fashion applications in knitwear, as well as to washable woven fabrics. Trending designs from overseas no longer needed to come with a hefty price tag. Not only was the price of synthetic clothing attractive to the youth market, the performance and styling possibilities of these fibres unlocked new uses for the mass market.Footnote94

Figure 5. ‘The Shrimp meets Orlon’. Published in Australian Fashion News, 31 August 1965. State Library of Victoria.

From its investment in Shrimpton, DuPont aimed for increased trade awareness for new, fashionable Orlon uses, but the extent and nature of the cross-promotional activities ensured that consumers could not ignore Shrimpton or her affordable fashion. In the months leading up to the Melbourne Cup, the Australian Women’s Weekly had in its pipeline a multi-issue cover spread on Shrimpton, and the Sun had devised a major release on Shrimpton’s early modelling memoir. Both publications liaised with DuPont to time their releases to achieve maximum effect. Although Silverton attributed the build-up of publicity ahead of Shrimpton’s arrival to ‘lucky networking’, these cross-promotions illustrate how fashion intermediaries creatively networked in Australia to increase awareness for products.Footnote95

After appearing trackside over the week of the Cup Carnival, both Shrimpton and Borge featured in the promised television spectacular. Heralded as the first time that spring racing fashion had been the subject of a dedicated television gala, the one-hour fashion spectacular first aired in 1965 as part of the BP (British Petroleum company) Super Show series broadcast through both GTV-9 (Melbourne) and TCN-9 (Sydney).Footnote96 The ‘Saturday night prime time spot’ impressed Silverton as this sponsorship benefit ‘was totally free of charge’ for DuPont.Footnote97 Reportedly, ratings for the popular Mavis Bramston Show broadcast on competing network Channel 7 plummeted on that same evening, a fact cited to measure the gala’s success.Footnote98 Orlon’s distributor, Eric Anderson, considered that the gala ensured that garments made from DuPont fibres gained national exposure, transcending that already earned at the Cup.Footnote99 No doubt Borge’s wool fashions received comparable coverage.

While the 1965 Cup Carnival wool promotion was mentioned briefly in the Wool Board’s Annual Report, the garments, not the personalities, were credited with ‘creating a great amount of consumer publicity’.Footnote100 In Sanders’ further report to the Wool Industry Conference, Madame Neff alone is given the publicity kudos.Footnote101 The silences in these reports regarding Christine Borge’s involvement may signal the Board’s disappointment with its choice of model; or it could flag the Board’s embarrassment over the amount spent on the promotion and Borge’s failure to measure up to Shrimpton in the publicity stakes. Sanders’ wool promotions department had already faced significant backlash from woolgrowers decrying the extravagant use of woolgrower levies in earlier grand-scale promotions.Footnote102 Furthermore, in what could also be interpreted as ‘sour grapes’, other advertising agencies such as J. Walter Thompson had criticised past wool promotions as a misuse of public funds in lavish advertising campaigns.Footnote103 Before the Wool Board employed Sanders, it had previously outsourced much of its promotional activities to competing agencies, Cardens and later Ralph Blunden Agency.Footnote104

Fashions on the Field cross-promotions – post-1965

DuPont’s commitment to importing an international model as a drawcard for four consecutive Cup Carnivals after 1965 indicates the promotional success of Shrimpton’s Fashions on the Field appearance. In the buoyant 1960s economic climate, Silverton considered that healthy sales figures for Orlon evidenced consumer approval.Footnote105 But in planning for the 1966 Cup Carnival, Silverton was mindful that Shrimpton had ‘split the social elite of Melbourne right down the middle … [and] … probably some of the committee people of the VRC’.Footnote106 Although many VRC members were savvy business people who recognised the value of controversial publicity to the Cup Carnival, DuPont’s marketing team were unsure whether they could or should replicate the impact of Shrimpton.Footnote107

The Wool Board appears to have reassessed its commitment to the international celebrity aspect of the promotion after 1965. Keith Dunstan reported that the media had eagerly awaited the announcement of who had been chosen from overseas to represent wool and continue the public fibre battle initiated the year before. There were even rumours that a member of the British royal family or a foreign royal could be recruited to score points for wool over DuPont, so the media were disappointed when the Wool Board withdrew.Footnote108

