ABSTRACT

In comparison with interior design and architecture studies in Britain, Europe, the United States and Australia, little research has been conducted on interiors of the 19th century in New Zealand. Publications on New Zealand’s architectural heritage have largely focused on house exteriors, often including only passing reference to components of interior design. The fragments of knowledge about New Zealand’s early interiors that emerge from existing literature provide insight into the web of factors that shaped them. These include socio-cultural factors, the influence of media, and global and local economies. Picking up on these themes, this paper focuses on the wallpaper trade in Otago prior to, during and following the goldrush, between 1860 and 1867. The picture that emerges is of an Antipodean trade in predominantly British wallpapers, and a trans-Tasman network that facilitated the flow of wallpapers and traders between the Australian colony of Victoria and the province of Otago in New Zealand. Insights into the wallpaper patterns available in 1860s Dunedin are provided by photographs of shop windows and the display of wallpapers in the Furniture Court of the 1865 New Zealand Exhibition, as well as an archaeological sample from the 1860s.

Introduction

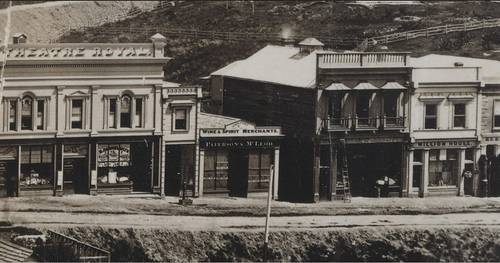

Robert Ethelbert Inman owned a paperhanging warehouse in Swanston Street, Melbourne, at the peak of the goldrush in Victoria in 1853.Footnote1 He imported wallpapers from England and France, selling large quantities of “every variety and class suitable for mansions, dwelling houses, offices and shops.”Footnote2 By the late 1850s, Robert and his brother George established branches of the business in the goldfield towns of Ballarat and Castlemaine inland from Melbourne.Footnote3 The decline in the Victorian goldfields and the rush of miners to the goldfields of Otago, New Zealand, in the early 1860s, prompted Robert to relocate to Dunedin, Otago’s entrepot city. In partnership with his brother, he opened R E Inman & Co Paperhanging Warehouse on Princes Street in April 1862, which he renamed to the Million House later that year when the partnership was dissolved.Footnote4 The flat-fronted two storey shop and residence (), located four doors down from the recently opened Theatre Royal, was part of a growing string of businesses that served Dunedin’s newly arrived residents and those passing through en route to the goldfields. An advertisement from a November 1862 issue of the Otago Daily Times describes the wallpapers on show in his shop window as the “cheapest and largest stock” of “new and splendid” wallpapers which are “suitable for every class of property” including “gold and flock, suitable for Dining and Drawing Rooms, 3s 6d a piece … also, Marbles, Oaks, and Granites” and wallpapers “suitable for Bars and Concert rooms.”Footnote5

Figure 1. Princes Street 1862, R E Inman’s Million House is on the rightof the image. Photographer: Burton Brothers. Source: Te Papa Collections, O.000863.

The story of Robert Ethelbert Inman provides a window into Otago’s wallpaper trade during the goldrush era, the wallpapers available, and connections between the Australian colony of Victoria and Otago, the loci of what historians now refer to as the Australasian goldfield which spanned the Tasman World rather than occurring in discrete locations.Footnote6 The language used within Inman’s advertisements also hints at the demand for a large range of cheap and luxury wallpapers to decorate the interiors of business premises such as shops and hotels, the homes of miners and those that accompanied them, and the residences of the elite grown wealthy, either directly or indirectly, from the goldrush. The sources of textual and visual information associated with Inman’s story reveal the potential of a novel approach presented in this paper to the study of wallpaper in 19th century New Zealand, a largely unexplored field of architectural history.

Traditional approaches to the study of wallpaper in New Zealand as a component of interior design have mostly relied on evidence of wallpapers in use “on the wall” and are largely based on documentary accounts and historical photographs.Footnote7 The limitations of these sources are well-understood. There are few contemporary accounts which mention wallpaper within their context of use, and interior photographs are scarce until later in the 19th century due to the amount of light needed for photography. However, by researching wallpapers “off the wall,” within the context of their consumption rather than use, new light can be thrown on this popular component of 19th century New Zealand interior decoration. Christine McCarthy’s research on the early commerce of wallpaper in New Zealand has demonstrated the value of this approach on a nation-wide level.Footnote8

Influenced by scholarship that approaches the history of interiors through a focus on material culture and consumption history,Footnote9 this paper continues McCarthy’s investigation of the role of wallpaper in New Zealand through the lens of its trade. As an imported commodity, sitting within what historian T.H. Breen has termed the “British Empire of Goods,”Footnote10 wallpapers and the manufacturers and suppliers involved, were a component both in New Zealand’s 19th century economy and in the shaping of the nation’s architectural material culture and colonial life. The focus of this paper is on the period which was a catalyst for the increased supply of wallpaper to New Zealand, the goldrushes of the 1860s, of which the Otago goldrush had the greatest impact. The period covered extends from 1860, the year prior to the discovery of gold in Otago, to 1867, which marked the decline of New Zealand’s 19th century goldrush era.

In the absence of any known surviving business records of Otago-based wallpaper merchants, which might have detailed their suppliers, connections, clientele and potentially their decision-making process as to which wallpapers to purchase, the paper pursues other strands of enquiry. These include trade statistics, which reveal the source and volume of wallpaper imports into New Zealand during the goldrush, providing evidence of the economic forces of demand and supply that the goldrush had on the wallpaper trade at a nation-wide level. Newspaper advertisements and trade directories are used to reveal the individuals involved and the mechanisms used to market wallpapers to consumers. A wealth of information can be extracted from these sources, providing both a quantitative picture of supply and demand at a local level, and the market forces which had an impact on the consumption of wallpaper during the goldrush. The paper adds a qualitative lens to the story of the wallpaper trade through historical photographs of wallpaper displays in the shop windows of merchants and at industrial exhibitions. Through these visual sources, we can see the wallpaper patterns and motifs that were available and popular at the time.

This paper begins by providing contextual overviews of wallpapers and their trade in the 19th century British world, followed by a summary of the New Zealand goldrush period and its impact on Otago’s built environment. Following this, the paper’s focus shifts to the commerce of wallpaper in New Zealand, its importation, and the local trade of wallpaper in Otago. It concludes with insights into the types and patterns of wallpapers available and used in Otago in the 1860s gained from newspaper advertisements, photographs of shop windows of Dunedin wallpaper merchants, a photograph of the Furniture Court of the New Zealand Exhibition, held in 1865 in Dunedin, and a wallpaper remnant found in a Dunedin house dating to the goldrush era. These textual and visual sources of information provide invaluable evidence of the wallpapers that were available and used at this time in lieu of the scarce interior photographs and descriptive accounts.

Wallpaper in the 19th Century British World

Wallpaper was an increasingly ubiquitous feature of interiors in the United Kingdom from the middle of the 19th century onwards, due to its increasing affordability following the mechanisation of the manufacturing process. Its ability to transform the backdrop of rooms cheaply and easily, and its function in conveying the tastes and aspirations of its owners, popularised the use of wallpaper beyond the homes of the rising middle and upper classes.Footnote11 Britain was at the centre of wallpaper manufacturing and trade at this time.Footnote12 A wide range of wallpapers were produced, from common printed pulps, to satin and gold papers, landscape papers, imitations of stone and timber, and sumptuous flock papers.Footnote13

Prior to the flourishing of the British Arts and Crafts movement under William Morris from the mid-1860s, which encouraged decorative patterns that were inspired by but did not copy nature,Footnote14 common wallpaper patterns fell into two groups; those which emulated nature, often in three dimensional designs, and more highly structured and at times austere patterns inspired by medieval and Neo-Gothic designs, including the regal fleur-de-lis, heraldic emblems, and geometric patterns such as the diaper, lozenge and trellis.Footnote15 The latter patterns were created by wallpaper designers influenced by the Design Reform movement, whose proponents included John Gregory Crace, Henry Cole, Augustus Pugin and Owen Jones. This movement emerged in Britain in the 1830s as a response to the mechanisation and mass-production of the decorative arts, which resulted in what were considered to be overly ornate and “poor taste” designs. From the mid-19th century onwards, the Design Reform and subsequent Arts and Crafts Movement strongly influenced the designs and colours of interiors and the items that comprised them, including wallpapers.Footnote16

A wide variety of colours were used in the production of wallpaper, with darker colours such as red, green and blue, often favoured for higher end wallpapers. Dark coloured wallpapers signified the wealth of the homeowner, who could afford to light their homes using ample gas and oil lighting, reducing the need for light coloured and reflective wallpapers. Dark wallpapers were considered to represent a subdued and “proper” air of luxury compared to often multi-coloured wallpapers on light coloured grounds.Footnote17

The speed of wallpaper production and the proliferation of manufacturers and designers from the mid-19th century catapulted the wallpaper industry into a frenzy akin to the fashion industry.Footnote18 A plethora of designs were produced to meet the latest trends and tastes of the season. The desire of consumers for the newest and best wallpapers was fuelled by catalogues and sample books produced by manufacturers and sellers, wallpaper displays at international and industrial exhibitions, and the design publications that emerged in the wake of the Design Reform and Arts and Crafts movements.Footnote19

Upon rolling off the factory floor in London and other centres of wallpaper manufacture in England, Scotland and Ireland, wallpapers quickly reached their eager consumers through established trade networks in the British Empire.Footnote20 Prior to the establishment of direct steam ship services between New Zealand and the United Kingdom in the 1870s, a large proportion of trans-shipments went via the Australian colonies of Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania; either as tran-shipments which remained on board, or as goods which were offloaded, stored and later shipped to New Zealand.Footnote21

It is within this context that the colonial settlement of New Zealand was in full swing. Houses and public buildings sprang up to accommodate the lives and businesses of the growing population. The interiors of many of the first colonial settler dwellings were sparsely decorated, consisting of little more than basic furnishings that were either self-made, manufactured locally, brought to the colonies as personal luggage, or purchased from local shops which supplied a wide range of goods needed and desired by consumers.Footnote22 Due to wallpaper’s prominence in the British world, its sentimental function of imparting a sense of “Home” and permanence to colonial interiors, and its practical application as a draught-proof layer in New Zealand’s predominantly timber-framed and lined houses, it was a sought after component of interior design from the earliest decades of European settlement.Footnote23 In the absence of local manufacture, this demand for wallpaper was met by the importation of foreign, predominantly British, wallpapers.Footnote24

Otago Gold, People, and Towns

The supply of wallpaper to Otago in the goldrush years occurred within the context of New Zealand’s place within the British wallpaper trade, the changing flow of people, gold and fortunes, and the rise and fall of the associated building activity. The 1860s were a boom time in the history of Otago. Following the discovery of gold in 1861, Dunedin became the economic hub of New Zealand. The wealth extracted and generated from the goldfields and the exponential increase in population resulted in a higher flow of goods entering the port city. The value of all imports increased by 152% from 1861 to 1862, with the vast majority (62% of all imports in 1862) coming from Victoria, demonstrating the importance of Victoria for Otago’s economy and the strong trade links between them.Footnote25 Not only did the population and wealth of Otago grow exponentially in the 1860s, but so did its towns, with a greater number of grander houses being constructed for the increasing, and increasingly wealthy, population.

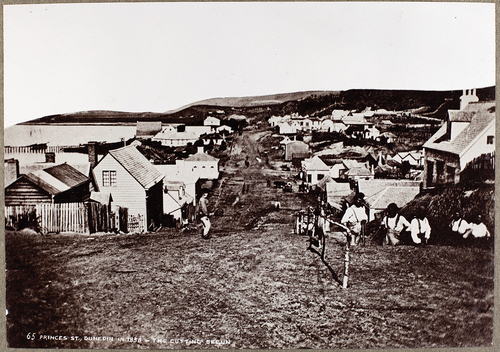

In 1858, ten years after settlement and three years prior to the discovery of gold, the town of Dunedin was clustered around Princes and Macglaggan Streets near the jetty (now Jetty Street). A photograph looking south from the cutting in Princes Street () shows the mostly wooden hotels, businesses and dwellings lining either side of this muddy thoroughfare, aptly representing the towns colloquial name of “Mud-edin.”Footnote26 While smaller towns were established along the coast, such as Oamaru to the north and Milton and Balclutha to the south, the hinterland, including Central Otago, is estimated to have had a small and dispersed European population of around 300 people linked by rudimentary roads.Footnote27

Figure 2. Looking south down Princes Street 1858, when the cutting is begun. Photographer: William Melhuis. Source: Te Papa Collections, O.030500.

When gold was discovered in May 1861 in the Tuapeka River near the present township of Lawrence, news quickly spread within New Zealand and overseas.Footnote28 Contemporary sources describe the rush from the declining Victorian goldfields in Australia to New Zealand from July that year, stating that “every available steamer was laid on … some of which brought over as many as 700 diggers, and it is calculated that in one month as many as 10,000 people left Melbourne for Otago.”Footnote29 Additional gold discoveries were made later that year in Waipori, near Lawrence, and in Central Otago along the Clutha and Arrow Rivers in 1862. Canvas towns, consisting initially of tents and other rudimentary shelters, quickly established themselves near the diggings, at Dunstan (present day Clyde), Cromwell, Alexandra, Arrowtown and later Queenstown.

At the peak of the Otago goldrush in 1863, the population of the region was estimated to be over 67,000, representing a ten-fold increase in Otago’s population from 1858, with most of the growth occurring in Dunedin and Central Otago near the goldfields.Footnote30 Roads were formed to link goldfield settlements to coastal towns, and Dunedin established itself as the commercial hub of the new, gold-derived economy.Footnote31 The Southern Provinces Almanac of 1863 mentions an increase in building activity in Dunedin, noting that “in every part of the city the accumulation of wealth, as evidenced in the numerous magnificent and costly buildings, is observable.”Footnote32 A photograph from 1863 (), taken from roughly the same position as five years prior (), illustrates the impact on Dunedin’s built environment as a result of the increased population and wealth generated by the goldrush. Substantial buildings made of stone and wood now lined Princes and George Streets, Dunedin’s commercial hub. Beyond, houses of all descriptions were built for the growing population. This included humble dwellings, and more substantial residences such as Lisburn House (). Designed by Mason and Clayton, Lisburn House was built in 1864 as a town house for James Fulton and his family, whose wealth derived from farming on the nearby West Taieri Plains. The two-storeyed and steeply gabled house, with its solid brick construction featuring diaper patterned light coloured brickwork, stands in contrast to the unformed road and the less pretentious dwellings in the background of the image.