DuPont forged on alone with its association with Fashions on the Field and the quest to cement Orlon firmly into the mass market. While the Cup promotion made financial sense to DuPont in the four years following 1965, Shrimpton was the only model to create a media sensation. In the final two years of the company’s involvement, Silverton recalled that the young models selected, Hayley Gold from the United States and English Maudie James, failed to ‘spark the Press’ as Shrimpton had.Footnote109 After five years of continuous involvement, DuPont’s association with Fashions on the Field appeared to have run its course.Footnote110

The bleaker economic times of the 1970s took a toll on the local garment and textile industries from 1973. Consequently, the Fashions on the Field competition suffered a hiatus until its revival in the post-industrial 1980s. By then the Victorian government had identified the value of sport, events and spectacle as a means of revitalising one-time ‘marvellous’ Melbourne’s battered economy and its decimated manufacturing heartland.Footnote111 The linkage between racing and fashion formed the nucleus of a burgeoning events industry designed to give Melbourne a new image and arrest the city’s stagnation.Footnote112 With retailer Myer assuming the role of major sponsor in the 1980s, a reimagined Fashions on the Field added glamour to the Cup Carnival spectacle once again.

Conclusion

Cultural and economic forces melded when Jean Shrimpton and Christine Borge modelled synthetic and wool fibres for their respective sponsors on the lawns of Flemington Racecourse in 1965. Embodying the product and influencing perceptions of fashion and style, they occupied an intermediary space between the producer and the consumer.Footnote113 Through the media, particularly television, Borge’s and Shrimpton’s seizure of the spectator gaze unfolded before an attentive audience. The two models and the fibres they represented personified opposite sides of a generational demarcation line. The media coverage juxtaposed the youthful Shrimpton and her modern synthetic mini-dress against a backdrop of conservative tradition with Borge’s haute couture in wool aligning with the style and pursuit of elite culture. Images and news footage from the days of the Cup Carnival circulated both nationally and internationally, laying bare tensions between generations of Australians over ideas of traditional conformity and modernity in both style and social mores. Simmering below the surface of popular media representations was fierce competition between fibre producers over market share.

This reading of the Shrimpton story challenges the popular memory that the young model in isolation triggered the sweep of international youth fashion culture across Australia. In contrast to previous analyses of her Melbourne appearances, the new materialist lens employed in this article sharpens the focus on the fibres’ agency. It attributes causation to a complex system of marketing and cross-promotion of fibres with an event that was facing its own commercial challenges. Restoring Borge into the narrative and examining this cultural history from a new materialist perspective reveals the extent to which fibres and fashion were embedded within a web of relationships between humans, events and things. A young model and racewear, previously the domain of the wealthy, became the unlikely vehicles to elevate a humble synthetic fibre such as Orlon from its utilitarian past. It propelled modernity in fibres into the orbit of young fashion-conscious Australians. And the mini-dress showed them a style that aligned with the pursuit of fun and leisure that had begun to preoccupy youth’s mindset. Through the appearance of an icon of 1960s youth culture at a high-profile public event, such as the Cup Carnival, DuPont placed an attractive image of Orlon before the nation that had grown up with the promotional language around the superiority of wool.

The Shrimpton-Borge story offers a freeze-frame through which to view marketing’s co-optation of youth culture and its successful reading of the pulse of the aspirations and consumer desires of the nation’s young. Although Orlon’s marketing team could not have foreseen the momentous social and cultural change that privileged informal dressing in Australia following the first Fashions on the Field fibre promotion, the publicity that Shrimpton generated meant that Orlon was best placed to take advantage of that opportunity. Shrimpton overshadowed Borge throughout the Cup Carnival, indicating that both wool and haute couture were losing ground to easy-care, informal youth fashion. While wool’s promotion may have fortified its presence in the niche high-end consumer space, the wider market was left open for synthetic fibre competitors to reinforce their claims.