Figure 3. Looking south down Princes Street from the cutting,1863. The Oriental Hotel is being constructed (right). Photographer: Muir and Moodie. Source: Te Papa Collections, O.001625.

Figure 4. James Fulton’s Lisburn House, Dunedin,1865. Photographer: Unknown. Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka oHākena, University of Otago, Box 228-012.

By 1864, the easily extractable alluvial gold deposits in Otago were largely exhausted. Large numbers of miners, their families, and the entourage of business entrepreneurs that had accompanied them, either returned home, such as to Victoria, or moved to newly discovered diggings in New Zealand, on the West Coast and at Nelson. The West Coast goldrush was equally short-lived, peaking in 1866/7. The New Zealand goldrush period was largely over by the end of the decade.Footnote33 However, the city of Dunedin continued to grow and expand in the late 1860s, sustained by its thriving port and the businesses and institutions that catered for its established population. A photograph taken in 1869 () shows newly formed roads, footpaths and street lighting, along with the most exuberant example of Dunedin’s boom style architecture, the Oriental Hotel, built at the newly created Princes Street cutting.Footnote34 The extraordinary design of the Oriental Hotel, representing an amalgam of Gothic, Continental, Renaissance, Old English, American and Oriental architectural styles, illustrates the optimism of this decade, and the extent to which the architectural envelope, both literally and figuratively, could be pushed within the context of Victorian society at this time.Footnote35

New Zealand’s Wallpaper Imports

While there is photographic evidence of the aesthetic aspirations of newly wealthy residents of Dunedin during the goldrush in the form of street scenes, such as the ones described above, there is little existing visual or textual information about the interiors of these buildings. The increase in Otago’s building activity in the 1860s undoubtably generated an increased demand for wallpapers to line and decorate the interiors of newly constructed dwellings, public and commercial premises, and to re-decorate the walls of existing homes and buildings to keep abreast of the latest interior fashions.

Research on the wallpaper trade in 19th century New Zealand using trade statistics sheds light on when, where from, and in what quantities, wallpaper was imported into Britain’s southernmost colony. Despite the absence of specific data on Otago’s wallpaper imports, these nationwide statistics illustrate the impact of the Otago goldrush and the associated influx of wealth, people and construction activity on New Zealand’s wallpaper import market.

Trade statistics provide an empirical means to trace the origins and quantities of imported goods such as wallpaper. In light of large gaps in the available New Zealand import statistics up to 1867 which itemise wallpaper,Footnote36 the export statistics of the United Kingdom, New South Wales, and Victoria were consulted for the period covered by this paper (1860 to 1867).Footnote37 These supplied over 99% of New Zealand’s wallpapers for the first five years that these were itemised by country of origin in the import statistics.Footnote38 The graph based on this export data of wallpaper to New Zealand between 1860 and 1867 illustrates parallels with the fortunes of the Otago and West Coast goldfields, the associated building boom, and maritime traffic ().

Figure 6. Value (pounds sterling) of wallpaper exports from the United Kingdom, Victoria and New South Wales to New Zealand. Source: authors.

The graph shows a steady increase in wallpaper exports to New Zealand in the three years between 1860 and 1862, with a growing proportion coming from Victoria in 1861, when shipping traffic to Otago increased following the discovery of gold. The peak in wallpaper exports, which occurred in 1863, coincides with the peak in the Otago goldrush and the rapid increase in building activity. Exports from New South Wales and Victoria make up nearly 50% of wallpapers coming into New Zealand, with the latter presenting the largest proportion. The value of wallpaper exports from Victoria drops sharply in 1864 and 1865 following the decline of the Otago goldfields, decreasing to only 8% of total wallpaper exports to New Zealand across these two years. The 1866 increase in wallpaper exports corresponds with the peak in the West Coast goldrush, with exports dropping again by 1867 as New Zealand’s goldrush period came to an end.

The statistical pattern of wallpaper imports to New Zealand, in particular the predominance of imports from Victoria, confirms the findings of recent research on the commercial links between the goldfields of Australia and New Zealand during the goldrush era.Footnote39 The early and established two-way trade networks that existed between New Zealand and Australia, in particular the neighbouring colonies of Victoria and New South Wales, were amplified when gold was discovered in Otago. The unprecedented increase in shipping, with four powerful steamers travelling between Victoria and Otago by 1863, created veritable sea highways along which people, goods and gold were transmitted.Footnote40 Following the discovery of gold in Otago, merchants from Melbourne joined the throngs of miners rushing to the goldfields to take advantage of the increased demand for a wide range of goods, including tools and materials for the construction of more permanent dwellings. These merchants not only had strong business connections to their home base in Australia but were also linked into the wider global trade networks created by the 19th century global goldrushes.Footnote41

In the absence of any significant wallpaper manufacturing in Australia, beyond boutique hand-printed papers, the colonies of New South Wales and Victoria also relied on imports from elsewhere.Footnote42 The import statistics of both colonies for this period show that over 93% of wallpapers came from the United Kingdom, with the remainder coming from Europe (Germany, Netherlands, France), other Australian colonies, and elsewhere in the world.Footnote43 Thus, the wallpapers that arrived into New Zealand were predominantly of British origin, either shipped directly or re-exported from Australia, reflecting the economic and social ties of the colonies to Britain. However, unlike their British counterparts, customers in 1860s New Zealand were unable to acquire the latest wallpaper patterns. This is due to the tyranny of distance and the slower speed of sailing ships which plied the trade between the United Kingdom and the Antipodes until the early 1870s, with a one-way trip taking up to 100 days.Footnote44 In the absence of a direct telegraph link, which only became available in 1876, the orders themselves, and the wallpaper catalogues and sample books that may have preceded these, also needed to be conveyed on board these ships.Footnote45 Hence, unless the manufacturers or agents located in the United Kingdom selected wallpaper patterns for merchants and customers based in New Zealand, the wallpaper designs which landed in New Zealand would have been at best a year out of date.

Otago’s Wallpaper Trade 1860 to 1867

Otago’s wallpaper trade was connected to these overseas markets and networks, extending from the origins of wallpaper, predominantly the United Kingdom, to their trade in Australia. Local merchants either ordered wallpapers directly from overseas manufacturers and agents or imported them from warehouses or branches of their own businesses in Australia, which were predominantly based in Victoria. In the absence of surviving business records of Otago merchants, the history of this trade may be traced using street and trade directories, and newspaper advertisements published in both Victoria and Otago.Footnote46

Prior to the discovery of gold in May 1861, the Otago wallpaper trade was relatively small and focussed solely on Dunedin. The 1863 Southern Provinces Almanac recalls the “straggling places of business” in Dunedin at this time, with wallpapers sold in shops lining the muddy streets surrounding the jetty ().Footnote47 Regardless of these circumstances, Dunedin’s fledgling wallpaper market was already influenced by links to New South Wales and Victoria, largely due to the origin and business connections of the merchants and their stock in trade, with newspaper advertising reflecting a strong demand for a range of wallpapers soon after the establishment of the European settlement of Dunedin in 1848.

From 1852 to 1861, advertising and street directories suggest there were only a small number of Dunedin merchants, between one and four each year, selling wallpapers. Like many of New Zealand’s early wallpaper sellers, most were general merchants.Footnote48 The first advertisement found for wallpaper in Dunedin is from August 1852 by James Macandrew, who, after arriving from Scotland the previous year, established his mercantile and shipping business.Footnote49 The first painting, glazing and paperhanging businesses were established in Dunedin around 1860. These included David Milne, who arrived from London the previous year, and James Keir and Andrew Lees, operating under the name of James Keir & Co, who arrived on separate ships from Glasgow.Footnote50 Both businesses advertised their services to Dunedin residents and to clients in the surrounding area in the pages of the weekly Otago Witness.Footnote51

Of the eight Otago businesses selling wallpaper up to 1860, at least three had connections to New South Wales or Victoria. Johnny Jones, a prominent early business figure in Otago, and J C Carnegie were both based in Sydney prior to emigrating to Dunedin. Jones, who sold wallpapers at his Port Chalmers and Dunedin stores, also held shares in the Otago Steam Ship Company, which had two vessels engaged in the Melbourne trade.Footnote52 The firm of Ross & Kilgour, established by George Ross and his bother-in-law James Kilgour, was connected to markets back in the United Kingdom, where James had acquired considerable experience in the mercantile business, and in both Sydney and Melbourne.Footnote53 In July 1855, George advertised his visit to both Australian cities, stating that in addition to purchasing goods for the store, he would execute specific orders for customers.Footnote54

The two-year period between the discovery of gold in Central Otago in May 1861 and the decline of the Otago goldfields from December 1863, marks significant changes in Otago’s wallpaper market. Many specialised wallpaper sellers were now involved in the trade, most of whom were still based in Dunedin, along with two businesses selling wallpaper in the goldfield towns of Clyde and Queenstown. The Australian connection of wallpaper merchants, in particular to Victoria, became increasingly prominent. There was also a dramatic increase in the number of advertisements and the quantities of wallpaper noted in local newspapers, indicating an increased supply and demand for wallpapers within the context of the booming construction market.

At least nineteen new merchants joined the wallpaper trade during Otago’s main goldrush years.Footnote55 This is a large number considering there were just over 8,300 houses or buildings (excluding tents) in Otago by the end of 1863 which these merchants could have furnished with their products. Of these, six were general merchants, including James Paterson, who sold wallpaper alongside goods catering for miners, such as diggers picks, gold scales, and cutty pipes for smoking.Footnote56 Two merchants promoted their connections to Victoria, the country of origin of a large proportion of new immigrants. Robert Bowden Martin, who moved from Melbourne to Dunedin in 1858, advertised a large range of goods on offer, including wallpaper, which he imported predominantly from Melbourne.Footnote57 Prior to moving to Dunedin in 1862, Edward de Carle operated a general merchandise warehouse on Little Bourke Street in Melbourne.Footnote58 He established his Victorian Auction Mart, suggestive of his Melbourne connections, opposite the Otago Daily Times offices on Princes Street.Footnote59 De Carle also advertised his services as a forwarding and buying department for the goldfields by 1865, indicating his expanding web of business connections into Otago’s goldfields.Footnote60 Wallpaper was also on the sales list of the Queenstown Auction Mart in November 1863, showing that wallpaper had made its way to this fledgling settlement near the Arrow River goldfield.Footnote61 Two Dunedin timber merchants also engaged in the wallpaper trade at this time, operating as one-stop-shops to those building and decorating their new homes and businesses, G S Wilson and John Gray. The latter was a timber merchant on George Street, who advertised the sale of wallpaper amongst his stock of weatherboards, windows, corrugated iron and American lumber.Footnote62 Eleven of the new Otago merchants engaged in the trade of wallpaper were either painters, glaziers, and paperhangers, or they operated so-called “Paperhanging Warehouses,” dealing almost exclusively in wallpapers. The proliferation of these types of specialised businesses indicates a demand for interior decorating goods and services amongst the growing population of Dunedin, together with an anticipated demand by those who established them.

Since at least six businesses were established by people engaged in the wallpaper trade in Victoria, which was going through a period of depression, it is likely that the Otago businesses of these wallpaper merchants were established in anticipation of the demand they witnessed in Victoria at the peak of the goldrush in 1852/3.Footnote63 Potentially, they also intended to dispose of surplus stock which had accumulated after the Victorian peak had waned. In 1862, the Descriptive Sketch of the Province of Otago, New Zealand, a promotional publication by the Provincial Government of Otago, noted that for Victorian merchants the Otago goldfields provided a market for surplus goods, stating that “thousands of pounds, locked up in unsaleable goods, have been set free …”Footnote64 If wallpaper was amongst these surplus goods that were shipped to New Zealand, their designs would have reflected patterns that would have been fashionable in the United Kingdom several years earlier.

Two prominent Melbourne businessmen joined the Dunedin wallpaper trade in 1862. Reference in their advertisements to either wallpapers manufactured in England, or family relationships in successful businesses there, shows the importance placed on goods and connections to “Home.” Henry Brooks, a successful paint, glass and wallpaper merchant in Melbourne,Footnote65 sent his agent Henry Walden to Dunedin by May 1863, to sell the goods of his business on Elizabeth Street in Melbourne from premises on Stafford Street in Dunedin; included were wallpapers manufactured by C E & J G Potter of Lancashire, England.Footnote66 Henry Pelling operated the Tottenham House Paperhanging Warehouse on Queen Street, Melbourne, from 1858, proudly stating that he was the nephew of James Shoolbred, a successful draper on London’s Tottenham Court Road in the 1850s.Footnote67 After moving to Dunedin in early 1862, Pelling established a wallpaper warehouse of the same name on Princes Street.Footnote68 By May 1863, Pelling opened a branch of his business, the Dunstan Paperhanging Warehouse, on Ferry Street in the infant goldfield town of Clyde.Footnote69 The neatness of his plate glass fronted shop, and the “artistic display of wares,” at a time that businesses were struggling in Otago, was commented on in the Dunstan report of the Otago Daily Times in June 1864.Footnote70

The increasing competition amongst the large number of businesses trading in wallpaper during the peak of the Otago goldrush period in early 1862, is evident in the predominance of language denoting the cheapness of wallpaper in newspaper advertisement. Given that the goldrush and the associated building boom had only just started, the demand for wallpapers would not have been high. In February 1862, Henry Fish advertised “A large stock of paperhangings, borders etc, on sale at low prices.”Footnote71 The Victorian Paperhanging Warehouse “Wanted everybody to know the cheapest place to buy paperhangings” was at their establishment.Footnote72

The associated increase in the supply and availability of wallpapers is matched by an increase in advertisements. Between May 1861 and December 1863, fifty unique advertisements appeared in Dunedin newspapers, compared to only thirteen over the preceding nine years. The advertised quantities also increased, often being in the thousands, or tens of thousands of rolls. In October 1862, Henry Pelling advertised that he held a supply of 50,500 wall and ceiling papers.Footnote73 This increase in the advertised quantities coincides with the peak in wallpaper exports to New Zealand as seen in the graph (), and the increase of exports coming from Victoria, providing further evidence for the strong influence of demand from Otago on the supply of wallpaper to New Zealand at this time.