The clash of the two sponsored models at the Melbourne Cup Carnival illustrated how cross-promotions and the manipulation of the resultant gratuitous publicity became a marketing tool with far-reaching influence. First, it ensured that new overseas fashion and fibres appeared extensively on all the available media platforms to reach the imagined consumer looking for cheaper, high performance ready-to-wear fashion. Second, it rendered the lawns of Flemington Racecourse as a lucrative space for the commodification of spectacle with benefits for both Victoria Racing Club and its sponsors. This also signals that Melbourne’s post-industrial urban economy based on events, branding and marketing had its roots in the 1960s. Finally, and serendipitously for Australia’s youth at the time, it eroded perceptions that new fashion was linked solely to wealth and status. Fashion choice became realigned with individuality, personal taste, and affordability.Footnote114

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Margaret Maynard for her advice and mentorship on the preparation of this article through an Australian Historical Association Postgraduate Conference Award. My thanks to my supervisors Seamus O’Hanlon and Kate Murphy for their guidance, support and advice on this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 John Silverton, Transcript of oral history interview by Sonia Jennings, 30 July 1999, VRM10149, Australian Racing Museum; Alex Wade, ‘The Saturday Interview: Jean Shrimpton’, The Guardian, 30 April 2011, Australian edition.

2 ‘Model Flies in - and Faints’, Age, 26 October 1965.

3 ‘Christine and the Gallant Men’, Sun, 26 October 1965.

4 Melissa Bellanta and Lorinda Cramer, ‘“Well-Dressed” in Suits of Australian Wool: The Global Fiber Wars and Masculine Material Literacy, 1950–1965’, Fashion Theory, 30 June 2023, 2.

5 Keith Dunstan, ‘The Kookiest Cup of Them All’, Bulletin, 13 November 1976.

6 See for example Jonathan Walford, Sixties Fashion: From ‘Less Is More’ to Youthquake (London: Thames & Hudson, 2013); Alexandra Joel, Parade, 2nd edn (Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998); Roger Leong and Katie Somerville, ‘Beyond the Boundaries: Australian Fashion from the 1960s to the 1980s’, in Australian Fashion Unstitched: The Last 60 Years, eds Bonnie English and Liliana Pomazan (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 175–89.

7 See Sylvia Harrison, ‘Jean Shrimpton, the “Four-Inch Furore” and Perceptions of Melbourne Identity in the 1960s’, in Go! Melbourne, eds Seamus O’Hanlon and Tanja Luckins (Melbourne: Melbourne Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2005), 72–86; Prudence Black and Stephen Muecke, ‘The Power of a Dress: The Rhetoric of a Moment in Fashion’, in Rebirth of Rhetoric, ed. Richard Andrews (London: Routledge, 1992), 212–27.

8 See Lesley Johnson, The Modern Girl: Girlhood and Growing Up (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1993).

9 See Robin Gerster and Jan Bassett, Seizures of Youth: The Sixties and Australia (Melbourne: Hyland House, 1991).

10 Louis Menand, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War (London: 4th Estate, HarperCollins Publishers, 2021), xvi.

11 Ibid.

12 See Hannah Forsyth and Sophie Loy-Wilson, ‘Seeking a New Materialism in Australian History’, Australian Historical Studies 48, no. 2 (2017): 169–88; Simon Ville and Claire Wright, ‘Neither a Discipline Nor a Colony: Renaissance and Re-Imagination in Economic History’, Australian Historical Studies 48, no. 2 (2017): 152–68. For discussion on ‘new materialism’ in the international literature see Kenneth Lipartito, ‘Reassembling the Economic: New Departures in Historical Materialism’, The American Historical Review 121, no. 1 (2016): 101–39.

13 Anneke Smelik, ‘New Materialism: A Theoretical Framework for Fashion in the Age of Technological Innovation’, International Journal of Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (April 2018): 34.

14 Kate Smith, ‘Amidst Things: New Histories of Commodities, Capital, and Consumption’, The Historical Journal 61, no. 3 (2018): 853; Toni Ingram, Feminist New Materialism, Girlhood, and the School Ball (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023), 2.

15 Maurice Cavanough, ‘$2 to See the Cup Show’, Bulletin, 5 November 1966.

16 See for example Alison L Goodrum, ‘A Dashing, Positively Smashing Spectacle … : Female Spectators and Dress at Equestrian Events in the United States during the 1930s’, in Fashion, Design and Events, eds Kim M. Williams, Jennifer Laing and Warwick Frost (London: Routledge, 2013), 27–43; Valerie Steele, ‘The Theater of Fashion’, in Berg Fashion Library (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2017); Kim M. Williams, ‘Millinery and Events: Where Have All the Mad Hatters Gone?’, in Williams et al., 131–47.