The four years from January 1864 to December 1867 marked a stabilisation of the wallpaper market in Dunedin, and the branching out of various businesses to Otago’s growing towns, both inland and along the coast. The Mackays Almanack [sic] of 1864 lists seven painters, or painters and glaziers, in Oamaru (1), Waikouaiti (2), Milton (3), and Balclutha (1). Some of these merchants, such as J S Anderson of Oamaru and William Houston of Milton, were also likely engaged in the supply and installation of wallpaper, which often went hand-in-hand with these trades.Footnote74 The only wallpaper business advertising in Central Otago newspapers was that of William Auckland, who established his signwriting, house painting and decorating business on Sunderland Street in Clyde by January 1866. The “large assortment of paperhangings” on offer would have been purchased by those building and decorating the new and more permanent houses and business premises that were increasingly replacing the miners’ tents.Footnote75

Despite the decline of the Otago goldfields between 1864 and 1867, the demand for wallpapers and the services of those who installed them remained high. In the trade section of Dunedin street directories, the number of painters and paperhangers listed between 1864 and 1867 is stable, at between twenty and twenty-five.Footnote76 The wallpaper market in Dunedin was operated almost exclusively by decorating specialists, with only one advertisement for wallpapers during this time by auctioneer J Daniels & Co.Footnote77 This indicates not only the established demand for wallpapers in a steady construction market, but also the desire to purchase these goods from experienced tradespeople focused on the interior decorating trade.

In the post-gold rush boom years, the preferred advertising medium shifted away from newspaper advertisements to large advertisements in varied fonts in the newly published street directories (), and also to the visual medium of the wallpapers themselves, displayed in the shop windows of merchants, such as the display of wares noted in Pelling’s Dunstan Paperhanging Warehouse. The shop window of Inman’s relocated business on the opposite side of Princes Street, Dunedin, now operated by George following Robert’s death in March 1863, and the premises of Andrew Lees, formerly of James Keir & Co, on George Street, illustrate the effectiveness of this method of selling. In a photograph taken in early 1864, George Inman proudly stands in the doorway of his shop, leaning on what may be empty hessian bales which contained the recently arrived wallpapers in the prominent large paned shop window next to him (). In the case of Andrew Lees’ yet to be named business premises, the unfurled rolls of patterned wallpaper are flanked on either side by window displays of businesses selling a range of items, such as the fancy goods sold by Lo Keong, forming an open-air arcade to entice passers-by ().

Figure 7. Advertisement for James Keir & Co, Dunedin. Harnett & Co’s Dunedin Directory for 1864, p. 112.

Figure 8. R E Inman & Co’s shop in the provincial buildings, Princes Street, Dunedin, January 1864. Photographer: Daniel Mundy. Source: collection of Toitū Settlers Museum, Dunedin, Album 54_35.

Figure 9. George Street c1870s, showing Andrew Lee’spaperhanging business to the left of Lo Keong’s fancy goods store. Photographer: Unknown. Source: Hocken Collections - Uare Taokao Hākena, University of Otago, P1911-001-011a.

As this analysis of the Otago wallpaper trade during the goldrush years has shown, the market for wallpapers was influenced by the flow of people and the increase in construction activity which remained steady, even as the height of the rush receded. Several of the merchants who traded in wallpapers, especially during the boom years between May 1861 and the end of 1863, came from Victoria and likely imported their stock of predominantly British wallpapers from there. The wallpaper market in Dunedin was effectively drawn into that of Victoria, with the former being described by some historians as a suburb of Melbourne during this time.Footnote78 A wide range of wallpapers were available in Dunedin during the 1860s to meet the demands of consumers for a variety of patterns to suit all types of budgets, rooms, and individual tastes. New wallpaper and decorating businesses took advantage of the region’s rapid economic growth, advertising their services in newspapers and street directories, and displaying their wares in elaborate displays behind shining plate glass windows along the main commercial streets of Dunedin and satellite towns throughout Otago.

Otago’s Wallpaper Patterns

Glimpses into the types and patterns of wallpaper sold and used in Otago’s domestic and public interiors of the goldrush era, are provided by written descriptions in advertisements, photographs of wallpapers on display, and a surviving remnant of wallpaper encountered in a Dunedin house dating to the 1860s.

Of the 125 newspaper advertisements of Otago’s wallpaper merchants between 1860 and 1867, twelve mention the types of wallpapers on sale. This includes ceiling papers applied to the ceilings of rooms as a decorative, and often cheap, finish in lieu of the more expensive plaster or timber tongue-and-groove ceilings. An advertisement by Henry Pelling in October 1862, describes the pattern of a ceiling paper on offer, a “watered ceiling paper.”Footnote79 These types of papers were a popular pattern in the 19th century due to their design, emulating water or fabric ripples on a light coloured background, which obscured water or dirt stains on ceilings.Footnote80 Other types of wallpapers being sold included the more sumptuous gold and flock papers commonly used in dining and drawing rooms, and satin papers with patterns printed onto a shiny and often light-coloured background.Footnote81 Satin wallpapers were a more luxurious and expensive option compared to pulp wallpapers printed onto plain or coloured paper.Footnote82 Several advertisements also mention the availability of imitation wood and marble wallpapers, which were popular for hallways, hotels, or grand public rooms.Footnote83

An advertisement by Henry Pelling from February 1862, mentions the availability of wallpaper borders, corners and ceiling centre pieces that were used as embellishments over wall and ceiling papers. This advertisement also describes the suitability of different wallpaper types and patterns for different rooms, “10,000 pieces dining room, drawing room, bedroom, parlour, passage, shop, and ceiling paper hangings,”Footnote84 which was an established trend in British interior design by this time.Footnote85

These textual clues about the types of wallpapers traded by Otago’s merchants in the 1860s are complemented by limited photographs of the wallpapers they sold. The shop window displays of Robert Inman’s Million House from late 1862 (), George Inman’s shop from January 1864 (), and that of Andrew Lees’ from c1870 (), provide datable and visual clues. These photographs of wallpapers “off the wall,” photographed from the naturally well-lit exterior rather than on the wall in dark rooms, capture the patterns, if not the colours, on display. These patterns are natural and geometric motifs in either horizontal bands, trellises and geometric diaper, or diamond, patterns in dark and light colours. These show similarities to wallpapers associated with Australian domestic interiors dating to the mid-19th century,Footnote86 which in turn reflect naturalistic motifs as well as the stylised and geometric patterns influenced by the Design Reformers in Britain around this time.

A photograph of the Furniture Court of Dunedin’s New Zealand Exhibition of 1865 () provides further visual evidence of wallpapers considered to be the height of fashion. The New Zealand Exhibition fits within the wider context of British and colonial exhibitions of industry and progress. In England, this includes the Great Exhibition in London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, and the Great London Exposition of 1862, where goods produced in Britain and overseas, predominantly in the colonies, were on display. Wallpaper manufacturers and traders utilised these prestigious platforms to display the wide range of papers that were now mass produced using the latest developments in machine printing.Footnote87 Wallpaper manufacturers from all over the world, but predominantly from England, also displayed their wares at exhibitions held in Australia, such as the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition, and the 1880/1 International Exhibition and 1888/9 Centennial Exhibition held in Melbourne.Footnote88

Figure 10. New Zealand exhibition, Furniture Court and museum, Dunedin, 1865. Photographer: Unknown. Source: Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago,P2011-021/3-01.

In Dunedin, the 1865 Exhibition included wallpapers sent over by the London firm of J. Woollams & Co, and wallpapers imported by two Dunedin merchants, David Milne and Scanlan Brothers, all of British manufacture.Footnote89 The official competition report commented on the “vast improvement that has been made in the design and manufacture of this universal article of interior decoration,” expressing the migration of the ethos of the Design Reform movement to New Zealand.Footnote90 Geometric diaper patterns prevail in the wallpapers above the archway, with the fleur-de-lis motif of several of these (most prominently seen in the fourth wallpaper from the left), signalling the fashion in Britain, and its colonies, at this time for heraldic motifs.Footnote91 While the flowing natural motifs of some of the wallpapers in the shop windows are missing in the displays of wallpaper at the exhibition, the wallpaper borders in the second room, displayed on the wall and the arched ceiling above, depict isolated floral garlands amongst what appear to be predominantly banded and architectural designs, emulating painted or plaster cornices and borders. These represent the emerging design consciousness in Britain by the middle of the 19th century, and the migration of this to the colonies, away from naturalistic floral designs and towards geometric and formal patterns.Footnote92

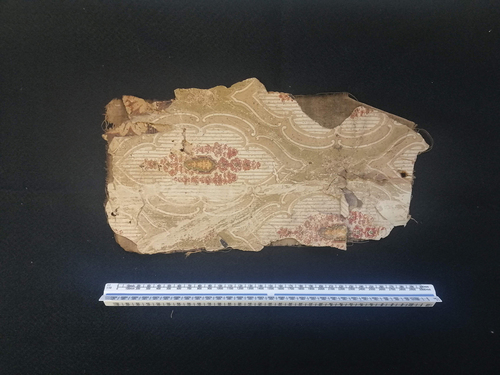

Material evidence of a c1860s wallpaper in situ, is provided by a rare surviving fragment of wallpaper revealed during archaeological investigations undertaken in 2020. This investigation was of a house on Maitland Street, Dunedin, originally occupied by Andrew Lindsay, a bootmaker, and his family.Footnote93 The fragment of wallpaper (), adhered to canvas onto the timber sarking boards, is the second wallpaper applied to the kitchen/living room of the original one-roomed cottage (built in 1859/60), or the parlour or bedroom of the extended cottage (from 1861/75). The first wallpaper, of which only a small section is visible in the top left-hand corner of the image, appears to have been a floral wallpaper. The second wallpaper is a common pulp paper, featuring a repeat diamond shaped green lattice pattern with a thin white border surrounding a central lozenge motif with a floral garland design in white, pink, green and yellow. This wallpaper fits chronologically with the styles that were popular in Britain around this time and those depicted in the shop windows and the Dunedin Exhibition displays, showing an uncanny resemblance to the wallpaper immediately on the left of the doorway to Andrew Lees’ shop (). Is it possible that Andrew Lindsay or his wife purchased this wallpaper from Andrew Lees? Unfortunately, proving this connection would involve evidence from Lees’ ledger or daybook, which has not survived the ravages of time and archival selection.

Conclusion

Decorative interior linings such as wallpaper were the backgrounds against which Dunedin’s domestic and public interiors were designed. After the construction of the frame and exterior of the house, they were the next step in the physical and psychological construction of home, prior to the addition of more transient forms of decoration such as loose carpets, curtains, furniture, and ornamentation. For homeowners, fixed linings such as wallpaper represent more permanent investments, and decisions on which ones to use were determined from their availability, cost, and personal choices based on design trends and individual tastes. This is as true today as it was in the past.

Internationally, the study of historic interiors has provided valuable information on past design trends, the factors that influenced these, the individuals and groups involved in their design, manufacture, trade and consumption, and the wider economic and socio-cultural contexts within which they operated. In New Zealand, research on early houses has largely focused on their exterior design and structure, with limited investigations of domestic interiors, including what materials were used when, how they were traded, and what they can tell us. This paper represents a step towards a better understanding of the material, economic and socio-cultural history of New Zealand’s early domestic interiors.

This study of wallpapers in 1860s Otago demonstrates the value of researching an important component of 19th century interior design “off the wall,” through its consumption and trade, rather than only “on the wall” within its context of use inside homes and buildings. The focus of wallpaper is shifted from the realm of personal taste and individual choices to its role as part of the international system of fashion, from its design and manufacture to its dissemination via trade networks to consumers. This is achieved through tracing the quantities and types of wallpaper that entered Otago using trade statistics and newspapers, their language of sale in advertisements, and the visual displays of wallpapers in shop windows and in the Furniture Court of the 1865 New Zealand Exhibition. As a result, one of the few material fragments remaining from this period, the wallpaper remnant from the Maitland Street home of Andrew Lindsay and his family, can be traced through these trade networks and contextualised within the production, marketing, and consumption of wallpaper in the British world.

The picture that emerges of the wallpaper trade during the Otago goldrush is of a trade in predominantly British wallpapers, and a trans-Tasman network that facilitated the movement of wallpapers, consumers, and traders between the colony of Victoria and Otago. The supply and demand for wallpapers in Otago was tied to the changing fortunes of the goldfields, the associated building boom, and the family and business connections of wallpaper merchants. The insights into the patterns of wallpapers available in Dunedin in the 1860s, provide visual and datable evidence of wallpapers that adorned the walls of Otago’s goldrush interiors, reflecting the ways in which British fashions shaped ideas of home in the Empire’s most distant colony.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michele Summerton, cultural historian and heritage consultant, for her assistance with the Melbourne based business histories of some of Otago’s wallpaper merchants, and our engaging discussions on the little-known histories of wallpaper in Australia and New Zealand.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. “Paper-Hanging,” The Argus, April 14, 1853. The term “paperhangings” or “paper hangings” is the term most frequently used for wallpapers in 19th century New Zealand, and indeed elsewhere in the British Empire. The term “wallpaper” will be used throughout this article as this is the term in use today and most familiar to readers, unless the term “paperhangings” is used in a quote from an original source.

2. R J Inman, The Argus, July 13, 1855; “Important to Painters,” The Banner, June 4, 1854.

3. The Melbourne & Ballarat Cheap Paper-Hanging Warehouse, The Star, January 20, 1857; “Important Notice,” Mount Alexander Mail, May 18, 1859.

4. “Paperhangings-Paperhangings,” Otago Daily Times, April 18, 1862.

5. “The Million House,” Otago Daily Times, November 24, 1862.

6. Lloyd Carpenter and Fraser Lyndon, eds., Rushing for Gold: Life and Commerce on the Goldfields of New Zealand and Australia (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2016); Daniel Davy, Gold Rush Societies and Migrant Networks in the Tasman World, Studies in British and Irish Migration (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

7. Alison Drummond and Leo Roderick Drummond, At Home in New Zealand: An Illustrated History of Everyday Things before 1865 (Auckland: Latimer Trend and Co Ltd, 1967); Anna Petersen, New Zealanders at Home: A Cultural History of Domestic Interiors 1814–1914 (Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 2001); Christine McCarthy, “Domestic Wallpaper in New Zealand: A Literature Review,” Research and Publication by the Centre for Building Performance Research (Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington, July 16, 2009).

8. Christine McCarthy, “Before Official Statistics: The Early Commerce of Wallpaper in New Zealand,” Fabrications 20, no. 1 (2011): 96–119, https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2011.10539673.