17 Hilton Nicholas, Transcript, interview by Sonia Jennings, 19 July 1999, VRM10138, Australian Racing Museum.

18 Leong and Somerville, 179.

19 Harrison, 77.

20 Barrie Watts, ‘The Shrimp Shocked Them’, Sun, 1 November 1965.

21 ‘Defence for “The Shrimp”’, Age, 4 November 1965; ‘Australians Freed: “Shrimp” Leads Social Revolt’, Canberra Times, 6 January 1966.

22 Harrison, 81.

23 An entry in Wikipedia exists for Shrimpton’s Melbourne appearance that evidences the disparity in popular memory’s treatment of Borge. This entry is silent on Borge’s role in the story and there is no corresponding entry for Borge’s appearance. See ‘White Shift Dress of Jean Shrimpton’, Wikipedia, 7 November 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=White_shift_dress_of_Jean_Shrimpton&oldid=1183955000 (accessed 17 March 2024).

24 Keith Dunstan, ‘“The Shrimp” Shocks Flemington Matrons’, Age, 2 November 1988.

25 Keith Dunstan, ‘A Parisienne at Large … ’, Sun, 27 October 1965; Leonard Ward, ‘The Beautiful People’, Canberra Times, 17 December 1966.

26 Dunstan, ‘A Parisienne at Large … ’; ‘Roses All the Way, Now … ’, Sun, 27 October 1965.

27 Silverton, Transcript.

28 Dunstan, ‘The Kookiest Cup of Them All’.

29 ‘The Age TV-Radio Guide’, Age, 29 October–4 November 1965; Silverton, Transcript.

30 Silverton, Transcript.

31 Ken Mallett, ‘The Man Behind the Shrimp’, Sun-Herald, 7 November 1965; Tom Prior, ‘We’re a Giggle, Says Shrimp Escort’, Sun, 4 November 1965.

32 ‘Light Rain Dampens Fashions’, Canberra Times, 5 November 1965.

33 ‘Fashion Drama in 3 Acts’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 17 November 1965.

34 1960s advertisers increasingly directed fashion promotion to the under-twenty-five age group, effectively ostracising mature women. See Julie Rigg, ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Housewife: Mrs Consumer’, in In Her Own Right: Women of Australia, ed. Julie Rigg (Sydney: Thomas Nelson Ltd, 1969), 135–50.

35 Tom Prior, ‘Chris Bests The Shrimp at Oaks’, Sun, 5 November 1965.

36 Silverton, Transcript; ‘The Shrimp Hid Charms’, Sun, 3 November 1965.

37 Graham Gambie, ‘“I'd Do It Again!” Says the Shrimp', Sun–Herald, 7 November 1965.

38 Silverton, Transcript.

39 Ibid.

40 Jean Shrimpton and Unity Hall, An Autobiography (London: Ebury Press, 1990), 109.

41 ‘Top Model Returns Home’, Canberra Times, 8 November 1965; ‘The Shrimp Clams up on Sydney’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 November 1965.

42 Images and recollections of Shrimpton at Flemington on Derby Day in 1965 are frequently featured in the popular media. See for example Helen Elliott, ‘The Woman and the Dress That Stopped a Nation’, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 2015, https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/the--woman-and-the-dress-that-stopped-a-nation-20151026-gkik3u.html (accessed 20 May 2021). Photos from Derby Day 1965 appear on social media around the time of Melbourne Cup each year and contemporary recollections and comments include: ‘I loooved [sic] that dress. Made one immediately, shorter than that’; ‘It was a refreshing fashion thunderbolt!’; ‘A breath of fresh air in stuffy old Melbourne’; ‘[Mum] made me copies of her dress for my Barbie doll’; see Tony Beyer, ‘Pivotal Moments in Melbourne’s Social History’, Facebook, The Lost History of Melbourne/Victoria & Its Pioneers, 9 September 2021. The iconic Ray Cranbourne photograph of Shrimpton on Derby Day published in Melbourne’s Sun was considered emblematic of the era, as evidenced in its choice as the cover image for an academic edited collection: see O’Hanlon and Luckins.

43 Anneke Smelik, ‘Polyester: A Cultural History’, Fashion Practice 15, no. 2 (4 May 2023): 283.

44 Ibid., 285.

45 Ibid., 286.

46 Ibid. Designer Carla Zampatti recalled that synthetic fibres were taking the Australian clothing industry by storm in 1965 due to their comparatively low cost and versatility. See Carla Zampatti, My Life, My Look (Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 2015), 53.