9. Phillippa Mapes, “The English Wallpaper Trade, 1750–1830” (PhD, Leicester, United Kingdom, University of Leicester, 2016); Clare Taylor, “‘Figured Paper for Hanging Rooms’: The Manufacture, Design and Consumption of Wallpapers for English Domestic Interiors, c.1740-c.1800” (PhD, Open University, UK, 2010); Gainor Buckingham Davis, “Demand at First Sight: The Centennial of 1876 as a Catalyst for the Consumer Revolution in American Interior Design, 1876–1893” (PhD, Temple University, 1999); Wendy Andrews, “The Cowtan Order Books, 1824–1938: An Analysis of Wallpaper and Decorating Records and Their Use as Historical Sources” (PhD, Cambridge, University of Cambridge, 2017).

10. Breen, T. H. An Empire of Goods: The Anglicization of Colonial America, 1690–1776. Journal of British Studies, 25 no. 4 (1986): 467–499

11. Joanna Banham, “The English Response: Mechanization and Design Reform,” in The Papered Wall: The History, Patterns and Techniques of Wallpaper, 2nd edition (London, United Kingdom: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 132–49.

12. Brenda Greysmith, Wallpaper (London, United Kingdom: Studio Vista, 1976), 128.

13. William Laxton, The Builder’s Price Book for 1859, 38th edition (London: William Laxton, 1859), 181.

14. Greysmith, Wallpaper, 137–40.

15. Joanna Banham, A Decorative Art: 19th Century Wallpapers in the Whitworth Art Gallery (Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, 1985).

16. Banham, “The English Response”

17. Greysmith, Wallpaper, 109.

18. Banham, “The English Response” 132.

19. Alan Victor Sugden and John Ludlam Edmondson, A History of English Wallpaper, 1509–1914 (New York: C Scribner’s sons, 1926).

20. Mapes, “The English Wallpaper Trade, 1750–1830;” Taylor, “‘Figured Paper for Hanging Rooms.’”

21. John Bell Condliffe, “The External Trade of New Zealand,” in The New Zealand Official Yearbook (Wellington: Government Print, 1915).

22. Drummond and Drummond, At Home in New Zealand: An Illustrated History of Everyday Things before 1865.

23. McCarthy, “Domestic Wallpaper in New Zealand: A Literature Review”

24. A newspaper article from January 1862 mentions the absence of wallpaper manufacture in New Zealand at this time.” Old Practical, “What We Do and What We Do Not Do for Ourselves,” New Zealander, January 15, 1862.

25. Registrar General, Statistics of New Zealand for 1862 (Auckland: New Zealand Government, 1863), vii.

26. Term used by John Turnbull Thompson, Chief Surveyor of Otago in 1856 when describing Dunedin. As quoted in Hardwick Knight and Niel Wales, Buildings of Dunedin: An Illustrated Architectural Guide to New Zealand’s Victorian City (Dunedin: John McIndoe Ltd, 1988), 31.

27. Erik Olssen, A History of Otago (Dunedin: John McIndoe Limited, 1987), 64.

28. Chris McConville, Keir Reeves, and Andrew Reeves, “‘Tasman World:’ Investigating Gold-Rush-Era Historical Links and Subsequent Regional Development between Otago and Victoria,” in Rushing for Gold: Life and Commerce on the Goldfields of New Zealand and Australia (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2016), 27.

29. The Southern Provinces Almanac, Directory & Year-Book for 1862 (Lyttleton: Lyttleton Times, 1862), 150.

30. Based on the population statistics in the following: Registrar General, Statistics of New Zealand for 1859 (Auckland: New Zealand Government, 1860); Registrar General, Statistics of New Zealand for 1863 (Auckland: New Zealand Government, 1864).

31. Mackay’s Otago Provincial and Gold-Fields’ Almanack, Directory, and Annual Repository of Useful Information for 1866, 1st edition (Dunedin: Joseph Mackay, 1866), 139; Agents of the Provincial Government of Otago, Descriptive Sketch of the Province of Otago, New Zealand, as a Field of British Emigration. with Illustrations (Edinburgh: Bell & Bradfute, 1862), 50.

32. The Southern Provinces Almanac, Directory & Year-Book for 1863 (Lyttleton: Lyttleton Times, 1863), 150.

33. Jock Phillips and Terry Hearn, “The Provincial and Gold-Rush Years, 1853–70,” in Settlers: Immigrants to New Zealand from England, Scotland and Ireland, 1800–1945 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2008).

34. David Murray, “Lost Dunedin #3: Oriental Hotel,” Blog, Built in Dunedin (blog), February 24, 2013, https://builtindunedin.com/2013/02/24/lost-dunedin-3-oriental-hotel/; Stuart King and Julie Willis, “Mining Boom Styles,” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand, vol. 33 (Gold, Melbourne: Society of Architectural Historians, Australia New Zealand, 2016), 342.

35. Murray, “Lost Dunedin #3: Oriental Hotel”

36. Wallpaper imports are only intermittently recorded in the Blue Book (in the years 1841, 1843 and 1853 to 1856), the first statistical records compiled by the secretary of the Governor General. The Statistics of New Zealand were published from 1853 onwards and included trade and interchange statistics. However, “Paper hangings” (wallpaper) are only noted on the itemised list of imported goods from 1867.

37. From export statistics on wallpaper compiled from the following sources for the period 1860 to 1867: Ledgers of export of British merchandise under countries and Ledgers of foreign and colonial merchandise under countries (United Kingdom), Statistical Register of New South Wales (New South Wales), Statistics of the Colony of Victoria (Victoria).

38. The Statistics of New Zealand (1868 to 1872). The quantities of wallpapers imported into New Zealand from elsewhere in the world was very low, with less than 1%, coming from China at this time.

39. Lloyd Carpenter and Lyndon Fraser, eds., Rushing for Gold: Life and Commerce on the Goldfields of New Zealand and Australia (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2016); Davy, Gold Rush Societies and Migrant Networks in the Tasman World.

40. Lloyd Carpenter and Fraser Lyndon, “Introduction: An Australasian Goldfield,” in Rushing for Gold: Life and Commerce on the Goldfields of New Zealand and Australia (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2016), 7; The Southern Provinces Almanac, 1863, 132.

41. Lloyd Carpenter, “The Merchants of the Rush: The Proto-Bankers of the Goldfields,” in Rushing for Gold: Life and Commerce on the Goldfields of New Zealand and Australia (Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press, 2016), 222–39.

42. Michael Lech, Wallpaper (Sydney: Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2010), 14–16.

43. As per the Statistical Register of New South Wales and Statistics of the Colony of Victoria for the years 1860 to 1867.

44. James Watson, Links: A History of Transport and New Zealand Society (Wellington: GP Publications, 1996), 96.

45. Muriel Lloyd Prichard, An Economic History of New Zealand to 1939 (Auckland: Collins, 1970), 69.

46. Victorian newspapers were accessed via Trove, Australia’s online newspaper repository. Otago newspapers were accessed via PapersPast, New Zealand’s equivalent repository, between February and April 2023. Digitised Otago newspapers between 1860 and 1867 included: Otago Witness (Dunedin), Otago Daily Times (Dunedin), Evening Star (Dunedin), North Otago Times (Oamaru), Lake Wakatip Mail (Queenstown, May 1863 onwards), Dunstan Times (Clyde, 1866 onwards), Bruce Herald (Milton, 1864 onwards). The following search term string was used, employing the range of terms for wallpaper in use in the 19th century: “paperhanging*” OR “paper hanging*” OR “paper-hanging*” OR “wallpaper*” OR “wall paper*” OR “wall-paper*” OR “roompaper*” OR “room-paper*” OR “room paper*.”

47. The Southern Provinces Almanac, 1863, 131.

48. McCarthy, “Before Official Statistics,” 102.

49. “Page 2 Advertisements Column 1,” Otago Witness, February 8, 1852.

50. “Loss of the ‘Henbury’ by Fire,” Otago Witness, August 27, 1859.

51. David Milne, Otago Witness, February 4, 1860; James Keir & Co, Otago Witness, August 25, 1860.

52. Page 2 Advertisements Column 4, Otago Witness, February 7, 1857; Ian Church, Jones, John (1809–1869), in Southern People: A Dictionary of Otago Southland Biography (Dunedin: Longacre Press, 1998).

53. ”Page 2 Advertisements Column 4,”Otago Witness, February 25, 1854, 4.

54. “Page 2 Advertisements Column 1,” Otago Witness, July 28, 1855, 1.

55. Sixteen of these new wallpaper merchants were identified in Otago newspapers between May 1861 and May 1863, with the remaining three, W Dodds, Gilbert & Co and Holmes & Amos, noted in the “Painters, Glaziers and Paperhangers” trade section of the Southern Provinces Almanac of 1862 and 1863.

56. On Sale by the Undersigned, Otago Daily Times, December 23, 1861.

57. Business Notice, Otago Witness, June 25, 1859.

58. Gunpowder, Tea, The Argus, April 8, 1856; “Thursday 15th April,” The Age, April 9, 1858.

59. “Victorian Auction Mart,” Otago Daily Times, March 4, 1862.

60. Harnett & Co’s Dunedin Directory (Dunedin: Harnett & Co Stationers, 1865), 25.

61. First Great Sale by Auction, Lake Wakatip Mail, November 7, 1863.

62. To Contractors, Builders, and Others, Otago Daily Times, January 27, 1862.

63. The export statistics of wallpaper from the United Kingdom to New South Wales and Victoria peaks in the years 1853 and 1854, during and immediately following the Victorian goldrush. As per the Ledgers of Export of British Merchandise Under Countries, compiled by the Board of Customs and Excise in the United Kingdom.

64. Agents of the Provincial Government of Otago, Descriptive Sketch of the Province of Otago, New Zealand, as a Field of British Emigration. with Illustrations, 45.

65. The Melbourne firm of Brooks, Robinson & Co, which arose from the paint and wallpaper business established by Henry Brooks in 1854, remained in business well into the 20th century. See The Federal Council of the Chambers of Manufacturers of Australia, Australian Industry: For the Advancement of Australian Manufactures and Extension of Trade (Brisbane: Chambers of Manufactures of Australia, 1906), B119.

66. Plate and Sheet Glass, Paperhangings, Paints, Oils,” Otago Daily Times, May 11, 1863.

67. The Furniture History Society, Shoolbred, James & Co, December 8, 2022, https://bifmo.furniturehistorysociety.org/entry/shoolbred-james-co-1814–1934; “At Tottenham House,” Argus, November 29, 1858.

68. “Paperhangings,” Otago Daily Times, February 14, 1862.

69. “Wanted Known,” Otago Daily Times, December 19, 1862.

70. “Dunstan,” Otago Daily Times, June 13, 1864.

71. “Fish & Knight,” Otago Daily Times, February 26, 1862.

72. “Wanted Everybody to Know,” Otago Daily Times, June 10, 1862.

73. “Wanted to Sell,” Otago Daily Times, May 3, 1862.

74. “William Houston,” Bruce Herald, June 14, 1866; J S Anderson, North Otago Times, April 14, 1864.

75. “Paperhangings,” Dunstan Times, January 6, 1866.

76. Harnett & Co’s Dunedin Directory (Dunedin: Harnett & Co Stationers, 1864); Mackay’s Otago Provincial and Gold-Fields’ Almanack, Directory, and Annual Repository of Useful Information for 1864, 1st edition (Dunedin: Joseph Mackay, 1864); Harnett & Co’s Dunedin Directory (Dunedin, New Zealand: Harnett & Co Stationers, 1863); Harnett’s Dunedin Directory (Dunedin: E Esquilant & Co, 1867).

77. “Abstract of Sales by Auction,” Otago Daily Times, August 5, 1865.

78. Daniel Davy, “A Great Many People I Know from Victoria:’’ The Victorian Dimension of the Otago Gold Rushes,” in Rushing for Gold: Life and Commerce on the Goldfields of New Zealand and Australia (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2016), 46.

79. “Wanted to Sell,” Otago Daily Times, October 30, 1862.

80. Christopher Cochran and Russell Murray, “Randall Cottage, 14 St Mary Street, Thorndon: Conservation Plan,” Conservation Plan (Wellington, 2017), 17.

81. The suitability of these types of papers for dining and drawing rooms is mentioned in the advertisement by R E Inman. See footnote 5.

82. Lech, Wallpaper, 7.

83. Phyllis Murphy, “Decorating with Wallpaper,” Technical Bulletin, National Trust Victoria 6.1 (1987): 9.

84. “Paperhangings,” Otago Daily Times, February 19, 1862.

85. For example, S H Brooks’ Rudimentary Treatise on the erection of Dwellinghouses (1860), stipulated for different types and qualities of wallpaper to be used in public rooms such as the parlour, versus more private rooms, such as bedrooms. See S H Brooks, Rudimentary Treatise on the Erection of Dwellinghouses, Or The Builderʼs Comprehensive Director (London, United Kingdom: John Weale, 1860), 139.

86. Phyllis Murphy, Historic Wallpapers in Australia, 1850–1920 (Castlemaine: Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum, 1996); Phyllis Murphy, “Eleven Layers of Wallpaper from Clarendon Terrace: A Reflection of Social Change,” Historic Environment 3, no. 3 (1984): 22–30; Phyllis Murphy, “Victorian and Edwardian Wallpapers Exhibition, Hawthorn Gallery, Victoria,” Historic Environment 1, no. 2 (1981): 7–9.

87. Andrews, The Cowtan Order Books, 1824–1938: An Analysis of Wallpaper and Decorating Records and Their Use as Historical Sources, 53.

88. Unknown, Official Record of the Sydney International Exhibition, 1879 (Sydney: Thomas Richards, Government Printer, 1881); Unknown, Melbourne International Exhibition, 1880–1881. Official Record Containing Introduction, History of Exhibition, Description of Exhibition and Exhibits, Official Awards of Commissioners and Catalogue of Exhibits (Melbourne: Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, 1882); Executive commissioners, Official Record of the Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne, 1888–9, (Melbourne: Sands & McDougall Limited, 1890).

89. W H Harrison, “Class XXX-Furniture & Upholstery, Including Paperhangings and General Decorations,” in New Zealand Exhibition 1865; Reports and Awards of the Jurors (Dunedin: Mills, Dick & Co, 1866), 292–93.

90. Harrison, “Class XXX-Furniture & Upholstery, Including Paperhangings and General Decorations,” 293.

91. Unknown, “Canons of Taste in Carpets, Paper-Hangings and Glass,” The Journal of Design and Manufactures 4, no. 19 (September 1850): 14–15.

92. Greysmith, Wallpaper, 119–32.

93. Jeremy Moyle, “Archaeological Assessment for 87 Maitland Street, Dunedin: Archaeological Site I44/987,” Buildings Archaeology report (Dunedin: Origin Consultants Ltd, May 2020).