47 See for example Tiziana Ferrero-Regis, ‘From Sheep to Chic: Reframing the Australian Wool Story’, Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 1 (2020): 48–64.

48 ‘Nancy Sanders to Promote New ICIANZ Fibres’, Clothing News, March 1956.

49 Joy Jobbins, ‘Australia’s “Highest-Paid” Woman in Controversial Role’, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 September 2014, Online edition.

50 Joy Jobbins, Shoestring: A Memoir (Sydney: Flock Publications, 2007), 177.

51 Couturiers such as Jean Patou, Nina Ricci and Yves St Laurent provided Borge’s garments. ‘Fashions from France’, Age, 2 November 1965.

52 ‘Visiting Paris Model Is Opera Fan’, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1965; Roland Pullen, ‘The Simple to the Sophisticated’, Sun, 14 October 1965.

53 ‘Two-Horse Race’, Australian Fashion News, 30 November 1965; Dunstan, ‘A Parisienne at Large … ’; ‘Visiting Paris Model Is Opera Fan’.

54 ‘Taming of the Shrimp’, Sun, 3 November 1965.

55 Anthea Goddard, ‘Shrimp in a Goldfish Bowl’, Woman’s Day, 8 November 1965; Shrimpton and Hall, 106–7.

56 Gambie.

57 Ibid.

58 Shrimpton and Hall.

59 In 1966 DuPont’s advertising program budget was $US56 million. E. I. du Pont de Nemours Inc., ‘Pretty Salesmen’, Better Living, April 1966; Shrimpton and Hall, 106.

60 By 1966 the Wool Board reported that wool substitutes such as Orlon were performing well in the market due to youth’s uptake. See Nancy M. Sanders, ‘Report to Wool Industry Conference: Market Development in Australia, 1966’ (Australian Wool Board, 1966), 2008/15/1-3/13, Joy Jobbins Fashion Advertising Archive, Powerhouse Collection, Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences.

61 Elizabeth Wissinger, ‘Modeling Consumption: Fashion Modeling Work in Contemporary Society’, Journal of Consumer Culture 9, no. 2 (2009): 273–96.

62 Vicki Steggall, Anything Can Happen … : Sportsgirl: The Bardas Years (Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books Australia, 2015), 56.

63 Elliott.

64 See Kirsten McKenzie, ‘Being Modern on a Slender Income: “Picture Show” and “Photoplayer” in Early 1920s Sydney’, Journal of Women’s History 22, no. 4 (2010): 114–36; Liz Conor, The Spectacular Modern Woman: Feminine Visibility in the 1920s (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 112–13.

65 Various factions within the committee opposed Fashions on the Field as outside the business of, and a distraction from the seriousness of, horse racing. Discussion was regularly recorded in the committee minutes questioning whether the event should be part of the Club’s business. Victoria Racing Club, ‘VRC Committee Minutes’, n.d., Victoria Racing Club Archives (accessed 7 March 2023). For discussions on the alignment of horse racing and the racewear market of the Australian fashion industry see Roger Leong, ‘Making and Retailing Exclusive Dress in Australia – 1940s to 1960s’, in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands, ed. Margaret Maynard, (Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010). 132–7; Juliette Peers, ‘The Melbourne Cup and Racewear in Australia’, in Maynard, 138–43; Williams.

66 Lesley Sharon Rosenthal, Schmattes: Stories of Fabulous Frocks, Funky Fashion and Flinders Lane (Melbourne: Self-published, 2005), 21–3.

67 Cavanough.

68 Television’s ability to undermine Hollywood’s stability as an industry was feared in the US in the 1950s, resulting in the mediatisation of red-carpet fashion where Hollywood stars functioned as mannequins. See Elizabeth Castaldo Lundén, ‘Fashion on the Red Carpet: A History of the Oscars®, Fashion and Globalisation’, in Fashion on the Red Carpet (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

69 Nicholas, Transcript.

70 Thomas Colebrook, ‘Letter to L. V. Lachal, Secretary, Victoria Racing Club’, 29 April 1964, Colebrook File, Victoria Racing Club Archives.

71 Marjorie Wilton (formerly Colebrook), Transcript, interview by Sonia Jennings, 10 August 1999, VRM10142, Australian Racing Museum.

72 Nicholas, Transcript.

73 Wilton, Transcript.

74 Garment Industries of Australia Ltd was a forerunner to Fashion Industry of Australia. ‘“Fashions on the Field” Was Big Success’, Australian Fashion News, 30 November 1962.

75 ‘“Fashions on the Field” Was Big Success’.

76 Wilton, Transcript.

77 Wilton, Transcript; Silverton, Transcript.

78 Eric Anderson, Transcript, interview by Sonia Jennings, 30 July 1999, VRM10144, Australian Racing Museum.

79 Robert Crawford, But Wait, There’s More … : A History of Australian Advertising, 1900–2000 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 2008), 126.

80 Cross-promotional use of celebrities modelling fashion in Australia was not unprecedented. In the 1950s Melbourne manufacturer of Sharene garments, Simon Shinberg, recruited English singer, Sabrina, to dress in his latest washable wool range for her Australian tour. See Rosenthal, 53.

81 Silverton, Transcript.

82 The initial budget allocated for the VRC’s promotion of Fashions on the Field was a modest £2,000. Victoria Racing Club, ‘VRC Committee Minutes’, 12 January 1966. An unnamed VRC official interviewed for a televised news service during the 1965 Cup Carnival praised Fashions on the Field for bringing more young people to the Cup but was quick to deny that the VRC paid to import celebrity models: see Jean Shrimpton at the Melbourne Cup 1965, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DRkx-wvCA18 (accessed 17 March 2024).

83 Silverton, Transcript.

84 Ibid.

85 Jim Kearns worked in DuPont’s US fibre marketing from 1950 to 1990 and described various marketing strategies over the decades of his employment. James ‘Jim’ Kearns, Interview by Joseph G. Plasky, 10 February 2009, 2010215_20090210_Kearns, Hagley Digital Archives.

86 Kearns; E. I. du Pont de Nemours Inc., ‘Pretty Salesmen’.

87 Silverton, Transcript.

88 Ibid.; Shrimpton and Hall, 106.

89 Silverton, Transcript.

90 Institute of Motivational Research, ‘A Creative Memorandum on Consumer Attitudes toward Synthetic Fabrics’ (New York, November 1957), Box 42, Hagley Digital Archives.

91 ‘Shrimp for Orlon’, Australian Fashion News, 31 August 1965.

92 Ibid.

93 Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 107.

94 Regina Lee Blaszczyk, ‘Styling Synthetics: DuPont’s Marketing of Fabrics and Fashions in Postwar America’, The Business History Review 80, no. 3 (2006): 527.

95 See Silverton, Transcript.

96 ‘Feast of Fashion’, Age, 4 November 1965.

97 Silverton, Transcript.

98 ‘Breath-Taking Show’, Australian Fashion News, 30 November 1965.

99 Anderson, Transcript.

100 Australian Wool Board, ‘Annual Report of the Australian Wool Board 1965/1966’ (Canberra: Government of the Commonwealth of Australia, 30 June 1966).

101 Sanders.

102 Jobbins, Shoestring: A Memoir, 208–10; ‘Another Wool Board Critic’, Bulletin, 6 June 1964.

103 Jobbins, Shoestring: A Memoir, 190.

104 Ibid., 181.

105 Former DuPont US product strategist Peter Butenhoff recalled that Orlon was ‘making a lot of money at the time’. Peter Butenhoff, Interview by Joseph G. Plasky, 20 October 2020, 2010215_20201020_Butenhoff, Hagley Digital Archives; Silverton, Transcript.

106 Silverton, Transcript.

107 Ibid.

108 Keith Dunstan, ‘In the Wake of the Shrimp’, Bulletin, 5 November 1966.

109 Anne Matheson, ‘Maudie James, the Model with All the Luck’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 5 November 1969; Silverton, Transcript.

110 Silverton, Transcript.

111 Seamus O’Hanlon, ‘The Events City: Sport, Culture, and the Transformation of Inner Melbourne, 1977–2006’, Urban History Review 37, no. 2 (22 March 2009): 31.

112 Ibid.

113 Joanne Entwistle, The Aesthetic Economy of Fashion: Markets and Value in Clothing and Modelling (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009), 3.

114 See Blaszczyk.